HOW STIMULI BY TOYS AFFECT PIGS

GROWTH, HEALTH AND WELFARE

Carin Södergren

Examensarbete i biologi 15 högskolepoäng, 2010

Handledare: Gunilla Rosenqvist

Avdelningen för biologi

Högskolan på Gotland, SE-621 67 Visby www.hgo.se

Bilden på framsidan föreställer: En 6 veckor gammal griskulting som

undersöker en leksak som hänger längs boxväggen.

Fotograf: Carin Södergren

Denna uppsats är författarens egendom och får inte användas för publicering utan författarens eller dennes rättsinnehavares tillstånd. Carin Södergren

1

CONTENTS

ABSTRACT……….. 2

INTRODUCTION………... 3

MATERIAL AND METHODS………... 4

Animals……… 4

Housing and husbandry……….... 5

Experimental design and toys……….. 5

Stress tests……… 5 Statistical analysis……… 5 RESULTS……….. 6 Stress………. 6 Weight………... 9 Stereotypic behavior……….. 9

Illness and death………... …10

DISUSSION………... 10 Future research……….……...…..12 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………. 12 REFERENCES………. 13 SUMMARY/SAMMANFATTNING………..……… 14 APPENDIX 1………. 17

2

ABSTRACT

Pigs do naturally have a high motivation to explore their environment. In a poor environment pigs still display this motivation and when there is no stimulation in the pen, pigs direct their behavior at pen-mates and pen components. Lack of stimulation can lead to decreased welfare and increased stress. This study investigates if extra stimuli by toys would affect pigs growth, health and welfare. Growing pigs (219) were followed during 7 weeks and divided into twenty two pens, eleven with toys and eleven without toys. I found partly support for the prediction that toys would help in a short time perspective but there was no support for the prediction that in a longer run the toys (used in this experiment) would increase pigs welfare. One explanation to this might be the straw that all the pens had (by law in Sweden), which seemed to be the most importuned component for satisfying pigs behavioral needs.

3

INTRODUCTION

Welfare of domestic animals is very important, both for social and scientific reasons. Not only is it important for animal’s wellbeing, animal welfare is also linked with farmers and suppliers income. If the animal is not healthy and well, then food production and product quality is not satisfying (Smulders et al. 2006). In modern pig husbandry, growing pigs are held in small areas with a barren environment. Behavioral studies show that such intensive housing

conditions may hamper the development of normal behavioral patterns and can have negative effects on pigs welfare (de Jong et al. 1998). Welfare is a complex topic, combining both subjective and objective aspects of the animal’s quality of life. One definition is ‘The welfare of an individual is its state as regards its attempts to cope with the environment’, and to cope is to have control of mental and bodily stability (Smulders et al. 2006). European animal welfare legislation is built on the principle that all animals have an intrinsic value. Animals should therefore be able to express species-specific behavior (Day et al. 2007).

Pigs have a high motivation to explore their environment and are very curious animals. Their exploring behavior often involves their snout, and pigs has a tendency to express smelling, rooting and chewing behaviors as a result of both exploratory and feeding motivation. This is probably a rest from their wild relatives who lived in semi-woodland areas, where they had to forage in the ground for food (Scott et al. 2008, Day et al. 2007).

In a poor environment pigs still display an inherent motivation to explore and when there is no stimulation in the pen the pigs direct their behavior at the limited number of substrates available, namely pen-mates and pen components (Scott et al. 2008).

Chronic stress is a widespread phenomenon in modern industrial swine production, where the stress is constantly present (Hjelholt-Jensen et al. 1995). The piglets leave the sow when they are 5-6 weeks old, which is very different from natural situations in the wild where the male piglets stay with their mother until they are 20 months. Feral sows are highly social animals that wander around in family groups with a strong and stable hierarchy and surrounded by offspring (both sub-adult males and females) for which they may exhibit communal care (de Jonge et al. 1995). Adult males often live solitary and overt aggression is rare (except between adult males under mating season) and unfamiliar pigs generally avoid each other (D´Eath 2002). This is in strong contrast to commercial conditions where pigs of similar ages and weight often are mixed with unfamiliar individuals. Mixing can occur at several stages of a pigs life, at weaning, during the growing phase and for transport. Conflicts and fights between dominant individuals arise to set the hierarchy and this pattern may facilitate the development of social stress (D´Eath 2002, Olsson et al. 1999). Studies show that mixed pigs in captivity have a decreased growth rate and are more susceptible to disease and chronic stress, a high level of chronic stress is a sign of reduced animal welfare (Hjelholt-Jensen et al. 1995, Rutherford et al. 2006).

When there is a lack of stimulation, pigs do not get the opportunity to express their natural instincts/behavior and a sign of this is stereotypic behavior such as tail-biting, ear-biting, increased aggressiveness and bullying (Blackshaw et al. 1996, Smulders et al. 2006, Scott et

4

al. 2008). Earlier studies show that provision of an enrichment device such as a soft, pliable, rubber dog toy can reduce the expression of the aggressive and stereotypic behaviors

commonly associated with confinement (Day et al. 2001).

Pig producers within the EU are legally required to provide pigs with environmental enrichment, and EU Directive 2001/93/EU lists straw, hay, wood, sawdust, mushroom compost and peat as suitable materials for satisfying the pigs behavioral needs

(Scott et al. 2008).

Absence, presence or type of environmental enrichment can affect behavioral diversity and flexibility in such a way that the animal is more or less able to cope with novel or stressful situations (Day et al. 2001). Also, studies show the importance of new and fresh enrichment presented on the floor. If the pen becomes soiled by fecal material, the enrichment has no effect and the pigs lose their interest (Scott et al. 2008).

The aim of this experiment was to determine how extra stimuli by hanging toys affect pigs’ growth, health and welfare. One group of growing pigs was exposed to hanging dog toys and one group was not. In accordance with previously published literature, my hypothesis was that:

(1) Pigs’ stress behavior will decrease when they can use toys as stimuli.

I predict that pigs with toys will approach me faster than pigs without toys and I also predict that pigs with toys will have a higher mean weight than pigs without toys.

(2) Pigs’ welfare will increase when they can use toys as stimuli.

I predict that the number of pigs with stereotypic behavior will decrease when they can use toys as stimuli. I also predict that illness and death will decrease among those pigs that can use toys as stimuli.

MATERIALS AND METHODS Animals

The experiment was conducted on the pig farm Västerväte Lantbruks AB in Väte, Gotland. The experimental animals were 219 male and female growing pigs (Hampshire x Swedish Landrace Breed). The piglets were 5 weeks old and had just left the sow when they arrived to the experimental building. The sexes where mixed (males castrated) and the individuals were distributed in different pens after size, in a total of 22 pens with 10 ± 1 individuals in each pen.

Housing and husbandry

The experimental building contained twenty-two identical part-slatted pens and the pen size was 1,20 meter x 3,80 meter. Eleven pens were located on either side of the central passage which ran the length of the building. Solid metal panels were constructed on the sides of the

5

pens, except those adjacent to the slatted area. This arrangement allowed pigs to have limited visual and tactile contact with the pigs in the neighboring pens. The pens were pressure-washed before the entry of all experimental groups, and the floor was cleaned daily by the farm workers. The pigs were fed automatically tree times per day with wet food made mainly of rye, wheat and other growth substances. These diets contained all of the vitamins and minerals required by the pigs at that stage of growth.

Experimental design and toys

I randomly assigned 11 pens to test-pens and 11 pens to control-pens. When the piglets were moved to the new pen with new pen-mates, toys were introduced to the test-pens. The toys were hawsers made for dogs. Three different toys were used, first a hawser that was made by two loops that went through a ball, second a straight hawser with a knot on each side and third a circular hawser with a piece of material and a peep pillow in the middle (Fig. 1). Five toys were distributed in each test-pen and fixed on the pen-wall in strong strings. The number of toys per pen was decided to avoid competition and two pigs per toy were considered as satisfying. Straw were given daily to all pens. The animals were housed in the experimental building for a 7-week period.

Fig. 1. The five different dog toys that were distributed in the test-pens. From the left a circular hawser with a piece of material and a peep pillow, in the middle a hawser that was made by two loops that went trough a ball and to the right a straight hawser with a knot on each side(Photographer: Carin Södergren).

Stress tests

Fear of humans has been associated with stress (Day et al, 2001), so I measured the response from the piglets once a week during 7 weeks between 9.00 and 10.00 am. I measured the stress by entering the pen, walking in a circle and then I sat down on the pen floor motionless for a period of maximum 120 seconds. Stop watch was used to measure how many seconds it took for the first pig to approach me and how many seconds it took for all pigs to approach me.

6

To investigate if the results in the experimental building were influenced by the pigs getting habituated to my presence, I also measured the response of piglets in the same age but not familiar with me in week 6 and 7 in 10 different pens in another building.

All the pigs were weighed when they were 5 weeks old (week 1) and when they were 12 weeks old (week 7). Stereotypic behavior; belly-massaging (one pig massages another pigs belly with its snout which causes swelling and redness) was counted once a week. I also observed all illness, injuries and death among the pigs during the experimental period.

Statistical analysis

Stress

Stress differences between pigs in test and control-pens, and also between pigs in the pens in the experimental building and pens in another building, were tested by using t-test or Mann-Whitney U-test, depending on if the data were normally distributed, and if the data had equal variances, which was considered by an F-test (Fowler et al. 1998).

Weight

Differences in weight gain between pigs in test and control-pens were tested by using t-test (Fowler et al. 1998).

Stereotypic behavior

Differences in frequency of belly-massaging between test and control-pens were tested by using χ2-test (Fowler et al. 1998).

Illness and death

Differences in frequency of ill or dead pigs between test and-control pens were tested by using χ2-test (Fowler et al. 1998).

RESULTS Stress

When comparing the whole test period (7 weeks) I found no difference in the average time for one pig to approach me in the test-pens (10,07± 3,26 sec) compared to the average time for one pig to approach me in the control-pens (10,65± 3,09 sec) (t= -0,03, n=11, p>0,05). The average number of seconds it took for one pig to approach me, was much higher in week 1, compared to week 2-7. When comparing the result between pigs in the test and control pens for each week, I found no significant difference the first week, for one pig to approach me (t=0,140, n=11, p>0,05) , neither for the second week (U=56, p>0,05, Mann-Whitney U-test), or the third week (U=47, p>0,05, Mann-Whitney U-test), or the fourth week (t=-1,35, n=11,

7

p>0,05), neither for the fifth week (t=-0,52, n=11, p>0,05), or the sixth week (t=-1,57, n=11, p>0,05) and neither for the seventh week (t=-0,23, n=11, p>0,05) (Fig. 2, Appendix 1).

Fig 2. Average number of seconds ± SE, it took for one pig to approach me in test-pens (with toys as stimuli) (n=11), and control-pens (n=11) for each week, during seven weeks.

When comparing the whole test period (7 weeks), I found no difference in the average time for all the pigs in the test-pens to approach me (17,92 ± 3,8 sec) compared to the average time for all the pigs in the control-pens (28,10 ± 4,43 sec)

(t= -0,63, n=11, p>0,05).

The average number of seconds it took for all pigs to approach me in week 1, was much higher compared to the rest of the weeks. When comparing the result between pigs in the test and control-pens for each week, I found no significant difference the first week, for all pigs to approach me (t=0,147, n=11, p>0,05). However when comparing the result the second week I found a significant difference between pigs in the test and control-pens regarding all pigs to approach me (U=29,5, p<0,05, Mann-Whitney U-test). The average time for pigs in the test-pens to approach me was 4,9 ± 1,4 seconds, and the average time for the pigs in the control-pens to approach me was 28,4 ± 13,8 seconds.

I found no significant differences between pigs in the test and control-pens the third week (U=47, p>0,05, Whitney U-test), neither the fourth week (U=46,5, p>0,05, Mann-Whitney U-test), or the fifth week (U=36, p>0,05, Mann-Mann-Whitney U-test), or the sixth week

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Se co n d s Week Test-pen Control-pen

8

(U=32,5, p>0,05, Whitney U-test) and neither the seventh week (U=35, p>0,05, Mann-Whitney U-test)(Fig.3, Appendix 1).

Fig. 3. Average number of seconds ± SE, it took for all pigs to approach me in test-pens (with toys) (n=11), and control-pens (n=11) for each week, during 7 weeks.

The average time for the first pig to approach me in the other building with pigs not familiar with me, in week 6 and 7 was 111,7 ± 26,9 seconds. The average time for the first pigs to approach me in test-pens was 10,1 ± 8,9 seconds and in control-pens 10,5 ± 8,4 seconds. There was a significant difference for the first pig to approach me between the pigs in the test-pen, and the pigs not familiar with me (U=4, p<0,05, Mann-Whitney U-test). Between the pigs in the control-pens and the pigs not familiar with me, there was also a significant difference for the first pig to approach me (U=4, p<0,05, Mann-Whiney U-test).

The average time for all pigs to approach me in the other building with pigs not familiar with me, in week 6 and 7, was 171,5 ± 25,1 seconds. The average time for all pigs to approach me in test-pens was 17,9 ± 11,9 seconds and in control-pens 27,9 ± 10,1 seconds. There was a significant difference between the test-pens and the pigs not familiar with me, regarding all pigs to approach me (U=1, p<0,05, Mann-Whitney U-test). There was also a significant difference between the control-pens and the pigs not familiar with me regarding all pigs to approach me (U=2, p<0,05, Mann-Whitney U-test).

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Se co n d s Week Test-pen Control-pen

9

Weight

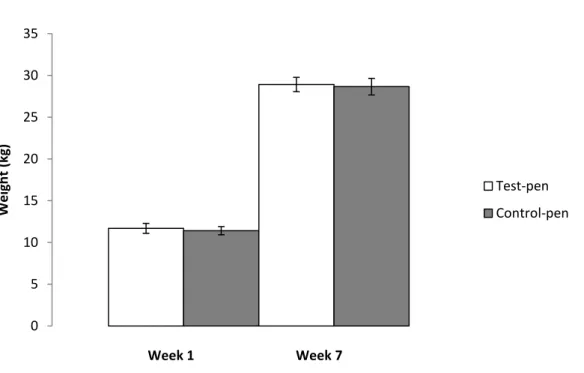

Week 1 when all the pigs were weighed, the pigs in the test-pens had a starting average weight of 11,69 ± 0,6 kilo and the pigs in the control-pens had a starting average weight of 11,41 ± 0,49 kilo per pen (Appendix 1). At the start of the experiment there was no significant difference between the pens (t=0,352, n=11, p>0,05). After 7 weeks the pigs in the test-pens had gained 17,23 ± 0,43 kilos whereas those in the control-pen had gained 17,24 ± 0,49 kilos (Fig 4, Appendix 1). There was no significant difference between the pens regarding weight gain (t=-0,025, n=11, p>0,05).

Fig. 4. Average weight (kg) ± SE of pigs in test-pens (n=11) (with toys) and control-pens (n=11) during week 1 and week 7.

Stereotypic behavior

Belly-massaging between pen-mates was observed in eleven of the twenty-two pens. In the test-pens there were eight individuals in six of the test-pens that had red and swollen marks caused by belly-massaging and in the control-pens there were nine individuals in five of the control-pens (Appendix 1). There was no significant difference in the frequency of belly-massaging between test and control-pens (χ2=0, df=1, p>0,05).

Illness and death

Illness as diarrhea, wounds and belly hernia was observed among four individuals in test-pens and among six individuals in control-pens. One individual died in the test-pens and two individuals died in the control-pens (Fig.5, Appendix 1). Four of the test-pens had individuals

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 Wei gh t (k g) Week 1 Week 7 Test-pen Control-pen

10

that were ill or dead and four of the control-pens had individuals that were ill or dead. There was no significant difference in illness and death between test and control-pens (χ2=0,196, df=1, p>0,05).

Fig. 5. Average total number of ill and dead pigs ± SE in test-pens (with toys) (n=11) and control-pens (n=11), during 7 weeks.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this experiment was to investigate how stimuli by toys affect growing pigs stress behavior, weight gain, stereotypic behavior, illness and death. I predicted that pigs stress behavior would decrease when they could use toys as stimuli. The result showed that there was a significant difference in stress between the test and control groups in week 2, regarding the majority of all pigs to approach me. However, I found no differences between the test and control groups during the other weeks. This indicates that toys were only interesting or important in the beginning of the experiment, when they were new and pigs were also

probably more stressed within their new environment in the beginning. I found no differences regarding the first pig to approach me, but that could be explained by the fact that there might be individuals in each pen that are more bold or dominant, regardless presence of stimuli. My presence could also have influenced the result. I found a significant difference between the pens in the experimental building and the pens in another building with pigs not familiar with me at the end of the experiment. This indicates that the result in the experimental building could have been influenced by the fact that the pigs had been habituated to my presence. The pigs learned that I was no threat and did them no harm, so for each time I entered the pen and nothing happened, they approached me faster and faster.

The stress among the pigs in the experimental building could have been greatest the first week because they had just been taken from the sow and housed with new pen-mates, which is a big

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 N u m b e r o f i ll an d d e ad p ig s Test-pen Control-pen Test-pens Control-pens

11

stress-factor (Olsson et al. 1999). When mixing occurs, fights between the dominant individuals often arise and the pigs get more aggressive. This leads to injuries and

physiological stress (D´Eath 2002). This behavior is greatest in the beginning and decrease when there is a stable hierarchy in the pens. However, the pigs in the other building had also been taken from the sow and mixed with other pen-mates during the same age and time as the pigs in the experimental building and still showed a higher stress. Therefore it is more likely that my presence in the experimental building influenced the result.

There was no difference regarding the pigs’ gain in weight between the different groups. The pigs where given the same amount of food, had the same amount of pen-mates and where housed in the same environment. These were clearly the most important components for a pigs weight gain and toys apparently did not have any effect.

I can not reject the hypothesis that pigs’ stress behavior will decrease when they can use toys as stimuli, as I found support in week 2 for the prediction that pigs with toys will approach me faster than pigs without toys. This was not true for week 1 and week 3-7, and I found no support for the prediction that pigs with toys will gain more weight. This makes it hard to conclude the importance or lack of importance of toys to avoid stress in pigs.

I found very little evidence for stereotypic behavior like belly-massaging. Only 17 individuals out of 219 showed this behavior and there was no difference between pigs with or without toys. Earlier studies have shown that belly-massaging can occur when the piglets leave the sow too early. When the sow is not present the piglets try to nurse their pen-mates instead, which leads to hair loss, swelling and redness (Simonsson et al. 1990). This experiment was implemented on piglets that were 5 weeks old when they left the sow and their siblings, which is the common age in modern swine production. Another common stereotypic behavior in modern industrial swine production is tail-biting (Blackshaw et al. 1996, Smulders et al. 2006, Scott et al. 2008). Studies have shown that, when straw is absent, pigs’ welfare reduces and tail-biting increases (Day et al. 2007). None of the pigs in this experiment showed this stereotypic behavior, which indicates that straw in the pens was sufficient and had a positive effect on the pigs’ welfare.

I found no difference between the groups in the number of ill or dead individuals. Five pigs in four of the test-pens and eight pigs in four of the control-pens were ill or dead. A study made by Day et al. (2007) showed that pigs reared in strawless pens caused more wounds on each other than pigs reared in pens with straw. In this experiment, both test and control pens were given straw daily, which can explain why there was no difference in illness and death between the groups.

I found partly support for the prediction that toys would help in a short time perspective but there was no support for the prediction that in a longer run the toys (used in this experiment) would increase pigs welfare. The lack of difference in the long run could not be explained by too few toys as I found that 5 toys in each pen were sufficient. I found no competition for them which could have given stress. Toys had only influence on the stress in the second week, when the stress caused by mixing was as highest and the toys were new and interesting. The following weeks I only observed the pigs playing with the toys when food or straw were not

12

available. The pigs used toys only as a last option. I also observed that pigs lost interest in the toys, if the toy fell on the floor. This supports the statement of Scott et al. (2008) regarding enrichment presented on the floor of the pen may become soiled by faecal material, which has been shown to result in a loss of interest. Straw was given to all pens and earlier studies conclude that straw is known to offer advantages to animal welfare due to its use as a recreational stimulus, a nutritional stimulus and as bedding (Day et al. 2007). All pig producers within EU are legally required to provide pigs with environmental enrichment as straw, haw, wood and sawdust etc. (Scott et al. 2008). The fact that the pigs in this study showed very little stereotypic behavior, like belly-massaging, and the number of ill or dead individuals was low, indicates that straw has a higher effect than toys on satisfying pigs’ natural behavior, which corresponds to earlier studies by Scott et al. (2008).

Future research

For future studies I recommend changing toys often so pigs don´t loose interest in them and use toys that stimulate pigs feeding motivation. I also recommend to compare pigs from different farms and to have a larger sample.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I gratefully acknowledge my supervisor Professor Gunilla Rosenqvist, Norwegian University of Science and Technology and Gotland University, for her great support, guidance, good critics and practical help. I would also like to gratefully acknowledge Joakim, Johan, Owe and Ulla Fredriksson at Västerväte Lantbruks AB, for letting me perform this experiment on their farm and also for all their help and support. A special acknowledgement to Joakim

Fredriksson, that helped me weigh all the 219 pigs when they were 12 weeks old and very strong and cumbersome.

13

REFERENCES

Blackshaw, J.K., Thomas, F.J. and Lee, J-A.1996. The effect of a fixed or free toy on the growth rate and aggressive behaviour of weaned pigs and the influence of hierarchy on initial investigation of the toys. Animal

Behaviour Science 53:203-212.

Day, J.E.L., Spoolder,H.A.M., Burfoot,A., Chamberlain,H.L. and Edwards, S.A. 2001. The separate and interactive effects of handling and environmental enrichment on the behaviour and welfare of growing pigs.

Animal Behaviour Science 75:177-192.

Day,J.E.L., Van de Weerd, H.A. and Edwards,S.A. 2007. The effect of varying lengths of straw bedding on the behavior of growing pigs. Animal Behaviour Science 109:249–260

DÉath, R.B. 2002. Individual aggressiveness measured in a resident-intruder test predicts the persistence of aggressive behavior and weight gain of young pigs after mixing. Animal Behaviour Science 77:267-283. De Jonge, I.C., Ekkel, E.D., Van der Burgwal, J.A., Lambooij, E., Korte, S.M., Ruis, M.A.W., Koolhaas, J.A. and Blokhuis, H.J. 1998. Effects of Strawbedding on Physiological Responses to Stressors and Behavior in Growing Pigs. Physiology & Behavior 64:303–310.

De Jonge, F., Bokkers, E.A.M., Schouten, W.G.P. and Helmond, F.A. 1995. Rearing Piglets in a Poor Environment: Developmental Aspects of Social Stress in Pigs. Physiology & Behavior 60:389-396. Fowler, J., Cohen, L. & Jarvis, P. 1998. Practical statistics for field biology. 2. Ed. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester, UK.

Hjelholt Jensen, K., Pedersen, L., Keller Nielsen, E., Heller, K., Ladewig, J. and Jöregensen, E. 1995.

Intermittent Stress in Pigs: Effects on Behavior, Pituitary-Adrenocortical Axis, Growth, and Gastric Ulceration.

Physiology & Behavior 59:741-748.

Olsson, I.A.S., de Jonge, F.H., Schuurman, T. and Helmond, F.A., 1999. Poor rearing conditions and social stress in pigs: repeated social challenge and the effect on behavioural and physiological responses to stressor.

Behavioural Processes 46:201–215.

Rutherford,K.M.D., Haskell, M.J., Glasbey,C. and Lawrece,A.B. 2006. The responses of growing pigs to a chronic-intermittent stress treatment. Physiology & Behavior 89:670-680.

Scott, K., Taylor, L., Bhupinder P.G. and Edwards, S. 2008. Influence of different types of environmental enrichment on the behaviour of finishing pigs in two different housing systems 3. Hanging toy versus rootable toy of the same material. Animal Behaviour Science 116:186–190.

Simonsson,A., Andersson,K., Andersson,N., Dalin,A-M., Einarsson S., Gustafson,N., Juneberg,K., Holmberg,K. & Hökås,G. 1990. Svinboken för avels-, smågris- och slaktsvinsuppfödare. Författarnas och LT:s förlag. Centraltryckeriet AB, Borås.

Smulders, D., Verbeke, G., Morméde, P. and Geers, R. 2006. Validation of a behavioral observation tool to assess pig welfare. Physiology & Behavior 89:438–447.

14

SAMMANFATTNING

Hur stimuli av leksaker påverkar grisars tillväxt, hälsa och välfärd Inledning

Välfärd hos domesticerade djur är en viktig fråga, både vetenskapligt och för samhället. Inte bara djurets välmående i sig är viktigt, utan det är också kopplat till djurproducenters och butikers inkomst. Är djuret inte friskt och välmående ger det dålig produktion och dålig köttkvaliteé. Inom modern svinindustri hålls djuren på en liten yta av ekonomiska skäl, vilket tillför dem lite stimulans. Grisen får ett minskat uttryck för normala beteenden, vilket leder till minskad välfärd. Grisar har en hög motivation att utforska sin omgivning och är väldigt nyfikna. De använder främst tryne och mun för att utforska, de nosar och tuggar på objekt i deras omgivning. Detta tros ha evolverats fram genom deras tidigare boende i skogsmarker, där de tillbringade mycket tid med att söka efter föda i marken. Domesticerade grisar har ännu kvar denna motivation att utforska och när de inte får uttryck för sin motivation, riktar de detta beteende på det som finns tillgängligt, nämligen boxkamrater eller boxinredning. Kronisk stress är en oundviklig faktor inom svinproduktionen. Exempel på detta är att griskultingarna lämnar sin mamma vid 5-6 veckors ålder, vilket inte sker i grisars naturliga liv. Grisarna blandas också med varandra under flera steg i sitt liv, vilket leder till ökad stress då vilda grisar lever i familjegrupper och undviker okända individer i så stor mån som

möjligt. När man blandar grisar ger det en jämnare tillväxt, men det leder också till att

konflikter och slagsmål uppstår mellan dominanta individer för att bilda hierarkier. Stereotypa beteende såsom svans- och öronbitning, ökad aggressivitet och mobbning kan också uppstå bland grisar när avsaknad av stimulans förekommer. Studier har visat att omgivningen har en stor påverkan för hur grisar hanterar okända och stressfulla situationer.

Syftet med denna studie var att undersöka hur stimulans av leksaker påverkar grisars tillväxt, hälsa och välmående.

(1) Första hypotesen var att grisars stressbeteenden kommer att minska när de kan använda leksaker som stimuli. Min prediktion var att grisar med leksaker kommer att komma fram till mig fortare än grisar utan leksaker och min andra prediktion var att grisar med leksaker kommer att ha en högre medelvikt än grisar utan leksaker.

(2) Andra hypotesen var att grisars välfärd kommer att öka när de kan använda leksaker som stimuli. Min prediktion var att andelen grisar med stereotypa beteenden kommer att minska när de kan använda leksaker som stimuli och min andra prediktion var att antalet sjuka och döda individer kommer att minska bland de grisar som kan använda leksaker som stimuli.

Material och metoder

Studien utfördes på Västerväte Lantbruks AB på Gotland i 7 veckor. Grisarna var 5 veckor när studien påbörjades och 12 veckor när studien avslutades. Det var 219 individer av blandat kön som var uppdelade efter storlek i 22 boxar. 11 boxar utsågs slumpmässigt till testboxar

15

och försågs med leksaker, medan de resterande 11 boxarna blev kontrollboxar. Fem

hundleksaker i trossmaterial tilldelades varje testbox och hängdes i boxgallret med balsnören. Alla boxar fick strö dagligen. Stress mättes i boxarna en gång i veckan, genom att jag gick in i boxen, gick ett varv, satte mig ned och mätte med tidtagarur, hur många sekunder det tog för första grisen att komma fram till mig samt hur många sekunder det tog för majoriteten av alla grisar att komma fram till mig. De två sista veckorna mättes även stressen i en annan byggnad på grisar i samma ålder, för att se om min närvaro påverkade resultatet i experiment

byggnaden. Alla grisar i experimentbyggnaden vägdes vecka 1 och 7. Stereotypa beteenden observerades en gång i veckan. Sjukdomar och dödsfall observerades dagligen under hela studien.

Resultat

Medelvärdet för en gris att komma fram till mig i testboxarna var 10,07 ± 3,26 sekunder och medelvärdet för en gris att komma fram till mig i kontrollboxarna var 10,65 ± 3,09 sekunder. När jag jämförde resultatet för varje vecka, fann jag ingen skillnad mellan test- och

kontrollboxarna vecka 1-7, gällande första grisen att komma fram till mig.

Medelvärdet för alla grisar att komma fram till mig i testboxarna var 17,92 ± 3,8 sekunder och i kontrollboxarna 28,10 ± 4,43 sekunder. Jag fann sammantaget ingen signifikant skillnad i stress mellan test- och kontrollboxarna.

När jag jämförde resultatet för varje vecka, fann jag ingen skillnad mellan grisarna i test och kontroll boxarna vecka 1 gällande alla grisar att komma fram till mig. Däremot när jag jämförde resultatet för vecka 2 (U=29,5, p<0,05, Mann-Whitney U-test), fann jag en signifikant skillnad. Medelvärdet för alla grisar att komma fram till mig i testboxarna var 4,9 ±1,4 sekunder och för alla grisar i kontrollboxarna var medelvärdet 28,4 ± 13,8 sekunder. Vecka 3-7 fann jag ingen signifikant skillnad mellan grisarna i test och kontrollboxarna. Medelvärdet för en gris att komma fram till mig vecka 6 och 7 i den andra byggnaden med naiva grisar var 111,7 ± 26,9 sekunder, medan motsvarande värde i testboxarna var 10,1 ± 8,9 sekunder och i kontrollboxarna 10,5 ± 8,4 sekunder. Jag fann en signifikant skillnad mellan grisarna i testboxarna och den andra avdelningen gällande första grisen att komma fram till mig ((U=4, p<0,05, Mann-Whitney U-test). Jag fann även en signifikant skillnad mellan kontrollboxarna och den andra avdelningen gällande första grisen att komma fram till mig (U=4, p<0,05, Mann-Whiney U-test).

Medelvärdet för alla grisar att komma fram till mig i den andra byggnaden med naiva grisar vecka 6 och 7 var 171 ± 25,1 sekunder, medan motsvarande värde i testboxarna var 17,9 ± 11,9 sekunder och i kontrollboxarna 27,9 ± 10,1 sekunder. Jag fann en signifikant skillnad mellan testboxarna och den andra avdelningen gällande alla grisar att komma fram till mig (U=1, p<0,05, Mann-Whitney U-test). Det var också en signifikant skillnad mellan

kontrollboxarna och den andra avdelningen gällande alla grisar att komma fram till mig (U=2, p<0,05, Mann-Whitney U-test).

16

Första veckan när alla grisar vägdes, hade grisarna i testboxarna en medelvikt på 11,69 ± 0,6 kg och grisarna i kontrollboxarna hade en medelvikt på 11,41 ± 0,49 kg. Efter 7 veckor hade grisarna i testboxarna ökat med 17,23 ± 0,43 kg och de i kontrollboxarna hade ökat med 17,24 ± 0,49 kg. Jag fann ingen signifikant skillnad mellan test och kontrollboxarna gällande

viktökning.

Det stereotypa beteendet mag-knuffning observerades i 11 av de 22 boxarna. I testboxarna observerades 8 individer med röda märken och svullnader orsakat av mag-knuffning och i kontrollboxarna observerades 9 individer. Jag fann ingen signifikant skillnad mellan test-och kontrollboxarna.

Sjukdomar som diarré, sår och magbråck observerades hos fyra individer i testboxarna och hos sex individer i kontrollboxarna. En individ dog i testboxarna och två individer dog i kontrollboxarna. Fyra av testboxarna hade individer som var sjuka eller döda och fyra av kontrollboxarna hade individer som var sjuka eller döda. Jag fann ingen signifikant skillnad mellan sjukdom och dödsfall i test- och kontrollboxarna.

Diskussion

Jag fann en signifikant skillnad mellan test- och kontrollboxarna vecka 2 gällande alla grisar att komma fram till mig. Detta kan bero på att stressen var som störst i början när grisarna blivit indelade i nya grupper och leksakerna ännu var nya och intressanta. Jag fann ingen signifikant skillnad gällande första grisen att komma fram till mig, vilket kan bero på att det alltid kan finnas en framåt och dominant individ i varje grupp, oberoende av stimulans av leksaker.

Jag fann ingen signifikant skillnad mellan test- och kontrollboxarna gällande viktökning. Grisarna gavs samma föda, hade lika stora boxar och samma antal boxkamrater, vilket visade sig vara de viktigaste faktorerna för grisarnas viktökning. Jag fann heller ingen skillnad mellan test- och kontrollboxarna gällande stereotypa beteenden, sjukdomar och dödsfall. Tidigare studier visar att strö har en stor effekt på stereotypa beteenden och skador. Både test- och kontrollboxarna fick strö dagligen, vilket kan förklara varför det inte blev någon skillnad mellan grupperna.

Stressen i boxarna minskade för varje vecka, vilket kan bero på att grisarna vande sig vid min närvaro och för varje gång jag gick in i boxen och inget hände, gick det fortare och fortare för dem att komma fram. Mätningen av stress i den andra byggnaden, där jag endast besökte boxen en gång, indikerar att min närvaro påverkade resultatet.

Det visade sig att leksakerna hade en kortsiktig effekt, men att grisarna tappade intresse för dem på längre sikt. Endast då föda eller strö saknades kunde man se en stor aktivitet hos dem som hade leksaker. Detta indikerar att strö har en större inverkan på grisars välfärd än

leksaker.

För framtida studier rekommenderar jag att byta leksaker ofta och använda leksaker som stimulerar grisens födosök. Jag rekommenderar även att jämföra grisar från olika gårdar och använda större replikat..

17

Appendix 1. The average weight, number of ill individuals, number of dead individuals, number of individuals

with stereotypic behavior and the number of seconds it took for one pig to approach me and for all pigs to approach me in week 1-7, for each pen (testpen 1-11 and controlpen 1-11) in the experimental building.

C1 1 C1 0 C9 C8 C7 C6 C5 C4 C3 C2 C1 T1 1 T1 0 T9 T8 T7 T6 T5 T4 T3 T2 T1 Pen 11 8,2 6 1 2 ,3 5 1 0 ,9 1 3 ,7 5 1 1 ,9 9,3 11 1 3 ,9 1 0 ,2 9,8 1 2 ,8 8,8 1 0 ,9 1 2 ,5 5 1 4 ,4 8 ,3 6 1 0 ,3 1 0 ,8 1 2 ,7 1 3 ,7 5 1 3 ,2 We ig h t (k g ) we ek 1 2 6 ,6 8 2 4 ,1 3 2 ,1 2 8 ,3 3 3 ,0 5 3 0 ,0 5 2 4 ,4 2 7 ,8 3 1 ,9 2 5 ,8 5 2 6 ,4 2 9 ,8 2 3 ,8 2 7 ,4 3 1 ,2 3 2 ,9 2 5 ,1 5 2 9 ,7 5 2 7 ,4 2 9 ,8 5 3 2 ,4 2 8 ,4 We ig h t (k g ) we ek 7 0 2 0 2 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 Num b er o f il l in d . 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 Num b er o f d ea d in d . 1 3 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 3 0 2 1 0 0 2 0 0 1 1 0 1 Num b er with ste re o ty p ic b eh a v io r 3 4 / 4 7 1 2 0 / 1 2 0 1 0 / 1 1 7 2 0 / 5 7 1 0 3 / 1 2 0 1 2 0 / 1 2 0 6 5 / 1 2 0 2 0 / 3 8 9 / 5 0 4 6 / 5 1 1 2 0 / 1 2 0 1 2 0 / 1 2 0 4 3 / 1 1 0 1 2 0 / 1 2 0 1 2 0 / 1 2 0 9 0 / 1 2 0 2 0 / 1 2 0 5 / 3 1 1 2 0 / 1 2 0 3 9 / 6 0 20 / 3 9 2 / 2 7 S tr ess w. 1 (se c) O n e/a ll 1 / 2 6 / 1 2 0 1 / 7 1 / 1 1 / 9 1 9 /1 2 0 1 / 1 4 1 / 6 9 / 2 2 1 / 5 1 / 6 1 / 4 1 / 3 2 / 1 7 1 / 5 1 / 5 2 / 8 1 / 2 1 / 4 1 / 4 1 / 1 1 / 1 S tr ess w.2 (se c) O n e/a ll 2 / 4 3 / 3 7 1 / 1 0 1 / 4 1 / 2 7 / 9 8 1 / 3 1 / 2 2 / 8 1 / 3 1 / 5 1 / 4 1 / 3 2 / 9 1 / 2 1 / 1 1 / 9 1 / 5 1 / 2 1 / 6 1 / 2 1 / 5 S tr ess w.. 3 (se c) O n e/a ll 1 / 3 2 / 2 9 1 / 3 1 / 1 1 / 6 1 1 / 1 2 0 1 / 2 1 / 5 5 / 4 2 1 / 3 1 / 7 1 / 4 1 / 2 1 / 3 1 / 5 1 / 1 2 / 7 1 / 2 1 / 5 1 / 3 1 1 / 5 1 / 2 S tr ess w.4 (se c) O n e/a ll 1 / 8 3 / 1 0 0 1 / 1 7 1 / 3 1 / 8 6 / 2 3 1 / 7 1 / 1 7 4 / 2 6 1 / 6 2 / 6 1 / 7 1 / 6 3 / 1 0 1 / 8 1 / 3 6 / 1 0 1 / 2 1 / 6 1 / 6 1 / 1 8 1 / 5 S tr ess w.5 (se c) O n e/a ll 1 / 9 1 / 1 2 2 / 1 3 1 / 4 1 / 4 7 / 2 0 2 / 2 1 1 / 1 0 4 / 1 4 1 / 5 2 / 6 1 / 5 1 / 6 2 / 1 0 1 / 4 1 / 3 2 / 7 1 / 8 1 / 5 1 / 7 1 / 1 0 1 / 3 S tr ess w.6 (se c) O n e/a ll 0 / 5 3 / 2 0 1 / 1 2 1 / 5 1 / 5 3 / 2 2 1 / 1 1 1 / 7 0 / 3 8 0 / 1 7 1 / 6 1 / 7 1 / 4 2 / 6 1 / 8 1 / 4 2 / 1 3 0 / 1 0 0 / 3 0 / 8 0 / 9 1 / 3 S tr ess w. 7 (se c) O n e/a ll