DR. BIRGITTA HÄGGMAN-HENRIKSON (Orcid ID : 0000-0001-6088-3739)

Article type : Review

The Impact of Orofacial Pain Conditions on Oral Health Related Quality of Life: A Systematic Review

Ibrahim Oghli1,2,3, Thomas List1,3,4, Naichuan Su5, Birgitta Häggman-Henrikson1,3

Short title: Impact of orofacial pain on QoL

1 Department of Orofacial Pain and Jaw Function, Faculty of Odontology, Malmö

University, Sweden

2 Department of Oral Basic Sciences, Taibah University, Medina, Saudi Arabia 3 Scandinavian Center for Orofacial Neurosciences (http://www.sconresearch.eu/) 4 Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Skåne University Hospital, Sweden

5 Department of Social Dentistry, Academic Center for Dentistry Amsterdam (ACTA),

University of Amsterdam and VU University Amsterdam, Amsterdam 1081LA, The Netherlands.

Corresponding Author:

Dr B Häggman-Henrikson, Department of Orofacial Pain and Jaw Function, Malmö University, 205 06 Malmö, Sweden. E-mail: birgitta.haggman.henrikson@mau.se

Acknowledgement

The authors report no conflict of interest. No source of funding was received for this study. Assistance provided by Stella Sekulic, Mike T. John and Nicole Theis-Mahon with the electronic literature search, screening of abstracts and assessment of full text articles was greatly appreciated.

Author contributions

IO, NS and BHH contributed to concept, study design, full text assessment and risk of bias assessment. TL contributed to the concept, study design and interpretation of results. All authors critically revised the manuscript and provided final approval before submission.

Abstract

Pain in the orofacial region is one of the most common reasons for patients to seek dental treatment. Oral health related quality of life (OHRQoL) can be affected not only by pain, but also by other oral disorders. Four main dimensions, Oral Function, Orofacial Pain, Orofacial Appearance, and Psychosocial Impact, have been suggested to cover different areas of OHRQoL. The aim of this systematic review was to map the impact of orofacial pain conditions on the Orofacial Pain dimension of OHRQoL (PROSPERO registration: CRD42017064033). Studies were included if they reported Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP) mean or median domain scores for patients with odontogenic pain, oral mucosal pain/Burning Mouth Syndrome (BMS), third molar extractions or

temporomandibular disorders (TMD). A search in PubMed (Medline), EMBASE, Cochrane, CINAHL, and PsycINFO on June 8, 2017, updated January 14, 2019,

combined with a hand search identified 2,104 articles. After screening of abstracts 1,607 articles were reviewed in full text and 36 articles were included that reported OHIP-data for 44 patient populations including 5,849 patients. Typical Orofacial Pain impact for all four conditions (odontogenic pain, oral mucosal pain/BMS, pain after third molar

extractions and TMD) was between 2 and 3 on a 0-8 converted OHIP-scale with the highest reported impact for pain after 3rd molar extractions. This review provides

standardized information about OHRQoL impact from four orofacial pain conditions as a model for the Orofacial Pain dimension. The results show moderate impact for the pain dimension of OHRQoL in patients with common orofacial pain conditions.

Keywords: Burning Mouth Syndrome, oral health, facial pain, patient reported outcomes, quality of life, Temporomandibular Disorders

Background

Pain in the orofacial region is one of the most common reasons for patients to seek dental treatment.1-4 Pain is defined as an unpleasant experience, associated with a

variety of comorbid and aggravating factors such as depression and anxiety affecting many aspects of an individual’s life.5 Acute pain is a warning signal and will normally

cease after treatment or when damaged tissue has healed. Chronic pain, i.e. pain that persists for longer than three months, is not only prolonged acute pain, but incurs changes in the nervous system contributing to peripheral and central sensitization.6

Furthermore, chronic pain is associated with a range of psychosocial symptoms.7 Chronic

pain, especially when present in the orofacial region, is related to substantial societal and personal costs8, 9 and poses a negative impact on quality of life.10

In dentistry, an acute pain condition is commonly caused by toothache whereas chronic orofacial pain is often related to Temporomandibular Disorders (TMD).11, 12 Acute dental

pain conditions can be related to various factors such as decay, cracked teeth, pulp inflammation or postoperative pain after tooth extractions.13

TMD is the umbrella term used to embrace pain in the masticatory muscles and temporomandibular joint and affects about 10% of the adult population.2, 14 Typical

symptoms in this patient group are pain on jaw movement and impaired jaw function.15

Another relatively common cause of chronic orofacial pain is mucosal pain, most often related to burning mouth syndrome (BMS). Primary BMS is characterized by a burning sensation in a clinically healthy oral mucosa where no local or systemic disorders can explain the symptoms. BMS has an increasing prevalence with age, affecting between 1% and 15% of the population.16, 17

Over the last decades, the importance of patient reported outcomes have been stressed and their use increased both in clinical and research settings.18 In line with this, patient

reported outcomes such as grading of pain intensity, functional limitations and

psychosocial factors have been incorporated in the diagnostic systems for TMD.15, 19 Pain

intensity is considered to be one of the most clinically relevant dimensions of pain experience regardless of type of injury or disease.20 Measurement of pain intensity is

however complex since pain is a subjective experience.21

Pain has an impact on many aspects of an individuals’ life, and as mentioned above, especially so when present in the orofacial region. To evaluate the impact of oral conditions and to assess the efficacy of dental interventions, it is one of the most important dental patient-reported outcomes, dPROs.18 The impact from any oral health

condition, including pain, can be described by the dPRO oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL). Thus, pain is one of the four OHRQoL dimensions that have been proposed to capture the impact from any oral health condition on the individual patient.22, 23 In fact,

Orofacial Pain is just one of four basic components that is measured by dental patient-reported outcome measures (dPROMs) that are generic for oral diseases.24

As a complement to disease-specific instruments, the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP) can provide an overall assessment encompassing the different domains of quality of life. OHIP is the most comprehensive and most widely used instrument to measure

OHRQoL. The original form (OHIP-49) consists of 49 items that describe the impairment in seven different domains of quality of life. Better understanding of the concept has suggested a move from these seven domains to the four dimensions Orofacial Pain,

Orofacial Appearance, Oral Function, and Psychosocial Impact. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review was to scientifically support the concept of these new four

domains by specifically describing the painful OHRQoL impact, using patient populations with treatment need related to odontogenic pain, oral mucosal pain/BMS, third molar extraction, and TMD as models for the orofacial pain dimension.

Methods

This systematic review followed a protocol registered in PROSPERO

(CRD42017064033) and was carried out in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement.25

● Human adult population or patients (> 18 years) with treatment need related to different orofacial pain conditions; odontogenic pain, oral mucosal pain/BMS, third molar extraction, and TMD. The pain conditions could be self-reported or clinically diagnosed.

● Reporting OHRQoL with OHIP mean or median domain scores (49, OHIP-20, OHIP-19, and OHIP-14).26-28

● English language

Exclusion criteria:

● Not full text publications (abstracts, editorials, etc.)

● No primary data available or data not in original 0 to 4 OHIP item response format.29

● Duplicate articles

Literature search

As this review was part of a larger project on the four-dimensional model of the OHIP, a pool search was carried out that provided data for all four OHRQoL dimensions

complemented by a manual search for the specific dimensions. The electronic literature search was conducted by a trained librarian (NTM, see Acknowledgements) utilizing natural language in one broad search block, by using the free text search terms “Oral

Health Impact Profile” OR “OHIP” to identify articles that measure OHRQoL by OHIP for

any oral health condition. An electronic search in PubMed (Medline), EMBASE,

Cochrane, CINAHL, and PsycINFO from the inception of respective database to June 8, 2017 and updated January 14, 2019, in combination with hand searches identified 1,413 articles. Grey literature was not included and authors were not contacted for additional information.

Screening and selection procedure

Two reviewers (SS, NTM, see Acknowledgements) independently screened all titles and abstracts for inclusion. The initial assignment of full text articles to the Orofacial Pain dimension was carried out by two reviewers (SS, MTJ see Acknowledgements), and was checked by a third reviewer (IO). The assignment of an article was changed to one of the

other dimensions (Oral Function, Orofacial Appearance or Psychosocial Impact) if

agreed by all reviewers. All potentially eligible articles were then reviewed independently in full text against the inclusion and exclusion criteria by one author of the method

chapter29 (SS) and by one author from this chapter (IO/NS). Uncertainties were resolved

by consultation with another reviewer (MTJ).29

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors (BHH and IO or NS) independently assessed risk of bias for the eligible articles using a modified version of a quality assessment for prevalence studies tool developed by Munn et al.30 Four of the ten items (numbers 2, 8, 9 and 10) in the

appraisal tool were removed as they were not considered relevant for the present review.29 Each of these six questions could be answered with “yes,” representing a low

risk of bias, “unclear” representing unknown risk or “no,” representing a high risk of bias. Any disagreements were resolved by arbitration.

Data extraction

The following data were extracted from the included articles: first author, year of publication, journal name, study population, characteristics of the individual patient samples, age and gender information, OHIP version used, OHIP Physical Pain domain score (mean or median), OHIP orofacial pain domain score distribution values

(confidence intervals, standard errors, standard deviations, interquartile ranges, total range). Data extraction was carried out included articles by one researcher (SS) and checked by a second researcher (IO/NS). For studies that evaluated treatment, the pre-treatment baseline data was used.

Data analysis

The study included mean values derived from four versions of the OHIP questionnaire (14-item, 19-item, 20-item, and 49-item). The data from OHIP-19, OHIP-20 and OHIP-49 were converted to OHIP-14 means together with 95% confidence interval values restricted to fit on a 0 to 8 scale.29 Mean and 95% confidence interval values were

derived either directly from the articles when provided, or converted from other values. When mean values were absent, median values were used instead. When confidence

Accepted Article

interval values were missing, they were calculated from data provided as standard deviation, standard error, interquartile range, or 25% and 75% quartile range. Further details with regard to the methodology can be found in the method article by Sekuliz et al.29

Results

The literature search identified 2,104 articles. After screening of abstracts, 1,607 articles were reviewed in full text and 36 articles met the inclusion criteria for the Orofacial Pain dimension (Fig.1).

In total, these 36 articles included 44 pain patient populations with 59 patient samples. For the included main pain conditions, 7 articles concerned odontogenic pain, 19 articles concerned patients with mucosal pain/BMS, 3 articles pain after extraction of 3rd molars

and 8 articles concerned patients with TMD. One of these articles included both a patient sample with mucosal pain and a patient sample with TMD pain.31 More than half of the

articles (n=20) had utilized OHIP-14, and the remaining 16 articles reported OHIP-49 scores. A majority of articles, 22 articles, included one patient sample and the remaining contained 2 to 5 patient samples.

The risk of bias assessment was carried out with a modified tool for prevalence studies and for the domain “Coverage” a substantial proportion of articles, including a total of 22 patient samples were deemed to have an unclear risk of bias with a further 4 patient samples deemed to have a high risk of coverage bias due to lower response rates (Fig. 2) All the included articles were retained for further analyses.

The 36 primary studies reported OHIP data for 44 patient populations represented by 5,849 patients (Table 1). A typical orofacial pain impact for a majority of populations was between 2 and 3 on a 0 to 8 converted OHIP scale. The orofacial pain impact score for individual patient samples ranged from 0.3 to 6.8. The individual pain condition with the highest reported impact was pain after 3rd molar extractions with an average score of

4.4. The patient populations with the other three pain conditions reported average scores ranging from 2.5 to 3.2. (Fig. 3).

The main finding in this systematic review was that patients with conditions deemed representative for the orofacial pain reported a moderate impact for the pain dimension of OHRQoL. When applying a 4-dimensional measurement approach using Oral

Function, Orofacial Pain, Orofacial Appearance, and Psychosocial Impact to

characterize how patients suffer from oral diseases, standardized information for the orofacial pain dimension was available from 36 publications including 44 patient populations with 59 samples of dental patients where pain was the principal factor determining the patient’s suffering. Standardized information was available for common pain conditions in the stomatognathic systems such as acute pain related to third molar extractions and chronic pain related to odontogenic, mucosal, and TMD pain conditions. The impact from pain conditions on quality of life might be related to different factors, such as whether the pain is acute or chronic, and to different pain characteristics, e.g. intensity, frequency and duration as well as psychosocial factors as proposed in the biopsychosocial model. Pain intensity is considered to be one of the most clinically relevant dimensions of pain experience regardless of type of injury or disease20 and is

one of the domains recommended by IMMPACT.32 A relationship between pain intensity,

pain related disability and QoL has also been reported33 and pain reduction has been

suggested as an important factor for QoL improvement.34 This is corroborated by reports

that improvements in QoL go hand in hand with reduction of pain.35 Conversely, HRQoL

also predicted pain intensity in patients with TMD at an 8-year follow-up,36 underlining

the reciprocal nature of the relationship between pain and quality of life.

In general, the impact from orofacial pain on QoL has been reported to be substantial.9,

10, 37 Therapeutic intervention with NSAIDs and SSRI in patients with TMD have been

reported to result in an increase in OHRQoL.38, 39 Turp et al also reported that a range of

other interventions, with the exception of TMJ surgery, improved QoL in patients with TMD.39 In a later review, a variety of interventions such as psychotherapy, occlusal

appliance therapy and orthognathic surgery in patients with severe malocclusions was reported to improve OHRQoL in patients with TMD.35 In patients with TMD, improved

but also for placebo.38

The present review included patient populations with four different pain conditions in order to map the impact from pain on OHRQoL. These different patient populations represent common and diverse conditions with dental, oral and orofacial pain. The impact from three of the pain conditions, odontogenic pain, oral mucosal pain/BMS and TMD, was similar, whereas the acute pain condition, ‘pain after extraction’, was related to a higher impact on QoL. Although this difference may in part be related to pain intensity, the impact from the psychosocial domain, in accordance with the

biopsychosocial pain model should be emphasized.7

While we identified a considerable number of patient populations where standardized OHRQoL information was available, and we conclude that this coverage allows an informative comparison across conditions, actually more standardized information could be made available for analysis. Several primary studies only provided OHIP summary score information, not allowing us to differentiate the Orofacial Pain dimension from the other three dimensions.40 Other publications provided with OHIP item frequencies even

more detailed OHRQoL information;41 however, without access to the original data, we

could not derive compatible score information for the present review. Furthermore, we were not able to include some articles with published OHIP data because authors used the OHIP domains, but they deviated from the original scoring recommendation and this created no-compatible scores.42 The amount of this non-usable information to map all

oral diseases with a standardized metric is not trivial. For every article we included in our systematic review, we had to exclude one just because OHIP domain values were not informative for our review. This demonstrates, based on findings in published articles, that at least about half of the available OHIP literature does not provide sufficient compatible information for data synthesis. This indicates a substantial problem where researchers measured the impact of diseases and interventions with a dental patient-reported outcomes oriented approach, which is laudable, but nevertheless the produced data and findings cannot be optimally used. Accordingly, to improve this situation, data from this article, together with data from the other articles in this special Issue, can provide a basis for recommending specific OHRQoL instruments to collect and present

Accepted Article

standardized OHRQoL in all settings.

Two specific conclusions can be drawn regarding the application of the OHIP. First, even more standardized Orofacial Pain information is available and could be potentially

utilized in the future to include even more oral diseases on the same map of

standardized patient suffering. Second, this project demonstrates standardization of data collection and analysis is of utmost importance to derive internationally compatible

information. Such information, together with the concept of putting outcomes in relation to cost, i.e. value-based oral health care, can provide the foundation for evidence-based dentistry, thereby providing the best treatments to patients.

The overall conclusion of the current project is, in fact, positive in terms of the ultimate goal toward characterizing all dental patients’ suffering with a single metric to allow comparison over different conditions. Despite a considerable amount of four-dimensional OHRQoL information that could not be utilized in the present review, the number of 44 characterized patient populations is impressive. It should be noted however, that for the oral mucosal pain group there may be an overlap in patient populations between the studies as six studies originate from the same research group. This rich information is complemented by information for 154 dental patient populations suffering from

substantial functional OHRQoL impact,43 63 patient populations suffering from a principal

aesthetical impact,44 and 25 patient populations suffering from broader psychosocial

impact.45 Interestingly, while OHIP is a dPROM for adults, standardized OHRQoL

information, including Orofacial Pain data, is also available for a substantial number of pediatric populations46. While all these dental patient populations have also standardized

Orofacial Pain information, however, based on conceptual and technical reasons,29 we

did not present them in this article.

In conclusion, the present review provides standardized information about the OHRQoL impact from four orofacial pain conditions as a model for the Orofacial Pain dimension. The results indicate moderate impact for the pain dimension of OHRQoL in patients with common orofacial pain conditions. While there is still a long way to go to characterize all oral diseases18 with universal patient impact metric, this available standardized Orofacial

Pain information is substantial and together with Oral Function, Orofacial Appearance, and Psychosocial Impact information the provided data can serve as framework to put current and future studies using the concept OHRQoL into perspective.

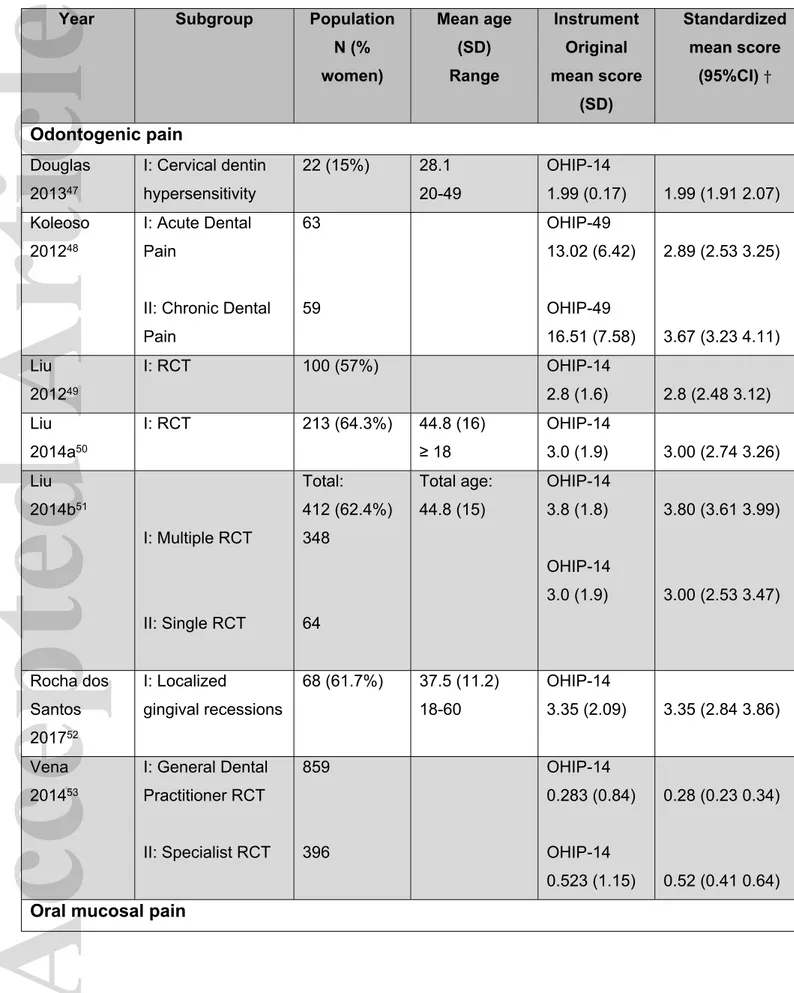

Table 1 OHIP scores for patients in the Orofacial Pain dimension (n=36) Year Subgroup Population

N (% women) Mean age (SD) Range Instrument Original mean score (SD) Standardized mean score (95%CI) † Odontogenic pain Douglas 201347 I: Cervical dentin hypersensitivity 22 (15%) 28.1 20-49 OHIP-14 1.99 (0.17) 1.99 (1.91 2.07) Koleoso 201248 I: Acute Dental Pain

II: Chronic Dental Pain 63 59 OHIP-49 13.02 (6.42) OHIP-49 16.51 (7.58) 2.89 (2.53 3.25) 3.67 (3.23 4.11) Liu 201249 I: RCT 100 (57%) OHIP-14 2.8 (1.6) 2.8 (2.48 3.12) Liu 2014a50 I: RCT 213 (64.3%) 44.8 (16) ≥ 18 OHIP-14 3.0 (1.9) 3.00 (2.74 3.26) Liu 2014b51 I: Multiple RCT II: Single RCT Total: 412 (62.4%) 348 64 Total age: 44.8 (15) OHIP-14 3.8 (1.8) OHIP-14 3.0 (1.9) 3.80 (3.61 3.99) 3.00 (2.53 3.47) Rocha dos Santos 201752 I: Localized gingival recessions 68 (61.7%) 37.5 (11.2) 18-60 OHIP-14 3.35 (2.09) 3.35 (2.84 3.86) Vena 201453 I: General Dental Practitioner RCT II: Specialist RCT 859 396 OHIP-14 0.283 (0.84) OHIP-14 0.523 (1.15) 0.28 (0.23 0.34) 0.52 (0.41 0.64)

Oral mucosal pain

Dvorak 201554

I: Painful OLP men

II: Painful OLP women 19 (0 %) 43 (100%) 59 (15) 24-84 59 (11) 31-82 OHIP-49 8.8 (6.1) OHIP-49 15.3 (8.8) 1.96 (1.31 2.62) 3.40 (2.80 4.00) El Khouli 201455 I: RAS II: RAS 25 (52%) 25 (60%) 33.7 (14.6) 32.5 (13.8) OHIP-14 3.8 (2.61) OHIP-14 3.96 (2.05) 3.80 (2.72 4.88) 3.96 (3.11 4.81) Fadler 201556 I: Bullous-erosive/OLP Total: 149 (88%) 73 (46.6%) Total age: 55 (13) 20-82 OHIP-49 13.1 (8.9) 2.91 (2.45 3.37) Karbach 201457 I: OLP 73 (73%) 60 (14.63) OHIP-14 3.12 (2.8) 3.12 (2.47 3.77) Larsson 200431 I: Sjögren’s syndrome II: OMP 29 (26%) 28 (19%) 61 (12.6) 56.7 (14) OHIP-49 9.8 (7.7) OHIP-49 15.6 (7.3) 2.18 (1.53 2.83) 3.47 (2.84 4.10) Liu 201258 I: Oral mucosal

disease 538 (60.6%) 48.6 (16.7) 14-87 OHIP-14 3.68 (2.43) 3.68 (3.47 3.89) Lopez-Jornet 201159 I: BMS II: BMS 25 25 OHIP-49 15.8 (8.31) OHIP-49 14.16 (7.65) 3.51 (2.75 4.27) 3.14 (2.44 3.85) Lopez-Jornet 2008a60 I: BMS 60 OHIP-49 11.53 (8.92) 2.56 (2.05 3.07) Lopez-Jornet 2008b61 I: Sjögren’s syndrome + fibromyalgia 15 OHIP-49 5.27 (7.3) 1.17 (0.27 2.07)

Accepted Article

II: Sjögren’s syndrome 18 OHIP-49 2.89 (4.36) 0.64 (0.16 1.12) Lopez-Jornet 200962 I: OLP II: BMS

III: Vesicular and bullous disorders IV: RAS 100 60 15 41 OHIP-49 11.15 (7.39) OHIP-49 8.83 (7.83) OHIP-49 11.73 (7.98) OHIP-49 11.53 (8.92) 2.48 (2.15 2.80) 1.96 (1.41 2.51) 2.61 (1.62 3.59) 2.56 (2.05 3.07) Lopez-Jornet 201063 I: OLP 74 OHIP-49 5.58 (6.85) 1.24 (0.89 1.59) Lopez-Jornet 201464 I: OLP 40 OHIP-49 5.68 (5.15) 1.26 (0.90 1.63) Lopez-Pintor 201765 I: Xerostomia 50 (30%) 66.62 (14.0) OHIP-14 4.04 (2.13) 4.04 (3.43 4.65) Ni Riordain 201166 I: Chronic oral mucosal conditions 134 62.7 (18.9) OHIP-14 3.84 (2.2) 3.84 (3.46 4.22) Salazar-Sanchez 201067 I: BMS 31 OHIP-49 15.74 (8.28) 3.50 (2.82 4.17) Sanchez-Siles 201568 I: Peri-implantitis non smooth, non-smooth implants II: Peri-implantitis, smooth implants 229 171 OHIP-14 2.83 (2.86) OHIP-14 1.9 (1.93) 2.83 (2.46 3.20) 1.90 (1.61 2.19)

Stone 201569 I: OLP, with 38 OHIP-49

structured oral hygiene instruction II: OLP, without structured oral hygiene instruction 41 13.68 (0.88) OHIP-49 14.34 (0.85) 3.04 (2.98 3.10) 3.19 (3.13 3.25) Thomson 200670 I: Xerostomia 91 OHIP-14 2.79 (1.89) 2.79 (2.40 3.18) Villaneuva-Vilchis 201671 Metabolic oral lesion 5 OHIP-49 13.8 (8.9) 3.07 (0.61 5.52)

3rd molar extraction pain Ghaeminia 201572 II: CBCT‡ + extraction I: OPG‡+ extraction 156 (69.9%) 164 (63.4%) OHIP-14 4.8 (2.2) OHIP-14 4.6 (2.4) 4.80 (4.45 5.15) 4.60 (4.23 4.97) Kieffer 201273 I: Extraction 97 OHIP-14 3.53 (1.7) 3.53 (3.19 3.87) van Wijk 200974 I: Extraction 50 OHIP-14 4.66 (2.34) 4.66 (3.99 5.33) Temporomandibular disorders (TMD)

Ahn 201175 I: TMD pain 23 (73.9%) 27.4 (10.9) OHIP-49

10.61 (5.07) 2.36 (1.87 2.84) Catunda 201676 I: TMD II: TMD 9 (100%) 10 (100%) 43.1 (15.3) 42.85 (14.55) OHIP-14 6.28 (1.6) OHIP-14 6.85 (0.89) 6.28 (5.05 7.51) 6.85 (6.21 7.49) Ismail 201877 I: TMD 92 42.8 (17.1) OHIP-49 10.1 (7.7) 2.24 (1.89 2.60) Kothari 201778 I: TMD pain 58 (82.6%) 37.2 (14.9) OHIP-49 23.6 (10.2) 5.24 (4.65 5.84) Larsson 200431 I: TMD pain 29 (23%) 42.4 (15) OHIP-49 15.4 (5.8) 3.42 (2.93 3.91)

Accepted Article

de Lima 201579 I: TMD disc-displacement (DD) II: TMD DD + Dysfunction III: TMD muscle + dysfunction IV: TMD joint+ dysfuntion V: TMD joint VI: TMD Females VII: TMD Males IV: TMD muscle 40 61 66 62 39 82 19 35 OHIP-14 2.11 (1.19) OHIP-14 2.28 (1.28) OHIP-14 2.35 (1.29) OHIP-14 2.31 (1.32) OHIP-14 2.05 (1.1) OHIP-14 2.44 (1.11) OHIP-14 1.19 (1.29) OHIP-14 1.94 (1.12) 2.11 (1.73 2.49) 2.28 (1.95 2.61) 2.35 (2.03 2.67) 2.31 (1.97 2.65) 2.05 (1.69 2.41) 2.44 (2.20 2.68) 1.19 (0.57 1.81) 1.94 (1.56 2.32) Su 201480 I: TMJ arthritis 211 OHIP-14 4.61 (1.94) 4.61 (4.35 4.87) Su 201681 I: TMJ osteoarthritis 541 (75.2%) 38.6 (15.5) OHIP-14 3.89 (2.28) 3.89 (3.70 4.08)

†: Mean scores and SD from OHIP-49 were converted into OHIP-14 mean and 95% CI values; SD: Standard deviation; 95% CI: 95% confidence interval

‡: Presurgical assessment

OLP: Oral Lichen Planus: BMS: Burning Mouth Syndrome; RAS: Recurrent aphtous stomatitis; OMP: Oral Mucosal Pain.

Figure legends

Fig. 1. PRISMA flowchart of the included and excluded studies.

*One article included both a patient sample with mucosal pain and a patient sample with TMD pain.

Fig. 2. Risk of bias assessment of included studies (n=36) presented as proportions for the assessed domains (Representativeness, Recruitment, Characterization, Coverage, Standard, and Reliability) with low (green), unclear (yellow) and high (red) risk of bias. Fig. 3. Studies (n=36) reporting orofacial pain impact (0-8 OHIP-scale) for patients with odontogenic (n=7), oral mucosal (n=19), 3rd molar extraction (n=3) and TMD (n=8) pain.

Red line indicates the median OHIP score for each pain condition.

References

1. Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D. Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain 2006;10:287-333. 2. Lövgren A, Häggman-Henrikson B, Visscher CM, Lobbezoo F, Marklund S, Wänman A. Temporomandibular pain and jaw dysfunction at different ages covering the lifespan - A population based study. Eur J Pain 2016;20:532-540.

3. Reid KJ, Harker J, Bala MM, Truyers C, Kellen E, Bekkering GE, et al.

Epidemiology of chronic non-cancer pain in Europe: narrative review of prevalence, pain treatments and pain impact. Curr Med Res Opin 2011;27:449-462.

4. Verhaak PF, Kerssens JJ, Dekker J, Sorbi MJ, Bensing JM. Prevalence of chronic benign pain disorder among adults: a review of the literature. Pain 1998;77:231-239. 5. Williams AC, Craig KD. Updating the definition of pain. Pain 2016;157:2420-2423. 6. Nijs J, Paul van Wilgen C, Van Oosterwijck J, van Ittersum M, Meeus M. How to explain central sensitization to patients with 'unexplained' chronic musculoskeletal pain: practice guidelines. Man Ther 2011;16:413-418.

7. Linton SJ, Shaw WS. Impact of psychological factors in the experience of pain.

Phys Ther 2011;91:700-711.

8. Gatchel RJ, Stowell AW, Wildenstein L, Riggs R, Ellis E, 3rd. Efficacy of an early intervention for patients with acute temporomandibular disorder-related pain: a one-year outcome study. J Am Dent Assoc 2006;137:339-347.

9. Sessle BJ. The Societal, Political, Educational, Scientific, and Clinical Context of Orofacial Pain. . In: Sessle BJ, editor. Orofacial Pain: Recent Advances in Assessment, Management, and Understanding of Mechanisms. Washington, D.C: IASP Press; 2014. p. 1-15.

10. Dahlstrom L, Carlsson GE. Temporomandibular disorders and oral health-related quality of life. A systematic review. Acta Odontol Scand 2010;68:80-85.

11. Lipton JA, Ship JA, Larach-Robinson D. Estimated prevalence and distribution of reported orofacial pain in the United States. J Am Dent Assoc 1993;124:115-121.

12. Zakrzewska JM. Differential diagnosis of facial pain and guidelines for management. Br J Anaesth 2013;111:95-104.

13. Currie CC, Stone SJ, Connolly J, Durham J. Dental pain in the medical emergency department: a cross-sectional study. J Oral Rehabil 2017;44:105-111.

Accepted Article

14. Drangsholt M. Temporomandibular pain. In: Crombie IK, Croft PR, Linton SJ, LeResche L, Von Korff M, editors. Epidemiology of pain. Seattle (WA): IASP Press; 1999. p. 203–233.

15. Dworkin S, LeResche L. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular

disorders: review, criteria, examinations and specifications, critique. J Craniomand Disord 1992;6:301-355.

16. Scala A, Checchi L, Montevecchi M, Marini I, Giamberardino MA. Update on burning mouth syndrome: overview and patient management. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2003;14:275-291.

17. Tammiala-Salonen T, Hiidenkari T, Parvinen T. Burning mouth in a Finnish adult population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1993;21:67-71.

18. John MT. Health Outcomes Reported by Dental Patients. J Evid Based Dent Pract 2018;18:332-335.

19. Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, Truelove E, Look J, Anderson G, Goulet JP, et al. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network* and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Groupdagger. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 2014;28:6-27.

20. Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Haugen DF, Caraceni A, Hanks GW, Loge JH, et al. Studies comparing Numerical Rating Scales, Verbal Rating Scales, and Visual Analogue Scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: a systematic literature review. J Pain

Symptom Manage 2011;41:1073-1093.

21. Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of Chronic Pain. In: ed, editor. Seattle, WA: IASP Press; 1994.

22. John MT, Feuerstahler L, Waller N, Baba K, Larsson P, Celebic A, et al. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Oral Health Impact Profile. J Oral Rehabil 2014;41:644-652.

23. John MT, Reissmann DR, Feuerstahler L, Waller N, Baba K, Larsson P, et al. Exploratory factor analysis of the Oral Health Impact Profile. J Oral Rehabil 2014;41:635-643.

24. Mittal H, John M, Sekulic S, Theis-Mahon N, Rener-Sitar K. Patient-reported outcome measures for adult dental patients: A systematic review. J Evid Based Dent Pr 2018;00:1-18.

25. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535. 26. Allen F, Locker D. A modified short version of the oral health impact profile for assessing health-related quality of life in edentulous adults. Int J Prosthodont

2002;15:446-450.

27. Slade GD. Derivation and validation of a short-form oral health impact profile.

Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1997;25:284-290.

28. Slade GD, Spencer AJ. Development and evaluation of the Oral Health Impact Profile. Community Dent Health 1994;11:3-11.

29. Sekulic S, John MT, Häggman-Henrikson B, Theis-Mahon N. Functional, painful, aesthetical, and psychosocial impact of

oral conditions – a systematic review. J Oral Rehabil 2020 (submitted).

30. Munn Z, Moola S, Riitano D, Lisy K. The development of a critical appraisal tool for use in systematic reviews addressing questions of prevalence. Int J Health Policy Manag 2014;3:123-128.

31. Larsson P, List T, Lundstrom I, Marcusson A, Ohrbach R. Reliability and validity of a Swedish version of the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-S). Acta Odontol Scand

2004;62:147-152.

32. Turk DC, Dworkin RH, Burke LB, Gershon R, Rothman M, Scott J, et al. Developing patient-reported outcome measures for pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain 2006;125:208-215.

33. van der Meulen M, John M, Naeije M, Lobbezoo F. Developing abbreviated OHIP versions for use with TMD patients. J Oral Rehabil 2012;39:18-27.

34. Mauro G, Tagliaferro G, Montini M, Zanolla L. Diffusion model of pain language and quality of life in orofacial pain patients. J Orofac Pain 2001;15:36-46.

35. Song YL, Yap AU. Outcomes of therapeutic TMD interventions on oral health related quality of life: A qualitative systematic review. Quintessence Int 2018;49:487-496.

36. Kapos FP, Look JO, Zhang L, Hodges JS, Schiffman EL. Predictors of Long-Term Temporomandibular Disorder Pain Intensity: An 8-Year Cohort Study. J Oral Facial Pain

Headache 2018;32:113-122.

37. Reissmann DR, John MT, Schierz O, Wassell RW. Functional and psychosocial impact related to specific temporomandibular disorder diagnoses. J Dent 2007;35:643-650.

38. Haggman-Henrikson B, Alstergren P, Davidson T, Hogestatt ED, Ostlund P, Tranaeus S, et al. Pharmacological treatment of oro-facial pain - health technology assessment including a systematic review with network meta-analysis. J Oral Rehabil 2017;44:800-826.

39. Turp JC, Motschall E, Schindler HJ, Heydecke G. In patients with

temporomandibular disorders, do particular interventions influence oral health-related quality of life? A qualitative systematic review of the literature. Clin Oral Implants Res 2007;18 Suppl 3:127-137.

40. Shueb SS, Nixdorf DR, John MT, Alonso BF, Durham J. What is the impact of acute and chronic orofacial pain on quality of life? J Dent 2015;43:1203-1210.

41. Schierz O, John MT, Reissmann DR, Mehrstedt M, Szentpetery A. Comparison of perceived oral health in patients with temporomandibular disorders and dental anxiety using oral health-related quality of life profiles. Qual Life Res 2008;17:857-866.

42. Al-Ahmad H, Abed M, Al-Bitar Z, Al-Abdallah M. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life Changes Following Third Molar Surgery in a Jordanian Population: Effect of Demographic and Clinical Factors on the Immediate Postoperative Period

. J Med J 2014;48:158-170.

43. Schierz O, Baba K, Fueki K. Functional Oral Health-Related Quality of Life Impact: A Systematic Review in Populations with Tooth Loss. J Oral Rehabil 2020;Apr 24.

doi: 10.1111/joor.12984. Online ahead of print.

44. Larsson P, Bondemark L, Häggman-Henrikson B. The Impact of Orofacial

Appearance on Oral Health Related Quality of Life: A Systematic Review. J Oral Rehabil 2020;Mar 20. doi: 10.1111/joor.12965. Online ahead of print.

45. Su N, van Wijk A, CM. V. The Psychosocial Impact on Oral Health Related Quality of L Life: A Systematic Review. J Oral Rehabil (submitted) 2020.

46. Omara M, Stamm T, K. B. Four-dimensional OHRQoL impact in children: A Systematic Review. J Oral Rehabil (Submitted) 2020.

47. Douglas de Oliveira DW, Marques DP, Aguiar-Cantuaria IC, Flecha OD,

Goncalves PF. Effect of surgical defect coverage on cervical dentin hypersensitivity and quality of life. J Periodontol 2013;84:768-775.

48. Koleso O, Akpata O. Oral Health Related Quality of Life in Relation to Acute and Chronic Oral Disease Conditions in Benin, Nigeria. Ife PsychologIA 2012;20:86-93. 49. Liu P, McGrath C, Cheung GS. Quality of life and psychological well-being among endodontic patients: a case-control study. Aust Dent J 2012;57:493-497.

50. Liu P, McGrath C, Cheung GS. Improvement in oral health-related quality of life after endodontic treatment: a prospective longitudinal study. J Endod 2014;40:805-810. 51. Liu P, McGrath C, Cheung G. What are the key endodontic factors associated with oral health-related quality of life? Int Endod J 2014;47:238-245.

52. Rocha Dos Santos M, Sangiorgio JPM, Neves F, Franca-Grohmann IL, Nociti FH, Jr., Silverio Ruiz KG, et al. Xenogenous Collagen Matrix and/or Enamel Matrix Derivative for Treatment of Localized Gingival Recessions: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Part II: Patient-Reported Outcomes. J Periodontol 2017;88:1319-1328.

53. Vena DA, Collie D, Wu H, Gibbs JL, Broder HL, Curro FA, et al. Prevalence of persistent pain 3 to 5 years post primary root canal therapy and its impact on oral health-related quality of life: PEARL Network findings. J Endod 2014;40:1917-1921.

54. Dvorak G, Monshi B, Hof M, Bernhart T, Bruckmann C, Rappersberger K. Gender aspects in oral health-related quality of life of oral lichen planus patients. ISOM

2015;8:33-40.

55. El Khouli AM, El-Gendy EA. Efficacy of omega-3 in treatment of recurrent aphthous stomatitis and improvement of quality of life: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2014;117:191-196. 56. Fadler A, Hartmann T, Bernhart T, Monshi B, Rappersberger K, Hof M, et al. Effect of personality traits on the oral health-related quality of life in patients with oral mucosal disease. Clin Oral Investig 2015;19:1245-1250.

57. Karbach J, Al-Nawas B, Moergel M, Daublander M. Oral health-related quality of life of patients with oral lichen planus, oral leukoplakia, or oral squamous cell carcinoma.

58. Liu LJ, Xiao W, He QB, Jiang WW. Generic and oral quality of life is affected by oral mucosal diseases. BMC Oral Health 2012;12:2.

59. Lopez-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Andujar-Mateos P. A prospective, randomized study on the efficacy of tongue protector in patients with burning mouth syndrome. Oral Dis 2011;17:277-282.

60. Lopez-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Lucero-Berdugo M. Quality of life in patients with burning mouth syndrome. J Oral Pathol Med 2008;37:389-394.

61. Lopez-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F. Quality of life in patients with Sjogren's syndrome and sicca complex. J Oral Rehabil 2008;35:875-881.

62. Lopez-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Berdugo ML. Measuring the impact of oral mucosa disease on quality of life. Eur J Dermatol 2009;19:603-606.

63. Lopez-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F. Quality of life in patients with oral lichen planus. J Eval Clin Pract 2010;16:111-113.

64. Lopez-Jornet P, Martinez-Canovas A, Pons-Fuster A. Salivary biomarkers of oxidative stress and quality of life in patients with oral lichen planus. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2014;14:654-659.

65. Lopez-Pintor RM, Lopez-Pintor L, Casanas E, de Arriba L, Hernandez G. Risk factors associated with xerostomia in haemodialysis patients. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir

Bucal 2017;22:e185-e192.

66. Ni Riordain R, McCreary C. Validity and reliability of a newly developed quality of life questionnaire for patients with chronic oral mucosal diseases. J Oral Pathol Med 2011;40:604-609.

67. Salazar-Sanchez N, Lopez-Jornet P, Camacho-Alonso F, Sanchez-Siles M.

Efficacy of topical Aloe vera in patients with oral lichen planus: a randomized double-blind study. J Oral Pathol Med 2010;39:735-740.

68. Sanchez-Siles M, Munoz-Camara D, Salazar-Sanchez N, Ballester-Ferrandis JF, Camacho-Alonso F. Incidence of peri-implantitis and oral quality of life in patients

rehabilitated with implants with different neck designs: A 10-year retrospective study. J

Craniomaxillofac Surg 2015;43:2168-2174.

69. Stone SJ, Heasman PA, Staines KS, McCracken GI. The impact of structured plaque control for patients with gingival manifestations of oral lichen planus: a

70. Thomson WM, Lawrence HP, Broadbent JM, Poulton R. The impact of xerostomia on oral-health-related quality of life among younger adults. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2006;4:86.

71. Villanueva-Vilchis MD, Lopez-Rios P, Garcia IM, Gaitan-Cepeda LA. Impact of oral mucosa lesions on the quality of life related to oral health. An etiopathogenic study. Med

Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2016;21:e178-184.

72. Ghaeminia H, Gerlach NL, Hoppenreijs TJ, Kicken M, Dings JP, Borstlap WA, et al. Clinical relevance of cone beam computed tomography in mandibular third molar removal: A multicentre, randomised, controlled trial. J Craniomaxillofac Surg

2015;43:2158-2167.

73. Kieffer JM, van Wijk AJ, Ho JP, Lindeboom JA. The internal responsiveness of the Oral Health Impact Profile-14 to detect differences in clinical parameters related to

surgical third molar removal. Qual Life Res 2012;21:1241-1247.

74. van Wijk A, Kieffer JM, Lindeboom JH. Effect of third molar surgery on oral health-related quality of life in the first postoperative week using Dutch version of Oral Health Impact Profile-14. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009;67:1026-1031.

75. Ahn HJ, Lee YS, Jeong SH, Kang SM, Byun YS, Kim BI. Objective and subjective assessment of masticatory function for patients with temporomandibular disorder in Korea. J Oral Rehabil 2011;38:475-481.

76. Catunda IS, Vasconcelos BC, Andrade ES, Costa DF. Clinical effects of an avocado-soybean unsaponifiable extract on arthralgia and osteoarthritis of the temporomandibular joint: preliminary study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2016;45:1015-1022.

77. Ismail F, Lange K, Gillig M, Zinken K, Schwabe L, Stiesch M, et al. WHO-5 well-being index as screening instrument for psychological comorbidity in patients with temporomandibular disorder. Cranio 2018;36:189-194.

78. Kothari SF, Baad-Hansen L, Svensson P. Psychosocial Profiles of

Temporomandibular Disorder Pain Patients: Proposal of a New Approach to Present Complex Data. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 2017;31:199-209.

79. de Lima O, Caetano P, Miranda J, Malta N, Leite I, Leote F. Evaluation of the life quality in patients with Temporomandibular Disorders. Braz Dent Sci 2015;18:77-83.

80. Su N, Yang X, Liu Y, Huang Y, Shi Z. Evaluation of arthrocentesis with hyaluronic acid injection plus oral glucosamine hydrochloride for temporomandibular joint

osteoarthritis in oral-health-related quality of life. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2014;42:846-851.

81. Su N, Liu Y, Yang X, Shen J, Wang H. Correlation between oral health-related quality of life and clinical dysfunction index in patients with temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis. J Oral Sci 2016;58:483-490.

Records identified database search MEDLINE (Pubmed) (n = 1,388) EMBASE (n = 1,450) Cochrane (n = 239) CINAHL (n = 488) PsycINFO (n = 88) Total (n=3,563) Sc reen in g Inc lude d E li gib il it y Ide nti fi ca ti o n

Additional records identified through other sources

(n = 3)

Records after duplicates removed (n = 2,104)

Abstracts screened (n = 2,104)

Abstracts excluded (n = 497)

Full-text articles assessed for eligibility

(n = 1,607)

Full-text articles excluded (n = 1,436)

Lack of domain scores (n = 1,040) Invalid scales, no distribution values, partial domain scores (n = 247) Not target patient population (n = 140) Dual populations (n = 8)

Follow-up data only (n = 1) Studies included in Qualitative synthesis (n = 171) Orofacial pain (n = 36) Oral function (n = 78) Orofacial Appearance (n = 33) Psychosocial impact (n = 24) Oral mucosal (n = 19)* Odontogenic (n = 7) 3rd molar extraction (n = 3) TMD (n = 8)* joor_12994_f1.docx

Accepted Article

This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved