Smartphones in Media

The New York Times: Representation of the smartphone

and the paper’s potential for normative influence

of smartphone behavior

Hanna Meyer zu Hörste

One-year Master Thesis, 15 Credits

Media and Communication Studies

Malmö Högskola, Spring 2017

Supervisor: Pille Pruulmann-Vengerfeldt

Abstract

This thesis sets out to investigate the representation of smartphones by one of the biggest English daily newspapers of the world – the New York Times – and further sheds light on the potential influence the newspaper has on the norms of smartphone behavior. The research is conducted in two parts. For the first research question through a quantitative and the second research question a qualitative content analysis of New York Times articles about smartphones from the years 2007 and 2016. For the content analysis as well as the analysis of the results three different theoretical frameworks are applied: Stuart Hall’s (1997b) representation theory, McGuire’s (2001) media effect factors and social norms theory, mainly according to Cristina Bicchieri (2017). Since assumptions on the outcome of research question one exist on the grounds of previous research conducted in the field, two hypotheses were formed:

H1 – In 2007 the coverage of smartphones will be mainly positive and focus on technological aspects.

H2 – In 2016 the coverage will be more critical about the consequences of the pervasion and influence of the smartphone in society.

The main findings of the thesis are, for research question one, a validation of the hypotheses through the quantitative content analysis and application of the representation theory through which a distinction in the representation of the smartphones denotation and connotation could be made. And for research question two, that the strongest potential of influence on norms of smartphone behavior lies in conveying and updating and thus sometimes changing of empirical and normative expectations together with further intertwined factors.

Keywords

Smartphone, New York Times, social norms, representation, media effect factors,Table of Contents

1 INTRODUCTION ... 5 2 CONTEXT ... 7 2.1 Smartphone ... 7 2.2 New York Times ... 10 3 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ... 10 3.1 Stuart Hall’s theory of representation ... 11 3.1.1 The constructionist approach ... 12 3.1.2 Saussure’s concepts of linguistics ... 13 3.1.3 Semiotic approach ... 13 3.2 Media effect factors of McGuire ... 15 3.3 Theories of social norms ... 16 3.3.1 Social norms in social sciences ... 17 3.3.2 Theory of norms according to Bicchieri ... 18 4 LITERATURE REVIEW OF PREVIOUS RESEARCH ... 27 4.1 Smartphone in scientific research ... 28 4.1.1 Ubiquity of the smartphone ... 28 4.1.2 Benefits of smartphone use ... 28 4.1.3 Negative effects of smartphone use ... 29 4.2 Examples of applied social norms theory ... 30 4.3 Media influence ... 31 5 DATA AND METHODOLOGY ... 31 5.1 Data ... 32 5.2 Methodology ... 35 5.3 Quality and Ethics ... 36 5.3.1 Quality ... 36 5.3.2 Ethics ... 376 RESEARCH RESULTS AND ANALYSIS ... 37 6.1 Research questions I ... 37 6.1.1 Results ... 37 6.1.2 Analysis ... 46 6.2. Research question II ... 49 7 DISCUSSION ... 59 7.1 Societal Implications ... 59 7.2 Limitations and further research ... 61 8 CONCLUSION ... 62 REFERENCES ... 65 APPENDIX ... 74

1 Introduction

A life without a smartphone seems hard to imagine anymore – at least for the so-called Millennials1 in developed countries. No other technology has shaped social

life so extensively in the last 10 years. 1.5 billion smartphones were sold worldwide last year (Statista, 2016). The penetration rates are constantly rising and the saturation levels are almost reached in many countries if they aren’t already. In 2015 e.g. ownership rates in South Korea were reported to be at 88% (Poushter, 2016). In the USA the smartphone ownership more than doubled from 35% in 2011 to 77% in 2016 (Street et al., 2017). But how exactly does the now ubiquitous (Rainie and Zickuhr, 2015) smartphone influence our society? This question is not only of academic- but also of personal nature, since a change of habits in myself and my surrounding led me to conduct further research. In a previous work in this master’s program I started to study the use of smartphones during face-to-face conversations (Meyer zu Hörste, 2017), which I will use as a background for this thesis.

During my research I came across many articles that critically question effects of intensive smartphone use. This spiked my interest in the media’s representation of the mobile device and their potential influence on norms around smartphone behavior. To narrow down the field of research I chose to focus on the USA, since it is a large country that adopts new technologies fast and early, and is the home of the iPhone and Android operating system. The New York Times (NYT) is one of the leading American newspapers with not only a large circulation both off and online, but a good reputation worldwide and hence is a valid source for a media content analysis (Wikipedia, 2017d). Thus my aim of this thesis is to explore the representation of smartphones by the NYT (RQ1) and the potential influence the newspaper has on the norms of smartphone behavior (RQ2).

For the content analysis I chose to examine smartphone related NYT articles of the years of 2007 and 2016. Two years are analyzed to be able to compare differences in times and observe changes. 2007 was picked due to being defined as the starting point of the smartphone revolution (Friedman, 2016), and 2016 was chosen as it was the last full calendar year for study. The analysis will be conducted

in two parts. For each research question I have a different approach: The first research question (RQ1) regarding the smartphone’s representation in the NYT, I will investigate with the help of a quantitative analysis. For the second research question (RQ2) I am going to perform a qualitative analysis to examine the potential impact of the NYT on norms of smartphone behavior.

Through my previous work I have two different assumptions concerning the representation of smartphones (RQ1) in the chosen two years. Due to the fact that it was still a relatively new technology and exciting topic in 2007, I suspect the coverage to be mainly positive and focused on new devices and features. Whereas in 2016 the smartphone has already developed so far that it is not easy for the tech companies to enthuse people about new models and features. Nevertheless the influence of the medium in society reached so far that critical voices will probably dominate the coverage. Consequently I have two hypotheses that I will investigate while I am exploring how smartphones are represented (RQ1):

H1 – In 2007 the coverage of smartphones will be mainly positive and focus on technological aspects.

H2 – In 2016 the coverage will be more critical about the consequences of the pervasion and influence of the smartphone in society.

The second research question will be analyzed explorative and therefore without hypothesis.

In the next chapter I will describe context of the smartphone by looking at development and important milestones of the device and further give background information on the NYT. Then I will walk you through different aspects of representation theory, McGuire’s media effect factors and theories of social norms. This framework will help me to unravel my research questions by providing a foundation for the content analysis. This will be followed by an overview of smartphone related research and a description of the procedure of my quantitative and qualitative analysis of the NYT articles. Subsequently I will present and analyze my research results through the lens of representation and social norms theory, media effect factors and previous research and discuss the meaning of my findings. This thesis then concludes with a summary of my work.

2 Context

2.1 SmartphoneThe word smartphone originates from the words smart and phone and refers to a telephone, enhanced with computer technology (Oxford Dictionaries | English). Today it is mostly defined as a mobile phone with Internet access and an operating system (OS) that can run applications (apps) and thereby functions like a mobile computer (Merriam-Webster, Oxford Dictionaries | English, Wikipedia, 2017c). Figure 01: Simon Personal Communicator next to an iPhone 4 (Bloomberg.com, 2012) The first phone that could have been called smartphone is the Simon Personal Communicator. IBM presented a prototype 1992 at a computer industry trade show and together with BellSouth Cellular started selling an improved version in 1994. The phone already had a touch screen, could access the Internet and featured software apps. (Savage, 1995; Bloomberg.com, 2012; Cellan-Jones, 2014; Wikipedia, 2017c) In 1996 Nokia released the Nokia 9000, which was a combination of mobile phone and at the time popular personal digital assistant (PDA). Further early smartphones were the pdQ Smartphone from Qualcomm (release 1999), the Ericsson R380 (release 2000), the Kyocera 6035 by Palm Inc. (release 2001), and the Treo 180 by Handspring (release 2002). With the releases of the Danger Hiptop also called the T-Mobile Sidekick, the first BlackBerry smartphones, further Palm

Treo phones2 and smartphones based on Microsoft’s Windows Mobile in the early

2000s, the smart devices started to gain popularity in the USA, at least among business users. With its launch of the Nseries in 2005, Nokia started to focus on multimedia and entertainment features and thereby turned to the general consumer market. (Wikipedia, 2017c) But it was the release of the Apple iPhone, the announcement of the Android operating system by Google and the Open Handset Alliance in 2007 that brought the change and the smartphone to the consumer.

The first iPhone has often been called revolutionary because it changed the way people used their smartphones. It was a combination of the popular iPod with a smartphone, and also the first to have a big touchscreen. This screen was used directly with fingers instead of a stylus and could be operated with intuitive multi-touch gestures and the virtual keyboard. Apple also simplified many processes and focused on an appealing design. (Markoff, 2007a; Pogue, 2007; Wikipedia, 2017a)

Android on the other hand is a free open-source project, created by Andy Rubin, acquired by Google and developed under the lead of Google by the Open Handset Alliance3. It was first used in an HTC phone4 released in 2008. (McCarty, 2011;

Mallinson, 2015; Wikipedia, 2017b) Android now dominates the smartphone world with a OS market share worldwide of 87% in the third quarter of 2016 (www.idc.com).

Further milestones in the smartphone history are the first time they outsold personal computers (PC’s) with sales of 100.9 million smartphones versus 92.1 million computers, which according to the International Data Corporation (IDC) took place in the fourth quarter of 2010 (GSMArena.com). It shows the growing importance and functionality of the smart handset and its ability to substitute a PC. In 2013 the annual sales of smartphones (54%) exceeded sales of regular mobile phones worldwide. This number shows that smartphone adoption has also reached less developed areas of the world; sales in Latin America, Middle East, Africa, Asia/Pacific and Eastern Europe grew by more than 50 percent in the fourth quarter of 2013 (gartner.com). Another number that is constantly rising since the introduction of smartphones is the time spent with the device. From 2013 to 2016

2 Palm Inc. bought Handspring in 2003

3 founding members amongst others HTC, Samsung Electronics, Motorola and T-Mobile 4 HTC Dream

consumption has nearly doubled in the USA (Lella, 2017), from 2,6 hours to 5 hours a day by an average consumer (see figure 02). As figure 03 shows 50% of the time is spent in social, messaging, media and entertainment apps. (Khalaf and Kesiraju, 2017) Further it indicates people relying more and more on their phone for daily tasks and habits, which conforms to my observations. Figure 02: US Daily Mobile Time Spent (Khalaf and Kesiraju, 2017)

2.2 New York Times

The New York Times, founded in 1851, is one of the biggest American daily newspapers. It had the second largest circulation5 in the USA in 2013 is among the

top 20 largest circulated newspapers worldwide. (Wikipedia, 2017d) Meanwhile the NYT has its focus on online publishing and reached over one million digital only subscribers in mid 2015, which is partly due to its international spread (Sullivan, 2015). It is not owned by a media network but by The New York Times Company and has been awarded 122 Pulitzer Prizes (Pulitzer Prizes, 2017). The NYT readers tend to be younger than average (32% under 30), have higher education (56% college graduates) and good income (only 26% have a family income of less than 30.000$). And the majority describe themselves as liberal (36%) or moderate (35%) (22% conservative) (Street et al., 2012).

3 Theoretical framework

To investigate the representation of the smartphone and the potential influence of the NYT on norms of smartphone behavior, I want to work with three different theoretical approaches, which I explain in the following chapter. I am starting off with Stuart Hall’s theory of representation, including its roots in Saussure’s linguistics and the semiotic approach. According to Oulette’s introduction (2013) to Hall’s Work of Representation he „presents a critical toolbox for analyzing the role of media in the social construction of reality” (p.167), so it will help me to look into the creation and change of meanings and therefore help me to investigate RQ1. Further I will consult McGuire’s media effect factors, which I will use as a base for my coding categories, to explore generally how and under which conditions the NYT can have an impact and how certain articles can influence readers. Subsequently I will turn to theories around social norms that explain how norms are defined, emerge and change, to analyze how NYT articles can have an affect on norms and unravel RQ2.

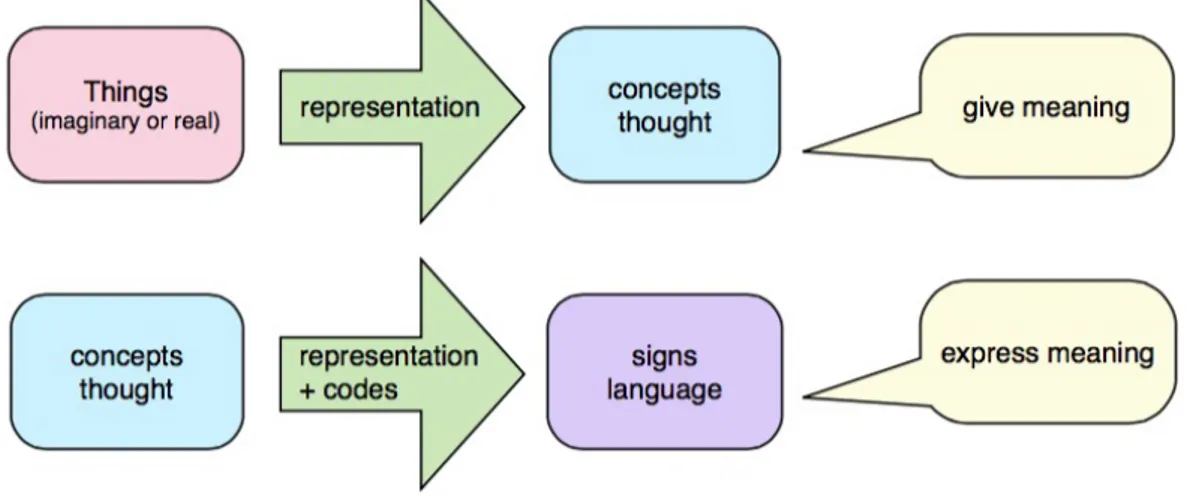

3.1 Stuart Hall’s theory of representation

According to Hall (1997a), representation is a central concept to produce culture, which he describes as “’shared values’ of a group or of society” (p.1). He (1997b, p.172) defines representation as the production of meaning, of the concepts in our minds through language6. To create meaning two systems of representations

are involved: mental representations and language.

Mental representations, also called conceptual system or map, means to classify, organize, arrange different concepts and establish complex relationships between them to give meaning to the ideas, of real or imaginary things in our heads (Hall, 1997b, p.172f.). Language is needed to communicate with other people and express meanings. It enables us to translate our thoughts into signs and exchange them with people that share the same signs and the same way of interpreting them. Signs are any sounds, words, images, objects or gestures that organized with other signs into a system, are capable of carrying and expressing meanings. (Hall, 1997b, p.173f.)

The meaning of a sign is constructed by the code, which defines the relation between the conceptual system and the language system. The possibility to translate between concepts and signs and thus to express meaning is given through a system of codes, a set of conventions. To interpret signs the same way, they must be shared. In various cultures the social or linguistic conventions can be different and can change over time. “Even when the actual words remain stable, their connotations shift or they acquire a different nuance. (Hall, 1997b, p.175f.)”

Figure 4: Illustration of representation process according to Hall (1997b), my own visualization

A simplified process of representation can be described as follows: Things are represented by concepts to give meaning and concepts are represented by language with the help of codes, to express meanings (see figure 4) (Hall, 1997b, p.173f.). 3.1.1 The constructionist approach In his work Hall mentions three different approaches that try to answer the question where meaning comes from and how representation of meaning works; the reflective, the intentional and the constructionist approach.

Within the reflective approach, language functions like a mirror to reflect or imitate the existing meaning. A limitation to this approach is, that not all things have an already existing meaning that can be reflected. Also, for the exchange of meanings it is important to have signs and codes for things, because one cannot communicate with the actual things. (Hall, 1997b, p.176) Within the intentional approach, individuals themselves give meaning to words, and the word means what one thinks it should mean. But if every individual would have their own meanings to the things and there would be no shared codes or conventions, than meanings could also never be exchanged. (Hall, 1997b, p.177)

Due to limitations of the former two and my constructionist approach in general to this paper, I will focus on the constructionist approach. It differentiates the material world where people and things exist, from symbolic processes. Things do not have meanings by themselves. And there is no natural relationship between a sign and its concept. Meanings are constructed through the correlation of sign and concept by a code. Hence a sign can function and convey meaning because it symbolizes or represents a concept. The meaning to it is fixed by the linguistic code and enables people to communicate about concepts. (Hall, 1997b, p.177f.)

Hall (1997b) further mentions two models of the constructionist approach: the semiotic approach and the discursive approach. Due to the greater relevance for this thesis I will only describe the semiotic approach in the following and since it grounds in Saussure’s concept of linguistics start with a brief description of the same.

3.1.2 Saussure’s concepts of linguistics

Similar to the constructionist view, Saussure stated (Culler 1976, p.19, ref. in Hall, 1997b, p.179) that the production of meaning depends on language, which is a ‘system of signs’. Words, sounds, images etc. need to be part of a system of conventions to express ideas and only then function as signs. Signs consist of two features: the form7 called the signifier and the idea or concept called the signified.

The relation between the signifier and the signified is determined by cultural and linguistic codes and provides representation. The signifier as well as the signified carry meaning, but they only exist in combination as a sign. (Hall, 1997b, p.179) Figure 5: Illustration of sign according to Saussure (ref. in Hall, 1997b, p.179), my own visualization The meaning of a sign is not permanently fixed, but is “produced within history and culture” (Hall, 1997b, p.180) and can change constantly. Because a sign never has just one true meaning, communication is always subject to interpretation. And thus the meaning a receiver understands is never completely as the sender intended it to be. Other or hidden meanings are included in the process of coding and encoding. (Hall, 1997b, p.180f.) Interpretation becomes a central aspect in communication and so “the reader is as important as the writer in the production of meaning” (Hall, 1997b, p.181).

Saussure further described language as a “social phenomenon” and separated the “social part of language (langue) from the individual act of communication (parole)” (Hall, 1997b, p.181) to study it. 3.1.3 Semiotic approach The semiotic approach largely builds upon the linguistic concepts of Saussure, but tries to explain how representation works on a broader cultural level. 7 actual word, sound, image etc.

It argues that, like language, culture makes use of signs because cultural objects convey meaning and cultural practices depend on meaning. Therefore culture should be analyzable through similar concepts like Saussure’s. (Hall, 1997b, p.182) With this wider approach an object can also be a signifier that correlates through a code with a certain concept (the signifieds), thus become a sign with a meaning. In contrast to the linguistic concept there are two levels of meanings in the semiotic approach. First, the descriptive level of denotation, where most people would agree on the same meaning. And the second level of connotation, where signs are interpreted on a broader level with a wider different kind of code, regarding to one’s general beliefs and the value systems of society. On this second level the completed meaning of the first level, functions as the signifier. It is linked to a second set of signifieds and discovers a further more elaborate meaning.

For my analysis this means that, a reader can only read and comprehend news articles if he speaks the same language as the author and they also have a shared code, as Hall calls it, “maps of meaning” (1997b, p.179). Because these maps are not fixed and completely clear, the reader has an important role to the production of meaning, because he has to interpret what the author wrote and figure out the meaning.

As mentioned, codes and meanings can change, if not in the level of denotation than certainly in the level of connotation. Codes are the result of social conventions and are learned and unconsciously internalized while people take part in social and cultural life, therefore media is part of this change and influences codes (intentionally or unintentionally) (Chung and Rimal, 2016, p.18). I will take a closer look into social conventions, norms and codes of social life in the third theoretical approach of theories of social norms.

With the theory of representation and the semiotic approach I want to unravel how the smartphone is represented by the NYT, how they give and/or express meaning and how this representation has changed from 2007 to 2016. But it will also help me with the second research question on norms.

To find out more how media can have an impact and influence the reader and social conventions I chose to further look at certain factors that have an effect on readers.

3.2 Media effect factors of McGuire

McGuire (2001, p.23), a researcher of media effect and persuasion named, based on Lasswell’s levels of communication, five classes of persuasive communication’s input variables that take part in the production of a media effect (Dillard and Shen, 2012): source (who), message (says what), channel (via which media), audience (to whom), and destination (regarding what). These five factors are a good basis to understand how media can influence its audience. I will use them to build my categories for the content analysis and as underlying framework to examine the impact of the NYT in general and with specific articles.

3.2.1 Source

Three important factors for impact are credibility (the source’s perceived expertise and trustworthiness), attractiveness (likeableness through familiarity and similarity) and power (the source’s control over rewards and punishments, authoritativeness). Sources are for example more likely to have an influence, if the reader perceives them as honest, reliable or more similar to themselves (McGuire, 2001, p.24). For my coding categories the source will consist of author and voice of article.

3.2.2 Message

Structure and type of arguments, type of appeals, message style (clarity, forcefulness, literalness, figurative language, humor), and quantitative aspects (length, repetition) make an impact on the communication. Next to the salient topic a message usually also affects unmentioned but related issues (structure of arguments). And readers have needs that a message can appeal to, such as the need for stimulation or for felt competence (type of appeals). (McGuire, 1989, p.46, 2001, p.25ff.) A message is more effective if it is repeated, consistent, without alternatives and the receiver is not involved in the topic. Factors like style (personalization), appeal (emotional/rational), order and balance of arguments also take a role in it (McQuail, 2010, p.469). Since I am examining newspaper articles this will be the most important and biggest main category.

3.2.3 Channel

Different media, but also different intrinsic channels of a medium (McQuail, 2010, p.469) have different ways and intensities of influencing. Not only the medium but the use situation, environment and context are additional factors of impact. McGuire for example claims that people are more likely to be influenced by a message when they are alone rather than with other people, and when they are in a pleasant atmosphere or mood. The meaning of a message might also be reduced by the amount of messages received. (McGuire, 2001, p.30-36) In this category I will look at the section of the NYT the article was published.

3.2.4 Audience

The differences in the audience (demographics) and the people’s individual differences in personality, abilities, interest, lifestyle, motivation, involvement and level of prior knowledge are all influencing measures (McGuire, 2001, p.31; McQuail, 2010, p.469). Furthermore effects differ if messages are aimed at a wider audience or directed towards a sub group, which can be addressed more specifically (McGuire, 2001, p.31). The corresponding coding category is addressed audience. 3.2.5 Destination or target variables

Impact is affected by variables concerning attitudes, actions and behavior of the target at which the message is aimed. (McGuire, 1989, p.47f.) There is a correlation between attitude, belief and behavior. If a message changes one of the named it is likely that there will be a similar change in the other two as well (McGuire, 2001, p.34). With this section I am focusing with the coding on the context of the article8.

3.3 Theories of social norms

To look further into the relation of attitude, belief, social conventions, norms and behavior and understand how norms evolve and change I will make use of theories of social norms. Social norms are a much-researched phenomenon and concern multiple disciplines since they belong to the study of human interactions. Every discipline has its own focus, definition and approach; subsequently there is no general consensus on a theory of social norms. According to Chung and Rimal

(2016) a common denominator of the different disciplines regarding the definition of norms could be described as “collective awareness about the preferred, appropriate behaviors among a certain group of people” (p.3). Within the different disciplines researching norms, there can mainly be found two different approaches on norms. One is from the social sciences and focuses mainly on the functions of norms and how they motivate and restrain people to act. Within this approach norms are conceived as exogenous variables. (Bicchieri and Muldoon, 2014 [2011]) The other approach is from the studies of philosophy and in contrast sees norms as “an endogenous product of individual’s interactions” (Bicchieri and Muldoon, 2014 [2011]), which is supported by expectations about how other’s behave and await individuals to behave in certain situations (Chung and Rimal, 2016, p.5). Below I will give a short overview of the approach of the social sciences and then continue with a more detailed description of the norms theory of Cristina Bicchieri as an example of the philosopher’s approach on norms, which I chose to use for my analysis. 3.3.1 Social norms in social sciences

Scholars in social sciences, especially in psychology, communication and public health focus their study of social norms on the role they play in shaping human behavior. It is based on the thought that an individual’s behavior and attitude is influenced by the behavior and attitude of members of their social surroundings (Chung and Rimal, 2016, p.3). “Through interpersonal discussions, direct observations, and vicarious interactions through the media, people learn about and negotiate norms of conduct. (Chung and Rimal, 2016, p.3)”

Different norms are distinguished in the various works of social scientists. For clarification, subsequently I enclosed the most commonly named definitions of norms from social science research:

Collective norms – operate on the societal level and refer to “prevailing codes of conduct that either prescribe or proscribe behaviors that members of a group can enact” (Lapinski and Rimal, 2005, p.129) This code of conduct can be related to the code from the representation theory or the semiotic approach. The code of conduct

is basically a “shared conceptual map” (Hall, 1997b, p.173) and serves the understanding and coordination of cohabitation within a group or society.

Perceived norms – operate on the individual level, and refer to “individuals’ perceptions about others’ behavior and attitude” (Chung and Rimal, 2016, p.3) and what others’ would want them to do or behave. Injunctive norms – refer to “peoples’ belief about what ought to be done” (Lapinski and Rimal, 2005, p.130) Descriptive norms – refer to “beliefs about what is actually done by most others in one’s social group“ (Lapinski and Rimal, 2005, p.130) Subjective norms – refer to “the perceived social pressure to enact a behavior from important others in one’s social environment“ (Chung and Rimal, 2016, p.7)

Different theoretical frameworks have evolved through the research on social norms, including social norms theory, focus theory of normative conduct, norm accessibility vs. attitude accessibility, the prototype willingness model, theory of planned behavior and theory of normative social behavior.

These theories are used to practice and research interventions against negative behavior or to encourage positive behavior. Examples are recycling, drinking, cigarette smoking, safe driving, drug use, to prevent sexual assault, improve academic climate and reduce prejudicial behavior. I will elaborate further on interventions in the literature review section.

3.3.2 Theory of norms according to Bicchieri

The main differences between the social scientists’ and the philosophers’ approach is that the social sciences are often missing a clear distinction between social norms, conventions and descriptive norms (Bicchieri and Muldoon, 2014 [2011]). Bicchieri (2017) also criticizes, that social sciences’ understanding of descriptive norm includes customs or fashions likewise, whereas according to her a custom is a “consequence of independently motivated actions, that happen to be similar to each other“ and a „fashion causes an action that is consistent with it via the presence of

expectations and the desire to imitate the trendy“ (p. 18). She argues, that the definition is “too vague and of little practical use” (p.18) Bicchieri and other philosophers differentiate between social norms, conventions and descriptive norms with the help of expectations (Bicchieri and Muldoon, 2014 [2011]). Through measuring if and how much expectation matter and influence behavior different collective behaviors can be identified (Bicchieri, 2017, p.ix). Hence Bicchieri provides a good framework to distinguish and explain individual and collective behavior and furthermore includes the role of media in it. These are the reasons I chose to work with her theory and use it to understand the structure, emergence and change of social practices and find an answer to my second research question. In what follows I will outline Bicchieri’s diagnostic process of identifying collective behavior and definitions of different kinds of behavior.

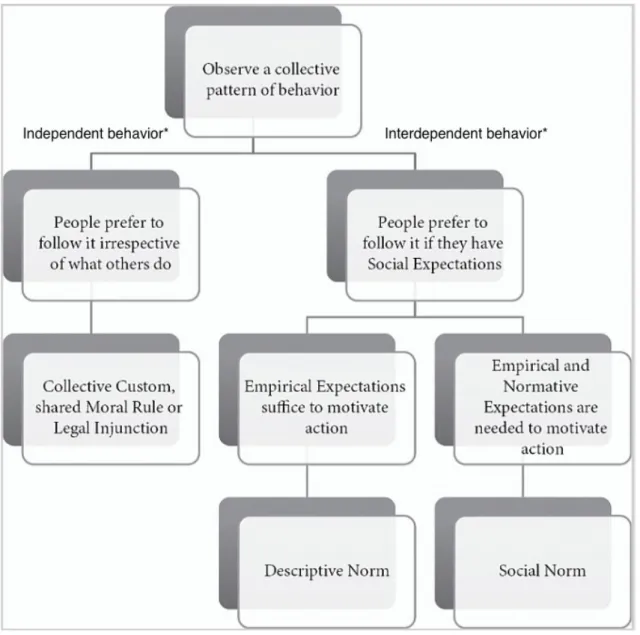

There are various factors that determine the nature of collective behavior (Bicchieri 2017, p.41). To identify them Bicchieri divides them into two kinds: independent and interdependent behavior. Whereas independent behavior does not depend on other people, interdependent behavior relies on others, especially one’s reference network (the range of people an individual cares about when making decisions (Bicchieri, 2017, p. 14)). According to Bicchieri studies show that behavior is more affected by what individuals believe others approve of and not what they believe themselves. “Interdependence not independence, rules social life. (Bicchieri, 2017, p.10)” Therefore attitudes, an evaluative view on behavior, people or objects (Bicchieri, 2017, p.8), are only weakly correlated with behavior, if at all (Wicker 1969, ref in Bicchieri, 2017,p.11). Nonetheless, since independent behavior is important to identify collective action as well, I will continue with it and then proceed to interdependent behavior.

3.3.2.1 Independent behavior

Independent behavior is determined by economic or natural reasons. (Bicchieri, 2017, p.2) Customs, habits, moral or religious codes and legal injunction may generate uniform behavior, but they are all independent of expectations of other people’s actions and behavior. They fulfill perceived individual needs or are obeyed because of beliefs or fear of punishment. (Bicchieri, 2017, p.59)

Expectations and beliefs

Behavior is grounded in expectations, which are beliefs about what is going to or should happen. Beliefs can be either factual or normative. (Bicchieri, 2017, p.11) Factual beliefs are beliefs about certain circumstances or consequences of actions (Bicchieri, 2017, p.20); they can be true or false. Personal normative beliefs on the other hand are beliefs about what people ought to do. They can be prudential or driven by moral values like honor, fairness or justice and express if somebody approves or disapproves of certain behaviors. (Bicchieri, 2017, p. 125ff.) (see figure 06) Figure 06: Classification of Normative/Non-Normative and Social/Non-Social Beliefs (Bicchieri, 2017, p.12) Custom A custom is a pattern of behavior, which meets an individual’s needs and thus she or he prefers to conform to it, without regard to social expectations. Hence a “custom is a consequence of independently motivated actions that happen to be similar to each other“ (Bicchieri, 2017, p.18). Customs may change when an alternative, a better way to satisfy the needs appears, the conditions that produce the needs disappear, or new preferences are created. Even though customs are independent behavior, when they are carried out in a group (collective custom), they produce certain interdependencies and thus might require collective action to change them. (Bicchieri, 2017, p.15f.) Consequently, observed from the outside, practices of customs and descriptive norms (see below) may look identical, the difference between them is the reasons why people follow them (Bicchieri, 2017, p.20) (see figure 07).

Figure 07: Diagnostic process of identifying collective behaviors.

Source: C. Bicchieri, Social Norms, Social Change. Penn-UNICEF Lecture, July 2012 ref. in Bicchieri 2017, p.41) *added by me

3.3.2.2 Interdependent behavior

Interdependent behavior such as conventions (everyone profits from doing the same thing (Bicchieri, 2017, p.59)) and social norms rely on other people’s action and opinions, they rely on social expectations (Bicchieri, 2017, p.2f.).

Social expectations

The expectations somebody has, about other people’s behavior and beliefs, which influence their own behavior (Bicchieri, 2017, p.11). There are two types of social expectations: empirical expectations and normative expectations (Bicchieri, 2017, p.14).

Empirical expectations

The expectations somebody has, how other people will behave and act in specific situations; what is common, normal and generally performed. These expectations are formed with the help of observations or information of behavior (from the media for example) and are assumed to continue and therefore influence one’s own decisions. (Bicchieri, 2017, p.12&95) (see figure 06)

Normative expectations

The expectations somebody has, what other people in their reference network think should or shouldn’t be done, how they ought to behave and which consequences will follow this behavior (Bicchieri, 2017, p. 97). Normative expectations involve sanctions (positive or negative) or people follow them because they consider others’ expectations to be legitimate (Bicchieri, 2017, p.59). Either way, they keep individuals “in line”. (see figure 06)

Descriptive norm

A descriptive norm is a pattern of behavior such that individuals prefer to conform to it on condition that they believe that most people in their reference network conform to it (empirical expectation). (Bicchieri, 2006, ref. in Bicchieri 2017, p.19)

Descriptive norms cause actions out of the presence of expectations and the desire to conform to a group9 (Bicchieri, 2017, p.27). Thus “they have a causal influence on

behavior” (Bicchieri, 2017, p.27). Examples are conventions, fashions or common signaling systems. Descriptive norms also play an important role regarding the influence of media. The media audience is aware that others in their reference network consume the same media and receive the same messages and act accordingly. (Bicchieri, 2017, p.20) If descriptive norms change, it means that the underlying empirical expectations of the majority of the group changed. To comply with a new norm a group member has to be convinced that nearly everybody else in the group will participate as well. (Bicchieri, 2017, p.20) (see figure 07)

Imitation

Individuals tend to copy most frequent or successful actions of other individuals that are similar with or in similar situations like them. (Bicchieri, 2017, p.18) This behavior can particularly be observed when individuals are uncertain or insecure, than “we often turn to others to gather information and obtain guidance” (informational influence) (Bicchieri, 2017, p.23). All people have a desire to be right, liked and to belong. What is right is often defined by social reality and group standards are adopted to gain social appreciation and acceptance (normative influence). With normative influence sometimes group pressure comes along, and then nonconformity will be sanctioned. (Bicchieri, 2017, p.23f.) Imitation is unilateral; the expectations only go in one direction (Bicchieri, 2017, 18ff.).

At this point, a connection could be drawn to Gerbner’s cultivation theory, which implies that people watching television adapt their beliefs according to the world presented by television, due to their acceptance of it as a true representation of the real world (McQuail, 2010, p.554).

Coordination

In contrast to imitation coordination is multilateral. Expectations of participating individuals must match (Bicchieri, 2017, 18ff.) and “stem from a desire to harmonize […] actions with those of others so that each of […] [the] individual[s] goals can be achieved” (Bicchieri, 2017, p.25f.). Social norm A social norm is a rule of behavior such that individuals prefer to conform to it on condition that they believe that (a) most people in their reference network conform to it (empirical expectation), and (b) that most people in their reference network believe they ought to conform to it (normative expectation). (Bicchieri, 2006, ref. in Bicchieri, 2017, p.35)

Social norms tell individuals how they are supposed to act, they express which behaviors are socially approved or disapproved of. In the social science approach, this would be called an injunctive norm. Bicchieri criticizes again, that the traditional definition of injunctive norm is not precise enough to distinguish it from

moral norms. (Bicchieri, 2017, p.30f.) Contrary to moral norms, social norms depend on expectations of collective compliance. (Bicchieri, 2017, p.33) Empirical and normative expectations are mandatory to maintain the norm, because self-interest is not immediate (Bicchieri, 2017, p.59). Social norms must be socially enforced with a system of sanctions (negative or positive). Otherwise people would not follow and the norm wouldn’t work. (Bicchieri, 2017, p.39) Individual compliance is determined by the sensitivity to the norm and the consequences of disobedience (Bicchieri, 2017, p.38) (see figure 07).

Through Bicchieri’s approach on norms I have a framework and definitions at hand that let me identify, clearly distinguish and explain different kinds of collective behaviors, like customs, conventions or social norms. It will help me to recognize behavior mentioned in NYT articles. The illustrations above summarize Bicchieri’s classification and diagnostic process. The charts and the belonging definitions will be used to establish categories for my qualitative content analysis, during the coding and analysis process. Additionally Bicchieri provides a tool with her framework to explore and evaluate if and how messages have the ability to influence behavior, which I will describe below.

3.3.2.3 How can norms be influenced?

Reasons for behavioral change can involve personal reasons for change10 and

reasons motivated by social expectations. Due to the fact that norms are grounded in social expectations, to influence a norm always means to influence social expectations. (Bicchieri, 2017, p.106f.) But since norms are supported by beliefs, for a norm to change, beliefs would have to change first in order to establish reasons for change of behavior. Information, observation and experience can make individuals aware of false beliefs and thus induce change, which could be followed by a change of social expectations. (Bicchieri, 2017, p.123f.) For collective behavior to change, people need to have the proof that other people will participate in the change too and then actions can take place coordinated. New empirical expectations would arise followed by the abandonment of old normative expectations and the creation of new ones, and thus the norm would change. (Bicchieri, 2017, p.119ff.) In the table

below I will present an overview of factors that can influence change and the role that could be taken in it by media. Table 01: Important factors to influence change according to Bicchieri (2017), own summary Theory Role of media Reasons / motivation / collective desire to change Without reasons and motivation, no change would occur (p.107)

Media can help to inform or show people problematic behavior and behavior of others. Awareness

Individuals may not see problems with recent behavior or do not know about possible alternatives (p.121f.). People are often not aware of their beliefs and expectations (p.128).

Present drawbacks and good alternatives. Make people aware of their and others’ beliefs and expectations. (p.129)

Beliefs (factual / personal normative)

For a change of behavior beliefs need to change first in order to give reasons and motivation. Belief change by itself is not enough motivation for behavioral change though (p.119).

Distributing new factual information or letting the audience observe reality (emotional level can often be more effective than rational level). (p.115) Testimony is a good way to influence people, either through social proof (many think it’s good or true), a trusted authority or a recognized expert (p.124f.).

(see McGuire / Source) Social expectations (empirical / normative)

Mutual expectations can help or hinder change. Expectations of what others do influences people’s behavior (p.109). People need security and the knowledge that others will change too and sanctions won’t occur (p.119). Therefore expectations change collectively if change happens (p.110).

Through the provision of information (e.g. what others are thinking and doing) and engaging people emotionally through telling stories, media can influence change. Consuming media also stimulates discussion and therefore encourages updates of expectations (p.147ff.).

Coordination of change

Because of social comparison collective norm change only occurs coordinated. With descriptive norms coordination through communication is enough but with social norms participating individuals additionally need the confirmation that others will change

Providing normative information can influence change. But since people need the reassurance that other people are acting, or will act the same way, providing empirical information about others behavior has proven to be more effective in behavior change (p.152).

too. (It is not enough to know that other group members received the message as well.) (p.108f.)

Trendsetter

People who take part in something new before other people follow; also called “early adopters” (p.49) or “first mover” (p.163). They are often attributed by a “low risk sensitivity, low risk perception, low allegiance to the standing norms, high autonomy, and high perceived self-efficacy”(p.163).

Not only individuals can be trendsetters. Groups or the media can function as trendsetters as well. They “initiate change, serve the critical role of signaling that change is indeed occurring, and help to coordinate behavioral change on a broader level” (p.162).

Scripts and Schemata

In her work Bicchieri (2017) also describes the concept of schemata and scripts. Referring to Fiske and Taylor, McClelland, Rumelhart and the PDP Research Group (2017, p.132) she states that we structure our world into schemata that are grounded in our experience and knowledge about the social and natural world; knowledge that can also be obtained by media. There are schemata for people, places, objects and events. Event schemata are called scripts (Shank and Abelson, 1977, ref. in Bicchieri, 2017, p.132) and describe specific behaviors for certain events that people can automatically engage in through the knowledge of the script (Bicchieri, 2017, p.131f.). Schemata, scripts and norms are closely connected. Based on the schemata people form expectations, and through the script they act on them and evaluate other peoples’ behavior accordingly (Bicchieri, 2017, p.131+135). This concept can be related to the representation theory and semiotic approach mentioned earlier, where schemata are called “maps of meaning” or “conceptual maps”.

The summarized table of important factors to influence change according to Bicchieri (2017) and the included role of media will be combined with the media effect factors and used to unravel the role of the NYT in regards to influence of change. Hence it will be used for the general qualitative analysis of all NYT articles as well as for the more thorough analysis of the example articles that I will be

carrying out. With the three different theoretical approaches described in this chapter I have a good and comprehensive framework for the analysis of my data and to investigate both research questions. The following literature review will also add depth to my framework and provide background on recent research concerning my topic.

4 Literature review of previous research

To the best of my knowledge, there is neither literature published about the smartphone’s representation in media nor the media’s influence on the norms around smartphones.

The best result of my inquiry is a study that researches “The construction of Symbolic Values of the Mobile Phone in the Hong Kong Chinese Print Media” (Yung, 2005). The research shows how print media represents mobile phones in Hong Kong during the years 2000 and 2001. The author suggests, that the media have contributed to an environment where the symbolic value of smartphones in society overtakes technical value. Symbolic values are constructed through a particular language style and linguistic strategies like naming practices and metaphors creating social identities for mobile phones and a social world for the technology with relationships and competition. In this case media takes part in reflecting and generating social meanings and changes perceptions of technology. (Yung, 2005, p.364f.)

On the influence of smartphones on our daily lives and society in general various research has been conducted; for example on the change of language (Ling, 2005; Segerstad, 2005; Androutsopoulos, 2011) or phone use in public and during social situations (Agger, 2011; Przybylski and Weinstein, 2013; Drago, 2015; Brown et al., 2016; Misra et al., 2016). To give a brief overview of the smartphone related research I will start by summarizing most important topics of research on smartphones to my field of study. Then I will proceed to the application of social norms theory and describe studied examples of interventions. And lastly turn to research of media influence on norms.

4.1 Smartphone in scientific research

Since its accelerated dissemination and the increasing ubiquity of it, the smartphone is a much-researched phenomenon. Many different themes have been covered, but especially in recent years researchers are focusing on its negative effects. I will start with the omnipresence, proceed to benefits and then attend to the negative attributes of the device. This chapter will be based on my work on the use of smartphones during face-to-face conversations (Meyer zu Hörste, 2017). 4.1.1 Ubiquity of the smartphone Smartphones are “media convergence devices” (Adami and Kress, 2009, p.185) that combine and replace many different digital devices. With its mobile connection to the Internet, computer-like practicability, diverse communication and staying socially connected possibilities (Fortunati, 2002), entertaining factor, source for information and functionalities of a personal assistant, there are few things left that can’t be done with the help of a smartphone. Thus they found their way into almost every part of our lives. The many uses of the multipurpose tool and the fact that people spend evermore time with it, are “always on” (Gerlich et al., 2015; Rainie and Zickuhr, 2015) and the phenomena of absent presence11 (Fortunati, 2002; Gergen,

2002) engage many researchers. 4.1.2 Benefits of smartphone use

Above I already named some of the smartphone’s purposes of use. For many people it is a great achievement to be mobile and still stay connected to their social-, work- or information-network. It has many advantages to be able to take a miniature computer-like device with Internet access with us wherever we go. People can make use of time that many would consider wasted12 (Fortunati, 2002,

p.518), people can do more than one thing at a time (Fortunati, 2002; Gergen, 2002) and shorten time to wait on answers with an increased response behavior (Forgays et al., 2014). These are all measures to, as Fortunati (2002) calls it “expand time in thickness” (p.517), to make better use of the given time and to increase social productivity (p.514). Through the smartphone the user can be almost everywhere

11 constant division of consciousness 12 waiting in line, commute, etc.

he wants to be, even in different places13 at the same time (Fortunati, 2002, p.515).

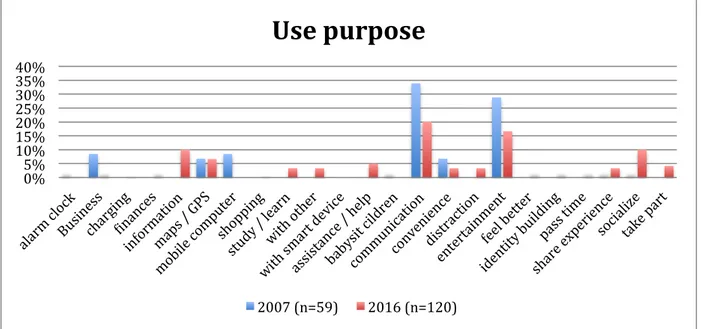

They can still contact their social network although they aren’t present and keep in touch with the outside world, which Couldry (2004) refers to as “liveness” (p.255). Being able to reach out to one’s peer group in situations of loneliness, anxiety or insecurity can have positive effects of providing or reestablishing security and stability (Fortunati, 2002, p.522f.). Further, smartphones are frequently used for convenience, simplifications, assistance with various matters, diversion, entertainment, and as control center in combination with so-called smart devices (Sarwar and Soomro, 2013; Chotpitayasunondh and Douglas, 2016). In the discussion section I will revisit some of the benefits and negative effects to discuss if the NYT presents these issues in a similar manner to the academic research.

4.1.3 Negative effects of smartphone use

With all the benefits and possibilities of this technology people become accustomed to their perpetual access and “umbilical cord” (Fortunati, 2002, p.518). Concluding from my previous work (Meyer zu Hörste, 2017) this adaption will eventually lead to a dependency. As numbers from market research (Lella, 2017) confirm smartphone usage is constantly increasing, illustrating the pervasion into everyday live and the seemingly inability of limitation (Oulasvirta et al., 2011). Subsequently this can lead to negative consequences like disturbance of others and self. Others for example can be disturbed when they are snubbed or ignored during social interactions14 (Przybylski and Weinstein, 2013; Angeluci and Huang, 2015;

Drago, 2015; Brown et al., 2016; Chotpitayasunondh and Douglas, 2016; Moser et al., 2016), are suddenly part of an intimate space of others15 (Forgays et al., 2014;

Rainie and Zickuhr, 2015) or through distracted drivers or walkers (Hassani et al., 2016). The smartphone user himself can also be greatly influenced by his smartphone habits. According to certain scholars (Fortunati, 2002; Gergen, 2002) the constant urge to communicate or use the phone in other ways and multitask leads to the omission of time for reflection and relaxation, and hence can lead to technostress or even addiction (Park, 2005; Salehan and Negahban, 2013; Sarwar

13 immaterial

14 e.g. during conversations, meals, at the cash register or public transport 15 conversations in public

and Soomro, 2013; Lee et al., 2014). There is no general consensus among researchers about the topic of smartphone or Internet addiction. Many researchers explore this field, and studies suggest that smartphone use can lead to addiction (Salehan and Negahban, 2013). But there are also researchers who infer that smartphones are rather habit-forming than addictive and that the frequent habitual use can better be labeled as annoyance than addiction (Oulasvirta et al., 2011). This issue leads me to the social norms approach. 4.2 Examples of applied social norms theory Berkowitz (2004), one of the founders of the social norms approach and social norms marketing, suggests that behavior is based more on “perceptions of how other members of our social group think an act”16 (p.5) than on actual norms and

that peer influences have a greater impact on individual behavior than biological, personality, familial, religious, cultural and other influences (Berkowitz & Perkins, 1986a; Borsari & Carey, 2001; Kandel, 1985, and Perkins, 2002 in Berkowitz 2004). The difference between perceived norms and actual norms are described as misperceptions. Through interventions it is tried to correct misperceptions of norms with a provision of normative feedback. (Berkowitz, 2004)

Even though success and effectiveness of interventions with normative influence is claimed (Berkowitz, 2004, p.2), criticism about the evidence of success and behavioral change as well as methodological limitations of their evaluations have been voiced (Lapinski and Rimal, 2005, p.128; Schultz et al., 2007, p.429). Schultz et al. (2007) provide a possible explanation for the lack of success in form of “boomerang effects” (p.430). People measure the appropriateness of their behavior on the perceived norm and how close their behavior is to the norm, yet it doesn’t matter if they are above or below the norm. Meaning descriptive normative information on occurrence of undesirable behavior may lead to an increase of the behavior by individuals, that have until then stayed below the norm. A solution to this dilemma comes from the focus theory of normative conduct, which suggests that the effect might be prevented by adding an injunctive message that the behavior is undesirable and disapproved of. (Schultz et al., 2007, p.430)

4.3 Media influence

When it comes to media influence on norms, research about sexuality or smoking can be found. The conducted studies conclude, that the indirect influence from perceived peer norms and the assumed influence of the media content on peers are greater than the direct influence of media exposure, even if the assumed influence on peers are misperceptions.

„The more subjects thought other students were exposed to pro smoking content the higher their estimates of peer smoking.“ (Gunther et al., 2006, p.62)

„Regardless of being possibly exaggerated and incorrect, adolescents’ heuristic estimate of media effects on peers may produce real and essential effects on them- selves.“ (Chia, 2006, p.600)

Studies of Chia, and Chia and Gunther also offer the projection effect as an explanation for their study results. The projection effect states that individuals project their own attitudes on peers and form perceived peer norms in this way. (Chia, 2006 p.601; Chia and Gunther, 2006, p.315) Chia and Gunther (2006) state further:

“Finally, and most important, the projection results affirm the validity of the effects of presumed media influence, as presumed influence remains significant even after controlling for the robust effects of students’ own sexual attitudes. “ (p.315)

I thereby conclude, that the presumed media influence is greater than the actual and direct media influence. For my analysis this implies that the influence of the perception of NYT articles in the individuals reference network is supposedly greater than the direct influence the NYT article has on the reader.

5 Data and methodology

To find an answer to my research questions I opted for a thematic text analysis with a quantitative and a qualitative part. Since I already had assumptions about the outcome of RQ1 I decided to work with the aforementioned hypotheses. For the purpose of verifying the hypotheses I found a quantitative analysis of my data suitable, whereas I found more value in a qualitative analysis for RQ2 because I wanted to examine it in an explorative way without previous conjectures. All in all I find that the mix of quantitative and qualitative analysis as well as the deductive and

inductive approach provides me with more in-depth knowledge and different perspectives. Even though the testing of hypotheses usually refers to the paradigm of positivism, I pursued a social constructivist point of view throughout my work, which according to Collins (2010) “challenges the objectivist stance of positivism” (p.40). But since paradigms are supposed to reflect the world views of the researcher, are a social construct themselves and their relationship to methodology is constantly evolving, I do not see a conflict in this matter (Collins, 2010, p.49). In this chapter I will elaborate which data was used and how it was selected for my work and go further into detail on how my content analyses were conducted.

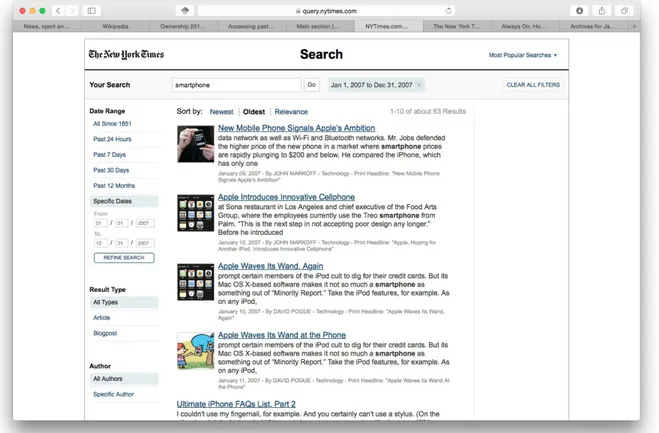

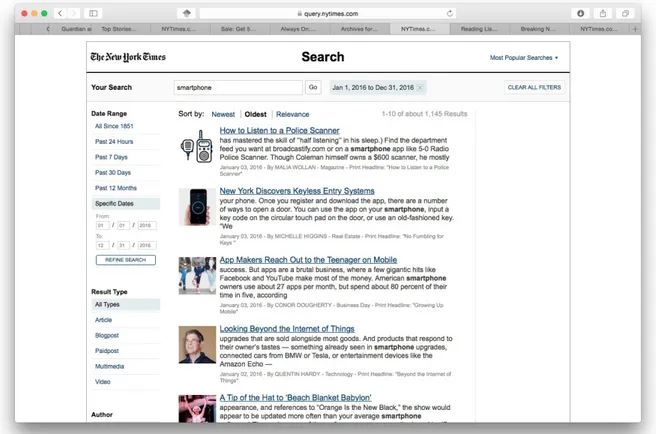

5.1 Data

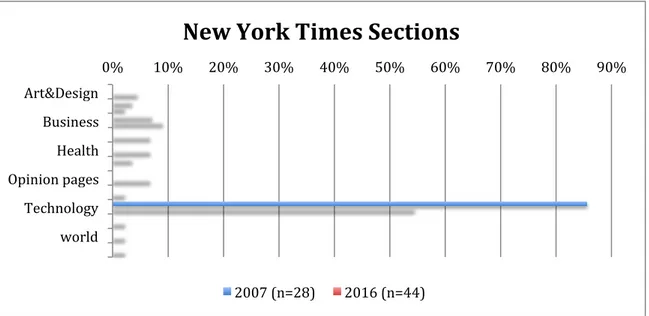

The data for research was accessed through the search option of the New York Times Website17, with the search term “smartphone” and then limited to the specific

dates of 01.01.2007 - 31.12.2007 and 01.01.2016 - 31.12.2016. The outcome for 2007 was 63 results and 1.145 for 2016 (see figure 08 and 09).

Figure 08: Screenshot of search results on NYT website for “smartphone” year 2007 (NYT Search ‘Smartphone’ 2007)

Figure 09: Screenshot of search results on NYT website for “smartphone” year 2016 (NYT Search ‘Smartphone’ 2016)

These results still included articles with the keyword “smartphone” only mentioned in various contexts but not as the main topic. Since these articles will not support finding an answer to my research questions I excluded them from my data population. For the selection process I established criteria (see figure 10) to exclude incongruous articles with a pre-selection process, where I looked at a number of different articles from both years to familiarize myself with reasons for exclusion. After the criteria were established I applied them on both search results.

Figure 10: Criteria for exclusion of articles

After the selection process I had two sample populations; the 2007 population included 28 samples and the 2016 population covered 44 articles (see appendix). This was a result I did not expect at first since the number of NYT articles with the keyword “smartphone” from 2007 (63 articles) was wide apart from 2016’s number (1.145 articles), I was surprised, that the actual 2016 population (44 articles) was not significantly greater than the 2007 population (28 articles). I think there are three main reasons how this could be explained: (a) Since the smartphone was much more common in 2016 than in 2007 it was mentioned in a lot more articles that were not smartphone related18. (b) In 2016 less reviews of various phones

were written (30% of all articles) than in 2007 (54%). (c) Much more other smartphone related topics were discussed in 2016 that were not on the 2007’s agenda that I excluded from my sample because smartphones were not the main topic19. For my content analysis I defined the sampling and coding units both as NYT

articles; every article is a sample and will be coded separately as one unit.

18 e.g. politics, sports, arts etc.

5.2 Methodology

The coding categories were constructed deductively and inductively in a multistage process of categorizing and coding as described by Kuckartz (2014): First I created sections labeled after McGuire’s media effect factors to group and create the main coding categories. I then formulated main categories derived from the research question, hypotheses and the framework from McGuire, Hall and the norm theories as well as from the described previous research. For RQ2 I furthermore added extra categories grounded in Bicchieri’s norm theory (see table 10). Table 02: Sections and main coding categories In a third step I searched through the data, starting to categorize the articles20 to build sub-categories where applicable and modify, adapt and differentiate the main categories according to the findings. Further I built new main categories that were not evident before. Subsequently I coded the entire data set with the new categories (see codebook in appendix). All quantitative categories were exhaustive and most of them mutually exclusive. In case of characterizations where multiple answers were possible, I additionally coded the data into positive, negative or neutral if applicable 20 10 for each year

to have mutually exclusive data for each article. To evaluate and compare the quantitative coded data I extracted the numbers and proportions of the sub-categories of both years, additionally built different pivot tables and diagrams where results were significant.

For the evaluation of the qualitative data I searched for collective behavior, expectations and common themes from the theoretical framework and coded material. Thus I could identify norms and ways of influence on norms and behavior according to my framework. After the qualitative analysis of all the samples, I decided to perform a thorough analysis of one example article of each population with McGuire’s media effect factors and Bicchieri’s norm theory to obtain more detailed data and be able to analyze and discuss influence factors on the grounds of a specific example.

5.3 Quality and Ethics 5.3.1 Quality

According to Kuckartz (2014) classical and long recognized quality standards in quantitative research are objectivity, reliability and validity. For qualitative research he argues referring to Flick “the classical standards cannot simply be transferred […]; rather they have to be modified and extended in order to take the procedural nature of qualitative research into account (see Flick, 2009, pp. 373-375). (Kuckartz, 2014, p. 152f.)” In the following table Kuckartz presents the comparison of classical quality standards with new standards for qualitative research according to Miles and Huberman (1995, ref. in Kuckartz, 2014, p.152), which I chose as a guideline for the quality of my work. Table 03: Quality Standards within Quantitative and Qualitative Research (Miles and Huberman (1995), ref. in Kuckartz 2014, p.152)

To ensure quality, validity, credibility and replicability of my work I conducted my research in a responsible and structured manner. However I am aware that there are certain limitations regarding the implementation of my method. Due to the timeframe of this thesis I was not able to do a pretest or code the material a second time to check for intracoder-reliability (Flick, 2016), nor was it possible to work with a second coder. These measures would have reduced possible human errors and subjectivity. A precaution I took for errors was to spread the coding to different days, so I could review previous coding with a fresh eye and spot errors. Additionally the production of a codebook makes my research more comprehensible and replicable.

The use of both quantitative and qualitative text analyses, the theoretical approach from three different angles, as well as the consideration of data from two different years almost ten years apart – which allows me to make comparisons, detect differences and extrapolate trends – grants me more insights and in addition strengthens the validity, credibility and transferability of my work. Conclusions for the selected years can be drawn and generalized for both years because my sample constitutes of the whole population of data from 2007 and 2016. 5.3.2 Ethics The material I used for the content analysis already existed, was published by the NYT and can still be accessed online. Further the method of content analysis is unobtrusive (Krippendorff, 2004, p.40). Therefore the material is not biased through me, nor is there an ethical issue since my work does not infringe personal rights.

6 Research results and analysis

6.1 Research questions I6.1.1 Results

To find the answer to my first research question I will look back on the two hypotheses that I formulated at the beginning, to analyze if they prove valid or not.

H1 – In 2007 the coverage of smartphones will be mainly positive and focus on technological aspects.

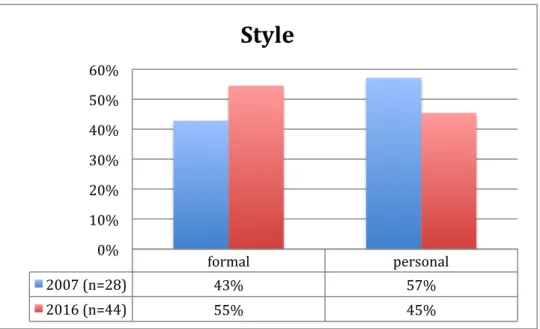

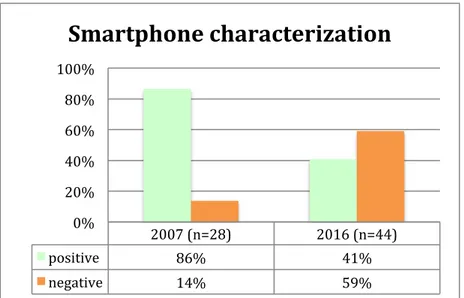

H2 – In 2016 the coverage will be more critical about the consequences of the pervasion and influence of the smartphone in society. 6.1.1.1 Tone of article To do this I am looking at different results from my coding table, starting with the overall tone of the articles. For 2007 (see figure 11), the tone in articles of the NYT about smartphones is mainly positive. 82% are written with a positive tone (64% positive and 18% very positive) compared to a low 4% of negative articles with 14% being neutral. In 2016 the numbers have almost evened out with a small majority (39%) of the articles written in a neutral tone, followed by 34% negative and 27% positive. Figure 11: Overall tone of examined NYT articles, 2007 (n=28) and 2016 (n=44) compared in % 6.1.1.2 Tone about smartphones

A similar pattern is to be found in the category how the author writes about smartphones in the examined articles (scale from enthusiastic to very critical) (see figure 12). In 2007 smartphones are predominantly described positive (75%) or even enthusiastically (14%) (4% neutral and 7% negatively) whereas in 2016 positive, neutral and negative descriptions make out 27% each of the articles with an additional 18% with very negative pictures of smartphones and thus leading to a majority of negative descriptions. The results in these two categories tone and tone

very negative negative neutral positive very positive 2007 (n=28) 0% 4% 14% 64% 18% 2016 (n=44) 0% 34% 39% 27% 0% 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70%