http://www.diva-portal.org

Preprint

This is the submitted version of a paper presented at 10th International Conference on the

Internet of Things (IoT 2020).

Citation for the original published paper:

Maus, B., Salvi, D., Olsson, C M. (2020)

Enhancing citizens trust in technologies for data donation in clinical research:

validation of a design prototype

In: Companion Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on the Internet of

Things (IoT 2020) New York 10121-0701

N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper.

Permanent link to this version:

clinical research: validation of a design prototype

BENJAMIN MAUS

∗, DARIO SALVI, and CARL MAGNUS OLSSON,

Malmö UniversityMobile phones, wearable trackers and Internet of Things devices continuously produce data about our health and lifestyle that can be used for medical research. However, how data is accessed, by whom and for what purpose is not always understood. This lack of transparency undermines citizens trust in the use of such technologies for research purposes. This paper proposes a set of 6 use cases and related mock-up interfaces for citizen science, mobile-based health research: “Curated information about the institution”, “Sequential consent of shared data”, “Updates from the institution”, “Privacy notifications”, “Overview of donated data” and “Personal impact in medical research”. Interviews and Kano analysis of the interfaces with 6 prospective users show that all except “Privacy notifications” are perceived as important and beneficial for increasing users’ trust. The defined use cases can guide the development of future data collection platforms.

CCS Concepts: • Security and privacy → Human and societal aspects of security and privacy; • Human-centered computing → Interaction design; • Information systems → Information systems applications; • Applied computing → Consumer health.

Additional Key Words and Phrases: mobile-health, citizen science,transparency, trust, privacy ACM Reference Format:

Benjamin Maus, Dario Salvi, and Carl Magnus Olsson. 2020. Enhancing citizens trust in technologies for data donation in clinical research: validation of a design prototype. In IOT-HSA-2020: Workshop on Internet of Things based Health Services and Applications, October 6, 2020, Malmö, Sweden.ACM, New York, NY, USA, 8 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/1122445.1122456

1 INTRODUCTION

Internet of Things (IoT) devices like fitness trackers, mobile phones, and smart home appliances can continuously retrieve information about our bodies and lives including physical activity, cardio-vascular health, sleep quality, nutrition etc. [1]. This wealth of information can be used for medical research to improve patients’ well-being and find new, cost-effective ways to provide healthcare [11]. This is particularly compelling in the event of pandemics like the one experienced in 2020, as IoT can allow participants enrolled in clinical studies to be followed-up remotely, thus avoiding the risk of being infected in clinics.

When installing these technologies, users are typically prompted to accept terms of use and privacy policies as well as to give access to hardware and software resources to the application, for example, on their mobile phones. These prompts are poorly understood by many users [19] and their lack of clarity can undermine their trust in the technology [10]. Trust is fundamental especially when sensitive data is shared, like in clinical research, as lack of trust has proved to be detrimental for some research initiatives [22]. Addressing this challenge, we present the results

∗Primary author.

Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. Copyrights for components of this work owned by others than ACM must be honored. Abstracting with credit is permitted. To copy otherwise, or republish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific permission and/or a fee. Request permissions from permissions@acm.org.

IOT-HSA-2020, October 7–9, 2020, Malmö, Sweden © 2020 Association for Computing Machinery. ACM ISBN 978-1-4503-XXXX-X/18/06...$15.00 https://doi.org/10.1145/1122445.1122456

IOT-HSA-2020, October 7–9, 2020, Malmö, Sweden Maus, Salvi and Olsson

from a study about the impact that “transparency enhancing tools” (TETs) [9] may have on users’ trust in IoT-based clinical research.

The goal of TETs is to make the underlying data access, sharing and use more transparent and to enable participants to better understand the implications of disclosing their data [17]. In other words, TETs provide users with information regarding how their personal data are being used, who has accessed them, for what purpose, when and where data are stored [8]. TETs can be subdivided into “ex-ante”, which guide users before they make choices about exposing their data and “ex-post”, which inform users about what data was disclosed and to whom [17]. Most of existing research on TETs focus on mobile phones and social networks [16, 17] and scant research exists in adopting TETs in medical research [7]. Examples in the healthcare sector include tools to visualise what parts of an electronic health record are accessed, by whom and for what purposes [8] and privacy notifications, i.e. short messages that notify users of data breaches, consequences of their data sharing and general recommendations [14].

Our research takes the perspective of citizen science, which has experienced a sustained growth since the advent of the Internet and mobile phones [2]. Thanks to platforms like Mobistudy [21], citizens can participate in clinical research they wish to support by donating their data and performing measurements using their phones and connected devices. In this context, providing mechanisms that increase transparency and trust is of relevance to promote participation over time. The main contribution of this paper is the definition and validation of a set of ex-ante and ex-post TET use cases to be included in platforms for mobile and IoT-based clinical research.

2 METHODS

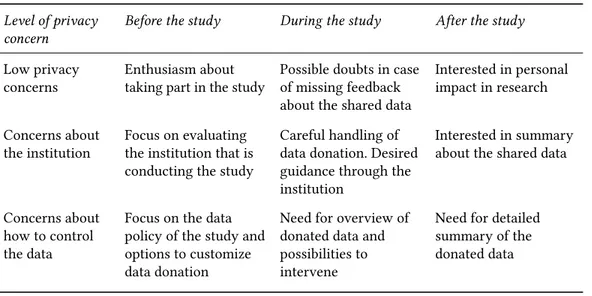

This research has been developed in four main steps, following common practices in user-centered design [18] and research through design [24]. First, typical information-seeking behaviours were defined based on existing research. Second, use cases for TETs were derived to address these behaviours. Third, mock-up interfaces corresponding to each use case were developed, and finally, semi-structured interviews with prospective users were conducted based on the mock-up interfaces. We segmented users based on their information-seeking behaviour with respect to their level of privacy concerns: low privacy concerns, concerns about the institution making use of the data, and concerns about how to control the data (Table 1). This segmentation is based on viewpoints of the groups that Morton and Sasse identified as 1) Benefit Seekers, 2) Organizational Assurance Seekers, and 3) Information Controllers [13] which we adapted to the context of citizen science data donation. To this, we tied hypothesised behaviours of each level of privacy concern before, during and after having participated in a research study.

Based on the expected information-seeking behaviours, six use cases for ex-ante and ex-post TETs were created, to address the main identified needs and concerns. These, in turn, allowed the development of mock-up interfaces using an existing user-interface kit of Google’s Material Design for the digital prototyping tool Figma1. The interfaces were based on a mobile phone interaction,

but analogous interfaces can be developed for other media using the same prototyping tool. We then tested the mock-ups with volunteers. The aim of the test was (1) to identify possible major usability problems, (2) to evaluate the relevance of the proposed features, and (3) to learn if they affected the perceived trust of the users in the app. Applying moderated tests [5], users explored and interacted with each interface and were then interviewed. Interviews included open-ended questions about how they understood each feature, what they liked and disliked about it, and if there were any major usability issues.

Table 1. Expected information-seeking behaviours

Level of privacy concern

Before the study During the study After the study

Low privacy

concerns Enthusiasm abouttaking part in the study Possible doubts in caseof missing feedback about the shared data

Interested in personal impact in research Concerns about

the institution Focus on evaluatingthe institution that is conducting the study

Careful handling of data donation. Desired guidance through the institution

Interested in summary about the shared data

Concerns about how to control the data

Focus on the data policy of the study and options to customize data donation

Need for overview of donated data and possibilities to intervene

Need for detailed summary of the donated data

Collected data was analysed with affinity diagrams [12]. To evaluate relevance, the two questions posed in a Kano analysis [3] were included as part of the interview. For every use case, users rated how they would feel if the feature were present and how they would feel if the feature were absent in an citizen science app. Users were asked to select one of the following five responses: “Like”, “Must-be”, “Neutral”, “Live-with” and “Dislike”. We then combined the Kano-analysis with a question about the perceived importance, where users were asked to rate the importance of each proposal on a scale from 1 to 9 [20]. Finally, users rated on a scale from 1 to 5 if the use case would decrease, not affect at all, or increase their trust in the app or the simulated study.

3 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

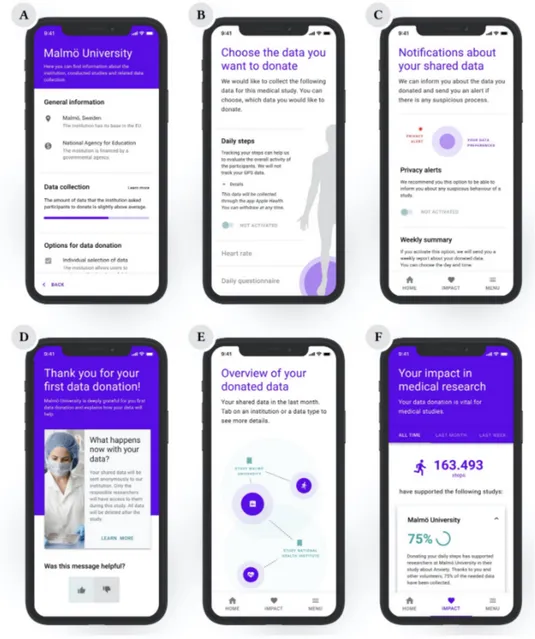

We defined the following 6 use cases and developed mock-up interfaces for each one of them (figure 1).

(A) Curated information about the institution: An ex-ante TET that provides e.g. the location and funding of the institution as well as an overview of their studies and data policies. (B) Sequential consent of shared data: Multi-layer information of the collected data in the

form of an ex-ante TET with the possibility of accepting different data sharing options. (C) Updates from the institution: Templates for messages from the institution as an ex-post

TET such as updates about the study as well as data processing and “thank you” messages. (D) Privacy notifications: An ex-post TET that provides notifications about privacy alerts and

collected data in the form of push notifications

(E) Overview of donated data: Illustrating connections between institutions and collected data in the form of an ex-post TET.

(F) Personal impact in medical research: A feature that indicates the impact of the user’s data for research as an ex-post TET.

We tested the mock-ups with six volunteers whose age ranged from 21 to 27 years. All participants appreciated the general presentation of the app design, which was expressed by terms such as ’contemporary’ and ’clearly laid out’. Users valued interfaces with few elements positively but were willing to go into details whenever a text or description attracted their attention. For example,

IOT-HSA-2020, October 7–9, 2020, Malmö, Sweden Maus, Salvi and Olsson

Fig. 1. Mock-ups of the design proposals (A: Information about the institution, B: Selection of shared data, C: Guidance through the institution, D: Data/privacy notifications, E: Overview of donated data, F: Impact in medical research)

participants appreciated mocked details about how their data was processed, such as through which app or during which period. We could also confirm existing recommendations [15] in regards to providing precise additional information as a risk for frustration Thus, providing multiple layers of information and details is one of the fundamental guidelines for TETs in mobile health contexts.

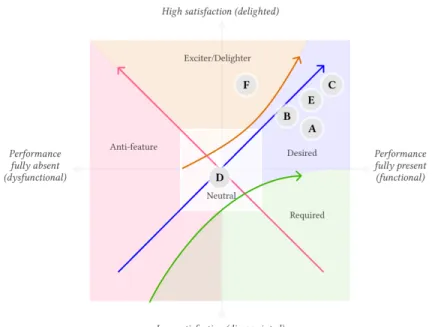

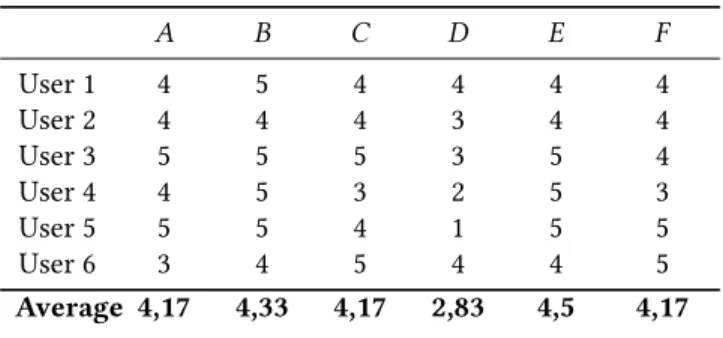

Tables 2 and 3 show how users rated the perceived importance of the six use cases, and how these would impact their trust towards the app/study. Users perceived ex-ante TETs, in this case, the curated information about the institutionand the sequential selection of shared data as slightly

Fig. 2. Results of Kano analysis (A: Information about the institution, B: Selection of shared data, C: Guidance through the institution, D: Data/privacy notifications, E: Overview of donated data, F: Impact in medical research)

more important than ex-post TETs (see Table 3). Nonetheless, the impact of ex-post TETs on trust seems similar to ex-ante TETs and is valued positively by the users. TETs with low complexity, such as the guidance through the institution use case can have a high impact on the users’ trust if the form of communication is designed carefully. High complexity TETs like the overview of donated datacan also increase users’ trust, although, in our mock-ups, the visual connection between the institutions and the collected data were not always unambiguous.

Sequential consent of shared datawas highly valued especially in terms of perceived impact on trust, which indicates that providing per-task/item consent, instead of standard, single text privacy policies, is essential for ex-ante TETs. Designers should consider this recommendation for related apps and electronic consent in general. This features should further include the possibility to remove consent of any item at any moment as also suggested by [23], which is further supported by some of our users expressing willingness to agree to only a subset of data types to be collected. Figure 2 shows the results of the Kano analysis. The four features related either directly to the institution (A, C) or the data collection (B, E) were perceived as Desired attributes, the impact in medical research feature (F) was seen as an Exciter attribute which was not expected from most of the participants and though appreciated. Privacy/data notifications (D) was instead seen as a Neutralor almost an Anti-feature product attribute.

As shown by both the Kano analysis and the ratings, users considered the importance of the data/privacy notificationsuse case as low. In terms of perceived trust, some users indicated that this use case could even decrease their trust in the app or study, which suggests that data donation platforms have to be very careful when implementing new forms of TETs. Users appreciated transparency in these platforms but involving them into any kind of suspicious privacy processes can cause an adverse effect.

IOT-HSA-2020, October 7–9, 2020, Malmö, Sweden Maus, Salvi and Olsson

Table 2. Perceived impact on trust towards the app/study that the use cases generate (1= The use case would decrease my trust very much, 5= The use case would increase my trust very much.)

A B C D E F User 1 4 5 4 4 4 4 User 2 4 4 4 3 4 4 User 3 5 5 5 3 5 4 User 4 4 5 3 2 5 3 User 5 5 5 4 1 5 5 User 6 3 4 5 4 4 5 Average 4,17 4,33 4,17 2,83 4,5 4,17

Table 3. Perceived importance of the six use cases (1=not important at all, 9=very important)

A B C D E F User 1 6 6 6 5 4 8 User 2 7 7 8 3 6 6 User 3 8 9 8 5 7 4 User 4 8 8 6 4 8 7 User 5 8 8 6 3 9 7 User 6 7 8 9 8 8 8 Average 7,33 7,67 7,17 4,67 7 6,67

From comments and observations recorded during the test, “pull” ex-post TET concepts such as visualisations about the collected data and the impact in medical research were valued highly positively by the users. Instead, “push” types of interaction like notifications should be deactivated by default unless they are reminders for study-related activities, and only send out in low frequencies, e.g. on a weekly base.

4 CONCLUSIONS, LIMITATIONS AND FUTURE WORK

In this study, we designed six transparency-enhancing use cases and related example interfaces for data donation in health-related research. The results of the user tests indicate that all use cases are perceived important and five of the six ideas may produce an impact on users’ trust.

While our tests are useful to identify usability problems within the prototype, they can only indicate perceptions about TETs and are hardly generalizable at this point [6]. With the aim of the test being to assess the use cases in a generic and abstract way, it has to be noted that in practice the mock ups had to refer to show content and details related to a concrete simulated study to be understandable. The presence of details, like the choice of a particularly trustful institution, or the lack of them, such as the aim and the context of the clinical study or its data processing policies, may have had an effect on the results. Therefore, different simulated scenarios should be tested in the future to further validate these ideas.

The characteristics of the users can be seen as another limitation of this research since all participants were from a young age group. An additional threat to validity is the fact that the expressed attitude of participants might differ from their real behaviour [4]. For all these reasons, larger and more varied cohorts would be necessary to confirm the results.

In future work, more iterations would be needed to further improve and test the prototype, e.g. with a higher level of details and by comparing different types of data visualisation. An entire study-enrollment process with more elaborated content should be tested and possibly also implemented into an existing research platform like Mobistudy. Future research should also match the design proposals against relevant regulatory frameworks in terms of data protection and ethical guidelines. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is partially funded by the Knowledge Foundation through the Internet of Things and People research profile.

REFERENCES

[1] Stephanie B Baker, Wei Xiang, and Ian Atkinson. 2017. Internet of things for smart healthcare: Technologies, challenges, and opportunities. IEEE Access 5 (2017), 26521–26544.

[2] Rick Bonney, Jennifer L Shirk, Tina B Phillips, Andrea Wiggins, Heidi L Ballard, Abraham J Miller-Rushing, and Julia K Parrish. 2014. Next steps for citizen science. Science 343, 6178 (2014), 1436–1437.

[3] Konstantinos Christoglou, Chris Vassiliadis, and Ioakim Sigalas. 2006. Using SERVQUAL and Kano research techniques in a patient service quality survey. World hospitals and health services: the official journal of the International Hospital Federation42, 2 (2006), 21–26.

[4] Kay Connelly, Ashraf Khalil, and Yong Liu. 2007. Do I do what I say?: Observed versus stated privacy preferences. In IFIP Conference on Human-Computer Interaction. Springer, 620–623.

[5] Joseph S Dumas and Beth A Loring. 2008. Moderating usability tests: Principles and practices for interacting. Elsevier. [6] Laura Faulkner. 2003. Beyond the five-user assumption: Benefits of increased sample sizes in usability testing. Behavior

Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers35, 3 (2003), 379–383.

[7] Ana Ferreira and Gabriele Lenzini. 2015. Can Transparency Enhancing Tools Support Patient’s Accessing Electronic Health Records? In New Contributions in Information Systems and Technologies. Springer, 1121–1132.

[8] Ana Ferreira, Gabriele Lenzini, Cátia Santos-Pereira, Alexandre B Augusto, and Manuel E Correia. 2014. Envisioning secure and usable access control for patients. In 2014 IEEE 3nd International Conference on Serious Games and Applications for Health (SeGAH). IEEE, 1–8.

[9] Milena Janic, Jan Pieter Wijbenga, and Thijs Veugen. 2013. Transparency enhancing tools (TETs): an overview. In 2013 Third Workshop on Socio-Technical Aspects in Security and Trust. IEEE, 18–25.

[10] Suwon Kim and Seongcheol Kim. 2018. User preference for an IoT healthcare application for lifestyle disease management. Telecommunications Policy 42, 4 (2018), 304–314.

[11] Phillip A Laplante and Nancy Laplante. 2016. The internet of things in healthcare: Potential applications and challenges. It Professional18, 3 (2016), 2–4.

[12] Andrés Lucero. 2015. Using affinity diagrams to evaluate interactive prototypes. In IFIP Conference on Human-Computer Interaction. Springer, 231–248.

[13] Anthony Morton and M Angela Sasse. 2014. Desperately seeking assurances: Segmenting users by their information-seeking preferences. In 2014 Twelfth Annual International Conference on Privacy, Security and Trust. IEEE, 102–111. [14] Patrick Murmann. 2018. Usable transparency for enhancing privacy in mobile health apps. In Proceedings of the 20th

International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction with Mobile Devices and Services Adjunct. 440–442. [15] Patrick Murmann. 2019. Eliciting Design Guidelines for Privacy Notifications in mHealth Environments. International

Journal of Mobile Human Computer Interaction (IJMHCI)11, 4 (2019), 66–83.

[16] Patrick Murmann and Simone Fischer-Hübner. 2017. Tools for achieving usable ex post transparency: a survey. IEEE Access5 (2017), 22965–22991.

[17] Patrick Murmann and Simone Fischer-Hübner. 2017. Usable transparency enhancing tools: A literature review. [18] Donald A Norman and Stephen W Draper. 1986. User centered system design: New perspectives on human-computer

interaction. CRC Press.

[19] Jana M Pownell, Leslie Larson, Darcy H Neago, Mary S Pesch, Sara J Ayres, and Robin R Austin. 2020. Using Readability to Explore Data Privacy Statements Within Mobile Health Applications. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing 38, 5 (2020), 217–223.

[20] Md Mamunur Rashid. 2010. A review of state-of-art on Kano model for research direction. International Journal of Engineering Science and Technology2, 12 (2010), 7481–7490.

[21] Dario Salvi, Jameson Lee, Carmelo Velardo, Rishi Arvin Goburdhun, and Lionel Tarassenko. 2019. Mobistudy: an open mobile-health platform for clinical research. In 2019 IEEE 19th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Bioengineering (BIBE). IEEE, 918–921.

IOT-HSA-2020, October 7–9, 2020, Malmö, Sweden Maus, Salvi and Olsson [22] Tjeerd-Pieter Van Staa, Ben Goldacre, Iain Buchan, and Liam Smeeth. 2016. Big health data: the need to earn public

trust. Bmj 354 (2016), i3636.

[23] Hawys Williams, Karen Spencer, Caroline Sanders, David Lund, Edgar A Whitley, Jane Kaye, and William G Dixon. 2015. Dynamic consent: a possible solution to improve patient confidence and trust in how electronic patient records are used in medical research. JMIR medical informatics 3, 1 (2015), e3.

[24] John Zimmerman, Jodi Forlizzi, and Shelley Evenson. 2007. Research through design as a method for interaction design research in HCI. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems. 493–502.