Involuntary Immobility

and

American Families

Kelly Ann Sharman

International Migration and Ethnic Relations One-Year Master’s Thesis

15 Credits Spring 2020

Abstract

The aim of this research is to gain an in-depth understanding of involuntary immobility as it applies to American parents that aspire to migrate to Global North countries. It explores their reasons for desiring to emigrate, the obstacles rendering them involuntarily immobile, and examines how current research methods, models, and theories can be applied to these families. This qualitative study is based on six semi-structured interviews with American parents that have expressed aspirations to migrate but have not yet found a viable path to migration. It uses aspiration-ability/capability models to explore each family’s (im)mobility and the obstacles that render them immobile. The results of the research demonstrate the challenge of assessing (im)mobility at a single moment in time, and determine that the immobility of adult dependents can render an individual immobile.

Keywords: Immobility, Mobility, American Emigration, Global North-North migration,

Aspiration

Table of Contents

Abstract 1 1. Introduction 4 1.1 Aim 5 1.2 Research Questions 5 1.3 Delimitations 6 2. Contextual Background 7 2.1 Migration Aspiration 7 2.2 Paths to Migration 8 3. Literature Review 9 3.1 US Emigration 9 3.2 “Elite” Migrants 11 3.3 Migration Aspirations 12 4. Theoretical Framework 134.1 (Im)mobility & The Two-Step Approach to Migration Research 14

4.2 Cumulative Causation Theory 18

4.3 Push/Pull and Quality of the Public Domain 18

5. Methodology 20

5.1 Semi-Structured Interviews 21

5.2 Epistemology 23

5.3 Iterative Inductive Approach 23

5.4 Validity & Reliability 24

5.5 Role of the Researcher 25

5.6 Ethical Considerations 25

5.7 Participant Profiles 26

6. Results & Analysis 27

6.1 Aspirations 27

6.2 Motivations 28

6.3 Obstacles to Migration 31

6.4 Voluntary vs. Involuntary Immobility 33

6.5 Migration Sacrifices 38

6.6 The Question of Permanence 40

6.7 Past Migration Experience 41

6.8 The Covid-19 Effect 42

6.9 “Imagined Alternatives” 43

7. Conclusion 43

7.1 Concluding Remarks 43

7.2 Suggestions for Further Research 46

Reference List 47

Appendix 51

Appendix 1: Gallup World Poll, 2019 51

Appendix 2: Interview Questions 52

1. Introduction

With the United States still considered the top destination country for immigrants from around the world (Esipova, et al. 2018), the desire of Americans who aspire to emigrate is 1 generally overlooked in both the study of migration, and by the world at large. However, with 50 years of income stagnation (Desilver 2018), ever-growing inequality, and now two

generations of Americans (Gen X & Millennials) doing worse economically than their parents (Dickerson 2016), it would be understandable purely on economic grounds why Americans might want to emigrate.

The US middle class has been decimated (Temin 2017). Educated young and middle-aged Americans have been downwardly mobile despite being more educated than preceding generations (Schmitt, et al. 2018). Considering the limited access to quality education across economic classes, job instability, lack of affordable healthcare, lack of affordable childcare, the absence of family leave policy, inequality for women, an epidemic of gun violence… it is more and more understandable why younger people, especially women (who are

disproportionately affected by these issues), desire to leave (Ray & Esipova 2019) . When 2 many Americans look at their peers in Europe, they see populations with more gender equality, greater mobility (both social and physical), less debt, and better opportunities for their children's futures. “In different parts of the world, involuntary immobility has become a central concern for people who have lost a strategy for creating a better life for themselves and their families” (Carling 2002: 7).

Involuntary immobility refers to those that aspire to migrate and yet are unable to do so. While citizens of wealthy, developed countries have greater mobility in the world than those from poorer, less developed countries (Carling & Schewel 2018: 956), it is a false assumption that being from a wealthy nation and/or possessing a college education means that one has the capability to migrate. While one might have ease of travel if their finances allow for it,

1 While the word “American” can be used to describe citizens of any country in North or South America, it is

the word most commonly used when referring to citizens of the United States. As such, in this paper, the word “American” is solely meant to represent United States citizens.

2 See Appendix 1 for results from Gallup’s 2019 migration aspiration poll.

that is very different from being able to immigrate, especially if your desired destination is another Global North country where the cost of living can set a higher bar for employment, 3 and migration controls can be stricter.

In 2007, Favell, Feldblum, & Smith put forth a research agenda to fill a gap in the study of so-called “elite” migrants because migration studies “are more attuned to thinking about immigrants and immigration at the lower end of the labor market and then usually in terms of minority race, ethnicity or culture.” As such, they sought to “open up opportunities for researchers seeking to resist the clichéd opposition of “elite” and “ethnic” migrants in a polarized global economy” (25). In 2019 Schewel argued against the mobility bias in

migration studies that focuses primarily on migration while giving less thought to those who do not migrate, whether voluntarily or involuntarily, stating that in order “to better

understand contemporary mobility dynamics” researchers should examine immobility and the reasons why the vast majority of the world does not migrate internationally (20). This study is designed to begin filling these two gaps in the study of migration by focusing on this

neglected population in the field of migration studies and how they experience involuntary immobility.

1.1 Aim

The aim of this research is to gain an in-depth understanding of involuntary immobility as it applies to American parents that aspire to migrate to Global North countries.

1.2 Research Questions

1. What are the reasons American parents aspire to migrate?

2. What are the obstacles rendering American parents that aspire to migrate involuntarily immobile?

3 The term “Global North” generally refers to the more economically developed countries of the world. (Odeh

2010: 1)

1.3 Delimitations

This study specifically focuses on involuntary immobility as it is experienced by American parents, utilizing semi-structured interviews with one parent from each family. For the purposes of this study, parents with children between the ages of 0 and 18 were interviewed. The reason behind this is twofold: first, because the study explores how being a parent influences migration aspiration and realization; and second, when it comes to immigration, residency permits are generally limited to a select category of immediate family—parents and their minor children. The choice to focus on parents in particular is because the impulse to create a better life can become more profound when one has children, while having children to support and care for can make the migration process much more challenging.

In focusing on immobility, another delimitation of this study is to limit interviewees to US citizens that do not have dual citizenship or a familial path to acquiring a second passport. This is because a second passport can open up migration opportunities that are closed to most Americans. Additionally, as it can be easier to migrate to less developed countries, a further delimitation is the desired migration of American parents to countries of the Global

North—countries with ostensibly more strict immigration policies and more stringent requirements for those seeking to reside and/or work within their borders.

For the purposes of this research on immobility as it pertains to emigration, immobility will be defined as lacking the capability to become a long-term immigrant in a Global North country. A long-term migrant is generally defined as one residing in a host country for more than 12 months. This study takes these factors into consideration and questions interviewees’ on their migration aspirations with regards to time (permanent versus long-term migration).

2. Contextual Background

2.1 Migration Aspiration

In 2002 Carling suggested that we are living in an “age of involuntary immobility” (5). Recent survey and migration statistics support that proposition. The Gallup World Poll estimated that 15% of the world’s adult population between 2015 and 2017 aspired to permanently migrate (Esipova, et al. 2018), “which is much higher than the proportion of actual migrants, about 4%” according to the OECD in 2015 (Carling & Schewel 2018: 951). Based on the US Department of State’s estimate of Americans living abroad (9 million), and based on a rounded down count of total US citizens at home and abroad (338 million) (US Census Bureau), approximately 2.7% of American citizens live abroad in 2020, which puts them below global averages despite the fact that Americans have greater travel mobility than many commonly studied migrant populations.

However, in response to Gallup World Poll’s question: “Ideally, if you had the opportunity, would you like to move permanently to another country, or would you prefer to continue living in this country?” 16% of Americans would prefer to emigrate (Ray & Esipova 2019). The use of the word “permanently” is problematic and can lead to excluding potential

emigrants from inclusion in these statistics, but comparing this number to Gallup’s global averages where the same question was posed, Americans now have a higher desire to migrate and yet are doing it less.

In their 2014 survey of Americans’ aspirations to live abroad, Marrow & Klekowski von Koppenfels came up with a much higher number. According to their study as many as 33% of American citizens have the desire to live abroad (2020: 83). Though the US Department of State’s estimate of US citizens living abroad jumped dramatically from 6.3 million in 2012 to 9 million in 2016 (Marrow and Klekowski von Koppenfels 2020: 84), the percentage of citizens living abroad still has not gone above 3%. This thesis studies a handful of the roughly thirteen to thirty percent of Americans that are not migrating despite aspiring to do so.

2.2 Paths to Migration

As both Favell, et al. (2007) and Docquier, et al. (2014) pointed out, being able to easily acquire a tourist visa may help with migration in some respects, but it does not make it a frictionless experience and often is simply not enough to enable the migration that many aspire to. Tourist visas generally end after a 90 day stay and very rarely allow for local employment. Aside from the ability to use it to attend a job interview, a tourist visa really is best at facilitating irregular migration, which is not something most Global North parents would be willing to risk.

In the Global North there are very few paths to immigration for US citizens. The primary paths are securing a job in the destination country, marriage, education, and self-sufficient or non-lucrative immigration (which enables one to acquire residency but not a work permit). For those that do not have jobs that allow them to work remotely in any country they please, finding a job in a developed destination country from the United States is generally the only viable path to immigration when families do not have a surplus of savings to support them using methods like student immigration. Furthermore, some countries (such as Sweden) do not even allow self-sufficient immigrants. While some countries allow residency permits for people that can prove their ability to support themselves without a job (or work permit) located in their destination country, in Sweden you have to have a specific reason to be in the country. Even if a person can prove that they are able to support themselves without a job located in Sweden, they will not be permitted to immigrate there.

For most Americans aspiring to migrate to Global North countries, finding a job before departing the United States is the only viable path to immigration. Unfortunately, there are a very limited number of fields (tech, finance, medicine, science) that actively hire foreign nationals, and if you do not have a work history in these select fields, your chances of landing a job over a non-citizen are limited. For those qualified, there can be jobs in education, generally at international schools, however if one is moving to a fairly expensive country, the salaries for these positions make it difficult to support a family on one income, which is often necessary if a person has no spouse, or their spouse is unable to secure a job for themselves

as well. These factors can all lead to involuntary immobility for those that do not have the right qualifications to immigrate.

3. Literature Review

3.1 US Emigration

Despite the fact that there are estimated to be 9 million US citizens living abroad, very few scholars have researched American emigration. In 1992 Dashefsky, et al. wrote a

comparative study about Americans living in Israel and Australia and covered some ground on types of emigration, motivations behind it, and the factors that impelled American

emigrants to either stay in their host country or return to the United States. However, as stated by the authors, their study focused specifically on “those who are living in other countries of the developed world with a lower standard of living than that of the United States” (1992: v). In 2020 for Americans with Global North migration aspirations this would no longer be the case.

There are no definitive answers with regards to any one country’s standard of living ranking , 4 but the United States is not in the top 10 of any current lists and Australia (a focus of

Dashefsky, et al.’s study) usually ranks far above it. Worse than that are the common media headlines (Rolling Stone, Bloomberg, Forbes, The Independent) regarding the United States regressing into developing nation status for most people (McElwee 2014; Smith 2019; Asghar 2018; & Farand 2017), inspired in part by MIT economist Peter Temin’s 2017 book

The Vanishing Middle Class. One of the many reasons for declaring the US a developing

state for most citizens is its failed healthcare system, and unlike the US, both countries in Dashefsky, et al.’s study have universal healthcare. This state of decline makes Dashefsky et al.’s focus of interest in 1992 more applicable to research on Global North-South migration in 2020.

4 Standard of living usually refers to the “material aspects of an economy”—the number of “goods and services

produced and available for purchase”—and not quality of life (Amadeo 2020), and there are numerous ways of measuring it.

In 2012 Croucher argued for the use of the term diaspora when referring to Americans abroad stating that the use of “labels, such as ‘expat,’ perpetuates the political and analytical

invisibility of this group of migrants and the global networks they establish” (18).

Additionally she researched Americans living in Canada, and has written many articles about American emigrants in Mexico, which hosts the largest number of US citizens living abroad. She pointed out the peculiarity of the US response to its citizens abroad, largely ignoring their existence (beyond levying income tax from them), and having little to no interest in

compiling any data on them (Croucher 2011: 128).

Klekowski von Koppenfels has written many articles on American and Global North migrants, and in 2014 published a book on American migrants in Europe, specifically in Berlin, London, and Paris. In her study she found that the two most common reasons that US citizens migrate are marriage or partnership to a non-American, and the respondent or their partner getting a job offer or transfer (Klekowski von Koppenfels 2014: 51). She argued that Americans living abroad are rarely seen as migrants and that many prominent migration theories do not apply to them. Migration is popularly understood to be motivated either by economic factors (increasing income or “seeking employment”), or factors such as

“persecution, environmental devastation or conflict, forcing individuals to flee,” and these are not typically applied to Americans (ibid: 6).

Other areas of research include Van Hook, et al.’s 2006 study on methods for calculating the number of foreign-born residents (of the US) that had emigrated away from the United States, as well as several law articles about US tax laws “punishing” citizens that have emigrated, most citing the same particular study (Farkas-DiNardo 2005). Favell, et al. also touched upon this topic of taxation of US citizens abroad when they wrote about nations “globalizing their reach,” pointing out that Americans can face loss of citizenship if they fail to file tax returns, however it “can turn into a nasty catch-22 for dual citizens or permanent residents when they then find they cannot voluntarily ‘lose’ their citizenship or residence status unless they can demonstrate they are not giving it up for financial reasons” (2007: 22). While Klekowski von Koppenfels and Croucher have actively increased the amount of scholarship on the topic, American emigration is still an underrepresented area of migration studies.

3.2 “Elite” Migrants

Simply being from a wealthy country like the United States can relegate someone to the category of “elite” migrant regardless of one’s education level or transferable skills. Weinar & Klekowski von Koppenfels pointed out that migrants that emigrate from one Global North country to another country of the Global North are commonly “presented as non-migrants” often “characterized as ‘expatriates,’ ‘lifestyle migrants,’ ‘cosmopolitans,’ ‘Eurostars,’ as ‘elite migrants,’ ‘knowledge migrants’ or international or ‘mobile’ students” (2019: 172). These classifications can lead to the exclusion of large numbers of migrants in migration research and ignore the challenges faced by people who might be deemed elite or highly skilled but whose education or work experience don’t translate into a commiserate job (or any job) in their destination country.

The explosion of literature on migration is linked—quite rightly—to concerns with global inequalities, development, and the exclusionary workings of ethnicity and race. But with these kinds of concerns uppermost for most researchers, the field has not been well equipped to study or understand other forms of apparently “less

disadvantaged” migration except through a dismissive (“elites”) lens. (Favell, et al. 2007: 16-17)

In their work on immobility, Carling and Schewel join this dichotomous argument, pointing out “that the greatest barriers to migration are often restrictive immigration policies” which are not applied evenly “to different social groups or classes. They tend to facilitate movement of higher skilled people while simultaneously restricting it for low-skilled potential migrants” (Carling & Schewel 2017: 955). Unfortunately, the situation is not that simple. Not all

so-called “higher skilled” potential migrants can immigrate based on those skills regardless of their country of origin.

Favell et al. address “the question of who and what constitutes highly skilled migration” and point out how “higher-end migrants” are often referred to as elites in order to contrast them with more disadvantaged migrants. Simply having a college education can put someone in the “highly-skilled” category but that “obscures the hard realities of the many highly skilled,

educated migrants who cross borders as unskilled migrants leaving their unconvertible human capital, as it were, behind at the border” (Favell, et al. 2007:16). Having a college education is quite simply not enough to enable one to migrate, though it often puts a potential migrant in the “highly skilled” category. Possessing the right degree and the right work experience are vitally important in securing a job in another country. If your profession is not in demand, if you don’t possess necessary language skills, or if your diplomas are not enough to permit you to work in your field, you may be forced to start over in another field of employment, or at best, be required to engage in more educational courses in order to make your professional experience transferable. Becoming a student again is often a last resort, requiring an amount of discretionary savings that most people do not have.

This characterization of Global North migrants as “elite” seems hardly fitting considering the challenges most potential migrants would face coming from a country like the United States. Favell, et al. pointed out that the “real” elites of the world have regular access to international travel “as well as a far better chance of success in their chosen career at home—without needing to propel themselves individually on an international stage.” Whereas, the “so-called elites” that are migrating, or aspiring to migrate, often do not come from elite backgrounds at all but are those who have frustrated careers at home and have taken the gamble of a move abroad in order to “improve social mobility opportunities that are otherwise blocked at home” (Favell, et al. 2007: 17). In the case of two generations of Americans it is not just a matter of seeking greater social mobility, but also an attempt to stave off the downward mobility that has become the norm in the past several decades.

3.3 Migration Aspirations

Research polls on migration aspirations by Gallup tend to survey people regarding

“permanent” migration, however that word can be limiting and exclude people that seek to be long-term migrants but are not necessarily committed to permanence yet. As stated by Magali & Scipioni, “the inclusion of words such as ‘permanently’ might unnecessarily restrict the analysis to a form of migration that excludes circular or temporary migration, or simply an aspiration to migrate which has not factored in a pre-defined duration” (2019: 185). In

Klekowski von Koppenfels’ research on American migrants in Europe she pointed out that many long-term or permanent migrants started out as temporary migrants that ended up staying more permanently (2014: 7). Thus, the wording of Gallup’s polling question isn’t the best representation of migration aspiration, or predictor of actual migration, which often occurs without the initial intention of permanence. However it appears to be the only global survey on migration aspirations allowing for comparisons between countries, and with global averages.

In 2020 Marrow and Klekowski von Koppenfels published the first study of American migration aspirations “from the point of origin” (84). Similar to other areas of migration research, studies of migration aspirations tend to suffer from both the “mobility bias” (focusing on aspirations retrospectively after migration has already occurred), and when scholarship is gathered at the point of origin, it “centers primarily on flows originating in the Global South offering little insight on how migration aspirations arise among Americans or other residents of economically advanced countries in the Global North” (Marrow & Klekowski von Koppenfels 2020: 85). Marrow and Klekowski von Koppenfels sought to begin filling that research gap with their survey on migration aspirations. They gathered a great deal of information on American migration aspirations, “identifying broad patterns and variation among potential migrants within a representative sample,” however they pointed out that this is a jumping off point for qualitative research to gain a deeper understanding of American migration aspirations at the micro-level.

4. Theoretical Framework

Weinar & Klekowski von Koppenfels introduced a special section of the journal

International Migration about integration in Global North-North migration in which, like

Favell et al., they argued that the “...near-total exclusion of migrants from the Global North within mainstream migration theory has undermined the widespread applicability of those theories.” They sought to broaden “the applicability of migration and integration theories to all migrants, regardless of country of origin or destination” (Weinar & Klekowski von Koppenfels 2019: 172).

4.1 (Im)mobility & The Two-Step Approach to Migration Research

Sheller and Urry looked at a growing body of research that had begun in the 1990s and described it as “The New Mobilities Paradigm” (2006). Prior to this “mobility turn” in social sciences it was taken for granted that sedentarism was normal and migration was the

“aberration,” consequently, those that did not migrate were largely ignored in migration studies (Schewel 2019: 4-5). The New Mobilities Paradigm laid out a diverse array of “mobilities,” and defined a new language and perspective from which to examine migration. While sedentarism and nomadism had long existed in theories about migration (Sheller & Urry 2006: 210), the new mobilities paradigm took a more nuanced approach, where neither was considered the norm, and neither was deemed good nor bad. Though the mobility bias in migration studies remained, scholarship on immobility began to challenge accepted

narratives. Among other things, globalization began to be re-examined from a migration perspective, where, rather than dissolving borders, it produced “processes of closure, entrapment, and containment” (Schewel 2019: 5).

Favell, et al. in particular sought to challenge the assumption that globalization led to an increase in human mobility as it did for businesses and products, and called for future research that would examine “the supposed liberalization of human mobility in the world economy” (2007: 16). They suggested that a better way to test this “liberalization” would be to study the mobility of those who are deemed to “face the least barriers linked to exclusion, domination, or economic exploitation” (ibid:16). Gaining an understanding of these

experiences “would reveal not just how far liberalization might go under ideal conditions, but also reveal, in sharp relief, what persisting limitations there might still be to a completely unfettered global economy of mobility” (ibid:16).

As Carling stated, “the hyperglobalist view that `geography no longer matters’ is hardly a relief to the involuntarily immobile” (2002: 8). His take on the “mobility turn” challenged traditional migration theories that do not account for why people do not migrate when theory predicts that they would do so. In particular he called into question neoclassical migration

theory that “emphasizes the role of income differences” in migration, pointing out that despite glaring disparities in global standards of living, migration levels have largely remained the same (ibid: 9)—at least 96% of the global population does not migrate

internationally. Traditional theories have generally failed to account for why that is the case.

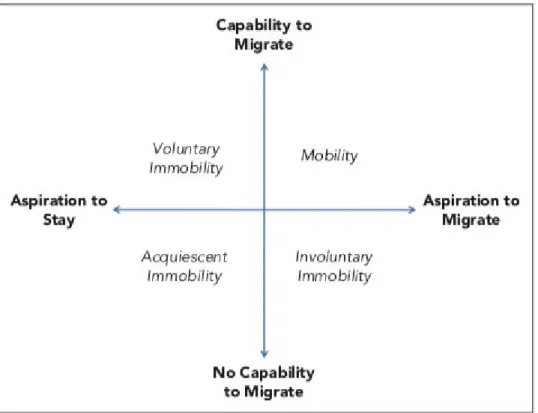

Carling coined the term “involuntary immobility,” declaring that “our times are characterized by involuntary immobility as much as by large migration flows” in his study of emigration from Cape Verde (2002: 5). In that study he created his aspiration/ability model of migration (Figure 1). While aspiration and ability were not new concepts, his model enabled researchers to recognize mobility outcomes and consequently ask questions about them (Schewel 2019: 7).

Figure 1: Carling’s aspiration/ability model.

In this model, a migration ‘aspiration’ is defined simply as a conviction that migration is preferable to non-migration; it can vary in degree and in the balance between choice and coercion... Among those who aspire to migrate, some have the ability to do so, manifest in their actual, observable migration. Those who do not migrate fall into two categories: involuntary non-migrants, who have aspirations to migrate but lack the

ability, and voluntary non-migrants, who stay because of a belief that non-migration is preferable to migration. (Carling & Schewel 2018: 946)

It also includes outside forces affecting the aspiration to migrate and the ability to do so.

Carling’s model applied a two-step approach to studying migration, first evaluating “migration as a potential course of action” (such as analyzing an individual’s aspirations), and second, examining “the realization of actual mobility or immobility at a given moment” (Schewel 2019: 17). This two-step approach has subsequently been utilized by many

scholars.

Drawing upon the work of Sen and de Haas, Schewel created the aspiration-capability framework (Figure 2) which both simplified and expanded upon Carling’s model—assessing mobility, involuntary immobility, acquiescent immobility (those who do not wish to migrate and are unable to do so), and voluntary immobility—by examining the capability to migrate, or the lack thereof, and the aspirations both to stay or to migrate (2019: 8). The addition of acquiescent immobility into Schewel’s framework was also intended “to challenge dominant migration theories” that assume that people from low income countries desire to move to high income countries (Carling & Schewel 2018: 957). She pointed out that there are some people “for whom the very idea of ‘migration decision-making’ is irrelevant; the possibility of migrating, the weighing of its potential benefits and costs, is never consciously considered” (Schewel 2019: 18-19).

Figure 2: Schewel’s aspiration-capability framework.

Schewel further stated that the aspiration-capability framework did not have to be limited to “‘developing country’ contexts” (2019: 7). She recognized the work of Sen in saying that “expanding people’s capabilities to lead the lives they value is a relevant concern for every society,” and pointed to de Haas’ argument “that people derive well-being from having the freedom to move or to stay, regardless of whether they act upon that freedom” (ibid: 7-8).

In the research agenda on immobility that Schewel put forth, she called for future research to “examine (im)mobility aspirations relative to both internal and international boundaries,” because moving “within one’s country is often more viable” than moving internationally. Schewel called internal migration aspirations “imagined alternatives” to international migration (2019: 18). This is something that could be particularly applicable to Americans who tend to have a high degree of internal mobility.

4.2 Cumulative Causation Theory

Cumulative causation theory, among other things, asserts that “prior migratory or international experience increases the likelihood of repeat migration” (Klekowski von Koppenfels 2014: 48). This prior experience is said to not only reduce the “real and

psychological costs” of migration but can also affect migrants’ motivations as they acquire new tastes and “aspirations for socio-economic mobility” (ibid: 48). This socio-economic impact is complicated when it comes to American migrants, particularly those that migrate to countries in the Global North. Many will experience a pay cut when migrating and not necessarily improve their socio-economic status, though possibly see an increase in their quality of life (van Dalen & Henkens 2013: 236). This study examines these questions by inquiring about past migration experiences and how they may have affected interviewees’ aspirations to migrate.

This research also examines how past migration experience has influenced interviewees’ perceived ability to migrate. With prior experience having an effect on the likelihood of migration it is natural that it would also impact the involuntarily immobile. Bringing the aspiration-capability model together with cumulative causation theory, if past experience and aspiration both lead to eventual migration for those with the capability to do so, one must examine how past migratory experience affects the involuntarily immobile. Do they perceive themselves as more or less mobile based on their past experience, and has this experience impacted their desire to migrate?

4.3 Push/Pull and Quality of the Public Domain

In their study of emigration intentions and subsequent behaviours of native born Dutch residents, van Dalen and Henkens surveyed citizens with the intention to emigrate and then followed up with them 5 years later to see if professed intentions led to behaviour. They also wanted to understand why people emigrated from a wealthy nation such as the Netherlands. They found that “the strongest contributors to the motivation to move abroad” were

personality traits of potential migrants (specifically self-efficacy and sensation-seeking) and 18

“their discontent with the quality of the public domain” (2013: 225). Their study found that these “are strong driving forces in relation to emigration, even given the loss of income to be expected by a substantial number of emigrants” (ibid: 236).

Economic theories tend to reduce the motivation to migrate to a cost-benefit analysis of potential wages and an increase of wealth over time. This can be difficult to apply to Americans migrating to other Global North countries where wages can often be lower and taxes are generally higher. Van Dalen and Henkens demonstrated that this is also a factor for Dutch emigrants. Migration does not necessarily correlate to an improved professional title or salary. Van Dalen and Henkens took on the view that potential migrants are also motivated by “the expectation of improved satisfaction with public goods or public amenities” as well as how well the government is perceived to function and address societal issues (2013: 228). Migali & Scipioni support this in pointing out that “satisfaction with local amenities and conditions” including “healthcare and confidence in public institutions are negatively associated with the aspirations to migrate” (2019: 183). Additionally they cited the

connection of increasing levels of education with an increase in migration aspirations when education levels are not met with “adequate opportunities” (Migali & Scipioni 2019: 184).

What both van Dalen and Henkens, and Marrow and Klekowski von Koppenfels found in their studies was that potential migrants were significantly motivated by the “push factor” of “dissatisfaction with the public domain” (van Dalen & Henkens 2013: 236). The theoretical concept of push and pull factors in migration harkens all the way back to Ravenstein’s 19th century analysis of migration and was expanded upon over time (Samers & Collyer 2017: 59). It refers to the idea that there are “a set of factors that ‘pushed’ migrants from one region... and a set of factors that ‘pulled’ them to another region” (ibid: 59). 49% of

American respondents aspiring to migrate said that push factors—“to leave what I consider a bad or disappointing (economic, political, personal, healthcare, etc.) situation in the United States”—were one of their top 3 motivations to move abroad (Marrow & Klekowski von Koppenfels 2020: 93). Van Dalen and Henkens declared that this push factor “is crucial to grasping the reasons for emigration from a high-income country” (2013: 236).

5. Methodology

This study utilizes both steps in Carling’s two-step approach to understanding the migration process, first in gaining an understanding of each interviewee’s aspirations, and then

examining their capability to migrate and how they experience immobility. Both Carling’s aspiration/ability model and Schewel’s adaptation of it—the aspiration-capability framework (2019) are used to help analyze the interviewees’ (im)mobility. Schewel promoted the use of “micro-level case studies and more qualitative methods” in operationalizing Carling’s two-step approach in order to gain more “nuanced insight” into migration aspirations and “how people experience and make sense of their immobility at a given time” (Schewel 2019: 19).

Interviewees were recruited with a public social media posting looking for “American parents (with children ages 0-18) who believe that migrating to another country would be preferable to staying in the United States, but have not yet found a viable path to migration.” The people that responded were given a more detailed account of the research project and I confirmed that they fit some basic criteria of immobility (not having access to a second passport or a job that could transfer them internationally). While I did not seek out a specific gender, all of the respondents that ended up fitting those criteria of immobility were female (all of the men that responded had already succeeded in emigrating, and reached out expressing their deliberate decision to raise their children abroad).

Though an aspiration to migrate to a Global North country was a delimitation for this study, no potential interviewees reached out to me with non-Global North aspirations. In Marrow & Klekowski von Koppenfels’ aspiration survey of US citizens, 61.3% of their respondents aspired to move to Western Europe, Australia, New Zealand, or Canada (2020: 91). All of the potential interviewees that responded to my posting were focused on immigrating to this group of countries. Consequently, I did not have to select out Global North aspiring migrants from those that responded. It is possible that the second criteria in qualifying for this study, having “not yet found a viable path to migration” eliminated those aspiring to migrate to countries in Latin America, where Mexico hosts the largest number of US immigrants in the

world (Klekowski von Koppenfels 2014: 30), and immigration regulations can be less restrictive.

5.1 Semi-Structured Interviews

For this research, semi-structured interviews were conducted with six mothers, including single mothers and those with partners and spouses. In two-parent households, only the parent that volunteered for the study was interviewed, however, when an interviewee had a partner or spouse, that partner’s potential mobility was also taken into consideration because the pathway to mobility for a nuclear family typically relies on only one parent becoming eligible for migration.

Interviews are a method of data creation (6 & Bellamy 2012: 9). With semi-structured interviews, the researcher is able to control the questions that are administered (ibid: 75), while at the same time allowing for flexibility with the inclusion of open ended questions which “enable the interviewer to capture unexpected issues and information” (Somekh & Lewin 2004 : 42). Semi-structured interviews were chosen instead of a survey because they allow the interviewer to achieve a better understanding of responses by giving both the researcher and interviewees the opportunity to clarify any confusion or misunderstandings along the way. This allows for a higher degree of validity by attempting to lessen the amount of misinterpretation that can occur in a more structured survey. The interviews are intended to complement survey research like that conducted by Marrow & Klekowski von Koppenfels on American migration aspirations (2020).

Semi-structured interviews gave the interviewees the opportunity to steer me away from any preconceived ideas I may have had about their aspirations and circumstances, while at the same time allowing me to guide the interview towards achieving the study’s theoretical aims. This method gave me the opportunity to ask follow up questions specific to the interviewees’ answers in order to gain more clarity and greater understanding. It also gave the interviewees the opportunity to follow their own train of thought, with the questions used as a jumping off

point. The method allowed for more dynamic answers as the interviewees were able to expand on their thoughts as they saw fit.

The parents in this study were interviewed about their migration aspirations, their past experiences (if any) with emigration, where they desire to immigrate to, the factors

preventing them from doing so, and what they might be willing to sacrifice in order to realize their migration aspirations (see Appendix 2). Often many of the questions were answered before I ever asked them directly, however as I worked my way through the list of questions, they were given the opportunity to expand further on a subject they may have addressed previously. I find that this method facilitated a much more detailed and nuanced

understanding than could be discovered via a more structured interview or survey. Not every question was open ended, however those that were not, usually led to longer responses because the interviewees wished to explain the reasoning behind their answers.

The interviews were conducted via Skype between 22 May and 5 June 2020. The audio of the interviews was recorded then later transcribed. For the most part this worked quite well. The interviewees were all very candid and relaxed, and did not come across as impeded by the fact that they were being interviewed over Skype. Due to Covid-19 quarantines, interruptions by children were common, but didn’t significantly interfere with the flow of the interviews. Severe weather conditions at one interviewees’ location interrupted internet service and we had to conduct the interview in two parts over the course of two days. We were able to get back on track on the second day, and I was able to follow up and clarify some answers from the previous day. The first couple of interviews were about an hour long—the interviewees would often drift off into tangents or become curious about my own immigration history. As I gained more experience, the interviewees tended to lose focus less often and subsequent interviews lasted about 30 minutes each.

At the end of the interviews I gave the interviewees the opportunity to express any thoughts that they felt might have been missed during the course of the interview. I did this in order to ensure that my own preconceived ideas that led to the formation of my interview questions did not blind me to any aspects of aspiration and (im)mobility that were important to my

interviewees. Those that did have a response to this question further elaborated on topics that had previously been covered. It gave them the freedom to express their thoughts as they saw fit without any formal constraints.

5.2 Epistemology

The aim of this study is to gain an in-depth understanding of involuntary immobility as it applies to American families that aspire to migrate to Global North countries. This intention of understanding is epistemologically subjectivist and is connected to what Max Weber—one of the founders of modern sociology—“called Verstehen (empathetic understanding)”

(Rosenberg 2015: 53, 157). It is an attempt to make sense of human action in context. Weber felt that “beliefs and desires are also reasons for actions: they justify them, show them to be rational, appropriate, efficient, reasonable, correct. They render them intelligible” (ibid: 43).

This research examines the desires of American parents with regards to international migration, and their beliefs about their own (im)mobility, or capability of achieving those desires. Real world obstacles hinder the migration process for most people that desire to migrate, however it is one’s subjective beliefs with regards to those obstacles that can have a determinate effect on how they take action. This study explores American parents’ beliefs with regards to their ability to migrate.

5.3 Iterative Inductive Approach

Inductive research begins with a question and seeks to develop a hypothesis from the data that is collected, rather than use the data to prove whether or not a previous hypothesis holds true (6 & Bellamy 2012: 76). In this case, the aim is to learn about the motivations behind migration aspirations and the obstacles preventing them from being realized in order to develop an understanding of involuntary immobility in an understudied population.

“Inductive research is not designed to be cumulative, which is why it is often used in fields where there is a dearth of previously published work” (ibid: 76). Both immobility and research on so-called “elite” migrants are neglected areas in migration studies, with only

quantitative research having been conducted on the topic of American migration aspirations, there is a need for more in-depth qualitative work to better understand aspiration and

(im)mobility in this population.

An iterative approach allows for a “dialogue between theory and empirical evidence,” where theory can help form an initial line of enquiry and subsequently “new ideas and evidence may cause them to develop new lines of theoretical enquiry…” (6 & Bellamy 2012: 106). As 6 & Bellamy state, “case-based researchers can, and should... be prepared to recast theory in the light of changing empirical evidence” (2012: 106). It is thus important to keep an open mind when conducting interviews so that they can lead the researcher in new directions that might not have occurred to her prior to collecting evidence. This process has been highly iterative, with a constant re-examination of theory and discovery of new ideas and approaches to immobility based on the interviewees’ responses.

5.4 Validity & Reliability

As previously stated, the method of semi-structured interviews was chosen in order to achieve high internal validity in this research. Themes were approached from different perspectives throughout the interviews in order to gain the most detailed understanding of each interviewee’s migration aspirations and immobility. The nature of this method and the limited number of participants precludes a great degree of external validity or the possibility of making any major generalizations.

When it comes to reliability, if you define it as being able to repeat the same research and achieve the same results, this study will have low reliability. However, I have sought to increase the reliability through transparency. The method of choosing participants, and the questions used as a framework for the semi-structured interviews (Appendix 2) are included in this paper. With the practice of interviewing individuals, it is not reasonable to expect to receive the same answers when every person has their own subjective interpretation of their experiences. That said, the interviewees did have some common ground when it came to their aspirations and obstacles, despite having diverse experiences with immobility.

5.5 Role of the Researcher

My motivation for conducting this research was a combination of my own experiences with involuntary immobility and conversations I had with other parents while I was still living in the United States, where they too expressed a strong desire to emigrate but lacked the ability to do so. My own immobility history dates back to when I was a university undergraduate student and wanted to immigrate to the UK in order to pursue better career opportunities, however my American citizenship prohibited me from being able to gain a work permit, so I remained in the United States. Later on I moved to Berlin irregularly and new friends guided me through the process of making myself legal, however I lived for 3 years without a work permit (juggling multiple cash paying jobs to make ends meet), and eventually was forced to return back to the United States when new immigration regulations would have significantly increased my cost of living.

While my history definitely biases me to be more empathetic towards my interviewees, it also helped inform the questions I asked during my interviews—having experienced many of the obstacles and dilemmas I addressed in my questions. My own first-hand experience with involuntary immobility enabled me to be more relatable to my interviewees, allowing them to be more relaxed and open with their responses. While this knowledge and experience could be an asset, it was also important not to enter into the interviews with any preconceived notions or expectations about the interviewees’ personal experiences and thoughts. The interviewees came from diverse backgrounds and I do not believe that my biases undermined my goal of understanding their very diverse experiences with immobility. I kept an open mind throughout the process which enabled me to see immobility from different perspectives and made this research a more iterative process.

5.6 Ethical Considerations

The purpose and aim of the study was made clear to all interviewees and they were assured anonymity in this research paper. With participant approval, interviews were recorded for transcription purposes only and will be destroyed upon completion of the thesis evaluation

process. All interviewees were issued a consent form that clearly laid out the purpose of the study and delineated research protocols with regards to their personal information.

Interviewees retained the right to withdraw consent at any time, and were emailed copies of their consent form stating all of the above. Before conducting the interviews I asked the interviewees if they had any questions about the consent form and reiterated that the interviews would be recorded.

5.7 Participant Profiles

In order to protect their anonymity, the participants’ names have all been changed.

Allison is a widowed mother of five children (ages 15-22). She lives in a suburb of Kansas

City, is in her mid-40s, and is a homeowner. She holds a BSN degree in nursing. Allison is a US citizen that grew up in Canada and would like to return. She has been working for 13 years to qualify for Canadian immigration and will finally be eligible in early 2021.

Bridget is a mother of one child (4 years old) in Portland, Oregon. She is in her early 40s and

owns a store. Her partner is a stay at home father with a film background. She has a

bachelor’s degree, and her partner has an associates degree. Bridget spent a few years living in Germany after a job took her there on a temporary assignment. She and her partner would like to immigrate to Europe.

Kara is a single mother of one child (18 months old). She lives with family in a suburb of

Seattle, and is in her late 20s. She is a trade school graduate with certifications in two fields. Kara spent five months living in Ireland irregularly hoping to stay but unable to find a viable path to legal immigration. Her daughter was conceived there, but she does not have

documentation to prove her daughter’s Irish heritage. She would like to return to Ireland.

Denise is a single mother of one child (4 years old). She lives in Austin, Texas, is in her

mid-40s, and is a homeowner. She is an engineer with a master’s degree. She participated in a

master’s program in Sweden and would like to return to live there, though she has considered other countries as well.

Elizabeth is a married mother of three (ages 0-7). She lives in a suburb of Seattle and is in her

early 30s. She and her husband are homeowners and both hold bachelor’s degrees. She is a stay at home mother with a background in childcare and preschool teaching, her husband works in middle management. Elizabeth and her husband spent time teaching in Korea prior to having children. They would like to immigrate to Europe but believe that they probably have a greater chance of immigrating to Canada.

Joan is a married mother of three (ages 9-16). She lives in a suburb of Kansas City, is in her

early 50s, and is a homeowner. She has a JD, MBA & an MA. Her husband has an MA. She is an attorney, and her husband is a stay at home father with a background in college

administration. Joan and her husband like the idea of living in Canada, but haven’t ruled out other socially progressive countries.

6. Results & Analysis

6.1 Aspirations

In the two-step approach to studying migration that Carling developed, aspiration is defined as “the conviction that leaving would be better than staying” (Carling & Collins 2018: 915). In being selected for this study, all interviewees stated (and reiterated in their interviews) that they believed that for their family migrating to another country would be preferable to staying in the United States.

The interviewees stated that they aspired to immigrate to Canada, Europe, or New Zealand. Some found Canada to be the best possibility, while others deemed their selective

immigration regulations too difficult to overcome:

I’ve looked into Canada also, but it’s hard. They don’t take Americans. (Denise)

When it came to Europe, interviewees tended to only have a general idea of migrating somewhere in Europe (Northern Europe being the primary focus), though Kara and Denise were focused on Ireland & Sweden (respectively), based on their past experiences living in those countries and wishing to return.

Denise expressed a sense of alienation regarding her aspiration to migrate:

I see so many things as options that it’s a constant struggle and some people just don’t at all. They don’t at all. So like, “oh, Denise why are you constantly thinking about moving to Sweden?” Well, because it’s an option. It’s an option to make your life better. And I think that if you are one of those people you see it as an option, but a lot of people just don’t. (Denise)

This comment ties back to Schewel’s description of acquiescent immobility in the

aspiration-capability framework—those for whom migration is never a consideration—while the involuntarily immobile, like Denise, see that the possibility of migration exists even though they themselves may be unable to realize it.

6.2 Motivations

I initially inquired about the interviewees’ motivations for migrating by asking for how long they have desired to emigrate. Allison has wanted to emigrate since 2007 when her two year old son was having treatment for a tumor. At the time she had good health insurance because of her husband’s career in the military. Her son’s medical team let her know that she was very lucky to have that insurance because she had a “million dollar baby.” Around her at the children’s hospital she encountered families in financial ruin because of their children’s health problems, and she wanted to leave the US for Canada, where she had experienced universal healthcare growing up. Things became even more difficult after she became a widow a year later, and they lost their health insurance for a period of time. Though she has since had what by American standards is considered excellent health insurance because she does not have to pay monthly premiums, the out-of-pocket medical expenses (co-pays, etc.) have been very high. She related a story about her brother moving to the US from Canada with his family for a job opportunity and being forced to move back because the expenses for

his son’s diabetes were so high that it was more cost effective for him to be unemployed in Canada with universal healthcare, than employed in the United States with American health insurance.

Denise stated that she has wanted to migrate since 2008, not stating any single catalyst but rather a whole list of motivations that she has had for many years. Bridget has wanted to emigrate since she returned from Berlin in 2012 following a temporary work assignment that sent her there for a few years. Both Kara and Elizabeth have wanted to migrate since having children, and Joan stated that she has wanted to emigrate since Donald Trump was elected president in 2016.

Later, I more specifically asked why they desired to migrate (seeking further elaboration if the question had not already been answered). This question of motivation often required more probing because several interviewees would begin by answering the question with something along the lines of, “isn’t it obvious how awful the US is?” and I would have to ask them to be more specific.

There’s just so many more opportunities available, which is interesting, it used to always be like, “America land of opportunity,” but I feel like the opportunities in America have gone down so dramatically. (Kara)

Everybody’s working remote now, so why does it matter where you are anyways, other than agreeing with the quality of life and the way other people choose to live? (Bridget)

The top two motivations for emigrating were to move to countries that are more progressive, and to those that have better social welfare systems (including childcare).

We had Obama and we had kind of a little bit more of a progressive government and it looked like things were moving in a good direction, not perfect, but things were going in a way that was more close to the way things have been in Canada for more than 40 years. Like really, the US is really behind the curve on a lot of progressive issues… People are living in, they live in perpetual poverty, frankly. Because we

have very few social programs, we have no universal healthcare, so everybody has to pay for everything by themselves, and yet they all live paycheck to paycheck, and so it’s very difficult to think of the needs of your grandchildren and your great

grandchildren when you can barely pay for the milk on your table. (Allison)

These motivations were followed by wanting to move to a country with better schools and educational opportunities for their children. The following motivations came up with half of the interviewees: wanting to live somewhere with universal healthcare; seeking a better quality of life, including work/life balance; wanting to live in a culture that is better for women and girls; and wanting to escape American culture, which they consider to be negative in a variety of ways. Bridget’s experience living in Germany exposed her to a different culture around families:

I think after seeing, especially as a parent, seeing the children and the type of schooling... they're just really happy, they’re well behaved… and they also are included in a lot of the culture. Whereas here we like to say, “oh I’m going to

somebody’s house, you’re going to get a babysitter, we’re going to leave you there,” instead of including them… That’s normal there. (Bridget)

Other qualities that they were seeking in a new country were better environmental policies, living somewhere safer and with fewer guns, more equality, and greater access to travel and other cultures.

While van Dalen and Henkens consider dissatisfaction with the public domain to be a push factor, in looking at how my interviewees described their motivations, I would argue that push and pull are two sides of the same coin. They want to leave a country that they are dissatisfied with to move towards a country more in line with their values, that offers a better quality of life despite financial and “private domain” sacrifices that they expect to make as immigrants. As much as they want to escape the dissatisfaction of American life, they more often speak in terms of moving towards a country with specific qualities that they seek. They want what their home country does not offer.

6.3 Obstacles to Migration

When I inquired about why they might not immigrate, I asked my interviewees about both personal reasons and practical obstacles. Allison, Elizabeth, and Joan were all concerned about timing for their children. Elizabeth expressed an urgency to migrate before her children got any older, and Allison and Joan were both questioning if this was the best time for their teenagers to relocate. Kara stated that she had no personal reasons for not migrating, her only obstacles were legal and financial. She said that she believed she would see her family more if she lived in Ireland because they would be more motivated to visit her there.

The top obstacle to migration for my interviewees was the immigration requirement of securing an employment contract ahead of migration, followed by financial constraints. Interviewees stated that they simply did not qualify to immigrate according to current policies. In listing their other major obstacles, the interviewees returned to the employment issue—having non-transferable job skills, not speaking a foreign language (especially when required by potential employers)—and also expressed concern over having adult dependents that wouldn’t qualify to immigrate with them.

It’s really hard to immigrate anywhere as an American. It’s so hard. Because you have to get a job, and we speak English, and English only, most of the time... (Denise) A couple of interviewees also stated that accessing information on immigration requirements was prohibitively difficult.

On a scale of 1-10 (1-staying, 10-migrating), Allison, Kara, Elizabeth and Joan felt that their likelihood of immigrating was somewhere around a 4 because they just don’t see a way around the barriers to immigration. In the coming year Allison will finally be qualified to migrate to Canada after 14 years of working towards eligibility, however now that her kids are older it complicates things for her family. If she were eligible to immigrate to Canada in 2007 when she first wanted to, her kids would have been at great ages to migrate (2-9 years old), but now with teenagers and adult dependent children it is much more difficult. She thinks that now she should probably wait another five years till her kids are settled.

Bridget said her family’s likelihood of migrating is very high (8-9) and they would like to go in the next year (they would like their daughter to start in a foreign school as soon as

possible), but they too don’t see a viable path to making it happen. Denise was applying for jobs abroad when she landed her current position at home. Because she has improved her work situation, she feels that her likelihood has gone down from 7-8 to 5, but she still has the same motivations to emigrate and continues to look for potential jobs in Sweden. Elizabeth said that they will become even more determined to migrate if their kids can’t return to school this year (due to the Covid-19 pandemic), though they don’t know how to overcome strict immigration regulations.

Kara feels that there is a very low possibility of her being able to migrate, she feels that work or student immigration are unlikely options for her, and that the easiest route for her is marriage, though she’d rather not have to base her life on that. She also spoke about how she believes immigration regulations negatively impact the world.

So by having these tight laws and restrictions I can understand how it helps the

country financially, but it stops as a people from us caring about other people, because we don’t understand the situations they’ve lived in, we don’t have understanding of it, any comprehension at all… and that’s how you end up with people in America being 100% sure they live in the greatest country on Earth and having no interest in any other one’s problems, so when you hear about like, “people are dying in Syria.” They’re like, “yeah, it’s not my country. I’m not concerned about other people.” Whereas if you had the ability to go and be with other cultures easier, if you had easier access to that, I feel like everyone would do so much better. Our children would be better. We would be better because we could care more, we could understand, we’d be part of another culture, part of another system. (Kara)

My interview with Kara also called into question the assumed unfettered travel mobility of those that do possess an American passport. It is generally assumed that American passport holders are automatically granted a 90 day tourist visa in Europe. Upon arrival in Ireland for a holiday where Kara and her sister planned to bike around the country, they were initially detained by immigration for not having enough money in the bank, and when they were

finally allowed into the country, they were ordered to leave Ireland within one week. If they did not abide by the one week restriction they were threatened with having any future entry into the EU jeopardized. While they were eventually granted entry into Ireland after a friend with a substantial bank account balance stepped forward to act as a guarantor for them, they by no means experienced the type of freedom of movement that Americans are assumed to have. They had to change their travel plans and depart much earlier than intended, and had they not had someone willing and able to help them out of their situation, they would have been sent back to the United States without ever officially entering Ireland.

While it is unquestionable that Americans have greater mobility than citizens of Global South countries, it is not necessarily the unrestrained mobility that they are generally presumed to have. Though US citizens do have the advantage of being able to travel without having to work at obtaining travel visas, and while visa restrictions have been shown to have “a statistical impact on migration flows” (Carling & Schewel 2018: 955), the legal ability to travel freely does not automatically translate into the capability to migrate. The acquisition of travel visas in the immigration process is more closely related to irregular migration and overstaying visas than it is to legal immigration (Carling 2002: 30-32). While Global North citizens do overstay travel visas, and do participate in irregular migration, this is not an immigration path that the families in this study would consider taking.

In his study on migration aspiration and ability in Cape Verde, Carling noted that the greatest obstacle to migration “from a poor country to a wealthy country” was immigration policy, and not the financial costs of migration which could be overcome in various ways (2002: 26). Immigration policy restrictions do not exclusively apply to aspiring immigrants from

developing nations, they can be restrictive to citizens of all nations that do not meet the specific criteria that would make them “desirable” immigrants.

6.4 Voluntary vs. Involuntary Immobility

It is easy to quantify mobility and immobility when studying “revealed ability” (those that have already migrated), it is much more difficult to discern a potential ability to migrate

(Carling & Schewel 2018: 955). When it comes to assessing migration capability, Carling considered both regular and irregular migration as possible paths for aspiring migrants (2002). In this study, however, irregular migration is not something that any of the interviewees considered a possibility. Therefore, in assessing migration capability, I only examined legal paths to migration.

Though it had been part of the vetting process for this study, during the interviews I inquired again about the interviewees’ potential to migrate in terms of any possible access to a second passport. Every interviewee was born in the US with family that had been there for too many generations to qualify for any sort of dual citizenship. Denise was envious of people that have married into a second passport option. Despite the obstacles to immigration, she feels that qualifying for international migration is easier than finding a spouse. In the case of all of my interviewees, one of the top two paths to migration for American citizens—moving because of a foreign born partner—is presently not an option. The other major path for American emigration is an employment contract.

In an effort to explore the perceived barriers to immigration where a work contract in the destination country is often the only viable path to migration, I asked the interviewees if they were legally allowed to do so, would they immigrate without pre-arranging a job beforehand (Carling & Schewel refer to this type of hypothetical question as “conditional willingness to migrate” (2018: 948)). With the exception of Allison, all of the interviewees responded that they would do so. Allison said that she would not because she doesn’t have the finances to support herself without a job.

I have this impression that people outside the United States and Canada think that Americans are all wealthy. But the reality is, everybody that I know, with the

exception of maybe my sister and her husband, literally live paycheck to paycheck. So I don’t have $50,000 sitting in a bank account that I can use to float me for a year while I get things settled in another country. (Allison)

Everyone that responded “yes” felt that it would be easier to get a job if they were already living in their destination country. Elizabeth qualified her “yes”, saying that it would make it

easier and increase her family’s potential to emigrate, but it would not guarantee that they would emigrate because they would still have to find a way to support themselves.

Allison, Bridget, Kara, and Elizabeth all meet the criteria of involuntary immobility with job skills that are neither highly coveted in the international job market (where a new immigrant has to be deemed more qualified than a citizen or permanent resident), nor can be transferable without adequate foreign language ability—further increasing the difficulty in being

permitted to migrate. Student migration isn’t an option for most interviewees in this study as it requires an amount of savings that they do not have.

Denise has applied for jobs abroad that she was qualified for, but while doing so she acquired better employment in the US which made these positions with drastic pay cuts (and

considered low salary jobs in the destination country) less attractive despite her desire to emigrate. Though she is quite willing to take a pay cut in order to migrate, and is willing to make some sacrifices from her current standard of living, there is only so much that she is willing to sacrifice in order to migrate. It is important that she is still able to provide her son with a quality of education that is on par with what they’re used to, and that they are both still able to afford the activities that they enjoy.

The overwhelming factors right now that I’m sort of trying to work through are housing and how much money is enough money to live on. If you were a 20 year old, or a 30 year old, big deal, you figure it out, but we have kids. You don’t want to go somewhere and make your situation worse. (Denise)

While she still pursues job leads abroad, family obligations combined with her improved work situation in the US have kept her from migrating thus far.

Of all of the interviewees, Joan is the one that most challenges the current idea of what makes someone involuntarily immobile. In Carling’s aspiration/ability model, “those who do not migrate fall into two categories: involuntary non-migrants, who have aspirations to migrate but lack the ability, and voluntary non-migrants, who stay because of a belief that

non-migration is preferable to migration” (Carling & Schewel 2018: 946). Joan believes migration is preferable to non-migration, however despite appearing to have the financial and