Two-year Political Science MA programme in Global Politics and Societal Change Department of Global Political Studies

Course: Political Science Master's thesis ST631L (30 credits)

The Evolution of Chinese Higher Education

Institutions and Policies between 1990 to 2019

The far-reaching impact of internationalization as a norm

Abstract

The internationalization of Higher Education has caused a sweeping global shift of policies for governments and Higher Education institutions alike. This thesis aims to examine the case of China, and the three-decade evolution of internationalization as an influential norm, guiding the creation of comprehensive policies and plans through a multi-stage process. By examining the actors, motives and mechanisms behind Chinese Higher Education policies between 1990 and 2019, the impact of norm cascade and ultimate internationalization are revealed. The building and diffusion of internationalization as a norm includes the prioritization of global university rankings in addition to the increasing spotlight on research within the Higher Education sector. Constructivist theory was selected as the Theoretical Framework and employs concepts

including norm-building and diffusion. This qualitative case study will examine the policies and rationales for the implementation of education initiatives as encouraged by leading actors and agents and the subsequent successes and obstacles from adoption to full implementation.

Keywords: China, Content Analysis, Higher Education, Internationalization, Norms, Research Universities, University Rankings,

Table of Contents

1. Introduction 4

1.1 Purpose 5

1.2 Background on Higher Education in China 6

1.3 Relevance to Global Politics 7

1.4 Structure of the thesis 9

2. Literature Review 10

2.1 Chinese Higher Education 10

2.2 Internationalization 12 2.3 Norms 16 2.4 Summary 18 3. Theoretical Framework 19 3.1 Constructivist Theory 19 3.1.1 Defining a Norm 20

3.1.2 Norm-Building and Norm Diffusion 21

3.1.3 Internationalization vs. Globalization 23

4. Methodology 24

4.1 Research Design: Qualitative Case Study 24

4.2 Data Sources and Collection 25

4.3 Analysis of Data: Qualitative Content Analysis 27

4.4 Period of Analysis 29

4.5 Delimitations and Limitations 29

5. Analysis 30 5.1 Emergence 31 5.1.1 Emergence of Rankings 33 5.1.2 Emergence of Research 36 5.2 Cascade 37 5.2.1 Cascade of Rankings 38 5.2.2 Cascade of Research 39 5.3 Internalization 41 5.3.1 Internalization of Rankings 42

5.3.2 Internalization of Research 44 6. Closing Discussion and Future Outlook 44

1. Introduction

The globalization of Higher Education (HE) has opened the doors to the sharing of knowledge and research as well as the competition for faculty and tuition-paying students. In the wake of globalization, national governments, and Higher Education institutions (HEIs) around the world have embraced various components of internationalization to survive and thrive in a growing knowledge-based economy. While internationalization is broad in nature, it has been defined as the decisions actors make through policies and practices to “cope with the global academic environment” (Altbach and Knight 2007: 290-291). One country that has invested heavily in policies that prioritize internationalization among HEIs is China. In fact, the Chinese Ministry of Education (MoE) is responsible for “one of the largest sustained increases of investment in university research in human history” (H. Zhang et al. 2012).

The topic of internationalization of HE is of special interest to me as an international student studying at Malmö University. The ability to pursue a degree abroad, in my native tongue is proof of the hold globalization and internationalization have had on universities and academia as a whole. More recently, my involvement in HE has evolved to working in International

Admissions at Florida International University. Now more than ever, I see firsthand the pressure HEIs are under to compete nationally and internationally for talented students and professors. Additionally, the incentives behind high standings in HE rankings and research output are increasingly relevant.

In fact, internationalization has created a “market-style competition” (Mohrman 2013: 727) that has formed amongst universities and HE systems worldwide as they compete for faculty,

students, funding and even prestige. China has seen large waves of its own post-secondary population choose to pursue degrees in the United States, United Kingdom and Australia rather than remain in their home country (Choudaha and van Rest 2018). HEIs are compelled to match the behavior and accolades of its competitors by conforming to “appropriate standard[s] of behavior” (Finnemore and Skinnik 1998: 891) as dictated by norms in the HE sector. In spite of this, the spread of internationalization as a norm-building process and its acceptance and implementation pose questions for the future leaders and players in the field of HE.

As macro-based persuasion and operations encourage HE policies and implementation, the Chinese HE system becomes more globally competitive (Wang 2014; Li and Xu 2016 cited Li 2018: 31-32). Over the past three decades, from 1990 to 2019, the Chinese government has set forth aggressive goals to improve its HE standing in the world and offer distinguished

universities with opportunities to participate in cutting-edge research. Some argue this is a form of mimicry of Western education models (Hayhoe 1996 cited in Wu 2019: 83) and that

Westernization is the key to the spread of international norms, especially in HE. Regardless of the norm source, the Chinese government has not shied away from admitting the urgency “to improve [its] national power and competitiveness” (China Education and Research Network 2004) and further develop its “global competitive edge” (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China 2010).

1.1 Purpose

Previous research in the field of HE has studied the relation to internationalization including China specifically. However, research has largely been attributed to the influence of norms being dictated by “Western academic norms and values” (Rhoads et al. 2014: 177). The purpose of this thesis is to determine which actors have stood to gain from the implementation of

internationalization in Chinese HE and how that has shaped their behavior. Moreover, how said actors have attempted to assert their influence in the norm-building process, and how these norms are applied will be examined. In particular, two aspects of internationalization will be explored. The first is the growing importance of scoring high on international HEIs rankings. The second includes the spotlight on research output as a way of meeting ranking criteria.

Finnemore & Sikkink have defined norms as “a standard of appropriate behaviour for actors with a given identity” (1998: 891). As Neumann (2013) notes, some actors respond to norms without even realizing there are norms in place. On an individual or day-to-day basis, HE administrators, faculty and students may not see the direct diffusion and emergence of norms. However, three decades worth of educational policies, plans and reports demonstrate the long-term evolution of the internationalization of China’s HE system. Simply put, this thesis attempts to answer the following research question: How has internationalization influenced actor behavior in the

1.2 Background on Higher Education in China

Since the fourth century BCE, Chinese rulers and people have invested time, money and interest into education (Wu and Zha 2018: 1). This vast span of time includes a wide spectrum of changes of perspectives and policies. In modern history, one of the most significant periods for Chinese HE evolution has been the nearly thirty year span from 1990 to 2019. During this time China has embraced a more open identity and its HE sector has joined the rest of the world grappling with the impact and swift influence of globalization. The 3,000 HEIs which offer tertiary education programs and degrees with China (Wang, 2009 cited in Frezghi and Tsegay 2019: 644) have been largely guided by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the MoE in China. Furthermore, government reports show that China cites its success as the world’s second largest economy to education which has played “a pivotal role in bringing about this

unprecedented economic miracle in human history” (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, 2018a).

Since 1985, the year when China published its first landmark policy in education after the “Cultural Revolution” (CPC CC 1985), the Chinese government has demonstrated an increasing awareness of the importance of HE development and internationalization (Wu, 2018: 84). Chairman Mao Zedong along with the CCP implemented the first of a long series of ‘Five-Year Plan for National Economic and Social Development’ often referred to simply as the

‘Five-Year Plans’ (Wu, 2018: 84). The first Five-Year Plan began in the 1950’s, but it was not until the early 1990s, during the period of China’s Eighth Five-Year Plan, that the promotion of “outward-oriented” internationalization through HE took effect (ibid). For this reason, 1990 was selected as a relevant starting point for this thesis. Prior to this time period, internationalization in China largely referred to students and faculty being sent abroad rather than foreign students and faculty going to China for academic purposes (Huang 2007: 7).

Historically and culturally, China has been described as “inward-oriented” as well as micro-focused, opposed to HE competitors, like the US, that are described as “outward-oriented” and macro-focused, essentially the exact opposite (Wu and Zha 2018). However, as can be seen in China’s Five-Year Plans and landmark policies, reforms and outlines regarding education, its HE sector has steadily transformed from “inward-oriented” to more “outward-oriented” (ibid.).

Chinese nationals make up 18% of the entire world population (The World Bank 2018), and consequently nearly the same percentage of internationally mobile students in HE (Choudaha 2019). Presently, China has the largest HE system globally (Frezghi and Tsegay 2019: 644) having surged sixfold in just two decades (World Education News and Reviews, 2019). In 2000, China reported 7.4 million international and domestic students enrolled in its HEIs, and in 2018 that number had risen to 45 million (ibid.). In the past three decades, HEIs in China have evolved more than just a swell in matriculation. This transformation can be witnessed through the

policies and goals set forth of those guiding HEI policies which heavily prioritize HE rankings and research initiatives.

1.3 Relevance to Global Politics

Napoleon Bonaparte once described China as a “sleeping giant” that would one day wake and “shake the world” (Welch 2018: 513-514). It appears the same sentiment applies to China’s current and future role in HE. While Chinese HEIs have not previously dominated the HE field in the way that some Western countries have, the rigorous funding and long-term goals the Chinese government and Ministry of Education have put forth in recent decades show the persistence in becoming one of the leaders of the HE field. As the Chinese MoE has said, “[China] must press ahead with reforms to edge closer to the goal of becoming a modern

educational power” (2018a). Understanding the history of how China has evolved, in addition to the “who,” “how” and “why” behind the influence of key policies is vital to prepare for future competition of students, faculty and funds. Total global enrollment of HE students is expected to double from 212.6 million in 2015 to 332.2 million in 2030, a change of 56% (Choudaha 2019). Huge political and financial ramifications are at stake for China, and the rest of the world if China is able to dominate, or begin to share in the dominance, of educating these young minds.

Moreover, HE has more than just a transformational impact on one student; it can have a domino-like impact on entire families and communities. The post-secondary years can be an impressionable time in the life of a student, and therefore professors and HEIs, and by extension governments, have the power to shape students. Studies have revealed that HE can be identified as one type of soft power in a global context (Altbach 1998 cited in Li 2018: 6). As Joseph Nye cited in Soft Power, universities develop soft power of their own that have the capability to

reinforce foreign policy goals, and subsequently the capability to thwart said goals (2004: 17). A strong HE system that draws hundreds of thousands of international students globally can

produce graduates with an affinity for their host country. Simply put, international students can be a “valuable asset” of future leaders educated in a country they hold a “remarkable reservoir of goodwill for” (Colin Powell 2001 cited in Nye 2004). Given the connection between HE and soft power, it is no surprise that the United States and United Kingdom, which monopolize the top 100 international HE rankings (Academic Ranking of World Universities, 2019b), also lead in soft power rankings (Portland Communications and USC Center on Public Diplomacy, 2019).

The top 15 destination countries for post-secondary students, including China, educate nearly 70% of all students in HE (ibid). Moreover, China is also part of the 15 top source countries that are the home country, or source, to over 5 million, or 44%, of these students (ibid). Where students come from and where they are educated has political, cultural and economic ramifications. In 2016 alone, international mobile students generated USD $300 billion (International Consultants for Education and Fairs 2019). While Western countries like the United States, United Kingdom and Australia have been the leading educators they have knowingly or otherwise contributed to the expectations and norms surrounding HE. Were the primary leader(s) of HE to change, there would be a political and cultural shift in HE and throughout the world. This could include the emergence of a new dominant language in academia or the general practices surrounding research and teaching in general.

With the recent concentration and dedication to improving rankings and research output in Chinese HE, as will be discussed at great length in this thesis, HEIs have a large impact on society. Research prepares graduates for a “global knowledge economy” (Wang 2008 cited in Altbach and Salmi 2011: 34) and to lead governments, international businesses, NGOs and more. A global knowledge economy or knowledge-based economy hub suggests the growing

dependence of a society on “knowledge products and highly educated personnel for economic growth” (Altbach and Knight 2007: 290). H. Zhang et al. suggest a knowledge-based economy is the root of the notable increase in investments in research at the HE level (2012: 766). In HE, the measurement of knowledge is processed through metrics of publications, citations and rankings, which are prominently acquired through research at HEIs (Marginson 2017: 7). For Chinese HE,

this is uniquely compounded by the fact that HEIs and research institutions have the ability to own enterprises (H. Zhang et al. 2012: 766). Furthermore, Hazelkorn and Gibson examine the transformation from physical capital to a knowledge-based economy as a “source of wealth creation” (2017: 3). Moreover, the attainment of prestigious, world class universities can allow a country, like China, to “assert its status as a global leader” (Zhang et al. 2012: 767).

1.4 Structure of the thesis

This section briefly summarizes the structure of the thesis. The introduction chapter thus far has provided an overview of the research puzzle and question at hand. It has explained the purpose and aim of the research question in addition to a brief historical background of HE in China. Lastly, the introduction has clarified the connection this thesis shares with the larger field of Global Politics. After the introduction chapter, five additional chapters follow: the Literature Review, Theoretical Framework, Methodology, Analysis and Concluding Discussion and Further Outlook.

The Literature Review will present: HE in China, internationalization and norms. Next, the Theoretical Framework dives into norm emergence using the work of Finnemore and Sikkink as a foundation. Norm-building and diffusion is also discussed to provide more context of the various stages norms must pass through. The Theoretical Framework also examines similarities and differences between internationalization and globalization theories. The Methodology chapter discusses the choice behind a qualitative case study as the research design as well as the selection of qualitative content analysis to analyze the data. In addition, the data sources and processing of the collected documents through open coding is also examined in the Methodology section. The fifth chapter, the Analysis, examines the strengthening of internationalization as a norm through prioritization of HEI rankings and research output over the last thirty years. The breakdown of actors, as well as their motives and mechanisms in the norm-building and

diffusion process help to answer the research question. Additionally, an overview of the thesis as well as thoughts for future studies and research on this topic are shared in the final chapter, Concluding Discussion and Future Outlook.

2. Literature Review

This chapter, the Literature Review, will explore previous research conducted on three topics discussed at great length throughout this thesis. It has been divided into three sections on Chinese HE, internationalization and norms. The first section will broadly examine HE in China and its evolution over the past 30 years. Next, scholarship surrounding internationalization will discuss the effects it has on government and HEIs around the world. This section will look at

internationalization in a more broad sense, rather than internationalization within China

specifically, which will be discussed later on in the thesis. Finally, the last section explores the life-cycle, existence and emergence of norms which will be discussed ever more in the

Theoretical Framework chapter.

2.1 Chinese Higher Education

The vast majority of literature surrounding HE in China has spoken to the “huge strides” China has made “towards restructuring HE” (Zong and W. Zhang 2019: 417) as well as the growing political influence and rationale behind this modernization (Li 2018, Li 2001, Xu and Mei 2018). This has resulted in tension between adopting Western-style education while maintaining the culture and traditions of the HE sector (Wu and Zha 2018: 6). China’s growing international participation and recognition particularly took off in the early 2000s with its acceptance into the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2001 (Khan, 2004 cited in Frezghi and Tsegay 2019: 644). Similar to its motivation to join the WTO, the rationale to incorporate international education lies in its hope to strengthen its reputation globally (Kayombo and Sigalla 2015: 196). Altbach

highlights China’s significant progress despite continuing to be a “gigantic periphery” (2001 cited in Wu 2018: 82). Altbach (2001) and Yang (2013) both note that the goal of international legitimization could explain why the Chinese HE system has often relied on Western and foreign models. The influence of “Western academic norms and values” creates a paradoxical challenge for China to remain true to its own academic roots while engaging in modernization of the HE sector (Rhoads et al. 2014, Altbach 2007).

HE initiatives sanctioned by the Chinese government and MoE include Projects 985 and 211 which will be discussed in greater length in the Analysis chapter. These projects encapsulate the

large focus on strategic planning and promotion of HE internationalization (Wu 2018: 85). Both projects were aimed at advancing the mission for world-class HEIs in China (Jiang, 2012 cited in Frezghi and Tsegay 2019: 648). In addition to improving the world-class rankings of HEIs, these plans built the foundation of stronger standards of research for hundreds of Chinese HEIs. Wang refers to the 1990’s when Projects 985 and 211 period as China striving for “mutual recognition mechanism of academic qualifications” (Wang 2014: 86). Wang (2014) and Yuan Gao (2019) see this as a demonstration of the desire for Chinese HEIs to be accepted both academically and internationally. However, China, among other regions such as Latin America and Africa, has been referred to as an academic “follower” taking norm orders from “leaders” in the West (Yuan Gao, 2019: 30).

Zong and W. Zhang examined the influence of the HE policy, Project 985, through a “[q]uasi-experimental design” (2019: 420). The study cited a forthcoming second edition that would put the findings into “global, national, political and cultural contexts” (2019: 418). However, the initial study aimed at identifying the correlation of universities under the Project 985 umbrella and their subsequent research output (ibid.). A similar paper had been previously published by H. Zhang, Pattonb and Kenney in which the impact of the projects were analyzed more deeply (2012). However, this research did not look into the actors and their mechanisms for

implementing new policies and HE goals in the first place.

Mohrman’s work adopted a methodology in which over twenty research-intensive universities were used as the unit of analysis (2013: 729). She examined total university expenditures and percentage of cited publications and found that despite an influx of funding and autonomy for HEIs in China, the amount of resources may not coincide with HE ambitions (2013: 737). Despite this, government documentation such as education reports and outlines were not referenced and the methodology leaned more quantitatively. Based on the data processed, Mohrman did conclude that China’s leading HEIs are following suit and valuing international rankings, much like American and European HE systems (ibid.).

Huang compared the internationalization of Chinese HE to that of Japan in a comparative case study. This comparison looked into international student enrollment and recruitment specifically,

and how it played a role in overall international collaboration. Huang concluded that HE has not been intrinsically changed due to internationalization, citing that neither country is a “[centre] of learning” (2007: 13). This seemed to be an outlier compared to other findings regarding Chinese HE. On the other hand, Yang and de Wit acknowledge the challenges HEIs in China are up against in student and faculty recruitment, relating to low English levels, lack of scholarship opportunities and difficulty finding a job after graduation (2019: 20).

Wang’s research outlines the most influential documents and educational policies that testify to the changing discourse in HE in China which includes the Outline for Reform and Development of Education in China, Action Plan for Revitalization of Education in the Twenty-First Century, 2003–2007 Action Plan for Revitalization of Education among others (2014: 11). Wang does not, however, examine any of the Five-Year Plans like Xu and Mei (2018) do. The Five-Year Plans which provide an overview of previous and future achievements, strategies and issues within the national educational system (Xu and Mei 2018: 100). Xu and Mei offer a more robost analysis of education as a whole, in addition to specific chapters on development in HE.

2.2 Internationalization

In order to understand the rationale for the three-decade evolution of HE policies in China, it is important to explain the concept and extent of internationalization and the pressure it has over actors and HE systems. Internationalization has impacted not only Chinese HE, but that of HE systems globally. For this reason, internationalization will be explored as a whole in a more general sense. Internationalization is an intricate phenomena with numerous so-called “strands” (Scott 2006: 14 cited in de Wit 2011: 243). This thesis relies on the following definition of internationalization: internationalization is “the policies and practices undertaken by academic systems and institutions—and even individuals—to cope with the global academic environment” (Altbach and Knight 2007: 290). Internationalization includes versatile policy processes that overcome the traditional borders between national education systems (Luijten-Lub et al. 2005). It has also been said that internationalization is a response to globalization (Altbach et al. 2009: 4 cited in Dagen et al. 2019).

The terms of internationalization and globalization are very similar, and at times can appear intertwined. However, despite sharing much in common, they are unique in how and at what stage they influence a university and/or national government, in the case of HE. Altbach et al. describe globalization as the global changes in which the emergence of technology, language and knowledge have shaped the world, whereas internationalization is the response to globalization via various university and government policies (2009, 7). Globalization has been described as an external process (Dagen et al. 2019: 651) that is not only supranational but fosters “market-style competition” between countries (Mohrman 2013: 727). Simply put, while internationalization is directly impacting the HE sector, globalization is directly impacting the process of

internationalization (Knight 2003 cited in Huang 2007: 3).

Liu and Yan (2015) consider that without globalization taking hold of China beginning in 1978, after the Cultural Revolution, China would not be in a position to embrace internationalization years later. In fact, some literature including that of Liu and Yan goes as far as to deem China as the “biggest winner” in globalization. Other literature views globalization as unalterable and inescapable whether as a victim or agent (Yuan Gao 2019). It is unclear whether this implies that Yuan Gao believes China would have been greatly impacted regardless of its political

circumstances. This thesis assumes the majority standpoint that globalization was essential in serving as a springboard for internationalization, and will focus on the policies and practices of HEIs which fall under the tangible impact of the internationalization umbrella.

Altbach and Knight cite globalization’s impact and force as inherently “unalterable” (2007: 290) and are aided by various forces pushing internationalization to the forefront of HE conversations and policies. Kayombo and Sigalla (2015) and Altbach (2010) suggest globalization as a

“catalyst” for internationalization, and in turn, Frezghi and Tsegay (2019) view

internationalization as the catalyst for the development of Chinese HE. Luijten-Lub suggests that while globalization may be an external force, nowadays actors at various levels of the HE

spectrum are actively involved in internationalizing campuses of HEIs (2007: 11). While external forces may play an important role, they are not capable of eclipsing the effort required on the local level.

Many HEIs and governments have identified the ways in which embracing and spearheading internationalization initiatives can benefit, and even be a source of profit. By leaning into the catalyst of globalization, internationalization can have strong economic incentives (Altbach et al. 2009, Dagen et al. 2019, Knight 1997 in Wang 2014). As globalization “tends to concentrate wealth, knowledge, and power in those already possessing these elements” (Altbach and Knight 2007: 291) there is an inherent advantage for certain actors. Van der Wende saw

internationalization’s intent as “systematic” and “sustained” (1997: 19) to meet growing

economic and labor demands through policies and practices implementation. Understanding the economic and political ramifications of internationalization can shine light on the rationale of implementing certain policies.

The literature also spoke to the emergence of the knowledge-based economy, sometimes called a knowledge society or hub, which are underlying financial incentives to embrace

internationalization (Li 2018, de Wit 2011, and Altbach and Knight 2007). The knowledge economy is just one result of diversified actors within HE. Additional factors include increased student mobility with ease of crossing borders to new funding sources, such as government scholarships. As Salmi and Altbach (2011) make clear, gaining entry into the knowledge economy of internationalization can be fast-tracked through prosperous research universities. Maringe and Foskett suggest brain drain as one consequence of actors turning away from internationalization. Brain drain refers to the loss of highly educated and skilled individuals to employment opportunities elsewhere (Emeagwali 2003 cited in Maringe and Foskett 2010: 3). For followers who do not adequately adapt to norms like internationalization, this has an adverse effect. However, the leaders of internationalization, and consequently the knowledge economy, see the increase of brain gain, in which highly educated graduates contribute to the workforce and economy of another country, typically where they have pursued their post-secondary degree. The knowledge economy discussed is just one of what Altbach and Knight (2007) refer to as “commercial advantages” of internationalization.

The actual processes of building, diffusion and framing of norms within the internationalization of HE, will be discussed later in this chapter. Certain assigned values and beliefs have

inequality in the source and manner in which norms are spread (Yuan Gao 2019). This inequality is seen particularly between the West and East and North and South. For instance, while Western nations fill the role of “leader,” countries like China and others in Asia, Africa and Latin

America fall within a subsequent “follower” position (ibid.: 30). Additionally, Slaughter and Leslie discuss academic capitalism's impact in which typically English-speaking nations have an advantage in restructuring HE in a way that matches their own values and policies (1997: 54 cited in Li 2018: 28).

An example of unequal perpetuation of internationalization restructuring is the use of English “as the lingua franca” in academia, research, publishing and instruction of degrees and courses

(Altbach and Knight 2007, Rhoads et al. 2014, Welch 2018, Maringe and Foskett 2010). Consequently Western states, particularly the United States and United Kingdom, are able to maintain their linguistic dominance which forces “follower” countries such as China to follow suit by adapting to internationalization efforts such as prioritizing the use of English in research. The focus to English has a domino effect, directly impacting the rankings and research of a HEI, consequently linked to student enrollment, faculty hiring which can in turn alter reputation and funding (Wang 2014 10-11). Welch explains how HEIs in China specifically face a dilemma of perishing locally or globally depending on how serious they take the maintenance and growth of English-language programs and research (2018: 524). By publishing in the local language, HEIs are overlooking the collaboration, feedback and acknowledgement with other HE systems. However, by publishing in English to appease global standards, research that is particularly relevant locally or regionally is not accessible by the local community, and thus real recommendations and changes are hindered.

To Wang, the internationalization of HE is a “game” in which countries are forced to play by arbitrary rules (2014: 10-11). The prominence of the English language reinforces Yuan Gao’s (2019) assertion of “followers” forced into abiding by game rules set by HE “leaders.” Research has shown that acceptance of publications for authors who are not native or fluent English

speakers are at a prominent disadvantage (Altbach and Salmi 2018: 45). Yang and de Wit (2019) note the increase in China’s offering of English-taught classes and programs. In 2009, only 34 universities in the entire country offered courses in English, and just 8 years later, that number

had nearly tripled to more than 100 universities (2019: 19). This trend is a concerted effort to attract more international students to pursue a post-secondary education in China (Rhoads 2014: 18).

2.3 Norms

Finnemore and Sikkink define a norm as “a standard of appropriate behaviour for actors with a given identity” (1998: 891). In the case of this thesis, given identities include that of national governments as well as universities and university leaders and administrators, specifically in China. Universities can implement policies that abide by and disregard norms; however, governments, especially authoritarian ones, have the power to issue sweeping legislations that universities must follow in order to maintain funding. Nearly every author and researcher studied in this thesis mentioned norms, and the impact norms have on HE in general, and HE in China. Nonetheless, the details as to what these norms specifically were, entailed, or how they were built were lacking. Although, there was one commonality shared by authors discussing norms in HEIs in China. The limited descriptions of norms nearly all cited the origin of the norm’s influence; the West.

Finnemore and Sikkink offer a fundamental question, “how do we know a norm when we see one?” (1998: 892). While norms can be vague in nature, some evidence of norms may include an actor’s “prompt justification for action” (ibid.). Finnemore and Sikkink go on to explain that without a norm there would be no need to explain or justify actions and changes. Therefore, if norms dictate appropriate behavior in addition to shared ideas and expectations (ibid. 894) then a quantitative ranking of best to worst universities in HE theoretically solidifies who is, and more importantly, is not following international norms placed on the HE sector. Furthermore, if a behavior or action were not a norm then it would not warrant a justification and the same idea applies to pushback that can occur during norm emergence. Were the new norm not challenging or replacing an old norm, then there would be no discussion or discomfort felt by actors.

Following this logic, digging into policies that cause a reaction of reluctance can also help pinpoint the implementation of norms in HE.

The degree to which norms have significantly influenced Chinese HEIs vary. Some authors cite China’s balance to remain faithful to traditions (Welch 2018: 523-524) while others describe China as “being constrained by Western-dominated international rules” (Liu and Yan 2015: 2,016). Rhoads et al. (2014) warn of China adopting policies and practices of Western

counterparts in order to gain acceptance legitimacy only to find they have inadvertently formed a dependency culture as well as reinforced “the American-dominated hegemony” (Mok 2007: 438 cited in Rhoads et al. 2014: 123). Moreover, Yuan Gao (2019) notes that at times

internationalization and ‘Westernization’ are confused for having the same meaning, showing just how much of an unbalanced scale exists. Even during the phase of norm cascade, as part of the norm “life-cycle” (Finnemore and Sikkink 1998) highlights the motive for the desire to belong to an international community in addition to legitimize oneself to Western counterparts (Tamtik and Kirss 2016: 172).

Acharya makes the case that the origin of norms does matter because it indicates which and whose ideas matter (2004: 239). It has been suggested that international norms are more quickly received and implemented from one country to another in which cultural and political contexts are complementary (Checkel 2001 cited in Tamtik and Kirss 2016: 167). However, Acharya explains that norms are often adjusted and reconstructed to match with local beliefs and are deconstructed to select elements that are most favorable (2004: 251). The example of China recognizing the international importance of global rankings but reimagining to better fit the strengths of its own HEIs is seen with the development of the Academic Rankings of World Universities (ARWU). The ARWU is a Chinese-created ranking system that ranks Chinese and international HEIs. This concept of embracing parts, or a variation of international normative ideas is called “framing” (Payne 2001: 39). Payne (2001) argues this is a crucial element to norm persuasion which coincides with Finnemore and Sikkink’s (1998) first stage of the norm life-cycle.

Moreover, through Projects 211 and 985, China demonstrates the flexibility of the

internationalization of Chinese HEIs. These projects sought to put Chinese HEIs on the map as high-ranking, research-based elite universities. Winston references the observations of Wiener (2008) regarding the stable and flexible side or sides of norms (2018: 642). Winston notes that

norms that are stable are accepted at face value meanwhile flexible norms are changed intentionally or otherwise. Therefore, norms that are stable and flexible in nature may retain stability in certain circumstances and may appear flexible to certain actors and agents (ibid. 643). That same dual nature can be seen in the HEIs surrounding Project 211 and 985. The actions of the MoE demonstrate the desire to see these implementations widespread throughout the HE system, however due to limited oversight or funding, or whatever the case may be, this is not the case. Instead, certain HEIs were selected and saw a more stable version of the norm and its requirements, than a HEI without explicit direction or resources to prioritize would.

2.4 Summary

This Literature Review demonstrates the wealth of literature in existence regarding HE in China, internationalization and norms. However, while many works explored the internationalization of Chinese HEIs, I was unable to find any instances in which the role of norms were explored deeply. Instead they were merely referenced as Western ways of academia that had infiltrated the Chinese education system. The only exception was an article written by Tamtik and Kirss (2016) regarding the norm-building process of internationalization in Estonia. In this work, the authors explored the step-by-step process of the building and diffusion of norms and which actors were involved at each stage and why and how they influenced this process. Nevertheless, I could find no such work that took a similar approach to China in which the norm process was analyzed from start to finish throughout a specific period of time, which is why I decided to make that the centerpiece of this thesis.

This thesis looks at how internationalization can be more deeply understood through a step by step examination of the actors and motivations involved, and how modernization on a mass scale can take place because of a powerful norm. Instead of just looking simply at the end result of how well a particular internationalization initiative succeeded, I was able to examine how and why an initiative began and how it was carried on by other agents before ultimately examining its overall impact and acceptance. Therefore, this thesis will add a unique lens to existing literature and offers a framework which can be referenced in future examinations of additional norms within the HE sector in China, and other countries.

3. Theoretical Framework

The Literature Review portion includes various concepts that are broad in nature. For this reason, this section, the Theoretical Framework, will outline the central theory relied on in this thesis, constructivist theory. Since constructivism is a vast theory, I have chosen a few concepts to employ, specifically norms and the building and diffusion of norms. This will serve as a background for the Analysis which will be split into three sections to represent each step in the norm-building and diffusion process. In addition, the similarities and differences between the concepts of internationalization and globalization will also be analyzed. As previously touched on, globalization has a fundamental role in internationalization, particularly in the case of HE. Globalization has helped to hasten the development and sharing of norms. Having a fundamental understanding of a norm and how it comes about as well as becoming widely accepted is

necessary to pinpoint internationalization of HE in terms of constructivist theory.

3.1 Constructivist Theory

Constructivist theory asserts that “social phenomena and their meanings are continually being accomplished by social actors” (Bryman 2012: 710). It also is defined as reality being actively and socially constructed (Halperin and Heath 2012: 425). This thesis is concerned with the behavior of actors in accordance with widespread norms such as internationalization and therefore fits into the constructivist theory. These norms shape priorities and processes on

various levels and are constructed and spread by entrepreneurs and actors who stand to gain from implementation. While certain actors might stand to gain, oftentimes, there is a “legitimate social purpose” (Payne 2001: 37) constructivism sees embedded within a norm. Constructivists have a particular interest in the political actors and their rationales for aiding norms from the emergence stage through its development (Payne 2001: 38). Winston suggests that social constructivists identify the fundamental functions of norms as actively determining the identities and interests of actors (2017: 640). Therefore, if the norm life-cycle is strengthened through the evolution of actor behavior, then constructivist scholars would see that as social phenomena being directly transformed through the actions and persuasion of actors.

3.1.1 Defining a Norm

There are multiple definitions of a norm, however, this thesis relies on the definition put forth by Finnemore and Sikkink. Their definition defines norms as “appropriate behavior...for actors with a given identity” (1998: 891). Meanwhile, Checkel describes norms as “shared understandings that make behavioral claims” (1999: 88 cited in Winston 2018: 639). Similarly, Conte et al. understand norms as “structural constraints of individual behavior” (2013: 2). However, there is not always a simple way in determining a norm and its role in affecting the political landscape without looking at the big picture and multiple layers of context. Norms that are highly

internalized are often taken for granted as they are so embedded in society and its expectations (Finnemore and Sikkink 1998). This is why identifying agents who are ostracized for breaking the rules can just as easily demonstrate what norm they are indeed ignoring or rejecting (ibid. 892). A similar manner of determining a norm is searching for behaviors that agents feel the need to explain or defend. Were that behavior an accepted norm there would not be a reason to speak of it, as Finnemore and Sikkink suggest.

Agents, or norm entrepreneurs, have the ability to more easily and efficiently spearhead norms when they are wealthy and powerful (Altbach and Knight 2007: 291). One such example of this concentration can be seen in the unequal spread and profiting of globalization (ibid.). This results in other, less developed countries following the lead of others. In HE, nations and institutions that are “outward-oriented” are typically in the position to spread their norms to the rest of the world where “inward-oriented” are pushed into a position to adopt said norms (Wu 2019: 81). Moreover, international norms are more easily processed and accepted with the existence of a “cultural match” in terms of administrative and legal agents and agencies (Checkel 2001 cited in Acharya 2004). However, this can be aided by flexible norms through processes of framing and localization at the local level which will be discussed in the next section.

One manner in which actors can more easily persuade of a norm’s worth is through the

ramifications of choosing whether or not to comply. Dominant norms are difficult to ignore or completely reject when the consequences are measurable. For instance, if students and professors flock to largely English speaking HEIs that prioritize research, institutions that differ may suffer

in sustaining admission enrollment and securing funding (Goastellec 2008: 78). However, just because a norm is dominant does not mean it can or will be copied to the same degree. The stability and flexibility of norms also plays a role in the manner in which a norm is adopted (Wiener 2008 cited in Winston 2018) if it ever fully reaches the internalization stage at all.

3.1.2 Norm-Building and Norm Diffusion

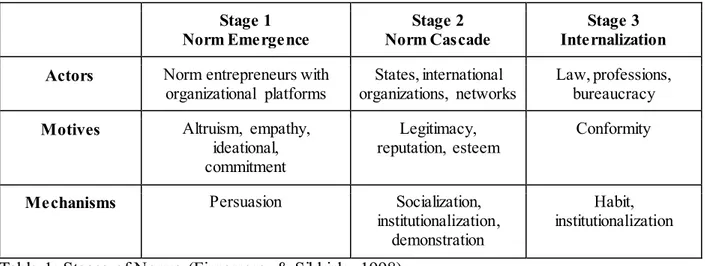

A norm does not gain acceptance nor is it implemented overnight. In fact, there is a three-step “life-cycle” that norms typically complete (Finnemore and Sikkink 1998). Finnemore and Sikkink describe a process of international norm-building by distinguishing among three distinct phases of this cycle: norm emergence, norm cascade, and norm internalization (1998: 895). The process of building a norm demonstrates the “specific standards and values [that] are promoted and incorporated into society” (Tamtik and Kirss 2016: 178). The step-by-step breakdown for the norm-building process in China’s HE system can be seen in Table 1 below.

Stage 1

Norm Emergence Norm Cascade Stage 2 Internalization Stage 3 Actors Norm entrepreneurs with

organizational platforms organizations, networks States, international Law, professions, bureaucracy

Motives Altruism, empathy,

ideational, commitment

Legitimacy,

reputation, esteem Conformity

Mechanisms Persuasion Socialization,

institutionalization, demonstration

Habit, institutionalization Table 1: Stages of Norms (Finnemore & Sikkink, 1998)

As seen in Table 1, Finnemore and Sikkink (1998) have created a table to outline the actors, motives and mechanisms behind each stage of the norm life-cycle. During the first stage, norm entrepreneurs, or agents, attempt to convince others to embrace and value the importance of a certain belief or practice. Next, during the cascade phase, a norm may experience pushback or criticism which then must be combated in order to prove successful. Responses to pushback can include the desire to conform to the most prominent norms to fit in in addition to the desire to be seen as legitimate in the eyes of the international community. According to Elgström (2000),

reluctance is a natural component of the cascade stage and allows the strongest norms and defense of entrepreneurs and actors in order to fully emerge successfully. Finally, the norms that survive long past the “tipping point” (ibid. 892), which develop after the first stage, are so accepted that their origin or reason for existence is no longer questioned. Once reaching the final stage of internalization, norms are seen as second nature.

Norm-building can focus on international macro-perspective, including “outward-oriented” as previously mentioned (Tamtik and Kirss 2016: 166). Norms can also focus on the flexibility of how international norms are adopted and modified domestically (ibid.). Regardless if in a domestic or international context, a norm must pass through each of these stages. However, it is important to note that international norms that are internalized and implemented locally or regionally may vary from the original norm (Risse-Kappen 1995 cited in Finnemore and Sikkink 1998: 893). These variances have been referred to as norm framing or localization. Payne

suggests that the most successful norms that make it to the internalization phase are framed in ways that will resonate with a different community (2001: 39).

Winston indicates that some scholars such as Antje Wiener and Jeffrey T. Checkel believe that if norms diffuse, actors will know how to act accordingly (2017: 643). Norm diffusion presumes the traveling of norms from their original state and context to a norm receiver (Winston 2017: 645). One way a norm can resonate is by promising high esteem and prestige once the norm is adopted and implemented (Acharya 2004: 245). This requires norm entrepreneurs to have a quality understanding of the goals of another agent in order to see successful norm diffusion take place (Nadelmann 1990: 482). Norm localization is similar to norm framing in its active

construction of “foreign ideas by local actors” (Acharya 2004: 245). This ultimately results in the development of harmony between foreign norms and local practices (ibid.).

A norm cluster, as outlined by Winston, is a response to an international norm but has “looser and less determinate” aspects that may not perfectly align with the original norm (2017: 647). The foundation of what is deemed appropriate is taken and adapted to better align with local politics or culture. Norm clusters are adopted through a series of discourse between pertinent actors. Therefore states who adopt and implement norm clusters aim to strike a balance between

acceptable behavior expected by the international community and that of the local community (ibid.). Understanding norm clusters is necessary to see the big picture of the far-reaching impact of a norm, particularly as that norm may differ in its local delivery and implementation.

3.1.3 Internationalization vs. Globalization

Internationalization and globalization often appear as two sides of the same coin. It is true that they are fundamentally similar and in literature are sometimes regarded as practically

indistinguishable or even interchangeable. However, internationalization and globalization are unique, particularly in their timeline of emergence. In fact, internationalization is often referred to as the response to globalization which is consequently adopted by HEIs in order to survive and thrive (Maringe and Foskett 2010: 1). This response arises in order to meet the demand and needs of society and the economy (Van der Wende 1997: 19 cited in Dagen et al. 2019: 647).

Altbach et al. (2009) explain how globalization is often shaped by an interconnected economy via technology and the growing role technology plays. While virtually no country has been left untouched by the impact of globalization, China has especially evolved under globalization’s wake. Globalization can be presumed to blur “borders and national systems” to such a degree that disappearance is made possible (Teichler, 2004: 7 cited in Dagen et al. 2019: 649). Putting HE aside, China has seen skyrocketing GDP growth over the past three decades (Liu and Yan 2015: 2,004). This “comprehensive transformation” (ibid.) has served as a foundation for China to turn its attention and invest in competitive HE goals and policies. Thus, the reality of China, much like other nations is “shaped by an increasingly integrated world economy” (Altbach et al. 2009: 7) which must compete for talented faculty and students as well as tuition fees.

Both globalization and internationalization allow for the brisk and widespread norms within the HE sector. The origin of said norms, more often than not, flow from the “leaders in international education” including the West (Yuan Gao 2019: 30). The internationalization of competition for mobile students and faculty through global rankings forces “followers” (ibid.) like China and other East Asian nations to look to the norms of the leaders and follow suit. By avoiding embracing internationalization, HEIs and governments are not able to “cope with the global academic environment” (Altbach and Knight 2007: 290) or at least not as easily.

Internationalization can take place on various levels from HE systems and institutions to individuals (ibid.). In the case of Chinese HE, internationalization most noticeably came in the form of sweeping, top-down educational policies (Li 2018).

4. Methodology

This chapter will go into detail regarding the research design for why a qualitative case study has been selected for this thesis, in addition to the qualitative content analysis of the data. As there are multiple manners of approaching a case study, the rationale for selecting this specific research design will be touched on. In addition to explaining the motivation for selecting a case study, the considerations for selecting China as the sole case in this thesis will also be examined. Lastly, the data source and collection and use of open coding utilized within the content analysis will also be explored in the data sources and collection portion of the Methodology chapter.

4.1 Research Design: Qualitative Case Study

Yin and Campbell (2018) write that case studies are intended for research questions that ask “how?” or “why?” while focusing on contemporary events. To Yin and Campbell, contemporary events surpass the present and are instead more fluid in including both past and present events. Case studies do not require control over behavior, unlike experimental research questions. Yin and Campbell go on to say that case studies require an extensive deep-dive into “complex social phenomena”' (2018: 33). The empirical methods of the case study allows a researcher to look at a case within the “contextual conditions” applicable to the case (Yin & Davis, 2007 cited in Yin and Campbell 2018: 45). Halperin and Heath (2012) suggest that case studies are comparative even if only one case is involved, such as in the example of this thesis. They explain that the most successful case studies contribute to other academic debates in the field and can serve as a relevant basis to other contexts (ibid. 205). Moreover, case studies provide a platform to see how relatable a particular theory is when removed from one context and applied to another.

Case studies can be categorized as theory-confirming or theory-infirming (Lijphart 1971 cited in Halperin and Heath 2012: 207). Theory-confirming case studies demonstrate a wider

applicability to the original theory and therefore adds empirical support. Conversely, theory-infirming case studies poke holes in the original theory, although it does not fully reject the

original theory either. This thesis is theory-confirming as it relies on existing literature to build the case study, however, it offers a deeper investigation into the norms and subsequent life-cycles. By examining not only the existence but the specifics of norms in HE the groundwork is there to be applied to unique contexts later on.

While China is the sole case studied within this work, similar principles can be applied to other HE “followers” and even the opposite end of the spectrum, HE “leaders.” If the foundations of internationalization and norm-building in HE were taken from the context of China and examined instead to that of India or the United States, then local HE policies would reveal a unique story. When first conducting research about internationalization of HE as well as the multi-prong impact of international students, it became apparent that post-secondary Chinese students make up the majority of the global international student population (UNESCO, n.d.). This made me wonder why Chinese students were uninterested in pursuing a degree in their home country and if the government and HEIs have or would attempt to change anything. Knowing that HE is a huge economic sector with political and cultural ramifications I began to research if and how China has attempted to remedy the situation. When it became clear from the Literature Review that comprehensive policies were already fully in effect it seemed necessary to focus in soley on China.

4.2 Data Sources and Collection

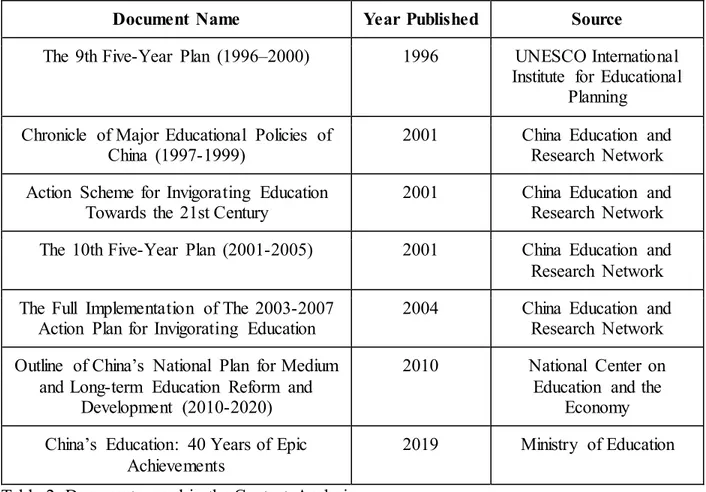

This thesis relies largely on policy and official documentation originating from the Chinese government and MoE to complete the content analysis. Multiple initiatives, action plans, educational reforms, and chronicles of milestones were examined to see the change of policies over the years (see Table 2 below). These documents were used to determine the creation and diffusion of the life-cycle of norms, and the actors, motives, and mechanisms behind said norms. Open coding was used while reading through the documents to identify predominant themes. Babbie explains content analysis as an inherently coding operation (2001: 309 cited in

Kohlbacher 2006). Babbies goes on to explain the ability coding has to transform “raw data into a standardized form” (ibid.).

Many of the documents searched included information regarding other Chinese education initiatives related to elementary school performance, teacher salaries and national literacy rates that were not relevant to the scope or aim of my thesis. For this reason, coding was necessary to sift through documents quickly and efficiently. The coding was performed through the use of the “find” command on the computer and I began coding by searching for keywords including

international, internationalization, Higher Education, and university. From there, the focus on

rankings, research and even the use of English in academia continued to repeatedly appear throughout the documents. Finally, specific policies related to the internationalization of China’s HE through initiatives such as Project 211 and 985 became evident and could be further

explored. The documents in Table 2 were coded and used in the content analysis.

Document Name Year Published Source

The 9th Five-Year Plan (1996–2000) 1996 UNESCO International Institute for Educational

Planning Chronicle of Major Educational Policies of

China (1997-1999) 2001 China Education and Research Network Action Scheme for Invigorating Education

Towards the 21st Century 2001 China Education and Research Network The 10th Five-Year Plan (2001-2005) 2001 China Education and

Research Network The Full Implementation of The 2003-2007

Action Plan for Invigorating Education 2004 China Education and Research Network Outline of China’s National Plan for Medium

and Long-term Education Reform and Development (2010-2020)

2010 National Center on Education and the

Economy China’s Education: 40 Years of Epic

Achievements 2019 Ministry of Education

Table 2: Documents used in the Content Analysis

All of the documents listed in Table 2 were published by the MoE in China. That being said, as will be explored later on in the Delimitations and Limitations section, the MoE did not have each document available on its English website. Fortunately, English translations were available from

other reputable sources. One of these sources was the China Education and Research Network (CERNET) is a research network created by Tsinghua University in China (OER World Map, n.d.). CERNET is funded by the Chinese government and directly overseen by the MoE in China (ibid). Another source was the policies published on the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization International Institute for Educational Planning (IIEP- UNESCO) website were also used. Finally, the National Center on Education and the Economy (NCEE), a non-profit that has a branch dedicated to international education benchmarking which conducts research “on the most successful education systems” (The National Center on Education and the Economy, n.d.) served as a source and provided the 2010-2020 National Development Plan.

Additional documents were downloaded from the MoE’s homepage in addition to the Chinese Education Research Network. China’s University and College Admission System website, an online portal for Chineses universities in which international students can learn more about HEIs in China and apply, was also consulted for specifics regarding Project 211 and 985. Lastly, the government-sanctioned Academic Rankings of World Universities (ARWU) was also relied on to view the evolution of Chinese HEIs global standings between 2003 and 2019 and the ARWU methodology.

4.3 Analysis of Data: Qualitative Content Analysis

Qualitative content analysis has been selected as the manner in which the data is analyzed throughout this thesis. Content analysis is a way of researching that systematically analyzes textual information while remaining “unobtrusive” (Halperin and Heath 2012: 318). It has been defined as a manner in which to make “replicable and valid inferences from texts to the contexts of their use” (Krippendorff 2004:18). Through the aid of open coding, as previously mentioned, content analysis can identify “specified characteristics of messages” (Holsti 1969: 14 cited in Bryman 2012: 289) and elicit general themes.

Furthermore, a qualitative content analysis may be inductive or deductive in nature (Elo and Kyngäs 2008: 108). An inductive analysis takes specific data to see how it fits into a larger

sentiment or circumstance (ibid.) Additionally, an inductive approach moves from the specific to the general, so that particular instances are observed and then combined into a larger whole or

general statement (Chinn & Kramer 1999 cited in Elo and Kyngäs 2008: 109). Meanwhile, a deductive approach is based on an earlier theory or model and therefore it moves from the general to the specific (Burns & Grove 2005 cited in Elo and Kyngäs 2008: 108). Both inductive and deductive approaches have similar preparation phases. This thesis takes an inductive

approach.

Content analysis allows the author to make inferences from the literature’s data which can produce new insights given a larger context (Krippendorff 1980 cited in Elo and Kyngäs 2008: 108). When policies, like those surrounding HE in China, are released, they are intended to be practical sources of information. Those policies, and their authors, are not focusing on the larger scheme of external actors and forces impacting said policies. Moreover, content analysis has the flexibility to analyze research quantitatively or qualitatively. A quantitative content analysis revolves around manifest content, which is a more visual manner of acquiring data, asking “How often?” or “How many?” (Halperin and Heath 2012: 318). A qualitative content analysis

examines latent or underlying content. Additionally, a qualitative content analysis searches for the “meanings, motives, and purposes embedded within the text...to infer valid hidden or underlying meanings” (Weber 1990: 72-6 cited in Halperin and Heath 2012: 318).

To begin the qualitative content analysis used throughout this thesis, I began reading through the history and policies of Chinese HEIs particularly in terms of the relationship and response to the internationalization of HE. What became abundantly clear through this research is that the last three decades (1990-2019) have transformed and evolved Chinese HEIs to a great extent.

Because norm life-cycles and internationalization are processes that take time, a thirty year span is a snapshot of what responses have emerged. For this reason, the content analysis of the Analysis chapter is broken into three subsections, to represent each step of Finnemore and Skikkink’s norm life-cycle: norm emergence, cascade and internalization. Moreover, the emphasis on rankings and research was repeated not only in literature discussing

internationalization of HE on the whole, but also in articles analyzing China’s internationalization specifically.

The first section of the analysis looks at the emergence of internationalization in the 1990s. The actors, or norm entrepreneurs, are examined in addition to their motives. The mechanisms used to implement the top-down approach are also discussed. Supporting documentation from the MoE reports and outlines are consulted to provide quotes and context provided by the

government. The creation of Project 211 and 985 underscore efforts of internationalization and the growing importances of global norms in HE. The following subsection, norm cascade, portrays the continued impact of internationalization and the acceptance and consequent implementation of norms at a lower level, taking a bottom-up approach. The last subsection, internalization, shows how this continuous process has played a role in the HE landscape in China, particularly with obstacles to habits and behaviors forming around internationalization as a norm.

4.4 Period of Analysis

The internationalization of HEIs in China first became evident in a MoE document from the early 1990’s called the Outline for Reform and Development of Education in China (Li 2018: 77). For this reason the time period of this thesis begins in 1990. Moreover, two prominent initiatives, Project 211 and 985, released in 1985 and 1998 respectively, have been pivotal to the speed and degree of internationalization in Chinese HE. In the 2010s both projects were

highlighted for having aided the success of HE in China, but were ultimately replaced. The various series of progress and initiatives put forth during this timeframe paint a picture of how actors and norms have evolved over time. In order to fully understand the impact of

internationalization as a norm, it is necessary to choose a time frame that shows changes in policies and attitudes over a substantial period of time. For this reason, the thesis looks at policies and events up to the end of 2019.

4.5 Delimitations and Limitations

This thesis examines HEIs in China; however, private Chinese universities are not included. Only public universities will be examined due to the fact that the policies and projects selected are applicable to goals and expectations of public HEIs only. Moreover, researching China can be ambiguous as it can include Hong Kong, Taiwan and Macao in addition to mainland China. For the purposes of this thesis references to China solely represent mainland China. This

decision was made in consideration of the time constraints in addition to the fact that Hong Kong, Taiwan and Macao each have independent Ministries of Education.

Throughout the researching and writing of this thesis, two limitations have been revealed. These limitations include: 1) linguistic constraints for the researcher and 2) policies and statistics confined by the Chinese government. To clarify the first limitation, I do not speak Mandarin. Consequently I was unable to read documents and policies in their original form which impacted the collection of data. This was apparent in times where translated reports were difficult to find, or in some cases, non-existent or were inaccessible from broken website links. To overcome this I decided to analyze educational outlines and reports released by the Chinese MoE in addition to several Five Year-Plan documents to have sufficient content and to support the analysis with additional findings.

Second, many of the English-translated websites were in fact in Mandarin, and policies and reports were not consistently accompanied by translations. When looking for statistics regarding international students and general tertiary education enrollment in databases such as UNESCO Institute for Statistics to the Institute of International Education there were large gaps of data. Even the Chinese Ministry of Education’s website did not have consistent annual data or an archive to see information from five years prior, much less decades ago. As this thesis uses qualitative measures, these statistics were not crucial to my analysis; however it was an obstacle at times.

5. Analysis

Through the use of qualitative content analysis, chapter 5, the Analysis, will aim to answer the following research question: How has internationalization influenced actor behavior in the

building and diffusion of norms in Higher Education in China between 1990 and 2019? This

chapter is divided into three sections that coincide with the norm life-cycle as defined by Finnemore and Sikkink in the Theoretical Framework chapter. The Analysis chapter will examine the actors, motives and mechanisms applied at each stage of the norm-building and diffusion process. Each section will specifically look at two of the most prominent elements of the norm-building process of internationalization in Chinese HE. This includes the focus on not

only maintaining, but striving to improve the international rankings of HEIs in China through criteria put forth by organizations such as the ARWU. Moreover, the most prevalent criteria of rankings is based on research output and collaboration. Internationalization has greatly shaped HE research through pressures including the language in which scholars publish research. Both rankings and research demonstrate how internationalization has increased the

“interconnectedness between national education systems” (Luijten-Lub et al. 2005: 149-150) and implores actors to examine priorities and targets of the HE sector.

Without a clear-cut list of what norms exist in HE or in the internationalization of HE, Finnemore and Sikkink offer a more basic question “how do we know a norm when we see one?” (1998: 892). As outlined in chapter 3, the Theoretical Framework, determining the existence of norms requires identifying three key steps of the process. The first, being the actors or “norm entrepreneurs” (ibid. 893) who push for the norms to be embraced. Secondly, the motives for seeing the norm put in place and the mechanisms required in doing so. This must be repeated at each level of the norm life-cycle, beginning with the emergence stage. The analysis will identify the push for ranking and research as embedded in the internationalization norm-building process that have emerged in the last 30 years. Moreover the varying degrees of successful implementations and acceptance will be explored.

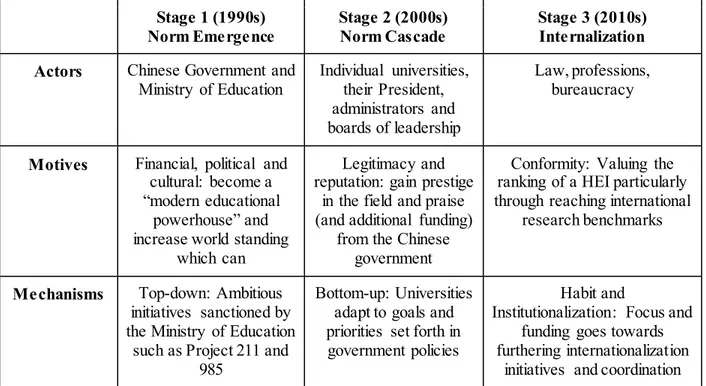

Section 5.1 offers an overview of norm emergence through policies in China, particularly during the 1990s. The rationales for the Chinese government and MoE as norm entrepreneurs to invest in spreading a norm such as internationalization will also be analyzed (see table 2). Next, in section 5.2, the cascade of norms from the entrepreneur to other agents, including individual HEIs in China and how motivations and mechanisms of the norm diffusion differs from the initial stage. Finally, section 5.3 looks at the concluding step in the norm life-cycle process, internalization, as well as the obstacles faced in reaching this phase.

5.1 Emergence

Internationalization first became a cornerstone of HE policies in China beginning in the 1990s which brought forth meaningful policies and plans instrumental in opening up Chinese HEIs to the rest of the world. The 1990s in China have been referred to as a period of “global openness”