Big Brother is

Watching:

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 30 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Digital Business AUTHOR: Magdalena Kaminskaite & Samir Muzaiek JÖNKÖPING June 2021

Electronic Performance Monitoring in the

Knowledge-based Sector

i

Acknowledgments

"If a machine, a Terminator, can learn the value of human life, maybe we can, too.” Sarah Connor - Terminator 2: Judgment Day

We would like to express our gratitude to our tutor - Michał Zawadzki for guiding us through the challenging process of writing our thesis. Also, to the colleagues involved in providing us

with useful feedback throughout the way, helping us to maintain focused and critical. Furthermore, we would like to express our gratitude for the wonderful people who took their time to answer our extensive and challenging questions that allowed our research to become a reality. A big thank you goes to our friends and family that were extremely encouraging and

supportive throughout the whole process. Finally, we extend our gratitude to Covid-19 for making our lives miserable hell, the whole process stakingly painful, and opening the doors

for this research to happen.

ii

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Big Brother is Watching:Electronic Performance Monitoring in the Knowledge-based Sector

Authors: M. Kaminskaite & S. Muzaiek Tutor: Michal Zawadzki

Date: 2021-05-24

Key terms: Electronic Performance Monitoring, Knowledge-based Workers, Organizational Control, Privacy, Technology-mediated Control, Remote Work, Workplace Surveillance.

Abstract

In light of the global shift to remote work that was prompted by the Covid-19 pandemic - the relevance and use of Electronic Performance Monitoring (EPM) significantly escalated across all sectors. However, the most recent comprehensive literature review on the topic by Ravid et al. (2020) pointed out significant gaps in how EPM is perceived by knowledge-based employees. In line with those defined gaps, we raised two research questions, regarding what the perceptions of knowledge-based workers are towards the implementation and dissemination of EPM techniques, and whether the workplace context (home/office) has an effect on knowledge-based worker’s perceptions towards it. In this paper, we take a critical approach relying on a theory-based typology of EPM characteristics and build on the organizational control theory by elaborating on the technology-mediated control concept. We follow the constructivist grounded theory approach developed by Charmaz (2008) and the data was collected via 20 semi-structured interviews. The key findings of this research showed similarities as well as differences in how knowledge-based employees perceive EPM in contrast to other types of workforce. While overall the perceptions on EPM are negative, they can to some extent be alleviated by introducing a justifiable purpose, being transparent, allowing control over monitoring, and setting clear limits. Moreover, we provided insights into the perceptions of knowledge-based workers in response to EPM within the context of working from home. In such a context, knowledge-based workers show more resistance to EPM techniques and higher expectations of privacy, transparency, and appropriate data handling. Lastly, the authors provided avenues for further research including cross-cultural perspective, access to data, and ethicality and legality of EPM.

iii

Table of Contents

1.

Introduction ... 1

2.

Problem Discussion ... 3

3.

Research Purpose / Question... 5

4.

Literature Review ... 6

4.1 Knowledge-based workers ...6

4.2 Electronic Performance Monitoring (EPM)...7

4.2.1 Typology of EPM characteristics ...8

4.2.1.1 Purpose ... 8

4.2.1.2 Invasiveness... 9

4.2.1.3 Synchronicity ... 10

4.3 The role of EPM in organizations ... 12

4.4 Psychological and work design effects on EPM ... 12

4.5 Privacy ... 14

4.6 Legal / Ethical considerations of EPM ... 15

4.7 Critical theory ... 16

4.8 Electronic panopticon ... 17

4.9 Organizational Control ... 18

4.10 Strategies of Organizational Control ... 20

5.

Methodology... 22

5.1 Research Paradigm... 22

5.2 Research strategy ... 23

5.3 Data Collection & Sampling... 24

5.4 Data Analysis ... 25 5.5 Trustworthiness... 26 5.5.1 Credibility ... 26 5.5.2 Transferability ... 26 5.5.3 Dependability ... 26 5.5.4 Confirmability ... 27

5.6 Ethics and Confidentiality ... 27

6.

Empirical Data ... 28

6.1 Knowledge-based Worker Perceptions of EPM ... 29

6.1.1 Knowledge-based Worker Perceptions of the Purpose of EPM ... 29

6.1.2 Perceptions Regarding Invasiveness and Control ... 31

6.1.2.1 The Perimeter of Monitoring... 31

6.1.2.2 Control ... 34

6.1.2.3 Protection Measures ... 34

6.1.2.4 Scope of Monitoring ... 35

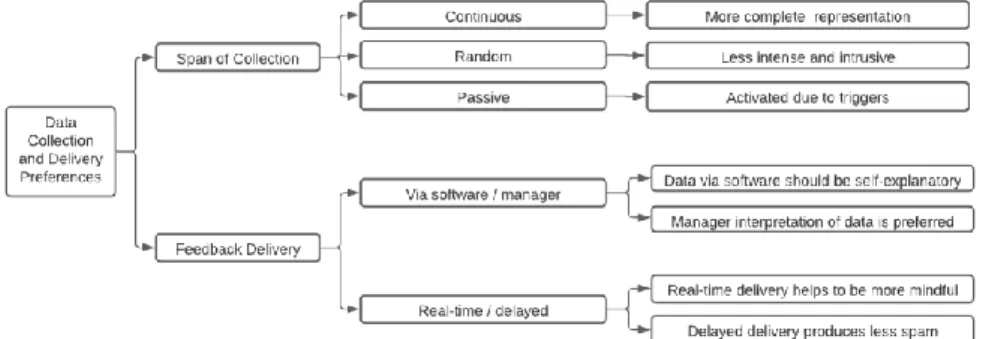

6.1.3 Data Collection and Delivery Preferences ... 36

6.1.3.1 Span of Collection ... 36

6.1.3.2 Feedback Delivery ... 36

6.1.4 Transparency over Data ... 38

6.1.4.1 Level of Communication and Knowledge ... 38

6.1.4.2 Access to Data ... 39

6.1.4.3 Data Ownership ... 40

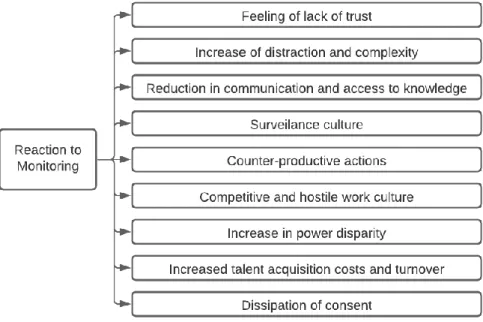

6.2 Reaction to Monitoring ... 41

6.3 Monitoring at Home ... 44

iv

6.3.2 Unorthodox working hours ... 48

6.3.3 The effect of working from home on EPM preferences ... 50

7.

Analysis and Discussion ... 52

7.1 EPM and knowledge-based workers ... 53

7.1.1 Access to Data ... 54

7.1.2 Data Collection ... 54

7.2 The Context of Working From Home... 55

7.3 Electronic Panopticon ... 56

7.4 EPM in the Context of Organizational Control... 57

7.5 Critical Points on the Dissemination of EMP ... 58

7.5.1 The Effect on Productivity ... 59

7.5.2 Informed consent and the future of consent... 59

7.5.3 Data security, Privacy, and the Risk of Cyber-espionage ... 61

7.5.4 EPM and Organizational Culture in the Context of Organizational Control 62 7.5.5 Fear of Exploitation ... 63

8.

Conclusion... 64

9.

Contributions ... 66

9.1 Theoretical Contribution ... 66 9.2 Managerial Contribution ... 6610.

Limitations ... 67

11.

Future Research ... 67

11.1 Cross-cultural perspective... 67 11.2 Access to data ... 6711.3 Ethicality and legality of EPM ... 68

11.4 Digital natives and digital immigrants ... 68

12.

Reference List ... 69

13.

Appendix ... 75

Appendix 1 ... 75

Appendix 2 ... 77

1

1. Introduction

____________________________________________________________________________________

In this section we will open with a general background on the context of the dissemination of EPM and the situation of the Covid-19 pandemic that led to the rapid adaptation.

______________________________________________________________________ In the late 2019, slightly over 5 percent of employees in the US worked remotely with regularity (Leonardi, 2021). However, with the Covid-19 pandemic spreading across the world over the last year, the governments issued strict safety-based regulations which made companies initiate a rapid and wholesale shift to remote work arrangements. This has been made possible by software that allows real-time text, audio, video and data sharing (Leonardi, 2021), therefore the providers of such services are experiencing unprecedented growth during the time. The video conferencing company Zoom has seen growth of 326% in 2020 and expects the sales to rise by 40% again in 2021 (BBC News, 2021). The business communication platform Microsoft Teams experienced a growth of 894% from March to June 2020 with the number of daily users skyrocketing since the beginning of the pandemic (Curry, 2021). Companies are sending their employees to work remotely indefinitely or sometimes even permanently like Twitter or Facebook. After the trial period that Covid-19 has offered, companies are seeing possible cost savings coming from remote work with a typical employer being able to save about $11,000 per year for every person who works remotely half the time (Berliner, 2020). However, drawbacks ranging from more difficult collaboration to the issues of loneliness and isolation (Berliner, 2020) are suggesting that although not always in full capacity, remote work is still here to stay.

Employee performance monitoring is embedded in the traditional business model based on the notion that employees are provided with a monetary reward in exchange for a service. This has been the norm for as long as we can remember labour as we know it, however since the emergence of the Covid-19 pandemic and a worldwide shift to working from home, the circumstances have significantly changed. With the majority of the population working from home, companies need to find new, innovative ways of monitoring, which have not yet been tested by time. Meanwhile, the current wave of industrial development is boosted by the proliferation of cyber-physical infrastructure and

2

interconnected systems that are making new practices of profiling, organizing and monitoring possible (Aloist & Gramano, 2019). Those vary from productivity to behavioural or even personal characteristics monitoring (Ball, 2010), utilizing the data collected from the devices used for work. Essentially, we have a new breed of elect ronic monitoring tools that are much more invasive than the traditional performance evaluation methods - collecting information that might go beyond the obvious (Montealegre & Cascio, 2017). In turn, neither the employers nor the employees are familiar wit h the methods or are sufficiently informed about the effects it may have on psychological wellbeing or work performance. What causes serious concerns in this situation is the distribution of power, with managers clearly holding the upper hand.

A Stanford study of 16,000 employees showed that working from home leads to a 13% increase in performance with improved work satisfaction and halved attrition rate (Bloom et al., 2015). However, employers remain worried (Routley, 2020) that productivity and focus might be diminished if people work in informal locations like home or a cafe. With the intention to maintain control over employees even during remote work, businesses turn to different service providers - companies that offer Electronic Performance Monitoring (EPM) software and hardware solutions. In essence, EPM captures employee behaviour and generates data that produces rich and permanent records which can be directly accessed by managers (Montealegre & Cascio, 2017). It may also target private behaviours and internal states - for example monitoring employee emails gives companies the ability to track their thoughts, feelings and attitudes that are originally meant to be private (Ravid et al., 2020). This might become a critical concern for individuals, as there is a possibility of non-work-related information being captured, especially when such people’s characteristics and physiology (i.e., biometric information like heart rate and body heat emissions) are concerned (Ravid et al., 2020). This type of moni toring is already in use in multiple sectors such as customer service and manual work, however due to the pandemic, a new group of employees are being introduced to this kind of work, more specifically knowledge-based workers. Knowledge based workers are characterized as being qualified and highly educated labour that conducts intellectual tasks (Alvesson, 2004) in a nonlinear fashion.

3

Different providers of such services offer unique levels of transparency towards the employees, ranging from access to all information gathered about them to not disclosing any details whatsoever regarding the data collected. Some monitoring software referred to as “invisible” even goes as far as to hide itself from the people that are being monitored (Cyphers & Gullo, 2020) by being designed to be difficult to detect and remove. While invisible software providers recommend it only to be installed on devices used for work, they still offer “silent” installation features that can implement the monitoring program remotely and without employee knowledge. At the same time, a lot of people use company owned laptops as their only computer, which might make the company monitoring ever-present (Cyphers & Gullo, 2020). The severity of the situation can be observed from the fact that most of the EPM providers in the market actually do offer the “invisible” feature that allows data collection without knowledge of the employee (Cyphers & Gullo, 2020). Further, according to Migliano (2020) as much as 38% of 26 analysed companies allow remote takeover, which apart from the invisible feature, also offers intrusive intervention/takeover without permission from the employee. Bossware goes as far as also providing keylogging, webcam and microphone activation settings, and screenshots and recordings of the work as reported in Appendix 1. However, the demand for employee monitoring tools since the pandemic surged by 87% in May of 2020, while the query “work from home monitoring tools” had increased by over 2,000% (Lynn, 2020). This goes to show that EPM has undoubtedly become more common, which goes hand in hand with the remote work looking set to stay for the foreseeable future (Migliano, 2020).

2. Problem Discussion

As the dissemination of monitoring techniques is continuously increasing, it becomes crucial for researchers and practitioners alike to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the effects that EPM has on workers worldwide. In their comprehensive literature review, Ravid et al. (2020) pointed out that there are multiple contradictions in the EPM literature, highlighting the multidimensional aspect of the phenomenon and the relevancy of contextual and psychological variables. These psychological variables stem from the nature of EPM, as in contrast to traditional monitoring, electronic monitoring captures detailed behaviour, generating rich, permanent records that are easily accessible, which may not be directly related to work performance; such characteris tics include

4

purpose, timing, target, intensity, scope, control, feedback delivery, transparency and clarity (Ravid et al., 2020). While EPM might improve the efficiency and quality of data collected in comparison to traditional performance monitoring (Jeske & Santuzzi, 2015), the effect on the individual remains vague. Furthermore, Ravid et al. (2020) highlight that the majority of studies within the field were conducted either on manual labour and service workers or for educational and training purposes, leaving some groups largely unexplored such as knowledge-based workers. Leading to the fact that work characteristics might play a key role in determining how individuals perceive EPM, concluding with the remark that the research on EPM characteristics is still in its early stages.

A new level of complexity has been added due to the Covid-19 pandemic, as the majority of companies worldwide have transitioned to remote work and increased their reliance on EPM. Firstly, the situation introduced knowledge-based workers to the underexplored phenomena of EPM on a notably wide scale. Secondly, a whole new context has been introduced, as there is no more geographical separation between work and private space anymore. This lack of separation between work and private space raises legitimate concerns regarding privacy and the scope of monitoring (Ravid et al., 2020). Furthermore, with many employees using their work computers and cellphones as their primary devices, the line between personal and work-related data becomes more vague (Ravid et al., 2020).

The confusion extends further to the managerial perspective as due to the physical distance that arose between them and their subordinates, managers feel the pressure to come up with novel solutions that allow them to keep an eye on their employees. Shook et al. (2018) stated that only 30% of leaders within companies that use novel technologies feel confident that the data is used in a responsible manner within their respective organization and 31% of business leaders are holding back from investing in EPM software due to concerns about what their employees think. However, the latest exposay by the Electronic Frontier Foundation shows the rapid increase of the EPM usage as well as the extent to which this software can access, and collect a vast and diverse amount of data without alerting the subject of the monitoring (Cyphers & Gullo, 2020). This is

5

happening despite the fact that researchers and managers alike are uncertain regarding the effect, implications and ramifications of the EPM usage.

Finally, regardless of the current situation surrounding the Covid-19 pandemic, the phenomena of remote work and EPM are here to stay, with companies worldwide already announcing their intentions of keeping a part of their workforce remote due to cost savings and other organizational benefits. In turn, EPM allows work to be easily outsourced and monitored as well as facilitates “at-will” employment relationships and the interchangeability of personnel (West & Bowman, 2016), making EPM a focal point for years to come.

3. Research Purpose / Question

This research aims to gain a better understanding of the perceptions and feelings of knowledge-based workers regarding the use of EPM technology in the workplace. We will be relying on the perspective of multidimensional characteristics of EPM developed by Ravid et al. (2020) instead of the traditional unitary phenomenon approach. Furthermore, this paper aims to explore the effect of the place of work (home/office) on knowledge-based worker’s views regarding the use of EPM technologies.

Therefore, this paper aims to answer the following questions:

Q1: What are the perceptions of knowledge-based workers towards the implementation and dissemination of EPM techniques?

Q2: Does the workplace context (home/office) have an effect on knowledge-based worker’s perceptions towards the implementation and dissemination of EPM techniques?

6

4. Literature Review

_____________________________________________________________________________________

In this section we will outline the theoretical background of the used concept of EPM and its characteristics. Furthermore, we are going to introduce the wider theoretical framework of organizational control, privacy and critical theory.

______________________________________________________________________ In order to find relevant content about Electronic Performance Monitoring, privacy concerns, and privacy protection policies, the first literature review was performed using the Web of Science database, the Jönköping University Library, and Google Scholar as sources for information. This search aimed to find research papers containing the combination of one or more of the following terms: electronic monitoring, performance monitoring, electronic performance monitoring, workplace surveillance, workplace monitoring, remote work monitoring, computer monitoring, electronic surveillance, privacy, and workplace monitoring policy. We also cross-checked results with references from key articles and added relevant keywords that appeared in the results. As an output of this preliminary search, the need of targeting the term “Electronic Performance Monitoring” was identified in order to get more accurate results in the line of the scope of this study. As part of an advanced search targeting the aforementioned terms, researchers managed to examine over 30 peer-reviewed articles.

4.1 Knowledge-based workers

Before delving into the EPM literature, it is important to more specifically point out the focus of our research - knowledge-based employees. With plentiful research done on manual and service workers in regard to EPM, the knowledge-based workforce is lacking (Holland et al., 2015; Ravid et al., 2020). Knowledge based workers are characterized as being qualified and highly educated labour that conducts intellectual tasks (Alvesson, 2004). Their work is characterized as processing of non-routine problems that require a non-linear and creative thinking (Reinhardt et al., 2011).

7

4.2 Electronic Performance Monitoring (EPM)

EPM systems are electronic technologies that are used to observe, record, and analyse information about employee performance (Ravid et al., 2020; Bhave, 2014; Stanton, 2000). EPM has a number of features that distinguish it on a psychological level from traditional monitoring, which are respectively the ability to track individual employees continuously, randomly, or intermittently; discreetly or intrusively; and with or without warning or consent (Ravid et al., 2020; Ajunwa et al., 2017; Stanton, 2000). It allows voluminous data within multiple dimensions to be recorded (Stanton, 2000) which can then be quickly accessed by managers and may or may not be directly related to employee performance (Montealegre & Cascio, 2017). Such technology has significantly changed the way supervisors monitor their employees in a shift from traditional observations to quantitative methods that provide broader and more easily comprehensible assessments of individuals (Bhave, 2014).

In contrast to traditional monitoring, EPM allows for the data to be collected incidentally and continuously, and with little concern for its ultimate purpose due to its low cost, the ability to scale, and its inherent ambiguity (Ravid et al., 2020). This opens the door for the data that are collected by EPM to be vast and diverse but also ambiguous, from both an interpretability and an ethical standpoint, compared to data collected using traditional monitoring (West & Bowman, 2016).

Although employees have essentially always expected their performance to be monitored, EPM stretches the possibilities by accessing internal states and private behaviours. For example - tracking employee thoughts, feelings, and attitudes by analysing their emails or social networks and relationships both inside and outside the company via social media (Ravid et al., 2020). Most recent EPM technology even allows the tracking of employee physiological states via biometric information like heart rate or body heat emissions (Ravid et al., 2020). The broad range of different techniques has been categorized by Ball (2010) as ones that measure productivity, behaviours, and personal characteristics, as seen in Figure 1. Ball refers to both surveillance and monitoring as similar practices, only with different audiences which splits the research in an unhelpful way. Ball (2010) chooses to refer to surveillance in the politically neutral way, which goes in line with the concept of

8

monitoring. These techniques might include recording telephone conversations, monitoring visited websites, use of video cameras, monitoring email contents, location tracking, internet blocking software (Holland et al., 2015), and more.

Figure 1: Adapted from Ball (2010). Workplace Surveillance: An Overview.

4.2.1 Typology of EPM characteristics

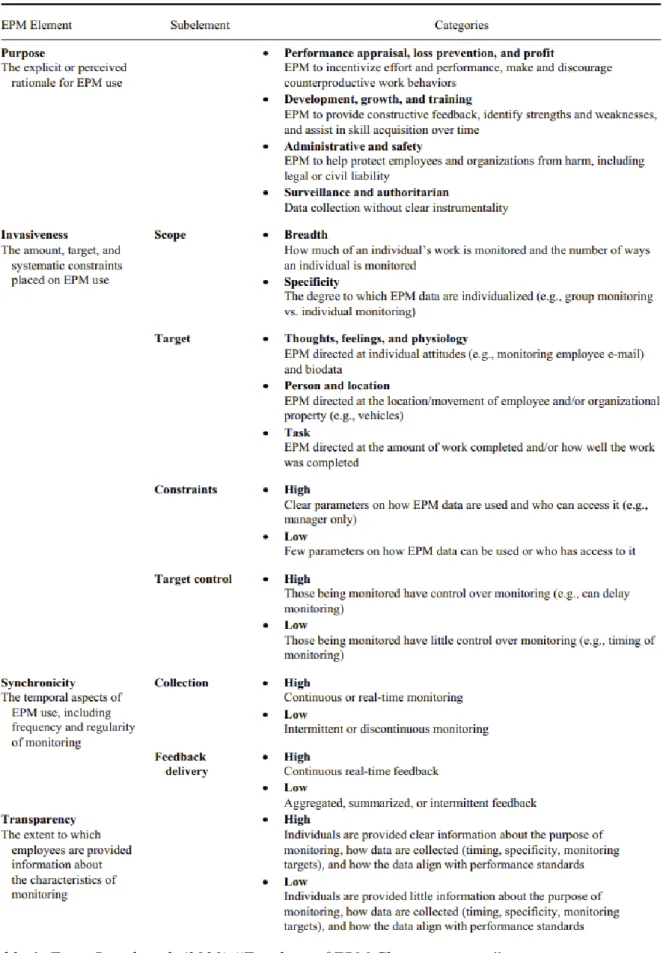

The early EPM studies reached conflicting results regarding the effect of the use of EPM, and this inconclusiveness was attributed to the scholars' dichotomous approach (present or absent) towards EPM studies (Ravid et al., 2020). However, in the last two decades, scholars have increasingly moved toward a more precise exploration of the effects of EPM psychological characteristics which has been organized in a psychology-focused typology of EPM characteristics by Ravid et al., (2020) as shown in Table 1.

4.2.1.1 Purpose

The purpose element refers to the rationale behind the use of EPM, what the company values and expects from their employees (Jeske & Kapasi, 2018). The element is split into four categories - performance, development, admin & safety, and surveillance & authoritarian control. Performance stands for the performance appraisal, loss prevention and profit, or in other words - holding people accountable for their actions. It is directed towards incentivizing effort and performance, done by employee comparisons and prevention of counterproductive behaviours like theft or loafing (Ravid et al., 2020). Development EPM then consists of development, growth and training and in contrast to employee comparison purposes, it is used for individual (within-person) comparison.

9

That is to identify the strengths and weaknesses of individuals and provide constructive feedback, which later leads to skill acquisition and performance improvement (Ambrose & Alder, 2000; Thompson et al., 2009). Admin and safety EPM protects both the company and the employees from harm regarding legal and civil liability. This type of EPM aids the safety, protection and wellbeing of everyone within the organization, by for example using recordings to protect from unjustified customer complaints. Another aspect included in admin and safety EPM is monitoring for environmental and sustainability purposes, i.e., energy consumption efficiency. The final purpose of surveillance is referred to as surveillance and authoritarian which is essentially conducted with no explicit reasoning beyond simply collecting information (Alder, Ambrose & Noral, 2006). This type of surveillance (monitor just to monitor) is found to directly elicit negative outcomes as people are expecting at least some rationale or purpose for EPM (Ravid et al., 2020).

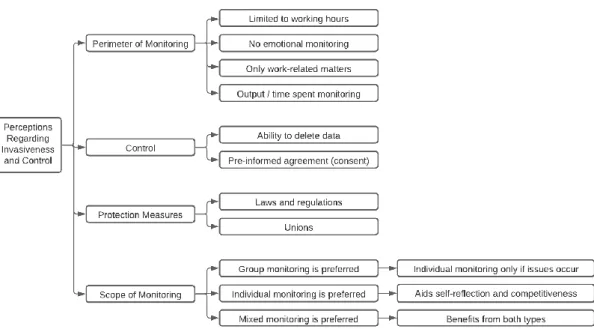

4.2.1.2 Invasiveness

The invasiveness element is about the intrusion of privacy, autonomy that employees have and their sense of personal boundaries. It is directly affected by the extent of EPM use, its target and the existing system constraints, for example long-duration monitoring is more invasive than short-duration as it restricts individual freedom and autonomy (Gagné & Bhave, 2011). It is divided into four categories - scope, target, monitoring constraints and employee control. The scope is about the breadth of monitoring (different ways in which monitoring can take place) and specificity or the extent to which the data is individualized to a specific employee (Ravid et al., 2020). The target can be thoughts, feelings and physiology, for example biometric monitoring or monitoring of social media profiles or email contents to learn about the individual. It can also be the body or location, which includes video camera monitoring or GPS monitoring to tell the exact location of employees at any point. The final target might be task or behaviour monitoring, for example computer monitoring related to keystrokes or outputs (Ravid et al., 2020). Different targets are perceived differently by the employees, with visible preferences of task focused monitoring over person-focused one that might go as far as looking into people’s chat history (Jeske & Santuzzi, 2015). The constraints are about the limits of when and how the data can be collected, how it is going to be used and who will be able

10

to access it when it is collected. The more explicit the constraints, the more clear the purpose of EPM which in turn mitigates the negative reactions to monitoring (Ravid et al., 2020). The target control is concerned with the control that the monitored employees have over the methods, timing and feedback, for example the ability to turn monitoring on and off manually.

4.2.1.3 Synchronicity

Synchronicity is about the time related characteristics of EPM use that are influencing the learning and behavioural response. The time when individuals are monitored (collection) or when the feedback is received (feedback delivery) affects their reactions to EPM (Ravid et al., 2020). Regarding collection, data can be collected either continuously or intermittently, however neither prove to be increasing performance more than the other (Watson et al., 2013). However, when it comes to attitudes, people prefer continuous and predictable EPM over intermittent and unpredictable ones (Jeske & Santuzzi, 2015). Finally, the feedback delivery refers to when the feedback is delivered timewise, for example real-time consistent delivery or summarized delivery upon completion.

4.1.1.4. Transparency

Transparency is the extent to which employees are informed about the monitoring characteristics. Here the organizational honesty is key when influencing employee attitudes and perceptions of fairness within the workplace (Ravid et al., 2020). Meaning that better explanation of the characteristics of EPM allows individuals to determine whether they assume the monitoring to be fair or not. As well as that, higher transparency leads to better job performance with improved perceptions of informational justice and trust in management (McNall & Roch, 2009).

11

12 4.3 The role of EPM in organizations

Organizations and monitoring go hand in hand whether it is social or technological surveillance (Ball, 2010). It is directly beneficial for companies as it helps to efficiently restock supplies, fairly distribute or incentivize employees, and prevent discriminatory activities (Kaupins & Coco, 2017) just to name a few. Apart from maintaining productivity and resource usage, a significant factor is the protection of corporate interests and trade secrets coupled with protecting the company from legal liabilities (Ball, 2010). However, a common ground in the research regarding EPM is that it has to be implemented carefully to make sure that the productivity does not get negatively affected. Alder (2001) raises the question of the necessity of EPM in the first place as often companies have strong organizational cultures with already sufficient levels of productivity. Introducing EPM to such an environment brings in the risk of negative attitudinal and behavioural reactions, in which case it is better to refrain from such technology altogether (Alder, 2001). Apart from all of the previous concerns and benefits of both parties, it has been observed that surveillance is moving away from the authoritarian regime and instead holds a more participatory character (Ajunwa et al., 2017). Employees are expected to use productivity applications and wellness programmes that are more beneficial for their own interests as well as the employers. Together with appropriate judgement and decision making of the supervisor implementing EPM measures (Bhave, 2014) it becomes a useful and powerful tool of the future.

4.4 Psychological and work design effects on EPM

EPM tools such as e-mail monitoring have shown negative effects on employee job satisfaction, stress and trust overall (Smith & Tobak, 2009). Meanwhile, extensive employee behaviour monitoring has been argued to create negative psychological states in employees, making the firms a less stimulating place to work in (Bolderdijk et al., 2013; Smith & Tabak, 2009; Thompson et al. 2009; Zweig & Webster, 2002). The primary concerns on employee monitoring are that it is unfair and abusive, it is unnecessarily infringing employee rights, and it creates an atmosphere of mistrust (Alder et al., 2006). In turn it has a negative effect on employee morale, increases stress levels and engenders negative job attitudes (Kemper, 2000). From an ethical point of view, if

13

employees are not notified about surveillance, it might not only violate their privacy but also promote a discriminatory environment (Kaupins & Coco, 2017; Wohlsetter, 2016) as making assumptions and acting upon them may result in employees fired without a cause (Kaupins & Coco, 2017).

According to Jeske & Santuzzi (2015), while general surveillance normally manages security and other risks, EPM focuses specifically on the performance and productivity behaviours of employees. Close monitoring therefore also evokes the feeling of higher workload, loss of control over work activities thus creating an intense work environment (Lyon, 2001; Aiello & Kolb, 1995; Smith et al., 1981). Depending how it is implemented, EPM may restrict the employee’s actions by setting certain limitations on their interaction with others, restricting movement between workstations and access to information (Jeske & Santuzzi, 2015). In turn such restrictions negatively affect the organizational citizenship behaviours (OCBs) which include pro-social behaviour and participation in social exchanges (Jeske & Santuzzi, 2015). For example, by using chat monitoring organizations might limit the OCB activities among employees and in turn harm the development and maintenance of interpersonal relationships at work (Lam & Lau, 2012). Lesser engagement in OCBs then leads to negative effects on performance, workplace relationships and work environment (Jeske & Santuzzi, 2015).

The logical underlying reason for an employer to implement EPM software at all is to be able to maintain strategic goals of the company. However, as we can see, workplace situations that affect the attitudes and perceptions of control in a negative way can have severe consequences for employee morale, turnover and personnel costs (Rafnsdóttir & Gudmundsdottir, 2011). According to Jeske & Santuzzi (2015) the influential variables that affect the extent to which the employees can support said goals which are directly influenced by EPM - job satisfaction, affective commitment, OCB and perceptions of control.

Holland et al. (2015) found that electronic monitoring software is negatively related to overall trust in management and the more widely a company uses such software the more likely employees are to report their employers are deceptive. Employees in manual jobs also have a lower perception that management could be trusted in making sensible or

14

competent decisions for their workplace. The findings of Holland et al. (2015) are connected only to manual workers as no such relationship has been found for people in non-manual jobs. These negative effects depend on the implementation decisions and the extent of monitoring mechanisms (Holland et al., 2015).

4.5 Privacy

Privacy is defined as the extent to which individuals perceive having cont rol over their personal information (Alge, 2001), while privacy invasion is the breach of that control (Ravid et al., 2020). Because employees use company hardware, operate in organizational facilities and work for the organizational purposes, their rights to privacy were assumed to be minimal (Kidwell & Sprague, 2009). However, with EPM making monitoring much more invasive and the geographical separation between work and home becoming more vague, the logical question of what are the boundaries of acceptable monitoring is being drawn (Ravid et al., 2020).

Privacy concerns are the individual’s beliefs regarding the risks and potential negative consequences associated with sharing of information (Cho, Lee & Chung, 2010; Zhou & Li, 2014). It is frequently utilized as the predictor of privacy management, however it has been observed (Taddei & Contena, 2013) that an individuals’ concerns regarding privacy do not necessarily reflect the privacy management choices that they make (Baruh et al., 2017). This is commonly referred to as the “privacy paradox”. Another framework commonly utilized in privacy research is the communication privacy management theory by Petronio (2002). His theory argues that privacy should not be considered as establishing a maximum boundary to keep others out, but instead as a negotiation bet ween accessibility and retreat (Baruh et al., 2017). In this dynamic privacy management process, individuals use strategic privacy rules to control said boundaries.

Privacy is a universal human need (Westin, 1967) however when people are uncertain about their preferences, they look for guidance in the environment (Acquisti et al., 2015) or in other words - context. Context dependence essentially means that individuals exhibit different responses ranging from extreme concern to apathy depending on the situation (Acquisti et al., 2015). A good example to explain this is how we only tend to share our

15

secrets with our closest friends, but sometimes we end up sharing all this information with someone we just met on a train. The researchers are therefore concerned about the ability of individuals to manage their privacy amid the increasingly complex trade-offs (Solove, 2013), they claim that traditional rules like choice and consent no longer provide adequate protection. In order to adequately protect privacy, we need policies that require a minimal amount of information and rational decision making from the perspective of an individual (Acquisti et al., 2015), all to protect them from the emerging unpredictable complexities of the information age.

4.6 Legal / Ethical considerations of EPM

While some studies found that monitoring is related to heightened levels of stress and might be contributing to employee health problems, what raises the most concern and criticism stems from the invasion of privacy (McNall & Stanton, 2011). From a legal point of view, EPM holds a lot of uncertainties as protection of worker’s rights is a human’s rights issue both due to dignity rights as well as privacy invasions (Ajunwa et al., 2017). There have been rapid technological innovations that allow the scrutinization and surveillance of workers, but little innovation in the field of privacy protection of workers (Ajunwa et al., 2017). Due to the lack of legal protection that limits the level of surveillance or its intrusiveness, the employees find themselves unprotected and without an easy solution to the issue. Employees are put into a position where their privacy becomes an economic good that can be exchanged for employment (Ajunwa et al., 2017) which is not yet appropriately protected by law. While gender or any other kind of discrimination has clear laws preventing it, employee privacy remains an unresolved issue. The reason for it is because the technological advancements have outpaced law and regulatory constricts and we currently are still in need of stronger regulations (Acquisti et al., 2015).

Some data-protection jurisdictions like the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) are making attempts in tackling this issue. Due to its modern approach, GDPR serves as an example for legal institutions attempting to keep up with the technological advancements through the so-called “Brussels effect”. The EU is exercising its global power via legal standards, sanctions and institutions and in this way

16

exporting influence to the rest of the world (Aloisi & Gramano, 2019). Consequently the “unilateral regulatory globalization” even reluctant market participants adapt to this set of measures which results in international convergence of “Europeanization” (Aloisi & Gramano, 2019). GDPR essentially ensures that employees are adequately informed about collection and processing of their data, that they have the right for their data to be forgotten and more (Citizens Information Board, 2021). In Art. 88 of the GDPR (2016/679) it is stated that the member states may “by law or by collective agreements, provide for more specific rules to ensure the protection of the rights and freedoms in respect to the processing of employees’ personal data in the employment context”. However, even though employees are informed about being monitored and have the right to ask for their data, employee privacy is not entirely protected. Cyphers & Gullo (2020) point out that workers might not be aware of the scope of monitoring, the transparency of the employer regarding the use of data, or not be comfortable with being monitored altogether. This in connection to the fact we are currently experiencing record unemployment rates puts employees in a position to choose between invasive and excessive monitoring or unemployment (Cyphers & Gullo, 2020).

4.7 Critical theory

The term “critical”, no matter how theory or practice is aligned, encourages us to go beyond ourselves and our tools and be unafraid of revisiting taken-for-granted assumptions and challenging our own normative values (Harvey, 2018). Critical thinking as introduced by Glasser (1972) is a thoughtful consideration of problems and subjects of a person's experience, it uses logical inquiry and reasoning to challenge, reflect on and revise the foundation of contribution. This research goes in line with critical thinking as we find great interest in looking at the transition from traditional to more advanced means of monitoring and how this affects the way of work within companies. The existing literature regarding effects of EPM already presents contradictory findings, suggesting that the results could be subjected to influence of culture and social positioning on beliefs and actions (Alvesson & Deetz, 2000). Therefore, we approach our research by identifying and challenging the assumptions of ordinary ways for perceiving, conceiving, and acting (Alvesson & Deetz, 2000) when it comes to employee monitoring techniques and effects on knowledge-based employees.

17

Critical theorists have distinguished themselves for a long time from other social theorists because they seek to combine moral philosophy with the social sciences (Munir, 2019). According to them, this approach permits their enterprise to be practical in a distinctively moral sense, rather than an instrumental one. Critical theory itself has a two-fold meaning - it is a school of thought and it also refers to a self-conscious critique that is aimed at emancipation through enlightenment and does not “dogmatically cling” to its own doctrinal assumptions (Giroux, 1983). Critical theory is about making the distinction between subjectivity and objectivity as well as what is and what should be (Carr, 2005). Benson (1977) captured the dialectic optic on the world that critical theory has, further calling to view organizations through this lense in 1997. He based this view on the fact that much organizational thought lacks a processual perspective that focuses on dimension. Benson’s (1997) dialectical analysis is based on 4 fundamental premises or principles - people are continually in a process of constructing and reconstructing the social context; social phenomenon need to be studied in a rational manner as a part of a larger whole that has multiple connections; social arrangements are constructions with latent possibilities of transformation that emerge through inherent contradictions in the social orders; and there is a commitment to praxis, while the limits and potentials of social arrangements are recognized. In order to view organizations through the optic of dialectics, managers need to adopt a different orientation towards their work (Carr, 2005).

4.8 Electronic panopticon

Any kind of performance monitoring impacts a workplace, and a good analogy to better grasp the topic is Benthem’s panopticon prison in which a central tower could have vision of all the cells. The panopticon effect was further examined by Foucault, who saw it as an example of discipline at work and the best way of management (Danaher et al., 2000). This is because the surveilled individuals feel under constant authoritative watch and therefore manage their own behaviours (Bauman & Lyon, 2013). The perception of being surveilled alone can be powerful enough for a manager to potentially impact an individual. However, other scholars argue that in the context of a workplace, close monitoring and surveillance is the result of a lack of trust between managers and

18

employees. (Holland et al., 2015). Such a point of view developed even further with implementation of electronic monitoring software as the monitoring has become much more intense, continuous and unrelenting (Holland et al., 2015).

McNall and Stanton (2011) stress the importance of giving employees a sense of control over the monitoring and providing them with surveillance-free spaces. They add on the usefulness of explaining the monitoring policies and their specifications ( i.e., how they can be turned off and on) to give employees reasonable expectations. Employees cannot perceive the surveillance devices as a tool to control their behaviour as it harms their intrinsic motivation; instead organizations should carefully communicate and implement monitoring policies in a transparent manner (McNall & Stanton, 2011). Giving the employees an option to turn the surveillance off by themselves fosters higher monitoring fairness perceptions via lower privacy invasion perceptions (McNall & Stanton, 2011).

4.9 Organizational Control

Organizational control is a communicative activity which consists of verbal and physical actions that are designed to overcome resistance and exercise control (Glossett, 2012). It is essentially about how organizations convince their members to act in the best interest of the system, instead of themselves (Glossett, 2006). Scholars in the field look into the organizational control processes to better comprehend which strategies and resources managers draw upon when convincing their subordinates to work together (Glossett, 2012). However, a complicating factor is that leaders and their subordinates have competing interests that stem from the fact that managers want to achieve the highest productivity under the lowest costs, whilst the subordinates want to achieve the highest gain with the lowest effort. Through the negotiation delving from respective interests, the actors create, reproduce and transform the particular organizational context (Glossett, 2012).

Tompkins & Cheney (1985) suggest a 3-part framework of organizational control from the communication perspective. The first step is the direction step where the organizational leader gives a direction to the subordinate. The second step - evaluation is when the leader examines the subordinate’s feedback on the initial message with the intention to see how the direction was interpreted. Finally, in the discipline step the leader

19

provides the subordinate with incentive for complying with the initial direction. Appropriate response is rewarded whilst unsatisfactory response is followed by some punishment in attempt to correct the behaviour (Tomkins & Cheney, 1985).

While early critical studies within organizational control efforts were focusing mostly on organizational processes of control and domination, the focus has shifted more towards the possibilities within employee resistance (Mumby, 2005). Mumby aims to signal a concerted effort of exploring resistance as a constitutive element within the complex dynamic of routine organizing (2005). Edwards (1979) identifies two approaches towards organizational control - simple control which requires a person to direct certain behaviour in order to maintain a system, and structural control in which the control is not in the hands of individual supervisors, but instead in the environment of the organization. Tompkins & Cheney (1985) identify two organizational control strategies - obtrusive which relies upon external sources of influence and unobtrusive which relies on embracing company values and having employees identify with the system as a whole. Barley & Kunda (1992) then categorize management strategies as normative or rational. Within a normative strategy, control processes influence certain employee behaviour by encouraging strong personal relationships within the work environments, focusing on communal and social aspects within the organization. While rational strategy provides influence by giving employees clear tasks, objectives as well as reasonable incentives (Barley & Kunda, 1992).

Another approach was developed by Ouchi and further elaborated by other scholars, where organizational control is exercised via control mechanisms that are generally recognized as critical in achieving objectives (Kirsch, 1996). Each of these mechanisms have their own characteristics that govern different aspects of control. Ouchi first contributed to the theory by identifying three mechanisms focusing on market, bureaucratic and clan control (1979). The mechanism of self-control or self-management has also been discussed by other researchers including Mills (1983) and Kirsch (1996). Market mechanisms are about the use of external market mechanisms (Ouchi, 1979). Bureaucracies are then relying on a mixture of close evaluation and socialized acceptance of common objectives. The third mode - clans are relying on a relatively complete socialization process which essentially eliminates the goal incongruence among

20

individuals (Ouchi, 1979). In contrast from clan control, self-control stems from individual objectives and standards, with the individual monitoring their behaviour and rewards or sanctions themselves accordingly (Kirsch, 1996). Self-control is great for tasks that involve a lot of autonomy, creativity, and intellectual activity since it is hard for the controllers to identify appropriate behaviours for such cases (Greenberger & Strasser, 1986).

4.10 Strategies of Organizational Control

There are a number of strategies of organizational control, however the most referenced within literature are simple, bureaucratic, cultural conservative and technical control (Glosset, 2012). Simple control is when a manager is directly involved in the supervisory process from direction to disciplinary action (Edwards, 1979). Bureaucratic control relies on rule systems that are made to influence employee behaviour and facilitate collective action - with or without a supervisor present. Cultural control encourages workers to make organizationally appropriate decisions based on the organizational values even without any rule system to guide them (Glossett, 2012). Concretive control stems from cultural control, however it relies more on participatory organizational techniques like team -based management, whereas members work together to achieve organizational objectives. Technical control relies on intervention of a physical device to substitute supervisor’s tasks like monitoring or disciplinary information. Stemming from the industrial revolution, when work productivity could be based on the pace of production on a conveyor belt, the technical control theory has a significant impact on today’s nature of work. Technical control used to be an excellent management strategy for repetitive work tasks where the supervisor’s control span is too broad to monitor through direct observation (Glosset, 2012). The bigger organizational distance and increasing differences in life situations between capitalists and workers had weakened the extent that personal control and identifications can go (Edwards, 1979). However, nowadays information technology has become an important source of technical control, as IT systems and software assists in monitoring, instructing and providing frames for behaviours (Rennstam, 2017). Key point noted by Rennstam is that instead of being enabling, technology might become deskilling, disciplining and constraining (2017)

21

which is important to take into consideration when relying on information technology to make work processes more efficient.

Providing a more modern view than technical control, Cram & Wiener (2020) pr opose the concept of technology-mediated control (TMC), where managers use digital technologies simply as means to influence workers to behave in accordance with organizational expectations. It can either act as a managerial tool to collect insights on workers or to independently monitor and guide employees without any human intervention (Cram & Wiener, 2020). Such an approach is particularly valuable when looking at employees working from home due to the geographical dispersion and increase (Wiener & Cram, 2017). While using technology to support control processes is not entirely a new phenomenon, TMC shows unique characteristics - apart from the behavioural data (Marabelli et al., 2017) it also captures psychological and emotional information which provides further insights. Cram & Wiener (2020) introduce a framework, consisting of context, interventions, mechanisms and outcomes as the foundation of TMC research. With TMC still being an emerging topic that draws on the perspectives of organizational and informational system control, as well as ubiquitous technology, it provides a good base for future research about TMC as a method gradually replacing traditional control relationships (Cram & Wiener, 2020). Furthermore, the authors introduce a number of research gaps to address in order to further develop the theory, one of which is the TMC mechanisms possibly triggering and leading to individual behavioural changes (resistance behaviour). Aspects such as what data is collected, how it is analysed and who gets to see it are raised all of which might have potential negative impacts on worker well-being and performance (Cram & Wiener, 2020). The authors further point out the importance of understanding what role TMC transparency plays in ensuring compliant behaviour but also preventing any negative socio-emotional side effects (Cram & Wiener, 2020).

This research aims to gain a better understanding of the perceptions and feelings of knowledge-based workers regarding the use of EPM technology in the workplace. We will be relying on the perspective of multidimensional characteristics of EPM developed by Ravid et al. (2020) instead of the traditional unitary phenomenon approach.

22

Furthermore, this paper aims to explore the effect of the place of work (home/office) on knowledge-based worker’s views regarding the use of EPM technologies.

5. Methodology

_____________________________________________________________________________________

In this section we outline the methodological and philosophical choices that guide this research as well as data collection and address the issues of trustworthiness and ethical considerations.

______________________________________________________________________

5.1 Research Paradigm

In our research methodology development, we relied on the Saunders et al. (2007) “research onion” that guided us through the process in a consistent and structured manner. The purpose of this thesis is to explore the perceptions and feelings of knowledge-based workers in regard to the implementation and dissemination of EPM techniques which are centered on intangible factors such as attitudes, personality characteristics, human relationships, and related emotions. This paper follows a constructivist research philosophy as this philosophy emphasizes that humans create meanings, which we attempt to do by looking into the employee perspectives towards the implementation and dissemination of EPM techniques. This philosophy supports the phenomenon under study as we are trying to deepen our understanding in regard to how people feel, react, and interact with EPM techniques.

The approach that we use for theory development is abductive, as we combine the deductive approach of moving from theory to data with the inductive approach of moving data to theory (Suddaby, 2006). An abductive approach allows flexibility in the exploration of the understudied phenomenon (Saunders, 2019) and is essentially incorporated into grounded theory (Suddaby, 2006). As well as that, we aim to understand the meaning of the social phenomena in its natural setting, therefore we are using a qualitative methodology (Antwi & Hamza, 2015) and the data is presented as a descriptive narration.

23

This research is exploratory in nature due to the novelty of the situation where more people than ever are working from home and the rapid implementation and dissemination of the EPM among the workforce. The rapid switch to working remotely brings a completely new variable in the EPM research, the effect of which has not yet been investigated. The aim of our study is therefore to look for patterns and ideas and develop rather than test a hypothesis (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Exploratory research is particularly useful if you wish to clarify your understanding of an issue, problem, or phenomenon, such as if you are unsure of its precise nature (Saunders et al., 2016).

5.2 Research strategy

Consequently, following the purpose of gaining a better understanding of the perception that knowledge-based workers have regarding the use of EPM in the workplace, together with the effects that the locational change has on their views, we use grounded theory as our strategy. Furthermore, the paper aims to provide a holistic and faithful representation of the respondents' views which makes grounded theory suitable for the research. Grounded theory can be defined as the discovery of theory from data that was systematically obtained from social research with the aim of generating or discovering a theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). They saw developing theory through a comparative method, which is essentially looking at the same event or process in different settings/situations as the key task of the researcher. This is a good fit for our study, as while manual labor/service workers have been researched to some extent (Holland et al. 2015; Ravid et al., 2020), we are looking at the under-researched perceptions of knowledge-based employees. Furthermore, the shift of remote work from home introduces new settings that may influence workers' perceptions and feelings in regard to EPM. The research relies on mono-method as only qualitative data is collected, while the research is cross-sectional as the process of the collection takes place at a certain point in time.

The version of grounded theory that is used in this paper is constructivist grounded theory developed by Kathy Charmaz. The reason behind is that the original concept of grounded theory by Glaser & Strauss (1967) seeks objectivity, however, that in itself is a questionable goal (Charmaz, 2008). Both constructivist and objectivist versions of

24

grounded theory adopt a realist position, but constructionists view the learning and portraying of the studied world as problematic (Charmaz, 2008). In essence, the constructionist version of grounded theory redirects the method from the objectivist past and aligns it with the modern 21st century epistemologies (Charmaz, 2008). This approach includes treating the research process as a social construction, scrutinizing research decisions and directions, improvising the methodological and analytic strategies throughout the process of the research, and collecting sufficient data to discern and document how the participants of the research construct their lives and worlds. Data is co-constructed by the researchers and the people interviewed, as it would be naive to assume that the worldviews of the authors does not affect the outcome of the research (Charmaz, 2017). Researchers need to prepare themselves and learn about the worlds of the people interviewed before they get into the process itself. Simultaneous data collection and analysis is key to this approach so you focus early, so you do not make mistakes later as explained by Charmaz (2017). This approach is fluid rather than prescriptive, even research questions might change.

5.3 Data Collection & Sampling

The data was collected via semi-structured interviews in order to have a clear guide and keep participants on the topic. It also gives the participants a chance to express ide as openly and allow changes in direction if necessary. The interviews were recorded and transcribed by the authors for further analysis, all in accordance with the ethics and confidentiality choices discussed below. In line with our research purpose and research strategy the sampling design used was theoretical sampling as the participants have to fit the profile necessary for this research of being knowledge-based employees with remote work experience. A purposive sampling includes the approaching of potential sample members and checking whether they meet the eligibility criteria (Easterby-Smith, Thorpe & Jackson, 2015) before starting the research. We made connections with a group of potential interviewees through social media and personal connections, then we filtered and ranked the potential interviewees based on the criteria outlined previously. After 18 interviews we reached saturation where our interviewees stopped adding any new perspectives to the pool of data that we have collected. Finally, we conducted 2 more

25

interviews to be sure that we had reached saturation. The sample consisted of a broad spectrum of occupations ranging from programming to consultant jobs with no particular focus except that the occupation has to be knowledge-based, meaning that their basic task is thinking (Reinhardt et al., 2011).

This research depends mainly on primary data collected for this research. The primary data consists of 20 interviews with knowledge-based workers who are working remotely from home (for more information check Appendix 3).

5.4 Data Analysis

In pursuit of consistency with the exploratory nature and abductive approach of this study, the data is framed and interpreted by using grounded analysis. It is an open approach that allows building theory that is essentially “grounded” within the data. Meaning that they are identified by a systematic analysis of the data itself (Charmaz, 2014) and will allow us to derive structure by comparing different data fragments with one another (Easterby-Smith, Thorpe & Jackson, 2015).

The grounded analysis of our data is split into 7 steps suggested by Easterby-Smith, Thorpe & Jackson (2015) - familiarization, reflection, open coding, contextualization, focused re-coding, linking and re-evaluation. In more detail, the process was started by sifting through available data and drawing on the collected information. Further on, we evaluated the data in light of previous research about the phenomenon. The data then was coded to create links between the overwhelming text and introduce a system. The coding was done manually, and the technique chosen was open coding as codes were created based on the data itself. In the conceptualization stage, we looked for patterns among the codes that are characterized by similarity, difference, frequency, sequence, correspondence or causations (Saldana, 2009). After having identified the key concepts, we re-coded some of the data in accordance with the focused codes in order to achieve a more in-depth analysis of what is important. During the process of linking, we conceptualized how key categories and concepts relate to each other and how they could be integrated into a theory (Charmaz, 2014) which was finally followed by a more critical re-evaluation.

26 5.5 Trustworthiness

The trustworthiness of qualitative research generally is often questioned by positivists, perhaps because their concepts of validity and reliability cannot be addressed in the same way as in naturalistic work (Shenton 2004). Thus, this research will rely on the criteria for qualitative researchers suggested by Guba (1985). The criteria present a four points alternative approach for qualitative researchers to ensure trustworthiness, which are respectively credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability (Shenton 2004).

5.5.1 Credibility

In order to ensure credibility throughout this research, we provided a detailed explanation of our approach, strategy, data collection, selection, and decision-making, in regard to the manner of identifying and selecting participants. Furthermore, we highlighted the shortcomings of our sample and addressed the potential effects on the research outcome, as well as we provided suggestions and avenues for future research that can cover these shortcomings. During the interviews, we relied on an ethical, confidential, respectful, and friendly manner as described in the section "Ethics and Confidentiality" in order to ensure openness and truthful representation of our participants as well as to alleviate any outside pressure.

5.5.2 Transferability

Due to the qualitative nature of this research generalization, in this case, is applicable to the theory rather than the population. However, the diverse professional occupation of the participants provides overarching perspectives of the perception of knowledge-based workers in regard to EPM but for a more accurate reading of the perceptions, quantitative research that focuses on certain occupations may be needed. Regarding the question of the workplace context (home/office), we believe that the finding can be generalized as the participants provided a more coherent and unified perspective on the matter.

5.5.3 Dependability

The research followed the grounded theory approach with all its checks and balances as well as throughout this research, we provided detailed explanations regarding the

27

approach, methodology, and data collection and analysis. We aim with this rigorous and well-documented approach to provide a more clear and in-depth view of the systematic approach that we relied on to reach our conclusions. That allows the reader to assess the research practices and replicate the work if needed.

5.5.4 Confirmability

The methodological choices throughout this research aimed to provide a clear view of the flow from the collected data to the findings. While the systematic approach of the grounded theory and the process of codification supported by the quotes from the participants aim to present a clear link between the data and constructs emerging from it to the participants' views.

5.6 Ethics and Confidentiality

In order to ensure the ethicality and confidentiality of this research, we relied on the ten principles of ethical practice as presented by Easterby-Smith, Thorpe & Jackson (2015) (See Appendix 2) as well as the guidance for handling personal data in accordance with the GDPR as the research is taking a place in Sweden. Consequently, all the interviewees received a full explanation regarding the aim, purpose, and personal rights in regard to the research as well as that, they have been informed that the outcome of this research will be published to the public. Furthermore, all the interviewees were informed that participation in this research is completely voluntary, and they can withdraw their consent at any point. They were also informed that their data will be recorded anonymously where the only identifiable data about them that would be collected is their age and field of occupation. All interviews were conducted in a private setting outside the business hours in a transparent and respectful manner in order to allow the participant to express themselves freely. In the end, this research has no external financial support, and the researchers have no conflict of interest.

28

6. Empirical Data

_____________________________________________________________________________________

In this section we will present the empirical findings that emerged from the conducted interviews. The section will be divided based on the themes that emerge from the interviews.

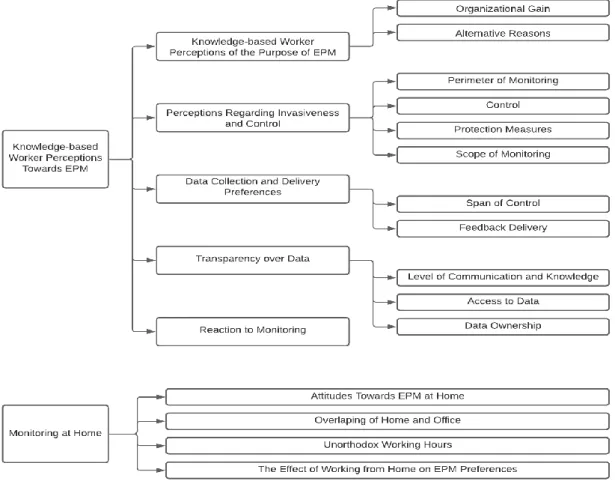

______________________________________________________________________ The following section provides insight into the findings and themes that have emerged from the interviews with 20 knowledge-based workers regarding the dissemination of EPM. The participants come from different sectors with varying levels of autonomy and have different experiences with EPM- ranging from no known previous interactions with EPM, to actively being monitored via EPM. Furthermore, one participant became aware of the use of EPM in the company a long time after the beginning of their occupation. The overview of the coding is presented in Figure 2 and each category has its own in-depth figure for a clearer understanding.

29

6.1 Knowledge-based Worker Perceptions of EPM

In the following section, we present the perceptions of knowledge-based workers regarding the implementation and dissemination of EPM, categorized in 5 main themes that have emerged from the empirical data.

6.1.1 Knowledge-based Worker Perceptions of the Purpose of EPM

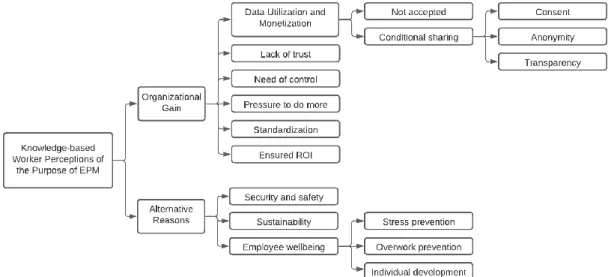

Figure 3: Coding for: Knowledge-based Worker Perceptions of the Purpose of EPM.

The overall understanding of why exactly companies monitors their employees revolves around lack of trust and maintaining control instead of employee wellbeing. Participants described the monitoring purposes as organizational gain, emotional pressure to do more, spotting “lazy employees” and standardization of the evaluation process. Essentially, the companies want to make sure that people do their jobs, and the company gets the value that they pay for.

P2 “I think the companies monitor their employees because it is just there, it is an option to easily control them and take a look at what's going on. It is easy to judge

them, if everyone else is doing it (monitoring), it's how humans work.”

P18 “A company might be using tracking to emotionally pressure people to do more, it is demotivating for people to keep them on such a short leash daily.”