The integration of a

sustainable packaging

process in the supply

chain

The case of the French wine industry.

BACHELOR THESIS WITHIN: Supply Chain Management NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Business and Economics – Major in Business Administration AUTHORS: Olivia Hunter, Emilie Kumar

TUTOR: Gershon Kumeto JÖNKÖPING May 2021

Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Authors: Tutor: Date: Keywords:The integration of a sustainable packaging process in the supply chain. The case of the French wine industry.

Olivia Hunter & Emilie Kumar Gershon Kumeto

2021-05-24

Wine industry, Sustainability, Packaging, Supply Chain

Abstract

Background: With the rise of awareness of climate change, sustainable development has become a recurring topic in discussions concerning global development, the environment, and society. Packaging has long been a part of a ‘take-make-dispose’ linear model that has caused damage to our ecosystem and has led to the search for more sustainable alternatives. While literature relating to sustainable packaging processes exists, there is an absence of knowledge on which packaging processes are being applied, and how. Given that the French wine industry is prestigious and takes pride in tradition and quality, the question of transitioning to more sustainable packaging processes merits further research.

Purpose: The purpose of this paper is to study the gap between the range of sustainable packaging approaches that are theoretically suggested in the literature and the approaches that are practically applied within organisations by exploring how and why packaging processes are integrated into the supply chain, in the French wine industry.

Method: This research is qualitative and adopts the interpretivism paradigm. Primary data is collected through semi-structured interviews with players that occupy all the positions along the French wine industry’s packaging supply chain.

Conclusion: The findings show that sustainable packaging approaches are not being integrated into the supply chains in the French wine industry. (1) There are no realistic solutions available or track record to be followed. (2) The focus is still set on having clear economic benefits which the current sustainable packaging alternatives do not offer. (3) The long loop of circular economy is being used, which is based on recycling. (4) A need for collective awareness is needed, as well as a desire to change, for sustainable packaging processes to be integrated into the supply chain.

Acknowledgements

First of all, the authors would like to take the opportunity to thank all those who helped us through the writing of our thesis.

We wish to express our deepest appreciation for our tutor Gershon Kumeto for taking the time to guide and support us throughout the entire process. His feedback, experience, and knowledge were primordial to our study.

And finally, we would like to show our gratitude to the individuals who granted us their time to answer our questions in a sincere and involved manner. Their participation was an integral part of our thesis findings.

__________________ __________________ Olivia Hunter Emilie Kumar

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. Introduction ... 1

1.1. Background ... 1

1.2. Problem discussion ... 2

1.3. Purpose ... 3

1.4. Context of the study: the French wine industry ... 4

1.5. Research question ... 5

1.6. Method... 6

1.7. Contributions of the research... 6

1.8. Delimitation... 6

1.9. The Structure of the Report ... 7

2. Frame of reference ... 8

2.1. A broader view on Sustainable Packaging Design ... 9

2.2. The difficulty to implement sustainable packaging designs ... 13

2.3. Competitive advantage ... 15

2.4. Sustainable Packaging Logistics (SPL) and its approaches ... 16

3. Method... 20

3.1. Research philosophy: Scientific approach ... 20

3.2. Research approach ... 21

3.3. Theoretical approach ... 21

3.4. Research design: case studies ... 22

3.5. Case selection: Sampling method... 25

3.6. Data type & form... 26

3.7. Data collection tools and process ... 26

3.8. Ensuring trustworthiness and consistency during the Study ... 28

4. Empirical findings ... 30 4.1. La Cité du Vin ... 31 4.2. Smurfit Kappa ... 31 4.3. EFI Group ... 34 4.4. Mauco Cartex ... 37 4.5. Maubrac ... 40 4.6. Saverglass ... 43

4.7. Château Troplong Mondot ... 45

4.8. S.A.R.L François Villard ... 48

4.9. Cave Yves Cuilleron ... 50

4.10. SCEA Château Reillanne ... 53

4.11. MT Vins ... 56

5. Analysis ... 59

5.1. Packaging choices of the companies ... 59

5.2. The supply chain... 59

5.3. Sustainable packaging process ... 61

5.4. Key drivers for sustainable packaging ... 62

5.5. Challenges encountered in packaging design ... 63

6. Conclusions ... 65

7. Discussion ... 67

7.1. Implications for practice ... 67

7.2. Limitations of the study ... 67

7.3. Recommendations for future research ... 68

References ... 69

Appendices ... 76

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Since the industrial revolution of the 19th century, the shift from an agrarian and artisanal society, to a commercial and industrial one changed human activity, pushing the environmental state out of its equilibrium, with potentially catastrophic consequences for long-term social and economic development (Lenton, Rockström, Gaffney, Rahmstorf, Richardson, Steffen, & Shellnhuber, 2019) (Rockström, Steffen, Noone, Persson, Chapin III, & Lambin, 2009) (Steffen, Richardson, Rockström, Cornell, Fetzer, Bennett, ... Sörlin, 2015).

As a result of this human activity, we have gone beyond the safe and just space for humanity, with four of the nine planetary boundaries having been crossed: climate change, loss of biosphere integrity, land-system change, and altered biogeochemical cycles. The earth’s system has been driven into a new state due to two of these crossed boundaries being “core boundaries” (Steffen et al., 2015).

The term “sustainable development” is frequently cited in discussions concerning global development, the environment, and society. It is defined as the development that meets our present needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (Brundtland Commission, 1987).

In line with this interpretation of sustainable development, we need to switch from a linear economy of waste known as the “take-make-dispose” within an industrial system that relies largely on fossil fuels (Bocken, Bakker, & de Pauw, 2018) (Geissdoerfer, Morioka, De Carvalho, & Evans 2018), to a circular economy which is designed as a regenerative system where resource input and waste, emission, and energy leakage are minimised by slowing, narrowing and closing the resources loops (Geissdoerfer et al., 2018) (Geissdoerfer, Savaget, Bocken, & Erik Jan, 2017) (Kirchherr, Reike, & Hekkert, 2017) (Reike, Vermeulen, & Witjes, 2018). In order to transition to a circular economy, companies must smartly design and innovate their business models to increase the total value created rather than simply focusing on the revenue stream. The perspective of Triple

Bottom Line (TBL) claims that sustainable development has three dimensions, an economic, environmental, and social one. The TBL suggests that at the intersection of these dimensions are activities that positively affect the natural environment and society, and result in long‐term economic benefits and competitive advantages for the firm (Rezaei, Papakonstantinou, Tavasszy, Pesch, & Kana, 2018).

The implementation of sustainable supply chain management is being pressured as an important strategy to achieve a circular economy and sustainable development. This pressure is coming from the requirements of various stakeholders, governmental pressure (decrees, laws, norms/standards, etc.), environmental pressure (pollution, exhaustion of fossil fuels, etc.) and social/societal pressure (reputation/image, protection, etc.) (Morana, 2013). Sustainable supply chain management is defined by an organisation’s management of its materials, information, and capital flows. It is also the organisation’s internal and external cooperation along their supply chain while taking goals from all three dimensions of sustainable development (Seuring & Müller, 2008). Every year, five percent of global greenhouse gas emissions come from the estimated 11.2 billion tonnes of solid waste collected worldwide (UNEP, 2019). Therefore, one of the most important additions to a business model, to create a circular economy and a sustainable supply chain, is waste management. This includes the collection, transport, processing, recycling, or disposal, and monitoring of waste from its inception to its disposal. This helps to increase the total value created from materials as well as ensure that the supply chain loop is closed – from raw material extraction to waste disposal (Bacinschi, Zorica, Rizescu, Cristiana, Elena Valentina, Stoian, Necula, & Cezarina, 2010).

1.2. Problem discussion

There is a gap in the research between the range of sustainable packaging processes that are theoretically suggested in the literature and the processes that are practically applied within organisations.

In the literature, various sustainable packaging processes, tools and frameworks were theoretically suggested. Firstly, the Packaging Impact Quick Evaluation Tool (PIQET©) was proposed by the sustainable packaging alliance. It is a multi-criteria packaging evaluation and assessment tool that connects environmental impact with commercial performance (Sustainable Packaging Alliance, 2005). Then, Colwill et al. suggested the Suitable Balanced Scorecard methodology that allows for better guidance on a strategic and tactical level. (Colwill, Wright, & Rahimifard, 2012). Heller and Keoleian, recommended the most common analytical method, the Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), which evaluates the resource consumption and environmental impacts linked to a product, process, or activity. This method involves using key performance indicators such as a “weak” versus “strong” sustainability. (Heller & Keoleian, 2003). Lastly, the Sustainable Packaging Logistics (SPL) was constructed by García-Arca et al. and was proven to gain organisations competitive advantage based on three stages: structuring, deployment, and systematisation. SPL has shown to contribute to better results, in terms of environmental, economic, and social sustainability (García-Arca et al., 2014).

However, there is an absence of knowledge regarding the packaging processes that are currently being applied within organisations. Hence, through our research, we will aim to identify what packaging processes are being applied, as well as how and why.

The increase in public concern towards sustainability has brought to light the advantages of implementing sustainable packaging processes. However, there is an absence of knowledge concerning how companies are implementing them in their supply chains, to consider this growing concern, and ensure their supply chains remain competitive in their market.

1.3. Purpose

The purpose of this thesis is to study the gap stated above by exploring how and why the packaging processes are integrated into the supply chain, in the French wine industry. In practice this means that we will explore how the packaging processes are being managed from the origin of the materials used, to the design of the packaging, its manufacturing, transportation, use, right

up until its end of life. The aim of this study is to consider the sustainable aspect of the supply chain with regards to the packaging process.

1.4. Context of the study: the French wine industry

As a country striving to achieve zero single-use plastics in 2040 (French Ministry of the ecological transition, 2021), France is an interesting case study as its government has committed to making the steps to transition to a more circular economy at conventions such as the Paris Accords. In 2019, France passed a new piece of legislation declaring new goals in the realm of packaging for the year 2025. By the end of 2025, France aims to have a minimum of 65% (in weight) of all packaging waste recycled and should have a minimum of 70% (in weight) of all packaging waste recycled by the end of 2030. (European Union Law, 2020).

The vine and wine production industry is one France dominates with the highest dollar value worth of wine during 2019, generating eleven billion US dollars and representing 30.4% of total wine exports (ITC, 2019). In France, this industry induces huge amounts of waste and by-products each year with a total of 1.6 million tons of wood pruning, 850 000 tons of grape marc, 1.5 million hectolitres of wine lees and wastewater (La revue de vin de France, 2014).

In France, an average value for the country is submitted by the ADEME (Agency for the Environment and Energy Management). A French wine drinker consumes, on average, the equivalent of 58 bottles of wine (75cl bottles, i.e., 44 litres of wine), per year. The ADEME states that 1,500kg of CO2 eq. is emitted per tonne of wine produced, making the production of a 75cl bottle of French wine, packaged in a glass bottle, responsible for 1.1kg of CO2 eq. emissions. This value increases for fine wines and champagnes packaged in heavier bottles, as well as wines corked and over-corked differently. Considering the amount of wine drunk by an average French consumer (44L/ year), the production of this amount emits almost 64kg of CO2 eq, due to the quantity of water required throughout the production chain.

The search for packaging materials other than glass, or other forms of containers, is allegedly already underway by many vineyards due to the glass packaging accounting for nearly fifty percent of the current emissions.

Once bottled, the wine is transported to their point of sale. This step, according to the French Vine and Wine Institute, represents a large proportion of greenhouse gas emissions. It does however vary according to the volume of wine exported and the distance of the transportation to its point of sale.

Ultimately, once consumed, the recycling process can begin, or not (a glass bottle can take three to four millennia to decompose in nature). According to Eurostat and the European Federation of Glass Packaging, 73% of glass, including the consumed wine bottles, were recycled in 2013 within the European Union. This accounted for 7 million tonnes of CO2 saved.

With just under ten years left to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals set by the United Nations in 2015, the discussion on the topic of waste management is increasing (goal twelve, responsible production and consumption). In 2019, world leaders at the sustainable development goals summit called for a “Decade of Action” and a rapid rise in sustainable development. It was pledged to mobilise financing, enhance national implementation, and strengthen institutions so as to achieve the goals by 2030 (United Nations, 2015).

Despite the significance of this industry in France, there are currently no figures to be found on the extent of waste produced from wine packaging.

1.5. Research question

This research question will form the basis of our study, and its subsequent analysis aims to fulfil the purpose of the paper.

Research question 1: How and why are French wine companies integrating sustainable packaging processes within their supply chains?

1.6. Method

The research method is a qualitative study. We selected multiple companies in the French wine industry and conducted interviews with actors involved with the packaging process of their company. They played a crucial role in uncovering what packaging processes are being implemented, how they are being implemented, and the commonalities between the companies. The research we will be conducting will be exploratory as our research is conducted into a research problem and there is a lack of studies on this particular topic. We hope to bring to light whether sustainable packaging processes are actually being implemented in company supply chains, and how, through our interviews. The relevant literature will focus on topics such as “the supply chain”, “sustainability”, “circular economy” and “the wine industry”.

1.7. Contributions of the research

This research aims to unveil knowledge on how companies in the French wine industry are integrating sustainable packaging processes into their supply chains, and if they are not, we wish to examine why. In addition, this research seeks to present the approaches currently being used to facilitate the implementation of sustainable packaging processes, because in the current literature there is an absence of a clear framework.

1.8. Delimitation

Our research will focus on exploring how and why companies in the French wine industry are integrating sustainable packaging processes into their supply chains. However, we will be using a company perspective on the subject, and we will not be looking into the customer perspective. We

will not be looking for solutions on how they can better implement them, or which processes are more suitable than others. In this research, we will simply explore which packaging processes are being used in the companies and why they are currently used. We will also be looking at one particular industry which is the French wine industry. We will not be exploring the context of sustainable packaging processes in other countries as laws and standards may vary from one country to another.

1.9. The Structure of the Report

The structure of this thesis is composed of seven chapters. Chapter 1 consists of an introduction of the report. Our second chapter contains the literature review where we assessed the existing body of knowledge through four themes: sustainable packaging design, the difficulty to implement sustainable packaging designs, competitive advantage, and sustainable packaging logistics and its approaches. Within the third chapter, we incorporated our methodology. We defined our research philosophy, research approach, and theoretically approach. We go on to justify our choices of research design, case selection, data type and from, data collection tools and process, and how we ensured trustworthiness and consistency in our study. To end our thesis, we analysed, presented, and discussed our empirical findings, and concluded by giving a summary of what we found in relation to the research question we investigated. We recognised the implications of our findings and the limitations of our research to suggest future research.

2. Frame of reference

The frame of reference is structured as follows: An introduction will be given stating the definition and the broader view than can be appointed to sustainable packaging design. The issue when it comes to implementing sustainable packaging designs will be discussed, as well as the role of supply chain sustainability in increasing competitive advantage. The sustainable packaging logistics framework will be discussed to aid in the discussion of our research question.

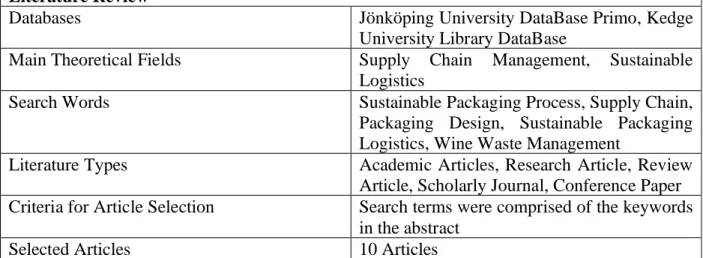

An overview of our literature review can be seen in Table 1 below.

Table 1 - Literature Review

Literature Review

Databases Jönköping University DataBase Primo, Kedge

University Library DataBase

Main Theoretical Fields Supply Chain Management, Sustainable Logistics

Search Words Sustainable Packaging Process, Supply Chain,

Packaging Design, Sustainable Packaging Logistics, Wine Waste Management

Literature Types Academic Articles, Research Article, Review

Article, Scholarly Journal, Conference Paper Criteria for Article Selection Search terms were comprised of the keywords

in the abstract

2.1. A broader view on Sustainable Packaging Design

Traditionally, the function of packaging is to protect the product to avoid generating losses along the supply chain to the final consumer (Williams, Wikström, & Löfgren, 2008). The urgency behind the packaging issue stems from a total of 150 million tons of plastic waste found in the ocean worldwide each year, of which 62% is packaging (Jambeck, Geyer, Wilcox, Siegler, Perryman, Andrady, Narayan, & Law, 2015). While plastics are not the only form of packaging that exist, complex waste management systems are needed to sort and collect the materials, as packaging materials may not be biodegradable or home compostable, and sometimes only fit for industrial composting (Davis & Song, 2006).

Packaging is a process that possesses three levels (as seen in Figure 1). The first is known as primary which is consumer packaging and has the aim of protecting the product. The secondary level refers to transport packaging, and “is designed to contain and group together several primary packages”. The tertiary level includes primary or secondary packages grouped together on a pallet or a road unit (Jönson, 2000).

There are three functions of packaging. Firstly, the marketing function goes through the process of selecting alternatives in graphic design and formats for adapting to legislation and customer demand. Furthermore, the logistics or flow function is structured to facilitate purchases, production, or packing and distribution. Thirdly, the environmental function is linked to reverse logistics (Johansson, 1997).

While Europe’s policies and measurements still focus on “recycling” rather than “reusing” or “reducing”, Switzerland and the Netherlands have been setting the example reaching close to 0% landfilling. However, on the other side of the spectrum lies countries like Bulgaria, Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Turkey who landfilled 80–100% of their municipal waste in 2013 (European Environment Agency, 2013). European policymakers struggle to support these countries that are lagging while also challenging frontrunners to fully close all the remaining loops with goals such as 75% recovery of all domestic waste, in 2020, and 90% of glass, in 2015 in the Netherlands. On the road to circularity and considering these national variations in policy, the average recovery and recycling rate for all forms of waste are equal to 46% in the period 2012–2014 (European Environment Agency, Schoenmakere, Gillabel, & Reichel, 2016a) (European Environment Agency, 2016b). Although recycling can be a valid treatment for some materials, it can lead to a ‘convenient stagnation’ on longer loops.

Different levels of loops exist and need to be closed to further the circular economy. The shortest loops involve four R-imperatives: refuse, reducing, reselling, or reusing, and repairing. Medium Long Loops embrace refurbishing, remanufacturing, and repurposing. The Long Loops include recycling materials, recovering (energy wise) and re-mining. (Reike et al., 2018).

The term “Bio” is subject to confusion as it refers to the nature of resources but also the material end-of-life. A lack of trust and greenwashing suspicions exist when it comes to packaging decision-making. A favourable EU regulation (European Parliament, 2017) has enabled innovation in the development of bioplastics from organic waste streams. The goal of this is to enter a circular concept through the development of bioplastics used for packaging. These new materials should be both adapted for food, in other words safe for human use and fully biodegradable. Nonetheless, convincing sustainable packaging materials are lacking (Guillard, Gaucel, Fornaciari, Angellier-Coussy, Buche, & Gontard, 2018). There is a need to find materials that will convert agricultural

and agri-food residues to naturally biodegradable solutions that are transparent in their eco-efficiency performance assessment. The rise of controversies such as greenwashing, ambiguous claims on environmental impacts, the high environmental cost, and the inconvenient compostability of PLA (Polylactic Acid, a thermoplastic polyester) has slowed down the growth of the growing market and consumer demand for bio-packaging solutions. It is very rare for small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) in Europe, which represent 90% of the EU food and packaging sector, to have a dedicated packaging manager, and the key decision-makers lack information and knowledge in this domain. To dominate in the sustainable food packaging market, SMEs should develop early guidance tools and reasoning using a user-driven strategy (Guillard et al., 2018).

Sustainable Supply Chain Management should look more broadly when it comes to optimising operations as it should integrate the pillars sustainability entails which include the environment, society, long-lasting economic benefits, and competitive advantage (Linton, Klassen, Jayaraman, 2007). Actors in the supply chain should manage and minimise risk factors on their path to sustainable development. The company should work towards full transparency in the public eye. This means sharing company operations with the general public and facing any appropriate consequences. Within the firm’s sustainable evolution, both strategic and organisational cultures should comply, coexist, and coevolve. These elements can be seen as criteria that a product should have in the context of sustainable development (Rezaei et al., 2018). As part of Wan Ahmad’s content analysis, criteria for sustainable packaging were identified and grouped into the three categories of the Triple Bottom Line concept: social, environmental, and economic criteria (Ahmad, De Brito, Rezaei, & Tavasszy, 2017).

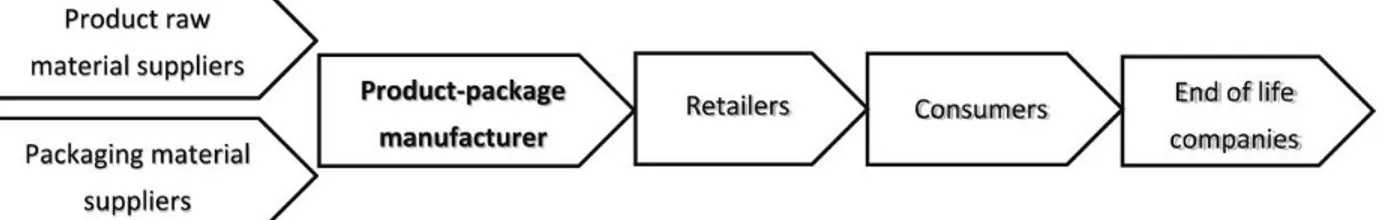

When defining the supply chain members in the food packaging industry, Heller et al. have set forth a sustainable supply chain management framework (as seen is Figure 2). The first members in this framework are product raw material suppliers and packaging material suppliers. The second actor in the supply chain is the product package manufacturer who is then connected to the retailers. The retailers reach out to consumers, and at the end of the supply chain come end of life companies who will manage the products R imperatives at the end of the product’s life cycle (Heller et al., 2003).

Figure 2 - Sustainable Supply Chain Management framework (Heller et al., 2003, p.88).

The Sustainable Packaging Alliance Australia (SPA) acknowledged the need to define the complexity of sustainable development, environmental policies, and environmental assessment protocols, for instance for Life Cycle Assessment. These elements should be translated “into practical tools for the diversity of skills and functions involved in packaging sustainability decision making” (James, Fitzpatrick, Lewis, & Sonneveld, 2005, p. 9).

As part of a definition of sustainable packaging, four principles have been identified, describing the characteristics a packaging should possess to be considered sustainable. The first pillar is “Effective”, it stands for packaging that effectively contains and protects a product along the entire Supply Chain, that informs the customer and encourages responsible consumption. By doing so, it should become an added value to society. The term “Efficient” was established through this definition. It relates to the efficient use of materials and energy throughout the product life cycle as well as with their support systems. It may be applied at the entire packaging system level. “Cyclic” is a concept illustrated by the unceasing cycling of packaging materials. It uses natural or industrial technical systems that keep the material at a high value by minimising degradation or by using upgrading additives. Another role packaging has is to be “Safe”, meaning it should not cause harm to human health nor to ecosystems, and users must be warned if unsure (James et al., 2005).

In the context of the Sustainable Packaging Alliance’s development of the Packaging Impact Quick Evaluation Tool (PIQET©), which would most likely be used by industrial professionals, SPA plans to create a multi-criteria packaging evaluation and assessment tool that connects environmental impact with commercial performance. The first step lies in proposing structural components to take into consideration. The first component is the product which should keep a

nutritional value with physical, chemical, or microbiological stability throughout its life cycle. Secondly, the packaging that contains the product should respect the four principles in the primary, secondary, and tertiary steps of its life. Furthermore, the ambient environment should be considered: the moisture, temperature, mechanical impacts, and oxygen. The last component which will impact all the above components is the macro-environment. This considers marketing, distribution, design, economics, environment, price level, communication, convenience, and legislation. (James et al., 2005)

When it comes to the food packaging industry, the evolution of packaging was generally driven by consumer demand which has led to sustainable packaging, an increase in the use of the packaging value chain relationships for competitive advantage, and the introduction of the evolving role of foodservice packaging. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), the most common analytical method, evaluates the resource consumption and environmental impacts linked to a product, process, or activity. This method may be illustrated by the US food system, where the life cycle of a product in the food industry is set in five stages: including the stakeholders that are involved in the supply, the manufacturing, and the distribution process of the product, and taking into account those affected by its commercialisation and ownership. This method involves using key performance indicators such as a “weak” versus “strong” sustainability (Heller & Keoleian, 2003).

2.2. The difficulty to implement sustainable packaging designs

With the increase of public concern regarding the amount of packaging waste going to landfill and into our oceans, global legislation has been implemented to promote producer responsibility. Companies have, for the most part, been responding to this global concern through minimising their packaging and ensuring its recyclability.

However, literature has called attention to packaging design and its ability to contribute to the reduction of environmental impacts by focusing on the entire supply chain and finding balance by considering all packaging aspects. The focus has started to shift, and companies and legislatures

are no longer simply looking at the direct impact of packing, considering only the production of the packaging material and the packaging’s end-of-life. Research has begun to shine light on the indirect influence and environmental impacts that packaging has along the entire supply chain. There is a gap in the research between the range of green packaging approaches that are theoretically suggested in the literature and the approaches that are practically applied within organisations. This gap stems from the fact that companies focus on the win-win approaches where there are clear economic benefits, in favour of those with no clear economic incentives, only environmental ones. “Sustainable packaging innovation will only succeed if it delivers a commercial benefit such as increased efficiency, cost reductions or increased sales” (Verghese & Lewis, 2010, p. 4397).

An analytical framework was proposed by Molina-Besch and Pålsson in 2015, underlining the need to divide the internal and external impacts of packaging into three types of impacts: product waste, logistics, and packaging material.

The literature pointed out that even when green packaging approaches are being implemented and all three packaging impacts are being considered by companies, the full range of theoretical improvement opportunities are not being carried out.

This is due to the lack of guidance and the rare literature that addresses how a company can overcome potential barriers, and efficiently and effectively fulfil all three pillars of the triple bottom line. The potential barriers that are affecting the ease of implementation of these approaches were defined by Molina-Besch et al. (2015). Administrative costs, production requirements, and purchasing requirements were all stated, but the three general barriers that influence all three impacts were the varying conditions in the supply chain, the lack of collaboration internally and externally along the supply chain, and marketing requirements. In order to give an example of the need for more adequate sustainable packaging design approaches, Rezaei et al. conducted a multi-criteria life cycle assessment on the Kraft Heinz company, in 2018. They followed the Best Worst method, which uses the decision-making tool, to define the best sustainable packaging design for three of Heinz’s products: Heinz tomato ketchup, Heinz seriously good mayonnaise, and Heinz beans. Nonetheless, even when considering

the triple bottom line, the results for the Heinz tomato ketchup bottle defined the PET bottle (Polyethylene terephthalate, aka a plastic bottle) to be a better option than the SOM bottle (Sauce– O–Mat, aka a high-quality sauce dispensing solution for front-of-house use).

On account of the absence of a clear business case, packaging approaches with environmental gains are being overlooked because economic benefits are the only benefits that are clear when evaluating choices. With a large amount of literature proving that economic goals are not always decisive, companies need to find a balance between economic, environmental, and social goals (the three pillars of sustainability) when considering the overall goal of their sustainability efforts. The potential and usefulness of packaging logistics is also evident in the literature, but its implementation and development are not clear (García-Arca, Prado-Prado, & A Trinidad Gonzalez-Portela, 2014). Packaging is “the process of planning, implementing and controlling the coordinated Packaging system of preparing goods for safe, secure, efficient and effective handling, transport, distribution, storage, retailing, consumption and recovery, reuse or disposal and related information combined with maximising consumer value, sales and hence profit” (Saghir, 2002). This definition allows packaging to have the ability to integrate a commercial, logistical, and environmental vision and allows for an increase in business competitiveness.

2.3. Competitive advantage

The importance for companies to have a competitive supply chain has solidified itself in view of the increasingly turbulent and volatile markets of today (Andersen & Skjoett-Larsen, 2009). The growing interest in supply chain sustainability goes hand in hand with a competitive advantage. When we think of competitive advantage we think of efficiency, and in the case of supply chains, we think of lean manufacturing. All activities that do not give added value should be eliminated (Moscoso, 2006).

There is a perception that extending sustainability to all the supply chain and promoting sustainable policies is incompatible with efficiency (Andersen & Skjoett-Larsen, 2009). Although, there is

indication through research that developing a sustainable supply chain could allow organisations to save on resources, reduce waste, and provide a competitive advantage (Carter & Rogers, 2008) (Seuring et al., 2008) (Pagell & Wu, 2009). Literature has also demonstrated that packaging has an important role to play in the different fields aimed at improving competitiveness. For example, packaging differentiates a brand or product from its competition through its tangible and intangible characteristics that its consumers value positively (Niemelä-Nyrhinen & Uusitalo, 2013) (Nilsson, Fagelund, & Körner, 2013) (Wang, 2013).

The application of the Suitable Balanced Scorecard methodology in a design support framework is suggested by Colwill et al., allowing better guidance on a strategic and tactical level (Colwill et al., 2012)

Garcia-Arca et al. suggest an approach called “sustainable packaging logistics” that has proven to gain organisations competitive advantage, and whose methodology is based on three stages: structuring, deployment, and systematisation. The deployment of these main pillars of sustainable packaging logistics has shown, through scientific evidence, that it contributes to better results, in terms of environmental, economic, and social sustainability.

2.4. Sustainable Packaging Logistics (SPL) and its approaches

When looking at packaging’s environmental impact, both direct logistics and reverse logistics must be dealt with. Direct logistics touch upon productive and logistics efficiency and are the “improvements in the act of supplying, packing, handling, storage, and transport for suppliers and packers to distributors and points of sale” (Saghir, 2002). Reverse logistics are concerned with the end of the supply chain and are defined by the reuse, recycling and/ or recovery of the product or its packaging.

Packaging logistics can integrate a commercial, logistical, and environmental vision of the integrity of the packaging’s impact. It is defined by “the process of planning, implementing, and controlling the coordinated packaging system of preparing goods for safe, secure, efficient, and

effective handling, transport, distribution, storage, retailing, consumption and recovery, reuse or disposal and related information combined with maximising consumer value, sales and hence profit” (Saghir, 2002). This definition of packaging logistics allows for an increase in business competitiveness.

García-Arca et al. adjusted Saghir’s approach to packaging logistics by proposing a new definition called sustainable packaging logistics. The idea behind being to incorporate the three pillars of sustainability. They define sustainable packaging logistics as “The process of designing, implementing, and controlling the integrated packaging, product and supply chain systems in order to prepare goods for safe, secure, efficient and effective handling, transport, distribution, storage, retailing, consumption, recovery, reuse or disposal, and related information, with a view to maximising social and consumer value, sales, and profit from a sustainable perspective, and on a continuous adaptation basis” (García-Arca et al., 2014, p. 330).

The new approach of sustainable packaging logistics was then based on four cornerstones, with each of these cornerstones needing to be addressed within each supplier’s structuring phase:

• Definition of design requirements, based on identifying the commercial, logistic, environmental, and protective needs under a sustainable perspective. In fact, the current competitive framework would recommend integrating all design requirements without overlooking any, while seeking consensus and prioritising the interests of all areas and companies along the supply chain.

• Definition of an organisational structure that integrates and coordinates all related areas along the supply chain, both internally in each company and externally, such as packaging manufacturers, distributors, third-party logistics, etc. This organisational structure would dynamically outline how to adapt the different views of design requirements at each stage on the supply chain at any time, and the measurement systems for assessing them. It would also outline how to adapt to the continuous changes in design.

• Definition of a system that measures the impact of a particular packaging proposal, while also comparing alternative designs in terms of material, dimensions, several units per pack, and aesthetic quality.

• Applying “best practices” and innovations in packaging design.

This framework is based on a methodology that contains three stages: structuring, deployment, and systemisation, and it helps organisations align their own business strategy with the strategy of their supply chains.

After implementing sustainable packaging logistics in an organisation, García-Arca et al. were able to prove that this approach did indeed contribute to a competitive advantage gain. The approach enables companies to establish a general framework that is adaptable and flexible, allowing each supplier to find packaging solutions within its borders that are economically, socially, and environmentally viable.

A paper was then written a few years later by García-Arca et al. aiming to establish further evidence on the important role of packaging in different fields aimed at improving competitiveness and including sustainability when dealt with at an integrated level. After sending out a questionnaire to seventy companies to validate the extent to which implementing the sustainable packaging logistics model contributes to improved sustainability, they were able to develop three scientifically viable results.

The first is on the importance of design requirements. Considering nine design requirements (commercial, protective, productive, logistic, p purchases, environmental, ergonomic, legal, and communication), commercial and communication requirements were shown to be the most important requirements as they highly consider the packaging’s visibility in the market.

Secondly, García-Arca et al. proved that companies that have implemented internal and external coordination mechanisms throughout the supply chain in packaging design achieve better results in sustainability.

And lastly, the extent of improvements and innovation towards packaging impacts a company's sustainability results. The more innovations, the greater the results.

Although increasing literature is calling attention to the clear economic, environmental, and social benefits of sustainable supply chains and green packaging, the approaches that must be implemented to achieve these benefits remain scarce. Through the literature studied, we believe

that the sustainable packaging logistics approach is the best option for companies looking to balance their economic, environmental, and social goals, all whilst ensuring economic and environmental benefits, and their competitive advantage in the market.

3. Method

3.1. Research philosophy: Scientific approach

In the context of social sciences, several scientific philosophies can be followed, such as positivism, realism, pragmatism, and interpretivism (Saunders, Lewis, & Thornhill, 2009). Positivism is a research philosophy that originated in the natural sciences. Positivists believe that sociologists should use quantitative methods with the aim of identifying and measuring social structures (Hacking, 1983). Positivism has received criticism because of its assumption that reality is singular, objective, and is not impacted by its investigation. (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Interpretivists have questioned this paradigm. Max Weber influenced this new philosophy by considering that ‘natural science’ and ‘social science’ are two different approaches requiring a different logic and different methods (Burger, 1982). Interpretivism argues that “unlike objects in nature, human beings can change their behaviour if they know they are being observed” (Collins, 1984). Therefore, they claim that when trying to understand social action, the researchers should look at the reasons and meanings behind this phenomenon. Other research philosophies exist that are positioned within the Positivism - Interpretivism spectrum (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Critical Realism considers the positivist philosophy when following logic and methods of natural sciences (Hartwig, 2007) (Hibberd, 2010). However, critical realists do not believe that observations can be separated from theories and claim that no form of science relies exclusively on observable empirical evidence (Hartwig, 2007). Pragmatism is a research philosophy that the research question should determine the research philosophy and that methods from more than one paradigm can be used in the same study (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

In our study, we will be adopting the interpretivism paradigm as we will be looking at the reasons and meanings behind the implementation, or not, of sustainable packaging processes in the supply chains of French wine companies, hence the how and why in our research question. In this case, considering social and natural science is key to our research. We will gain a more realistic view of

the situation by because these companies may have ulterior motives to how and why they do, or do not, implement sustainable packaging processes in their supply chains.

3.2. Research approach

Quantitative research and qualitative research are very different approaches to data gathering and analysis. Their aims are very different: qualitative research’s purpose is linked to theory initiation and theory building. However, quantitative research has the aim of theory testing and theory modification (Newman & Benz, 1998). Quantitative research uses design studies that involve collecting quantitative data, in other words, numerical data, and analyses it using statistical methods. On the other hand, qualitative research uses design studies that include collecting and analysing non-numerical data or qualitative data, and interpretative methods. Our approach to the research is qualitative as we gathered data using interpretive methods, through semi-structured interviews with companies in the French wine industry. This data can be qualified as qualitative as it entails a nominal gathering of data. The choice of conducting case studies is to have contextual relevance allowing us to obtain in-depth knowledge.

We will be using the qualitative research approach in order to capture expressive information, not conveyed in quantitative data about beliefs, values, feeling, and motivations that underlie behaviours (Berkwits & Inui, 1998).

3.3. Theoretical approach

There are three major processes of reasoning being discussed when performing research: inductive, deductive, and abductive reasoning (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

Our research will be developed through abductive reasoning. Abductive reasoning is important when there are many or an infinite number of possible explanations for a phenomenon, and the phenomenon cannot be explained by the existing range of theories. Abductive research entails making a probable conclusion from what you know, i.e., what the most likely inference can be made from a set of observations. (Collis & Hussey, 2014). In abduction the major assumption is evident however, the minor part of evidence is not known or hidden and therefore the conclusions are only probable (Håvard, 2014). Abductive research was chosen for our study because the research process of abductive reasoning is devoted to the explanation of the incomplete observations made, hence the “how” and the “why” in our research question.

The two other possible processes of reasoning for performing research were inductive and deductive.

Inductive research calls for observations of empirical reality, going from data to theory. It is the reverse of deductive research. It involves moving from individual particular observations of a specific and limited scope to general pattern observations (Collis & Hussey, 2014). The inductive method is mainly used to carry out scientific research, i.e., gathering evidence, seeking patterns, and inducing a hypothesis or theory to explain what is seen. It is a process of justifying hypothesis with empirical data (Håvard, 2014).

Deductive research uses observations, starting from theory and ending in data (Håvard, 2014). Deductive reasoning is used to clarify an already known and accepted fact. Deductive research is defined by being “a study in which a conceptual and theoretical structure is developed and then tested by empirical observations”, i.e., through the analysis of general to particular information (Collis & Hussey, 2014, p.7). Meaning, particular instances are deducted from general inferences.

3.4. Research design: case studies

Our research may be defined as exploratory because our research is conducted into a research problem and there are little to no earlier studies. This method is used in order to look at patterns

and ideas as well as develop a test hypothesis. We will be looking at the different patterns by conducting multiple case studies of different French wine companies with a research problem that will be tested throughout our research.

We would like to keep our research open and concentrate on gathering a wide range of data and impressions from qualitative case studies on companies in the French wine industry. Moreover, other typologies of research exist such as descriptive research which signifies research conducted to describe phenomena. It is more in-depth research into pertinent issues. Furthermore, research may also be analytical, in other words explanatory. It goes above descriptive research and explains why a certain phenomenon happens, thus aiming to understand the phenomena. Predictive research is in continuation with the analytical research and goes into forecasts of the likelihood of the repetition of this phenomena.

A case study is a methodology that is used to explore a single phenomenon in a natural setting using a variety of methods to obtain in-depth knowledge. Case studies can be useful as we are able to investigate a contemporary phenomenon in depth and within its real-life context, particularly when phenomenon and context boundaries are unclear. In the context of our study, we aim to explore sustainable packaging processes within the supply chain however the gap between theory and the reality of implementation of these processes is unclear, hence the use of case studies in this study. We will be conducting multiple case studies. The reason for this choice is that it gives a wider view of the French wine industry as multiple companies of different sizes, as well as different positions along the supply chain, will be studied. We can analyse the data within each situation and across different situations. We gain an understanding of the similarities and differences between the cases. The data gathered are strong and reliable. However, there are disadvantages to conducting multiple case studies. They are time-consuming and may lack in the richness of data as the research may be less in-depth. A case may be a particular business, group of workers, event, process, person, or another phenomenon (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

There are multiple case study typologies that exist. Descriptive case studies have the aim of describing current practices. Illustrative case studies attempt to illustrate new and possibly innovative practices implemented by particular companies. Experimental case studies have the objective of examining the difficulties of implementation of new procedures and techniques in an

organisation and evaluating the benefits. Explanatory case studies use existing theory to understand and explain what is happening (Collis & Hussey, 2014). We have conducted an illustrative case study as we will be looking to illustrate how and why companies are or are not implementing sustainable packaging processes within their supply chain.

We have conducted multiple case studies in the French wine industry to expand our body of knowledge making them comparative case studies. In order to select our case studies, we have chosen big and small actors in the industry, positioned all along the supply chain, with the aim of giving a fuller perspective of the industry and analysing the different behaviours throughout different sized companies who have different positions along the supply chain.

To conduct our case studies, we have followed the following steps:

1. Selecting the case: Our case studies will focus on companies in France and the wine industry. The similarity of these cases will help to show if our theory can be generalised. 2. Preliminary investigations: This process will help us become familiar with the context in

which we are going to conduct our research.

3. Data collection: We will use semi-structured interviews to collect our data.

4. Translation: As our interviews were conducted in French, we will subsequently translate our interviews to English.

5. Coding: We will code our data to identify concepts and findings. 6. Data analysis: We will conduct a cross-case analysis.

7. Writing the report: The structure of our report will be defined once we have collected and analysed our data. Since we are doing an interpretive study, we will extensively quote from the data we have collected adding diagrams and tables to better explain our findings.

3.5. Case selection: Sampling method

In an interpretive study, there is no statistical analysis, and we will not be looking at

generalizing a sample, in other words, a subset of a population, to the population. Thus, we will not be selecting a random sample. To avoid a lack of data, we have narrowed our sample to a specific location: France, as tradition and sustainability laws vary from one country to another. If we were to explore how and why sustainable packaging processes are implemented in different countries, we would need more time to investigate a larger number of companies. Although, we have chosen to analyse big and small actors in the French Wine Industry, along the entire packaging supply chain as it is important to give a broad view of the industry as a whole (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

We will be using the sampling method “Snowball sampling” and networking which occurs when studies consider the importance of including people with experience of the phenomenon. We have chosen this method as we understand that people have different roles in the company which may not at all be linked to packaging and their processes. We have prioritised contacts who are linked to operations management, marketing and communications management, sales, managing partners and founders (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

Other sampling methods exist such as fundamental or purposive sampling which is also linked to people who have experience in the phenomenon. However, the researcher decides before the survey and does not alter his sample after the data gathering has commenced. Natural sampling is used when the researcher has little influence on the composition of the sample (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

To obtain semi-structured interviews with the people of interest in this study, we worked on networking with our existing contacts. These existing contacts helped us gain the contacts of people within our sample. Other methods were used such as using Linked In with the aim of expanding our network and obtaining interviews with a few key players.

We have conducted nine case studies. We have mentioned the names of the respondents, as well as their roles, companies, and why they were selected in Table 2 (see part 3.7 below).

3.6. Data type & form

There are two sorts of data: primary data and secondary data (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

Primary data originates from an original source, such as your own experiments, surveys, interviews or focus groups. The interest in primary data is that the data gathered is tailored specifically to help the researcher answer the questions and research purpose of his study. The downsides however are the expense and time needed to collect it (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

Secondary data is collected from an existing source, such as publications, databases, and internal records. This category of data is convenient to gather as it is usually inexpensive and less time consuming. Nevertheless, the information that can be found will not be gathered with your research purpose in mind. This makes it less valid than primary data (Collis & Hussey, 2014).

Primary, qualitative data was used during the research of this thesis. This decision was made based on the specific research question and context of the study, the sensitive nature of the data needed to attain results, and the lack of secondary data available. The qualitative data allowed us to put emphasis on the quality and depth of our collected data, making it rich in detail and nuance. It allowed us to gather more in-depth explanations to our questions during the semi-structured interviews, helping us in the discussion section of our thesis.

3.7. Data collection tools and process

To collect the data needed to answer our research question, semi-structured interviews were conducted. To allow for a focused, conversational, two-way communication we kept an open framework. Although general interview questions were formulated ahead of time (see Appendix 1), some questions were further shaped during the interviews, allowing us and the respondents the flexibility to enquire for details and further discuss issues that seemed relevant to the study (Case,

1990). All companies were selected regarding their position in the French wine industry’s packaging supply chain.

Table 2 – Interview cases

Case and

respondent’s number Company name

Name Position Date of

interview Length of interview 1 La Cité du Vin – Fondation pour la culture et les civilisations du vin Aurélie Furderer Relations officer 17/03/2021 25 minutes

2 EFI Group Charles

Edouard Grimard

Sales director 09/04/2021 40 minutes

3 Château Troplong

Mondot

Claire Payen Marketing and communication manager

12/04/2021 27 minutes

4 Mauco Cartex Pierre

Rebeyrole Managing director 19/04/2021 50 minutes 5 S.A.R.L François Villard François Villard Vineyard owner 19/04/2021 45 minutes 6 Cave Yves Cuilleron Yves Cuilleron Vineyard owner 20/04/2021 45 minutes 7 Maubrac Vincent Paquet

Sales manager 21/04/2021 33 minutes

8 MT Vins Charlotte Fillaudeau Regional export manager 22/04/2021 31 minutes 9 SCEA Château Reillanne Benoît Ab Der Halden Chief operating officer 22/04/2021 26 minutes 10 Saverglass Alexandre Maret Export sales manager 27/04/2021 22 minutes

11 Smurfit Kappa Helene

Maillard

Sales manager 30/04/2021 24 minutes

Our interviews were conducted in French because all respondents were French. As authors, we are both bilingual in French and English, so we were able to efficiently translate all interview data to English. Once the translation was done, we moved on to the coding of our data.

We started by determining the coding units, i.e., particular themes identified in our data, and then we allocated them a specific code (Collis & Hussey, 2014.). At this point we were able to construct a coding frame, i.e., a list of coding units against which the analysed material is classified (Collis

& Hussey, 2014). The coding frame enabled us to identify the key concepts and findings, such as the patterns and differences, throughout the data (Gibbs, 2007).

3.8. Ensuring trustworthiness and consistency during the Study

In a qualitative research, trustworthiness refers to the degree of confidence in data, interpretation, and methods used to ensure the quality of a study (Elo, Kääriäinen, Kanste, Pölkki, Utriainen, & Kyngäs, 2014). It is outlined by four criteria credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability (Guba & Lincoln, 1982).

Credibility of the study is the most important criterion as it ensures confidence in the truth of the study (Elo et al., 2014). It is comparable to internal validity in quantitative research.

Our study was conducted using standard procedures, and we established credibility during our study through prolonged engagement with the respondents, persistent observation if appropriate to the study, debriefing and reflective journaling. We verified the accuracy of our data prior to data analysis.

Transferability is used to determine how applicable or useful the findings are to people in their own setting and situations (Elo et al., 2014). In quantitative research this is considered analogous to generalisation, however it is different from statistical generalisation.

For the duration of our qualitative research, we have ensured our focus is on the stories of our respondents. We do not consider that the stories told are applicable to everyone, to every company, in every country. The transferability of our study is supported by the detailed description given to the context of our study and the country in which it is being conducted.

Dependability concerns the stability of the data over time and over the conditions of the study (Elo et al., 2014). It is similar to reliability in quantitative research.

Throughout our study we have maintained an audit trail of all our interview recordings, debriefings, journaling, and notes to ensure a secure and relevant chronological record of our research. All data is being stored in our university OneDrive, to guarantee it is handled safely. When credibility, transferability, and dependability are established, confirmability is also established. Confirmability is the neutrality, or the degree findings are consistent and could be repeated (Elo et al., 2014). It is comparable to analogous to objectivity in quantitative research. In addition, to ensure the quality of our study, we remained neutral throughout when asking our questions, and leading the discussion, to not push the respondents towards any answers.

4. Empirical findings

The basis of our study was to explore how and why are French wine companies integrating sustainable packaging processes within their supply chains.

To do so, eleven semi-structured interviews (see table 2) were conducted with companies of various positions along the supply chain (see figure 3), in the French wine industry.

Figure 3 - The interviewed companies’ positions along the supply chain

The cases will be presented in order of their position along the supply chain. Furthermore, we have decided to present our findings through a within-case analysis, by using the themes of our interview guide as a structure. We will do the same for our analysis, allowing our reader to have a clear understanding of our research results and analysis. Therefore, our findings will the organised as followed:

1. Packaging choices 2. The supply chain

3. Sustainable packaging process

4. Key drivers for sustainable packaging 5. Challenges encountered in packaging design

4.1. La Cité du Vin

La Cité du Vin is a foundation and exhibition space for the culture and civilisation of wine, in Bordeaux, France.

The person interviewed was the relations officer.

We will not further discuss this interview in our results and analysis since the objective of this interview was simply to have a better understanding of the industry.

4.2. Smurfit Kappa

4.2.1. Company Profile

Smurfit Kappa is the leader in the paper-based packaging production industry and the largest manufacturer of corrugated cardboard and packaging cardboard in Europe. They stand out from the industry because they have their own wood procurement sites, paper mills, packaging production factories and recycling plants.

The person interviewed was the sales manager for packing in the French wine industry.

4.2.2. Packaging Choices

Smurfit Kappa produces a large array of types of packaging such as industrial, e-commerce, fashion, and wine bottle packaging, and use recycled paper and cardboard.

The reason for using recycled paper and cardboard is the environmental impact and the quality. Nevertheless, Smurfit Kappa have a sourcing program based on seven pillars that they consider when choosing the packaging options. These seven pillars are: quality, health and safety, business continuity, manufacturing, continuous improvement, service and technical support, environment, and sustainable development: “these seven pillars promote sustainable growth and help us find opportunities and synergies with our suppliers”.

They have a transparent supply chain and the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) label which certifies that they paper is made from responsibility sourced wood fiber.

4.2.3. The Supply Chain

They produce the raw materials and their packaging inhouse. The paper comes from their forestry resources and is transformed into paper in their paper mills. Cardboard is then produced from that paper and their packaging is created in their packaging production factories. The packaging is subsequently sold to the customer. Their recycling plants allow them to recycle their packaging and waste.

4.2.4. Sustainable Packaging Process

Smurfit Kappa considers their packaging process as 100% sustainable as their business model is a circular business model which allows them to integrate sustainability into every fiber. They have initiatives in place which involve sustainable sourcing of their raw materials as well as reducing the environmental footprint of their customers: "We replace the natural resources we need, use 75% recycled fiber in our products, and reuse materials whenever we can". They explained that they work with local organisations whenever they can. They also close the loop by partnering with other sectors. As for the wood needed to make the paper, they described forests as a closed loop.

In terms of innovation, the organisation has developed the “Smurfit Kappa Better Planet Packaging initiative”. This initiative has to do with the exploration of new opportunities in material efficiency, innovation, and reuse. Its goal is to “maintain our leadership position as the circular economy takes hold as the obvious model”.

The demand for sustainable packaging alternatives has affected Smurfit Kappa as their consumers are aware of their efforts of waste reduction.

4.2.5. Key Drivers for Sustainable Packaging

Over the years, Smurfit Kappa set goals for sustainability and are continuing to do so now. Between 2009 and 2013, the company reduced their landfill waste by 7.1%. From 2005 to 2019 32.9% of their fossil CO2 emissions from their paper and board mills were reduced. By the end of 2019, Smurfit Kappa sold 92.1% of their packaging under the label FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) which certifies a sustainable management of forests during the production of their products.

They have an extensive network of R&D centres, innovation centres and unique tools: “we can create customised, cost-effective, and sustainable packaging solutions for our customers”.

They ensure the total transparency of their supply chain by complying with the GRI G4 Comprehensive Sustainability Guidelines: “We have our sustainability data verified through an independent limited assurance process using GRI standards”. These guidelines allow them to achieve a sustainable packaging process.

4.2.6. Challenges encountered in Packaging Design

One of the key challenges in implementing sustainable packaging processes that respondent 11 identified was the rise of the price in raw materials, i.e., paper, which consequently increases the price of their packaging products. This has been an inconvenience for the company as well as their clients and end consumers. Smurfit Kappa recognised that their sustainable packaging processes gave them a competitive advantage as they are one of the very few in the wine industry.

4.3. EFI Group

4.3.1. Company Profile

EFI group are printers of adhesive labels and cardboard packaging, for the agri-food, wine and spirits, cosmetics, and electronic cigarettes industries.

The person interviewed was the sales director for the south-west region of France, whose responsibilities consist of managing a client portfolio and finding new clients.

4.3.2. Packaging Choices

As a printing company, EFI group uses cardboard and paper labels. Their choices of packaging are based on the client’s demand, however, depending on the size of their client’s company they can advise them on their packaging choices. For example, they have no say in the packaging choices of multinational companies, but they do advise the smaller companies.

When choosing their packaging, the environment needed for the product is considered. For example, the labels for rosé wine bottles must resist being submerged in ice cubes: the glue and paper used must be water resistant. Marketing is also taken into consideration.

The benefits they have from the use of these packaging materials are marketing benefits and environmental benefits. Their variety of types of packaging allow for customers to have choices when it comes to aesthetics (marketing benefits), as well as the choice of more sustainable options (environmental benefits), such as granular labels made from sugar canes, for example: “Our packaging choices are evolving thanks to the sustainable options being made available on the market”.

4.3.3. The Supply Chain

EFI group outsources their raw materials, i.e., coils of labels and plys of cardboard. They then print the labels and cardboards as demanded and sell them to their clients.