CORPORATE CARBON NEUTRALITY

A Systems Perspective on Current Conceptualizations Within the Textile & Clothing Industries in Respect of the Multilateral Climate Target to Establish a Net-Zero Economy

Maximilian Hagl Maja Sophia Wiegand

Leadership and Organisation

Degree of Master of Arts (60 credits)

with a Major in Leadership and Organisation Master Thesis: 15 credits

Spring 2020 Supervisor: Ju Liu

Title: Corporate Carbon Neutrality: A Systems Perspective on Current Conceptualizations Within the Textile & Clothing Industries in Respect of the Multilateral Climate Target to Establish a Net-Zero Economy

Authors: Max Hagl and Maja Wiegand

Main field of study: Leadership and Organisation

Type of Degree: Master of Arts (60 credits) with a Major in Leadership and Organisation Subject: Master Thesis with a focus on Leadership and Organisation for Sustainability (OL646E), 15 credits

Period: Spring 2020 Supervisor: Ju-Liu

Abstract

Purpose – The research aims to critically evaluate the impact of current corporate carbon neutrality (CCN) conceptualizations within the textile & clothing (T&C) industries from a systems perspective in respect of the multilateral climate target to establish a net-zero economy by 2050. Contemporary mistrust and seemingly varying CCN conceptualizations may result in the collapse of the entire concept or may lead to miss the intentional target of fundamental climate change mitigation at large.

Research Design – Overall, an abductive research approach was chosen, firstly, utilizing existing interdisciplinary literature of the discourses on carbon neutrality, sustainability, and the footprint concept. Secondly, a quantitative descriptive research strategy by means of an online survey was pursued to identify and discuss current industry perceptions of how CCN conceptualizations should be designed. Thereby, the focus was on the implications as well as possible inconsistencies, and contradictions regarding a climate effective net-zero economy by 2050. Thirdly, the key findings were transferred into preliminary inferences, which in the following were tested on authenticity by qualitative expert interviews. Here, representatives and practitioners from the T&C industries were asked to outline the current situation in their own words. In a final discussion, the preliminary inferences were proved most likely valid, and thus, the research is able to formalize both practical, and theoretical advice.

Originality & Value – The concept of CCN in the T&C industries has not yet been critically discussed from a systems perspective neither has an abductive research approach investigated it. Therefore, the research gives new insights on the topic and offers potential answers to solve problems the concept is currently facing.

Findings – The research found out that there is no predominant perception among decision makers within the T&C industries on how conceptualizations of CCN should be designed. Moreover, it is striking that most of the current CCN conceptualizations are most likely to fail establishing a climate effective net-zero economy by 2050. The research found indications that this is not based on lacking systemic motivation among practitioners as presumed, but rather on the lack of expertise, and the missing access to information. The absence of a valid international definition that is fully circumscribing the complexity of the concept promotes such state of affairs. Apart from that, a possible conceptual over-complexification and overburden could have led practitioners to primarily focus on medial discourses which are generally easier to understand but may elude the full ramifications of the concept.

Scientific Implications of the Research – The text points out anew that academia possesses the responsibility of steering the concept of CCN towards a systemic climate effective standardization that is globally accepted, generally intelligible, and economically attractive in order to create lasting momentum around the term and mitigate climate change at large. More in detail, the authors suggest shifting the general research focus from the assessment scope to the variety of carbon initiatives. This requires further joint discourses between scholars of natural sciences, socioeconomics, and engineering.

Practical Implications of the Research – Throughout the text, practitioners receive critical advice and certainties of how they should design their CCN conceptualizations, and thus, minimize the risk of being publicly criticized and contribute effectively to the multilateral climate goals.

Limitation – The research focuses on industry perceptions within the T&C industries and may not apply to other sectors. However, the findings could give some rudiments to adjacent consumer goods sectors of the manufacturing industry. Moreover, the research was conducted in a truly outstanding global situation affected by the COVID-19 pandemic that may have influenced the key findings of the paper to some extent.

Table of Content

1 Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background: The Momentum of Corporate Carbon Neutrality ... 1

1.2 Research Purpose and Framework ... 2

1.2.1 Problem Definition ... 2

1.2.2 Aim of the Research ... 3

1.2.3 Research Questions ... 4

1.2.4 Research Roadmap ... 4

2 Theoretical Foundation... 7

2.1 Sustainability in the Context of the T&C Industries ... 7

2.1.1 Climate Change and Future Implications ... 7

2.1.2 Anthropogenic Activity, Sustainability, and the Three Pillars of Society ... 7

2.1.3 Tracing Emissions: The Textile and Clothing Industries ... 8

2.1.3.1 Sectoral Impact, and Externalities ... 8

2.1.3.2 Global Complexity, Sectoral Power Structures, and Responsibilities... 10

2.1.4 Supranational Motion towards a Net-zero Economy... 12

2.1.4.1 National Bounds in a Society of Organizations ... 12

2.1.4.2 Intergovernmental Pathways: Collaboration for Effectiveness ... 13

2.2 The Footprint Concept ... 14

2.2.1 Corporate Carbon Footprints ... 14

2.2.2 Greenhouse Gases and GHG Equivalents ... 16

2.3 The Concept of Corporate Carbon Neutrality ... 17

2.3.1 Corporate Carbon Neutrality in Theoretical Context ... 17

2.3.1.1 Core Principle 1: The Purpose of Carbon Neutrality ... 18

2.3.1.2 Core Principle 2: The Definition of Scope ... 20

2.3.1.3 Core Principle 3: The Role of Carbon Offsets ... 22

2.3.1.4 Core Principle 4: The Role of System Thinking ... 23

2.3.1.5 Overview of the Findings ... 24

2.3.2 Corporate Carbon Neutrality in Practical Context ... 25

2.3.2.1 Categorization of Corporate Carbon Neutrality Initiatives ... 25

2.3.2.2 Enablers and Barriers of Corporate Carbon Neutrality ... 27

3 Mixed Methods Approach ... 29

3.1 Quantitative Online Survey ... 29

3.1.1 Coding Framework and Online Questionnaire ... 29

3.1.2 Sample Design ... 30

3.1.3 Conduct and Environment ... 31

3.1.4 Data and Analysis ... 31

3.1.5 Limitation and Special Occurrences ... 32

3.2 Qualitative Expert Interviews ... 32

3.2.1 Coding Framework and Semi-structured Interview Guide ... 33

3.2.2 Sample Design ... 33

3.2.3 Conduct and Environment ... 34

3.2.4 Data and Analysis ... 34

3.2.5 Limitations and Special Occurrences ... 34

3.3 Reliability and Validity ... 35

4 Primary Research ... 36

4.1 Phase (1): Online Survey on Corporate Carbon Neutrality Conceptualizations ... 36

4.1.1 Table of Results: Contemporary CCN Conceptualizations ... 36

4.1.2 Findings and Discussion ... 41

4.1.2.1 Demographics... 41

4.1.2.2 General Perception of Corporate Carbon Neutrality ... 42

4.1.2.4 Perception of different Assessment Scopes within CCN Conceptualizations ... 44

4.1.2.5 Perception of different Carbon Initiatives within CCN Conceptualizations ... 48

4.2 Phase (2): Development of Preliminary Inference ... 55

4.3 Phase (3): Interview Series to Evaluate the Inference ... 55

4.3.1 Results and Key Statements ... 55

4.3.2 Findings and Discussion ... 60

4.3.2.1 Communities of Practice seem to Increase Expertise and Influence ... 60

4.3.2.2 Strong Ties with Suppliers are Likely to Increase Trust ... 61

4.3.2.3 Trust seems to Increase Transparency and Accessibility to Information ... 61

4.3.2.4 The Level of Accessible Information and Expertise seems to Influence Decisions .. 62

4.3.2.5 Financial Barriers seem to Limit the Concept ... 62

5 Conclusion ... 64

6 Bibliography ... i

Table of Tables

Table 1: Further Discourse on Externalities of the T&C industries ... 10

Table 2: Literature Overview on Definition of Carbon Neutrality ... 19

Table 3: Literature Overview of the Frameworks for the Definition of Scope ... 21

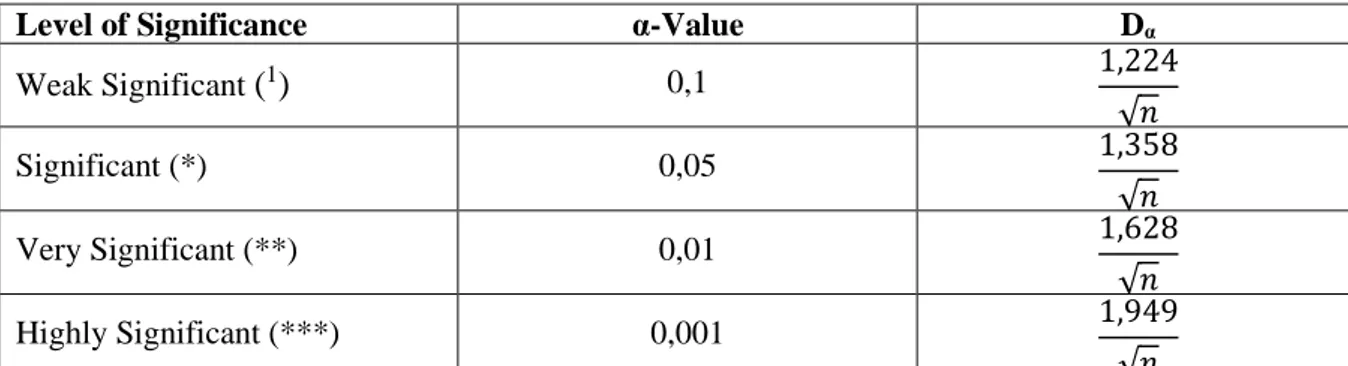

Table 4: Significance Levels Throughout the Text ... 31

Table 6: Interviewee Overview ... 34

Table 5: Table of Results: Contemporary CCN Conceptualizations among Managers within the T&C Industries ... 41

Table of Figures

Figure 1: Research Framework of this Thesis. Source: Own Illustration. ... 4Figure 2: The abductive research process. Source: Own illustration based on Kovács and Spens (2005, p.139) ... 5

Figure 3: A nested sustainable development world view. Source: (Giddings et al., 2002, p.192) ... 8

Figure 4: The apparel commodity chain from a US-centric perspective. Source:(Gereffi and Appelbaum, 1994) ... 11

Figure 5: The Relation Between Footprints of Different Entities. Source: (Hoekstra and Wiedmann, 2014, p.1114) ... 15

Figure 6: The Footprint Concept of Different Entities. Source: (Hoekstra and Wiedmann, 2014, p.1116) ... 16

Figure 7: Categorization of Corporate Initiatives leading towards CCN. Source: Own Illustration based on (Adame et al., 2018; Carbon Trust, 2006; Gössling, 2009; Kaur et al., 2015; Kelleway et al., 2017; Lal, 2008, 2010b; Lingl et al., 2010; Lovell et al., 2009; Lüdeke-Freund, 2010; Nogia et al., 2016; Nunes et al., 2019; Schäfer, 2019; Schäpke and Rauschmayer, 2012; UNEP, 2009) ... 25

Figure 8: Carbon Neutrality Conceptualization and its Key-components within this Thesis. Source: Own Illustration ... 29

Figure 9: Data Visualization of Question 6 (Q6): Perceived Inconsistency among CCN Conceptualizations ... 42

Figure 10: Data Visualization of Question 7 (Q7): Intrinsic Motivation for CCN ... 44

Figure 11: Data Visualization of Question 9 (Q9): Perception of Type of Emissions in the Assessment Scope of CCN ... 45

Figure 12: Data Visualization of Question 10 (Q10): Perception of Emission Sources in the Assessment Scope of CCN ... 47

Figure 13: Data Visualization of Question 11 (Q11): Prevention Vs. Offsets ... 49

Figure 14: Data Visualization of Question 12 (Q12): Internal Vs. External Initiatives ... 50

Figure 15: Data Visualization of Question 13 (Q13): Onset of Effect ... 51

Figure 16: Data Visualization of Question 14-20 (Q14 - Q20): The Levels of Affirmation among Different CCN Initiatives ... 52

Figure 17: Conceptual Process of Climate Effective CCN based on Marketing’s ‘Four Stage Buying Funnel’. Source: Own Illustration Based on the Findings of this Research. Leaned on: (Jansen and Schuster, 2011, p.3) ... 64

1

1 Introduction

The textile and clothing (T&C) industries are ranked among the world's biggest polluters. From current perspectives, the sector is responsible for 8-10% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and thus, subject to great criticism. To counteract, many companies in the T&C industries have made voluntary carbon neutrality declarations to mitigate climate change and contribute to a net-zero economy by 2050. As corporate carbon neutrality (CCN) is an under-investigated but highly technical sustainability approach, different conceptualizations are being discussed on how to reach net-zero, whereby the effectiveness and general legitimacy of these measures are not known with certainty. To ensure its impact, CCN must be understood as a fundamental systemic concept introducing disruptive change, instead of a philanthropic duty consisting of easy payments. Nevertheless, this requires systemic motivation, monetary resources, certain technical expertise, and access to information. However, particularly the latter two seem not to be ensured throughout the economic landscape of the T&C industries as this research will demonstrate.

1.1 Background: The Momentum of Corporate Carbon Neutrality

Three decades of highly criticized governmental attempts to find a concrete global agreement to reduce GHG emissions effectively have turned global warming into a heavily debated issue that finally entered corporate boardrooms (Kolk and Pinkse, 2009; Pinske and Busch, 2013) and what now appears as the concept of CCN - presumably driven by Bouchery’s five sustainable pressures: Natural resources depletion, Regulations, Customer awareness, Company image, and Employees’ motivation (Bouchery, 2013).

In 2006 the American Oxford Dictionary declared “carbon-neutral” as the word of the year (Oxford Languages, 2006). Since then, an increase in corporate communications on the topic has been remarkable. A CEO study in 2019 found that 44 percent 'agree' or 'strongly agree' that a “net-zero future is on the horizon for [their] company in the next 10 years” (United Nations Global Compact and Accenture, 2019). The same study also concluded that 42 percent 'agree' or 'strongly agree' that “decarbonization strategies are deployed in operations across the supply chain” (United Nations Global Compact and Accenture, 2019).

The momentum of CCN in practice is expressed by many businesses which claim to be carbon neutral or make statements on reaching zero-emissions targets in the future in order to show their commitment to mitigate climate change (Gillenwater et al., 2019; Pinkse and Busch, 2013). Companies are increasingly aware that global regulations of carbon emissions is imminent (Matthews et al., 2008). Especially, the retail sector shows an increase of carbon neutrality labels on products (Pinske and Busch, 2013).

Practical examples of this are CCN announcements by big corporations like Gucci, Patagonia, H&M, and Nike. For instance, Gucci’s sustainability strategy has been operated since 2015 and includes the reduction of 50% of their supply chain emissions by 2025 through sustainable manufacturing, sourcing, and offsetting (Conlon, 2019). Moreover, Patagonia aims to become carbon-neutral entirely by 2025 - primarily based on supply chain improvements utilizing energy efficiency and disruptive innovation, but also, biotic sequestration projects to offset unavoidable emissions (Kammen et al., 2019). In 2016, the H&M Group published its goal to become climate positive by 2040. “This means reducing more greenhouse gas emissions than what our whole value chain emits” (H&M Group, 2019). As a part of Nike’s “move to zero” program, they set targets to reduce scope 1 and 2 emissions by 65% and scope 3 emissions by 30% (Nike, 2020).

2

1.2 Research Purpose and Framework

Although CCN initiatives seem to be promising for companies to reduce GHG emissions, their effectiveness as a replacement for government regulation is still subject to many uncertainties (Pinske and Busch, 2013). This chapter sets out the difficulties regarding CCN from different perspectives and describes the research framework of this thesis.

1.2.1 Problem Definition

This section outlines the different understanding of various stakeholders on CCN. Depending on the company and the industry, carbon neutrality seems to mean many different things - possibly due to the very little scientific research around the term, which lacks a generally applicable circumscriptive definition. Although the concept is gaining momentum throughout the industrial landscape, CCN has to deal with the loss of authenticity in the media and the mistrust of society, which limits the full potential of the approach. This section summarizes the contemporary discussion among industry representatives, governments, scholars, and the public on CCN.

Industry

At first, carbon neutrality seems to be the best thing a brand can do to mitigate climate change (Bauck, 2019). However, it isn’t as straightforward as many companies make it sound (Bauck, 2019). The main challenges in the industry lie in the variety of approaches to achieve carbon neutrality, the missing unity of approaches between industry participants, insufficient honesty of firms, and lacking transparency in assessing and reporting CCN.

Pinkse and Busch (2013) claim that it is unclear what it means when a company sets carbon norms. To achieve carbon neutrality, companies can use carbon prevention and carbon offsetting mechanisms. The possible measures are very diverse and can take the form of changing to renewable energies, using innovative technology to achieve efficiency within business processes, investing in projects that take carbon from the atmosphere, starting internal offsetting projects, planting trees, and many more. The different forms of approaching carbon neutrality and the absence of a regulatory framework, therefore, lead to firms struggling with positioning themselves in the climate debate and choosing the “right” neutralization strategy (Pinske and Busch, 2013).

Furthermore, the extent to which companies take responsibility for their actions differs significantly. CCN can be based on different scopes, that either take a narrower or broader perspective on the company’s environmental impact on its non-human stakeholders (Burtis and Watt, 2008; Esty and Simmons, 2011; Garcia, 2009). Most corporates only take their operations and value chains into account, whereas a few environmentally conscious companies focus on their entire supply chain, including their supplier’s suppliers (Esty and Simmons, 2011). Academia

Academic literature has examined a variety of issues and innovations related to sustainability in the T&C industries (Shen et al., 2017). However, there is a lack of integrative scientific definitions of carbon neutrality. The existence of only a few scientific researches around the term creates the lack of a general valid circumscribing definition. A theoretical foundation of the concept is necessary because “world leaders need tools that enable them to make decisions in the midst of so many unknowns” (Moore et al., 2012, p.3) The whole concept requires more attention and debate from varying participants in the industry. Boström and Micheletti (2016) state that research suggests better communication from governments, businesses, media, educational institutions, activists, and others to transition towards a climate effective net-zero T&C industries. The whole concept requires more attention and debate from varying

3

participants in the industry. “Accumulated research also suggests that better information and communication from governments, activists, businesses, educational institutions, the media, and others are necessary” to ensure the transition towards a climate effective net-zero T&C industries (Boström and Micheletti, 2016, p.368).

Governments

Supranational policies for the regulation of assessment scopes and timeframes and valid initiatives for carbon neutrality are insufficient. Many cap-and-trade schemes have conceptual deficiencies in the determination of the cap, the definition of allocation and the implementation of correction mechanisms (O’Riordan, 2007). Those systems are vulnerable to counterfeiting and can be abused by industry lobbying for clandestine deals, unexpected changes in business tolerance and the fundamental unwillingness of the parties involved to introduce strict and progressive regulatory systems (O’Riordan, 2007). As a result, “a major challenge remains in companies setting reduction targets for their supply-chain footprint” (Hoekstra and Wiedmann, 2014, p.1115).

Public and Consumers

The concept of CCN generally suffers from mistrust and truthfulness, especially since many high-profile greenwashing cases have become known in 2008 (Carbon Clear, 2011). People are skeptical that carbon neutrality norms are really being implemented (Smithers, 2011). Firms that have published their CCN initiatives have been accused of misleading their customers (Pinske and Busch, 2013). Therefore, adopting corporate carbon norms seems to be risky for organizations (Pinske and Busch, 2013).

1.2.2 Aim of the Research

This paper aims to create transparency regarding the current understandings of the CCN concept. Consequently, we will critically evaluate and discuss the impact of current CCN conceptualizations and various strategies to reach a legitimate CCN status from a systems perspective. Following, the purpose of this text is to identify coherences, inconsistencies, and contradictions among the views of practitioners based on existing literature and the perceptions of industrial stakeholders. Overall, the authors hope to contribute via this study towards the coherence of the CCN concept; we presume that significantly varying CCN strategies may eventually result in the collapse of the entire concept. We strongly believe that the CCN concept is of great interest to both scholars and practitioners because it can be viewed as an operationalization for businesses to implement the much-discussed concept of sustainable development in a capitalistic market structure. From a practical point of view, the paper likes to ensure that the industry keeps track of reaching the multilateral climate targets, particularly the goal of establishing a net-zero economy by 2050. Moreover, the paper likes to give advice to the potential international standard on carbon neutrality ISO/WD 14068 which is currently under development. Thus, transparency and trust could be restored, and the full potential of the concept can be unlocked to mitigate climate change at large.

4 1.2.3 Research Questions

Main Research Question (RQ):

• RQ: How do current conceptualizations of CCN within the T&C industries contribute to the multilateral motion towards a climate effective net-zero economy by 2050?

Sub Research Questions (SRQs):

• SQR1: What are the current conceptualizations of CCN among managers within the T&C industries?

• SRQ2: What are the implications of current CCN conceptualizations within the T&C industries?

To better understand the coherence between the research questions Figure 1 has been added. Here, the infographic outlines the connection of managerial input to potential organizational CCN conceptualizations. SRQ1 focuses on this relation and creates the base of SRQ2 which investigates the implications of such conceptualizations. Thus, the research has foundational findings to critically evaluate those in the context of the multilateral goal to establish a climate effective net-zero economy by 2050 (RQ) which in total should be the intentional aspiration for systems-oriented managers.

Figure 1: Research Framework of this Thesis. Source: Own Illustration.

1.2.4 Research Roadmap

In sum, the authors decided on developing the theory in primarily cross-sectional conduct methods following an abductive research approach utilizing mixed-methods in four-phase research framework (as illustrated in Figure 2). Here, primary data is gathered by a descriptive quantitative method at the beginning of the research. Later in the process, the abductively generated inferences will be tested with qualitative expert interviews. As a result, the authors hope to effectively contribute to the scientific discourse on CCN by means of valid theoretical inferences and give practical advice (normative character) for industrial stakeholders.

As mentioned above, based on the aim of this thesis, an abductive research approach was chosen. This scientific way of theory development allows for a reciprocal interplay between theory and empirical observations (Saunders et al., 2019; Suddaby, 2006). In contrast, pure induction or deduction operates in a practically difficult (nearly impossible) direct way, building theory from data (induction), or respectively, data from theory (deduction) (Saunders et al., 2019). The authors are convinced that these theoretical solo approaches (deduction & induction) would not be capable of adequately answering the research questions while keeping

5

the complexity of their domain. By contrast, abductive research can be seen as a rather flexible approach “to knowledge production that occupies the middle ground between induction and deduction”(Järvensivu and Törnroos, 2010, p. 102). Moreover, the scholars Järvensivu and Törnroos describe “abductive research [...] as a mix of inductive, abductive, and deductive sub-processes“ (Järvensivu and Törnroos, 2010, p. 103). Additionally, Saunders et al. state: “deduction and induction complement abduction as logics for testing plausible theories” (2019, p.155). As a consequence, abductive research cannot be simply described as abduction solely - abductive research requires more specification going into detail to circumscribe the process adequately. On the other hand, due to its adaptable nature, abduction applies to a variety of different research philosophies - particularly to critical realism and moderate constructionism (Järvensivu and Törnroos, 2010). whereby the latter is representing the sentiment of the authors. Additionally, the abductive approach is perfectly suiting for controversial and vague existing theory (Menzies, 1996) worth developing, modifying, or replacing – such as the concept of CCN. Moreover, the abductive research approach is frequently viewed as the go-to research strategy for business, management, and socio-economic matter and thus, (Järvensivu and Törnroos, 2010; Saunders et al., 2019) confirms the choice of the authors. Lastly, abductive research has not been chosen by many scholars writing on CCN so far. For that reason alone, abduction is worth investigating with since the approach “leads to new insight about existing phenomena by examining these from a new perspective” (Kovács and Spens, 2005, p.138). In practice, abduction starts with a surprising fact revealed due to empirical observations of the first order (Phase (1a)), followed by open theory matching and pre-discussion of plausible

causes for a better understanding of how it came about (Phase (1b)). Secondly, hypothetical

assumptions are suggested (Phase (2)) but must be checked by an inference assessment method (Phase (3)) to ensure testable conclusions (Phase (4)) describing the most likely cause (Menzies, 1996; Saunders et al., 2019). Thus, a process of abduction can form a valid explanatory hypothesis, and therefore, creates new perspectives on our empirical world (Suddaby, 2006). However, if the penultimate step (Phase (3)) gets disregarded, the risk for the false assumption is increased to its maximum, since other despised reasons may be the real cause of the observed surprising fact (Phase (1a)) which were not pre-discussed during the open theory matching

phase (Phase (1b)) (Menzies, 1996).

In short, abduction is a dyadic process that generates and tests theory (Järvensivu and Törnroos, 2010; Saunders et al., 2019) or according to Menzies, “abduction is typically defined as inference to the best explanation” (1996, p.311).

6

Writing in the context of this thesis, the abductive research approach (as illustrated in Figure 2) starts at Phase (0): gathering existing theoretical knowledge based on academic publications in the field of generic carbon neutrality, the global carbon cycle, and the footprint concept to create a scientific understanding what CCN is about throughout existing literature (see section 2 Theoretical Foundation).

Phase (1a): In the next step of the abductive research process a descriptive quantitative

sub-process was chosen utilizing an online survey to expose current (cross-sectional) conceptualizations of CCN within the T&C industries (SRQ1) - Here (and throughout the whole thesis), CCN conceptualizations have been coded as the overarching frameworks for individual/organizational opinions on the most appropriate time frame, assessment scope, and initiatives (carbon offsetting and prevention) to reach carbon neutrality (as illustrated in Figure 2). After the data will have been collected, an appending scientific analysis will reveal possible coherences, inconsistencies, and contradictions (the so-called surprising facts) among the CCN conceptualizations of industrial decision makers (managers). (4.1 Phase (1): Online Survey) Phase (1b): In the following dyadic theory matching phase, the authors anticipate those

conceptualizations into CCN implications (1b1) through a theoretical approach backed by

another scholar’s opinion (SRQ2) and voluntary comments gathered qualitatively in the questionair. By that, the focus lies on more systemic consequences with respect to the multilateral climate targets of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Moreover, open theory matching is used in this phase to process patterns among variables of the survey (1b2) into presumable rules and explanations of the surprising fact(s).

Phase (2): A combination of those derivations and implications form the basis of the abductive inference (hypothesis, propositions, new theory suggestions, or modification) which is formalized in this phase and relates to the main research question of this text.

Phase (3): As previously discussed, abductive research requires an inference assessment method to obtain validity under reserve. For this reason, expert interviews with industry representatives have been organized for a qualitative assessment of the abductive inference. Phase (4): In the conclusion (5 Conclusion) the authors illustrate the key findings of this abductive research process and give practical advice to both concept developers (like scholars and policymakers) and practitioners of CCN.

7

2 Theoretical Foundation

This section builds the fundamental base for the following research by explaining the role of sustainability and carbon neutrality in the T&C industries. It explains the carbon footprint concept, sets out the scientific discourse about carbon neutrality in academic literature and gives an overview of possible carbon neutrality initiatives that can lead to reaching the multilateral targets of a net-zero economy by 2050.

2.1 Sustainability in the Context of the T&C Industries

2.1.1 Climate Change and Future Implications

In recent decades, climate change has emerged as the single-most serious threat to humanity (IPCC, 2007). For many years, scientists predicted that global temperatures are rising. In 2018, the IPCC published a high warning report stating that global warming emissions are accelerating and that our planet is on the edge of a series of escalating climate events affecting our global biosphere at large. Already, ecosystems are significantly out of balance, and the current climate crisis poses the potential to endanger all living species, including humankind, on our planet (IPCC, 2018). “The current changes in our planet's climate are redrawing the world and magnifying the risks for instability in all forms” (European Commission, 2018, p.2) According to the IPCC (2018) this is primarily attributable to an increase in global temperatures of around 1°C above pre-industrial levels. Nevertheless, more consequences caused by climate change are pending. Should the average global temperature continue to rise till more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, a series of climate disasters will most likely occur depleting the earth's ecosystems severely and irretrievably without neglecting the pending presence of socio-economic consequences – which will be “far lengthier and far more disruptive than what we currently see with the coronavirus” (Pinner et al., 2020, p.3).

2.1.2 Anthropogenic Activity, Sustainability, and the Three Pillars of Society

From today’s perspective, the dominant factor of global warming is the increasing concentration of atmospheric GHGs (IPCC, 2007). Most of this GHGs occur naturally around our planet but have raised their concentration significantly in the last 250 years – thus, the global carbon cycle become unbalanced. Predominantly because of anthropogenic activities (Brancalion et al., 2019; IPCC, 2007, 2018; OECD/IEA, 2016; Poore and Nemecek, 2018; Tian et al., 2016; UNEP, 2017; UNFCCC, 1998; WCED, 1987).

To bring the natural system in its equilibrium state again, the concept of sustainable development has gained necessity. Initially developed in the 18th century (von Carlowitz, 1713),

the ideology became decisively defined in the year 1987 as part of the ‘Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future’ which is commonly known as the Brundtland report, introducing that “sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (WCED, 1987).

Since then, mitigation initiatives to reduce or even stop human-caused GHG emissions have been ranked high in global agendas (Jackson et al., 2016). Notwithstanding, current anthropogenic activity still adds up an additional amount of ~52,5 Gt CO2eq per year to the atmosphere (Poore and Nemecek, 2018) and thus, continues to contribute significantly to the warming of our planet (Allen et al., 2009; IPCC, 2013).

To approach effective climate change mitigation sustainable development must take place systemically on a global scale where all three pillars of society (businesses, civil societies, and governments) pull together (Labuschagne and Brent, 2005; Maia et al., 2019; Wartick and

8

Wood, 1998). Additionally, it seems essential that all those players obtain a holistic view on the world, where anthropogenic activity, our society, and also the economy are fully integrative parts of the environment (as illustrated in Figure 3), and where bounds are blurred and shifting (Giddings et al., 2002). For a better understanding, a nested model has been created representing the co-dependency of society, economy, and the environment. Hereby people live in a society and create the intangible economy. The economic system shapes society and society influences the environment. In contrast to the economy, the environment is non-negotiable and tangible. Humankind has no choice to opt-out to living in this physical world that determines actions and possibilities.

Figure 3: A Nested Sustainable Development World View. Source: (Giddings et al., 2002, p.192)

Considering that more than half (~52%) of human-caused GHG emissions are directly attributable to for-profit business activity (Hertwich and Peters, 2009; Ivanova et al., 2016), and most global monetary resources are allocated to private corporations (Porter, 2013), the economy possesses certain responsibility for taking proactive climate institutionalizations because current economic pathways are clearly insufficient to warrant intergenerational equity (Hoekstra and Wiedmann, 2014). In fact, “with business as usual, all footprints are expected to further increase during the coming few decades, rather than decrease toward sustainable levels“ (Ercin and Hoekstra, 2014; Hoekstra and Wiedmann, 2014, p.1115; Moore et al., 2012; Unep, 2012).

In sum, climate change has moved from an environmental issue to a societal problem that influences all three pillars (Corbett, 2009). There is a crucial “need for an effective and progressive response to the urgent threat of climate change based on the best available scientific knowledge” (UNFCCC, 2015, 2016). Consequently, this demands action from the sides of the economy and its organizational entities. Additionally, the pressure on for-profit businesses to re-evaluate their role in the context of climate change arises significantly since the civil awareness of climate change increases involving economic risk (Middleton and Arora, 2007). Thus, there are both organizational and systemic reasons for true carbon initiatives fighting climate change.

2.1.3 Tracing Emissions: The Textile and Clothing Industries

2.1.3.1 Sectoral Impact, and Externalities

Effective climate change mitigation in a limited time frame requests knowledge about what the main causes are. Hence, relatively large resources have been spent to investigate in sectorial footprint analyses. Thereby, research found out that 65% - 72% of global GHGs get emitted by household purchases (indirectly and directly) (Hertwich and Peters, 2009; Ivanova et al., 2016). Moreover, 23% - 35% of all GHG emissions are embodied in physical commercial goods

9

passed down from industry to final consumers (Davis et al., 2011; Hertwich and Wood, 2018). This draws attention to the manufacturing industries. Especially to those where the products are non-durable but high in resource consumption, labor intensity or supply chain complexity. In that respect, the T&C industries have emerged as one of the main protagonists (Boström and Micheletti, 2016). According to Eileen Fisher and EcoWatch, global fashion is the second dirtiest business sector after big oil (Sweeny, 2015). And indeed, “the process of turning raw materials into finished garments has significant negative environmental and social implications, including air and water pollution and exploitation of human resources [...]” (Shen et al., 2017) – cf. Table 1Table 1. In fact, textiles emit the highest GHG concentration per unit of material (based on polyester and cotton), next to aluminum (Kissinger et al., 2013).

This circumstance increases in weight due to the fact that garments generally get disposed of and replaced after being used less than ten times (Birtwistle and Moore, 2007). Over the last decades, “textiles and clothing have become consumables rather than durables”(Bocken et al., 2018, p.1), and thus, impact the global carbon budget at large (Boström and Micheletti, 2016). Research has shown that this is mainly provoked by the constant change in trends and thereon adapted product portfolios of the apparel industry (Bhardwaj and Fairhurst, 2010). So-called fast fashion brands have been able to establish certain consumer buying habits (Mcneill and Moore, 2015) influencing the whole T&C industries, and thus, our climate at large.

According to scientific projections from 2009, clothing alone caused 2.8% - 3.5% of the anthropogenic carbon footprint (Hertwich and Peters, 2009; Ivanova et al., 2016). Nowadays, the clothing and textile industry is responsible for 8-10% of the global GHG emissions (UN Alliance for Sustainable Fashion, n.d.). Considering that more than six million tons of clothing annually get consumed in the European Union alone, the scale of 195 million tons of CO2

emissions becomes more tangible (Gray, 2017). Moreover, the measures are illustrated quite nicely by comparing them to other well-known emission sources. For example, the production of textiles and garments alone caused in 2015 worldwide more than 1.2 billion tons of CO2

equivalent which are “more than those of all international flights and maritime shipping combined” (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017, p.20; IEA, 2016).

Thus, “textiles and clothing now play a key role in the global public discourse on climate change” (Boström and Micheletti, 2016, p.367). According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, “if the industry continues on its current path, by 2050, it could use more than 26% of the carbon budget associated with a 2°C pathway [...] the negative impacts of the industry will be potentially catastrophic” (2017, p.21).

10

Table 1: Further Discourse on Externalities of the T&C industries

2.1.3.2 Global Complexity, Sectoral Power Structures, and Responsibilities

Given its size and global reach, current environmental and social implications of the T&C industries are significant. They require proactive initiatives to holistically mitigate climate change (UN Alliance for Sustainable Fashion, n.d.). However, “scholars stress that the problem areas in globalized textile and clothing productions are highly complex” (Boström and Micheletti, 2016, p.367). This is possibly attributable to the industry’s manifold nature, international ramification, socio-economic importance, and solidified power structures.

The Complexity of the T&C Industries

Over the last decades, the (T&C) industries have experienced publicly noticed global expansions (ILO, 2014). Disruptive change has reshaped sectorial structures and attracted civil attention. Nowadays, the T&C industries can be generally characterized by geographically dispersed production units and rapid market-driven adaptations (ILO, n.d.).

The industries include a wide variety of value-generating activities ranging from the processing of natural or synthetic fibers into yarns and fabrics to the manufacturing of finished products such as casual garments, high fashion, sportswear, work clothes, or even shoes (European Commission, n.d.). Therefore, a large number of highly specialized production steps are required (ILO, 2014). Consequently, the clothing and textile industries developed into a highly complex commodity chain where several actors of different sizes in geographically distributed locations are involved (as illustrated in Figure 4). Thus, logistics and distribution are of great importance, too, connecting the globally allocated production sites and final consumers (Macfarlane, 1994, 1995) within a limited time frame (ILO, 2014). In recent times firms (solely) focusing on the recirculation of existing products find more and more general approval and increase on weight within the sector (e.g. cloth repairs and secondary markets) (Galloway, 2020).

The value system of the textile and T&C industries causes a significant environmental footprint due to intensive resourcing, energy use and waste management (Manshoven et al., 2019). It is facing sustainability challenges in the fields of (1) non-recoverable materials and blends, (2) water usage, (3) hazardous chemical use, and (4) human rights (Resta et al., 2016). For the supply of natural fibers, like cotton and wool, large areas of agricultural land is needed, which requires big amounts of water, energy and chemicals to enable the growth (Manshoven et al., 2019). The manufacturing of fibers is based on fossil fuels and uses chemicals that have a significant environmental impact on local water bodies (Manshoven et al., 2019). Moreover, the geographic dispersion leads to greenhouse gas emissions due to transportation of goods and the packaging of those (Manshoven et al., 2019). The usage of clothing also requires water and energy resources for washing and drying which releases chemicals and micro-plastics into rivers and oceans (Manshoven et al., 2019). The clothing and textile industry are often criticized for poor working conditions and underpaid employees. Especially the collapse of the Rana Plaza factory in April 2013 in Dhaka, Bangladesh, shook the world and raised the question of how to combine economic profitability and social and environmental performance in the future (Martin and Economy, 2013).

11

Figure 4: The Apparel Commodity Chain from a US-centric Perspective. Source:(Gereffi and Appelbaum, 1994)

As a result, the clothing and textile industries are very labor-intensive, whereby the majority of employees (predominantly women) are located in low-income countries (UN Alliance for Sustainable Fashion, n.d.). In 2017, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation states that the T&C industries alone employed more than 300 million people along its value system (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017). Consequently, certain regions are seemingly dependent on residential T&C firms, especially on large ones (as outlined below), based on their function as primary employer and taxpayer.

Here, the latter is increasingly gaining in relevance due to the fact that the T&C industries have approximately doubled its economic growth within the last 15 years (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017). The European Union alone was generating a turnover of 178 billion euros in 2018 (EURATEX, n.d.). This development has been driven by a globally growing middle-class and a significant increase in per capita sales (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017) due to emerging markets, particularly in Asia and Africa (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017). But also, to the ‘fast fashion’ movement which incorporates quick turnarounds of collections generally proceeding more than five times a year. Combined with very low prices and a decreasing sense of quality, the model boosts consumption, and thus, overall profits but also resource depletion and GHG emissions (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017).

The Distribution of Power and Responsibilities within the T&C Industries

As previously introduced, the T&C industries have moved from a localized, cluster-based system to a form of value system that is more geographically dispersed. Within these global value systems, organizations control and influence each other (Ponte and Sturgeon, 2014). Thus, the power of suppliers and buyers within multinational supply chains impacts the industry and its carbon footprint at large (Ponte and Sturgeon, 2014). According to Hoejmose et al., particularly the power of buyers can influence suppliers and sub-suppliers to operate in a responsible manner (2013). However, this depends on the bargaining position of buyers and the power structure between buyers and suppliers. If buyers hold weak bargaining powers, it might be challenging to control suppliers’ practices (Pedersen and Andersen, 2006).

Interestingly, power in the supply chain of the T&C industries seems directly related to organizational size (ILO, 2014). Despite the fact, that we live in a world where large

12

organizations are a key phenomenon of our time (Perrow, 1991) the majority of companies within the textile and clothing industries employ fewer than 50 employees (European Commission, n.d.). Notwithstanding, these SE’s (small enterprises) account for 90% of the workforce while producing almost 60% of the added value (European Commission, n.d.). However, most of the interorganizational power within the T&C value system is mainly owned by larger enterprises with more than 250 employees each - primarily functioning as multinational contractors. “The sector is shaped predominantly by large companies that decide what is produced, where and by whom, with production moved quickly from one country or region to another“ (ILO, 2014, p.2). Also, Maloni and Benton confirm that those firms are critical in determinations regarding the supply chain of clothes (Maloni and Benton, 1999), and thus, also their implications. Moreover, large enterprises/multinationals can drastically influence politics (Perrow, 1991) primarily based on their socio-economic forces (e.g. labor, and tax) and sector-specific knowledge that administrative entities depend on.

In the context of sustainability and climate change mitigation, large and transnational enterprises are increasingly viewed as the main protagonists and particularly addressed within the United Nations SDG’s under the target 12.6 (UN, 2015) to demonstrate climate leadership. But also, from an organizational perspective, large firms get under pressure “to protect their brands [from damage caused by irresponsible conventions] even if it means assuming responsibilities for the practices of their suppliers” (Amaeshi et al., 2008, p.223).

The social interconnection and power of multinational corporations over suppliers is a critical factor for defining a corporate’s responsibility (Chen, 2018). From a social connection perspective, corporate social responsibility is holding corporations responsible for their actions but also for actions by others with whom they are socially connected (Schrempf, 2012). Amaeshi et al. (2008) state that there is a common belief that the more powerful party in a firm-supplier relationship has the responsibility to exercise a certain moral influence on the weaker party. However, they argue that “the responsible use of power applies to both the firm and the supplier given their relative power positions in the market” (Amaeshi et al., 2008, p.229). Moreover, they suggest that this influence should be limited to the interaction of two firms and their immediate suppliers which will cause a ripple effect and influence the whole supply (Amaeshi et al., 2008).

2.1.4 Supranational Motion towards a Net-zero Economy

2.1.4.1 National Bounds in a Society of Organizations

In the last hundred years, we have become a “society of organizations” (Perrow, 1991) where institutions took over activities that had been carried out by relatively autonomous and mostly informal groups (e.g. families, neighborhoods) in the past (Perrow, 1991). Throughout the years, profit organizations have emerged, particularly in the capitalistic regions of the world, as the most thriving force creating economic structures we see today (Perrow, 1991; Tolbert and Hall, 2009). In this respect, some scholars may argue, that particularly businesses are primarily accountable for creating wealth and driving progress within society (Porter, 2013; Tolbert and Hall, 2009). However, at the same time businesses are responsible for causing great harm – as inequality, pollution, layoffs/emission, industrial accidents, and other consequences amply demonstrate – while taking great effect on global warming (Tolbert and Hall, 2009). As previously discussed, the T&C industries are no exception. According to Porter, “the conventional wisdom in economics [has been] if business pollutes, it makes more money than if it tried to reduce that pollution [because] reducing pollution is expensive, therefore businesses don't want to do it” (Porter, 2013). Even if more and more business firms recognize that this assumption is simply wrong and shared values rather tend to offer economic opportunities

13

(Porter, 2013), the bias still seems to be anchored throughout the economic landscape. Consequently, to limit or even stop the implications of disruptive industries, legislative regulations and principles are of great importance. However, national policymakers are bound to their domestic borders, whereas contemporary economic structures are often highly internationalized and globally allocated. This allows mainly large transnational enterprises to play countries off against each other and stand above possible climate-related restrictions (Perrow, 1991; Tolbert and Hall, 2009). In addition, such business organizations often shape political landscapes through their crucial role as employers, taxpayers, and advisories (Tolbert and Hall, 2009). Someplace, their enormous influence enables them even to suppress traditional nation-states, especially in weaker parts of the world (Tolbert and Hall, 2009).

Consequently, effective corporate emission norms on a national basis are difficult to establish. They can be possibly bypassed by multinational organizations which would have the power to influence the industry at large effectively.

2.1.4.2 Intergovernmental Pathways: Collaboration for Effectiveness

For effective climate change mitigation, multilateral collaborations are unavoidable because atmospheric GHG concentrations get equally distributed on a global scale, and national initiatives are holistically not capable of inhibiting the circumvention of transnational business corporations. Confederations of states (e.g. the European Union) or other intergovernmental umbrella organizations (e.g. the United Nations) are of great importance turning soft laws and domestic agendas into supranational regulations in order to decrease anthropogenic GHG emissions effectively. However, the first important steps here are to commit unified action and to formalize generally accepted climate/emission targets capable of mitigating global warming. The Paris Agreement

In 2015, under the so-called Paris Agreement, nearly 200 nations committed to cut their GHG emissions significantly (UNFCCC, 2015). This multilateral compact administered by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is widely seen as a milestone in young sustainability history. Here, for the first time, the supranational discourse adopted the approach of net-zero emissions (which should take into effect by latest 2100) into commission as Article 4 demonstrates: All “parties aim [...] to achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of GHGs in the second half of this century” (UNFCCC, 2015, p.4) in order to achieve the long-term temperature goal (Article 2) of “holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1,5°C above pre-industrial levels” (UNFCCC, 2015, p.3). Generally accepted, those aims also retained after the second addendum and are presumably nowadays the basis of many carbon norms throughout our global economic landscape. However, the Paris Agreement failed to establish a commonly agreed action-plan for all industries. This decision has been postponed whereby all participants held on to submit their suggestions beforehand the next congress. Moreover, the Paris Agreement had to face many criticisms of sides of both media (Mooney, 2016; Watts, 2012) and academic literature (Rogelj et al., 2016; Victor et al., 2017) outlining insufficiency in the matter of time.

The IPCC Special Report

In 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the UN body for assessing the science base of global warming, published a special report to support supranational political initiatives. Here, the main subject of the investigation has been on the consequences of global warming by 1,5°C above pre-industrial levels. Also, the required pathways and global responses to react in order to keep global warming emissions under a 1,5°C ceiling have been critically

14

evaluated (IPCC, 2018). Moreover, the focus was based on the global economy, socio-technical, and socio-ecological systems (IPCC, 2018).

As a result, the initial collaboration of the first three Working Groups (I, II, and III) found out, with business as usual, global warming will already reach 1,5°C between 2030 and 2050 (IPCC, 2018). Additionally, the IPCC warned of much worse to come, in the form of, e.g. heavy rainfalls, rising sea levels, hot extremes, or droughts, if we exceed 1,5°C (IPCC, 2018).

To avoid this from happening the IPCC (2018) implicates that global warming emission gases have to be cut by 45 percent (from 2010 levels) until 2030. Furthermore, global society must cut emissions to net-zero by 2050 (IPCC, 2018). This requires a significant decline in burning fossil combustibles, an increase in energy efficiency, the use of innovative technology, and the implementation of socio-economic changes. The longer it takes to reduce GHG emissions to zero, the greater the impact and the likelihood of exceeding 1.5°C (IPCC, 2018).

The European Strategic Long-term Vision and Green Deal

In late 2018, the European Commission launched a long-term strategic vision introducing how Europe can lead global motion towards a net-zero economy (European Commission, 2018, 2019a). According to Miguel Arias Cañete (European commissioner for climate action and energy), “going climate-neutral is necessary, possible and in Europe’s interest” (European Commission, 2019a). Thereby, the aim is to decouple economic growth from resource use and submit the long-term strategy to the UN’s Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) as requested under the Paris Agreement (European Commission, 2018, 2019a). According to the European Commission, Europe wants to become the first climate-neutral continent by 2050, “boosting the economy, improving people's health and quality of life, caring for nature, and leaving no one behind” (European Commission, 2019b, 2019c). Therefore, the very important European Green Deal was released in 2019. It is “a roadmap for making the EU's economy sustainable by turning climate and environmental challenges into opportunities across all policy areas and making the transition just and inclusive for all” (European Commission, 2019b, 2019c). Hereby, it covers all sectors of the economy with a particular focus on major participants such as the textile and clothing industries (European Commission, 2019b, 2019c).

2.2 The Footprint Concept

At this point, the equilibrium of a global carbon cycle that maintained the harmony between the release and uptake of CO2 (and other natural GHG) is now out of balance (Kaur et al., 2015).

Various footprint measurements calculate anthropogenic emissions to assess how much capacity is still available until emissions exceed the planet's boundaries and lead to irreversible changes. This section describes how footprint assessments are carried out and what emissions are included.

2.2.1 Corporate Carbon Footprints

In the past two decades, the human pressure on the natural environment has been quantified by calculating humanity’s “environmental footprint” (Hoekstra and Wiedmann, 2014). Environmental footprints measure various environmental concerns, for instance, the carbon, water, land and material footprint (Smith et al., 2016). The focus of this research lies on the carbon footprint which is defined as “the greenhouse gases, CO2, methane, nitrous oxide, and

fluoride emitted in the production of goods and services used for final consumption and GHG emissions occurring during the consumption activities themselves” (Hertwich and Peters, 2009).

15

The following graphic (Figure 5) visualizes that the fundamental building block is a “unit footprint” which represents a single activity or process from a product, consumer or producer or a specific geographical area (Hoekstra and Wiedmann, 2014). It also shows that the resulting footprint of global production is a sum of the operational footprint of all economic sectors, which in turn is the sum of all operational footprints of companies. Additionally, the footprint of global production, global consumption and all human activities on the globe is equal (Hoekstra and Wiedmann, 2014).

Figure 5: The Relation Between Footprints of Different Entities. Source: (Hoekstra and Wiedmann, 2014, p.1114)

Evaluating a corporate’s footprint according to the European Commission is “[…] the result of an organization environmental footprint study based on the organization environmental footprint method, [which is a] general method to measure and communicate the potential life cycle environmental impact of an organization” (European Commission, 2013, p. 3). Measuring a corporate’s environmental footprint supports leaders in making decisions amidst many uncertainties (Moore et al., 2012). It has become a tool to manage environmental issues and demonstrate corporate social responsibility (Hoekstra and Wiedmann, 2014).

Figure 6 illustrates a one-directional and simplified supply chain to visualize the difference between a company’s footprint and the footprint of a product as well as the footprint of a geographical area. The operational footprint of a company is the sum of the footprints of its operations, whereas the footprint of a product is the sum of the footprints along the supply chain of a product.

16

Figure 6: The Footprint Concept of Different Entities. Source: (Hoekstra and Wiedmann, 2014, p.1116)

To measure a company’s carbon footprint, direct (operational) and indirect (supply chain) components are evaluated (Hoekstra and Wiedmann, 2014). In practice, companies are inclined to set reduction targets only in regard to their direct footprint and ignore their indirect footprint, which is often much bigger (Hoekstra and Wiedmann, 2014). The GHG protocol provides a guide for organizations to report their GHG emissions and distinguish between three different scopes (WRI and WBCSD, n.d.). Scope 1 describes direct emissions from owned or controlled sources of the organization; scope 2 emissions are indirect emissions caused by the generation of purchased electricity, heating, cooling or steam consumed by the organization, and scope 3 are all other indirect emissions that occur in an organization’s value chain and through activities like business travel, outsourcing, the purchase of materials and the use of created products or services by the organization (WRI and WBCSD, n.d.). Scope 2 and scope 3 emissions require an awareness of their shared responsibility because one company’s scope 2 and 3 another company’s scope 1 emissions (Hertwich and Wood, 2018).

2.2.2 Greenhouse Gases and GHG Equivalents

Wiedmann and Minx (2008) identified a large number of definitions that differ as to which gases are considered and where the boundaries of the analysis are set. According to the IPCC Special Report (2018, p.550-551) “greenhouse gases are those gaseous constituents of the atmosphere, both natural and anthropogenic, that absorb and emit radiation at specific wavelengths within the spectrum of terrestrial radiation emitted by the Earth’s surface, the atmosphere itself, and by clouds”. As a result the IPCC lists Water Vapor (H2O), Carbon

Dioxide (CO2), Nitrous Oxide (N2O), Methane (CH4) and Ozone (O3) as the main GHGs (IPCC,

2018). In contrary, the Kyoto Protocol targets six main GHGs which are carbon dioxide (CO2),

Methane (CH4), Nitrous Oxide (N2O), Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), Perfluorocarbons (PFCs),

and Sulphur Hexafluoride (SF6) (UNFCCC, 1998). Moreover, Nitrogen Trifluoride (NF3) has

been added due to the Doha addendum in 2012 (UNFCCC, 2012). Also, some official publications include indirect GHG’s like CO and NOx (UN, 1989).

17

In 2007, the IPCC reported that several GHGs occur naturally but have been increasing their concentration within the atmosphere due to human activities (IPCC, 2007). The increase in the concentration of each GHG in the atmosphere over a given period of time indicates its contribution to the disturbance of the radiative balance (IPCC, 2007).

CO2 equivalent units can be used to quantify GHGs and their impact on the climate. Tian et al.

(2016, p.225) “use CO2 equivalent units (CO2 equivalents) based on the global warming

potential over a time horizon of 100 years (GWP100). GWP defines the cumulative impact that the emission of 1g CH4 or N2O could have on the planetary energy budget in relation to 1g CO2

reference gas over a certain period of years.”

2.3 The Concept of Corporate Carbon Neutrality

As there is no common agreed definition, there is an extensive amount of common literature including individual definition of carbon neutrality which is analyzed in this chapter. However, the organizational focus of the concept is rarely discussed from scientific perspective. For that reason, a review of the limited publications has been added and supplemented by widely agreed publications. Following, an overview of carbon neutrality initiatives is given to show the varying pathways that might lead to CCN.

2.3.1 Corporate Carbon Neutrality in Theoretical Context

Scholars claim that carbon neutrality suffers from high interpretative flexibility (Karhunmaa, 2019). Different socio-technical imaginaries and storylines lead to an unclear picture of the term (Karhunmaa, 2019; Tozer and Klenk, 2018). Zuo et al. (2012) state that the lack of a clear definition of carbon neutrality creates a significant barrier to pursue carbon neutrality. The term also leaves questions about the “inclusion and exclusion of specific energy sources and technologies, the role of transboundary carbon flows and offsetting, and the role of carbon capture and storage” unanswered (Karhunmaa, 2019, p.174). The blurry definition of carbon neutrality might even lead to a dilution of the term carbon neutrality in the future. It is of high academic and practical relevance to comprehend the concept of carbon neutrality and its elements in order to prevent a collapse of it.

To understand the concept of carbon neutrality, written definitions on carbon neutrality are taken into account. An analysis of academic articles and standards, such as non-academic reports and guides on carbon neutrality is included (Appendix A). Those are analyzed based on four core principles of carbon neutrality. The four principles were created after a pre-analysis of the existing literature on carbon neutrality, in which the authors identify major differences in the described purpose of carbon neutrality, the approach to define the emission scope, such as in the role of carbon offsetting and system thinking in order to achieve carbon neutrality. The 21 documents are examined on the basis of the following four principles:

1. The purpose of carbon neutrality 2. The definition of scope

3. The role of carbon offsets 4. The role of system thinking

Before further analyses are carried out, the origin of the terms “carbon” and “neutral” are explained to build a fundamental basis.

18

In the context of carbon neutrality, “carbon” is a technical term and describes a “non-metallic chemical element, which occurs in crystalline form as diamond and graphite, in black, amorphous form as coal, charcoal, and soot, and in combined form in numerous substances, including all living tissues, petroleum and natural gas, and many minerals” (OED, 2008). “Neutrality” is often referred to political neutrality in wars, discussions and conflicts between contending parties (OED, 2003). Hereby, a state, an individual or a group of people is not taking any side and remains on the middle ground (OED, 2003). However, carbon neutrality rather refers to a state of being chemically neutral (OED, 2003).

And the etymology of “carbon neutrality” is defined as an adjective (of a process, agency, etc.) “making or resulting in zero net emission of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere; claiming to balance any carbon dioxide emission by some form of carbon offset” (OED, 2008).

2.3.1.1 Core Principle 1: The Purpose of Carbon Neutrality

The examination of the first core principle aims to understand the perceived goal of carbon neutrality. The gathered definitions are mostly based on the effect that carbon neutrality has. Therefore, we compare definition statements with the focus on what carbon neutrality aims to reach eventually.

In general, there are two significant distinctions between the purpose of carbon neutrality, that deviate slightly, but can be summarized in: “reaching net-zero emissions” and “not contributing to climate change”. The majority of the examined statements define carbon neutrality as the state of having net-zero emissions and two definitions combine both perspectives. Additionally, two definitions focus on the reduction of emissions in general. The following Table 2 gives an overview of the different definitions and perspectives on the purpose of carbon neutrality.

Reaching net-zero emissions Not contributing to climate change

(Carbon Trust, 2006) and (Corbett, 2009)

Carbon neutrality is achieved when emissions from a product, activity or a whole organization are

netted off.

(Chiriaco et al., 2019)

Low-carbon agricultures being able to compensate anthropogenic GHG emissions generated from the field allow food production a potential of carbon neutrality without

contributing to exacerbate climate change. (Commonwealth of Australia, 2019)

Carbon neutral means reducing emissions where possible and compensating for the remainder by investing in carbon offset projects to achieve

net-zero overall emissions.

(Gössling, 2009) Reaching a destination does

not contribute to climate change.

(Coulter et al., 2008)

’Carbon neutral’ is often used as a short form for the real intended effect, to

become neutral in relation to the net radiative balance.

(Johnson, 2016) Carbon neutrality is a logical starting point to

reverse the negative consequences on the earth’s atmosphere.