Enabling and hindering factors to successfully governing

ecosystem services in a cross-collaborative setting

Bianca Whitcher

Alice Mattsson

Main field of study – Leadership and Organisation

Degree of Master of Arts (60 credits) with a Major in Leadership and Organisation Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organisation for Sustainability (OL646E) 15 credits

Spring 2020

Abstract

This research paper hones into the field of natural resource management. More specifically, it investigates cross-sector collaborations around the governance of ecosystem services in the forestry sector. As ecosystem services are inherently challenging to sustainably and collaboratively manage due to the multitude of vested interests existing among stakeholders, there is a need to enhance the understanding of the collaborative process. Therefore, the main purpose of this research is to provide an understanding for which factors hinder or enable the successful governance of ecosystem services in a cross-collaborative setting, and how these factors interrelate with each other. Included in this paper are four cases from within Europe where local stakeholders in collaboration with varying actors from forest-management, policy, public, tourism, research, Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) and business sectors, collaborate in order to effectively manage forest ecosystem services. The main findings suggest that organisational factors, relational factors, cultural factors, unforeseen external events, communication, engagement and their associated sub-factors are most notable. Additionally, this study showcased that most of these factors are interrelated with each other in a complex manner.

Keywords; Cross-sector collaboration, ecosystem service governance, forest management, sustainable

Table of contents

1. Introduction 3 1.1 Background 3 1.2 Research Problem 4 1.3 Aim/Purpose 4 1.4 Research Questions 4 1.5 Terminology 41.6 Structure of the paper 6

2. Previous research and theoretical framework 7

2.1 Literature Review 7

2.1.1 Hindering factors to successful cross-sector collaboration 7

2.1.2 Enabling factors for successful cross-sector collaborations 8

2.1.3 Enabling and hindering factors in collaborative natural resources governance 9

2.1.4 Summary of factors 10

2.2 Theoretical framework 12

2.2.1 Systems theory and systems thinking 12

2.2.2 System dynamics and causal loop diagrams 13

3. Method 15

3.1 Research approach 15

3.2 Research design 15

3.2.1 Case oriented research 15

3.2.2 Case Characteristics 16

3.2.3 Selection and delimitation 17

3.2.4 Case descriptions 17

3.3 Data Collection 19

3.3.1 Semi-structured interviews 19

3.3.2 Data analysis and Coding strategy 20

3.4 Limitations 20

3.5 Validity and reliability 21

4. Empirical findings 23 4.1 Summary of factors 23 4.2 Hindering factors 25 4.3 Enabling factors 28 5. Analysis 32 5.1 Interconnectivity of factors 32 6. Discussion 35 6.1 Theoretical contributions 35

6.2 Discussion of main findings 36

1. Introduction

1.1 Background

Cross-sectoral collaboration has been recognised as a novel method when attempting to address some of the complex challenges the world is in the midst of navigating (Bryson, Crosby & Stone, 2006; Gray & Stites, 2013). This is due to the collaborative configuration harvesting its benefits from a diverse range of perspectives and approaches while simultaneously aiming towards benefiting all those involved in the process (Lozano, 2007). Collaborating across sectors is also thought to create opportunities for establishing mutually reinforcing systems that utilise the unique capabilities and resources of each party, resulting in outcomes that surpasses those of sectors acting in isolation (Googins & Rochlin, 2000). Due to these beneficial outcomes, there has been a rapid increase in cross-sector collaborations in the last 15 years (Gray & Stites, 2013).

One particular field where collaborating across sectors has been recognised as a favourable approach to utilise is within sustainable development. This is due to the field being concerned with trans-disciplinary and multi-layered social and environmental challenges (Wells, 2013) that demands we obtain knowledge and insights from various disciplines (Mihelcic et al., 2003). Hence, single-actor solutions cannot be seen as a viable option when trying to “...meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (Brundtland et al., 1987).

A notable area within sustainable development where cross-sectoral collaboration has proved particularly advantageous is when governing ecosystem services, which are conceptualised as the goods and services provided by nature which bring direct or indirect value to humans (The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005). In most cases, these ecosystems and their associated services span across environmental and socio-economic boundaries, which makes non-collaborative approaches insufficient in managing these systems sustainably (Bodin et al., 2016). Thus, a central assumption has emerged from contemporary research claiming that “...governance arrangements incorporating collaboration across multiple scales and jurisdictions are needed in order to meet the collective dilemmas arising from a world being socially and ecologically increasingly interconnected” (Bodin et al., 2016, p.39). Furthermore, the suitability of establishing cross-sector collaborations around the management of ‘public goods’ is due to various stakeholders being dependent or having a vested interest in these services, ranging from Indigenous communities, those who make a living off resources, those who enjoy ecosystems and resources recreationally and those who advocate for natural resource conservation, among others (Gray & Stites, 2013).

In order to establish an effective collaboration, the inherent systemic interconnectivity of the social and the ecological aspects must be taken into account. This requires an understanding of the interplay that exists between actors and the collective problems that these collaborations seek to address (Bodin et al., 2016). Deeply incorporating this understanding not only revolves around having a multidisciplinary focus, but also demands the incorporation of various perspectives from non-disciplinary experts who either have an indirect or direct stake in the outcomes of the collaboration (Constanza, Leemans, Boumans & Gaddis, 2007). Additionally, the governance of these ecosystems must aim towards supporting environmental adaptiveness and resilience (Heuer, 2011). Based on this understanding, the successful governance of ecosystems in a cross collaborative-setting requires including the perspectives

of a broad stakeholder group with the objective of supporting these services in being more adaptive and resilient.

1.2 Research Problem

Ecosystem services benefit society and stakeholders in a number of ways. This calls for the collective effort from multiple sectors in governing the resources that provide these services. Cross-sector collaboration has been recognised as a beneficial approach when trying to realise a successful governance of these services. However, actualising these collaborations can be challenging due to the inherent complexity of ecosystems and the multiple actors involved, which calls for deeper understanding of the collaborative process (Guerrero & Hansen, 2018). More specifically, there is a need to enhance the understanding of which critical factors spur collaborative efforts around the management of natural resources, as well as understanding the interconnectivity of these factors (Thellbro, Bjärstig & Eckerberg, 2018). Grasping a deeper understanding of these factors, which can either be facilitating or inhibiting, “...should be the first step towards designing new forms of public participation in resource policy decision making” (Selin & Chavez, 1995, p.194). Lastly, literature addresses the need to conduct more case studies on collaborative efforts around ecosystem governance “...in order to build a global repertoire of successes, failures and emerging best practices” (Heuer, 2011, p. 219). It is for this reason that this paper intends to investigate the factors which enable or hinder the successful governance of ecosystem services in a cross-collaborative setting.

1.3 Aim/Purpose

The main purpose of this research is to provide an understanding of which factors hinder or enable a successful governance of ecosystem services in a cross-collaborative setting. Successful in this context, refers to well-functioning collaborations which are achieving what they set out to do. The objective is also to describe how these factors interrelate with one another in order to gain insights into how these different factors affect each other and the overall collaboration. This in turn is believed to serve similar collaborations with useful and practical advice, with the ultimate purpose of contributing to knowledge and research within the field of collaborative ecosystem service governance.

1.4 Research Questions

RQ 1. Which factors enable or hinder the successful governance of ecosystem services in a cross collaborative setting?

RQ 2. How do these factors affect and interrelate with each other?

1.5 Terminology

In this section we provide the most relevant definitions and conceptualisations of terms used frequently throughout the literature and our research. It is worth noting that some terms have multiple definitions.

For this reason we have chosen to apply those which we deem most relevant to the context of this research. Some terms are additionally used synonymously which is thereby stated in the definition.

Cross-sector collaboration, used synonymously with cross-collaboration.

Authors Bryson, Crosby and Stone (2006, p. 44) define cross‐sector collaboration as the “...linking or sharing of information, resources, activities, and capabilities by organizations in two or more sectors to achieve jointly an outcome that could not be achieved by organizations in one sector separately”. More generally, cross-sector collaboration can be seen as a process where parties stemming from diverse backgrounds explore their differences in opinions and search for joint solutions that expand beyond what they originally thought was possible (Gray, 1989). Cross-sector collaborations is additionally used as an umbrella term which encompasses a range of models from ‘public-private partnerships’, ‘shared value’ to ‘collective impact’ as well as alliances which are yet to be categorised (Gold, 2016).

Collective governance, used synonymously with collaborative governance

Collective governance and collaborative governance are defined as an innovative model of governance which includes a partnership of diverse stakeholders improving the management and delivery of services. Collective governance often manifests in multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) which brings together government, the private sector and civil society and pools resources, capacity and skills, in order to address complex challenges (Thindwa, 2015). A more concrete definition is provided by Ansell and Gash (2008), defining collaborative governance as;“A governing arrangement where one or more public agencies directly engage non-state stakeholders in a collective decision-making process that is formal, consensus-oriented, and deliberative and that aims to make or implement public policy or manage public programs or assets” (p. 544).

Ecosystem Services and Forest Ecosystem Services

The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, (2005 p. V)drafted the widely used definition of ecosystem services as “the benefits people obtain from ecosystems” and further conceptualised the term into four categories. These are 1) provisioning services such as food, water, timber, and fibre, 2) regulating services that affect climate, flood, disease, waste, and water quality, 3) cultural services that provide recreational, aesthetic, and spiritual benefits, and 4) supporting services such as soil formation, photosynthesis, and nutrient cycling. For the purpose of our research we are particularly interested in Forest Ecosystem Services (FES) which are defined as goods and services which bring direct or indirect benefit to humans, be that social, ecological, emotional, physiological, psychological, economic or materialistic which derive from forest ecosystems1.

Ecosystem service governance

Ecosystem service governance can be defined as the processes, mechanisms, shared decision making and governing structures used for the management of ecosystems, especially for biodiversity conservation and ecosystem service provisioning (Rival & Muradian, 2013: as cited in Lienhoop & Schröter-Schlaack, 2018). Furthermore, ecosystem service governance unites knowledge from various disciplines and incorporates stakeholders with different perspectives in the process who either manage, understand and/or benefit from the services (Primmer & Furman, 2012). In close relation to this term is Ecosystem Based Management (EBM) which is defined as management, executed by policies, protocols and practices, based on the processes and interactions necessary to sustain ecosystems (Christensen et al., 1996).

1.6 Structure of the paper

The structure of this thesis is as follows; In the next section we display the main findings from our literature review. Presented here is namely the hindering and enabling factors to cross sector collaboration and collaborative natural resource governance. A summary of these factors is subsequently presented. Next we present the theoretical framework, followed by the method, methodology and a description of the four cases involved in this research. We go on to display how data was collected and thereafter illustrate our main empirical findings, followed by a summary of these findings. After this we present our analysis, the interconnectivity of these factors, followed by a discussion on the theoretical contributions, and finally, conclude the most important findings.

2. Previous research and theoretical framework

2.1 Literature Review

As previously noted, collaboration is seen as both desirable and necessary when trying to address complex issues in society (Bryson, Crosby & Stone, 2015). However, multiple theorists have pointed out numerous challenges involved with collaborating across sectors in both the public, non-profit, and commercial sector (Anderson & Jap, 2005; Hodge & Greve, 2005; Parise & Casher, 2003; Suen, 2005, as cited in Babiak & Thibault, 2009). Additionally, while scholars have conducted research on what hinders collaboration, research on what mechanisms which allow collaborations to thrive has simultaneously been elaborated on. Below is a review of what has been stated in regards to hindering and enabling factors in literature evident in cross-sector collaboration, where most articles refer to these factors as barriers and drivers.

2.1.1 Hindering factors to successful cross-sector collaboration

The first challenge refers to the relational aspect of collaborative experiences which influences the effectiveness of collaborative networks (Selin & Chavez, 1995). Firstly, a lack of prior experience with collaborating among actors involved in the network may cause negative implications to the collaborative process. This is because past collaboration experiences and lessons learnt can potentially mitigate risks which may develop with new collaborative networks (Collins & Gerlach, 2019). Additionally, if adversaries have occurred in the past where partners have had negative experiences with collaborating, consensus among actors is often difficult to reach (Selin & Chavez, 1995). Therefore, previous experiences with collaborating can act as a barrier to achieving successful collaborations. This is closely related to the barrier ‘negative perceptions of partners’ which can impede collaboration (Cairns & Harris, 2011). These perceptions may be formed from previous partnership experiences or formed independently through existing conflicting views or reputation (Gray, 1989; Heuer, 2011).

A lack of access to resources is also a notable hindering factor in establishing and maintaining collaborative networks. These resources can be financial, technological or conceptual, i.e knowledge (Calliari, Michetti, Farnia & Ramieri, 2019). Furthermore, institutional barriers are reported in literature, which include shortcomings in terms of horizontal and vertical coordination between private stakeholders and formal agencies as well as between different administrative levels within organisations (Biesbroek, Klostermann, Termeer & Kabat, 2013). Institutional culture can also hinder collaboration within environmental and resource management. In particular, rigid and centralised planning and processes impedes collaboration with local interest groups and hinders consensus based decision making (Selin & Chavez, 1995). A final external barrier apparent in collaborative networks is the logistical challenges associated with managing geographically dispersed partners (Babiak & Thibault, 2009) where the administrative bodies geographical location can affect the overall success of the partnership (Klenk & Hickey, 2013).

2.1.2 Enabling factors for successful cross-sector collaborations

Firstly, it is noted in literature that it is important for all partners to be on the same page when initiating collaborative projects, where goals and visions are shared. This is because it is not uncommon that the motivation to collaborate differ among partners involved, where goals of the project are dispersed (Gray & Stites, 2013). Therefore, a shared vision ought to be agreed upon as this can bridge potential discrepancies existing within the project (Gray & Stites, 2013). Additionally, it is thought that shared beliefs can lead to a lower transaction cost of involvement for stakeholders which in turn increases the likelihood of the collaborative process having engaged participants (Sabatier et al., 2005).

Closely connected to this aspect is to jointly decide on which problems need to be addressed. Especially important are that ‘linking mechanisms’, i.e. sponsors, agree on this when initiating collaborative projects (Bryson, Crosby, & Stone, 2006). Furthermore, agreeing on explicit norms, management processes and practical aspects must be decided upon during initial stages of the collaboration process. As stated by authors Gray and Stites (2013) “The partnership is more likely to run smoothly and partners are less likely to violate each other’s expectations for good partner behaviour when partners take the time to sit down and agree on the procedures they will use for their interactions” (p.42).

Additionally, conflict over values, goals, procedures and roles is inherent in partnerships that span across sectors (Gray, 1989; Castro & Nielsen, 2001; Todd, 2002; Crosby & Bryson, 2005; Rauschmayer & Risse, 2005; Morse, 2010; as cited in Gray & Stites, 2013). Some would argue that this is a barrier, however, practitioners have pointed to the fact that the key to a collaboration’s success can be determined by how these conflicts are managed. Some scholars have also gone as far as to say that conflict has benefited the partnership. Gray and Stites (2013) exemplify the context of natural resource management where conflict has acted as a catalyst for negotiations. However, when conflict is not beneficial for the collaborative process, consensus based decision making among partners may aid in relieving some disagreement (Rondinelli & London, 2003; Doelle & Sinclair, 2006; Van de Kerkhof, 2006; Manring, 2007; Ansell & Gash, 2008; Weible, Pattison & Sabatier, 2010; Baldwin & Ross, 2012; as cited in Gray & Stites, 2013).

Leadership is identified in the literature as an essential factor in collaborative networks. This refers to the presence of an identified leader that shows support and commitment to the problem solving process and who does not advocate for a specific solution to the issue at hand. Ideally, an effective leader also secures resources, solves problems and oversees that operations run smoothly (Emerson, Nabatchi & Balogh, 2012). Additionally, those in a leadership position ought to possess skills that enable inclusiveness and representation (Gray & Stites, 2013). Furthermore, leadership is critical when establishing partnerships in the initial stages of the collaborative process (Gray & Stites, 2013; Emerson, Nabatchi & Balogh, 2012) as well as being necessary throughout the process (Bryson, Crosby & Stone, 2015). Collaborative networks with a centralised lead are assumed to be successful if both formal and informal leadership is present at multiple levels and stages of the process (Bryson, Crosby & Stone, 2006). However, it is important to pay attention to power imbalances, as asymmetries in power can have negative and long-lasting impacts on the collaborative network (Selin & Chavez, 1995; Babiak & Thibault, 2019; Gray, 1989).

Collective leadership, rather than individualistic leadership, may mitigate the risks of power imbalances. Gray (2008) and Ansell and Gash (2008) emphasise the significance of ‘shared leadership’

Leadership understood in this way is not stagnant. Rather, the act of leading within partnerships may shift in line with the ebbs and flows of the collaboration process as well as when new actors come into play. During these shifts, the leadership becomes dispersed throughout the collaboration, increasing the relevance of thinking in terms of ‘leadership’ rather than ‘leaders’.

Furthermore, trust is referred to as a critical factor and a prerequisite for establishing and maintaining a flourishing network of actors (Collins & Gerlach, 2019; Babiak & Thibault, 2019; Gray & Stites, 2013; Heuer, 2011), where the trust-building and cross-sector understanding ought to be continuous (Bryson, Crosby, & Stone, 2006). Otherwise, aligning individual interests and collective ones might be difficult which can impair the collaboration (Calliari et al, 2019). Understanding trust as a prerequisite for collaborations to thrive is relatively clear cut, however it’s worth noting that trust is not a mere interpersonal characteristic but rather an outcome of relations and experiences (Gray & Stites, 2013). In order for collaborative networks and projects to run smoothly, members, partners and stakeholders must perceive the collaboration network as an accepted and legitimate entity. For this reason, it is crucial for both internal and external legitimacy to be ensured. A perceived legitimacy sets the precedent for a sense of fair treatment, trust and understanding among stakeholders (Bryson, Crosby and Stone, 2015). Therefore, during initiation and throughout the process, those involved ought to strongly consider stakeholder analysis and be responsive to stakeholder needs as well as foster trust, manage conflict and build upon collaborators competencies (Bryson, Crosby, & Stone, 2006). Legitimacy is developed through structures, strategies and processes and must be accepted by stakeholders and members (Fligstein & McAdam, 2012; Suchman, 1995; as cited in Bryson, Crosby, & Stone, 2015).

Transparent and well-functioning communication is fundamental when developing and maintaining collaborative networks (Babiak & Thibault, 2009) as it can help overcome varying challenges which may be present within the network (Dubay et al., 2013). While much of this work must be face-to-face (Ansell & Gash 2008, Romzek, LeRoux, & Blackmar 2012, as cited in Bryson, Crosby & Stone), it may also include the formulation of ‘‘authoritative texts’ which can include formalities, mission statements, implicit norms and memoranda of understanding (Koschmann, Kuhn & Pfarrer, 2012; as cited in Bryson, Crosby and Stone 2015). These texts specify the collaborations “...general direction and what it is ‘on track’ to accomplish” (Koschmann, Kuhn & Pfarrer, 2012, p. 337) which ideally mobilise partner consent, attract resources and generate collective agency (Bryson, Crosby and Stone, 2015).

Finally, literature has highlighted the role of competencies and capacities among partners in cross-sector collaborations. Certain competencies are seen as more desirable than others, such as openness to collaborating, interpersonal understanding, the will to achieve a common good, the ability to analyse and involve stakeholders, plan strategically, and participate in teams across boundaries (Getha-Taylor & Morse, 2008).

2.1.3 Enabling and hindering factors in collaborative natural resources

governance

Collaborating in the context of natural resource management poses unique challenges to the collaborative process. For instance, there are often competing interests involved, as the partners’ objectives often differ depending on whether they are a supplier or beneficiary of the ecosystem service (Rode, Wittmer, Emerton & Schröter-Schlaack, 2016). There is also often a lack of coordination between beneficiaries and providers, as they are often vertically and horizontally dispersed across

sectors (Plieninger et al., 2012, Wüstemann et al., 2017: as cited in Lienhoop & Schröter-Schlaack, 2018). Collaboration in this context can further be problematic due to stakeholder histories which might involve conflict, cultural barriers or lack of experience with collaborating (Dubay et al., 2013). The collaborative potential in the forest industry is also challenged by a resistance to change and varying visions of management (Näyhä & Pesonen 2014). Additionally, collaborative efforts in this particular setting can be limited by rigid governmental policies and procedures (Moote & Becker, 2003). Lastly, a lack of adequate and reliable resources for supporting operations such as administration, capacity building, project planning, staff time, education, monitoring, knowledge exchange and access to information, can act as a barrier when carrying out collaborations within the natural resource management and forestry sector (Cohen, Evans & Mills, 2012; Dubay et al., 2013; Moote & Becker, 2003).

In regards to enabling factors for collaboratively governing natural resources, the literature has proved relatively fruitless. This is with the exception however of (open and transparent) communication being highlighted as an important factor in itself but also as a means of overcoming possible barriers (Dubay et al., 2013). However, as collaborations are demanding in terms of engagement and interaction, communication processes can often be stifled (Cohen, Evans & Mills, 2012; Daniels & Walker, 2001; as cited in Dubay et al 2013). Additionally, due to literature on both collaborative natural resource management and cross-sector collaborations mentioning this factor as important, we have chosen to only include ‘communication’ under the “present in cross-sector collaborations” heading in the table in the following section.

2.1.4 Summary of factors

In order to get an understanding for which the most notable factors in literature are, we have compiled these factors in the table on the next page. The table is descriptive in its nature, and provides an indication for which factors impact cross-sector collaboration most remarkably, and will be later used when comparing our findings in relation to previous literature.

Hindering factors

Characteristics

Cited in

Past experiences Lack of experience,Negative experience,

Negative perception of partners

Collins & Gerlach, 2019; Cairns & Harris, 2011; Selin & Chavez, 1995 Lack of resources Financial,

Technological, Conceptual

Calliari et al., 2019 Institutional Barriers Horizontal and vertical coordination,

Institutional culture

Biesbroek et al., 2013; Selin & Chavez, 1995

Logistical challenges Geographically disperse partners Babiak & Thibault, 2009; Klenk & Hickey, 2013

Power imbalances Babiak & Thibault, 2019; Gray, 1989; Selin & Chavez, 1995

Competing interests Rode et al., 2016; Lienhoop & Schröter-Schlaack, 2018 Varying visions of management Näyhä & Pesonen 2014; Guerrero

& Hansen, 2018 Lack of coordination Vertically and horizontally dispersed

partners

Plieninger et al., 2012; Wüstemann et al., 2017; Lienhoop & Schröter-Schlaack, 2018

Stakeholder histories Conflict, cultural barriers, lack of experience with collaborating

Dubay et al., 2013

Resistance to change Näyhä & Pesonen 2014; Guerrero & Hansen, 2018

Rigid governmental policies and procedures

Moote & Becker, 2003 Lack of adequate and reliable

resources In supporting operations Cohen, Evans & Mills, 2012; Dubay et al., 2013; Moote & Becker, 2003

Enabling factors

Characteristics

Cited in

Establishing a shared vision Collective problem formulation, Decide on explicit norms, management processes and practical aspects

Bryson, Crosby, Stone, 2006; Gray & Stites, 2013

Effective conflict-management Consensus-based decision making Gray & Stites, 2013 Leadership Traits: Supportive, committed, inclusive,

non-bias, problem-solver, capacity to overview the process, good at securing resources

Bryson, Crosby, & Stone, 2015; Emerson et al., 2012; Gray & Stites, 2013

Collective leadership Non-stagnant, adaptive, Ansell & Gash, 2008; Gray, 2008

Trust in partners Ought to be continuous,

Outcome of relations and experiences

Bryson, Crosby, & Stone, 2006; Babiak & Thibault, 2019; Collins & Gerlach, 2019; Gray & Stites, 2013; Heuer, 2011

Stakeholder relations/Legitimacy Fostering trust and ensuring legitimacy within stakeholder relations

Transparent and well-functioning communication

Formulating ‘authoritative texts’, Face-to-face interaction

Ansell and Gash 2008; Babiak & Thibault, 2009; Bryson, Crosby and Stone, 2015; Dubay et al., 2013; Koschmann, Kuhn & Pfarrer, 2012; Romzek, LeRoux, & Blackmar 2012 Favourable competencies and

capabilities among partners openness to collaborating, interpersonal understanding, will to achieve a common good, ability to analyse and involve stakeholders, plan strategically, participate in teams across boundaries

Bryson, Crosby & Stone, 2015; Getha & Taylor, 2008

Table 1. Hindering and enabling factors present in cross-sector collaborations and collaborative natural resource

management and forestry

Pr es en t i n cr os s-se ct or co lla bo ra ti on s Pr es en t i n co lla bo ra ti ve n at ur al re so urc e m an ag em en t a nd fo re st ry Pr es en t i n cr os s-se ct or c ol la bo ra ti on s

2.2 Theoretical framework

There are multiple research challenges associated with studying cross-sector collaborations as it demands integrating perspectives from various disciplines (Bryson, Crosby & Stone, 2006). In order to respond to these challenges and provide a holistic explanation of which factors impact cross-sector collaborations most remarkably in this specific setting, and provide a description of how they interrelate, we found aspects of systems theory being the most suitable approach to apply. This is because systems theory provides useful insights into how elements in a system are connected, where the researchers are able to position themselves in a way that enables them to see both the trees and the forest, i.e. both the parts and the whole (Arnold & Wade, 2015). It also draws attention to the more specific dynamics of the relationships existing between the different elements and is applicable to multiple research areas due its broad nature (Checkland, 1999; Cabrera, Colosi & Lobdell, 2008). Therefore, it is considered a meta-discipline suitable in analysing the subject matter in multiple fields (Laszlo & Krippner, 1998; Checkland, 1999). Based on this premise, we found system theory the most suitable when developing a grounded theory that explains the interrelations between factors present in ecosystem service governance in a cross-collaborative setting.

However, there are some aspects that need to be addressed before going into depth about the theory and its constituents. Firstly, most system theorists discuss the elements within a particular system in relation to concrete patterns of behaviours that characterise the event (Kirkwood, 2013), whereas we intend to discuss the elements in relation to more general factors, thus making it difficult to fully utilise the concepts within systems thinking. Additionally, the factors highlighted in this paper are much more abstract and centred around general concepts in comparison to when studying more specific events within an organisational process for instance. In order to employ systems theory in the most credible way, these insights will be kept in mind when adopting the approach, where we will not utilise aspects within systems theory that are simply not applicable to our research.

2.2.1 Systems theory and systems thinking

As previously described, systems theory enables a better understanding of complex systems and helps to provide a holistic view of the elements in a system and insights in how they interact. Adopting this understanding allows for a broader perspective of the area of concern to be taken into account, and increases the understanding for cause and effect relationships that are often less straightforward than one might intuitively think (Manuele, 2019). The approach additionally stands in opposition to reductionism, which tries to describe phenomena simply by reducing the system into parts, and then analysing these parts without looking at their relation with each other. However, complex issues are much more unpredictable and non-linear than traditional, reductionist theories can account for (Hjorth & Bagheri, 2006).

One way to concretise systems theory, which thus far has only been described in vague terms, is to elaborate on the concept of systems thinking, which is an analytical tool used to analyse systems. Cabrera et al. (2008, 2015) propose four conceptual components for systems thinking which are applicable to any field or context. These four components are Distinctions, Systems, Relationships and Perspectives (DSRP), with their most basic attributes explained in the following description;

“Distinctions can be made between and among things and ideas; things and ideas can be organized into systems, in which both the parts and the wholes can be identified; relationships can be made between and among things and ideas; and lastly, things and ideas can be viewed from the perspectives of other people, things, and ideas” (Cabrera, Cabrera & Powers, 2015, p. 535).

This definition of systems thinking includes all elements most commonly discussed in literature, as the most recognised definitions tends to include the understanding of dynamic behaviour, interconnections, systems structure as an effect of those interconnections, and the premise of viewing systems as a whole rather than parts (Arnold & Wade, 2015). However, this explanation is still quite vague. Arnold and Wade (2015) argue that this description simplifies systems thinking too much, thus being reductionist in its nature. Therefore, the authors conclude the following definition, using more of a systems approach when defining systems thinking; “Systems thinking is a set of synergistic analytic skills used to improve the capability of identifying and understanding systems, predicting their behaviours, and devising modifications to them in order to produce desired effects” (p. 675). The analytical skills mentioned in this definition can be further explained in terms of its constituent elements, shown in the table below.

1

Recognising Interconnections2

Identifying and Understanding Feedback3

Understanding System Structure4

Differentiating Types of Stocks, Flows, Variables5

Identifying and Understanding Non-Linear relationships6

Understanding Dynamic Behavior7

Reducing Complexity by Modeling Systems Conceptually8

Understanding Systems at Different ScalesTable 2: Eight elements of systems thinking. Based on Arnold and Wade (2015)

This definition and its associated elements synthesise the most commonly discussed attributes in literature while simultaneously including a broad and multifaceted interpretation of systems thinking (Arnold & Wade, 2015). Hence, it can be used when analysing systems thinking in relation to multiple different disciplines. Thus, it will be utilised when analysing the interconnectivity of factors present in cross-sector collaborations around ecosystem service governance.

2.2.2 System dynamics and causal loop diagrams

One branch within systems theory is system dynamics, which has the goal of enhancing our understanding of a complex system through applying a whole-system approach (Hjorth & Bagheri, 2015). The interest for the concept has been growing steadily during the last couple of years as it pays attention to complexity and nonlinearity which are inherent in any social system (Forrester, 1994). Therefore, it provides useful insights into how a complex system operates, and the feedback processes existing within it.

In order to understand these processes, causal loop diagrams (CLDs) are recommended to use (Sterman, 2000; Hjorth & Bagheri, 2015). A CLD is a graphic tool which helps to visualise the most important relationships that exist between different constituents of a system and how they interact with one another, thus helping to move away from linear cause and effect relationships to a more circular one (Hjorth & Bagheri, 2015). These diagrams both describe the variables in text format and the relationship that exists between them with the use of arrows. All in all, CLD triggers a learning process which will help in modifying our mental models of the world, which in turn enables us to improve system performance (Hjorth & Bagheri, 2015). Therefore, this tool will be used when visualising the interconnectivity between the most important factors found in our study, and when depicting different feedback loops, i.e the causal relationships existing between factors (Kirkwood, 2013). In our case, however, depending on whether the factors within the collaborative system are managed in an enabling or hindering way, they will affect each other differently. Therefore, we will not be able to depict so-called reinforcing loops and balancing loops (thus not described in this chapter), since these loops are dependent on the characteristics of the factors, i.e being either positive or negative.

3. Method

This chapter provides an overview of the methods used in this research and the methodological considerations behind this reasoning.

3.1 Research approach

The main objective of this research is to gain an understanding for which factors enable or hinder the successful governance of ecosystem services in a cross-collaborative setting. As the research is conducted within a new area of inquiry, where the goal is to generate an initial explanation of the studied phenomenon, this paper is to be seen as exploratory in its nature (Bhattacherjee, 2012). Additionally, as the research problem has not been looked at before, we are applying aspects of an inductive form of reasoning known as grounded theory. This implies that we inductively develop theoretical analyses from the collected data, absent of a pre-constructed hypothesis to guide our paper (Silverman, 2015). Therefore, we have simultaneously engaged in data collection and data analysis during the research process in order to fulfil the purpose of this paper as comprehensively as possible.

Furthermore, as we are seeking to understand the perceptions, experiences and assumptions of actors present a particular setting, we have chosen to use a qualitative approach when gathering data. This is because the approach facilitates obtaining in-depth and detailed information on how, when and why a given phenomenon arises (Bryman & Bell, 2015) which our study intends to investigate.

3.2 Research design

3.2.1 Case oriented research

In order to gain an understanding for which factors drive or inhibit the successful governance of ecosystem services in a cross-collaborative setting, a case based research design has been applied. This design was chosen because it allows for a greater understanding of the system in which the collaboration takes place, which is beneficial when looking at how the different enabling and hindering factors interact with one another (Yin, 2012). Additionally, case oriented studies have been proven useful when investigating collaborative processes (Austin, 2000). This is because it may offer useful insights on how the different phases and nuances of the collaboration are managed, which depending on this management, can either lead to a collaboration's success or ultimately its demise. (Dubay et al., 2013). It is further relevant when analysing complex social phenomenons from various perspectives (6 & Bellamy, 2012; Silverman, 2015) and is central to the development of grounded theory (Glauser & Strauss, 1967; as cited in Silverman, 2015).

In this study, we have decided to incorporate multiple cases. The choice was based on the premise that we intend to not only look at perspectives within one specific case, but also have the ability to analyse these perspectives from a broad variety of contexts in order to provide a holistic understanding for the studied issue. Additionally, since the goal of our research in relation to our first research question is to be made generalisable within a specific collaborative-context, we found multiple cases being relevant to look at as we were able to obtain information from several actors present in various settings. This

will contribute to the collection of more nuanced data, making it easier to be made applicable to similar events and contexts.

3.2.2 Case Characteristics

In order to incorporate multiple perspectives, we have included four cases in this study. These cases (or projects as they are referred to within the cases themselves) belong to two different initiatives which are funded by the EU under the Horizon 2020 programme. The objective of both initiatives is to apply innovative measures to support the provision of various forest ecosystem services. Since many of these services have no direct market value, policy and economic incentives are needed in order for the forest owners and managers to continue to support these services. This is achieved by bringing together a wide variety of actors from the forest-management, policy, tourism, university and business sector, that work together to stimulate innovations for the sustainable supply and financing of forest ecosystem services. Hence, the different cases collaborate across sectors and employ a multi-actor approach when innovating for sustainability. Thus, we found these cases from within these two initiatives to be suitable to look at for this research.

Additionally, the cases are at the very end of their project life-cycle, meaning that the different parties within each case have collaborated for a satisfactory amount of time (an average of 2,5 years). This has enabled us to obtain more ‘lessons learnt’ insights which is beneficial when studying factors that either drive or inhibit a successful cross-sector collaboration, as it is difficult to know what effect factors have in the initial stage of a project. Lastly, the projects serve as good case studies for scientific analysis since they all have a close interaction with both research and practice, due to the main partners within the collaboration being from research and practice. In order to provide a better understanding for what the collaborative constellation looks like, we have visualised the initiatives and the collaboration that takes place within the different cases, in the figure below.

The blue circles represent the cases chosen for this study, and the triangular illustration below represents the interaction that takes place between the science partners, practice partners and stakeholders. In relation to this dynamic, it should be further clarified that the sectors which the practice partners and stakeholders stem from will differ depending on the case. This is due to the projects using different courses of action when governing ecosystem services, thus demanding input from different sectors of society. Further information regarding the partners involved can be found in each case description.

3.2.3 Selection and delimitation

We purposely chose which cases within the two initiatives to include in this study, as we wanted to look at cases where cross-sector collaboration around ecosystem services was particularly significant. In order to achieve this successfully, we analysed the 17 different cases available on the websites and scored them from 1-10 depending on how integratively they worked with governing ecosystem services and to what extent they used a multi-actor and cross-collaborative approach when innovating for the sustainable supply of ecosystem services. After this step, we contacted seven of the cases, which all had received a score of seven or higher, and asked them to answer the following questions; Is it a

cross-sectoral collaboration, and if so, which sectors are involved? Are decisions about the project generally made collaboratively or centrally? Do those involved have shared goals about the outcomes of the initiative? The answers we received during this phase enabled us to choose three cases where

cross-sector collaboration around ecosystem service governance was especially evident. However, we noticed that it was difficult to get enough respondents from these cases, which would have resulted in an insufficient amount of data. Therefore, we reached out to another high ranking case in order to achieve data saturation. In regards to this selection, it can be argued that conducting a purposive sampling has been beneficial from the perspective of developing a grounded theory (Silverman, 2015), as we were able to actively choose those cases most relevant for our study, and if of relevance, add more until a sufficient amount of data was gathered.

3.2.4 Case descriptions

The following case descriptions are based on the information available on the websites, the personal interviews that were conducted and additional documents that were sent to us by the participants.

Austrian case

The initiative in Austria is a collaboration between a local university (research partner) and a non-profit organisation (practice partner) working at the interface of research and practical implementation. The case is focused on capturing and increasing the value added from forests in the mountainous and densely-forested region in central Austria. This goal is realised through addressing new markets with attractive concepts with a specific focus on improving the value chain of forest and wood-related resources. In particular, products made from timber and other materials captured from forests are to be created by local carpenters and designers. All in all, this is expected to secure local artisanship, increase the sales of locally sourced products, increase job-opportunities, lead to a more sustainable forest management and enhance the collaboration between stakeholders in the forestry sector. These stakeholders amount to 160 different actors, who belong to the categories of public administration, forest owners, municipalities, corporation networks, Small Medium Enterprises (SMEs), forest federations and regional development agencies. As understood, many regional actors from different

sectors of society are considered to be important for realizing this initiative and for creating benefits for the region.

Italian case

The Italian case is mainly a collaboration between a local university (research partner) and the public administrations office (practice partner). This project is focused on pursuing an active, balanced and integrated management of forest-pasture systems in the mountainous area located in northern Italy, with the aim of preventing the abandonment of the mountain area while simultaneously ensuring a sustainable supply of various forest-pasture functions. This demands that the region adopts a close-to-nature silviculture approach where production levels are kept constant over time, allowing for the forest to regenerate and provide non-financial ecosystem services. Furthermore, as part of the pasture management, it requires the continuous breeding of livestock in order to sustain production activities related to mountain grazing. A combination of these efforts is believed to support a balanced coexistence of forest areas, meadows and pasture so that they can keep providing a wide array of ecosystem services. In order for this to be successful, the project takes input from various stakeholders, including SMEs, tourist agencies and land owners.

Danish case

This case is a collaboration between a university in Denmark (research partner) and the Danish Forestry Association (practice partner). The focus lays on protecting and maintaining forest biodiversity in a cost effective way by implementing reverse auctions payment schemes. In practice, this means that sellers (forest owners) bid for the prices at which they are willing to sell their goods and services. The difference with a reversed auction is that the seller with the lowest price wins as opposed to a regular auction where buyers bid the highest price for goods or services (Chen, 2019). The majority of forests in Denmark are privately owned and managed making owner involvement in biodiversity conservation imperative. Additionally, biodiversity conservation in Denmark requires both public and private engagement, where this initiative aims towards sparking the interest from both of these sectors through the creation of new and innovative public grant schemes. In order for this project to be successful, the case takes input from forest owners and biodiversity experts, who are the main stakeholders in this case.

Czech Republic case

The Czech case centres around a collaboration between the Land Trust Association which is an NGO (practice partner), The Institute for Structural Policy (practice partner) and a local University who acts as the research partner. The stakeholders are mainly forest owners, hunters as well as other local actors. Stakeholder relations and engagement have been inherently complex in this region, namely due to conflicting interests between hunter stakeholder groups calling for the free movement of game and the NGO seeking to protect forest biodiversity and ecosystem services. The case is characterised by self-organisation and management of collectively owned forest and explores new forms and practices of collective governance while seeking to develop new payment schemes for protecting biodiversity and the provision of forest ecosystem services, with the broader goal of developing more sustainable practices and management in forestry.

3.3 Data Collection

3.3.1 Semi-structured interviews

Our data was collected through semi-structured interviews, as we wanted to understand the perceived factors which affect cross-sector collaborations around ecosystem services. This method is appropriate to use when trying to obtain in-depth and detailed information about how, when and why something occurs (Bryman & Bell, 2015). It also enables the researchers to divert from the previously constructed interview question if opinions and viewpoints of the respondent are thought to be more suitably elaborated on with a different question (Gray, 2014). Hence, it allows for a greater flexibility and allows better access to the respondents views, opinions, experiences, understandings and interpretation of events (Silverman, 2015).

In total, we conducted 11 interviews with representatives from the different cases. Some were selected through purposive sampling, and others through the snowball effect, as it was difficult to get the contact information to all of those involved in the different cases. In regards to ethical considerations, the participants filled in a consent form confirming that they were informed about the confidentiality of their responses and that they could withdraw from answering certain questions if they wished. Furthermore, before the interviews were conducted, a pilot interview was held with an experienced researcher, where his feedback contributed to a few adjustments of the interview guide being made. In total, 14 carefully selected questions were prepared, with the intention of being delivered in a pre-decided order. Additionally, 8 sub-questions were prepared in case the interviewee would not satisfactorily answer the main question. The interview guide with questions are to be found in the appendix. The interviews took between 30 to 70 minutes and were held through Skype due to the geographic distance to the respondents. We are aware of the interview format being digital can be problematic in the sense that it can affect the richness of the interaction (Rowley, 2012). However, it can also contribute to removing some potential interviewer bias (Bryman, 2001, as cited in Rowley, 2012).

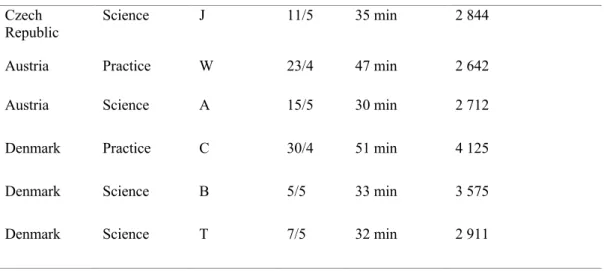

In order to get an overview of the interviews and participants, we have compiled the most important information in the table below.

Case Form of partner

Coding name

Date Duration Number of

transcribed words

Italy Practice F 28/4 1 h 7 min 3 803

Italy Practice C 30/4 39 min 2 695

Italy Practice L 7/5 35 min 2 810

Italy Science E 8/5 36 min 3 070

Czech

Czech

Republic Science J 11/5 35 min 2 844

Austria Practice W 23/4 47 min 2 642

Austria Science A 15/5 30 min 2 712

Denmark Practice C 30/4 51 min 4 125

Denmark Science B 5/5 33 min 3 575

Denmark Science T 7/5 32 min 2 911

Table 3. Overview of the respondents.

3.3.2 Data analysis and Coding strategy

When analysing the collected data, we started the process with transcribing all of the interviews with the help of the online application ‘Otter’. Thereafter, we highlighted words and sentences in the interview transcriptions that we found relevant for our research question. These words and sentences were highlighted with different colours depending on if they related to enabling factors, hindering factors, overcoming challenges and lastly, if they had effects on any other factors. These ranged from being very descriptive to highly conceptual. After having done this, we summarised the sentences with one to two words, with the aim of identifying commonalities between the different interviews and get a better overall view of the received information. We then categorised these words under different themes, known as thematic content analysis, in order to identify recurring themes in the data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). These were kept to 14 as having too many themes makes the analysis difficult to conduct (Rowley, 2012). Six of these themes were related to barriers and eight of them were related to drivers. The last step was to structure our data in accordance with the identified themes. Thereby, we created a table and pasted all of the highlighted sentences in depending on the theme they belonged to. This enabled us to get a cohesive understanding of the empirical findings and minimised the risk of us missing valuable information. Thereafter, we summarised the main findings, being mindful of our subjective interpretations. This step we later refer to as ‘empirical findings’ and was done at the end of the research process. However, the analysis of data in relation to theory was done simultaneously with the data gathering process, as we made the methodological choice to induce theory gathered from data.

3.4 Limitations

In regards to the scope of the study, some limitations need to be acknowledged. Since the study was carried out during a two month period, it was not favourable to use multiple methods and triangulate data. The usage of triangulation might have resulted in a more thorough understanding of the enabling and hindering factors present in this specific collaborative setting, where the utilisation of observations could have complemented our findings in an interesting way and given us the opportunity to analyse the collaborative process more profoundly. However, as Hammersley and Atkinson point out “...one should not adopt a naively optimistic view that the aggregation of data from different sources will

unproblematically add up to produce a more complete picture” (1995, p. 199; As cited in Silverman, 2015).

The limited amount of time also affected the number of interviews we were able to conduct, as we simply had to prioritise other aspects of our paper. More interviews might have resulted in additional interesting findings. However, we are under the impression that these 11 interviews were fruitful enough to draw valid and reliable conclusions about the posed research questions, since the interviewees operated in different contexts and had different roles, thus ensuring representation.

The interviews were also conducted in English which might have affected the richness of the data since none of the respondents were native English speakers. However, since almost all of them were used to collaborating internationally and having English as a working language, most were proficient in their language skills. Therefore, the risk of the research results being affected by miscommunication and misunderstandings was considered unproblematic.

3.5 Validity and reliability

Regarding the concept of validity, there is always a risk of research (particularly qualitative research) being subjective, where expectations and preconceptions influence the interpretation of the gathered information (Bryman & Bell, 2015; Dalen, 2008). In order to minimise this risk, we avoided previous literature and subjective views to guide the interview questions. Instead, we posed general questions and subsequently allowed the interviewees to elaborate freely on their own thoughts and experiences. In order to ensure that our own interpretations and statements were in accordance with the truth, which is an imperative aspect when ensuring validity (6 & Bellamy, 2012), we decided to cross-check our interpretation of the data between each other. This meant that we never worked separately with coding and analysing the interviews. Instead we made sure to switch transcriptions between us in order to ensure that we interpreted the data consistently. If these interpretations were dissimilar, we critically discussed the findings in order to guarantee that our coding-strategy and interpretations were consistent. All in all, this procedure known as ‘interjudge reliability’ contributed to reducing some potential researcher bias and improved the reliability of our study (Gray, 2014).

In regards to external validity, i.e. whether or not the conclusions of this study is applicable in other contexts, we are of the opinion that our findings answering our first research questions will be able to be generalised across similar situations where cross-sector collaborations around ecosystem services is evident. This is because we ensured representation among different actors involved in the cases and gathered a sufficient amount of data for inferring credible conclusions on enabling and hindering factors apparent in this setting. However, the findings answering our second research questions cannot be generalised, since the interrelations between factors vary across systems when investigating complex interconnections (Chowdhurry, 2019).

Lastly, in order to ensure quality control, consideration was given to the ‘interview effect’, which is at risk when interviews are not conducted consistently. All 11 interviews were conducted jointly, however we each took turns in leading the interview where the other took notes, supported and prompted if needed. We made sure to keep a neutral and open tone as well as afford ample time for participants to gather thoughts and answer the questions. Considering these measures reduces the risk of influencing or affecting participants' responses (Gray, 2014).

4. Empirical findings

In this section we display our empirical findings. We have extracted the most relevant findings in relation to our research questions and additionally provided context and meaning, in order to further illustrate the experiences of the participants. Participants who provide empirical data are referred to by their first initial, either indirectly or directly through quotes. In order to answer our research questions, we have structured our findings into hindering and enabling factors with correlating empirical data supporting each categorisation. Additionally, it is evident from analysing our empirical material that some factors can be experienced as both enabling or hindering depending on how the factors are managed and subsequently experienced. In order to accurately represent the participants' experiences and perceptions, we have allowed these factors to fall under both categories. Lastly, participants provided insights on how to overcome these challenges, which could be useful and practical for similar collaborative constellations.

4.1 Summary of factors

Below is a descriptive overview of the main factors which enable or hinder the successful cross-sector collaboration when governing ecosystem services. In addition to including the different factors and the overarching categories in which they fall under, there is additional information regarding how these factors impact other aspects. These impacts or “effects” as they are referred to in the table, are later used when showcasing how the different factors interrelate with each other. Some categories do not have a more specific sub-category and are therefore left without any further description. Furthermore, the factors which became evident after conducting our analysis and were not present in the literature review are in bold.

Hindering factors Effects

Enabling factors Effects

Organisational Administrative duties Decreases motivation Project design (user

friendly, collaborative) Enables knowledge sharing & learning Resources (time, knowledge, human) Decreases engagement of partners & stakeholders

Resources (time, human capital, knowledge

Able to thoroughly carry out activities Top-down governance

structure

Decreases engagement of stakeholders

Intermediate position Limiting coordination

opportunities

Unstable management Time consuming

Engagement Other work priorities Less time to engage in

the project External engagement Fosters better internal engagement Historical relationships Effects

stakeholder-engagement negatively

Internal engagement Creates legitimacy & recognition Communication Difficult to find a

common language Creates a diverse understanding of the issue at hand

In-person

communication Increases trust, enables stakeholder discussions & helps resolve conflict

Miscommunication Effects relationships

negatively Workshops, meetings Facilitates discussion, generates idea- & knowledge- sharing Non-functioning

communication Creates difficulties in carrying out the work

Cultural Differing cultures Makes international

& interpersonal cooperation challenging Culture of collaboration & cooperative democracy Facilitates collaboration Differing

working-cultures Creates communication issues History of stakeholder engagement Facilitates collaboration

Relational Historical events Influences the ability

to reach out to stakeholders, impairs knowledge sharing, creates uncertainty about the future

Established Network Builds relations,

enables communication

Differing objectives Partners work

towards different goals

Unforeseen

external events Storm & COVID-19 Effects in-person communication &

engagement negatively

Leadership Active, competent,

charisma, self-drive, missionary attitude Improves communication & engagement Key actor in

network building Connections & insights from before Enables knowledge sharing, strengthens

communication & improves engagement

Table 4.Summary of factors that enable or hinder the successful governance of ecosystem services in a cross-collaborative setting

4.2 Hindering factors

Organisational factors

Since the projects are initiated by a larger governing body (the EU) some respondents experienced administrative challenges (T, C) and that the operations can at times feel “...very boxed and a bit cumbersome” (C). Administrative requirements such as additional reporting and documentation is not only time-consuming, which can affect the collaborative aspects of the project not receiving as much attention, but it also impacts the motivation to carry out similar projects in the future (C). Additionally, this type of governance structure where institutional actors play a major role, often entails a top-down management approach which has resulted in regional stakeholders not being very involved in developing strategies and identifying goals for the project (E). In order to carry out the projects successfully and realise a fruitful cross-sector collaboration, this top-down approach might have to be compromised. Instead, a horizontal form of governance would be more advantageous to implement when aiming to proactively engage stakeholders (E).

Another aspect related to organisational challenges is whether or not the organisation partaking in the collaboration has the authority to coordinate with the partners in an efficient way. For instance, J stated that the organisation he belongs to are only intermediaries between forest owners and the project consortium, where he has to deal with activities with the partners and the forest owners separately. “This is quite challenging” he explained, where this is mainly a result of the forest owners not being able to speak English. J also mentioned another factor relating to the issue of management, which was that one of the main partners in the collaboration changes directors constantly. This is an issue, since it is very time-consuming having to explain the project multiple times and build new relationships constantly (J). According to K, having limited resources is also problematic from a collaborative point of view, since it hinders her to successfully engage in the project. She explained that herself and her colleagues are constantly provided with new tasks, issues and goals “...but the old work stays the same”, which makes it difficult to fully engage in the project “...as the time is fixed”. Being overloaded with tasks was also mentioned in relation to stakeholders, where the respondents from the Italian case explained that there already are a lot of similar initiatives in place in the valley. This has affected the stakeholders willingness to engage in the project, where instead of initiating a new project it would have been beneficial to invest that same amount of time and money in improving the coordination between stakeholders within existing projects (F).

Lastly, F highlighted the resource aspect of knowledge, where her organisation was not “...knowledgeable enough on participatory processes” which might have hindered the work of bringing together multiple stakeholders from different sectors. In order to overcome this difficulty, it would have been beneficial to receive more information on how other innovation regions were working with participatory processes and workshops, in order to draw inspiration from other networks. This aspect was also highlighted by A which stated that “The exchange of ideas and experiences is a great challenge for all research/practice projects” where gaining insights from other regions is necessary in these types of collaborative projects.