Violent Rapists and Depraved Paedophiles: Linguistic Representation of

Sex Offenders in the British Tabloid Press

A comparative corpus-based study

Anne Blauenfeldt

English (linguistics)

Bachelor thesis

15 credits

Spring semester 2014

Supervisor: Jean Hudson

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT 1 INTRODUCTION ... 4 2 BACKGROUND ... 5 2.1MEDIA REPRESENTATION ... 5 2.2PREVIOUS STUDIES ... 72.3CDA AND CL APPROACH ... 9

4 DESIGN OF PRESENT STUDY ... 11

4.1CORPUS DATA ... 11

4.2CORPUS TOOLS... 12

5 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION... 14

5.1KEYNESS ... 15

5.2CATEGORIES ... 24

5.2.1 The perpetrator ... 24

5.2.2 The act ... 29

5.2.3 The societal perspective ... 35

5.2.4 The victim ... 38

5.3GENERAL DISCUSSION ... 40

6 CONCLUDING REMARKS ... 43

APPENDIX I ... 47

Abstract

Through a combination of corpus linguistics and critical discourse analysis, this paper looks at the hidden ideological discourses surrounding sex offenders in the British media. Corpus linguistics provides an excellent framework to discover such discourse patterns and the critical discourse analysis framework helps contextualise the findings. The specific aim of the paper is to discover and compare the discourse patterns surrounding the specific nominals

rapist* and paedophile* in order to see how the representations differ. The analysis

uncovered that the representation of both offenders was sensationalised and full of negative and emotionally loaded words. Furthermore, it was discovered that two differing discourses were prominent for each nominal: An animalistic and bodily discourse for rapist* and a discourse of deviance and the mind for peadophile*. Lastly, it is argued that these

misrepresentations are problematic as they misinform both the public and the regulation of offenders.

1 Introduction

‘All media exist to invest our lives with artificial perceptions and arbitrary values’

(McLuhan, n.d.)

It is an often-misconceived notion that media production is a simple process of journalists objectively reporting on events as they occur around the world. On the contrary, though, media representation is a powerful hegemonic process that shapes, and at the same time is shaped by, the discourses of which it speaks. Over the past decades, researchers from several academic disciplines have critically studied media representations of various social actors because the representation of these actors have been proven to shape public opinion as well as societal regulations (see for instance, Kitzinger, 1999; Meyer, 2010; O’Hara, 2012; Sinclar &

Wilczynski, 1999). In the case of sex offenders, rapists and paedophiles are the two distinct types often discerned between in the media and thus in the academic literature on sex offenders. Both these types have been found to be highly sensationalised and negatively represented by the media, which has direct consequences on the regulation of them. In the belief that the two offenders are generally viewed as two distinctly different types by society, this study will focus on the difference in the media’s representation of the two offenders. Through a combination of corpus linguistics and critical discourse analysis, this study will investigate and compare the media representation of rapists and paedophiles in the British press in order to see to what extent the ideological discourses around the two types of sex offenders differ. Several studies have previously shown how a combination of corpus linguistics and critical discourse analysis can be useful in discovering such ideological discourse patterns in newspapers (Baker et al., 2008; Gabrielatos & Baker, 2008; Caldas-Coulthard & Moon, 2010).

The main aim of this study is to investigate and compare the linguistic representation of rapists and paedophiles in the British tabloid press. More precisely, this study will investigate and compare the specific nominals rapist/s and paedophile/s. In fulfilling this aim, it is also necessary to look at other aspects, such as the representation of the perpetrator’s act and the victim, as these inevitably are part of the representation of the perpetrator.

Although the use of two specific nominals limits the scope of the study, the decision to do so was based on two following reasons: Firstly, a newspaper database search1 revealed that the two nominals were by far the most frequently used to denote the two types of offenders. This is in itself interesting, as they are both quite loaded terms. Other terms, such as sex offender and child abuser, for example, were much less frequent in comparison. Secondly, due to the comparative nature of the study, the use of the specific nominals is ideal. Including other terms, such as sex offender, in the data would have proven more difficult, as they are often used to refer to sex offenders in general and in other instances used to refer to a specific type of sex offender, e.g. a rapist or a paedophile. Because of the use of the specific nominals, it is important to note that it is not the concepts rape and paedophilia that are under investigation in this study.

The next section of this paper will present the theories of media representation in more depth and the relevance of linguistic approaches within the study of media

representation. This will be followed by a presentation of relevant previous studies in order to contextualise the results in the discussion as well as the reasoning behind the combination of the corpus linguistics and CDA methodologies. Next, the methodological framework of this study will be explained and presented in the form of applied corpus tools and data process gathering. The results will then be presented in a combined results and discussion section, which will be followed by a general discussion of the findings. Lastly, the findings will be summarised in the concluding remarks, which will also remark on the limitations of this study and points for further research.

2 Background

2.1 Media representation

Since the 1970s, media studies has become an established academic discipline in its own right. Both the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies and the Glasgow Media Group are considered pioneers in the development of media theory, and particularly their research into how the media represents the world (CCCS, n.d.; Glasgow Media Group, n.d.; Fowler, 1991). This theory of representation is based on the widely accepted belief that

1 NewsBank database search

there is an arbitrary relationship between the world we encounter (signified) and the mental concepts (signifier) we assign it. The relationship between the signified and the signifier is organised into codes (language being the most advanced code) in order to create meaning by categorising our mental conceptions of the world. For example, the difference between ‘vegetables’ and ‘fruit’ lies in our mental categorisation of edible things that grow in nature, and not in nature itself. The creation of meaning thus depends on these binary relationships, i.e. a vegetable is a vegetable because it is not a fruit (Fowler, 1991). In their research on how the media uses these codes to represent the world, the Glasgow Media Group have

particularly focused on the media’s ability to create and reinforce particular (and often negative) representations of certain social issues and social groupings in society, e.g. mental illness, AIDS and, most recently, on how the disabled and disability are represented in the British media (Glasgow Media Group, n.d.). The theory of media representation has been widely used within different academic disciplines over the past decades, here among linguistics. Linguists Roger Fowler and Norman Fairclough have both done extensive research into media discourse, and they both see the study of media representation and linguistics as natural companions (Fairclough, 1995; Fowler, 1991). While language, as established previously, is only one of the structured codes used in the creation of meaning, it is the central and most sophisticated code and thus at the core of representation. As Fowler (1991) argues, linguistics should be an essential contributor to the study of media

representation as semiotics was ‘the foundation of modern theories of representation’, i.e. Saussure, Whorf, Halliday etc. (p. 223).

Fairclough and Fowler both approach media representation from a critical linguistics aspect. They are both interested in the way the media uses language to represent the world because it has the ‘power to influence knowledge, beliefs, values [and] social relations’ (Fairclough, 1995, p. 2). The general perception of the media and journalists is that they are there to give an objective and unbiased account of the events they report on.

However, as Fowler (1991) argues, even though many journalists genuinely strive to report in an objective manner, there is simply no such thing as neutral or objective language; there will always be a set of mental categories, i.e. a certain ideology or world view, behind any written text or utterance that will inevitably result in a particular representation of the world.

Furthermore, he argues that the media’s representation of the world ‘reflects, and in turn shapes, the prevailing values of a society in a particular historical context’ (1991, p. 222). Fairclough (1995) similarly argues that all texts ‘will be simultaneously representing [and]

setting up identities’ (p. 5). Journalists, Fairclough continues, have the choice of how to represent when they report: They can choose what to background, what to foreground and which words to use when they categorise. However, these choices are rarely consciously made but shaped by, and at the same time shaping, the current discourses of which it speaks. When Fairclough uses the term ‘discourse’ here, it is meant to encapsulate both the linguistic sense of the word (language interaction), but also the Foucauldian sense of the term that sees discourse as a body of knowledge that is continuously (re)constructing that of which it speaks (Fairclough, 1995).

As critical linguists, Fairclough and Fowler are both concerned with the fact that the media has the power to represent and categorise certain groups of people, i.e. social identities, in a particular way through the medium of language. These social identities are a result of people’s mental categorisation process that categorises people into types, and according to Fowler (1991), this makes ‘the world presented by the Press […] a culturally organized set of categories, rather than a collection of unique individuals’ (p. 92).

Furthermore, these types often become simplified and essentialised to the extent that they turn into stereotypes devoid of any ‘individual features’ (Fowler, 1991, p. 92). Fairclough (1995) therefore stresses the need for more focus on ‘what sorts of social identities, of the ‘self’, [the media] project and what cultural values…these entail’ (p. 17).

2.2 Previous studies

The media’s representation of crime and sex offenders has been studied within various different disciplines such as sociology, criminology, psychology and media and cultural studies. In the existing literature, there is a clear cross-disciplinary concern over the media’s representation of sex offenders, in particularly paedophiles, and its various consequences (Muncie, 2001; Blood et al., 2009; Jewkes & Wykes, 2012; Sinclair & Wilczynski, 1999; Kitzinger, 1999). For example, Wilczynski & Sinclar (1999) analysed newspaper articles from both broadsheet and tabloid papers in Australia on the topic of child abuse. The authors conclude that the representation of child abusers is highly simplistic and sensationalised in the sense that offenders are individualised and portrayed as evil monsters without any social factors being taken into account. The individualised and sensationalised focus on the offender, they argue, is a worrying tendency because it leaves little focus on the prevention and

monster imagery of sex offenders in the media is a very serious issue. Firstly, it affects the public opinion on sexual offenders and thus other institutional processes in society such as legislation. Secondly, it creates an illusion that sex offenders are dangerous strangers when, in if fact, in most cases the offender is known to the victim. They conclude that the debate on sex offenders needs to be informed by academic and empirical research as the current perception and handling of sex offenders is beneficial to neither the victim nor the offender.

As noted previously, Fairclough and Fowler both state that there is a lack of linguistic studies in the domain of media representation, and in the case of sex offenders, they are almost non-existent. Two exceptions are the following: one on the media representation of paedophiles and one on the media representation of rapists. Meyer (2010) has partly used discourse analysis to examine the representation of paedophiles in one broadsheet newspaper, the Guardian, and one tabloid newspaper, News of the World, and partly examined to what extent this representation is influencing the regulation of paedophiles. Meyer identifies three main discourses in her analysis: The first one is the discourse of ‘evil’ in which the

paedophile is demonised through the lexical item evil and animalistic lexical items such as

predator, prey, monster, beast etc. Both newspapers use the discourse of ‘evil’; however, it

was much rarer in the broadsheet newspaper than the tabloid newspaper, which in turn used it in a more individualised and sensationalist manner. The second discourse Meyer identified is the discourse of ‘perversion and pathology’, with lexical items such as pervert, sick and vile indicating and shaping the paedophile’s sexuality as deviant. This discourse was found in both newspapers, although in the tabloid newspaper paedophiles were generally represented as incapable of change, whereas the broadsheet newspaper was less moralistic and often represented paedophilia as pathological and thus as a curable illness. The third discourse identified, and found equally in both newspapers, is ‘cunning’ which, contrary to the dehumanising animalistic discourse, ‘constructs paedophiles as meticulously and carefully planning their actions’ (p. 203). Lexical items such as online, grooming, lure and trap represent the paedophile as someone who uses strategic methods to gain access to children, i.e. online, at schools, through particular jobs or by ‘grooming’, which is a term used about paedophiles who befriend children or their parents with the intention of sexually abusing them. Meyer argues that the three discourses represent the paedophile as a dangerous stranger because the paedophile is both perverted, evil and animal-like but at the same time ‘the discourse of cunning restores human-ness to the paedophile by [representing them as having a] distinctly rational and cognitive form of behaviour’ (p. 205). Meyer concludes that these

discourses surrounding paedophiles are an issue because they represent the paedophile as a deviant stranger outside society and thus neglects the fact that offenders in most cases are ordinary men known to the victim. Furthermore, she concludes that it is problematic that the misrepresentation shapes the regulation of paedophiles and disregards the social issues behind paedophilia.

In the second study, O’Hara (2012) carries out a quantitative lexical analysis of the media coverage of three different rape cases: one case of stranger rape in Britain and one of gang rape and one of serial date raping both in America. Based on her findings, O’Hara argues that in most cases the media sensationalises and misrepresents rape. She found that lexical items such as predator, preying, sick, monster, evil, and beast were often used to represent the rapist’s act or mental state and that there was little focus on the offender’s social background. The offenders were often foregrounded and individualised, whereas the victim was often backgrounded or at times to blame for the rape due to attire or alcohol

consumption. Furthermore, similarly to Meyer, O’Hara concludes that the misrepresentation of rape in the media is problematic because it makes rape out to be isolated incidents

committed by deviant perpetrators and, consequently, the actual social issues behind rape are neglected.

2.3 CDA and CL approach

At this point, it is important to establish how this study intends to conduct a critical corpus linguistic-based study by incorporating aspects of the CDA framework in a similar manner as Baker et al. (2008) propose when they argue that a combination of aspects of the CDA and CL frameworks can help eliminate weaknesses that are often the object of criticism for both approaches.

Corpus linguistics is traditionally seen as a mere computerised methodology used to carry out quantitative analysis on large amounts of language data through various statistical measures and tools such as frequency, keyness and concordance (these will be expanded on in the following section) and in the process also disregards context; however, Baker et al. (2008) argue that this view of corpus linguistic often found within academia is a misconception as well as a simplification. Frequency and keyness are both tools that can help the researcher discover initial patterns and topics embedded within the data. These initial patterns and topics can then be further examined through concordance analysis which allows

the researcher to view a given search term in its textual context from a few words on each side of the search term to the whole text, if required. Concordance analysis thus enables the

researcher to contextualise findings in a more quantitative manner. In addition, one of the main strengths of the CL methodology lies in its ability to reduce researcher bias. That is, selectivity and the representativeness of the data are rarely questioned since corpora usually consists of hundreds and sometimes even thousands of texts (Baker et al., 2008)

However, as Baker et al. (2008) argue, ‘[a] traditional corpus-based analysis is not sufficient to explain or interpret the reasons why certain linguistics patterns [are] found’ and ‘[c]orpus analysis normally [does not] take into account the social, political, historical and cultural context of the data’ (p. 293). Therefore, aspects of the CDA framework can be useful in a CL-based study. In CDA, language is viewed as a social practice that both establishes and maintains ideologies, and thus unequal power relations, in society; CDA linguists are interested in uncovering these ‘structural relationships of dominance, power and control’ language in use creates (Baker et al., p. 280). Since its conception, CDA has been an interdisciplinary approach as it draws on theories and concepts from different disciplines (e.g. anthropology, cultural studies, philosophy history etc.); moreover, social, historical and political aspects as well as text-production and text-reception are usually also considered in order to contextualise the social phenomena under linguistic examination. These aspects of CDA can help strengthen a corpus-based study, as it becomes more than a purely descriptive analysis. Furthermore, CDA’s methodological framework is generally qualitative because CDA linguists often conduct in-depth text analysis of small amounts of selected data in order to establish which linguistic concepts and strategies are used, such as metaphors, topoi, speech acts, (de)legitimisation strategies, implicatures etc. (Baker et al., 2008). Thus, CDA’s theoretical categorisations of linguistic findings can be a very helpful tool for a corpus-driven analysis. As Baker et al. (2008) argue, although a ‘CL analysis does not set out to examine existing CDA notions, it can utilise a CDA theoretical framework in the interpretation of the findings’ (p. 285), e.g. grouping keywords and collocates into CDA categories such as metaphors.

With the proposal for a synergy of the CDA and CL frameworks in mind, this study will attempt to conduct a critical CL-based study by drawing on some aspects of the CDA framework. The discourse surrounding rapists and paedophiles will be analysed with CL tools such as frequency, keywords, clusters and concordances and make use of categories of analysis from CDA to categorise findings, e.g. metaphors and topoi. Furthermore, CDA’s

view that discourse(s) is a form of social practice that simultaneously shapes and is being shaped by societal ideologies and thereby constructs a certain reality that some have more power to shape through discourses than others, is the underlying train of thought at the base of this study. Theories of media representation as well as previous studies from different

disciplines will be taken into account in order to both contextualise and interpret findings; as Baker et al. argue, CL ‘findings need to be interpreted in the light of existing theories’ (2008, p. 296).

4 Design of present study

This section will present both the data retrieval and the corpus building process, followed by a description of applied corpus tools and their application in the analysis of both corpora.

4.1 Corpus data

Two corpora were built for this study: one comprised of British tabloid news articles about rapists and one with articlesaboutpaedophiles. The articles were collected from the online newspaper database Newsbank by typing in the search term ‘rapist*’ and retrieving three articles from each month of the year from the years 2013 back to 2010. Each article was then copied and pasted into the programme Notepad and saved as a .txt file. The same procedure was then repeated with the search term ‘paedophile*’. The aim was to reach an equal number of words in each corpus in order to be able to make direct comparisons between the two corpora and by using raw frequencies instead of having to turn to mathematical calculations. The articles about paedophiles were generally longer than the articles about rapists; therefore, the articles retrieved for the paedophile corpus (referred to as PAEDO henceforth) stops at November 2010, whereas additional articles from 2012 and 2011 had to be added to the rapist corpus (referred to as RAPE henceforth) to secure an equal number of words in each corpus. The finished RAPE corpus consisted of 162 articles and 70.116 running words, and the finished PAEDO corpus consisted of 141 articles and 70.414 running words. At this point, the reader is reminded that this study is not looking at the concepts of rape and paedophilia, but the linguistic construction of the specific nominals rapist/rapists and paedophile/paedophiles. Therefore, the search terms used where rapist* and paedophile* and not rape* and

Two things should be noted at this point: Firstly, seeing as this is not a diachronic corpus study, it would have been ideal to collect the most up-to-date data as possible. In this case, to start with the most recently published news article and work backwards from there until adesired word count was reached. However, this approach resulted in huge quantities of similar news articles concerning the rise (or rise in coverage, more like) of gang rape in India in the RAPE corpus. Therefore, in order to ensure a more varied and comparable corpus, it was decided to collect data from December 2013 to January 2010 instead. Secondly, the decision to investigate the representation of rapists and

paedophiles in tabloids was based on a report released by the National Readership Survey in March 2014, which concludes that tabloid newspapers have a larger and broader readership than broadsheet newspapers in the UK (Reid, 2014). Previous research suggest that

broadsheet newspapers are less sensationalising and simplistic in their style (Meyer, 2010; Sinclair & Wilczynski, 1999); however, it would nevertheless be interesting to conduct the same comparative study with broadsheet articles to see how the representations in these differ.

4.2 Corpus tools

Both corpora were analysed using WordSmith Tools, version 4 (Scott, 2004). The Wordsmith Tools program offers several tools to analyse corpus data. The corpus tools applied in this study were wordlist creation, frequency, keyness, patterns, concordancing and collocation. The two first mentioned tools do not require further explanation; however, keyness, concordancing, collocation and patterns will be defined below.

Keyness, as Baker (2006) explains it, ‘examines words which occur in a text or corpus more often than we would expect them by chance alone’ (p. 151). That is, when two corpora’s wordlists are compared to one another, a certain number of words (depending on the setting) will be key in one corpus and not the other. These words are known as positive keywords.

Concordancing is ‘a list of all the occurrences of a particular search term in a corpus, presented within the context that they occur. Usually a few words to the left and right of the search term’ (Baker, 2006, p. 719). The words on either side of the search term can be sorted alphabetically, which makes it easier to spot linguistic patterns around a given search term (Figure 1). Additionally, concordancing brings an element of CDA into a corpus analysis

as the concordance lines can span from a few words on each side up to the whole text. This gives the researcher the ability to see a given search term in its wider context, if necessary.

Figure 1. Concordance lines of the search term he2

Concordancing is a useful tool to spot linguistic patterns and words that collocate with each other. According to Baker, words that frequently co-occur close to each other are called collocates and this relationship between the words is referred to as collocation. Baker adds the following about the significance of collocation:

When two words frequently collocate, there is evidence that discourses surrounding them are particularly powerful – the strength of collocation implies that these are two concepts which have been linked in the minds of people and have been used again and again […] Collocates can therefore act as triggers, suggesting unconscious associations which are ways that discourses can be maintained.

(Baker, 2006, p. 114)

A very manageable way of getting an overview of the words which collocate with a given search term is to look at collocation patterns in the concordancer. The collocation pattern for the word he3 in Table1. illustrates this well: The five columns on either side of the search term show which words collocate most frequently with he. Column R1, for example, clearly shows several verbs denoting actions carried out by he, such as raped, added, admitted,

attacked and forced, and similarly column R2 shows verbs denoting an action happening to he, such as jailed, arrested, convicted and released. With other search terms, for example

nouns, column L1 and L2 are most likely to show adjectives that describe the search term.

Table 1.Collocation pattern for he

5 Results and discussion

The results and discussion will be presented in two sections: In the first section, the keyness analysis will be presented, followed by a brief examination of the four categories derived from the keywords, and in the second section, an in-depth examination of these four categories will be presented. As mentioned in the method section, since the corpora are of

3 Randomly chosen pattern for illustration’s sake

N L5 L4 L3 L2 L1 Centre R1 R2 R3 R4 R5

1 THE THE THE THE WHEN HE WAS A TO A THE 2 TO TO IN AND AS IS THE A TO TO 3 AND AND TO IN THAT HAD HER THE IN A 4 OF A A TO AFTER HAS TO FOR THE IN 5 A OF HIS A SAID SAID BE IN AND AND 6 HE IN OF YEARS BUT WOULD JAILED OF OF OF 7 IN HE AND HIS AND RAPED NOT HIS HE HE 8 WAS FOR HE HIM WHERE WILL BEEN BE FOR WAS 9 HIS ON WAS OF IF COULD HIS HE HIS FOR 10 FOR HIS WITH WAS BECAUSE ADDED IN ON HER HIS 11 HIM WAS FOR HE HER ALSO ALSO AND WITH YEARS 12 ON AT HER SEX SAYING DID ARRESTED HER ON I 13 BE HIM ON FOR WHAT MAY CONVICTED AT THAT ON 14 HER HER FROM LAST HIM ADMITTED HE AS WAS HER 15 I AN IS WITH BEFORE WENT RELEASED FROM VICTIM THAT 16 WITH BE AN TOLD COURT ATTACKED ME BEEN BE BE 17 BUT BUT AS HER YEAR FORCED ON ME AT WITH 18 AN HAD BE COURT ME THEN OUT AWAY YEAR AT 19 HAD WITH SHE ME HOW TOLD THIS AN LIFE HAS 20 POLICE MAN TOLD RAPE ASSAULT STARTED NEVER NOT RAPE BUT 21 WHEN BY IT SAID RAPE CARRIED FOUND IS INTO SEX 22 AS IT NOT THAT CLAIMED MUST HAVE BUT BUT AS 23 AT WHEN TWO IT TIME GAVE HIMSELF WAS HAVE POLICE 24 NOT AS AT MONTHS HAIR GOT AT WHEN NOT MY 25 MORE THAT HIM BUT LATER POSES NO BY ME FROM 26 BECAUSE NOT SAID IS KNEW WANTED AND UP TWO YEAR 27 JAILED I I I BELIEVE GRABBED GIVEN OUT HAD UP 28 THIS AFTER YEARS ON ALTHOUGH DESERVES NOW I BY JAIL 29 ONE WHO EIGHT POLICE AGAIN COMMITTED THAT GUILTY AN HOME 30 OUT THAN THAT BEEN VICTIM LEFT WEARING CONVICTED MADE BEFORE 31 THEN FROM DURING WOMAN SAY SHOULD SAID YEARS SHE PRISON 32 THAT THREE STOP OUT PLEADED SENTENCED WITH RISK OTHER

equal size, the findings in the second section will generally be presented in the form of raw frequency (as opposed to percentages). The findings will be discussed as they are presented and will be followed by a general discussion of the overall findings and a comparison to Meyer and O’Hara’s linguistic studies.

5.1 Keyness

The first step in the analysis of the two corpora was to examine keyness. In a comparative corpus study such as this, keyness makes an excellent starting point for analysis because it provides a list of words that are characteristic for each corpus (Scott, 2004). Wordlists were created for each of the corpora in order to generate lists of keywords. In Wordsmith ‘[t]he default setting of 3 mentions as a minimum [for keywords] helps reduce spurious hits […] For example, a proper noun such as the name of a village will usually be extremely infrequent in [one] corpus, and if mentioned only once in [the other corpus], it is likely not to be "key"’ (Scott, 2004). At first examination, there was a reasonably clear indication of a pattern in the keywords, so it was decided to keep to this default setting. The positive keywords (apart from a few grammatical words) from each corpus were then examined by concordancing each word. As Baker (2006) argues, it is necessary to examine keywords qualitatively; otherwise, any initial theory based on the keywords will remain theory. Upon examining the keywords, it was discovered that a large part of the keywords could be grouped into one of the four

following categories:

The perpetrator

The act

The societal perspective

The victim

Each category was subsequently examined in depth by concordancing and examining both wordlists and collocation patterns. All of the corpus tools were used interactively. That is, they were continuously used back and forth to investigate the four categories. Furthermore, throughout the entire analysis, all of the concordance lines for a given search term were checked manually to ensure the accuracy of the results.

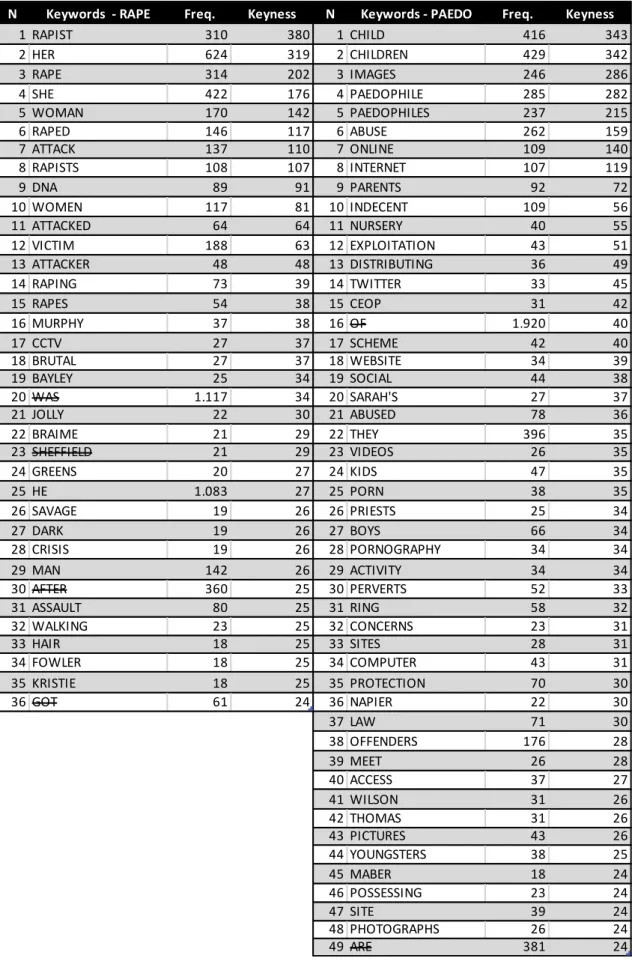

As can be seen in Table 2, RAPE had 36 positive keywords and PAEDO had 49 keywords in total. At first glance, the top keywords in both corpora refer to the perpetrator, the victim and the act. As expected, rapist/s, she, her and woman are key in RAPE whereas paedophile/s,

child and children are key in PAEDO. That rapist and rapists is key in RAPE and paedophile

and paedophiles is key in PAEDO was expected; however, an interesting thing to note is that

paedophiles in the plural is more than twice as frequent as rapists in the plural is in RAPE,

which suggest that paedophiles are represented collectively whereas rapists are more often individualised. Of the RAPE keywords, rape, raped and attack denotes an act whereas abuse is the only word denoting an act in PAEDO.

As the keywords were further examined in the concordance software, the same clear categorisation pattern started to form for both corpora. Apart from six words, the remaining keywords could all be grouped into the four following categories: perpetrator, act, societal perspective and victim. The six words, crossed over in Table 2, which were not included in any of the four categories, were mainly grammatical words, except for one place name. The remainder of this section will present and examine the four categories of

N Keywords - RAPE Freq. Keyness N Keywords - PAEDO Freq. Keyness

1 RAPIST 310 380 1 CHILD 416 343 2 HER 624 319 2 CHILDREN 429 342 3 RAPE 314 202 3 IMAGES 246 286 4 SHE 422 176 4 PAEDOPHILE 285 282 5 WOMAN 170 142 5 PAEDOPHILES 237 215 6 RAPED 146 117 6 ABUSE 262 159 7 ATTACK 137 110 7 ONLINE 109 140 8 RAPISTS 108 107 8 INTERNET 107 119 9 DNA 89 91 9 PARENTS 92 72 10 WOMEN 117 81 10 INDECENT 109 56 11 ATTACKED 64 64 11 NURSERY 40 55 12 VICTIM 188 63 12 EXPLOITATION 43 51 13 ATTACKER 48 48 13 DISTRIBUTING 36 49 14 RAPING 73 39 14 TWITTER 33 45 15 RAPES 54 38 15 CEOP 31 42 16 MURPHY 37 38 16 OF 1.920 40 17 CCTV 27 37 17 SCHEME 42 40 18 BRUTAL 27 37 18 WEBSITE 34 39 19 BAYLEY 25 34 19 SOCIAL 44 38 20 WAS 1.117 34 20 SARAH'S 27 37 21 JOLLY 22 30 21 ABUSED 78 36 22 BRAIME 21 29 22 THEY 396 35 23 SHEFFIELD 21 29 23 VIDEOS 26 35 24 GREENS 20 27 24 KIDS 47 35 25 HE 1.083 27 25 PORN 38 35 26 SAVAGE 19 26 26 PRIESTS 25 34 27 DARK 19 26 27 BOYS 66 34 28 CRISIS 19 26 28 PORNOGRAPHY 34 34 29 MAN 142 26 29 ACTIVITY 34 34 30 AFTER 360 25 30 PERVERTS 52 33 31 ASSAULT 80 25 31 RING 58 32 32 WALKING 23 25 32 CONCERNS 23 31 33 HAIR 18 25 33 SITES 28 31 34 FOWLER 18 25 34 COMPUTER 43 31 35 KRISTIE 18 25 35 PROTECTION 70 30 36 GOT 61 24 36 NAPIER 22 30 37 LAW 71 30 38 OFFENDERS 176 28 39 MEET 26 28 40 ACCESS 37 27 41 WILSON 31 26 42 THOMAS 31 26 43 PICTURES 43 26 44 YOUNGSTERS 38 25 45 MABER 18 24 46 POSSESSING 23 24 47 SITE 39 24 48 PHOTOGRAPHS 26 24 49 ARE 381 24

The perpetrator

The first category derived from the keywords was the perpetrator. As expected, the words

rapist* and paedophile* were among the top keywords in their respective corpora. However,

the remainder of the keywords show some interesting differences.

Firstly, the words that denote the perpetrator in RAPE (Table 3) are all singular, apart from the plural rapists, whereas the opposite is the case in PAEDO where all the words are in their plural form apart from paedophile. The frequencies shown in Table 2 of positive keywords, show that the plural paedophiles is more than twice as frequent as the plural rapists is. The pronoun they in PAEDO further supports the argument that paedophiles are collectivised more than rapists are. The word ring lends further evidence to this argument. It is used to describe a collective of paedophiles who collaborate and is most often used in the phrase

paedophile ring, as in example (1).

(1) Police have smashed a paedophile ring that repeatedly subjected two young girls to sickening sexual abuse [PAEDO]

The words attacker and perverts are also two interesting words to compare. As can be seen in example (2), the word attacker in RAPE is a nominalised verb (Baker, 2006), which refers to the perpetrator through the act committed, i.e. an attack. The word refers to the perpetrator by what he4 does as opposed to who he is and thus reduces the perpetrator to his act (Tabbert, 2012; Adampa, 1999). By using the word attacker, it refers both to the nature of the perpetrator’s act, as well as the perpetrator himself in one word. Furthermore, it could be

4 The controversial use of the masculine pronoun has been taken into consideration; however, seeing as a thorough examination of the corpora revealed almost no mentions of women as perpetrators, its use was deemed acceptable.

Table 3.Positive keywords in RAPE and PAEDO grouped into the category the perpetrator

PERPETRATOR - RAPE PERPETRATOR - PAEDO

rapist paedophile rapists paedophiles he they man offenders attacker perverts Jolly/Murphy/Savage/Bayley/Braime/Fowler/Greens priests dark/hair Maber/Napier/Wilson/Thomas ring

argued that there are some animalistic connotations to the word attack. Especially when used, as in example (2), in combination with a verb like hunting.

(2) Police are hunting a sex attacker who raped a teenage girl in Glasgow city centre [RAPE] Contrary to the word attacker, which implies a physical act in an almost animalistic-like manner, the word perverts in PAEDO refers to the state of mind of the perpetrator.

(3) Perverts downloading vile internet images of children being sexually abused face a new crackdown [PAEDO]

In example (3), the word functions both as a noun to refer to the perpetrator, while at the same time implying that the perpetrator’s state of mind is morally corrupt and deviant. Furthermore, the keyword priests refers to the perpetrator by reducing him to his occupation. This keyword has been grouped into this category, but it is also interesting from a societal perspective. The nominal priest* occurs 38 times in PAEDO, and it is by far the most frequent nominal used to refer to perpetrator through his occupation. This high frequency in PAEDO hardly suggests that a high proportion of paedophiles are priests, but is more likely a result of the heightened focus on child abuse within the Catholic Church over the past decade (Jean Hudson, personal communication). Both the RAPE and PAEDO keyword lists also contained several proper nouns that refer to a specific person.

(4) Evil Larry Murphy could be castrated if he commits further crimes while in Spain [RAPE] (5) He says Napier, then in his 20s, charmed the youngsters with his sports car, dashing good looks [PAEDO]

There were almost twice as many proper nouns in the RAPE keyword list than in the PAEDO keyword list. This, however, does not necessarily mean that more perpetrators overall are named in RAPE, and a further investigation into proper names (which will be presented in the next section of this paper) is needed in order to comment further on this. Finally, the words

dark and hair, like ring, both describe the rapist. As can be seen in example (6) and (7), the

words dark and hair are mostly used as descriptors to describe the perpetrator’s appearance either by the authorities or by the victim.

(6) He was wearing a dark, three-quarter length coat with white or cream buttons [RAPE] (7) He has dark brown, shaggy hair and was wearing a dark blue hoodie [RAPE]

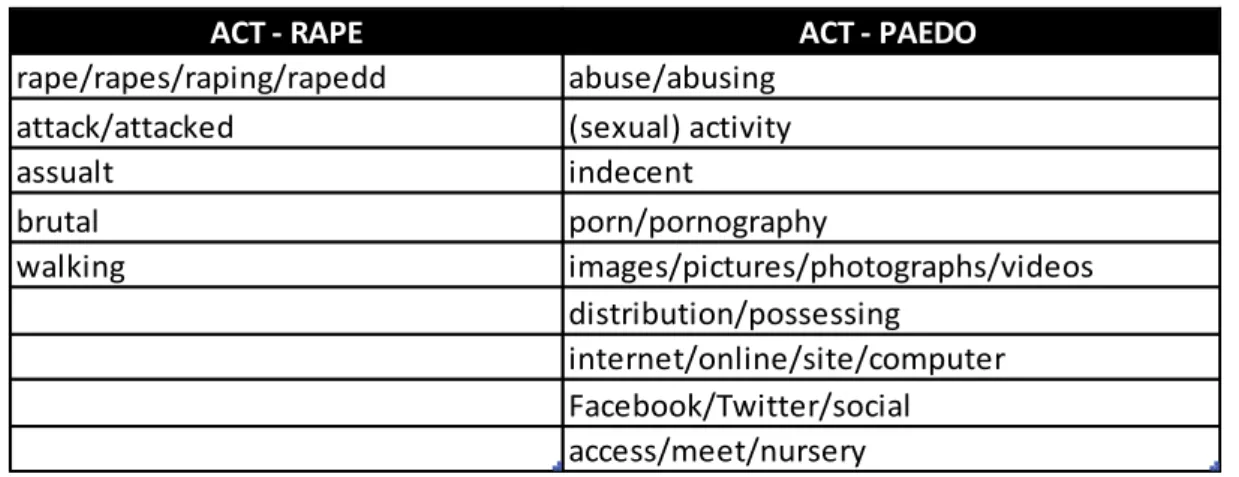

The act

The second category derived from the keywords is the act. As can be seen in Table 45, there are considerably more words from the PAEDO keyword list that fall under this category than from RAPE. The keywords from RAPE that denote the act itself are rape, rapes, raping,

raped, attack, attacked and assault. It was expected that rape and its three conjugated forms

would be key as it is implied by the added suffix –ist in rapist. What is common for all the words is that they imply some form of physical force and/or violence. The words attack/ed and assault are not necessarily acts of a sexual nature like rape; however, both words regularly collocate with the lemma sex* as example (8) and (9) show.

(8) He was in the process of carrying out a violent sexual attack on the victim when two passers-by came to her rescue [RAPE]

(9) The predator grabbed the woman and pushed her against a rock before subjecting her to a serious sexual assault [RAPE]

In the same manner, the keyword brutal, which is used as an adjective to describe the act (and in a few cases the perpetrator), is a very negatively loaded word that implies the physical force and violence as the words above.

The PAEDO keywords that denote an act are abuse/ing and activity. The word child often precedes abuse, and activity is often preceded by the word sexual as example (10) and (11) show.

(10) George was jailed for horrific historic charges of child abuse against two boys [PAEDO]

5 The words marked in parenthesis are words that often co-occur with the given keyword

ACT - RAPE ACT - PAEDO

rape/rapes/raping/rapedd abuse/abusing

attack/attacked (sexual) activity

assualt indecent brutal porn/pornography walking images/pictures/photographs/videos distribution/possessing internet/online/site/computer Facebook/Twitter/social access/meet/nursery

(11) Kieran Huelin, aged 28, denies engaging in sexual activity in the presence of a child [PAEDO]

It could be argued that child abuse and sexual activity are not as explicit and physical as the RAPE keywords are. Sexual activity, for example, is more vague and does not imply the same force and violence as sexual attack does. Furthermore, the words porn, pornography, images,

pictures, photographs and videos are all categorised as the act because perpetrators are distributing and possessing these kinds of material. The phrase indecent child abuse images

was one of the most frequent patterns in PAEDO. The words Internet, online, site, computer,

Facebook, Twitter, social (network) and nursery all denote the location of the act. Again,

there seems to be a lack of physicality in the PAEDO keywords: Apart from the specific location nursery, the act is represented as taking place in cyber space in the form of

possessing and distributing material. The keywords walking, access and meet further confirms

this physical/non-physical dichotomy. In RAPE, The victim and the perpetrator are walking the streets, whereas the perpetrator in PAEDO is often described as trying to access and meet potential victims online.

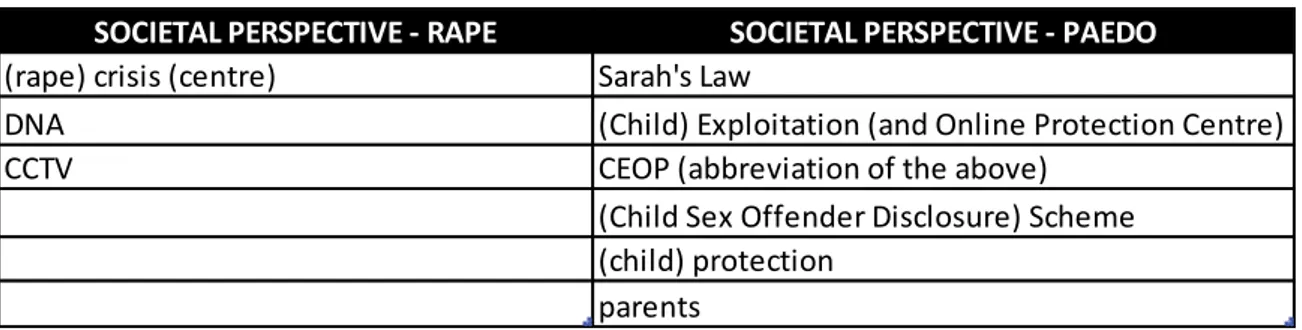

The societal perspective

The third category derived from the keywords is the societal perspective. What is meant by the societal perspective is how society, e.g. law enforcement, is represented as reacting to rapists and paedophiles in each corpus. In Table 6, the first four PAEDO keywords refer to different kinds of societal initiatives that handle with paedophiles or paedophilia. Sarah’s and

law, for example, most often co-occur as Sarah’s Law, which is the unofficial name of the

Child Sex Offender Disclosure Scheme. It was expected that exploitation would fall under the category the act, but after further investigation it was discovered that it was only used in the phrase Child Exploitation and Online Protection Centre (or CEOP). Similarly, protection is often preceded by the word child and refers to either a person or an organisation, e.g. child protection expert, child protection officer or child protection charity.

Of the RAPE keywords, the only word that referred to this kind societal implementation was

crisis, which co-occurred with the words rape, centre and network as in rape crisis centre and

rape crisis network. These keywords would suggest that the societal perspective is more prominent in the articles about paedophiles, especially the protection of the victim and the prevention of reoffending (i.e. the Child Sex Offender Disclosure Scheme). The keywords

DNA and CCTV in RAPE, as can be seen in example (12) and (13), refer to evidence used by

law enforcement to convict perpetrators and it further supports the physical/non-physical dichotomy between RAPE and PAEDO.

(12) Metin Sanci, 34, fled in agony with blood dripping from the deep wound which left behind crucial DNA on her face [RAPE]

(13) The jury was shown CCTV footage of the attack [RAPE]

The keyword parents was also grouped into this category because it is most often used in a sort of advisable role in which parents are advised by experts, law enforcement or society in general on how to protect their children from paedophiles. Apart from two or three examples in PAEDO, parents (the words parent, mother, father, mum and dad included) are never referred to as perpetrators.

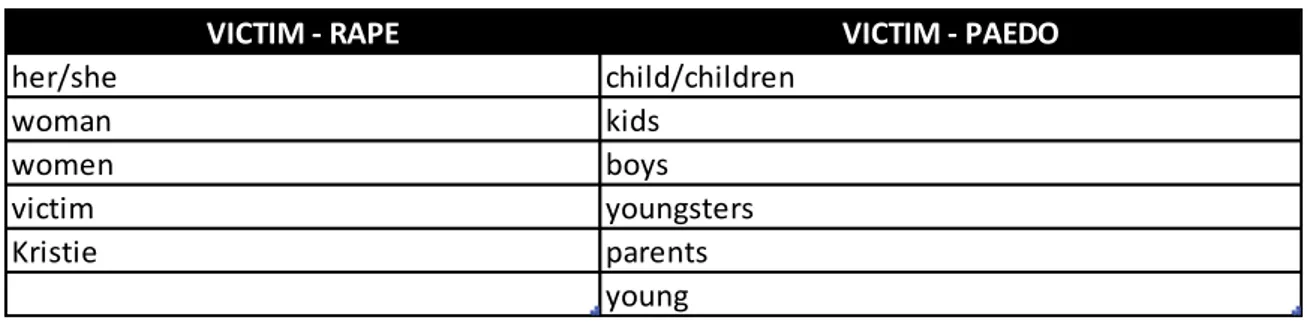

The victim

The fourth, and final, category derived from the keywords is the victim. It is not surprising that the keywords that denote the victim in RAPE are both female and adult, whereas the words in PAEDO denote the victim as what is considered underage.

SOCIETAL PERSPECTIVE - RAPE SOCIETAL PERSPECTIVE - PAEDO

(rape) crisis (centre) Sarah's Law

DNA (Child) Exploitation (and Online Protection Centre)

CCTV CEOP (abbreviation of the above)

(Child Sex Offender Disclosure) Scheme (child) protection

parents

It is interesting to note that, similar to the perpetrator category, the keywords in RAPE

generally refer to the victim in the singular, whereas the victim in PAEDO is referred to in the plural. The only descriptor is the word young in PAEDO, and it regularly co-occurs with

girl*, boy* and children, which, one could argue, is a double descriptor because it is already

implied in the words themselves. Lastly, the proper noun Kristie is the name of a victim in a particular case that has been highly prolific in the press. The absence of proper nouns referring to specific victims and the large amount referring to specific perpetrators in both RAPE and PAEDO are due to the Code of Practice that journalists are bound to follow. The Code of Practice enforced by the Press Complaints Commission (2012), explicitly states that ‘the press must not, even if legally free to do so, identify children under 16 who are victims or witnesses in cases involving sex offences’, whereas victims of sexual assault (i.e. victims over 16) can be named only if ‘there is adequate justification and they are legally free to do so’ (para. 7 & 11).

So far, the examination of the four categories of keywords suggests that there is a physical/non-physical as well as an individual/collective difference in the way rapists and paedophiles and their acts are represented. Paedophiles are represented as a mentally disturbed and morally corrupt collective whose acts are either referred to in slightly vague terms such as abuse and sexual activity or otherwise in the form of online activity, such as contacting victims or distributing and possessing child abuse material online. Rapists, on the other hand, are represented as violent individuals who carry out violent acts with words like

attacker, attack and brutal that carry slightly animalistic connotations to them. In terms of the

victim and the societal perspective, the actual victim seems more or less absent from the articles (apart from the words that are used to refer to them, i.e she, woman, victim, child,

kids, boys etc.). The societal angle in PAEDO seems to be on the protection of children in

VICTIM - RAPE VICTIM - PAEDO

her/she child/children woman kids women boys victim youngsters Kristie parents young

general, whereas in RAPE the focus is more on the perpetrator than the victim or a societal aspect.

5.2 Categories

In this section, the further investigation into the four categories is presented. Due to both page restraints and the interactive nature of the investigative process, it has not been possible to give a step-by-step presentation of the results. Instead, the findings are presented in tables in which the raw frequency of every term is included. In the comparison between frequencies from each corpus, it was decided that for there to be a significant difference between the frequencies, there had to be at least a difference of 100% between the two. In cases where there is a difference of 100% between the frequencies, the result will be marked in red to indicate RAPE or blue to indicate PAEDO.

5.2.1 The perpetrator

In the examination of the keyword categories, it was discovered that in both RAPE and PAEDO there were several words used to denote the perpetrator, as well as a few that described the perpetrator. It is interesting to investigate how the perpetrators are named and described because the terms carry ideologies, and, most often, the nouns refer to some kind of role or action which reduces the perpetrator to just that (Tabbert, 2012). Therefore, it was decided to further investigate terms that denote and describe the perpetrator. This was done by concordance and pattern searches as well as manually going through the wordlists. Table 7 shows the words found that denote a perpetrator as well as their frequency in each corpus6.

6 Pronouns such as he, him and the noun man have not been included as they are not interesting from a comparative perspective, unlike pronoun they, which has been included

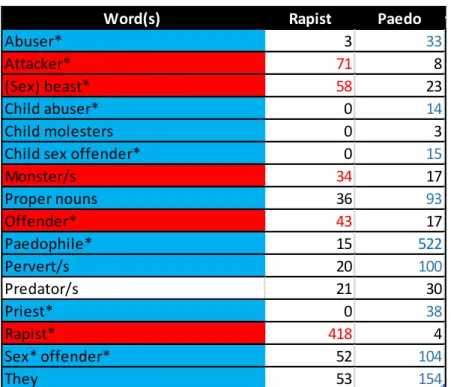

Firstly, it is interesting to note the variety of terms used to denote the perpetrator in both corpora. Apart from the expected rapist* and paedophile*, in both corpora there are 11 other nouns and noun phrases used to refer to the rapist and 15 to refer to the paedophile. In RAPE, the terms most often used to denote the perpetrator are attacker*, rapist*, beast, monster/s,

offender and sex offender. The two first terms are nominalised verbs (as was touched upon in

the keyness section) that defines the perpetrator through his act (i.e. to attack, to rape) and effectively reduces him to the act. In the keyness section, it was argued that the word attacker had violent and slightly animalistic connotations to it. These connotations are further

supported by the very negatively and emotionally loaded word beast, which quite literally refers to the perpetrator as an animal. As shown in example (14), the term often co-occurs with the premodifying noun sex. Also, the word monster is a very negatively and emotionally loaded wordwith similar animalistic or creaturely connotations as beast.

(14) The sex beast has been linked to six attacks in the popular resort of Magaluf [RAPE] (15) The vile sex monster boasted he "wasn't a convicted paedophile but a convicted rapist” [RAPE]

The terms offender and sex offender names the perpetrator by referring to his ‘role in the criminal proceedings’ (Tabbert, 2012, p. 134). Although it still reduces the perpetrator to this

Word(s) Rapist PaedoComments

Abuser* 3 33

Attacker* 71 8

(Sex) beast* 58 23

Child abuser* 0 14

Child molesters 0 3

Child sex offender* 0 15

Monster/s 34 17 Proper nouns 36 93 Offender* 43 17 Paedophile* 15 522 Pervert/s 20 100 Predator/s 21 30 Priest* 0 38 Rapist* 418 4 Sex* offender* 52 104 They 53 154

single role, it could be argued that it (without the premodifying noun sex) constitutes the most neutral term without any reference to the act, gender, social role etc. Both terms are used in RAPE and PAEDO, offender being most frequent in RAPE and sex offender in PAEDO. Sex

offender is the second most used noun (phrase) which denotes the perpetrator in PAEDO, and

it occurs twice as often as in RAPE, which would suggest that the phrase is more often associated with paedophiles than with rapists. The third most used noun in PAEDO is

pervert*, which confirms the initial indication that paedophiles and their sexuality are

represented as deviating from the norm. This is especially clear in example (16) and (17), where the descriptor sick represents their sexual preferences as pathological.

(16) Yet sick perverts are still on the loose in the UK [PAEDO]

(17) A sick pervert who dubbed himself "babylover" has been jailed for three years [PAEDO]

Less frequently used in PAEDO are the nominalised verbs abuser* and molester that, like

attacker* and rapist* in RAPE, refer to the perpetrator through his act. Unlike in RAPE

though, the premodifying noun child further specifies the act in child abuser* and child

molesters by referring to the victim of the act. Furthermore, the pronoun they, which is used

twice as often in PAEDO as in RAPE to denote the perpetrator, supports the initial keyness analysis that suggests that paedophiles are often represented as a collective. As shown in examples (18) to (21), the pronoun they is used in a generalising manner, representing all paedophiles as being the same.

(18) They will then trade images with other people with a sexual interest in children [PAEDO] (19) They persuade the child to send them images [PAEDO]

(21) Paedophiles can't ever be rehabilitated. They can only be controlled [PAEDO]

As well as being generalised, a large number of specific perpetrators are more frequently named in PAEDO than in RAPE, which some articles refer to as ‘naming and shaming’. The first 1200 words in each wordlists were gone through noting every name that could refer to a perpetrator, and these names were then manually checked in the concordance software to make sure they were referring to perpetrators. PAEDO had almost three times as many specific names as RAPE had. However, these numbers do not necessarily mean that more perpetrators overall are referred to by their name in PAEDO, but what they do show is

that a large number of perpetrators are mentioned by name very frequently as the 1200 first words in the wordlist are the most frequent words in each corpus. For the sake of good order, the 1200 last words in both wordlists were gone through as well, and there were between 30-40 perpetrators referred to by name in both corpora, which is not a clear enough indication that paedophiles are more often referred to by name than rapists. Finally, the term predator/s was used equally frequent in both corpora, and similarly to the term beast, represents the perpetrator as an animal preying on his victim.

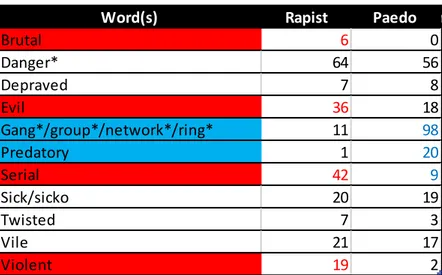

As mentioned earlier, it is also interesting to investigate which words are used to describe the perpetrators. One keyword described the perpetrator in RAPE (brutal) and one in PAEDO (ring). Table 8 shows the most interesting words found in the investigation of

descriptors. The words sick, twisted, depraved, vile and danger* (as in pose a danger or dangerous perpetrator) are used to the same extent in both corpora to describe the perpetrator. The words sick, twisted, depraved and vile are all highly emotionally loaded words that represent the perpetrator as mentally disturbed and deviating from the norms of society.

In RAPE, as example (22) and (23) show, the descriptors brutal and violent further support the indication that rapists, unlike paedophiles, are represented with terms that denote physicality and violence.

(22) Brutal city rapist Edward 'Eddie' Braime has been found following a nationwide manhunt [RAPE]

(23) Violent rapist locked up for brutal attack [RAPE]

Word(s) Rapist Paedo Comments

Brutal 6 0 Danger* 64 56 Depraved 7 8 Evil 36 18 Gang*/group*/network*/ring* 11 98 Predatory 1 20 Serial 42 9 Sick/sicko 20 19 Twisted 7 3 Vile 21 17 Violent 19 2

Furthermore, rapists are also described as evil and as reoffending perpetrators with the word

serial, which collocates with the word rapist as example (24), shows.

(24) POLICE are hunting a serial rapist targeting tourists on the holiday island of Majorca [RAPE]

In PAEDO, the keyword ring initially suggested that paedophiles were represented as large collaborative communities. As examples (25) to (27) show, the descriptors gang*, group* and

network* verify the initial indication that paedophiles are represented as ‘working together’ in

groups or in some cases, as example (27) shows, large organised networks.

(25) The paedophile gang was caught after officers from the Metropolitan Police paedophile unit launched Operation Rockferry [PAEDO]

(26) Police interviewed 139 girls aged as young as 11 who say they were abused by the group [PAEDO]

(27) Sussex men arrested as world's biggest paedophile network is smashed [PAEDO] These are all fairly neutral nouns denoting a group, and they do not describe the individual perpetrator, whereas in RAPE the words used to describe the perpetrator are all adjectives which describe features, so to speak, of the individual perpetrator.

In the investigation of the perpetrator, it has been established that there are many different, often negatively and emotionally loaded, words that both name and describe the perpetrator in each corpus. Although the same words are often present in both corpora, the difference in frequency confirms the initial physical vs. non-physical difference in RAPE. A body/mind distinction would perhaps be a more suitable term to use about the difference in representation of the perpetrator in RAPE and PAEDO. Rapists are most often reduced to their physical and violent acts through the nominalised verbs rapist and attacker and

animalistic terms such as beast and monster, and described as evil, brutal and violent. On the other hand, paedophiles are named by words, such as paedophile and pervert, which refers to them as being mentally disturbed and as deviating from the norms of society with regard to their sexuality. Furthermore, paedophiles are described as twisted, vile, depraved and sick, although these terms are used as frequently to describe rapists. Finally, the pronoun they and the descriptors gang, ring, group and network both generalise and collectivise paedophiles.

5.2.2 The act

In the keyness examination of the category the act, there were indications of the body vs. mind distinction as with the examination of the perpetrator. The rapist’s act was physical and violent, whereas the paedophile’s act was either slightly vaguely referred to or occurring online in the form of possessing and distributing material. The further investigation into the act was carried out in the same manner as the previous category. It was decided to investigate the terms denoting and describing the act; however, this category will furthermore include an examination of the location of the act. In Table 9 the terms that denote an act are listed.

As the keywords indicated, the most frequently used words to denote the rapist’s act are the words rape, rapes, raping and raped; attack, attacks, attacking and attacked; assault, assaults and assaulted. The words attack and assault denote a form of physical violent force, but are slightly vaguer than the word rape, as they are not necessarily of a sexual nature. In many cases though, both words are preceded by a form of the lemma sex* as example (28) and (29) show.

(28) He was in the process of carrying out a violent sexual attack on the victim when two passers-by came to her rescue [RAPE]

(29) The predator grabbed the woman and pushed her against a rock before subjecting her to a serious sexual assault [RAPE]

In the further investigation into the representation of the act, at least five other terms were found which establishes the representation of rapists’ acts as being of both a

Word(s) Rapist Paedo

Abuse/s/ing/d 72 226

Attack/s/ing/ed 270 48

Assualt* 51 38

Beat* 15 6

Bodily harm 10 0

Child (sex) abuse 0 72

Distribut*/exchang*/shar*/swap*/trad* 0 107 Drag* 20 1 Force* 21 4 Grab* 17 0 Groom* 9 68 Image*/photograph*/porn*/video* 1 424 Indecent assault* 19 8 Molest* 1 10 Possessing 0 23 Paedophilia 0 15 Prey* 14 21 Prowl*/trawl* 11 8 Rape/es/ed/ing 368 96 Sex* abuse/s/ing/d 16 81 Sexual activity 2 26 Sex* assault* 61 34 Strik*/struck 18 2 Target* 25 35

physical and violent nature. Examples (30) to (35) show the use of the terms beat, drag, grab,

force and bodily harm.

(30) Robert Carpenter raped a 37-year-old woman on a footpath and beat her with such force he knocked her dentures out and broke her jaw [RAPE]

(31) He grabbed the girl, dragging her into a corner of the lane, where he raped her [RAPE] (32) He carried out the brutal rape at his home after grabbing her hands and dragging her to his bedroom [RAPE]

(33) He held her down and raped the "hysterical" woman, before beating her up [RAPE] (35) A jury convicted him of raping the woman and inflicting grievous bodily harm on her with intent [RAPE]

As the examples show, these accounts of the perpetrators’ interaction with the victims are extremely physical, describing in detail the perpetrators’ actions. Furthermore, the words

prey, target, strike, struck, prowl and trawl carry very animalistic connotations, and, as

examples (36) to (39) show, they describe the perpetrator as an animal on the loose roaming the streets in the search for its next prey.

(36) No one can read this horrific account of a teenager preyed on by sexual predators without feeling repulsion [RAPE]

(36) Married deviant trawled the streets for targets [RAPE]

(37) The local authority refused to listen to their fears that this monster would strike again [RAPE]

(38) Cold case justice has trapped a dangerous rapist nearly 30 years after he struck [RAPE] (39) He will be free to prowl the streets after serving just 10 years for repeatedly raping a young woman [RAPE]

In PAEDO, the words abuse, abuses, abusing and abused are frequently used to denote the perpetrator’s act. The words regularly refer to the act as a general phenomenon as example (40) shows, but they also refer to specific cases as in example (41). Both uses of these words are, however, equally vague. What the term abuse entails is less explicit than the terms rape and attack are in RAPE. Sometimes, the conjugated forms of abuse occur with the

premodifying nouns sex* (example (42)) or the premodifying noun phrase child sex. Common for all three uses though, is that they do not clearly show what actually happens to the victim. (40) Unless we address the seriousness of abuse in this country, thousands of lives will continue to result in misery [PAEDO]

(41) After his arrest revealed another attempt to meet a child for abuse [PAEDO]

(42) It was then that he began sexually abusing the boy, often taking him to a disused airfield to "let him practise trying to drive" - before abusing him [PAEDO]

The most frequent way the act is represented in PAEDO though, is not in actual interaction with the victim, but in the form of possessing, distributing, exchanging, sharing, swapping and trading material such as images, photographs, porn and videos of victims, and often online. As example (43) to (47) show, any physical interaction with the victim is absent and there is no mention of perpetrators actually creating the material.

(43) He was jailed for possessing and distributing indecent images [PAEDO]

(44) Baxter, 23, of Redland, Bristol, bragged to fellow paedophiles in online chatrooms in

exchange for more child pornography [PAEDO]

(45) He shared 110 images and had more than 100 others on his computer [PAEDO] (46) A policeman was jailed for a year yesterday for being part of a nationwide paedophile ring which swapped child porn online [PAEDO]

(47) They will then trade images with other people with a sexual interest in children to gain 'credit' within online paedophile communities [PAEDO]

Furthermore, paedophiles are represented as preying, trawling, prowling, targeting their victims, again mostly online. Although these words have animalistic connotations, the words are used in a context that represents the perpetrator’s acts as online and well planned (example (48) to (50)) which is in direct contrast to the animalistic.

(48) The recent case of pervert Barry McCluskey, 39, who posed as a schoolgirl to prey on kids online [PAEDO]

(49) The Sunday Mirror launches a campaign to force Twitter to get rid of the paedophiles who prowl it in search of young victims [PAEDO]

(50) The unit is dedicated to catching paedophiles who trawl the web to groom and abuse children. [PAEDO]

(51) Judge Philip Wassall told Wilkinson that he had been grooming 'Amy' over a long period of time [PAEDO]

Additionally, the term grooming is used to describe the process by which the perpetrator gains a victim’s or a victim’s parent’s trust with the intention of eventually taking advantage of this trust. The term, as shown in examples (50) and (51), is further evidence of this representation of the perpetrator’s act as being meticulously planned and far from impulsive.

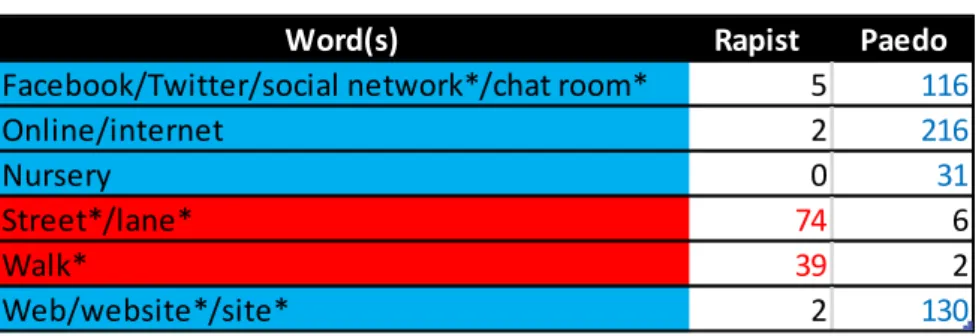

There are clear indications that rapists’ acts are represented as being on the streets in physical interaction with the victim, whereas paedophiles’ acts are mostly

represented as happening online and not in physical interaction with the victim. This is further supported by the words in Table 10, which denote the locations where the acts take place. As the keywords analysis suggested, apart from nursery, specific locations are rarely referred to in PAEDO.

On the other hand, words such as online, internet, Facebook, Twitter and website are

extremely frequent and clearly supports the argument that the physical interaction between the perpetrator and victim is absent in PAEDO (examples (52) to (54)).

(52) Thousands of conversations are logged in a bid to catch paedophiles who stalk online chatrooms [PAEDO]

(53) And they groomed her by befriending her on Facebook [PAEDO]

(54) Dale admitted to distributing the images to fellow paedophiles on the internet through a

website [PAEDO]

Word(s) Rapist Paedo

Facebook/Twitter/social network*/chat room* 5 116

Online/internet 2 216

Nursery 0 31

Street*/lane* 74 6

Walk* 39 2

Web/website*/site* 2 130

Contrary, in RAPE words such as street*, lane* and walk* all confirm the argument that the interaction between the perpetrator and the victim is represented as being physical in specific locations as shown in examples (55) to (57).

(55) Afterwards she was unceremoniously dumped in the street in an appalling state [RAPE] (56) He pulled her into the lane, where he threatened to kill her, then raped her [RAPE] (57) The man attacked the girl as she walked home after having visited a friend's house [RAPE]

Lastly, the words used to describe the act in both RAPE and PAEDO were investigated. The words, listed in Table 11, further confirm the body vs. mind distinction between RAPE and PAEDO. Examples (58) to (60) show that the rapists’ acts are described as brutal, vicious and

violent.

(58) Daly pounced on her and subjected her to the brutal sex attack [RAPE] (59) Tyson viciously raped an 18-year-old woman in 1992 [RAPE]

(60) He carried out rape and a string of violent sex attacks [RAPE]

PAEDO, on the other hand, is more or less devoid of any physical descriptors of the act. Instead, the words refer to the act as deviant and disturbing as example (61) to (66) show. (61) A third man urged her to commit a series of depraved acts [PAEDO]

(62) The bus driver found a series of sick images saved on its memory and immediately handed it to police [PAEDO]

Word(s) Rapist Paedo

Brutal* 29 0 Depraved/depravity 0 27 Horrific/ing/ed/ly 39 25 Shock* 4 28 Sick* 16 40 Vicious* 8 0 Vile 8 23 Violent* 65 12

(63) A collection of vile child abuse images and videos were also found [PAEDO] (64) Pervert downloaded 70,000 sickening child porn images [PAEDO]

(65) Some of Greene's crimes were so sick they made him vomit [PAEDO] (66) She was so shocked by what she saw that she was physically sick [PAEDO]

The words are very negative and emotionally loaded and indirectly say something about the mental state of the perpetrator – the perpetrator must be mentally disturbed to carry out these acts – and it also speaks of the way society views the perpetrator’s sexual preference. In examples (59) and (60), the acts are described as so sickening and shocking that they made people physically sick. These two examples could explain why the acts in PAEDO are quite vaguely represented: The actual crime is too shocking, too vile, too sick to be described.

In the investigation of the act, the body/mind distinction between RAPE and PAEDO was found to be even more evident than in the investigation of the perpetrator. The rapist’s act was represented as being physical and violent with words such as rape, attack,

beat, grab and drag denoting the act and words such as brutal and violent describing it.

Furthermore, words such as prey, strike, struck, prowl and trawl viewed in context

represented the rapist as a wild and impulsive animal loose on the streets. On the contrary, the paedophile’s act was represented vaguer as abuse or sexually abusing, but most often the act represented the paedophile as a meticulous predator grooming his victims or possessing and

distributing material of victims online. Lastly, the words describing the perpetrator’s act were

descriptive of the disgust of the perpetrator’s sexual preference and not the absent physical act.

5.2.3 The societal perspective

In the investigation of the keywords,several words fitted into the societal category, but it was less obvious where to begin the further investigation than with the three other categories under examination. Therefore, during the investigation of the results, words and phrases that were deemed of a societal nature were noted down and put into this category for further investigation. The words were investigated in the same manner as the two previous

society in general. The law enforcement angle (Table 12) show that a lot of the terms used about the police’s handling of the perpetrator have animalistic connotations.

In RAPE, words such as hunt, trap, catch, caught and cage describe the process of finding and arresting the perpetrator with words usually associated with the treatment of an animal. Examples (67) to (71) show this clearly.

(67) Leading the hunt for the rapist is Senior Investigating Officer, DCI Simon Werrett [RAPE]

(68) Police revealed how they trapped him [RAPE]

(69) COPS are appealing for the public's help to catch on-the-run teenage rapist [RAPE] (70) Keith Davison was caught after police found DNA [RAPE]

(71) The sex beast was caged for two years in 2010 for assaulting three young girls [RAPE] Viewed in context with the other animalistic words found in the two previous categories such as beast, monster, brutal, prey, attack, strike, struck, drag and prowl, there is clearly an animalistic discourse present in RAPE. A discourse of the hunter (police) and the hunted (the perpetrator). Apart from catch, caught, prey and predatory these animalistic terms are very infrequent in PAEDO.

Furthermore, the words CCTV and DNA in RAPE are means of which the police build a case against the perpetrator (examples (72) and (73)).

Words(s) Rape Paedo

Cage* 16 5

Catch*/caught 41 48

CCTV 27 0

Child Exploitation and Online Protection Centre/CEOP 3 45

The Child Sex Offender Disclosure Scheme/Sarah's Law/Megan's Law 0 45

DNA 89 5

Hunt* 37 6

Sex Offenders' Register 26 14

Track* 16 25

Trap* 14 8