J

Ö N K Ö P I N GI

N T E R N A T I O N A LB

U S I N E S SS

C H O O L JÖNKÖPING UNIVERSITYM a n a g i n g C h a n g e i n t h e

R e c o r d i n g I n d u s t r y

- response measures to the impact of downloading

Master thesis in Business Administration Author: Mattias Helgesson

Daniel Mattsson

Tutor: Leif Melin

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Managing Change in the Recording Industry Authors: Mattias Helgesson, Daniel Mattsson

Tutor: Leif Melin

Date: May 2005

Subject terms: Change management, MP3-downloading, discontinous change, music industry, strategic change

Abstract

Since 2001 the recording industry has lost a third of its total sales and the future of music consumption is almost daily debated in media. On one side there are voices proclaiming free downloading and music sharing over the Internet and on the other side there are artists and record companies explaining that they need the revenues to survive. A currently delayed law proposal to illegalise unauthorized downloading, planned to be implemented from July 2005, is being considered by the Parliament. The future outcome is uncertain, but the music industry is currently and unquestionably experiencing big change.

The purpose and intention with this thesis is to examine how major record companies in Sweden are managing the environmental change, imposed by downloading over the Internet, focusing on strategic choices, actions and organizational change implemented by subsidiary level top management.

We have used previous research and theories within the area of strategy and change management as a platform for analyzing what approach these companies have to this phenomenon and also what measures have been implemented since the problem was first recognized. In Stockholm we met with representatives from the three largest record companies in Sweden; EMI Sweden, Universal Music and Sony BMG. Our data was collected from these interviews, which were based on our questions referring to different parts of the management process when experiencing big change.

One conclusion we have drawn is that the reaction from the recording industry has been too slow in order to fully capitalize on the possibilities in music distribution over the Internet. The reasons for this are many, but their relatively static structure and the fact that they have been caught up in old patterns are certainly part of the explanation. However, even though the record companies were somewhat slow from the beginning, they have now caught up substantially and since many of the measures suggested by previous research have been implemented, they are now to a larger extent equipped to meet the future needs. This thesis contains more specific elements on what responses to downloading the record companies are currently working with, such as restaffing procedures, rethinking the operational environment and reshaping strategies.

Magisteruppsats i Företagsekonomi

Titel: Managing Change in the Recording Industry Författare: Mattias Helgesson, Daniel Mattsson

Handledare: Leif Melin

Datum: Maj 2005

Ämnesord: Change management, MP3-nedladdning, discontinous change, musikindustrin

Sammanfattning

Sedan 2001 har skivindustrin förlorat en tredjedel av sin totala försäljning och framtiden för musikkonsumering är näst intill dagligen debatterad i media. På ena sidan finner man förespråkare för fri nedladdning och fildelning över Internet, medan den andra sidan består av artister och skivbolag som förklarar att man inte kan klara sig utan intäkter för musiken som produceras. Ett försenat lagförslag, ämnat att träda i kraft i juli 2005, som skulle förbjuda nedladdning av otillåtet material på Internet behandlas just nu av riksdagen. Framtiden är oviss, men det råder inga tvivel om att musikindustrin just nu undergår stora förändringar.

Syftet och avsikten med den här uppsatsen är att undersöka hur stora skivbolag i Sverige hanterar de omvärldsförändringar som skett till följd av nedladdning över Internet. Vårt fokus ligger på strategiska val, aktiviteter och organisatoriska förändingar som implementeras av ledningsgrupperna på respektive företag.

Vi har använt oss av tidigare studier och teorier inom strategi och change management som en plattform för att analysera företagens aktiviteter och inställning till nedladdningsfenomenet sedan problemet identifierades. På deras respektive huvudkontor i Stockholm intervjuade vi representanter från de tre största skivbolagen i Sverige; EMI, Universal Music och Sony BMG. Datan som samlades in baserades på de frågor vi formulerat med hänvisningar till olika delar av managementteorin som behandlar diskontinuerlig förändring.

En slutsats som vi dragit är att skivbolagen reagerat för sent för att till fullo ta tillvara på möjligheterna som musikdistribution over Internet trots allt besitter. Anledningarna är många, men deras relativt statiska strukturer och det faktum att man varit fast i gamla mönster är en stor del av förklaringen. Trots att man från skivbolagens sida reagerade ganska sent på förändringen så har man nu hunnit i kapp utvecklingen avsevärt och efter att ha tagit många strategiska steg på rätt väg är man nu till en större utsträckning förberedd att möta framtida behov. Den här uppsatsen innehåller mer detaljer och specifika element av deras strategiska respons, bland annat personalbyten, tydligare omvärldsanalyser och strategiförändringar.

Table of Contents

1

Introducing the area of research ... 1

1.1 Problem Discussion...2

1.2 Purpose ...3

2

Previous research and theories of relevance... 4

2.1 The Core of Strategy ...4

2.1.1 Two different perspectives...5

2.1.2 Organizational resources...6

2.2 Developing competitiveness ...7

2.2.1 Dynamic capabilities...7

2.2.2 Same game vs. New game ...8

2.2.3 Hyper competition and the importance of flexibility...9

2.3 Change management ...10

2.3.1 Varieties of change...10

2.3.2 The PESTEL Framework...11

2.3.3 Discontinous and frame-breaking change ...12

2.3.4 Generating new ideas...14

2.3.5 Response failures...15

3

A reflexive case study approach ... 16

3.1 Reflexive methodology ...16

3.1.1 Data-oriented methods ...16

3.1.2 Hermeneutics ...17

3.1.3 Critical view ...17

3.1.4 Poststructuralism and postmodernism...17

3.1.5 Our reflexive methodology...17

3.2 The case study approach to the downloading phenomenon ...18

3.3 Semi-structured interview ...19

4

Empirical data ... 20

4.1 EMI Sweden ...20

4.2 Universal Music Sweden ...25

4.3 Sony BMG ...28

4.4 Reflections on our empirical findings ...31

5

Analysis ... 33

5.1 Environmental analysis - PESTEL...33

5.2 The Discontinuous Change Process ...34

5.2.1 Recognition ...34

5.2.2 Strategic choices and Organizational Redesign ...35

5.3 Alternative solutions ...40

5.4 Analytical reflections...41

6

Conclusions ... 42

References... 47

Appendix 1... 50

Figures

Figure 2-1 Same game vs. New game (Ellis & Williams, 1995)……….. 9 Figure 2-2 Grundy´s three varieties of change (Senior, 2001)………10 Figure 2-3 The PESTEL Framework (Johnson et al., 2005)………11

1

Introducing the area of research

In the 21st Century the competitive landscape for most companies look somewhat different from what we have experienced towards the end of the last century. It is an environment marked by constant and unpredictable change, often seeing revolutionary and discontinous changes which affect the entire structure of all organizations (Kuratko & Welsch, 2004). It is a well known fact in management theory that in order to survive, companies and organizations must adapt to and interact with the changing environment. All organizations are faced with a large number of factors that to different extent interfere with the current way they conduct their business. Each and every one of these factors are in themselves an incentive for organizational change (Stoner & Freeman, 1992). Forcing organizations to act in order to stay competitive, these factors are generally referred to as triggers for change and are grouped into four subcategories where technological factors today is the category that have come to play an ever increasing role (Johnson et al., 2005). Hence, understanding the importance of change management is essential. Seizing opportunities and sidestepping pitfalls that comes hand in hand with change is best achieved through leveraging strategies, operational processes and organizational structure (Kuratko & Welsch, 2004).

The Internet is often regarded as the most powerful technological trigger since it normally influences all activities in a company. Managing the opportunities the Internet can offer is crucial for any company that wishes to remain competitive. Emphasis is often on reviewing possible improvements within Internet-based communications. The big majority of companies view Internet as a tool, as something very useful, something capable of improving communication channels, operation processes and marketing procedures (Senior, 2001). However, there are also a few industries where the Internet has become so much more. It has grown to be a possible threat while at the same time also a necessary ingredient in a recipe for survival. We are talking about the music industry in particular. According to IFPI, the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (2004), the Swedish record sales has dropped 33% since 2001 in absolute numbers. Accompanied by the film-industry, the music industry is believed to have suffered severely due to the high increase in free downloading over the Internet. Since 1999 when the file sharing network Napster became worldwide-known to the public, concerns with MP3-downloads have been frequently discussed in the news and it has become an issue drawing everyone’s attention. In the Napster trial, evidence was presented by the prosecutor saying that downloading was indeed harmful to the recording industry, while the defender showed proof of the opposite. According to Stan Liebowitz (2004) it cannot be stated for sure that the decrease in record sales can be fully blamed on the downloading phenomenon, leaving the door open for other contributing factors.

Since the early days of downloading our legal system in Sweden has not been able to provide sufficient protection of companies that might be negatively affected. As the law is stated today, you are not allowed to provide files for others to download, but you are allowed to download from others. However, in July 2005 there will supposedly be a change in this law, making it illegal to also download files/MP3s from others (Brandel, 2005). Of course, if this law is implemented it has the potential of having a positive influence on sales for the recording industry. It is an interesting thing to look at the practice of the recording industry today. The common view among the general public seems to be that record companies try to fight back by prosecuting Internet users who have unauthorized material available for others to download (Liebowitz, 2004). However, this is most certainly only a small part of the overall strategy.

1.1 Problem

Discussion

With this thesis we attempt to dig a little bit deeper into the recording industry. It is certainly a unique situation they are facing, as they are up against a new abstract artificial competitor, a phenomenon that might threaten the very core of their businesses. This thesis is designed to provide an insight to the thoughts and actions within three of the biggest record companies that are present in Sweden; Universal Music, Sony BMG and EMI. Focus will be on change management, how they handle the phenomenon of MP3-downloading strategically both internally and also externally focusing on alternative ways to improve sales.

Below we specify four main themes/questions that will be the core of this thesis. They will be the foundation on which we will base our empirical research. We are going to perform an analysis on these themes, using the theories that are later presented in chapter two as our framework. The conclusions we draw from the analysis will be presented in the final chapter. First of all, in order to understand the problem from the record companies’ perspective:

• What are the general views among major record companies on the recent years’ development with MP3-downloading? What threats and possibilities do they see?

At the centre of the controversy is the notion that the recording industry is afraid that downloading will cause mortal damage to them, unless they can somehow stop online “trading” (Liebowitz, 2004). We would like to raise a question mark to this notion, asking if they really see themselves falling with the survival/death of MP3-dowloading. After all, they are currently in a phase of obvious change and many previous real-life cases highlight several proper actions/measures to follow/implement in order to improve one’s situation (Kuratko & Welsch, 2004). Our major focus in this thesis will be to highlight the important elements of the change process, asking:

• Given existing theories and previous research on change management and strategy, are they taking appropriate measures to respond efficiently to the changing environment?

Comparing the phenomenon of downloading music to the CD, another obvious area of interest for us is the benefits inherent in buying a CD. There is obviously some value in a CD that you cannot retrieve from downloading the songs from the Internet. Asking what the recording industry can offer but downloading can not, is a central question in order to understand the forces behind the strategies that they have for the future:

• What is the future of the CD as a medium? What ways are there to take advantage of the added value inherent in a CD, compared to downloading? Is alternative ways of selling music something that will be at the core of every major companies strategy in the future? It certainly seems as downloading is here to stay and in order to remain competitive as a music producing company core-changing actions would in that case have to be taken (Liebowitz, 2004). The question is how the recording industry views the future and to what extent they are prepared to pursue alternative ways to sell music to its customers:

• Do they have concrete ideas on how to regain “market shares”, focusing on alternative ways to sell music using Internet as a tool? What are they and to what extent are they being/will they be implemented?

There have been few studies on this area before, since the phenomenon of MP3-downloading is relatively new. This is why the area provides an interesting natural experiment for any economist.

1.2 Purpose

Our intention is to examine how major record companies in Sweden are managing the environmental change, imposed by downloading over the Internet, focusing on strategic choices, actions and organizational change implemented by subsidiary level top management. .

2

Previous research and theories of relevance

This chapter focuses on research and literature that will help us analyze the data gathered from our chosen companies. Analyzing how they are managing the current situation requires that we apply established managerial guidelines within the area of strategy and change management, theories that can hopefully help us to answer our questions.

As was touched upon in the introductory chapter the competitive situation the recording industry is facing today is in many ways unique in a sense that they are up against a substitute that their customers can get for free. There are little if any literature or models that explicitly describe this sort of problematic area, leaving us with theories that might not in all cases be suited and applicable to our research. It is important that the reader understands that focus in this thesis is not on the competitive battle between firms in the music industry, but instead on the competition from downloading. There are vast amounts of strategic literature and specific models describing strategic management in the face of a changing environment, but a major part of them are based on the assumption that your opponents are rational human beings who react and act accordingly. Hence, we have focused on theories that with no doubt have relevance in any setting where change and strategy is at core of the study. Besides, we are aware that diving into theories that are only marginally touching upon certain aspects of our situation of interest, but in fact are designed for analyzing completely different scenarios, would lower the credibility of this thesis.

Initial focus will be on strategy and different perspectives on how to look at this area of economic theory. We describe general views on strategy, reviewing important concepts for this thesis such as the ‘dynamic capabilities’-concept and new game vs. same game theory. We move on to the area of change and what characterizes settings undergoing radical change. Since focus in our analysis will be on the change process, the theories on change are slightly more relevant for our purpose than the ones on strategy, explaining the fact that we have kept the theories on strategy fairly general. By linking change to strategy we later examine what strategic choices managers face in the light of competition and environmental change and what appropriate actions are suggested to various aspects of the change process.

2.1 The Core of Strategy

There is no single accepted definition that covers all aspects of strategy. It is a concept that is present in everything an organization does and not separable from anything. To get an overview of what strategy can be about we use Henry Mintzberg’s framework (Burnes, 1996). Mintzberg uses what he refers to as the five P’s to define strategy. They represent five different ways to look at the concept:

● Plan Explicitly or implicitly having a plan which the organization will follow. ● Position Seeing strategy as how a specific product/service is positioned on

particular market to use it for competitive advantage.

● Perspective Taking an internal view on the organization’s own way of doing things, regarding people and processes. Strategic actions need to be related to the organizational culture.

● Pattern Seeing strategy as a pattern of behaviour over time, regarding assessments and evaluation and processes.

● Ploy Using strategy as a manoeuvre to outwit your competitors. Threatening to lower prices to keep new entrants out of the market is one example of this.

Mintzberg says that one perspective does not rule out another in this model. They are all useful in a sense of adding width to the concept of strategy and to create a discussion around it. Meanwhile, they can be seen both as complements and alternatives to each other (Ellis & Johnson, 1995).

However, while there seems to be an endless amount of theories regarding strategy there are only three different groups of models that are really applicable to reality (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997). These are the competitive forces view, the strategic conflict view and the resource-based

view. In the forthcoming sections we outline these groups of views, in order to create an

understanding of what different aspects there are on the area of strategy. Reviewing the content of the separate strategic schools we have chosen to put more emphasis on the resource-based view. The reason for this is that the two others pay little attention to skills, path dependencies, know-how and are to a larger extent focused on the competitive battle with other firms, whereas the resource-based is concerned with internal strengths and capabilities (Teece et al., 1997). Since this study is more focused on the internal capabilities of the record companies in handling competition from a phenomenon rather than actual competitors, this distinction was made. However, there are also two contributing ideas taken from the competitive forces view and the strategic conflict view that will be highlighted in section 2.1.1. We will not look into distinguishing features of the prescriptive and the analytical stream of thought within management, as it is not relevant for the purpose of this thesis.

2.1.1 Two different perspectives

The competitive forces approach

According to the competitive forces view it is essential to align the organization with the environment. Proponents claim that the industry sets the rules of the competitive game and indirectly therefore influence the range of strategies available to the competitors (Burnes, 1996). Further, it focuses on what actions a firm can take in order to create positions that are effective against competitors (Johnson et al., 2005).

The most influential writer in this area is Michael Porter who claims there are really only three generic strategies companies can pursue: low-cost, differentiation and specialisation by focus. They are all based on his “five forces” framework which was created to determine the industry potential within a firm. Entry barriers, threat of substitution, bargaining power of buyers, bargaining power of suppliers and competition among competitors, are all forces to take into account (Christensen, Anthony & Roth, 2004).

We would like to highlight the differentiation approach, which says that an organization only can gain sustainable advantages through a constant search for new markets and to exploit them (Christensen, Anthony & Roth, 2004). Porter further points out that the firm’s ability to be profitable is in direct relation to its ability to influence the forces in the industry. This idea can be connected to the well-known contingency theory which states that all organizations are open systems where performance is dependent on circumstances and forces affecting each organization. Thus, there is no best way to follow for all organizations (Burnes, 1996).

The strategic conflict approach

Using the tools of game theory, the strategic conflict approach focuses mainly on the competitive interaction between rival firms (Teece et al., 1997). A big part of the research under this approach lies on the assumption that manoeuvres are made depending on what one firm thinks another one will do in a specific situation. Hence, the level of economic performance is a consequence of the firm’s ability to outsmart its rivals (Burnes, 1996). An interesting aspect with this approach is the idea that you by taking certain actions can influence the market environment (Teece et al., 1997). Doing this successfully can increase your profits substantially. Common strategies to influence the market and gain customers include price strategies, advertising and investments in capacity (Burnes, 1996).

However, it is important to realize that these conflict-based strategies do not take into account the wide range of both internal and external factors that of course also affect the competitiveness of a firm. Hence, the usefulness of this approach is limited (Burnes, 1996).

2.1.2 Organizational resources

Emphasis in the resource based view on strategy is on internal resources and to what extent firm-specific capabilities work to take advantage of these endowments (Teece et al., 1997). Burnes (2000) claims that, since gaining new competitive capabilities and resources is hard to do, firms are pretty much stuck with the endowments and resources that they already have. Hence, internal management is crucial to economic performance. The emphasis on managerial capabilities and different organizational skills leads to an approach which integrates many areas of management and strategy research such as management of R&D, human resources, intellectual property and organizational learning. The organizational capabilities of a firm are defined as its ability to accomplish against competition and circumstance, whatever it sets out to do (Teece et al., 1997).

Also, in an industry where innovation has become a powerful presence in the form of computers and the Internet, there is constant creative destruction at work (Durand, 2004). Touching on the area of change, Durand highlights the need for all companies to respond to change, something that normally goes hand in hand with the disruption and re-evaluation of current operational processes and organizational strategies. In a situation where a line of business is about to be redefined, there are no established rules for how this competitive game will be played. Instead the rules will be a result of the deconstruction-reconstruction process that will take place. What this means from a strategy point-of-view is that there is an opportunity for involved actors to take action in order to shape these new rules. In order to do this, a firm needs to exploit its resources and respond to opportunities in the environment. As Durand (2004) puts it, making an analogy to the medieval alchemists:

“In medieval times, alchemists were seeking to turn base metals into gold. Today managers and firms seek to turn resources into profit. A new form of Alchemy is needed in the organization. Let’s call it competence” (Durand, 2004, p.126)

The concept of core competence was first highlighted by Hamal and Prahalad in 1990 and really made a major contribution to the resource-based view on strategy (Durand, 2004). For a resource to be classified as a core competence three criteria have to be met:

● It offers real benefits for the customers. ● It is difficult to imitate.

● It provides access to various markets.

If a company can create a unique combination of their core competences, there is a good chance they can achieve some sort of competitive advantage. The degree to which a core competence is distinctive depends on how well endowed the company is relative to its competitors (Teece et al., 1997)

Porter is of the same opinion, saying companies must put their core competence in the centre of strategy in order to stay competitive (Burnes, 1996). Meanwhile Ellis and Johnson (1995) claim positioning can no longer be considered as a choice of strategy. To remain competitive in a fast-changing industry, companies must balance their competitive edge, their core competence, with an ability to constantly adjust to changes. Hence, the environment prevents companies from being too static.

Doing what you are best at is an old idea that can be trailed back to the theory of comparative advantage. As was previously mentioned, many proponents of the resource based view believe an organization is stuck with the capabilities and endowments it possesses. This is not something that can be easily acquired. Therefore you have to figure out what your edge is, what you have that can be turned into an advantage and then simply focus on that area (Burnes, 1996). However, the resource based view also invites consideration of managerial strategies for developing new capabilities, which brings us to the concept of dynamic capabilities (Teece et al, 1997).

2.2 Developing

competitiveness

The traditional stable business-environment does not exist anymore. Today the competitive environment is characterized by technological change, competitors that emerge from places previously unknown and a higher degree of globalization. In addition to the resource based view, Duyster, Nagel & Vasudevan (2004) put forward a theory saying that not only should a company deploy its resources in the most efficient way, it also has to view the capability to alter the rules of the game as an asset in itself. Hence, the challenge for companies in changing industries is to find the means by which they can “develop a capability for changing the rules of the game” and also to be flexible in the face of new ideas.

2.2.1 Dynamic capabilities

Resource based ideas become particularly interesting in a context where technology plays an important role and that is what has happened recently in many industries. Flexibility is a key feature often mentioned when talking about the new rapidly changing environment we often encounter. As a result, consumers have a wide range of choices, making the chances of establishing a sustainable competitive advantage based on durable competences very slim. Meanwhile, we can often see companies that extend during a period of change (Johnson et al., 2005). Hence, they must possess an asset that gives them an edge in a changing environment.

Teece et al. (1997) introduced the concept of “dynamic capabilities” as an extension of the resource based view but with tighter focus on the importance of adaptability in a changing environment. The term ‘dynamic’ refers to the capacity to renew competences in order to meet the needs of the changing environment, while ‘capabilities’ emphasizes the role of the manager to adapt and reshape the internal skills of the organization. All choices that are made by a manager today puts a limitation on what will be the internal toolbox when adapting to changes in the future (Teece et al, 1997).

These capabilities can vary very much between different companies, they can be formal or informal. Examples of formal dynamic capabilities are organizational systems for new product development or major strategic moves, such as an acquisition of another company in order to widen the knowledge of the organization. On the other hand they might be very informal such as in the way decisions are made, how to speed up the process if necessary and how to deal with particular circumstances that require innovation (Johnson et al., 2005).

Eisenhardt (2000) makes an important point regarding acquisition procedures, saying that the chance of being successful after a merger depends on how well the new organization can capture synergies.

2.2.2 Same game vs. New game

Both of the approaches described in this section work to achieve a competitive advantage; that is, to be able to outperform rivals in the market over a consistent period of time, given commonly accepted criteria (Ellis & Williams, 1995). Even though our focus is not on the competition among the record companies, we have chosen to include this theory. We believe it fills an important function, giving a perspective on the type of competition that in fact exists.

According to Ellis and Williams (1995) business strategy is by definition “how a business seeks to compete in its chosen product-markets”. Organizations can basically compete by approaching strategy in two ways:

- Taking an already existing concept of strategy, i.e. a competitor’s, and then try to do it more efficiently and more successful. This is called same game strategy. (Ellis & Williams, 1995).

- Creating an innovative new strategic way and benefiting from first mover advantage. This is intuitively called new game strategy (Ellis & Williams, 1995).

Studies have shown that same game strategies often result in “cutting down on costs”- behaviour, a situation that often just leads to harder and harder head to head competition and no real progress for any of the competitors. If the conditions under which competition takes place become less appropriate, it is likely to result in a business that is doing just worse. Meanwhile, when following a new game strategy, you avoid head-to-head competition and instead concentrate on trying to outflank your opponent in areas where you think you can provide better value for the consumers. Thus, new game strategies are about building rather than cutting. Emphasis is on developing new markets, market features and competitive approaches (Ellis & Williams, 1995).

Figure 2.1 gives an overview of what the characteristics, strategic intent and potential outcomes are in each of these approaches.

Same game New game

Characteristics

► Identify market segments.

►Decide positioning within segments. ►Serve market more efficiently and

effectively than the competitors.

Characteristics

►Strategic innovation; product, process or

market discovery.

►First mover advantage within a market. ►Avoidance of head-to-head competition. Strategic intent

►Outcompeting rivals using similar

strategies to those carried out by the rivals. The aim is to assess competitors’ actions and do the same thing better.

Strategic intent

►Outcompeting rivals by investing in new

strategic solutions. Emphasis is on innovation and vision, as the organization sets out to create a new approach to meet consumer needs.

Potential outcome

►Achievement of parity or an

incremental competitive advantage when compared to rivals.

Potential outcome

►Achievement of a competitive superiority,

which gives the organization a distinct advantage when compared to competitors.

Figure 2-1 Same game vs. New game (Ellis & Williams, 1995).

2.2.3 Hyper competition and the importance of flexibility

The level of competition can vary widely between different industries. One concept that is frequently used when describing an environment where the competitors are constantly aiming for leadership is hyper competition. What forces an industry into this state is normally a growing operational complexity and a fast rate of innovation carried out by companies seeking competitive advantages. However, these advantages are generally only temporary and what really makes a company successful in this environment is its ability to satisfy customer needs (D’Aveni, 1998). The underlying assumption here is, that to gain a sustained competitiveness in this type of environment you need to engage in a sequence of short-term moves that hopefully will lead your company through the turbulent times (Johnson et al., 2005).

Chakravarthy and Gargiulo (1994) argue that competing in a hyper competitive environment requires a flat entrepreneurial organization where the two most important attributes has to be the ability to achieve a culture of trust and empowerment among the employees. Entrepreneurial strategies have to be encouraged and prioritized while at the same time be flexible in an unexpected event of failure of a chosen course of action. The last part here is something that they emphasize in particular, especially since the window of opportunity in this type of environment normally is very brief. If the organization is too hierarchical, changing the course of action once set becomes very difficult.

Senior (2001) states that organizations have different structures depending on whether they operate in a stable market or in a dynamic and frequently changing market. She mentions studies conducted on this area that has shown that mechanic and bureaucratic structures are more suitable to a stable environment, while organic and decentralised structure are more fit to dynamic environments.

Everyone within an organization may be capable of being innovative, especially if they are put together in a group. But according to Bessant (2003) we can in reality see several elements in average day business life that work to suppress this innovative behaviour. Employees may feel that innovation is not part of their job and that it is part someone else’s. They might feel a bit anxious about expressing new ideas. Out of fear for what other employees will say they may feel it is not worth the effort. Maybe there are no incentives whatsoever within the organization for this sort of behaviour, maybe there is no time, suitable structures or procedures to support it. This is a challenge for the management team. To first communicate the direction of the company and then carry out all necessary actions to make the entire organization, people as well as structures, work towards this same goal. Routines have to be established that allow development of skills, expression of ideas and innovative behaviour in general (Bessant, 2003).

2.3 Change

management

2.3.1 Varieties of change

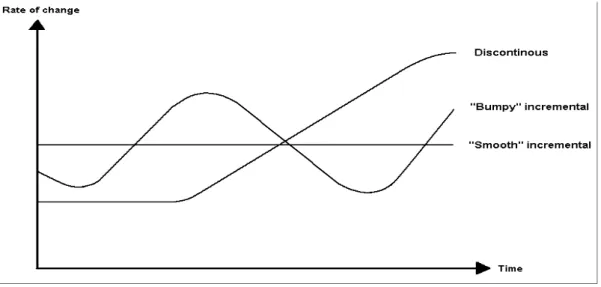

There are many different forms of change and there are many different views among managers what change is. Some consider change to be an enemy of stability, while others realize the opportunities that comes with it (Senior, 2001). One model that has been frequently used when describing different sort of change is Grundy´s (1993) three varieties of

change as shown in figure 2.1 below.

Figure 2-2 Grundy´s three varieties of change (Senior, 2001)

According to Grundy (1993), smooth incremental change is when it is easy to predict the future. The figure indicates that the rate of change stays on the same level and there are no sudden or radical changes whatsoever. Bumpy incremental change is characterized by a lot of ups and downs in the rate of change, caused both by external and internal factors. External factors include all triggers that will be mentioned in the next section describing the

PESTEL-framework. Internally, the change can be driven by reorganizations, measures to improve efficiency and working procedures (Grundy, 1993).

Discountinuous change is the third type of change. When a business or industry is forced to

adjust their strategies, structure or culture due to an environmental situation that is permanently changing, we have a situation of discountinous change (Grundy, 1993). More about this type of change will be covered in section 2.3.3.

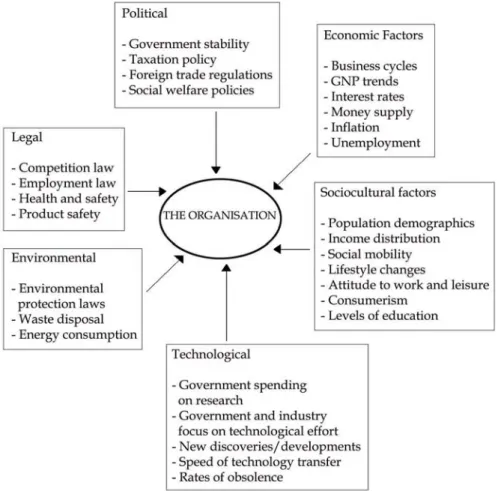

2.3.2 The PESTEL Framework

Senior (2001) says that the discontinous change process as well as other types of change are always triggered by a specific or a number of environmental factors. Analysts have found it useful to group these different factors into several categories depending on their characteristics. The groupings look slightly different but basically have the same meaning. Johnson, Scholes and Whittington (2005) classified these factors in six groups and named the framework PESTEL. The six letters are short for political, economical, sociocultural,

technological, environmental and legal. Using this framework will help create an understanding of

the forces affecting an organization experiencing environmental change.

Figure 2-3 The PESTEL Framework (Johnson et al., 2005)

The main purpose with the PESTEL framework is to identify the key drivers of change. Many of these are linked together, but they all represent macro-environmental factors that are likely to affect the structure of a sector, market or industry. Johnson et al. (2005) further state that for most organizations it is the combined effect of just some of the factors, rather than all of them, that are important. The authors further stress the importance of using the

framework proactively, looking at future aspects of the impact of the environmental factors.

2.3.3 Discontinous and frame-breaking change

Nadler (1998) describes discontinous change as a process of five stages under which business leaders have to manage three core challenges. The first challenge is a matter of

recognition, asking whether the organization has the ability to fully recognize new threats

early enough to create a response. As a leader, can you make the right choices so that your organization can survive or even make a profit from the new situation? This is the second challenge named strategic choice. Thirdly, is the organization capable of reshaping the core components in order to fully pursue this new strategic direction? Is organizational redesign possible without posing a too big threat to the survival of the company?

A different framework for change than Grundy’s was put forward by Tushman, Newman and Romanelli (1988). Different from Grundy, their framework is based on empirical results from several studies and emphasis is on the rapid implementation process. They claim most organizations conduct two types of converging change within, that is fine-tuning and incremental adaptations. Both types are actions done due to changes in the environment with the aim to maintain the relationship between organizational processes and strategy, though incremental adaptation is considered a somewhat larger adjustment. However, as the organization’s environment undergoes large changes, conducting incremental adjustments might not be enough. Instead severe changes in strategies, structures and activities might be necessary, a procedure Tushman et al. (1988) call frame-breaking change. Going back to Nadler’s (1998) framework, the three mentioned challenges are constantly present over the discontinous change cycle which can be broken down into shorter stages. The first stage emphasized by Nadler (1998) is recognizing the change imperative, meaning you carefully have to examine all components of the organization in order to see what is working and what is not and also to identify the causes of the change.

When recognizing the magnitude of the problem the next important step will be to develop a

shared direction, a direction that can be supported by the entire management group. It is

essential to have support when engaging on an endeavour that will change the entire essence of the organization. Nadler (1998) claims here is where many impatient top executives often make their first mistake, not realizing that having everyone on board from the beginning prevents major time delaying corrections in the chosen plan in the future.

Implementing change is the third step really overlapping both previous and upcoming stages.

You can also say that the major part of the frame-breaking process presented by Tushman et al. (1988) takes place during this stage. Clearly, implementing change is a complex procedure involving many core activities necessary to succeed in realizing the goals you have set for yourself. According to Nadler (1998) and Tushman et al. (1998) the primary focus in the process of frame-breaking change should be on:

• Redefining strategy and rethinking the nature of the work required to pursue the new strategy. Core values and the company’s mission are normally revised and changed to match the needs of the future.

• Redesigning the organization’s formal structures, systems and processes.

• Rebuilding the operational environment of the organization and creating informal arrangements that support the new strategy and work requirements.

• Restaffing: making sure the right people are in the right jobs in keeping with the new strategy, structure, work and culture.

To perform a successful process of frame-breaking reshaping of an organization, speed is absolutely necessary. Otherwise the organization might end up in a situation where losing market shares are inevitable. Most frame breaking reorganizations involve a few or all of the features mentioned above (Senior, 2001).

Frame-breaking change is quite revolutionary in that the entire nature gets reshaped. To work effectively it requires continuous change in strategies, structure, capital and processes and more importantly; it has to been done simultaneously and rapidly. There are several reasons to why that is. The most important one may well be the riskiness and the vulnerability that the company faces during the restructuring period. Longer implementation means higher uncertainty. Therefore there is also a constant need of actions from management that send signals throughout the organization that things are in motion, that progress is achieved. Who manages the transformation is an important issue, since it requires both talent and energy. There is a dilemma when choosing the executive, since the current executive may be the one with the widest knowledge of the company but he may lack the energy and the passion for carrying out such an internal revolution. Meanwhile, a fresh set of executives in the management team could bring new skills and a different perspective to the table. Studies show that when frame-breaking change has been combined with executive succession, the company performance has been significantly higher (Tushman, Newman & Romanelli, 1986) Another reason to why speed is important is the synergies you can take advantage of when all parts of an organization work together along the same guidelines (Tushman, Newman & Romanelli, 1988).

The fourth stage in the discontinous change process is consolidating change. This phase starts when the activities that were once radical and new, now is part of the everyday procedures of the organization. During this phase it is crucial to diagnositisize and evaluate what is working properly and what is not and then make refinements. Management can reward proponents of the new status quo and remove those who are still resisting (Nadler, 1998). Finally, when things seem to be working correctly, you would like it to stay that way, hence

sustaining change will be the last part of the discontinous change cycle. A threat during this

phase is that the organization might gear down a few notches when things are looking steady again. Here is where the leaders have to maintain their vigilance and determination. Often the optimal situation for a worker is stability, while many leaders grow accustom to view change as a part of business life (Nadler, 1998).

One concept closely related to discontinuous change or even a part of it is something the literature describes as a ‘divergent breakpoint’. This is an event of innovation or a new business idea that affects all actors within an industry (Strebel, 1996). A good example is the opportunities that have emerged after the development of the Internet. Many organizations have due to this innovation been forced to make major adjustments throughout the organization to be able to stay competitive. However, it is important to realize that not all types of discontinous change are a result of technological innovations, but to all environmental turbulence (Senior, 2001). For change to qualify as a breakpoint it has to be sudden, radical and fundamental in its nature. Also it should cause a significant change in the performance trend and break the rules of the game making previous experience inadequate.

Radical change is yet another term in the same line as frame-breaking change, used to

however is close to the same. Radical change is said to begin with the complete breakdown of systems followed by a period of complete confusion and finally a rebuilding process with new core values, production systems and structures. To make a process like this successful it is important that the management team is able to provide an optimistic vision for the future. It is part of strategic thinking. Lacking a clear motivating vision it is likely that the organization will fail to achieve a full-blown reshaping process and instead follow old paths resulting only in some incremental adjustments (Newman & Nollen, 1998).

2.3.4 Generating new ideas

After conducting interviews with a number of executives in companies faced with unexpected competition caused by the Internet, Duyster, Nagel and Vasudevan (2004) formed a number of rules for how a company can generate new ideas and think in new terms how to change the rules of the game. Yet quite simple, the authors claim if implemented they can have a huge effect on the progress in the company’s reshaping process. We have touched upon these paragraphs previously but here they are stated clearly in four sections. The guidelines/rules are:

♦

‘Seeing things differently’. It is essential to constantly re-evaluate your vision andyour business model and to modify them for the future. It is important to question the relevance of current goals and views within the organization and try to generate insights from all personnel and create a climate that encourages thinking in new perspectives (Duyster et al., 2004).

♥

‘Doing things differently’. While the first rule may be the first step out of a difficultsituation, it is useless without action. According to the study by Duyster et al. (2004) many companies realize the need for change but they have big trouble to actually accomplish it.

♣

‘Establishing culture of experimenting and learning’. Many organizations are embeddedin orthodoxies that dictate what they should do, as opposed to what they want to do or what they can do. Sharing knowledge through effective internal communication is essential for an organization that wants to embrace change and create the future. Encouraging “out of the box” thinking must be accompanied with a tolerance for errors, since unique insights to problems may just as well be found in other disciplines (Duyster et al., 2004).

♠

‘Developing a portfolio of options in future markets’. When engaging on escapades trying to change the rules of the game, it is important to have a safety net, to be able to respond to unexpected events. Today’s discontinous environment is forcing companies to constantly be in the front of technological innovations. Otherwise they will most certainly lose ground. However, it is impossible to be at the cutting edge of all areas of innovation. The challenge companies are facing is therefore to develop their own core competences while at the same time have access to the competence of competitors. It has become common within many industries to form strategic alliances (Duyster et al, 2004).Creating an internal capability to change the rules will enable the company to exploit opportunities faster than its competitors. Fulmer (2000) mentions the company Seiko as a good example. The key element to Seiko’s early success was that they created two identical divisions with separate research, design and production facilities. As a result they competed with each other in being as productive as possible selling to the parent.

2.3.5 Response failures

According to Want (1995) most companies/managers who fail to respond to change often merely reaches for the easiest fix or pre-determined solution. Benchmarking, Total Quality Management (TQM) and decentralisation are all examples of “easy” ways out. The problem is that these actions do not really change the foundation of the corporation, something that occasionally is absolutely necessary. Fulmer (2000) says that implementing these development programs does not necessarily have to be bad, but they lack the understanding that all problems are interrelated with other problems. Hence, managers who tend to see specific problems in isolation instead of stepping back and take a look at the bigger picture are likely to fail.

Want (1995) gives a few reasons for failure that frequently can be seen. Managers often devote too much time to operational and financial issues instead of focusing on strategy. When looking for improvements they are also too much attached to the latest internal fix, while the best solutions are probably found beyond the company. New ideas and innovations can not be limited to the own organization. There are probably several reasons to this tendency. Fulmer (2000) says fear is definitely one of them, referring to studies that have shown that even though managers realize the seriousness and potential threat of a situation, they are reluctant to take action. Instead of seeing potential gains, they tend to focus too much on the risk involved. Donald Valentine, a successful CEO and founder in Silicon Valley explains why this situation is all too common:

“Every company eventually accumulates legacy customers and applications. They are run by silver-haired

guys who are very protective of the past. They are historically oriented. They just do not believe in the abandonment of the past. For a bunch of reasons, they are locked into it. Most recognize what’s going on. They just can’t decide what to do about it. Remember how late it was when Microsoft discovered the internet? 1995. They must have been on a trip to march” (Fulmer, 2000)

In many companies, pressure from interest groups such as boards and shareholders, force quick results which results in short-term goals. Though this is necessary in order to make everyone work together, it is even more important to have a clear view on what the long-term goal is. If employees are kept in the dark the organizational operations and culture will be crippled (Want, 1995).

When companies loose track of their customers during the change process, they have got big problems. There are many examples of business leaders who have blamed failure on all sort of external fixed factors, such as legislation. Meanwhile, they forget what is most important in order to run a successful business; to satisfy customer needs. Research has shown that companies that intensely stay in contact with what the customer wants are generally more successful than companies who see the customers only as a source of income (Want, 1995).

3

A reflexive case study approach

In this section we will present our method of choice, the reflexive methodology, and describe how we aim to adapt to our own qualitative research study. Despite not quite fulfilling the criteria for a case study we are going to use some of its more important elements, in order to clarify our way of working for the reader.

The two basic approaches to research can be classified in qualitative and quantitative studies (Nyberg, 2000). Whereas the quantitative study is primarily used for interpreting numbers and quantities, the qualitative research is used to receive in depth knowledge and understand phenomenon from data of less quantitative character. Lundahl and Skärvad (1999) further argue that the qualitative research method is used to understand the respondents’ view and perspectives, which is not necessarily an objective truth. Stake (1995) states that the essence of the qualitative research is the emphasis on interpretation and he points out the importance of reflection and patience in order to avoid misinterpretations in smaller collections of data.

In our case the music industry has witnessed a downfall in sales with around 33 percentage between the years 2001-2004 (IFPI, 2004) and we do not believe that we will be able to derive a single truth that can account for this, but rather to interpret our respondents’ reflections and thoughts to get an understanding of the phenomenon of downloading music over Internet and how they choose to work with/against it. This more interpreting way of analyzing our empirical findings, where we do not expect to find a single and objective truth, leads us into a hermeneutic philosophy within the qualitative research method. As was already mentioned in the introduction to the theoretical chapter; when we consider our theoretical framework and the somewhat unique position that the recording industry is in today, we believe that some of the theories only will be partly applicable. We will further discuss this in our analytical reflections, but it would hint that our research is more depending on the actual empirical findings. Hence we would be adapting more of a data-oriented method. The mixture of these philosophies goes hand in hand with what Alvesson and Sköldberg defines as the reflexive methodology.

3.1 Reflexive methodology

Data-oriented methods, hermeneutics, critical theory and postmodernist views are all examples of philosophies of science. To put it simply they represent different schools of collecting and interpreting data. We will hereby give very brief descriptions of each one of these approaches and, in line with Alvesson and Sköldberg (2000), argue for the combination of these four schools – the reflexive methodology.

3.1.1 Data-oriented methods

Data-oriented methods focus almost purely on the empirical findings and the usage of techniques to process data. Grounded theory, the biggest school within the data-oriented family, addresses the analytical operations and aspects of the qualitative research (Locke, 2001). By systematics and research procedure techniques, and by taking a somewhat natural distance from theoretical aspects, supporters of data-oriented schools can be seen as empiricists (Alvesson & Sköldberg, 2000).

3.1.2 Hermeneutics

“Philosophical hermeneutics opposes a naïve realism or objectivism with respect to meaning and can be said

to endorse the conclusion that there is never a finally correct interpretation.” (p.195, Denzin & Lincoln,

2000)

This goes in line with how Grix (2004) describes it, as an analysis from the perspective of the person who is doing the actual research. Hermeneutics is a challenge to the claim that an interpretation can be absolutely correct or true, since the answer is always based from the perspective of the eye of the beholder (Patton, 2002). In other words, the result is only one interpretation rather than a definite answer and the focus on the interpretation makes hermeneutics an important part of reflection (Alvesson and Sköldberg, 2000).

3.1.3 Critical view

The critical view is based on the point of view that social science never can be completely neutral or objective in relation to a social study. Personal interests influence any study in a positive or negative way, regardless of the researcher’s awareness or not. Politics and money are two of the more obvious underlying reasons to subjectivity in social studies. Critical theory can be described as a deeper kind of hermeneutics, where weight is put on reflections on the unconscious level, ideologies and power relations in order to analyze findings that at first glance seem objective. The theoretical framework is of high importance to draw the guidelines for the interpretation, but it is just as important to see beyond the empirical findings to analyze the respondents’ conception of the world and to see his/her part of the totality (Morrow, 1994).

3.1.4 Poststructuralism and postmodernism

Researchers argue whether or not poststructuralism and postmodernism share its origins and key concepts, and since this is not to greater importance for our study we will not go into any further details of their differences. A common key concept within them both is

deconstruction; old truths are no longer seen as truths and the postmodernists strive to

question the underlying presumptions and authorities to existing theories and systematic models. Postmodernists/poststructuralists try to minimize the external aspects of a text, taking a kind of perspective that its given contextual truths are in fact not true in order to view the text purely isolated (Alvesson, 2002).

3.1.5 Our reflexive methodology

All four schools above and their different levels of performing a qualitative study have contributed to what Alvesson and Sköldberg (2000) call the reflexive interpretation. It can be described as a method of interpreting and relating to data where the essence lies in a mix of the different levels and where the main point lies in the reflection and interpretation rather than looking at something from a static structure, as in the cases above. One or more levels of interpretation can be dominating, but the most important part of the reflexive interpretation is the actual interaction between levels.

As previously argued our own focus will be something of a mix of two levels; the data-oriented method and hermeneutics. This will be the base for our analytical work and can be resembled in our reflections further ahead. Alvesson and Sköldberg (2000) argue that reflections in the shape of notes or additional sections can be inserted to critically relate to empirical findings and its interpretations. We have inserted reflections both after our empirical section and the analysis. By critically reflecting over themes such as power,

politics or ideology the main point with the reflexive methodology is to generate an interest by innovative interpretations and results. Original questions asked and/or creatively structured observations can be of big help in the interest creation process (Alvesson and Sköldberg, 2000).

Four of the elements, one collected from each of the four schools, provide the framework for reflective research (p.7, Alvesson and Sköldberg, 2000):

1 Systematics and techniques in research procedures 2 Clarification of the primacy of interpretation

3 Awareness of the political-ideological character of research

4 Reflection in relation to the problem of representation and authority

Bearing these four points in mind we will critically review and reflect over our empirical findings and analysis in order to try to fulfil the criteria of adapting a reflexive methodology. These reflections can be found at the end of chapter four and five.

3.2 The case study approach to the downloading

phenomenon

The case study is one of many different approaches to research strategy just as experiment, history and survey strategies are, and the boundaries between these strategies are not always sharp (Yin, 1994). In other words, clearly defining the origins of a study is sometimes difficult since the approaches overlap each other. In our own study we simply state that our approach is highly influenced by important elements of the case study approach, rather than arguing whether or not our research fulfils the criteria and depth of a case study. We will later go more into our interviews and the choices we have made that stand out somewhat from a traditional case study.

The case study can be performed either as a single-case or as a multiple-case study. They both have their strengths and weaknesses and where the single-case study is more appropriate to use when going deeper into a special case the, multiple-case study is often argued to be more robust and able to provide more compelling evidence (Yin, 2003). For this reason, he further states, that when having the choice between the two the multiple-case study is preferred, even though it is usually more demanding in terms of time and resources (Yin, 2003). Stake (1995) argues that multiple case studies sometimes are required in order to understand certain phenomenon that a single case can not explain. Since we have the possibility to choose how many respondents we will take into consideration, and in order to deepen our understanding for as many aspects of the on-going change as possible in the music industry, we will perform something similar to a multiple case study, although not quite as deep.

Face to face interviews will be combined with additional secondary data retrieved from the Internet and newspapers. Our primary data will be collected during interviews with EMI Sweden, Sony BMG and Universal Music, three of the biggest record companies in Sweden. The usage of multiple sources is argued by Yin (1994) to be of high importance to the validity and reliability of the research.

The environment and the respondents should be chosen for their ability to contribute in the context of the study (Ryen, 2004). This is primarily done by choosing an area of study and then simply searching the most appropriate environment for the study. Another

important factor to take into consideration is the variety of the selection. To cover a broader spectra of the research area the respondents should be of a selection that covers the heterogeneity within the homogeneity of the targeted population (Ryen, 2004). In our case, focusing on the ongoing change in the recording industry, we chose to approach a number of large record companies which we presume have the resources to work with and the ability to relate to our downloading related questions in the best way possible. We decided further that in order to get an understanding for the phenomenon we did a selection of our respondents based upon their respective jobs. Our conditions was that they have to be a part of the management group and well familiar with the strategic planning of the organization, while at the same time have a good insight in the work with downloading issues. The following respondents accepted to take part in our study:

• EMI Music: Mattias Wallin, Sales Manager and Klas Lunding, A&R manager 1 • Universal Music: Jens Eriksson, New Media Manager

• Sony BMG – Carl Ekdahl, Digital Business Director

In the end, and in accordance to what Grix (2004) states about the qualitative research method, we have focused on our interpreting role to analyze data that has been flexibly collected, referring to the open way of gathering data. This way of data collection will be further described in the semi-structured interview.

3.3 Semi-structured

interview

First of all, the questions we are going to ask are mostly of how and why character, once again an important element from a typical case study (Yin, 1994). The questions can be found in appendix 1. In accordance to how Ryen (2004) describes the semi-structured interview we will have a frame of main questions and a comprehensive theme, but with a number of openings for more detailed and spontaneous questions as the interviews advance. Asking open-ended questions where the respondents will answer in both terms of facts as well as own personal reflections, is the essence of the semi-structured interview (Yin, 2003). We will take advantage of adapting this kind of loose structure in order to follow up ideas and ask deeper questions in order to increase our understanding (Arksey and Knight, 1999)

Using a recording device we hope to minimize potential data loss and in accordance to Arksey and Knight (1999) we will be able to focus on the actual conversation rather than writing down everything that is being said. We will, however, take notes during the interview, which is argued to be an important way to grasp immediate reflections. Ryen (2004) further states that notes are even the first step of the analytical work.

Some of our questions might be of sensitive character due to their strategic nature, but since we outspokenly state that our intention is not to make a comparison between the companies we hope that our respondents will open up during our interviews. We will further ask for permission to come back to the respondents with any additional questions through e-mailing, which is argued by Ryen (2003) to have some obvious advantages of convenience and time for reflection. They will also be given time to read and correct any data from the interviews that they disagree with or want to leave out, due to its sensitive nature.

1 During our interview with Mattias Wallin at EMI Music, we were suggested to further discuss our topic

4 Empirical

data

In this chapter we will introduce our respondents and the record companies they work for and present our empirical findings categorized in five main themes. The categorization was done in order to structure our empirical findings in relation to our questions.

All data in this chapter is based on the interviews that we performed with representatives from the three record companies. Throughout this text we will introduce our respondents under each subchapter. References in the text are used when necessary, where it is unclear who said what. In the rest of the text, given the fact that it will be stated in each company introduction when the interviews took place, we only refer to their names.

4.1 EMI

Sweden

Introduction to the company

EMI Sweden is regarded to be one of the most influential companies within the recording industry, now containing several strong labels that were previously on their own, including Virgin Music. As most companies in the recording industry, they have recently witnessed a severe decline in sales and has conducted major cuts in personnel, leaving only 40 in Sweden. During our visit at EMI, we met with two of the directors within the management group in Sweden.

Mattias Wallin is the sales director since the fall of 2002 and is currently also temporarily handling the tasks of the marketing director. He has a background in the area of sales from several major companies and has recently been working 6 years as sales director for an organization active within satellite communication. As sales director at EMI it is his first time working with what he calls “fast-moving” products such as records, downloading and ring tones (M. Wallin, personal communication, 2005-04-14).

Klas Lunding has on the other hand a long history within the recording industry. He founded his first record company at the age of only 17 and was also one of the forces behind Dolores Recordings, a well-reputated company that is now a part of the EMI concern. Currently he works as the A&R Director within EMI. In other words he is responsible for artists and repertoires (K. Lunding, personal communication, 2005-04-14). The interviews with Wallin and Lunding were conducted separately.

Views on the downloading phenomenon

Wallin and Lunding are of the same opinion saying that downloading is definitely here to stay. It is not something that they are trying to reject or defeat. In fact it is quite the opposite as they are trying to take advantage of this new situation they are facing. Commenting on the phenomena of downloading, Wallin says they try to see the positive sides and to evaluate the possibilities that after all exist in this new medium.

For instance, Lunding mentions that the possibility to distribute music in a more efficient and quick manor, surely is one of the big incentives to focus more on the possibilities that Internet does bring. He says that Internet as a tool has become a constant necessity in most businesses and that the recording industry should in fact be happy that they do have a virtual product that can be sold digitally now and in the future.

Personally, Wallin believes downloading is one of the minor contributors to the declination of sales, but agrees on the notion that Internet has made a certain behaviour possible