CULTURE-LANGUAGES-MEDIA

Independent Project with Specialization in English

Studies and Education

15 Credits, First Cycle

English Vocabulary Acquisition through

MMOG/MMORPGs and other

Extramural Activities

Förvärv av engelsk vokabulär genom MMOG/MMORPG och andra

extramurala aktiviteter

Dino Kolenovic

Filip Nadjafi

Master of Arts in Upper Secondary Education, 300 credits and Secondary Education, 270 credits

English Studies and Education 2021-01-17

Examiner: Maria Graziano Supervisor: Jasmin Salih

Abstract

In a report by the Swedish Schools Inspectorate (Skolinspektionen, 2011), it was presented that extramural activities are not being used as a resource in formal education. It was also reported that the majority of English learned by the students was outside of school. The current paper investigates to what extent vocabulary acquisition is possible by playing MMOG/MMORPGs (Massively Multiplayer Online [Role-Playing] games) as an extramural English (EE) activity. However, not everyone wants to or can play computer games. Therefore, the paper further investigates how other EE activities can enhance English vocabulary and serve as an alternative to gaming. To answer our research questions, we analyse previous studies that have investigated the topic and relate it to the steering documents in a Swedish school context. The findings of this paper show that participants increase their vocabulary by collaborating and communicating with others when playing MMOG/MMORPG. Furthermore, other EE activities offer many options for English vocabulary acquisition by watching TV with captions or subtitles. Moreover, listening to audiobooks while reading increases literary words. It is difficult to determine what activity was the best for acquiring vocabulary. Therefore, further research could investigate what activity could be the most effective for vocabulary acquisition.

Keywords: Vocabulary, acquisition, English as a Second Language, English as a Foreign

Individual contributions

We hereby certify that the work of this essay reflects the equal participation of both authors. The parts being planning, searching for articles as well as writing the different parts of the paper.

Authenticated by:

Table of Contents

1. INTRODUCTION... 5

2. AIM & RESEARCH QUESTIONS ... 9

3. METHOD ... 10 3.1METHOD DELIMITATIONS... 10 3.2INCLUSION CRITERIA ... 10 3.3EXCLUSION CRITERIA ... 11 TABLE 1: ... 12 4. RESULTS... 13

4.1THE EFFECT MMOG/MMORPGS HAVE ON ESL VOCABULARY ACQUISITION ... 13

4.1.2.COMPARISONS OF HOW MMOG/MMORPGS AFFECT VOCABULARY ACQUISITION... 15

4.2EE ACTIVITIES AS ALTERNATIVES TO MMOG/MMORPG FOR ESL VOCABULARY ACQUISITION ... 17

4.2.1.OTHER FACTORS THAT POSITIVELY AFFECT VOCABULARY ACQUISITION ... 19

5. DISCUSSION ... 19

6. CONCLUSION ...25

1. Introduction

The syllabus for both English for secondary and upper secondary school in Sweden state that the English language surrounds us almost everywhere; furthermore, that knowledge of the language can help us in our daily lives (Skolverket, 2011a; Skolverket 2011b). Therefore, teachers must consider every way of how students obtain a language. Students are exposed to a great deal of the English language outside of the classroom when watching TV, listening to music or playing video games. Therefore, many opportunities for incidental language learning can happen through these activities. Sundqvist (2009) refers to these activities as Extramural English (EE) activities.

In 2019, 10.5% of students failed the English 5 National Test (Skolverket, 2019). If students’ interests are not used, students may lose the motivation to learn. Skolverket (2020) presents that good relationships between students and teachers are key for further language learning. For learning to happen, teachers must connect students’ out-of-school experiences with the classroom. However, the Swedish Schools Inspectorate found that EE often was a neglected source. Teachers in only 23 out of 293 schools were found to use students’ interests when creating assignments. Therefore, teachers could not show a logical connection between students’ out-of-school experiences and classroom learning (Skolinspektionen, 2011). In addition, Lundahl (2014) means that exposure to English in school is limited to a few hours per week and that EE is complementary to the type of English learned in school. Furthermore, the syllabus for English in secondary school states that ‘pupils should be given the opportunity to develop their skills in relating content to their own experiences, living conditions and interests’ (Skolverket, 2011a, p. 34). This highlights the need to further investigate EE activities as an ESL learning resource.

The syllabus for English in Secondary School states that students ‘should also be equipped to use different tools for learning, understanding, being creative and communicating’ (Skolverket, 2011a, p. 34). Furthermore, The National Curriculum for Upper Secondary School states that students are supposed to enhance knowledge about digitalisation and digital tools (Skolverket, 2013). These statements support engaging in EE activities to complement classroom learning, such as playing computer games or watching TV. These activities are both tools that can help students become exposed to different types of vocabulary.

The authors of this paper have observed in teacher practice periods that EE activities are also implemented in the classroom and used for creating vocabulary assignments. However, not to the extent that all students’ interests are considered. Researchers (Peterson, 2012; Sundqvist and Sylvén, 2014) agree that EE activities can promote vocabulary acquisition. Therefore, this paper will focus on to what extent the different activities promote vocabulary acquisition.

Having good vocabulary knowledge is important to be understood and to communicate in various forms. This is relevant for a Swedish secondary/upper secondary school context because students should be given the opportunity to develop their ability to ‘understand and interpret the content of spoken English and in different types of texts’ (Skolverket, 2011a, p. 34). Furthermore, it is stated that students should practice to ‘express themselves and communicate in speech and writing’ and ‘use language strategies to understand and to be understood’ (Skolverket, 2011a, p. 34). It is further stated that students ‘should adapt their language to different purposes, recipients and situations’ (Skolverket, 2011a, p. 34). Therefore, vocabulary knowledge is important when working with different forms of English, such as spoken or written.

Online gaming can be beneficial for further vocabulary acquisition. Peterson (2012) stated that positive outcomes were evident in research regarding students’ vocabulary acquisition and playing Massively Multiplayer Online (Role-Playing) games (MMOG/MMORPG). Thus, to narrow down our research, we investigated how MMOG/MMORPGs' impact ESL learners' vocabulary acquisition in secondary/upper secondary school in Sweden. MMOG/MMORPGs are open-world fantasy games where players play as different characters while communicating and collaborating with other players around the world to complete quests. Research has shown that the type of online interaction between non-native speakers and native speakers facilitates aspects of learning such as collaboration and communication (Peterson, 2012). Furthermore, the popularity of games as EE activities in Sweden can be seen through the annual gaming event Dreamhack, where 50,000 visitors attend every year (Jönköpings kommun, 2019). This further motivates choosing MMOG/MMORPGs as the focus of this paper.

Playing games can be beneficial in an educational context. Linge (2019) claimed that games have a natural place in language education if used correctly. Using games has several advantages in language education, where the greatest is that playing games are fun. Consequently, this can make language education more interesting and easier for both teachers and students. Further, Sundqvist and Sylvén (2014) show that digital games create opportunities for language learning to happen because (1) they are encouraging for young language learners and (2) they make players negotiate with one another when playing against

or with each other. Moreover, the collaborative part of MMOG/MMORPGsgoes in hand

with Vygotsky’s ideas. Vygotsky claimed that language learning takes place during social interaction and collaboration. He referred to this as the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). ZPD was defined as a zone where a person’s knowledge becomes greater with the help of

someone rather than learning on their own (Lighbown & Spada, 2013). Therefore,

MMOG/MMORPGs can be a resource for English vocabulary acquisition since players can communicate with native speakers of the target language (TL).

It can be necessary for teachers to think about students’ interests since extramural activities can promote incidental vocabulary acquisition (Lundahl, 2014). The cognitive learning theory shows how such learning occurs through EE activities by connecting it to how a learner receives input of information. This input happens when a learner is exposed to new words. The input is transformed into the intake. The transformation is viewed as the process of negotiation between the learner’s new language and old (Lundahl, 2014, p. 200).

Only resorting to MMOG/MMORPGs for vocabulary acquisition can be problematic; therefore, other interests have to be thought of for inclusive education. Students often play digital games or engage in other EE activities in their spare time when they are not actively learning a language (Sundqvist & Olin-Schneller, 2013). However, the uses and potential success of EE as a complement to English taught in the classroom are often dependent on what conditions students face outside of school. Because of socio-economic differences, not everyone can afford computer games. Furthermore, every student has different interests and may not find gaming motivating or interesting. Skolverket (2011a; 2011b) states that education should be equivalent and that the school must look after every students’ needs and interests. It can be difficult to determine when education is equivalent because equivalency is a broad definition. Therefore, teachers must always think about students’ different interests

Consequently, teachers must consider alternatives to gaming in order to meet students’ needs. Therefore, we further want to investigate if there are other extramural activities that students may benefit from to boost their vocabulary learning.

The paper will investigate to what extent EE activitiesimpact vocabulary in a secondary and

upper secondary L2/ESL/EFL context. L2 stands for a language that is learnt as a secondary language. EFL (English as a Foreign Language) and ESL (English as a Second Language) mean that students learn English in a country where it is not the primary language. EFL is taught in a country where English is not an official language. ESL is similarly taught in a country where English is not an official language. However, the term ESL is most often used in countries where English is commonly used or in countries with higher English proficiency. The studies that we will summarise in this paper did not often make a difference between EFL and ESL. Therefore, we chose to use the term ESL to avoid confusion.

2. Aim & Research Questions

While researchers agree that playing games can be beneficial for language learning, EE

activities are seen as an unused resource. This problem led us to investigate how

MMOG/MMORPGs can be useful for vocabulary acquisition in an ESL environment, focusing on secondary/upper secondary students. However, all students may not be able to play these games or have a greater interest in other activities. As a result, teachers must provide alternatives to make education meaningful to all students. Therefore, we will further investigate how other EE activities impact ESL students’ vocabulary acquisition.

To achieve this, we ask the following research questions:

• To what extent can MMOG/MMORPGs promote ESL vocabulary acquisition?

• What other types of EE activities can similarly further promote vocabulary

3. Method

In our research, we used several databases for retrieving the necessary sources to answer our research questions. The database of Malmö University was used for this purpose, as well as other educational databases, to access peer-reviewed studies and articles.

3.1 Method Delimitations

We conducted initial searches on Google Scholar to find relevant studies. It was difficult to determine if studies found on Google Scholar were peer-reviewed; therefore, we searched for the same articles on EBSCO or ERIC. A search on Google Scholar with the keywords ‘MMOG’, ‘Vocabulary Acquisition’ ‘L2’ and ‘Extramural English’ gave us 220 articles and studies. By adding ‘MMORPG’ we found 78 results. On the databases EBSCO and ERIC, we found even fewer results with the same combination of keywords. This led us to shorten and change the combinations of keywords on the databases until relevant studies were acquired and used for this research. We found a total of 19 studies by changing keyword combinations. Of the 19 studies, we found that 12 were relevant for both of our research questions. The used studies in this paper will be presented in a table in Table 1.

These keywords were used in different combinations for a wide range of articles to find the necessary studies:

‘MMOG’, ‘MMORPG’, ‘vocabulary acquisition’, ‘language strategies’, ‘ESL’, ‘EFL’, ‘L2’, ‘second language learning’, ‘English’, ‘incidental learning’, ‘extramural English activities’, ‘reading’, ‘listening’, ‘television’, ‘movies’

3.2 Inclusion Criteria

Studies on the subject area come from different countries and contexts, and the participants vary in the proficiency of the English language. We found that there are not that many studies that focused on just ESL, which is why we chose to include studies conducted in an EFL environment as well. The studies that we chose to include in this paper often referred to both ESL and EFL as a second language. As a result, it became difficult for us to separate

ESL and EFL. We chose to include L2, ESL and EFL as keywords to find more articles that were relevant for this paper. However, only the abbreviation ESL will be used when referring to English as a second or foreign language in the text. Furthermore, many studies related to the first research question seemed to use MMOG and MMORPG interchangeably. MMORPG was often seen to be a sub-category of MMOG. Therefore, we chose to include both terms as keywords when looking for relevant articles. The ages of the studies’ participants ranged between ten-year-old and university-level students. We chose to include studies in this age range because it is not too far away in age from our target group of secondary and upper secondary students (i.e., a few years younger or older). We included studies made between 2006 and 2020 because many MMOG/MMORPGs were released in the early 2000s. Furthermore, we decided that it was relevant to include current studies because of the growing media popularity.

3.3 Exclusion Criteria

Some studies were excluded based on the publication date. Other studies that also seemed interesting focused more on general gaming, which meant that they would become too broad for this paper. Moreover, some studies on MMOG/MMORPGs were excluded because they focused on how MMOG/MMORPGs impacted loneliness and anxiety among learners. We also excluded studies that focused on MMOG/MMORPGs from the perspective of student motivation because the dimension of vocabulary was not in focus.

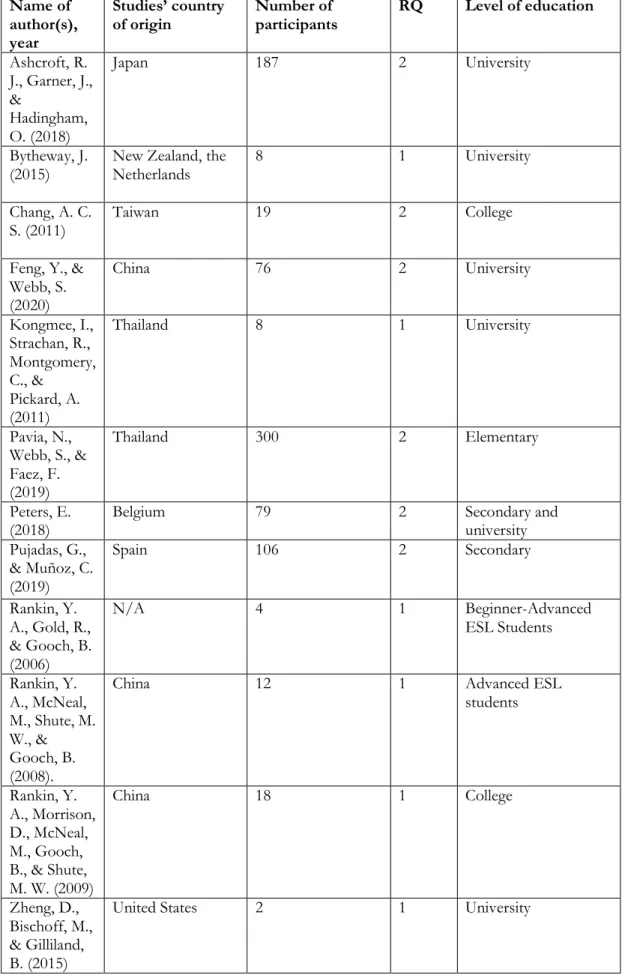

Table 1:

Name of author(s), year

Studies’ country

of origin Number of participants RQ Level of education

Ashcroft, R. J., Garner, J., & Hadingham, O. (2018) Japan 187 2 University Bytheway, J.

(2015) New Zealand, the Netherlands 8 1 University

Chang, A. C.

S. (2011) Taiwan 19 2 College

Feng, Y., & Webb, S. (2020) China 76 2 University Kongmee, I., Strachan, R., Montgomery, C., & Pickard, A. (2011) Thailand 8 1 University Pavia, N., Webb, S., & Faez, F. (2019) Thailand 300 2 Elementary Peters, E.

(2018) Belgium 79 2 Secondary and university

Pujadas, G., & Muñoz, C. (2019) Spain 106 2 Secondary Rankin, Y. A., Gold, R., & Gooch, B. (2006) N/A 4 1 Beginner-Advanced ESL Students Rankin, Y. A., McNeal, M., Shute, M. W., & Gooch, B. (2008).

China 12 1 Advanced ESL

students Rankin, Y. A., Morrison, D., McNeal, M., Gooch, B., & Shute, M. W. (2009) China 18 1 College Zheng, D., Bischoff, M., & Gilliland, B. (2015)

4. Results

As mentioned, this paper aims to investigate the effect of MMOGs/MMORPGs and other EE activities have on ESL vocabulary acquisition. Firstly, the studies related to the first research question will be summarised and synthesised. Secondly, the studies related to the second research question will be summarised and synthesised.

4.1 The effect MMOG/MMORPGs have on ESL

vocabulary acquisition

In a study from Thailand, Kongmee et al. (2011) investigated how MMOG/MMORPGs affected eight undergraduate students’ English vocabulary. The students played the games

Godswar, Asda Story and Zentia. The students learned about the games by visiting official

websites and fan pages in English while given real-world tasks alongside the virtual tasks in the games. The virtual tasks were supposed to give students the necessary opportunities to develop vocabulary. The students took a multiple-choice test before and after playing to measure the impact of vocabulary acquisition. The tests covered three English skills: vocabulary, grammar and listening. The results from the posttest indicated numerous improved parts of the students’ vocabulary as a result of collaborating. The authors concluded that MMORPGs can provide a fun and informal setting in which learning can take place by collaborating with other players.

Similarly, Julie Bytheway (2015) investigated how the use of autonomous learning strategies could affect students' English vocabulary. The participants came from Germany, Ukraine, Malaysia, Vietnam and China. The participants played World of Warcraft (WoW), where English was the lingua franca. The researcher observed and recorded the participants for a total of five hours. Afterwards, the participants were interviewed for a total of six hours. In these interviews they were asked what strategies they used to acquire new vocabulary. As a result, Bytheway (2015) found 15 learning strategies of both formal and informal ways of learning new English vocabulary. The most commonly used learning strategy was interaction with other players of higher English proficiency. This strategy helped students practice and

recognize new vocabulary. Thus, Bytheway (2015) concluded that playing

MMOG/MMORPGs can benefit a student’s vocabulary acquisition.

Another study that investigated the impact MMOG/MMORPGs have on English vocabulary acquisition was Zheng et al. (2015). The researchers investigated whether the gameplay of World of Warcraft affected a non-native English speaker’s (NNS) vocabulary. The NNS played together with a native English speaker (NS). The participants only played for a total of two hours, where the researchers analysed the in-game communication between the participants. The results showed that the NNS expanded his vocabulary while playing WoW. This was made possible by utilizing and actively collaborating with the NS to better understand the meaning of vocabulary. The researchers argue that the NNS would not be given the same opportunity to improve vocabulary in a traditional classroom context. Furthermore, the researchers showed that this extramural activity gave the NNS problem-solving and linguistic skills.

Rankin, Gold et al. (2006) also investigated the use of MMOG/MMORPGs for vocabulary

acquisition. The participants played the MMOG/MMORPG Ever Quest 2 for four weeks.

They communicated with other playable characters (PCs) that were controlled by other players. Furthermore, participants communicated with pre-programmed characters (NPCs) that appeared in the game. However, these characters are controlled by the game and cannot be controlled by other players. The communication was conducted through a chat system. The participants first answered a pre-game questionnaire expressing their ESL knowledge. The researchers wrote observational diaries from each gaming session and asked for feedback about the experiences. During gameplay, students explained how to complete tasks. Afterwards, the participants answered a questionnaire, where their language use was compared to the language the participants used in the game. The results indicated vocabulary development; therefore, the researchers tested the vocabulary knowledge based on game log activities and interactions with NPCs. The results indicated that participants more easily defined vocabulary that often appeared in the game. Thus, the researchers concluded that communication with both PCs and NPCs offer opportunities for vocabulary acquisition that rarely occurs in ESL education.

Similarly, Rankin, McNeal, et al. (2008) found factors from MMOG/MMORPGs that enhanced students’ vocabulary. They stated that MMOG/MMORPGs are an unorthodox tool for social interaction, which could improve vocabulary. The participants were advanced ESL students who played with NS and other NNS. One group of participants played with NS and the other with NNS. The study investigated if the students could define vocabulary

in sentences correctly. Firstly, all students were tested on academic words unrelated to the game. Secondly, the students were tested on in-game vocabulary from the MMOG/MMORPG that they played during the study. The virtual identity that the students created allowed them to make mistakes in their interaction with NS and more proficient English speakers. The anonymity of creating a virtual identity gave the participants

confidence to interact more with other players, resulting in improved vocabulary.The group

that interacted with the NS performed better than the group that did not interact with NS. The authors found that MMOG/MMORPGs can facilitate opportunities for vocabulary acquisition and that the opportunities are especially important when the interaction in the game is between NNS and NS.

A similar study made by Rankin, Morrison et al. (2009) also investigated whether MMORPGs could foster second language acquisition through communication with NS. A total of 18 Mandarin-speaking college students have divided into three groups: one had normal classroom education, another played Ever Quest 2 alone and the third played with NS. Beforehand, all participants were assessed on in-game vocabulary through three pre-game tests, where the results were low. However, the results from the post-test indicated increased results specifically for the gaming students. Students that collaborated with NS outperformed both of the other groups. The authors found that player communication enhanced understanding of ESL vocabulary. Although classroom learning is useful for ESL vocabulary acquisition, the results indicated that MMOG/MMORPGs could be useful for language learning because of the communication with NS.

4.1.2. Comparisons of how MMOG/MMORPGs affect vocabulary

acquisition

The research from the above studies seems to agree on what mostly affects vocabulary acquisition from playing MMOG/MMORPGs. The studies all found that MMOG/MMORPGs offer great opportunities for participants to acquire new vocabulary thanks to the collaborative opportunities. However, there were some differences to what extent. For example, Rankin, Gold et al. (2006), Rankin, McNeal et al. (2008) and Rankin, Morrison et al. (2009) found that the participants developed new vocabulary thanks to the help they received from native speakers. Although, there were also some differences in what would be necessary for vocabulary acquisition to happen. For example, Rankin, Gold et al.

intermediate level of English proficiency. This contradicts the findings from the other studies that did not see this as a factor for vocabulary to be acquired. Furthermore, the validity of the results could be questioned based on a few aspects: the participants’ proficiency level differed, the number of participants were few and the study was conducted for only a short period of time. However, the findings from Rankin, Gold et al. (2006) still indicated positive results that contributed to the generalisation. The above studies would also contradict the findings from the other studies because they examined players that played alone and did not collaborate with others. MMOG/MMORPGs were also effective for vocabulary acquisition when playing with NPCs (Rankin, Gold et al., 2006; Rankin, McNeal et al., 2008; Rankin, Morrison et al., 2009). However, while collaboration with others seemed to be most effective for vocabulary acquisition (Rankin, McNeal et al., 2008; Rankin, Morrison et al., 2009), the difference was not shown in Rankin, Gold et al. (2006).

In contrast to the previous studies, Kongmee et al.’s (2011) study focused on three different games. This could have affected the amount of vocabulary the participants were exposed to. Although Zheng et al.’s (2015) study showed some positive results, the authors only examined one NNS and one NS for only a few hours. The length of this study could once again make the results questionable. However, similarly to Rankin, Gold et al. (2006), the positive results still contributed to the generalisation of collaborating with others for vocabulary acquisition. In contrast to all other studies regarding playing with native speakers, Bytheway (2015) found that it was not necessary to collaborate with native speakers to acquire new vocabulary. She concluded that it was sufficient enough if the participants collaborated with someone of higher English proficiency than themselves. However, one thing has to be considered regarding this finding. The participants in the study were of different nationalities. As a result, the need to communicate with a NS may have differed since the general proficiency level between participants’ countries may vary. In contrast to the studies above, Bytheway (2015) further showed that participants not only learned new vocabulary but slang and abbreviations as well.

The results indicated that all authors agreed that collaborating with other players led to improved vocabulary; however, Bytheway’s (2015) findings differed from the others regarding playing with an NS or not. Furthermore, it was shown that MMOG/MMORPGs improved vocabulary through interacting with NPCs (Rankin, Gold et al., 2006; Rankin, McNeal et al., 2008; Rankin, Morrison et al., 2009).

4.2 EE activities as alternatives to MMOG/MMORPG for

ESL vocabulary acquisition

Ashcroft et al. (2018) investigated if watching movies as an EE activity could enhance English vocabulary. The participants were 187 Japanese undergraduate university students aged 18-23. The students were split into an experimental group and one control group. The students in the experimental group were asked to watch the movie Back to the Future with captions and the control group received no treatment. All students took a vocabulary test before the study began. The students took an identical test to measure the potential vocabulary gains after the experimental group finished the movie. The researchers found that the students in the experimental group gained some new incidental vocabulary by watching the movie with captions; however, to a limited extent. Although the post-test indicated some positive results, the researchers found that repetition of vocabulary would be most useful for acquiring new vocabulary.

In a similar study, Pujadas and Muñoz (2019) also researched to what extent watching a TV-series impacted vocabulary acquisition. The participants were 106 eighth-graders from a secondary school in Barcelona that were divided into four groups. During the study, the participants watched 24 consecutive episodes over three terms. The participants first took a vocabulary proficiency test of form and meaning before watching the TV-series. The students took an identical vocabulary test to measure progress after watching the first eight episodes during the first term. The same procedure was done in the following two terms. The participants answered a questionnaire after watching all episodes. The results from the study indicated that vocabulary gains were evident in all of the four groups. However, the most significant gains were made in the group watching with captions and received pre-instruction of vocabulary. The second group that watched the series with subtitles and received pre-instructions had the second-best results. The findings indicate that vocabulary acquisition was made possible by repeatedly being exposed to vocabulary in the TV-series. In contrast to the previously mentioned studies, Pavia et al. (2019) investigated a different EE activity. They investigated how ESL learners could learn new vocabulary incidentally through song listening. The study was made on 300 Thai students aged 10-14. First, all participants took a vocabulary test. Afterwards, the participants were divided into experimental groups and one control group. The study consisted of two songs that the

participants heard for a total of five weeks. They were assessed on three things: Spoken-form recognition, form-meaning connection and collocation recognition, where the test consisted of multiple-choice questions. During the study, the participants did a post-test, and at the end, they completed a delayed post-test. The results indicated that song listening enhanced vocabulary. Listening to songs multiple times helped vocabulary gains and exposure frequency impacted learning gains. Thus, the study showed that repetition was necessary for incidental ESL vocabulary learning.

Chang (2011) aimed to see how vocabulary was acquired from reading while listening to audiobooks. She conducted a study for 26 weeks during two terms on Taiwanese secondary students, aged 15 to 16. The participants of the study were divided into two groups. One group read while they listened to audiobooks (RWL) and the other group read various short stories out loud to each other (control group). The control group was assessed on various tests during the study, such as re-telling the story or identifying words that were missing when listening to the story again. However, the RWL-group just kept on reading various books. All participants took a test to measure their vocabulary acquisition at the end of the study. The results indicated that students who listened to audiobooks while reading improved more on the vocabulary tests. The findings showed that listening to audiobooks while reading can be a useful resource for ESL vocabulary acquisition.

Feng and Webb (2020) investigated how different input modes from one source affected ESL vocabulary acquisition. A total of 76 Chinese university students, aged 19 to 21, took part in the study where they watched a documentary. To measure differences, they were divided into four groups. Each group was given the input from the same television documentary through different modes. One read the transcript, one listened to the documentary and one watched the documentary. The final group was a control group that did not receive any treatment. A multiple-choice vocabulary test was made before watching the documentary. The participants took an immediate vocabulary test after the treatment. They were tested on their recognition of words from the documentary. Results showed that all three mode groups developed their vocabulary with no significant difference between them; however, the control group got decreased results. Feng and Webb (2020) claimed that the results for the three mode groups were an indication that all input modes could be a way to acquire new vocabulary.

years old. The study measured what types of EE activities the students engaged in the most; furthermore, what impact this had on their vocabulary. Peters (2018) determined that positive effects were found by watching TV and movies both with subtitles and without by administering a questionnaire and a proficiency test. Furthermore, it was determined that the university students performed better, indicating that the length of exposure to English also affected the vocabulary.

4.2.1. Other factors that positively affect vocabulary acquisition

Providing alternatives to MMOG/MMORPGs is important to include students who are not interested in these games. As a result, more students could take part in EE activities. Therefore, the above studies investigated to what extent other EE activities impacted vocabulary acquisition. There seems to be some agreement on what factors are necessary for vocabulary acquisition through different EE activities.

Most of the studies seem to agree on the fact that repetition and frequency of exposure were key aspects to obtaining new vocabulary regardless of what activity it was. The studies from Ashcroft et al. (2018) and Pujadas and Muñoz (2019) both found that watching TV affected vocabulary acquisition thanks to the dual input of captions or subtitles while watching. This dual input could be seen as a form of repetition because participants became more exposed to vocabulary simultaneously. However, the results differed on some points. While both studies found that watching TV with captions was the best alternative, Pujadas and Muñoz (2019) further found that subtitles were also effective. One has to consider that Ashcroft et al. (2018) did not include that aspect in their study. The results from that study may have indicated different outcomes if subtitles were included as an option. Even though they found two different important aspects, they similarly concluded that the results were mostly dependent on repetition. Although Pavia et al. (2019) and Chang (2011) conducted different studies, they both found the amount of exposure to be most effective for vocabulary acquisition. As a result, their findings further strengthen the assumption of how necessary repetition is for vocabulary acquisition. Chang’s (2011) results also indicated a dual input of reading and using audiobooks to be effective for learning literary words, similar to Ashcroft et al. (2018) and Pujadas and Muñoz (2019). Chang’s (2011) study was also conducted for a long period, which gave participants time for vocabulary exposure. However, one has to consider that the activities between the experimental group and the control group in Chang’s (2011) study differed very much. The length of the study may have affected the significant

difference between the groups. The aspect of frequent exposure or repetition was also found in Peter’s (2018) study. However, Peter’s (2018) results indicated more correlations between watching TV without subtitles; therefore, the results contradict the aspect of dual input as frequent exposure. Furthermore, one thing that has to be considered is that Peters (2018) found that older participants were more exposed to TV in general than the younger participants. This may have affected the results of the study.

Similarly, the other studies all showed benefits from various activities. However, Feng and Webb (2020) concluded that there was not much of a difference between reading, watching and listening. In contrast to all of the other studies that found repetition and exposure amount to be most beneficial, Feng and Webb (2020) found a positive correlation between prior knowledge and vocabulary acquisition. One important aspect to consider is that this study was not conducted for a long period. Therefore, the results and important aspects may have differed if they conducted a longer experiment. Even so, the findings from Feng and Webb (2020) still contributed to the generalisation of the results regarding various activities for vocabulary acquisition.

The results showed that various activities such as watching TV, using audiobooks or listening to songs while reading positively affected vocabulary acquisition. The studies mostly agreed that the biggest factor was when the activities were done repetitively. However, Feng and Webb (2020) found prior knowledge to be more important, which contradicts the findings from the other studies.

5. Discussion

The findings of the studies led us to renewed insight regarding how and to what extent

vocabulary is acquired through EE activities. As Lundahl (2014) argues, EE is

complementary to English learned in school. Therefore, these activities can provide students with great opportunities to expand their language knowledge outside of school. Furthermore, previous research showed that EE activities provided opportunities for incidental vocabulary acquisition (Sundqvist & Olin-Schneller, 2013) or that the social environment of playing MMOG/MMORPGs improved learners’ vocabulary (Peterson, 2012; Sundqvist & Sylvén, 2014). All studies in this paper seemed to agree that collaboration with other players was the most important factor for vocabulary acquisition. This was seen in Rankin, McNeal et al. (2008) and Rankin, Morrison et al. (2009), where participants who collaborated with others developed their vocabulary more than those who played alone. These findings aligned with both previous research and the socio-cultural theory that claimed that people develop their language knowledge easier with the help of someone (Lightbown and Spada, 2013).

Furthermore, participants who played MMOG/MMORPGs with NPCs processed all information while negotiating with themselves to understand their thinking. This enabled participants to acquire vocabulary when reading the in-game language from NPCs (Rankin, Gold et al. 2006). These findings corresponded with the cognitive theory regarding how one could obtain language by becoming aware of your knowledge through inner speech (Lundahl, 2014, p. 202). Furthermore, results from Ashcroft et al. (2018), Pujadas and Muñoz (2019), Pavia et al. (2019) and Chang (2011) indicated that the cognitive theory could further be applied to other EE activities. Learner’s vocabulary acquisition improved by repetitively watching TV, reading and listening to songs. This repetitive factor is aligned with how learners receive an intake of information and actively negotiate with themselves to create new implicit knowledge (Lundahl, 2014, p. 200). Consequently, students could be deprived of incidental learning opportunities without frequent exposure to the TL.

Statements in the syllabuses showed that it is necessary for students to practice their skills in being able to adapt their language to aim, situation and recipient (Skolverket, 2011a; Skolverket, 2011b). Therefore, MMOG/MMORPGs could provide excellent opportunities for this purpose. The findings regarding MMOG/MMORPGs showed that players had to

constant communication led participants to think of what language they used when they expressed themselves. However, all these activities are seen as extramural; therefore, they are not meant to be done in the classroom. The findings from the studies this paper has examined showed a great opportunity for vocabulary acquisition to take place. Therefore, teachers must think of ways of how to get their students engaged in these types of activities. One way of engaging students in extramural activities is if teachers implemented different aspects from the activities into the classroom. Consequently, teachers could help their students to become more motivated to use English extramurally.

There are many opportunities for teachers to commit students to be a part of the communicative classroom of English. However, teachers seem to find it difficult to include all students. Skolverket (2019) showed that approximately 10% of students failed the English National Test in English 5, which could point towards the lack of vocabulary knowledge among students. Furthermore, it was shown that teachers often did not use students’ interests when creating assignments (Skolinspektionen, 2011). As a result, students might be deprived of opportunities to increase their vocabulary. Since the results of this study indicated that there were multiple ways of increasing vocabulary through different activities, teachers should not let opportunities to implement aspects go to waste. Skolverket (2020) found that good teacher-student relationships were necessary for language learning. If teachers implemented different aspects of extramural activities, good teacher-student relationships could be created. Furthermore, implementing aspects from EE activities could help students see a connection between English outside of school and in school, which Lundahl (2014) saw as complementary parts. The implementation of these aspects could therefore bridge the gap between English in school and outside school. Teachers can implement the collaborative and communicative part that MMOG/MMORPGs provided. One aspect could be roleplaying, where students could choose characters to roleplay as. Teachers would then think of students’ interests and making students more engaged, which was often not the case in the report from The Swedish Schools Inspectorate (Skolinspektionen, 2011).

Furthermore, Bytheway’s (2015) results indicated that teachers could pair students together regarding their English-speaking proficiency. This collaborative aspect also aligned with the socio-cultural theory of developing language knowledge with the help of someone. By implementing these aspects, teachers could show students where the aspects are taken from

and therefore motivate students to use activities outside of school for extramural learning. The implementation also of those aspects works in support of Linge's (2019) claims, where using games in class could provide a fun way of developing new vocabulary.

Concerning other EE activities, the aspects that provided incidental vocabulary could also be implemented in the classroom. As mentioned, we have during our teacher practice periods observed how teachers created assignments relating to various activities. The use of television in classroom activities was often implemented; however, students usually preferred to watch with Swedish subtitles rather than with English subtitles. As a result, students might be more focused on translation than the actual speech. One could argue that this leads to missed opportunities for vocabulary acquisition to happen, especially since findings from Ashcroft et al. (2018) and Pujadas and Muñoz (2019) showed that using subtitles was useful for obtaining new vocabulary. Teachers could therefore use the aspect of only using TL subtitles when watching TV in school. Consequently, this would affect the communicative classroom because only TL is being used. Furthermore, it could even be good to just focus on the speech, which Peters (2018) found useful for vocabulary acquisition. It could be good if this matter was introduced to make students more engaged in doing the same when watching at home. The use of songs was not observed by the authors of this paper during their teaching practice. However, Pavia et al. (2019) saw this as an effective tool for vocabulary acquisition. Therefore, song listening could become useful for vocabulary acquisition if teachers implemented songs and encouraged students to listen to more songs in English. This aspect would also relate to statements from the National Curriculum regarding that English most often should be taught in the TL (Skolverket, 2011b).

Furthermore, it could be useful to think of the findings from Chang’s (2011) study when considering using books in school. Students may not find it fun to read; however, Chang (2011) found that listening improved reading. Therefore, teachers could implement the listening aspect when creating book assignments in school. It could be useful to play the audio beforehand as a way to use scaffolding when reading shorter texts. This implementation could make it easier for students with reading difficulties to understand texts better. Furthermore, teachers could encourage students to use audiobooks as a complement to their reading. Consequently, students with difficulties could also find reading beneficial. In addition, Feng and Webb (2020) showed that there were no significant differences between reading or listening. Therefore, students could choose if they prefer to read while

listening or only listen to an audiobook. Teachers who implement these activities further strengthen the possibility of an equivalent education for students. As a result, this would support statements regarding an equivalent education (Skolverket, 2013; Skolverket, 2018). The findings from Feng and Webb (2020) could give students more options to increase vocabulary, which is important when expressing oneself in the communicative classroom. The implementation of these aspects would also support the statements from Skolverket (2011a) regarding expressions through speech and writing in a communicative classroom.

Making education equivalent must be a priority. This study provided findings regarding what extent different extramural activities impact English vocabulary acquisition. Teachers can more easily meet students’ needs to develop vocabulary if various aspects are implemented into the classroom. All activities showed different ways of how vocabulary could be acquired; however, it was difficult to determine which activity was the best alternative to use.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, this paper aimed to investigate how and to what extent EE activities improve

English vocabulary. The studies that this paper chose to include have mainly focused on

MMOG/MMORPGs. Furthermore, the secondary focus was on various EE activities. The findings indicated that MMOG/MMORPGs increased students’ vocabulary because students had to collaborate and communicate with native speakers. However, it was also shown to be beneficial when communicating with someone of higher proficiency. Furthermore, interaction with NPCs was also effective for vocabulary acquisition but not to the same extent as collaborating with others. Other findings indicated that watching TV with captions and subtitles was also beneficial for learners’ vocabulary acquisition. Furthermore, the necessity of repetition was key for further vocabulary acquisition. Moreover, song listening and using audiobooks while reading were two other activities that positively impacted vocabulary due to repetition and frequent exposure. In addition to how vocabulary was acquired, this paper provided examples of how teachers can implement different aspects of the activities into the classroom. Teachers could implement roleplaying in communicative and collaborative assignments or encourage the use of TL subtitles when watching TV. These aspects are alternatives that teachers could use to help build relationships with students and relating the content to students’ experiences.

The limitations of this paper are that the participants’ age, proficiency level and nationality in the examined studies varied. Furthermore, the length of the studies also varied, which could have affected the results. This paper also did not include a study that compared several EE activities against each other, except for Feng and Webb (2020). As a result, it became difficult to determine what activity promoted vocabulary acquisition the most. However, since the activities provided different aspects of vocabulary acquisition, they could be used by teachers to bridge the gap between EE and classroom education. Despite the limitations, the findings indicated vocabulary acquisition for many ages; therefore, we believe that the findings apply to a secondary/upper secondary context.

Further research regarding what extramural activity is most effective for vocabulary acquisition is needed. A potential research for a coming degree project could be to investigate to what extent different EE activities affect vocabulary acquisition on Swedish secondary and upper secondary students.

7. References

Ashcroft, R. J., Garner, J., & Hadingham, O. (2018). Incidental Vocabulary Learning through Watching Movies. Australian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 1(3), 135 -147. Retrieved at 2020-12-08 from:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330298124_Incidental_Vocabul ary_learning_through_Watching_Movies

Bytheway, J. (2015). A taxonomy of vocabulary learning strategies used in massively multiplayer online role-playing games. calico journal, 32(3), 508-527. Retrieved at 2020-11-14 from:

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0346251X15000433?v ia%3Dihub

Chang, A. C. S. (2011). The Effect of Reading While Listening to Audiobooks: Listening Fluency and Vocabulary Gain. Asian Journal of English Language

Teaching, 21. Retrieved at 2020-12-08 from: https://eds-a-ebscohost

com.proxy.mau.se/eds/detail/detail?vid=0&sid=0bad9419-2dab-492b-9bbc c9178c5149da%40sessionmgr4007&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmUm 2NvcGU9c2l0ZQ%3d%3d#AN=70706386&db=ehh

Feng, Y., & Webb, S. (2020). Learning vocabulary through reading, listening, and viewing: Which mode of input is most effective?. Studies in Second Language

Acquisition, 42(3), 499-523. Retrieved at 2020-12-08 from: https://www

-cambridge-org.proxy.mau.se/core/services/aop-cambridge-

core/content/view/415CF118C5A114BB2D9C3B79B9656AFF/S0272263 11900494a.pdf/learning-vocabulary-through-reading-listening-and-viewing -which-mode-of-input-is-most-effective.pdf

Jönköpings kommun. (2019). Dreamhack Winter. Retrieved at 2020-11-11 from https://jkpg.com/sv/jonkoping-huskvarna/dreamhack-winter/ Kongmee, I., Strachan, R., Montgomery, C., & Pickard, A. (2011). Using massively

multiplayer online role playing games (MMORPGs) to support second language learning: Action research in the real and virtual world. Retrieved at 2020-12-01 from https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Using-massively

Linge, O. (2019). Spel som ett verktyg för undervisning i språk. Lingua, 2019(2), 18-22. Retrieved at 2020-12-12 at:

https://www.spraklararna.se/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/spel_och_sprak_1902.pdf

Lightbown, P. M., & Spada, N. (2013). How languages are learned 4th edition-Oxford Handbooks

for Language Teachers. Oxford university press.

Lundahl, B. (2014). Engelsk språkdidaktik: Texter, kommunikation, språkutveckling. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Pavia, N., Webb, S., & Faez, F. (2019). Incidental vocabulary learning through listening to songs. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 41(4), 745-768. Retrieved at 2020-12-08 from:

https://www-cambridge-org.proxy.mau.se/core/services/aop-cambridge

core/content/view/24418DF071558AE40C2D429B6868F8B9/S02722631 1900020a.pdf/incidental-vocabulary-learning-through-listening-to-songs.pdf Peters, E. (2018). The effect of out-of-class exposure to English language media on

learners’ vocabulary knowledge. ITL-International Journal of Applied

Linguistics, 169(1),142-168. Retrieved at 2020-12-08 from:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/324545147_The_effect_of_out -of

class_exposure_to_English_language_media_on_learners'_vocabulary_kno wledge

Peterson, M. (2012). Learner interaction in a massively multiplayer online role playing game (MMORPG): A sociocultural discourse analysis. ReCALL, 24(03), 361-380. Retrieved at 2020-11-16 from

https://www-cambridge-org.proxy.mau.se/core/journals/recall/article/learner-interaction-in-a massively-multiplayer-online-role-playing-game-mmorpg-a-sociocultural discourse-analysis/47512049EFFC60C2C8C01C75A176518A

Pujadas, G., & Muñoz, C. (2019). Extensive viewing of captioned and subtitled TV series: A study of L2 vocabulary learning by adolescents. The Language Learning

Journal, 47(4), 479-496. Retrieved at 2020-12-08 from: https://www

tandfonline

com.proxy.mau.se/doi/pdf/10.1080/09571736.2019.1616806?needAccess= true

Rankin, Y. A., Gold, R., & Gooch, B. (2006). 3D role-playing games as language learning tools. Eurographics (Education Papers), 25(3), 33-38. Retrieved at 2020-11-11 from https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/3D-Role-Playing-Games-as

-Language-Learning-Tools-Rankin-Gold/273d1b6216069f85091da1b69f9ce4d02b65c0c8

Rankin, Y. A., McNeal, M., Shute, M. W., & Gooch, B. (2008, August). User centered game design: evaluating massive multiplayer online role playing games for second language acquisition. In Proceedings of the 2008 ACM SIGGRAPH

symposium on Video games (pp. 43-49). Retrieved at 2020-11-17 from

https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/User-centered-game-design%3A

-evaluating-massive-role-Rankin-McNeal/09eb47eb8f1e4d01c38e55239a51b60433b7566e

Rankin, Y. A., Morrison, D., McNeal, M., Gooch, B., & Shute, M. W. (2009, April). Time will tell: In-game social interactions that facilitate second language

acquisition. In Proceedings of the 4th international conference on foundations of digital

games (pp. 161-168). Retrieved at 2020-11-17 from

https://dl-acm-org.proxy.mau.se/doi/epdf/10.1145/1536513.1536546

Skolinspektionen (2011). Engelska i grundskolans årskurser 6-9. Kvalitetsgranskning. Rapport 2011:7. Retrieved at 2020-12-03 from

https://www.skolinspektionen.se/beslut-rapporter

statistik/publikationer/kvalitetsgranskning/2011/engelska-i-grundskolans arskurser-69/

Skolverket. (2011a). Läroplan för grundskolan - Ämne engelska. Retrieved at 2020-11-11 from https://www.skolverket.se/undervisning/grundskolan/laroplan-och kursplaner for-grundskolan/laroplan-lgr11-for-grundskolan-samt-for forskoleklassen-och fritidshemmet?url=1530314731%2Fcompulsorycw%2Fjsp%2Fsubject.htm %3 subjectCode%3DGRGRENG01%26tos%3Dgr&sv.url=12.5dfee44715d35 a5cd a219f

Skolverket. (2011b). Läroplan för gymnasiet – Ämne engelska. Retrieved at 2020-11-11 from https://www.skolverket.se/undervisning/gymnasieskolan/laroplan program-och amnen-i

%2Fjsp%2Fsubject.htm%3FsubjectCode%3DENG%26lang%3Dsv%26to s%3gy%26p%3Dp&sv.url=12.5dfee44715d35a5cdfa92a3#anchor4 Skolverket. (2013). Curriculum for the upper secondary school. Retrieved at 2020-11 -25

from: https://www.skolverket.se/getFile?file=2975

Skolverket. (2018). Curriculum for the compulsory school, preschool class and school-age-educare 2011. Revised 2018. Retrieved at 2020-11-25 from:

https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.31c292d516e7445866a218f/1576 88654682907/pdf3984.pdf

Skolverket. (2019). Sök statistik om förskola, skola och vuxenutbildning. Retrieved at 2021 -01-12 from: https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/statistik/sok-

statistik-om-forskola-skola-och-vuxenutbildning?sok=SokC&verkform=Gymnasieskolan&omrade=Natione lla%20prov&lasar=Hösttermin%202019

Skolverket. (2020). Goda relationer underlättar språkinlärning. Retrieved at 2021-01-12 from:

https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/forskning-och-varderingar/forskning/goda-relationer-underlattar-sprakinlarning

Sundqvist, P. (2009). Extramural English matters: Out-of-school English and its impact on Swedish

ninth graders' oral proficiency and vocabulary (Doctoral dissertation, Karlstad

University). Retrieved at 2021-01-14 from: http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:275141/FULLTEXT03.pdf

Sundqvist, P., & Olin‐Scheller, C. (2013). Classroom vs. extramural English: Teachers dealing with demotivation. Language and Linguistics Compass, 7(6), 329-338. Retrieved at 2020-11-23 from

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/lnc3.12031

Sundqvist, P., & Sylvén, L. K. (2014). Language-related computer use: Focus on young L2 English learners in Sweden. ReCALL, 26(1), 3-20. Retrieved at 2020-11-11 from:

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/recall/article/languagerelated

-computer-use-focus-on-young-l2-english-learners-in-sweden/254E2562978AFFBF98CC812368E766F7

Zheng, D., Bischoff, M., & Gilliland, B. (2015). Vocabulary learning in massively multiplayer online games: context and action before words. Educational

Technology Research and Development, 63(5), 771-790. Retrieved at 2020-12