English Studies – Linguistics BA Thesis

15 Credits Spring 2018

Supervisor: Maria Wiktorsson

Embodiment in Proverbs:

Representation of the eye(s) in English, Swedish, and Japanese

Jessica Berggren

Table of contents ABSTRACT 3 1 INTRODUCTION 4 1.1 Aim 4 1.1.1 Research questions 5 2 BACKGROUND 5

2.1 Proverbs and Paremiology 5

2.2 Embodiment 8

2.3 Conceptual Metaphor Theory 9

2.4 Concept of Eye(s) in English, Swedish, and Japanese 11

2.4.1 English and Swedish concept of eye(s) 12

2.4.2 Japanese concept of eye(s) 12

2.5 Previous Works 13

3 DESIGN OF THE PRESENT STUDY 14

3.1 Method 14

3.2 Material 15

4 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 16

5 CONCLUDING REMARKS 27

Abstract

This study will examine the representation and embodiment of the body part eye(s), in proverbs. The research is cross-linguistic as the proverbs analysed are in the languages English, Swedish, and Japanese. Information about the origins of proverbs, their expansion across the globe, their use in order to embellish everyday communication in all different types of languages, even those belonging to cultures not similar to the Western norm, will be

discussed with references to sources based in the area of Paremiology. The study will also investigate cultural markers found in the proverbs and how the metaphoric interpretations of eye(s) are displayed through our bodily experiences. In order to analyse the representation of eye(s) in the proverbs, through metaphoric concepts, this study will employ Lakoff and Johnson’s conceptual metaphor theory. Categories which will accompany the conceptual metaphors are based on one of the Oxford English Dictionary’s definitions of ‘eye’.

Thereafter, an analysis is conducted regarding eyes(s) in the example proverbs. The results of the analysis showed that there are quite a few similarities in all three languages. However, the western languages differ from the Japanese language in regards to how the proverbs are worded. Further, cultural markers could only be found in one example in the Japanese proverbs.

Keywords: proverbs, conceptual metaphor theory, embodiment, cross-linguistics, Paremiology

1 Introduction

They are found far back in historical writings, all over the globe, and are to this day being used, embellishing our languages with their metaphoric phrasing, and expressing fundamental values found in our different cultures. What I am describing here is figurative expressions known as proverbs.

Metaphorical elements are often included as being a mandatory part of proverbs (2014), as claimed by Neal R. Norrick, which is part of why proverbs are interesting phrases to analyse, since the metaphoric features can be interpreted in a variety of ways. One of these ways in which this study will delve deeper into is how body parts are abstractly

conceptualized through embodiment, which in this specific study will be confined to focusing on the embodiment of the eye(s).

In the domain of cognitive linguistics, George Lakoff and Mark Johnson are two prominent people who have contributed with theories that introduce ‘conceptual metaphors’, which proposes that human beings in order to comprehend abstract and metaphoric concepts, use well known basic categories and our own experiences to form a connection. The way in which this occurs is according to Ning Yu that, ‘the mind emerges and takes shape from the body with which we interact with our environment’ (2014, p. 227).

Eyes are vital organs, as it is through these that we observe the world and are able to see in what way our interactions shape our experiences. In human communication, they are also a key part regarding the ability of expressing emotions and sharing our inner life with our fellowmen. Since the eyes have the ability to outwardly share our emotional state, they may be the most natural choice of body part for metaphoric expressions regarding the mind and the abstract. As it is commonly used in this regard for expressions in Western cultures, it is of interest to see if this notion is also shared with other cultures, such as those in East Asia. 1.1 Aim

The aim of the study is to investigate if there are similarities, from a semantic aspect,

regarding the use of a part of the body in proverbs, specifically the eye(s). The main purpose is to see if, and how, this body part is used similarly or differently over three different languages. The research will examine proverbs in Swedish and English, which have a common ground due to belonging to the same language family. It will also investigate if any

similarities can be found when looking at the same aspects in Japanese, which belongs to a different type of language family, and is from a completely dissimilar culture.

1.1.1 Research questions

• If the proverbs over the three languages have similar metaphoric interpretations, are there ways in which they differ from each other in regard to how eye(s) is represented? If so, in what ways?

• Cultural filters are inseparable in regard to how we understand metaphoric concepts, but how are cultural markers represented in the proverbs, if there are any?

2 Background

This section will, to begin with, introduce the origin and definition of proverbs as well as discuss the philological research area of ‘Paremiology’, which is the study of proverbs. Thereafter, the concept of ‘embodiment’, and Lakoff and Johnson’s ‘conceptual metaphor theory’ will be explained in regard to the above mentioned research questions and main aim of the study. Following this, an investigative look at the concept of eye(s) and its role in the three different cultures and languages being analysed will be demonstrated. Finally, previous work related to what this study aims to investigate, will be presented.

2.1 Proverbs and Paremiology

A proverb is a short complete sentence of wisdom or general advice, often structured in a figurative way with a literal and underlying meaning. This two way meaning leads to giving people an opportunity to add a meaning to the proverb on their own, depending on their specific situation (Holm, 1964). A criterion for proverbs is that they have to include some form of tradition; they need to be established and well-known expressions, that may or may not be from an older time. The ability of forming its own complete utterance is partly what distinguishes the proverb from other traditional figurative sayings, such as proverbial phrases, clichés, idioms, et cetera (Norrick, 2014).

As lightly touched on previously, proverbs contain wisdom and traditional views which often correlates to the times of when they were created, most of which, according to Norrick, come from before the era of industrialization which he argues can be seen in their rustic imagery (Norrick, 2014). They also often give potential advice grounded on experience, or suggest a course of action such as giving a warning about potential dangers, of varying degrees, in certain situations. Proverbs may even occur in a variant form of themselves, as

well as be altered or truncated. As an example of this we have the proverb ‘Speak of the devil…and he’s bound to appear’, where the unit in cursive is often omitted. The proverb’s core is understood even if only the first part of the proverb is uttered. This demonstrates that one would still be able to recognise the proverb, no matter the language, as long as its core form is intact. This means that the metaphorical meaning is still understood, and the proverb would still be identifiable even if it has gone through some modification.

Norrick claims that proverbs are not created by a mass of people, but by the individual. However, that being said, the society need to accept it into their general everyday oral and written discourse, as well as have it appear with some frequency and distribution to be coined as a proverb (Norrick, 2014). In other words, it needs currency among the people. A proverb has to include wisdom and traditional aspects that we as humans can relate to and understand in regard to our everyday circumstances.

Paremiology is the study of proverbs; their origin, function, evolvement over time, and what it is that makes a proverb a proverb. Or as Widbäck phrases it: ‘[p]aremiology deals with the proverb as a unit and a phenomenon, and studies within the area can include proverbs’ form, use, meaning, occurrence and so on’ (2015, p. 162). Paremiologists have come to the understanding that, for most proverbs the original coiner is no longer known. This is common for proverbs as they in many cases are repeated over and over, by people in different places, and as time goes on the original creator will have been forgotten. This is then also a way of distinguishing the proverb from some of the other types of phraseological units; it is most often anonymous.

Many of the proverbs that are known and used in this day and age, come from the Bible, and even as far back as the Ancient Roman and Greek times. However, even though the first ever written recoding of some proverbs stem from this time, there is no way of knowing how long before the written recordings were made, that the proverbs were used in spoken conversation (Mieder, 2015; Svartvik, 2004). As Mieder so eloquently writes, ‘it has long been noticed that some proverbs known in identical wording in most European languages can at least be traced back to Greek and Roman sources, always with the caveat that they might in fact be considerably older than their earliest written record so far’ (2015). According to Widbäck, ‘[p]roverbs can be found as far back in time as approximately 4000 years ago; they have been found in Egyptian hieroglyphics, in Babylonian cuneiform script, in the Norse Poetic Edda and in the Bible’ (2015, p. 160). Some proverbs in use today, with an origin in

Great Britain, started out as meaningful sayings or remarks by famous literary authors such as Geoffrey Chaucer or William Shakespeare, and they have over time turned into proverbs as they were, and still are, frequently repeated among the people (Mieder, 2015). Something to note here is that these authors did not actually create the proverb themselves, but that the continued use of their expression in the everyday life of the people turned it into proverb.

Going back to the slightly earlier origins of proverbs, and in this case those proverbs created within Europe, their origin has been traced back to the Greek and Roman times, as mentioned previously. Proverbs became widespread in Europe in a few different ways; through a variety of different fables, stories and tales, through the church and its sermons, which also leads to the spread of proverbs through Latin which in previous times was the language of the church, as well as frequently being used as the language of learning in schools. In terms of the proverbs spread in Europe through Latin, especially those of Greek and

Roman origins, came about due to translations and translation exercises being made over the continent. An excellent example of this would be Erasmus of Rotterdam’s title Adagia, published in the early 1500s, containing a collection of proverbs translated from their Greek and Roman sources.

This title was part of the borrowing and adopting of proverbs, into all types of different European cultures and languages. These proverbs have further on been spread to other parts of the world due to loan processes, many of which happen as a result of our more current globalisation. However, as Mieder touches upon; some proverbs are very similar over different languages due to the fact that they express common ideas or phenomena, often in a more abstract way, which may have resulted in a proverb having more than one origin (2015, p. 34). This has been observed by Daniel Crump Buchanan in his book Japanese Proverbs and Sayings, which will be the main source regarding the Japanese proverbs in this study, where he writes:

In addition, with the opening of Japan to the West, quite a few English proverbs and some from other European languages were translated into Japanese and adopted by the people. There are also numerous Japanese and English proverbs that are similar in meaning, but no evidence of borrowing on the part of either. (Buchanan, 1965, p. xiv)

However, the adopting of English proverbs into other languages is much due to the change from Latin being the lingua franca of Europe, to English taking its place and continuously also taking over as a prominent language over the globe. The English language, in its various

forms, have become a communicative tool which unites us all over the globe, and thus also leading to the English version of a proverb being loaned or adopted into languages and cultures all over the world.

2.2 Embodiment

One definition of embodiment as disputed by Ning Yu is:

The term embodiment, as suggested by the root of the word itself, has to do with the body, but it is really about how the body is related to the mind in the environment, and how this relationship affects human cognition. The basic idea behind embodiment is that the mind emerges and takes shape from the body with which we interact with our environment. Human beings have bodies, and human embodiment shapes both what and how we know, understand, think, and reason. (Yu, 2014, p. 227)

First and foremost, we humans are to the core bodily beings and the human cognition is achieved through our bodily experiences as we come into contact with our surroundings. We create and gain experience through actions performed through our bodies, and can therefore in a later state use that experience to understand and relate to metaphoric expressions.

Embodiment is of interest within Cognitive Linguistics, and according to Yu, ‘the findings of cognitive linguistic studies have shown that human minds are embodied in the cultural world, and human meaning, feeling, and thinking are largely rooted in bodily and sociocultural experiences’ (2014, p. 233), which illustrates that the embodiment seen in expressions, may have different understandings depending on where in the world we have gained it and through which culture we have formed our thoughts and values.

When it comes to understanding the relationship of how embodiment is used in

language, Gibbs claims that, the embodied nature of linguistic meaning demands that we look for mind-body and language-body connections in order to understand the relationship (2003). Gibbs continues by stating that embodiment shapes why words or phrases have the meanings that they do, as well as people’s intuitions about, and immediate understanding of, that

specific meaning in all the different types of linguistic language units, words, phrases, etcetera (2003).

Embodiment is also present when researching language in terms of Lakoff and

Johnson’s conceptual metaphor theory, which will be discussed in more detail in the section below. In Gibbs article “Embodied Experience and Linguistic Meaning”, he summarises findings made in Lakoff and Johnson’s work, mentioning that, ‘[t]here is a large body of work

in cognitive linguistics suggesting that much metaphorical thinking arises from recurring patterns of embodied experience’ (2003, p. 6). In other words, the claim is that embodiment and metaphorical, or abstract, thinking go hand in hand when coming to an understanding of expressions or phrases in a language. All of this is of importance in the studies of human cognition, and ‘the relationship between body, mind, and culture’ (Maalej & Yu, 2012). 2.3 Conceptual Metaphor Theory

Conceptual Metaphor Theory is part of cognitive linguistics, thereby dealing with the human mind and its understanding of abstract entities in language. The theory, as can be seen from the name, has its main focus around conceptual metaphors in language. It involves the understanding of one conceptual domain, or an idea, in terms of another. Or as Lakoff and Johnson disputes, ‘[m]etaphorical concepts provide ways of understanding one kind of experience in terms of another kind of experience’ (1980a, p. 486). They continue this

explanation by adding that, ‘[m]any concepts are defined metaphorically, in terms of concrete experiences that we can comprehend, rather than in terms of necessary and sufficient

conditions’ (1980a, p. 486), which relates to that the fact that even though many concepts are similar globally, there are filters through which these concepts are understood differently as the cultures over the world may, and many times do, have different ways of comprehending experiences through these conceptual metaphors.

Lakoff and Turner, explains a way in which we are able understand conceptual metaphors through different domains by claiming that:

Basic conceptual metaphors are part of the common conceptual apparatus shared by members of a culture. They are systematic in that there is a fixed correspondence between the structure of the domain to be understood (e.g., death) and the structure of the domain in terms of which we are understanding it (e.g., departure). We usually understand them in terms of common experiences. They are largely unconscious, though attention may be drawn to them. Their operation in cognition is almost automatic. And they are widely conventionalized in language, that is, there are a great number of words and idiomatic expressions in our language whose meanings depend upon those conceptual metaphors. (Lakoff & Turner, 1989, p. 51)

Some of the categories of conceptual metaphors, those that we think and live by, are overlapping. Three of these categories are further discussed in Lakoff and Johnson’s

“Metaphors We Live By” (1980b), although only two of them will be used in this study, and they are: structural metaphors, and ontological or physical metaphors.

Structural metaphors often deal with using a concept from one domain, in order to structure a concept from another domain. Lakoff and Johnson use ARGUMENT IS WAR as their conceptual metaphor, in order to show how using one concept from the source domain ‘WAR as a physical or cultural phenomenon’ to structure a concept from the target domain,

‘ARGUMENT as primarily an intellectual concept, but with cultural content’ (1980a, p. 461) in order to understand the figurative meaning of the expressions used to indicate an argument, such as for example ‘Your claims are indefensible.’ or ‘If you use that strategy, he’ll wipe you out.’, etcetera (1980a, p. 454).

Ontological metaphors, or the other definition being physical metaphors, ‘involve the projection of entity or substance status upon something that does not have that status

inherently’ (1980a, p. 461). According to Lakoff and Johnson, due to the ontological

metaphors’ conventional nature, they allow us to view emotions, ideas, events, activities and so on, as entities of a variety of purposes. They can function in terms of referring to these entities, categorise them, group them together, or even quantify them, as a few examples. In “Metaphors We Live By”, Lakoff and Johnson have a whole section on ontological metaphors, where they are described in terms of being containers and substances. A distinction they make between these types of purposes in terms of how we understand them through our bodily experiences is:

We use ontological metaphors to comprehend events, actions, activities, and states. Events and actions are conceptualized metaphorically as objects, activities as substances, states as containers. (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980b, pp. 30-31)

One of the most obvious ontological metaphor types, according to Lakoff and Johnson, is ‘where the physical object is further specified as being a person’ (1980b, p. 33), in other words; personification. Personification, in regard to ontological metaphors, is further developed and described carefully in more articulate words by Lakoff and Johnson, as follows:

The point here is that personification is a general category that covers a very wide range of metaphors, each picking out different aspects of a person or ways of looking at a person. What they all have in common is that they are extensions of ontological metaphors and that they allow us to make sense of phenomena in the world in human terms – terms that we can understand on the basis of our own motivations, goals, actions, and characteristics.(Lakoff & Johnson, 1980b, p. 34)

One thing that is at many times seen in personification metaphors are instances of metonymy, as it is also a way of relating to and understanding our everyday experiences. The concepts of metaphor and metonymy may be difficult to separate in terms of understanding them, but Lakoff and Johnson have kindly included explanations in their “Metaphors We Live By”, suggesting that:

Metaphor and metonymy are different kinds of processes. Metaphor is principally a way of conceiving of one thing in terms of another, and its primary function is understanding. Metonymy, on the other hand, has primarily a referential function, that is, it allows us to use on entity to stand for another. But metonymy is not merely a referential device. It also serves the function of providing understanding. (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980b, p. 36)

They continue on by mentioning that metaphor and metonymy to some extent serve the same purpose, in some occasions in somewhat similar ways, although metonymy allow for a more specific focus on specific aspects of what is being referred to (1980b, p. 37). The two

concepts are alike when it comes to not only structuring our language, but also our thoughts and actions, as both types of concepts have a base in our day to day experiences (1980b, p. 39).

As previously mentioned, culture affects our way of comprehending and understanding different concepts and figurative expressions. Even when dealing with metonymy in language, one should keep in mind that ‘the conceptual systems of cultures and religions are

metaphorical in nature’ (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980b, p. 40). Religions employ metonyms in their symbolism, like the conception of a dove in Christianity which is understood as a metonym for the Holy Spirit, as an example. These symbolic metonyms provide meaning between the everyday experiences and the metaphorical systems that are defining of religions and cultures (1980b, p. 40).

2.4 Concept of Eye(s) in English, Swedish, and Japanese

As previously mentioned in the above sections, culture is a defining factor when

understanding conceptual metaphors, and their many sub-categories. In this study the focus will be on the embodiment of the body part eye, or its plural form, in three different

languages; English, Swedish, and Japanese. However, before the analysis can begin some definitions need to be made regarding what the concept of eye(s) is in the languages, and what kind of role they have, physically and metaphorically, in their respective cultures. The

language and culture, and they will not take all the many different, and for this study perhaps not relevant enough, definitions into account.

2.4.1 English and Swedish concept of eye(s)

From personal experience, having lived in both countries, the representation of eye(s) in these two cultures is almost identical. Eye contact plays a large role in social interactions, as

looking into someone else’s eyes while communicating shows a sign of interest and respect. As mentioned by Lena Robinson in the article “Beliefs, Values and Intercultural

Communication”, ‘[e]ye contact during verbal communication is expected in Western culture because it implies attention and respect toward others’ (2004, p. 117). Robinson also claims in regard to this that, ‘[a]mong Asians, however, eye contact is considered a sign of lack of respect and attention, particularly to authority and older people’ (2004, p. 117). This demonstrates a distinction between the Asian and European, or a more Western, cultural behaviour, and this is something which will be discussed more in-depth in the section below regarding the eye(s) in Japanese culture. Furthermore, eye contact is also prevalent when interacting with a loved one, as that displays a sign of affection.

The role that eyes have in these two cultures, is that it is through these organs that we as people connect on an emotional but also intellectual level.

2.4.2 Japanese concept of eye(s)

The Japanese concept of eye(s) differs slightly from the general Western, specifically the Swedish and English, perception of the concept. Debra J. Occhi writes in her article “A Cultural-Linguistic Look at Japanese ‘Eye’ Expressions”, that ‘[t]he concept of ‘eye’ plays a significant role in Japanese language and culture, describing mental operations as well as emotional experience’ (2011, p. 190). This viewpoint one can argue is similar to that of how the Western culture perceives eyes. The ‘eye’ is also relevant for the Japanese as it expresses one’s character and emotion. The concept of emotions, or one’s inner feelings being

represented through the ‘eye(s)’, is further claimed by Kengo Tamura, in his comparative study focusing on proverbs in English and Japanese, where he states that, ‘[t]he Japanese in former times seem to have used their eyes to express and make known their delicate and complex feelings to others’ (2003, p. 102).

Japanese expressions containing a reference of ‘eye’ are supposed to depict a position from where the ‘eye’ is supposedly capable of judging and measuring across different

One significant cultural difference in Japanese, that is not a part in the Swedish or English culture, is the social hierarchical structure. According to Occhi, ‘Japanese describes social relationships as plotted along a vertical hierarchy; this social schema governs physical and speech behavior’ (2011, p. 177). This social schema, in regard to the eyes, is seen in everyday behavioural motions such as bowing and different types eye gazes, for example to avert the eyes and avoid direct eye contact with one’s superior as that would indicate a lack of respect. (Occhi, 2011, p. 177; Robinson, 2004, p. 117)

Occhi continues by discussing the role of ‘eye’ in Japanese expressions, and meaning that the eye is the centre for the social hierarchical distinctions that administer behaviour,

linguistic and bodily performance included (2011, p. 190). The eye(s) also portrays the norms regarding communication, and can reveal aspects of mentality, personality, and physical gender, in this case the biological sex one was assigned at birth (2011, p. 190).

2.5 Previous Works

Studies regarding metaphoric expressions such as proverbs have previously been conducted, however they are a minority compared to studies dealing with other figurative expressions. There are also numerous studies researching the use of embodiment in everyday expressions, studies analysing language in terms of conceptual metaphors, or analysing phrases cross-linguistically by comparing terms in different languages. However, more often than not the comparisons are only between two languages, and there are commonly only cross-linguistic research between some of the countries in East Asian and the Unites States of America. Studies like this are not often available from a European and Asian perspective, and even less so if the European language analysed is not English.

With this in mind, there are some studies regarding cross-linguistic research on proverbs, the use of embodiment in everyday expressions, or in some cases a mix of the two, that have been conducted. “An Analysis of the Cognitive Dimension of Proverbs in English and Spanish: the Conceptual Power of Language Reflecting Popular Believes” by Ana Ibáñez Moreno is one of these studies, where the research has been focused on the cognitive structures at work in proverbs, to afterwards make a cross-linguistic analysis of metaphoric and metonymic phenomena in Spanish and English proverbs (2005, p. 53). Moreno used a compilation of proverbs from different sources, in both Spanish and English, to make a general comparative analysis comparing the proverbs found in the two languages. The study illustrates a clear example on how one can potentially carry out a cross-linguistic analysis

using proverbs. The study, however, does not incorporate anything in regard to human embodiment, as it instead lay focus on culture specific proverbs containing the animal dog.

Another fairly recent study by Ning Yu’s with the title, “Metaphor from Body and Culture” (2008), also incorporates cross-linguistic analysis, though this study focuses on Chinese and English. The approach of research carried out by Yu is different than Moreno’s approach, as he uses a newer approach to Lakoff and Johnson’s conceptual metaphor theory, using decompositional analysis to demonstrate how the human body and our culture work together to create emergence of metaphors (p. 247). Yu also incorporates elements of

embodiment as he is focusing on the body part terms used for face in Chinese and English in the emerging metaphors.

These two essays, though they are not similar in their main aims, both conduct

researches that are similar to what this study is set out to perform, and has provided me with information which can be incorporated in this study.

3 Design of the present study

In this section, the methods used for the analysis will be presented. Further, the material from which the proverbs are collected, as well as limitations regarding the data will be covered. Material in support of the concepts employed in the analysis will be discussed.

3.1 Method

The main method that will be applied is Lakoff and Johnson’s Conceptual Metaphor Theory, and the method will be supported by articles that have used this theory for similar researches. The articles mentioned in the previous works section will contribute to the framework for how I will conduct this study’s analysis. The study will focus on the representation of eye(s) in the three languages, concentrating on their metaphoric and metonymic concepts.

It also needs to be mentioned that for all the examples of proverbs, the metaphoric interpretations of eye(s) is done by myself, and thus another person may find that another metaphoric interpretation is more suitable than the ones I have chosen.

In order to decide the metaphoric interpretation for each proverb’s representation of eye(s), I employed the following analysis pattern, shown here using an example proverb from Table 3 (see in Results and Discussion section):

To begin with, the literal meaning of eye in the proverb had to be established, and in the above example eye is grouped together with the verb see, which is the main activity that this particular sensory organ does as part of the human body. Therefore, it is concluded that the eye has at least one meaning, which is the literal one. Thereafter, I wanted to define what the intended meaning of the proverb as a whole was, in this case I concluded that the meaning was ‘You won’t (or can’t) miss what you have never known’. With this in mind I deducted that if the proverb is about what one has never known, then the eye represent POWER OF OBSERVATION, and would therefore fall under that subcategory. The being who lacks a certain information can only gain knowledge about it through perceiving it; and therefore one can dispute that the eye is a gateway to awareness.

The concepts under which the representation of eye(s) will be analysed are partly based on Lakoff and Johnson’s conceptual metaphor examples in “Metaphors We Live By” that are related to vision (1980b, pp. 48, 50): THE EYES ARE CONTAINERS FOR THE EMOTIONS, and UNDERSTANDING IS SEEING. However, though base is from these conceptual metaphors, the categories to be followed in this study will be an alternative to Lakoff and Johnson’s definitions created specifically for this study, and they are partly created with information from the Oxford English Dictionary’s definitions on ‘eye’, and therefore the study will be analysed from a perspective grounded in the English language, which needs to be taken into consideration regarding the analysis.

3.2 Material

For the analysis, proverbs had to be chosen in all three languages. As there were different amounts of proverbs with mention of eye(s), in the different languages, and the available sources of data found were from different time periods, the proverbs were chosen with this information in mind. However, the criteria I had when choosing the proverbs were based on that they should still be somewhat applicable to our modern day, and they should be

understood without much difficulty. The proverbs used in the analysis are only to be seen as examples, as there are many proverbs with an incorporation of eye(s) in them, and for this specific research it is not relevant or even a possibility to analyse all of them.

For this study there are 8 examples of Japanese proverbs, 10 examples of Swedish proverbs, and 10 examples of English proverbs, all with a representation of eye(s) in them. The data for the Japanese proverbs are taken from Daniel Crump Buchanan’s book Japanese Proverbs and Sayings (1965). The data for the Swedish proverbs are taken from Pelle Holm’s

book Ordspråk och Talesätt (1964). The data for the English Proverbs are taken from the 6th

edition of the Oxford Dictionary of Proverbs (2015) edited by Jennifer Speake, and from Dictionary of Proverbs (Wordsworth Reference) (2006) by George Latimer Apperson. Tables with all of the proverbs can be found in the results and discussion section of this paper, including English translations for the Japanese and Swedish proverbs. All Japanese proverb examples are included in Table 1, all Swedish proverbs in Table 2, and all English proverbs in Table 3. I have also adopted a cross-linguistic perspective on the study, since this study will be dealing with proverbs from three different languages.

The eye(s) representation in all examples of the proverbs are underlined; in Swedish the equivalent is, with a few variations depending on grammatical aspects, ‘öga’, and in Japanese the word representing eye is ‘me’. It should be noted for the Japanese proverb examples, that they are spelled out with the roman alphabet’s letters and not in any of the three Japanese equivalent alphabets; hiragana, katakana, and kanji. The use of roman letters to spell out the Japanese language in text is referred to as romaji. Buchanan motivates his choice of alphabet use by stating that for the time of the title’s publication, ‘[s]pace and printing limitations have precluded setting forth the proverbs in Japanese and Chinese type’, however, ‘the printing of the Japanese proverbs in Latin letters is sufficient to give some idea of their pronunciation’ (1965, p. xiv), and since this study employs data from Buchanan’s writing I have deliberately chosen to adhere to his choice of alphabet.

Yu’s article “Embodiment, Culture, and Language” (2014) will be a ground when examining if and how the conceptual metaphors present a relationship between embodiment concept and culture aspect. This could then lead to enforcing the value of culture in regard to the understanding of metaphoric expressions, with emphasis on those incorporating the body.

4 Results and Discussion

In this section, the proverbs will be categorised into different concepts depending on the metaphoric interpretation of eye(s) in each example. However, to make the results and discussion of the study easier to follow when discussing examples, the proverbs chosen for each language can be seen in the tables below, each one assigned a number:

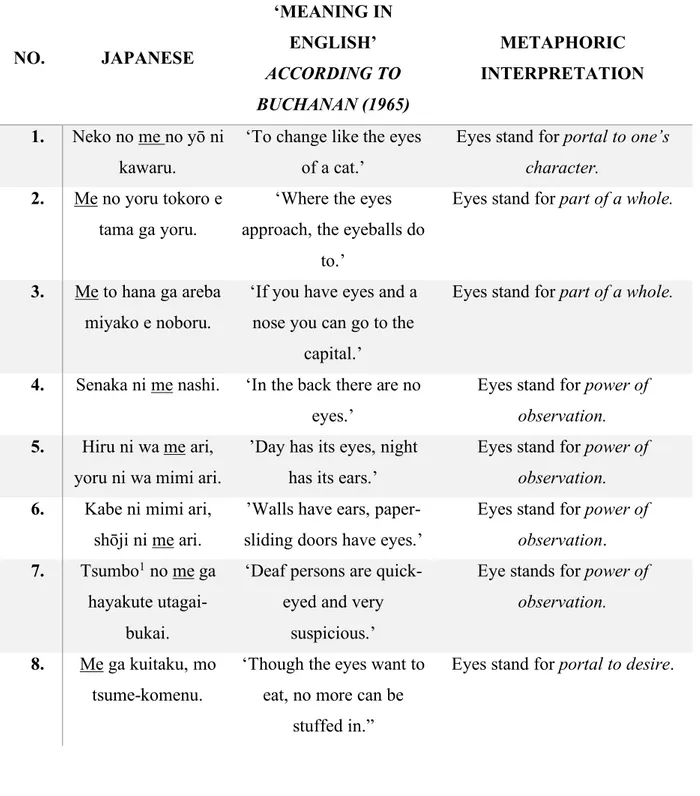

Table 1. Examples of proverbs in Japanese with the word eye(s)

1 Tsumbo is a derogatory word for a deaf person, and is in current times seen as a dead word. (Nakamura, 2006,

p.109.) (See references for full source.)

NO. JAPANESE ‘MEANING IN ENGLISH’ ACCORDING TO BUCHANAN (1965) METAPHORIC INTERPRETATION 1. Neko no me no yō ni kawaru.

‘To change like the eyes of a cat.’

Eyes stand for portal to one’s character.

2. Me no yoru tokoro e tama ga yoru.

‘Where the eyes approach, the eyeballs do

to.’

Eyes stand for part of a whole.

3. Me to hana ga areba miyako e noboru.

‘If you have eyes and a nose you can go to the

capital.’

Eyes stand for part of a whole.

4. Senaka ni me nashi. ‘In the back there are no eyes.’

Eyes stand for power of observation. 5. Hiru ni wa me ari,

yoru ni wa mimi ari.

’Day has its eyes, night has its ears.’

Eyes stand for power of observation. 6. Kabe ni mimi ari,

shōji ni me ari.

’Walls have ears, paper-sliding doors have eyes.’

Eyes stand for power of observation. 7. Tsumbo1 no me ga

hayakute utagai-bukai.

‘Deaf persons are quick-eyed and very

suspicious.’

Eye stands for power of observation.

8. Me ga kuitaku, mo tsume-komenu.

‘Though the eyes want to eat, no more can be

stuffed in.”

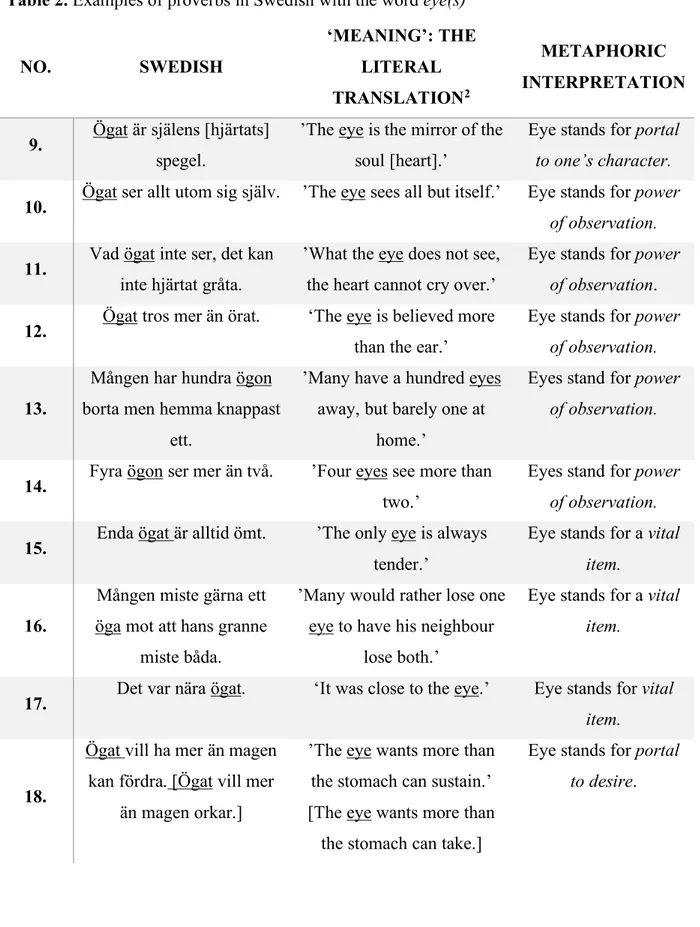

Table 2. Examples of proverbs in Swedish with the word eye(s) NO. SWEDISH ‘MEANING’: THE LITERAL TRANSLATION2 METAPHORIC INTERPRETATION 9. Ögat är själens [hjärtats]

spegel.

’The eye is the mirror of the soul [heart].’

Eye stands for portal to one’s character. 10. Ögat ser allt utom sig själv. ’The eye sees all but itself.’ Eye stands for power

of observation. 11. Vad ögat inte ser, det kan

inte hjärtat gråta.

’What the eye does not see, the heart cannot cry over.’

Eye stands for power of observation. 12. Ögat tros mer än örat. ‘The eye is believed more

than the ear.’

Eye stands for power of observation.

13.

Mången har hundra ögon borta men hemma knappast

ett.

’Many have a hundred eyes away, but barely one at

home.’

Eyes stand for power of observation.

14. Fyra ögon ser mer än två. ’Four eyes see more than two.’

Eyes stand for power of observation. 15. Enda ögat är alltid ömt. ’The only eye is always

tender.’

Eye stands for a vital item.

16.

Mången miste gärna ett öga mot att hans granne

miste båda.

’Many would rather lose one eye to have his neighbour

lose both.’

Eye stands for a vital item.

17. Det var nära ögat. ‘It was close to the eye.’ Eye stands for vital item.

18.

Ögat vill ha mer än magen kan fördra. [Ögat vill mer

än magen orkar.]

’The eye wants more than the stomach can sustain.’ [The eye wants more than

the stomach can take.]

Eye stands for portal to desire.

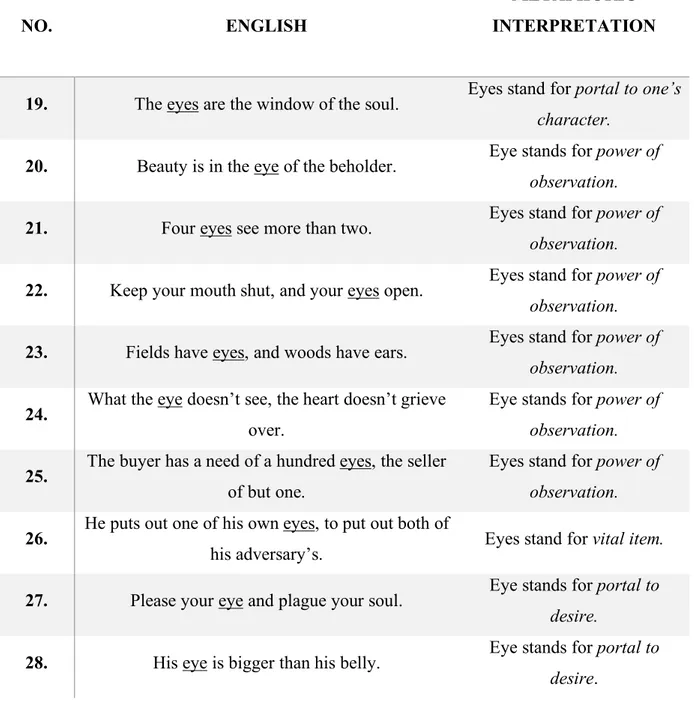

Table 3. Examples of proverbs in English with the word eye(s)

NO. ENGLISH

METAPHORIC INTERPRETATION

19. The eyes are the window of the soul. Eyes stand for portal to one’s character.

20. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Eye stands for power of observation. 21. Four eyes see more than two. Eyes stand for power of

observation. 22. Keep your mouth shut, and your eyes open. Eyes stand for power of

observation. 23. Fields have eyes, and woods have ears. Eyes stand for power of

observation. 24. What the eye doesn’t see, the heart doesn’t grieve

over.

Eye stands for power of observation. 25. The buyer has a need of a hundred eyes, the seller

of but one.

Eyes stand for power of observation. 26. He puts out one of his own eyes, to put out both of

his adversary’s. Eyes stand for vital item. 27. Please your eye and plague your soul. Eye stands for portal to

desire.

28. His eye is bigger than his belly. Eye stands for portal to desire.

The proverbs presented in the tables all have a literal meaning, as in they can all be interpreted with the information of what the human conception of eye(s) is which is the physical representation of the eye. However, all proverb examples also have a second meaning which is the metaphorical. This metaphorical meaning can be interpreted through another concept which the eye in each example is embodying. The metaphoric interpretations as seen in the tables, are used main categories in which different types of sub-categorical metaphoric meanings are represented. However, not all proverbs are grouped under a subcategory, as some of them can in my opinion be interpreted in different ways and I feel

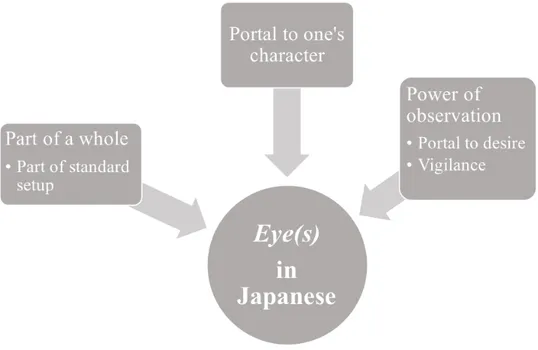

uncertain about grouping them under a specific subcategory, and so they are therefore only grouped under the main category. The subcategories can be seen in the figures below, where they will also be explained and discussed further.

The analysis pattern, regarding the process of deciding the metaphoric interpretations, as described using an example proverb in the method section above, has also been employed for all other proverbs in Tables 1 through 3.

In relation to Lakoff and Johnson’s categories of conceptual metaphor examples as mentioned in the method section, namely: THE EYES ARE CONTAINERS FOR THE EMOTIONS, and UNDERSTANDING IS SEEING, it is possible to subcategorise this study’s own conceptual

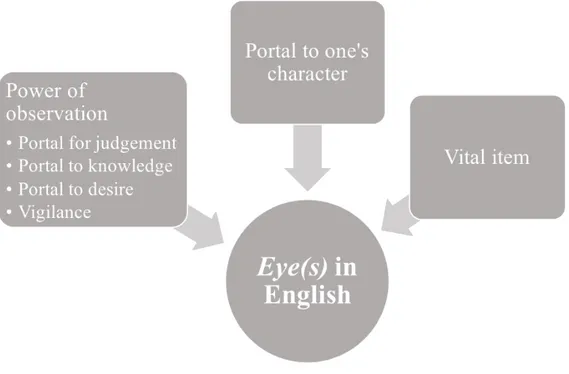

metaphor categories under them based on the metaphoric interpretations of the proverbs which can be found in the tables. The categories which are specific for this analysis are VITAL ITEMS, PART OF A WHOLE, POWER OF OBSERVATION, and PORTAL TO ONE’S CHARACTER.

One can assign these categories of conceptual metaphors in relation to the study’s main concept of eye(s), within already understood conceptual metaphors, THE EYES ARE

CONTAINERS FOR THE EMOTIONS and UNDERSTANDING IS SEEING (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980b, pp. 49, 50), as follows:

THE EYES ARE CONTAINERS FOR THE EMOTIONS: à EYES ARE VITAL ITEMS/EYES ARE THE

PORTAL TO ONE’S CHARACTER.

UNDERSTANDING IS SEEING:à EYES ARE PART OF A WHOLE/POWER OF OBSERVATION IS IN

ONE’S EYES/EYES ARE VITAL ITEMS

The motivations behind these categorisations are, that regarding THE EYES ARE CONTAINERS FOR THE EMOTIONS: since the eyes can be seen as containers for the emotions, they become

vital items, as each human has normally only one pair of eyes, and it is through these that one’s emotions are being shown. The motivation is similar in regard to eyes being the portal to one’s character. People’s characters are often shown by how they let their emotions affect their actions, and these emotions can be seen in the eyes.

The motivations regarding the categorisations for UNDERSTANDING IS SEEING are:

since understanding can be achieved though seeing, eyes being a part of a whole has a more literal meaning. Two eyes make up the whole, and by seeing with full vision one has a greater chance of being aware of what goes on in the surroundings and therefore have an easier time

to comprehend the experiences being formed. Regarding the power to observe, the

explanation is slightly simpler, which is that through our eyes one can gain knowledge by seeing and thus gain a greater understanding of the world. Eyes being vital items in regard to how vision is connected to understanding, shows that without these vital organs one’s chances of gaining knowledge are limited.

One can now divide the proverbs into the categories, which will provide a clearer stance on which types of conceptual metaphors they are connected with. For some of the categories, namely PART OF A WHOLE and POWER OF OBSERVATION, the metaphoric interpretations have been divided into subcategories within the main category. POWER OF OBSERVATION has been divided into the subcategories of PORTAL FOR JUDGEMENT, PORTAL FOR KNOWLEDGE, PORTAL TO DESIRE, and VIGILANCE. These subcategories are not occurring in all of the three languages, as one can see by looking at the tables and the figures, which will be incorporated further down in the discussion. The reason for this could be due to the limitations regarding the sources and variations of the proverbs chosen, however, the study will be conducted with this information in mind. The subcategories all still fall under the main category of POWER OF OBSERVATION, only that they have specific contexts within their

metaphoric interpretation that needs further categorizing. That being said, there are some proverbs which only fall under the main category due to, in my opinion, having too many ways of being interpreted that it would be difficult to subcategorise them into a specific one and therefore I have chosen to keep them contained within the main category. It should however be duly noted that the choices regarding how I have categorised these proverbs is certainly not the only way they can be interpreted or categorised. For instance, the proverb examples under the VIGILANCE subcategory, namely example 4, 5, 7, 13 and 22, could have just been categorised under the main category as POWER OF OBSERVATION. However, the difference regarding those examples that separate them slightly from the others, is that the context for those proverbs is that the power to observe regarding the eye in those instances is an appeal to be vigilant. Therefore, even though those proverbs are listed under the main category, they will be acknowledged through the subcategory, as their context and metaphoric interpretation is specific to the topic of vigilance.

One other possible exception within these subcategories concern EYES BEING PORTALS TO DESIRE. I have made the decision to incorporate this under the category of POWER OF OBSERVATION IS IN ONE’S EYES as it is through our eyes and our ability to observe the world

what we see, as even a blind person can have a desire for certain things as the other sensory organs provide other experiences one can greed for.

PART OF A WHOLE has the subcategory of PART OF THE STANDARD SET UP. This

interpretation is also quite literal in its sense, seeing as a pair of eyes are part of the human’s bodily construction. Regarding the PART OF A WHOLE, and also the VITAL ITEM, proverb examples, there are more difficulties with separating the literal and metaphorical as they go hand in hand with each other. Both the literal and the metaphorical interpretations are of importance. Eyes are in the literal sense vital body parts as they are the only visual organs we have, and they are part of a whole as they, in most cases, are created biologically as a pair. Yu mentions in regard to embodiment that, ‘[the] mind is never separate from the body, for it is always a series of bodily activities immersed in the ongoing flow of organism-environment interactions that constitutes experience’ (2014, p. 230). I have with that statement in mind made the choice of viewing the metaphorical sense of eye(s) in the proverbs as part of the literal, because without knowing the literal physical organ’s value one cannot perceive the important connection between the abstract knowledge, emotion, and connection to the mind that is held within the core of the organ, and thus unifying the abstract and the literal. As a metaphor, I have interpreted VITAL ITEM and PART OF A WHOLE as a unification for one’s inner world and identity.

The main category THE EYES ARE PORTALS TO ONE’S CHARACTER, is slightly special

in that the meaning is being understood from an outside observer’s perspective, as opposed to other observations which is made within oneself, as is the case with the other subcategories grouped under POWER OF OBSERVATION.

The different languages examples of proverbs and their metaphorical categories can be seen respectively in the three figures below:

Figure 1. Metaphoric expressions of eye(s) in Japanese proverbs

Figure 3. Metaphoric interpretations of eye(s) in English proverbs

Here is a compilation of all the examples put together with their more in depth categories, in order to make it clearer which proverb falls under which specific category. Example 6, 10, 11,12, 23, and 25 are categorised under the main category POWER OF OBSERVATION. Example 4, 5, 7, 13, and 22 are subcategorised under VIGILANCE. Example 8, 18, and 28 are

subcategorised under PORTAL TO DESIRE. Examples 14, 21, and 24 are subcategorised under PORTAL FOR KNOWLEDGE, due to the eye(s) being understood metaphorically as a gateway to attain knowledge about the world and one’s experiences. Examples 20 and 27 are

subcategorised under PORTAL FOR JUDGEMENT, due to the eye(s) being understood

metaphorically to hold some power of judging the outside world. 1, 9, and 19 are examples of the category PORTALS TO ONE’S CHARACTER. Example 2 is categorised under PART OF A WHOLE, and example 3 is subcategorised under PART OF STANDARD SETUP, due to the eye(s) being metaphorically understood as being nothing out of the ordinary. Lastly, examples 15, 16, 17, and 26 are categorised under the main category VITAL ITEM.

It should be noted here in regard to the previous discussion of literal versus

metaphorical interpretation and meaning, that these types of examples do not occur in just the categories PART OF A WHOLE and VITAL ITEM but also in for example POWER OF OBSERVATION. In example 14 and 21, it is easy to see the literal meaning. ‘Four eyes see more than two’ and ‘Fyra ögon ser mer än två’, where the literal meaning is understood as, the more people there are seeing something the wider the spectrum of that something is. However, the metaphorical

interpretation of the proverbs as I have categorised it, is under POWER OF OBSERVATION in the subcategory PORTAL FOR KNOWLEDGE. The metaphorical understanding of eye(s) can be taken as being the portal to knowledge due to the fact that eye(s) implies an access to attain

knowledge. The fact that eyes is written in the plural adds to the meaning that there is a wider access of knowledge that can be attained. However, these two ways of interpreting the

proverbs, as in the literal and the metaphorical, can seem very similar. The metaphoric

meaning has an implied understanding of having the quality of attaining knowledge about the world. Those two proverbs are what Lakoff and Johnson call literal metaphors or

conventional metaphors. According to them a conventional metaphor is, ‘treated as if it were always the result of some operation performed upon the literal meaning of the utterance’ (1980b, p. 453), which can be noticed in the metaphoric interpretations of these two proverb examples.

By viewing the tables, and also the more compact version of the proverbs’

metaphorical interpretations in the figures, I noticed that one of the main categories, POWER OF OBSERVATION IS IN ONE’S EYES, is found in all three languages. Of this specific metaphor,

there is four instances in the Japanese proverbs, as can be seen from Table 1 example 4, 5, 6 and 7. There are five instances in the Swedish proverbs, as can be seen from Table 2 example 10, 11, 12, 13, and 14. Six instances in the English proverbs, as can be seen from Table 3 example 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 and 25.

However, any of the subcategories under POWER OF OBSERVATION IS IN ONE’S EYES,

are also apparent in the three languages to some extent. The one subcategory that differs and is included in all languages, is the concept of EYES BEING PORTALS TO DESIRE. What is interesting regarding this specific concept is the way the proverbs are expressed, or at least how the meaning based off the translations are being implied. There are two examples of this in table 3, number 27 and 28. However, I shall be focusing on example 28.

(8) Me ga kuitaku, mo tsume-komenu.

‘Though the eyes want to eat no more can be stuffed in.’

(18) Ögat vill ha mer än magen kan fördra. [Ögat vill mer än magen orkar.]3

‘The eye wants more than the stomach can sustain. [The eye wants more than the stomach can take.]’

(28) His eye is bigger than his belly.

When looking at these proverbs, I noticed similarities between the way the English and Swedish proverbs are worded. They both use embodiment of eye as the PORTAL TO DESIRE which is the source from where we base our understanding, and the recipient of that desire being embodied by the belly/stomach. As Yu mentions, ‘[e]mbodiment refers to patterns of human behaviour enacted on the body and expressed in the bodily form’ (2014, p. 231), the recipient part of the proverbs has been embodied using the belly/stomach, which humans from experiences know is an organ which can be filled and expanded to a certain extent, which then allows us to understand the metaphoric concept regarding the desire which can push past the boundaries.

The chances of the similarities regarding this particular proverb in English and Swedish, are not too surprising as they both belong to the same language family, and the chances of the proverb having been translated and adopted into the languages are fairly high regarding the historical spread of proverbs in Europe.

When viewing the Japanese equivalent, the representation of eye is still apparent and embodied in the same way as for the European proverbs. What is different here is the lack of a concrete referral to a recipient in regard to the desire overstepping its boundaries, meaning there is no mention of a belly/stomach in this proverb. Used here instead is a referral to an embodied abstract entity with similarly understood metaphoric aspects as the concrete bodily version of a stomach.

An interesting chance for further research would be to investigate if this proverb has been adopted from its European equivalents in relation to the globalisation of the English language, or if it is an example of when proverbs have similar meanings without any evidence of having been borrowed from another language (Buchanan, 1965, p. xiv).

As previously mentioned, all metaphors are understood through a cultural filter. However, in example 6 from table 1, we can see an instance of a proverb using a cultural marker alongside its representation of eyes.

(6) Kabe ni mimi ari, shoji ni me ari.

Although the culture marker is not directly seen through the representation of the eye(s), the proverb is in its entirety culturally influenced. In Buchanan’s English translation of the meaning, the part regarding ‘paper-sliding doors’ is a big indication of the proverbs cultural belonging. Paper-sliding doors are a common thing in Japanese homes, instead of thicker wooden doors as is the norm for most homes in Western and Northern Europe. This type of cultural marker is, from what I have analysed, not evident in the Swedish and English proverbs.

In the examples, 1, 9, and 19 the metaphoric interpretations belong with the category THE EYES ARE PORTALS TO ONE’S CHARACTER due to the eye(s) being embodied as an object

through which one’s emotions and values are expressed. Regarding example 9 and 19, the Swedish and English proverbs are almost identical in wording. The Japanese example 1, however, is nowhere near similar to the Swedish and English variation of the proverb. One other notion to mention is that the Swedish and English representation of the eye(s) in terms of how the cultures view the organ metaphorically, seem to be well portrayed in the proverbs seeing as the eye(s) metaphorically represent a portal through which one express emotions. This aspect of expressing emotion through one’s eyes through a representation of a portal of some kind is not evident in the Japanese variant, as far as my analysis goes. However, in example 1, it is possible to find a Japanese variant of an expression of emotions. The Japanese employs the animal cat and allows for an understanding of how a cat’s eyes change depending on its emotions and how it feels. Instead of applying a concept of an inanimate object like a mirror or a window, the metaphorical concept of the eye has to be understood through one’s understanding of how a cat acts.

5 Concluding remarks

This study set out to examine English, Swedish, and Japanese proverbs in search of finding if there are any differences or similarities, regarding a semantic aspect, through the

representation of eye(s) in the figurative expressions. This was to be researched by using Lakoff and Johnson’s conceptual metaphor theory, the concept of embodiment and cultural knowledge in relation to understanding the metaphorical meanings in the proverbs.

I was able to find similarities in the proverbs over all three languages regarding the metaphoric interpretations. However, they are quite different in other ways. Even though eye(s) is represented in a similar metaphoric way across the proverbs, the other components

making up the proverbs are expressed through other concepts that are not always occurring in all or even two of the languages.

As seen from the Figures 1 through 3, there were similar metaphoric interpretations regarding eye(s) in the proverbs across all three languages. The one metaphoric category which was found most often, though it may be down to this study’s restricted data to a larger and more varied source from where to take example proverbs, was one of the main categories under the conceptual metaphors, being; POWER OF OBSERVATION IS IN ONE’S EYES. In this

category, an unexpected similarity was discovered regarding the eye(s) embodied through the metaphorical concept of EYES BEING PORTALS TO DESIRE.

From a cultural perspective, it is somewhat apparent in the Swedish and English

proverbs that they are related, which can be seen through the concepts and how they are being understood through similar cultural filters applied to them. This could be a likely occurrence due to the languages being related and the cultures often having come into contact with each other through history up until contemporary time.

There are some instances of similar metaphoric interpretations between the Japanese and the two western languages. However, regarding the cultural markers being represented in the proverbs I could only find it displayed in one Japanese proverb. This may be due to the restriction regarding this study’s access to more equal sources of proverbs, and could therefore be of interest for further study if a larger and more varied collection of proverbs could be accessed.

References

Apperson, G. L., & Manser, M. H. (2007). Dictionary of proverbs. Hertfordshire, Great Britain: Wordsworth Editions.

Buchanan, D. C., (1965). Japanese Proverbs and Sayings. USA: University of Oklahoma Press.

Eye, n.1., (n.d.) In Oxford English Dictionary. Retreived from

http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/67296?rskey=zEZ4Ld&result=1&isAdvanced= false#eid)

Gibbs, R. W. (2003). Embodied experience and linguistic meaning. Brain and Language, 84, 1-15.

Holm, P., (1964). Ordspråk och talesätt: med förklaringar. Stockholm: Victor Pettersons Bokindustri AB.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980a). Conceptual Metaphor in Everyday Language. The Journal of Philosophy, 77(8), 453-486. doi:10.2307/2025464

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980b). Metaphors we live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lakoff, G., & Turner, M. (1989) More than Cool Reason: A Field Guide to Poetic Metaphor. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Maalej, Z. A., & Yu, N. (Eds.). (2011). Introduction: Embodiment via Body Parts.

Embodiment via body parts: Studies from various languages and cultures. (pp.

1-20). Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing.

Mieder, W. (2014). Origin of Proverbs. In H. Hrisztova-Gotthardt & M.A. Varga (Eds.), Introduction to paremiology: A comprehensive guide to proverb studies (pp. 28-48). Warsaw: De Gruyter Open Ltd.

Moreno, A. I. (2005). An analysis of the cognitive dimension of proverbs in English and Spanish: The conceptual power of language reflecting popular believes. SKASE

Nakamura, K. (2006). Deaf in Japan: Signing and the Politics of Identity. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Norrick, N.R. (2014). Subject area, terminology, proverb definitions, proverb features. In H. Hrisztova-Gotthardt & M.A. Varga (Eds.), Introduction to paremiology: A comprehensive guide to proverb studies (pp. 7-27). Warsaw: De Gruyter Open Ltd.

Occhi, D. J. (2011). A Cultural-Linguistic Look at Japanese ‘eye’ Expressions. In Z. A. Maalej & N. Yu (Eds.), Embodiment via body parts: Studies from various languages and cultures (pp. 173-194). Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing.

Robinson, L. (2004). Beliefs, values and intercultural communication. In M. Robb, S. Barrett, C. Komaromy, & A. Rogers (Eds.), Communication, Relationships and Care: A Reader (pp. 110–120). London: Routledge.

Speake, J.( (2015). (Ed.), Oxford Dictionary of Proverbs. : Oxford University Press. Retrieved from

http://www.oxfordreference.com.proxy.mau.se/view/10.1093/acref/9780198734 901.001.0001/acref-9780198734901.

Svartvik, J., & Svartvik, R., (2004). Sagt och gjort: Engelska idiom, ordspråk, talesätt, citat. Stockholm, Norge: Norstedts Ordbok.

Tamura, K. (2003). A Comparative Study of English and Japanese Proverbs : Based on Well-known Japanese Proverbs (2) : 日英諺の比較研究. 研究紀要.27, (pp. 95-116) Widbäck, A. (2015). Ordspråk i bruk : Användning av ordspråk i dramadialog (PhD

dissertation). Institutionen för nordiska språk, Uppsala. Retrieved from

http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-262720

Yu, N. (2008). Metaphor from body and culture. In R. W. Gibbs (Ed), The Cambridge

handbook of metaphor and thought, (pp. 247-261). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press

Yu, N. (2014). Embodiment, Culture, and Language. In F. Sharifian (Ed), The Routledge Handbook of Language and Culture. Abingdon, Great Britain: Routledge.