Socio-Economic Perspective

– an evaluation of state funding of

Local Investment Programmes for

ecological sustainability in Sweden

evaluation covers the programmes on which final reports had beensubmitted by June 2004 (101 out of 211 programmes).

The main objectives of LIP were to bring about environmental improvements and create employment. A further aim was to promote new technologies and new approaches. The evaluation is based on the assumption that the aim of state funding is to produce maximum benefit for the state funding invested in these sectors. The authors demonstrate the effects of LIP using key figures and qualitative analyses. The grant funding has been surprisingly effective in achieving a positive impact on the environment. Among other things, it has been estimated that it has cost SEK 0.12 for each kilogram of reduced carbon dioxide emissions, which may be regarded as a very low cost. Since LIP achieves a number of socio-economically important objectives at the same time, the overall assessment of LIP is a favourable one.

The evaluation has been made by the International Institute of Industrial Environmental Economics at Lund University, at the request of the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency.

Perspective

-an evaluation of state funding of Local Investment Programmes for ecological sustainability in Sweden

Orders

Order tel: +46 8 505 933 40 Order fax: +46 8 505 933 99

E-mail:natur@cm.se

Postal address: CM-Gruppen, PO Box 110 93, SE-161 11 Bromma Internet: www.naturvardsverket.se/bokhandeln

Swedish Environmental Protection Agency

Tel: +46 8 698 1000, fax: +46 8 202925 E-mail: natur@naturvardsverket.se Postal address: Swedish EPA, SE-106 48 Stockholm

Internet: www.naturvardsverket.se ISBN 91-620-5479-1.pdf

ISSN 0282-729 Elektronisk publikation © Swedish EPA 2005

Text: Tomas Kåberger, Anna Jürgensen, International Environment Institute at Lund University English translation by Maxwell Arding

Foreword

This report deals with some socio-economic aspects of state funding of Local Investment Programmes (LIP) in Sweden. The evaluation has been made by the International Institute of Industrial Environmental Economics (IIIEE) at Lund University, at the request of the Swed-ish Environmental Protection Agency.

It is difficult to evaluate the LIP system. This is because the system itself has a number of objectives, such as multi-dimensional environmental objectives, employment and societal learning. In addition, a quantitative analysis is hindered by the fact that LIP funding acts in combination with several other instruments, instruments that are themselves complicated and that have varied over the years that LIPs have operated.

The fact that the LIP scheme has a number of objectives is a departure from the Swedish tradition that a given objective should be addressed using a single instrument. However, LIP was introduced when Sweden had recently joined the European Union, where the tradition of using several objectives to justify a given directive or regulation prevails. Our efforts to iden-tify evaluation methods have confirmed that a multitude of objectives makes quantitative evaluation more difficult. In addition, by combining a number of one-dimensional assess-ments, we have shown that projects yielding several positive effects overall appear to be socio-economically effective.

LIP has been scrutinised and debated right from the outset. It has received a great deal of attention because the system has been a major item in the state budget and because LIP represents a new form of funding. A series of evaluations have been made in recent years at the request of the Swedish EPA. This is one of the final evaluations. We have attempted to identify parameters with which to measure the cost-effectiveness of LIP funding. We have endeavoured to determine the effectiveness of the system by calculating key figures and developing an understanding of the processes involved.

Our findings surprised us and others. One distinction is crucial to understanding the effi-ciency of LIP: It is one thing to pay a price for reducing en emission by one kilogram; it is another to make an investment so as to reduce emissions annually by one kilogram over a period of one or two decades. To appreciate the cost-effectiveness of LIP it is essential to understand this distinction.

We would like to thank all the officials at municipalities and companies who gave up their time to discuss LIP projects in which they had been involved. We owe a particular debt of gratitude to those who had already taken part in four or five previous evaluations. We also wish to thank Dr Anna Bergek, and Professors Roland Clift, Marian Radetzki and Thomas Sterner, who, as active members of the reference group, contributed valuable criticism, ques-tions and suggesques-tions. We have not accepted all their proposals, but we hope that we have responded to the constructive criticisms we have received.

Funding of this kind has been found to be potentially effective. Perhaps we will help to bring about some productive and well-considered ideas. But most of all we hope that our comments on administrative methods favouring a high level of cost-effectiveness and the value of high-quality reports are put to use.

This evaluation has been made by Tomas Kåberger and Anna Jürgensen, with contribu-tions from Margarethe Forssman and Vaidotas Kuodys. The authors have sole responsibility

for the content of this report and it can therefore not be taken as the view of the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency.

Lund, November 2004

Contents

Foreword 3 Contents 5 Summary 8

Definitions of terms 10

Local Investment Programmes 11

History of LIP 11

Links to other environmental policy 11

Aims of LIP 12

Types of LIP 13

The LIP process 14

The application process 14

Implementation 14

Final report 14

Summary 15 Background and scope of the evaluation 16

Reason for the evaluation 16

Focus and delimitations of the evaluation 16

Discussion of objectives 17 Reference group 18 Summary 18 Summary of findings 20 Investigative method 22 Levels of evaluation 22 Overall study 22 Municipal study 22 Industry-specific study 23

Data gathering and selection 23

Data quality 24

Selection of municipalities and their representativeness 24 Summary 26 Evaluating instruments 27 Types of instrument 27 Evaluation methods 28 Summary 29 Findings 30

Municipal assessments and reporting 30

General quality of reporting 30

Investment assessments 30

Calculating quantitative environmental effects 30

Reporting of effects on employment 31

Emission reduction effects 31

Carbon dioxide (CO2) 33 Calculation methods and their significance 35

The pulp and paper industry 37

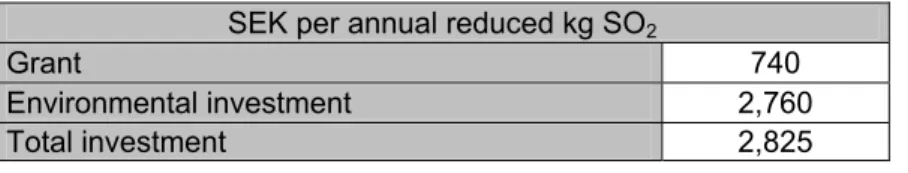

Sulphur dioxide (SO2) 37

Nitrogen oxides (NOX) 38

Measures involving reduction in emissions of CO2, NOx and SO2 39

Effects on employment 39

Allocation of funding 40

Grant effectiveness 42

Potential indirect effects on employment 43 Summary 45

Analysis of grant effectiveness 46

Progressive selection 46

Constructive evolution 47

Summary 49

Other observations 50

Other environmental effects 50

Other relevant instruments 50

Spread of ideas, repeat implementation, further development 51 Competitiveness 52 Summary 53

LIP as an instrument 54

Choice of instruments 54

Significance of green taxation 55

Lessons for the future 58

Comments on programme design 59

Single or multiple objectives? 59

Summary 60 Conclusions 61 References 62 Written sources 62 Interviews 65 Municipal interviews 65

Reference group meetings 66

Abbreviations and definitions 67

Appendix 1 68

List of all evaluations 68

Appendix 2 69

List of measures 69

Appendix 3 72

Adjustments in the database 72

Appendix 4 73

Adjustment of effects of reduction in electricity use on carbon dioxide emissions73

Appendix 5 74

Appendix 6 75

Scatter diagrams, unemployment 75

Appendix 7 78

Summary

This report is the result of an evaluation of Swedish Local Investment Programmes from a socio-economic perspective. The evaluation was conducted by researchers at the Interna-tional Institute of Industrial Environmental Economics (IIIEE) and commissioned by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency.

Investment programme funding was available between 1998 and 2002. A total of SEK 6.2 billion was granted to 211 programmes in 161 municipalities (representing 55 per cent of all Swedish municipalities). Each programme involved a number of measures, often invest-ments. The measures were carried out by the municipalities themselves or by private enter-prise. An average of 25 per cent of the investment costs were funded.

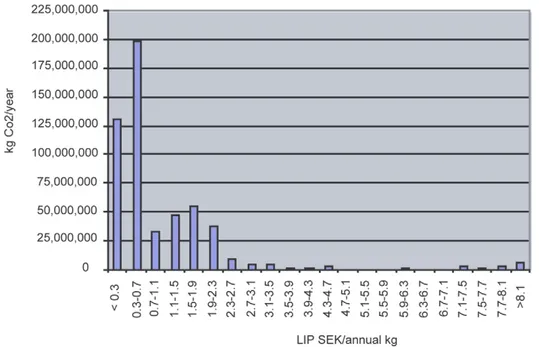

Out of a large number of measures of various kinds, this evaluation focuses on those re-sulting in reductions of CO2, NOX or SO2. We have calculated indicators of the cost-effectiveness of the funding, in relation to these environmental effects as well as effects on employment. The evaluation includes a qualitative discussion of the impact of the funding on the introduction of new technologies and new methods.

The results were surprisingly positive, as criticisms and concerns have previously been voiced about the funding scheme. Measures reducing emissions of CO2 have had an average state investment cost of SEK 0.12 (€0.013), assuming an annuity factor of 0.1 on the invest-ment cost. This estimate assumes all other desirable effects to have a value of zero, even when significant results are reported. A sizeable portion of the investments were made in sectors achieving a carbon tax reduction. From an environmental economics perspective, the scheme has been of benefit to society in these cases, since the tax reductions (society’s loss) are larger than the funding (society’s cost).

We identified two mechanisms we believe have contributed to the strong performance of the completed programmes in this evaluation compared to previous reports on projects in receipt of state funding. The first mechanism – "progressive selection" - describes how less cost-effective projects have been abandoned during the LIP process from discussion of ideas at municipal level, through application and on to granting of subsidies. Even after funding has been granted, many projects have not been carried out because municipalities or private actors have decided they were not cost-effective enough.

The second mechanism is "constructive evolution" and represents the flexibility inherent in the system. The project owners were allowed to change the scope and design of their pro-jects as long as their relative cost-effectiveness remained at least the same (if not better). Funding was never increased. This procedure was carried out in a written dialogue between the municipality and the Swedish EPA so that each step and statement is a public document available for anybody to scrutinise.

This funding scheme has led to testing of new technology and new forms of cooperation. Unlike traditional subsidies targeted at technology developers, the LIP investments were channelled via existing customers, thus creating a demand-fuelled stimulus for new technol-ogy. Examples were found of successful investments that were later repeated and spread, without additional funding.

The evaluation has been based on quantitative information from the EPA’s project data-base and interviews with representatives from 10 municipalities. The evaluation also in-cludes the results of an in-depth study of four LIP projects in the pulp and paper industry.

Definitions of terms

A number of terms and abbreviations requiring clarification are used in this report. The proper name for LIP funding is "state funding for Local Investment Programmes", abbrevi-ated to LIP in this report. "LIP" is also used here as an abbreviation of "Local Investment Programmes".

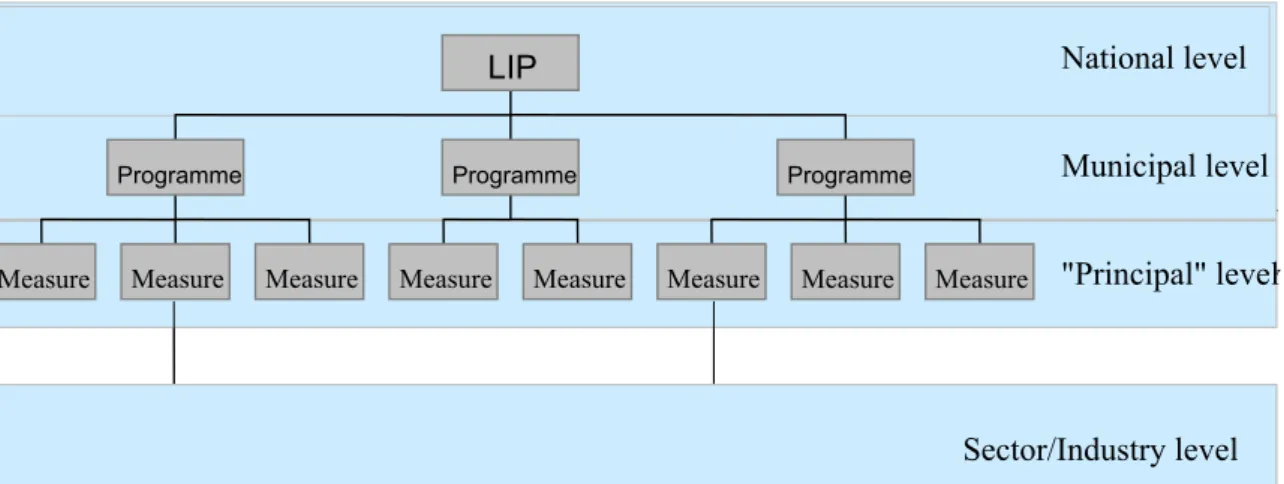

LIP consists of programmes, each coordinated by a municipality. In a few exceptional cases programmes have been coordinated jointly by several municipalities and associations of local authorities. Each programme involves one or more measures. "Measures" are specific environmental measures in various main groups such as waste and traffic, in which meas-ures are also divided into more specific categories, known as sub-groups, such as energy saving in housing, public education projects and sewage treatment plants. The principal responsible for these measures may be the municipality, companies of various kinds, organi-sations etc. The term "principal" is used in this report to refer to those responsible for im-plementation and reporting of a measure, not for entire programmes. In many cases measure are implemented in the form of a project within organisations. A project may also involve several measures. As a rule, municipalities have had an LIP coordinator, who has coordi-nated the measures and been ultimately responsible for reporting. All measures for which a final report has been submitted can be found in the Swedish EPA internal database. The database contains information submitted by municipalities in the form of complete Excel spreadsheets providing basic details of the financial outcome of the measures, such as total investment, environmental investment and funding. The database also shows quantified envi-ronmental impacts and employment effects. Employment is shown as permanent jobs and

person years. The term "person year" has the same meaning as the expression "man-year's

work" used in this report.

LIP has also required investments on the part of the project owners. The term total

in-vestment refers to the total cost of the measures. Many of the inin-vestments also have

non-environmental elements, and project owners have therefore been asked to specify the

envi-ronmental investment. The final grant averages 25 per cent of the additional cost incurred

as a result of the environmental investment.

Explanations of other expressions and abbreviations used in this report are given in the chapter "Abbreviations and definitions".

Local Investment Programmes

The following section provides an introduction to the funding of local investment pro-grammes for environmental sustainability, the objectives of the funding scheme and the form of funding available.History of LIP

Applications for funding for local investment programmes (LIP) could be made between 1998 and 2002. Around half (55 per cent) of all Swedish municipalities were granted fund-ing; the vast majority of projects have been carried out in large or medium-sized municipali-ties. Principals responsible for municipal projects have mainly been municipal administra-tions and municipal companies, although private enterprise and other legal entities have also been able to implement projects.

In total, some 270 Swedish municipalities submitted complete LIP applications. 161 of them were granted funding. Several municipalities have had more than one programme over the years. 34 municipalities are carrying out two programmes, five are carrying out three programmes, and one municipality is carrying out no fewer than four programmes. There are also programmes being implemented by associations of local authorities and by several mu-nicipalities jointly. A total of 211 programmes have received LIP funding.

LIP's total budget appropriation was SEK 6.2 billion between 1998 and 2002. The pro-jects concluded and approved when this evaluation was made involved total funding of SEK 1.8 billion. Swedish EPA officials estimate that SEK 4.7 billion will have been paid out when final reports for all projects actually carried out have been submitted.

The Ministry of the Environment was originally responsible for LIP funding, but the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency has administered grants for local investment programmes since 2002. The sole right to decide grants and modification of measures was also transferred from the Government to the EPA with effect from 2002.

Following LIP a new form of support has been created, known as KLIMP – the Climate Investment Programme. The structure of that programme very much resembles LIP, but the programme itself focuses more specifically on measures relating to climate impact.

Links to other environmental policy

LIP was preceded by a series of similar but less comprehensive programmes. A budget ap-propriation of SEK 100 million was made during 1995 – 1997 for investment grants for the transition to ecological sustainability (SFS 1995:1044). Aside from aiding ecological transi-tion, the aim was to create employment opportunities. Many of the projects focused on waste and sewage treatment (Swedish EPA 1997).

There then followed an appropriation of SEK 1 billion, known as "the ecocycle billion", (SFS 1996:1378) during 1997 - 1999, intended to support investments in buildings and tech-nical infrastructure considered to promote ecologically sustainable development.

Sweden adopted Agenda 21 following the Rio Conference of 1992. One of the principles under Agenda 21 is that of subsidiarity, ie, decisions should be taken as close as possible to those concerned. From a Swedish viewpoint, municipalities have been a natural platform for local Agenda 21 initiatives. Under Agenda 21, Sweden made a commitment to begin

imple-menting the Agenda 21 concept locally. Under article 28:2 of Agenda 21, the aim was to reach local agreement on the form of the local agenda by 1996. Much of Sweden's local Agenda 21 was decided on in 1997 (Swedish Institute for Ecological Sustainability, 2004; Gothenburg University, 2004). Local Agenda 21 is expected to encompass municipal ad-ministration, private enterprise, various organisations and public agencies, as well as all private individuals. LIP can be seen as a part of this process. As a rule, LIP is linked to Agenda 21 at local level, since LIP also uses municipalities as a platform. The regional rele-vance of local investment programmes is checked by way of the fact that the ordinance re-quires the county administrative board to be involved in the application and implementation.

A year after the introduction of LIP, in 1999, the Swedish Parliament adopted 15 overall environmental objectives. County administrative boards set regional objectives on the basis of the national ones, and in some cases municipalities also set local objectives. However, these objectives had not been specified in sufficient detail to affect the implementation of local investment programmes in the early years. But LIP measures are being carried out in relation to most of the environmental objectives and are contributing to their achievement

Aims of LIP

Under the State Funding for Local Investment Programmes Ordinance (SFS 1998:23), mu-nicipal measures under local investment programmes will only be eligible for state funding if their purpose is to:

1) reduce the burden on the environment;

2) increase efficiency in the use of energy and other natural resources; 3) favour the use of renewable raw materials;

4) increase reuse, use and recycling;

5) help to conserve and improve biodiversity and safeguard our cultural heritage; 6) help to improve the circulation of nutrients in natural cycles; or

7) improve the indoor environment in buildings by reducing the presence of allergenic or other hazardous substances and materials, provided that the measure, alone or in combination with other measures is also intended to achieve one or more of the en-vironmental effects under 1 – 6.1

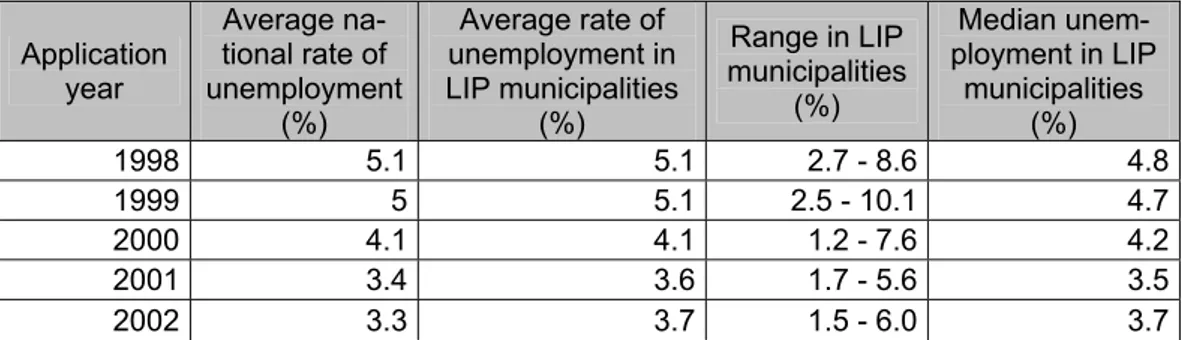

Another aim of LIP was that the programmes would help to reduce the relatively high rate of unemployment. The ordinance provides that "eligibility for a grant requires that the measures under a local investment programme may be expected to reduce unemployment" (SFS 1998:23, section 3).

In addition to the specific environmental and employment-related objectives, the funding scheme had overall aims. These included the explicit aim that LIP should also help to achieve greater equality of the sexes and that grants would be available for measures leading to increased sexual equality, provided that the environmental objective criterion was met (SFS 1998:23, section 1a (4))2. Investment programmes were also to explain how the meas-ures would contribute to new technologies, promote architectural quality and safeguard cul-tural heritage. But achievement of these effects is not an explicit objective.

1

This item was added by Ordinance 2000:735 2

The ordinance imposes restrictions on the funding, of which the most important are as follows.

• Grant eligibility requires that the measures are not performed in compliance with laws or other statutes, or constitute regular maintenance.

• Grants are not available for measures that fall within the scope of normal op-erations and that would have been carried out in any case.

• Grants for profit-making operations may not exceed 30 per cent.

A further general comment that may be made is that measures that could be regarded as profitable, with a reasonable payback time, were not eligible for a grant.

Types of LIP

The 211 programmes in receipt of funding have involved a great variety of measures. Table 1 shows a breakdown of measures and some examples of measures placed under each cate-gory.

Table 1 Examples of measures

Main category Examples of measures

Traffic Heavy-duty vehicles - biogas, eco-vehicles, extension of the

cycleway network

Multi-dimensional projects Modernisation of housing areas, from mass production to environmental programme, miljötorg ("environmental square") Conversion to renewable

en-ergy

Conversion to district heating, solar heating, district cooling and "free" cooling, energy-efficient climate control

Water and sewage treatment Reed beds for sludge treatment, environmentally friendly car washes, creation of wetlands

Waste Industrial environmental cooperation, digester gas units and

energy production, composting units

Building modifications Modification of residential properties, modernisation of historic industrial premises

Industrial projects Emission reductions, investments in less environmentally harmful machinery

Site remediation Controlled composting of contaminated excavated materials Energy efficiency/energy saving Supply of waste heat, efficient lighting, energy saving Supportive measures Involvement of residents, public education, administration of

the programme, quality assurance

Nature conservation Wetlands, promotion of biodiversity, creation of nature parks close to urban areas

All in all, LIP grants have been awarded for more than 1800 measures. Around one third of them are energy-related.

The LIP process

All programmes have undergone a process that may be divided up into three main stages: (i) the application process; (ii) implementation; and (iii) final report and follow-up. The division of responsibility in the process has changed during the lifetime of LIP, but the main stages have remained the same.

The application process

Applications were prepared in each municipality, often in consultation with a number of municipal and other local actors. In many cases various proposals were discussed and exam-ined, some of them then being combined to form a programme. Under the ordinance (SFS 1998:23), municipalities must also consult the county administrative board in their county, and the board must then submit a consultative statement to the Government.

For the first four years measures were assessed by the Ministry of the Environment. This responsibility was then delegated to the Swedish EPA. Funding decisions were taken by the Government until 2002, when the Investment Support Council at the Swedish EPA took over. Where necessary, experts from relevant government agencies, such as the Swedish Energy Agency (energy projects), and the National Road Administration (traffic and trans-port) have been consulted.

During the first four years municipalities had first to submit a pre-application. A number of promising municipalities were then invited to the Ministry of the Environment for a dia-logue, in which they were informed of criticisms of the programme in terms, for example, of its environmental effects, grant-funded components, and the consistency of the measures with the regulations. These dialogues were only conducted until the end of 1999. Assess-ments were made of programmes as a whole, and also of each measure involved. Grants were awarded to entire programmes.

Implementation

Implementation is based on a timetable and investment plan drawn up by the municipality. 80 per cent of the grant for the first year is paid out in line with the plan. This enables mu-nicipalities to begin implementing their measures. This part of the process thus involves the final division of responsibility, possible procurement etc. During implementation interim reports are submitted each year to the relevant county administrative board. These reports must state whether the timetable has been adhered to, the environmental and employment effects achieved, and how the progress of the programme should be monitored in the future. If the principal wishes to change the form of the measures, a request to that effect must be submitted to the Swedish EPA (previously the Ministry of the Environment). The request must set out the effects of the change on economic aspects, environment and employment. The municipality will be notified whether or not the change has been approved within three months.

Final report

The municipality must submit a final report when the investment programme has been com-pleted. Facilities ready for operation can be regarded as completed even where no final in-spection or monitoring of effects has been performed (Swedish EPA, 2003). At the final

report stage the relevant county administrative board must submit a statement in which it comments on the implementation and reporting of the programme.

The environmental effects achieved must be presented in conjunction with the final re-port. Where those effects will only become evident in the longer term, an estimate must be made and the material on which the estimate is based must be presented.

It may be necessary to supplement final reports before they receive approval. The last stage is a final decision on funding and disbursement of the remainder of the grant (maxi-mum 20 per cent). If it is not considered that the effects have been fully achieved, the mu-nicipality is expected to refund the portion of the grant exceeding the funding that is finally approved. The final report must also clearly state the methods to be used to monitor and evaluate the measures. However, any monitoring and evaluation of measures need not then be reported to the authority.

Summary

• LIP was a state funding scheme under which grants were paid, mainly to Swedish municipalities, between 1998 and 2002.

• This evaluation covers programmes for which final reports have been submit-ted. Those programmes have received SEK 1.8 billion out of total approved funding of SEK 6.2 billion. Programmes receiving funding totalling SEK 4.7 billion are expected to be completed.

• The main aims of LIP were environmental improvements using new tech-nologies and new approaches, and also reduced unemployment.

• Grants were only available for measures that had not been begun and did not form part of the principal's normal operations.

• The LIP process consisted of three main stages: (i) application; (ii) implemen-tation; and (iii) final report.

Background and scope of the

evaluation

This chapter defines the purpose of the evaluation, the approach chosen and the resulting delimitations. A brief description of the reference group for the project is also given.

Reason for the evaluation

The report addresses some socio-economic aspects of the investment programmes that have been implemented. This evaluation forms part of a wider evaluation of LIP, whose various parts are being carried out at the instigation of the Swedish EPA.

This evaluation is based on the premise that the aim of the government funding is to pro-vide maximum benefit for the public money invested. The assignment therefore includes defining the aims of LIP, ie, the intended benefit, so that a relevant assessment can be made. One difficulty in evaluating LIP is that one aim has been to achieve highly cost-effective funding, but that the measures implemented should not be financially profitable. It is there-fore of interest for this report to examine the way the projects and the reports on them (eg, investment assessment and appraisal of environmental effects) have developed before and during project implementation. Long-term project development, including the technical life-span and economic stability of investments, is also relevant, since it determines the extent of the total impact of the projects.

An evaluation of an instrument from a socio-economic perspective may be made in rela-tion to two types of effectiveness. Actual achievement of quantitative objectives can be ex-amined. Another kind of effectiveness is whether development in a given direction at a low cost is achieved. The second type of effectiveness is the one most relevant to evaluation of local investment programmes. But one basic problem is that several instruments act together in a way that sometimes makes it difficult to determine the significance of an individual instrument.

Focus and delimitations of the evaluation

A complete socio-economic analysis requires that account be taken of all positive (income) and negative (cost) effects, and that these be allocated in relation to the relative importance of the various objectives. This is not possible in this case. The measures taken under the local investment programmes span a long time horizon and consist of projects that vary in scope, location and approach.

This evaluation is based on programmes completed and entered in the Swedish EPA database in June 2004. This means that 101 of the 211 LIP programmes are repre-sented here. The grant funding component for those programmes is approximately SEK 1.8 billion, which may be compared with an expected total of SEK 4.7 billion

This project is confined to measures in the same fields and having similar environmental objectives. The environmental objectives that the evaluation focuses on are carbon dioxide, sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxides, and the projects concerned relate mainly to energy and traffic. The main reason for this delimitation is the availability of quantified data and the ability to produce relevant key figures.

These emissions reflect the transition from using fossil fuels to renewable energy sources and various ways of improving energy and resource-use efficiency. The conclusions drawn in this evaluation project are of importance for the ongoing discussion of this transition and how to design appropriate instruments for achieving it. Specifically, lessons can be learnt from this evaluation for the present funding system – Klimp (Climate Investment Pro-gramme).

The socio-economic dimension of this evaluation is mainly a national one, ie, LIP as a whole. Local socio-economic effects, such as the socio-economic impact of the measures based on local reference cases, is not involved.

An additional option under the terms of reference was to evaluate the effects of LIP on employment. Since it has become evident that the aim of reducing unemployment, particu-larly in the early stages, was of great importance, the evaluation includes the impact of LIP on employment. We also discuss the allocation of grants in relation to levels of employment in municipalities involved in LIP. The evaluation of LIP and employment covers the 101 programmes on which final reports have been submitted, except for the review of grant ap-portionment, which includes all programmes for which grants were awarded.

The consideration that was to be given to architectural qualities and sexual equality has not been evaluated (mainly owing to a compendious and unmanageable body of reporting material). However, there is a qualitative discussion of the impact of LIP on new technolo-gies and new approaches.

The fact that this evaluation is one of a series of evaluations (see Appendix 1) has influ-enced the emphasis we have chosen. There will be a degree of overlap, however, and some measures will probably not be covered by the overall evaluation initiated by the Swedish EPA.

Discussion of objectives

As mentioned above, the aim of state-funded instruments is to produce maximum benefit per krona invested. Benefit is a relative concept, depending on the object of the instrument. In the case of LIP, there are several aims, which very much complicates an evaluation.

It used to be thought by many officials in the Swedish Government administration that trying to achieve several objectives simultaneously by using a single measure was risky and contrary to sound principles governing the use of political instruments. One reason given in support of this view is precisely that it is then difficult to evaluate the effectiveness of the measure. But the tradition of using single measures to achieve multiple goals is more firmly established in the EU. The reason given for this approach is that measures having several positive effects can help to achieve a better overall level of socio-economic effectiveness. LIP is an example of a measure of this kind at national level. This kind of evaluation may therefore become increasingly important.

During the lifetime of the LIP programme there have been changes in the LIP ordinance itself and in the administration of the municipal programmes. But most of all, the objectives

have changed. The main underlying aim of LIP was to increase employment. It was easier to politically justify environmental investments, since they were combined with the employ-ment goal (Eriksson, 25 October 2004). The focus shifted increasingly to environemploy-mental effects when responsibility was delegated to the Ministry of the Environment, and later to the Swedish EPA. Another reason for this was the drop in unemployment towards the end of the LIP era.

The project application discusses the possibility that this evaluation could seek to iden-tify key figures for individual objectives, as well as for combinations of objectives. The indi-vidual objectives – a reduction in negative environmental impacts and increased employment – will be assessed separately. However, it has proved difficult to make an allocation between various objectives. For instance, it has not been found to be feasible or worthwhile to weight the value of a person year in comparison with the value of a one-tonne reduction in carbon dioxide. The effects of using this method are discussed in relation to the individual key fig-ures.

Suitable priorities for the evaluation have been identified in discussions with the refer-ence group. One central strategy has been to use the quantitative estimates and visits to the municipalities as a basis. Other aspects, such as effects on dissemination of technologies and competition, are addressed in the concluding qualitative discussion.

Reference group

To support the evaluation process, the Swedish EPA appointed a reference group, which contributed comments on the emphasis, methods and reporting at three meetings during the course of the project. A brief presentation of the members of the reference group is given below.

• Anna Bergek, a lecturer at Linköping University, researching in industrial dy-namics.

• Professor Roland Clift, University of Surrey, who has many years' experience of manufacturing industry, as well as analysis and strategies for development of environmental technologies.

• Professor Marian Radetzki, Luleå Institute of Technology, an economist, whose research deals with the economics of natural resources and the interac-tion between markets and politics.

• Professor Thomas Sterner, University of Gothenburg, an economist specialis-ing in the economic characteristics of environmental policy instruments. • Lars-Christan Roth, Swedish EPA (until June 2004).

• Ingvar Jundén, Swedish EPA (from September 2004).

Summary

• The evaluation assumes that the Government expects maximum benefit to be derived from the state funding, based on stated objectives.

• The fact that LIP has had multiple objectives has been found to render the evaluation more difficult.

• This evaluation addresses the effects of LIP on the environment and employ-ment from a socio-economic perspective. This has been done by producing key figures and also by means of a qualitative discussion.

• A reference group comprising four researchers in economics, environmental technology and industrial dynamics, together with a representative from the Swedish EPA, have met regularly to comment on the reports we have made, thereby contributing to the evaluation.

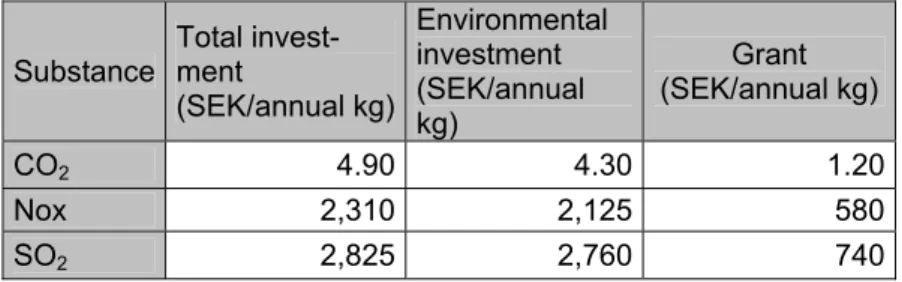

Grant effectiveness

The cost of grants for investment in carbon dioxide emission reductions is SEK 1.20/kg of recurring annual reductions. Taking into account project lifespan and interest, the state investment cost is estimated at SEK 0.12/kg CO2.

Summary of findings

This section summarises the findings of the evaluation. More specific results and discussions are presented in the following sections.

Estimates based on reported reductions in emissions to air show a significant impact and a high level of effectiveness. Total Swedish emissions of carbon dioxide have fallen by one per cent as a result of the local investment programmes on which final reports had been submitted at the time of this study (approximately 50 per cent of the total number of pro-grammes). The cost to the state of these emission reductions has been limited in relation to the socio-economic value reflected by environmental taxes on the same emissions.

The environmental tax on carbon dioxide may serve as a measure of the societal valua-tion of emissions. Using this measure, a clearly positive result has been achieved from a socio-economic viewpoint. One reason for this is that LIP measures have largely been car-ried out in sectors in which there is a reduced environmental tax on emissions or no tax at all. Measures in sectors with a lower tax rate account for 40 per cent of the carbon dioxide emis-sion reductions achieved under the 101 programmes that have been evaluated. Moreover, those measures have a better average level of grant effectiveness than other measures.

Measures to reduce carbon dioxide emissions appear to be even more

socio-economically cost-effective, bearing in mind that they were decided at a time when the car-bon dioxide tax was less than half its present level. If the present tax is used as the value of the reduction, then projects in taxed sectors are clearly cost-effective. After all, the current tax rate is higher than the tax plus LIP funding per kg of emission reduction when the meas-ures were decided.

Creation of employment was originally an important objective of LIP. The direct effects have meant the creation of approximately 8,400 jobs at a reasonable cost to the state. How-ever, we have found no signs that the effects on employment have been a consistent priority objective. For example, it is not so that more grants have been paid out to municipalities with high levels of unemployment.

Indirect effects include two effects that appear to be important and substantial in com-parison with the direct effects described in the project reports. First of all, there are several projects in which waste heat from manufacturing plants has been utilised for district heating purposes. This has generated an additional source of operating income for those plants. This income makes the factories more competitive and reduces the risk of them being closed down if a recession were to hit their industry.

In the second place, many measures have increased the use of biofuels. Biomass produc-tion by the forestry sector for energy purposes creates long-term job opportunities in forest regions. These are also the regions where unemployment is highest and where increased employment can have the greatest socio-economic benefits. The number of permanent jobs

created in this way can be assumed to be approximately equal to the number of job opportu-nities reported by all LIP projects together.

In addition to specific socio-economic benefits related to emission reductions in untaxed sectors, a number of other positive effects resulting from LIP have been identified. Effects such as the fact that knowledge is disseminated, new technologies are tried out and compa-nies supplying more sustainable technical systems gain a stronger position are important. However, it has been difficult to quantify these effects, although we do have examples of best practice. One difference of relevance in industrial terms is that LIP has provided support for customers in the process of procuring technical solutions. Many other forms of support have been aimed at suppliers of new technology.

There are shortcomings in the reports, but a review of the database has not revealed any systematic errors enhancing the final results. Our random samples among municipalities also support these findings. Our visits to municipalities instead revealed that the reporting of effects contained underestimates. There are clear examples of measures that have obviously reduced emissions directly as well as indirectly, but where these have not been quantified in the final report. Moreover, the study reveals several instances where the quantified effects are lower than the actual outcome. A calculation based on converting from use of oil to bio-fuel showed that carbon dioxide emissions were reduced by a figure of around 100,000 ton-nes in addition to that which had been reported in the database.

Results reported and actual results are thus better than those suggested by earlier reports based on applications and grant awards3. We have identified two mechanisms capable of explaining this. The first we call progressive selection. This mechanism means that the various stages of the LIP process have eliminated the measures that have been less cost-effective and have had less environmental impact. One observation is that after funding has been granted by the state, in some cases municipalities or those responsible for implementing the measures have chosen not to carry out any projects, even though a grant has been

awarded. Projects have also been discontinued when it has been discovered during imple-mentation that they would be more costly or less effective than planned. Hence, the elimina-tion process has been more extensive and has involved more steps than expected.

The second process, in this report called constructive evolution, means that flexibility on the part of the Ministry of the Environment, and later the Swedish EPA, has enabled measures to be developed within the framework of the approved funding. This flexibility has allowed changes that have improved the results. But the authorities have adhered to the prin-ciples of never increasing the size of the grant ultimately paid out. This has capped the cost to the state and ensured that account has been taken of cost-effectiveness in the municipali-ties.

Socio-economically speaking, it is also important that LIP has been found to produce so-lutions that, over time, have become commercially viable and competitive. Higher oil and electricity prices, higher green taxes, the EU scheme for trade in emission rights and the EC Waste Directive have rendered many projects more profitable than could have been foreseen.

3

Investigative method

This section presents the methods used in this evaluation. The various sub-studies made are described, and selection, representativeness and quality of the data gathered are discussed.

Levels of evaluation

This report has three main parts: (i) an overall study (ii) a municipal study; and (iii) an indus-try-specific study evaluating projects in the same sector. Table 2 shows a diagram illustrating the various levels of LIP to aid understanding of the methods used in this report.

Table 2 Analysis levels

Overall study

In the overall study we have made calculations using the database. These calculations in-clude 101 programmes on which a final report has been submitted. Calculations have been made of quantified environmental impacts in the form of carbon dioxide, nitrogen oxides and sulphur dioxide, as well as quantified effects on employment.

Municipal study

The municipal study is both quantitative and qualitative. Here we have chosen to examine more closely the projects quantifying effects in the form of emission reductions of CO2, NOx and SO2 in 10 selected municipalities.

The projects concerned are mostly in the following sectors. • Traffic (eg, public transport, biogas fuel)

• Conversion to use of renewable energy (eg, heating using biofuels, solar en-ergy)

• Improved energy efficiency (eg, energy saving in homes, energy-efficient climate and lighting control systems)

• Waste (eg, biogas unit)

Some projects included in the municipal study are not included in the calculations made in the overall study. There are instances where municipalities have taken measures that ought to

Nationell niv

Kommunnivå Huvudmannaniv Measure Measure Measure

Program

Measure Measure Program

Measure Measure Measure Program LIP Sektornivå / National level Municipal level "Principal" level

Measure Measure Measure

Programme

Measure Measure

Programme

Measure Measure Measure

Programme

LIP

have an impact on CO2, SO2 and NOX but where those impacts are not recorded in the data-base. These have therefore not been included in the municipal study.

The interviews at municipalities gave us an idea of the quality of reporting and how the calculations in the overall study may be interpreted. In some cases final reports were submit-ted on programmes before the investments were fully in operation. The municipal study therefore helped us to ascertain how well the final results as set out in the final reports re-flected reality one or a few years later. A list of the measures discussed in the ten selected municipalities is given in Appendix 2.

The municipal study of LIP is a way of gaining an impression at local level. We wanted to see that the investments had resulted in economically sustainable facilities that were also working as planned and reported. We also wanted to learn to understand the way state fund-ing affects processes in municipalities.

The evaluation focused on measures to reduce emissions of CO2, NOX and SO2. The conclusions drawn cannot therefore be directly extrapolated to other LIP measures (waste reduction, public education projects etc).

Industry-specific study

This evaluation also includes a project focusing on an individual sector: the pulp and paper industry. The project has been carried out in the form of a university dissertation and will be reported separately as such. Selected parts of the study are included in this report. Where reference is specifically made to "the study on the pulp and paper industry", this is entirely based on Forssman (2004).

The pulp and paper industry is of great interest, since these projects account for a large proportion of the funding paid out and the environmental effects achieved. Four projects have been examined. These involve use of sludge from pulp and paper manufacture as a biofuel, and use of waste heat. The main purpose of the dissertation was to examine whether investment in these projects was socio-economically beneficial. Given current conditions, with high oil and electricity prices, waste taxes and the introduction of the electricity certifi-cate scheme, these projects have clearly been profitable. The dissertation also examines whether profitability could have been predicted at the time of application, the pros and cons of grants of this kind for industrial projects and the nature of the benefits to society.

Data gathering and selection

As mentioned earlier, the database on which the general calculations have been based con-tains quantifiable data on 101 programmes out of a total of 211. Hence, account has only been taken of projects that have been completed and on which a final report has been submit-ted to the Swedish EPA. The final reports have been obtained from the EPA or from the municipalities included in the study of ten municipalities. A review of these has provided additional information prior to the interviews and has enabled us to check the reasonableness of the data fed into the database.

Interviews have been conducted "on the spot" in each municipality. In some cases there have been follow-up interviews with additional municipal representatives by phone and e-mail. The visits to municipalities have combined interviews with visits to various facilities where this has been of interest.

Information from other evaluations and other information on LIP has also been studied where considered relevant. In most of the municipalities studied other studies have also been made, which we have read.

Data quality

The information in the database is based on information supplied by the municipalities them-selves, as reported to the authority. There are some problems with the quality of the data in the database. Some corrections have therefore been made where obvious errors have been detected (eg, duplicated reporting on environmental effects, non-entry of environmental effect). To make it easier to reproduce our calculations, the corrections we have made are shown in Appendix 3. No further corrections have been made in the key figure calculations, but some adjustments have been made in relation to certain other calculations, where this is clearly stated.

There is no standard method of calculating environmental effects in final reports. An analysis has therefore been made of the sensitivity of certain key data in the database. In addition, a general aim of the municipal study has been to gain an idea of the quality of the data and how well it reflects reality. A fairly high proportion of the projects included in the key figure calculations have also been included in other evaluations. Those other evaluations have obtained additional information using questionnaires and interviews covering a large number of measures and municipalities4. This has further enhanced the quality of our data and results. Additional issues have been resolved with the help of telephone calls and e-mail.

Data quality is discussed in further detail in the presentation of results.

Selection of municipalities and their representativeness

The municipal study forms one part of this evaluation. Ten programmes in ten municipalities were selected for closer study. Those projects represent around ten per cent of the total num-ber of programmes in the database on which final reports have been submitted, and 15 per cent of the grants paid out to date under the LIP scheme.

In selecting municipalities, account was taken of the size and content of the programmes, the size and geographic location of the municipality and the year the programme application was submitted. The selection is shown in Table 3.

4

Swedish EPA (2004). Bättre miljö med utbyggd fjärr- and närvärme. En utvärdering av LIP-finansierade fjärr- och

närvärmeprojekt ("A better environment by developing district and local heating") - an evaluation of LIP-funded

district and local heating projects. Report 5372. Swedish EPA (2004). Goda möjligheter med spillvärme. En

utvärde-ring av LIP-finansierade spillvärmeprojekt . ("Waste heat potential" - an evaluation of LIP-funded waste heat

Table 3 Municipalities included in the municipal study

Municipality LIP year Total investment* Grant paid No. of inhabitants** County

Kristianstad 1998 SEK 351,967,087 SEK 69,963,310 74 161 Skåne

Trollhättan 1998 SEK 157,855,464 SEK 27,133,823 52 891 Västra Götaland

Umeå 1999 SEK 88,108,198 SEK 19,069,524 104 512 Västerbotten

Solna 1999 SEK 198,029,974 SEK 48,476,655 56 605 Stockholm

Hedemora 1998 SEK 100,192,708 SEK 21,913,320 15 857 Dalarna County

Karlshamn 2000 SEK 68,477,722 SEK 14,937,715 30 741 Blekinge County

Hässleholm 2000 SEK 30,558,727 SEK 9,467,100 48 580 Skåne

Göteborg 1998 SEK 288,021,455 SEK 60,055,956 466 900 Västra Götaland

Linköping 1999 SEK 216,537,161 SEK 40,929,002 133 168 Östergötland

Karlstad 2000 SEK 83,616,436 SEK 23,322,056 80 323 Värmland

Total SEK 1,583,364,932 SEK 335,268,461

* Investment in measures receiving grant funding ** In 2000

In total, grants were awarded for 176 measures in these municipalities. Measures actually implemented totalled 140; approximately 65 per cent of the funding granted was used.

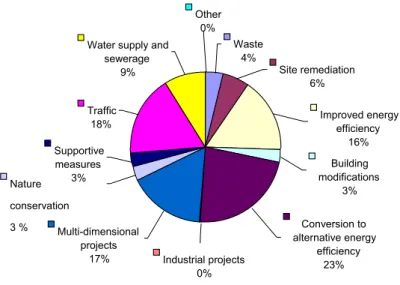

All measures under LIP have been classified into groups and sub-groups. One objective of the selection process has been to ensure that it remained within the confines of reasonable representativeness in this respect as well. Figure 1 shows a breakdown of funding between the various groups. The breakdown includes grants paid out under the 101 programmes in the database on which final reports have been submitted.

Figure 1 Breakdown of grants paid out to the programmes on which final reports have been submit-ted (101) Conversion to alternative energy effiency 34% Building modifications 2% Improved energy effeciency 11% Site remediation 6% Waste 7% Water supply and

sewerage 9% Traffic 13% Supportive measures 3% Nature conservation 5% Multi-dimensional projects 9% Industrial projects 1%

Figure 2 shows a breakdown between various categories in the municipalities selected for closer study.

Figure 2 Breakdown of grants paid out per category in the ten municipalities studied

The breakdown of grants differs somewhat between the municipalities studied and the total grants disbursed under LIP. This is mainly because one major multi-dimensional project, representing a quarter of all funding so far granted to multi-dimensional projects, has been implemented in one of the ten selected municipalities.

However, the most important consideration is that the types of measure on which this study focuses - conversion to renewable energy sources, improved energy efficiency and traffic - do not differ substantially from one another when broken down into their compo-nents.

Summary

• The study comprises three elements: an overall study, a series of study visits to ten municipalities and a specific study of some projects in the pulp and pa-per industry.

• The entire evaluation is based on a database covering the programmes on which final reports have so far been submitted: 101 programmes out of a total of 211.

• Account has been taken of some shortcomings in the quality of the data in the database. Necessary corrections and a check of the sensitivity of the data have been made.

• The following municipalities are included in the municipal study: Kristian-stad, Trollhättan, Solna, Hedemora, Umeå, Hässleholm, KarlKristian-stad, Linköping, Gothenburg and Karlshamn.

• The municipal study gave indications as to the quality of the data and infor-mation about the way municipal processes had worked.

Industrial projects 0% Multi-dimensional projects 17% Nature conservation 3 % Supportive measures 3% Traffic 18%

Water supply and sewerage 9% Waste 4% Site remediation 6% Improved energy efficiency 16% Building modifications 3% Conversion to alternative energy efficiency 23% Other 0%

Evaluating instruments

When evaluating an instrument it is relevant to discuss it in relation to other instruments. In this section LIP will primarily be seen in terms of its role as an environmental policy instru-ment. A comparison with other measures to reduce unemployment is made in the chapter entitled "Impact on employment”.

Types of instrument

It has been recognised that state intervention is necessary to tackle environmental problems. This is because activities in our society, such as industrial operations, have direct and indi-rect negative external effects on the environment and human health. The current debate in the field of environmental economics is not so much about whether the state should inter-vene; it is more a question of how and to what extent it should act. The state must therefore choose between a number of instruments of various kinds.

According to Vedung (1998), there are many ways of classifying instruments. One can choose not to classify them at all, ie, to list all conceivable instruments, or to classify them according to various viewpoints and characteristics. But Vedung advocates dividing instru-ments into three categories, which we have also chosen to do.

The basic idea of informative instruments is that well-directed information and educa-tion and training projects will change attitudes among the target group and encourage a change in behaviour. This should be distinguished from information about instruments.

Eco-nomic instruments are those using price and market mechanisms. Under this category we

find subsidies, grants and flexible mechanisms such as trade in emission rights and certifi-cates. Administrative instruments are mandatory. They include prohibitions and permit requirements.

But one problem of classification is that, as a rule, there are always instruments that fall outside the chosen classification and that certain classifications are debatable. Trade in emis-sion rights, which was placed in the economic instrument category above, is one such exam-ple. Trade of this kind is dependent on a legislative (administrative) quota, yet the resulting improvements are largely dependent on the economic incentives created by trade in emission rights. Voluntary agreements also represent a grey area. A voluntary agreement is where, for example, a given sector agrees with the state that it will reduce its use of natural resources or emissions. These agreements may be linked to a reduction5 of a tax or an underlying threat of administrative action or a new tax, however.

It is considered beneficial to combine instruments. The combination chosen depends on the nature of the environmental problems, as well as the market and actors potentially af-fected by the instrument.

According to basic economic theory, those responsible for negative impacts should also pay for them. Pigouvian taxation6 of adverse environmental impacts means that improve-ments are achieved where they are cheapest. To some extent, subsidies have similar

5

In the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, energy-intensive companies have voluntarily agreed to improve their energy efficiency in return for lower energy taxation. There is a proposal before the Swedish Parliament to introduce exemption from electricity tax for energy-intensive enterprises that enter into a voluntary energy-saving agreement. 6

cal effects on the willingness of industry to invest if the subsidy is related directly to the emission reduction. But subsidies, unlike taxes, may allow a number of enterprises at the margin to remain in the market (Sterner, 2003). Another factor is that, generally speaking, subsidies are not desirable since they depart from "the polluter pays" principle.

An instrument may have various kinds of effect at various levels. Environmental prob-lems may occur locally but have an impact globally as well as locally. This may also serve to determine which instruments are effective. The solution considered optimal from an envi-ronmental viewpoint is preventive behaviour, ie, improvements occur at the beginning of a process, not merely as a result of improved cleaning or treatment techniques. Instruments offer varying potential in relation to this, and this is one reason that non-administrative in-struments such as subsidies and information campaigns are used.

One argument in favour of a given instrument is cost-effectiveness. Another is legiti-macy, ie, how it is perceived by those affected by it, which may in turn influence their be-haviour. According to van der Doelen (1998), instruments may be assumed to have a

repres-sive role as well as a stimulating one. But he considers that one should be wary of imputing

too strong a correlation between the legitimacy of an instrument and its effectiveness. Van der Doelen (1998) is also of the opinion that instruments are often designed according to the principle of "give and take". Legitimacy is then created by first introducing informative and positive economic instruments, and then more direct administrative and economic sanctions to achieve maximum effect.

Evaluation methods

As discussed above, there are other aspects of instruments apart from their specific quantifi-able impact on a given type of environmental problem. Evaluation criteria are therefore the subject of much discussion in economic theory. The criteria chosen may depend on the aims to be achieved by the instrument. But in practice the criteria used are often those seen by the evaluator to be adequate for his specific analysis.

The economic effect, ie, the cost-effective achievement of the stated aims, is often cru-cial. With schemes like LIP, which have a diversity of aims, multi-dimensional in them-selves, and which are intended to help bring about a systemic change, it is important to ex-amine the instrument from several angles. This is essential so to arrive at a socio-economic perspective. However, bearing in mind the multi-faceted objectives and the number of meas-ures involved, a complete socio-economic analysis is not possible.

A number of criteria considered relevant to this evaluation are given below. These will be discussed indirectly in the following sections and directly in the concluding discussion of LIP as an instrument.

• Is it an appropriate instrument for achieving the objectives? (APPROPRIACY)

• Have the desired effects been achieved with the help of the instrument? (EFFECTIVENESS)

• How much has it cost the state to achieve these effects? (GRANT EFFECTIVENESS)

• Is this an instrument that creates incentives for continuing efforts to achieve the objectives, even without further instruments among the actors affected by it? Has it had lasting effects? (ENDURING EFFECTS)

• How well has the instrument been received and the distribution of the effects perceived? Has the process been an open one? (OPENNESS AND

DISTRIBUTION)

The above illustrates a need to see the "benefit" of an instrument in a broader perspective than merely in mere terms of its grant effectiveness. Hence, when evaluating LIP, it does not suffice to examine specific grant effectiveness alone. More long-term effects and the re-sponse of the market to LIP as an instrument are also relevant. A further relevant factor is the scope for using a similar funding system in the future.

As mentioned earlier, it is desirable to be clear about the objectives in order to under-stand that which is to be evaluated. This study and our evaluation focused initially on the environmental effects. As part of our evaluation, we identified the original aims by inter-viewing those who had initiated LIP. It was clear from those interviews that the employment objective had been paramount at the time. Thus, it is quite evident that LIP had a number of objectives. It has never been solely a matter of grant effectiveness; the aim has also been to demonstrate new technology and to initiate a learning process via cooperation.

It is necessary to base this evaluation on a reference case to make it clear what the find-ings are being measured against. One key question is:

What would have happened without funding?

This is discussed to some extent in this study, partly by way of the municipal interviews. In addition, the taxes and charges on the estimated emissions of CO2, SO2 and NOX, will be used as a reference when assessing the key figures. The reference case for employment is confined to existing retraining and job creation schemes.

Summary

• Political instruments may be classified into three main types: informative,

administrative and economic.

• LIP must be evaluated not merely in terms of pure grant effectiveness, but also in the light of other factors such as the appropriacy and enduring effects of programmes.

• A key question to be borne in mind is what would have happened without funding.

Findings

This section begins with an appraisal of reporting by municipalities, the emphasis being on those that have been the subject of closer study. This is followed by an assessment of the extent to which objectives have been achieved and a discussion based on the evaluation cri-teria set out earlier.

Municipal assessments and reporting

This section outlines reporting by municipalities and conclusions drawn from the interviews on reporting.

General quality of reporting

One definite observation is that the quality of final reports varies. The extent to which quan-titative effects are described differs. But the main variation between reports concerns the general account of measures and their other effects.

In the municipalities visited, we saw no clear link between the quality of the final report and how well the LIP measures had been carried out. In some cases final reporting has been hindered by the fact that different people have had coordinating responsibility during the course of the programme, or the coordinator has left the project entirely before it was com-pleted.

Investment assessments

As a rule, there has been no requirement that the principal responsible for the measures should submit a detailed account of the investment assessments forming the basis for the application. According to the municipalities themselves, it has been difficult to assess in-vestments, since it is hard to estimate costs, particularly when tenders have to be invited for major contracts. A requirement for grant eligibility was that the measures had to still be at the planning stage, and so exact cost estimates were not usually available. The assessment was even more difficult where new technologies were to be procured. The authorities, too, found it difficult to accurately assess whether cost estimates were reasonable.

Calculating quantitative environmental effects

The reporting of environmental effects varies greatly from one municipality to another and from one measure to another. When they submitted their applications, municipalities did not receive any instructions as to how quantitative effects were to be calculated or estimated. In some cases a coordinator submitted reports based on information supplied by the principal; in other instances information came from each project leader. Hence, calculation methods differ. For example, one municipality reported "reduction in number of vehicle kilometres", whereas another also made an estimate of reduced emissions to air resulting from the reduc-tion in vehicle kilometres. It is not quite clear to what extent this is due to a lack of clear instructions, or a greater desire on the part of some municipalities than in others to submit detailed reports.

One reason for caution has been a desire to avoid double-counting the effects of meas-ures that are part of large projects involving a number of programmes. For instance, a

mu-nicipality may have a biogas project involving extension of the gas supply system under one LIP programme, and gas-driven vehicles under another. There is then a risk of the munici-pality counting the effects twice.

The municipalities mentioned that they usually chose to err on the side of caution in their reporting so that it would be easier to defend the figures in any discussion of the final report. As a rule, they reported the figures they needed to receive a grant, nothing more.

The effects of these differences in calculations and report are discussed further in relation to the calculations of the key figures.

Reporting of effects on employment

As discussed earlier, one of the aims of the funding scheme for local investment programmes was to help fight the country's relatively high level of unemployment at the time. In addition, municipalities were required to show in their application that the programme could be ex-pected to have this effect.

Effects on employment have been presented in the reports in the form of person years and permanent jobs. The term "person year" is defined as 12 months' full-time employment and "permanent jobs" are the new, permanent employment opportunities created as a result of the investment. Municipalities themselves have been allowed to decide what constitutes a permanent job.

The municipal study has revealed that there are also differences in the way municipalities report effects on employment. One example of differences is the way that indirect effects have been calculated. In some cases account is taken of effects among suppliers, in others only the direct effects of the measure. Reporting the hours spent by the principal itself has also been considered difficult. The view generally expressed by municipal officials is that assessment of employment effects is complicated.

As with environmental effects, it has been apparent that municipalities have chosen a cautious approach. Only in a few isolated cases have municipalities gone beyond the meas-ure itself and estimated the indirect effects.

Emission reduction effects

One aim of this evaluation is to use key figures to evaluate the effectiveness of LIP projects. We have studied well-quantified effects in the form of reduced emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2), nitrogen oxides (NOx) and sulphur dioxide (SO2).

Before presenting our estimates of effectiveness, it is of interest to examine the direct ef-fects resulting from LIP investments. Significant emission reductions have been achieved even under the 101 local investment programmes included in this study. The results are shown in Table 4.