Disruptive

Innovation in Green

Energy Sectors: An

Entrepreneurial

Perspective

BACHELOR DEGREE PROJECT THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: International Management AUTHOR: Kjel Hendriks

JÖNKÖPING June, 2021 WORD COUNT: 17,965

A bachelor thesis that aims to analyse the

macro-environmental,

industrial

and

cross-collaborative

environment for green entrepreneurs

Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Disruptive Innovation in Green Energy Sectors: An Entrepreneurial Perspective Authors: Kjel Hendriks

Tutor: Dr. Quang David Evansluong Date: 2021-05-24

Key terms: green entrepreneurship, disruptive innovation, innovation impact, cross-collaboration, green hydrogen energy systems

Abstract

Background: Green hydrogen energy systems can address environmental and societal

concerns within the energy sector. Therefore, increased attentions from both public and private stakeholders has led to the general perception that hydrogen systems can serve as a disruptive innovation. Given that disruption innovation theory has seen increased entrepreneurial involvement over recent years, the study focuses on assessing the role of green entrepreneurs within the implementation of hydrogen systems through cross-collaborative efforts and disruptive innovation drivers.

Purpose: The development of a theoretical matrix that interconnects disruptive innovation,

entrepreneurial involvement, and cross-collaborative initiatives to establish entrepreneurial positioning roles within the energy market.

Method: The epistemology chosen was interpretivist, and its ontology subjectivism. The

research followed an inductive approach. The research was qualitatively conducted and adopted a case study approach. The data was collected through semi-structured interviews, and followed a theoretical sampling approach.

Conclusion: The study proposes a theoretical matrix that extended disruptive innovation

theory to green entrepreneurship and concluded that high levels of cross-collaboration, and a high innovation impact, serve as key drivers for green entrepreneurial implementations of disruptive energy. Results highlight the need for entrepreneurial involvement across all stages of market implementations.

———————

Kjel Hendriks

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, I want to thank Dr. Quang David Evansluong for his continuous support and feedback throughout the research process. I would not have been able to develop this thesis without your help.

Furthermore, I want to express my deepest gratitude to each participant within this research. You have helped me immensely in understanding innovative and entrepreneurial impacts within the field of hydrogen. Thank you for your cooperation and time.

I have too many members in my personal network to thank, but special acknowledgements go out to my father Marc, my mother Sanna, and my sister Mur for always supporting my academic and personal decisions. I am proud to call you my family.

Lastly, I want to thank Sven Knauer and Molly Lillian Monaghan for their structural feedback and continuous dedication to my academic and personal life. I could not have asked for better people to surround myself with.

Table of Contents

Introduction ... 5

1.1Problem ... 6 1.2Purpose ... 8 1.3Research Question ... 9Terminology ... 10

2.1 Disruptive Innovation ...10 2.2 Green Entrepreneurship ...10 2.3 Macro-environmental drivers ...11 2.4 Industry drivers ...11 2.5 Green Hydrogen ...11Frame of Reference ... 12

3.1 Method for the Frame of Reference ...13

3.2 Disruptive Innovation in the Energy Sector ...14

3.3 Green Entrepreneurship ...17

3.4 Macro-environmental and industry drivers ...19

3.5 Hydrogen Entrepreneurship ...21

3.6 Gaps in the Knowledge ...23

Methodology ... 26

4.1 Research Philosophy ...26 4.2 Research Approach ...27 4.3 Research Strategy ...27 4.4 Research Design ...28Method ... 30

5.1 Data Collection ...30 5.2 Data Analysis ...34 5.3 Ethical Considerations ...36Results ... 37

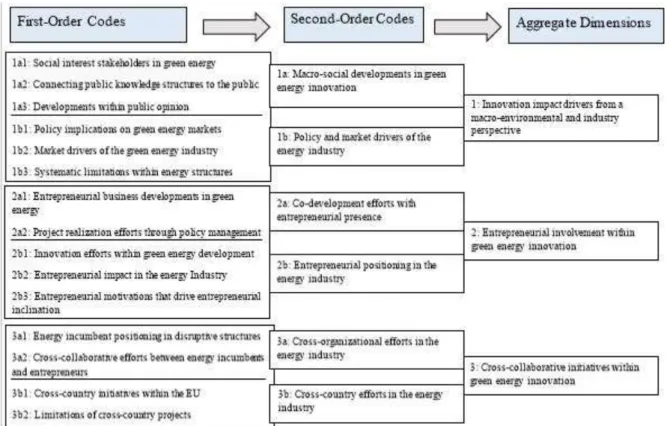

6.1 Innovation impact drivers from a macro-environmental and industry perspective ...38

6.1.1 Macro-social development in green Energy Innovation ...38

6.1.2 Policy and market drivers of the energy industry ...40

6.2 Entrepreneurial involvement within green energy innovation ...42

6.2.1 Co-development efforts with entrepreneurial presence ...43

6.2.2 Entrepreneurial positioning in the energy industry...44

6.3 Cross-Collaborative initiatives within green energy innovation ...45

6.3.1 Cross-organizational efforts in the energy sector ...46

6.3.2 Cross-Country efforts in the energy sector ...47

Discussion ... 49

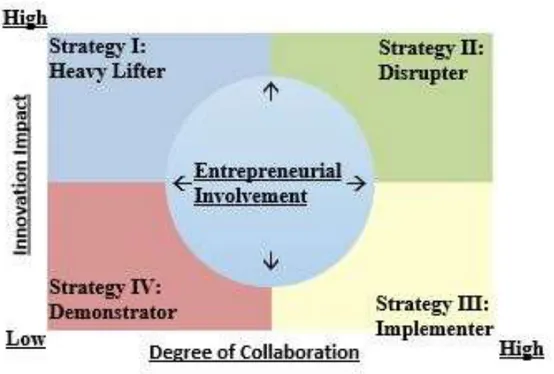

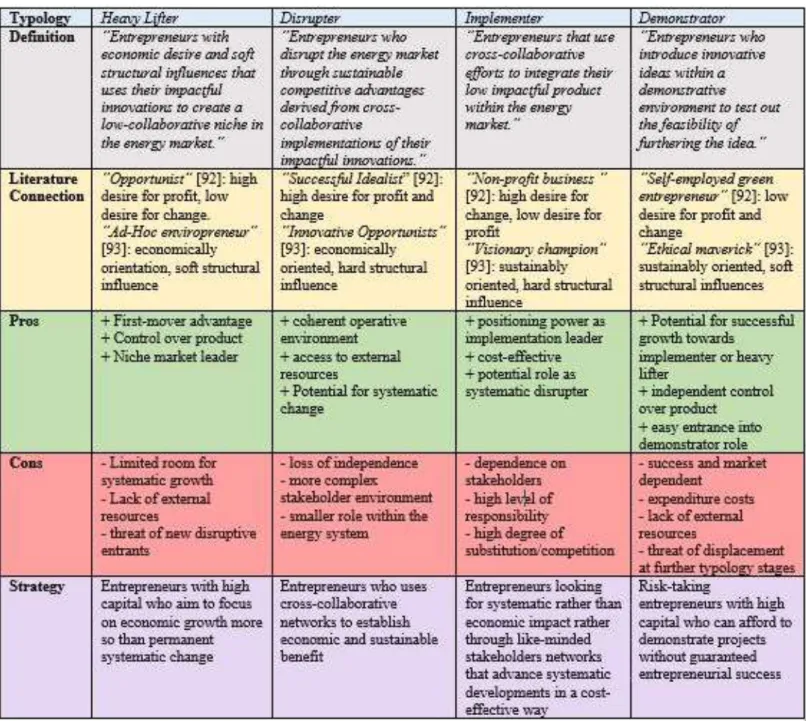

7.1 The Innovation-Collaboration Entrepreneurial Positioning Matrix ...49

7.2 The level of innovation impact dimension ...51

7.3 The level of entrepreneurial involvement dimension ...52

7.4 The degree of collaboration dimension ...53

Strategy I: The Heavy Lifter ...54

Strategy III: The Implementer ...55

Strategy IV: The Disrupter ...55

Conclusion ... 58

8.1 Theoretical Contributions ...59

8.2 Practical Applications ...60

8.3 Strengths and Limitations ...61

8.4 Areas for Future Research ...61

Reference list ... 63

Figures

Figure 1………...37 Figure 2... 50Tables

Table 1……….18 Table 2……… 31 Table 3……….32 Table 4……….57Appendix

Appendix 1………...76Introduction

_____________________________________________________________________________________

This chapter introduces the research topic by establishing the problem area in terms of green energy, disruptive innovation and green entrepreneurship. Then research need is assessed by evaluating the current state of knowledge and reasons for improvement. This proposes the scope of the research that the research questions aim to explore.

______________________________________________________________________ Global fossil fuel consumptions have created a natural imbalance, and propelled an environmental crisis. Current rates of fossil fuel consumption threaten global stability in world population growth, technological development, and energy demand (Midilli and Dincer, 2007). While the 1993 Kyoto protocol established goals to mitigate human-made emissions (Grubb, 2004), multiple stakeholders are still seeking solutions that can complement these goals. One solution, renewable energy (RE), can address rising energy demands, and environmental and energy security concerns (Haar and Theyel, 2006). Corporations promoting RE implementation would encourage the realization of disruptive innovations - nascent products, inferior to established products, that offer a novel mix of attributes that appeal to certain customers (Christensen et al., 2018). Disruptive innovations could offer untapped opportunities for various stakeholders that address environmental and social concerns (Havlíček et al., 2012; Marques & Fuinhas, 2011; Bagheri Moghaddam et al., 2011).

Entrepreneurs play a leading role in introducing disruptive innovations in sustainable energy technology supply chains (Reddy, 2015). Green entrepreneurs, sustainably-motivated entrepreneurs that utilize innovative business models and cost-competitive technologies to establish a green economy, are becoming crucial as disruptive innovators, or spreaders of RE technologies (Haldar, 2019; Pinkse & Groot, 2015; Reddy, 2015).

Positive correlations between entrepreneurial innovations and cross-organizational collaborations have led to a rising importance of network-building (Anderson & Li, 2014; Heidemann-Lassen et al., 2008). The success of collaborative efforts stems from public-private initiatives, or entrepreneurial networking (Renewable Hydrogen Coalition, 2021; Zhou et al., 2021; Anderson & Li, 2014; Heidemann-Lassen et al., 2008). The European Union (EU) has inspired organizational interconnectedness through funding and regulatory policies (European Commission, 2019; European Commission, 2020b; European Commission, 2020c; House of Lords, 2002).

Several disruptive innovations aim to substitute conventional energy sources for low-carbon alternatives in the current socio-economic system (Jäger-Waldau, 2007). These innovations, much like entrepreneurs, are influenced by the ability to change political institutions (Tyfield,

2018). Sustainability-oriented policies develop transitionary pathways for RE innovation, but uncertainties and general short-sightedness of energy policies remains (van Rooijen & van Wees, 2006). Various policies promote disruptive innovations, but inconsistent policy structures hinder the discovery, and utilization of systematic macro-environmental and industry factors.

Hydrogen energy, the conversion of hydrogen to electricity, presents leading energy innovation opportunities. Particularly, green hydrogen can use diverse RE inputs, is reaching cost-competitiveness, and can serve as an energy substitute to meet set goals for energy supply, security, and sustainability (Midilli and Dincer, 2007; Hydrogen Council, 2020; IEA, 2019). Current hydrogen innovations is limited to non-renewable versions, whereas demonstration projects are assessing feasibility regarding storage, technology, and power-to-gas plants (Menachem, 2018; Quarton & Samsatli, 2018; Parra et al., 2017; Leonzio, 2017).

Green hydrogen’s immaturity offers entrepreneurs opportunities to implement disruptive innovations. Therefore green hydrogen will be used as a research area to explore entrepreneurial disruptive innovations. Global RE trends can boost employment in various public and private sectors (Havlíček et al., 2012). Yet green hydrogen’s newness carries undefined institutional drivers that influence disruptive innovations. Ambiguous drivers pose threats to disruptive innovation growth for green energy entrepreneurs. Consequently, further research on cross-collaborative and external influences is important.

1.1 Problem

RE develops slow and lacks financial competitiveness (Dinica, 2006; Menanteau et al., 2003). RE implementation is generally hindered by a misguided understanding of collective cross-collaborative drivers of the industry, consequently creating ambiguous policies and confusion among entrepreneurs.

Currently, entrepreneurial activities concerning green disruptive innovations are techno-centric and market-oriented rather than strategic (Pinkse & Groot, 2015; Schuelke-Leech, 2021; Nagy et al., 2016). Transport is popular amongst hydrogen entrepreneurs, whereas the systematic implications of green disruptive innovations are overlooked (Energy Transition Institute, 2020; Atanasiu, 2019).

Entrepreneurial inclination is influenced by drivers different than collective and systematic goals (Martin et al., 2020; Eitan et al., 2020). This poses a risk for entrepreneurial development within green energy. Existing studies focus on specific countries, overlooking cross-country involvement (European Commission, 2017). Similarly, studies solely research political,

economic, or logistical challenges posed against hydrogen innovations and fail to address driver interconnectedness (Hydrogen Council, 2020;Menachem, 2018; IRENA, 2020; IEA, 2020a). Other studies only consider driver influence in the short-run and fail to address long-run political and economic implications (Damette & Marques, 2018).

The systematic potential of hydrogen is understood (Midilli and Dincer, 2007), but current efforts are inhibited by immature infrastructures limited research and development (R&D) - the tools that secure the value of hydrogen as a systematic concept (Menachem, 2018; Andrews & Shabani, 2014).

Current knowledge on the drivers of collective and cross-collaborative sustainable energy markets requires more research, so that public and private stakeholders can facilitate disruptive innovations within energy sectors. Current RE policies are uncertain, short-sighted, and fail to address the distinguishable characteristics of different RE sources (van Rooijen & van Wees, 2006; Johnstone et al., 2008). The macro-environmental ambiguity in a nascent research field has thus limited entrepreneurial success. Green hydrogen is young and requires a deep understanding of dynamic factors that influence developments in emerging technologies (van Merkerk & van Lente, 2005).

Additionally, vagueness surrounds those who should develop disruptive innovations, the ‘green entrepreneur.’ Diverse green entrepreneurial definitions have barred the group from distinguishing themselves as a separate group of entrepreneurs (Haldar, 2019; Eitan et al., 2020). Consequently, the development of unique strategies, conditions and entrepreneurial drivers has stalled. Currently, entrepreneurial inclinations face several market and political barriers, while entrepreneurs are also influenced by individual motivations (Bhat & Khan, 2014; Meijer et al., 2007; Pinkse & Groot, 2015). Entrepreneurial inclinations are thus less attractive due to uncertainties (Meijer et al., 2007).

To address this research gap, different stakeholders should collectively establish disruptive innovation drivers that green entrepreneurs may exploit through cross-organizational efforts. These drivers are either macro-environmental, industry-oriented, or personal (Bhat & Khan, 2014; Meijer et al., 2007).

To address the barriers to these types of drivers, a theoretical framework highlighting cross-collaborative inclinations and innovative influences should be developed. This would offer future stakeholders the clarity to implement disruptive innovations in a changing industry. In turn, green entrepreneurial inclinations, disruptive energy innovations, and green energy market conditions would be further assessed, and may answer some questions not addressed in the current literature.

1.2 Purpose

There is growing ambiguity and uncertainty among green entrepreneurs and disruptive innovators. (Marques & Fuinhas, 2011; Haldar, 2019; van Rooijen & van Wees, 2006; Eitan et al., 2020;Johnstone et al., 2008; Meijer et al., 2007). Creating a set of drivers that assesses green energy markets may allow new entrants to avoid obstacles that prevent sustainable innovation development. The research purpose is to further understand disruptive innovation theory and energy entrepreneurship from a market perspective to determine the current competitive landscape for disruptive innovations in energy markets, the current set of drivers influencing disruptive innovations, and the cross-collaborative role within the facilitation of disruptive innovations through green entrepreneurship.

The EU has put forth regulatory and economic instruments that address the current and future energy sector for RE innovators (European Commission, 2019). To analyse interconnected institutional effects on disruptive innovations, entrepreneurial inclinations and cross-collaborative efforts, the EU was chosen as the scope for the research. A framework that captures the effect of drivers and cross-collaborative efforts on entrepreneurial innovation will offer disruptive innovators a stronger chance to penetrate the energy sector. While this research would mainly benefit entrepreneurial innovation within the energy market, the research was carried out as to potentially benefit other markets.

The current state of knowledge on disruptive innovation entrepreneurship highlights the necessity of establishing factors that influence the implementation of cross-collaborative efforts for disruptive innovations. With hydrogen as a disruptive innovation in mind, two research questions were developed. The first question determines the most influential market drivers that facilitate cross-collaborative efforts for disruptive innovations. The second question connects the findings of the first question to strategic entrepreneurship. By doing so, the author assesses the drivers that influence the market positioning of public, private, and start-up organizations within current energy disrstart-uptions, and then analyses the effect of cross-collaborative strategies on future entrepreneurial success within the chosen area, hydrogen. A framework shall be developed to analyse entrepreneurial impacts through its involvement with both disruptive innovations (RQ1) and cross-collaborative strategies (RQ2).

1.3 Research Question

RQ1: What macro-environmental and industry drivers influence the cross-collaborative facilitation of disruptive innovation within energy sectors?

RQ2: How do cross-collaborative strategies influence green entrepreneurial success within hydrogen systems?

Terminology

_____________________________________________________________________________________

This chapter provides the reader with key terms required to grasp the scope of the research. The definitions are first introduced with established literature, before the author develops own definitions deemed appropriate for the research at hand.

______________________________________________________________________

2.1 Disruptive Innovation

Disruptive innovations are described as new products or services, inferior to established goods on accepted performance dimensions that appease to performance dimensions of niche customers (Christensen et al., 2018; Yu & Hang, 2010; Christensen, 1997; Christensen & Raynor, 2003; Christensen et al., 2004). Disruptive innovation theory is considered a process-based theory, where the new inferior good transitions from exclusively satisfying niche markets to satisfying both niche and accepted markets enough to disrupt the business operations of conventional goods (Schmidt & Druehl, 2008). In the scope of this thesis, disruptive innovation is defined as nascent goods that currently appease to niche energy markets, yet have significant potential to satisfy the accepted performance dimensions that allow it to disrupt the conventional energy market.

2.2 Green Entrepreneurship

Green entrepreneurship pertains to both sustainable development and entrepreneurship. Sustainable development was first defined as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (WCED, 1987)”. However, global ‘needs’ are hard to define, due to institutional differences worldwide

(Redclift, 2005; Sneddon et al., 2006). Consequently, three hundred definitions of ‘sustainable development’ have originated since its original definition (Santillo et al., 2007). For consistency within the research, the author chose the definition of the WCED as the guiding narrative for sustainable development.

Sustainable entrepreneurs replace conventional production methods, products, market structures and consumption patterns with superior environmental and social alternatives (Schaltegger & Wagner, 2011). In other words, sustainable entrepreneurs bring disruptive innovation to conventional sectors by promoting environmental and social consciousness. Gast et al., define ecological sustainable entrepreneurship as “the process of identifying, evaluating

and seizing entrepreneurial opportunities that minimize a venture’s impact on the natural environment and therefore create benefits for society” (2017).

To connect sustainable development to green entrepreneurship, the author has defined ‘green entrepreneurship’ as business activities that introduce disruptive innovation processes to replace conventional market structures, production methods and consumptions patterns, and seize entrepreneurial opportunities that meet the needs of current generations while creating benefits for future societies.

2.3 Macro-environmental drivers

The macro-environmental drivers were inspired by the political, economic, socio-cultural, technological, ecological, and legal influences from the PESTEL model (Zentner et al., 2020). Logically, macro-environmental drivers, in the scope of this thesis, are defined as political, economic, socio-cultural, technological, ecological and legal influences that pose as an opportunity, risk, or challenge for the facilitation of disruptive innovations within the energy sector.

2.4 Industry drivers

The industry drivers for this thesis were inspired by the market competitiveness forces - suppliers, buyers, substitutes, potential entrants, and industry rivals – from Porter’s Five Forces theory (Gartner & Porter, 1985). By linking industry drivers with an economic theory, they can be defined, within the scope of this thesis, as industry factors that influence the market competitiveness and attractiveness of disruptive green entrepreneurial positioning within the energy sector.

2.5 Green Hydrogen

Green hydrogen is the production of energy through the input of RE sources (Clark & Rifkin, 2006). Green energy sources offer opportunities for electricity to be produced, distributed, and used in the energy supply chain. Green hydrogen can serve as flexible “open energy systems” that address key energy and environmental concerns (European Commission, 2003). Within the scope of the research, green hydrogen is defined as open energy systems that produce, distribute and serve as electricity utilizations through the input of renewable energy sources.

Frame of Reference

_____________________________________________________________________________________

This chapter provides the theoretical background to the research. First the method of retrieving peer-reviewed literature is described. Secondly, four themes for further analysis are created and each is related to the research purpose through a critical analysis of the established literature by highlighting the current state of knowledge and consequent gaps. The last section summarizes the gaps in knowledge that the research purpose aims to address.

_______________________________________________________________________ The research aims to further the understanding of disruptive innovation and entrepreneurial theories to assess the market environment and industry competitiveness of disruptive green entrepreneurs within the energy sector. To further analyse the research aim, a frame of reference examined separate themes in relation to the research purpose. First, the methodical approach to acquire literature, and developed key themes related to the research were explained, followed by further research into four major themes to establish literary understandings in each field.

“Disruptive innovation in the energy sector” analysed the current state and gaps of green disruptive innovations within energy. This established current disruptive innovation developments, along with key elements that have seen limited research. Green entrepreneurship is introduced afterwards to connect entrepreneurship with green disruptive innovations, to develop characteristics that influence green entrepreneurial roles, and to highlight current issues in green entrepreneurial literature and its effect on disruptive innovation developments. After the disruptive innovation and green entrepreneurship knowledge was established, a section on macro-environmental and industry drivers followed. This section refined the current set of drivers that influence disruptive innovation and entrepreneurial activity within the energy sector. Additionally, the section highlights cross-collaborative roles and exposes current gaps in the knowledge on drivers to establish research prioritizations.

Lastly, “Hydrogen Entrepreneurship” introduced green hydrogen, and analysed existing efforts within entrepreneurial operations of green hydrogen. Furthermore, the drivers that specifically influence entrepreneurial inclinations and disruptive innovation success within green hydrogen were analysed.

A summary on the gaps in the knowledge concludes the chapter to highlight the need for further research on each respective theme and current influences of gaps on the derailment of strategic implementations of green disruptive innovations.

3.1 Method for the Frame of Reference

The research purpose requires a certain level of background knowledge through the initial search, analysis and gathering of data from secondary peer-reviewed literature. Peer-reviewed literature is essential to research studies, and provides high-quality and valid findings (National Library of Medicine, n.d.).

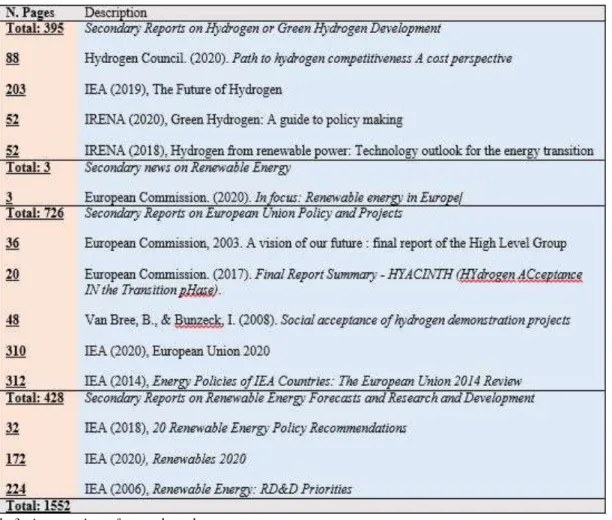

The frame of reference first developed in November 2020, when the author wrote a preliminary literature review on Hydrogen Business Models. The searches in this review were restricted to the following keywords: “Hydrogen Business Models”, “Net-zero Carbon Dioxide”, and “Public and Private sector.” Twelve relevant sources were then used within the literature review. Given the deviation from hydrogen business models to green hydrogen entrepreneurship, only seven documents remained valuable to this thesis, due to their relevance on hydrogen innovation, and the public-private influence of those innovations (Midilli and Dincer, 2007; Menachem, 2018; Van Bree & Bunzeck, 2008; Quarton & Samsatli, 2018; Aboumahboub et al., 2010; Parra et al., 2017; Leonzio, 2017). This first step, before concrete development of the current thesis purpose, established an initial understanding of hydrogen business models and green energy developments.

To synchronize the research purpose, documents on social, economic, and political implications on green energy were gathered from reputable energy organizations to further direct the research purpose towards identifying, and subsequently, defining drivers that influence a renewable energy economy (Hydrogen Council, 2020; IRENA, 2020; IEA, 2020a; IEA, 2006; IRENA, 2018; IEA, 2020b).

To connect RE innovation to driver influences, two further themes were sought after: RE innovation in green hydrogen, and disruptive innovation through entrepreneurship. This allowed the author to connect knowledge from disruptive innovation and entrepreneurship theories with empirical evidence on renewable drivers, and then develop a theoretical framework that considered and interconnected entrepreneurship and disruptive innovation with energy markets.

The author considered sustainable entrepreneurship as the field of research, and sought literature on innovation management, environmental entrepreneurship, and entrepreneurial innovation to limit the scope. This thus connected strategic management to disruptive innovation entrepreneurship. Relevant literature was gathered by utilizing keywords that related to the thesis scope. The search engines Primo and Google Scholar were used for their wide yield as search engines. Key words were used separately, and in combination, to ensure

all possible results were considered. The following keywords were used to find results: “Disruptive Innovation Energy”, “Disruptive Innovation Entrepreneur”, “Green Entrepreneur”, “Green Energy Drivers Macro”, “Green Energy Drivers Industry”, “Hydrogen Entrepreneurship OR Innovation” and “Renewable Energy”.

The keywords were related to the thesis purpose and aimed to establish recurring themes within the literature that the thesis could address. Selection criteria were created before further analysis. The literature had to abide with at least two out of the four criteria: i) the source’s focus described disruptive innovation within RE business, or green entrepreneurship, ii) the focus analysed drivers that facilitated RE entrepreneurship, iii) the focus centred around hydrogen entrepreneurship or hydrogen innovation, and iv) the source date was between 2000 and 2021. These four criteria aimed to justify the findings of the frame of reference by ensuring that the literature assessed green entrepreneurship, disruptive innovation or driver analyses through a business management lens. The literature also concerned contemporary energy developments, and either addressed or established a gap in the knowledge that further developed the need for the author’s research to continue.

The collected literature was refined to ensure a reliable impact on the study and relate to the research questions. Abstracts, keywords, discussions and conclusions were critically analysed. Eventually, nineteen articles connected the thesis purpose with the selected criteria. These articles provided multiple references to other peer-reviewed articles, of which the relevant were analysed and included in the frame of reference to add multiple, valuable perspectives. Due to their previous reputation among established researchers, the publication date of additional references was not considered. Four themes developed from the literary analysis: disruptive innovation, green entrepreneurship, market drivers and hydrogen developments. These themes were chosen as they related to the research purpose. The thematic analysis which follows compared and contrasted problems, gaps, and the current knowledge on RE, entrepreneurship, innovation, and cross-collaborative strategic management.

3.2 Disruptive Innovation in the Energy Sector

Disruptive innovation may cause upsets in the conventional practices within sectors in various

ways. While Christensen’s original theory referred to technological innovations that disrupt established companies (1997), recent literature acknowledged effect of disruptive innovations on business models and business operations (Markides, 2006). Within energy sectors, technological change, as well as model innovation, can play a role, where

business-model innovation is defined as the “discovery of a fundamentally different business business-model in an existing business” (Markides, 2006).

Within the energy sector, disruptive business models have strong connections to the implementation of technological disruptions. Technological changes put pressure on incumbents to adapt their business operations so that competition with new entrants becomes viable, which in turn has allowed decentralized customer-centric business models to stabilize (Johnstone & Kivimaa, 2018; Matschoss & Heiskanen, 2018). These models may disrupt the current business models tied to dominant energy regimes (Kivimaa et al., 2021). Simultaneously, disruptive business models can serve as disruptive innovations that alter customer dimensions, value perspectives, and societal participation, where incumbents find trouble adapting to new environments (Johnstone & Kivimaa, 2018; Martin, 2016; Wainstein & Bumpus, 2016).

Business models depend on the value they provide, and in order to pursue disruptive innovation, companies will need a distinguishable resource that is hard to imitate (Priem & Butler, 2001). Yet resource values, and therefore the degree of innovative success, is affected by both internal and external environments. Consequently, a company with a disruptive innovation should create a harmonious internal environment while simultaneously assessing and adapting to external environments such as market conditions (Priem & Butler, 2001; Miller, 1992). Within the energy sector, these conditions would be projected through entrepreneurial, societal and market activities.

One market condition that benefits disruptive innovations is the inability for an incumbent to adapt to fast changes within business innovation. As Christensen et al. elucidate, disruptive innovation segments pertain to “innovations that capture markets that previously did not exist” (2004). This nascent market is hard to capture by incumbents, as offering an equivalent innovation that challenges new entrants would likely result in the cannibalization of its original profitable offerings (Kumaraswamy et al., 2018). Contextually, incumbents that compete with disruptive entrepreneurial innovations would sacrifice current profits on established products to implement green energy alternatives.

Disruptive innovation in green energy is limited by policy frameworks and its homogeneous power market. Innovation is generally customer-based (Markides, 2012; Simanis & Hart, 2009), which is not strongly reflected in the energy market. Energy products are considered public goods that rely on policy support, with no room for natural markets (McDowall et al., 2013; McDowall, 2018). Green energy has been disrupted the market, but has done some by straying away from disruptive innovation practices as defined by theory (McDowall, 2018).

Generally, innovations within the energy market are policy-dependent, thus driven by macro-environmental factors rather than market conditions (Kivimaa et al., 2021; van den Bergh, 2013).

The degree of disruptive innovative success also depends on organizational factors. An advantage for disruptive innovation implementers is that incumbents face disruptive challenges in both organizational domain and role identities, whereas new entrants can unify their corporate purpose (Kammerlander et al., 2018). Sustainability-oriented organizations generally unite behind a clear direction, resource abundance, collaborative encouragement, positive reinforcement and accountability (Geradts & Bocken, 2018). While new entrants of the energy sector might create a corporate culture that fosters disruption, an incumbent often misses industry disruptions and fails to adapt due to their deep and complicated expertise of the energy sector (Dillon, 2020).

However, disruptive innovation theory has shortcomings. Firstly, the validity and generalizability often go ignored in academic literature (King & Baatartogtokh, 2015). Furthermore, qualitative research is prevalent, whereas quantitative researchers often find that disruptive innovations are rare, and responded to effectively (King & Baatartogtokh, 2015). Si & Chen emphasize this, and highlight a growing inconsistency between disruptive innovation theory and business applications (2020). Moreover, the ambiguity surrounding the term disruption has led to innovations being wrongly defined as disruptive innovations (Christensen et al., 2018; Wilson & Tyfield, 2018). Disruptive innovations are simple, accessible and affordable, rather than dramatically changing the business operations of a sector (Dillon, 2020). Since green energy products need policy support to disrupt the energy sector, one can ask whether or not green innovations can be considered disruptive innovations. Within the energy sector, disruptive innovation is too narrow of a concept to be a central framework for low-carbon transitions (McDowall, 2018). While research has concerned energy system disruption (McDowall, 2018; Tyfield, 2018; Johnstone et al., 2020; Ferràs-Hernández et al., 2017), general research on disruption innovation theory has been limited (Kivimaa et al., 2021; Christensen et al., 2018).

The review of the literature indicates that disruptive innovations within the energy sector is limited by policy forces, which goes against the disruptive innovation definition coined by Christensen (1997). Usually new entrants face less challenges and less pressure, meaning green entrepreneurs can play a disruptive role in the upcoming energy transition. However, within the energy sector, societal forces play a bigger factor than market drivers. Consequently, further research is required into green entrepreneurship and their societal drivers, as to better assess

the disruptive impact entrepreneurs may leave on the market. Additionally, within green hydrogen, both green energy disruption and green entrepreneurship should be connected to hydrogen entrepreneurship. These themes will be discussed further.

3.3 Green Entrepreneurship

Increased attention on disruptive innovation theory in entrepreneurial studies has stimulated a significant impact on entrepreneurial activities (Wilson & Tyfield, 2018; Ferràs-Hernández et al., 2017). Ferràs-Hernández et al. argue that disruption in conventional fields is led by outsiders with entrepreneurial experience (2017). Yet entrepreneurial characteristics are heterogeneous, making it difficult to define the role and education of an entrepreneur (Jones & Matlay, 2011). These factors, among others, serve as drivers for entrepreneurial attractiveness, and play a leading role in the entrepreneurial variety worldwide. However, only industry factors are used to explain entrepreneurial variations, and location factors such as institutional frameworks and market environments often go ignored (Kourtit et al., 2011). Additionally, entrepreneurs are influenced by ecological and technological factors (Bhat & Khan, 2014). Entrepreneurial drivers are therefore scattered and by creating a set of entrepreneurial drivers, understanding of entrepreneurial environments can be established.

Internal motivations that determine uncertainty, and consequently the attractiveness of entrepreneurial activities can hold industrial and personal characteristics: industrial in the sense of the technology’s state, whereas personal characteristics are determined through individual, environmental or cultural factors (Meijer et al., 2007). Globally, the word ‘entrepreneur’ is hard to define given the heterogeneity of entrepreneurs, yet the definition of ‘entrepreneurship’ is treated homogenously (Haldar, 2019; Eitan et al., 2020). This creates ambiguity around the definition of ‘green entrepreneurs’, and how this would translate into the entrepreneurial activities of green energy innovations. To determine the latter, one first has to define green energy entrepreneurs under a precise term.

Green energy entrepreneurs aim to profit from environmentally compatible business operations (Lotfi et al., 2018), and generally aim to seize entrepreneurial opportunities that minimize environmental impact and maximize societal impact (Sneddon et al., 2006). Yet green entrepreneurs differ in motivations, leading to several behaviour-based green entrepreneurial typologies (O'Neill & Gibbs, 2016).

Linnanen developed four green entrepreneurial typologies based on two drivers: “desire to make money”, and “desire to change the world” (2002). The four results either categorize an entrepreneurs as having low motivations for systematic or economic orientation (Self-employed

green entrepreneurs), a high motivation for both (successful idealists), a desire for money over systematic change (opportunists), and those who desire systematic change over money (non-profit business) (Linnanen, 2002).

Walley & Taylor developed further typologies of green entrepreneurs, but consider economic orientation and structural influence as drivers: those with high economic orientations and soft structural influences (personal networks influences such as friends and family) would be considered an “ad hoc enviropreneur”. One with hard structural influences (through government regulation) and a sustainability orientation is a “visionary champion” who aims to transform a part of an existing market. There are economical, hard structured entrepreneurs, known as “innovative opportunists”, and finally sustainability oriented, soft structured entrepreneurs, or “ethical mavericks” (2002).

Green entrepreneurs have their own set of internal motivations influenced by institutional factors. Among these factors are three drivers that determine Linnanen’s sustainable business segments: “Geographical influence”, or the level of impact the business segment has on sustainability issues. “Reason for market emergence” describes whether the sustainable business arose from government regulation or the free market. And “degree of enforcement”, the level of government intervention within the market segment (2002). Four sustainable business segments came forth from these drivers, as depicted in Table 1.

Table 1: The Sustainable Business Segments as formulated by Linnanen

The contributions by Linnanen and Walley & Taylor help refine the definition for green entrepreneurs and the drivers behind entrepreneurial inclinations (2002; 2002). At the same time, these typologies may categorize an entrepreneur in a specific segment with its own limitations. Given that three-hundred definitions of ‘sustainability’ exist (Santillo et al., 2007), agreeing on a ‘green entrepreneur’ definition proves difficult (Redclift, 2005; Sneddon et al., 2006).

Drivers for green entrepreneurship are diverse (Meijer et al., 2007), and determined by both internal motivations, and external landscapes. Given that green entrepreneurship has a vast range of sustainability definitions (Santillo et. al, 2007), more research needs to be done into general drivers for all green entrepreneurs, as well as for typologies and business segments of green entrepreneurs (Linnanen, 2002; Walley & Taylor, 2002). The developed connection between entrepreneurship and disruptive innovation, as per Wilson & Tyfield and Ferràs-Hernández et al. (2018; 2017), may boost disruptive innovation practices, and bring sustainability into the conventional energy economy, as will a clear definition of ‘green entrepreneurship’. Additionally, the literature reviewed the vast range of macro-environmental and industry drivers and showed that no clear set of drivers has been established (Kourtit et al., 2011; Bhat & Khan, 2014). A clear set of market drivers would help entrepreneurs with analysing opportunities and threats within the energy sector. Within green hydrogen, limited commercialization has hindered research into the effects of disruptive innovation and entrepreneurial implementation (Quarton & Samsatli, 2018; Martin et al., 2020). To further understand the market for disruptive innovators and entrepreneurs, further analysis should be done on the macro-environmental and industry drivers for green energy entrepreneurs.

3.4 Macro-environmental and industry drivers

Macro-environmental and industry drivers serve as impacts that influence disruptive innovation, entrepreneurial inclination and market competitiveness. Macro-environmental factors are of “political, economic, legal, social, cultural, demographic, competitive, technological, physical, natural, and ecological” nature (Bhat & Khan, 2014).

Macro-environmental factors are influenced by regulatory frameworks that target socio-economic and socio-political goals. Socio-socio-economic drivers intertwine with politics: many regulations influence individual and domestic economies and often require governmental and public commitment (Damette & Marques, 2018). Furthermore, RE policies face a trade-off between social promotion and economic cooldowns (Marques & Fuinhas, 2011). Within the green economy, socio-economics are often situationally defined by its policies (Pahle et al., 2016). Additionally, there is a general lack of evidence on drivers influencing renewable options (Marques & Fuinhas, 2011), while existing studies assess single countries or drivers in a short-term perspective (European Commission, 2017, Damette & Marques, 2018). This ignores the effects of long-run and cross-country implications.

EU countries have deployed different RE policies that target political and socio-economic incentives, but variations stem from unique resource capacities, public opinion, and

institutional systems (IEA, 2018). This is supported by recent policymaking analysis, which shows that specific local and national contexts, along with unique country circumstances often go ignored (National Renewable Energy Laboratory, 2018). For instance, RE policies have local socio-economic implications and would require citizens to carry the cost burdens (Marques & Fuinhas, 2011). Additionally, local social acceptance is essential for a successful RE implementations, specifically hydrogen (Van Bree & Bunzeck, 2008). Currently, a majority of the EU public is unaware of developments within hydrogen technologies (European Commission, 2017).

A growing concern within RE policies is the limited consistency of incentives that boost RE resilience. Many policies that create industry incentives for entrepreneurs are nearing expiration, meaning that RE stakeholders will face policy uncertainties and financial challenges (IEA, 2020b). Additionally, RE has not been standardized in existing policies. While various policies exist, they generally promote one energy more so than the other (Johnstone et al., 2008). This limits the systematic growth of RE, which requires more effective and comprehensive policies that target RE homogeneously. This can ensure the promotion of renewable competition, innovation, and investment (IEA, 2018). With favourable conditions, RE can surpass coal in both capacity and electricity generation (IEA, 2020b).

The lack of interconnected macro-environmental drivers hinders the future inclination of entrepreneurial and innovative ventures. It is increasingly harder to interconnect socio-economic and socio-political drivers across various countries with different macro-environmental priorities (IEA, 2018; National Renewable Energy Laboratory, 2018). Additionally, the political environment is ever-changing (IEA, 2020b), which highlights the need to understand industry drivers that may affect innovative entrepreneurs.

Gartner & Porter argue that competitive rivalries, powerful buyers, powerful suppliers, potential new entrants, and substitute products all influence market competitiveness (1985). Contextually, this would mean that the energy market offers little to no competitiveness, as indicated by low buying bower (Markides, 2012; Simanis & Hart, 2009), a lack of natural competition (McDowall et al., 2013; McDowall, 2018), and its macro-environmental dependence (Kivimaa et al., 2021; van den Bergh, 2013).

However, structural changes in the market are also connected to the entrepreneurial environment and entrepreneurial decision-making (Bhat & Khan, 2014). Innovative entrepreneurs have destabilized the energy sector, and caused structural changes in the competitive market (McDowall, 2018; Kivimaa et al., 2021; Johnstone & Kivimaa, 2018; Matschoss & Heiskanen, 2018; Martin, 2016; Wainstein & Bumpus, 2016). Yet with uncertain

institutional environments (van Rooijen & van Wees, 2006; IEA, 2020b), and a natural dependence on said environments (Kivimaa et al., 2021; van den Bergh, 2013), the market competitiveness will largely be determined by the macro-environmental landscape.

Cross-collaborative efforts are therefore growing more important. Cross-collaborative efforts have proven to benefit entrepreneurial innovation (Anderson & Li, 2014; Heidemann-Lassen et al., 2008). Establishing a diverse network of like-minded stakeholders can spark entrepreneurial growth, as network positioning directly affects the success of innovation performance (Renewable Hydrogen Coalition, 2021). An entrepreneurs’ network position may provide strategic resources that influence the performance of the innovation (Zhou et al., 2021). Hydrogen is relatively young and carries a high specific cost and low efficiency (Blanco & Faaij, 2018). Accelerated deployment of hydrogen will thus require public support, as well as collaborations within the private sector (Energy Transition Institute, 2020). Currently, governments fail to provide policies that can spark cost-competitiveness for hydrogen (IEA, 2018). Additionally, green hydrogen technologies are further from commercialization and challenges surround the potential development (IRENA, 2020). However, investments in R&D and innovation can develop technological applicability to local circumstances, and national competence on the application of green technologies (IEA, 2018).

Hydrogen energy has seen limited implementation in the energy market, and analyses concerning research feasibility merely focus on one aspect of challenges for implementation, such as exclusively the economic, logistical or political challenges that should be overcome before commercialization (Menachem, 2018). Connecting macro-environmental and industry drivers could help green entrepreneurs and disruptive innovators in assessing market obstacles, thus thinning the gap between conventional energy costs and those of RE. Additionally, a set of drivers can assess cross-collaborative needs. Within GH implementation, entrepreneurship will likely play a leading role, and therefore hydrogen entrepreneurship requires further analysis, as discussed next.

3.5 Hydrogen Entrepreneurship

The finiteness of conventional energy has allowed entrepreneurial activities to address a potential energy security crisis. Hydrogen can play a critical role in addressing these issues (Midilli and Dincer, 2007; Haar & Theyel, 2006). However, there are few hydrogen projects, and current regulation inhibits hydrogen entrepreneurs from progression (Hydrogen Council, 2020). Green hydrogen is far from reaching a mainstream market, however its disruptive advantages over other energy sources offer opportunities.

Entrepreneurial and public involvement is needed for hydrogen competitiveness. Technological advancements will not reach cost competitiveness until 2030 (Quarton & Samsatli, 2018). Challenges include a lack of investment in education, media, society, and the private and public sector (Midilli and Dincer, 2007). This has inhibited hydrogen entrepreneurs from developing strategic business models that capture economic growth and commercial deployment. Ultimately, the substitution of conventional energy for hydrogen will depend on the interpretation of successful energy strategies (Menachem, 2018).

There is a growing demand for renewable gas energy, and a desire to reduce dependencies on foreign countries (Leonzio, 2017). Under the right conditions, hydrogen can meet these energy demands, along with addressing electricity cost issues (Aboumahboub et al., 2010; Parra et al., 2017). The EU imports natural gas and crude oil at the rate of 16% and 69% respectively (European Commission, 2021a), making the need for self-sustaining energy production more important. Green hydrogen’s nascent stage offers entrepreneurs opportunities for first-mover advantages and high penetrations within the energy market (Quarton & Samsatli, 2018). Interest in hydrogen as an energy source has also spread to private and public stakeholders (IRENA, 2020), meaning commercialization of hydrogen, and regulations promoting hydrogen commercialization should follow. The same report acknowledges that hydrogen’s dependency on infrastructure (which lacks), and the non-existing market for green hydrogen are the main barriers entrepreneurs currently face.

Furthermore, a current lack of entrepreneurial activities in the hydrogen segment due to macro-environmental barriers, is addressed by EU funding to support clean technology entrepreneurship and innovation (European Commission, 2021b). This funding supports entrepreneurs and innovators in restructuring the energy source input for hydrogen by substituting fossil fuels for RE. Additionally, the Renewable Hydrogen Coalition (under EU funding) aims to build networks for start-ups, entrepreneurs, and innovators that seek to replace conventional energy sources with renewable hydrogen (European Commission, 2021b). Nevertheless, hydrogen entrepreneurship is limited. Most hydrogen projects are demonstratively working with commercialized technology (Quarton & Samsatli, 2018), which limits the potential for immediate hydrogen innovations. Yet several emerging technologies offer opportunities for growth and can potentially complement or substitute commercialized fuel cell technologies (Ogawa et al., 2018). Since green hydrogen technologies are inhibited by socio-economic and political barriers, a shift to human-centricity, rather than techno-centricity, may boost entrepreneurial competence in emerging hydrogen energy systems (Quarton &

Samsatli, 2018). In other words, entrepreneurs would benefit more from customer input to address needs that can be resolved through the innovation of hydrogen energy systems. Green hydrogen is currently considered an unattractive energy source for socio-economic and political reasons. Hydrogen itself is far from commercialization, though increased stakeholder interest may allow the realization of hydrogen through disruptive innovations (IRENA, 2020; European Commission, 2021b). Consequently, this creates opportunities and threats for entrepreneurs committed to green hydrogen business models. Drivers have been acknowledged (Midilli & Dincer, 2007; Hydrogen Council, 2020), but a set list of those drivers (from an entrepreneurial perspective) has not been established. Limited entrepreneurial involvement and ambiguous strategic planning constrain the growth of entrepreneurial implementations of hydrogen as a disruptive innovation (Quarton & Samsatli, 2018; Zhou et al., 2021) which in turn leaves research on market drivers interpretive and speculative (Menachem, 2018).

The lack of business models, market frameworks and regulatory support leaves ambiguity for green hydrogen entrepreneurs, yet the EU has committed to the development of a global hydrogen market that identifies and overcomes key barriers within hydrogen’s supply chain (Atanasiu, 2019). This is bound to aid entrepreneurial activities within green hydrogen in both conventional and niche energy markets.

The thesis will therefore continue exploring hydrogen entrepreneurship within the scope of disruptive innovations, and defines hydrogen entrepreneurship as business activities that utilize renewable hydrogen energy as a disruptive innovation to replace market structures, production methods and consumptions patterns within the conventional energy market. By defining hydrogen entrepreneurship, the research purpose will be consistent with the established research questions while additionally connecting hydrogen entrepreneurship with disruptive innovation theory.

3.6 Gaps in the Knowledge

Various literature gaps indicated limitations of disruptive innovation theory, green entrepreneurship, macro-environmental, and industry drivers, and their applications to green hydrogen and the entrepreneurial activities that follow. Currently, disruptive innovation theory misunderstands its applications within the green energy sector (Kivimaa et al., 2021; Si & Chen, 2020; Christensen et al., 2018; Wilson & Tyfield, 2018). By narrowing those gaps, the market environment can be better assessed to potentially mitigate climate change.

However, the market environment is influenced by macro-environmental and industry drivers. There is either a lack of evidence, or scattered understanding, on RE drivers (Marques & Fuinhas, 2011; Pahle et al., 2016). Additionally, established studies have overlooked driver effects on cross-country implications (European Commission, 2017; National Renewable Energy Laboratory, 2018). Simultaneously, only one sector or RE source was generally researched (Menachem, 2018; Johnstone et al., 2008; McDowall, 2018), thus ignoring RE innovation as a systematic impact, although its impact as a systematic concept might be limited (McDowall, 2018).

Research on hydrogen drivers often analysed solely the political, economic or logistical challenges posed against hydrogen (Hydrogen Council, 2020; Menachem, 2018; IRENA, 2020; IEA, 2020a), and thus failed to address driver interconnectedness. Renewable drivers that have been acknowledged only relate to short-term perspectives that fail to address long-run institutional implications (Damette & Marques, 2018). Additionally, RE policies may benefit some RE sources more so than others (Johnstone et al., 2008), thus leaving uncertainties regarding RE implementation success as a systematic concept.

Socially, a general lack of public awareness on hydrogen technologies is currently stalling development (European Commission, 2017). This supports Menachem, who argued that social awareness about sustainability issues should be fostered to promote RE (2018). As for green entrepreneurship, distinguishing themselves as a heterogeneous group separate from ‘conventional’ entrepreneurs has proven to be difficult (Haldar, 2019, Eitan et al., 2020). Additionally, entrepreneurial drivers and market drivers for entrepreneurs are diverse (Meijer et al., 2007), and limited research has analysed the effects of disruptive innovators and green entrepreneurs within hydrogen (Quarton & Samsatli, 2018; Martin et al., 2020).

The literature review analysed major themes in disruptive innovation, entrepreneurship and market drivers for the energy sector. Initial findings show that, in line with this thesis purpose, there is a need to discuss the interconnectedness between disruptive innovations, green entrepreneurship and market drivers for the energy sector. This developed further within hydrogen, where entrepreneurial and market drivers are not clearly defined, which currently inhibits the development of disruptive innovations in this specific area. Further research into RE innovations and entrepreneurship, how they are being facilitated through market drivers, and how those market drivers can create cross-collaborative efforts is needed. This requires the establishment of unique sets of conditions that foster cross-collaborative strategies for entrepreneurial innovation, and that further growth of green entrepreneurship in the context of green energy. To accommodate these areas of future research, the author conducted a

methodical approach that addresses the research purpose, and connects it to initial findings. The process of finding this information will be discussed in the following chapters.

Methodology

_____________________________________________________________________________________

This chapter explains the methodological process the author chose to conduct the research study. First the research philosophy is established and explained in relation to the research purpose. This is followed by the research approach, again defined and explained in relation to the research purpose. The research strategy follows, where the author justifies the choice of qualitative data and why it benefits the research purpose. Lastly, the research design is addressed, explaining why a case study inclusion was most appropriate for the research study.

4.1 Research Philosophy

The research philosophy consists of two branches: epistemology, or “nature of knowledge”, and ontology, or “nature of reality” (Wilson, 2019). The epistemology considers what we accept as knowledge, divided into interpretivist, positivism or pragmatism paradigms (Wilson, 2019). This study will follow an interpretivist paradigm for two reasons. Firstly, interpretivist approaches research by focusing on at one subject in-depth (Wilson, 2019). Given that the research concerns the subject of green hydrogen, under the greater phenomenon renewable energy, the purpose is to actively interact and engage within the field of green hydrogen, as to build conclusions. Furthermore, interpretivist allows the researcher to enter the social world surrounding the initial research subject (Wilson, 2019), something essential in understanding entrepreneurial inclinations for green hydrogen.

Ontology asks research to perceive the social construct of the world (Wilson, 2019). In other words, ontology looks at how researchers perceive global behaviour in the social context. Ontology is divided into subjectivism or objectivism (Wilson, 2019). This study will consider the paradigm of subjectivism due to its established links with interpretivist. Subjectivism is connected to interpretivist in the sense that subjective motivations, attitudes, and social interactions are considered when examining the responses to the researched subject (Wilson, 2019). In this research, different policies and socio-economic activities will have different effects on entrepreneurial inclinations, depending on the entrepreneur’s background. By establishing an epistemology that is both interpretivist and subjectivist the research will consider green hydrogen in a social context, thus allowing for various interpretations of the data collected, and room for future research.

4.2 Research Approach

An inductive approach to research was chosen. The inductive approach focuses on theory-building, where one first observes a phenomenon and then seeks to establish generalisations on the phenomenon observed (Hyde, 2000; Shepherd & Sutcliffe, 2011). Given the nascent state of green hydrogen, there are very few, if any, established theories on the drivers pushing entrepreneurial activities within the sector, so observations are needed to reach such theory (rather than deductively looking for existing theories in the data). Additionally, made observations fall under different theoretic lenses – disruptive innovation, political science and strategic entrepreneurship– and will thus have to be observed in order to connect theories under one perspective. The inductive research approach generally collects data and then develops a theory based on the data analysis (Wilson, 2019). The author will therefore develop a theoretical framework from the analysed data. Current literature highlights that further data is required, supporting an inductive approach to best develop theory on the pre-existent and newfound data.

4.3 Research Strategy

Inductive research is very often associated with qualitative research (Hyde, 2000). Qualitative research is thus chosen as the most appropriate strategy. The qualitative nature of the study will allow interpretation and subjectivity of the reader. The political, socio-economic and entrepreneurial drivers to be examined come with a sense of ambiguity. Additionally, the subjectivist ontology of this research means that there is room for change depending on the respondent. To allow ambiguity and subjectivism, the interviewees were qualitatively assessed rather than quantitatively.

The research conducted will have primary insights from interviews, and secondary data from respected organizational documents. The interviews, which are semi-structured, were designed to initiate discussions about disruptive innovation, entrepreneurship, and a cross-collaborative energy industry. Questions were developed with these topics in mind, and then sent to the interviewees to offer preparation before the interview. This extra preparation was granted to foster more objective, accurate and knowledgeable insights from the participants.

Secondary data was used to synchronize the newfound insights with already existing literature on green energy innovation and its market drivers as to connect established theory with the upcoming theoretical contributions put forth by the author (Bansal & Corley, 20212). Reputable government organizations have conducted various studies on the current and future

RE landscape. Through a combination of both new and existing data, the author aimed to link the fields of management, environmental innovation, and entrepreneurship to create a more integrated framework for renewable energy entrepreneurs.

While quantitative data would have served as more objective research, the general perception of entrepreneurial innovation is considered more pressing in the existent literature, and is in turn dependent on entrepreneurial motivations. The various backgrounds of the interview participants, as well as their contributions differ from each other. The inclusion of different perspectives is considered a transferability advantage, however, findings should also be considered from the context in which they arose.

4.4 Research Design

The design chosen to accommodate the research purpose is a case study. A case study is “an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon in depth and within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident” (Farquhar, 2012a). Therefore, the author formulated three criteria before deciding whether a case study was fit for the research.

Firstly, a presence of a contemporary phenomenon needs to be present. In the author’s research this phenomenon is presented within the scope of disruptive innovations in RE markets, supported by several studies that highlight the developments in disruptive energy systems (McDowall, 2018; Johnstone & Kivimaa, 2018; Tyfield, 2018; Johnstone et al., 2020; Ferràs-Hernández et al., 2017). The phenomenon can be further narrowed down by specifically looking at green hydrogen, which is influenced by contemporary energy strategies and developments in stakeholder interests (Menachem, 2018; IRENA, 2020). In this research the contemporary phenomenon, disruptive energy innovations, can thus be studied further under a specific lens, which is presented as green hydrogen within this research.

Secondly, a desire to understand the social, or real-life context has to be present. Within the author’s research the social context of connections between disruptive innovation, entrepreneurship, and cross-collaborations are present (Wilson & Tyfield, 2018; Anderson & Li, 2014; Heidemann-Lassen et al., 2008), whereas for green hydrogen, drivers have been limited to one area of research (Midilli and Dincer, 2007; Hydrogen Council, 2020) The need for interlinkage between disruptive innovations, green entrepreneurship, and its translation into green hydrogen thus requires an understanding of real-life applications of these drivers, which is further analysed in this research.

Lastly, an unclear understanding of the phenomenon and its boundaries that influence the social context is a criteria for it to be chosen as the phenomenon to be explored in research. In this author’s research, the established phenomenon, green disruptive innovation, is limited by boundaries that cause uncertainties in real-life disruptive innovation applications (Si & Chen, 2020). Additionally, ambiguity surrounds both entrepreneurs and the energy market (Meijer et al., 2007; O'Neill & Gibbs, 2016; IEA, 2018; National Renewable Energy Laboratory, 2018; Pahle et al., 2016). Within green hydrogen, a lack of integrative research has further developed an unclear understanding of the boundaries that influence the social applications of the energy source (Menachem, 2018; Quarton & Samsatli, 2018; Martin et al., 2020).

To address these three criteria the author chose to analyse the phenomenon of green disruptive innovations by entrepreneurs and discuss it through the more specific lens of green hydrogen implementation. The analysis considers the real-life and social contexts of green energy innovation to better understand the market boundaries that inhibit future applications of green hydrogen. That is, the research analyses green hydrogen, to establish the drivers that serve as boundaries in the social context of the phenomenon, green disruptive innovation. By doing so, the uncertainties between drivers and the phenomenon can be interconnected, as to then create a clearer framework that can aid in the understanding of real-life applications of green disruptive innovations. This would satisfy both the second and third criteria formulated by the author.

Furthermore, the nascent and contemporary relevance of the phenomenon and the case study requires a contextual understanding of both social implications as well as real-life applications, which would satisfy all the criteria. The ability to create a framework that addresses the social context, phenomenon, and its boundaries would serve as a template for various stakeholders interested in developing green disruptive innovations with entrepreneurs.

Given the current state of green disruptive innovations, real-life applications are necessary to progress both entrepreneurial activities and green hydrogen innovation. By conducting a case study, the author aims to connect theoretical literature to real-life insights on disruptive energy innovations, in hopes of creating a more cohesive understanding of entrepreneurial involvement within innovation implementations, as well as green hydrogen’s role in a real-life context of a systemic energy system.