EDUCARE

E D U C A R E V E T E N S K A P L I G A S K R I F T E R

•

Discursive Tensions on the Landscape of Modern Childhood

Patrick J. Ryan

•

Dokumentation, styrning och kontroll i den svenska skolan

Lisa Asp-Onsjö

•

“Soft governance” i förskolans utvecklingssamtal

Ann-Marie Markström

•

En skolas implementering av kamratmedling

Ingela Kolfjord

•

Social mobilization or street crimes: Two strategies among young

urban outcasts in contemporary Sweden

Philip Lalander & Ove Sernhede

•

Vem är egentligen expert? Hiphop som utbildningspolitik

och progressiv pedagogik i USA

Johan Söderman

Lärande och samhälle, Malmö högskola ISBN: 978-91-7104-413-6, ISSN: 1653-1868 2011: 2 Tema: Välfärdsstat i omvandling: reglerad barndom – oregerlig ungdom?

EDUC ARE - VETENSKAPLIG A SKRIFTER 20 20 1 1:2 T EMA : V ä LF ä RDSS T A T I o MV ANDLIN G

E D U C A R E V E T E N S K A P L I G A S K R I F T E R

2011:2 Tema: Välfärdsstat i omvandling:

reglerad barndom – oregerlig ungdom?

Lärande och samhälle, Malmö högskolaEDUCARE

Educare är latin och betyder närmast ”ta sig an” eller ”ha omsorg för”. Educare är

EDUCARE - Vetenskapliga skrifter är en sakkunniggranskad skriftserie som ges ut vid fakulteten för Lärande och samhälle i Malmö sedan hösten 2005. Den speglar och artikulerar den mångfald av ämnen och forskningsinrikt-ningar som finns inom utbildningsvetenskap i Malmö. EDUCARE är också ett nationellt och nordiskt forum där nyare forskning, aktuella perspektiv på utbildningsvetenskapens ämnen samt utvecklingsarbeten med ett teoretiskt fundament ges plats. Utgivning består av vetenskapliga artiklar. EDUCARE vänder sig till forskare vid lärarutbildningar, studenter vid lärarutbildningar, intresserade lärare vid högskolor, universitet och i det allmänna skolväsendet samt utbildningsplanerare.

Författarinstruktion och call for papers finns på EDUCARE:s hemsida:

http://www.mah.se/fakulteter-och-omraden/Lararutbildningen/Nyheter/ Publikationer/EDUCARE--Vetenskapliga-tidskrifter/

Redaktion: Lotta Bergman (huvudredaktör), Ingegerd Ericsson,

Copyright Författarna och Malmö högskola EDUCARE 2011:2 Tema: Välfärdstat i omvandling: reglerad barndom – oregerlig ungdom?

Titeln ingår i serien EDUCARE, publicerad vid Lärande och samhälle, Malmö högskola.

Tryck: Holmbergs AB, Malmö, 2011 ISBN: 978-91-7104-413-6 ISSN: 1653-1868 Beställningsadress: www.mah.se/muep Holmbergs AB Box 25 201 20 Malmö Tel. 040-6606660 Fax 040-6606670 Epost: info@holmbergs.com

Innehåll

Förord ... 7

Ove Sernhede & Ingegerd Tallberg Broman

Discursive Tensions on the Landscape of Modern Childhood .... 11

Patrick J. Ryan

Dokumentation, styrning och kontroll i den svenska skolan ... 39

Lisa Asp-Onsjö

“Soft governance” i förskolans utvecklingssamtal ... 57

Ann-Marie Markström

En skolas implementering av kamratmedling ... 77

Ingela Kolfjord

Social mobilization or street crimes: Two strategies among young urban outcasts in contemporary Sweden ... 99

Philip Lalander & Ove Sernhede

Vem är egentligen expert? Hiphop som utbildningspolitik

och progressiv pedagogik i USA ... 123

Förord

De senaste två decennierna har inneburit avgörande förändringar av det svenska samhället. Den medieteknologiska utvecklingen, migration, globali-sering och marknadsanpassning av välfärdens institutioner innebär stora förändringar för barns och ungas villkor och för förhållandet mellan vuxna och barn/ungdomar. Den offentliga sektorns minskade utrymme, det fria skolvalet, ökade inkomstklyftor och boendesegregation har format ett sam-hälle där barn och unga lever i skilda världar. De professionella uppdragen inom exempelvis skola och socialtjänst innefattar ökade krav på effektivitet och kontroll, samtidigt som barns, ungas och föräldrars egenansvar och självstyrning betonas allt mer. En ny form av utsatthet bland barn och unga har diskuteras. Den svenska välfärdsstaten byggde, under de expansiva de-cennierna efter andra världskriget, på en ambition att formulera kollektiva mål för samhällsutvecklingen. Utvecklingsmönstren i dagens avreglerade, post-industriella samhälle sätter individen och det enskilda entreprenörskapet framför det gemensamma projektet.

Mot denna bakgrund ställde sig Malmö högskola uppgiften att hitta former för att låta forskningen om barndom och ungdom och barns och ungas vill-kor möta de krav som måste ställas på en samtidsorienterad professionsut-bildning. Den satsning som ägde rum och som startade 2008 med etableran-det av nätverket Barndom och ungdom i förändring (BUiF) har för avsikt att låta de vetenskapliga kunskapshorisonter som utvecklats inom olika discipli-ner brytas mot varandra för att utveckla den gränsöverskridande handlings-kompetens, inom såväl forskning som undervisning, som är kännetecknet för Malmö högskola.

Nätverket representerar en rad olika discipliner och forskarna har olika in-tressen och ingångar. Begrepp som kön, klass, generation, etnicitet, religion och sexualitet är återkommande i diskussionerna. Under den inledande iden-tifierings- och etableringsfasen identifierades ett antal forskningsgruppering-ar som tillsammans utgjorde en första beskrivning av den profil som kforskningsgruppering-arakte- karakte-riserar temat just vid Malmö Högskola. Som ett led i att stärka nätverket lokalt arrangerades under 2009 och 2010 en rad seminarier och föreläsning-ar.

8

Frånvaron av ett nationellt forum kring forskning och professionsfrågor om barns- och ungas villkor i det samtida Sverige föranledde BUiF att hösten 2010 arrangera en konferens på temat Barndom och Ungdom i förändring.

Välfärdsstat i omvandling: reglerad barndom – oregerlig ungdom?

Till konferensen, som besöktes av ett 100-tal deltagare från de nordiska län-derna, hade tre internationellt ledande forskare bjudits in som keynote spea-kers; Allison James, professor från University of Sheffield, Centre for the Study of Childhood and Youth, Claire Alexander, professor från London School of Economics och Patrick Ryan, Associate Professor of Childhood and Social Institution, Kings University College, University of Western On-tario.

Texterna i detta nummer av Educare har alla sitt ursprung i konferensen och bygger på presentationer som gjordes dessa dagar. Konferensen var organi-serad i fyra teman, som gemensamt uttrycker nätverkets inriktning. Dessa var ”Dokumentation, bedömning och normerande praktiker”, ”Globala ge-menskaper”, ”Barns och Ungas aktörsskap: rättigheter och ansvar” samt ”Kultur och lärande”. De texter som ingår i detta nummer fördelar sig över samtliga tema.

Först ut i detta temanummer från konferensen är vår keynote speaker Patrick

Ryan från Kings University College Kanada, som utvecklar sitt

inlednings-anförande i bidraget med titeln: ”Discursive Tensions on the Landscape of

Modern Childhood.” Ryan lyfter en diskussion om den moderna barndomen

som en produkt av diskursiva spänningar mellan fyra dominerande tankefi-gurer, det villkorade betingade barnet, (kopplad till begreppet socialisation) det autentiska (romantik), det utvecklingsmässiga (positiv vetenskap) och det politiska barnet (kompetent aktörskap). Ryan framhåller hur dessa verkat över flera århundraden med ömsesidig påverkan på varandra och hur de syn-liggör den ideologiska dynamiken bakom en rad organisatoriska, rättsliga och institutionella inrättningar och åtgärder, som han rikligt exemplifierar, som gäller barn och barndom.

Lisa Asp-Onsjö är lektor vid Institutionen för didaktik och pedagogisk

pro-fession, Göteborgs universitet. Hennes bidrag i denna volym,

Dokumenta-tion, styrning och kontroll i den svenska skolan, är en vidareutveckling av

mot relationen mellan skolans dokumentation och dess konsekvenser för skolans kunskapssyn, ett annat tema rör relationen mellan skolans interna dokumentation och den i samhället allt påtagligare och allt mer styrande dokumentationskultur, som Lisa Asp-Onsjö, i samklang med samtida social-filosofi, diskuterar i termer av dokumentalitet.

Ann-Marie Markström är lektor i pedagogiskt arbete och forskarassistent i

utbildningsvetenskap på Institutionen för samhälls- och välfärdsstudier vid Linköpings universitet. Hennes artikel ”Soft governance” i förskolans

ut-vecklingssamtal” behandlar det sedan 1970-talet praktiserade, och sedan

1998 obligatoriska, utvecklingssamtalet i förskolan. Trots dess starka och institutionaliserade ställning i förskolans praktik, är området mycket lite utforskat. Markström diskuterar i sitt bidrag utvecklingssamtalet utifrån ett empiriskt material och med perspektiv på samtalen som skapade via interak-tioner i tid och rum och genomsyrade av maktrelainterak-tioner. Förskolans utveck-lingssamtal kan förstås som en producerande och normerande praktik och som en arena för subjektspositioneringar, framhåller Markström

Ingela Kolfjord är docent i socialt arbete med inriktning mot rättssociologi

vid fakulteten för Hälsa och samhälle vid Malmö Högskola. I sin artikel ”En

skolas implementering av kamratmedling” utvecklar hon sin presentation på

konferensen om konflikthantering. Kolfjord har under en tvåårsperiod inom ramen för projektet Mångkontextuell barndom genomfört fältstudier vid en F-6 skola. Hon beskriver steg för steg av genomförandet av kamratmedling på skolan. Utifrån en positiv sammanfattning av kamratmedlingens möjlig-heter som reparativ rättvisa, där hon intar en något annan hållning än Skol-verket i sin utvärdering, så anges avslutningsvis sex principer för förändring av en skolkultur.

Philip Lalander och Ove Sernhede är båda professorer med

samhällsveten-skaplig bakgrund, de är lokaliserade i Malmö respektive Göteborg. De är båda sedan lång tid engagerade i forskning om marginaliserade unga i stor-städernas miljonprogramsområden. I Social mobilization or street crimes:

Two strategies among young urban outcast in contemporary Sweden,

disku-terar de mot bakgrund i sin forskning kriminalitet och droger kontra social mobilisering, via hiphop, som två skilda vägar för utsatta unga att hantera social marginalisering i dagens Sverige.

10

I artikeln Vem är egentligen expert? Hiphop som utbildningspolitik och

pro-gressiv pedagogik, problematiserar lektorn vid Malmö högskola, Johan Sö-derman, hiphopens akademisering i USA. Söderman har under två år haft ett

postdok-stipendium från Vetenskapsrådet. Denna tid har han tillbringat vid Columbia University i New York City och på plats fått möjligheter att följa hiphopforskningens framväxt.

Vi vill avslutningsvis framföra ett varmt tack till fakulteterna Hälsa och samhälle (HS), Kultur och samhälle (KS), Lärande och samhälle (LS) och Odontologiska fakulteten (OD) vilka lämnat bidrag till nätverkets verksam-het samt till institutionen Barn Unga Samhälle (BUS) på Malmö Högskola och VR-projektet Mångkontextuell barndom för finansieringsstöd som möj-liggjorde konferensens genomförande.

Malmö 2011-09-01

Discursive Tensions on the Landscape

of Modern Childhood

Patrick J. Ryan

This text was delivered as a plenary lecture at the conference Barndom och

ungdom i förändring (Childhood and Youth in Transition: Discipline and unrest

in the modern welfare state) on October 29, 2010 at Malmo University, Swe-den. It offers a diagram for visualizing modern childhood as a product of the discursive tensions between four dominant figures: the conditioned child, the authentic child, the developing child, and the political child. The lecture focuses on the creative dynamics between conditioning and authenticity as they ap-peared in the 17th through the 19th-centuries in Anglo-American discourse. It argues that a search for the conditions of authenticity through childhood be-came manifest in the disciplinary practices of institutions for children’s educa-tion and care. The resulting generative tensions were important for construct-ing the landscape of modern childhood as a whole. Finally, it suggests that the tensions between romantic authenticity and rational conditioning continue to provide a significant discursive framework for contemporary child rights talk. Keywords: childhood, discourse, history, rights, discursive formation, para-digm, ideas, modern

Patrick J. Ryan, Kings University College at the University of Western On-tario

pryan2@uwo.ca

In the Journal of Interdisciplinary History, I presented a diagram which maps the landscape of modern childhood in terms of four discursive figures: the conditioned child, the authentic child, the developing child, and the polit-ical child (Ryan, 2008, p. 558). I argued there that these four figures have maintained coherence over several centuries and continue to mutually consti-tute each other. I also posited that the discourses of childhood emerged from two fundamental oppositions structuring the episteme of modernity as they were unpacked in Michel Foucault in The Order of Things (1970): the

ten-12

sion between subjectivity and objectivity, and the dualism between nature and culture [see Figure 1]. Today, I would like to advance this line of thought by arguing that the landscape of modern childhood took its shape with the figure of the authentic child as it formed a romantic opposition to the conditioned individual of Protestant/Enlightenment rationalism.

FIGURE 1: THELANDSCAPEOFMODERNCHILDHOOD

The Political Child of

Competent Agency

The Authentic Child of

Romanticism

The Conditioned Child of

Socialization

The Developing Child of

Positive Science

At the outset, it should be understood that the diagram shown as Figure 1 is a device for helping us conceptualize and speak about discursive structures which include dynamics beyond those displayed in the figure. I would also like to admit that this way of casting the discursive formation of childhood gives priority to the making of modern personhood. With these admissions, allow me to draw your attention to a recent video promoted by UNICEF to explain the child’s right to expression as granted by Article 12 and 13 of the UN CRC (Tellez, 2010). We see a child cutely depicted playing blocks at the

Subjects who Participate in their own Representation

Products of Environmental or Biological Factors

Natural Phenomena Cultural

Construction

12

sion between subjectivity and objectivity, and the dualism between nature and culture [see Figure 1]. Today, I would like to advance this line of thought by arguing that the landscape of modern childhood took its shape with the figure of the authentic child as it formed a romantic opposition to the conditioned individual of Protestant/Enlightenment rationalism. FIGURE 1: THELANDSCAPEOFMODERNCHILDHOOD

The Political Child of

Competent Agency The Authentic Child of

Romanticism

The Conditioned Child of Socialization

The Developing Child of Positive Science

At the outset, it should be understood that the diagram shown as Figure 1 is a device for helping us conceptualize and speak about discursive structures which include dynamics beyond those displayed in the figure. I would also like to admit that this way of casting the discursive formation of childhood gives priority to the making of modern personhood. With these admissions, allow me to draw your attention to a recent video promoted by UNICEF to explain the child’s right to expression as granted by Article 12 and 13 of the UN CRC (Tellez, 2010). We see a child cutely depicted playing blocks at the

Subjects who Participate in their own Representation

Products of Environmental or Biological Factors

Natural Phenomena Cultural

feet of his or her parents. The child is figured as the free-thinking artist creat-ing novel designs without reference to conventional forms. His or her au-thentic imagination is positioned in contrast to the over-conditioned adults, who are shown as nonsense murmuring, readers without the ability to think ‘outside the box.’ Clumsy are the adults of their own power to annul the imaginative child’s voice. The video defines the right to expression in terms of the child-adult dualism; this is no surprise. It did so by calling forth what I call ‘the conditioned-authentic couplet’ of personhood (Figure 1). Naming and recognizing this couplet can help us examine the discursive structure of modern childhood as a whole.

Interestingly enough, the original text of article 12 of the UN CRC exhi-bits a tension not deployed in UNICEF’s educational video. Article 12 speaks of a child’s “right to expression,” within “judicial and administrative proceedings.” Yet, it limits this right by reference to the child’s “age” and “maturity,” and with assurance that existing legal norms will remain in ef-fect. Ostensibly, we have an advancement of children’s rights to participa-tion as political subjects clawed-back with a developmental assumpparticipa-tion that they are often incompetent to exercise these rights well. This suggest some-thing important about the politics of development within rights-talk. I do not say this to argue for (or against) any particular figure of childhood; that is not my purpose today. My hope is to further our ability to read texts such as the UN CRC and UNICEF’s video as products of the major generative ten-sions between the four discourses which have arisen on the landscape of modern childhood (Figure 1).

An Historical Sketch

The landscape of modern childhood began to take shape with the shift from Protestant Reformation to Enlightenment Rationalism in the 16th and 17th centuries. During this period there was a contraction in the theologi-cal/epistemological space between the sacred and the profane, between the motions of the heavens and the mechanics of the earth. Early-modern Euro-pean cultures affirmed ordinary life and relocated ancient ideas about reason, virtue, and authority within increasingly robust and complex discourses on human interiority (Taylor, 1989). One element of this cultural movement was the emergence of ‘the conditioned child’ of Lutheran and Calvinist pe-dagogy (Luke, 1989). However, I believe this picture of childhood became

14

fully constituted only when it was twinned with its opposition: the ‘the au-thentic child’ of romanticism (Wishy, 1968; Reiner, 1996).

Let me break my narrative of change into several parts. First, the cultural terrain defining the opposition between the conditioned child and the authen-tic child was opened through pedagogical innovations of early-modern Prot-estant households: the catechism, the growth of literacy, personal invento-ries, diary writing, the creation of family privacy, participatory religious forms, and a host of minute changes associated with a transformation of child rearing by the late-18th-century. These shifts in children's experiences and household practices laid the setting for a new perspective on personal emancipation. What I dub 'a search for the conditions of authenticity' through childhood worked its way into a spectrum of texts, artefacts, de-vices, and institutions: from domestic advice literature to juvenile reformato-ries, from paediatric manuals to educational reform, and throughout a wide spectrum of child-saving efforts to confront abandonment, poverty, and de-linquency.

In a preliminary way, I would like to suggest that we make a special place for the discourses of childhood in the creation of what Foucault called “the carceral” - a culture defined by a disciplinary sensibility - or - as a means of Foucaultian “governmentality” - the pursuit of social control by means of psychological technologies (Foucault, 1977; Foucault, 1991; Rose, 1999). Modern childhood has become more than merely one of a number of ways to image how individuals learn to watch themselves. It presents an aura of inevitability. Moderns can easily imagine becoming a self-reflexive adult without ever having subject to the disciplinary regimes (hierarchical observation, normalizing judgment, examination, graphic visualization, pharmacological treatment, etc.) that are visited upon the insane, feeble-minded, criminal, sick, or otherwise abnormal. What we do not imagine is becoming such an ‘adult’ without having been a child. This gives childhood a special relationship to selfhood, and interferes with our ability to make sense of modern individualism as a power-knowledge complex.

The Enlightenment’s Well-Conditioned Child

Enlightenment philosophers such as René Descartes and John Locke inhe-rited a low opinion of children from biblical and classical sources; they both associated childhood with sensual irrationality. Yet during the 16th- and 17th-centuries, “reason” moved from the eternal chain of master-servant relations connecting Man to God to a process developed within the individu-al, and this allowed new conditions of possibility for childhood to appear (Krupp, 2009, p. 24-48; Descartes, 1991, p. 256). For Descartes the preju-dices of childish senses might be wiped away by “meditation,” and thus ra-tional disengagement would emerge from “studies within oneself” (Krupp, 2009, p. 48). Similarly Locke believed that only the disciplined control of the desires and perceptions would allow rationality to triumph upon the blank slate of the emerging human subject (Taylor, 1988, 143-176). One of the great childrearing errors, said Locke, was the failure of adults to make children’s minds “obedient to discipline and pliant to reason when first it was most tender and most easy to be bowed” (Locke, 1996, p. 23-24; Brown, 1996; Schouls, 1992).

Because Locke radically reduced the importance of original sin as part of his rejection of monarchy, he implicitly challenged the similitude which had long defined childhood in terms of the relations between the obedient Chris-tian servant and the benevolent master (Schouls, 1992, p. 192-203). We can see this most clearly in Some Thoughts on Education (1693), which Gordon Wood once called “the most practically significant book Locke ever wrote” (as cited in Ezell, 1983/4, p. 139). Locke’s well-conditioned young gentle-man should be subjected to regimes for self-control, rather than ones of ex-ternal force. Whereas St. Paul taught that submitting to Christ required the purging of childhood from the bowels of man, Locke’s boy is trained in the time-disciplined concealment of his own bowel movements. He called it putting “nature on her duty,” with strict observance after the day’s first meal (Locke, 1996, p. 23-24). As Nick Lee has observed, it was as if early-modern Europeans believed that childhood training would allow them to evacuate from the bowels of the self the filth of their own embodiment (Lee, 2005). An extensive catalogue of new etiquette and mannerly behaviors that came with this effort can be found in Norbert Elias’ The Civilizing Process (Elias, 2000; p. 45-172).

According to Locke, brute enforcement of rules by masters only accen-tuated the human propensity to pursue pleasure and avoid pain. Such a

clum-16

sy use of power would only exacerbate the problem of persons governed by their bodily desires. The pleasure principle could not be conquered by the threat of pain, but only by constructing a greater or supremely pleasurable sensibility outside the bodily senses. Locke believed this could be done through the socialization of children to love how they appeared to others – or by substituting the “love of reputation [for] satisfying the appetite” (Locke, 1996, p. 40, 98-99, 139). The road to this was minutely and daily traveled, and it entailed a more thoughtful consideration of power and manipulation. For example, Locke advised that if a boy wishes to play with a spinning top more than he should, assign it to him as a “business,” and “you shall see he will quickly be sick of it and willing to leave it.” Then relieve him from the assignment of whipping the top with the “recreation” of studying his books (Locke, 1996, p. 51-61). Following the logic of conditioning the child's ex-periences, many latter-day Lockeans have constructed elaborate systems of habit-formation for children and youths; what he called making appropriate behavior “natural in them” (Locke, 1996, p. 39).

Among Anglo-American gentry and artisanal classes of 18th-century, di-ary writing became a common practice for a Lockean self-monitoring one’s appetites, habits, and character. One might view diary writing as a ritual of inscription by which the person creates a conversation with, or a view of, or relationship with his/her self. One could establish self-esteem or a 'reputation' within the self. Here I am suggesting something more internal than Locke's own sense of 'reputation' was developed in 18th-century prac-tices. Benjamin Franklin recommended precisely this sort of self-examination by charting thirteen personal virtues in a diary. This purported-ly would help a young gentleman learn to love the good marks upon a

bal-ance-sheet of the self more than the pleasures of an immoderate appetite

(Franklin, 1819; Franklin, 1987). George Washington created a similar checklist for himself and offered it as an important technique for young men. Abigail Adams advised her 12-year-old son, John Quincy Adams, in 1780 that “one of the most useful lessons in life [is], the knowledge and study of yourself,… self-knowledge.” Keeping an eye on his self would allow a gen-tleman to understand the horror of “passion… unrestrained by reason,” and secure “happiness to yourself and usefulness to mankind” (as cited in Masur, 1991, p. 197-198). Practices of self-inspection internalized the meaning of “virtue.” The ancient idea that civic devotion emerged from landed indepen-dence was remade into a notion that personal purity depended on self-control. We hear the modern sound of “virtue” when George Washington is

portrayed in an early biography as a legitimate leader, esteemed by his peers because of “unvarying habits of regularity, temperance, and industry” ac-quired in youth (as cited in Reiner, 1996, p. 35-36).

The Romantic Response

For early-modern Anglo-Americans (at least, but not exclusively), a well-conditioned person promised a way to ground social order within individual competencies at a time when external forms of master-servant authority were challenged and overthrown. Yet, the promise of childhood conditioning was not articulated as a singular positivity. It surfaced in dialectic tension with a romantic critique of rationalism. This dynamic was at work in Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Émile OR On Education (1762). While Locke had warned against

the larger results of a master’s arbitrary use of power, Rousseau goes deeper into the invisible space of the self-perceiving individual. Rather than trying to condition children for study, Rousseau’s tutor takes “away all duties from children” especially “the instruments of their greatest misery – that is, books.” Young Emile will receive only one book, The Adventures of

Robin-son Crusoe, because Rousseau reads it as a story about a man facing the

unmediated consequences of nature (Rousseau, 1979, p. 184). Rousseau’s child will learn the danger of a candle’s flame by experiencing its burning sting (Rousseau, 1979, p. 122).

Rousseau tells us that “[p]unishment as punishment must never be in-flicted on children, but it should always happen to them as a natural quence of their bad action.” The tutor must “arrange it” so these conse-quences come to bear upon the child without the child’s awareness of the arranging action (Rousseau, 1979, p. 101). In sum, Locke offered a child conditioned to control his corporeal desires to seek higher pleasures, while Rousseau hoped to nurture an authentic child who “lives and is unconscious of his own life” [vivit, et est vitae nescius ipse suae] (Rousseau, 1979, p. 65-69, 74, 80-95, 116; Houswitschka, 2006). Here we might see a paradox. Rousseau’s supposed attempt to free child-rearing from the master’s authori-ty – his advocacy of ‘natural consequences’ – requires his tutor to become even more deeply involved in an elaborate project of deception as he mani-pulates the ‘real’ learning experiences of children. We have travelled further down a twisted path of hidden curriculum.

18

The distinction between the dominant early-modern discourses of child-hood and the romantic critique of them is important. The Reformation did not give us liberal individualism, so much as the empire of the ordinary fa-ther. Martin Luther could claim - rather stunningly - that there was “no pow-er on earth” could equal that of parents prior to leaving the monastpow-ery and marrying a nun (Ozment, 1983, p. 183). Protestant reformers would go on to make a veritable industry out of family and child tutorial literature and vastly elaborate schooling for common children. Yet under romanticism, childhood became something more than preparation for the life of a disciplined servant of God the father; it offered an entirely new vista upon humanity interiority. We can glimpse this inner depth in the paintings of families and children found in late-18th-century European and American art (Johnson, 2006, p. 15; Fort, 2006, p. 17-18; Heywood, 2007, p. 52-63; Mintz, 2004, p. 79; Reiner, 1996, p. 40-42; Calvert, 1992, p. 55-56, 79-81). The romantic poets offer easier text to cite; William Wordsworth wrote not only that, “[t]he child is father of the man;” (Wordsworth, 1988a, n.p.), but with a spirit unfouled by society, he lives closer to immortality. The child was a “Mighty Prophet! Seer blest” (Wordsworth, 1988b, n.p.). Goethe tells us that “Children can scarcely be fashioned to meet with our/ likes and our purpose./ Just as God did us give them, so must we hold/ them and love them,/ Nurture and teach them to fullness and leave them/ to be what they are” (As cited in Cremin, 1980, frontpiece; Steedman, 1995). Schiller claims that a child should “be a sacred object,” deserving a “kind of love and touching respect,” which we give to nature, because “they are what we were; they are what we ought to become once more” (Schiller, 1985, n.p.; Plotz, 1979, p. 66).

In his essay Nature (1836), Ralph Waldo Emerson called man “a god in ruins.” The world “would be insane and rabid, if these disorganizations [of maturity] should last for hundreds of years. It is kept in check by death and infancy. Infancy is the perpetual Messiah, which comes into the arms of fallen men, and pleads with them to return to paradise” (Emerson, 1971, p. 42). Emerson’s fellow New England transcendentalist, Bronson Alcott, con-curred. Early childhood offered us “visions of bliss, which bring before the mind the remembrance of the joys of previous existence and the whole intel-lectual principle full of the divine life!” The story of corruption, fall, renew-al, and salvation (of course) was inherited from Judeo-Christian traditions, but situating this narrative within the individual through child development was a radical departure from the ancient cosmology. The countless hours Alcott spent with his daughters, compiling twenty-five hundred pages of

observational notes on Anna, Louisa May, and Elizabeth Sewall, were li-kened by him to the experience of grace: “Childhood hath saved me!” (as cited in Strickland, 1969, p. 11, 16; Cremin, 1980, p. 86). As American Quaker John Greenleaf Whittier put it in “Child-Songs,” “We need love’s tender lessons taught/ As only weakness can;/ God hath His small interpre-ters;/ The child must teach the man” (Whittier, 1875, n.p.)

If modern art might be defined as the pursuit of freedom from suffocating classical forms, the romantic child purportedly holds the keys to unmediated truths of modernity. If the ancient word "infant" meant one without speech, the romantics recast it as a type of communion of being that collapsed the space between words and things (Bernier, 1973, p. 120-187; Taylor, 1989, p. 362, 374-381, 420-421; Plotz, 2001). The pressing utility of a wordy adult-hood became viewed as a “killing frost” to the “vernal bud” of childadult-hood, dwarfing the capacities of us all (De Quincey, 1889, p. 121). This was me-morably and repeatedly enacted in Charles Dicken’s novels where the Grad-grind’s and Choakumchild’s of mature industrial capitalism are so unfavora-bly counterpoised to the insightful and self-reflective children of humanity (Dickens, 1981, p. 76-83).

The Search for the Conditions of Authenticity

Many scholars have elaborated upon Peter Coveney’s argument, delivered fifty years ago; the “romantic child came from deep within the whole genesis of our modern literary culture” (Coveney, 1967, p. 29; Pattison, 1978; Alryyes, 2001; Levander, 2006, p. 78-110). Yet it is important to understand that this figure permeated into middle-class practices, institution-making, and political consciousness. Traditional techniques used to control bodily shapes and movements of infants and young children disappeared with the new faith in nature and moral elevation of motherhood. Late-18th-century Americans threw away standing and walking stools, corsets and leading strings. They abandoned tight full-body swaddling and stopped strapping babies down at night. Newly designed cribs with open slats, lighter bedding, and looser clothing allowed the free flow of air. Bathing infants in progres-sively colder water was introduced under the idea that the child would be-come acclimated to the temperatures of the natural world. Allowing infants or young children to consume cakes, pastries, coffee, tea, gravies, spicy foods, and meats came under criticism, as cold water, milk, bread, and fresh

20

vegetables emerged as the healthy, “natural foods.” The physical exuberance of youth ceased to be viewed as a remnant of original depravity, and a lack of rambunctiousness was refigured as a sign of ill-health (Wishy, 1968, p. 37-38).

Collectively, the late-18th-century shift in child care expressed the idea that nature - represented in the infant, young child and mother - was either a well-ordered mechanism [rationalism] or manifestly good [romanticism] (Ezell, 1983/4, p. 146). To be sure, nursing mothers of noble birth had been praised in medieval Europe, because their milk was viewed as a type of blood by which aristocratic children received an embodiment of their “pure lineage” (Schultz, 1995, p. 75-76). Babes imbibed noble virtues from it and maintained the communal link to divine right. With modernity, the under-standing of nursing became part of transmitting the sentimental ideals of domestic love. Increasing numbers of wealthy mothers chose to nurse their own babies, as the criticism against wet-nursing mounted in popular litera-ture for parents. Motherhood emerged as a purifying force against bodily desires in general. Physicians criticized “mercenary” wet-nurses for being ignorant, obscene, and negligent; in Rousseau’s words, “She who nurses another’s child in place of her own is a bad mother. How could she be a good nurse?” In short, the heroic virtues of aristocratic lineage surrendered to the virtuous purity of feminine self-sacrifice and self-control (Calvert, 1992, p. 55-72, 75; Dewing, 1882, p. 166; Martineau, 1861, p. 1-10; McMil-len, 1985; Benzaquén, 2006).

The movement of virtue within the person which inspired the rise of mid-dle-class child-rearing is written into countless books of advice circulated and read on a massive scale (Reiner, 1982). Take American, Enos Hit-chcock, who composed a series of parental advice letters, and printed them as Memoirs of the Bloomsgrove Family in 1790. Citing both Locke and Rousseau, Hitchcock’s child “should love its mother before it is sensible of it as a duty. If the voice of nature is not strengthened by habit and cultivation, it will be silenced in its infancy” (Hitchcock, 1790, p. 82). Hitchcock ad-dressed his book to all Americans - regardless of class. He quoted John Adams’ argument that new methods of childrearing and education were re-quired to create an internally virtuous people. Schooling the poor was better than “maintaining the poor… [because it] would be the best way of prevent-ing the existence of the poor” and the vices of poverty (Hitchcock, 1790, p. 252).

In the period immediately following the American Revolution, an intense debate about the nature of virtue ensued among the former colonists. Agra-rian radicals defended a ideal of landed independence to be sure. But, they lost the battle. In Pennsylvania, Benjamin Rush argued that uniform, public schooling would make it possible to “convert men into republican machines. This must be done if we expect them to perform their parts properly in the great machine of the government of the state” (Rush, 1965, p. 9, 17). In Hit-chcock and Rush (as well as Daniel Webster and Thomas Jefferson), we begin to find a nodal point in the discourses of childrearing and public schooling where the authentic child and the conditioned child mutually de-fine the other. Rush’s hope that schools could build “republican machines” serving the state crisply sounds the rationalist note for a well-conditioned population, but his perspective was also informed by romantic interiority. He was convinced that modern civilization had caused an “inundation of artifi-cial diseases, brought on by the modish practices,” and these diseases were the “offspring of luxury” (as cited in Yazawa, 1985, p. 144-149). This line of thought encouraged Rush to conclude that the revolution against Britain was won only on the surface, because without a transformation in American edu-cation -- a revolution within -- “our principles, opinions, and manners” would be far more difficult to establish and maintain (as cited in Tyack, 2001, p. 335). In fact, Rush exclaimed, that “THE REVOLUTION IS NOT OVER,” because the war wrought only a change in the artifice of govern-ment but could not consummate the transformation of true governance with-in the body and mwith-ind (Rush, 1998, n.p.). That could only come with a “change [to] the habits of our citizens” (Wagoner, 2004, p. 51).

Fomenting an internal revolution led Rush to help found the founding of the Young Ladies’ Academy in Philadelphia in 1786. He believed that the, “instruction of children naturally devolves upon the women…” and that this was critical to the survival of Christianity in the Republic. This ideal of “re-publican motherhood” was an essential element of the search for the condi-tions of authenticity through childhood. Take Anna Letitia Barbauld’s popu-lar late-18th-century Hymns in Prose for Children, a set of twelve passages written for children to memorize and recite. The Hymns reflected a growing sensitivity to the processes of developmental socialization. The type is set extra-large with ample white space; there is a simplification of the diction and a removal of the poetic structure of hymns (Barbauld, 1788, p. 62, 67). It serves as a sort of catechism for romantic childhood. It is almost bereft of substantive Christian characters, references, terms (McCarthy, 1999). The

22

biblical patriarchs have been upstaged by flowers, streams, wind, birds, sun-light and the seasons as the way to commune with creation. God “has be-come the voice of nature.” Here, Barbauld is reiterating Rousseau’s romantic image of God. In Émile, society’s “noisy voices drown her voice, so that she cannot get a hearing… She is discouraged by ill-treatment; she no longer speaks to us” (as cited in Taylor, 1989, p. 357-358). In Barbauld’s Hymns, God is within the storm, behind growth, and manifest as the “voice” of the roaring lion, the murmuring waters, or the whispering wind. Sometimes God is figured as the voice of a parent, and specifically that parents is a mother (Barbauld, 1788, p. 20, 31, 54).

The domestication of the Christian search authentic devotion finds its high-tide in Horace Bushnell’s Christian Nurture, published in several ver-sions between 1847 and 1861. For Bushnell the opposite of “Christian Nur-ture” was the “unmotherhood” of an ostrich (Bushnell, 1908, p. 65). The ostrich’s buried egg may or may not hatch. True motherhood helps the child to become a Christian without having ever known the self otherwise, be-cause the Christian parent does not simply wait for morality to hatch. ‘Os-trich’ nurture prepares children for a future conversion to Christianity, while Christian nurture is lived daily within a protective harmonious sphere of love. Unfortunately, says Bushnell, too many fathers are “busy, worldly, hard-natured,” and too many mother’s are “vain, irritable, captious, fashion-loving.” “Were [parents] really to live so as to make their house an element of grace, the atmosphere of their life an element, to all that breathe it, of unworldly feeling and all godly aspiration,” few children would fail to reap God’s “saving mercies” (Bushnell, 1908, p. 75). Many have read Christian

Nurture an attack on both the doctrine of original sin and all institutions of

religion outside the home. Bushnell claimed that only to be promoting the idea that a child can receive a “new heart” right from the beginning of the child’s self-awareness (Bushnell, 1908, p. 16-17). In short, Bushnell was clothing Rousseau in an evangelical blanket. Both writers proposed that the conditions of authenticity rested on the ideal that a domesticated home might create reflexivity (an awareness or internal conversation with the self) with-out the duplicity of a Lockean love of one's external reputation. We might say this would be a person who values self-esteem over social status.

The Disciplinary Institutions of Modern Childhood

At this point, you might be asking: what does middle-class domesticity, di-dactic literature, and evangelical sentimentality have to do with disciplinary institutions? My rhetorical answer would be: who do you think invented the disciplinary institutions of modern childhood? Answer: the same folks who wrote and read these texts. Bushnell’s “Christian nurture,” much like Rush’s “Republican machines,” Barbaud’s Hymns, and Hitchcock’s domestic vir-tues all followed Rousseau attempt to collapsed ancient discourses on Chris-tian charity and civic virtue into a pedagogical framework. A radical ad-vancement of human interiority was institutionalized as a feature of the 19th-century moral reform of childhood. Disciplinary institutions produce a self-hood caught (much like the above texts) on the dialectics between romantic-ism and utilitarianromantic-ism.

Take the Sunday School Movement, started by Robert Raikes in Glouces-ter, England in 1781-2. Raikes believed England’s textile industry drew par-ents away from their natural duties, while their poor, “children, from six to twelve or fourteen years of age, were running wild in the streets” (Cremin, 1980, 62-72; James, 1816). On Sundays when the factory was not operating the “noise and blasphemy,” of the common people descended into property destruction. To remedy this, Raikes hired teachers to open a school for two hours on Sundays to teach literacy, the catechism, and to encourage children and youths to go to church. Unlike earlier efforts to institute the proper show of respect among the poor by publishing guides and other didactic materials, the Sunday School Movement attempted to displace the household, the workshop, the even the parish as the nexus for delivering moral sensibilities. The movement’s institutional model was the factory that was seen as the source of the trouble. Ironically, the solution was a factory-like, monitorial school.

Like Methodism, the Sunday School Movement may have been invented in England, but it flourished in America. With Benjamin Rush’s support the first American Sunday school opened soon after the Revolution in Philadel-phia with 120 children up to age 10 years. It added another 120 in the first month. By 1813 the Philadelphia rolls listed 724 names and by 1815, 1008 names. In the year 1819 alone, 43 Sunday schools were created in other U.S. cities reportedly serving 5,658 children, and 312 adults (Cremin, 1980, p. 89-90).

24

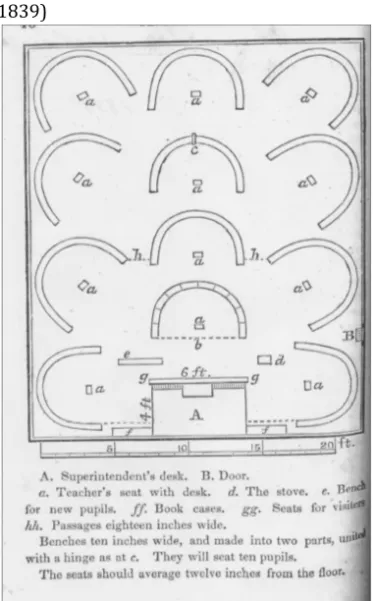

By the late 1820s, a single Sunday school might enrol 300 students in a room 60 by 20 feet. Floor plans (see Figure 2) created lines of vision allow-ing a head-teacher to view all the students while the student’s eyes would be directed in semi-circles toward group monitors. This careful arrangement of space strikes a panopticon-like prose. The children sitting on the benches in curves could not know precisely or easily when they were being observed from the raise platform. They would learn to watch themselves. The discipli-nary element is implicit; it is inscribed into the spatial arrangement. It comes not as a command from a master, but as a ‘natural consequence’ of the situa-tion.

Figure 2 - Sunday School Floor Plan(American Sunday-School Union, 1839)

Unlike Jeremy Bentham’s prison, the Sunday Schools were more than de-signs of a utilitarian philosopher. They were built by the scores, and expe-rienced by thousands. Institutionally, they were part of an “evangelical surge,” that defined the early American cultural landscape (Noel, 2002, p. 161-226). The schools associated the conditioning poor children to industrial discipline with the prostheletizing project of saving their souls. A Handbill from the 1790 Philadelphia First Day Society declared plainly that the stu-dents were “children of the indigent poor… [who were] rescued from savage ignorance, acquired habits of order and industry” (as cited in Reiner, 1996, p. 80). As Locke and Rousseau had taught, these habits could not be instilled through a master’s force. Teachers constructed implements like the one shown below in Figure 3. Note, how the apparatus isolates the child, but also requires an upright posture. These boxes restricted communication, but allow for observation of either from a raised platform or by exposing the child’s dangling legs. The technique of hierarchical observation which was more diffusely present in the room’s spatial layout has been intensified. The gaze of the teacher is the point of pressure, rather than the master’s overwhelming force upon the body. The child’s own perspective (their sense of themselves in space and time) is being strengthened as a means of control.

Though it may seem strange, I believe disciplinary devices such as these are consistent with a participatory, child-centered approach to training and learning. Think about them in terms of a longer historical shift. For centu-ries, children and youths had learned work discipline by being indentured into relations of servitude which stipulated a set of familial obligations. They would abstain from of sex and matrimony; protect the master’s interests; reside within his household; refrain from vices. The master was obliged to teach the mysteries of the craft, literacy, and the catechism; to provide cloth-ing and food; and sometimes land, tools, and letters at the end of the time of service (Abbott, 175-177). The monitorial school arose precisely because apprenticeship and the master-servant relations of production collapsed un-der the weight of industrialization and the force of emancipatory revolutions. Monitorial schools carried a new understanding of control into childhood. It is true that the Sunday schools commonly posted rules containing a tradi-tional command for students to obey the teachers, but the vast majority of these rules demanded that students to “sit still,” to “walk softly,” to not “lean” on the student seated next to you. They must mind the time and move in and out of the building without congregating at the door. In the monitorial

26

school-room, bodily, spatial, and time discipline was at a premium: stillness, quietness, softness, care, posture, promptness.

Figure 3 - New Implements of Discipline (American Sunday-School Union,

1839)

The factory and factory-like school had no space or time for external and extended master-servant commitments to be sure. In fact, master-servant relationships were precisely what the school was designed to move beyond – to create Rush’s “revolution within.” The rules of the Sunday schools were printed onto forms which were signed – not by the fathers and masters – by the pupils themselves. Because the locus of regulation had been resituated within the self, introspection and consensual participation was encouraged.

Some schools used systems of tickets by which students could tabulate good behavior which later could be “spent” on a bible or other sponsored items. The Lockean “balance sheet” of the self composed within the diaries of 18th -century American gentry and artisans had been translated into a commodity-form of printed currency (Reiner, 1996, p. 102-124).

Not all disciplinary training was optical. Sunday schools were full of singing, call-and-response, and orderly reading aloud. A teacher might lead the children with a call, “What is Required,” to which they learned to re-spond in unison: “A Changed Heart.” It is at least worth speculating as to whether the practices of vocal student participation developed in the Sunday Schools were related to the later development of child-centered, expressive socialization which would be perfected with the comprehensive high schools of the 20th-century (Ryan, 2005). Be this as it may, there can be little doubt that the schools were part of a “humanitarian sensibility” which encouraged both self-examination and its reverse: seeing others as subjects worthy of concern regardless of filial proximity (Haskell, 1985). We can hear this in a late 19th-century Sunday School song: “Go bring him in, there is room to spare/Here are food and shelter and pity/And we’ll not shut the door ‘gainst one of Christ’s poor/Though you bring every child in the City” (as cited in Waite, 1960, 4, 7).

Self-reflexive humanitarianism was the ideological core of 19th-century moral reform. Take The Child’s Book on the Soul (1831), where the famous founder of the American Asylum, at Hartford, for the Education and

Instruc-tion of the Deaf and Dumb (est. 1817), Thomas Gallaudet explained that the

difference between a child and an object was “self-examination.” The Child must see himself as a “little-thinker,” with the dignity of an intellectual be-ing. Gallaudet’s book offers a series of dialogues addressed to children, without reference to religious authority, supported by the principle that all education was to “teach a Child that he has something within him distinct from the body, unlike it, wonderfully superior to it, and which will survive it after death” (Gallaudet, 1850, p. iii, vi-viii).

The attempt to created mechanisms and programs that would produce what we might call ‘self-realization’ was connected with how 19th-century reformers responded to their fears about urban disorder. This is inherent in the question that Charles Loring Brace (founder of the Children`s Aid

Soci-ety) used to frame his work. What were respectable people to do, Brace

asked, when “the outcast, vicious, reckless multitude of New York boys, swarming now in every foul alley and low street, come to know their power

28

and use it?” (Bremner, 1956, p. 213). For Brace, building more custodial institutions of unprecedented size, ordered by industrial discipline for poor, disabled, and otherwise marginal people was both expensive and destructive (Boyer, 1978). His alternative was to send them on trains to Western farms in the romantic hope that agricultural values and pastoral harmony (as op-posed to urban conflict and degeneration) would revitalize their humanity. A few years later in England, Thomas John Bernardo helped create the infa-structure of homes which allowed for about 80,000-100,000 poor British children (called “home children”) to be shipped to rural Canada from 1869-1938. Most of these children were sent to farmers as labourers, following the rationale set by Brace’s CAS Orphan Trains (Bremner, 1956; Gordon, 1999). The “orphan trains” and the “home children,” efforts in America and the British Commonwealth served as a point of departure for a larger movement toward home placement and the construction of a minute architecture for monitoring poor families and children. This monitoring structure would reach with far greater sophistication than the monitorial school room into the lives of poor and otherwise disadvantaged children. It includes the creation of juvenile courts, an army of social workers visiting homes, the opening of settlement houses, and dispensing poverty relief to families. All long this spectrum of modern welfare services we find the pedagogy of individual hygiene and self-discipline (Platt, 1969; Donzelot, 1979; Lissak, 1989; Ash-by, 1997, p. 17-54).

The Conditioning-Authenticity Couplet & 20th-Century Child

Saving

With the dawn of 20th-century welfare policy, new discourses of childhood, family, and the state entered the scene (Zelizer, 1985; Ladd-Taylor, 1995; Ryan, 2007). Notably, positivistic theories of human development and new forms of graphic visualization defined a network of services that medicalized almost every issue you can imagine from bed-wetting to nail-biting (Rose, 1999; Turmel, 2008). though scientific developmental thought and practice created a new space in the discursive formation of childhood, the search for the conditions of authenticity continued to provide an important thematic tension.

In 1920, the state of Ohio stipulated five principles for the placement of juvenile wards which supported a movement toward fostering children in

families and providing income support to mothers. In contrast to institutiona-lization, children’s agencies should: (1) require documentation of neglect prior to pursuing custody; (2) attempt to reunite the family; (3) give correc-tive medical care; (4) require the children to attend school and church; (5) attempt to “make the daily life of the children approximate the family ideal in order that their individuality may be developed and that they may escape institutionalization,” (as cited in Ryan, 1997, p. 675-677). This formal state-ment of ‘best practices’ for Progressive-era Ohio advanced the ideal of ro-mantic domesticity for all children. Yet, it was also part of a measurable nation-wide shift toward family placement in the U.S. By 1933, an estimated 102,000 American children were fostered in families, but another 140,000 continued to live in orphanages, and many tens of thousands more were held in state institutions for the feebleminded, and juvenile reformatories (Mor-ton, 2000, p. 438). By the mid-century the numbers of children in foster care exceeded those in custodial institutions, and by century’s end there were more than twice as many children in foster care with a total numbering over a half-million persons (Barr, 1992, p. 32).

The continued relevance of the conditioning-authenticity couplet in 20th -century discourse is also visible in the first attempts to secure international declarations for children’s rights. The most prominent American in these efforts was Herbert Hoover. Speaking in 1920 in the aftermath of WWI, Hoover highlighted the importance of children’s rights by claiming that “Love of Children is a biological trait shared by all races,” and therefore protecting them could become the common ground for humanity to build a lasting peace (as cited in Marshall, 2008, p. 358). He noted in his memoir that with, “... rebuilding the vitality of the children came the great relieving joy in the work of the Belgian Relief. The troops of healthy, cheerful, chat-tering youngsters lining up for their portions; eating at long tables; and cleaning their own dishes afterwards were a gladdening lift from the drab life of an imprisoned people,” (as cited in Marshall, 2008, p. 359). In Hoov-er’s vision, children were troops, well-behaved and vital, embodying the cheerful, chattering health that might induce a hope otherwise destroyed by occupation and imprisonment -- the brutal consequences of modern organi-zational power. This image of the power of childhood to save the world, and recover a broken humanity, carried forth Hoover’s children were natural actors, rather than political ones, but this did not mean all would be well without elaborate forms of intervention. In Hoover’s own words uncared for children might become a “menace to their nation,” and stand as those

Ger-30

man “brutes” responsible for the War (as cited in Marshall, 2008, p. 360. 385).

For Hoover, the purpose of articulating “children’s rights” charters was to rescue the world from the destructive consequences of generations of mala-dapted or mal-conditioned adults. Later this would be named the “authorita-rian personality type.” Such a diagnosis for the collapse of European civili-zation in the early-20th-century could not have been articulated without the tension between conditioned functionality and authentic wholeness. After '33-'45, who could blame anyone who searched for the conditions of a whole and decent humanity through childhood? But it was not a result of the fascist period. This search framed the Children’s Charter of Hoover’s White Confe-rence of 1930, just as it continues to frame UNICEF’s presentation of article 12 and 13 of the UN CRC. The first three articles might suffice (U.S. Child-ren’s Bureau, 1930).

I. For every child, spiritual and moral training to help him to stand firm under the pressure of life. II. For every child understanding and the guarding

of his personality as his most precious right. III. For every child a home that love and security

which a home provides, and for that child who must receive foster care, the nearest substitute for his own home.

What is imagined in this text? The spiritual and the moral are pictured as properties of the self enclosed within the personality of individuals standing against the world. A childhood guarded in a domesticated home is presented as the best means to develop this authentic moral sensibility. We are back to where we started with UNICEF short video in 2010. Children’s rights to expressive life insure that they are not over-conditioned into drones. But this is not an expressive “political” child; they are not cast as social subjects with rights to negotiate and participate in a moral and spiritual world. They are to be protected and well-nurtured children.

Concluding Remarks

The exploration of the landscape of modern childhood presented here is not an attack children’s rights to care and protection, the UN CRC or UNICEF. Showing that a film or a charter or an organizational effort is grounded in a foundational discursive tensions does not steal their legitimacy. It only makes the ideological dynamics more visible. This is my hope.

To summarize: Modern childhood has become an indispensible way to imagine the possibilities for a self-reflexive or disciplined subject. This be-gan with an early-modern affirmation of ordinary life, and the Protestant construction of the well-conditioned child. Yet, the full sense of children as products of conditioning was not fully articulated until romanticism posited its opposite: the authentic child – the natural actor. Today, the conditioning-authenticity couplet remains powerful even as other generative tensions have joined it: (1) nature vs. nurture, or (2) the politics of developmental deter-minism.

Seeking the conditions of authenticity through childhood continues to re-sonate in part because it was institutionalized with the rise of disciplinary regimes beginning in the late-18th and early-19th-centuries. If my under-standing of this movement is correct, it implies that we further consider whether childhood has a unique place within our larger disciplinary history, and to ask how childhood serves governmentality.

Reference list

Abbott, M. (1996). Life Cycles in England 1560-1720 – cradle to grave. New York, NY: Routledge.

American Sunday School Union. (1839). The Teacher Taught; an humble

attempt to make the path of the Sunday-school teacher straight and plain.

Philadelphia, PA: American Sunday School Union.

Alryyes, A. (2001). Original Subjects: The Child, the Novel, and the Nation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Ashby, L. (1997). Endangered Children: Dependence, Neglect, and Abuse in

American History. New York, NY: Twayne Publishers.

Barbauld, A. (1788). Hymns in Prose for Children... Philadelphia, PA: Bache, Benjamin Franklin.

32

Barr, B. (1992). Spare Children, 1900-1945: Inmates of Orphanages as

Sub-jects of Research in Medicine and in the Social Sciences in America.

(Doctoral dissertation, Stanford University, 1992).

Benzaquén, A. (2006). The Doctor and the Child: Medical Preservation and Management of Children in the Eighteenth-Century. In A. Muller (Ed.),

Fashioning Childhood in the Eighteenth Century: Age and Identity (pp.

13-24). Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing.

Bernier, N. and Williams, J. (1973). Beyond Beliefs: Ideological

Founda-tions of American Education. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Boyer, P. (1978). Urban Masses and Moral Order in America, 1820-1920. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bremner, R. (1956). From the Depths: The Discovery of Poverty in the

United States. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Brown, S. (1996). The Childhood of Reason: Pedagogical Strategies in Des-cartes’s La recherche de la vérité par la lumière naturelle. Romantic

Re-view, 87, 465-480.

Bushnell, H. (1908). Christian Nurture. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Pub-lishers. (Original work published 1849).

Calvert, K. (1992). Children in the House: the material culture of early

childhood, 1600-1900. Boston: MA: Northeastern University Press.

Coveney, P. (1967). The Image of Childhood: The Individual and Society; a

study of the theme in English literature. Baltimore, MD: Penguin Books.

Cremin, L. (1980). American Education: The National Experience, 1783-1876. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

De Quincey, T. (1889). Infant Literature. In D. Masson (Ed.) The Collected

Writings of Thomas De Quincey, New and Enlarged Edition, Volume I, Autobiography from 1785-1803 (pp.121-132). Edinburgh, Scotland:

Adam and Charles Black. (Original work published 1851-2).

Descartes, R. (1991). The Philosophical Writings of Descartes, Volume 1. (J. Cottingham, R. Stoothoff, and D. Murdoch, Trans.). Cambridge, Eng-land: Cambridge University Press.

Dewing, M. (1882). Beauty in the Household. New York, NY: Harper Row. Dickens, C. (1981). Hard Times. New York, NY: Bantam Books. (Original

work published 1854).

Donzelot, J. (1979). The Policing of Families. (R. Hurley Trans.). New York, NY: Pantheon Books. (Original work published 1977).

Elias, N. (2000). The Civilizing Process (Revised Edition). (E. Jephcott Trans.). Oxford, England: Blackwell Publishers. (Original work pub-lished 1939).

Emerson, R. (1971). Nature. In A. Ferguson (Ed.) Collected Works of Ralph

Waldo Emerson, Vol. 1. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard

University Press. (Original work published 1836).

Ezell, M. (1983/4). John Locke’s Images of Childhood. Eighteenth-century

Studies 17, 139-155.

Franklin, B. (1818). Advice to a Young Tradesman, written Anno 1748. In

Works of Benjamin Franklin (pp. 167-168). Philadelphia, PA: B.C.

Buzby. Archive of Americana, Early American Imprints, Series 2, no. 44072.

Franklin, B. (1987). Autobiography. In R. Bellah et al. (Eds.), Individualism

& Commitment in American Life: Readings on the Themes of Habits of the Heart (pp. 38-43). New York, NY: Harper & Row. (Original work

published 1793).

Fort, B. (2006). Greuze and the Ideology of Infant Nursing in Eighteenth-Century France. In A. Muller (Ed.), Fashioning Childhood in the

Eigh-teenth Century: Age and Identity (pp. 117-134). Burlington, VT: Ashgate

Publishing.

Foucault, M. (1970). The Order of Things: an archaeology of the human

sciences. New York, NY: Pantheon Books. (Original work published

1966).

Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and Punish: the birth of the prison. (A. She-ridan, Trans.) New York, NY: Pantheon Books. (Original work published 1975).

Foucault, M. (1991). The Foucault Effect – Studies in Governmentality:

With Two Lectures by and an Interview with Michel Foucault. Edited by

Graham Burchell, Colin Gordon, and Peter Miller. London: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Gallaudet, T. (1850). The Child’s Book on the Soul: Two Parts in One. New York, NY: American Tract Society).

Gordon, L. (1999). The Great Arizona Orphan Abduction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Haskell, T. (1985). Capitalism and the Origins of the Humanitarian Sensi-bility. In The American Historical Review vol. 90 (pp. 339-361; 547-566)

Heywood, C. (2007). Growing Up in France: from the Ancien Regime to the

Third Republic. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Hitchcock, E. (1790). Memoirs of the Bloomsgrove Family... Volume I. Bos-ton, MA: Thomas and Andrews. Early American Imprints, Series 1, no. 22570.

34

Houswitschka, C. (2006). Locke’s Education or Rousseau’s Freedom Alter-native Socializations in Modern Societies. In A. Muller (Ed.),

Fashion-ing Childhood in the Eighteenth Century: Age and Identity (pp. 81-88).

Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing.

James, J. (1816). The Sunday School Teacher`s Guide. New York, NY: J. Seymour.

Johnson, D. (2006). Engaging Identity: Portraits of Children in Late Eigh-teenth-Century European Art. In A. Muller (Ed.), Fashioning Childhood

in the Eighteenth Century: Age and Identity (pp. 101-116). Burlington,

VT: Ashgate Publishing.

Krupp, A. (2009). Reason’s Child: Childhood in Early Modern Philosophy. Lewisburg, NJ: Bucknell University Press.

Krupp, A. (2006). Observing Children in an Early Journal of Psychology: Karl Philipp Moritz’s FNQOIZAYTON (Know Thyself). In A. Muller (Ed.), Fashioning Childhood in the Eighteenth Century: Age and Identity (pp. 33-42). Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing.

Ladd-Taylor, M. (1995). Mother-work: Women, Child Welfare, and the

State, 1890-1930. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Lee, N. (2005). Childhood and Human Value: Development, Separation,

and Separability. New York: Open University Press.

Levander, C. (2006). The Cradle of Liberty: Race, the Child, and National

Belonging from Thomas Jefferson to W.E.B. Du Bois. Durham, NC: Duke

University Press.

Lissak, R. (1989). Pluralism and Progressives: Hull House and the New

Immigrants, 1890-1919. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Locke. J. (1996). Some Thoughts Concerning Education and of the Conduct

of the Understanding. Indianapolis, IN: Hackett Publishing, Inc.

(Origi-nal work published 1693 and 1706).

Luke, Carmen. (1989). Pedagogy, Printing, and Protestantism: The Dis-course of Childhood. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1989.

Marshall, D. (2008). Children’s Rights and Children’s Action in Interna-tional Relief and Domestic Welfare: The Work of Herbert Hoover be-tween 1914 and 1950. Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth 1, 351-388.

McCarthy, W. (1999). Mother of All Discourses: Anna Barbauld’s Lessons

McMillen, S. (1985). Mother’s Sacred Duty: Breast-feeding Patterns among Middle- and Upper-Class Women in the Antebellum South. The Journal

of Southern History 51, 333-356.

Martineau, H. (1861). Herod in the Nineteenth Century. In Health,

Husban-dry, and Handicraft (pp. 1-10). London, England: Bradbury and Evans.

(Original work published 1859).

Masur, L. (1991). Age of the First Person Singular: the vocabulary of the self in New England, 1780-1850. Journal of American Studies 25, 189-211.

Mintz, S. (2004). Huck’s Raft: a history of American Childhood. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Morton, M. (2000). Surviving the Great Depression: Orphanages and Or-phans in Cleveland. Journal of Urban History 26, 438-455.

Noel, M. (2002). America’s God: From Jonathan Edwards to Abraham

Lincoln. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Ozment, S. (1983). When Fathers Ruled: Family Life in Reformation

Eu-rope. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Patttison, R. (1978). The Child Figure in English Literature. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

Platt, A. (1969). The Child Savers: the invention of juvenile delinquency. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Plotz, J. (1979). The Perpetual Messiah: Romanticism, Childhood, and the Paradoxes of Human Development. In B. Finkelstein (Ed.) Regulated

Children/Liberated Children: Education in Psychohistorical Perspective

(pp. 63-95). New York, NY: Psychohistory Press.

Plotz, J. (2001). Romanticism and the Vocation of Childhood. New York, NY: Palgrave Press.

Reiner, J. (1982). Rearing the Republican Child: Attitudes and Practices in Post-Revolutionary Philadelphia. William and Mary Quarterly 39, 150-163.

Reiner, J. (1996). From Virtue to Character: American Childhood,

1775-1850. New York, NY: Twayne Publishers.

Rose, N. (1999). Governing the Soul: The Shaping of the Private Self. Second Edition. London: Free Association Books.

Rousseau. J. (1979). Emile or On Education. (A. Bloom Trans.) New York, NY: Perseus Books Group. (Original work published 1762).

Rush, B. (1965). Thoughts upon the Mode of Education, Proper in a Repub-lic. In R. Rudolph (Ed.) Essays on Education in the Early RepubRepub-lic.