(Un)Deliberate

Choices of Dubious

Funds in the

Swedish Pension

System

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Economics

NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Civilekonomprogrammet

AUTHOR: Isabella Emanuelsson

TUTOR: Paul Nystedt

JÖNKÖPING05 2020

Which Individuals Choose Dubious Funds Within the

Swedish Pension System?

Abstract

There are ongoing discussions about a new reform of the mandatory fully funded individual accounts in the Swedish public pension system. Since the initial round in 2000, several funds have been excluded from the platform due to deceptive, and sometimes criminal, behavior towards the consumers. This paper analyzes which individuals that have invested in these funds, examines possible explanations for this, and sheds light on the current structure of the Premium Pension Scheme. By using a rich dataset on 650,000 individuals that consist of both those who have been in six particular dubious funds and a random sample of the rest of the Swedish pension savers, the variables of interest are evaluated in a logistic setting. The results show that individuals who are men, unmarried, divorced, in their older-middle age, have lower-incomes, live in rural areas, and the North of Sweden are more likely to have invested in one of the dubious funds. The results also reveal that some funds have clearer target-groups, while others have targeted more randomly. The study emphasizes the need for improving people’s financial decision-making through improved information.

Keywords: retirement planning, pension funds, Swedish pension system, behavioral economics, financial literacy, deceptive marketing, aggressive sales methods, logistic regression, linear probability model

Isabella Emanuelsson, Jönköping International Business School, Gjuterigatan 5, SE- 553 18, Jönköping, Sweden

Table of Contents

1

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Problem Statement ... 3 1.3 Purpose ... 4 1.4 Delimitations ... 4 1.5 Structure ... 42

Background Information on the Funds ... 5

2.1 Allra ... 5 2.2 Falcon Funds ... 6 2.3 Solidar ... 6 2.4 GFG ... 6 2.5 Fondeum ... 7 2.6 Advisor ... 7

3

Literature Review ... 8

3.1 The Swedish Pension Reform ... 8

3.1.1 Development of the Reform ... 8

3.1.2 The Premium Pension ... 9

3.1.3 Engagement in the Individual Accounts ... 9

3.2 Behavioral Economic Theory and Rationality ... 10

3.2.1 Bounded Rationality and the Role of Institutions ... 11

3.3 Heuristics and Biases in Retirement Investment Decisions ... 12

3.3.1 Hyperbolic Discounting ... 12

3.3.2 Information Overload ... 13

3.3.3 Limited Attention ... 13

3.3.4 Status Quo Bias ... 14

3.3.5 Trust Heuristic ... 14

3.4 Framing and Advertisement ... 15

3.4.1 The Role of Advertisement ... 15

3.4.2 Social Pressure and Persuasion ... 15

3.5 Financial Literacy and Engagement in Retirement Planning ... 16

3.5.1 Financial Literacy and Sensitivity to Information Overload ... 16

3.5.2 Gaps in Financial Literacy ... 17

4

Hypothesis Development ... 18

5

Methodology ... 20

5.2.1 Linear Probability Model ... 22

5.2.2 Logistic Regression ... 23

6

Empirical Findings and Analysis ... 24

6.1 Descriptive Statistics ... 24

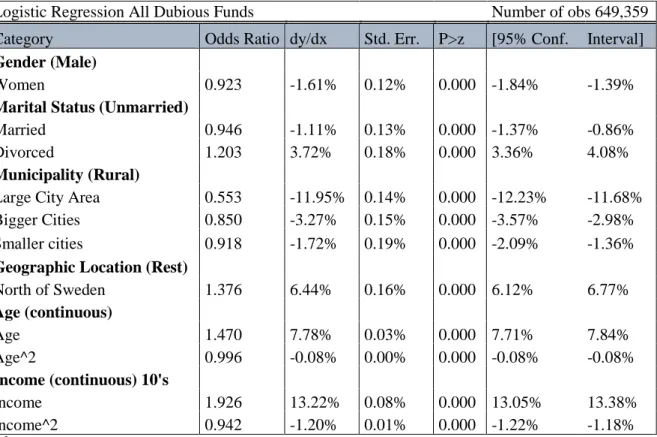

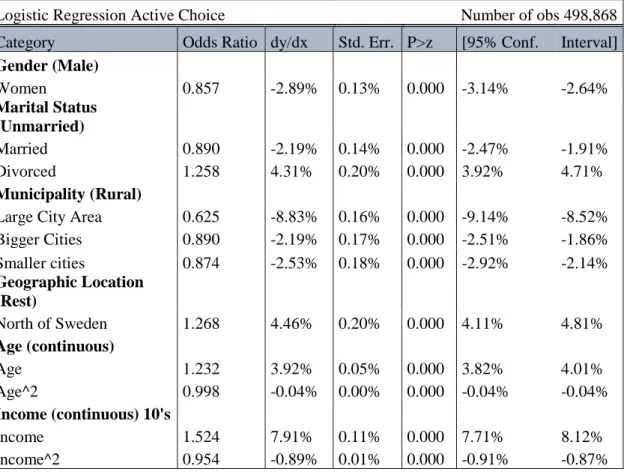

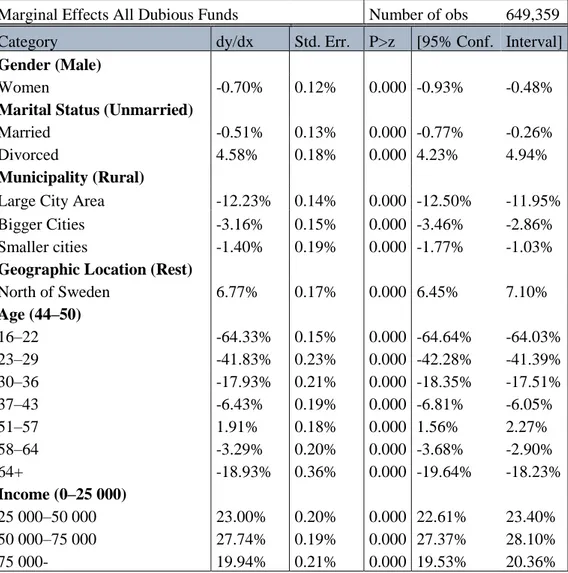

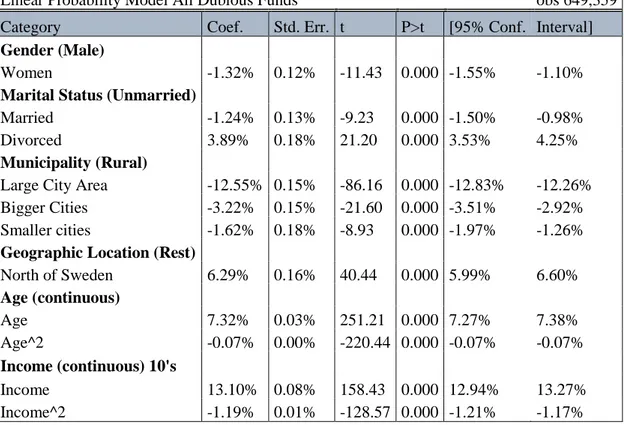

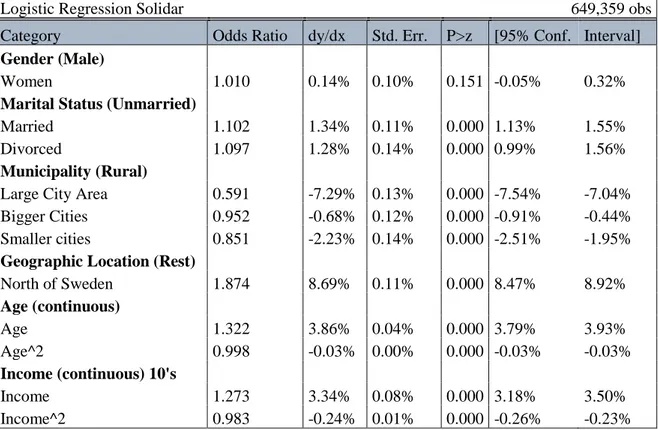

6.2 Multiple Regressions ... 26

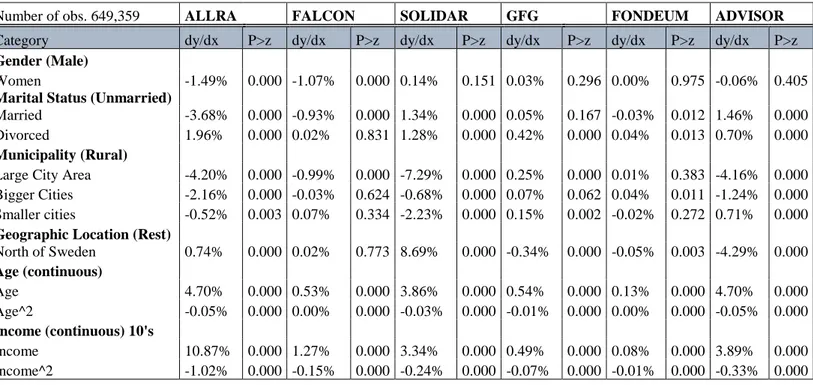

6.2.1 Differences Between the Funds ... 28

6.2.2 Allra ... 28 6.2.3 Falcon Funds ... 29 6.2.4 Solidar ... 29 6.2.5 GFG ... 29 6.2.6 Fondeum ... 29 6.2.7 Advisor ... 30 6.3 Robustness Analysis ... 30 6.4 Sensitivity Analysis ... 30

7

Conclusion ... 33

8

Discussion ... 35

8.1 Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research ... 36

References ... 37

List of Tables

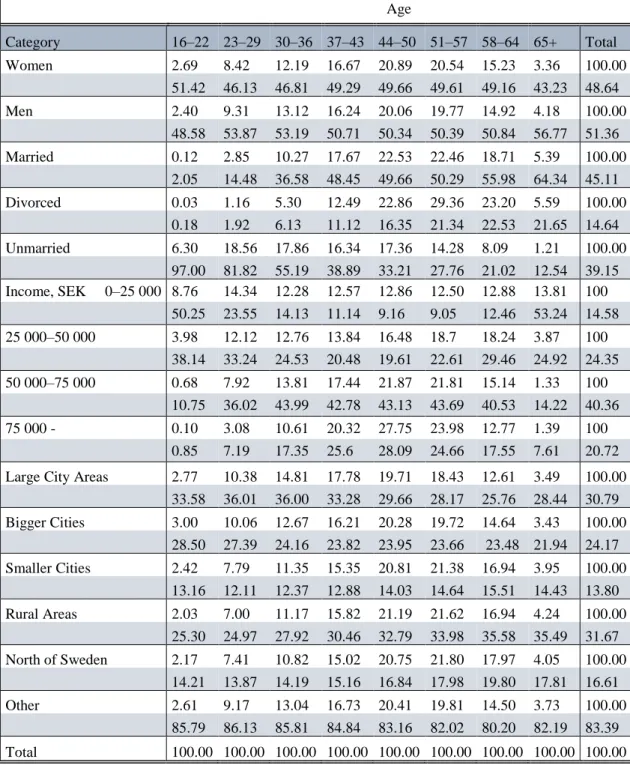

Table 1. Distribution of individuals’ characteristics in 2017 in percentages ... 21

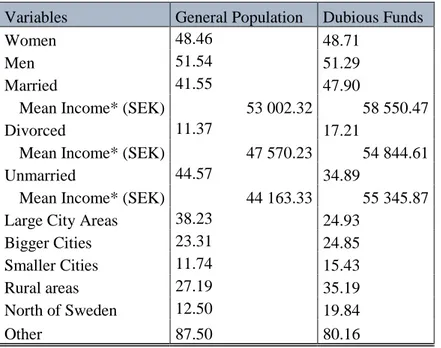

Table 2. Comparison of the two population groups in percentages (within column) ... 24

Table 3. Logistic regression with odds ratios and average marginal effects ... 26

Table 4. Average marginal effects for the different funds ... 28

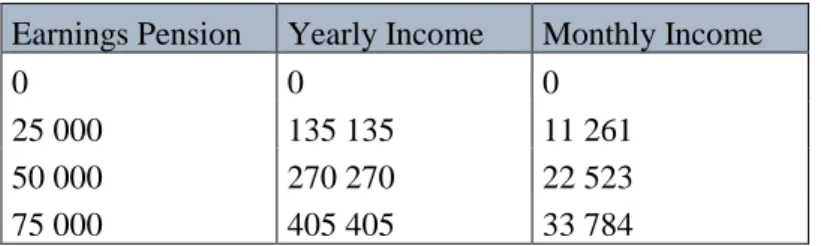

Table 5. Logistic regression on individuals who have made an active investment decision . 31 Table 6. Transformation of earnings pension into yearly and monthly income ... 40

Table 7. The median income in earnings pension in yearly and monthly income ... 40

Table 8. Yearly income and distribution of earnings of the two datasets ... 40

Table 9. Average marginal effects of performing logistic regression ... 41

Table 10. Linear probability model robust standard errors ... 42

Table 11. Logistic regression Allra ... 42

Table 12. Logistic regression Falcon Funds... 43

Table 13. Logistic regression Solidar ... 43

Table 14. Logistic regression GFG ... 44

Table 15. Logistic regression Fondeum ... 44

Table 16. Logistic regression Advisor ... 45

List of Figures

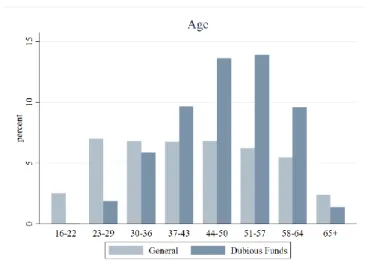

Figure 1. Distribution of age groups. ... 25Figure 2. Distribution of income groups. ... 25

Figure 3. Distinction between the North and the rest of Sweden. ... 40

Acknowledgments

First, I would like to thank my tutor Paul Nystedt for providing me with guidance and inspiration throughout the process of writing this thesis. Besides, I would like to express my gratitude to Johannes Hagen who provided me with the data to enable me to study this subject. Second, I want to thank Fredrik Hansen and Toni Duras for offering me useful insights and comments. Lastly, I would like to acknowledge my appreciation for my seminar group who provided me with valuable feedback.

1

Introduction

1.1

Background

In the late 1990s, Sweden made a major reform of its public pension system. The resulting pension reform has thereafter gained much attention internationally. Much pension-related research has used the Swedish experience to draw lessons from when implementing reforms in other countries. The reform is sometimes referred to as “the great compromise” as the reform was established and accepted by both left- and right-wings parties. The main implications of the reform were that the pension system:

• went from a Pay-As-You-Go defined-benefits scheme to a Notional Defined-Contribution scheme (NDC) financed on a pay-as-you-go basis, involving an automatic balancing mechanism,

• involves a privatized funded individual savings account (the premium pension) that allows the participants to diversify their pension portfolio by investing part of the contributions in capital markets,

• has a new guarantee pension that is tied to inflation.

The Swedish system has some typical design features which differ from the design of other countries’ pension plans. First, the Swedish system is public and mandatory. All individuals must participate in the partially privately managed accounts in the Premium Pension Scheme (PPS) with 2.5 percent of their income and contribute with 16 percent of their income to the notional defined contribution plan (Sundén, 2006). Second, the Premium Pension Scheme is centralized and managed by the Swedish Pensions Agency. However, they do not take responsibility for the funds entering the system or over how the participants choose to invest their money. Any fund meeting the basic requirements for EU fund management is allowed to enter the system. The funds can set their fees and are free to advertise to attract money (Cronqvist & Thaler, 2004).

The feature to allow free entry into the premium pension leads to a considerably higher amount of investment options to choose from compared to the most defined contribution systems. Swedish pension savers can choose up to five funds from a fund pool of over 800 funds in 2018 (källa). This can be compared to 401(k) plans where the average plan in 2012 offered 25 investment options for the participants (Engström & Westerberg, 2003). From a neo-classical perspective, the maximizing choice structure and allowance of free entrance to the pool market enable the potential to gain higher returns than the guarantee from the government. The main purpose of the PPS, according to the Swedish

higher return for the savers. The idea of an open fund platform is to facilitate individuals to adapt their portfolio to their preferences of risk and return.

However, the positive effects of the premium pension feature depend on the individual’s ability to make well-informed and neo-classically rational motivated investment decisions. There is a large body of research on investors’ behavior related to retirement planning to explain and examine the behavior of certain investors. Empirical research has suggested that some individuals, especially those with low financial literacy, are struggling to make informed decisions about their retirement savings (See for example Lusardi & Mitchell, 2011; Almenberg & Säve-Söderbergh, 2011). Swedish experience has shown that individuals are subject to several behavioral biases, are poorly informed, and lack motivation regarding their retirement savings (Sundén, 2006).

As more people are taken into the responsibility to act as their money managers after the pension reform, an increasing number of them have been exposed to fund advertising when they decided on investments in their retirement savings accounts. Due to the high number of options available in the pension system, the role of advertisement has become increasingly significant (Cronqvist, 2006). According to a report from the Swedish government (2019), many pension savers neither could or wanted to choose between the high number of options. Especially in 2010 and forwards, a market for consultancy firms in Sweden emerged to manage pension savers’ premium pension accounts for annual fees. These fees are in addition to the account and fund management fees that the Swedish pensions agency charges to the participants.

In 2016 and 2017, it was specially recognized by the Swedish Pensions Agency that several actors engaged in devious and sometimes even criminal behavior in their fund platform. The Swedish Pensions Agency first reacted to the activities engaged by the fund advisers in the Premium Pension Scheme by forbidding mass fund switches in 2011 (Friskman, 2011). However, this was not sufficient to stop some companies. In 2016, it was appreciated that 440 000 pension savers, about one-sixth of the active investors in the premium pension, were registered with consultancy firms to manage their premium pension rights (Regeringskansliet, 2019). Pension managers have, for instance, been criticized for reporting higher returns than actual, engaging in false advertisements and aggressive selling through phone calls and canvas sales (Pensionsmyndigheten, 2017a). A survey from the Swedish Pensions Agency suggests that the regular way for the PPS advisers to communicate with potential customers is through phone calls (Nord, 2013). The Swedish social insurance inspectorate published in a report that the consultancy services are frequently used by people with low levels of education and income

(Inspektionen för Socialförsäkringen, 2012). On the contrary, a survey made by the Swedish Pensions Agency suggests that those with higher education used these services more compared to those with lower education. The survey further implies that people have been frequently contacted based on their age and location. People in the age group of 30-49, people living in smaller places, and people living in the North of Sweden were the most frequently selected (Nord, 2013).

In recent years, discussions about a new reform of the Premium Pension Scheme have started to take place to tackle some of these issues that the system has been faced with. In the proposal from the Swedish government (2019), it is stated that the current open fund platform should be replaced with a procurement fund platform regulated and supervised by a new agency. The report notes that behavioral economic theories will be considered more this time than it was when the reform was implemented in 1998 when deciding on the number of funds that will be allowed to enter the fund platform.

The misuse of the premium pension’s fund platform which led to people losing their pension rights and receiving a lower pension may seem remarkable. Especially, as the premium pension is part of the social security system as a mandatory public pension. A sustainable pension system is built on the trust of people that the system should work properly. This trust is jeopardized if individuals experience irregularities in regards to how their money is managed. Not only the trust for separate pension managers, but also for the whole pension system itself. In the long term, this could also affect trust in the political system.

1.2

Problem Statement

It is a global problem that buyers of financial products rarely are knowledgeable about the financial product and that high fees and extensive marketing can make transfers from cheap and good products to worse and more expensive ones. The Premium Pension structure postulates active and conscious investors, which are capable of making rational investment decisions. However, the construction of the Premium Pension Scheme makes the circumstances of the investment decisions difficult for several individuals, leading to irrational choices that act to the disadvantage of the investors. Some actors try to take advantage of these shortcomings, which leads to even worse investment decisions. There were surveys conducted on which individuals that are prone to use PPS consultants and who have been subject to aggressive selling through phone calls. However, there is little research on which individuals that are a target for fraudulent behavior and how the fraud-related behavior is committed.

1.3

Purpose

This paper sheds light on the Swedish pension system, its current structure, and how deceptive funds in the Swedish pension system attract their customers. By analyzing a unique dataset of all individuals that have invested in six particular deceptive funds, the purpose is to conclude which individuals choose and are targeted by dubious funds in the Swedish pension system. The study is essential to understand why and what group of individuals are prone to staying invested in those funds despite them providing a low return. This low return is intensified by high fees and a contemporaneous risk profile can escalate to a total default of their savings. This research will aimfully contribute to the ongoing political discussions about new pension reforms in Sweden and the research conducted on financial fraudulent behavior.

1.4

Delimitations

The study is limited to data on six funds that have been subject to criticism and eventually have been removed from the pool of funds to choose from. Furthermore, it is limited to the following individual characteristics: age, gender, marital status, income in earnings pension, type of municipality, and geographic location. The methods that different funds have used to attract money is not represented in the data. Since the funds have used aggressive sales methods to attract their customers, some more than others, this paper will assume that the individuals have both chosen and been targeted to end up in the funds.

1.5

Structure

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. The following chapter provides further information about the funds that are selected for the analysis. Chapter 3 reviews previous research and theoretical aspects related to the analysis. It begins with an overview of the Swedish pension system and its development over the past decades. The next section briefly explains behavioral economic theories and their view of rationality to understand individuals’ behavior in retirement planning and how it deviates from the traditional view of rationality. To provide an additional understanding, the heuristics and biases individuals refer to when making decisions that are related to their well-being in retirement, as well as the influence of advertisement, are being examined. The final section examines how financial literacy is related to investor behavior and engagement in retirement planning. Chapter 4 takes into consideration theoretical aspects and previous evidence that lays the foundation for the development of the hypothesis. Chapter 5 provides a more detailed description of the data and methods that are being used in this paper. Chapter 6 presents the analysis of empirical findings on the relationship between the individuals’ characteristics and the choices of funds. Chapter 7 draws the conclusions. Chapter 8 involves recommendations, limitations, and suggestions for further studies.

2

Background Information on the Funds

Some funds in the pension system have received more complaints from the Swedish pension savers than others. Among them who are frequently mentioned are Allra, Falcon Funds, Solidar, GFG, Fondeum, and Advisor. The complaints revolve around aggressive selling, receiving fond papers, deceptive marketing, and fund switches through an individual’s mobile banking identification (Pensionsmyndigheten, 2017a). Eventually, they have been banned from selling funds to the public Premium Pension Scheme. In a report from the Swedish Pensions Agency in 2016, Advisor is on top of the list of complaints from savers in the agency’s customer service. On the same list, Falcon is in the third place, while Allra is on the fifth and Solidar in the 9th place. The fund selling firm “Lundstedt Fond och Finans” which guided people to invest in for GFG and Fondeum is in fourth place. (Pensionsmyndigheten, 2017a). This chapter starts with a description of Allra, followed by Falcon Funds, Solidar, GFG, Fondeum, and Advisor.

2.1

Allra

Allra, a Swedish finance company founded in 2008 under the name “Svensk Fondservice”, offers financial services within pensions, loans, and savings. In 2013, Allra received criticism from the Swedish Consumer Agency for aggressive sales methods and for sending fake invoices to customers (Jansson & Ohlin, 2017). The company thereafter changed its name to Allra. At the beginning of 2017, Allra was one of the biggest actors within the PPS, managing 19 billion SEK for about 130 000 pension savers (Jansson & Ohlin, 2017) out of 2.7 million active investors (Pensionsmyndigheten, 2017a). Despite that, the fees of Allra’s funds were multiple higher than the default Swedish fund (AP7) and yielded low returns. Their funds attracted customers by offering “safe” funds for the careful investor and their board consisted of highly reputational members, including the former minister of the Social Democrats Thomas Bodström and the former CEO of the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise Ebba Lindsö (Jansson & Ohlin, 2017).

In 2017, it was discovered that Allra had a secret company in Dubai through which they used to transfer investments in “warrants”. The owners of Allra had conflicts of interest with several investment companies, where they had intentionally overpaid for financial services. In total, their funds had paid 1.1 billion SEK in premiums of the warrants to different investment companies (Pensionsmyndigheten, 2018a). In February 2017, Allra was stopped for purchases by the Swedish Pensions Agency. In March, Allra was reported to the police, and the money that was still left was transferred to the default Swedish fund (Pensionsmyndigheten, 2020).

2.2

Falcon Funds

Falcon Funds Sicav p.l.c (“Falcon Funds”) was a Malta-based asset management company which offered three types of funds to Swedish pension savers. The three funds from Falcon funds were allowed into the platform in 2014. The mixed funds yielded a significantly lower return than the average mixed fund (Pensionsmyndigheten, 2020). The sub-funds were managed by Anthony Farrel’s firm Temple Asset Management. It was discovered that Anthony Farrel with his firm Temple Asset Management was using the pension savers’ money to invest in financial instruments benefiting the Swedish businessman Emil Amir Ingmansson, who is one of the accused persons behind the funds

(Cervantes, 2015).

Falcon Funds intensively used insurance intermediaries and call center companies. According to Lapidus (2017), 22 000 savers are suspected to have lost money from the funds, where many of them got their money transferred to the funds through their mobile banking identification. The aggressive sellers had been able to get their login credentials for the premium pension through telephone. The funds were estimated to have a worth of 2.4 SEK billion (Lapidus, 2017).The majority of the savers had of all of their premium pension savings in these funds. The Swedish Pensions Agency reported the funds in 2016 and at the end of 2016, the money that was left was being transferred to the “AP 7 Såfa” fund. In 2018, 750 million SEK were estimated to be missing from the funds (Pensionsmyndigheten, 2018a).

2.3

Solidar

Solidar, a former asset management company, managed capital of approximately 20 billion SEK in 20 investment funds. In March 2018, around 75 percent of these funds were registered in the PPS with approximately 67 000 Swedish pensions savers. Solidar made a profit through companies on Malta, as part of “DS Platforms”. During a period, the head owners of Allra were also a part of DS Platforms (Finansinpektionen, 2018). Solidar had conflicts of interest as the board of Solidar had economic interests in DS Platforms. On this ground, the Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority fined Solidar with 10 million SEK. In December 2017 the funds were put on buying hold by the Swedish Pensions Agency and were eventually removed from the platform in April 2018 (Pensionsmyndigheten, 2018c).

2.4

GFG

In February 2016, the Swedish Pensions Agency informs pension savers in GFG Global Medium Risk Fund (“GFG”) that parallel logins through their personal mobile banking

identification have been made on their premium pension accounts. According to the Pensions Agency (2020), representatives from “Lundstedt Fond och Finans”, a fund selling firm, had contacted pension savers through phone and thereafter, through the person’s banking identification, transferred their capital in the premium pension to the GFG Global Medium Risk Fund.

The Global Medium Risk Fund with a total worth of 1.1 billion SEK had in 2015 decreased by 13 percent. The Swedish pensions agency’s inspection of the fund showed that their largest holding was the same as the largest holding in Falcon Funds (Pensionsmyndigheten, 2020). In total, the fund had decreased with more than 30 percent as the Swedish Pensions Agency announces that the fund is stopped for purchases in November 2016 (Pensionsmyndigheten, 2018a). The fund was removed from the fund platform in December. In March 2017, the Swedish Pensions Agency announced that approximately 325 million SEK was still not repaid. The money left in the fund was being moved to the “AP7 Såfa” fund. In 2018, 90 percent of the fund’s money was supposed to be repaid to the savers (Pensionsmyndigheten, 2018b).

2.5

Fondeum

At the same time the GFG Global Medium Mixed fund is being stopped, the Swedish Pensions Agency also stopped the Fondeum Mixed Fund (“Fondeum”) from being purchased. Fondeum was a Malta-based fund management company (Pensionsmyndigheten, 2020). The owners of the fund were allegedly also involved in “Lundstedt Fond och Finans” which has previously been reported to the police by the Pensions Agency in connection to Falcon Funds. The Swedish Pensions Agency stated a steep increase was due to the aggressive acquisition of new customers. In December 2016, the Fondeum Mixed Fund, with an estimated worth of 177 million SEK was removed from the premium pension plan (Pensionsmyndigheten, 2016b).

2.6

Advisor

Advisor was excluded from the Premium pension’s fund pool in November 2017 due to accusations regarding their marketing and sales methods. Their only fund that was registered in the PPS managed the money of about 43 000 savers with a total worth of 4.5 billion SEK (Pensionsmyndigheten, 2017b). For example, they were committed by the Customer Protection Agency for having a curing time longer than 12 months (Konsumentverket, 2018). Their fund had a relatively high fee on their fund, together with additional management fees, accompanied by a low return.

3

Literature Review

3.1

The Swedish Pension Reform

In the 1990s, Sweden underwent a major reform with its public pension system which made individuals in the new system more responsible for their pension accounts than before. The intention behind the reform was for the system to be financially and politically sustainable for an indefinite period, regardless of an aging population.

3.1.1 Development of the Reform

Before the big reform, the public pension system was comprised of three tiers. The first tier was a flat-rate basic pension carried out on a Pay-As-You-Go basis referred to as “folkpensionen”. The second part was introduced in 1960 as a partially pre-funded earnings-related benefit (ATP) which was added on top of the flat-rate pension. The final and third tier consisted of a means-tested pension supplement that was paid out to those who gained very low earnings-related benefits (Weaver & Willén, 2014). This supplement together with the other two other tiers provided a quite generous replacement rate for all Swedish seniors compared to the average rate of the OECD countries (Sundén, 2006)

Due to an aging population and slower economic growth, funding the public pension system through payroll taxes became more difficult. Therefore, discussions about a pension reform started to take place in the 1980s. Due The design features of the old system were causing a poor linkage between earnings and benefits as well as distortions in the labor market. To tackle these difficulties, restrictions on early retirement and fundamental changes to stabilize financing and benefits for the long term were proposed by the Social-Democratic government in the mid-1980s (Sundén, 2006).

The fundamental reforms accelerated in 1991 after the switch to a four-party liberal/conservative government. They recognized a need for greater reforms of the pension system than the one previously proposed. The center-right parties thereby developed another reform package that could be supported by both the right and left parties. The final result was a compromise between Pay-As-You-Go and defined contribution components, including a small part of funded individual accounts. An agreement between the parties was reached in 1994 and the reform was fully implemented in 1998 (Weaver & Willén, 2014).

In the new pension system, the earnings-related pension consists of two parts: The Notional Defined Contributions plan, “Inkomstpensionen”, and the Premium Pension

Scheme, “Premiepensionen”. Employers and employees pay 16 percent of their earnings to the NDC plan and 2.5 percent of their earnings to the Premium Pension plan. The old supplement is replaced with a new means-tested pension supplement to provide a minimum guarantee income for the ones with no or low pension income from the earnings-related pension which is funded by general tax revenues (Palme et al., 2007) 3.1.2 The Premium Pension

An important part of the reform was the contributions to the Premium Pension plan which are transferred annually to an individual account. According to Sundén (2006), the motivation behind the individual accounts was to make individuals more responsible for their pension savings by allowing them to make use of higher returns that can be gained in capital markets and to customize a part of the individual’s savings to its preference of risk. The new system allows participants to invest in a wide range of domestic and international funds.

When the first investment round in the Premium Pension plans took place in 2000 the participants could choose up to five funds amongst 460 funds. In 2014, the number of funds to choose from had grown to nearly 800 (Weaver & Willén, 2014). Any fund manager who is EU-licensed to make business in Sweden is endorsed to take part in the system. The accounts are centrally managed by the government authority “Pensionsmyndigheten”. However, when they implemented the new system they established a separate government unit, the Premium Pension Agency, to minister the plans and act as a clearinghouse (Sundén, 2006). An advantage of this management is that this authority can negotiate about the funds’ management fees as they require that the fund managers give a discount directed to the pension savers. Individuals who choose to not make an active decision will get the government’s managed mutual fund, “AP7 Såfa” which has a generally low fee (Sundén, 2006).

3.1.3 Engagement in the Individual Accounts

The initial round of the mutual funds' selection was made in 2000. In this round, 67 percent of the 4.4 million entitled investors made an active choice (Engström & Westerberg, 2003). According to Engström and Westerberg (2003), it was more likely that individuals with financial wealth, higher education, higher income, employed in the financial sector, or have private pension savings to make an active decision compared to other individuals. Younger individuals were more likely than older individuals to make an active choice while people born outside the Nordic region were 60 percent less likely to make an active choice than those from the Nordic region.

However, after the initial round, the number of new entrants making an active decision decreased drastically. Of those who came into the system in the subsequent five years, about one-fifth made an active choice. Thaler and Sunstein (2009) suggest, contrary to the previous study conducted by Engström and Westerberg (2003), that this can be explained by the fact that the new entrants to the premium pension system in the latter years were young. They have less money to invest, longer time to retirement, and are faced with too many options.

Another explanation proposed is that in the initial round of investment, the pension agency prepared the individuals by collecting and providing information on all the available funds in a catalog distributed to all individuals. Both fund managers and the former Premium Pension Agency launched substantial campaigns to attract attention to the individual accounts. In later rounds, the pension fund choice got less attention in media. Fund managers did not mount any big campaigns (Engström & Westerberg, 2003). Besides, the default fund AP7 performed better than the average of the chosen funds in the first years (at a lower fee) which might have caused individuals to be more attracted to the passive choice (DeLiema et al., 2018).

Among the mutual funds that are offered in the fund marketplace, Sundén (2006) argues that only a few of them were constructed with retirement savings in mind. Savers are expected to build their diversified portfolio suitable for their retirement savings throughout their working life. Weaver and Willén (2014) note that despite the economic importance, it seemed to be difficult to keep individuals engaged in their retirement planning. In 2011, about half of the ones who made an active choice and around one-fifth of the ones who were in the default fund upon entering the premium pension system made any changes since then.

3.2

Behavioral Economic Theory and Rationality

One of the intentions of the reform was to improve the wealth for individuals in their retirement by maximizing the number of funds to choose from and thereby enable all Swedish pension savers to captivate on the returns from capital markets. From the preceding section, it is exhibited that the Premium Pension Scheme seemed to be too complex for individuals to make well-informed decisions and it seemed to be difficult to keep people engaged in their retirement portfolios. The following sections of this chapter intend to explain why. To develop our understanding, it is examined how behavioral economic theories deviate from the traditional economic theories in their views of rationality.

Traditional finance theory assumes that individuals are rational: they can identify and use relevant information as well as they can make optimal decisions. Within the field of behavioral economics, Benartzi and Thaler (2002) define rationality as that individuals update their beliefs when they receive new information and can make decisions on their own that are considered acceptable. Dellavigna (2009) further outlines that under standard economic theory, individuals are assumed to only be concerned about their pay-offs, have time-consistent preferences, and are objective regarding the framing of the decision. Although, several laboratory experiments and empirical evidence have challenged these beliefs.

For instance, Thaler (1981) violated the assumption that individuals are time-consistent. Kahneman and Tversky (1979) proposed that individuals’ risk attitudes were dependent on the framing of the option. DellaVigna (2009) suggests that behavioral economics deviates from the standard theory of economics in three settings. First, evidence has shown that individuals have non-standard preferences. For instance, evidence from retirement savings challenges the assumption of time-consistent preferences. Second, they hold incorrect beliefs. Third, they make systematic biases in their decision-making process. Here, DellaVigna (2009) discusses that individuals are using heuristics, forgiven utility, and beliefs, instead of solving complex problems. DellaVigna (2009) suggests that individuals are subject to numerous behavioral biases such as the framing of the problem, being inattentive of certain information, or social pressure.

3.2.1 Bounded Rationality and the Role of Institutions

Within behavioral economics, Kahneman and Tversky (1979) conclude that there are errors and biases in the decision-making process imposed by psychological constraints. However, Simon (1978) shared a different view of rationality where individuals assume to make rational decisions as a consequence of psychological constraints and the decision-making environment. Herbert Simon developed the concept of bounded rationality to explain individuals’ choice behavior in the real world. This theory suggests that people are incapable of making rational decisions as described by the traditional economic theories and imply that it is enough for individuals to make satisficing decisions, as opposed to maximizing decisions. Rational behavior should be based on what individuals are capable of in the real world to help optimizing well-being.

Gigerenzer (2007) further developed Simon’s bounded rationality theory by showing how fast and frugal heuristics, often based on emotions and intuitions, result in successful and efficient decisions. These are often applied to financial markets or financial matters where complex decisions need to be made under uncertainty with imperfect and asymmetric

considers individuals as rational, they can still commit errors or mistakes, referred to as rational errors (Altman, 2012). From this point of view, informational and institutional parameters have a key role in generating such errors. Simon’s bounded rationality assigns institutions a key role in producing optimal (or satisficing) decisions. In other words, the choice environment within individuals engage in decision-making is a kind of ecological rationality.

3.3

Heuristics and Biases in Retirement Investment Decisions

A study conducted by Kogut and Dahan (2012) through a survey conducted on economists, showed that the participants lacked the motivation to engage in their retirement planning compared to their motivation to engage in other tasks. Further, they suggest that the lack of motivation is one of the reasons why people are subject to behavioral biases in their retirement planning. Barber et al. (2005) found, using data on U.S. mutual funds, that many personal investors have significant holdings in high expense mutual funds. Morley and Curtis (2010) mention search costs as one explanation to this phenomenon, which they argue may be higher for investors that lack financial knowledge, but also the motivation to pay attention to their funds and make sound investment decisions. Bailey et al. (2011) showed through panel data from US brokerage firms that participation in high fee funds is consistent with different behavioral biases. The following sub-sections examines the type of heuristics and biases that can help explain the decision-making process related to the engagement in the mandatory individual accounts.

3.3.1 Hyperbolic Discounting

Hyperbolic discounting is a cognitive bias said to influence the motivation of individuals to engage in retirement savings (Benartzi & Thaler, 2007). In standard finance theory, the discount factor between any two time periods is independent of when the utility is estimated. That is, the preferences about plans in the future are the same for different periods as the discount factor is assumed to be time-consistent (DellaVigna, 2009). Frederick et al. (2002) doubted this assumption and showed in their study that discounting is steeper in the present future than in the distant future. They define a person’s declining rate of time preferences as hyperbolic discounting. O’Donogue and Rabin (1999) proposed that if an individual prefers a reward that arrives sooner rather than later, and is at the same time not aware of this self-control problem, this can explain the default effect in retirement plans. According to their model, this person would postpone the activity of enrolling in the retirement savings plan to the day after and keep doing this infinitely.

3.3.2 Information Overload

According to Agnew and Szykman (2005), information overload is a behavioral bias that can cause individuals to find a “shortcut” and increase the likelihood that individuals procrastinate their decision. When people are subject to information overload, it can lead to anxiety or panic, leading to regretful decisions. In other words, individuals reduce their effort to make well-informed and thoughtful decisions. Agnew and Szykman (2005) argue that information overload is caused by having too many options as well as the similarity between the options. Sethi-Iyengar et al. (2004) found in their study that participation rates in 401(k) plans decreased for every ten funds that were added. Whereas the Swedish pension system has around 800 funds to choose from, the probability of being subject to information overload is allegedly high.

3.3.3 Limited Attention

Yet when information is readably available and an investor possesses the cognitive abilities to assess it, an individual may tend to simply not pay attention to it. One explanation to this is that when information is unpleasant to deal with, people intently avoid dealing with it since attention impose a welfare loss (Lowenstein et al., 2014). Traditional finance theory assumes that investors derive utility from their assets the time they consume them, e.g., retirement savings. However, it has been widely acknowledged within behavioral research that people can derive utility from information as well, no matter if the information is positive or negative (Brunnermeier & Parker, 2005; Golman et al., 2017). Brunnermeier & Parker (2005) develops a theoretical model in their study that shows that people can choose to hold optimistic beliefs for immediate well-being. This means that the individual may avoid information that interferes with its ability to maintain its optimistic expectations, despite the benefit of making better decisions. The phenomenon of avoiding risky situations by pretending they do not exist is sometimes referred to as the “ostrich effect” (Galai & Sade, 2006). Karlsson et al. (2009) define the ostrich effect as the tendency for investors to more often observe their portfolios during good performances than weak. They find empirical evidence of the ostrich effect when testing it on the Swedish pension system. Sicherman et al. (2015) found similar results in their study, namely that investors tend to pay more attention to their portfolios after a rise in the market than when the market has declined. The authors conclude from their empirical study that the effect is greater among men, older investors, and investors with more wealth.

3.3.4 Status Quo Bias

The avoidance of information that can cause an individual to lose confidence or doubt its ability may generate a bias for the status quo. Samuelson and Zeckhauser (1988) define this concept as the tendency for individuals to maintain their previous decisions regardless of the changes in their environment. This can make individuals stick to a sub-optimal option, even when it does not yield a higher material benefit. The status quo bias can help to explain why the Swedish pension savers stay with their first choice in the pension system, even though there are no transaction costs in switching funds. Sundén (2006) argues, from a theoretical perspective, that Swedish pension investors fail to create a well-diversified portfolio throughout the years as they are subject to inertia, which involves the disinterest to hassle with changing of funds.

3.3.5 Trust Heuristic

Even with the correct incentives, informational errors can lead to rational individuals making decisions they would otherwise not engage in. Altman (2012) argues from a purely theoretical perspective that the use of trust, even in a world of misleading information, is common among decision-makers. Several studies as synthesized by Altman (2012) suggest that when legal guarantees are present, the trust heuristic is a form of bounded rationality or smart behavior that makes the decision process more efficient and effective. The trust heuristic can lead to people collectively acting in group behavior and to follow leaders that the individual trust when being unsure about what product or financial asset to buy is. In a world of complex and often misleading information, investors often assume that portfolio managers are relatively better informed than themselves which may lead to inferior economic results compared to the conventional search and information gathering.

Altman (2012) argues that the effectiveness of the trust heuristic is a function of the extent to which proxies for trustworthiness can be trusted, and that reliable and accurate information is available for the decision-makers. However, in a world of false and deceptive information, the trust heuristic that is usually seen as an effective tool, results in a market failure. Altman refers to a Ponzi scheme as an expression for the act of pretending to provide legitimate, but high, returns on investment whereas the returns come from payouts from the capital that is provided by new and existing clients. People invest in such schemes as they trust in their legitimacy, and should more specifically trust in the legitimacy and integrity of those managing the fund. In combination with economic incentives and perhaps a perception that the government guarantees their investments, investors might be more inclined to engage in risky behavior.

3.4

Framing and Advertisement

As the mutual funds in the Premium Pension Scheme are allowed to advertise, it is also important in this study to consider how advertisements influence the investors’ choices. Kahneman (1984) observed that the way information is presented has a strong influence on people’s judgment. Benartzi and Thaler (2002) found consistent results in their experimental study involving retirement savings. These findings may impose implications for retirement planning especially as the funds are allowed to advertise to attract money. While investors may find it information-costly to search for funds that they cherish, for instance, the vast number of mutual funds offered in the Swedish retirement plan can cause individuals to feel overloaded and look for ways to limit their information search. Barber et al. (2005) find that mutual fund investors are influenced by salient, attention-grabbing information. As a consequence, the funds with extensive and visible marketing are more likely to catch the buying attention of an investor. This section aims to describe how investors in the pension system may be influenced by marketing and other forms of financial persuasion.

3.4.1 The Role of Advertisement

The study conducted by Henry Cronqvist (2006) on the Swedish pension system indicates that only a small fraction of the ads could be seen as directly informative about relevant information for rational investors, such as the funds’ fees and expense ratios. Through a content analysis, Cronqvist found that the mutual fund advertising steered persons into portfolios with higher risk and lower returns; due to them having higher fees, higher exposure to equities, more active management, and a greater home bias. He found that although a fund did not contain any information the advertisement had a strong effect on individuals’ portfolio choices.

3.4.2 Social Pressure and Persuasion

Within the area of behavioral economics, Akerlof (1991) and DellaVigna (2009) identify the pressure to conform and the power of persuasion as two reasons for the excess impact of the beliefs of others. Haslem (2009) mentions that conflicts of interest arise for fund advisers in recommending a fund to their clients. Sah et al. (2012) discuss social pressure in the context of following the advice of a fund adviser. Due to the individual’s psychological impulse for conflict avoidance, they argue based on laboratory experiments and field studies that individuals may follow the advice even if they distrust the adviser. According to DellaVigna (2009), the neo-classical model assumes that individuals consider the incentives of the information provider, and neglecting these incentives can

Baker and Ricciardi (2014) define this as persuasion. According to a survey conducted by Böhnke et al. (2019), on the Premium Pension Scheme, 55 percent out of a sample of 2,646 individuals said they had been influenced by a pension adviser in selecting mutual funds. Individuals that claimed that they had been influenced by others in their choices of mutual funds considered themselves as less financially literate, had a higher probability for information overload and were more often female.

3.5

Financial Literacy and Engagement in Retirement Planning

Several studies suggest that the individual’s level of financial literacy is related to his or her engagement in retirement planning. Based on a comprehensive data collection gathered from eight different countries, Lusardi and Mitchel (2011) argue that there is a causal relationship between financial literacy and retirement planning. Based on their findings, people are more likely to plan for their retirement if they understand risk diversification, the concept of inflation, and can make simple calculations. Almenberg and Säve-Söderbergh (2011) use the same method in their study to measure individuals’ level of financial literacy. Based on a telephone survey collected on 1300 Swedish adults, they discover that there is a positive relationship between financial literacy and engagement in planning for retirement. In a more recent study, Clark et al. (2015) conclude a positive relationship between individuals’ financial literacy and their tendency to participate in a 401(k) plan as well as their profitability of the respective investments after using administrative data on investments.

Related literature has suggested that more financially literate individuals are more likely to diversify portfolio risk, choose funds that have lower fees, make fewer investment mistakes, yield higher returns and be more aware of fund management fees (Palme et al., 2007; Lusardi & Mitchel, 2011; Hastings & Mitchel, 2020). Engström and Westerberg (2003) point out after examining a sample of 150 000 Swedish pension savers that people with high income, women, married individuals and younger people are more likely to make an active investment choice in the Swedish pension system.

3.5.1 Financial Literacy and Sensitivity to Information Overload

Agnew and Szykman (2005) made an experiment in their study on the relationship between information overload and the level of financial literacy. They found that a higher level of financial literacy can help reduce information overload. When a person lacks the skills and capabilities to evaluate the different options the whole process can be even more daunting. This triggers it to be even more likely for investors to either avoid the choice completely or let a financial advisor choose for them.

3.5.2 Gaps in Financial Literacy

Numerous studies indicate that there are gaps in individuals’ financial literacy. Almenberg and Säve-Söderbergh (2011) report that financial literacy is generally lower among the young and old people, those who are single, women, and those with low educational attainment or low income. Single women performed the worst on the financial literacy tests while men in joint relationships performed the best. Lusardi and Mitchell (2011) drew similar conclusions in their findings; women tend to be less financially literate than men, middle-aged people tend to be more financially literate than the young and the old, and educated people have more financial knowledge than those who are less educated. Agnew et al. (2008) found that women are more risk-averse and less financially literate than men. Though, evidence from the United States’ Defined Contribution plan has shown that women tend to make better choices than men and that people with higher income make significantly better choices and are much more likely to participate in contribution plans (Agnew, 2006).

According to the survey conducted on the Swedish pension savers by Böhnke et al. (2019), those who considered themselves as well-informed were often younger, men, higher educated, and believed they had a sufficient level of knowledge. Individuals who more often have chosen mutual funds had higher incomes, considered themselves to have good financial literacy, had higher risk preferences, felt their pension would keep them financially safe, were older, and stated they appreciated the freedom of choice.

Synthesized by Stolper and Walter (2017), financial literacy decreased by the age of individuals. Whereas, previous research related to financial scams and fraud suggests that financially unsophisticated individuals in their older ages are an attractive target for financial scams due to their increased holdings of wealth (Deliema et al., 2018). However, as Deliema et al. (2018) point out, one challenge in research on financial fraud has been to find consistent results regarding how age, socioeconomic status, financial literacy, and other factors are related to fraud vulnerability.

4

Hypothesis Development

The literature review implies that people are both subject to the framing of the option and by advertisement when making their investment decisions. People tend to discount outcomes that will occur in a distant future, making them unmotivated to engage in their retirement planning. They tend to not pay attention to their investments to avoid bad news and hold optimistic beliefs, strengthening the likelihood to stick to a sub-optimal investment. They can make investment decisions based on trust, both in the pension system as well as on the information they are provided with is true, if the information search is costly. Moreover, people are likely to be influenced by others when making their investment decisions and might be persuaded by advisers and sellers. Especially, when they feel overwhelmed with information. This, in turn, opens up for mis-selling in the market.

It is further reviewed in the literature that financially literate people are more engaged in their retirement planning, less likely to be subject to information overload, more aware of fund management fees, and less likely to be influenced by others. People with low financial literacy might, therefore, have a higher propensity to use financial intermediaries as the ones discussed earlier in this paper since they might be more likely to subject of information overload, have higher costs of information search, be more influenced by others and lack the confidence or knowledge to select for themselves. Based on the background section and the literature review, some variables are more interesting to look at than others.

Gender: Previous research has suggested that there are differences between men and women in terms of their investment behavior. Early studies on the Swedish pension savers have shown that women have a greater tendency than men to make an active investment decision (Engström & Westerberg, 2003). Other studies have demonstrated that women on average possess lower financial literacy than men (Almenberg & Säve-Söderbergh, 2011), and are more often influenced by others when making their investment decisions (Böhnke et al., 2019).

Hypothesis 1. Women have a higher probability to be in one of the dubious funds. Marital Status: Engström and Westerberg (2003) found in their results for example that married individuals were more likely to make an active investment decision in the Premium Pension Scheme. However, Almenberg and Säve-Söderbergh (2011) found that the lowest level of financial literacy was found among single persons while people in joint relationships had a higher level of financial literacy. It could be assumed that married people live in joint relationships, while unmarried and divorced people are more often

single. Seeing this way, married people are less likely to be subject to information overload and influenced by others when making their investment decisions. While unmarried and divorced people, based on this assumption, are more likely to be influenced by others.

Hypothesis 2. Unmarried and divorced people have a higher probability to be in one of the dubious funds.

City Size (Municipality) and Geographic Location: Another variable that is not much researched but can be interesting to look at is the type of municipality and geographic location of the individual. According to the survey made by the Swedish Pensions Agency (2013) people from the North of Sweden and people living in smaller places or rural areas are the ones who are mostly contacted by and use PPS advisers.

Hypothesis 3. Individuals living in rural areas, as well as people living in the North of Sweden, have a higher probability to be in one of the dubious funds.

Age: Previous research has shown that young and old people possess lower financial literacy and are less experienced with financial markets (Almenberg & Säve-Söderbergh, 2011; Lusardi & Mitchell, 2011). However, as demonstrated by Frederick et al. (2002), people tend to discount outcomes that will occur in a distant future. Thus, it is sensible to assume that younger individuals are less concerned about pension savings than older individuals. Moreover, observed in studies on the Swedish pension system (Hedesström et al., 2004; Hedesstrom et al., 2007), the likelihood of being in the default fund is higher depending on whether a person has a small amount to invest. Since young people can be assumed to be fresh entrants into the job market, they implicitly have a smaller amount to invest in the Premium Pension Scheme.

Hypothesis 4. Older individuals have a higher probability to be in one of the dubious funds.

Income: Many studies suggest that financial literacy is positively correlated with income (Almenberg & Säve-södeberg, 2011; Lusardi & Mitchel, 2011; Stolper & Walter, 2017). As people that are less financial literate have a greater tendency for information overload and to be influenced by others when making their investment decision (Agnew et al., 2006; Böhnke et al., 2019), it is assumed that:

Hypothesis 5. Individuals with a lower income are more likely to be in one of the dubious funds.

5

Methodology

A quantitative method is used in this study as the research question of this paper aims to identify patterns in a set of data. This chapter starts with a description of the sets of data used in this paper, followed by the empirical method applied to analyze the data.

5.1

Description of Data

In this paper, I use data that consists of individuals who have been in one of the six selected funds (379 639 individuals) and data from a 5 percent random sample of other savers (356 704 individuals). The data is obtained from the Swedish Pensions Authority1. The dataset includes when the person entered one of the fraud funds and when he left the fraud fund. I have prepared and analyzed using STATA. All individuals are treated anonymously in the dataset and treated with strong integrity to protect the data on personal characteristics that are dealt with in this study. All individual characteristics are obtained in 2017.

Formal definitions of the variables:

(i) Income: Measured as the individual’s total contributions of their earnings (Income pension and Premium pension).

(ii) Age: The age of the individuals ranges from 16 to 78 years old.

(iii) Gender: Men and women are differentiated in the dataset by creating a dummy variable that is equal to 1 for women and 0 for men.

(iv) Marital status: A distinction is made between whether an individual is married, divorced, or unmarried.

(v) Municipality: The municipalities are sorted by using SCB’s divisions of municipalities into different regional areas. I distinguish between large-city areas, bigger cities, smaller cities, and smaller towns/rural areas. Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Malmö are considered as large city areas which together consist of 47 municipalities. Bigger cities consist of 19 municipalities. Smaller cities include 29 municipalities. Municipalities that do not belong to any of these categories are treated as rural areas.

(vi) Geographic location: The municipalities are also divided by their geographical location; the separation is made between living in the North of Sweden and the rest of Sweden. This distinction can be seen on a map over Sweden in Appendix A.

Two of these variables contain missing variables: municipality (1.53%) and marital status (1.11%). There is a generally low correlation between the variables which suggests that multicollinearity will not have a significant effect when estimating the coefficients. The greatest correlations are observed between age and marital status (0.2342) and between smaller cities and the North of Sweden (0.2365). The categorical variables are correlated by using Cramer’s V correlation.

Table 1. Distribution of individuals’ characteristics in 2017 in percentages

Age Category 16–22 23–29 30–36 37–43 44–50 51–57 58–64 65+ Total Women 2.69 8.42 12.19 16.67 20.89 20.54 15.23 3.36 100.00 51.42 46.13 46.81 49.29 49.66 49.61 49.16 43.23 48.64 Men 2.40 9.31 13.12 16.24 20.06 19.77 14.92 4.18 100.00 48.58 53.87 53.19 50.71 50.34 50.39 50.84 56.77 51.36 Married 0.12 2.85 10.27 17.67 22.53 22.46 18.71 5.39 100.00 2.05 14.48 36.58 48.45 49.66 50.29 55.98 64.34 45.11 Divorced 0.03 1.16 5.30 12.49 22.86 29.36 23.20 5.59 100.00 0.18 1.92 6.13 11.12 16.35 21.34 22.53 21.65 14.64 Unmarried 6.30 18.56 17.86 16.34 17.36 14.28 8.09 1.21 100.00 97.00 81.82 55.19 38.89 33.21 27.76 21.02 12.54 39.15 Income, SEK 0–25 000 8.76 14.34 12.28 12.57 12.86 12.50 12.88 13.81 100 50.25 23.55 14.13 11.14 9.16 9.05 12.46 53.24 14.58 25 000–50 000 3.98 12.12 12.76 13.84 16.48 18.7 18.24 3.87 100 38.14 33.24 24.53 20.48 19.61 22.61 29.46 24.92 24.35 50 000–75 000 0.68 7.92 13.81 17.44 21.87 21.81 15.14 1.33 100 10.75 36.02 43.99 42.78 43.13 43.69 40.53 14.22 40.36 75 000 - 0.10 3.08 10.61 20.32 27.75 23.98 12.77 1.39 100 0.85 7.19 17.35 25.6 28.09 24.66 17.55 7.61 20.72 Large City Areas 2.77 10.38 14.81 17.78 19.71 18.43 12.61 3.49 100.00 33.58 36.01 36.00 33.28 29.66 28.17 25.76 28.44 30.79 Bigger Cities 3.00 10.06 12.67 16.21 20.28 19.72 14.64 3.43 100.00 28.50 27.39 24.16 23.82 23.95 23.66 23.48 21.94 24.17 Smaller Cities 2.42 7.79 11.35 15.35 20.81 21.38 16.94 3.95 100.00 13.16 12.11 12.37 12.88 14.03 14.64 15.51 14.43 13.80 Rural Areas 2.03 7.00 11.17 15.82 21.19 21.62 16.94 4.24 100.00 25.30 24.97 27.92 30.46 32.79 33.98 35.58 35.49 31.67 North of Sweden 2.17 7.41 10.82 15.02 20.75 21.80 17.97 4.05 100.00 14.21 13.87 14.19 15.16 16.84 17.98 19.80 17.81 16.61 Other 2.61 9.17 13.04 16.73 20.41 19.81 14.50 3.73 100.00 85.79 86.13 85.81 84.84 83.16 82.02 80.20 82.19 83.39 Total 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00 100.00

Table 1 shows the distribution of characteristics of the individuals in the total dataset (including both the participants in the dubious funds and the rest of the savers). The categories are sorted by age and include gender, marital status, income (measured as income in the earnings pension), geographic area, and age. As can be seen in the Table there are slightly more men than women in the dataset. About 45 percent are married while nearly 17 percent are divorced and 40 percent are unmarried. Around 30 percent of the population represented in the dataset are living in one of the three large-city areas and 32 percent are living in municipalities that are not considered as cities. Nearly 17 percent are living in the North of Sweden. Almost 21 percent contribute more than 75 000 SEK to their earnings pension. About 40 percent earn less than 50 000 SEK in their earnings pension, which is considered as low earnings in this study. A significant part of the younger age categories and the oldest age category belong to the lower-income groups. See Appendix A, Table 6, for how the contributions in the earnings pension translates into annual and monthly salaries.

5.2

Empirical Method

Both the linear probability model, probit models, and logit models are frequently used when the dependent variable is binary. In this study, the logit model is used and the linear probability model will be tested as a form of robustness check. Both of these models predict to which of two categories an individual is likely to belong, given the information covered in the predictors. More specifically, the relationship between people’s investment choices and people’s characteristics is explored in a multiple regression setting where the binary response variable is defined as

𝑦𝑖 = {1,0, if an individual been in one of the selected fundsif not

where yi can be regarded as a realization of a random variable Yi which takes on the value of 1 with probability 𝜋𝑖 and 0 with probability 𝜋𝑖− 1. The expected value of Yi is a probability noted as 𝐸[𝑌] = 𝑃(𝑌 = 1 ) = 𝜋𝑖.

5.2.1 Linear Probability Model

In the linear regression setting, the model that is used to describe the probability of being in one of the selected funds based on the individual’s characteristics is simply

𝜋𝑖 = 𝒙𝒊′𝜷, (1)

where xi is a vector of the individual characteristics and 𝛽 is a vector of estimated

squares and confidence intervals and hypothesis testing can be computed by robust standard errors. A main advantage of the linear probability model is that its coefficients are easier to interpret and it is quicker to estimate than the logit model. However, as the linear regression assumes the probability function to be linear, the right-hand side of the equation has no limits for the values it can take on. Whereas the left-hand side of the equation has to be between 0 and 1 (Hosmer et al., 2013).

5.2.2 Logistic Regression

The issue with the linear probability model can be solved by transforming the model into a logit model (Hosmer et al., 2013). A logit regression, or logistic regression, assumes a non-linear function between the probability and the observed variables. The probability 𝜋𝑖 can instead be defined as odds

𝑜𝑑𝑑𝑠𝑖 = 𝜋𝑖

1−𝜋𝑖, (2) where the odds can be defined as the ratio of the probability to its complement. Hosmer et al. (2013) specify the form of the logistic regression model as

𝜋𝑖 = 𝑒𝑥𝑝(𝒙𝒊′𝜷)

1+𝑒𝑥𝑝(𝒙𝒊′𝜷). (3) The following equation is derived by taking the logit of the probability 𝜋𝑖, or the log-odds, and assuming that the logit of the probability follows a linear function of the observed predictors

𝑙𝑜𝑔𝑖𝑡(𝜋𝑖) = log 𝜋𝑖 1−𝜋𝑖 = 𝒙𝒊

′𝜷, (4)

An important feature of this model is that the logit is linear in its parameters and may range between -∞ to +∞, while the probability 𝜋𝑖 always is between 0 and 1. Another important is that the logistic model assumes that the error term follows a binomial distribution, while the error terms in the linear probability model are always heteroscedastic (Hosmer et al., 2013).

As the odds ratios describe the probability of belonging to a certain category based on the probability of belonging to another, an odds ratio equal to one means that it is an equal probability to belong to the categories.By calculating marginal effects from the logistic model, it is possible to compare it to the coefficients of the linear model. While odds ratios compare the two probabilities of belonging to one category to another, the marginal effects express the discrete level of change from one unit to another on the expected

6

Empirical Findings and Analysis

To begin with, the relationship between selecting one of the excluded funds and the individuals’ characteristics is examined through descriptive statistics. Next, the relationship between the choice of investment and individuals’ characteristics is evaluated in a multiple regression setting.

6.1

Descriptive Statistics

Table 2. Comparison of the two population groups in percentages (within column) Variables General Population Dubious Funds

Women 48.46 48.71

Men 51.54 51.29

Married 41.55 47.90

Mean Income* (SEK) 53 002.32 58 550.47

Divorced 11.37 17.21

Mean Income* (SEK) 47 570.23 54 844.61

Unmarried 44.57 34.89

Mean Income* (SEK) 44 163.33 55 345.87

Large City Areas 38.23 24.93

Bigger Cities 23.31 24.85

Smaller Cities 11.74 15.43

Rural areas 27.19 35.19

North of Sweden 12.50 19.84

Other 87.50 80.16

*In absolute terms

Table 2 shows a comparison of the distribution of characteristics between the two sample populations: the 5 percent sample of savers in general (referred to as the “General population”) and the savers in the six selected funds (referred to as the “Dubious funds”). There are small differences between men and women in the two samples. The shares of married and divorced individuals are higher in the dubious funds compared to the general population. 48 percent of the people who chose one of the dubious funds were married compared to 42 percent of the ones in the general population. The mean income is higher among the individuals in the devious funds for all types of marital statuses. The median income in the earnings pension is around 7 000 SEK higher among the dubious funds (Appendix A).

38 percent of the general population are living in large city areas compared to 25 percent of the individuals in the dubious funds. 35 percent of the individuals are living in rural areas among the dubious funds, while 27 percent are living in rural areas in the general

population. 20 percent of the individuals in the questionable funds are living in the North compared to 12.5 percent of the general population.

Figure 1. Distribution of age groups

The age groups are more evenly distributed in the general population compared to the individuals in the excluded funds. In the first figure, it can be seen that younger individuals were less likely to be in one of the dubious funds compared to older individuals. It is an increasingly higher number of young persons in the general population than in one of the dubious funds.

Figure 2. Distribution of income groups

In figure 2, it can be distinguished that more of the individuals in the dubious funds have contributions between 50-75 000 SEK in their annual income and premium pensions compared to the general population. There are more “high-earners” among the dubious funds (earnings above 75 000 SEK) whereas a few have earnings less than 25 000 SEK among the dubious funds.