CULTURE-LANGUAGES-MEDIA

Independent Project with Specialization in English Studies

and Education

15 credits, First Cycle

What Are the Best Practices for Offering

Instructor Formative Feedback on L2

Academic Writing?

I vilken utsträckning förbättrar formativ återkoppling gymnasieelevernas

akademiska skrivande?

Aleksander Rudenko

Asia Hussein Al

Abstract

The syllabus for English 5 through 7 in Sweden states that students should learn to understand and write different types of text, one being academic papers. Therefore, teachers are required to guide students in their academic writing process as they transition to formal written English. Through this study, we aim to investigate the best practices of formative feedback from instructors on L2 academic writing and see the attitudes of students and teachers when it comes to given and received feedback. Moreover, we also aim to connect the results that are found through research to the Swedish national curriculum. This will be done through educational databases such as the Malmö university library database and ERIC. We have found a total of ten empirical studies that touch upon the two aforementioned aims. Research in the field of formative feedback displays how students have a healthier attitude towards oral communication as they may directly communicate with the instructor at the cost of time. In contrast, instructors disagree by claiming that it is not as efficient as written feedback where they may take on a larger number of students in a shorter amount of time whilst providing more accurate responses. Teachers ought to be aware that while efficiency is important, it is not as vital as student progression in academic writing. Also, it would be interesting to examine the attitudes and levels of comfort of students in regard to peer reviewing and self-feedback with a focus on L2 learners.

Keywords

Formative feedback, oral feedback, written feedback, second language learning, upper secondary school

Individual Contributions

The authors of this paper confirm that all parts of the essay reflect the equal participation of both students. These are the parts we refer to:

➢ Planning and Creation of Essay Outline ➢ Selection of Research Questions

➢ Search of Sources

➢ Collaborative Writing of the Essay

Authenticated by:

Aleksander Rudenko Asia Ali Hussein

Table of Contents

1. Introduction 5

1.1. Theoretical Background 6

2. Aim and Research Questions 8

3. Methods 9

3.1 Search delimitations 9

3.2 Inclusion Criteria 9

Table 1. Inclusions and Exclusion 10

4. Results 11

5. Discussions 16

5.1. Best practices for offering instructor formative feedback on L2 academic writing 16

5.3. Student and teacher attitudes on giving and receiving feedback 19

6. Conclusion 21

6.1 Limitations 21

1. Introduction

English is widely spoken in Sweden as it is a compulsory subject in lower and upper secondary schools (Skolverket, 2011). Moreover, English is a global language and pupils are exposed to it through media and other means outside of school. However, academic writing in English is regarded as a challenge by some pupils in upper secondary school due to poor grammar, lack of vocabulary, poor spelling etc. Furthermore, teachers also deal with challenges in how to help pupils improve on their writing skills. The Swedish National Curriculum states that students should be allowed to develop correctness in their use of language in speech and writing, and the ability to express themselves with variation and complexity (Skolverket, 2011). Formal writing is generally more practiced in the upper secondary school and is a crucial stage for students to improve on their academic writing skills to prepare for higher education. Therefore, students at this stage need continuous formative feedback from their English teachers who help them along their journey to becoming competent in academic writing. Thus, in this paper, we define formative feedback as an instructional approach used by teachers to encourage learners to continuously reflect and revise their academic texts (Mcgarrell & Verbeem, 2007). This instructional approach consists of comments, suggestions and questions raised by teachers from a reader’s point of view, and then the pupils are expected to make the final judgements about the content of their academic paper.

Moreover, Formative feedback is described by Hattie & Timperley (2007) as “one of the most powerful influences on learning” (p.81). Unlike summative assessment in which students are graded through tests using strict standard grading criteria, formative assessment aims to guide student learning through continuous feedback to help them identify their strengths and weaknesses (Lee, 2017).

Formative feedback is usually given by teachers as a means to improve student achievement both in an oral form which involves interaction between teacher and student and a written form where students receive feedback in writing or both.

Despite the benefits of formative feedback, there exist some challenges and questions regarding teachers’ formative feedback practices and pupils’ reception of teacher-feedback. This doubt has been cast by students who reported that formative feedback from teachers was not very helpful in their writing process. This is demonstrated by Forsythe and Johnson (2016) in a study on students’

perceptions and attitudes towards formative feedback where they demonstrate that the way feedback is delivered to the students may lead them to either appreciate or disregard the feedback from teachers. Their study indicates that emotion plays a key role in feedback reception as students may perceive unfairness and indifference from the given feedback. This consequently leads to disappointment, hence negatively impacts their learning. Moreover, Forsythe and Johnson urge the importance of individually tailored formative feedback to meet the students’ needs while considering the emotional impact it may have on the students. Essentially, students' opinions, emotions, and attitudes affect their engagement and application of formative feedback.

1.1. Theoretical Background

Theories that are relevant to our issue on the best practices for providing instructor formative feedback are the writing process theory and active learning. It is stated in the syllabus for English (Skolverket, 2011) that the goal of studying English is to acquire methods and strategies for students to further educate themselves without the help of teachers. To become self-critical while acquiring knowledge in speaking, reading, writing, and others.

Maxine Hairston (1982) argues that the writing process theory, also known as the process theory of composition, is a method used to break down writing into smaller segments. Since writing a full paper can be seen as an overwhelming task, it becomes less threatening when it is completed in sequences. It also teaches the writer that becoming a writer does not magically occur over a task. Rather, it is seen as a process where everything is planned and developed, and the writer's knowledge evolves as their work takes shape. This process approach involves planning and generating ideas, drafting, and revision. Furthermore, teacher feedback that points out strengths and weaknesses as well as suggestions for improvement, which consequently leads to students’ self-evaluation, is an integral aspect of process

writing pedagogy. As a result, this teaching strategy enables learners to become more autonomous in their writing as the revision aspect involving useful feedback fosters attitudes and skills such as self-evaluation and reflection (Yeung, 2019).

Formative feedback focuses on active learning as it requires students to be active learners by encouraging them to think, reflect, and apply teacher feedback (Marlies Schillings, 2018). Active learning is based on the constructivist theory which states that learners construct their meaning by developing on their already existing knowledge. By actively engaging with teacher feedback, students take responsibility in their learning process. However, students should be feedback literate. Student feedback literacy is defined as “the understandings, capacities, and dispositions needed to make sense of information and use it to enhance work or learning strategies” (Carless & Boud, 2018, p.1316). Students as active learners with feedback literacy should be able to appreciate teacher feedback and understand their active role in the process, make analysis and decisions, and finally utilize the feedback and take action (Marlies Schillings, 2018). It is thus important to explore different practices for offering instructor formative feedback on L2 academic writing and their consequences in pupils’ learning. The paper also delves into teachers’ and pupils’ perspectives/attitudes on teacher formative feedback practices.

2. Aim and Research Questions

This paper explores what are the best practices for offering instructor formative feedback on L2 academic writing. It first explores the aspects of useful teacher feedback and its consequences. Also, the paper will look into what attitudes students and instructors articulate when feedback is given and received.

The following questions will be explored:

➢ What are the best practices for offering instructor formative feedback on L2 academic writing? ➢ What attitudes do students/instructors articulate to feedback given/received?

3. Methods

The primary procedure for acquiring sources was to perform electronic searches through numerous databases such as ERIC (Education Resources Information Center), ERC (Education Research Complete), and the Malmö university library database. Also, we used Google Scholar to find some sources that we could not find in the other databases. We used the following key words in various combinations during all our searches:

“Formative feedback”, “Feedback”, “Academic discourse”, “Academic writing”, “Writing”, “Writing improvement”, “Oral feedback”, “Upper secondary school” and “L2 learners”.

3.1 Search delimitations

A launch for the project was to look into sources available through the Google Scholar database and the Education Resources Information Center also known as ERIC. Firstly, searching for “feedback in writing” gave over three million results which gave too many sources to look through. Therefore, the search was narrowed down by combining formative feedback and academic writing. Secondly,

“formative education academic writing” was used as a search term in Google Scholar and Eric which in result gave 581,00 results. However, most of them did not fit the paper or the inclusion and exclusion criteria. To limit the search for accurate sources, the date-range was restricted to showcase sources between 2010 to 2020, and keywords were implemented into the search. Only ten up-to-date primary sources are included in this paper.

3.2 Inclusion Criteria

Several sources were included where the studies were performed on students in countries outside of Sweden, e.g. Turkey, Iran and Hong kong. Although these studies were conducted outside of Sweden, their findings have relevance for teaching and learning academic writing. This is because they discuss

teaching practices in a general context and offer interesting suggestions for teachers anywhere in the world. They bring new conditions and perspectives for learning, and their methodology is similar to research done in Scandinavia.

Studies conducted on university students were included. Even though it is difficult to generalize university students with upper secondary school students, these studies are included not to make broad claims, but rather draw connections between the instructor feedback practices that could be useful and applied across different levels of education.

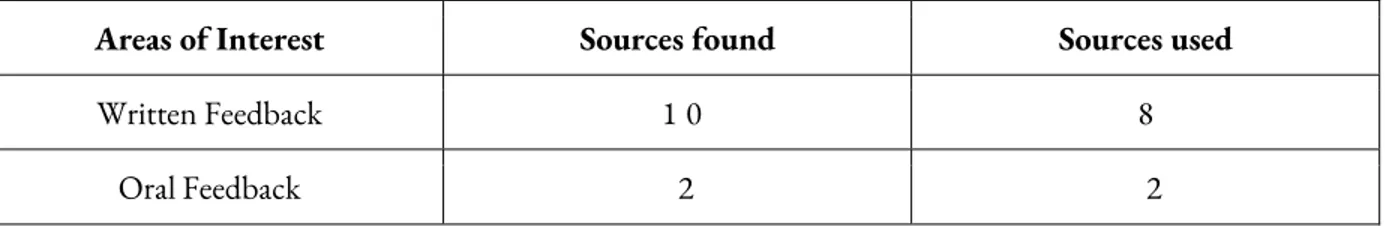

3.3 Exclusion Criteria

Amid the references found, those focusing on academic writing outside of school environments were excluded since outside factors may have impacted the writing process and by such twisted the results. Besides, sources based on formative feedback outside of oral and written and on tasks apart from academic writing have also been omitted as it would lead to a too broad research area. For example, peer feedback was excluded as it could twist the results based on the student. While the same may occur with a teacher, chances are diminished due to the given education and teaching profession. See Table 1 for information regarding findings and uses of sources.

Table 1. Inclusions and Exclusion

Areas of Interest Sources found Sources used

Written Feedback 10 8

4. Results

In the following segment of the paper, there will be various studies in regards to the research questions. Each paragraph contains information about one study and contains an empirical summary regarding the participants, methods, results, and summary of the authors. The first studies will focus on practices of offering instructor formative feedback and their consequences in learning. The remaining ones focus on attitudes of students and educators when giving and receiving instructor feedback.

Several studies have been conducted to investigate the best practices of instructor formative feedback on students' academic writing. To begin with, Ursula (2010) conducted a study that investigates whether formative feedback improves students’ academic writing and what factors contribute to students’ usage or dismissal of teacher’s feedback. The study is based on qualitative data collection which was conducted by analyzing 68 first-year undergraduate students’ responses to the formative feedback they received on their exploratory essay. The students handed in academic essays in three different drafts to which they received formative feedback from the teacher. The goal of these

assignments was for the students to use the first two formative feedback moments to improve on their final assignment. For the qualitative data collection, students rated on a scale of one to five the use of formative feedback in their writing process. The results showed that formative feedback is useful as an instructional method if utilized by the students. However, despite the benefits of formative feedback, there exist some problems where students do not act upon the teachers’ feedback due to lack of motivation and negative self-perception.

Richard Bailey and Mark Garner (2010) further support Ursula’s (2010) findings in their research “Is the feedback in higher education assessment worth the paper it is written on? Teachers' reflections on their practices'' by interviewing 48 educators in the United Kingdom. Participants were asked

questions regarding their perceptions of written formative feedback. Interviews were partially structured to encourage an open discussion atmosphere. Responses highlight how teachers view

students as weak or strong, where the former is motivated, and the latter is satisfied with less. As guidelines encourage teachers to be brief and vague for students to seek answers on their own, weaker students often give up or forget to work with given feedback. Educators further claim that some assignments are submitted very late, and therefore students may also not find the time to revisit their work before they move on to the next task. The authors conclude by saying institutionalized practices create problems of their own such as disengagement between students and educators, and that

educators need to find a way to decrease confusion amongst students.

Glover and Brown (2015) delve deeper into ways of decreasing confusion by looking if feedback can be too comprehensive or too incomprehensible to be useful for learning. They conduct the research “Written Feedback for Students: too much, too detailed or too incomprehensible to be effective?” across three years with over a hundred students from two different schools as participants. The used method is teacher markings and comments of written formative feedback and on student perception of the given feedback. Results show that while teachers are focused on errors and accomplishments, students prefer in-depth feedback that allows them to feedforward the given information into future tasks. Glover and Brown further claim that though assessment criteria are present and fulfilled, students claim the criterias are too weak which often leaves them misguided or confused. Finally, authors conclude by arguing formative feedback needs to focus and explain weaknesses, focus more on learning outcomes and less on grades and scores, and pay less attention to jots and titles in order to decrease confusion amongst students.

This is demonstrated by Bader et al. (2019) who like Ursula carried out a qualitative study on two teacher education institutions in Norway to investigate students' perception of formative feedback. The study consisted of 40 student teachers of English as a foreign language who received feedback on three assignments from their peers and teachers. These three assignments were compiled in a portfolio and received feedback for each of the assignments. Students received time to reflect on the feedback and improve on their written assignments. The forty student teachers were asked to write reflections about their writing process and how the formative feedback they received helped improve their final assessment. One hundred and twenty-eight reflections were collected and analyzed. The findings

demonstrated that students were mostly satisfied with the teacher feedback and praised the

opportunity given to them to revise and resubmit assignments and further expressed that it improved their language and writing skills.

Similarly, Lee (2011) discusses and problematizes teachers’ feedback practices in the article “Working Smarter, Not Working Harder: Revisiting Teacher Feedback in the L2 Writing Classroom”. The article is based on a study conducted in Hong Kong where written feedback data from 26 secondary school English teachers was analyzed. The study included follow-up interview data from six of the English teachers. The findings show that teachers believe language form such as grammar and vocabulary is more important than content and structure in English writing.

Next, Havnes et al (2012) conducted a quantitative survey in six upper secondary schools in Norway investigating how teachers and students use feedback in the subjects English Norwegian and Math (with English being the focus for this paper). The survey involved 192 teachers from the five selected schools and 391 students from the first year of upper secondary school. Both teachers and students were provided with statements regarding assessment and feedback practices in education to which they could answer correct, nearly correct, correct only to some extent, and incorrect. Furthermore, this study also focused on the teachers’ and students’ perception of feedback which involved qualitative data collection through conducting focus group interviews in 3 of the five schools. The findings demonstrated that most of the students find the formative feedback they receive from teachers to be beneficial and reported improvement in their assignments. However, the study showed that teachers overestimated the usefulness of the feedback they provided to the students as a large group of students said the formative feedback is often too general or not clear enough for them to digest and apply. Therefore, students express the need for clear feedback that is customized for their individual needs. Also, Christine McMartin-Miller (2014) reinforces this claim of students needing clear feedback in the article “How much feedback is enough? Instructor practices and student attitudes toward error treatment in second language writing” where the author investigates the student attitudes toward selective versus comprehensive error treatment. Three instructors and nineteen students are

interviewed at a first-year writing course in an international U.S university, and they all had a positive attitude towards receiving written feedback. However, not all students understood the given feedback or knew how to use it to improve their writing. The author concludes by concurring with Havnes in saying that teachers can overestimate their feedback, and therefore need to be taught how to use self-editing strategies to make better use of given feedback.

Additionally, Marzban & Sarjami (2014) conduct the study “Collaborative Negotiated Feedback versus Teacher-written Feedback: Impact on Iranian Intermediate EFL Learners‟ Writing” in Sari, Iran which gives us new insights. A total of 60 participants were chosen and during six weeks they were given classes on writing structures, paragraph organization, etc. to submit an essay at a set deadline. They were judged by pre and post-tests to measure the results. Each week they had two obligatory sessions to which the participants had to attend for tutoring and writing. One of the results was that students did not interpret the feedback given by teachers as their level of knowledge is too far apart. In other words, there was no way to ensure that written feedback is perceived by students as it is by the writer. While the results showcase that written teacher feedback wasn’t appreciated due to misunderstandings, it is stated that a combination of both written and oral feedback provides the best result for long term second language development where one is given feedback and may then directly ask for questions and clarifications.

In contrast to written feedback, Solhi and Eğinli (2020) performed the recent and contrastive study “The effect of recorded oral feedback on EFL learners' writing” where they compare recorded audio feedback and text-based feedback for 51 university students, with EFL standing for English as a Foreign Language. Participants were separated into two groups, one controlled group of 27 students and one experimental group of 24. All participants were given 80 minutes for writing an assignment where content, organization, etc. were to be assessed with the help of an essay assessment rubric. Results display how audio feedback is more efficient in giving formative feedback in comparison to text-based feedback for converting subtleties through e.g. increased involvement and retention of content. Further analysis of the results later showcased how students were multiple times more likely to apply given feedback in contrast to text-based feedback.

Similar research by Sobhani and Taybipour (2015) provides further evidence of how oral feedback is more appreciated by students, as it compares oral and written feedback on writing essays for Iranian EFL learners in their study “The Effects of Oral vs. Written Corrective Feedback on Iranian EFL Learners’ Essay Writing”. It is a quantitative research that collects the number of mistakes and performance based on pre and post-tests. The study takes place in Shiraz, Iran with 75 students as participants. Four control groups were made, two for focused and unfocused oral and written. All participants were given the task to write an essay in 45 minutes. Afterward, participants in written feedback groups got feedback where mistakes were highlighted and comments were given. They were to revise their paper in the second task. The oral group received feedback where the instructor talked about their mistakes and allowed the students to pinpoint their errors themselves. For the focused groups, the target was to highlight punctuation and capitalization amongst others while unfocused groups got all erroneous structures highlighted and commented on. Two weeks later, all participants performed the same test. The outcome was that students receiving oral feedback performed better than those who received written feedback. The authors conclude by saying the two forms of feedback can be combined for better learning outcomes.

All of the sources came to somewhat similar conclusions, that written feedback is confusing and students do not have as positive an encounter as they do with oral feedback. However, the findings don't necessarily align with popular beliefs in Sweden. While Ursula, McMartin-Miller, Bailey, and Garner amongst others claim that written feedback is confusing for students, it is used very commonly for educating pupils in Sweden's high school, upper secondary school, and university. This is mainly since the pupils in the studies aren’t exposed to teacher comments for a longer period. Pupils studying in upper secondary schools or universities tend to have or meet one teacher and examiner for multiple occasions, allowing them to clarify feedback through e.g. mail or a meet. The only study that differs, is one conducted by Bader. However, it also differs in the method as the study consists of three

assignments rather than one. Besides, the participants also got time to improve their assignments after getting feedback and also had to reflect on what they had done. Other studies didn’t do this or do it to the full potential.

5. Discussions

In the following segment, we highlight interesting results obtained from the results. Next, we discuss the discovery with our research questions, and further connect them to learning theories to discuss potential outcomes. Finally, we connect the theories and results to the curriculum used in Sweden to motivate teachers to include our findings in their education.

5.1. Best practices for offering instructor formative feedback on L2 academic writing

Formative feedback from teachers needs to be sufficient and detailed (Glover & Brown, 2015). According to the study conducted by Lee (2011), some teachers expressed their support for detailed feedback because it allows students to become aware of all the mistakes they have made in their

writing. Teachers further state that detailed feedback although it can be overwhelming to the students, shows how hardworking the instructor is, and in return students put in the same effort to better their essays. However, this practice is problematic as studies point out that teachers focused a lot on grammatical errors rather than other important elements of writing such as structure, content, and style (McMartin-Miller, 2014; Lee, 2011; Bader, 2019). Too much error correction could overwhelm L2 learners and create the notion that grammar is the most important aspect of academic writing. Therefore for feedback to be relevant and make more sense to the students, teachers need to focus on providing balanced feedback that helps students learn the writing conventions while simultaneously aiming to improve their language (Lee, 2011; McMartin-Miller, 2014). Focusing on the sufficiency of formative feedback helps students make use of the feedback as it instructs a clear direction.

Many of the studies emphasize that it is important for teachers to provide understandable,

encouraging, and objective feedback to the students (Ursula, 2010; McMartin-Miller, 2014; Havnes et al, 2012; Glover & Brown, 2015). Ursula (2010), demonstrates students’ awareness of feedback by asking them to recall the feedback they received on their assignments. The study showed that students who received encouraging feedback from the teacher tended to remember what comments they

received indicating that they engaged with the feedback. Besides, Bader (2019) presented that students in their portfolio reflections reported that they encountered an emotional response to the teacher's feedback based on the tone it was formulated as well as disengagement due to the poor quality of the feedback. It is found that students react emotionally to feedback on their assignments depending on the teacher's tone and style and therefore teachers are encouraged to take students’ personality and emotional wellbeing into account . Therefore, although it is difficult to avoid the critical aspect of feedback, teachers should make the effort to formulate their comments in a critical yet empowering manner to strengthen and reinforce learner motivation and create a positive attitude towards teacher feedback (Bader, 2019; Ursula, 2010; Glover & Brown, 2015; Bailey & Garner, 2010). This way, despite the emotional discomfort students might feel, they will be able to recognize the intent behind feedback which is to provide new and challenging perspectives to help them develop in their learning. Additionally, formative feedback should be timely and frequent for students to appreciate and act upon it (Glover & Brown, 2015; Bailey & Garner, 2010; Bader, 2019). For example, Bader (2019) suggests that the process-writing strategy where students were allowed to gradually complete their writing assignment and received feedback in every piece of the assignment contributed to students’ improvement in their academic writing. This writing process was highly appreciated by the students as some of them reported that it helped them process their initial emotional responses to the feedback and allowed them to digest the constructive feedback, reflect and revise their academic writing skills. Consequently, Bader advises teachers to implement process-writing (writing in stages) like the portfolio process to give students the chance to transform and improve on their work and as a result produce a well-written final draft. Furthermore, teachers can allow students to experience authentic writing by employing multiple drafting in student assignments. She further stresses that denying students the time and opportunities for revision leads to students’ dismissal of the teachers' feedback comments despite how detailed and helpful it may be.

Another practice of useful formative feedback is for teachers to involve students actively in the feedback process (Havnes et al, 2012; Bader, 2019; Lee, 2011). According to Lee (2011), teachers should encourage students to express their views and questions regarding the feedback they received.

This way students will become more interested and actively engaged in the formative feedback process, and could enable them to formulate their own learning goals and follow their writing progress.

Furthermore, students’ active involvement in teacher feedback deepens their feedback literacy as it allows them to be in communication with the teacher and “re-negotiate their learning goals

throughout the teaching-learning-assessment process” (Lee, 2011, p.392). Teacher-student interaction is an important element in giving and receiving feedback however, some teachers express that it can be a challenge to interact with all students as not all students are willing to actively interact with the teacher regarding the feedback they receive. They further stated that while some students are eager to seek out help regarding the teacher feedback which shows their active engagement in their learning and self-reflection, others simply choose not to interact with the teacher. Most teachers express that

students need to be trained on how to use and utilize the feedback they receive from teachers to

promote student feedback literacy, hence active engagement and shared responsibility in their learning. Next, educators should focus less on marks and more on learning, as marks are temporary while

learning is permanent. By focusing on marks, students tend to disregard information obtained from formative feedback as they have a focus on what mark they have received rather than reflecting on what knowledge they have obtained throughout the process (Marlies Schillings, 2018). This is not to say that marks should be completely abandoned. Marks are necessary for the function of the

educational system, as they allow comparisons between classrooms and schools whilst also giving an overview of what level of knowledge a student possesses. However, teachers can delay submission due dates for more revision or better yet avoiding public marks for students to view and instead

highlighting their road to becoming a writer through the use of writing and reading strategies (Maxine Hairston, 1982).

5.2. Criteria and Curriculum

When giving feedback, whether it is oral or written, educators must connect the tasks of the assessment to the knowledge criteria for the given course. While this may seem like apparent information, it isn’t always the case. Skolverket (2011) states students should produce written works in more formal

settings where they instruct, explain, discuss, assess, etc. whilst using strategies and active participation. The results showcase that using practices for formative feedback does lead to improved written works. For example, in McMartin-Miller’s (2014) study, it is seen how repeated use of instructor feedback does lead to better writing, even though there is room for improvement. Shortly put, by providing students with a clear goal and a path to fulfilling the assessment tasks and criteria - Educators simplify the process of writing. The aforementioned process can be achieved through e.g. Hattie and

Timperley’s (2007) developmental framework, containing three segments: feed-up, feedback, and feed-forward.

First, feed-up is about presenting the assignment alongside its purpose. This is very early into an assignment and is used to connect the criteria and guidelines provided by e.g. Skolverket to provide students with a clear goal of what goals they are to reach through the course of writing. Secondly, feedback is the part where teachers give students their feedback. It should be executed with the aforementioned strategies. Finally, when feed-forwarding students, educators need to revisit the feed up and feedback stages to connect criteria, guidelines, and student development to e.g. a matrix to visually display what the students have accomplished in this stage of developing their writing as a process and what they should improve upon for the next task. This is further supplementary if educators prepare several batches of feedback and development, which instantly allows students to delve into their writing for an adjustment (McGarrell & Verbeem, 2007).

5.3. Student and teacher attitudes on giving and receiving feedback

In regards to student and teacher attitudes upon giving and receiving feedback, almost all studies regarding written feedback point to student confusion whilst the ones regarding oral feedback point to student satisfaction. According to aforementioned studies in the result section, students prefer oral feedback over written feedback as they can directly communicate with educators for e.g. clarification and explanation. In contrast, when it comes to written feedback educators tend to give comments and move on to the next task without giving time for students to reflect and adjust their papers

period where students work with assignments that are not related to academic writing, as they are more likely to forget their earlier acquired knowledge in writing if they do not frequently train the skill ((McGarrell & Verbeem, 2007)). It is therefore important, as Havnes and McMartin-Miller argue, that students are taught to self-evaluate rather than just view feedback as a simple change. According to Carless & Boud (2018), students are more likely to be confused about a comment with buzz words if they do not take the time to analyze and reflect upon what they have written. Richard Bailey and Mark Garner describe this in their study as students who are weak and strong. Those that are strong tend to be those who have the ability to criticize their own writing and accept teacher feedback with open arms. In contrast, weaker ones are often discouraged to make changes based on their time and ability to deeply analyze the given feedback. Schillings et al. (2018) argue teachers also have the task to make their feedback understandable and adapt it to the level of their students. This concerns both written and oral feedback. They further claim that if students do not understand the feedback that is given, they must introduce students to e.g. the buzz words that are being used. Finally, using written

feedback in combination with oral feedback is generally seen to provide clear learning outcomes amid students as it is seen in Marzban and Sarjami’s study and Schilling et al. (2018) article, where they claim that students can reflect on the given written feedback while clarifying potential confusion through verbal communication.

6. Conclusion

The purpose of this paper was to look into best practices for offering instructor formative feedback on L2 academic writing and students and teacher attitudes on giving and receiving formative feedback. While the study does have certain limitations, such as including research from countries outside of the EU - they bring new perspectives from different contexts and are replicable in Sweden. Through this study, we have found that giving feedback needs to be done with time and clarity in mind, as students may interpret feedback differently if given too early or imprecise. One method of writing found in this study involves dividing one large assignment into several smaller ones, where students are given

feedback after each occasion to propel feedback into the next task. Also, we believe that it is vital for teachers to motivate students into writing by varying the tasks and feedback types such as e.g. written and oral feedback. While the results have shown that oral feedback is more preferred than written amongst students, one should aim to combine the two to get the best of both worlds. Finally, after researching this area we want to look deeper into other types of feedback such as e.g. attitudes and levels of comfort of students in regards to peer reviewing and self-feedback with a focus on L2 learners. We expect to ask a set amount of students to write a paper. Afterward, they will peer review it and receive teacher feedback. By comparing the result of the feedback, and holding semi open discussion interviews with the participants, we hope to learn more about the attitudes of feedback and levels of comfort students have while writing peer reviews in relation to teacher feedback.

6.1 Limitations

A limitation to consider is to what degree these studies on formative feedback can be generalized for all levels of education. Some studies were conducted on university students while the target group for this research paper is upper secondary students. Therefore, research for one level of education may differ in comparison to lower or higher levels. University students are expected to possess some level of

phase. Consequently, it is unsafe to say whether all the instructor formative feedback practices discussed would produce the same results across different levels of education. Despite this limitation, these studies explore teacher feedback practices that have pedagogical implications for language teaching regardless of the level of education of the learner. The variety of instructor formative

feedback strategies presented in these studies provide us with insights into the challenges teachers and students of all levels face when learning a second or foreign language. As students ourselves, we could relate our upper secondary school English classroom experiences of instructor formative feedback to the feedback practices and perspectives demonstrated by the studies with university students.

7.0 References

Primary sources

Bader, M. (2019). Student perspectives on formative feedback as part of writing portfolios. Assessment

& Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(7), 1017-1028.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1564811

Bailey, R., & Garner, M. (2010). Is the Feedback in Higher Education Assessment Worth the Paper It Is Written on? Teachers’ Reflections on Their Practices. Teaching in Higher Education, 15(2), 187–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562511003620019

Glover, C., Brown, E. (2015). Written Feedback for Students: too much, too detailed, or too incomprehensible to be effective? Bioscience Education, 7(1), 1-16.

https://doi.org/10.3108/beej.2006.07000004

Havnes, A., Smith, K., Dysthe, O., & Ludvigsen K. (2012). Formative assessment and feedback: Making learning visible. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 38(1), 21-27.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2012.04.001

Lee, I. (2011). Working Smarter, Not Working Harder: Revisiting Teacher Feedback in the L2 Writing Classroom. Canadian Modern Language Review, 67(3), 377-399.

doi:10.3138/cmlr.67.3.377

Marzban, A. & Sarjami, S., M. (2014). Collaborative Negotiated Feedback versus Teacher-written Feedback: Impact on Iranian Intermediate EFL Learners‟ Writing. Theory and Practice in

Language Studies, 4(2), 293-302. https://doi.org/10.4304/tpls.4.2.293-302

McMartin-Miller, C. (2014). How much feedback is enough?: Instructor practices and student attitudes toward error treatment in second language writing. Assessing Writing, 19(1).

Ursula, W. (2010). The impact of formative feedback on the development of academic writing,

Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(5), 519-533. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930903512909

Sobhani, M. & Tayebipour, F. (2015). The Effects of Oral vs. Written Corrective Feedback on Iranian EFL Learners’ Essay Writing. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 5(8), 1601-1611.

http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0508.09

Solhi, M. & Eğinli, İ. (2020). The effect of recorded oral feedback on EFL learners' writing. Journal of

Language and Linguistic Studies, 16(1), 01-13 https://doi.org/10.17263/jlls.712628

Secondary sources

Carless, D, & Boud, D. (2018). The development of student feedback literacy: Enabling uptake of feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(8), 1315-1325.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354

Forsythe, A., & Johnson, S. (2017). Thanks, but no-thanks for the feedback. Assessment & Evaluation

in Higher Education, 42(6), 850–859. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2016.1202190

John Hattie, & Helen Timperley. (2007). The Power of Feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4624888

Lee, I. (2017). Classroom writing assessment and feedback in l2 school contexts. Place of publication not identified, Singapore: SPRINGER. https://doi-org.proxy.mau.se/10.1007/978-981-10-3924-9

Marlies Schillings, H. (2018, November 14). A review of educational dialogue strategies to improve academic writing skills - Marlies Schillings, Herma Roebertsen, Hans Savelberg, Diana Dolmans, 2018. Retrieved January 14, 2021, from

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1469787418810663

Matsuda, P. K. (2003). Process and post-process: A discursive history. Journal of Second Language

Mcgarrell, H, & Verbeem, J. (2007). Motivating revision of drafts through formative feedback. ELT

Journal, 61(3), 228-236. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccm030

Hairstone, M. (1982). The Winds of Change: Thomas Kuhn and the Revolution in the Teaching of Writing. College Composition and Communication, 33(1), 76-88.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/357846

Skolverket. (2011). Engelska läroplan för gymnasieskola. Stockholm: Skolverket. Retrieved from

https://www.skolverket.se/undervisning/gymnasieskolan/laroplan-program-och-amnen-i-gymnasieskolan/amnesplaner-i-gymnasieskolan-pa-engelska

Skolverket (2020). Rätt återkoppling utvecklar lärandet. Reviderad 2020. Stockholm: Skolverket. Retrieved from

https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/forskning-och-utvarderingar/forskning/ratt-aterkoppling-utvecklar-larandet

Yeung, M. (2019). Exploring the Strength of the Process Writing Approach as a Pedagogy for Fostering Learner Autonomy in Writing Among Young Learners. English Language Teaching, 12(9), 42. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v12n9p42