Degree Project in Criminology Malmö University Two-year Master (120 credits] Faculty of Health and Society

WOMEN’S AWARENESS OF

LEGISLATION ON VIOLENCE

AGAINST WOMEN ACROSS

THE EUROPEAN UNION

A SECONDARY DATA ANALYSIS OF THE

2012-FRA-VAW SURVEY

SOFIA WITTMANN

WOMEN’S AWARENESS OF

LEGISLATION ON VIOLENCE

AGAINST WOMEN ACROSS

THE EUROPEAN UNION

A SECONDARY DATA ANALYSIS OF THE

2012-FRA-VAW SURVEY

SOFIA WITTMANN

Wittmann, S. Women’s awareness of legislation on violence against women across the European Union. A secondary data analysis of the 2012-FRA-VAW-Survey. Degree project in Criminology 30 Credits. Malmö University: Faculty of Health and Society, Department of Criminology, 2019.

Violence against women (VAW) is the most prevalent human rights violation of our time, rooted in women’s unequal status in society. Aim: The present study investigated women´s awareness of preventative and protective legislation on domestic violence and women´s awareness of campaigns against VAW across the EU. Further, it explored how EU state members´ political efforts to combat VAW might affect women´s awareness. It also examined the correlation between gender equality within EU state members and women´s awareness. In addition, the relationship between socio-demographic factors and women´s awareness was examined, including possible affects correlated with states members’ political efforts. Method: A secondary data analysis was conducted with data drawn from the 2012 FRA-VAW Survey, carried out in all 28 EU member states. Results: Results indicated that women across the EU were more aware of protective legislation than preventative regarding domestic violence, and that almost 1 in 2 women were unaware of recent campaigns against VAW in their country of residence. Results indicated that defined legislation and higher levels of gender equality within EU member states were associated with higher levels of awareness among women. Results further suggested that women with socio-demographic characteristics previously associated with inter-partner violence had particularly low awareness. Conclusion: As political and legal norms are required for VAW to be perceived as a crime, an increased emphasis on clear definitions of VAW is essential. Legal definitions of VAW and awareness of legislation are undervalued key factors in societies’ attempts to fulfil the goal of total eradication of VAW. Keywords: Legislation, Quantitative Analysis, Violence Against Women, Women’s Awareness, 2012-FRA-VAW-Survey.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my research supervisor, Anna-Karin Ivert, for immense support, advice and encouragement. Her willingness to give her time so generously has been very appreciated.

Thank you to my study buddies Hulda, Lena and Leila for all your support and your friendship in the making of this study. I wouldn’t have managed without you.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

DV: Domestic Violence

EIGE: European Institute for Gender Equality EU: European Union

EWL: The European Women’s Lobby

FRA: European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights GEI: Gender Equality Index

IPV: Intimate Partner Violence NAP: National Action Plan SES: Socio-Economic Status VAW: Violence Against Women

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction ... 6

Previous research ... 7

Legislation and political efforts to combat VAW in the EU ... 7

Socio-demographic factors and awareness of legislation ... 9

Aim ... 10

Research questions ... 10

Method ... 11

Data & Study Population ... 11

Ethical considerations ... 12 Assessment of variables ... 12 Outcome variables ... 12 Country-level variables ... 12 Individual-level variables ... 13 Analytical strategy ... 15 Results ... 15 Discussion ... 24 Results discussion ... 24

Methodological Considerations & Limitations ... 27

Conclusions ... 28

INTRODUCTION

Violence against women (VAW) is the single most prevalent and universal human rights violation of our time. It is a global pandemic rooted in women’s unequal status in society, institutionalised through laws, policies, and social norms that grant privileged rights to men (Council of Europe, 2011; European Commission, 2010; Garcia-Moreno et al., 2014; Radford, 1992). As VAW has its historical, cultural and social roots in societal systems placing women in a subordinated position in relation to men, perpetration has been accepted, condoned and ignored throughout history. VAW remains a pervasive form of discrimination, widely recognised to result from a complex interaction between individual, relationship, community, and societal factors (Council of Europe, 2011; Garcia-Moreno et al., 2014).

The definition of violence against women (VAW) provided by the

UN Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women (1993) is: Any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to

result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public and private life. Gender-based violence is any violence inflicted on women because of their sex.

VAW is a wide-ranging term, encompassing both intimate partner violence (IPV) and domestic violence (DV).

VAW also remains a complex challenge in criminology, a historically male dominated field of research (Chesney-Lind & Chagnon, 2016). As women’s perspectives and victimization experiences traditionally have been disregarded, one could argue that the masculinist bias present in criminology is part of the very social paradigm that enables VAW. Academia is no exception from reigning gender privileges (Bell, 2002; Chesney-Lind & Chagnon, 2016). State agencies controlled by men have also systematically made concessions in response to VAW, normalizing it. If a certain behaviour is to be perceived as a crime, the presence of reflecting social and political norms are required (Eliasson, 1997). As male perpetrators continue to receive fellow patriarchal support, validation in gender stereotypes and expectations of masculinity, they are enabled to justify their crimes (Radford, 1992). Ultimately, VAW constitutes a grim obstacle for human development, as it poses a barrier to equal participation in society (Garcia- Moreno et al., 2014).

VAW is a complex phenomenon which requires a nuanced understanding of sociodemographic factors and their bearing in defining risk. There is a pressing need for research focus on how political, economic and social contexts might influence women´s exposure to violence (Kiss et al., 2012). In addition, research on legislation supposed to protect women and societies from this type of human rights violation is scarce (Ortiz-Barreda & Vives-Case, 2013). Female victim blaming explanations that have been a credible part of mainstream discourse over time, is mirrored in VAW legislation (Radford, 1992). Further, progressive legislation remains insufficient when implementation is lacking (Garcia-Moreno et al., 2014). While protective structures are essential, it is equally important to

ensure that women are informed of their rights and have knowledge on where and how to seek help (Council of Europe, 2011).

If the goal of total eradication of VAW is ever to be fulfilled, emphasis on legal definitions of VAW and women’s awareness of their legal rights is required. To the author’s knowledge, the present study is the first to investigate women´s awareness of legal rights regarding VAW across the EU. Since legislation on VAW remains a fundamental part of women´s rights, and women´s awareness of such legislation is crucial, this study is of great importance.

Previous research

Legislation and political efforts to combat VAW in the EU

Equal opportunity for men and women has been a priority within Europe since the 1970s, although gender directives primarily targeted employment policies

throughout the 1970s-1980s (Corradi & Stöckl, 2016; Lombardo & Meier, 2008; Montoya, 2009). The European Parliament’s Committee on Women’s Rights issued a report and proposed a resolution on VAW for the first time in 1986 (EU, 2019). Even though both the report and the resolution were adopted, EU level initiatives aimed at combating VAW have primarily been carried out after the mid-1990s (Montoya, 2009). The “Campaign for Zero Tolerance for Violence against Women” launched by the European Parliament in 1998, has been widely recognized as the momentum in EU level efforts to combat VAW. Funded by the European Commission, the campaign raised public awareness about domestic violence (DV), strived for better strategies for prevention and highlighted the goal of elimination of all forms of VAW (Montoya, 2009).

The Daphne program is another instrument of great importance within the EU. Implemented in 1997, its purpose is to support victims, prevent and combat all forms of violence against children, young individuals and women across all member states (European Commission, 2010). The first activities of the Daphne initiative took place in the period 1997 until 1999, followed by Daphne I in 2000– 2003, Daphne II in 2004–2008 and Daphne III in 2007–2013 (European

Commission, 2010; Montoya, 2008).

The first legal document to frame a wide-ranging approach to counteract VAW, was ‘Recommendation Rec (2002)5 on the protection of women against violence’. Recommendation Rec (2002)5 comprehended all forms of gender-based violence, outlined general principles and procedures for services, legislation, policing, intervention for perpetrators, awareness-raising, education and data collection (European Commission, 2007). Comprehensive legislation regarding victims of crime was enacted in May 2011, as the European Commission adopted a set of legislative proposals to improve the rights of victims of crime (EU, 2012; FRA, 2014). This included the EU Victims’ Directive27 establishing minimum standards on the rights, protection and support of victims of crime (EU, 2012). In 2011, the Council of Europe Committee of Ministers signed the ‘‘Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence’’, also referred to as the Istanbul Convention (Council of Europe, 2011). It is the most recent and the most comprehensive regional instrument to address violence against women, urging member states to provide a holistic response to VAW. The Istanbul Convention advocates for EU member states to incorporate new offenses into their penal codes and to implement wide-ranging and coordinated policies on

VAW (Council of Europe, 2011). It outlines preventative as well as protective guidelines, encouraging member states to run awareness-raising campaigns on a regular basis and to emphasize gender equality in teaching materials. The Istanbul Convention further urges state members to provide adequate information to victims of VAW, ensuring that they have access to easy and concise information on available services in a language they can understand. It is further emphasized that while protection structures and support services for victims are essential, it is equally important to ensure that women are informed of their rights (Council of Europe, 2011).

The EU remains a central agent in combatting VAW across Europe through council conclusions and resolutions by the European Parliament, funding and awareness-raising activities. EU’s encouragement of exchanges of good practices between state members is further of high importance. Nevertheless, the primary obligation to combat VAW is placed on the EU member states (European Commission, 2010). Despite widespread policy adoption within state members, actual reforms have been inadequate (Lombardo & Meier, 2008; Montoya, 2009). The EU has refrained from exercising its binding authority on issues related to VAW, implementing several nonbinding initiatives as an alternative. Emphasis has been placed on soft law reports and recommendations, conferences and public awareness campaigns. Although nonbinding initiatives are essential for norm distribution, the EU consequently fails to hold member states accountable for inadequate domestic practices (Lombardo & Meier, 2008; Montoya, 2008 & 2009).

Montoya (2009) identifies the accession process for new state members as an exception to EU practices described above, since the conditionality of

membership enables EU to take a more authoritative stand over a wider range of issues. States applying for membership are obliged to adopt binding legislation and the larger body of legislation, which includes soft law measures (Montoya, 2009).

Gender inequality within states has further been identified to correlate with victimization of intimate partner violence (IPV), even though such correlations are undecided (Archer, 2006; Gracia and Merlo, 2016; Jewkes, 2002; Kiss et al., 2012). Previous research suggests that societies with stronger ideologies of male dominance experience more VAW in the form of IPV (Jewkes, 2002; Kiss et al., 2012). Support has also been found for that victimization is likely to decrease as gender equality increases (Archer, 2006). Findings suggest that women reaching a higher status in relation to their partners against a background of traditional gender norms, can be at higher risk of IPV victimization (Gracia and Merlo, 2016; Jewkes, 2002; Vyas and Watts, 2008). High prevalence of IPV in countries with high gender equality have been suggested to reflect higher levels of disclosure due to an allowing cultural context (FRA, 2014).

The need for further knowledge on macrostructural characteristics that can explain disparities and inter-country variability regarding VAW are however persistent. The European Women’s Lobby (EWL) Observatory on VAW has highlighted VAW legislation as an indicator of a state’s level of commitment and inclination to act according to advising legislation for the protection of women (EWL, 2001). Further, progressive legislation itself remains insufficient when implementation is dissatisfactory (Garcia-Moreno et al., 2014). With no explicit and coercive stance

on VAW within the EU, policy development in state members remains uneven and inadequate (Montoya, 2009).

In addition, complex conditions regarding legislation and policy development on VAW impacts data collection. While numerous sources of information on VAW across EU state members are accessible, they tend to be inadequate for the purposes of comparative and trend analysis according to the European

Commission (2010). Measurements over time and opportunities to determine the dimension of VAW are prevented due to that existing data are not comparable or collected on a regular basis (European Commission, 2010).

Socio-demographic factors and awareness of legislation

While research on prevalence of IPV and identification of vulnerable groups is substantial, research on legislation enacted to protect women from VAW is rare (Ortiz-Barreda & Vives-Case, 2013). To the author’s knowledge, no previous studies on awareness of legislation on VAW across the EU have been conducted. A few studies have however investigated awareness of other types of legal rights. In 2002, the department of trade and industry in the UK carried out a report on Awareness, knowledge and exercise of individual employment rights (Meager, Tyers, Perryman, Rick and Willison, 2002). In their study of public perception of notification laws, Anderson and Sample (2008) investigated how and if people accessed registry information on sex offenders. Results found in these studies could possibly be reflected in awareness of other types of legislation.

Findings from previous studies indicate that VAW is inextricably associated with age, as younger women tend to be at higher risk of victimization of IPV than their older counterparts (Caetano et al., 2008; DeMaris et al., 2003; Lauritsen &

Schaum, 2004; Wright, 2011). Meager et al. (2002) found that awareness peaked among individuals aged 36-45, while the youngest and oldest age groups were the least aware of legislation.

Women of low socioeconomic status (SES) further seem to be subjugated to violence at relatively high rates compared to other groups (Beyer, Baber Wallis & Hamberger, 2015; Benson, Fox, DeMaris & Wyk, 2003; Benson, Woodredge, Thistlethwaite, & Fox, 2004; Carbone-Lopez, Rennison & Macmillan, 2012; Cunradi, Caetano, Clark, & Schafer, 2000; Wyk, Benson, Fox & DeMaris, 2003, Jewkes, 2002; Jewkes, Levin & Penn-Kekana, 2002; Kiss et al., 2012; Wright, 2010). Educational attainment remains a main indicator of socioeconomic status, as it instigates wealth, self-confidence and social empowerment (Beyer et al., 2015). Further, education translates into an ability to use information and resources available in society, possibly influencing levels of awareness of legislation (Beyer et al., 2015; Carbone-Lopez et al., 2012; Jewkes et al., 2002). Given that SES, level of education and occupational status are inherently connected, level of income and occupation may also be associated with one’s ability to use information and resources, influencing the level of awareness of VAW legislation (Benson et al., 2003; Carbone-Lopez et al., 2012; Cunradi et al., 2000; Fernbrant, 2013; Jewkes, 2002). Anderson and Sample (2008) found a positive correlation between a higher level of education and income, and higher levels of awareness of legislation. Correspondingly, Meager et al. (2002) found that individuals in ‘higher’ level occupations and with higher educational qualifications were more likely to be aware of their rights.

Rates of violence and awareness of rights further seem to vary across racial and ethnic groups, as women in minority groups appear to be more vulnerable to IPV than others (Caetano et al., 2008; Cunradi et al., 2000; Fernbrant, 2013; Raj & Silverman, 2002). Anderson and Sample (2008) found that Caucasian women were more aware of legislation than women with other ethnicities. As it is a study conducted in the US, Caucasian women are in majority (United States Census Bureau, 2019). One must therefore consider the privileges that are linked with a Caucasian identity in the US. Results in Meager et al. (2002) also indicated that white individuals had higher levels of awareness and more substantial knowledge of rights than non-whites.

Religious minorities are associated with vulnerability as religious women often are unable or reluctant to seek external sources of assistance, and especially difficult to inform about legislation (Nason-Clark, Fisher-Townsend, Holtmann & McMulin, 2017). At the same time, religious institutions are important as they can engender knowledge on measures of prevention and protection (Cunradi et al., 2002; Nason-Clark et al., 2017).

Likewise, type of residential area appears to be associated with VAW. Previous studies have found that IPV is more common in disadvantaged and disorganized urban areas than in other types of communities (Benson et al., 2003; Benson et al., 2004; Lauritsen & Schaum, 2004). Anderson and Sample (2008) found that women residing in cities are more likely to have higher awareness of legislation in comparison to women residing in rural areas.

Aim

The overall aim of the present study was to investigate women´s awareness of legal rights regarding VAW across the EU and how awareness was associated with EU member states´ political efforts to combat VAW, in terms of policy and legislation. Further, it investigated how state level of gender equality and

sociodemographic factors were associated with women’s awareness.

Women´s awareness encompassed awareness of preventative- and protective legislation on domestic violence and campaigns against VAW provided by state members.

Research questions

i. Are women more aware of protective and preventative legislation and campaigns against VAW in states where progressive legislation and more comprehensive National Action Plans (NAPs) on VAW exist?

ii. Are women more aware of protective and preventative legislation and campaigns against VAW in states estimated to have a higher level of equality by the Gender Equality Index (GEI)?

iii. Are there any differences concerning legislation- and campaign awareness and state efforts to combat VAW associated with the duration of time states have been members in the EU?

iv. How is legislation- and campaign awareness correlated to individual social stratification within the EU?

The purpose of this study was to emphasize the importance of legal definitions of VAW and women’s awareness of their legal rights. While research on prevalence

and identification of vulnerable groups is imperative, legal definitions of VAW and awareness of legislation are undervalued key factors in societal attempts to fulfil the goal of total eradication of VAW.

METHOD

Data & Study Population

Data in the present study was drawn from the 2012-FRA-VAW Survey,

encompassing all 28 EU member states. The survey is the first EU-wide survey to gather comparable data on women’s experiences of gender-based violence in all 28 EU member states (FRA, 2015). The European Union Agency for

Fundamental Rights (FRA) carried out the survey in response to a request from the European Parliament for data on VAW, which the Council of the EU then came back to in its Conclusions on the eradication of VAW in the EU (FRA, 2014). The 2012-FRA-VAW Survey is the most comprehensive survey to date on women’s diverse experiences of violence. The survey carries important progress, as the absence of comprehensive and comparable data on VAW within the EU has limited the analysis of the bearing of policies and other macrostructural

determinants in the past (European Commission, 2010; Garcia-Moreno et al., 2014).

The 2012- FRA-VAW Survey targeted the general population, and the sample was stratified by geographical region and urban or rural character to make it more representative. The total sample included 42,002 women, aged 18 to 74, with a random probability sample of approximately 1,500 women per country. Data was primarily collected through structured face-to-face interviews in the home of the study participants. All interviews were conducted by female investigators, specially trained for the purpose of the survey. In addition, respondents were given a short self-completion questionnaire after the interview, offering women a more anonymous way to disclose their experiences of violence (FRA, 2014; FRA, 2015).

The survey drew from various international definitions of ‘violence against women’ and existing research on the phenomenon to grasp the wide range of women’s experiences (FRA, 2014). In order to avoid restricting women’s

understanding of violence, FRA decided not to provide a definition of VAW when presenting the survey to potential participants or when conducting survey

interviews (FRA, 2014).

According to FRA, the term ‘domestic violence’ is used variously across members states, referring exclusively to intimate partner violence or intergenerational violence (FRA, 2015). Due to the lack of a general and clear definition of

‘domestic violence’ within the EU, the term was not applied by FRA when results of the survey were presented. Instead, FRA chose to reference to ‘intimate partner violence’ (FRA, 2014).

According to the technical report provided by FRA (2014), their methodological strategies enabled estimates representative for all women aged 18 to 74, both at EU level and in each member state. One of the main criteria for participation, particularly relevant for this study, was that women who participated were

required to speak at least one of the official languages of the country they resided in (FRA, 2014). According to FRA (2014), less than 1 % of contacted women were unable to take part due to this language criteria.

Further details on methodology, sample and fieldwork of the 2012-FRA-VAW Survey can be found been elsewhere (FRA, 2014).

Ethical considerations

Approval to conduct this secondary data analysis has been received, and a special license has been provided by FRA (reference number:120715).

Regarding ethical implications of the present study, it is important to consider that the data presented in this study is on an aggregated level. Study participants therefore remain completely anonymous and protected (FRA, 2014). FRA removed all personal details concerning participating women before the data was uploaded to a central location. Further, no code key has been preserved (FRA, 2014). The author did subsequently not have access to any information that could tie sensitive matters regarding women’s victimisation experiences to specific individuals. However, potential ethical implications still need to be considered throughout the research process.

Since society often has failed to protect victimized women and women in minority groups, one must reflect upon long-term effects for participants and possible implications for vulnerable groups in society. There is always a need to be cautious of reproducing stereotypes when studying sensitive matters such as victimization and social stratification. It is therefore important to discuss results in a constructive and responsible manner.

Assessment of variables Outcome variables

In the present study the outcome variables were awareness of preventative- and protective legislation, across all 28 EU member states. Measures were self-reported, as they were based on the participant’s answers to the question “As far as you are aware, are there any specific laws or political initiatives in

(COUNTRY) for: a) Preventing domestic violence against women? b) Protecting women in cases of domestic violence?”. Variables were dichotomous and had the values ‘NO’ (=0) and ‘YES’ (=1). Respondents were not provided with any additional information or definitions on the terminology of Preventing or Protecting (FRA, 2019). To be certain of this, the author specifically emailed FRA and made enquires on definitions (FRA, 2019).

In addition to the above, a third outcome variable, Campaign Awareness, was correspondingly based on the participant’s answer to “Have you recently seen or heard any advertising addressing campaigns against violence against women?”. Campaign Awareness was predicted to further clarify the effort made by EU member states to prevent and respond to VAW. Campaign Awareness was dichotomous and had the values ‘NO’ (=0) and ‘YES’ (=1).

Country-level variables

Considered country level variables were National Legislation on VAW, National Action Plans on VAW, the Gender Equality Index (GEI) and length of membership

in the EU. Given that the FRA-VAW-Survey microdata were collected in 2012, all legislative documents, National Action Plans and data from the GEI were considered up to the year of 2012.

All 28 EU member states were categorized dependent on whether they had Defined Legislation, Non-Defined but Existing Legislation, or Non-Existing Legislation. For the purpose of this study, defined legislation meant legislation addressing VAW as a specific crime. Therefore, states with legislation constructed around terminology such as Domestic Violence, Family Violence, Family laws etc, were placed in the category of Non-defined but Existing Legislation (European Commission, 2010). Legislation was coded in a positive direction, with the values ‘Non-Existing Legislation’ (=0), ‘Non-Defined but Existing Legislation’ (=1) and ‘Defined Legislation’ (=2).

National Action Plans (NAPs) were considered between 2000-2012. The 28 state members were categorized depending on whether they had a National Action Plan on all forms of VAW, a National Action Plan on IPV or DV, or no National Action Plan related to VAW (European Commission, 2010). A new variable was created and coded in a positive direction, with the values ‘no National Action Plan related to VAW’ (=0), ‘National Action Plan on IPV or DV’ (=1) and ‘National Action Plan on all forms of VAW’ (=2).

The Gender Equality Index, (GEI), is a multidimensional indicator developed and defined by the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE). The GEI was used to assess the level of gender equality within EU member states. The index consists of 26 variables, which are grouped into the six domains of occupation, financial wealth, knowledge, time, power and health. The index ranges from 1 to 100, where a higher value implies greater equality (EIGE, 2017). For the purpose of this study, state members were categorized into three separate groups depending on their score in the GEI in 2012; low (≤59), medium (60-69) and high (≥70). The variable had the values ‘Low equality’ (=1), ‘Medium equality’ (=2) and ‘High equality’ (=3).

In order to estimate if there were any differences regarding awareness of legislation, existing legislation, implemented national action plans or levels of equality between state members that had been a part of the EU for a longer duration of time and more recent members, the variable Membership Status was created. State members were categorized into two groups, dependent on whether they were a part of the EU15 or joined post 2004 (EU, 2019). The members of EU15 are presented in table 2. Membership Status had the values of ‘EU15’ (=1) and ‘New state members’ (=2).

Individual-level variables

Based on previous research regarding experiences of IPV and awareness of legislation, the following individual level variables were chosen for the analysis; Age, Level of Education, Level of Income, Occupation, Minority Status (in terms of ethnicity, immigration and religion), Foreign Background and Type of

Residential Area. Although all original variables were recoded to exclude missing values, categories created by FRA were kept in two variables. The remaining variables were recoded into new categories to fit the purpose of this analysis.

Age was divided into five categories, where each category roughly represented a 10-year age span, with a range from 18-29 to 60+. Figures were coded negative to positive, ranging from young to old age and had the values ‘18-29’ (=1), ‘30-39’ (=2), ‘40-49’ (=3), ‘50-59’ (=4), ‘60+’ (=5).

Level of Education was divided into three categories; (i) primary school, (ii) secondary school and (iii) university. Level of Education was recoded to exclude missing values, while the three original categories created by FRA were kept. Figures were coded in a positive direction and had the values ‘Primary School’ (=1), ‘Secondary School’ (=2) and ‘University’ (=3).

Level of Income was measured in terms of the household’s combined

monthly/annual income, divided into four categories. Women were asked to estimate their household’s combined monthly/annual income by placing

themselves on a scale ranging from below the lowest quartile to above the highest quartile in their country. Although Level of Income was recoded to exclude missing values, the quartiles created by FRA was kept and coded in a positive direction. The variable had the values ‘below the lowest quartile’ (=1), ‘between lowest quartile and median quartile’ (=2), ‘between median quartile and highest quartile’ (=3) and ‘above the highest quartile’ (=4).

Occupation was divided into three categories depending on if women received a salary for their work, were unemployed or worked without any payment, or were students, retired or in the military service. The original variable for Occupation was recoded and simplified from 11 to three categories. Occupation had the values ‘received salary for work’ (=1), ‘unemployed or somehow worked without any payment, domestic housework included’ (=2) and ‘students, retired or in the military services’ (=3).

Minority Status was also measured by the 2012-FRA-VAW-Survey, as women were asked if they considered themselves to be a part of either an ethnic,

immigrant, religious or sexual minority, or a minority in terms of disability. Given that percentages for positive responses were very low, original variables for ethnic, immigrant and religious minority identities were computed into one. Other minority identities had to be discarded due to low percentages in the survey. Minority Status was recoded into a dichotomous variable; (i) women who considered themselves to be a part of a minority group and (ii) women who did not consider themselves to be a part of a minority group, with the values ‘YES’ (=1) and ‘NO’ (=0).

Parental country of birth was used as a proxy for foreign background and was categorized into three groups; (i) both parents born in the country of residence, (ii) one parent born in the country of residence, and (iii) both parents born in another country. Foreign background had the values ‘No Parent Born Outside the

Country’ (=0), ‘One Parent Born Outside the Country’ (=1) and ‘Both Parents Born Outside the Country’ (=2).

Type of residential area was divided into three categories; (i) women who lived in a big city, (ii) women who lived in the suburbs or a smaller city, (iii) women who lived in a country village or a countryside home. Answers were coded in a

positive direction and the variable had the values ‘Big City’ (=1), ‘Suburbs or in a Smaller City’ (=2) and ‘Country Village or in a Countryside Home’ (=3).

Data was coded and analysed using SPSS Version 25. Analytical strategy

Initially, a descriptive analysis of the outcome variables, country-level variables and individual-level variables was conducted. Then, a more detailed descriptive analysis of country-specific information for Legislation- and Campaign

Awareness, National Legislation on VAW, National Action Plans on VAW, the Gender Equality Index (GEI) and Membership status was conducted.

Secondly, Chi-Square Tests of Independence were performed. Tests were conducted in order to examine the differences between (i) Awareness of Preventative Legislation, (ii) Awareness of Protective Legislation and (iii) Campaign Awareness Legislation among women, linked to legislation, NAPs on VAW, level of gender equality and EU membership status in their country of residence.

Finally, three separate logistic regressions were conducted to investigate how individual-level variables and country-level variables were associated with (i) Awareness of Preventative Legislation, (ii) Awareness of Protective Legislation and (iii) Campaign Awareness. Analyses were conducted block wise, as

individual predictors were added in the first block, and country-level variables were added in the second block.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows descriptive figures for socio-demographic factors of the sample. The results presented in table 1 indicate that the distribution of age groups was relatively even within the study sample. However, results show a slightly higher percentage of women who were 60-74 years old, in comparison to remaining age groups. Regarding level of education, women who had finished secondary school were in majority, as they constituted 50% of the sample. The distribution of groups concerning income was also relatively even, however, 17,8% of the women decided not to answer this question. Women who received salary for their work were also in majority with 49,9%, with similar results at 46,9% for women residing in the suburbs or in a smaller city.

When asked if they considered themselves to be part of an ethnic, immigrant or religious minority, 93% of the sample answered no. Figures in table 1 also display that 86,7% of the sample had parents born within the same country as they resided in. These results imply that the 2012 FRA-Survey did not reflect accurate

diversity within the EU in 2012, as minority women and women with a foreign background seem to have been underrepresented. Furthermore, the sample mainly consists of working women that finished a secondary level of education, living in the suburbs or in a smaller city.

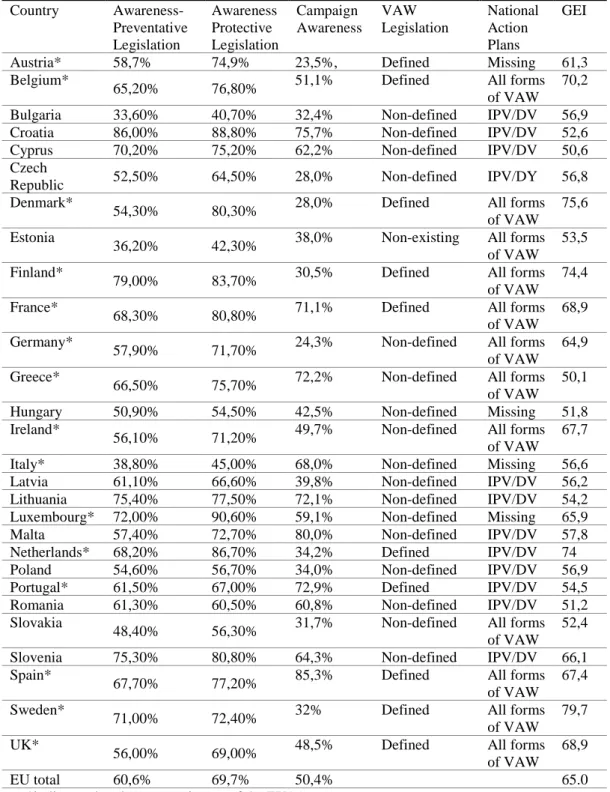

Figures in table 2 describe the valid percentage of both legislation- and campaign awareness across the EU. Results indicate that overall, women in the EU were more aware of protective legislation on domestic violence (DV) than preventative, and that almost 1 in 2 women were unaware of recent campaigns against VAW. Table 1: Descriptive statistics for individual-level variables (N=42002).

Individual Predictors Category N Valid %

Age 18–29 6827 16,3% 30–39 7483 17,9% 40–49 8269 19,7% 50–59 8299 19,8% 60+ 11 017 26,3% Missing 107 0,3% Total 42 002 100%

Level of Education Primary 11 818 28,3%

Secondary 20 924 50,0%

University 9089 21,7%

Missing 171 0,4%

Total 42 002 100,0%

Income Below lowest quartile 9453 27,4%

Between lowest and median quartile 9597 27,8%

Between median and highest quartile 8371 24,3%

Above highest quartile 7093 20,6%

Missing 7488 17,8%

Total 42 002 100,0%

Occupation Paid work 20 513 49,4%

Unpaid/unemployed 9729 23,5%

Student, retired or military 11 241 27,1%

Missing 519 1,2%

Total 42 002 100,0%

Minority Status Not a minority 39 060 93,0%

Minority 2942 7,0%

Total 42 002 100%

Foreign Background Parents born in country of residence 35 980 86,7%

One parent born in another country 1911 4,6%

Both parents born in another country 3625 8,7%

Missing 486 1,2%

Total 42 002 100,0%

Type of residential area Big city 10 296 25,4

Suburbs or smaller city 19 005 46,9%

Country village or countryside home 11 180 27,6%

Missing 1521 3,6%

The highest level of awareness of specific laws or initiatives aimed to prevent DV was found in Croatia, where 86% of the sample answered ‘YES’. Cyprus, Finland, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Slovenia and Sweden also had positive figures above 70%. The state of Bulgaria had the lowest proportion of awareness of preventative legislation, with 33,6% of the women stating they were aware of specific laws or initiatives aimed to prevent DV.

The highest level of awareness of specific laws or initiatives aimed to protect women in cases of DV was found in Luxembourg, where 90,6% of women answered ‘YES’. Other countries displaying awareness above 80% were Croatia, Denmark, Finland, France, Netherlands and Slovenia. Overall, the proportion of awareness of protective legislation was larger than awareness of preventative legislation.

Spain had the highest positive percentage regarding campaign awareness with 85,3%, followed by Malta, Croatia, Portugal and Greece. The five countries that displayed the lowest rates of campaign awareness were Austria, Germany, Czech Republic, Denmark and Finland.

During the categorisation process Estonia stood out as the only member state without national legislation addressing any form of VAW as a crime. Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden and the UK all had legislation with VAW addressed as a specific crime. The other 17 states had existing legislation based on the terminology of Domestic Violence, Family Violence, Family laws etc (European Commission, 2010; EIGE, 2016). 12 countries had a NAP on all forms of VAW in place between 2000-2012. Correspondingly, 12 states had a NAP on IPV/DV in place. The four states without a NAP on any issues related to VAW were Austria, Italy, Luxembourg and Hungary.

Sweden received the highest score in the Gender Equality Index (2017) at 79,7, and Greece received the lowest score at 50,1. Belgium, Denmark, Finland and the Netherlands scored above 70, also placing them in the category of states with high levels of equality in 2012. Most state members were placed in the category of states with low levels of equality.

There was no clear pattern for legislation- and campaign awareness in relation to whether states were EU15 members or new state members. However, all the new state members received a low equality ranking, except from Slovenia. Further, they all had non-defined but existing legislation, except Estonia which had none. Estonia and Slovakia did have a NAP on all forms of VAW, whereas Hungary had no NAP on issues related to VAW. The remaining new state members all had a NAP on IPV/DV.

Results in table 3 show that 3,6% of the women lived in a state (Estonia) without any VAW legislation (European Commission, 2010). Due to it being the only country without legislation, Estonia is discarded in further discussions, as its presence would skew the overall results in the analysis. 60,4% of women resided in states with national legislation based on the terminology of Domestic Violence, Family Violence, Family laws etc (European Commission, 2010; EIGE, 2016). Correspondingly, 36% of women resided in states with defined VAW legislation (European Commission, 2010).

Results in table 3 further display that 13% of the women resided in states without a NAP on issues related to VAW, while 43,6% of the women resided in states

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of outcome variables and country-level variables for each EU state member. Country Awareness- Preventative Legislation Awareness Protective Legislation Campaign Awareness VAW Legislation National Action Plans GEI

Austria* 58,7% 74,9% 23,5%, Defined Missing 61,3

Belgium*

65,20% 76,80% 51,1% Defined All forms

of VAW

70,2

Bulgaria 33,60% 40,70% 32,4% Non-defined IPV/DV 56,9

Croatia 86,00% 88,80% 75,7% Non-defined IPV/DV 52,6

Cyprus 70,20% 75,20% 62,2% Non-defined IPV/DV 50,6

Czech

Republic 52,50% 64,50% 28,0% Non-defined IPV/DY 56,8

Denmark*

54,30% 80,30% 28,0% Defined All forms

of VAW

75,6 Estonia

36,20% 42,30% 38,0% Non-existing All forms

of VAW 53,5

Finland*

79,00% 83,70% 30,5% Defined All forms

of VAW

74,4 France*

68,30% 80,80% 71,1% Defined All forms

of VAW 68,9

Germany*

57,90% 71,70% 24,3% Non-defined All forms

of VAW 64,9

Greece*

66,50% 75,70% 72,2% Non-defined All forms

of VAW 50,1

Hungary 50,90% 54,50% 42,5% Non-defined Missing 51,8

Ireland*

56,10% 71,20% 49,7% Non-defined All forms

of VAW 67,7

Italy* 38,80% 45,00% 68,0% Non-defined Missing 56,6

Latvia 61,10% 66,60% 39,8% Non-defined IPV/DV 56,2

Lithuania 75,40% 77,50% 72,1% Non-defined IPV/DV 54,2

Luxembourg* 72,00% 90,60% 59,1% Non-defined Missing 65,9

Malta 57,40% 72,70% 80,0% Non-defined IPV/DV 57,8

Netherlands* 68,20% 86,70% 34,2% Defined IPV/DV 74

Poland 54,60% 56,70% 34,0% Non-defined IPV/DV 56,9

Portugal* 61,50% 67,00% 72,9% Defined IPV/DV 54,5

Romania 61,30% 60,50% 60,8% Non-defined IPV/DV 51,2

Slovakia

48,40% 56,30% 31,7% Non-defined All forms

of VAW 52,4

Slovenia 75,30% 80,80% 64,3% Non-defined IPV/DV 66,1

Spain*

67,70% 77,20% 85,3% Defined All forms

of VAW

67,4 Sweden*

71,00% 72,40% 32% Defined All forms

of VAW

79,7 UK*

56,00% 69,00% 48,5% Defined All forms

of VAW 68,9

EU total 60,6% 69,7% 50,4% 65.0

with a NAP on IPV or DV. 43,4% of the women resided in states that had a NAP on all forms of VAW between 2000-2012. More than half of the member states scored under 60 in the GEI index (EIGE, 2017), indicating low levels of equality.

Table 3: Descriptive statistics for country-level variables.

N Valid %

Type of Legislation

Missing 1 500 3,6%

Existing but not defined 25 362 60,4%

Defined VAW Total 15 140 42 002 36,0% 100% Type of National Action Plan

Missing 5 456 13,0%

IPV/DV 18 321 43,6%

All forms of VAW Total

18 225 42 002

43,4% 100% Gender Equality Index 2012

Low (<59) 22 865 54,4%

Medium (60-69) 11 552 27,5%

High (>70) 7 585 18,1%

Total 42 002 100%

The results presented in table 4 indicate that there is a statistically significant difference (p<0,05) between awareness of preventative legislation and all country-level variables. Correspondingly, figures for awareness of protective legislation and the country-level variables showed a statistically significant difference. A statistically significant difference was also found between awareness of campaigns against VAW and all country-level variables.

The Chi-Square analysis showed that women residing in states with defined VAW legislation were more often aware of preventative- and protective legislation on DV than women residing in states with existing but non-defined legislation (65% vs 59%). The results for campaign awareness showed the opposite; women residing in states with defined VAW legislation were less often aware of campaigns than women residing in states with existing but non-defined legislation.

Further, as can be seen from table 4, the highest proportion of awareness of preventative legislation on DV and campaigns against VAW was found among women in countries with a NAP on IPV/DV. The highest proportion of awareness of protective legislation on DV was found among women in states with a NAP on all forms of VAW. The lowest proportion of awareness of both legislation and campaigns was found among women residing in states without any NAP on issues related to VAW.

Regarding equality, the Chi-Square Test showed that women residing in states with high GEI rankings were the most aware of legislation, but the least aware of campaigns. Correspondingly, women residing in states with low GEI rankings were the least aware of legislation, but the most aware of campaigns.

Finally, the test showed that women residing in EU15 states were more aware of preventative and protective legislation than women in new state members. Women in the EU15 were however slightly less aware of campaigns against VAW.

Table 4: Chi Square Test of Independence of country level variables and the differences of legislation- and campaign awareness among women in the EU.

Preventative Legislation Protective Legislation Campaign Awareness

Variable NO YES NO YES NO YES

National legislation on VAW Existing but not defined legislation

40,7% 59,3% 33,1% 66,9% 47,5% 52,5%

Defined VAW legislation 35,1% 64,9% 23,3% 76,7% 52% 48% NAP on VAW

Missing NAP 47,5% 52,5% 36,9% 63,1% 52,8% 47,2%

NAP on IPV/DV 36,8% 63,2% 30,2% 69,8% 45,3% 54,7%

NAP on all forms of VAW 37,5% 62,5% 26,1% 73,9% 52,3% 47,7% GEI Low (<59) 41,8% 58,2% 35,8% 64,2% 44,8% 55,2% Medium (60-69) 36,4% 63,6% 23,6% 76,4% 47,2% 52,8% High (>70) 32,5% 67,5% 20,3% 79,7% 64,7% 35,3% Membership Status EU 15 37,9% 62,1% 25,8% 74,2% 50,1% 49,9% New member 41,1% 58,9% 35,3% 64,7% 49,1% 50,9%

All conducted Chi-Square Tests indicated significant difference (p<0,05).

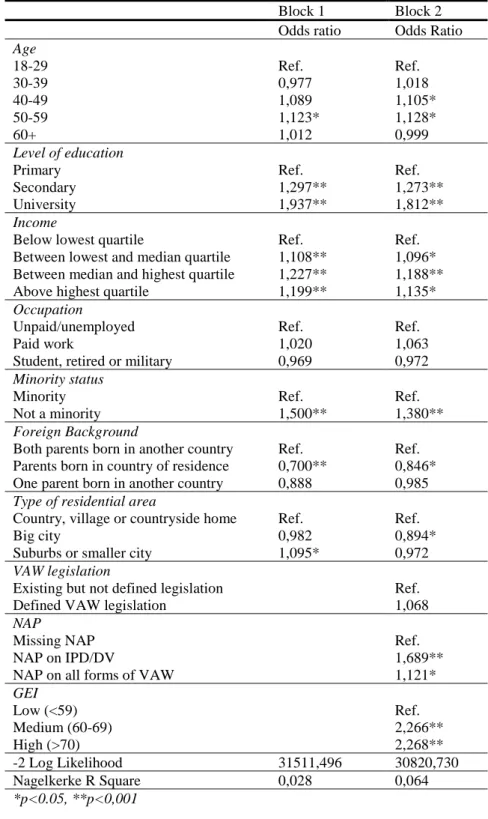

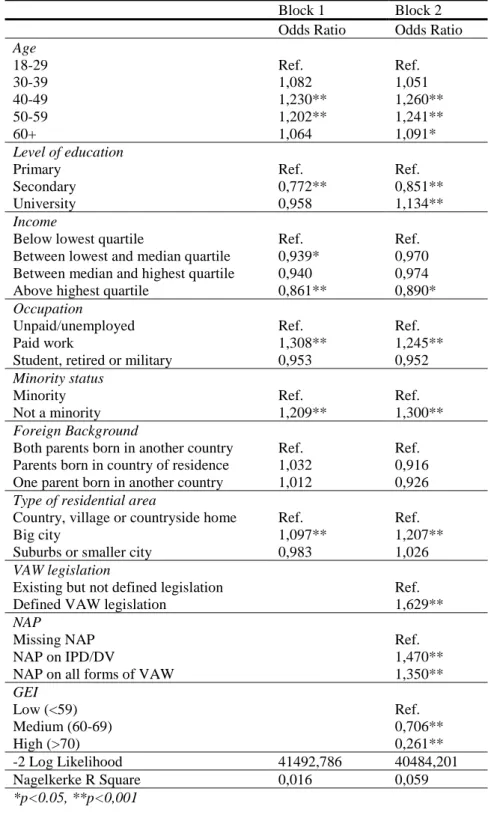

A binary logistic regression was conducted with two blocks for each outcome. The first block included individual predictors in terms of socio-demographic information. The second block added country-level predictors in terms of state conditions. Associations for awareness of preventative legislation on domestic violence and individual- and country-level variables are presented in table 5. Corresponding associations for awareness of protective legislation are presented in table 6. The associations for campaign awareness and the individual- and country-level variables are presented in table 7.

All three analyses indicated a significant and positive association between awareness and variables related to high socio-economic status (SES). Awareness of preventative and protective legislation on domestic violence and awareness of campaigns against VAW was higher among women with a university degree, women who received a salary and women who had a high income in comparison to other women.

With younger women as a reference category, women aged 50-59 were the most likely to be aware of preventative and protective legislation, while women aged 40-49 were the most likely to be aware of campaigns against VAW. Women living in a big city were most likely to have the highest awareness across all three analyses. Furthermore, women who did not consider themselves to be a part of a minority group were more likely to have higher awareness in comparison to minority women. Women with one parent born in another country were more likely to be aware of preventative- and protective legislation on DV than women with both parents born within or outside their country of residence. Associations between foreign background and campaign awareness were statistically

insignificant (p>0,05) as can be seen in table 7.

Most associations for the individual-level predictors were only slightly affected by the addition of country-level predictors in block two. There were minor variations, as the likelihood of awareness increased for all age groups except for the group of 60+ women in block two. The impact of level of education and income appeared

to somewhat decrease in the second block. In block two, the predictor ‘income between the lowest and median quartile’ became statistically insignificant (p>0,05) in table 5 and 7. Correspondingly in table 6, ‘suburbs or smaller city’ becomes statistically insignificant (p>0,05) in block two.

Women who resided in EU-states with defined national VAW-legislation were more likely to be aware of campaigns. However, the variable VAW Legislation was statistically insignificant (p>0,05) with regards to awareness of preventative- and protective legislation on domestic violence. Women who resided in states with a NAP on IPV/DV were the most likely to have the highest awareness across all three analyses.

Results indicated a distinct association between legislation- and campaign awareness with state members´ level of equality. Women residing in states with low equality rankings were the least aware of preventative and protective legislation, but more aware of campaigns than women residing in states with medium and high equality rankings. Correspondingly, women residing in states with high equality rankings were the most aware of preventative and protective legislation, but the least aware of campaigns. Nordic countries like Sweden, Denmark and Finland are examples of this, displaying high levels of equality but low percentages of campaign awareness.

Introduction of the country-level variables added explained variance in all three outcome variables. The decrease of -2 Log likelihood in all three analyses

indicates that the analyses improved when country-level predictors were added in block two. Correspondingly, the increase of Nagelkerke R Square in all three analyses indicates that the analyses improved when the country-level predictors were added in block two.

Table 5: Logistic regression analysis modelling awareness of Preventative Legislation in relation to individual and country level variabeles.

Block 1 Block 2 Odds Ratio Odds Ratio Age 18-29 Ref. Ref. 30-39 1,060 1,090 40-49 1,185** 1,204** 50-59 1,361** 1,364** 60+ 1,172** 1,157* Level of education

Primary Ref. Ref.

Secondary 1,175** 1,154**

University 1,686** 1,613**

Income

Below lowest quartile Ref. Ref.

Between lowest and median quartile 1,094* 1,070

Between median and highest quartile 1,263** 1,210**

Above highest quartile 1,350** 1,277**

Occupation

Unpaid/unemployed Ref. Ref.

Paid work 1,079* 1,089*

Student, retired or military 1,009 1,002

Minority status

Minority Ref. Ref.

Not a minority 1,150* 1,114*

Foreign Background

Both parents born in another country Ref. Ref.

Parents born in country of residence 1,070 0,879

One parent born in another country 0,825** 1,087*

Type of residential area

Country, village or countryside home Ref. Ref.

Big city 0,928* 0,932**

Suburbs or smaller city 0,979 0,880*

VAW legislation

Existing but not defined legislation Ref.

Defined VAW legislation 1,074

NAP

Missing NAP Ref.

NAP on IPD/DV 1,737**

NAP on all forms of VAW 1,190**

GEI Low (<59) Ref. Medium (60-69) 1,531** High (>70) 1,529** -2 Log Likelihood 33652,446 33341,482 Nagelkerke R Square 0,023 0,039 *p<0.05, **p<0,001

Table 6: Logistic regression analysis modelling awareness of Protective Legislation in relation to individual and country level variables.

Block 1 Block 2 Odds ratio Odds Ratio Age 18-29 Ref. Ref. 30-39 0,977 1,018 40-49 1,089 1,105* 50-59 1,123* 1,128* 60+ 1,012 0,999 Level of education

Primary Ref. Ref.

Secondary 1,297** 1,273**

University 1,937** 1,812**

Income

Below lowest quartile Ref. Ref.

Between lowest and median quartile 1,108** 1,096*

Between median and highest quartile 1,227** 1,188**

Above highest quartile 1,199** 1,135*

Occupation

Unpaid/unemployed Ref. Ref.

Paid work 1,020 1,063

Student, retired or military 0,969 0,972

Minority status

Minority Ref. Ref.

Not a minority 1,500** 1,380**

Foreign Background

Both parents born in another country Ref. Ref.

Parents born in country of residence 0,700** 0,846*

One parent born in another country 0,888 0,985

Type of residential area

Country, village or countryside home Ref. Ref.

Big city 0,982 0,894*

Suburbs or smaller city 1,095* 0,972

VAW legislation

Existing but not defined legislation Ref.

Defined VAW legislation 1,068

NAP

Missing NAP Ref.

NAP on IPD/DV 1,689**

NAP on all forms of VAW 1,121*

GEI Low (<59) Ref. Medium (60-69) 2,266** High (>70) 2,268** -2 Log Likelihood 31511,496 30820,730 Nagelkerke R Square 0,028 0,064 *p<0.05, **p<0,001

Table 7: Logistic regression analysis modelling awareness of Campaign Awareness in relation to individual and country level variables.

Block 1 Block 2 Odds Ratio Odds Ratio Age 18-29 Ref. Ref. 30-39 1,082 1,051 40-49 1,230** 1,260** 50-59 1,202** 1,241** 60+ 1,064 1,091* Level of education

Primary Ref. Ref.

Secondary 0,772** 0,851**

University 0,958 1,134**

Income

Below lowest quartile Ref. Ref.

Between lowest and median quartile 0,939* 0,970

Between median and highest quartile 0,940 0,974

Above highest quartile 0,861** 0,890*

Occupation

Unpaid/unemployed Ref. Ref.

Paid work 1,308** 1,245**

Student, retired or military 0,953 0,952

Minority status

Minority Ref. Ref.

Not a minority 1,209** 1,300**

Foreign Background

Both parents born in another country Ref. Ref.

Parents born in country of residence 1,032 0,916

One parent born in another country 1,012 0,926

Type of residential area

Country, village or countryside home Ref. Ref.

Big city 1,097** 1,207**

Suburbs or smaller city 0,983 1,026

VAW legislation

Existing but not defined legislation Ref.

Defined VAW legislation 1,629**

NAP

Missing NAP Ref.

NAP on IPD/DV 1,470**

NAP on all forms of VAW 1,350**

GEI Low (<59) Ref. Medium (60-69) 0,706** High (>70) 0,261** -2 Log Likelihood 41492,786 40484,201 Nagelkerke R Square 0,016 0,059 *p<0.05, **p<0,001

DISCUSSION

Results discussionThis study analyses to what extent women across the EU are aware of protective and preventative legislation on DV and campaigns against VAW in their countries of residency. The study then analyses correlates of awareness of legislation and campaigns among women across the EU. It must be emphasised that research

concerning legislation on VAW is scarce, and that research on awareness of such legislation appear to be non-existing within the EU.

When interpreting the results in this study, it is important to note that while the Istanbul Convention was signed in 2011, it came into force in 2014 (Council of Europe, 2011). As it is the most comprehensive regional instrument to address VAW, one can expect results from its implementation across EU state members that were yet to be seen when the 2012-FRA-VAW-Survey was carried out. Answers to posed research questions in the study will be presented below. The initial descriptive analysis of awareness of preventative and protective legislation on DV showed that women across the EU were slightly more aware of protective legislation than preventative. These results are quite logical, as most individuals probably learn about legislation after an occurrence of violence. Since 1 in 3 women in the EU are estimated to have experienced either physical or sexual violence, or both, after the age of 15 (FRA, 2015), it is fair to assume that many women, if not victimized themselves, may know of a victim or an incident of VAW.

Almost 1 in 2 women were unaware of recent campaigns against VAW, suggesting that campaigns against VAW were uneven across the EU. The

perceived need for campaigns is however a key factor, supporting Eliasson (1997) in her reasoning that the presence of reflecting social and political norms are required for VAW to be considered a crime.

Results indicated that women are more aware of legislation and campaigns against VAW in countries where progressive legislation and more comprehensive NAPs on VAW exist. States with progressive legislation and NAPs might carry out more campaigns and appear to be better at informing the public about legislation

compared to others. The results support the argument made by The European Women’s Lobby (2001) Observatory on VAW, emphasizing VAW legislation as an indicator of a state’s level of commitment and inclination to act according to advising legislation for the protection of women.

It is interesting that more than a third of women in Estonia stated that they were aware of preventative and protective legislation on DV within the country, since the country did not have any legislation addressing VAW. Estonia did however have a NAP on all forms of VAW in place between 2000-2012 which may have impacted these results.

Alarmingly, more than half of the EU member states demonstrated a low level of gender equality, with a score below 59 in the GEI. Results indicated a distinct association between legislation- and campaign awareness with state members´ level of equality, supporting urgings to emphasize gender equality in teaching materials made by the Istanbul Convention (Council of Europe, 2011). State level equality remains crucial regarding women’s ability to use information and

available resources, as it remains a matter of equal participation in society. The distinct association between equality and awareness of rights concerning VAW is in line with previous arguments on how VAW is rooted in women’s unequal status in society (Council of Europe, 2011; European Commission, 2010; Garcia-Moreno et al., 2014; Radford, 1992).

Women residing in states with low equality rankings were found to be less likely to be aware of preventative and protective legislation in this study. They were however more aware of campaigns than other women. This could be interpreted as a sign of recent state efforts to combat VAW. Correspondingly, women residing in states with high equality rankings were more likely to be aware of preventative and protective legislation, but the least aware of campaigns. This could indicate that a perceived need for campaigns against VAW is low in states with high levels of equality. It would be interesting to examine if campaigns are more frequent in states with low levels of equality due to an elevated perceived need.

No clear pattern was found on differences concerning legislation- and campaign awareness and state efforts to combat VAW associated with the duration of time states had been members in the EU. Results did suggest that new state members within the EU have pressing improvements to make in order to fulfil the goal of eradicating VAW.

When it comes to socio-demographic factors and awareness of legislation, results support previous research (Meager et al., 2002; Anderson & Sample, 2008), as awareness of preventative and protective legislation on DV and campaigns against VAW were more common among women who were older, had a university

degree, women who received a salary and women with a higher income.

The results showed that women aged 50-59 were the most aware of preventative and protective legislation, while women aged 40-49 were the most aware of campaigns. Results found in this study support the results of Meager et al. (2002) as they found that awareness peaked among individuals aged 36-45. In addition, the youngest and oldest age groups were the least aware, also supporting Meager et al.’s (2002) results.

Younger women appear to be an especially vulnerable group as they are both victimized at higher rates and less aware of legal rights. The Istanbul convention urges member states to emphasis gender equality in teaching materials (Council of Europe, 2011), but they should also add VAW legislation into teaching materials. Campaigns on VAW should target younger women and find new strategies to inform them of their rights as conventional measures seem to be insufficient. This group needs to be prioritised, as younger women can inform following

generations as they grow older, impacting awareness in society overall.

A similar urgency for prioritizing can be identified in women with low SES, as they have been recognised to be subjugated to violence at elevated rates by previous research (Beyer et al., 2015; Carbone-Lopez et al., 2012; Jewkes et al., 2002; Kiss et al., 2012; Wright, 2010). The results in this study suggest that they are also less aware of their legal rights. The argument of that education is a likely prerequisite for higher SES, instigating an ability to use information and resources available in society is supported by these findings. Educational attainment appears to be a key factor of awareness, as the present study found women with a

university degree to have the highest level of awareness on both legislation on DV and campaigns against VAW. These findings are in line with previous research (Meager et al, 2002; Anderson & Sample, 2008). Results showed that women who received a salary and had a higher income were more likely to be aware of

indicating that a higher level of income and higher-level occupations were

positively correlated with higher levels of awareness (Anderson & Sample, 2008; Meager et al., 2002).

Previous research has also highlighted that women in minority groups appear to be more vulnerable to violence than others (Caetano et al., 2008; Cunradi et al., 2000; Fernbrant, 2013; Raj & Silverman, 2002). Results in this study identified minority women to be less aware of their rights in terms of preventative and protective legislation and campaigns against VAW. Similarly, Anderson and Sample (2008) found that Caucasian women were more aware of legislation than women with other ethnicities. It is however difficult to generalise as results in the present study came from a sample where around 90% of women did not have a foreign background or were part of a minority group.

Results regarding type of residential area supported Anderson and Sample´s (2008) results, where women residing in cities were found to be more aware of legislation in comparison to women residing in rural areas. Women living in big cities had the highest awareness across all three analyses in this study. Campaigns might be more frequent in bigger cities compared to rural areas in terms of more posters, speeches, events etc. Further, universities and higher-level occupations are often located in bigger cities, possibly influencing levels of awareness. Methodological Considerations & Limitations

This study had certain limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings.

One limitation with the 2012-FRA-VAW Survey dataset is that samples can be diverse across state members, although FRA made great efforts to collect comparable data. The diversity of the sample could have implications for

generalisability and validity. Secondly, the sample appear to have been somewhat predisposed with a large underrepresentation of minority groups and of women with a foreign background. It is important to consider that a survey targeting a general study population inherently risks targeting groups in society that are easy to reach.

For the purpose of this study, it could perhaps have been interesting to include citizenship as a socio-demographic factor. One could presume that women without citizenship also would be less aware of legislation on VAW compared to other groups, due to their lack of legal rights. Citizenship was however discarded in this study since the sample contained an insufficient number of noncitizens. The lack of distinct definitions regarding VAW posed a great challenge throughout the research process. Implications of women’s understanding of violence and legislation may have affected the levels of awareness as FRA decided not to provide a definition of VAW to participants. Neither did they provide any information or definitions on the meaning ofpolitical initiatives and legislation preventing domestic violence or protecting women in cases of DV (FRA, 2014; FRA, 2019). Even though it is commendable that FRA restrained from restricting women’s understanding of violence, it made the analysis of their data more complex. The author did email FRA with inquiries on further

information of definitions andwas informed that respondents were not provided with any additional information or definitions (FRA,2019).

Without an explicit and coercive stance on VAW in the EU, finding reliable information on and interpreting legislation when creating variables was somewhat problematic. National legislation documents were in most cases not provided in English, and the author therefore chose to use information provided by the

European Commission as a main source. Even though some additional documents were used, majority of information regarding categorizations of state members dependent on legislation on VAW and NAPs on VAW can be found in the report Violence against women and the role of gender equality, social inclusion and health strategies (European Commission, 2010). Finding previous research on awareness of legislation in general was further very difficult, demonstrating that an evident research gap on awareness of legislation on VAW.

VAW remains a complex matter, and the present study merely touches upon macrostructural characteristics that can explain disparities regarding awareness of legislation on VAW. Going into further detail would have been outside the scope of this study, nevertheless, it would be interesting to see in future research.

CONCLUSIONS

The purpose of this study was to emphasize the importance of legal definitions of VAW and women’s awareness of their legal rights. The study examined if women across the EU were aware of protective and preventative legislation on DV and campaigns against VAW in their countries of residency. More explicitly, it investigated if women were more aware of their rights in countries with

progressive legislation, more comprehensive NAPs and higher levels of gender equality.

While research on prevalence and identification of vulnerable groups is imperative, legal definitions of VAW and awareness of legislation remain undervalued factors. Previously identified vulnerable groups were worryingly found to be the least aware of their rights. The present study found that the lack of an explicit and coercive stance on VAW within the EU was reflected in the National Action Plans and National legislation on VAW, as they were uneven and inadequate. Consequently, women’s levels of awareness of their legal rights and campaigns across the EU were uneven. States within the EU need to develop improved strategies on how to inform younger women, women with a low SES and women in minority groups about legislation on VAW. These groups also need to be prioritized and targeted when future campaigns against VAW are being carried out.

FRA´s decision not to provide any definitions when carrying out their survey contributes to presiding confusion. Women’s understanding of VAW is

inextricably governed by political and legal definitions, as they are required for VAW to be perceived as a crime. It is therefore imperative that the EU takes a clear stand and provides a definition of VAW as a directive for all its state members.

Despite deliberated limitations, this study carries important knowledge on correlates of awareness of legislation and campaigns among women across the

EU. To the author’s knowledge, it is the first study to investigate women’s

awareness of their legal rights regarding VAW on an EU level. The findings could bring important directives for future research as the significance of legal and political norms regarding VAW cannot be denied. For future research purposes it might be beneficial to investigate the association between legislation on VAW and country levels of equality more in-depth. Future research would also benefit from examining the impact of the Istanbul Convention on EU state members penal codes and policies on VAW. As the convention outlines preventative and

protective guidelines and urges member states to run awareness-raising campaigns on a regular basis (Council of Europe, 2011), it would be especially relevant in future studies.