J

ENSA

GERSTRÖM&

R

ICKARDC

ARLSSON 2013:14Why does height matter in

hiring?

Running head: DECOMPOSING THE HEIGHT PREMIUM

Why does height matter in hiring?

Jens Agerström and Rickard Carlsson

Author note:

Jens Agerström, Department of Psychology, Linnaeus University; Rickard Carlsson, Department of Psychology, Lund University. The authors have contributed equally to this paper.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Jens Agerström, Department of Psychology, Linnaeus University, 391 82 Kalmar, Sweden. Email:

Abstract

Although previous research has established that physical height matters in hiring contexts, it is less clear through which channels height exerts its effect. The current research examines several potential components of the height premium: warmth, competence, job competency for a leadership position, physical health, and attractiveness. We made target individuals taller or shorter by digitally manipulating photographs, and attached these to job applications that were evaluated by real recruiters. The results show that in the context of hiring a project leader, the height premium consists of increased perceptions of the candidate's general competence, job competency, and health, whereas warmth and attractiveness seem to matter less.

Research on the importance of physical height for workplace success shows that tall people earn higher salaries, are more likely to hold high-status jobs, and to ascend into leadership positions, compared with short people (see Judge & Cable, 2004, for a meta-analysis). Although height is related to actual job performance, research suggests that height exerts a stronger effect on subjective evaluations of performance (Judge & Cable, 2004). Indeed, in a now classical study, when recruiters were asked to make a hypothetical hiring decision between two equally qualified job candidates, they chose the taller candidate (Kurtz, 1969).

What does the height-premium in hiring consist of? A simple model based on the halo error (Thorndike, 1920) would suggest that if employers view tall applicants favourably with respect to some personality dimension, they tend to do so with respect to numerous other dimensions as well. Recently, however, research on the Stereotype Content Model (e.g., Fiske, Cuddy, & Glick, 2007) suggests that stereotypes are not necessarily uniformly positive or negative but rather consist of a mixture of warmth and competence related traits. Warmth speaks to the social group’s functioning in social situations whereas competence speaks to its functioning at tasks. For example, Asians and Jews tend to be positively stereotyped on competence, but negatively on warmth (Fiske et al, 2007), resulting in both negative and positive consequences. This distinction is important when it comes to height and hiring as, for example, short individuals should have much to win from crafting their résumés in a way that counteracts the stereotype. If short people are stereotyped as low with respect to competence but not warmth, there is no need for them to try to create an extremely friendly impression in the personal letter. Rather, they should make sure to emphasize their competence-related abilities (e.g.,

productivity) instead. This becomes even more important as high levels of perceived warmth (competence) can backfire and cause the applicant to be viewed as less competent (warm; Kervyn, Judd, & Yzerbyt, 2009).

From the animal kingdom to human beings, physical size has served as a proxy for power, status, and respect (Judge & Cable, 2004). Because power, status, and respect help individuals achieve their goals, i.e., the hallmark of competence (Fiske et al., 2007), tallness should be linked to perceptions of competence. Indeed, research shows that tall people are perceived to be more intelligent, dominant, and “leader-like” (e.g., Blaker, Rompa, Dessing, Vriend, Herschberg, & van Vugt, 2013).

The link between height and warmth is less clear. As noted above, insofar as tallness is a desirable characteristic in society, a halo effect would mean that tall people are evaluated more positively across the board. Yet, powerful people are typically perceived as psychologically distant (Trope & Liberman, 2003), less likely to understand other people’s perspectives (Galinsky, Magee, Inesi, & Gruenfeld, 2006), and less prone to express empathic concern (Woltin, Corneille, Yzerbyt, & Förster, 2011). As for the actual research evidence concerning the link between height and warmth, it has been inconsistent (e.g., Jackson & Ervin, 1992), warranting further scrutiny.

Moving beyond warmth and competence, tall people are generally considered to be more physically attractive (Martel & Biller, 1984). Because attractive people are more likely to be hired than unattractive people (Marlowe, Schneider, & Nelson, 1996), attractiveness may play a role in the height-premium.

Finally, research suggests that tall individuals are perceived to be more physically healthy than short individuals (Blaker, et al., 2013). Because poor physical health predicts

absenteeism (Farrell & Stamm, 1988) and lower productivity (Ford, Cerasoli, Higgins, & Decesare, 2011) short people might face yet another disadvantage when seeking employment.

The current research

The aim of this research is to decompose the height-premium in hiring. Based on previous research and theorizing, we have identified the following potential components: Warmth, competence, job competency, leadership, physical health, and attractiveness. While tallness has previously been linked to competence, physical health, and physical attractiveness (but not warmth), the unique and combined contribution of such judgments to the observed height premium in the specific context of hiring needs to be examined and clarified.

Of course, competence, specific job competency and leadership have considerable overlap, and the magnitude of this overlap will depend on the specific context. In this study, we focus on a position as a project leader. Consequently, leadership ability becomes an integral part of the job competencies. However, we can still differentiate between competence and job competency. The former deals with whether a candidate is generally competent, whereas the latter deals with if the candidate has the specific competencies required for the job. To illustrate, Bill Gates and Stephen Hawking could not simply switch jobs although both are extremely competent in a general sense. Furthermore, physical health and attractiveness are of course related to some extent, but since it is easy to come up with instances when physically healthy people are not very attractive, these two variables should be examined separately.

Our study departs from most previous research by examining whether professional recruiters (rather than students) demonstrate height bias in hiring evaluations. Although previous research (Judge and Cable, 2004) does suggest that employers also exhibit height bias (e.g., in salary allocations), it is primarily based on register data. Such correlational findings inherently limit the conclusions regarding the causal role of height. To address these two limitations, we conducted a highly controlled experiment on real recruiters.

Method

Participants, materials and procedure

Sixty recruiters (M = 34 years; 63% females), employed at a recruitment firm in a major Swedish city participated in the experiment. They were asked by a colleague (who unbeknownst to them was also the experimenter) if they could help her with the

evaluation of a job candidate for research purposes. The recruiters were informed that a male applicant had applied for a project leader position at a large company where he would be responsible for a considerable budget and some staff. They were then given the job application which consisted of a personal letter and a CV. The personal letter

contained a photograph of the applicant.

We manipulated the physical height of the applicant in the photo by using imaging software. To facilitate perceptions of the applicant’s height, he was standing in a doorpost. We constructed one tall and one short version of the applicant. They were identical in all respects except for the applicants’ height. The material was pretested on 83 students, confirming that the tall applicant would be perceived as significantly taller than the short applicant.

The recruiters were randomly assigned to either the tall or short experimental conditions by the experimenter (who was blind to conditions). They evaluated the candidate on a 7 –point scale (1 = not at all; 7 = to a very high extent) with respect to competence (talent, skill, intelligence; α = .89), warmth (sympathy, friendliness, honesty; α = .86), job competency (employability, leadership potential; task related competence, role fitness; α = .86), health (physical fitness, and health; α =.78) and attractiveness (physical attractiveness). Finally, they were asked to estimate the height (in centimetres) of the candidate (manipulation check). The reason why we measured perceived height last was that we did not want to explicitly direct the recruiters’ attention to the applicant’s height until after they had made their evaluations. Thus, if the recruiters base their evaluations on the applicant’s height, they would have done so spontaneously.

During the debriefing, none of the recruiters reported any suspicion about the purpose of the study.

Results

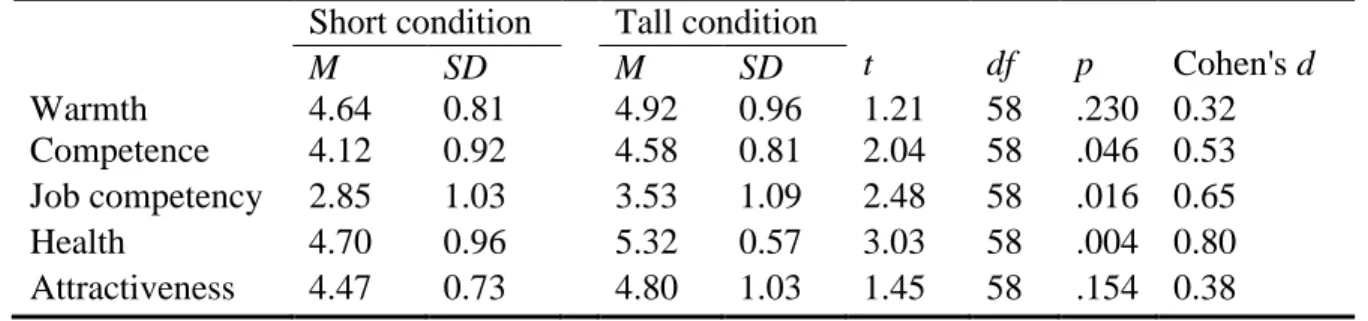

First, it was confirmed that the tall candidate was indeed perceived as taller (180.17 cm) than the short candidate (171.50 cm), t(58) = 8.39, p < .001, d = 2.18. Next, because the correlations among our dependent variables were generally moderate in size (Table 1), we proceeded with a MANOVA. The main effect of manipulated height was significant, F(5,54 ) = 2.44, p = .046, ηp2 =.18. Follow-up t-tests (Table 2) revealed that the tall applicant was rated significantly higher in general competence, job competency, and physical health. He was also rated as slightly higher in warmth and physical attractiveness, but these differences were non-significant.

Table 1. Bivariate Pearson correlations among the dependent variables Outcome 1 2 3 4 5 1. Warmth - .390** .349** .428** .328* 2. Competence - .565** .593** .290* 3. Job competency - .339** .130 4. Health - .373** 5. Attractiveness - Note. * = p < .05, ** = p < .01.

Table 2. T-tests for the effect of height on the dependent variables Short condition Tall condition

t df p Cohen's d M SD M SD Warmth 4.64 0.81 4.92 0.96 1.21 58 .230 0.32 Competence 4.12 0.92 4.58 0.81 2.04 58 .046 0.53 Job competency 2.85 1.03 3.53 1.09 2.48 58 .016 0.65 Health 4.70 0.96 5.32 0.57 3.03 58 .004 0.80 Attractiveness 4.47 0.73 4.80 1.03 1.45 58 .154 0.38 Discussion

The purpose of the present research was to explore the content of the height-premium in hiring. The results show that tall the tall individual was rated higher on all dimensions. However, the effects for warmth and attraction were weak and non-significant, whereas the other effects ranged from medium to strong and were statistically significant. Still, these results are consistent with an overall halo effect, rather than a mixed stereotype. For example, Asians tend to be positively stereotyped on competence, but negatively on warmth. In contrast, there does not appear to be any downside of being tall.

It is noteworthy that an eight-centimeter difference in the applicant’s height is sufficient to have an (moderate) effect on professional recruiters’ evaluations. Compared to other experimental studies on height, our manipulation was rather modest. For example, in Blaker et al.’s (2013) leadership experiment, the height difference was 30 centimeters. Future research should examine how large of a difference that is required for height to matter in hiring. It is also important to establish where in the height distribution differences matter the most, but also if tallness becomes a liability for extremely tall people.

The unique contribution of the present research is that all dimensions were captured simultaneously in an applied context, using professional recruiters as participants. Of course, our findings are limited to this specific hiring context (project leader). Perhaps the effect of height on perceptions of warmth and attractiveness is stronger in other contexts where warmth and attractiveness are given higher priority by the recruiters (e.g., hiring of flight attendants). Another limitation of the present study is the relatively small sample. However, we do have 30 observations per cell, and the sample is highly representative of the population (recruiters). Still, a larger sample may have helped us to interpret the weak effects on warmth and physical attractiveness more precisely. Finally, the results are limited to male applicants.

The present study adds to the growing body of research focusing on the role of height in career success. Yet, unlike ethnic and gender discrimination, for example, discrimination on the basis of height is not illegal. In relation to this, one could argue that a labor market that continues to rely on markers (e.g., height) that are often irrelevant for the job in question, consolidates both gender (women are shorter than men on average) and ethnic

(ethnic groups differ in height) disparities in employment. Further, because height is related to nutrition and physical health during childhood (Lundborg, Nystedt, & Rooth, in press), people who come from poor family environments face yet another obstacle in their careers. In other words, the height-premium is not fair in that everyone has an equal chance to increase their career success by growing up to be tall. Rather, it is a bias that further enhances other inequalities on the labor market. However, height bias also presents researchers with a unique opportunity. Rather than focusing on infected and sensitive issues such as racial discrimination, an in-depth understanding of how height bias can be reduced in the recruitment process may in the long run help to reduce other types of bias as well.

In conclusion, recruiters find tall applicants to possess more general competence-related abilities such intelligence, to be better suited for a job that requires leadership ability, and to be physically healthier, compared with their shorter counterparts. Although they are not judged to be significantly higher in warmth or physical attractiveness, nothing suggests that there is a penalty for being a tall when applying for a leadership position. It is, indeed, a height premium. To some, this may seem like a trivial finding. Why should we care if tall people are given better opportunities than short people? After all, hiring staff on the basis physical stature is not illegal. As an answer to this, we would like to pose a counter-question: If we cannot get rid of discrimination that stems from something as trivial as height, how could we ever hope to combat race or gender discrimination?

References

Blaker, N. M., Rompa, I., Dessing, I. H., Vriend, A. F., Herschberg, C., & Van Vugt, M. (2013). The height leadership advantage in men and women: Testing evolutionary psychology predictions about the perceptions of tall leaders. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 16, 17-27. doi: 10.1177/1368430212437211

Farrell, D., & Stamm, C. L. (1988). Meta-analysis of the correlates of employee absence. Human Relations, 41, 211–227. doi: 10.1177/001872678804100302

Fiske, S.T., Cuddy, A. J. C., & Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11, 77-83. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005

Ford, M. T., Cerasoli, C. P., Higgins, J. A., & DeCesare, A. L. (2011). Relationships between psychological, physical, and behavioural health and work performance: A review and meta-analysis. Work & Stress, 25, 185-204. doi:10.1080/02678373.2011.609035

Galinsky, A. D., Magee, J. C., Inesi, M. E., & Gruenfeld, D. H. (2006). Power and

perspectives not taken. Psychological Science, 17, 1068–1074. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01824.x

Jackson, L. A., & Ervin, K. S. (1992). Height stereotypes of women and men — the liabilities of shortness for both sexes. Journal of Social Psychology, 132, 433–445. doi:10.1080/00224545.1992.9924723

Judge, T. A., & Cable, D. M. (2004). The effect of physical height on workplace success and income. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 428-441. doi: 10.1037/0021-

9010.89.3.428

You want to appear sociable? Be lazy! Group differentiation and the compensation effect. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 363–367.

10.1016/j.jesp.2008.08.006

Kurtz, D. L. (1969). Physical appearance and stature: Important variables in sales recruiting. Personnel Journal, 48, 981–983.

Lundborg, P., Nystedt, P., & Rooth, D. (in press). Height and Earnings. The Role of Cognitive and Non-Cognitive Skills. Journal of Human Resources.

Martel, L. F., & Biller, H. B. (1987). Stature and stigma: The biopsychosocial

development of short males. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books. doi: 10.1037/025440 Thorndike, E. L. (1920). A constant error in psychological ratings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 4, 25-29. doi:10.1037/h0071663

Woltin , K.-A., Corneille, O., Yzerbyt , V.Y., & Förster, J. (2011). Narrowing down to open up for other people's concerns: Empathic concern can be enhanced by inducing

detailed processing. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 418-424. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2010.11.006

Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2003). Temporal construal. Psychological Review, 110, 403-421. doi:10.1037/a0018963