Pupils’

Feedback

Exploring feedback in a

contemporary school environment

Malmö University

Media Technology: Strategic Media Development Master thesis, 15 credits, advanced level

———

Student: Felix Kapolka Supervisor: Fredrik Rutz Examiner: Daniel Spikol Submission: 20/6/2019

Abstract

In a contemporary world saturated with technology, where data has become a means to

understand and optimize almost everything, the educational sector seems reluctant towards it. In order to change that, it is argued that formative assessment is a sustainable way to monitor feedback data for the purpose to improve school environment. Used in the classroom, it shifts the focus from the outcome of pupils’ learning to their real needs.

This study elaborates on the lack of feedback for teachers and the referring potential of technology usage in schools. Due to, inter alia, a co-creation workshop, novice teachers and designers collaborated to create several prototypes, which were used in a real classroom situation afterwards. Those prototypes enabled a deep understanding of the current perception of feedback as well as the technology awareness of students and teachers.

The research results were discussed from various angles, including young teenagers’ and experienced teachers’ views. The outcome analysis led to the need of a student-centred curriculum which offers explorative access to technology and feedback for everybody involved in a school environment.

Keywords

Student-centred learning, co-design, feedback perception, technology awareness, formative assessment

Acknowledgments

Since studying always means collaboration, I highly appreciate the cooperation with several people who I would like to thank below. Thank you very much:

● Creators of tools like SelfControl, Miro or Grammarly. You helped me to focus on the study’s tempting djungle of distraction.

● My employer, Goodpatch Europe, and its lovely team members who enabled me to take a year off.

● Malmö University, for an interesting programme, great teachers and a perfect study environment. Special thanks goes to my fellow student Rasmus who never hesitated to help me.

● Every participant of this study, who joined the workshops and

interviews. In particular, I would like to thank Steffen, who has been a great help even in overextending situations.

● Dad, for pushing me subconsciously to go abroad in order to do a master’s degree.

Table of Content

Introduction 8 Personal Motivation 9 Research Questions 10 Thesis Outline 10 Theoretical Framework 11Data and Monitoring in school environments 11

Feedback in the classroom 13

Technology as an enabler for better learning 15

Technology integration 17 Meta-reflection 19 Methodology 21 Research Design 22 Methods 23 Focus Group 23 Co-creation workshop 24 Observation 25 Prototype 26 Interviews 27 Co-designer 28

Qualitative data collection 28

Sampling 28

Documenting 29

Analysis 29

Ethical Considerations 29

Results 31 Phase 1: Understanding 31 Focus Group 31 Workshop 36 Phase 2: Prototyping 44 Prototype 44 Observation 50 Phase 3: Evaluation 51

Interview with the co-designer 52

Interview with pupils 54

Interview with a novice teacher 57

Interview with an experienced teacher 60

Discussion 64 Conclusion 69 Future Work 70 References 71 Appendix 74

List of Figures

Figure 1: The Design Thinking Model by d.school (2018) 21

Figure 2: Image of a research design by Gray (2013) 22

Figure 3: Custom graphic for this study’s research design, based on Figure 2 23 FIgure 4: Custom graphic to illustrate this study’s research participants 29

Figure 5: Image of a document camera 36

Figure 6: Timetable of the co-creation workshop 37

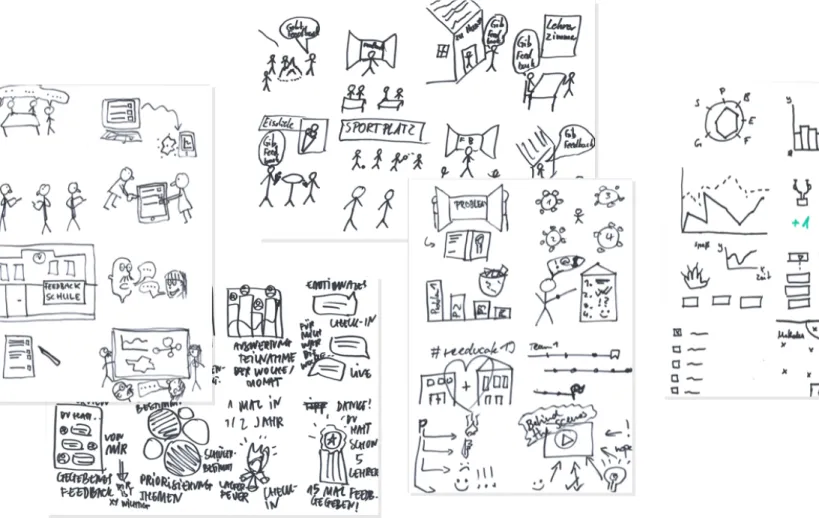

Figure 7: Scans of some Crazy 8-sketches 40

Figure 8: Storyboards of the Paper-prototypes 1 and 2 41

Figure 9: Images of Paper-prototyping process 42

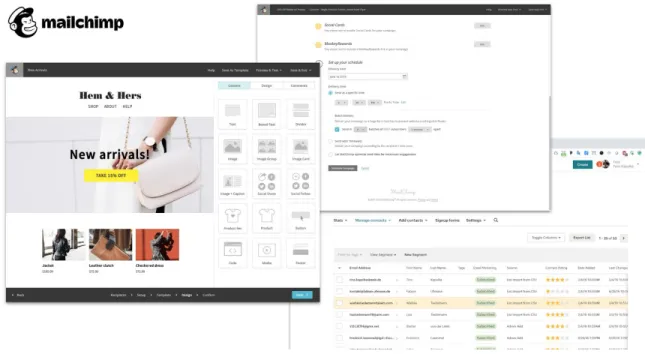

Figure 10: Three screenshots of mailchimp.com 46

Figure 11: Image of the prototypes online and offline version 47

Figure 12: Diagram to illustrate the access data 50

Figure 13: The Co-designer’s schedule 52

Figure 14: Nine images, taken during the co-creation workshop 74

Figure 15: All collected How-might-we questions 75

Figure 16: All collected Brainstorming ideas 76

Figure 17: All created Crazy 8-sketches during the co-creation workshop 77

Figure 18: Flowchart of paper-prototype 2: “Tip-Top-App” 78

Figure 19: Flowchart of paper-prototype 3: “Picknick” 78

Figure 20: Letter of the Week #1 79

Figure 21: Letter of the Week #2 80

Figure 22: Letter of the Week #3 81

Word list

Class teacher: The class teacher describes a dedicated teacher, who is responsible for

facilitate organisational tasks for one specific class of a school.

Curriculum: A curriculum describes the overall programme of a school.

Mentor: The term mentor is used in this study, to describe the dedicated teacher who is

responsible for a “Referendar” during its “Referendariat”.

Novice teacher: In this study, the term novice teacher is used to describe practising teachers

who are examined but have less than three years of work experience.

Pupil/students: During this thesis, students as well as pupils are equivalent terms for 10 to 18

years old people who join any kind of school.

Referendar/Referendarin: Examined teaching students running their Referendariat are called

Refendarin (female) or Referendar (male).

Referendariat: After the university degree, German teaching students have to do an internship

for one year and a half. During this period, trainee teachers are observed, advised and evaluated by a dedicated mentor.

School participants: In this study, a school participant implies any person involved in a school

environment, such as students, teacher, principals, parents and further staff members.

Sekundarstufe: The German equivalent of the English term secondary school is

Sekundarstufe. Similar to the English definition, it is deceived into Sekundarstufe 1 (lower secondary school) for students aged 10 to 16 , and Sekundarstufe 2 (upper secondary school) for students aged 16-18.

1. Introduction

We live in a contemporary world saturated with technology, where data has become a means to understand and optimise almost everything. The analysis of data in terms of improvements of us or others is omnipresent, especially in a filter bubble of people who ubiquitously deal with digital products. Endless apps for purposes like fitness, mental health, productivity and more, trigger required personal data in order to deliver feedback on our performances.

Naturally, car mechanics use software to detect a car's issues after one of its service lights startes flashing. Doctors use highly sophisticated tools to decrease their error rates by detecting specific diseases. Nobody claims the usage of such technology nowadays.

Furthermore, doctors and mechanics must use modern technology, as their patients and clients expect it. Otherwise, most doctors' and mechanics' performance would probably be

questioned due to their outdated processes (Ertmer, 2010).

However, one sector which still seems to highly question the usage of technology, just like mechanics or doctors do, is the sector of schooling. Furthermore, using digital resources in order to gather feedback seems even more laborious because giving and getting valuable feedback in educational environment is a challenge. In 2013, Bill Gates claimed in a TED talk that the majority of American teachers receive only one phrase in feedback context:

satisfactory. He talks about the importance of feedback as it describes how we learn with each other and that it is a significant need to improve in what we are doing. Therefore, Gates questions why teachers are one group of American professionals who do not get regular feedback. He also shows facts and figures of the Programme for International Student

Assessment (PISA) which ranked countries by their pupils' achievements in math, science and reading. One of the top-ranked participants is Shanghai and Gates ascribes this to their teacher feedback system which bases on collaborations between teachers. In weekly meetings,

teachers discuss their work in order to improve their teaching skills. Furthermore, the curriculum requires mutual observation and evaluation (Gates, 2013).

In 2009 a professor of education from Auckland/New Zealand published a study called "Visible Learning". In this study, author John Hattie compared 138 methods to influence students' learning outcomes. Furthermore, it is considered as "teaching's holy grail" by the British teaching magazine TES. Hattie explains visible learning as an approach for teachers to acquire knowledge of how to see learning through the eyes of their students in order to

improve their teaching. "Providing Formative Evaluation" as well as "Feedback" are ranked as third and tenth most effective methods researched in this meta-study.

This study's primary purpose is to explore feedback in a contemporary school

environment. To achieve a broad understanding of the schooling context, the study documents a variety of research methods which consist of many direct collaborations with teachers. This enables the study to research on real circumstances schools have to deal with at the moment. Further, this study tries to find potential gaps in communication between diverse school participants such as teachers, pupils or school leaders. Thereby, the study elaborates on those participants' perception of technology and feedback in the context of schooling. Finally, the study wants to demonstrate future approaches to the facilitation of teaching improvement by analysing the study's findings.

1.1.

Personal Motivation

Gates’ and Hattie’s claim is picked up in the state examination by Steffen Lubkowitz, a teacher examined in 2016 at the University of Rostock, Germany. In his study: “Feedback on teachers’ teaching by student teachers” (Original German title: “Feedback zum

unterrichtlichen Handeln von Lehrerinnen und Lehrern durch Lehramtsstudierende”) he found out that giving feedback is not only a matter of time and costs. Furthermore, based on his analysis of structured surveys, Steffen claimed that most teachers tend to dislike feedback, even if they agree on its potential advantage. (Lubkowitz, 2016)

Due to our personal acquaintance, I exchanged regularly with Steffen on the perception of feedback in different environments. At the time, I was working in a digital product design agency and wondered about all circumstances he had to deal with, because in my job I was used to get feedback continuously: At work, me and my colleagues were used to have stand-up meetings in the morning and several work-related chats with fellow designers, developers or product owners during the afternoon – either digitally by several messenger apps or just physically by face-two-face conversations. Furthermore, we worked with different online services to monitor and compare our personal and company-wide

development. Based on them, we had face-to-face meetings every three months in order to discuss our goals. My former employer had several methods to keep its employees

high-performing by providing feedback and exchange continuously.

In short, I would like to understand the reasons for these differences between the profession of a teacher and a product designer. Therefore, I use my private network of both,

designers and teachers, in order to explore the field of feedback in a contemporary school environment.

1.2. Research Questions

(1) How does the environment influence technology awareness in schools?

(2) How to design a digital feedback process in a contemporary school environment?

Based on the thesis' introduction, the research questions cover the efforts to enhance schooling by focusing on teachers improvement. Therefore, the research investigates

"Feedback" as the chosen term to work with during the study. Feedback broadly describes the exchange between individuals in order to assess something within an appropriate setting (Dann, 2017).

Furthermore, the questions set the context of the research by defining its reference points as school environment and technology awareness. However, school environment does not only mean infrastructure. Instead it describes everything around students, including, for instance, the curriculum, the whole staff as well as the physical and digital infrastructure of a school. By embedding "contemporary" into the second research question, the study

emphasizes to rather focus on current circumstances of schools than anticipated future

scenarios. Finally, the research questions lead the research to two main focus points: feedback and technology in the context of school.

1.3. Thesis Outline

The present study started with an introduction (chapter 1) in order to inform about the global research topic and the self-chosen research questions. Following this, the theoretical

framework (chapter 2) documents an analysis of various literature used to understand the theoretical background of the study. Thereafter, the methodology chapter (3) explains the research design as well as used methods in detail. Furthermore, it describes the ethical considerations and the study’s validity. Chapter 4 depicts findings made during the three phases of the research: Understanding, Prototyping and Evaluation. Those findings are discussed in chapter 5, which also includes the study’s conclusion and first approaches for future work. Finally, all used references are listed (chapter 6) and the appendix (chapter 7) is attached.

2. Theoretical Framework

The following chapter aims to document and discuss contemporary literature regarding the research topics around data gathering, feedback and technology. All topics are researched in the context of schooling. Due to the topics’ wide range of definitions, the literature review helps to get an understanding of this study’s overall context.

2.1. Data and Monitoring in school environments

Because data and digitalisation become more and more prevalent in society, their presence posits studies surrounding data and monitoring in schools and similar educational

environments. In the context of schooling, Scherman (2017) defines data as information, either regarding a measurable amount of something (quantity) or to the quality of something, which is systematically gathered and structured to show some aspect of specific research. The collection of those data can be based, inter alia, on surveys, assessments, observations or student background information. To use data, it is essential that the people who work with it understand them deeply before they can interpret them, in order to improve something (Scherman, 2017).

In contrast to this, Dann (2017) warns that quantitative data gathering as method for measuring education outcomes could have a misleading impact on teachers. Implementing scoreboards and standardised tests lead teachers to narrow down their teaching, in order to improve their scores by ignoring the broader overall teaching goals (Dann, 2017, p. 12). So far, several monitoring systems for schools focus on technology-based services such as adaptive computer testings or automatically uploaded data from internal school management systems. In this way, they spare teachers and pupils from manual time-intense data collection (Scherman, 2017, p. 13). Even Hattie agrees on that metaphorically:

“My cricket coaching requires monitoring process and not just performance – my aim is to be a coach, not a score keeper.“ (Hattie, 2008, p. 240)

In a 2017 study, Scherman states that mindful usage of data improves the learning situation and its success significantly. She points out that schools will only be able to enhance their teaching if they take concrete action and evaluate those action’s impact after any data

training methods for teachers, it is a crucial driver for high-performing schools (Scherman, 2017, p. 19). Levin confirms this and entitles data usage as “Hallmark” when data collection goes beyond administrative roles. As an example, he mentions student-owned evaluations for teachers and principals (Levin, 2013, p. 12). Additionally, even Hattie proved those

statements through numbers. Due to a meta-analysis of many teaching and learning methods, he identified effect sizes of them in order to measure teaching methods’ efficiency. Through this, Hattie created an evidence base for learning success which is crucial to evaluate

affordances for better teaching. Otherwise, if people have nothing to rely on, they cannot compare their potential success.

Furthermore, his research is pointless as he found out that while teachers get forced to use data-related judgement models, the effectiveness of feedback washigher than with their personal judgements (Hattie, 2008). However, as Dann (2017) points out, defining what works is tricky:

"Those who want to determine what works in education are doomed to fail, because in education, ‘What works?’ is rarely the right question, for the simple reason that in education, just about everything works somewhere, and nothing works everywhere." (Dann, 2017, p. 16)

Even though Dann's statement is widely applicable and related to data in schools, there are issues with both the gathering and processing of data, if it is dealt with at all. Indeed, schools often struggle to both collect and analyse data, although they have access to monitoring systems. Those external systems provide schools with data of their current

learning achievements. They also offer identification of different indicators which seem to be lacking in their performances. Those indicators could be business topics like financial issues as well as infrastructure related things like class sizes or student’s attendance rates (Scherman, 2017, p. 20).

However, any receiver of feedback interprets its information (data) in an individual way which might fit or not fit into a senders intention. That is applicable for systematically gathered data as well. (Dann, 2017, p. 45). Therefore, Dann challenges the validity of those data. So far, most monitoring systems focus on easy-measurable content which can be

influencing factors of learning performances. Social or human factors are not that easy to compute and need a broader formative assessment (Dann, 2017, p. 44).

Along the same lines, Scherman (2017) identifies crucial problems regarded in systematic monitoring methods. Similar as global scoreboards, mentioned earlier in this chapter by Dann (2017), monitoring systems also lead to put pressure on the teachers since they might fear consequences in case of weak performances of their students. As a result, they ignore the curriculum and only focus on the measurable contents (Scherman, 2017, p 25).

2.2. Feedback in the classroom

In a broad sense, feedback is understood as received information which can be considered when modifying or improving something within a context (Dann, 2017, p. 35). Hattie (2008, p. 174) referred to a provider of feedback as “agent” and describes the delivered information as a specific part of the agent’s perception or doing. In an education context, the purpose of feedback is to influence a receivers’ experience (Dann, 2017, p. 38). The receiver can also be described as learner.

Additionally, Hattie clarifies that giving feedback has nothing to do with rewarding but rather sharing information about the context as well as filling “a gap between what is

understood and what is aimed to be understood” (Hattie, 2008, p. 174). Furthermore,

feedback can provide different layers of information; the first one pays attention to the lack of knowledge and the second supports the process of how learners approach this information (Dann, 2017, p. 38). Dann (2017) also affirms Hattie’s classification of four different kinds of feedback: “Feedback on the task; feedback on the processes need to complete the task;

feedback on the process of self-regulation; and feedback on the person involved” (Dann,

2017, p. 40).

Further, Hattie points out that feedback is a reaction of execution and emphasizes that it does not have to be accepted by learners. A learner can agree, attach on or keep the

information in memory. He also describes feedback as the most valuable possibility of influencing learning. Unfortunately, feedback does not occur often enough and still needs to be researched, especially in school environments. That means ,for example, classroom interactions or the processes students are learning with (Hattie, 2008, p. 178).

A requirement for successful feedback usage is the teachers' skill of sending feedback based on given tasks or standards, simple and clear phrased. learners should have an as individual experience as possible, speak in a language that is recognisable and easy to

understand. Teachers need to be aware of the students’ incomplete knowledge and must be careful about the feedback’s syntax (Dann, 2017, p. 40). This calls attention to another

important requirement: trust. Trust describes the relationship between teacher and learner and is assigned as a major requirement for a successful feedback process. Even if trust does not directly influence student learning, it helps to decrease a student’s anxiety about the unknown. (Hattie, 2008, p. 240) Learners also need to intend feedback. That means that feedback can only be effective if the information becomes part of the learner’s cognitive process. If one accepts those processes it will increase the chance of narrowing potential knowledge gaps self-regulated (Dann, 2017, p. 42). Scherman describes it similar but with the role of a receiver’s willingness. To accept feedback successfully it needs to be considered as reliable and fair (Scherman et al., 2017, p. 14). Dann (2017) also collects four ways of how students might deal with received feedback:

“First, they might increase their effort in order to move nearer towards the standards required. Second, they may abandon the standard and not have it as part of their learning gap. Third, they might change the standard so that it is more acceptable to the framing of their learning gap. Fourth, they might reduce the feedback message” (Dann, 2017, p. 41).

What this tells us is that learners also need to take on responsibility when receiving feedback. To gain useful feedback, it is essential to see feedback as a process of improving one's potential way of learning and creating. Furthermore, people need to embrace feedback as a serious cognitive process.

Scherman (2017) argues that the central issue of computational feedback systems, like the monitoring system mentioned earlier in this chapter, is their focus on accountability assessment and its relation to old cognitive patterns (Scherman et al., 2017, p. 33). Those patterns inhibit a more creative and collaborative learning approach which current curriculums should represent (Scherman et al., 2017, p. 28).

Formative assessment enables this precisely. It describes a process for evaluation and improvement in fixed timeframes and criteria. Used in classroom, it shifts the focus from the outcome of students learning to the needs of the learners which teachers must work on (Beatty et al., 2009, p. 10). Beatty’s model for "Technology-enhanced formative Assessment" offers this. It is however useless as he also argues for data which teachers should use to understand better their students' minds (Beatty et al., 2009, p. 10). Hattie (2008) also emphasises on

formative assessments' positive influence on students' learning achievements – regardless their age or status as well as the amount and rhythm of the data gatherings. The usage of formative assessment as a tool for self-improvement is what increases teaching-skills extraordinary (Hattie, 2008, p. 181).

Therefore, Beatty (2009) investigated classroom response systems. Technology, which enables surveys or digital student interactions during lectures through different input devices. (Beatty et al., 2009, p. 1) This helps educators to gather feedback data without claiming performance issues based on anxieties like gender.

2.3. Technology as an enabler for better learning

Technology usage for formative assessments leads to the broader discussion of technology usage in classrooms at all. Ertmer (2010) requires technology as a fundamental part of good teaching. She claims that teaching is only valid if it is combined with essential digital tools and resources.

"Teachers can think they are doing a great job, even if they or their students never use technology. Although this may have been true 20 years ago, this is no longer the case. We need to broaden our conception of good teaching to include the idea that teaching is effective only when combined with relevant ICT tools and resources." Ertmer (2014, p. 6)

Sipilä (2014) confirms this by mentioning that teacher still do not understand the significant role technology plays in life outside school and that this fact has to be respected (Sipilä, K. 2014, p. 13). This is echoed by Heikkilä (2017), who also explains that the usage of technology should not depend on teacher's mood or set of skills and experiences. Even if a teacher doesn't like technology, it is definitely a part of most students’ everyday life.

Technology also reflects the environment students live in. They are "digital natives" who grew up seamlessly with electronic devices. Teachers and principals need to take into consideration that learning takes place in those contexts (Heikkilä et al., 2014, p. 10). This shows that the choice of technology rather matters and that there is a need for seamless integration of digital content in future curriculums (Reidsema et al., 2017, p. 38).

Furthermore, technology enables competences often called twenty-first-century skills. Digital devices like Laptops or tablets help students developing skills to communicate and

such competencies will help students in their later lives to solve problems which do not exist yet (Heikkilä et al., p. 10).

The value of students' digital competencies is often underrated. They search and find creative answers quickly can communicate rapidly and are skilled to facilitate their thoughts with the help of software. Moreover, embracing this set of skills is one way of increasing student engagement (Heikkilä et al., p. 3) and therefore ought to be incorporated into schools more tangibly.

Due to those skills, teachers can focus more on background processes and rather work as a mentor than the all-knowing. Heikkilä (2017) calls their new role "facilitators of endless learning”, while Scherman calls teachers as "agents of change" who takes care of the

mentioned 21st-century skills. Building on that, this indicates that changes are needed in the way monitoring is performed to involve and understand teachers’ responsibility in the context of teacher responsibility (Scherman et al., 2017, p. 28). According to Ertmer (2010), teachers accept those approaches as far they see that they satisfy students' needs and beliefs in it. Sipilä (2014) describes the integration of technology either as (1) an agitator for change or as (2) a tool set. The first he calls an "educational push" which means that the integration impulse is coming from an administrative angle by for example principals or municipality's curriculums. The second approach (the tool set) he calls "educational pull" which needs to be initiated by executors: the teachers. The more they use technology on their own terms, the more they will see the impact it will have on the students' achievement and motivation (2014, p. 6).

If this is given, teachers are more natural to convince using new methods to address significant learning achievements. Otherwise, if they do not see links to any student

achievements, such as better grades or faster-reaching learning goals, of course, they will instinctively hesitate to integrate technology into their lessons.

"As long as the curriculum does not tie the use of ICT concretely to school subjects being taught, it is in the teacher’s hands to decide whether to turn on the devices or to carry on as usual. If there are glitches in equipment on hand, lack of knowledge of how to use it or uncertainty whether it is promoting learning, the devices will be left untouched." (Sipilä, 2014, p. 15)

In addition to this, teachers need support from professionals (Levin et al., 2013, p. 17). Due to their packed schedules, they do not have enough time to investigate technology or new approaches to teaching (Sipilä, K, 2014, p. 12). This leads to the question of how this kind of support could look like.

2.4. Technology integration

Levin (2013) and Ertmer (2010) claim that a critical factor for successful technology

integration is a shared vision among the entirety of a school’s staff. A comprehensible vision enables an aptitude for problem-solving and innovative school culture, as well as a basis for individual support and training – potentially based on gathered data (Scherman et al., 2017, p. 19). Those shared visions require leadership. Dedicated people who are not only responsible for the development and promotion but also for the execution of it. This means that these leaders have to set up specific goals, analyse the status quo as well as plan and evaluate actions for future technology integrations (Levin et al., 2013, p. 19). They also need to be able to support everybody in finding their niches and build on their strengths as well as building teams and working with them (Levin et al., 2013, p. 10). Furthermore, Ertmer (2010) argues that enabling possibilities of observations and presentations of school related benchmarks are also part of successful leadership. However, this will not work without collaborative

processes. Technology integration requires an open-minded school culture of positive connections between all components – including teachers, students, principal, classroom, learning materials and teaching methods (Sipilä, 2014, p. 5).

Ertmer (2014, p. 18) claims for the development of "communities of practice" to help each other limiting technology anxiousness or to collaborate on methods of technology integration. Teachers need a safe space where they feel comfortable to test new ideas on their own without any dictation of curriculums or principals. Furthermore, they rather need to feel empowered to take risks inside an environment where failing is not an issue than not to try

(Ertmer, 2010, p. 22). Furthermore, Levin (2013, p. 13) argues for flexibility and ability of iteration when it comes to technical issues.

"To truly change beliefs, teachers need to feel comfortable testing new ideas, based on these beliefs, in their classrooms. To adopt technology as an innovation, teachers need to be willing to take risks, remain flexible, and be open to change." (Ertmer, 2010, p. 22)

Furthermore, Levin (2013, p.11) found out that schools which have a student-centred learning approach are most successful. This shows that students have to be part of those communities and collaborations, too. Student-centred teaching means to involve students actively into the facilitation of their learning process. It offers opportunities for them to influence lectures' content through different working methods based on problems, projects or enquiries. Besides, those higher engagement and responsibility of students also increases the possibility of formative assessment and student-feedback (Reidsema et al., 2017, p. 37).

Heikkilä (2017, p. 3) connects student-centred teaching to the concept of

human-centred design. The core principle of human-centred design is to involve potential end-users in the whole design process, which is based on three phases: inspiration, ideation and implementation (IDEO, 2015). This kind of involvement empowers students to feel more engaged in influencing the context they are learning in (IDEO, 2015). Also, it allows them to aquire 21st-century skills.

"Design-driven education is defined as project-based learning where a learner is actively involved in the planning,

implementation and evaluation of the learning activities. It emphasises the comprehensive, phenomena-based and creative nature of learning and recognises that ICT can enhance these kinds of learning processes." (Heikkilä et al., 2017, p. 4)

Another approach is to implement new roles in a school's ecosystem. Levin (2013, p. 12) found that a dedicated person responsible for technology is worth to install. Such

facilitators work individually with teachers and their personal development. They understand both, curriculum and pedagogy on the one hand as well as technical circumstances on the other hand.

Since schools usually tend to have funds neither for hiring nor for specific pieces of training or conferences, Levin (2013) claims that the award-winning schools he studied appointed their teachers to lead those roles. As Reidsema (2017, p. 10) stated, schools and their classrooms get more and more recognised as spaces for activity rather than passive information exchange. Since students can reach every theory online, wrapped into endless channels, classrooms should be used for real problem-solving. Teachers are working hard already to implement technology into their lectures regularly and to keep their students engaged without missing their actual curriculum. Also, through technology teachers are even more able to link any events from the present to their current curriculum and make them more relevant (Levin et al., 2013, p. 14). This kind of teacher empowerment is also described by IDEO (2012). They describe that teachers become designers of their own classroom experiences. It improves their role as facilitator and let them grow to an "agent of change" instead of "the passive implementing agent" (Scherman et al., 2017, p. 28).

To get funding and develop partnerships, Levin (2017) recommend schools to be more entrepreneurial. Some schools explore different ways to shift financial resources for textbooks as an example of more technology-driven materials. She also claims for partnerships with parents or their businesses, as well as different institutions like universities or other higher educational institutions in order to improve resources and opportunities. However, she found out that ubiquitous technology usage seems to be impossible so that approaches like the bring-your-own-device model are also suitable alternatives to go with (Levin et al., 2013, p. 16).

2.5. Meta-reflection

The literature review opens up several exciting topics and approaches to the study. Regarding the potential impact of a school environment on the technology awareness of school participants, the literature showed the potential of collaborative processes, especially by the integration of students. Furthermore, many references emphasize on the need of a shared vision among all involved teachers and students of one school. Opinions on students’ ubiquitous technology access are still diverse but enable so called 21st-century skills, meaning abilities to solve problems which not exist yet. Therefore, the students’ life outside school needs to be considered because that takes place in digital environments more and more.

However, referring to the research’s second question on digital feedback processes, the literature uncovers the high efficiency of feedback and formative assessment in schools. It

influences learning deeply. But, the usage of data in schools is a sensitive topic even if the value of data driven feedback systems are proved. Digital data and with it technology integration such as a classroom response system require high technology awareness. To bridge the gap between the different levels of awareness between teacher and students, a higher integration of the students’ competencies might be worth considering in the present research.

3. Methodology

This study focuses on an exploration of the lack of constructive feedback needed to increase the quality of teaching and aims to figure out and define its reasons. An inductive research approach using qualitative research methods is appropriate because quantitative data which covers relevant experiences in schools are rarely documented and accessible. Research through design is a suitable research methodology since it is a proved research approach for framing problems which in turn, supports the understanding and definition of the gaps in the chosen field of study (Zimmermann et al., 2007). Furthermore, research through design requires the use of a design action:

“We use the term research through design to indicate studies in which knowledge is generated on a phenomenon by conducting a desgin action, drawing in support knowledge from different disciplines, and reflecting on both the design action and an evaluation of the design result in practise.” (Stappers, 2014)

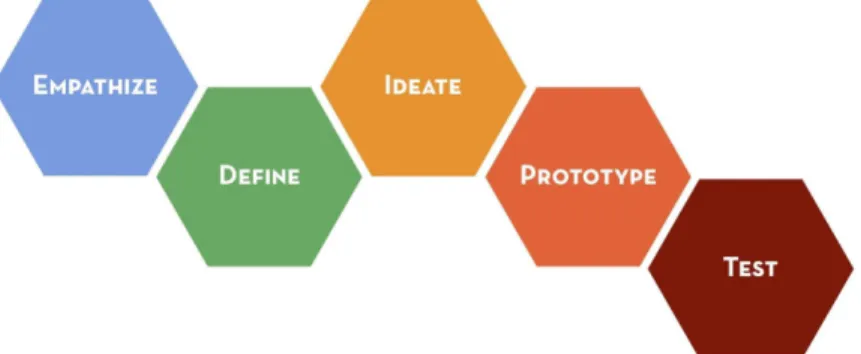

To deliver such design action this study uses "Design Thinking". Design thinking is a human-centred design methodology which can be described as a solution-based framework. The methodology invites a diverse group of people to tackle different issues by creating innovative solutions (Brown, 2009).

This study focuses on the model proposed by Hasso-Plattner Institute of Design at Stanford (d.school). It is based on five stages and a pool of exercises covered in a flexible, non-linear process. The stages are not sequential, can be iterated several times and also influence each other.

Moreover, next to its benefits in terms of a design action, Zimmermann et. al (2007) recommend Design Thinking as method to ground the theory - meaning the gathering of different insights of the researching problem. According to its inductive approach, this study uses grounded theory to discover and explore the explained broad problem of teacher

feedback. Grounded theory is a social scientific approach to collect and analyse qualitative data such as written protocols of scientific interviews or observations in order to create theories (Strauss, 1997).

3.1. Research Design

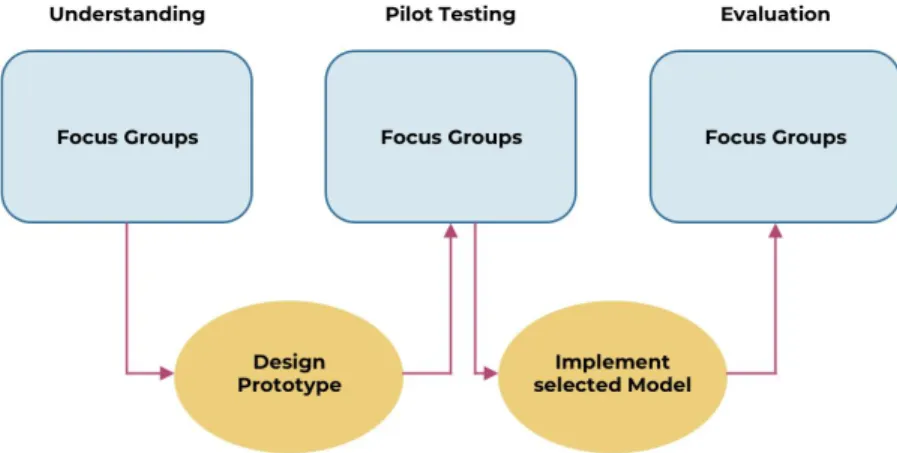

In the beginning of the study, I used the depicted research design framework (Figure 2) for product development because it covers most of my previously described methodology

approaches. The framework is based on the use of focus groups. Since I already had a pool of teachers recruited who were willing to participate in my study, my initial idea was to work with them constantly.

Figure 2: Image of a research design by Gray (2013)

Due to a potential lack of availability of the focus group during the research’s time frame, I decided to increase the pool of methods and added an observation session, as well as expert interviews into the research process. This decision gave me more flexibility in terms of data gathering since I was not depending on the entire focus group’s schedule. Moreover, I changed the concept of having one dedicated focus group to an easier accessible pool of experts.

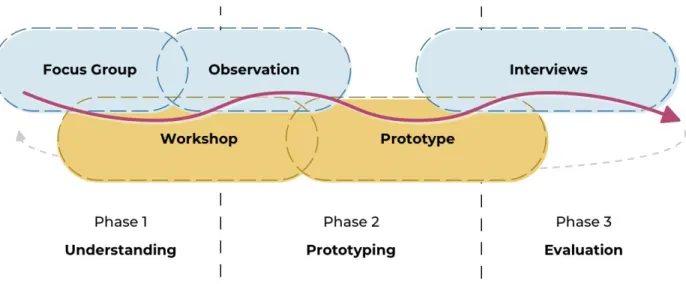

Furthermore, the initially chosen graphic (Figure 2) does not represent the nonlinear nature of a design thinking-based process. Therefore, I customized the graphic to show how

my chosen methods correlate with each other. I kept the three phases as description for three steps of my study but rearranged the shapes which represent the used methods. Furthermore, some methods were also used between the phases. Meaning, for example, that the workshop or observation covered research parts of the understanding phase as well as the testing phase. The research phases are overlapping.

Figure 3: Custom graphic for this study’s research design, based on Figure 2

3.2. Methods

Based on the used research design, the following sub-chapter explains each of the methods used during the research.

3.2.1. Focus Group

A focus group can be described as a discussion of multiple people managed by a dedicated facilitator. According to Gray (2013) focus groups help to trigger different opinions on a specific topic, through the generated discussions. Compared with individual interviews or surveys, it points out the range of opinions people might rather have than individual values or persuasions. Moreover, participants can build on and influence their arguments. This serves a broad view on several angles of the focus group. (Gray, 2013; IDEO, 2015)

"Focus groups can be used at the exploratory stage of a study, for example, when the themes or boundaries of a subject are unknown or unclear, and when the key constructs of investigation need to be identified." Gray, D. E. (2013)

As Gray (2013) argues, focus groups also enable to decide on a study's research direction, especially in its beginning. Accordingly, this study used the focus group method to narrow down the initial research question as well as gather general insights about the

participant's thoughts on technology and feedback, both in the context of schooling. Since the study's basic problem was defined as the issue of lacking qualitative assessment in schools it was important to understand the teachers' view on it. The actual aim of the focus group was to agree on one role of a school environment which teachers potentially use to gather feedback from.

3.2.2. Co-creation workshop

Co-creation or co-design describes the idea of bringing designers and non-designers together to enhance their collective creativity (Sanders, 2008, p. 3). Especially in the beginning of a development process, co-creation can increase a solution's potential sustainability (Sanders, 2008, p. 6). The methodology tries to tackle the issue that some problems need to be solved already but are not known yet.

"We are no longer simply designing products for users. We are designing for the future experiences of people, communities and cultures who now are connected and informed in ways that were unimaginable even 10 years ago.“ (Sanders, 2008, p. 7)

Therefore, Sanders argues that one rather needs to consider people's purposes than people's products as category to design for. Furthermore, roles in co-creation are fluid. Instead of that experts only act passively, they are active parts of the design team which requires that also non-designers have to learn design tool to express themselves appropriate. Vice versa, designers need to do actual field work as well to understand the peoples' purposes exactly. Overall, the role of designers and researches are merging. (Sanders, 2008)

A specific type of workshop which tackles several ideas from co-creation is a "Designathon". Inspired by "Hackathons" that are also workshops in which different

test ideas of a mixed group of designers and end-users, especially when the major problem is not entirely defined (Torrente, 2019).

Basically, Designathons are shorter versions of "Design Sprints" which were initially invented to help start-ups, developing important solutions in just one week (Knapp, 2016). Through a pool of exercises, workshop participants run through specific parts of the Design Thinking process. The aim of Design Thinking is to test and iterate solutions until they form viable solutions. It helps to understand the problem quickly and its potential benefits:

"You won't finish with a complete, detailed, ready-to-ship product. But you will make rapid progress, and know for sure if you headed in the right direction." (Knapp, 2016)

3.2.3. Observation

A focus group is basically a discussion of multiple people which is managed by a dedicated facilitator. Furthermore, it helps to trigger different opinions on one specific topic because of the discussions it generates through its conversational character (Gray, 2013).

Compared with individual interviews or surveys, it rather points out the range of opinions people might have than individual values or persuasions. Moreover, participants can build on and influence their arguments. That serves a broad view on several angles of the focus group. (Gray, 2013; IDEO, 2015)

"Focus groups can be used at the exploratory stage of a study, for example, when the themes or boundaries of a subject are unknown or unclear, and when the key constructs of investigation need to be identified." Gray, D. E. (2013)

As Gray (2013) argues, focus groups also enable to decide on a study's research direction, especially in its beginning. Accordingly, this study uses the focus group method to narrow down the initial research question as well as to gather general insights about the participants’ thoughts on technology and feedback, both in the context of schooling. Since the study's basic problem was defined as the issue of lacking qualitative assessment in schools it was important to understand the teachers' view on it. The actual aim of the focus group was to agree on one role of a school environment which teachers potentially use to gather feedback from.

In order to document all thoughts and ideas the focus group conversation was audio-recorded. Since the whole discussion was in German, the most valuable quotes were first transcribed and then translated into English as exactly as possible.

3.2.4. Prototype

The method of prototyping describes the usage of an artefact in a context of research through design (Stappers, n.d.). "Artefact" means any result, not necessarily physical. For example, services or virtual experiences can be prototypes as well (Brown, 2009). They can be described as first drafts of products; people can interact with or experience them. They help researchers face their theory in the real world to enhance knowledge about the studied topic (Stappers, 2014).

Furthermore, prototyping enables people to try different approaches by the same time. Due to its potentially rapid and hands-on process, it enables an early evaluation of a potential solution even if the problem seems to be highly complex. The faster first ideas get sketched and shaped, the faster they can be judged and improved without huge costs for productions.

"The goal of prototyping is not to create a working model. It is to give form to an idea to learn about its strengths and weaknesses and to identify new directions for the next generation of more detailed, more refined prototypes." Brown, T. (2009)

Overall, Strappers (2014) defines the major benefits of prototypes in their possibility to make future scenarios more tangible, to confront theory with real world circumstances, to provoke discussions between involved people and to show a research's current state in its process. However, prototypes can be created in several ways. Wensveen (2015) distinguishes between three different categories. (1) Prototypes can run alongside the research and help testing its insights. There, Wensveen (2015) describes the prototypes as experimental component or as a means of inquiry. (2) Another way to use prototypes is to gather the relevant research content through it. The prototype works as archetype for data collection. (3) In addition, researchers can focus on the process behind prototyping and observe how the artefact was designed. The prototype helps to visualise and evaluate the process behind. It works more as vehicle for investigation.

This study uses prototypes as a means of inquiry, meaning that the created prototype helped to evoke discussions between users, which in turn provided useful information from all

teachers and students who used or experienced it. Through the prototype, the researcher proves assumptions and learnings from previous used methods like the focus group or co-creation workshop.

3.2.5. Interviews

Listening and learning from people one is designing for is a core principle of human-centred design (IDEO, 2015). A method which helps gathering authentic information of these people is conducting interviews (Grey, 2013). Furthermore, oral interviews prevent interviewees from writing which often feels more confident compared to talking. Obviously, it also takes less time and makes it easier as well as more comfortable to participate in interviews (Gray, 2013).

Semi-structured interviews are conversations without strict questionnaires. Rather, they come with a list of topics than with concrete questions. The interviewer is engaged to lead the interview's direction based on the interviewee’s answers. Furthermore,

questionswhich were not planned initially may be asked as well. In this way unexpected angles can be discovered and investigated directly. The loose questionnaire also allows to dive deeper into an interviewee's answer which enables the interviewer to ask for more details to clarify potential misunderstandings (Gray, 2013; Blandford, 2013).

"This is vital when a phenomenological approach is being taken where the objective is to explore subjective meanings that respondents ascribe to concepts or events. Gray, D. E. (2013)"

Gray emphasises on a semi-structured interview's benefit on phenomenological approaches like, for instance, prototypes. On the one hand, interviews were used in this study to gather knowledge around the topics of technology and feedback in schools. In addition, interviews were also conducted to gather feedback for the prototypes which were created for the purpose of testing possible approaches of the research question. To gather data as

qualitatively as possible, it is important to interview a diverse range of target group members. Since the research question handles the communication between teachers and students this study triesd to cover both roles.

3.2.6. Co-designer

In order to have the possibility to work directly with teachers and classes, the role of a voluntary co-designer was created. Fortunately, Steffen Lubkowitz, a participant of multiple methods during the study, agreed on assisting in the prototyping phase by handing out the prototype and do several unrecorded and unstructured interviews with his students.

As Roschelle (2006) states, co-design covers many aspects of the research's

human-centred design approach and offers to create a deeper involvement of the prototypes potential target group, consisting of teachers and students:

"The co-design process can play a role in creating a tighter integration of curriculum and technology through the involvement of teachers in the design of innovations that they can meaningfully use in their classrooms" Roschelle (2006)

Steffen's support enabled the test of the prototype in a real school environment and gather further qualitative research data through multiple semi-structured interviews via phone calls during the prototyping phase.

3.3. Qualitative data collection

By conducting several methods to exchange with participants in the field of study, all three research phases include qualitative data gathering. This chapter tries to explain the choice of participants, the way the researcher documented all findings as well as the analysis strategy of the collected results.

3.3.1. Sampling

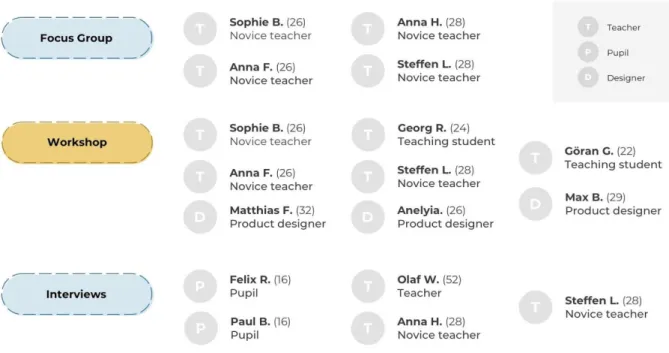

Since the research tries to explore a contemporary school environment while following a human-centred design framework, the researcher tried to collaborate with as most school participants as possible who are willing to contribute to the study's idea. Due to the thesis' limited time frame and personal preferences, most of the research participants are out of the researcher's circle of acquaintances, meaning that most of them are based on personal friendships. Furthermore, the two interviewed students are members of a friend's football team. Additionally, to support the teacher's creativity and improve the overall productivity during the co-creation workshop, friended product designers were invited as well.

Figure 4: Custom graphic to illustrate this study’s research participants

3.3.2. Documenting

Because all qualitative research takes place in German-speaking environments, conversations are audio-recorded and roughly transcribed. Of course, the analysis is made in English. Therefore, the most valuable quotes are processed during the results section of this thesis. Visual insights, created as part of the co-creation workshop, are scanned and attached in the appendix. Furthermore, access data of the prototype is documented and part of this study's results section.

3.3.3. Analysis

In order to analyse all gathered learnings, from the literature review as well as the qualitative methods, the collected quotes were linked with each other through the method of "affinity mapping". It is a technique to group large amounts of quotes and visualises their connections in order to synthesise the findings (Dam, 2017). Therefore, the research uses the online tool "Miro" to digitalise and cluster all gathered data.

3.4. Ethical Considerations

Many people agreed on voluntary participation during this study. In order to protect their privacy, all participants signed a consent form which ensures the collection of audio data only and the information that they could leave the study at any point without mentioning a reason.

document the process and its results. Furthermore, all workshop participants signed an additional agreement about the usage of those pictures in terms of this study. Finally, every additional request was clarified verbally, including information about everybody's rights according to GDPR legislations.

3.5. Validity

All research participants who contribute to the study base on close contacts of the researcher. This can have positive as well as a negative influence on the data quality. On the one hand, due to the trusting relationship, organisational efforts like scheduling meetings in order to collect research data might be slightly easier. Furthermore, it might also help to discuss more honestly without any anxieties about an eventual abuse of sensitive information. On the other hand, the personal connection might also lead to a subconsciously informal conversation, which tends to allow the conversation to wander away from the frames of the study.

Furthermore, all teachers involved in the study are not older than 30, except for one interviewee. None of them has worked for longer than two years as a fully employed teacher. This low average of practice might decrease the study's wealth of experience but can also increase the methods' atmosphere and outcomes, because of their less-influenced mindset from negative experiences in the past.

Moreover, every research participant works in Germany. Even every method took place there and the spoken language during the data gathering was always German.

Furthermore, all participating teachers are from the German county of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania. That is worth mentioning since regulations regarding schooling in Germany are based on county laws and differ from state to state. Overall, the validity of the study is limited due to the low diversity in terms of the participants' age and origin.

4. Results

This chapter documents all insights gathered through the research methods, explained in chapter 3. After starting with a focus group to get a first understanding of the research topic, several learnings were collected to explore feedback in a contemporary school environment.

4.1. Phase 1: Understanding

A focus group was facilitated to kick off the research. The first phase “Understanding” is conducted to explore the problem as deeply as possible, which also covers the first two phases of the Design Thinking methodology: Empathise and Define (Figure 2). The aim was to synthesise the real needs of the user (school participants) as well as defining the problem appropriately (Gray, 2014). The co-creation workshop covers two purposes: The first day aimedto investigate and define the actual problems teachers have to deal with in terms of feedback. Day two was already fading into the prototyping phase.

4.1.1. Focus Group

The focus group discussion aimed to collect basic thoughts about the terms of feedback and technology in the context of school. Furthermore, a focus group was conducted to narrow down the initial research topic and to find one kind of human interaction this study should centre around. Since schools and especially teachers interact with many different roles, as examples students, principals, parents or even other teachers, a focal point needs to be defined. Therefore, I invited four teachers out of my circle of acquaintances for the focus group session. Due to personal contacts, all focus group participants knew each other beforehand.

The group discussion took place in Rostock/Germany at the end of February and was around three hours long. All participants were teachers who finished their studies not more than two years ago at the University of Rostock. Additionally, all of them have been pasing their "Referendariat" at that moment. In Germany, it describes a mandatory phase of 1.5 years, which is comparable with a traineeship. Examined teaching students start to work by giving 12 lessons a week. During that time, they get supervised by a particular mentor.

teaching for "Sekundarstufe 1" and "Sekundarstufe 2" which means they are allowed to teach classes from 5th grades onwards and work with students who are approximately 10 to 18 years old. They all work in public schools in the federal state of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania in Germany.

Need for feedback at all

After a comprehensive introduction of the study purposes and basic ideas, the group started to discuss the need for individual feedback for students, next to their initial evaluation through grades. All participants agreed that grades are not sufficient enough, especially in terms of smaller individual tasks. Teachers need a deeper understanding of their pupils in order to know if the thought content is precise and understandable for them. Grades cannot illustrate this accession. Grades do not reflect a pupil's state of knowledge appropriately enough due to several influencing factors during the test situation. For example, sometimes pupils are too anxious to ask when they do not understand the questioning properly. Furthermore, parenting issues influence a pupil's learning deeply but can only be hardly anticipated by teachers.

Feedback from teacher to teacher

The next discussed interaction was communication between teachers. Based on their

experiences, teachers are usually extremely anxious about non-evaluating observations. Even if an agent visits their school in order to see how his learning material is used, teachers do not understand the benefit. One participant quoted an experienced colleague who describes teachers in general as "mavericks" and claimed that this kind of attitude would not change soon. One of the reasons for this attitude is the enormous amount of time teachers already spend on planning lectures. Since there is no time scheduled for any exchange, every feedback session would mean extra working hours for them.

While talking about self-evaluation, opinions diverged significantly. Some participants do not do it as far they have their mentors who give them feedback regularly. Others take notes and grade them-self after every lesson. It depends on a teacher's character and aspiration, they said.

“I started to evaluate myself. I was documenting notes on what was good and what was bad. Originally, I wanted to do it together with my mentors, but it failed due to our common lack of time.“

“I don’t evaluate myself. I trust in my mentor’s feedback.”

“It depends on the teacher’s character. I am very strict to myself.” Feedback from students to students

Students can also evaluate each other by themselves. Some focus group participants claimed that they struggle a lot with students' evaluation. Especially students with weaker

performances do not know how to do it properly because these students do not see the need for it. However, as soon as teachers let them practise it regularly, students start to enjoy and respect it as a serious part of their learning process.

Furthermore, one participant uses different material and methods from web resources and tries to adapt it due to her class. She also mentioned that technology could help to improve student-owned written feedback because many students fear that their handwriting could potentially be recognised. Even if face-to-face communication might be a skill for itself, anonymous feedback prevents bullying.

"Especially weaker students just don’t know how to give proper feedback. They don’t see the need."

"I explain to my students how to do it properly. I have a pool of different methods for it which makes it very easy for me as well as for the pupils."

Feedback from students to teachers

Based on all participants experience, many universities use online feedback surveys to evaluate their lectures. At the end of these lectures, students answer questions about specific course-related topics. By the imagination, having something similar for the courses they facilitate now, some focus group members question it because of their earlier mentioned overwhelming workload. However, another one mentioned student feedback as the most important feedback a teacher gets. She practises it similarly as the student-student-feedback. Feedback from students to their teacher breaks up the typical power structure but also requires transparency.

"I do it (gathering feedback from students) very often. It is the most important feedback for me. But I have a very pleasant, smart class."

"The school I am working in has no evaluation survey or similar to those we know from the university. It is not a topic for me at the moment. I cannot even think about it at the moment since I am too busy with lesson preparation and so on. I first need to explore it by myself."

Overall, the feedback process needs to cover a presentation of what happens to information a teacher gathers. It helps to design better and more appropriate lessons. Furthermore, all participants agreed that students need balanced feedback – from student to teacher as well as from teacher to student. Especially the low performing ones need a teacher as a person who they can see as a role model.

Feedback from parent to teacher

The focus group questioned the interaction with the pupil's parents immediately. Feedback from teacher to parent and vice versa should not be something to focus on in the study. It is neither the duty of a teacher to judge parenting nor a parent's job to evaluate proper teaching just because they went to school in the past. Parents cannot keep track of everything that happens in the classroom.

Technology access

The closing topic of the group discussion was the actual participants' technology access and usage in their classrooms. It differs from school to school. Some have only three mobile projectors located in different parts of the school building. Others have fixed projectors or even "Smartboards" in every room. Smartboards seem to be whiteboards with a fixed projector on top. Its surface recognises touches and works like a large touch screen. Even though, as far they only have access to a projector, the participants do not see a significant benefit of using such smartboard.

Even if it difficult to access, all participants have access to their school's Wi-Fi

network. Students generally do not have access to it. Some schools prohibit smartphone usage during classes at all. However, one teacher of the focus group allows smartphones as a

research tool as far as students use their private data for it. Teachers are required to design their lessons as inclusive as possible. They must not exclude pupils because of lacking technology or internet access.

"We have Wi-Fi, but it is very hidden. A dedicated teacher needs to type in the password secretly. However, I do not use it often since it is too slow to show a video. There is one room with a fixed

projector, but I am the only one who works with it. In the room for my German lessons, we only have an overhead projector."

The usage of digital devices is very diverse. Some of the participated teachers use technology only sporadically to show a video, while others use the chalkboard very rarely due to their fixed projectors. However, all participants appreciate a document camera as one of the most useful tools in a classroom. Document cameras can scan and project anything

immediately. All participants see the tablet as a device which might be the most used one in the future of schooling. Some schools they know already offer a set of tablets which can be booked by a teacher, similar to science teachers who can book sets of science tools like thermometers or microscopes.

Learnings

The lack of time is one of the most significant problems of teachers. All focus group

participants were claiming an overwhelming workload. A school environment is unique and hard to compare to office models like design agencies. Furthermore, the schedule of teachers is not flexible. It seems complicated to implement additional time slots which do not refer directly to the pupil's curriculum.

Due to this central issue, the focus group recommended focussing on the interaction inside the classroom in the future research process. Furthermore, all participants, including the facilitator, agreed on the interaction between pupils and their teachers as most attractive. Aiming towards this direction of communication allows trying to decrease the teacher's workload by shifting potential data gathering to students and technology.

"Feedback needs to happen regularly. At the same time, it should decrease the workload, and the analysis needs to be simple and visual."

Overall, the focus group's access and awareness of technology were weaker as expected. In turn, their recognition of a document camera leads to further research about its particularly high appreciation by teachers. Furthermore, even pupils’ potential lack of access to digital devices and web resources will restrict the study's exploration significantly. The study needs to find possible solutions for a better teacher feedback process without ubiquitous access to technology.

Figure 5: Image of a document camera (IPEVO, 2019)

4.1.2. Workshop

Since the focus group was the first step towards a better understanding of the overall situation as well as defining teachers' needs more precisely, a co-creation workshop helped move from the understanding phase into the prototyping phase. As described in the

methodology section, this study tries to follow a human-centred design approach. According to this, the co-creation workshop tried to empower teachers as relevant participants of the design team.

Thereupon, the workshop's participants were five teachers and three digital product designers. As this study’s researcher, I took on the role as facilitator and tried to manage everything needed, keep everybody involved as well as record any valuable conversations, thoughts and insights. The workshop was held in an office space in Berlin/Germany in the weekend of 3rd - 4th March for eight hours per day.

Figure 6: Timetable of the co-creation workshop

The workshop started with a quick introduction, a warm-up exercise to introduce the participants to each other and a short presentation by the researcher, who explained the background and purpose of the workshop.

Synthesis

To contextualize the topic of feedback in schools, the group clustered quotes of the study's current research state, including first learning from the literature review and the focus group discussion. Those quotes were assigned into four categories: pains, gains, goals and ideas. After that, the group tried to cluster the quotes which are similar or somehow connected. Then the group prioritized with sticky dots, so that all participants could see where the group

expects the focus point to be during the workshop. The voting surfaced two main topics. One was about the awareness of feedback and included quotes like:

"Digital feedback is more anonymous than oral feedback."; "Students don't see the need of feedback.";

"You need to make transparent what you have changed based on the feedback you gathered."

"Teachers never asked me for feedback so far."; "Students don't get familiar with feedback."

are two example-quotes of this cluster.

Idea generation

The next agenda point was to rephrase those quotes into so-called "How-might-we-questions". This exercise helps participants to see the clustered information as opportunities rather than as problems. Rephrasing mostly negative sentences into more open questions helps participants to focus on explorations instead of quick-fixes (Knapp et al., 2016). Because of the immense amount of questions created, another voting session helped to prioritize them.

One group's final How-might-we-questions were:

"How might we motivate students to give feedback?"

"How might we find suitable methods and questions for students?" "How might we make students feel comfortable to give feedback?"

The other group came up with:

"How might we integrate feedback into lectures small-spatially?" "How might we ritualise getting feedback?"

"How might we design methods which don't feel like a burden?"

Based on the prioritized How-might-we-questions both groups conducted

brainstorming sessions. Brainstorming is a technique to aggregate many broad ideas rather than well-defined solutions. Participants are encouraged to build on each other's notes instead of judging them (Gray, 2014). The most inspiring thoughts based on the collected