Motivations and Barriers of Using

Emerging Technology in Eco-label Certification

for Sustainability

From the certification companies’ perspective

Emilio Asensi

Renars Kaulins

Main field of study – Leadership and Organisation

Degree of Master of Arts (60 credits) with a Major in Leadership and Organisation

Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organisation for Sustainability

(OL646E), 15 credits Summer 2019 Supervisor: Ju Liu

Title: Motivations and Barriers of using emerging technology in eco-label certification

for sustainability, from the certification companies’ perspective

Authors: Emilio Asensi, Renars Kaulins

Main field of study: Leadership and Organisation

Type of degree: Degree of Master of Arts (60 credits) with a Major in Leadership and

Organisation

Subject: Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organisation for Sustainability (OL646E), 15 credits

Period: Summer 2019 Supervisor: Ju Liu

Abstract

The demand for organic sustainable products has been growing exponentially in the past years, pressuring the industry to showcase the sustainable origin and conditions of their products to their consumers. Companies use certifications and eco-labels to show the sustainability behind their products, but the standards behind these certifications can be hard to understand as certification companies are struggling to communicate them to the end consumers. Emerging technologies such as QR codes, IoT and blockchain provide new options for increasing traceability and transparency in the certification industry, but these technologies are not widely adopted.

This thesis investigates the current practices in certification companies by performing semi-structured interviews with different actors in the certification industry, to understand what are the motivations and barriers that companies see in the adoption of new technologies for transparency and traceability. Once motivations and barriers have been identified, the authors frame them into a motivational model and propose organisational strategies for these companies in order to overcome the barriers and produce change towards technology adoption, traceability and transparency improvement and sustainability advocacy.

Industry practitioners can use these technologies to increase the trust in their brands and to ensure the sustainability of their supply chains. Further, new emerging technologies can be seen as a tool to assess the companies’ strategic and tactical decisions to comply with their CSR policy, decisions that can eventually lead to an organisational change providing companies with a more sustainable perspective of their operations.

Keywords: Certification, eco-label, technology, QR codes, IoT, blockchain,

sustainability, transparency, traceability, barriers, motivations, organisational strategy, organizational change.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ...1

1.1. Background in sustainability...1

1.2. Transparency in supply chains...2

1.3. New technologies for transparency ...3

1.3.1. An integrative technology portfolio ...4

QR Codes...4

Smart IoT devices...5

AI and Machine Learning ...5

Blockchain ...6

1.4. Certification industry ...8

Standards ...9

Accreditation ...9

Certification ...10

Labels & Eco-labels ...10

1.5. Research problem ...11

1.6. Purpose and aim of the research ...12

2. Theoretical Background and Analytical framework ...13

2.1. Organisational Strategy and Change...13

2.2. Motivation on the adoption of new technologies ...14

2.3. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology ...16

2.4. Analytical Framework ...17

3. Research design ...18

3.1. Research Strategy and Approach ...18

3.2. Research Method ...18

3.2.1. Case selection ...18

3.2.2. Data collection ...19

3.2.3. Data analysis...21

4. Empirical Finding ...23

4.1. Current Status of the Certification Industry...23

Eco-label standards ...23

Assurance methods ...25

Transparency...27

Technology ...28

Culture ...30

Partnership and collaboration...31

4.2. Motivations ...32

Motivation 1: Consumer demand ...32

Motivation 2: Thinking ahead ...33

Motivation 3: Usefulness...35

4.3. Barriers ...37

Barrier 1: Lack of consumer demand and pressure...37

Barrier 2: Lack of financial resources...39

Barrier 3: Legislation ...41

Barrier 4: Miscommunication...42

Barrier 5: Knowledge or Interest in emerging technologies...43

Barrier 6: Fear ...44

Barrier 7: Complexity ...45

5. Research Analysis ...47

6. Conclusions ...52

Limitations and recommendations ...54

References ...i

List of Tables

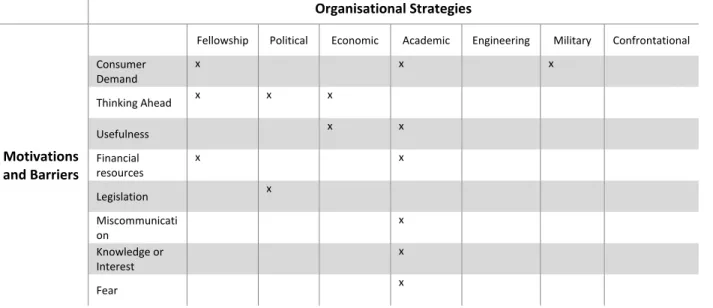

Table 1: Overview of the interviewees ...19 Table 2: Mapping organisational strategies with motivations and barriers for

technology adoption ...52

List of Figures

Figure 1: Triple Bottom Line model (Elkington, 1994) ...2 Figure 2: A body figure conforming an integration model of new technology for transparency...4 Figure 3: An example of blockchain usage in certification processes...7 Figure 4: Basic structure of the organic certification system (Schulze, Jahn &

Spiller, 2007) ...8 Figure 5: UTAUT model (Viswanath et al., 2003)...17

1. Introduction

This chapter presents a brief introduction of the background for the thesis topic. It starts with a background in sustainability and why it is important to address, then introduces the concept of transparency in supply chains and its relation to sustainability, while giving an entry point to new emerging technologies that can provide transparency and traceability. A deeper explanation of these technologies is presented due to their relevance to the research. Then, a closer look at the certification industry is taken to provide an understanding of various actors and their function involved in the certification scheme and how does that affect the end consumer. The chapter ends with a presentation of the identified research problem followed by the purpose and aim of the research.

1.1.

Background in sustainability

World population is reaching new highs and is projected to reach 8.6 billion in 2030, 9.8 billion in 2050 (United Nations, 2017). Growing population and the globalized economy are driving the need for raw materials and challenging industries to meet the demand. Additionally, advancements in communications networks have been important factors in driving market saturation and creating even greater competition. Thus, putting pressure on various actors involved in the supply chain systems by often creating conditions that favour the least environmentally and socially beneficial practices (Jovane, Seliger & Stock, 2017).

At the twenty-first session of the Conference of the Parties (COP 21) held in 2015, nation leaders from all UN member states gathered and reached a landmark agreement to combat climate change and signed Paris Agreement (UNFCCC, 2018). Further United Nations (UN) established 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with an agenda to be reached by 2030. Among these goals, SDG 12 “Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns” has created pressure for governments to introduce more stricter laws across industries and addressing the need to “achieve the sustainable management and efficient use of natural resources” and developing legal frameworks to “encourage companies, especially large and transnational companies, to adopt sustainable practices and integrate sustainability information into their reporting cycle” (Sustainabledevelopment.un.org, 2016). All this requires various industries to adopt new behaviours and processes throughout their entire supply chain. Actors in all stages need to adopt a strategic perspective for their sustainable challenges (Porter & Kramer, 2006).

For companies in general, sustainable development requirements translate into economic, social and environmental sustainability (Pereira de Carvalho & Barbieri, 2012). This refers to a framework that was introduced already back in 1994 by John Elkington named the 'triple bottom line' (TBL), where it was suggested for companies to focus on social and environmental concerns as just as they do on profits – ‘people,

planet and profit’ (Elkington, 2001). Putting all these aspects into perspective,

companies are pressured to look at their entire supply chain in order to become more sustainable while maintaining their competitiveness.

Figure 1: Triple Bottom Line model (Elkington, 1994)

Awareness of pressing issues of environmental and social challenges amongst consumers has risen over the last decade, which has resulted in a growing demand for products that are produced in a more sustainable manner (Cherian & Jacob, 2012; Cervellon & Carey, 2011). Additionally, Christopher (2012) suggests that apart from the quality of the products, customers are also becoming more demanding in terms of the speed, flexibility, and predictability of delivery service. This puts even greater pressure on companies and their supply chains to satisfy customers while delivering on the promise of being environmentally and socially responsible enterprise.

1.2.

Transparency in supply chains

In regions such as Europe and North America, the demand for agricultural and other commodities is growing. However, the supply cannot be met by local producers, thus the demands are increasingly being met by global supply chains (Yu, Feng, & Hubacek, 2013). While the global economy and advancements in the network offer opportunities to extend the sourcing and manufacturing around the world, at the same time supply chains have never been as complex as they are today (Mangan & Lalwani, 2016). These operations can lead to opaque conditions and difficulties to navigate in the global supply chain systems. As a result, creating vulnerability for companies to oversee 'behind the scenes' of their suppliers or manufacturers. However, by increasing transparency, these risks and uncertainties can be reduced (Carter & Rogers, 2008).

Taking into considering the fact that the supply chain process involves the product from the initial processing of raw materials to delivery to the end-user, having more transparency is a crucial step toward the development of sustainability (Ashby et al., 2012). Further as Carter and Rogers (2008) suggest transparency improves communication among different actors, thus strengthening trust and collaboration. This is especially important when evaluating whether the ingredients and working conditions of the supplier meet the requirements.

Additionally, transparency addresses the distribution of responsibility (Gardner et al., 2019). With no doubt producers carry a big responsibility in driving more sustainable businesses, so as consumers hold the power to impact supply chains, which further translates into what is produced and how it is being produced (Grunter, 2011; Shaw, Newholm and Dickinson, 2006). However, as Gardner et al. (2019) explains that “there is growing recognition of the need for actors involved in

every step of global supply chain, and not only producers and consumers, to share the responsibility of placing production systems on a more sustainable footing'' (p.

164). Taking the cosmetics industry as an example, for a cosmetics brand to formulate a skincare product can often involve more than 200 ingredients. This can result in very complex supply chains and difficulties to track the origin of the components. Therefore, by increasing transparency in the entire supply chain can incentivize to keep every actor accountable, including actors such as traders, processors, retailers, and investors that make up global supply chains.

Supply chain information has traditionally been distributed through reporting and disclosure instruments by private and civil society actors, such as company sustainability reports and certification schemes and labels (Egels-Zandén et al., 2015). These instruments often relying on third-party certification bodies to assure the credibility and validity of the information. However, there are delimitations to the traditional forms of assurance in terms of efficiency and reliability. With the rapid advances in technology, there are new technologies such as Blockchain, Internet of Things (IoT) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) which are offering to improve the current processes and bring new forms of trust and transparency. Referred technologies have a great potential to improve transparency and traceability which in result will drive overall sustainable development.

1.3.

New technologies for transparency

We live in a historical period without precedents. In the last 30 years, the internet has reached almost all corners of the world connecting us more than ever and giving access to information which used to be very difficult to obtain if not impossible. Reliable information is a key component to generate trust when we speak about sustainability. Even more, when the intention is to prove to the consumers, certification organizations or anyone interested, a break from traditional unsustainable practices and a change in a company strategy towards sustainability. A way to ensure transparency, traceability, and reliability of that information is by making use of some innovative technologies already available in the market. The technologies described below are in an early stage of implementation and therefore

not widely adopted, but present huge potential to improve the quality of the data, the access to information and to drive change in the industry towards more sustainable practices, in particular in their supply chains.

1.3.1. An integrative technology portfolio

Emerging technologies and innovations present many benefits for transparency by themselves, but the true potential arises in the combination of them. A good representation of this combined effort is an integrative portfolio of technologies mimicking a human body, where:

QR codes represent the shape of the body; the image that allows the

communication between the external physical and the internal digital worlds.

IoT devices represent the senses of the body; the eyes that watch the reality

and the hands that interact with its environment.

Blockchain represents the heart; the embedded trust and credibility it

provides to any interaction, the will to communicate transparent information.

AI and Machine Learning represent the brain; the computing power and

algorithms making the best decisions based on predefined requirements, considering those requirements of transparency and sustainability.

Figure 2: A body figure conforming an integration model of new technology for transparency

QR Codes

A QR Code is a matrix code with a symbolic representation that can be easily read by a scanner, camera or any other optical reading device. It contains information in both vertical and horizontal directions, while a traditional barcode has only one

direction of data (Rouillard, 2008). People can read QR Codes by using the software integrated into their phones, which interprets the image and shows the information on the screen. Depending on the information contained in the QR Code, the phone may open a website, a predefined phone number may be dialled, an email may be sent, or a specific application may be launched.

Because the simplicity and fast action of QR Code processing, the barcode system allows products to be tracked efficiently, accurately and faster than manual data entry systems (Liu, Yang & Liu, 2008). QR codes are starting to be used more and more in companies for story-telling, linking the finalized product to the farmer or worker in undeveloped countries which sourced the raw materials, explaining the specific amount and characteristics of ingredients in a formulation, and even to show the full transparency policy of an organisation.

Smart IoT devices

A smart device is a machine or piece of electronics which can collect and transmit information to a third party physically located somewhere else by using embedded remote connectivity. When using the Internet to make this connection, is called to be part of the Internet of Things (IoT). This interconnectivity gives access to the information collected by smart devices to any interested person or organization, like consumers or certification organizations addressing sustainable practices.

Recent IoT technologies are enabling products to create value even after they have left the supply chain to deliver information such as location, condition or availability (Raynor & Cotteleer, 2015). The generated data can help companies improve productivity, but also better communicate their processes with their end-users. The organic industry, as an example, needs to know the conditions of a plant in order to verify its status, if pesticides have been used, the quality of the soil and where has it been cultivated, if in a traditional farm, a greenhouse or a piece of land taken from a forest. Smart devices can monitor and communicate the required information almost in real-time and to a virtually unlimited number of stakeholders, increasing the quality and reliability of the information. More access to information involves more trust if the right conditions are met. Smart devices, if used appropriately, have the potential to also monitor the working conditions of farmers or other workers and improve them by sharing their story (Mohanraj, Ashokumar & Naren, 2016). IoT devices can register if workers have been working too many hours consecutively, if it was too hot or too cold for their health or if a truck driver had enough hours of rest during a journey.

This information does not come without a level of scepticism and a feeling of lack of freedom, but the intention is to use it to improve working conditions, as similar technologies if not the same are already in use to improve companies’ benefits (Asplund & Nadjm-Tehrani, 2016). The problem with these practices is not the technology, but the people who make bad use of it in their own interest.

AI and Machine Learning

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has made great progress in the last years simulating human behaviour. Those advancements are powered based on symbolic representation: the idea that perception and cognitive

processes can be modelled and simulated using enough data. AI systems aim to embed the knowledge and reactions of a human in a digital form, representing its behaviour symbolically in the form of production rules, frames or semantic networks (Monostori, 2003).

Machine learning, as an extension of the AI potential, develops programs and algorithms to detect patterns in data. Such algorithms are used in many services as recommendation systems, personalized Internet advertising or natural language processing (Monteleoni, Schmidt & McQuade, 2013), but it also has benefits for decision-making processes and sustainability, learning what are the best decisions and implementing them.

Blockchain

Blockchain is an innovation in the information and communication technologies (ICT) as a tool which sets protocols and rules to ensure transparent, traceable and reliable information. The idea of a blockchain is a chain of blocks where each block includes the information of the previous blocks in the chain, new or updated relevant information and a security code called hash, working as a database. A block may contain the date when the information was written, the location of a package and the name of the person writing the information. That block is then distributed to a network of interested stakeholders. When a second block is created to update the location of the package, it does not only include the new information but also a code generated by an algorithm using the information of the first block, so if someone tries to modify the information of the first block to change where the package was in its origin, the second block will raise an alarm as the code would now be different, alerting the members of the network (Arefayne, Ellul, & Azzopardi, 2018). This system allows to create trust on the reliability of the data and requires the approval of the majority of stakeholders to modify a block, an almost impossible task in public blockchains. The following features make blockchain to stand out among other innovations (Pratap, 2018-1):

Decentralized: All members of the chain have a copy of it, and none can modify

the chain without the agreement of the others. This allows transparency, security and power distribution among the stakeholders.

Peer-to-Peer Network: The interaction between two members can be done

without the requirement of any third party. Blockchain uses P2P protocol, which uses approval through machine consensus.

Immutable: Data written in a block cannot be changed. The only way to modify

a block is to get approval by every member of the chain, while it is easier and historically more traceable to create a new block showing the modifications. This is due to each block containing the hash of the previous block, as changing a block hash with new information would create a disagreement with the next block.

Tamper-Proof: The previously mentioned disagreement makes easy and fast

Private blockchains also exist and have different particularities, but we will not cover them in the thesis as their aim is to keep the data robust, but not necessarily transparent.

Transparency and visibility in supply chains are becoming more and more important for consumers, as they aim to choose products that are produced sustainably and ethically (Maayan, 2019). But to assure the validity of the information is not always an easy task, and that is where technology like Blockchain can be a potential solution. “Blockchain is designed to eliminate centralized transaction ledger's and use a distributed model instead, where everyone has access to all of the data while the system being extremely resistant to tampering. Using Blockchain, every participant of the supply chain can access one linked encrypted and validated information, providing everyone involved with high efficiencies and guaranteed data integrity” (IBM, 2019).

Figure 3: An example of blockchain usage in certification processes

Supply chains have a lot of challenges that can be addressed with blockchain, as their complexity leads to wrong information, challenging tracking and bad transparency. The biggest benefits of blockchain in supply chains are (Pratap, 2018-2):

Traceability: Supply chains are complex, companies can source their raw

materials from many locations, produce the product in different facilities and distribute them from a completely separated place. Due to this, it is very complicated, even for large organizations to keep track of each and every registry, leading to missing packages, lack of information and bad logistics management. Using blockchain, and combining it with smart devices or smart labels, allows to easily access the product information and ensure the reliability of the data, like the location, and to prevent theft.

Trust: Trust is an important factor in all supply chains, which traditionally is

gained through experience and many interactions between the partners. However, this is time and money consuming and does not create trust further than the involved partners, it does not reach per se the end consumers or regulatory authorities. A block of information in the blockchain is immutable and tamper-proof, creating trust.

Transparency: As a decentralized chain where every stakeholder has an

identical copy, it becomes easier to share information, ensure its validity and prevent misunderstandings.

Cost Reduction: According to a survey of supply chain workers conducted by

the American Productivity and Quality Center (APQC) and the Digital Supply Chain Institute (DSCI), more than one-third of people cited reduction of costs as the topmost benefit of the application of Blockchain in supply chain management (DSCI, 2018). Due to the traceability of the products, costs are reduced in logistics and missing packages, while the P2P communication allows the elimination of middlemen and intermediaries, which as well reduces the risk of frauds and thieves.

The value of adopting blockchain technology reflects on the capability to decentralize the data, having one copy of the chain per member, while maintaining the data integrity. The strong values of traceability, transparency and immutability make blockchain technology with huge potential to create trust all along with the globe, from end consumers to suppliers, producers and governments.

Despite the explained benefits, Blockchain is still in a very early stage and cannot avoid presenting flaws and weaknesses related to its maturity as the lack of standards and integration with legacy systems. Also, technological challenges when addressing access, ownership, scalability or security (Niranjanamurthy & Nithya & Jagannatha, 2018). Some of those weaknesses will be improved over time, and some others can be improved with standardization, a very useful practice related to the certification industry.

1.4.

Certification industry

Consumption of goods and services have been growing and the supply chains have become more complex, while as described in section 1.1 demand has grown not only in terms of the quality but also in terms of more sustainable consumption. Research made by Young, Hwang, McDonald & Oates (2009) shows that green consumer behaviour is highly influenced by the labels on the product, such as Fair Trade, Ecocert and similar. However, having an overview and clear understanding of various labels can be overwhelming and hold little meaning or value for consumers. This can be creating vulnerability amongst customers to be exposed to greenwashing practices by companies to maximise their financial profits. While we as consumers have our expectations from the companies to deliver more sustainable products, for companies, this translates into having transparency and trust in their supply chains. From having a clear overview of where the raw materials are sourced, conditions of the employees involved in the supply chain, the conditions and the quality of the operational processes involved in the manufacturing and finally to how the product reaches the end consumer (ChainPoint, 2016). This requires a common language, a consensus from all parties involved in the operations on the expected quality of the product and the requirements involved in the entire supply chain (Matus, 2010).

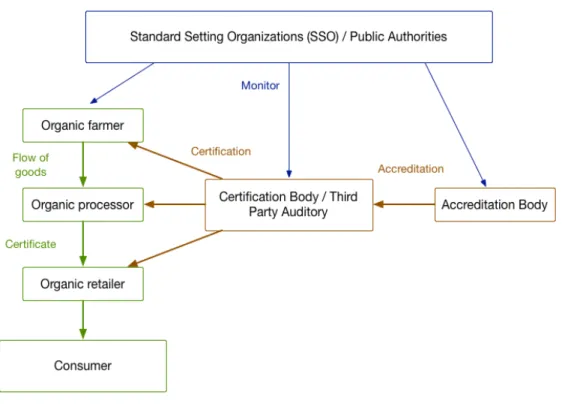

Supply chain information has traditionally been disseminated through diverse forms of reporting and disclosure instruments by private and civil society actors, such as certification schemes and labels (Egels-Zandén et al., 2015). As illustrated in Figure 3, certification schemes are complex and involve multiple actors and various procedures.

Figure 4: Basic structure of the organic certification system (Schulze, Jahn & Spiller, 2007)

Standards

One of the main objectives of standardization is usually that everybody adheres to the same standards, i.e. the same procedures or product specifications. As defined by the International Organisation for Standardization (ISO) standard is a “documents that provide requirements, specifications, guidelines or characteristics that can be used consistently to ensure that materials, products, processes, and services are fit for their purpose” ("International Organization for Standardization", n.d.-b). As mentioned in the definition standards can be used as “guideline” to develop product and process standards.

The Food and Agriculture Organization explains that “setting international standards has proven to be very difficult due to the variety of circumstances that exist around the world. This is especially true for agricultural practices, which have to respond to differences in climate, soils, and ecosystems, and are an integral part of cultural diversity” ("The Food and Agriculture Organization", n.d.). Taking into consideration the complexity involved in finding common practices around the world international environmental and social standards are more often applied as general standards or guidelines to develop a framework that can be applied in the local context and furthermore specified by local standard-setting or certification bodies (ibid).

The use of standards can be both voluntary and mandatory. Mandatory standards usually refer to national or even international standards that are implemented through policies by governmental bodies. As described by the ISO: “under the World

Trade Organization (WTO) rules, governments are required to base their national regulations on standards produced by organizations like ISO and IEC, as much as possible” ("International Organization for Standardization", n.d.-b).

However, there can also be voluntary regulation. According to Vogel (2008) “this method of regulation, which has also been referred to as “civil regulation,” tends to deal with social and environmental impacts” (as cited in Matus, 2010, p. 86). It is closely related to the rise in corporate social responsibility (CSR) (Auld, Bernstein & Cashore, 2008). Additionally, advancement in technology has been one of the driving forces of keeping companies more accountable and demanding higher standards. Today consumers are more empowered to react very fast and move the information across the globe, therefore, punishing brands that have failed to reach their expectations (Matus, 2010). Further Matus (2010) suggest that standards have to be notable, credible and flexible. The standards must have notable enough impact, credible in regard to how believable it can be observed, measured and reported upon and finally flexible enough to that new knowledge or goal can be incorporated (ibid). Sustainability, for example, is an ongoing process of development and therefore require adjustments along the way to meet the current challenges and utilize available solutions.

Accreditation

According to The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) accreditation is defined as “the formal recognition by an independent body, generally known as an accreditation body, that a certification body operates according to international standards” ("The Food and Agriculture Organization", n.d.). This means that if the certification body wants to implement a new standard in their certification program, they first need to be evaluated and accredited by an authoritative body. The accreditation process will then ensure that the certification body has the capacity to carry out certification programmes and whether the specific standard used by the certification body is in line with the generic standard and whether they are satisfied with the method of verification.

Certification

Certification can be seen as a form of communication along the supply chain, through developed standards that have been inspected and verified by a third party without a direct interest in the economic relationship between the supplier and buyer to assure the credibility of the data (The Food and Agriculture Organization, n.d.). Matus (2010) defines certification as “the process, often performed by a third party, of verifying that a product, process or service adheres to a given set of standards and/or criteria.” As suggested by the International Standard Organisation (n.d.-b) certification can be seen as “a useful tool to add credibility, by demonstrating that your product or service meets the expectations of your customers”. Further adding that depending on the industry in some cases certification is a legal or contractual requirement (ibid).

The organization performing the certification is called a certification body (CB) or certifier (ibid). As the Food and Agriculture Organization (n.d.) explains “the certification body might do the actual inspection or contract the inspection out to an inspector or inspection body”. Further adding that “the certification decision, i.e. the

granting of the written assurance or "certificate", is based on the inspection report, possibly complemented by other information sources” (ibid).

The certification process is not just a one-time interaction between auditor and auditee, rather as suggested by Matus (2010) a continuous relationship. Further adding that certification process can also introduce sanctions and penalties such as denying the right to use the label of the certification, thus keeping companies more accountable and stress the importance of complying.

Labels & Eco-labels

While the certificate can be seen as a tool to communicate between seller and buyer, the label, on the other hand, is a tool to communicate efforts and quality of the product to the end consumer. From a consumer perspective as Matus (2010) describes “labels have become increasingly common in relation to information regarding nutrition, safety, and most recently, the environmental impact of a range of products” (p. 79). Thus, labels play an important role in driving consumer purchasing behaviour, not only in terms of quality but also in terms of driving more environmentally beneficial decisions (Testa, Iraldo, Vaccari & Ferrari, 2013; Van Loo, Caputo, Nayga & Verbeke, 2014).

As described by the FAO “a certification label is a label or symbol indicating that compliance with standards has been verified” ("The Food and Agriculture Organization", n.d.). Further adding that “use of the label is usually controlled by the standard-setting body. Where certification bodies certify against their own specific standards, the label can be owned by the certification body” (ibid). Perhaps more known examples come from the food and beverage sector such as FairTrade, Marine Stewardship Council (MSC), Coffee and Farmer Equity (C.A.F.E.) and others.

Today there are more than 460 ecolabels in 199 countries, and 25 industry sectors ("Ecolabel Index | Who's deciding what's green?", 2019). These statistics are two folded. On one hand, the growing number of ecolabels show consumers interest in making more conscious decisions. On the other hand, the rising number of eco-labels can also indicate the oversaturation in the certification industry and raise concerns about whether these labels hold value and are not just there for financial benefits. Therefore, for labels to effectively communicate these standards and reach the end consumers, they must be meaningful. As suggested by the FAO “consumers who base market decisions on the presence of a label need to be able to access information about the underlying certification and standards” ("The Food and Agriculture Organization", n.d.). In other words - the label should be transparent and trustworthy. End consumers should have a good understanding of what the label stands for and is not just an empty attempt to use greenwashing tools to increase the value of the product.

More recently, many other forms of transparency instruments have appeared, including online databases, scorecards, self-disclosure information systems, traceability platforms, independent local monitoring initiatives, and various forms of footprint calculators (Grimard et al., 2017). All those tools open new possibilities to use technology in eco-label certification for sustainability and improve transparency practices.

1.5.

Research problem

Certification companies in the sustainability sector carry great responsibility in driving sustainability, end consumers rely at first instance and often only on eco-labels for their ethical decisions when selecting one product or another, but not only consumers, several actors in products supply chains depend on transparency and reliability of their data to assure and communicate the quality, social, environmental or ethical integrity of a product. Further, certification companies have not been extensively researched in the literature, a comparative study performed by Heras, Casadesús and Dick (2002) found that most articles covering certifications and their business value were either anecdotal, case study based, or report only descriptive statistics, and so their industry practices are not fully understood by the end consumer, leading to misconceptions and lack of information.

Emerging technologies such as Blockchain and IoT are available today bringing properties of transparency, traceability and reliability of data. Their implementation in the certification sector would greatly benefit certification providers by improving transparency and traceability in the supply chains, which would in result benefit the end consumer but, despite the potential of the technology, companies in the certification industry are reluctant to change and adopt the technology.

To introduce new technology in a long-time established company is often faced with resistance which may come from different sources. Even if in the long term it does make sense for the company to implement such technology due to the many benefits provided. Companies failing to adopt new technology may find themselves falling behind the market, affecting their operations, impact and profit, thus the barriers to adopting such technologies must be overcome. Without these new technologies providing transparency and traceability in the sustainability sector, the end consumer can be overwhelmed by the different eco-labels in the market, creating vulnerability to be exposed to greenwashing practices by companies to maximise their financial profits and losing value towards the companies that do have sustainability in their daily practices.

To summarize, emerging technologies such as IoT and blockchain provide new opportunities to increase traceability and transparency in the certification industry, however, these technologies are not widely adopted across the industry thus raising the question of what the barriers of are adopting the new technologies.

1.6.

Purpose and aim of the research

The purpose of this research is to explore what is preventing certification companies in the sustainability sector to adopt new technologies that increase the quality, transparency and traceability of data when addressing a supply chain, like QR codes, IoT or Blockchain and to promote its use. This research aims to provide knowledge on motivations and barriers faced by certification companies and organisational strategies that can be applied in order to facilitate technology adoption.

Main RQ: How can certification companies overcome their barriers to new

technologies, and allow them to improve quality, transparency and traceability in their certification practices?

To answer the main research question, the research needs first to investigate the current practices in the certification industry, what are their motivations to adopt new technologies to improve transparency and traceability and what barriers they face for its adoption. With this aim, three preliminary research questions are formulated:

RQ1: What is the current status of transparency and traceability methods in

certification processes?

RQ2: What motivates certification companies to adopt new technologies? RQ3: What prevents certification companies to adopt new technologies?

2. Theoretical Background and Analytical framework

This chapter presents existing theories and models developed by researchers in the field of organisational change and motivational studies. These theories form the basis for answering the research question, with motivational models illuminating the aspects of technology adoption in sustainable certifications and organisational strategies proposing methods to produce a change. The chapter ends with a unified model of motivational theories to visualise how factors influence technology adoption.

2.1.

Organisational Strategy and Change

Most research on organisations agrees on the fact that change is unavoidable (Tolbert & Hall, 2009). Child and Kieser (1981) mention that “Organizations are constantly changing. Movements in external conditions such as competition, innovation, public demand, and governmental policy require that new strategies, methods of working, and outputs be devised for an organization merely to continue at its present level of operations. Internal factors also promote change in those

managers and other members of an organization may seek not just its maintenance but also its growth, in order to secure improved benefits and satisfaction for themselves” (p. 28). Companies need to change in order to adapt to new practices which were not considered in the early stages of the company strategies. Those changes can be motivated by many reasons, including a new technology in the market filling a need, or improving an already established method. It is very important to keep in mind that organisational change does not happen in a single day, it is a process.

Organisational change can be episodic or continuous, depending on the time frame of the change (Weick & Quinn, 1999). Episodic changes are produced in a single moment of time when a change needs to be implemented in order to move away from a stable situation towards another, these changes tend to be infrequent, discontinuous and intentional. From the other side, continuous changes are ongoing evolving changes that tend to group together to produce a bigger change and often related to small improvements in organisational processes (ibis). An example of episodic change would be the transition from the use of technology in an organisation towards adopting a different one, while a continuous change would be the continuous improvement of a technology already in use by the organisation by including small periodic updates.

Any change in an organisation starts with its strategy. Strategies affecting user behaviour are often linked with psychology and then creating methods to produce change by influencing managers, decision-makers and relevant stakeholders. These psychological strategies to produce change within an organisation have been listed by Furnham and Gunter (1994) and are classified into seven categories (Furnham & Gunter, 1994 in Furnham, 1997):

The fellowship strategy: This strategy relies on improving interpersonal

relations and long discussions to produce a change in consensus. A ‘friendly’ approach is taken when addressing others and everyone is treated equally, no matter the level of hierarchy in the organisation. It is, however, difficult to produce change with this strategy as it avoids conflict, which can lead to miss critical issues and waste time.

The political strategy: This strategy relies on the power of individuals,

managers, leaders, and decision-makers to produce a change by influencing their behaviour individually. It is a shady strategy as it attempts to fulfil individual agendas to reach the goal, which may be contrary to the values of the organisation. At the same time, it produces a weak change, due to shifts in management positions and not involvement of the rest of the organisation.

The economic strategy: This strategy believes that money is the best

persuader and that a change in someone's salary or incentives will change the behaviour to reflect the values of the new culture to be adopted. However, this strategy ignores the emotional perspective and all values beyond the economic bottom-line and should not be applied if the organisational culture has any other values than money.

The academic strategy: This strategy believes that information, or rather

enough information and facts, can change the opinion of people. It uses studies, reports and any findings that can trigger a reaction and produce change. This strategy may take a long time to collect and analyze the data, having the risk of becoming irrelevant or outdated.

The engineering strategy: This strategy assumes that if the way of doing things

change, then people will change as well. It focuses on what, how and why, but uses to fail on the communication aspect. It is a limited strategy as, frequently, only a few people understand the change, can create unhappiness and may fail to commit most of the people.

The military strategy: The strategy relies on brute force. The focus is on

fighting the current situation to change it by any means, where a strict plan has to be followed and there is no room to relax. This strategy is normally faced with the same force in the opposite direction, and the result is an ever-escalating conflict. It can only work during a crisis.

The confrontational strategy: This strategy assumes that if you fuel people’s

anger, they will rise to change the situation. It is a complicated strategy as it should not end in violence and encourage people to face problems they may not want to, creating a backlash. It tends to focus too much on problems and less on solutions.

The way of working with these strategies is not to use one or the other, but to combine them depending on the situation and match the best methods according to the step in the change process (Furnham & Gunter, 1994 in Furnham, 1997).

2.2.

Motivation on the adoption of new technologies

The motivation to adopt new technology is a topic studied in many types of research (Taherdoost, 2018). In order to understand these motivations, academics have developed several frameworks and models that deal with the user acceptance of new technologies and its factors:

Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA): Although this theory was developed as a

general behaviour theory, it is considered one of the first to frame the motivation to adopt new technologies. The theory considers the user pre-existing attitude towards the technology and the user subjective norms to analyse the user willingness by understanding the initial motivations to adopt the technology (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975). This theory considers that the user is already motivated to adopt the technology (or, as a behaviour theory, to perform an action) and so presents many limitations on its use.

Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB): This theory is developed as an extension of

TRA, by adding perceived behavioural control in addition to pre-existing attitude and subjective norms to shape the user behaviour (Ajzen, 1985). Perceived behavioural control considers the availability and perceived the need of resources, opportunities and skills to adopt a technology, which enhances the

model beyond the individual intention, but relies on those resources, opportunities and skills in order to be relevant.

Technology Acceptance Model (TAM): This model is developed from TRA and

takes into consideration the user acceptance based on how the technology is designed to fulfil two factors: perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use (Davis, 1986). Those factors are considered to be directly linked to the user attitude towards using the technology and so affecting the behavioural response towards actually using the technology but, as it does not take into account external factors like social influence, it has limitations to be applied in a large scale, and it mostly used within a company or organisation, losing relevance at a large scale (Taherdoost, 2018).

Social Cognitive Theory (SCT): This theory considers a triangle model of three

groups of factors: personal factors (cognitive, affective and biological), behavioural factors and environmental factors (physical and social) that interact and are continuously influenced between them (Bandura, 1986). The theory assumes three behaviour patterns for user acceptance of new technology stated as outcome expectations, emotional reaction, and self-efficacy (Momani & Jamous, 2017). The theory limitation lies in the fact that it is not fully understanding which of the factors is more influential than the other.

Model of PC Utilization (MPCU): This model is developed from TRA but removes

the pre-existing attitude towards technology, while adding habits, and facilitating conditions to user feelings, social norms and expected consequences as the factors affecting user behaviour (Thomson, Higgins & Howell, 1991). This model intends to analyse the current use of technology-based on habits of use but requires the right personal profile for the technology, the “job fit” (Momani & Jamous, 2017).

Motivational Model (MM): This model is developed from the Self-Determination

Theory (SDT), which states that “self-determination is a human quality that involves the experience of choice, having choices and making choices” (Deci & Ryan, 1985). MM contains two groups of factors to explain user behaviour: extrinsic motivation factors, and intrinsic motivation factors (Davis, Bagozzi & Warshaw, 1992). The extrinsic factors are represented by SDT self-determination as external, introjected, identified and integrated form of regulation, while the intrinsic factors refer to intrinsic regulations (Momani & Jamous, 2017). In other words, external motivations are related to how useful is the technology while internal motivations are to how enjoyable is its use. This model is useful for learning and motivational studies, but it is too broad to be considered effective in technology acceptance studies (Parijat & Baggan, 2014).

Diffusion of Innovation theory (IDT): This theory takes into consideration that

some people adopt new products or behaviours sooner than others. The theory identifies five different adopter groups based on how early or how quickly users adopt an innovation: innovators, early adaptors, early majority, late majority and laggards (Rogers, 2003). The theory explains that each adopter group needs to be treated differently using distinct communication channels and messages in order to adopt the technology.

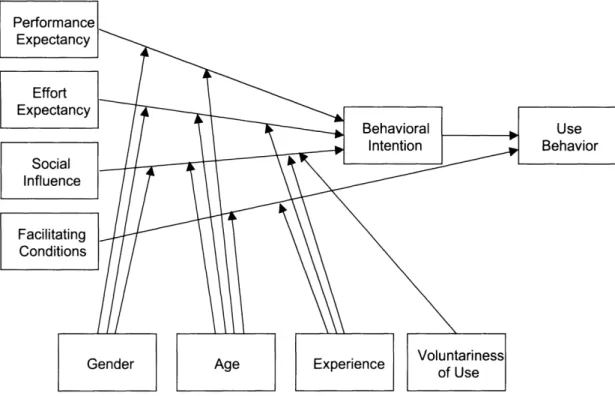

The listed motivational models and theories have been widely researched in the literature, improved over time and faced against many user cases (Taherdoost, 2018), however all of them present flaws and limitations. In order to overcome their limitations, Viswanath et al. (2003) studied the issues in the existing technology adoption motivation models from various dimensions combined the previous theories and models to create a unified theory to profit the benefits while removing the flaws, called Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT).

2.3.

Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology

The integrated model created by Viswanath et al. (2003) considers effort expectancy, performance expectancy, social influence and facilitating conditions as factors affecting user behaviour, while including four variables to tailor up the specific case, being these: gender, experience, age and voluntariness of use (Taherdoost, 2018). These four groups of factors or constructs considered in UTAUT to explain user behaviour are explained as following (Sullivan, 2012):

Performance expectancy: How much a user expects the technology to improve

its quality of life, work performance or status. This construct takes perceived usefulness from TAM (and TAM2, C-TAM-TPB), extrinsic motivation from MM, job-fit from MPCU, relative advantage from IDT and outcome expectations from SCT (Viswanath et al., 2003). Those factors have many similarities being easy to group them in the same construct. Gender and age play a moderating role in performance expectancy, although studies have shown that gender is influenced by psychological factors and society and its bias can change over time (Kirchmeyer, 2002).

Effort expectancy: How much a user expects the technology to be

user-friendly, easy to use. This construct takes perceived ease of use from TAM (and TAM2), complexity from MPCU and ease of use from IDT (Viswanath et al., 2003). Effort expectancy is a relevant construct for both mandatory and voluntary schemes, and especially significant just after the technology is discovered or the user has been trained on it. According to Morris and Venkatesh (2000), gender, age and experience play important roles in effort expectancy.

Social influence: How much a user expects the technology to be influenced by

people in the user environment, and their social acceptance. This construct is present in technology acceptance models as subjective or social norms, like TRA, TPB, TAM, MPCU and IDT, plus expansions of those models like TAM2, DTPB or C-TAM-TPB (Viswanath et al., 2003). Social influence affects user behaviour with three factors: compliance, internalization and identification (Venkatesh & Davis, 2000). Compliance, or voluntariness, in social influence, is found to affect user behaviour when technology adoption is perceived to be enforced by rules, as the user may be unwilling to comply with a mandate that feels like an order without previous consultation (Hartwick & Barki, 1994). Internalization is found to affect user behaviour in the sense that, once the

user believes in the importance of technology, it takes motivation as its own (Kelman 1958, Warshaw 1980). Finally, identification refers to the idea that technology adoption will improve the user image among the social group (Moore and Benbasat, 1991). However, these factors should only be taken into account at an early stage of technology adoption, as experience provides a more suitable influence over time. Age and gender have to be considered for social influence as well, while voluntariness is key for social influence as being related to internalization and identification, the motivation to adopt the technology is not much affected by social influence if the voluntariness to use is high.

Facilitating conditions: How much a user believes to have the right conditions

to adopt the technology, in knowledge, organisational structure, infrastructure and resources. This construct is present in TPB as perceived behavioural control, in MPCU as facilitating conditions and in IDT as compatibility (Venkatesh et al., 2003). All these factors are intended to remove barriers for technology acceptance and incorporate items to facilitate technology adoption but do not directly affect the user motivation, only the technology use.

Performance expectancy, effort expectancy, social influence and facilitating conditions are considered as independent factors that affect the dependent variables of behaviour intention and use behaviour, while gender, experience, age and voluntariness of use affect indirectly the dependent variables via the main factors. The user behaviour intention is considered as an entry point to technology acceptance (Venkatesh et al., 2003).

Figure 5: UTAUT model (Viswanath et al., 2003)

Despite its completed integrated model, UTAUT still presents some limitations when addressing different contexts. Gahtani, Hubona and Wang (2007; in Liu, 2013) tried to implement the model in Saudi Arabia and found out that cultural differences made it very difficult to follow the same patterns described in UTAUT theory, creating a resistance to the new technology. Also, Maldonado et al. (2010; in Liu, 2013) had to modify the model for their research in Peru and include different levels of social-economic status based on three regions, as the influence of factors were very different. These limitations of UTAUT need to be considered when working outside western countries, and cultural factors should be considered in further iterations of the motivational model.

2.4.

Analytical Framework

The described theories form the analytical framework of the research. Through UTAUT motivational model and its factors, the researchers identify what moves companies to adopt a technology, as well as finding what they may have missing in their organisation to trigger a behavioural intention, mostly in decision-makers, for the user acceptance of the technology. Once the factors are identified and related with certification companies’ motivations and barriers, organisational strategies are suggested in order to overcome the barriers and produce a change towards technology adoption for transparency, increasing the visibility of their eco-labels as well and their traceability to ethical sourcing and sustainable practices. The strategies are finally mapped with motivations and barriers to identify the most fitting strategies and recommend future research in that direction.

3. Research design

The following chapter describes the practical approach taken towards the data collected for the purposes of further analysis in this paper. The selection of research design and process for data collection is discussed to reveal the motivations for the methodological choices made in relation to the stated research questions. Justification for the design of the interview guide as the instrument for collecting data is given as well as the limitations of the method.

3.1.

Research Strategy and Approach

The study has been designed to take an inductive approach where hypotheses and conclusions are based on the observed behaviours and collected data. This approach aims to generate meanings from the data set collected to identify patterns and relationships to build a theory or make conclusions (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill, 2012). The inductive approach does not prevent the researcher from using existing theory to formulate the research question to be explored.

3.2.

Research Method

The research is conducted through qualitative research methods with the exploratory purpose to better understand the state of the certification industry in the context of sustainable development and the underlying challenges. According to Brown (2006), Silverman (2011), Hart (2018), 6 and Bellamy (2012) a qualitative method is a good method when researchers need to investigate in-depth and get a deeper understanding of a topic. An explorative purpose is an approach where the researcher can satisfy her or his curiosity, provide a better understanding, or for general interest (6 & Bellamy, 2012; Hart, 2018). A naturalist perspective has been chosen to capture authentic experience and insights of the subject's experiences within the industry such as values, beliefs and behaviour (Silverman, 2015).

This study uses primary and secondary data to collect relevant information and answer the research questions. Primary data is collected directly by researchers with interviews while secondary data is inspected conducting content analysis (Silverman, 2015). The gathered data will be separated into themes and codes. Additionally, precisely establishing categories and categorizing information to identify relations and patterns further. A good researcher knows how to use both primary and secondary sources in their writing and to integrate them in a cohesive fashion (Driscoll & Brizee, 2019).

3.2.1. Case selection

Certification industry is a complex system, that involves various actors and stakeholders in the processes. In order to investigate what are the motivations and barriers that certification companies see in the adoption of new technologies, 11 samples from different organizations were selected to perform qualitative research. Flick (2007) suggests that “taking sampling in qualitative research seriously is a way of managing diversity so that the variation and variety in the phenomenon under

study can be captured in the empirical material as far as possible” (p. 83). Since the study is investigating the certification industry as a whole, the first criteria for selecting samples were to represent various actors involved in the certification industry from around the world. Further, as suggested by Patton (2002) qualitative study aims at the maximal variation in the samples. Flick (2007) explains that this approach is looking to integrate only a few cases, but those that are as different as possible, to disclose the range of variation and differentiation in the field. Therefore, the second criteria for selecting samples interview representatives of various actors such as standard-setting bodies, certification bodies, third party assurance companies and sustainable brands. Lastly, Flick (2007) suggests looking for people with a long experience with the issue and those who are really in a position to apply the professional practice we are interested in. Therefore, third criteria for sample selection aim at decision-makers, executives and managers.

3.2.2. Data collection

As part of the qualitative research, semi-structured interviews were chosen as the primary research method. The research conducts semi-structured interviews with selected participants from certification companies while parallel interviews are done in addition to the main interviews with participants from sustainable brands and transparency advocates to get a deeper understanding of the current needs in transparency and traceability. Conducted conversationally with one respondent at a time, semi-structured interviews are conducted employing a blend of closed- and open-ended questions, often accompanied by follow-up why or how questions (Adams, 2015). In this manner, the interviewee has a focus on the relevance of the research, at the same time with the possibility to expand on the subject when necessary (Gray, 2014).

Semi-structured interviews are highly valued in social research as can be adapted to almost any research question or hypothesis formulated while involving the interviewee into the topic of the research. Both practical and theory-driven questions can be formulated in a semi-structured interview, increasing the quality of the collected data grounded in the experience of the participant (Galletta, 2013). The process of the interview, when to ask the right questions and which questions to skip, requires time, trial and error as each interview address a different person, but all questions need to be connected to the purpose of the research while getting deeper into the topic.

The interviews aim to explore the predisposition of certification companies to adopt new emerging technologies, what challenges they faced in previous implementations and their opinion on the blockchain, IoT and QR codes, technologies that have demonstrated to improve transparency and traceability in supply chains, a core function of sustainable certifications. The interviews are performed with organisational members listed in Table 1.

Table 1: Overview of the interviewees Specific expertise Intervi ew type Media type

Certification bodies (CB)

A1 An international accredited registrar

Online Audio 60 mins Digital transformation

manager Norway A2 Certification

body for ecological products

Online Audio 45 mins General Manager Germany

Sustainable brands

B1 Organic

cosmetics brand Online Audio 30 mins CEO & Co-founder Lithuania

Standard-setting organization (SSO)

C1 Sustainability

CB/SSO Online Audio 45 mins Manager Germany C2 Natural and

ecological cosmetics CB/SSO

Online Audio 65 mins Manager Belgium

C3 Organic food

CB/SSO Online Audio-visual 60 mins Executive Director USA C4 Sustainability &

Environmental Certification Program

Online Audio 60 mins Operations & Finance

Manager Australia C5 Carbon

footprint off-setting CB/SSO

Online Audio 45 mins Managing Director UK C6 Food &

Beverage CB/SSO

Online Audio-visual 45 mins Data Program Manager USA C7 Organic food

CB/SSO Online Audio 45 mins General Manager UK

Transparency Advocates

T1 Fashion Transparency advocates

Online Audio

30 mins Policy and Research Coordinator UK T2 Open source

map and database organisation

Online Audio 35 mins Project Director USA

Governmental Agency

G1 Department of

In order to deliver both the reliability and validity of the research, an interview guide was created to deliver a consistent interview process. McNamara (2009), suggests eight principles for effective interview preparation: (1) choose a setting with little distraction; (2) explain the purpose of the interview; (3) address terms of confidentiality; (4) explain the format of the interview; (5) indicate how long the interview usually takes; (6) tell them how to get in touch with you later if they want to; (7) ask them if they have any questions before you both get started with the interview; and (8) do not count on your memory to recall their answers. These steps were applied before every interview to assure the quality and the experience of the interview for both hosts and participants.

Further, the process of semi-structured interviews was accommodated to cover a wide range of topics, thus the construction of the interview was adjusted based on the interviewee context. However, all interviews were hosted by both authors and followed the same structure: an opening segment, a middle segment and a

concluding segment, as suggested by Galletta (2013, pp. 46-50). An opening segment

was intended to form a level of comfort, establish basic information and create space for participants to narrate their experiences. This segment is focused on listening carefully to the unfolding story. The middle segment was divided into three sections:

Status quo of the industry, Supply chain and Transparency, Technology & change.

As the research intended to identify the motivations and barriers of adoption of new technology amongst certification companies, it was important to understand the relation of actors involved in the ecosystem to sustainability and collect the insights on the status quo of the industry. Further, both practical and theory-driven questions were used to address the challenges and opportunities of Supply chain and

Transparency, Technology & change. The middle segment continued with in-depth

questions to attend the nuances in the narrative thus far, while at the same time keeping space for more specific questions that relate to the research question. This part of the interview was designed to be more substantial in order to ask follow-up questions based on the ongoing discussion and then ensuring comprehensive interview data. Lastly, the concluding segment provided an opportunity for the interviewee to revisit topics that were not discussed previously, critically reflect on the subject and give further suggestions and ask the participant for additional thoughts and how they see the future of sustainability and technology.

All the interviews were conducted using online communication tools. This approach was taken since the research was looking to have a global scope and conduct a broad range of interviews with managers, decision-makers and leaders regardless of the location. Communications technology, such as Skype and Zoom, offered to have an audio-visual experience that simulated in-person environment (Hanna, 2012).

Finally, after the interview, the two interviewers gather notes documented during the interview, debrief by reflecting on the interview, exchange with impressions and suggestions for future perspectives. And prepare the audio recording together with notes for the content analysis process.

3.2.3. Data analysis

The purpose of exploratory research is to identify patterns and so conducting thematic content analysis is considered one of the best data analysis methods for this