Cause and Effect: A Case Study on

True Fruits

Controversial 2017 Adverts and Consumer Responses

Greta JanulytėMedia and Communication Studies: Culture, Collaborative Media, and Creative Industries One-year master thesis | 15 credits Submitted: VT 2020 | 2020-08-30 Supervisor: Dr. Temi Odumosu Examiner: Solveig Daugaard

2

Abstract

This thesis sets out to design and execute an in-depth study of the True Fruits controversial advertisements by applying Encoding/Decoding as a theoretical model. It aims at examining visual rhetoric and through Critical Discourse Analysis understanding the cause and effect of the controversial True Fruits advertisements in their 2017 campaign. The research attempts to answer the question: ‘What happened on social media after True Fruits published their controversial advertisements in 2017?’. The thesis presents an analysis of True Fruits´ visual rhetoric in #jetztösterreichts campaign advertisements and then reveals consumer responses to it on social media in 2017. Thus, the thesis presents a comprehensive review of the relevant literature leading toward the key themes of German advertisement, controversial advertisement, and the representation of immigration in advertisements. Towards the end, it states the final remarks concluding the entire discussion and reflects upon the attempts that True Fruits made to communicate a political message and how consumers in social media responded to it.

Keywords: Critical Discourse Analysis, Controversial Advertisement, German Advertising, Nationalism, Racialization, Social Media, True Fruits, Visual Rhetoric

3

List of Figures

Figure 1. True Fruits Products ... 7

Figure 2. Development of Market Share ... 8

Figure 3. True Fruits Advertisement ... 9

Figure 4. True Fruits Advertisement ... 10

Figure 5. True Fruits Advertisement ... 10

Figure 6. True Fruits Advertisement ... 11

Figure 7. True Fruits Facebook post ... 12

Figure 8. Asylum applications ... 14

Figure 9. Presidential elections in Austria ... 15

Figure 10. Tobacco Moor ... 17

Figure 11. Trademark for Cacao... 17

Figure 12. A Soap Advertisement ... 17

Figure 13. Sarotti Moor ... 18

Figure 14. Afri-Cola advert in 1938 ... 21

Figure 15. The Flag of Israel ... 23

Figure 16. Successful United Colors of Benetton Campaigns ... 25

Figure 17. Unsuccessful United Colors of Benetton Campaigns ... 26

Figure 18. Encoding and decoding model by Stuart Hall ... 28

Figure 19. True Fruits post on Instagram ... 36

Figure 20. True Fruits post on Facebook ... 37

Figure 21. True Fruits post on Twitter ... 37

Figure 22. Fairclough's Framework for CDA ... 39

List of Table

Table 1. Scope of audience engagement on True Fruits Social Media... 364

Table of Contents

List of Figures List of Table

1. Introduction ... 6

2. Background and Context ... 7

2.1. True Fruits History ... 7

2.2. The 2017 Advertisement Campaign ... 9

2.3. Political Background in Germany and Austria in 2010s ... 12

3. Literature review ... 16

3.1. Key Themes in German Advertising ... 16

3.1.1. Patterns of Racialization in Colonial Imagery... 16

3.1.2. German advertising and politics in 20th century ... 18

3.1.3. Nazi Propaganda ... 20

3.1.4. Visual Nationalism ... 22

3.1.5. Controversial Advertisement Framework ... 24

3.1.6. Representation of Immigration in Visual Culture and the Media ... 26

4. Theoretical Framework ... 28

4.1. Encoding and Decoding Model... 28

4.2. Visual Rhetoric and Semiotics ... 30

4.3. Social Representation ... 31

5. Research Questions... 32

6. Methodology ... 34

6.1. Visual Analysis ... 34

6.2. Critical Discourse Analysis on Social Media ... 35

6.3. Sample ... 40

6.4. Methodological reflections ... 40

7. Ethics ... 41

8. Presentation and Analysis of the Results ... 43

8.1. True Fruits Campaign Visual Analysis: Encoding ... 43

8.1.1. Linguistic and Semiotic Meaning ... 43

8.1.2. Racialisation ... 44

5

8.1.4. Border Politics... 47

8.2. Encoding Reflections... 48

8.3. Critical Discourse Analysis: Decoding ... 49

8.3.1. Nationalism ... 49 8.3.2. Racialization ... 51 8.3.3. Border Politics... 53 8.3.4. Marketing Campaign ... 55 8.4. Decoding Reflections ... 57 9. Limitations ... 59 10. Further Study ... 60 11. Discussion ... 62 Conclusion ... 64 12. 64 13. References ... 68 14. Appendices ... 74

6

1. Introduction

This thesis aims to analyse and present what cause and effect True Fruits` controversial advertisement campaign, released in 2017, had for their audience on social media. Using Stuart Hall’s Encoding/Decoding model, what did True Fruits intended to communicate in their advertisements and how the audience received it will be presented. Through a visual rhetoric and critical discourse analysis, the main research question: “What happened on social media after True Fruits published their controversial advertisements in 2017?” will be answered. In order to do that, I added three subsidiary questions:

• What key German advertisement themes emerged from True Fruits’ published advert campaign?

• What social and political issues were present in True Fruits advertisement campaign?

• What types of audience discourse appeared on the different social media platforms as a result of the True Fruits campaign?

The thesis is organized as follows: First, the background and context of the company True Fruits is presented, including the problem and research questions. Second, a review of the relevant literature is analysed, including the research on key themes in German advertising, controversial advertisements, and the visual representation of immigration. The thesis is followed with a two-part theoretical framework consisting of: encoding/decoding model, rhetoric, semiotics and social representation and audience reception (Critical Discourse Analysis). Thereafter, the results are presented in line with the theoretical framework. Finally, I present my concluding remarks with some implications for future research.

The True Fruits campaign of 2017 created a public debate due to its controversial slogans commenting on the immigration policies proposed by far-right Austrian politicians in 2016. The aim of this study is to analyse the message released by True Fruits in their advertisements and to understand the effects of it, and how the public responded to it on social media. In the conclusion, the main research question is answered and suggestions for further research and use by other academics are presented.

7

2. Background and Context

2.1. True Fruits History

True Fruits is a smoothie producer in Germany, which was incorporated as a start-up in 2006 (Hitzemann, 2016: 169). The founders, Marco Knauf, Inga Koster, and Nicolas Lecloux spent an exchange semester in Scotland where they discovered smoothies and had the idea to start their own smoothie company back in Germany (Hitzemann, 2016: 170). They were one of Germanys pioneering smoothie production companies. The entrepreneurs’ aimed to create the most desirable non-alcoholic drink in Germany, and to build their business on values of quality, authenticity, and ‘lifestyle’ (Hitzemann, 2016: 169). One key element was that their product was sold in glass bottles, which extended their marketing strategy of “no tricks” where customers could, therefore, see exactly what they were getting (Figure 1). Furthermore, the company focussed on a product that contained no additives, preservatives, artificial colours, additional water or sugar. This was moreover represented in the company’s name, True Fruits (Carvalho, L. et al. 2013: 4). In an interview, founder Lecloux stressed the importance of authenticity: “We don’t want to advertise with idealised product pictures on the cover that have nothing to do with the actual product; with True Fruits, you see what you get” (Carvalho, L. et al. 2013).

Figure 1. True Fruits Products. Source: truefruits.com

While in the rest of Western Europe, several companies were already sharing the smoothie market (Knorr Vie, Andros, Hero Fruit Today, and several local brands

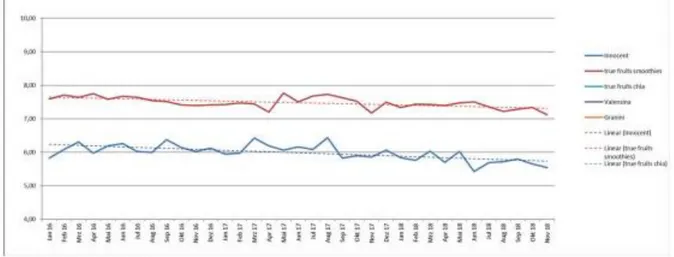

8 such as Innocent and MySmoothie), no large competitor had entered the German market by late 2006 (Hitzemann, 2016: 169). Not long after the establishment of True Fruits, large supermarkets began stocking the new smoothie product. The company grew exponentially to where they were selling over half a million smoothies per month in 2008 (Hitzemann, 2016: 170). They also expanded to the Austrian and Swiss markets. In 2010 True Fruits shared the market in Germany with four other competitors and had about a quarter of the market share by volume (Figure 2). However, as a start-up, they did not have enough capital for creating large marketing campaigns with external agencies. The company, therefore, decided to do it themselves, believing that the quality of their product would speak for itself.

Figure 2. Development of Market Share Jan 2016 - Nov 2018 of the smoothies. Source: A.C. Nielsen

In their 2019 annual marketing report, True Fruits stated that they do not want to address a specific target group, but rather “to be accessible to everyone”. However, they acknowledged that healthy lifestyle consumers and those appreciating environmental sustainability are key oriented target groups for the product. In addition to their orientation towards quality, it is recognised that these target groups also pay attention to the design, appearance, and feel of the product (True Fruits Marketing Report 2019: 4).

Even though there is no official branding strategy for their products, True Fruits does have a specific method for advertising their drinks. In recent years, they have started using controversial advertising strategies that are non-smoothie

9 related. Their campaigns have addressed topics such as racism, feminism, and the political situation in Germany and neighbouring countries. The next chapter will focus on the campaign and political-ideological connections with it.

2.2. The 2017 Advertisement Campaign

This section presents the advertisements published in print and digital media by True Fruits between 13-27 August 2017. The original releases were in German so translations are provided for each of the advertisements.

Figure 3. Schafft es selten über die Grenze (meaning ‘It rarely crosses the border’ ). Source: truefruits.com

10 Figure 4. Eure Heimat brauht uns jetzt (meaning – ‘Your homeland needs us now‘). Source:

truefruits.com

Figure 5. Bei uns kannst Du kein Braun wählen! (meaning - ‘You cannot choose brown with us!‘). Source: truefruits.com

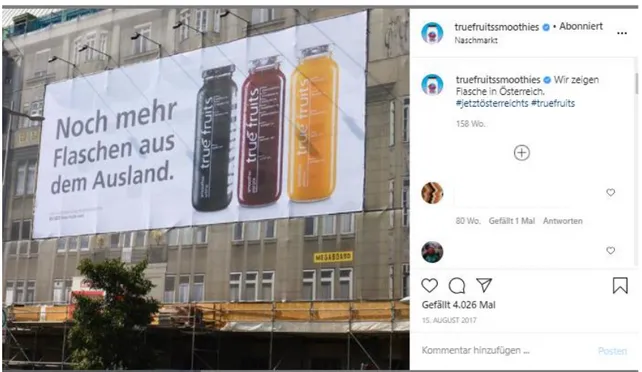

11 Figure 6. Noch mehr Flaschen aus dem Ausland (meaning - ‘Even more bottles from overseas‘).

Source: truefruits.com

The advertisements were published with the hashtag #jetztösterreichts, which means “Now – Austria” or “That is enough Austria”. The campaign got a lot of public attention in both Austria and Germany. The campaign created a controversial discussion in the digital media and specialist newspapers, as it was a political statement by the company (True Fruits marketing Report 2019: 15). On social media, it caused a “Flame War”, causing a backlash against True Fruits and even a petition was circulated against them. One of the main reasons for the intense reaction was because of the clear political agenda in the ads - one of them even used a quote by an Austrian far-right politician. However, True Fruits denied the critique and published another post on social media, saying “Yes, we are discriminatory. Attention, this advertisement can be misunderstood by stupid people” (Figure 7). In media interviews, they explained that the company was against racism. They published another social media post saying: “This campaign was a criticism of Austria's right-wing politics and the possible closure of the Brenner Pass. That this was a campaign against xenophobia as much as all forms of discrimination” (True Fruits Facebook post, February 14, 2019). The next

12 chapter will present the specific political events that had strong political connections with the True Fruits advertisements.

Figure 7. True Fruits Facebook post (February 14, 2019)

2.3. Political Background in Germany and Austria in 2010s

The political climate in Germany and Austria between 2015 and 2017 provided a context for the topics addressed in the True Fruits advertisements and they will be explored briefly here. In the last decade, Germany has become a major destination for people migrating from the Middle East and Africa, since the country has become associated with economic prosperity and stability, security, good education, and employment opportunities (Barlai et al. 2017: 107). The number of asylum applications in Germany increased tremendously between 2014 and 2015 during a period that has come to be known as the “European migrant crisis” (Grote, 2018: 5). In September 2015, Chancellor Angela Merkel received praise for her decision to allow those fleeing the conflict in Syria, to seek asylum in Germany (Grote, 2018: 22). However, Barlai writes that “at the same time, xenophobic right-wing movements, such as Patriotic Europeans against the

13 Islamisation of the Occident and the populist conservative party Alternative for Germany, gained momentum amid the crisis” (Barlai et al. 2017: 108).

The situation was different in Austria, a country which is at the physical crossroads between eastern and western Europe. Austria has historically faced many immigration challenges, driven by the industrial revolution, the dissolution of the Habsburg Empire, the two World Wars, the post-World War II labor shortages, the breakup of the Eastern Bloc, and the massive recent migration from Syria (Jandl, Kraler, 2003). The 2015 refugee crisis put Austria at the epicentre of the European asylum debate (Barlai et al. 2017, 2017: 39). Even though the country had a long history of being a bridge-head for migratory flows to Western Europe, the “increasing influx of refugees since the summer of 2015 has led to disparate political reactions by Austria’s political system, by its rand Coalition government as well as by civil society” (Barlai et al. 2017: 98).

For a while in 2016 and 2017, it appeared that populism would likewise engulf Western Europe (Lilly et al. 2011: 145). In Austria, Norbert Hofer, the presidential candidate of the far-right Freedom Party (FPÖ), campaigned on anti-immigration themes and appealed to populist sentiments (Smale, 2016). In 2015, roughly 90,000 migrants settled in Austria (Figure 8). Hofer’s key message during his presidential election campaign was to restrict and control immigration because, according to him, Angela Merkel made an error in 2015 when she opened the German borders to refugees. He promised to try and curb further immigration to Europe and also reportedly promised to deport Muslims (Martin, 2019).

14 Figure 8. Asylum applications 2006-2015. Source: Report by the Migration Council: 2016: 18

Hofer additionally pushed for repatriating the region of South Tyrol, which was once part of the Austro-Hungarian empire and now sovereign Italian territory. Hofer proposed the idea in a 2015 speech and has since backtracked saying that his only intention was to make it possible for those living in the region to have dual Italian-Austrian citizenship. He also proposed reintroducing border controls at the Brenner Pass in order to make it more difficult for refugees to cross the border, 21 years after customs and immigration posts were removed (Giuffrida, 2016). He also released a campaign poster at the time that featured his head in profile, looking upwards towards the light, with a the slogan in red bold font reading: “Deine Heimat braucht dich jetzt”, meaning “Your homeland needs you now” (Figure 9). Moreover, Hofer supported the open-carrying of firearms and was openly seen holding a 9mm Glock gun with him on the campaign trail. Speaking on these issues, he expressed understanding for the rise in weapon sales in Austria, "given the current vulnerabilities," and says that firearm ownership is a "characteristic result" of migration (Martin, 2019, December 4).

15 Figure 9. Presidential elections in Austria, Political poster, used for print and digital campaigning, March 14, 2016. Retrieved on June1, 2020 from https://www.fpoe.at/

Hofer lost the 2016 presidential election, although with strong numbers. Hofer got 42,2% while his opponent A. van der Bellen recieved 53,8% of the vote (Gavenda, Umit, 2016: 420). In the 2017 German elections, a somewhat different and dramatic set of results occurred in response to the migrant crisis. The election delivered a dramatic electoral decline of the two traditional main parties, the Christian Democrats (CDU/CSU) and the Social Democratic Party (SPD), who had governed Germany in a ‘grand coalition’ government since 2013. (Dostal, 2017: 589). The decline was largely influenced by a strong domestic objection to the government’s policy of accepting more than a million immigrants in 2015, which in turn raised serious questions about law and order, national identity, and the integration of Muslims into German society (Lilly et al. 2011: 145).

True Fruits then took the views from Hofer’s nationalistic presidential campaign platform and released their controversial advertisement after a year of presidential campaigning in Austria, and one month before the elections in Germany. The ads created a huge public debate, especially on social media.

16

3. Literature review

3.1. Key Themes in German Advertising

3.1.1. Patterns of Racialization in Colonial Imagery

True Fruits used some of the colonial imagery in their advertisements in 2017. While presenting a black bottle with the slogan ‘It rarely crosses the border’, it is suggesting a direct connotation to migrants, coming to Austria. To understand the roots of colonial imagery, and how it developed over the time, I present a brief review of it.

German visual culture in the nineteenth century offered a mélange of early styles of racial otherness imposed upon the form of black figures (Ciarlo, 2011: 255). The notion of adorning a product with an illustration, of fusing commerce with images, first emerged in Germany curiously enough, intertwined with elements that many have termed colonial, using the broadest sense of the word (Ciarlo, 2011: 6). Pioneers of German commercial culture looked overseas, to exotic lands, to exotic peoples, to the commercial cultures of other colonizing nations, and (eventually) to their “own” colonies. (Ciarlo, 2011: 6). Caricatures of black figures began appearing in the advertising of most nations that were colonial powers (and many that were not) and are seen to reflect a European popular culture defined by a diffuse sense of racial identity - if not outright racism (Pieterse, 1992).

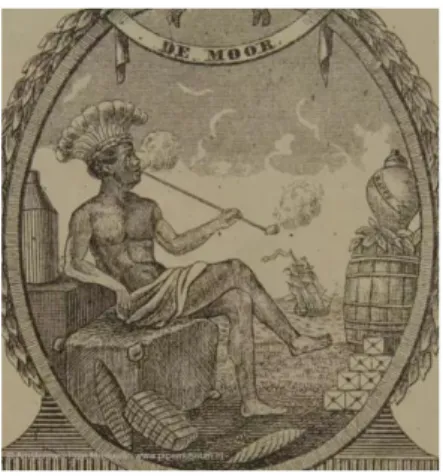

The broad arc of the visual commercial culture of race in Germany can be represented by the four following images. The first is a so-called Tobacco Moor (Tabakmohr) from the second half of the nineteenth century (Figure 10). The second, is a trademark for cacao from 1900 (Figure 11). The third is a soap advertisement; its illustration playing upon the old German adage about the futility of trying to “wash a moor white” (Figure 12). Finally, the Sarotti Moor, a brand from a popular Berlin chocolate manufacturer in the second decade of the twentieth century (Figure 13). At first glance, all of these images might seem broadly similar: each is an illustration used in some sort of mercantile setting, and each falls under the same descriptive rubric—“the moor”— a term denoting blackness and which holds a long history and a dense web of associations (Ciarlo, 2011: 5).

17 Figure 10. Tobacco Moor (Tabakmohr). Source: Amsterdam Pipe Museum. Retrieved on 1 August, from http://pipemuseum.nl/index.php?hm=4&dbm=1&pkl=96&wmod=lijst&startnum=840

Figure 11. Trademark for Cacao. Source: Freiburg Postcolonial Photo Gallery. Retrieved on 1 August, from http://www.freiburg-postkolonial.de/Seiten/Mohren-Stereotyp.htm

Figure 12. A Soap Advertisement. Source: Freiburg Postcolonial Photo Gallery. Retrieved on 1 August, from http://www.freiburg-postkolonial.de/Seiten/Mohren-Stereotyp.htm

18 Figure 13. Sarotti Moor. Source: Freiburg Postcolonial Photo Gallery. Retrieved on 1 August,

from http://www.freiburg-postkolonial.de/Seiten/Mohren-Stereotyp.htm

The logos in the nineteenth century used to illustrate two very different historical phenomena — the rise of modern advertising culture and the subjugation of colonized peoples (Ciarlo, 2011: 3). Such artistry lent a bit of local colour to the displays, but sometimes the local colour was tainted with colonialist ideology (Ciarlo, 2011: 23).

3.1.2. German advertising and politics in 20th century

True Fruits advertisements are politically and socially sensitive. They use ongoing topics to increase the dialogue within the audience. To gain an understanding how political advertisements got into German commercial industries from historical point of view, the main milestones will be presented in following. Historians view World War I as a watershed moment in modern advertising because it introduced new visual propaganda strategies and expressionist and other art forms that thrived on shock value arose from it (Ward, 2001: 93).

Twentieth-century Germany stood at the forefront of international advertising culture. There were 80 million German speakers, the largest language concentration in Europe which provided good markets for the country’s industrial economy (Grazia, 2007: xiii). The disquieting reality was that the United States, not Germany, was the force driving the internationalization of advertising (Grazia, 2007: xiv). As a young nation unencumbered by the ballast of tradition, America represented a land of seemingly unlimited opportunity, the epitome of utilitarian

19 efficiency and technological innovation (Swett et al. 2011: 21). With America’s growing economic and cultural influence after World War I, Europeans increasingly projected their hopes and fears, which in many respects served as an embodiment of the challenge posed to European societies by modernity (Swett et al. 2011: 21). Additionally, nationalistic representation was also a big part of American advertising. This growing obsession with America commingled with specific attempts to work through the legacies of German authoritarianism. Cultural pessimists on the right saw American advertising as the harbinger of a cultural catastrophe with its origins in America, the left, particularly in the aftermath of World War II, saw the advertisements as a medium reinforcing culturally debilitating trends, with potentially serious political implications (Swett et al. 2011: 5).

The business of production and advertising in Germany was never far from politics—and, by extension, the state (Swett et al. 2011: 18). To a degree, the omnipresence of state influence reflects Germany’s long tradition of workers and producers looking to the government to protect their interests or, alternatively, being forced into political servitude by the state (Swett et al. 2011: 18). Germany’s dictatorships and democracies have experienced varying degrees of success in mobilizing industry and consumers behind their ideological goals (Swett et al. 2011: 19). While the Nazi state succeeded largely in turning these power blocs into conscripts for its war against Jews and political enemies the German Democratic Republic never enjoyed the same degree of authority with its citizenry. With these two dictatorships as models to reject, West German manufacturers and the government nominally rejected any coercive means of selling images, products, and lifestyles. But political messages and corporate branding together bred a form of social conformity that many observers saw as oppressive and, indeed, as a more subtle form of coercion (Swett et al. 2011: 20). Remarkably, the close relationship between the state and advertising remained largely uncontested despite the succession of failed political regimes (Swett et al. 2011: 20).

20 3.1.3. Nazi Propaganda

To interpret True Fruits intentions, more historical context has to be analysed and presented. The most traumatising German national experience was when Nazis overtook the regime. I grasp on topics and actions which True Fruits could have used in their visual rhetoric. However, it is important to stress that it is a historical context which belongs to German advertising key themes and was not necessarily draw on directly by the start-up.

After the Nazis seized power, the new regime nationalized image-making in all its forms, including advertising (Swett et al. 2011: 9). By establishing a state advertising council in 1933, the government sought to control all aspects of an industry still tarnished by claims of unethical business practices and foreign influence (Swett et al. 2011: 9). The mandate of the Advertising Council for the German Economy was to end any existing advertising debates by regulating everything from who practiced in the industry, to rate scales for tiny classified ads, to the content of ad copy and design (Swett et al. 2011: 9).

Racial others did not play a significant role in advertising in Nazi Germany (Swett, 2014: 13). Hate-filled caricatures of Jews, Blacks, and Slavs were common staples of Nazi-era political propaganda, while images of black servants already had a long history in Germany’s visual landscape (Swett, 2014: 13). While minorities had always been marginalized in German society, their ostracism became state policy after 1933 (Swett, 2014: 13). The “purification” of “German ads” was just one of the myriad ways in which racism was interwoven into the fabric of daily life in Nazi Germany. “Honest” business practices were racially circumscribed (Swett, 2014: 15)

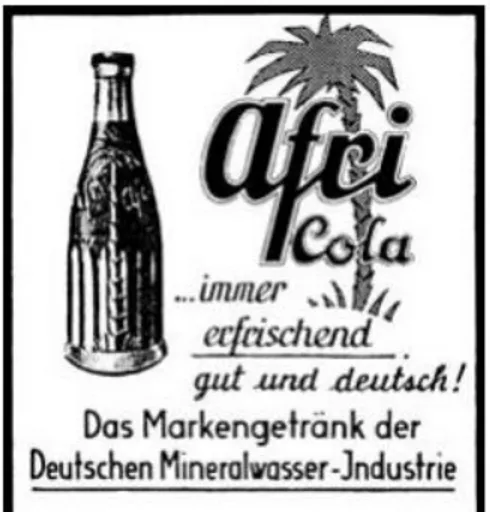

Holm Friebe, whose ideas about branding continue to influence German advertisers, shows how the practical world of selling products was always framed by cultural debates about mass psychology and political propaganda (Friebe, 2007: 78). Like Friebe’s piece, Jeff Schutts’s essay on Coca-Cola under the Nazis (Figure 13) also demonstrates clearly how advertisements in the public sphere were in the service of both corporate and political persuasion (Schutt, 2007: 151). The Nazis introduced at once a communitarian and an ethnically exclusive vision of advertising’s role in society, and Schutts explores the impact of this vision

21 through the racial politics of the soft drink’s marketing strategies. (Swett et al. 2011: 18)

Figure 14. “Afri-Cola . . . always refreshing, good and German!” November–December 1938 Source: Swett et al. 2011: 166

However, it is nearly impossible to evaluate how individual consumers interpreted the ads they saw (Swett, 2014: 7). Judging how advertising messages were received is particularly difficult in the pre-1945 era before consumer surveys and other forms of testing “success” became common in Europe (Swett, 2014: 7). Instead, as David Ciarlo entreats, we need to look for “a pattern in a down-pour.” (Ciarlo, 2011: 17). In other words, by viewing large array of contemporaneous images we can begin to see certain patterns that reflect common ways of “crafting and of seeing imagery” from a time period. Surely there are always individuals (among advertisers and among consumers) who interpreted imagery in wholly unique ways, but it can be presumed by looking at the coherence among ads for different products that there were patterns of representation that became so common they constituted a “visual hegemony.” (Swett, P. 2014: 7)

No doubt about it: the Nazi regime well understood that yet one other means to enhance its totalitarian grip lay in re-establishing political hegemony over the slippery terrain of the commercial public sphere (Swett et al. 2011: xvi). Advertising had a central role to play in a market that pretended to modify the class-divisive nature of cultural goods and distribute scarce resources by rewarding and depriving consumers according to their place in the Volksgemeinschaft’s hierarchy of utility and race (Swett et al. 2011: xvi). The effects on any number of levels were catastrophic, spelling the eclipse of the

22 persecution, exile, and death of Jewish artists and an aesthetics favouring populist realism spelled the death of German forward thinking modernism, the restoration of the Gothic script, the end of Germany’s superiority in experimental typography (Swett et al. 2011: xvii)

German companies and the Nazi Werberat (Advertising Standards) were able to save advertising from itself. They convinced Germans that buying and selling foreign imports were not threats to unity, but in fact, ways to belong to the community. Even during the war, ads played a reassuring role by reminding Germans of products they associated with peacetime and by offering strategies to deal with hardship (Swett, P. 2014: 7).

3.1.4. Visual Nationalism

One of the topics, analysed in this thesis, is German flag presentation in three #jetztösterreichts advertisements. Usually, representation of the flag has an intention or some specific meaning. My interest lies of what has been written about it in previous literature and how True Fruits used national flag in their visual rhetoric.

The visual representation of a nation’s flag out of place and out of context has nationalistic connotations. V.R. Dominguez presents an analysis of the subject in her paper “Visual Nationalism: On Looking at “National Symbols” about the 1988 exhibition of the work of Yitzhak Yoresh, a graphic designer and animator who ‘’uses the flag as an impressionistic landscape.” (Dominguez, 1993: 451)

Entitled “Works on the Theme of the Israeli Flag,” the exhibition presented two- and three-dimensional creations which clearly played with the flag itself, its component elements, and the reactions of visitors. The artist altered different elements of the flag’s form, colour, size, composition, material, and technique “to express ideological, political, social and economic ideas” (Yoresh, 1988). Yoresh himself says: “My approach thus represents not disrespect for the flag, but rather an examination of the character and potential of this visual sign of identity, which has both local and universal significance.” (Dominiguez, 1993: 454).

23 Figure 15. The Flag of Israel. Source: Israel Museum Information Center for Israeli Art,.,

Retrieved on August 1, 2020 from https://museum.imj.org.il/artcenter/newsite/en/

Don Handelman and Lea Shamgar-Handelman’s essay (1990) suggests another way of looking at national symbols. The Handelmans discuss the interaction of separate “aesthetic” and “ideological” elements in national symbolism. Three objections constitute the argument in their analysis. First, they object to the dominance of questions of political power in contemporary cultural scholarship. Second, they object to the heavy emphasis on discourse and discourse analysis in these same circles, including anthropology. And third, they object to the functionalist premises they identify in much of the work on tradition, state symbolism, and the rise of the modem nation-state (Dominguez, 1993: 453). Even though the Handelmans suggest one way of looking at national symbols, Yoresh plays with figures and elements in ways that could well invite their kind of analysis but ultimately rejects their insistent separation of the “aesthetic” from “the ideological” or discursive. Visual representation of the national flag which “focuses on social/political/economic processes that continually define sameness

24 and difference, the included and the excluded, the fault lines within and without” (Dominguez, 1993: 453).

3.1.5. Controversial Advertisement Framework

True Fruits selected politically and socially sensitive topics such as refugees, boarder politics, racialization, and nationalism in their #jetztösterreichts campaign. The reason was to encourage the dialogue within the audience and to spread the campaign viral in German speaking countries. I draw on controversial advertisement framework in this thesis as my main argument how True Fruits strategically chose to communicate about their products in new market country Austria. Therefore, I present a history and a concept of controversial advertisements.

The competition to gain consumer attention is fierce, and brands have to deploy new strategies to ‘conquer’ their customers (Thorson, Rodgers, 2012: 10). One of the methods companies have been using is employing controversial advertisement practices. There are several other monikers for this specific type of marketing: “Schockvertising”, “Provocative advertisement” or “Woke advertisement”. This strategy is mostly used in Social Marketing campaigns, by addressing social issues and thus receiving publicity attention and making newspaper headlines. Shock advertisement can be classified as a type of post-modern advertising which is characterised by “rapid succession of visually appealing images, repetition, high volume, mood-setting and is much more symbolic and persuasive than informative” (Cortese, 1999: 7).

The history of controversial advertisements dates back to the 1980s when Luciano Benetton released provocative adverts that caught the attention of the public in a new and attention-generating way. Ganesan (2002) argues that “unlike most advertisements which cantered around a company`s product or image, Benetton`s advertising campaigns addressed social and political issues” instead of their product (Ganesan, 2002). Creating advertising that confronted important issues of the time, “Benetton coupled arresting images with bold social messaging in a way that commanded consumer attention and served to markedly increase public awareness of the brand” (Sis International Research, Retrieved on 1 August, 2020).

25 Benetton’s United Colors 1982 campaign was considered shocking to many, it depicted two young women wrapped in a blanket, clasping hands while holding a baby – all three of different races (Figure 15). In doing so, Benetton brought this new degree of tolerance and a diffusion of homosexual stereotypes to public attention, something that was revolutionary at that time (Sis International Research, Retrieved on 1 August, 2020). Other risk-taking campaigns were Benneton’s advert showing three actual human hearts, side-by-side, labelled ‘white, black, yellow,’ illustrating the sameness of us all beneath the surface of our skin (Figure 15). These were effective campaigns that also pushed socio-political boundaries and helped to move the barometer of acceptance on subjects considered cultural taboo.

However, in an early collaboration with Benetton, Oliviero Toscani photographed two young girls - black and white - together and it was not successful. The idea failed as the white-skinned girl was pictured angelically, and the black-skinned girl was cast in a more demonic light with her hair styled like devil-horns. This perceived perversion of innocence fell flat with the public. Another campaign sought to utilize actual convicts as models, a novel concept, but one that came across as a kind of approbation of violence. Still, despite these setbacks, Benetton continued to raise the bar of controversy, ultimately increasing the brand’s visibility (Holz, 2006: 1).

Figure 16. Successful United Colors of Benetton Campaigns. Retrieved on August 1, 2020 from

26 Figure 17. Unsuccessful United Colors of Benetton Campaigns. Retrieved on August 1, 2020 from

https://medium.com/@yomiadegoke/united-colors-of-benetton-blazed-a-trail-for-diversity-in-fashion-a61746de0517

Holz (2006) draws on Shock advertisement in the research paper “United Colors – United Opinions – United Cultures: Are consumer responses to shock advertising affected by culture? A case study on Benetton campaigns under Oliviero Toscani examining German and English responses” (Holz, 2006). The author argues that shock advertising is affected by culture and offers a qualitative study approach using Benetton’s controversial campaigns in Germany and the United Kingdom. (Holz, 2006: 3).

3.1.6. Representation of Immigration in Visual Culture and the Media All four advertisements of True Fruits relate to immigration in Austria. Analysis of the representation of it in visual culture, explains the focus on rhetoric and messages in the adverts in other studies. I will use the insights which I found to analyse how immigration is presented in the media for my visual analysis part. Over the past two decades, migration has become one of the most decisive socio-political topics worldwide (Lecheler et al. 2019: 691). Kevin Smets and Çiğdem Bozdağ in their article “Editorial introduction “Representations of immigrants and refugees: News coverage, public opinion, and media literacy” presents a study of how refugees are represented in media (Smets, Bozdağ, 2018: 293).They say that “dynamics of representation reminds us that media texts are contextualized constructions rather than objective reflections of reality.” (Smets, Bozdağ, 2018: 294). Also, they show with their study that the existing body of research on media representations of immigrants and refugees indicates established patterns of

27 framing, and a systematic bias in the representation of immigrants and refugees in different contexts.

Another useful study in my research was “Setting the Agenda for Research on Media and Migration: State-of-the-Art and Directions for Future Research” by Sophie Lecheler, Jörg Matthes & Hajo Boomgaarden. The study shows how traditional mass media coverage of refugees and immigrants has changed over time, and how it differs from country to country (Lecheler et al. 2019: 694). The authors offer explanations through their focus on time and space, thereby furthering our theoretical and contextual understanding of the relationship between migration and media.

Cisneros (2008) identifies another metaphor present is popular media coverage of immigration – the “immigrant as pollutant”. The author analyses visual images of immigrants in news media discourse and argues that it can have serious consequences for receiving societies treatment of immigrants as well as the political policies created in response to immigration (Cisneros, 2008: 569). Representations of illegal immigration in popular media, from television shows to news photographs, provide a complex view of the immigrant “problem.” Cisneros (2008) has identified a variety of metaphors that serve as conceptual tools by which we understand immigration and its effect on upon society. Some of these metaphors are the immigrant as invader, as criminal, as a disease, etc. Further, the preceding analysis of recent news media discourse about immigration illustrates another metaphor through which media seeks to articulate this controversy: the immigrant as pollutant (Cisneros, 2008: 590).

The studies of metaphorical and visual representations of immigration helps to create a broader understanding of the metaphors employed in public discourse. However, concern over immigration is evidenced not only in public discourse but also in the large body of scholarship on the phenomenon of immigration, including an attempt to understand how immigration as “problem” is constructed in mass media (Cisneros, 2008: 270).

28

4. Theoretical Framework

4.1. Encoding and Decoding Model

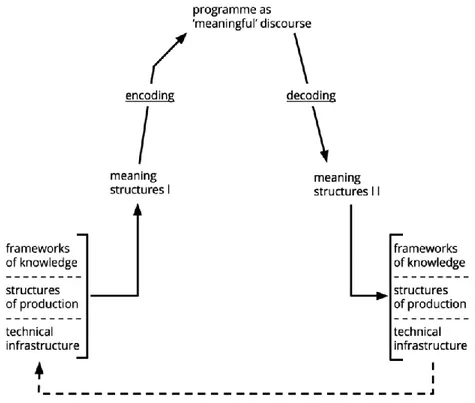

As an empirical framework for studying the interpretation and effectiveness of True Fruits’ controversial advertisements, I employ Hall’s (1973) model of encoding/decoding, which evokes the role of audiences, particularly the diverse and differentiated ways in which they interpret or decode meanings based on individual and group experiences (Hall, 1973). Encoding/decoding thus serves as an epistemological framework for the diverse interpretation of communication: what the sender (producer of the controversial advertisement) intended to convey is not necessarily what the receiver (the audience) perceives of what was communicated (Shaw, 2017: 592).

Figure 18. Encoding and decoding model by Stuart Hall. Source: Encoding/Decoding model, 1973:4

According to Hall, the encoding of a message is the production of the message (Hall, 1973:3). It is a system of coded meanings, and in order to effectively create one, the sender needs to understand how the world is comprehensible to the members of the audience. In the process of encoding, the sender (the encoder) uses verbal (e.g. words, signs, images, video) and non-verbal (e.g. body

29 language, hand gestures, facial expressions) symbols for which he or she believes the receiver (the decoder) will understand (Hall, 1973:5). It is very important how a message is encoded; partially depending on the purpose of the message (Hall, 1973:6).

The decoding of a message is how the audience member can understand, and interpret the message (Hall, 1973:7). It is the procedure of interpreting and comprehending the coded information into an intelligible structure. The audience attempts to recreate the thought by offering inferences to the images thus interpreting the message (Hall, 1973:7). Effective communication is accomplished only when the message is received and understood in the intended way (Hall, 1973:7). However, it is still possible for the decoder to understand a message in a completely different way from what the encoder was trying to convey. (Hall, 1973:8). This is when "distortions" or "misunderstanding" arise from a "lack of equivalence" between the two sides in communicative exchange (Bankovic, 2013).

The encoding/decoding model here refers to the creators of the controversial advertisements (True Fruits) and their audience (responses in social media) in this thesis. Using Hall’s encoding/decoding model I will illustrate how controversial advertisements imbued True Fruits products with political content and how the audience understood the message using CDA. While these meanings could change, the mechanisms do not: which is why a structural analysis remains valid (Williamson et al, 1978: 134).

30 4.2. Visual Rhetoric and Semiotics

Visual rhetoric, as it is employed in the discipline of rhetoric, has two meanings. One refers to the visual images themselves — visual communication that constitutes the object of study (Foss, 2004: 141). The second meaning references a perspective or approach rhetorical scholars adopt as they study visual rhetoric. (Foss, 2004: 141). Together, these two senses of the term point to the need to understand how the visual rhetorically operates in contemporary culture (Foss, 2004: 141). Visual rhetoric, as communication data suggests, helps to expand the understanding of the different ways in which symbols inform and define the human experience (Foss, 2004: 143). Thus, it constitutes a call to expand rhetorical theory, making it more inclusive by encompassing visual as well as verbal symbols. (Foss, 2004: 145)

Differing from visual rhetoric, in semiotic theory a sign is anything that represents something else — that is, a sign is representative of an object or concept (Hoopes, 1991: 141; Eco, 1986: 15). The Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, known as the father of European semiotics, expressed this relationship in his course on General Linguistics (1966) as the marriage of sound and image — the signifier (Sr) — and the concept for which it stands (the content) — called the signified (Sd) (Saussure, 1966). The signifier is the form in which content is expressed — whether word, sound, picture, smell, or gesture (Saussure, 1966).

“In advertising, the signification of the image is undoubtedly intentional; the signifieds of the advertising message are formed a priori by certain attributes of the product and these signifieds have to be transmitted as clearly as possible” (Barthes, 1977: 152). Barthes deconstructs a “Panzani” advertising image and extracts the types of messages contained within it in order to illustrate the rhetoric of the objective image. “If the image contains signs, we can be sure that in advertisement these signs are full, formed with a view to the optimum reading: the advertising image is frank, or at least emphatic” (Barthes, 1977: 153). When looking at the overall sign of the advert, three types of messages are sent: the linguistic message and two types of iconic message (Barthes, 1977: 153). Within the linguistic message, which is the caption, the copy, or the title, are two types of messages identified: the denoted message, which is the literal meaning of the labels on the product and the connoted message, which is the socio-cultural and

31

‘personal’ associations drawn from the label or text (Barthes, 1977: 155). The

viewer derives the message from the visual connotations or suggestions provided by the chosen objects, their arrangement, their signifiers, and what they signify (Barthes, 1977: 156).

4.3. Social Representation

A representation is something, usually an image, that stands for, denotes, or symbolizes something else. (Smith, et al., 2004: 117). A crucial consideration for the analysis of representation is the relationship between the sign and the object (Smith, et al., 2004: 117). In this thesis, an international representation of the symbols and words are crucial, so the “choice of symbols must be culturally acceptable to the audience, as well as the designer” (Smith, et al., 2004: 117). “Social representations […] concern the contents of everyday thinking and the stock of ideas that give coherence to our religious beliefs, political ideas and the connections we create as spontaneously as we breathe” (Höijer, 2011:6). According to the pioneers of this theory, social representations “make it possible for us to classify persons and objects, to compare and explain behaviours and to objectify them as part of our social setting.” (Höijer, 2011:8). A social representation is a system of values, ideas, and practices with a twofold function: first, to establish an order which will enable individuals to orientate themselves in their material and social world and to master it (Moscovici 1973: xiii). Second, to enable communication to take place among members of a community by providing them with a code for social exchange and a code for naming and unambiguously classifying the various aspects of their world and their individual group history (Moscovici 1973: xiii). With the epithet “social”, Moscovici seeks to emphasize how representations arise through both social interaction and communication between individuals and groups.

To wrap it up, social representations are about the processes of collective meaning resulting in common cognitions that produce social bonds uniting groups, organisations, and societies.

32

5. Research Questions

True Fruits is known in Germany and Austria for being a provocative start-up, releasing advertisements about contemporary social issues. I want to analyse one of their advertisement campaigns, published in 2017. Therefore, my research problem is:

True Fruits Advertisements in Austria in 2017: the cause for the advertisement and effect on the audience

To this end, this study seeks to investigate the intent of the visual rhetoric contained in the controversial advertisements from 2017. Second, the aim is to examine consumer reactions to the advertisements on social media.

Research Question

To narrow down the outcome of my research, I establish one major and three subsidiary research questions. As explained in N. Blaikie and Jan Priest’s book, “one research question is necessary to address the research problem and subsidiary questions will include those that deal with background information or issues […] while are not absolutely central to the project” (Blaikie, 2019: 92). Following another scholar, D. Layder, I was able to specify my topic-questions. “Unlike problem-questions which are general in nature, topical questions concern specific issues about the topic or the area of research interest” (Layder, 2013: 10-12).

My main research question:

What happened on social media after True Fruits published their controversial advertisements in 2017?

My subsidiary questions:

• What key German advertisement themes emerged from True Fruits’ published advert campaign?

• What social and political issues were present in True Fruits advertisement campaign?

33 • What types of audience discourse appeared on the different social media

34

6. Methodology

The methodology behind this thesis follows a “continuously unfolding process” from inception to conclusion, as many different strategies were considered, deployed, and then disregarded (Layder, 2013: 12). Mixed methods – visual analysis and CDA - were used to analyse what happened on social media after True Fruits published their controversial 2017 advertisements. By answering subsidiary questions, the response to the main research question will be presented.

6.1. Visual Analysis

As Stuart Hall states, in representation, the visual image takes centre stage and “images visualize (or render invisible) social difference” (Hall,1998: 226). Hence, one of the subsidiary questions of this study is to analyse what key German advertisement themes emerged from the True Fruits advertisements. I argue that a visual approach is suitable for looking into the representation of racialisation, nationalism, and border politics.

To answer the questions of how True Fruits sparked a discussion on social media and what they encoded in their four advertisements as well as what social and political issues were present in True Fruits advertisement campaign, visual analysis is required. Barthes’ visual analysis tool helped to frame a system for analysing the images. The method of unfolding three layers of meaning from the visuals is carried out: the linguistic message, the denoted image, and the rhetoric of the image.

I will employ a linguistic and semiotic approach for understanding how visual representations convey meaning. Barthes suggests the system of meaning as a three-level system. The first level he calls a linguistic text which is a denoted or connoted message. The second is a symbolic message which is a literal message without a code and a connoted image “what is called the semantic fields of our culture” (Hall, 1998: 38). The third level suggests to analyse a connotated message of the text.

35 In this regard, the theoretical part of visual rhetoric and semiotics will be employed to analyse the meaningful content of the True Fruits advertisement campaign.

6.2. Critical Discourse Analysis on Social Media

To answer the subsidiary question of how the social audience responded to True Fruits’ advertisements, CDA is used. As it is qualitative research, an inductive research approach is the most appropriate method. “An inductive strategy of linking data and theory is typically associated with a qualitative research approach” is mentioned by Bryman and Bell (2015). I collected the user responses data from three social media channels (Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter) with a software program called “NVivo”. Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter were chosen because they were all used for True Fruits’ “jetztösterreichts” campaign.

To understand, how many people on social media were possible to reach, I present general information about the scope of True Fruits’ audience on social media. The numbers are retrieved on 28 August 2020, so it might vary from the numbers when the campaign was released but seeing the comments and impressions, the amounts should have been big enough for a start-up to understand and predict the impact of the campaign. As presented in Table 1, True Fruits has enough subscribers for the social media campaign to go viral in both target German-speaking countries: Austria and Germany. In 2016, 8.63 million people living in Austria (Country Health Profile, 2017) and 82.66 million people in Germany (Worldometer, retrieved on 28 August, 2020). Not to forget, this is just a part of a digital campaign, people were seeing posters on the streets, newspapers, and magazines, however, this part is not a scope of this study. In this particular campaign, I analyse only the comments under True Fruits posts with hashtag “jetztösterreichts”. This way made it comprehensive to systemize and review all the comments written for this campaign. In every social media post the company used the same picture of the campaign, with a brief title “We show bottles in Austria” (Figures 19-21). Only the comments under True Fruits will be analysed to keep the consistency of the posts which mostly reached other social media users. The data in Table 1 shows that most of the comments are on Facebook, that is why material analysed through the CDA approach will be selected mostly from there because it got the most attention virally. Other social

36 media channels were used accordingly and there were discussion tendencies similar to Facebook. To represent every social media channel, a least one comment will be taken from each of the channels.

Facebook Twitter Instagram

Subscribers 545 905 5 203 137 000 Jetztöstereichts Impressions 17 002 61 4 026 Jetztösterreichts comments 1 700 12 229 Jetztösterreichts shares/retweets 388 23 n/a

Table 1. Scope of Audience Engagement on True Fruits Social Media. Retrieved on 28 August, 2020

37 Figure 20. True Fruits post #jetztösterreichts on Facebook. Source: www.facebook.com

38 To make transparent, of how the comments were selected for CDA analysis, I would like to explain it in depth. After qualitatively reviewing the comments, one by one, I categorized four main groups of what opinion the audience has. Commenters were talking mostly about nationalism, border policies, racism, and a campaign as a marketing strategy. However, the opinions were varying from positive to negative. I decided to select all the presented groups with negative and positive comments, with the intention behind showing that there was a lot of variation. After this step, I did a CDA analysis and looked at it through Fairclough’s lens in text, processing, and social analysis levels to present the results reliably and independently.

CDA is a rapidly developing field in the social sciences and it regards discourse as ‘a form of social practice’ (Fairclough & Wodak, 1997: 258). CDA considers the context of language use to be crucial to discourse (Wodak, 2001). It may be described as an approach claiming that “social practices”, namely the cultural and economic dimensions are significant in the creation and maintenance of power relations in discourse (Baig, 2013: 127). In other words, CDA is a discipline that views discourse as constituting social practice and at the same time being constituted by it (Wodak 1999:7). According to Wodak, the aim of CDA, unlike traditional forms of discourse analysis that are concerned with the forms and features of texts, is “to unmask ideologically permeated and often obscured structures of power, political control, and dominance, as well as strategies of discriminatory inclusion and exclusion in the language in use” (1999: 8)

One of the most renowned discourse analysts, Norman Fairclough, presented a three-dimensional model of CDA in his work “Language and Power” which was published in 1989 (Figure 14). This model is supposed to be an interdisciplinary approach to the study of discourse, for it views ‘language as a form of social practice’ (Fairclough 1989: 20) and focuses on how social and political dominance is exercised in discourse by ‘text and talk’. Moreover, the three-dimensional model highlights the processes of the production and reception of a ‘discourse fragment’ in a particular context. (Fairclough 1989: 20)

39 Figure 22. Fairclough's Framework for CDA (1995: 59)

According to his three-dimensional model, Fairclough identifies three dimensions to CDA. The first dimension represents the discourse fragment, a “text” that could be any object of analysis, including verbal, visual, or verbal-visual texts (Baig, 2013: 129). The second dimension of ‘discursive practices’ can be described in terms of production and reception of a ‘text’ in a particular ‘context’ (Baig, 2013: 129). The context is ‘situational as well as intertextual’ (Baig, 2013: 129). The situational context deals with the time and place of text production whereas the intertextual context is related to the producers and receivers of the discourse and the third dimension of discourse could be described as ‘power behind discourse’ or as ‘social practices’ functioning behind the entire process and governing the power relations in discourse (Baig, 2013: 129). Among the three dimensions of Fairclough’s model, each dimension requires a different type of analysis: for the first dimension ‘text analysis’ or description, for the second dimension ‘processing analysis’ or interpretation, and for the third dimension, it is the ‘social analysis’ or explanation (Baig, 2013: 129). All dimensions are inter-dependent and therefore it does not matter with which kind of analysis one begins with as they are “mutually explanatory” (Janks 1997: 27).

The “NVivo” program helped me extract data from three social media networks, and it was useful in organizing and preparing the data so that I could make comparisons and analysis. As Coffey suggest, I think that “no single software package can be made to perform qualitative data analysis in and of itself” (Coffey,

40 Atkinson, 1996: 166). It was rather just the tool which helped me during the preparation phase, the analysis, selection, and interpretation are my own. This study demonstrates that a semiotic and rhetoric analysis of visuals can be tested against viewer responses and the message intended by the creators to identify key patterns of meaning reception and construction.

6.3. Sample

As qualitative research does not aim to be representative, a small, purposeful sample of the analysis was selected, “precisely because the researcher wishes to understand the particular in-depth, not to find out what is generally true of the many” (Merriam, 2009: 223). I chose to analyse the “jetztösterreichts” campaign which included four advertisements and rhetorical statements from True Fruits. For the user responses, I chose representative user comments on social media as the sample for the CDA. The user responses were taken from Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. I reviewed all the comments and selected those, which revealed main opinions from the audience which I was able to systemize into several categories: nationalism, border politics, racism, and a campaign as a marketing strategy. To understand from which country the comment is coming from, only the place of residence is taken from the user’s profile information who commented on True Fruits post. The study of audience responses helped me to answer my research question “What types of audience discourse appeared on the different social media platforms as a result of the True Fruits campaign?”.

6.4. Methodological reflections

In order for research to be academically relevant, the produced knowledge must be believable and trustworthy (Keller, 2018: 35). This involves reflecting upon the legitimacy and quality of the study. Merriam summarizes strategies that help to ensure that a qualitative study is credible and transferable as well as dependable (Merriam, 2009: 229). To meet these requirements, this research project: 1) provides a detailed account of the method, procedures for data collection and analysis, and decision points in carrying out the study; 2) aims to present rich, thick descriptions that are sufficient to contextualize the study in a way that future researchers can “determine the extent to which their situations match the

41 research context, and, hence, whether findings can be transferred” (Merriam, 2009: 229); 3) and it reflects critically on the position of the researcher regarding “assumptions, worldview, biases, theoretical orientation, and relationship to the study that may affect the investigation” (Merriam, 2009: 229).

7. Ethics

To examine how did I deal with ethical issues in my research, I will review a few key ethical problems presented by Norman and Priest (2011). First, I raised the question about privacy and publicity while doing online research. The resources, services, and activities on the internet present social researchers with novel opportunities and challenges when compared to traditional ‘offline’ social research (Norman, Priest, 2011:266). Second, in cyberspace, private and public spaces overlap, posing challenges to the researcher regarding the extent to which individual privacy must be protected (Keller, 2018: 37).

In the following points, I will discuss the most important ethical aspects, while doing internet research:

• Participant Identity – Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook are public social networks where everything that is published can be seen and exported as a dataset. During my research, I have noticed that Twitter is stricter when exporting data using scraping or data mining resources. Extracting the data from Facebook and Instagram was rather uncomplicated and technically easy. However, I do not use or specify the name, age, sex, or any other information used by the individuals who commented on the True Fruits campaign. I use only the country which is shown in the user’s profile to get more context on where the comment was written.

• Participant Consent – everyone, registering to Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter, signs a data privacy agreement where it is mentioned that the data can be used or sold to the aforementioned companies. As Facebook states on its data privacy page: “We use the information we have (including from research partners we collaborate with) to conduct and support research and innovation on topics of general social welfare, technological advancement, public interest, health and well-being” (Facebook Privacy, retrieved on 11 June, 2020). Twitter, on its data policy

42 page, states, that “Twitter is public, and tweets are immediately visible and discoverable for everyone worldwide” (Twitter Privacy, retrieved on 11 June, 2020).

• ID and data security – I did not use any other information from the users of Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter, except the comments posted.

• Datastores – I used “NVivo” software to export the data from specific posts on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. “For manageable volumes of data, traditional logics, methods, and tools can be applied to scan and analyse aggregate data in order to develop answers to a study’s research questions” (Norman, Priest, 2019: 269).

Not to forget, my researcher’s position needs to be critically reflected upon. “In a qualitative textual analysis, the researcher takes on an active role as she/he brings her/his interpretive strategies to her/his work” (Brennen, 2012, p. 206). Everything that is presented in the visual analysis is my views and statements. Also, I had a personal hand when reading social media comments as datasets, selecting the comments that I wanted to interpret. It is important to mention is that I, as a researcher, was dealing with socially contentious and challenging topics, where both the presentation and the interpretation is subjective.

All in all, I can say that I solely used the comments from Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter and did not identify the users by name, age, sex, or other personal related information. Therefore, I can state that I did not violate any official privacy rules. However, it must be reiterated that the presentation of topics such as immigration, when presented in advertisement form, are socially sensitive. Especially, when a lot of discussions and political debates surround immigration, and how the business world contributes to them.

43

8. Presentation and Analysis of the Results

8.1. True Fruits Campaign Visual Analysis: Encoding 8.1.1. Linguistic and Semiotic Meaning

The images of the True Fruits advertisement immediately yield first messages whose substance is linguistic:

• It rarely crosses the border. • Your homeland needs us now. • Even more bottles from overseas. • You cannot choose brown with us!

The linguistic messages presented by True Fruits can be understood directly as the first layer. In the first slogan, the bottles of smoothies are exported from Germany and imported to Austria. As it does not happen often – that is why it rarely “crosses” the border between the two countries. In this way – Germany self-depreciates itself. The second slogan portrays True Fruits as the desired product - in the summer when the campaign was released, people needed True Fruits smoothies to refresh and enjoy the warm weather. The third slogan contains a strain of self-irony. True Fruits is commenting on the high amount of consumer imports in Austria and ironically notes that even more imports are coming to market. The fourth sentence is the most difficult to interpret without context. One can see that there are no brown bottles in the visualisation. Therefore, it leads to the discussion that there are twofold meanings in the advertisements: both denotational and connotational as Barthes` visual analysis model suggests. In fact, these messages can themselves be further broken down into different meanings.

Putting aside the linguistic message, we are left with the pure images (even if the slogans are part of it). These images straightaway provide a series of signs. First, the idea what we have in the scene represented are bottles in the colours of black, red, and yellow. Every signifier is placed upon a white background. Some of the words are written bigger than others. In a small text at the bottom, the reader can see another text suggesting the viewer check out their campaign on social media platforms. The advertisement stands in redundance with the connoted sign of the

44 linguistic message – the advertisement talks about bottles. As will be seen more clearly in a moment, all images are polysemous; they imply, underlying their signifiers, a "floating chain" of signifiers, the reader is able to choose some and ignore others. Polysemy poses a question of meaning and this question always comes through as a dysfunction. The text helps to simply identify the elements of the scene and the scene itself; it is a matter of a denoted description of the image. Concerning the liberty of the signifiers of the image, the text thus has a repressive value and we can see that at this level it is where the morality and ideology of society are invested above all. When it comes to the "symbolic message," the linguistic message no longer guides identification but rather an interpretation, constituting connoted meanings.

8.1.2. Racialisation

Two of the released slogans suggest the topic of racialisation in the advertisements. Different skin colours are displayed in the advertisements as coloured versus brown, white versus black. The slogan "Even more bottles from overseas" offers a room for interpretation that even more migrants (keeping in mind that in German “Flaschen” (bottles) has another meaning - losers) are coming to Austria from abroad. Some of these “bottles” are already in Austria - from wherever. True Fruits here is using this comparison between migrants and losers. This looks back at the history of immigration to Austria, which was always a physical crossroads between eastern and western Europe. However, the 2015 refugee crisis put Austria at the epicentre of the European asylum debate, and Austrian´s right-wing politicians reacted. True Fruits, essentially used the same rhetoric as they did. One could think that these political views are coming from a small German start-up, but with knowledge of the political context in Austria and Germany, it is possible to see that True Fruits were using their advertising space for commenting on what was happening in the political sphere in neighbouring Austria.

Together with the visualisation of the black, red, and yellow bottles, it creates a clear link to people with different skin colours coming to Austria. The headline "You can't choose a brown with us” is politically suggestive. As the German term wählen has the dual meaning of to vote and to choose, the slogan can be