Tools

to

implement

the

World

Health

Organization

End

TB

Strategy:

Addressing

common

challenges

in

high

and

low

endemic

countries

Seif

Al

Abri

a,*

,

Thereza

Kasaeva

b,

Giovanni

Battista

Migliori

c,

Delia

Goletti

d,e,

Dominik

Zenner

f,

Justin

Denholm

g,

Amal

Al

Maani

h,

Daniela

Maria

Cirillo

i,

Thomas

Schön

j,

Troels

Lillebæk

k,

Amina

Al-Jardani

l,

Un-Yeong

Go

m,

Hannah

Monica

Dias

n,

Simon

Tiberi

o,p,

Fatma

Al

Yaquobi

q,

Faryal

Ali

Khamis

r,

Padmamohan

Kurup

s,

Michael

Wilson

t,

Ziad

Memish

u,v,

Ali

Al

Maqbali

w,

Muhammad

Akhtar

x,

Christian

Wejse

y,z,

Eskild

Petersen

A,B,Ca

DirectorateGeneralforDiseasesSurveillanceandControl,MinistryofHealth,Muscat,Oman

b

WHOGlobalTBProgramme,Geneva,Switzerland

c

ServiziodiEpidemiologiaClinicadelleMalattieRespiratorie,IstitutiCliniciScientificiMaugeriIRCCS,Tradate,Italy

dTranslationalResearchUnit,NationalInstituteforInfectiousDiseases“LazzaroSpallanzani”—IRCCS,Rome,Italy eESCMIDStudyGrouponMycobacteria,Basel,Switzerland

f

RegionalOfficeoftheEuropeanEconomicArea,EUandNATOandInternationalOrganizationforMigration,IOM,Brussels,Belgium

g

DepartmentofInfectiousDiseases,RoyalMelbourneHospitalandVictorianTBProgramme,Melbourne,Australia

h

PaediatricInfectiousDiseases,TheRoyalHospitalandCentralDepartmentofInfectionPreventionandControl,DirectorateGeneralforDiseasesSurveillance andControl,MinistryofHealth,Muscat,Oman

i

EmergingBacterialPathogenResearchUnit,ItalianReferenceCentreforMolecularTypingofMycobacteria,SanRafaeleScientificInstitute,Milan,Italy

jDepartmentofClinicalMicrobiologyandInfectiousDiseases,KalmarHospitalandUniversityofLinköping,Sweden

kInternationalReferenceLaboratoryofMycobacteriology,WHOTBSupranationalReferenceLaboratoryCopenhagen,InfectiousDiseasePreparednessArea,

StatensSerumInstituteandGlobalHealthSection,DepartmentofPublicHealth,UniversityofCopenhagen,Copenhagen,Denmark

l

CentralPublicHealthLaboratory,DirectorateGeneralforDiseaseSurveillanceandControl,MinistryofHealth,Muscat,Oman

m

InternationalTuberculosisResearchCentre,Seoul,RepublicofKorea

n

WHOGlobalTBProgrammeUnitonPolicy,StrategyandInnovations,Geneva,Switzerland

o

InfectiousDiseases,BartsHealthNHSTrust,London,UnitedKingdom

pQueenMaryUniversityofLondon,London,UnitedKingdom q

TuberculosisandAcuteRespiratoryDiseasesSurveillance,DirectorateGeneralforDiseaseSurveillanceandControl,MinistryofHealth,Muscat,Oman

r

DepartmentofInfectiousDiseases,TheRoyalHospital,MinistryofHealth,Muscat,Oman

s

DepartmentofDiseaseSurveillanceandControl,MuscatGovernorate,Muscat,Oman

t

ZeroTBInitiative,Durban,SouthAfrica

u

PrinceMohammedbinAbdulazizHospital,MinistryofHealthandCollegeofMedicine,AlfaisalUniversity,Riyadh,SaudiArabia

v

RollingsSchoolofPublicHealth,EmoryUniversity,Atlanta,GA,USA

wDiseaseSurveillanceandControl,NorthBathinahGovernorate,Sohar,Oman x

WHOMENARegionTBProgramme,Cairo,Egypt

y

DepartmentofInfectiousDisease,AarhusUniversityHospitalandSchoolofPublicHealth,FacultyofHealthSciences,UniversityofAarhus,Denmark

z

ESCMIDStudyGroupforTravelandMigration,Basel,Switzerland

A

DirectorateGeneralforDiseaseSurveillanceandControl,MinistryofHealth,Muscat,Oman

B

InstituteforClinicalMedicine,FacultyofHealthScience,UniversityofAarhus,Denmark

CESCMIDEmergingInfectionsTaskForce,Basel,Switzerland

*Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress:salabri@gmail.com(S.AlAbri).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2020.02.042

1201-9712/©2020PublishedbyElsevierLtdonbehalfofInternationalSocietyforInfectiousDiseases.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

International

Journal

of

Infectious

Diseases

ARTICLE INFO

Articlehistory:

Received15January2020

Receivedinrevisedform21February2020 Accepted21February2020 Keywords: Tuberculosis Control Prevention LatentTBinfection Care Screening Migrants ABSTRACT

Aim:Thepurposeofthisviewpointistosummarizetheadvantagesandconstraintsofthetoolsand

strategiesavailableforreducingtheannualincidenceoftuberculosis(TB)byimplementingtheWorld

HealthOrganization(WHO)EndTBStrategyandthelinkedWHOTBEliminationFramework,withspecial

referencetoOman.

Methods: Thecase-study wasbuilt basedonthepresentations and discussionsat aninternational

workshoponTBeliminationinlowincidencecountriesorganizedbytheMinistryofHealth,Oman,which

tookplacefromSeptember5toSeptember7,2019,andsupportedbytheWHOandEuropeanSocietyof

ClinicalMicrobiologyandInfectiousDiseases(ESCMID).

Results:Existingtoolswerereviewed,includingthescreeningofmigrantsforlatentTBinfection(LTBI)

withinterferon-gammareleaseassays,clinicalexaminationforactivepulmonaryTB(APTB)including

chest X-rays, organization of laboratory services, and the existing centres for mandatory health

examinationofpre-arrivalorarrivingmigrants,includingexaminationforAPTB.Theneedforpublic–

privatepartnershipstohandletheburdenofscreeningarrivingmigrantsforactiveTBwasdiscussedat

lengthanddifferentmodelsforfinancingwerereviewed.

Conclusions:Inacountrywithahighproportionofmigrantsfromhighendemiccountries,screeningfor

LTBIisofhighpriority.Moleculartypingandthedevelopmentofpublic–privatepartnershipsareneeded.

©2020PublishedbyElsevierLtdonbehalfofInternationalSocietyforInfectiousDiseases.Thisisanopen

accessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction

Tuberculosis(TB)isoneofthetop10causesofdeathworldwide andthemostimportantcauseofdeathfromaninfectiousdisease, surpassingHIV/AIDS.In2018,TBcausedanestimated1.5million deaths(range1.4–1.6million),including251000deathsamong HIV-positivepersons (WHO,2019). The severity of national TB epidemiologyvariessignificantlyamongcountries.Worldwidein 2019,therewerefewerthan10newcasesper100000population inmosthigh-incomecountries,150–400inmostofthe30highTB burdencountries,andabove500insixcountries(WHO,2019).

TheWorldHealthOrganization(WHO)EndTBStrategyaimsto endtheglobalTBepidemicby2035,reducingglobalTBincidence andmortalityratesby90%and95%,respectively,in2035when comparedto2015(WHO,2014;Uplekaretal.,2015;Lönnrothetal., 2015).InSeptember2018,thegoalofendingTBwaselevatedtothe highestlevelatthefirst-everUNHighLevelMeetingonTBinNew York,whichbroughttogetherheadsof statesandgovernments, whomadeboldcommitmentstoacceleratetheTBresponse.Oman isa signatoryof theUNHigh-LevelPoliticalDeclarationonTB (WHO,2017).

TheWHOEndTBStrategywasdevelopedinparallelwiththe SustainableDevelopmentGoals(SDGs),andinterventionsshould beanchored in the SDGs(Lönnroth et al., 2015; Lönnroth and Raviglione,2016).Ithasbeenestimatedthatonequarterof the worldpopulationarelatentlyinfectedwithTB,havingalatentTB infection (LTBI) (Houben and Dodd, 2016), and a recent meta-analysisof prevalence surveys confirmed that 20–25% globally

haveLTBI(Cohenetal.,2019).Thisisachallengeforbothhighand lowendemiccountries,butitisevidentthattoreachthegoalofTB elimination,thereservoirofLTBIhastobeeliminatedorreduced significantly (WHO, 2015; Petersen et al., 2019; Rosales-Klintz etal.,2019;Centisetal.,2017).

In view of the progress made in several low-incidence countries,theWHOjoinedforceswiththeEuropeanRespiratory Society to adapt the WHO End TB Strategy and develop a frameworkforTBeliminationinthesecountries.Take-upofthe WHOTB Eliminationframeworkhasbeenslow(Matteelli etal., 2018)andtherearefewpublishedcountryexperiences,withthe exceptionofCyprus,Oman,andLatinAmerica(AlYaquobietal., 2018).

OmanasapathfindertoTBelimination

OmanisalowTBincidencecountry,withanannualincidence rate of less than 5.9 cases per 100 000 population in 2018 (Figure1).Forty-fivepercentofthepopulationaremigrantsfrom high-incidencecountries, i.e. morethan100 casesper yearper 100 000 population,accounting for60%of theannualTB cases (Table1;Figure2).However,severalstudieshaveindicatedthat incidenceratesbasedonnotifiedcasesmaynotfullyreflectthe burdenduetounder-reporting(Snowetal.,2018;Pandeyetal., 2017;Romanowskietal.,2019).

Thepurposeofthisviewpointistosummarizetheadvantages andconstraintsofthetoolsandstrategiesavailableforreducing the annual incidenceof TB by implementing theWHO EndTB

Strategyand the linked WHO TB Elimination Framework, with special reference toOman. In Oman, a reduction in annual TB incidencefrom59permillioninhabitants(2018)to1permillionby 2035 has to be achieved, which is the threshold defining TB elimination(Lönnrothetal.,2015).Itmaybepossibletoadvance theeliminationdateifmodellingandeffectiveimplementationof key interventions, including the roll-out of TB preventive treatment,areconducted.

Methods

The case-study was built based on the presentations and discussionsataninternationalworkshoponTBeliminationinlow incidencecountriesorganizedbytheMinistryof Health,Oman, whichtookplace fromSeptember5 toSeptember7, 2019, and supported by the WHO and the European Society of Clinical MicrobiologyandInfectiousDiseases(ESCMID).

Themeetingreviewedexistingtools,includingthescreeningof migrantsforLTBIwithinterferon-gammareleaseassays(IGRAs), clinical examination for active pulmonary TB (APTB) including chestX-rays(CXR),theorganizationoflaboratoryservices,andthe existing centres for mandatory health examination of arriving migrantsincludingexaminationfor APTB.Theneed forpublic– privatepartnershipstohandletheburdenof screeningarriving migrantsforactiveTBwasdiscussedatlengthanddifferentmodels forfinancingwerereviewed.

The TB elimination framework programme for Oman has openedmanytopicsforappliedresearch.Ithasalsoallowedthe evaluationofmodelsforpublic–privatepartnerships,community supportinthetreatmentLTBI,theevaluationofscreeningmethods forLTBIthroughlong-termfollow-up,andcomparisonofdifferent regimensforthetreatmentofLTBI,forinstance4weeksand12 weeksrifapentin/isoniazid(orrifampicin/isoniazid).

AwritingteamofglobalTBexpertswasinvitedtosummarize theavailableevidenceforthedifferentareaswithanon-systematic approach and to discuss this evidence based onOman-specific data. Several rounds of discussion were organized to reach consensusonthefinaldocument.

Background

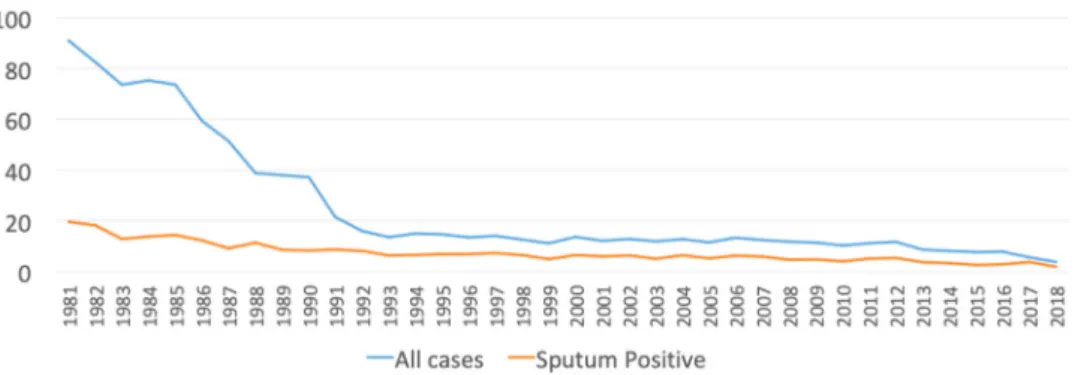

In1981,theannualincidenceofTBinOmanwasover90per 100000population(Figure1).Followingrapideconomic develop-mentinthe1980s,theincidencedeclinedsignificantlyto 20per 100000populationin1991and10per100000populationin2010 (MinistryofHealth,2018).Overthesameperiod,theproportionof migrants fromhighTBendemiccountries inAfricaandAsiaincreased toaround45%ofthepopulation.Upuntil2017,thenationalpolicyfor TBcontrolwasbasedonthescreeningofmigrantsonarrivalforAPTB withaCXR.Since2017,investigationsforAPTBhavealsoincluded sputum microscopy, culture, and PCR if there is a clinical or radiologicalsuspicionofTB.Pre-arrivalscreeningisalsoconducted inGulfCollaborationCouncilcertifiedcentresinthecountryoforigin ofmigrantsforaround90%ofthemigrants.

TheproportionsofAPTBcasesamongOmaninationalsand non-nationals have been changing, with a decreasing number in Omanis and an increasing number diagnosed in non-Omanis (Table 1). The stable incidence ratefor migrants and the slow decrease in rate for Omani nationals over the last 10 years potentiallyreflectMycobacteriumtuberculosis(Mtb)transmission from the migrant population (Aldridge et al., 2016), but that assumptionneedstobeconfirmedbygenotyping.TBinmigrants compriseseitherreactivationofLTBI,diagnosedsomeyearsafter entry,orcasesmissedbythepre-entryorat-entryscreening.

ItisoftenheldthatnewcasesofTBthatoccursomeyearsafter entrycouldbetheresultofthereactivationofLTBI(Aldridgeetal., Table1

NewtuberculosiscasesinOmaninationalsandmigrants.

Year 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 Omaninationals 214 239 245 188 184 180 190 141 98 Non-Omanis 94 98 141 146 170 147 154 122 145 Nationalsper105 10.3 11.2 11.7 8.7 8.1 7.7 6.3 4.7 3.3 Non-nationalsper105 8.1 7.1 9.2 8.7 9.8 8.1 7.7 7.1 7.3

Note:EstimatedpopulationJanuary1,2019:4992364ofwhich2994601wereOmaninationalsand1997763weremigrants(NationalCentreforStatisticsandInformation).

2016;Lillebaeketal.,2001;Lönnrothet al.,2017;Zenneretal., 2017; Kamper-Jørgensen et al., 2012a,b). Previous studieshave shownthatscreeningforactiveTBatentrydetectsonlyasmall numberofTBcases,butwillmisscasesreactivatingafterentryif screeningforLTBIisnotincluded(Abubakaretal.,2011;Kruijshaar etal.,2013),indicatingthat screeningaimedonlyatidentifying APTBcasesatentrymaymissanunknownproportionofcaseswho aredevelopingTBatalaterpoint.

TheMinistryofHealthhasestimatedthatOmanhastoreduce theincidencebyaround10%peryeartoreachthegoalofa90% reduction inthe incidencerate by2035. To reducethecurrent incidenceof59casespermillionpopulation(Table1)tolessthan1 per million by 2035 will pose significant challenges. The age distributionamongnon-OmanisisyoungerthaninOmanis,where oldercasesarelikelymorecommonlyduetoreactivationofLTBI (Figure2).

Omanfulfilsthefirstthreegoalsofthepillarsof theEndTB Strategy(Table2)andpartlyalsothefourth,“Preventivetreatment ofpersonsathighrisk,andvaccinationagainsttuberculosis”,by includinguniversalbacillusCalmette–Guérin(BCG)immunization atbirthandpreventivetreatmentofcontactsofknownactiveTB cases. The current strategy does not include the screening of migrantsfromhighlyendemiccountriesforLTBI.

Points5–8oftheTBEliminationFrameworkarepartlyfulfilled in Oman, in that there is political commitment and universal government-funded healthcare coverageand regulatory frame-worksforcasenotification,vitalregistration,qualityandrational useofmedicines,andinfectioncontrol.

Regardingpoints9and10,regarding‘intensifiedresearchand innovation’, this paper will discuss the strategies and tools availabletoreducetheincidenceinOmanby10%peryear.

Apreviousmodelling study,which reviewed sevendifferent screeningprogrammesformigrants,foundthatscreeningwithan IGRAfollowedbyashortregimen(3months)ofeitherrifampicin/ isoniazid or rifapentine/isoniazid was the most cost-effective algorithmintheUnitedKingdom(Kowada,2016;Abubakaretal., 2018).RiskgroupsamongOmaninationalsneedtobeidentified (Katelaris et al., 2019), for instance the elderly, families with previousTBcases,geographicalclustering,andprisons(Noppert et al.,2019).A study fromJapanfound thatoverall population density, age, and being a healthcare worker (HCW) were risk factorsforTB(Murakamietal.,2019).

SpecificinterventionsfornationalTBcontrolandelimination programmesintheEndTBera

Multisectoralcollaborationandpoliticalcommitment

TBisadiseaseofpovertyanddeprivation,whichcanonlybe controlledbyinvolvingmultiplestakeholdersandaddressingthe needof marginalizedgroups withahighincidence,as recently

reviewedbytheTheLancetCommissiononTB(Reidetal.,2019). The often long incubation period, the latent stage with no symptoms, and the lack of access to proper diagnostics and managementhampercontrolefforts.Politicalcommitmentiskey toaddressing thecomplex interactionbetweensocio-economic problemsandhealthcareprovision(Matteellietal.,2018).

OneexampleistheZeroTBInitiative,whichcreatessupportfor local stakeholders helping to mobilize financial and technical resources.ExamplesarethemobileunitsinruralareasofSouth Africa providing treatment, and mobile CXR units in Karachi, Pakistan (Zero TB Initiative). Such outreach is key to reach marginalized populations and will benefit from a mixture of privatefundedandpublicinitiatives.

Thegovernmentwillsupportpolicies,whichinformmigrants intheirownlanguageoftheirrighttoseekmedicalcare,thesigns and symptoms of TB, and therightto freetreatment inOman withouttheriskofbeingrepatriatedinthecaseofAPTB.TheEnd TBStrategywasreiteratedintheMoscowDeclarationadoptedat thefirstWHOGlobalMinisterialConferenceonendingTBin2017, whereministersofhealth(ZumlaandPetersen,2018)including theministerforOman,declared“Wereaffirmourcommitmentto end the TB epidemic by 2030” (WHO, 2017). The Moscow Declaration called for the development of a multisectoral accountability framework,whichwasreiterated intheUNHigh LevelMeetingPoliticalDeclarationbyheadsofstate.

ManagingLTBIinmigrants

Similar to other countries in the Gulf Cooperation Council, Omanischaracterizedbyalocalpopulationwithalowincidenceof TBandalargepopulationofmigrantswithahigherincidenceofTB. ManagingLTBIinthispopulationisaclearpriority.Thetopicwas discussedwithfocusonbothscreeninganddiagnosticchallenges, as well as on treatment(Shete et al., 2018; Wildet al., 2017;

Shedrawyetal.,2017;Zenneretal.,2017;Kunstetal.,2017;Dara etal.,2017).AstudyfromtheNetherlandsfoundthat themost importantpredictorfordevelopingactiveTBwasknownexposure, but being foreign-bornwas an independent risk factor (Erkens etal.,2016),and72%ofnewTBcaseswereforeign-born(vande Bergetal.,2017).

DiagnosisofLTBI

MandatoryhealthexaminationsofmigrantsinOmantakeplace atpre-entry,onarrival,andthenevery2–4yearsaspartofvisa renewal. A CXR is included in these medical examinations, potentiallyidentifyingcasesofAPTB.

ApilotstudyfromOmanfoundthat21%ofmigrantsfromAsia and31%fromAfricawereIGRA-positive(Yaquobietal.,submitted). Screening for LTBI is usuallyperformed bytuberculin skin test (TST)orIGRA,whichbothdetectcell-mediatedimmuneresponses againstTBantigens(Getahunetal.,2015;Golettietal.,2018a,b).

Table2

PillarsoftheEndTBstrategy.

Integrated,patient-centredcareandprevention

1.Earlydiagnosisoftuberculosisincludinguniversaldrug-susceptibilitytesting,andsystematicscreeningofcontactsandhigh-riskgroups 2.Treatmentofallpeoplewithtuberculosisincludingdrug-resistanttuberculosis,andpatientsupport

3.Collaborativetuberculosis/HIVactivities,andmanagementofcomorbidities 4.Preventivetreatmentofpersonsathighrisk,andvaccinationagainsttuberculosis Boldpoliciesandsupportivesystems

5.Politicalcommitmentwithadequateresourcesfortuberculosiscareandprevention 6.Engagementofcommunities,civilsocietyorganizations,andpublicandprivatecareproviders

7.Universalhealthcoveragepolicy,andregulatoryframeworksforcasenotification,vitalregistration,qualityandrationaluseofmedicines,andinfectioncontrol 8.Socialprotection,povertyalleviationandactionsonotherdeterminantsoftuberculosis

Intensifiedresearchandinnovation

9.Discovery,developmentandrapiduptakeofnewtools,interventionsandstrategies 10.Researchtooptimizeimplementationandimpact,andpromoteinnovations

ThesetestscannotdistinguishactiveTBfromLTBI.Eventhough IGRAshaveseveral advantagescompared toTST,theyaremore expensive, rely on blood sampling, and require a diagnostic laboratory(Paietal.,2014).Inimmunocompetentsubjects,IGRAs haveaveryhighnegativepredictivevalue(NPV;>99%)butasthe testsrelyonthecell-mediatedimmuneresponses,thereisariskof false-negativesfromimmunosuppression.Forthe QuantiFERON-TBGold(QFT)test,thereisalsoincreasingawarenessthatagrey zonerange(atleast0.20–0.70IU/ml)shouldbeusedaroundthe cut-off(0.35IU/ml) to avoid both false-negative results due to recent exposure or immunosuppression and also false-positive results(Paietal.,2014).Itshouldbenotedthatthefalse-negative rateofanIGRAinpatientswithactiveTBhasbeenreportedtobe approximately12%(Nguyenetal.,2018).ThusIGRAscreeningfor LTBImaynotidentifyallcasesofactiveTB.However,conversely,a studyfromtheUKfoundthatpre-entryscreeningwasstronglyand independently associated with fewer APTB cases among new migrants(Berrocal-Almanzaetal.,2019).

ManagementofLTBIinmigrantstoOman

ApragmaticapproachtoreduceTBincidencecouldbetoselect themigrantswithastronglypositiveIGRAof>4IU/mlandoffer thempreventivetherapyof3monthsofcombinedrifampicinor rifapentinandisoniazid.

Twostudies(Winjeetal.,2018;Andrewsetal.,2017)foundthat individuals witha strongly positive (>4IU/ml) IGRA test had a relativeriskof30ofdevelopingAPTBwithinthenext2years.A studyfromtheUKfoundanapproximatelyfive-timeshigherrisk comparedtobaselinefordevelopingAPTBinsubjectwithaTST >15mm, positive T-Spot.TB, or positive IGRA (Abubakar et al., 2018).However,afollow-upstudyfoundthathigherthresholdsfor QFT,T-Spot.TB,andTSTmodestlyincreasedthepositivepredictive value (PPV) for incident TB, but markedly reduced sensitivity (Guptaetal.,2019).

In 2018, 943 377 migrants were examined in the medical migrantexaminationcentresinOman,and33%(311314)ofthem were new arrivals. The study of IGRA reactivity in migrants (Yaquobietal.,submitted)showedthat22.4%hadapositiveIGRA, i.e.,69734outofthe311314newarrivals.Shouldall69734receive treatmentforlatentTB?

MigrantsusuallystayinOmanforanaverageof4yearsandit canbearguedthatwithalowormedianreactivity(0.35–4IU/ml) and without known risk factors for developing active TB, the personsshouldbeinformedabouttheirstatusofLTBIandadvised to seek treatment at their own expense. However, we could considerprioritizingfortreatmentonlymigrantswithastrongly positive QFT of >4IU/ml or those with risk factors (such as immunosuppression) and a positive QFT (>0.35IU/ml). This strategywouldreducethenumberofpersonsofferedtreatment from69 734 to 17 224 (24%). This is still a high number, but distributedinthemajorcitiesthetaskshouldbemanageableina public–privatepartnershipprogramme.

Extendingtheservicebydevelopingpublic–privatepartnerships In2018,3millionoftheestimated10millionpeoplewithTB worldwidewere‘missed’bynationalTBprogrammes(NTPs)(WHO, 2019).Two-thirdsofthemarethoughttoaccessTBtreatmentof questionablequalityfrompublicandprivateproviderswhoarenot engagedbytheNTPs.Thequalityofcareprovidedinthesesettingsis oftennotknownorsubstandard(WHO,2019).Toclosethesegaps, theWHOandpartnershavelaunchedanewroadmaptoscaleupthe engagement ofpublicandprivatehealthcareproviders(WHO,2018). AlsoinOman,thefuturechallengesoftheTBcontrolprogramme need resources provided by the private health sector, both in diagnosticsandthemanagementofLTBI.

Thegovernmentiscommittedtoprovidingtreatmentforboth LTBIandactiveTB,tobothOmaninationalsandmigrants.Thiswill bedoneeitherinpublicorprivatefacilities.

Involvement of the private sector in the diagnosis and management of LTBI requires a quality control programme for the diagnostic tests used and regular reporting of treatment outcomes, including compliance. The government needs to develop models for cost covering of services – diagnostic and clinical–providedintheprivatesectorwithintheframeworkof universal health coverage (UHC), as has already been done successfully in countries such as Pakistan, Bangladesh, India, andIndonesia.UHCmeansthatallpeoplehaveaccesstothehealth services they need, when and where they need them, without financialhardship,andthisispartoftheSDGs(WHOUHC,2019). UHCwasaddressedbyahigh-levelmeetingattheUnitedNations GeneralAssembly(UNGA)onSeptember23,2019(WHOUNGA, 2019). The Oman Minister of Health, at a side event held on multisectoral action to end TB by the WHO and the Russian FederationattheUNGA,stressedtheneedforgreatercommitment in reaching vulnerable groups such as migrants. He called for greaterpartnershipacrossallsectors,includingtheprivatesector, toreachthisgoal.

TheprivatehealthsectorinOmaniscapableofandwillingto handlescreeningforLTBIandfollow-uptreatment.Thekeyisthe financial model. There are two options: (1) an insurance paid modelwheretheemployerresponsibleforthemigrantworkerhas insurancethatcoversthediagnosisandmanagementofLTBI;and (2)amodelwheretheprivatesectorclinicsarereimbursedbythe governmentafterthepricefortheservicehasbeennegotiated. Theincentivesthatcouldbeofferedcouldinclude accreditation and positive branding of collaborative private sector health facilities,aswellasaccesstonewtoolssuchasrapiddiagnostic testsandnewdrugsthatarecurrentlyonlyavailableinthepublic sector.

Developingmolecularcharacterizationbywholegenomesequencing (WGS)touncovertransmissionroutesanddefineclustersanddetect genotyperesistance

AsinglestudyfromOman usedspoligotypingtoexplorethe geneticpopulationstructureandclusteringofMtbisolatesamong nationalsandimmigrants(Al-Manirietal.,2010).Thestudyfound a predominance of thestrain families commonlyfound onthe Indiansub-continent.Ahighproportionofimmigrantstrainswere in the same clusters as Omani strains (Al-Maniri et al., 2010). However, spoligotyping has a very low discriminatory power comparedtoWGS.

Genotyping Mtb strains from TB patients over time pro-vides detailed information on the Mtb transmission dynamics (Folkvardsenet al.,2017; Andrésetal.,2019), andit ispossible to determine transmission among and between nationalities (Kamper-Jørgensenet al.,2012a).Thisinformation canbe used tooptimizethepublichealthmanagementofTB,e.g.bydirecting the TB control efforts to specific risk-groups (Karmakar et al., 2019).AstudyfromCopenhagenfoundaprevalencerateofAPTBof 3%inhomelesspeopleidentifiedbysputumculture(Jensenetal., 2015).

Specifically in Oman, WGS will be useful to determine the amountoftransmissionbetweenmigrantworkersandOmanisand toidentifyhigh-riskgroupsandhotspotsforactiveTBtransmission withinthecountry.

In addition, systematic use of WGS onall Mtb isolates will allowtheemergenceof drugresistance tobemonitoredand, if implemented fromearly liquid culture,couldallowthe costof phenotypicdrugsensitivitytestsonstrainsthatarefullywild-type for first-line drugs to be reduced. This strategy will be fully

compliantwithpillar1:earlydiagnosisofTBincludinguniversal drug-susceptibilitytesting,and systematicscreeningof contacts andhigh-riskgroups.TheOmanCentralPublicHealthLaboratory has received a grant from the Oman Research Council on “UnderstandingTBtransmissionandepidemiologyusing molecu-larandgeo-spatialmethods”,andthiswillbeincorporatedintothe routinesurveillanceinthefuture.

Patient-centredcareincludingtreatmentsupport

The key challenge with programmatic LTBI screening is compliance with preventive treatment (Frieden and Sbarbaro, 2007;Newelletal.,2006).ArecentreviewofLTBItreatmentin migrantsfoundanoverallpoorlevelofcompliance(Greenaway etal.,2018),andonepossibilityistoextendthecommunity-based treatmentsupporttocoverpreventivetreatmentofLTBI. Adher-encetopreventivetreatmentofLTBIinfectioninOmanwasfound tobe42%amongHCWs(Khamisetal.,2016).During2yearsof community-basedcaredeliveryinMuscatGovernorate,18outof 27OmanipulmonaryTBpatientsincludedin2017andallOmani nationalswith pulmonary TB (n=16) in 2018, except two new cases, were on community-based care delivery. There was a significant reduction in average length of hospital stay for pulmonary TB patients when compared to previous years (27 daysin2017and28daysin2018,comparedto61daysin2016). Thismayhelpwiththeacceptabilityofpreventivetreatment among recipients and may contribute to reduce in-hospital transmission (Migliori et al., 2019). Even though community preventivetreatmentsupportisnot presentlyofferedtopeople withLTBI,someformofsupporttoensureadherencethatiseither family or community based would be desirable. This could be enhanced through the use of digital and video technology. To increase compliance, the 3-month course with a rifapentin or rifampicin/isoniazidcombinationismuchpreferred.

TBinhigh-riskgroups Healthcareworkers

TheUnitedStatesrecently(2019)reviseditsrecommendations forthesurveillanceofTBin HCWs,becausetheriskwas deter-minedtobeverylow(Sosaetal.,2019).Thenewrecommendations includebaseline(pre-placement)TBscreeningwithanindividual riskassessment and symptom evaluationforall personnel,and testingwithanIGRAorTSTforpersonnelwithknownexposureto TB.ArecentstudyfromKoreaincluding3920HCWstestedwithan IGRAfoundthat893(22.8%)hadLTBI(Hanetal.,2019).Thestudy alsofoundthattheacceptanceratefortreatmentofLTBIwas64.6% with3monthsofrifampicin/isoniazidor4monthsofrifampicin. TBinchildren

TBcasesinOmanichildrenareshowninTable3.Childrenpose uniquechallengestoTBcontrolprogrammes,asinfectioninthis

age group is considered a sentinel event indicating recent transmission.

Theimportanceandpriorityofchildrenasaspecialhigh-risk groupwashighlightedintheWHOEndTBStrategy(WHO,2014).A recentstudyestimatedthat70%ofactiveTBinchildreninWest Africaisnotdiagnosed(TDR,2019).

Themaininterventionstopreventnewcasesin childrenare vaccination with the bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine, contacttracingandscreeningforactiveTB,andtreatmentofLTBI (Thomas,2017).BCGimmunizationhasbeenterminatedinmany lowendemiccountriesduetomoresideeffectsthanpotentially preventedTBcases.Amodellingstudyofthepreventiveeffectof BCGvaccinationfoundthata92%BCGcoverageatbirthreducedTB deaths in the globalbirth cohort by 2.8% (0.1–7.0%, confidence interval)byage15years,andthata100%coverageatbirthreduced TBdeathsby16.5%(0.7–41.9%,CI)(Royetal.,2019).

The WHO has strongly recommended treatmentfor LTBI in children under 5 years of age who are household contacts of pulmonaryTBcases(WHO,2018).Theperformanceofscreening testsliketheTSTandIGRAispoorlydocumentedinchildrenbelow 2yearsofage(Box1).

There is an increasing need for microbiological (culture) confirmationofTBdisease,whichislimitedbythepaucibacillary natureofTBinchildren.Furthermore,thenewerrapidmolecular testsarepositiveintheminorityofchildren,generally<25–40%of childrenwithTBdisease(WHO,2013;Jenkinsetal.,2014). Screeningalgorithmsandcost-effectiveness

CurrentLTBIscreeningislimitedbytherelativelylowPPVof available tests(Rangakaetal.,2012).AlthoughthePPVappears betterforsomeIGRAtestscomparedwiththeTST(Abubakaretal., 2018; Gupta et al., 2019), defining reactivation risk varies significantlybypopulationgroup.Theselectionofthepopulation group determines the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of the approach (Zenneret al.,2017).Thus screeningthose at highest riskofreactivation,suchaspersonswithimmunosuppression,is mostcost-effective(Greenawayetal.,2018),andthishasledtothe recommendation to focus on these high-risk groups for LTBI control(WHO,2017;ECDC,2018).InthecontextofTBelimination and thelargeestimatednumbersofpersonswithLTBI(Houben andDodd,2016),strategiesneedtoincludefurthergroups.

There is a conditional recommendation for screening of a numberofgroups,includingrecentmigrantsfromhighincidence countries(WHO, 2017LTBIguidelines).Awayforwardis strati-fication byepidemiological risk factors (countryof origin,time sincearrival),demographicfactors(agegroups),co-morbidities,or socialriskfactors.Thereisnoconsensusonthresholds(Greenaway et al.,2018), and practices varysignificantlybetweencountries (Kunstet al.,2017).Thedecision onthresholdswilldependon preferences and choices around the population impact of screening, individual risks and benefits, and cost-effectiveness.

Table3

Tuberculosiscasesinchildren.

Year Omani Non-Omani Total

2010 9 1 10 2011 9 2 11 2012 12 0 12 2013 10 4 14 2014 6 1 7 2015 9 1 10 2016 6 2 8 2017 7 1 8 2018 6 0 6

Box1.Factbox. TheEndTBtargetsare:

1 A 95% reduction by 2035 in number of TB deaths comparedwith2015;

2 A90%reductionby2035inTBincidenceratecompared with2015;

3 ZeroTB-affectedfamiliesfacingcatastrophiccostsdueto TBby2035(WHO,2015).

TheUKhaschosenitsincidencethresholdof150per100000for theLTBIprogrammebasedoncost-effectivenessstudies(Pareek etal.,2011).

Modelling

PartoftheEndTBFrameworkistoempowerastrongand self-sustained TB research community in low- and middle-income countrieswithahighTBburden.InOman,thenextrevisionofthe NationalTBStrategicPlanwillincludeanationalresearchplan.

Thescaleofthepossibleinterventionswillcreateasubstantial burden, both in terms of financial costs and population or healthcaresystemimpact.Itisthereforecriticalthatinterventions aredesigned rationally,andoptimizedwithregardstomaximal impactand minimal burdens.Mathematical modellingprovides important tools for the assessment of potential strategies, and allowsforcomparisonofawiderangeofpossibleapproacheswith relativelyminimalresourceimplications.

In the specific context of Oman, mathematical modelling approaches could be used to consider the optimal screening algorithmsforlatentandactiveTBinmigrantsandnationals,and toevaluatetheefficiencyofdifferentstrategies.Thiscouldinclude theselectionofthemostappropriatetests,testingfrequency,and cost-effectiveapproachestoTBincidencereduction.Oneobvious taskfor a modelling analysisis tolook at active TB in Omani nationalsinordertoprovidedataindicatingwhetherscreeningfor latentTB ofpartof theOmani populationwould bebeneficial. Modelling can identify high-risk groups in the community, whethernationalsormigrants.

Research

Thereisaneedforoperationalresearchaimedatoptimizingthe cost-effectivenessofthedifferentinterventions,identifying high-risk groups in thecommunity, follow-up of personswith LTBI without treatment, and stratification of the risk of developing activeTBbasedonthestrengthoftheIGRAlevelorTSTreactivity (Golettietal.,2018b;Kiketal.,2018).

Anobviousresearchprojectwouldbetocompare3monthsof preventivetreatmentwith1month(Swindellsetal.,2019).The existingmandatoryhealthinvestigationincludingaCXRevery2–4 yearswillensurethatfollow-upis doneifthemigrantstaysin Oman. This will allow studies on the effectiveness and cost-effectivenessofactiveTB screeningincombinationwithLTBIor LTBIonly.

Theextensionoftreatment supportservicestocoverLTBIin ordertoincreasecompliance anda general switchfrom6or 9 months of isoniazid to 3 months of rifapentin or rifampicin/ isoniazid are needed. The planned screening of migrants with mandatory follow-up every 2 years will also allow Oman to generatedataontheefficacyofthescreeningassayandefficacyof thetreatmentoffered,asitisexpectedthatmostactiveTBcases willdevelopafterarrival.

Models for public–private partnershipstoenlargeaffordable coverageforall,needtobedeveloped,tried,andvalidated.Arecent studyfromAustralia compared centraland decentralized man-agement in TB programmes and concluded that central pro-grammeswerebettersuitedtochangeandchallenges(Degeling etal.,2019)

Conclusions

FulfillingtheWHOEndTBStrategyandtheWHOTBElimination Frameworkrequiresacomprehensivepackageofstrategies.This review of the challenges of achieving TB elimination in a low endemiccountrylikeOmanwithahighnumberofmigrantsfrom

highTBendemiccountries,clearlyshowsthatscreeningforLTBI andthetreatmentofeitherallcaseswithLTBIorhigh-riskcases,is a key interventiontoreduce newcases.In more high-endemic settings,theidentificationofhigh-riskgroupsandscreeningthese forLTBI,followedbypreventivetreatment,isaninitialstrategy.

Molecular typing of all new cases in both nationals and migrantsisneededtoidentifyclustersandfullyunderstandthe transmissionchains.

Thedevelopmentofpublic–privatepartnershipsisneededto handletheburdenofscreeningandtreatingmigrantsforLTBI.This requirespoliticaldecisionsandqualitycontrolofdiagnosticsand management in private healthcare facilities. With high-level politicalcommitmentinOmantoeliminateTB,thecountrycould be among the first to achieve TB elimination and serve as a pathfinderfortheregionandtheworld.

Conflictofinterest

Theauthorsdeclaresnoconflictofinterest. Acknowledgements

Thispaperisbasedonthepresentationsanddiscussionsatan international workshop on TB elimination in low-incidence countries, which tookplace fromSeptember5 toSeptember 7, 2019, and was hosted by the Ministry of Health, Oman and supported by the WHO and ESCMID. Financial support was received fromQiagen, Cepheid,Advanced HealthcareSolutions, Pfizer, and MSD. This article is part of a supplement entitled Commemorating World TuberculosisDay March 24th, 2020: “IT'S TIMETOFIND,TREATALLandENDTUBERCULOSIS!”publishedwith support from an unrestricted educational grant from QIAGEN SciencesInc.

References

AbubakarI,LipmanM,AndersonC,DaviesP,ZumlaA.TuberculosisintheUK—time toregaincontrol.BMJ2011;343:d4281.

Abubakar I,Drobniewski F,Southern J, SitchAJ, JacksonC, Lipman M,etal. Prognosticvalueofinterferon-greleaseassaysandtuberculin skintestin predicting the development of active tuberculosis (UK PREDICT TB): a prospectivecohortstudy.LancetInfectDis2018;18:1077–87.

AldridgeRW,ZennerD,WhitePJ,WilliamsonEJ,MuzyambaMC,DhavanP,etal. Tuberculosis in migrants moving from high-incidence to low-incidence countries: a population-basedcohort study of 519955 migrants screened beforeentrytoEngland,Wales,andNorthernIreland.Lancet2016;388:2510–8.

Al-ManiriA,SinghJP,Al-RawasO,AlBusaidiS,AlBalushiL,AhmedI,etal.A snapshotofthebiodiversityandclusteringofMycobacteriumtuberculosisin Omanusingspoligotyping.IntJTubercLungDis2010;14:994–1000.

AlYaquobiF,Al-AbriS,Al-AbriB,Al-AbaidaniI,Al-JardaniA,D’AmbrosioL,CentisR, MatteelliA,ManisseroD,MiglioriGB.Tuberculosiselimination:adreamora reality?ThecaseofOman.EurRespirJ.2018;51(1)pii:1702027.

AndrésM,vanderWerfMJ,KödmönC,AlbrechtS,HaasW,FiebigL.Surveystudy group.Molecularandgenomictypingfortuberculosissurveillance:asurvey studyin26Europeancountries.PLoSOne2019;14(3)e0210080.

AndrewsJR,NemesE,TamerisM,LandryBS,MahomedH,McClainJB,etal.Serial QuantiFERONtestingandtuberculosisdiseaseriskamongyoungchildren:an observationalcohortstudy.LancetRespirMed2017;5:282–90.

Berrocal-AlmanzaLC,HarrisR,LalorMK,MuzyambaMC,WereJ,O’ConnellAM,etal. Effectivenessofpre-entryactivetuberculosisandpost-entrylatenttuberculosis screeninginnewentrantstotheUK:aretrospective,population-basedcohort study.LancetInfectDis2019;19:1191–201.

CentisR,D’AmbrosioL,ZumlaA,MiglioriGB.Shiftingfromtuberculosiscontrolto elimination: wherearewe? Whatare thevariablesand limitations?Isit achievable?.IntJInfectDis2017;56:30–3.

Cohen A, Mathiasen VD, SchönT, Wejse C. The global prevalence of latent tuberculosis:asystematicreviewandmeta-analysis.EurRespirJ2019;54(3) pii:1900655.

DaraM,SulisG,CentisR,D’AmbrosioL,deVriesG,DouglasP,etal.Cross-border collaborationforimprovedtuberculosispreventionandcare:policies,toolsand experiences.IntJTubercLungDis2017;21:727–36.

DegelingC,CarrollJ,DenholmJ,MaraisB,DawsonA.EndingTBinAustralia: organizationalchallengesforregionaltuberculosisprograms.HealthPolicy 2019;(November)pii:S0168-8510(19)30278-7.[Epubaheadofprint].

ErkensCG,SlumpE,VerhagenM,SchimmelH,CobelensF,vandenHofS.Riskof developing tuberculosis disease among persons diagnosed with latent tuberculosisinfectionintheNetherlands.EurRespirJ2016;48:1420–8.

vandeBergS,ErkensC,vanRestJ,vandenHofS,KamphorstM,KeizerS,etal. EvaluationoftuberculosisscreeningofimmigrantsintheNetherlands.Eur RespirJ2017;50(4)pii:1700977.

FolkvardsenDB,NormanA,AndersenÅB,MichaelRasmussenE,JelsbakL,Lillebaek T.Genomicepidemiologyofamajormycobacteriumtuberculosisoutbreak: retrospectivecohortstudyinalow-incidencesettingusingsparsetime-series sampling.JInfectDis2017;216:366–74.

FriedenTR,SbarbaroJA.Promotingadherencetotreatmentfortuberculosis:the importanceof direct observation. Bull WorldHealth Organ 2007;85(May (5)):407–9.

Getahun H,Matteelli A, AbubakarI, Aziz MA, BaddeleyA, BarreiraD, et al. ManagementoflatentMycobacteriumtuberculosisinfection:WHOguidelines forlowtuberculosisburdencountries.EurRespirJ2015;46:1563–76.

GolettiD,LeeMR,WangJY,WalterN,OttenhoffTHM.Updateontuberculosis biomarkers:fromcorrelatesofrisk,tocorrelatesofactivediseaseandofcure fromdisease.Respirology2018a;23:455–66.

GolettiD,LindestamArlehamnCS,ScribaTJ,AnthonyR,CirilloDM,AlonziT,etal. Canwepredicttuberculosiscure? Whattools areavailable?. EurRespirJ 2018b;52:pii:1801089.

Greenaway C, PareekM, AbouChakra CN,Walji M,Makarenko I, etal. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of screening for latent tuberculosis amongmigrantsintheEU/EEA:asystematicreview.EuroSurveill2018;23: 17-00543.

Gupta RK, Lipman M,Jackson C, Sitch A, Southern J, Drobniewski F, et al. Quantitativeinterferongammareleaseassayandtuberculinskintestresultsto predictincidenttuberculosis:aprospectivecohortstudy.AmJRespirCritCare Med 2019;(December), doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201905-0969OC [Epubaheadofprint].

HanSS,LeeSJ,YimJJ,SongJH,LeeEH,KangYA.Evaluationandtreatmentoflatent tuberculosisinfectionamonghealthcareworkersinKorea:amulticentrecohort analysis.PLoSOne2019;14:e0222810.

HoubenRMGJ,DoddPJ.Theglobalburdenoflatenttuberculosisinfection:a re-estimationusingmathematicalmodelling.PLoSMed2016;13(10)e1002152.

JenkinsHE,TolmanAW,YuenCM,ParrJB,KeshavjeeS,Pérez-VélezCM,etal. Incidenceofmultidrug-resistanttuberculosisdiseaseinchildren:systematic reviewandglobalestimates.Lancet2014;383(9928):1572–9.

JensenSG,OlsenNW,SeersholmN,LillebaekT,WilckeT,PedersenMK,etal. Screening for TBby sputum culturein high-risk groups in Copenhagen, Denmark:anovelandpromisingapproach.Thorax2015;70:979–83.

Kamper-Jørgensen Z, Andersen AB, Kok-Jensen A, Bygbjerg IC, Thomsen VO, LillebaekT. Characteristics of non-clusteredtuberculosisin a low burden country.Tuberculosis(Edinb)2012a;92(May(3)):226–31.

Kamper-JørgensenZ,AndersenAB,Kok-JensenA,Kamper-JørgensenM,BygbjergIC, AndersenPH,etal.Migranttuberculosis:theextentoftransmissioninalow burdencountry.BMCInfectDis2012b;18(March(12)):60.

KarmakarM,TrauerJM,AscherDB,DenholmJT.HypertransmissionofBeijing lineageMycobacteriumtuberculosis:systematicreviewandmeta-analysis.J Infect 2019;(October), doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jinf.2019.09.016 pii: S0163-4453(19)30287-7.[Epubaheadofprint].

KatelarisAL,JacksonC,SouthernJ, GuptaRK,DrobniewskiF,LalvaniA,etal. EffectivenessofBCGvaccinationagainstMycobacteriumtuberculosisinfectionin adults:across-sectional analysisofa UK-basedcohort.J InfectDis2019; 221:146–55.

KhamisF,Al-LawatiA,Al-ZakwaniI,Al-AbriS,Al-NaamaniJ,Al-HarthiH,etal. Latenttuberculosisinhealthcareworkersexposedtoactivetuberculosisina tertiarycarehospitalinOman.OmanMedJ2016;31(4):298–303.

KikSV,SchumacherS,CirilloDM,ChurchyardG,BoehmeC,GolettiD,etal.An evaluationframeworkfornewteststhatpredictprogressionfromtuberculosis infectiontoclinicaldisease.EurRespirJ2018;52:pii:1800946.

KowadaA.Costeffectivenessofinterferon-gammareleaseassayfortuberculosis screeningusingthreemonthsofrifapentineandisoniazidamonglong-term expatriates from low to high incidence countries. Travel Med Infect Dis 2016;14:489–98.

KruijshaarME, AbubakarI,StaggHR,PedrazzoliD, LipmanM.Migrationand tuberculosisintheUK:targetingscreeningforlatentinfectiontothoseat greatestriskofdisease.Thorax2013;68:1172–4.

Kunst H, Burman M,Arnesen TM, Fiebig L, Hergens MP, Kalkouni O, et al. TuberculosisandlatenttuberculousinfectionscreeningofmigrantsinEurope: comparativeanalysisofpolicies,surveillancesystemsandresults.IntJTuberc LungDis2017;21:840–51.

LillebaekT,AndersenAB,BauerJ,DirksenA,GlismannS,deHaasP,etal.Riskof Mycobacteriumtuberculosistransmissioninalow-incidencecountrydueto immigrationfromhigh-incidenceareas.JClinMicrobiol2001;39:855–61.

LönnrothK,MiglioriGB,AbubakarI,D’AmbrosioL,deVriesG,DielR,etal.Towards tuberculosiselimination:anactionframeworkforlow-incidencecountries.Eur RespirJ2015;45:928–52.

LönnrothK,RaviglioneM.TheWHO’snewEndTBStrategyinthepost-2015eraof thesustainabledevelopmentgoals.TransRSocTropMedHyg2016;110:148–50.

LönnrothK,MorZ,ErkensC,BruchfeldJ,NathavitharanaRR,vanderWerfMJ,etal. Tuberculosis in migrants in low-incidence countries: epidemiology and interventionentrypoints.IntJTubercLungDis2017;21:624–37.

Matteelli A, Rendon A, Tiberi S, Al-Abri S, Voniatis C, Carvalho ACC, et al. Tuberculosiselimination:wherearewenow?.EurRespirRev2018;27:180035.

MiglioriGB,NardellE,YedilbayevA,D’AmbrosioL,CentisR,TadoliniM,etal.Reducing tuberculosis transmission: a consensus document from the World Health OrganizationRegionalOfficeforEurope.EurRespirJ2019;53:pii:1900391.

MinistryofHealth.Annualstatisticalreport.2018Muscat,Oman.

MurakamiR,MatsuoN,UedaK,NakazawaM.Epidemiologicalandspatialfactors fortuberculosis:amatchedcase-controlstudyinNagata,Japan.IntJTuberc LungDis2019;23:181–6.

NationalCentreforStatisticsandInformation,dataportal,GovernmentofOman.

https://data.gov.om/OMPOP2016/population?region=1000010-oman&indica-tor=1000140-total-population&nationality=1000010-omani.[Accessed22 De-cember2019].

Newell JN, Baral SC,Pande SB, Bam DS,Malla P. Family-member DOTS and community DOTS for tuberculosis control in Nepal: cluster-randomised controlledtrial.Lancet2006;367:903–9.

NguyenDT,TeeterLD,GravesJ,GravissEA.Characteristicsassociatedwithnegative interferon-greleaseassayresultsinculture-confirmedtuberculosispatients, Texas,USA,2013–2015.EmergInfectDis2018;24:534–40.

NoppertGA,Yang Z,ClarkeP, DavidsonP, YeW,Wilson ML.Contextualizing tuberculosisriskintimeandspace:comparingtime-restrictedgenotypiccase clustersandgeospatialclusterstoevaluatetherelativecontributionofrecent transmissiontoincidenceofTBusingnineyearsofcasedatafromMichigan, USA.AnnEpidemiol2019;40(December)21–27.e3.

PaiM,DenkingerCM,KikSV,RangakaMX,ZwerlingA,OxladeO,etal.Gamma interferonreleaseassaysfordetectionofMycobacteriumtuberculosisinfection. ClinMicrobiolRev2014;27:3–20.

PandeyS,ChadhaVK,LaxminarayanR,ArinaminpathyN.Estimatingtuberculosis incidencefromprimarysurveydata:amathematicalmodelingapproach.IntJ TubercLungDis2017;21:366–74.

PareekM,WatsonJP,OrmerodLP,KonOM,WoltmannG,WhitePJ,etal.Screeningof immigrantsintheUKforimportedlatenttuberculosis:amulticentrecohort studyandcost-effectivenessanalysis.LancetInfectDis2011;11:435–44.

PetersenE,ChakayaJ,JawadFM,IppolitoG,ZumlaA.Latenttuberculosisinfection: diagnostictestsandwhentotreat.LancetInfectDis2019;19:231–3andauthors replyLancetInfectDis2019;19:691-2.

RangakaMX,WilkinsonKA,GlynnJR,LingD,MenziesD,Mwansa-KambafwileJ,etal. Predictivevalueofinterferon-greleaseassaysforincidentactivetuberculosis:a systematicreviewandmeta-analysis.LancetInfectDis2012;12:45–55.

ReidMJA,ArinaminpathyN,BloomA,BloomBR, BoehmeC,ChaissonR,etal. Buildingatuberculosis-freeworld:theLancetCommissionontuberculosis. Lancet2019;393:1331–84.

RomanowskiK,BaumannB,BashamCA,AhmadKhanF,FoxGJ,JohnstonJC. Long-termall-causemortalityinpeopletreatedfortuberculosis:asystematicreview andmeta-analysis.LancetInfectDis2019;19:1129–37.

Rosales-KlintzS,BruchfeldJ,HaasW,HeldalE,HoubenRMGJ,vanKesselF,etal. Guidanceforprogrammaticmanagementoflatenttuberculosisinfectioninthe EuropeanUnion/EuropeanEconomicArea.EurRespirJ2019;53(1)pii:1802077.

RoyP,VekemansJ,ClarkA,SandersonC,HarrisRC,WhiteRG.Potentialeffectofage ofBCGvaccinationonglobalpaediatrictuberculosismortality:amodelling study.LancetGlobHealth2019;7:e1655–63.

Shedrawy J, Siroka A, Oxlade O, Matteelli A, Lönnroth K. Methodological considerations for economic modelling of latent tuberculous infection screeninginmigrants.IntJTubercLungDis2017;21:977–89.

ShetePB,BocciaD,DhavanP,GebreselassieN,LönnrothK,MarksS,etal.Defininga migrant-inclusivetuberculosisresearchagendatoendTB.IntJTubercLungDis 2018;22:835–43.

SnowKJ,SismanidisCS,DenholmJ,SawyerSM,GrahamSM.Theincidenceof tuberculosisamongadolescentsandyoungadults:aglobalestimate.EurRespir J2018;51(2)pii:1702352.

Sosa LE,NjieGJ, LobatoMN,BamrahMorrisS,BuchtaW,et al.Tuberculosis screening,testing,andtreatmentofU.S.HealthCarePersonnel: recommen-dationsfromtheNationalTuberculosisControllersAssociationandCDC,2019. MMWRMorbMortalWklyRep2019;68:439–43.

SwindellsS,RamchandaniR,GuptaA,BensonCA,Leon-CruzJ,MwelaseN,etal.One monthofrifapentineplusisoniazidtopreventHIV-relatedtuberculosis.NEnglJ Med2019;380:1001–11.

TDR(SpecialProgrammeforResearchandTraininginTropicalDiseases).Improving detectionofTBinchildren:asmartersolution.Geneva:TCR;201930October.

https://www.who.int/tdr/news/2019/smarter-solution-missing-tb-casess-in-children/en/.[Accessed26November2019].

ThomasTA.Tuberculosisinchildren.PediatrClinNorthAm2017;64(4):893–909.

UplekarM,WeilD,LonnrothK,JaramilloE,LienhardtC,DiasHM,etal.WHO’snew endTBstrategy.Lancet2015;385:1799–801.

Winje BA, White R, Syre H, Skutlaberg DH, Oftung F, Mengshoel AT,et al. Stratificationbyinterferon-greleaseassaylevelpredictsriskofincidentTB. Thorax2018;pii:thoraxjnl-2017-211147.

Wild V, Jaff D, Shah NS, Frick M. Tuberculosis, human rights and ethics considerations along theroute of a highlyvulnerable migrantfrom sub-SaharanAfricatoEurope.IntJTubercLungDis2017;21:1075–85.

World Health Organization. Automated real-time nucleic acid amplification technologyforrapidandsimultaneousdetectionoftuberculosisandrifampicin resistance: Xpert MTB/RIF assay for the diagnosis of pulmonary and extrapulmonary TBin adults andchildren. Policy update. Geneva: World HealthOrganization;2013.

WorldHealthOrganization.GlobalactionframeworkforTBresearch.2015Geneva.

https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global-framework-research/en/. [Accessed18December2019].

WorldHealthOrganization.TheEndTBStrategy.2014Geneva.https://www.who. int/tb/strategy/en/.[Accessed26November2019].

WorldHealthOrganization.Guidelinesonthemanagementoflatenttuberculosis infection.Geneva:WHO;2017...[Accessed20December2019]http://www. who.int/tb/publications/ltbi_document_page/en/.

WHO.MoscowdeclarationtoEndTB.FirstWHOGlobalMinisterialConference Ending TBintheSustainable DevelopmentEra:AMultisectoralResponse Moscow,RussianFederation....[Accessed26November2019]https://www. who.int/tb/features_archive/Moscow_Declaration_to_End_TB_final_draf-t_ENGLISH.pdf.

WorldHealthOrganization.Public–privatemixfor TBprevention andcare:a roadmap.2018Geneva. https://www.who.int/tb/publications/2018/PPMRoad-map/en/.[Accessed18November2019].

WHO.Globaltuberculosisreport.2019...[Accessed22November2019]https:// www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/.

WorldHealthOrganizationUniversalHealthCoverage.WHO,Geneva,2019.https:// www.who.int/health-topics/universal-health-coverage#tab=tab_1. [Accessed 26November2019].

WorldHealthOrganizationUniversalHealthCoverage.UnitedNationalGeneral Assembly 23rd September 2019. https://www.who.int/news-room/events/ detail/2019/09/23/default-calendar/un-high-level-meeting-on-universal-health-coverage.[Accessed26November2019].

YaquobiF,BaderAlRawahi,NdukuNdunda,BadrAlAbri,AminaAlJardani,AliAl Maqbali,etal.Screeningmigrantsfromtuberculosishighendemiccountriesfor latentTBinalowendemicsetting.Submitted.

Zenner D, Hafezi H, PotterJ, Capone S,Matteelli A. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of screening migrants for active tuberculosis and latent tuberculousinfection.IntJTubercLungDis2017;21:965–76.

ZeroTBInitiative.https://www.zerotbinitiative.org/.[Accessed18December2019].

ZumlaA,PetersenE.Thehistoricand unprecedentedUnitedNationsGeneral AssemblyHighLevelMeetingonTuberculosis(UNGA-HLM-TB)—‘Unitedto EndTB:an urgent globalresponseto aglobal epidemic’.IntJ InfectDis 2018;75:118–20.