Browse Offline, Buy

Online?

BACHELOR DEGREE PROJECT THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Marketing Management & Civilekonom AUTHORS: Malin Christensson, John Synnes, & Julia Blomberg TUTOR: Jenny Balkow

JÖNKÖPING May 2020

Exploring how showrooming is affected by customer

experience in the clothing industry

i

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge and express our deepest gratitude to the ones who have contributed and supported the development of this thesis. Without them, this research would not have been possible.

First of all, we would like to thank our brilliant tutor Jenny Balkow for always inspecting our thesis with a critical eye through each stage of the process. Her extensive knowledge and experience within the field has provided us with valuable feedback and insights during this time. By the same token, we would like to thank our peers from our seminar group for their fruitful input.

Secondly, we would like to pay our special regards to the interviewees for their time and participation in this study. Their stories and insights have given us a wonderful opportunity to gain useful knowledge on the subject.

Thirdly, we would like to acknowledge Anders Melander for providing us with the key guidelines needed for this thesis adventure.

Lastly, we would like to thank the founder of Zoom Video Communications for allowing us to communicate effectively during tough times of social distancing as a result of the outbreak of COVID-19.

______________ ______________ ______________

ii

Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Browse Offline, Buy Online? Exploring how showrooming is affected by customer experience in the clothing industry

Authors: Malin Christensson, John Synnes, & Julia Blomberg

Tutor: Jenny Balkow

Date: 2020-05-18

Key terms: Showrooming; Customer Experience; In-store Experience; Decision-making

Abstract

Background: In the last 20 years, the retail industry has experienced a drastic transformation

and the rise of e-commerce has resulted in a change in the retail business models. Thus, there has been a shift from the traditional single-channel format to a multi-channel format. A critical challenge that retailers face with the multichannel format is the concept of showrooming, where consumers visit the brick-and-mortar retailer to explore the assortment and thus utilise the services offered, but finally purchases the product online.

Problem: Brick-and-mortar retailers often consider showrooming as a threat regarding the act of free-riding which might lead to a loss of potential customers. However, opinions on how to conquer this undesirable behaviour vary. Previous research shares the underlying assumption that price is the critical driver for the consumers’ decision to perform showrooming. Although, there is no clear consensus on how to hinder this behaviour.

Purpose: The purpose of this study is to make sense of how customers’ in-store experiences

affect showrooming in the clothing and footwear industry. The findings of this study are expected to contribute to beneficial theoretical retail knowledge as it investigates the underexplored research phenomenon of showrooming in a broad customer in-store experience context.

Method: To perform this research, a qualitative research design was applied and 15

semi-structured interviews with self-proclaimed showroomers were conducted.

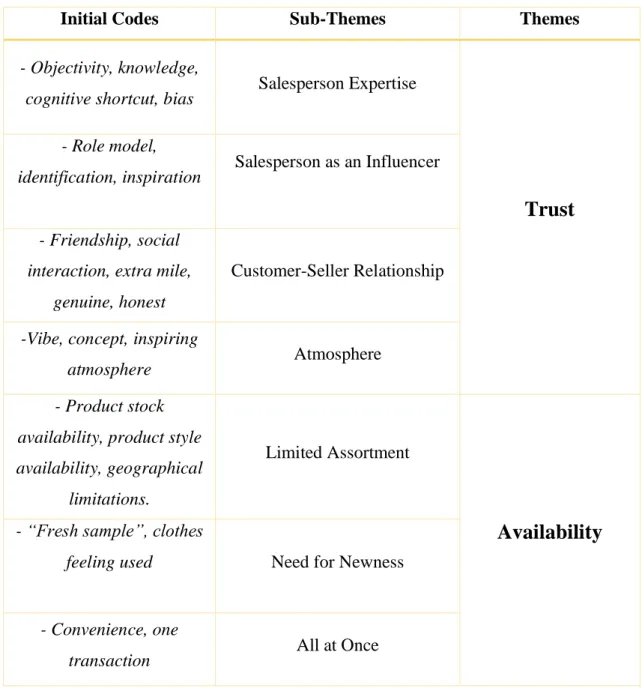

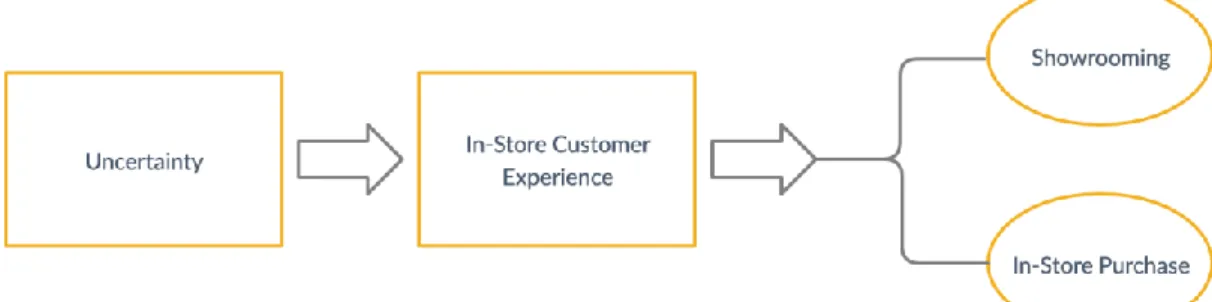

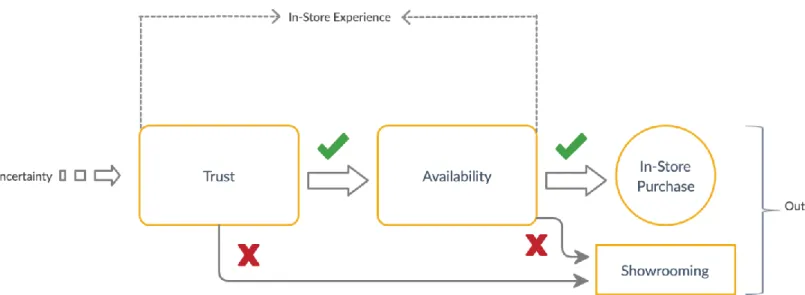

Results: The findings declare that for a positive in-store experience to occur, it must be permeated by trust. When trust is achieved, the second critical factor of in-store experience in the context of showrooming concerns the availability. If these two factors of in-store experience are successfully managed, the desire to engage in showrooming decreases. These findings are visually demonstrated in a developed framework on page 49.

iii

Table of Contents

1. Introduction... 1

1.1 Background ... 1 1.2 Problem Discussion ... 3 1.3 Research Purpose ... 4 1.4 Research Question ... 4 1.5 Delimitations ... 42. Theoretical Framework... 6

2.1 Method Adopted for the Theoretical Framework... 6

2.2 Customer Experience ... 7

2.2.1 Conceptualisation of Customer Experience ... 7

2.2.2 Components of Customer Experience ... 8

2.2.2.1 Cognitive Experience ... 9

2.2.2.2 Affective Experience ... 9

2.2.2.3 Social Experience ... 9

2.2.2.4 Sensory experience ... 10

2.2.3 Determinants of Customer Experience... 10

2.2.3.1 Technology as an additional determinant in the 21st Century ... 11

2.2.3.1.1 Using technology in an omni-channel context………..12

2.3 Consumer Decision Making ... 13

2.4 Showrooming ... 15

2.4.1 Factors Suggested to Influence Showrooming Activity ... 16

2.4.1.1 Price ……….. ... 16

2.4.1.2 Salespersons Tactics ... 17

2.5 Theoretical Summary ... 18

3. Methodology and Method ... 19

3.1 Methodology ... 19 3.1.1 Research Paradigm ... 19 3.1.2 Research Approach... 20 3.1.3 Research Design ... 20 3.2 Method... 21 3.2.1 Primary Data... 21 3.2.2 Sampling Approach ... 21 3.2.3 Semi-Structured Interviews ... 22 3.2.4 Interview Questions ... 24 3.2.5 Data Analysis ... 26 3.2.6 Selection of Quotes ... 27 3.3 Ethics ... 27

3.3.1 Anonymity and Confidentiality ... 27

3.3.2 Credibility ... 28

3.3.3 Transferability ... 29

3.3.4 Dependability ... 30

3.3.5 Confirmability ... 30

4. Findings & Analysis ... 31

4.1 Conducting the Findings & Analysis ... 31

4.2 Why Visit B&M Stores: Uncertainty Avoidance ... 32

4.3 Customer In-Store Experience: Trust ... 34

iv

4.3.2 Salesperson as an Influencer ... 36

4.3.3 Customer-Seller Relationship... 37

4.3.4 Atmosphere ... 40

4.3.5 Showrooming Outcome: Trust ... 42

4.4 Customer In-Store Experience: Availability ... 43

4.4.1 Limited Assortment ... 43

4.4.2 Need for Newness ... 45

4.4.3 All at Once... 46

4.4.4 Showrooming Outcome: Availability ... 47

5. Conclusion ... 48

6. Discussion ... 50

6.1 Theoretical Contributions ... 50 6.2 Practical Implications ... 50 6.3 Limitations... 51 6.4 Future Research ... 52References ... 53

Appendices... 60

Appendix 1: Interview Protocol ... 60

1

1. Introduction

This chapter starts with a background of showrooming and an elaboration of its emergence. It follows by a problem discussion, leading to the purpose and research question of the study. Lastly, the delimitations are addressed.

1.1 Background

In the last 20 years, the retail industry has experienced a drastic transformation. Historically, retail consumption took place solely in physical stores, thus, customers made their purchases from a single channel which were based on face-to-face personal transactions (Kim, Ferrin, & Rao, 2008). However, the rise of e-commerce and the digital transformation have resulted in a change in the retail business models (Verhoef, Kannan, & Inman, 2015). Thus, in today’s digitalised society, traditional brick-and-mortar (henceforth, B&M) retailers have expanded to a variety of platforms, and e-commerce has become an essential part of many businesses. With 4,18 billion users, US $2,237,959 billion in revenue (2020), and an expected annual growth rate of 7,6% between 2020-2024 worldwide (Statista, n.d.), there is no doubt that the e-commerce industry will continue to flourish. However, there is a lower growth rate among B&M retailers, which indicates that e-commerce cannibalised on the business of B&M retailers, resulting in a decline in sales and a negative impact on the bottom line (Agnihotri, 2015). Consequently, there has been a progression from the traditional single-channel format to a multi-channel format and many B&M retailers have adapted both an online and offline existence (Agnihotri, 2015) in order to stay competitive in the contemporary retail environment.

In recent years, there has been an evolution of the multichannel concept where omnichannel is the final step. The term omnichannel may be described as a customer-centred form of retailing which allows for shopping across channels and interaction with the brand at all times, providing customers with a complete and seamless shopping experience (Melero, Sesé Oliván, & Verhoef, 2016). In contrast to multichannel, which implies divisions between physical and virtual stores, the omnichannel concept provides a comprehensive experience that merges online and offline channels (Verhoef et al., 2015). The new touchpoints that enable

2

omnichannel experiences to be provided, such as mobile phones, social media, and smartwatches, create a unified connection to the brand regardless of what channel the consumer utilises (Verhoef et al., 2015). In turn, this contributes to a further change in consumer habits and shopping behaviour, which transforms the consumer buying process (Juaneda-Ayensa, Mosquera, & Murillo, 2016) since buyers are now constantly and simultaneously evaluating channel choices. This may increase the convenience for consumers but might instead bring complex challenges for retailers (Ailawadi & Farris, 2017).

One of the most critical challenges retailers are facing with multichannel and omnichannel retailing is the concept of showrooming, a phenomenon where consumers visit the B&M retailer to explore the assortment and thus utilise the services offered, but finally purchases the product online, usually from a competitor to a lower price (Kuksov & Liao, 2018). This has become a frequent shopping behaviour among consumers, and it has thus become a popular concept to discuss in modern society (Gensler, Neslin, & Verhoef, 2017). In a showrooming penetration study, it has been indicated that 50% of Swedish online shoppers had utilised showrooming in 2018 (Statista, 2019). If the showrooming activity appears in the context of the same business both online and offline, it does not remain a critical issue for the B&M retailer in terms of profit. However, industry reports indicate that consumers usually turn to a competing online store at the point of purchase, which is commonly referred to competitive showrooming (Gensler et al., 2017). This will be the focus of this study and henceforth referred to as showrooming solely. The showrooming activity is especially predominant in high involvement product categories such as clothing and electronics, that consumers purchase less frequently and associate with a higher risk in contrast to low involvement goods (Eriksson, Rosenbröijer, & Fagerstrøm, 2018).

As the multi- and omnichannel concepts as well as showrooming activities add complexities to the clothing industry, retailers face several challenges and barriers to conquer. Historically, B&M retailers in the clothing industry have had challenges building efficient e-commerce platforms due to the importance of the touch-and-feel in-store experience. However, as a result of new information technologies, consumers now have the possibility to purchase items online with an interactive approach, which results in a more satisfactory online shopping experience (Blázquez, 2014). Additionally, consumers commonly use their smartphones and other technical devices for support in the decision-making of clothes (Eriksson et al., 2018) leading to constant consumer connectedness and empowerment (Chou, Shen, Chiu, & Chou, 2016).

3

Consequently, the online clothing industry is experiencing rapid growth. In the United Kingdom, it is the most rapidly growing online industry (Blázquez, 2014), and in Sweden, the online clothing industry had a turnover of 13 billion SEK (approximately 1.3 billion USD) in 2019 (PostNord, 2019) and is expected to continue to grow. Thus, B&M clothing stores might have to find new ways for value creation to stay competitive in contemporary business climate.

1.2 Problem Discussion

B&M retailers often consider showrooming as a threat regarding the act of free-riding and consumers’ exploiting traits in research activities. In other words, consumers benefit from B&M retailers to do their own research and identify their best-fit product before ultimately buying it from another online retailer at a lower price (Kokho Sit, Hoang, & Inversini, 2018). Consequently, B&M retailers might lose potential customers, which can result in detrimental effects on the profits in the long run (Mehra, Kumar, & Raju, 2017). Accordingly, the concept of showrooming is often perceived as negative shopping behaviour from a retailer’s point of view (Daunt & Harris, 2017). Nevertheless, opinions on how to cope with this undesirable behaviour significantly vary.

Previous research shares the underlying assumption that price is the critical driver for the consumers’ decision to perform showrooming (Gensler et al., 2017). Although, as the above paragraph indicates, there is no clear consensus on the measures that should be taken to best hinder such behaviour. More specifically, two distinct camps within showrooming research have been identified. The first camp argues that B&M stores simply are required to match their prices with online retailers, as a result from that showrooming derives from consumers’ desire to find cheaper prices (Gensler et al., 2017). The second camp, however, suggests that it is more than just price. Here, researchers argue that salesperson services work as the main determinant influencing consumers’ desire to engage in showrooming (Bäckström & Johansson, 2017; Ogruk, Anderson, & Nacass, 2018).

In sum, existing research suggest that either price or service are the most predominant factors influencing showrooming behaviour, as these can increase satisfaction enough for consumers to complete their purchase in-store. However, to stay competitive in today’s digitalised and integrated omnichannel society, numerous scholars stress the importance of the concept of

4

customer experience, as it is argued to be the new battleground (McCall, 2015). Customer experience has therefore become an essential objective for many businesses (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). Today, scholars even call it the fundamental basis for marketing management (Becker & Jaakkola, 2020). Nevertheless, despite its significant importance among scholars, few studies take this one step further, beyond price and service, and connect a broad view of customer experience with its potential impact on showrooming.

1.3 Research Purpose

The purpose of this study is to investigate and make sense of how customers’ in-store experiences affect showrooming in the clothing and footwear industry (henceforth solely referred to as the clothing industry for simplicity). Thus, the study will be of exploratory nature, add to the already existing body of literature, and fill the gap of knowledge. The topic was chosen due to its relevance in contemporary society as well as the researchers’ great personal interest within the field.

The findings of this study are expected to contribute to beneficial theoretical retail knowledge as it investigates the research phenomenon of showrooming in the underexplored context of a customer in-store experience. Consequently, it might also contribute to managerial implications for B&M clothing retailers on how they can enhance the customer in-store experience with the objective of retaining the customer to the point of purchase and thus, stay competitive in a society where e-commerce is flourishing.

1.4 Research Question

How does customer in-store experience affect showrooming in the clothing industry?

1.5 Delimitations

This research concerns four main delimitations. Firstly, the research is based on a customer perspective and involves a sample consisting of Swedish young adults. The sample is also delimited to students living in Jönköping, a relatively small city in Sweden, who studies at

5

Jönköping University. This sample was chosen based on the population criteria of price-conscious, self-proclaimed young adult showroomers, in addition to practical reasons for the researchers living in Sweden. Secondly, this study is delimited to the clothing and footwear industry, as a result of that the industry is selling product categories with high involvement which thus is applicable and relevant to the showrooming phenomenon. Thirdly, this study only investigates the effect and perceptions of the in-store experience of customers. Thus, other parts of the experience associated with showrooming, such as online experience, were intentionally left out to be able to narrow and define the scope of the research.

Lastly, this research was conducted during spring 2020, where there was an ongoing outbreak of the novel corona virus COVID-19. Thus, the society was highly characterised by this pandemic that affected the majority of the different angles of the society. As a consequence, this brought several delimitations to the study which further will be discussed and addressed throughout the research. However, this delimitation mainly affected the data collection but did not cause severe consequences on the study overall.

6

2. Theoretical Framework

This chapter begins with a presentation of the method adopted for the theoretical framework. Further, a comprehensive elaboration of customer experience is provided. With this foundation, the development and complexity of consumer decision making is examined. These concepts are linked to the emergence of the showrooming phenomenon, which is the final concept of investigation in this chapter.

2.1 Method Adopted for the Theoretical Framework

For the theoretical framework to be relevant, distinct, and as grounded as possible, a systematic approach has been adopted in the literature review process. As a result, deep and valuable insights about the subject of customer experience, consumer decision making, and the showrooming phenomenon have been developed.

The procedure followed is characterised by three stages: identification of the scope, establishment of key literature, and analysis of the literature. To be able to get a thorough understanding of the literature, the main databases used were Google Scholar, Primo, Scopus and, the Jönköping University Library. In the search process, the keywords used included the terms Customer Experience, In-store Experience, Decision Making, and Showrooming which allowed the researchers to gain a deep understanding of the previous research within the field. Furthermore, the process included a systematic screening of the abstracts and summaries of the articles to facilitate the establishment of relevance to the purpose. To ensure the quality of the relevant articles, only peer-reviewed journals were used. In addition, to the greatest extent possible, only articles ranked in the ABS-list or the SSCI index were included. The time frame of the articles regarding showrooming was mainly limited to five years to ensure relevance, as this is a relatively new phenomenon. However, several older articles were used as a result of a high impact and great contribution within the field of research in the areas of customer experience and decision making. Examples of such included the work of Engel, Kollat, and Blackwell (1968), Holbrook and Hirschman (1982), and Thompson, Locander, and Pollio (1989).

7

2.2 Customer Experience

The make-or-break for retailers’ survival in a fierce competition is about the creation of long-lasting competitive advantages (Gentile, Spiller, & Noci, 2007). Coming out as the winner of the battle of the customer thus seems to be the key to survival. As traditional differentials such as price, features, and quality are argued to lose its ability to differentiate, customer experience has for many businesses become the last point of differentiation (Shaw & Ivens, 2002).

Customer experience may be defined as the set of interactions between the customer and the experience provider and the co-creation between the two (Bustamante & Rubio, 2017). Its evaluation is dependent on the comparison between (1) the expectations of the customer, (2) the stimuli interactions and (3) the quality provided from different moments or touchpoints in the store environment (Gentile et al., 2007). This definition serves as a basis for the conceptualisation of customer experience in the following paragraphs. Nevertheless, as a result of the countless potential touchpoints with customers, various researchers have examined that retailers nowadays have less control of the customer experience and the customer journey (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). Studying the customer experience dimension might therefore be important for value creation.

“The customer experience will be the next business tsunami.” - Shaw & Ivens (2002)

In this section, the concept of customer experience will be broken down into four parts. First, a conceptualisation of customer experience. Second, the components of customer experience. Third, the determinants of customer experience. Lastly, the influence of technology in perceived customer experience in an omnichannel context.

2.2.1 Conceptualisation of Customer Experience

Customer experience is argued to be a key concept in the field of business. There has been a vast increase in studies about the topic, yet many definitions exist which have led to theoretical confusion of the phenomena (Becker & Jaakkola, 2020). In the 1950s, researchers argued that people desire enjoyable experiences, and not the product itself (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). This notion was further studied by experiential theorists in the 1980s such as Holbrook and

8

Hirschman (1982) and Thompson et al. (1989). Holbrook and Hirschman (1982) pointed out the importance of the experiential view. This included emotional aspects of decision-making and experience, where the experiential perspective was described as consumption which involves a steady flow of consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Thompson et. al (1989) further embraced the experiential view of experience called existential phenomenology, which provided a philosophical base to explore customer experience.

Customer experience started to gain significant attention in marketing research and practice when Pine and Gilmore (1998) introduced the spark of a new era, “The Experience Economy”. Meaning, customers are not only searching for high-quality products and services, but also satisfying shopping experiences. In the 1990s, customer experience was defined as a reflection of offerings managed by retailers (Pine, 1999). Schmitt (1999) further broaden the definition and suggests a multidimensional view, involving the cognitive (think), affective (feel), physical (act), social identity (relate), and sensory (sense) responses consumers have related to the retailer. In other words, specific stimuli trigger specific experiences. More recent research has continued to emphasize this holistic view towards customer experience (e.g. Bolton, Gustafsson, McColl-Kennedy, Sirianni, & Tse, 2014; Verhoef et al., 2009). However, some researchers have a broader definition and describe experience as emerging in customers worlds (Chandler & Lusch, 2015), whereas others view a narrower scope in a specific context, such as retail settings (Verhoef et al., 2009). In this study, the researchers comply with the major view of customer experience as multidimensional in a retail context.

2.2.2 Components of Customer Experience

As the paragraph above indicates, this study complies with the construction of customer experience as holistic and multidimensional in nature in a retail context. Bustamante and Rubio (2017) present an updated structure from the abovementioned findings of Schmitt (1999). The former encapsulates in-store experience into four experiential components: cognitive, affective, social and sensory responses, as they take the internal responses to service stimuli in physical store settings into a holistic experience. Although, what is important to highlight is that customers barely recognise this composition. Rather, the goal is to make customers perceive each experience as a complex but unitary feeling, where the components are hardly

9

distinguishable from one another (Gentile et al., 2007). The following sections elaborate theoretical definitions of each type of experience examined in this study.

2.2.2.1 Cognitive Experience

The cognitive component refers to state of processing information that is gained from perceptions, acquired knowledge and subjective characteristics. This component requires a customer’s creative thinking as it is involved when interacting with, for example, products and services, self-service technologies and the servicescape. By doing so, specific stimuli awaken customer thinking and therefore creates a complete cognitive experience (Bustamante & Rubio, 2017).

2.2.2.2 Affective Experience

The affective system can be composed of two blocks with different levels of intensity: mood (low intensity) and emotion (high intensity). In this study, the latter will gain more focus than the former, since emotions are usually associated with a stimulus object and thus are more intense (Bustamante & Rubio, 2017; Erevelles, 1998). Therefore, a customer interaction in-store that generates emotional experience can generate an affective relationship with the retailer and its products (Gentile et al., 2007). The hedonic and utilitarian needs might bring customers to the store, but generating emotions is the most significant reason for stay and shop (Sachdeva & Goel, 2015). Emotional attributes can thus be the critical value that encourage the customer to stay to the point of purchase.

2.2.2.3 Social Experience

Social experience can be a characteristic in a store environment that can be described as the relational component (Gentile et al., 2007), which appears in social contexts (in this case B&M stores) where experience is co-created by socialising and interacting with other people. The relationships that emerge in a retail context is based on the quality and intensity of the interaction between the customer-employee and customer-customer engagement. This interaction can range from giving opinions and receiving advice (Bustamante & Rubio, 2017). Consequently, customers can develop emotional ties and establish a social relationship with salespeople and other shoppers, inducing a sense of belonging.

10 2.2.2.4 Sensory experience

A sensory experience is created when an offering in a physical store stimulate senses, for example sight, sound, touch, taste and smell. In a retail store environment, sensory stimuli can also arouse aesthetical pleasure, excitement, satisfaction, and sense of beauty (Gentile et al., 2007). Various studies support the assumption that sensory responses are inseparable from physical responses and can thus be associated with physical well-being, for example energy, vitality, or comfort/discomfort (Bitner, 1992).

2.2.3 Determinants of Customer Experience

To be able to understand the concept of customer experience, besides the four aforementioned experiential components, it is also important to recognise the determinants of a perceived customer experience. An extensive study by Jain and Bagdare (2009) suggest six affective dimensions that help crafting a complete experience in retail settings, providing a solid ground for stimuli interaction among customers. All of which were found to include emotional and hedonic dimensions as they would contribute shaping retail experience.

• Store Atmospherics – design and ambience factors represent this dimension, such as the combinations of music, fragrances, arrangements, themes, and store design. Further, these environmental factors interact with human sensory receptors and activates cognitive, affective, physiological, and behavioural responses. As a result, the sensory stimuli can increase perceived store environment, enhance shopper experience, and eventually change the nature of behaviour.

• Customer Service – shoppers expect basic services, such as salespeople sharing knowledge of a product and to be available at any time. A well-designed customer-oriented system in a store can enhance comfort and satisfaction among customers, where the salespeople, and their expertise, skill, and attitude, is a crucial factor in providing superior experiences to the customers.

• Visualscape – an effective use of point of purchase material as well as visual simplicity, transparency, and appearance can draw attention of customers. This induces the shopper to conveniently browse and move around the store without any help from salespeople.

11

• Customer Delight – shopping can be a source of relaxation and pleasure for many people, which can include entertaining, engaging and surprising elements. Thus, it is suggested that in-store entertainment coupled with delightful surprises can generate emotional values to the customer experience.

• Merchandise – this dimension describes the importance of the product factor in retailing. Providing availability to a wide assortment of products is suggested to be essential, as it could be crucial for meeting the expectations of shoppers. This also includes the retailer’s ability to manage inventory levels and out-of-stock solutions. • Convenience – if a sequence of activities is combined in the right way, it might increase

the convenience for the customer and can be a strong determinant for the customer experience. For example, the convenience factor can include the location of the store, convenient parking, and also value-added services such as food or snacks bar.

Although, this study reflects the customer expectations from another decade, and it does not take the rise of new technologies and the changing consumer behaviours into account. More specifically, recent research has indicated that advancements in technology might shape new determinants of customer experience, and therefore, imply new means of facing showrooming. This will be further discussed in the following section.

2.2.3.1 Technology as an additional determinant in the 21st Century

The countless potential customer touchpoints and the lack of ability to control the experience have forced retailers to integrate new business functions, such as information technology (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). Verhoef et al. (2009) argue that technology-based services in B&M environments may be critical to examine in terms of its impact on customer experience. Even though the growth of digital shopping of clothes is increasing, many consumers still visit physical clothing stores regularly (Siregar & Kent, 2019). The increased rate of mobile shopping has induced consumers to use their mobile device while they are in-store, indicating an opportunity, and even a necessity for retailers to integrate interactive technology to the physical store (Siregar & Kent, 2019) in order to connect with the customer from the point of entry to the point of exit.

12

Previous literature has studied how implementation of new in-store technologies can improve customer experience (Blázquez, 2014; Harba, 2019; Kim & Yang, 2018; Lee & Leonas, 2018; Parise, Guinan, & Kafka, 2016; Piotrowicz & Cuthbertson, 2014), customer satisfaction (Meuter, Ostrom, Roundtree, & Bitner, 2000) and purchase intention (Mosquera, Olarte-Pascual, Ayensa, & Murillo, 2018) with the aim to meet the expectations of superior customer experience. One example of these suggestions for improved customer experience that has gained a lot of attention is self-service technologies (SSTs).

Kim and Yang (2018) study the incorporation of SST as a way to increase the engagement with the customers and their experience in clothing retail stores. The term refers to “technological interfaces that enable customers to produce service independent of direct service employee involvement” (Meuter et al., 2000), where SST is part of the transformation going from human-to-human interaction to technology-human-to-human service encounters. Findings show that there is a positive relationship between interactivity with SSTs and increased emotional experience, especially within pleasure and dominance attributes (Kim & Yang, 2018). Another study points out that the will to adopt SSTs has become more apparent among younger consumers than among older generations (e.g. baby boomers) (Lee & Lyu, 2016). On the other hand, Rese, Schlee, and Baier (2019) imply that Generation Y (people born between 1981 and 1996) generally values service improvements (e.g. salesperson friendliness and competence) higher than technology improvements. The authors also found that individuals in Generation Y were not only technically advanced, but also were found to use technology for emotional value.

2.2.3.1.1 Using technology in an omni-channel context

In the early years, some experts predicted that B&M stores would be outrivalled by online stores. In retrospect, the two channels have integrated, and it has caused a drastic change in consumers shopping behaviour (Marmol & Fernandez, 2019). Research suggest that the role of in-store technology in an omnichannel environment is key for the creation of an integrated shopping experience between online and offline channels, generating a seamless, engaging and memorable experience (Mosquera et al., 2018). Thus, omni-channel has become the new normal and facilitates the emerge of showrooming which has become a key issue in the retailing environment, as this type of omni-channel shopping is regarded as a threat to many B&M retailers (Viejo-Fernández, Sanzo-Pérez, & Vázquez-Casielles, 2020).

13

To summarise customer experience, it is evident that it has become increasingly difficult to understand, especially due to the abovementioned technological developments. More specifically, as customers today can interact with many different retailers through countless touchpoints both online and offline, firms have much less control of the overall customer experience (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016). For this reason, it becomes crucial to understand how consumers behave and make decisions in order to stay competitive and deliver superior experiences. This will be examined in the following section.

2.3 Consumer Decision Making

One of the core concepts in consumer behaviour theory is to make sense of how consumers’ decision-making processes affects the ultimate purchase decision (Goworek & McGoldrick, 2015), which thus is important to acknowledge when investigating showrooming. To understand consumer decision making, several models have been developed. A model that has gained significant attention is the Engel–Kollat–Blackwell (EKB) model of consumer decision making (Ewerhard, Sisovsky, & Johansson, 2019), developed by Engel et al. (1968) (see Figure 1). The model suggests a linear way of consumer decision making by dividing it into five phases: Problem Recognition, Information Search, Evaluation of Alternatives, Purchase, and Post-Purchase Activities (Ewerhard et al., 2019). As a result of the schematic portrayal of the different phases the consumer goes through, the model suits best for high-involvement products (Wolny & Charoensuksai, 2014), such as clothing. This is a consequence of the comprehensive information search that is required for high involvement products in contrast to low involvement products (Bauer, Sauer, & Becker, 2006). Furthermore, the model suggests that individual characteristics influence the different phases (Kang, 2019).

As a consequence of the characteristics of showrooming, this behaviour is anticipated to arise and take place in the three middle stages in the model. More specifically, the reasons driving the potential showroomer to the B&M store (Information Search), what is happening in the store (Evaluation of Alternatives), and the outcomes of the visit, either showrooming or in-store purchase (Purchase).

14

Figure 1: Engel–Kollat–Blackwell (EKB) Model (Engel et al., 1968)

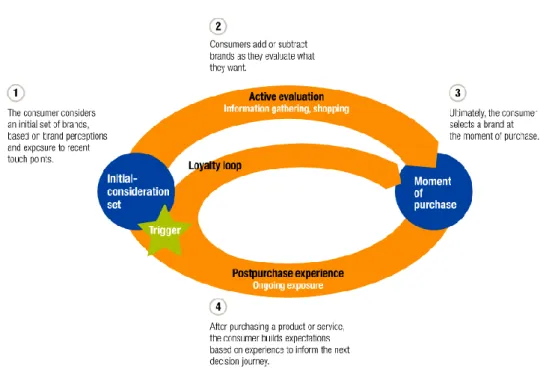

However, as a result of that consumers now can interact with businesses through numerous touchpoints throughout multiple channels, the consumer journey becomes more complex (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016), which ultimately has implications on the consumer decision-making. As the consumer in today’s internet-based society can gather information not only from the retailer itself but also from other consumers, the retailer to some extent loses control of the customer and their purchasing behaviour (Ewerhard et al., 2019). Consequently, some suggest that there has been a shift from the traditional linear models towards models that are more dynamic (Ewerhard et al., 2019). Court, Elzinga, Mulder, and Vetvik (2009) suggest a circular journey of consumer decision making (see Figure 2) including four phases: 1) Initial Consideration, 2) Evaluation, 3) Purchase, and 4) the Activities after Purchase. This model is an attempt to develop a more nuanced and complex view than traditional models (Court et al., 2009).

15

Additionally, modern models of consumer decision making frequently include the influence of social media, internet, and new technologies (Vázquez et al., 2014). This indicate that consumers nowadays can rely on their own digital research and may at any time seamlessly go back and forth between different stages of the decision journey (Ewerhard et al., 2019). Nevertheless, despite this, Ashman, Solomon, and Wolny (2015) claim that linear models such as the EKB model still contribute to valuable insights in terms of consumer decision making, as the consumer needs have not changed, but rather the tools consumers use to satisfy them. However, the model might have to be adapted to the current society. According to Wolny and Charoensuksai (2014) the stages in the decision-making process might occur several times or sometimes be left out. This imply that the EKB model, with some adaption to contemporary society, still contribute with relevant insights regarding the consumer decision making in the context of showrooming. Furthermore, several researchers (e.g. Brynjolfsson, Hu, & Rahman, 2013; Lemon & Verhoef, 2016; Rapp, Baker, Bachrach, Ogilvie, & Beitelspacher, 2015) agree that as a result of the loosened control of the customer experience in even more complex consumer decision making processes, behaviours such as showrooming are emerging. For that reason, shedding light to this phenomenon is pivotal.

2.4 Showrooming

In early days, before showrooming was a term of research, this type of behaviour was frequently described as “free-riding”. The so-called “free-riders” are consumers involved in more than a single channel within a single transaction. More specifically, they take advantage of one retailer’s services and “place their business with another” (van Baal & Dach, 2005).

Recent studies have taken this free-riding behaviour into an established research concept and introduced new interpretations. Daunt and Harris (2017) refer to showrooming as a form of multichannel shopping where consumers, by intention, benefit from information search through visiting one channel before ultimately purchasing the merchandise on another channel. It can also be seen from a perspective where the lines between offline and online channels are blurred. According to Gensler et al. (2017), showrooming is defined as the activity of collecting information offline but later purchase the product online. In addition, there is a need for the consumer to touch and feel the product (Basak, Basu, Avittathur, & Sikdar, 2017), which can be supported by the fact that showrooming is reported to be most frequent in products that

16

involves complex specifications and varied prices, such as consumer appliances (Kokho Sit et al., 2017). Also, the extent to which offline information is performed depends on whether products are high-involvement product categories, which need to be experienced physically (seen, touched, and tried on) as they might be difficult to evaluate online (Blázquez, 2014).

What is important to distinguish is that previous research has studied showrooming from two perspectives. First, it can be seen from a positive point of view, where customers can be inclined to switch channels, but not retailer (van Baal & Dach, 2005). In this context, showrooming is not critical from a retailer’s perspective in terms of profit. This kind of behaviour shows trust and loyalty towards a retailer during the channel changing process and can accordingly be characterised as loyal showrooming (Rejón-Guardia & Luna-Neverez, 2017). Second, it can be seen from a negative standpoint, which also covers the majority of showrooming research (Schneider & Zielke, 2020). These studies assume that customers change the retailer after collecting information from the B&M store. As a result, the B&M store miss out on potential customers and revenues (Mehra et al., 2017). This negative connotation, where customers both switch offline to online, and from one retailer to another, is therefore often defined as competitive showrooming (Gensler et al., 2017). The clear problematisation derived from competitive showrooming will therefore, as previously mentioned, be the emphasis of investigation for this study.

2.4.1 Factors Suggested to Influence Showrooming Activity 2.4.1.1 Price

When analysing previous literature, researchers work under the assumption that price is the critical driver of consumers’ showrooming activity. There are models that have been developed to examine the impact of showrooming competition amongst multiple channels (Balakrishnan, Sundaresan, & Zhang, 2014; Mehra, et al., 2017). The models suggest that consumers switch channels as a result of the expected benefit they will receive from the change of channel. Consequently, if the perceived benefit the consumers get from switching channel exceeds the cost, the consumer will pursue this action and will thus be more likely to engage in showrooming. The expected benefit can for example be price savings. Schneider and Zielke (2020) and Dahana, Shin, and Katsumata (2018) suggest that one reason why a large segment of consumers engage in showrooming originates from the personal characteristic of being price

17

conscious. In addition, according to Dominique-Ferreira, Vasconcelos, and Proenca (2016), consumers’ price consciousness has increased during the past decades. This further encourages the consumers to engage in showrooming as an approach to find a cheaper price at a competing online retailer.

Bearing this in mind, several researchers suggest for retailers to offer price promotions (Schneider & Zielke, 2020) or a price matching strategy to cope with these situations (Mehra et al., 2017; Schneider & Zielke, 2020). On the contrary, Dahana et al. (2018) claims that strategies that target every customer, such as a price matching strategy, may be too costly and thus have long term negative effects on the profits of the B&M store. Additionally, it acts as a trigger for intensified competition ultimately resulting in detrimental effects for retailers operating both online and offline (Arora, Singha, & Sahney, 2017; Mehra et al., 2017). The critical assumption of these strategies is that price is the essential driver of consumers’ showrooming activity. However, previous research suggest that non-price benefits and costs also have a critical influence on showrooming (Verhoef, Neslin, & Vroomen, 2007).

2.4.1.2 Salespersons Tactics

Several researchers bring up salesperson service as the main factor influencing consumers’ desire to perform showrooming. To begin, some emphasize the quality and characteristics of the salespeople. For instance, Ogruk et al. (2018) state that firms should train their staff to provide friendly, helpful, and communicative service since this creates a unique, positive, and memorable shopping occurrence. Similarly, Bäckström and Johansson (2017) mentions the importance of salespeople’s ability to provide extraordinary quality service. Emphasis must especially be on the maintenance of a proper balance between dimensions, where offering good advice without being pushy is a make-or-break for consumers (Bäckström & Johansson, 2017). On the contrary, findings of Gensler et al. (2017) show that the quality of salespeople does not have an impact on showrooming, rather, the availability of salespeople does. From this viewpoint, the management of salespeople to prevent showrooming should be a matter of quantity and not quality. However, if the service is very poor, showrooming activity may still increase (Gensler et al., 2017).

From another point of view, Rapp et. al (2015) provide evidence that showrooming has a negative impact on salesperson performance, as salespeople increasingly feel like their actions

18

are less likely to result in desired outcomes (i.e. sales). Here, the importance lay in teaching the salespeople to master cross-selling strategies (i.e. the attempted sale of complementary items), as consumers’ ability to engage in direct price comparisons then reduces (Rapp et al., 2015). Others argue, however, that the effect superior salesperson service have on showrooming depends on consumers’ characteristics. More specifically, shoppers who value the social benefits of physical stores and personalized service generally has a stronger tendency to remain loyal towards the B&M store, or at least not engage in competitive showrooming (Schneider & Zielke, 2020).

2.5 Theoretical Summary

By grasping the conceptualisation, the components, and the determinants of the new significance of customer experience, one may understand the complexity in an ever-changing retail environment that is affecting consumer decision making. Further, this complexity in omnichannel environments has stimulated showrooming activity, and it remains a critical issue for clothing retailers to deal with. Through this extensive review of the existing research within the field, a gap has been spotted.

Previous scholars suggest that either price or service may be the most predominant factors that influence showrooming, as these can increase satisfaction enough for consumers to complete their purchase in-store. On the other hand, to increase satisfaction and loyalty as well as to stay competitive in today’s omnichannel era, numerous scholars stress the importance of in-store customer experience. Although, few studies take this one step further, beyond price, service, or a combination of the two, and link a holistic view of customer experience with the showrooming activity. Many scholars de facto agree that the next business tsunami is about grasping the customer experience. The researchers of this study aim to take on this challenge by investigating this connection and therefore shed light to how customers’ in-store experience may affect showrooming in the clothing industry.

19

3. Methodology and Method

___________________________________________________________________________ This chapter begins by addressing the methodology of the research which includes the research paradigm, approach, and design. Furthermore, the method is discussed which includes an elaboration of the primary data, the sampling approach, the development of the interviews and the data analysis. This chapter concludes by discussing the ethical aspect of this research. ___________________________________________________________________________

3.1 Methodology

3.1.1 Research ParadigmThe research paradigm is the philosophical framework that acts as a foundation for how to administer scientific research. This is based on a set of assumptions and ideas of the world which ultimately boils down to two major research paradigms: positivism and interpretivism (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Positivism value objectivity as it acts under the assumption that facts can be proven, and that reality is the same for every man. Research under this paradigm often conduct quantitative rather than qualitative studies to provide high reliability. In contrast, interpretivism deals with subjectivity and thus peoples’ experiences, feelings, and understanding of different phenomenon. Hence, when adopting the interpretivist paradigm, qualitative research is frequently conducted (Ryan, 2018). Interpretivism, as oppose to positivism, work under the assumption that social sciences differ substantially from natural sciences and interpretivist studies thus require a different research logic (Bryman, 2008).

As a result of the purpose and nature of the research conducted in this study, an interpretivist paradigm will be adopted. As the purpose of this study is to explore the customer experience dimension of showrooming, it investigates people’s perceptions and experiences and will hence work with the purpose to explore the deeply rooted subjective meanings of this behaviour rather than explore objective facts. Customer experience is a complex phenomenon which, due to it being subjective in nature, distances itself from the objectivity of a positivistic research paradigm and thus becomes a natural part of the interpretivist paradigm adopted in this study.

20

3.1.2 Research Approach

Following the interpretivist research paradigm, the reasoning and logic behind this study, and the relationship between theory and research, will have an inductive approach. Thus, the study will derive theory as a result of observation and collection of real data (Collis & Hussey, 2014). The research will collect empirical data with the aim to induct general conclusions derived from more specific cases (Collis & Hussey, 2014) which more specifically will be conclusions about customer in-store experience and its effect on showrooming, that is based on more specific empirical research.

In contrast to an inductive research approach, a deductive approach of the relationship between research and theory draws a hypothesis based on already existing theory. Thus, the theory and hypothesis act as a foundation for the proceeding empirical research (Bryman, 2008). However, as a result of the interpretivist nature of this study, the inductive research approach will be adopted. Further, this aims to develop meaningful and beneficial theory that will contribute to existing knowledge.

3.1.3 Research Design

The research design adopted will take a qualitative form as the study will include collection of primary data through the use of interviews, which is a characteristic of a qualitative research design (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Several definitions of qualitative research exist. According to Bryman (2008), qualitative research is a research design that stress the importance of words rather than the quantification of the data in the collection as well as in the analysis process. In contrast, quantitative data is more precise and can normally be applicable to different contexts (Collis & Hussey, 2014). As a result of customer experience being subjective and in this research being studied in the context of showrooming, this research will emphasize words, and the meaning behind them rather than numbers, as a mean in the development of the research design as a whole. Further, this is in line with the purpose of this study and will facilitate the process of answering the research question.

21

3.2 Method

3.2.1 Primary DataFor this study, primary data was collected, analysed, and presented. Primary data may be defined as new data collected by the researchers from original sources, such as own observations, focus groups, or interviews (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Thus, this data collection method aims to generate new insights into the research question(s) with the use of fresh data (Farquhar, 2012).

In inductive studies, new in-depth insights and understandings may be established through semi-structured interviews (Saunders, Lewis, & Thornhill, 2007), which were applied in this study. Before conducting the interviews, however, a pilot test interview was formed. This was a necessary step in the initial stages, as fresh insights from a member of the study population allowed for modification of the interview protocol. More specifically, to ensure that all questions were interpreted as intended by the researchers, certain questions perceived as unclear by the test participant were refined or specified. This essentially enabled for the research question to be answered as the primary data collection was steered in the right direction. Thereafter, 14 additional semi-structured interviews, including one follow-up interview, were conducted with self-proclaimed showroomers As a smaller sample size allows for a deeper and more intense collection of data (Guest, Namely, & Mitchell, 2013) a total of 15 interviews were considered appropriate, with regards to the importance of its depth. Essentially, the aim of such primary data collection was to gather reliable and valid data to help answer the research question (Saunders et al, 2007). Thus, to make sense of how customers’ in-store experience affects showrooming in the clothing industry.

3.2.2 Sampling Approach

Sampling techniques enable researchers to reduce the amount of primary data collected by solely considering data from a subgroup, rather than all elements possible. These techniques are essential since it often is impossible to collect and analyse all the available data, due to restrictions in time, money and access (Saunders et al., 2007). Moreover, sampling techniques are divided into two types, probability sampling where samples are chosen statistically at random, and non-probability sampling which is based on the researcher's subjective judgment

22

and thus, does not select individuals randomly (Saunders et al., 2007). In the interpretive paradigm, the selection of an unbiased sample is not crucial, rather, the aim is to gain deep insights from the cases within the sample (Collis & Hussey, 2014). Hence, purposive sampling, which is a non-probability sampling technique, was selected for the study. Here, researchers can make own judgments and select the cases that make up the sample based on different criteria (Saunders et al., 2007).

Following the purposive sampling technique, interview participants were selected based on three criteria. First, young adults between the ages of 21 and 27 were chosen, since they generally are familiar with digital devices as they grew up in the digital shift (Bento, Martinez, & Martinez, 2018). Second, full-time university students were selected as they often have limited financial means (Universitets- och Högskolerådet, 2015) and thus, may be more sensitive to prices. Third, participants had to be familiar with the showrooming phenomenon and engaged in the activity at least once in the past.

The process of purposefully selecting participants began with that the researchers contacted persons in their network, qualifying for criteria one and two. However, as it was tricky to evaluate if these people also fulfilled the third criterion, potential participants were asked to confirm their relation to showrooming. Thereafter, the final 14 participants could be established. Essentially, these individuals were expected to provide meaningful insights due to their relevance to the topic under investigation, thus, contribute to relevant data necessary to answer the research question.

3.2.3 Semi-Structured Interviews

Interviews may be unstructured, semi-structured, or structured. As interviews within the interpretive paradigm are concerned with exploring underlying reasons for participants’ decisions, attitudes, and opinions, researchers may either take on the unstructured or semi-structured format (Collis & Hussey, 2014). In unsemi-structured interviews, no questions are prepared in advance as they rather evolve during the interview. In contrast, semi-structured interviews consist of some prepared questions, while other questions still may be developed during the interview (Collis & Hussey, 2014). For this study, a semi-structured format was chosen due to two major reasons. First, preparation of questions allowed the

23

researchers not to miss bringing up concepts crucial to the research. Second, the flexibility of asking spontaneous follow-up questions lead to a better understanding of underlying meanings of responses. In sum, semi-structured interviews were conducted as this format was deemed most suitable to provide both relevance and depth to the collected data.

Most of the interviews were held face-to-face in private group rooms at Jönköping International Business School. As the participants were students at the university, this allowed them to feel comfortable in a familiar environment. Due to the outbreak of COVID-19, however, the location of the interviews needed to be further discussed through text-dialogues. The researchers ensured each participant that the group rooms would be carefully cleaned and disinfected, although, they were given the option to participate digitally instead, if they wished. Thus, six out of the 15 sessions were rearranged to digital interviews, with concern to the convenience and comfort of certain participants. To decrease any disparity between the face-to-face and distance interviews, a video service was chosen as opposed to other alternatives such as messaging or phone calls. Like face-to-face interviews, this form allows for facial expressions and other nonverbal communication to be examined, which facilitate for mutual understandings (Guest et a., 2013). The length of the interviews varied from 35-60 minutes, with an average length of 41 minutes (see table 1).

Regardless of the interview format, all sessions were upon confirmation from participants audio-recorded and thereafter transcribed. Furthermore, the interviews were conducted in Swedish, the native language of the researchers and interview participants. This allowed for the interviewees to speak without any restrictions that may arise when speaking a second language, as well as to avoid eventual language barriers. Although, as the interviews and transcriptions were in Swedish, a translation to English of the written quotes used in the report was in order. As translations can be tricky and may negatively affect the validity as well as quality of the collected data and findings, it requires consideration with caution (Birbili, 2000). Thus, to make sure that the translations was in line with what truly had been said, one of the researchers were assigned to translate the quotes from Swedish to English. Thereafter, another researcher reviewed the translation, compared it with the original Swedish version, and noted eventual corrections. Lastly, a discussion between the two resulted in the establishment of the final translated quotes. Overall, this process was deemed to lead to enhanced quality and confidence in the validity of translations.

24

Table 1: Interviewee Overview

3.2.4 Interview Questions

To successfully explore areas of interest in interviews, it is valid to formulate appropriate questions. Saunders et al. (2007) specifies that one should consider using open, probing, and closed questions. Within this study, the semi-structured interviews consisted to a vast majority of open and probing questions. Open questions were established by initiating sentences with “what”, “how”, or with a statement, although, “why” was avoided. The reason for this is because such questions often are less effective when asking for descriptions of lived experiences. For instance, to ask a participant “Why don’t you compare prices?” may cause

Participant Date Age Gender Length Type

1 17/03/20 24 Male 60 Minutes Face-to-Face

2 19/03/20 23 Male 50 Minutes Digital

3 20/03/20 25 Female 35 Minutes Digital

4 20/03/20 23 Female 40 Minutes Face-to-Face

5 20/03/20 08/04/20 27 Female (Follow-up) 40 Minutes 20 Minutes Face-to-Face Digital

6 23/03/20 23 Female 40 Minutes Face-to-Face

7 23/03/20 24 Female 40 Minutes Digital

8 23/03/20 23 Female 40 Minutes Digital

9 23/03/20 23 Male 40 Minutes Face-to-Face

10 23/03/20 24 Female 50 Minutes Face-to-Face

11 24/03/20 24 Female 40 Minutes Face-to-Face

12 24/03/20 21 Male 45 Minutes Face-to-Face

13 02/04/20 23 Male 40 Minutes Face-to-Face

25

feelings of prejudgement and result in defensive or simplified answers (Thompson et al., 1989). Nevertheless, the use of open questions encouraged the participants to share their understandings and provide richness to the data, rather than to collect short “yes” or “no” answers (Guest et al., 2013). Furthermore, probing, which is the activity of asking unscripted questions based on previous responses was practiced with great emphasis. Probing questions allowed the researchers to ask follow-up questions for clarifications and elaborations, contributing to a better understanding of underlying meanings of responses (Guest et al., 2013). Closed questions, however, were only asked in cases where specific information was needed for mutual understanding.

As the questions functioned as a guide to the collection of data, an interview protocol was formed (see appendix 1). The protocol consisted of a total number of 19 open-ended questions with room for probing questions when appropriate. As for the sequence of the questions, each interview was divided into four major parts. The first part consisted of small-talk, explanation of the study, and introduction of participants and their shopping behaviour. Thus, simple questions were asked to build rapport and trust that allowed participants to express their true feelings (Guest et al., 2013). The second part was centred around the interviewees' in-store experiences as well as their relation to showrooming. Here, the participants were, among other things, encouraged to describe their own positive and negative retail experiences. Examples of such questions included: “Can you describe an in-store experience that you recall as especially positive/negative?” and “Can you tell us about a time when you searched for a clothing in-store and later purchased it online?”.

Within the third section of the interviews, the consumer decision-making process laid as a foundation to provide greater substance for the data collection. Here, emphasis laid on the participants’ feelings and behaviours within three of the five in the process. More specifically, Information search, Evaluation of Alternatives, and Purchase, which as previously mentioned were considered relevant in the context of showrooming. However, to adapt this to the contemporary retail environment, the interview protocol did not force the interviewees to follow a sequential order, rather, it allowed for them to speak freely about their experiences within these stages. The interviews were finished off with more narrow questions about retail experiences, to find out what the participants found most valuable. This represented the fourth, and last section of the interviews.

26

With the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, restrictions on social interaction have arisen. In turn, consumption has decreased, and many people now cancel their plans to go to physical shopping malls and similar as a consequence (Bergström, 2020). Thus, one could assume that answers to the questions regarding the interview participants’ consumption habits may have been affected. However, as the interviews were held relatively early in the pandemic, the researchers could not identify any signs of this. An exception, however, was that participant 13 mentioned he had not purchased anything in a while because of the ongoing circumstances. This was mentioned in the beginning of the interview when asking about his shopping behaviour. Nevertheless, as the interviews were to a vast majority based on questions based on past experiences, the current change of shopping behaviour was not referred to further in the interview. Thus, it was deemed that the situation had a minor impact on the final results.

3.2.5 Data Analysis

For qualitative studies to be useful, data should be analysed so that meanings can be understood (Saunders., et al, 2007). To assist the sense-making of the semi-structured interviews, the researchers applied a thematic data analysis procedure. Thematic analysis is a method that identifies, analyses, and reports themes from data in great detail, widely used by qualitative researchers as it provides a flexible way of interpreting complex data (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

To guide the thematic analysis, the study followed a six-phased process, as suggested by Braun and Clarke (2006). Within the first step, the researchers familiarised themselves with the collected data. Thus, the interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed into written documents, which were carefully read through, to examine what truly had been said. The second step involved the production of initial codes of the data. More precisely, this coding process involved a careful and systematic collection of potentially interesting and relevant features for the research. When the data had been collected and coded, focus were directed towards the placement of identified codes into broader themes, which made up step three. To complete this complex task, the authors used a table for visual aid. Through the table, relationships between codes were discovered which resulted in the development of themes. When potential themes had been presented, the fourth step involved a review of the importance of these, where only those considered essential for the research question were kept. The authors affirmed two main themes, where subthemes emerged from each. In step five, the themes were

27

defined and named. Lastly, in the sixth and final step when the themes were set and fully worked-out, the thematic analysis was formulated in writing.

3.2.6 Selection of Quotes

As will be seen from the distribution of selected quotes in the analysis, some participants were more quoted than others. This is due to the quality of how the participants expressed themselves, as the quotes were carefully selected for being the most explanatory of the researchers’ interpretation of the data. The content from unmentioned participants was not less important or less interesting. Rather, it was a matter of how the experiences were articulated, expressed and conveyed that determined the distribution of the selected quotes.

3.3 Ethics

When conducting research projects, several ethical considerations should be taken into account. Research ethics refers to how the research is conducted and how the findings are analysed and presented (Collis & Hussey, 2014). More specifically, it concerns the appropriateness of the researcher’s actions in relation to the rights of those involved in or affected by the work, which should be considered with great care to avoid causing harm (Saunders et al., 2007). To minimise the risk of harming participants in any way, the researchers have taken comprehensive measures to conduct honest, truthful, and overall good research practice. These will be elaborated on in the following sections.

3.3.1 Anonymity and Confidentiality

Anonymity and confidentiality are two concepts in business research that can easily be overlapped with each other. However, there is a significant difference between them. Anonymity refers to the protection of the identity of an individual throughout the research, whereas confidentiality relates to the protection of the information provided by the research participants (Bell & Bryman, 2007).