Communication for Development One-year master

15 Credits

Melbourne’s ‘African gang crisis’

A content analysis comparing two Melbourne media outlets

Lisa Smyth

"People should not have to see me on the train and be afraid.

I am more than the colour of my skin."

Table of Contents

Abstract ... 2

1. Introduction ... 3

1.1 Australian multiculturalism... 5

1.2 Sudanese in Australia ... 7

1.3 Mediatization, media framing and Communications for Development (C4D) ... 9

1.4 Limitations ... 11

2. Literature Review ... 12

2.1 Mediatization ... 12

2.2 Media Framing in Australia ... 14

2.3 Methodological approaches ... 15

3. Theory ... 17

3.1 Media Framing Theory ... 17

3.2 Source standardization ... 20

4. Method – Content analysis ... 23

5. Analysis ... 26

5.1 Manifest content – The Age ... 26

5.1.1 Sudanese Community ... 26

5.1.2 Politicians... 28

5.2 Manifest content – Herald Sun ... 28

5.2.1 Police, judges, lawyers ... 28

5.2.2 Victims of violence, witnesses to violence ... 30

5.3 Latent content ... 31

6. Conclusion ... 36

Abstract

In this paper I argue that in a mediatized Australia, where media are

increasingly constructing society and culture as a whole, racializing frames used by Melbourne newspapers The Age and Herald Sun during a two-month period in 2018 contribute to the continued ‘othering’ of the ‘highly visible’ Sudanese-Australian and Sudanese refugee communities, and the erosion of the policy, and lived reality, of multiculturalism in Australia.

Building upon the existing extensive body of research about the representation of refugee groups in Australian media, I use media framing theory to inform my analysis. In order to understand what media frames the Melbourne print media constructed around the ‘African gang crisis’ in 2018 I chose to conduct a quantitative and qualitative content analysis of the types of sources used, and the quotes referenced, within the news articles.

The analysis shows that ‘the media’ cannot be treated as one

homogenous ‘sense-making’ group, as latent patterns of dominating source types as used by each newspaper point to specific ‘newsroom frames’ for each outlet. These ‘newsroom frames’ should be taken into account when exploring the media frames and, specifically, the role of racializing frames, in understanding the ‘othering’ of black Sudanese people in Australia in relation to the country’s ‘white majority’. Only with this understanding can we begin to dismantle the lingering impact of the country’s ‘White Australia Policy’ past and make multiculturalism the solid foundation of Australia’s future.

Keywords: African gang crisis, Sudanese-Australians, Sudanese refugees, media content analysis, media framing theory, multiculturalism

1. Introduction

Australia is a country quite literally founded on an ideal of ‘whiteness’ and racial exclusivity. Soon after its establishment as a nation-state in 1901, the government introduced the White Australia Policy. National identity, national feeling and a collective sense of ‘belonging’ was explicitly built on an

opposition to non-British immigration and ‘othering’ of newly arrived migrants (Henry-Waring, 2008; Udah, 2017). The White Australia policy was not abolished until 1973, and while multiculturalism has taken over as official government policy, the lingering impact of racializing immigrants and refugees is still highly visible in the mediatization of Australian society through the use of racialized frames.

In the late 1990s the Australian government began accepting a group of migrants that was the most ‘visibly different’ from the ‘white’ majority since the end of the White Australia Policy – African, mostly Sudanese1, refugees.

As their numbers have grown, Sudanese migrants and their children have become a highly visible ‘problem group’ for the lingering, and revived,

racializing frames that continue to exist within Australian society as a result of its colonial and assimilationist past (Nolan, Farquharson, Politoff and

Majoribanks, 2011; Nolan, Burgin, Farquharson and Majoribanks, 2016 and Windle, 2008).

Murji & Solomons definition of racialisation is the basis for understanding racializing frames in this paper – “the cultural or political processes or situations where race is involved as an explanation or a means of understanding” (as quoted in Windle, 2008, p.555) and Iyengar’s 1991 definition (quoted in Kwansah-Aidoo and Mapedzahama, 2015, p.3) of media framing is most relevant to this paper:

A media frame therefore is “the central organising idea for news

content that supplies a context and suggests what the issue is through the use of selection, emphasis, exclusion and elaboration”.

1 In the latest Australian census in 2016, people could either identity as being born in South Sudan or

Sudan (Victorian State Government, 2016). While recognising the hundreds of ethnic tribes that exist within both countries, I have chosen to use the term ‘Sudanese’ throughout this paper for ease of understanding.

The structural shift that has taken place within Australian society in recent years as the media have not just reflected, but helped construct, the very foundations of everyday life through the process of mediatization, means the media are an influential and important site for analysis. While not only as a result of the digital revolution, the mediatization of Australian has resulted in racializing frames that reinforce ‘othering’ that have helped determine

accepted discourses around certain groups. As noted by Bullimore (quoted in Kwansah-Aidoo and Mapedzahama, 2015, p.10) “the Australian media, like the media of many Westernised countries, plays a significant role in not only providing information about the society in which we live but also in actively constructing for us a picture of that society”. However, quoting Cottle, Nolan et al. (2011) believe there is hope in that “while media representations may create and reinforce social hierarchies and forms of discrimination, the media can also ‘provide crucial spaces in and through which imposed identities or the interests of others can be resisted, challenged and changed’” (P. 659).

In 2018 a surge of ‘frenzied’ media coverage of the ‘African gang crisis’ in Melbourne occurred, fuelled by statements made by the Home Affairs Minister, Peter Dutton, and the Prime Minister of Australia, Malcolm Turnbull, and based on several violent incidents involving African Australians, including the murder of a young girl at a house party, and an event described as a ‘brawl, ‘fight’ and ‘riot’ amongst 100 Sudanese-Australians in Taylor’s Hill. The racialized framing of these events suggests an instability to Australia’s

multiculturalism, as ‘us’ and ‘them’ dichotomies are still being created and reinforced in today’s media.

Building on a solid foundation of research already conducted about representations of the Sudanese community in Australian media, this paper will examine how the selection of sources and the selection of quotes used by different Melbourne media contributes to the continued ‘othering’ of newly arrived refugees and migrants in Australia and reinforces discourses that destabilise multiculturalism. As Jupp observes (quoted in Van Krieken, 2012, p.510) an “underground of assimilation still runs beneath the multicultural structures, constantly threatening them with erosion”.

1.1 Australian multiculturalism

In 1901 the Australian Government embarked on the task of building a new nationalism from the ground up. As a ‘settler country’, like Canada and the US, which effectively erased its Indigenous Peoples’ culture and history from all discussions or conceptions of national identity, the government chose an obvious colonial path. McGregor (as referenced in Moran, 2011, p.2157) argues that a ‘white’ Britishness was the “only viable myth that could unite Australians” at the time, and even though it had inherent issues for an immigration state, it was necessary for nation building. But, as Hall notes, creating identities “entails the radically disturbing recognition that it is only through the relation to the Other, the relation to what it is not, to precisely what it lacks…” that construction occurs (2011, p. 10). To build a nation, the ‘Other’ must be clearly identified and remain highly visible for an identity to remain strong.

However, even before the abolition of the White Australia Policy, the country experienced waves of non-British immigration – first Chinese migrants arrived in the 1800s, then Italian and Greek migrants after the Second World War, followed by Lebanese and Vietnamese refugees in the 60s and 70s fleeing conflicts at home. All of these ethnic minority groups received racial abuse and were on the receiving end of claims of ‘violent tendencies’ when they first arrived (see Gale, 2004 for media discourse about refuges and asylum seekers; and Teo, 2000 for how newspaper reporting contributes to the marginalisation of Vietnamese migrants). How was a ‘white’ British

national identity supposed to flourish within ‘non-white’ residents and citizens? According to Van Krieken (2012) this dilemma led to three official models of social integration adopted by the Australian government: assimilation (1947-1966), integration (1966-1972), and multiculturalism (1972-now).

Assimilation assumed that Australian society was, and should, remain homogenous and that everyone lived the same way, but the move to

integration allowed room for migrants to maintain a “distinctive cultural identity within Australian national identity” (Van Krieken, 2012, p.504). The official discarding of the White Australia Policy in 1973 made way for a new

understanding of Australian national identity, and in 1978 the Whitlam Government officially declared that:

The Government accepts that it is now essential to give significant further encouragement to develop a multicultural attitude in Australian society. It will foster the retention of the cultural heritage of different ethnic groups and promote intercultural understanding (quoted in Koleth, 2010).

In the 40 years since this declaration, subsequent federal governments have officially reiterated the country’s commitment to multiculturalism, and studies have shown that multiculturalism and diversity are cited when people describe Australia. One qualitative study from 2009, based on findings from 15 diverse focus groups in the state of Victoria, reported that participants saw multiculturalism as a ‘major factor for making Australia a very tolerant society’ and felt that ‘multiculturalism helped transform “Australianess” into a

distinctive Australian identity (Moran, 2011, p.2162).

Though often political discourse outside official documents has suggested a retreat from multiculturalism from both major parties at certain junctions (Moran, 2011). Asian immigration in the 1980s sparked race

debates that culminated in the rise of Pauline Hanson’s anti-multicultural One Nation Party in the early 1990s, and the Cronulla riots of 2005, where a mainly ‘white’ crowd attacking people of ‘Middle-Eastern appearance’, was a shocking wake-up call to many Australians that while the country might be multicultural by definition, multiculturalism was still a work in progress. Following the riots, the Australian Treasurer at the time who was part of the conservative Howard government, Peter Costello, criticized “mushy misguided multiculturalism” for people’s failure to integrate into the broader Australian community, laying the responsibility for the riots with those who were attacked and not the ‘white’ majority (Moran, 2011, p.2164).

According to the most recent 2016 Census nearly half (49%) of all Australians were either born overseas, or one or both parents were born overseas (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2017). Difference is a fact of life in Australia, and yet those newly arrived are still subjected to racializing frames

that mark them as ‘other’. Nowhere is this more visible in the mediatized Australia of today than the media framing of Australia’s Sudanese population.

1.2 Sudanese in Australia

Just over 20 years ago there was a rapid increase in Australia’s intake of African migrants under the Special Humanitarian Program. An influx of ‘black Africans’ has been a highly visible counterpoint, even more so than ethnic groups before them, to a ‘White Australia’ not yet forgotten. The Australian Bureau of Statistics reported that from 30 June 1997 to 30 June 2007 Sudanese people made up 54 per cent of all African arrivals under the program, almost ten times any other African country (Nolan et al., 2016, p.259). According to the 2016 Census, the majority of South Sudan-born migrants settled in the Australian state of Victoria (35.7%), and there was a 146% increase of South Sudan-born migrants settling in Victoria from 2011 to 2016 (The State of Victoria, Department of Premier and Cabinet, 2018).

The numbers of African-born people in Australia remains extremely low in regard to the general population (1.6%) and is also low compared to other ethnic minorities in Australia. However, African migrants have been the focus of a disproportionate amount of media attention, especially in relation to crime, and issues of assimilation and integration, since their arrival (Nolan et al., 2016, p. 260). In Victoria, as the largest proportion of Africans is

Sudanese migrants and refugees, they have become representative of all ‘Africans’ in media reports, and the two terms are often used interchangeably, even within the same article or broadcast.

Sudanese-Australians and Sudanese refugees act as the most visible and recent postcolonial site within Australia society, and still function as the ‘savage Other’ today. As described by McEwan:

The savage Other – to be feared, controlled, disciplined and civilised – was inside and outside of European cultures. In both the sciences and the arts, the profiles of the colonized (especially Africans) came to match those of the Irish, Jews, women, children, criminals, prostitutes, the mentally ill and the working class in Europe (2009, p.126).

Seeing no contradiction with Australia’s own violent past relating to the massacre and oppression of the country’s Aboriginal population, the media have often framed Victoria’s Sudanese population as the violent, ‘tribal’ and ‘war-like’ ‘other’, “principally appearing as ‘problems’ of one sort or another in the genre of news and current affairs” (Morley as quoted in Nunn, 2010, p.185).

This ‘othering’ took on heightened dimensions during two high-profile ‘media events’ that researchers have used to explore media representations of Sudanese in Australia – the 2006 decision of the Tamworth City Council to refuse the resettlement of five Sudanese families (Kwansah-Aidoo and

Mapedzahama, 2015) and the September 2007 murder of a young Sudanese-Australian man, Liep Gony (Nolan et al., 2011; Nolan et al., 2016; Windle, 2008). It was quickly reported that Gony was the victim of ‘African gang’ violence, though the perpetrators were later found to be two white Australian men. But, this did not stop the Immigration Minister at the time, Kevin

Andrews, when commenting on the murder, stating that some groups “don’t seem to be settling and adjusting into the Australian life as quickly as we would hope” and this ‘failure to integrate’ was given as the reason to cut humanitarian visas allocated to Africans from 70% to 30% (Windle, 2008, p.553).

This paper will build on the large body of work about media

representation of migrants in a mediatized Australia, especially the research pertaining to the Sudanese, by focusing on recent events using content analysis and media framing theory. In 2018, politicians commented on, and media repeatedly reported on, an ‘African gang crisis’ in Melbourne – a ‘crisis’ that was not borne out in the official crime statistics. Sudan-born people committed 1.1% of reported criminal offences in Victoria between April 2017 and March 2018, compared to 73.5% of Australian and New Zealand-born people (RMIT ABC, 2018).

In the age of fake news, whether this ‘crisis’ existed in tangible terms – crime statistics, perpetrator and victim accounts etc. – was increasingly

irrelevant to media consumers. By conducting a quantitative and qualitative content analysis of the selection of sources and the selection of quotes and reported speech used by the two leading commercial Melbourne newspapers

– The Age and Herald Sun – during a two-month period in 2018, this paper will explore if the mediatization of Australian society has resulted in racializing media frames which are used to continue the ‘othering’ of

Sudanese-Australians and Sudanese refugees and if this contributes to the undermining of multiculturalism in Australia. Understanding the consequences of

mediatization on society, and how media influence, create and reflect discourse about ‘the Other’, is critical to finding new strategies to combat misinformed reporting about migrants and refugees, and disrupt the negative discourses that are repeated with each new arrival of an ethnic minority. The paper will aim to answer these research questions:

What media frames has the Melbourne print media constructed around the ‘African gang crisis’ in 2018?

a. Which sources are quoted in relation to the crisis? Are some sources quoted more than others?

b. What are the similarities and differences between The Age and the

Herald Sun in their choice of sources?

c. Do the choices of sources of The Age and the Herald Sun point to similar or different media frames when reporting on the ‘crisis’?

1.3 Mediatization, media framing and Communications

for Development (C4D)

Martin Scott’s book, Media and Development (2014) discusses three fields where international development and media intersect: Media for development (as a subset of C4D), Media Development and Humanitarian

Communications. In the final pages, indeed the final paragraph, of his book, Scott chooses to discuss the role of mediatization in development as a crucial area of future study (2014, p.204):

“The idea that development is becoming mediatized marks a clear departure from traditional concerns for the role of media in delivering information, facilitating participation, promoting good governance and democracy, raising money and circulating discourses of global

inequality. This is important because it makes clear the fact that these three fields represent only a starting point for developing a broad, critical appreciation of the role of media in development.”

For the purposes of this paper, I view mediatization as Couldry does, in line with Friedrish Krotz’s thinking as a “structural shift comparable to globalization and individualization: this structural shift is associated with the increasing involvement of media in all spheres of life so that ‘media in the long run increasingly become relevant for the social construction of everyday life, society, and culture as a whole” (2014, p.116).

The first point of contact that Australians have with the distant ‘Other’ is the migrant communities they interact with at home, or, more accurately, that they experience through domestic media. As described above, Australia’s Sudanese population consists almost exclusively of people who arrived under the Special Humanitarian Program. These migrants are accepted as refugees under Refugee Convention criteria or it is determined that they face human rights abuses in their home country and have a connection with Australia. The Government of Australia considers this program as another part of its

obligations regarding humanitarian need around the world, in addition to its international development assistance.

One of the alarming consequences of mediatization, this structural shift to the involvement of media in all spheres of life, is the very tangible

consequences it can have on real world issues. You only have to look back to 2007 and how the inaccurate media reporting of the murder of Liep Gony within racialized frames created a ‘mediatized public crisis’ (Windle, 2008, p.555) and how this is specifically credited with the decision by the

government to cut humanitarian visas allocated to Africans from 70% to 30% in the same year (Nolan et al., 2011; Nolan et al. 2016 and Windle, 2008).

Eleven years later I have chosen to explore racializing media frames in an increasingly mediatized society to understand the ‘othering’ of Sudanese-Australians and Sudanese refugees in Australia. How Sudanese migrants are framed in Australia can have implications for Australia’s global humanitarian commitments and only by attempting to understand and dismantle racialized frames can we hope to create a fair and multicultural Australia.

1.4 Limitations

A significant limitation of my paper is its lack of ‘intercoder reliability’ as I was the only one to conduct the coding. Initially I had planned to code for both sources and themes within the newspaper articles, but I determined that coding for themes required a level of interpretation and subjectivity that wasn’t required in coding for source types, which was relatively objective.

Additionally, I found that coding for source types provided me with enough data to analyse and so I decided to not code the articles for themes. As such, I believe I ensured reliability of my coding as much as I could without using other coders by limiting it to source types.

Also, using NewsBank as a tool to collate and analyse the articles

restricted any consideration of where the article was placed in relation to other news items, its length and size relative to other news items and how any included imagery would impact how the article is perceived relative to its text. A quantitative and qualitative analysis of source selection and quotes used in the context of media framing theory is useful as a finite analysis, but a more thorough examination of all elements of selection, emphasis, exclusion and elaboration used when putting together a news item would provide a more detailed analysis of how racialized frames are constructed. Due to time and resource limitations this was not possible but could be an interesting approach for further study.

Limiting the impact of my personal biases, including my belief that the

Herald Sun is primarily ‘tabloid journalism’ and my privileged position as a

white, middle-class, educated female living in Melbourne was harder to overcome. I aimed to remain aware of my biases throughout the coding and analysis and reviewed my findings for personal bias. I don’t believe I was wholly successful in ensuring my biases don’t bear any weight in the coding or analysis, and if time or circumstance allowed, I would seek out other

2. Literature Review

2.1 Mediatization

Mediatization is a relatively new influential concept that has risen to

prominence in communication and media studies in the past 15 years. While there is no single definition of the term, scholars generally agree that the concept is a continuation, or replacement, of the earlier concept of ‘mediation’ (Couldry and Hepp, 2013; Couldry, 2014: Deacon and Stanyer; 2014).

In the 1970s and 1980s David Altheide and Robert Snow pioneered the term ‘mediation’ to determine “the overall effect of media institutions existing in contemporary societies, the overall difference that media make by being there in our social world’ (Couldry quoted in Scott, 2014, p. 201). Altheide and Snow went beyond earlier scholarly work around media power, which until then had focused on the production-text-audience triangle as the only sites for study and understanding, and instead suggested that the all people had

adopted a ‘media logic’ in every day life (Couldry, 2014, p. 116).

It was also around this time that sociologist Erving Goffman introduced the framing approach to his field of study (Reese, 2001, p. 7), and it was quickly picked up in multiple disciplines, including psychology, psychiatry, sociology, anthropology, epistemology, ethnography, linguistics and

communication (Johnson-Cartee, 2005, p.115). Each discipline has come up with their own interpretation and terminology for the framing concept, such as schema (psychiatrists), prototype (linguists), and script (political behaviourists) but as Tannen summarizes (quoted in Johnson-Cartee, 2005, p.116):

What unifies all these branches of research is the realization that people approach the world not as naïve, blank-slate receptacles who take in stimuli as they exist in some independent and objective way, but rather as experienced and sophisticated veterans of perception who have stored their prior experiences as an ‘organised mass’, and who see events and objects in the world in relation to their prior experience

For the purposes of this paper, I prefer Chong and Druckman’s definition that “framing refers to the process by which people develop a particular conceptualization of an issue or reorient their thinking about an

issue” (2007, p. 104). Communication and media scholars were quick to use the framing method as a tool to help decode the effect of media on society in relation to specific issues, and thus, media framing was born.

Couldry and Hepp (2013) provide a detailed account of how

subsequent scholars took Altheide and Snow’s approach even further, with UK scholar Roger Silverstone, an important part of this momentum,

summarizing ‘mediation’ in these terms: “processes of communication change the social and cultural environments that support them as well as the

relationships that participants, both individual and institutional, have to that environment and each other” (as quoted in Couldry, 2014, p. 115).

As media became more ubiquitous and constant in people’s everyday lives on a global scale, especially with the advent of digital and social media, ‘mediation’ as a concept appeared less fit-for-purpose and two schools of thought emerged from the institutionalist and social constructivist traditions to help describe a new idea: mediatization (Couldry and Hepp, 2013; Couldry, 2014: Deacon and Stanyer; 2014).

Institutionalists see mediatization as a “process in which non-media social actors have to adapt to media’s rules, aims, production logics, and constraints”, while social constructivists see it as a “process in which changing information and communication technologies (ICTs) drive the changing

communicative construction of culture and society” (Deacon and Stanyer, 2014, p.104). While the majority of empirical research has focused on the social constructivist tradition (Deacon and Stanyer, 2014, p.1034), it is the institutionalist definition that appeared at first glance to align more closely with the research focus of this paper.

But, an either/or approach seemed limiting given that while my paper would focus on traditional media (newspapers), how people now access newspaper content is through new and varied ICTs. As such, for the purposes of this paper, I prefer to view mediatization as defined in the introduction above.

2.2 Media Framing in Australia

It is unsurprising given the mediatization of society and the disconnect

between Australia’s official policy of multiculturalism and the racializing frames present in the country’s media that numerous researchers would choose to study the role the media play in representing newly arrived migrants and refugees to Australia in recent years.

Gale (2004) explored the “intersection between populist politics and media discourse through analysis of media representations of refugees and asylum seekers” (p.321) and referred to the ‘politics of fear’, colonial and post-colonial discourses and the emergence of a ‘new racism’ embedded in

nationalism to frame his arguments. Teo (2000), similarly, studied news reports from two Sydney newspapers to reveal evidence of ‘othering’ of the Vietnamese-Australian community by Australia’s ‘white’ majority in relation to Vietnamese gang violence in 1995.

The use of race and ‘othering’ to explore the marginalisation of refugees and minority communities in Australia are clearly key frameworks with which to examine news articles. Importantly, Gale (2004) and Teo’s (2000) research confirmed that racializing frames had been used by media when representing other refugee groups in Australia, and that these frames extended back further than the arrival of the highly visible black African migrants and refugees in the early 90s. It raises the question of whether new racializing frames are being constructed for each new migrant group, or old ones are simply imposed on new groups.

In all three of the studies within my review that specifically analyse media representations of Sudanese Australians (Nolan et al., 2011; Nolan et al. 2016 and Windle, 2008) each references the discourse or politics of ‘integration’ or ‘integrationism’ as a foundational problem in an Australian society founded on the principles of multiculturalism. This was a useful jumping off point for my own research into the history of multiculturalism and helped me place racializing framing by the media in their current political context. However, in my analysis of news articles, the terms ‘integration’ or ‘integrate’ were not used (there were some vague references to ‘fitting in’ in a

handful of articles) and this could point to this discourse being specific to other types of media, such as opinion pieces and letters to the editor.

In reviewing other studies, including Windle’s 2008 analysis of new applications of racializing frames, Nolan et al. (2016) are keen to counter a reductive view of the media that has emerged in framing theory, that media institutions and journalists are “mere extensions of the state” (p. 260). While politicians and police may influence media agendas, Nolan et al. insist that media have their own priorities and drivers, including “’news values’,

frameworks of professionalism and journalists’ occupational concern to perform a ‘public representative’ role, as well as media institutions’ continual interest in generating public engagement and revenue” (2016, pp. 260-261). This significant observation was integral to determining my own approach when applying media framing theory described below, and the weight I provide to examining newsroom frames in Melbourne media.

2.3 Methodological approaches

In today’s digitally-focused world of increasingly niche and segmented media, it is fair to question the legitimacy of analysing articles from newspaper

mastheads - is the printed media still influential in framing, creating and reflecting issues of social importance?

The articles analysed in this paper are drawn from Melbourne’s two most-read daily papers, The Age and the Herald Sun. In June 2018 both had 7-day cross platform (print and online) audiences of 3,085,000 (Roy Morgan, 2018), a little less than half of Victoria’s total population of 6.4 million people. By ensuring news and content is available across both print and digital

platforms, two of Australia’s biggest print mastheads have continued to hold a place of critical importance in Victoria’s social fabric, and still help shape the frames of the important social issues of the day.

Using content analysis, or critical discourse analysis, Nolan et al. (2011), Nolan et al. (2016), Nunn (2010) and Windle (2008) all chose to explore the representation of Sudanese-Australians in the articles of The Age and the Herald Sun, as well as the national masthead The Australian (7-day cross platform audiences of 2,564,000), while Kwansah-Aidoo and

Mapedzahama (2015) plugged in their keywords to Google and a newspaper database to find their articles for analysis. Given the extended coverage and reach of the two Melbourne dailies it makes sense that they would be a preferred site of analysis above other media, such as TV and radio. I did not come upon any research that attempted to analyse radio, TV, or social media in terms of media representations of Sudanese in Australian media, and while my search was not exhaustive, this could be an area for future research consideration.

As will be discussed in the theory section later in this paper, media framing theory has numerous dimensions and examining the framing choices made by journalists requires some deconstruction of journalism culture. For instance, the way ‘news articles’ are constructed and framed compared to opinion pieces or ‘lifestyle content’ is vastly different, with traditional

journalism ideals of objectivity and impartiality not given the same weight or consideration outside ‘hard news’. Kwansah-Aidoo and Mapedzahama (2015), Nolan et al. (2011) and Windle (2008) chose to analyse news and opinion articles as part of the same sample, and Nolan et al. (2016) decided to analyse letters to the editor, which, while written by members of the public, are still a framing device used by the media on a particular issue as the choice of which to publish or not rests with the journalist or editor in charge of that section.

In designing my analysis with the intention of building upon the existing literature, I chose to limit the sample to just news articles given that readers and consumers of media, even in the age of ‘fake news’ and biased media, still expect some impartiality, factual ‘truth’ and ‘balanced reporting’ about events when represented in news articles. I believed this narrower scope would provide a more nuanced representation of the media frames used by journalists when reporting on the Sudanese community in Victoria. However, opinion pieces penned by journalists are a rich source for further research, but, in my opinion, different parameters for analysis would need to be used to understand their role in racializing frames.

Furthermore, while previous studies analysed the text of articles – headlines, lead paragraphs and body text – to establish how media outlets used themes and ‘over-lexicalisation’ to establish media frames, only Nolan et

al. (2016) questioned the selection of ‘voices’ by media, but as this was in regards to letters to the editor, the choice of ‘voices’ used in this type of ‘news’ would have been informed by different journalism practices than the choice of sources in a news article. As Johnson-Cartee states “the news source used by a news reporter determines to a large degree what the news consumer is exposed to and thus considers, which has a significant impact on that news consumer’s political reality” (2005, p. 158).

Finally, while Nolan et al. (2011) were the only one of the four studies that chose to report their findings per newspaper, rather than across ‘the media’ as a whole, the focus was not on comparing the newspapers in depth. This is evident in the ‘discussion and conclusions’ section, where conclusions are broadly presented across all three newspapers, except in briefly noting that The Age appears to represent a ‘soft integrationism’ compared to the ‘hard integrationism’ evident in the two rival newspapers. My analysis has a specific ‘compare and contrast’ focus in order to better understand the causes of racialized frames and their impact on multiculturalism.

3. Theory

3.1 Media Framing Theory

Brüggemann states that “doing journalism is a process of public

sense-making. Journalism is about interpreting the world” (2014, p.61) and Hanitsch states that “journalism culture becomes manifest in the way journalists think and act; it can be defined as a particular set of ideas and practices by which journalists, consciously or unconsciously, legitimate their role in society and render their work meaningful for themselves and others” (2007, p.369). Given the rapidly changing nature of journalism today, and the attacks on media across the globe, including within Australia, about the media’s very credibility and value as ‘sense-makers’, mediatization interlocked with media framing theory has advantages over other theoretical frameworks when analysing news articles. As Brüggemann states “the framing approach opens up a fruitful perspective on journalistic practices…professional criteria of

newsworthiness as well as value judgements will play a role when journalists produce texts with certain news frames” (2014, p. 62).

Media framing theory goes to the heart of the ‘social contract’ between journalists and the public – journalists create meaning and understanding around issues that the public should be aware of, and, simultaneously, reflects what is important to the public in their reporting. Considering journalism as ‘performative’, in that it “constitutes the communities it

addresses at the moment that it claims to represent them” (Chouliaraki, 2012, p.268) and understanding that media framing is a materialization of

performative practice, underpins how mediatization is at the core of social and cultural construction, especially in relation to national identity.

The basis of media framing theory is that the media focuses attention on certain events and then places them within a field of meaning, elevating events to a level of importance that would otherwise not be attained. While Australian journalists may not be aware of ‘othering’ practices they employ based on the country’s colonial and ‘White Australia’ past, how journalists choose, consciously or unconsciously, to “call attention to some aspects of reality while obscuring other elements, which might lead audiences to have different reactions,” (Entman quoted in Kwansah-Aidoo and Mapedzahama, 2015, p.3) can have long-lasting, sometimes devastating, impacts on entire communities.

For the purposes of this paper, there were a number of definitions of framing to draw upon. Brüggemann (2014), Johnson-Cartee (2005, p.117) and Kwansah-Aidoo and Mapedzahama (2015, p.3) all refer to Entman’s 1993 definition:

Framing essentially involves selection and salience. To frame is to

select some aspects of a perceived reality and make them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the term described (emphasis in

original).

This definition sits well when examining the role of Sudanese-Australians and refugees as a ‘problem group’ within society, especially when using content analysis, and lays out a clear four-step path for evaluating the frames of a

news article: 1. What is the problem being reported? 2. Who or what caused it? 3. What normative morals or ethics has the problem violated? 4. Who is responsible for solving or perpetuating the problem? It has been applied to high number of studies (Brüggemann, 2014, p.64).

Entman’s definition is useful when examining the text of news articles for frames and would prove especially useful in analysis of opinion pieces and letters to the editor as these four components are likely to appear in the text of each. However, given that my analysis is an evaluation of source selection, and quote selection, I believe Iyengar’s 1991 definition (quoted in Kwansah-Aidoo and Mapedzahama, 2015, p.3) has more relevance to this paper:

A media frame therefore is “the central organising idea for news

content that supplies a context and suggests what the issue is through the use of selection, emphasis, exclusion and elaboration”.

Frames are essential to journalists – the daily, and even hourly, deadlines and pressures of a modern newsroom require journalists to call upon pre-existing patterns of meaning. Accessing an existing interpretation of a certain event or issue allows for news to be produced at speed, for

journalists to not have to expend too much cognitive energy and removes excessive oversight from senior reporters or editors that would slow down the news making process.

However, Deuze discovered that there is a shared “occupational ideology among newsworkers”, affirming that journalists should: 1. provide a public service, 2. are impartial, neutral, objective, fair and credible, 3. ought to be autonomous, free and independent in their work, 4. have a sense of

immediacy, actuality, and speed, and 5. have a sense of ethics, validity and legitimacy (Hanitzsch, 2007, pp.367-368). How different journalists,

newsrooms and media outlets determine the hierarchy of these elements – for instance whether speed is more important than credibility – can bear out in the media frames they choose to use.

According to Iyengar (Johnson-Cartee, 2005, p.118) media are far more likely to present news from an episodic perspective rather than a thematic perspective. Gitlin (as quoted in Johnson-Cartee, 2005, p.118) describes this evaluation of newsworthiness by journalists according to

traditional assumptions being that “news concerns the event, not the

underlying condition; the person, not the group; conflict, not consensus; the fact that ‘advances the story,’ not the one that explains it” (emphasis in

original). An episodic perspective again allows for expediency, and adheres to common understandings of newsworthiness, but it has significant drawbacks when exploring complex issues, and leads to an overly simplistic

interpretations of media events, including representations of ‘African gangs’. In addition to using media frames to ensure speed and

newsworthiness, “frames are rooted in culture, which manifests itself at the individual, organizational and social level” (Brüggemann, 2014, p.67). In addition to “the influence of governmental and policy settings

[which]…discursively structure engagement with issues relating to ethnic minorities” (Nolan et al., 2011, p.660) at the social level, Brüggemann (2014) argues that there is a difference between news frames, newsroom frames and journalist frames, and that while the first has been the object of numerous studies, the latter two have not been sufficiently explored. Effectively, he believes that news content as a ‘site of meaning’ has been explored

extensively, but the role of journalistic thinking and newsroom norms as ‘sites of meaning’ has not been used to identify media frames in any significant way.

In my analysis I am limited in not being able to explore journalistic frames as it would require extensive interviewing of journalisms themselves about their cognitive approaches to producing the articles under evaluation. However, at the institutional level, I plan on exploring the role of newsroom frames by comparing and contrasting the selection, emphasis, exclusion and elaboration of sources and quotes used between each outlet. Any patterns that emerge differentiating the media frames of Fairfax Media’s The Age, and News Limited’s Herald Sun could point to newsroom frames that support a dominant editorial policy for each outlet about the ‘African gang crisis’ and representations of Sudanese-Australians and refugees.

3.2 Source standardization

In 2001, Tankard developed a list of mechanisms or focal points for identifying frames, including headlines and ‘kickers’, subheads, photographs, photo

captions, leads, selection of sources or affiliations, selection of quotes, pull quotes, logos, statistics and concluding paragraphs (Johnson-Cartee, 2005, p. 124).

Within the broad context of media framing theory, I have chosen to conduct my analysis by examining the selection of sources (quantitative) and the selection of quotes (qualitative) used in The Age and Herald Sun news articles to determine the media frames constructed by each newspaper around the ‘African gang crisis’ in 2018.

As D’Angelo and Kuypers note “journalists cannot not frame topics because they need sources’ frames to make news…” (Brüggemann, 2014, p.62), and Brüggemann explains that journalism “is the result of a process of collective sense-making within the newsroom and a negotiation of meaning between journalists and sources” (2014, p.65).

“Source standardization refers to the practice of journalists using the same group of informants or interviewees over and over again”, and this “common dependency on a select group of informants” (Johnson-Cartee, 2005, p. 153) has a “powerful structuring effect on media frames” (Windle, 20018, p.555). For instance, elites and official sources are easy to access and considered more reliable and trustworthy than other sources and are often selected as representative of ‘balanced reporting’ when authorities for differing sides of an issue are quoted. But, like all framing mechanisms, the selection and emphasis on certain sources to the exclusion of others, creates a media frame that only represents one version of ‘truth’ of an event, and can actively produce ‘othering’ of certain groups within media reporting.

Furthermore, journalists who work on specific ‘beats’ – court reporting, political, environment, business etc. – can also over rely on the use of specific sources and selection of certain types of quotes given their deeper knowledge of a particular ‘beat’ and what constitutes ‘newsworthiness’ in that area

(Bruggemann, 2014, p.72). This can lead to ‘beat bias’ and will be considered within the analysis.

Finally, Johnson-Cartee refers to the fact that condensational symbols are a shorthand that telegraph beliefs, feelings, values and world views to others sharing a similar culture (Johnson-Cartee, 20015, p.120). I argue that sources can be condensational symbols, and that even before examining the

quoted or reported text in detail, readers can be triggered to interpret a similar view of the story simply based on the sources selected.

4. Method – Content analysis

Mao and Richter (2014, p. 2) note that the “effectiveness of media content analysis is proven by the extent to which it helps uncover trends in media messages, changes in journalists’ and other opinion formers’ positions, and changes in community members’ attitudes toward marginalized populations”.

While I briefly considered using critical discourse analysis, after

discussions with my supervisor, I realised that content analysis would provide enough material to draw from in order to compare and contrast the media framing theories of The Age and the Herald Sun.

Given the strengths outlined by Mao and Richter (2014) I conducted a quantitative and qualitative media content analysis of the Herald Sun and The

Age print news articles released between 1 July 2018 and 1 September 2018

that included the keywords and terms, Africa gang, African gang, Africa gang

crisis, African gang crisis, Sudan, Sudanese and Sudanese Australians.

These dates are chosen as the weeks surrounding a 9 August ‘African gang riot’ – a key ‘lightening rod’ event for this issue in 2018. The articles were accessed using the NewsBank database available through Malmo University Library.

Since my proposal I have extended the time frame from one month to two months based on an initial search of the database and a determination that there would be too few articles for a substantive analysis in a one-month period. The analysis is limited to language of headings and body text and does not incorporate images.

Originally, I included Africa as a keyword, but it was included in too many articles that did not reference the events in Melbourne and were instead focused on world events. Once Africa was removed as a keyword, 76 articles were left featuring one or more of the keywords from The Age, and 87 articles from the Herald Sun - six Herald Sun articles were direct duplicates, and four related to a terrorism incident in the UK and were removed, leaving 77 articles in total.

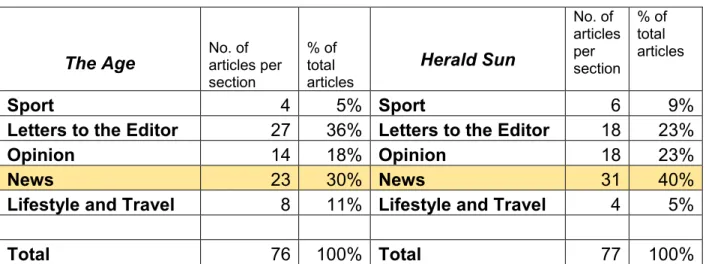

While the number of articles featuring one or more of the keywords was almost identical between the two samples, the types of articles differed. I further categorised the articles based on the ‘section’ they were designated

into as displayed in NewsBank (see Table 1.). I chose not to code articles as ‘news’ based on my own judgement but adhered to the section heading of each displayed in the database. As discussed in section 2.2 of the ‘literature review’ section of this paper, I chose to only focus on the news articles from each newspaper to clearly separate ‘opinion’ from news frames that would be, in theory, according to journalists’ occupational ideology, attempting ‘balanced reporting’. This resulted in 23 articles, or 30% of the total sample, to analyse from The Age, and 31 articles, or 40% of the total sample, from the Herald

Sun. While a full analysis would be needed, an evaluation of the percentage

of articles in each news section relating to the ‘African gang crisis’, and what that reveals about a media outlet’s overall framing of Sudanese-Australians and refugees across its entire coverage, could be an interesting jumping off point for further research.

Table 1. Percentage of type of news articles in each newspaper

The Age No. of articles per section

% of total

articles Herald Sun

No. of articles per section % of total articles Sport 4 5% Sport 6 9%

Letters to the Editor 27 36% Letters to the Editor 18 23%

Opinion 14 18% Opinion 18 23%

News 23 30% News 31 40%

Lifestyle and Travel 8 11% Lifestyle and Travel 4 5%

Total 76 100% Total 77 100%

Validity and reliability are key to robust content analysis (Julien, 2008, p.3; Potter and Levine-Donnerstein, 1999). Potter and Levine-Donnerstein (1999) suggest that before embarking on designing a coding scheme for content analysis you should first assess if 1. a theory is going to guide the design or your coding, or will a theory emerge due to inductive reasoning as coding occurs?; and 2. What type of content is being coded?.

Before beginning this paper, I considered using post-colonialism, mediatization and media framing theory to inform my analysis, but I chose to limit my theoretical framework to just mediatization and media framing theory

due to time, ease of coding, and also as both interlocking theories had enough robustness to fully explore the ideas of racialized frames and

multiculturalism without layering over another theory. This deductive approach is common in content analysis.

Regarding the type of content being coded, Potter and

Levine-Donnerstein suggest there are three types: manifest, latent pattern and latent projective and that the difference among them “is not a clean trichotomy, it is more a difference of degree” (1999, p.262). Manifest content is easily

observable, such as the appearance of a particular word in a written text, whereas latent pattern content finds meaning in recognizing patterns across elements, and latent projective content finds meaning in the way the coder constructs judgements from the content cues and the coder relies on pre-existing mental schema to make these judgements (Potter and Levine-Donnerstein, 1999, pp.259-261).

Understanding the different types of content that can be coded is critical for two reasons – creating coherent and effective coding sheets for coders to ensure ‘intercoder reliability’ (David, J.L., Thomas, S.L., Randle, M., Bowe, S.J., and Daube, M., 2017, p.5; Mao, Y., and Richter, S., 2014, p.8; Stokes, 2003, p.58) and also to understand, and be aware of, personal biases that could come to the forefront of coding latent projective content.

I began coding the identified news articles using computer software NVivo 12 based on an understanding of the content outlined in Figure 1, by which I will judge latent content by evaluating the collective presentation of manifest content in the news article (Gillespie, L.K., and Richards, T.N., 2018, p.6). I determined that a source was being used if direct quotes were

presented, or speech was reported or referred to. The results of my coding are presented in the next section.

Figure 1. Coding of sources by type of content Manifest

content Latent pattern content Latent projective content

Identification of

sources used Comparison of no. of sources used by

Interpretation of dominant sources

5. Analysis

Tables 2 and 3 show the range of sources used in the news articles in The

Age and the Herald Sun that were collated using the keywords outlined in the

previous section.

Table 2. Type and number of sources used in The Age

Ranking of type of sources used

The Age - Sources No. of articles

where the type of source was used % of total articles that include type of source 1 African/Sudanese community 14 61% 2 Politicians 12 52%

3 Police, judges, lawyers 9 39%

4 Victims of violence, witnesses to

violence 4 17%

5 Human Rights Activists 3 13%

Note:More than one source was used in most articles, so no. of articles does not equal total number of news articles (23) and percentages do not total 100.

Table 3. Type and number of sources used in the Herald Sun

Ranking of type of sources used

Herald Sun - Sources No. of articles

where the type of source was used

% of total articles that include type of source

1 Police, judges, lawyers 14 45%

2 Victims of violence, witnesses to

violence 13 42%

3 African/Sudanese community 7 22%

4 Politicians 2 6%

5 Human Rights Activists 1 3%

Note:More than one source was used in most articles, so no. of articles does not equal total number of news articles (31) and percentages do not total 100.

5.1 Manifest content – The Age

5.1.1 Sudanese CommunityThe number one source used by The Age in its reporting of Melbourne’s ‘African gang crisis’ was people identified as belonging to the Sudanese, or

South Sudanese, community in Melbourne. Sudanese community sources appeared in 14 of the 23 articles, or 61% of the articles analysed from The

Age. Many of the sources were reported to have official functions or titles,

such as ‘Community leader and lawyer’, ‘Chairman of the South Sudanese Community Association of Victoria’, ‘Federation of South Sudanese

Associations in Victoria founder and chairman’, ‘founder of outreach group Youth Activating Youth’, and ‘youth affairs officer for South Sudanese Community Association’, and many of the same sources were used to comment across a number of different articles.

In six articles the term ‘community leaders’ or ‘Victoria’s African leaders’ was used to invoke a general, faceless group of people who spoke on behalf of the entire community, and on four occasions ‘Sudanese youth’ were used as a source, though none were reported to belong to a gang, or have committed any violent offences.

The use of Sudanese community members as the number one source when reporting on ‘African gang violence’ and violence committed by, and against, Sudanese-Australian and Sudanese refugees, suggests that The Age is concerned with not silencing Sudanese voices, and is committed to some form of ‘balanced reporting’. However, these sources are almost exclusively called upon to defend or denounce crime or violence, or rebuke ‘racist fearmongering’. In the only article of the 23 that attempts to report on

something non-violent – Sudanese-Australian youth breaking running world records internationally – the first quote from runner Joe Deng is in reference to violence and defending his community:

"Not every Sudanese is a gang member, there are Sudanese playing in the AFL, basketball, we are doing track, it's not right for people to say that," Deng said (Gleeson, 2018).

While source standardization explains the use of mostly ‘official’ sources from the Sudanese community, the fact that the sources must speak for the entire community in defence of the criminal or violent actions of only a small number of individuals, creates an ‘othering’ effect in opposition to Australia’s ‘white majority.

5.1.2 Politicians

The second ranking source type used by The Age in its reporting of

Melbourne’s ‘African gang crisis’ was politicians. Politicians were quoted in 12 of the 23 articles, or 52% of the articles, analysed from The Age.

The Australian Prime Minister, Malcolm Turnbull, and the federal Home Affairs Minister, Peter Dutton, are used as sources in six, and nine, articles respectively in the 12 articles where politicians are quoted in The Age. In both cases, comments made from each in one radio interview (separately) are re-quoted in numerous articles. In four articles their comments were referenced against accusations of ‘inciting racism’ and ‘racist dog-whistling’.

According to Shoemaker and Reese “those with economic or political power are more likely to influence news reports than those who lack power” (Johnson-Cartee, 2005, p. 153). By repeating the same quotes from two of the most powerful people in the country, even alongside claims that the comments are racist, the emphasis placed on the statements from such sources lends credibility to the statements as ‘truth’ or ‘fact’. Two of Turnbull’s statements, made in the same interview, speak to the disconnect between Australia’s assertion of successful multiculturalism, and the racialization of the ‘problem group’ – Sudanese-Australians.

"We have zero tolerance for racism, number one, and number two, this is Australia, the most successful multicultural society in the world," (quoted in Fox Koob, S., and Colangelo, A., 2018).

"There is real concern about Sudanese gangs. You'd have to be walking around with your hands over your ears in Melbourne not to hear that." (quoted in Fox Koob, S., and Colangelo, A., 2018).

5.2 Manifest content – Herald Sun

5.2.1 Police, judges, lawyersThe number one source used by the Herald Sun in its reporting of

Melbourne’s ‘African gang crisis’ was people from the law and justice sector – police, judges and lawyers. These sources appeared in 14 of the 31 articles, or 45% of the articles analysed from the Herald Sun.

Windle (2008) believes that journalists emphasise police perspectives because “newspapers develop a commitment to racializing narratives of urban decay and violence presented by police, and then prioritise stories which appear to fit in to this narrative” (2008, p.556). The fact that sources from the law and justice sector are emphasised the most by the Herald Sun already provides a ‘criminal frame’ to reporting of Sudanese people within Victoria. Within this group, police are far and away the group quoted from the most – in nine of the 14 articles, and often multiple times in the one article. When

directly quoted, police are provided with their full title, ‘Detective Senior Constable’ or ‘Detective Inspector’, but more often police are referred to as a homogenous group – ‘police said’, ‘police allege’, ‘police warned’ and ‘police believe’. When the term ‘community leaders’ is used as a blanket source for the Sudanese community it has an ‘othering’ and distancing effect from the ‘white majority’ who don’t require a faceless group of leaders to defend their actions. But, as Tuchman notes, “facts produced by centralized bureaucratic sources are assumed to be essentially correct and disinterested” (as quoted in Johnson-Cartee, 2005, p.153), and, so, when ALL police warn or believe, as the generalised use of the term ‘police’ implies, then what is stated must be ‘truth’.

Windle states that “as police are given the first and greatest authority to name and define the crimes they are called to, it is unsurprising that it is their labels and descriptions which are taken up and remain affixed through subsequent reporting” (2008, p.556). Police are quoted in four articles as ‘seeking’, observing’ or ‘warning about’ people of ‘African appearance’, which extends the racialized frame of criminality to all Africans. While the use of the term ‘African’ by police may be an attempt to not racially profile the Sudanese community, it is unclear if the determination to use ‘African appearance’ was made by the police or the Herald Sun (as a counterpoint, police quoted in The

Age exclusively used the term ‘African-Australian’). In one article by Hamblin

(2018) the racial descriptor of ‘African’ is invoked to refer to a second, different crime than the one being reported upon, but one sentence later Hamblin confirms the crimes were not related at all:

The friends’ ordeal came just hours after police issued a warning about a group of African youths who used a Taser during a daylight street robbery in Hampton Park, in Melbourne’s southeast.

Detectives later reviewed the evidence and said they no longer believed a Taser had been used.

Robbers from each attack — believed to be separate groups — remained on the run last night.

The reference to the African appearance of the those committing the second crime, even though it is confirmed within the article that the crimes are

unrelated, appears to only serve the function of providing a racialized frame to both crimes. Earlier in the article, when the use of the taser on the victim is described by a witness in graphic detail, “he just started bleeding from the head”, and as “something like a nightmare”, the racial profile of the

perpetrators is not referenced, leaving readers to connect the authoritative police quoting a warning about ‘African youths’ with both crimes.

5.2.2 Victims of violence, witnesses to violence

The second ranking source type used by the Herald Sun in its reporting of Melbourne’s ‘African gang crisis’ was victims of violence or witnesses to violence. This group were quoted in 13 of the 31 articles, or 42% of the articles, analysed from the Herald Sun.

There is only one article difference between articles that used law and order sources, and those that used victims of, and witnesses of, violence as sources, which could suggest that journalists at the Herald Sun consider these two types of sources as equally relevant and credible when framing news articles.

Sometimes quoted in the plural – ‘witnesses’ or ‘victims’ – most often these sources are provided with first and/or last names, and humanising qualifiers such as ‘Local mum’, ‘Dad’, ’73-year-old man’, ‘Taylors Hill resident’ and ‘Bronte Way resident’. None are referred to by racial or ethnic descriptors, and by describing these sources as members of families and communities, readers are encouraged to identify with them as ‘just like me’. While there is no way of knowing the ethnicity or race of these sources, the very lack of such a marker distinguishes them as part of Australia’s ‘white majority’, in spirit, if

not reality. The perpetrators of the violence are provided with only one highly visible defining characteristic – their race, either referenced as ‘African’ or ‘Sudanese’ which clearly sets them apart as ‘other’. Udah (2018, p.398) states that black Africans in Australia “are marginalised within the normative

conceptions of Australian national identity as white” (2018, p.398), and even though the victim and witness sources used by the Herald Sun are not

identified explicitly as white, it is enough that the ‘criminals’ are referenced in terms of their race to create a racialized frame.

5.3 Latent content

Having conducted a content analysis of the types of sources used by The Age and the Herald Sun in representing Sudanese-Australians between 1 July 2018 and 1 September 2018, it is clear that there are some stark differences in source selection, emphasis, exclusion and elaboration.

Before embarking on an analysis of the latent content it is appropriate to address the issue of beat frames or beat bias in the news articles of both newspapers. The 21 articles under analysis from The Age were authored or co-authored by 21 different journalists, and the 31 Herald Sun articles were authored or co-authored by 23 different journalists. This is fairly convincing evidence that no single, or group of three to four journalists, are covering the crime beat for either paper, and, therefore imposing ‘beat frames’ on the news articles under analysis. This makes way for ‘newsroom frames’ to be

considered as a site of examination for the formation of ‘othering’ practices and the creation of racializing frames.

For readers of The Age, the high use of sources from the Sudanese community acts as a ‘condensational symbol’ that triggers beliefs of

‘balanced’, ‘fair, and ‘objective’ reporting. The fact that the Sudanese sources are mostly drawn from power positions adds further legitimacy to their

selection and emphasis when they are quoted alongside politicians, police and judges. According to Johnson-Cartee, “elites occupy power positions within organizations and are more likely to meet the “standard definitions of reliability, trustworthiness, authoritativeness and articulateness” (2005, p.153) that traditional models of journalism expect of news reporting. The top three

source types used by The Age are overwhelming drawn from official sources (elites) and the very fact that Sudanese community members are quoted at all suggests that the ‘status conferral function’ of the media has taken place – the appearance of the Sudanese community leaders in the news leads the

average person to conclude that these leaders must be important (Johnson-Cartee, 2005, p.162).

In contrast to the 61% of articles where Sudanese sources are used in

The Age, the Herald Sun only quotes from Sudanese sources in 22% of its

articles, ranking them as the third source type for the newspaper. This type of ‘symbolic annihilation’, as defined by Tuchman, happens when “people, groups, issues or objects are ignored or let out of news media coverage, they do not exist in the public sphere; and, therefore, they have no status or

legitimacy” (Johnson-Cartee, 2005, p.162). While Sudanese sources are not completely excluded from the Herald Sun, their minimal inclusion compared to police and victims and witnesses of violence acts as a ‘condensational

symbol’ to readers of Sudanese sources’ lack of legitimacy in the dialogue and debates surrounding their community. Even when the source is framed in positive light in one of the seven articles, when Sabah Jok, a Sudanese-Australian model, is highlighted for her success internationally, she is still quoted about crime committed by members of her community:

Of the crime problems in Melbourne, she said she was disappointed her community was being tainted by the actions of some. “It’s not really fair because it’s not a reflection of our community,’’ she said (Epstein, 2018).

Majavu explains that “everyday racism is both everywhere and

nowhere, consisting largely of silences and the careful failure to notice social interactions that are shaped by the logic of whiteness” (2018, p.192), and I would argue that the ‘loud silences’ of the lack of Sudanese sources in Herald

Sun news articles creates racialized frames that erode multiculturalism in

Australia.

Police, judges and lawyers appear in close percentages of articles in both The Age (39%) and the Herald Sun (45%). Despite ranking as the top source for the Herald Sun and third for The Age, this similar percentage

suggests that these sources are of similar importance at both newspapers, as well as a clear pattern of source standardization. However, their prominent use by both papers also triggers audiences to associate

Sudanese-Australians, in their entirety, and not individuals, with issues of criminality and violence, and serves to ‘Other’ the entire community from a ‘majority white’ Australia where violence is not a defining feature of ‘belonging’ to a

community.

Another source group that is virtually excluded from the Herald Sun reporting is politicians, appearing in only 6% of news articles, compared to 52% of news articles in The Age. This contrast is then reversed when looking at the ‘victims of violence and witnesses to violence’ source group, with The

Age only including them in 17% of their articles, much below the 42% of

articles they appear in in the Herald Sun.

While The Age’s preference for elite, authoritative sources is reason enough to understand why their use of politicians as sources is so high, it doesn’t help explain why politicians are so rarely used as sources in the

Herald Sun, or why each newspaper values ‘victims of violence and witnesses

to violence’ sources so differently.

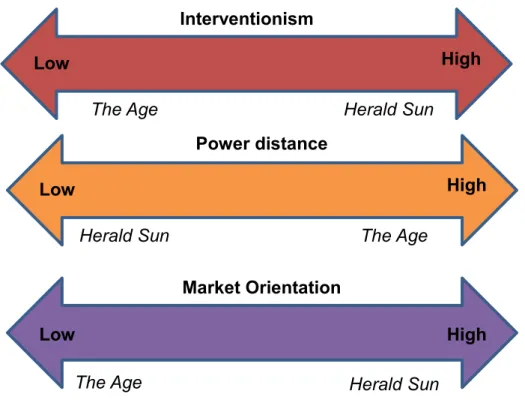

To understand this, we must look at each paper through their

‘newsroom frames’, or as Hanitzsch describes it, each newsroom’s perception of their institutional roles in relation to three basic dimensions: interventionism, power distance and market orientation (2007, p.372). Each newsroom will perceive their “normative responsibilities and functional contribution to society” (Hanitzsch, 2007, p.371) on a low to high scale for each dimension (see Figure 2).

Interventionism “reflects the extent to which journalists pursue a particular mission and promote certain values” (Hanitzsch, 2007, p.372). Newsrooms on the ‘passive’ (low) end of the scale believe journalists should function as gatekeepers, and uphold principles of objectivity, neutrality and impartiality; while on the ‘intervention’ (high) end of the scale newsrooms believe journalists function as ‘advocates’ and ‘participants’ in society and should take a more active and assertive role in their reporting (Hanitzsch, 2007, pp.372-373).

Power distance refers to whether newsrooms consider themselves an ‘adversary’ (high) to those in power, acting as the ‘fourth estate’ and

‘watchdogs’ of government’ or ‘loyal’ (low) to those in power and often being highly paternalistic towards ‘the people’ and see themselves as guiding public opinion (Hanitzsch, 2007, pp.373-374). Finally, market orientation in

newsrooms is high when readers are treated like consumers, lifestyle journalism takes a central role, and the personal fears and emotional

experiences of readers take centre stage; but it is low in newsrooms that treat readers as citizens who need to be informed to serve the ‘public interest’ (Hanitzsch, 2007, pp.374-375).

Figure 2. Journalism’s institutional role perceptions

To determine where each newsroom considers itself on this scale we must look to various statements of intent. For the Herald Sun, this was easy enough to find on their About Us page on their website:

Low

Interventionism

High

The Age Herald Sun

Low Power distance High The Age Herald Sun Low Market Orientation High