HÖGSKOLAN I JÖNKÖPING HÄLSOHÖGSKOLAN Avdelningen för rehabilitering

Final administration for thesis

Occupational adaptation in individuals with

Ehlers-Danlos Hypermobility Type: A qualitative

study of personal perspectives

Authors name

Pia Nahi

Thesis, 15 credits, one-year master of Occupational Therapy Jönköping, 12/2020

Supervisor : Sofi Fristedt Examiner : Dido Green

ABSTRACT

Purpose:

This study aims to describe how major symptoms of pain and fatigue affect occupational per-formance and adaptation of individuals with Ehlers-Danlos Hypermobility Type (hEDS). Method:

Eleven individuals with hEDS (2017 diagnostic criteria) were interviewed using a semi-struc-tured questionnaire. The data was analysed following Giorgi’s modified five steps descriptive phenomenological method.

Results:

The following six occupational adaptations emerged during data analysis: Experiences of body unconsciousness, conserving energy in activities, goal setting, restricted physical and social environment, new family role, and healthcare system interventions.

Conclusions:

Experiences of severe fatigue and episodes of severe pain affected the occupational adaptation of daily performance, routines, occupational choices and social and physical environment.

IMPLICATIONS FOR REHABILITATION

Occupational therapists working with individuals with hEDS need to take into consideration the impacts of chronic pain and fatigue on occupational performance and identity.

KEYWORDS

Ehlers-Danlos Hypermobility Type, occupational adaptation, pain, fatigue

Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Hypermobility Type (hEDS) is a heritable tissue disorder with vari-able symptoms that can cause widespread pain and fatigue. HEDS is one of 13 different types of the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), comprising a heterogeneous group of rare monogenic conditions that widely affect the functioning of musculoskeletal system, resulting in for ex-ample: joint and spine hypermobility and dysfunction, easy bruising skin, and osteoarthritis (Tinkle et al. 2017). HEDS represents up to 1–3% of the general population, concentrating more on the female (Tinkle et al. 2017). The other subtypes of hEDS are caused by genetic defects, but the genetic basis of hEDS remains unknown (Syx, De Wandele, Rombaut & Mal-fait, 2017). Musculoskeletal complaints are the most reported ones and have a multi-dimen-sional impact on the individual’s daily life (Rombaut, Malfait, Cools, De Paepe & Calders, 2010; Voermans et al. 2010).

Musculoskeletal pain in hEDS is usually caused by soft tissue structure and joint injuries, but can also be influenced by external factors, such as, lifestyle, physical activity, trauma, or surgery (Castori et al. 2013). The nature of pain in hEDS is thus multi-dimensional and can lead to a chronic and widespread condition through autonomic nerve system (Castori et al. 2013). Individuals with hEDS have a lower control over pain than other groups of people with chronic diseases (Rombaut et al. 2011). The quality of chronic pain is also affected by a lack of proprioceptive acuity and muscle weakness leading to decreased levels of physical activity (Syx et al. 2017). Chronic pain is often related to psychological conditions, such as fear and anxiety (Bulbena et al. 2017; Syx et al. 2017).

Individuals with hEDS suffer from persistent fatigue in addition to pain. Although the mean-ing of pain has been studied more than the meanmean-ing of fatigue, the latter has a greater impact on daily activities (Voermans et al. 2010; Voermans & Koop, 2011; Krahe, Adams & Nichol-son, 2017). Krahe et al. (2017) have identified five determinants of fatigue, such as the self-perceived dimension of joint hypermobility, orthostatic dizziness, social and physical partici-pation, physical activity, and dissatisfaction with medical treatment given by healthcare pro-fessionals, which affect the individuals’ capacity to cope with their condition.

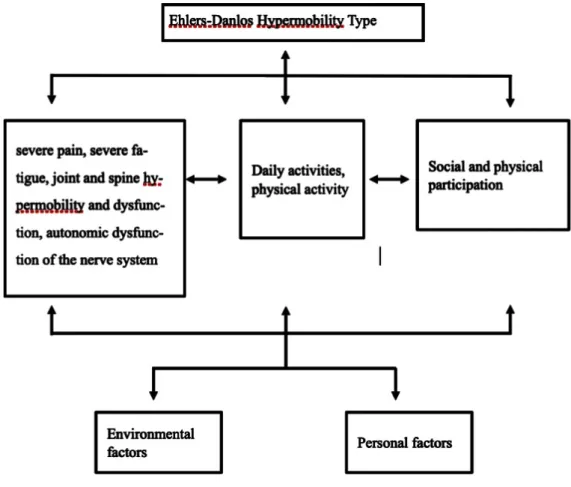

International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) was created by the World Health Organization, and it provides a broad description of an individual's health through a biopsychosocial approach. The ICF classification provides a tool to understand,

ex-plore, structure, and describe individualised elements of performance, health, and disability (WHO, 2018. See figure 1) In this study, the ICF classification is used to clarify the factors of occupational performance and adaptation of individuals with hEDS.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of ICF used in the occupational adaptation with hEDS

Conditions of hEDS cannot be perceived by clear, genetic etiology, and are therefore poorly understood (Krahe et al. 2017; Castori et al. 2013; Terry et al. 2015; Hakim, De Wandele, O`Callaghan, Pocinki & Rowe, 2017; Murray, Yashar, Uhlmann, Clauw & Petty, 2013). Diag-nosing is challenging because healthcare practitioners may be unaware of the syndrome (Lyell, Simmonds & Deane, 2016; Rombaut et al. 2011) and there is no healthcare pathway for the management of hEDS (Palmer et al. 2016).

Occupational adaptation is defined in literature as results of action of occupational identity and competence (Kielhofner, 2008), as a response to occupational challenges (Schkade & Shultz, 1992), or as becoming through being and doing (Wilcock & Hocking, 2015).

Occupa-tional adaptation can also be seen as an outcome of participation (Kielhofner, 2008; Wilcock & Hocking, 2015).

In short, hEDS is a multidimensional syndrome with individual, but enormous and continuous effects on occupational performance including how people with hEDS adapt to their daily ac-tivities. However, less is known about this from a subjective perspective.

Method

This study aims to describe the experiences of individuals with hEDS focusing on how major symptoms of pain and fatigue affect occupational adaptation in their daily performance, rou-tines, occupational choices, and environment. Thus, phenomenology, especially descriptive phenomenology, was chosen as the research method.

Approach of this study

A qualitative design was chosen as a relevant approach because life experiences of individuals with hEDS have received only a little attention (Terry et al. 2015). The meaning of this study is to produce descriptive information that enhances the understanding of their occupational adaptation and increases information on rehabilitation.

Participants

This study meets the criteria for ethical research (see Appendices 1 and 2). Individuals for the interviews were recruited via the Finnish patient organization Suomen Ehlers-Danlos Yhdis-tys SEDY by a written invitation sent to all its members (see Appendix 3). Inclusion criteria was hEDS (Hypermobile EDS) diagnosed based on the new 2017 criteria set by the In-ternational Consortium on Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (The Ehlers-Danlos society, 2019). All

potential participants received a more detailed information letter stating that participation was voluntary, and that it was possible to withdraw from the study at any time without providing any explanation and ensuring confidentiality (see Appendix 4). At this point, three potential participants withdrew. The informed consent was sent to the remaining participants before the interviews and the data collection took place (see appendix 5). The participants were sent sep-arate emails about the time and place of the interview. The interviews took place between July and September 2018. The confidentiality of the participants was secured and protected throughout the research process by using codes (Kvale, 2007). The names of the interviewees were coded as male 1-4 and female 5-11.

Procedure

In June 2018, two pilot interviews were conducted. Following these interviews, the order and language of the questions was edited for better clarity. For example, professional language and concepts used were translated so that they could be understood by laypersons. These pilot interviews are not included in this study.

Eleven interviews were conducted from July to September 2018. Interviewees lived in differ-ent places around Finland and were contacted via differdiffer-ent medias. Six individuals were in-terviewed face to face at their homes or in other places of their own choice, four interviews were done via video calls, and one interviewee wanted to give a written description; all these are acceptable methods in phenomenological research (Giorgi, 2009). One interview was con-ducted twice because of technical problems. The second interview is included in this study . 1

Interviewees were asked to describe in detail how pain and fatigue affected their lives. The length of the interviews was approximately 60–90 minutes.

Data Analysis

The interview was conducted in the same way 1

After transcribing the interviews, a complete data analysis was done following Giorgi’s modi-fied five steps method from Husserl’s descriptive phenomenological method to obtain an open experience (Giorgi, 2012. See Appendix 6, Table 1 for details.) The steps were the following: 1. Each transcript was read several times with an open mind. 2. Transcripts were reread specifically from an occupational therapy perspective to derive meaning units. 3. The mean-ing units were transformed into professional language of occupational therapy (see Appendix 6, Table 2). 4. Individual meaning units were created by constituting relevant and repetitive expressions of occupational adaptation with pain and fatigue to the essential structure of expe-rience (Giorgi, 2012. See Appendix 6, Table 3). 5. General meaning units were created so that each phenomenon formed an individual meaning unit and relevance to the phenomenon was studied (Giorgi, 2012. See Appendix 6, Table 4).

Results

Four of the interviewees were men and seven were women (See Table 1). Men were aged be-tween 39–54 years (average 44) and women bebe-tween 24–54 years (average 37). However, one of the female interviewees wished not to reveal her age. All interviewees were independent in self-care. Two interviewees needed permanent help in their daily lives, and other interviewees needed help only regularly in some activities (for example opening a jar), or periodically due to pain-causing activities such as cleaning, gardening, and shopping. Although interviewees had received a diagnosis based on the new 2017 criteria, they had also received a diagnosis filling the older standards or had symptoms consistent with the syndrome.

Age Professio-nal status Family sta-tus Children Rehabilita-tion

male 1 46 student married 4 a short physiothe-rapy inter-vention male 2 38 working full-time intimate relationship short phy-siotherapy and occu-pational therapy in-terventions male 3 54 working full-time

married 2 (adults) self-paid chiroprac-tor male 4 40 permanent disability pension intimate relationship 1 no female 5 42 working full-time married self-paid manual treatment

female 6 24 student married 3 self-paid

personal trainer female 7 38 permanent disability pension single cognitive therapy

Table 1. Participant demographics

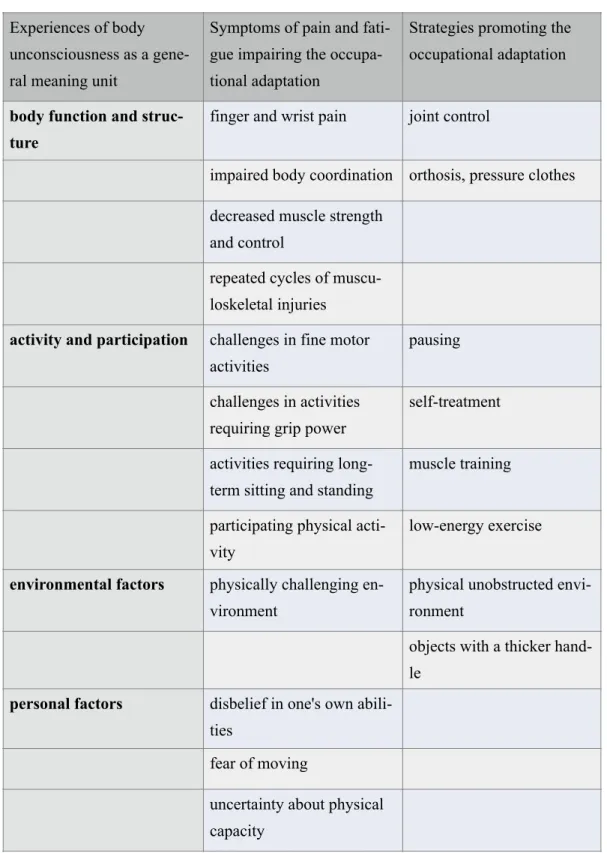

The results are presented to illustrate how pain and fatigue affect the individuals’ occupational performance and which occupational adaptation strategies they used. Six meaning units and specific key features are represented according to ICF. Quotes from the interviews are sepa-rated by quotation marks and tend to follow each interviewee’s speech.

Experiences of body unconsciousness

Most of the interviewees reported repeated cycles of musculoskeletal injuries and joint prob-lems that affected their physical capacity in different ways (see Table 2). All interviewees

suf-female 8 45 a part-time disability pension and a part-time job married 2 no

female 9 round 54 permanent disability pension single 2 (adults) no Female 10 29 working full-time single a short physiothe-rapy inter-vention

female 11 33 student single 1

physiothe-rapy, occu-pational therapy

fered from joint pain in their fingers and wrists and had challenges when adapting to physical hand-related activities, such as taking down goods from the shelf or carrying the shopping bag. All interviewees reported tired and painful hands when performing activities that re-quired a long-term concurrent strength, tight pinch grip, or fine motor skills such as guitar playing, knitting, or drawing. Interviewees had, however, different methods to adapt to hand-related pain in order to engage in meaningful activities (See Table 2).

“I must put (my) hands into cold water sometimes, shake and massage them before continu-ing... my hands become really exhausted” (Interviewee 1)

Hypermobility led most interviewees to somewhat reduce their engagement in energy-de-manding leisure occupations, such as all ball games, gymnastics, or running. Activities requir-ing body coordination and balance, such as skirequir-ing, dancrequir-ing, or hikrequir-ing were more difficult to engage in. Interviewees found the participation too demanding, if they had pain affecting such occupations which they were used to engage before.

“The thumbs bent while playing basketball, and the hard feeds went straight through. My knee pain stopped when I stopped playing basketball” (Interviewee 3)

The interviewees often did not know which physical activities suited them, and how they could improve physical abilities. They wanted to be able to continue their previous physical activities or start new ones, but they could not trust the stability of their joints and bodies. All interviewees avoided static positions such as long-term sitting or standing, and some were unwilling to participate in activities requiring body control or physical stamina. Body control was directly related to pain and fatigue. Some interviewees tried to compensate their weak muscle control by supporting their bodies with the surrounding physical environment, cross-ing their arms or legs, or by uscross-ing tight clothes. However, for those interviewees whose body control had ‘suddenly deceived’ them, had an increased fear of moving, especially in stressful situations or when fast or sudden movements were required.

“I used to run to the bus and sometimes my knee and my leg got stuck and I fell on my face” (Interviewee 11)

Table 2. Key features of experiences of body unconsciousness, symptoms and strategies for occupational adpation according to ICF classification

Experiences of body unconsciousness as a gene-ral meaning unit

Symptoms of pain and fati-gue impairing the occupa-tional adaptation

Strategies promoting the occupational adaptation

body function and struc-ture

finger and wrist pain joint control

impaired body coordination orthosis, pressure clothes decreased muscle strength

and control

repeated cycles of muscu-loskeletal injuries

activity and participation challenges in fine motor activities

pausing

challenges in activities requiring grip power

self-treatment

activities requiring long-term sitting and standing

muscle training

participating physical acti-vity

low-energy exercise

environmental factors physically challenging en-vironment

physical unobstructed envi-ronment

objects with a thicker hand-le

personal factors disbelief in one's own abili-ties

fear of moving

uncertainty about physical capacity

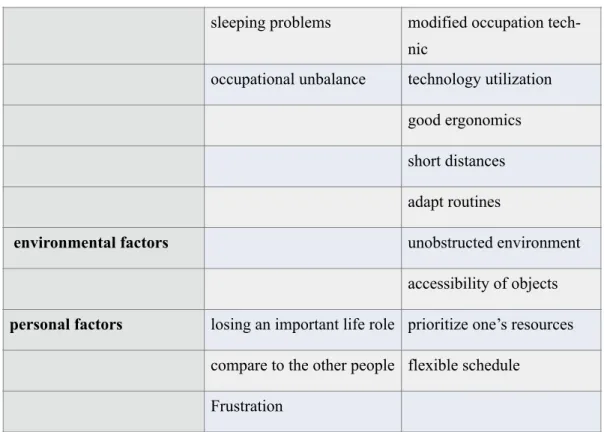

Conserving energy in activities

The cause of interviewees’ fatigue was difficult to identify, which caused plenty of frustra-tion. Fatigue was more emotionally disturbing than pain because effective methods for adapt-ing to it were difficult to find. Constant, intense pain also increased fatigue, which intensified the need to rest and conserve energy (see Table 3).

All interviewees experienced their work-to-rest balance often inadequate. The interviews were mainly conducted during the holiday season, when the interviewees described their occupa-tional balance as improved.

“Right now, as I'm on vacation, I can manage my personal hygiene, and my work and rest. Balance is good” (Interviewee 5)

Interviewees with severe pain and fatigue had sleeping problems, which resulted in afternoon naps, as the quality of sleep at night was not sufficient.

Interviewees had to prioritise their use of energy mostly to the essential or productive occupa-tions, self-care, and household tasks. Adaptation to daily routines was better when using their own resources: it increased the occupation’s meaningfulness and the sense of capability. All interviewees had gone through a transition process in their professional lives: some ad-justed their work tasks to lighter ones and others changed their working status completely. Occupational challenges caused frustration and a sense of incompetence, increasing anxiety towards the future. Energy conservation also had psychological dimensions: fear of increased stress decreased the willingness to pursue a career. The interviewees conserved energy and avoided stress by acquiring a more flexible schedule.

“…if there is too little time for doing something independently, I don’t like it... because it is challenging to adapt to my own health condition... I've always wanted a flexible schedule” (Interviewee 9)

The interviewees who adapted successfully were more able to engage in their work, and the ones who could not influence their work patterns were often fatigued in their leisure time, leaving out relaxing activities of their own choice.

Some interviewees had significant challenges managing their housework and received outside help. Mostly a compromise on previous cleaning conceptions and becoming used to a less clean environment was the solution. Assistive devices were not used, even though they were sometimes needed.

“probably a thicker handle, so you could hold on to it better... the peeling knife handle is quite thin, and you have to squeeze it terribly… and when you start peeling, the hand gets tired” (Interviewee 1)

Interviewees were independent in occupations related to self-care. However, some had adapt-ed so that some self-care activities were done less frequently, such as washing their hair. In-terviewees also adapted their dressing activities by buying more easily worn clothes, such as shoes without tie-downs or shirts without buttons. One habit to conserve energy was to reor-ganise their physical environment into a more convenient one.

Conserving energy in activi-ties as a general meaning unit

Symptoms of pain and fati-gue impairing the occupa-tional adaptation

Strategies promoting the occupational adaptation

body function and struc-ture

severe pain

control fatigue control fatigue

activity and participation difficult to participate a leisure time

retraining

difficult to participate re-laxing activities

change working patterns

Table 3. Key features of conserving energy in activities according to ICF classification

Goal setting

Hardly any interviewees set specific long-term goals for the future. They usually set more ab-stract long-term goals related to a desire to keep themselves functioning as long as possible by improving their physical condition (see Table 4). Interviewees set task-oriented short-term goals for work and home environment, such as how to fix a shelf at work, or carry firewood indoor at home. Managing adaptation to daily routine was generally considered as a meaning-ful short-term goal, increasing self-esteem and a sense of capability.

“But I have to eat that warm food, that's what I always try to do, and I've always done it so far... that's the last thing I’ll give up on” (Interviewee 1)

Interviewees were always mentally prepared for changes in their plans and goals, and partici-pation level often depended on the amount of pain and fatigue. The constant, periodically

sleeping problems modified occupation tech-nic

occupational unbalance technology utilization good ergonomics short distances adapt routines

environmental factors unobstructed environment accessibility of objects

personal factors losing an important life role prioritize one’s resources compare to the other people flexible schedule

stronger and wave-like pain together with fatigue affected negatively on goal setting and en-gagement in daily occupations. Targeting resources was difficult, thus mastering an activity was seldom reached. Interviewees with severe fatigue were particularly uncertain about their ability to adapt to occupations or integrate them into their routines. The increased need for resting and the difficulty to control fatigue limited their occupational choices and goal setting. Although the interviewees’ struggles in achieving goals induced bad conscience and guilt, the pain and fatigue guided them to engage in more peaceful and creative occupations, such as writing stories or knitting caps.

Temporary, meaningful occupations, though affecting negatively afterwards on their perfor-mance capacity, were willingly engaged in.

“Yes, that opera goes when you take painkillers... and then there’s a break” (Interviewee 2)

Interviewees had engaged in some meaningful occupations before, from which they had achieved mastery, but which they had to abandon due to increased pain or fatigue. The inter-viewees’ expectations of themselves were often based on their former skills and abilities, forming a contradiction between the contemporary situation.

“I was able to pass the language proficiency tests, so maybe I could set some goals” (In-terviewee 11)

However, interviewees who had learned to redefine their level of activity and goal setting had also learned how to respond better to their occupational challenges. Some interviewees have successfully engaged in some leisure occupations through graded exercise training: starting slowly and increasing amount of training little by little.

“It started out so that I was walking 600m in February 2016 and was totally exhausted... two or three weeks ago I walked more than 10km everyday... and it was too much”(Interviewee 1)

Goal setting as a general meaning unit

Symptoms of pain and fati-gue impairing the occupa-tional adaptation

Strategies promoting the occupational adaptation

Table 4. Key features of goal setting according to ICF classification

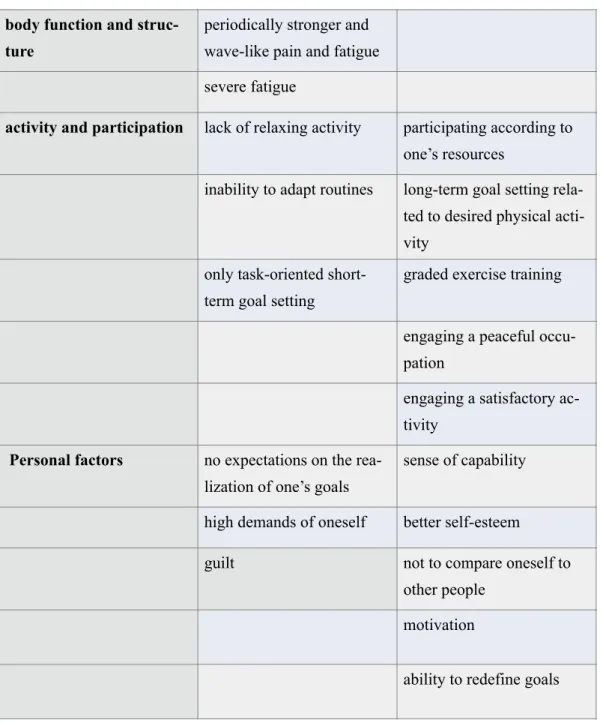

Restricted physical and social environment

Severe pain and fatigue with repeated cycles of musculoskeletal injuries restricted physical and social participation (see table 5). Social life was clearly not included in their regular rou-tines anymore and was often dependent on the amount of pain or fatigue. Amount of physical social contacts fluctuated from less active to a near isolation. Some of those who were less

body function and struc-ture

periodically stronger and wave-like pain and fatigue severe fatigue

activity and participation lack of relaxing activity participating according to one’s resources

inability to adapt routines long-term goal setting rela-ted to desired physical acti-vity

only task-oriented short-term goal setting

graded exercise training

engaging a peaceful occu-pation

engaging a satisfactory ac-tivity

Personal factors no expectations on the rea-lization of one’s goals

sense of capability

high demands of oneself better self-esteem

guilt not to compare oneself to other people

motivation

active in physical contacts were more active in social media. Friendships survived if the indi-viduals experienced acceptance despite having a condition related to pain and fatigue, and if they were accepted as such by their social environment.

Visiting other people raised uncertainty, and adaptation to social life was easier if interaction occurred at home where the opportunity to rest was available. Interviewees wanted to be con-fident in managing their resources, and often needed to know how long they could be out on a visit. All found social situations exhausting, especially when they were expected to stand for longer periods or travel far. Visiting people at a shorter distance was regarded helpful.

However, their social life had diminished as fatigue increased. Also, severe pain increased irritation and tenseness making the adaptation to social situations challenging at times, so they mainly chose to be alone at home.

“You are just so out of everything else and it's just that pain” (Interviewee 10)

Interviewees refused to identify as disabled persons, even though some of their friends had abandoned them because of their accused syndrome-centred attitude. Therefore, some did not want to be open-minded and expected the social environment to accept participation on their own conditions.

“Generally, I am just at home… my friends are used to it, they don’t ask me to participate any more… I visit once a year when their kids have birthdays... then I visit… not other times” (Interviewee 6)

Some interviewees chose to live in solitude without an intimate relationship because they found it more relaxing that way. They did not, however, want to be a burden to their relatives and hoped to return any favours.

Restricted physical and social environment as a ge-neral meaning unit

Symptoms of pain and fati-gue impairing the occupa-tional adaptation

Strategies promoting the occupational adaptation

Table 5. Key features of restricted physical and social environment according to ICF classifi-cation

body function and struc-ture

severe fatigue

severe pain

repeated cycles of muscu-loskeletal injuries

activity and participation long physical and social distance

social participation

increased need for resting conditional participation challenges to drive car

challenges of long-term standing

lack of social routines

environmental factors isolation social media expectations to have pain

and fatigue in social situa-tions

acceptance of the social environment

one’s expectations to be accepted

social life in home envi-ronment

personal factors irritations identity of a person without disability

tenseness experience of being accep-ted

disbelief in one’s resources experience of being a bur-den

New family role

Before, the interviewees’ family role had been more physically active, but now joint pain or musculoskeletal complaints limited their participation in physically demanding occupations, such as hoovering or gardening (see Table 6). However, adaptation to less physical activities, such as cooking or taking care of the children, was possible. This occurred naturally, especial-ly if interviewees had been open about the syndrome and tried to share famiespecial-ly life and respon-sibilities according to their resources. Disagreements had arisen when a family member or a significant other was expecting a greater initiative or activity without understanding the con-dition, or when interviewees addressed irritation to family members due to pain or stress. Be-fore receiving the diagnosis or any awareness of the condition there were more family con-flicts.

“Then I started to think that maybe I am just lazy and so... well I’m not, and I went through it terribly lot... at first it was terribly challenging, and there were lots of quarrels because when I did something, or slept a lot, and like that” (Interviewee 6)

Interviewees focused more on family life after the transition from a more active and produc-tive life was done. A more acproduc-tive role as a parent increased their adaptation to family life and gave them more satisfaction to master their role as a parent. Interviewees were more present in their new family life and enjoyed more the company of their children. They wanted to pro-tect their children from the anxiety caused by the syndrome by trying to hide their pain and fatigue and emphasizing that they were living an ordinary life. Family was the most important source for a significant positive resource among the interviewees who had chosen a family life. Interviewees also got help and were supported by the family and relatives if needed. Those who did not want or could not ask for help from their relatives experienced feelings of being a burden to others.

Table 6. Key features of new family role according to ICF classification

New family role as a gene-ral meaning unit

Symptoms of pain and fati-gue impairing the occupa-tional adaptation

Strategies promoting the occupational adaptation

body function and struc-ture

repeated cycles of muscu-loskeletal injuries

severe fatigue and pain

activity and participation participating physical occu-pations

participating less physical occupations

sharing family life and res-ponsibilities

relieving stress on a family member

mastering family life

presence in family life active parental role

environmental factors unrealistic expectations of activity

openness towards the syndrome

disputes arising from fati-gue

accepting the family at-mosphere

help from family members

personal factors stress family as a positive re-source

irritation received diagnosis enjoying the company of children

Healthcare system interventions

Pain or fatigue had been a part of the interviewees’ life since their childhood. They have visit-ed doctors as children, some of them several times, but their pain was associatvisit-ed with growth pain and fatigue was ignored, nor were they supported to adapt to their school related activi-ties, such as sitting in the classroom or concentrating on their schoolwork.

Interviewees have been through one or several serious symptoms or surgical operations caus-ing increascaus-ing pain without findcaus-ing any explanation to it. They also experienced anxiety, stress, or even fear of dying because of these unexplained symptoms and operations (see Ta-ble 7). Uncertainty about their health and anxiety about their future performance made it diffi-cult for most to respond to the occupational challenges of daily activities.

“I lived with the fear of dying for two years and was wondering when I’m going to die... be-cause all was wrong and nobody could say anything, and at the same time my legs didn't work and were weak” (Interviewee 8)

The diagnostic process was sometimes a long and arduous one, and several doctor visits took place for years without any explanatory information about the syndrome. Information on hEDS would have been important so that learning about the adaptation to occupational chal-lenges and building a new occupational identity could have taken place. Interviewees mainly searched for information themselves in scientific articles, the internet and peer groups, form-ing their own understandform-ing of their symptoms.

Most of the diagnoses were given by private healthcare doctors who were more familiar with hEDS. Diagnostic criteria did not cover the hypermobile spine, which was one of the main concerns of the interviewees, and fatigue was ignored. Interviewees have accepted the pain and adapted to it, but they have had challenges adapting to the fatigue. After diagnosis, some interviewees had a short intervention related mainly to musculoskeletal complaints. Some did not receive any therapy or treatment although they would have needed it. Interviewees ex-pected to gain individual or multidisciplinary approach and increased pain management to respond better to their occupational challenges. However, they did not experience being heard or that their needs had been fulfilled. In fact, they reported being seen as demanding, difficult

persons by the healthcare system, when they just would have liked to engage in daily occupa-tions like other people.

“The exercises that I got didn't help... either I was too sick, and they didn’t want me there, or then they said that every move you do is wrong” (Interviewee 10)

Most of the interviewees would also have needed guidance or support to be able to engage in regular physical activity. If possible, they practiced at their own expense with a personal trainer, an osteopath, a private chiropractor or a physiotherapist.

Obtaining a diagnosis increased the interviewees’ understanding of the syndrome. It activated a process of accepting the pain, helped to adapt to a new occupational identity, promoted adaptation to a varying performance capacity, released the feeling of guilt, and provided a tool for better adaptation to social and physical environments.

“For me, it’s enough that I can get a good life and that I can make it meaningful for the rest of the world, so that I am successful - even in some way - to leave a positive trace in the world, and more than that” (Interviewee 7)

Healthcare system interven-tions as a general meaning unit

Symptoms of pain and fati-gue impairing the occupa-tional adaptation

Strategies promoting the occupational adaptation

body function and struc-ture

repeated cycles of muscu-loskeletal injuries

effective pain treatment

lifetime fatigue

lifetime pain

surgical operations various severe symptoms

Activity and participation non-respond to

occupatio-nal challenges

guided physical activity

Table 7. Key features of healthcare system interventions according to ICF classification

The general adaptation strategy type persons related to general meaning units of interviewees

Similar adaptation strategies emerged from the meaning units of individuals with hEDS. Five types of adaptation strategies related to meaningful units that differed in their content from specific content areas were observed. Distinguishing factors included, for example, one's satisfaction to their life situation, engagement in meaningful occupations, or main-taining of interpersonal relationships. The adaptation strategies of meaning units among the interviewees are described as follows:

physically, socially and mentally adapted occupa-tions

environmental factors long diagnosis process intervention related to fati-gue

no healthcare interventions multidisciplinary approach disappointment to

healthca-re intervention

appropriate information

support from healthcare individual intervention

personal factors anxiety active information retrieval

stress a new occupational identity experience to be a

1. Occupation-focused individuals were mostly satisfied with how they perform daily tasks. They accepted their syndrome and often searched for more information on it. These individu-als reported independence when performing daily occupations. They were mostly self-direct-ed in rehabilitation if it was neself-direct-edself-direct-ed, and they did not expect much support from the healthcare system. They were mainly confident about their abilities, but at the same time possibly wor-ried about their future.

2. Process-focused individuals needed to change their lifestyle which emphasized productivi-ty. They did not feel competent the way they currently performed their daily lives and how they could engage in meaningful occupations, particularly in physical activities, and used to compare themselves to their previous lives. These individuals have stopped setting long-term goals and reduced their adherence to routines. Their process of accepting the pain and fatigue was often incomplete, they worried about their future and often experienced stress. Their rela-tionship with the healthcare system was very unsatisfied, as they would have preferred a more active and intensive approach from them.

3. Stable-focused individuals would like to have their lifestyle as stable as possible. They got support from rigorous routines, although adhering to timetables set by others and large changes caused stress. They set mainly short-term goals and had difficulties to relax. They were not especially pleased with how their pain was treated and would have liked to have bet-ter pain treatment and rehabilitation.

4. Family-focused individuals had family giving the most satisfaction to their lives. They mainly stay at home. At the present, they valued above all their roles as parents and their short-time and conditional goals were related to family life. These individuals regularly need-ed help from a family member, and they applineed-ed work and rest to their pain and fatigue. They are worried about symptoms for which there are no explanations and are disappointed with the lack of healthcare interventions and the lack of expertise.

5. Support-focused individuals had relinquished productive major life roles, but could have engaged to a new, often peaceful, or less physical occupation. These individuals participated few activities outside their homes and conserved energy to necessary daily activities. They perform self-care activities independently, but less frequently. They reported an increased

need for rest, and they often adapt routines mildly according to resting periods. They live in-dependently but need regular outside help especially for their IADL activities and cleaning. They often have experiences of not being heard or understood by the healthcare and expect a supportive approach and concrete intervention from them.

Experiencing one's own situation involves environmental and personal factors that promote and prevent occupational adaptation, such as experiences of one's own self and satisfaction with one's own situation and syndrome.

Discussion

These findings illustrate that daily performances, routines, occupational choices, and the envi-ronment of a genetic syndrome phenomenon were identified from the experiences of individ-ual meaning units of interviewees with hEDS. The general units of experiences revealed by the interviewees, such as body consciousness and goal setting, affected levels of functioning. Utilisation of the ICF as a framework for understanding the impact of pain and fatigue on ac-tivity capacity, occupational performance, and participation highlighted the importance of personal factors (e.g. self-resourcefulness) and the environment (particularly family).

In this study, the interviewees’ pain fluctuated from local joint pain to widespread chronic pain, which increased disability, as is stated also in the study of Castori et al. (2013).

The interviewees considered both pain and fatigue as the most effective factors in reducing their activities and participation. The effect of fatigue on daily occupations was remarkable and consistent with the studies of Voermans et al. (2010), Voermans & Koop (2011) and Kra-he et al. (2017). TKra-here were similarities in tKra-he results related to severe fatigue to those associ-ated with difficulty to set long-term goals (Terry et al. 2015; Kielhofner, 2008) and intermit-tent need to rest during the day (Voermans et al. 2010).

Fatigue was a major personal factor in causing guilt and disbelief in one’s own abilities, lead-ing often to inability to adapt to regular routines (which were factors in greater disease severi-ty), a failure to develop compensatory habits, and the ability to adapt roles to one’s occupa-tional capacity (Taylor et al. 2003). Future anxiety was also strongly emphasized as a personal

factor in relation to economic and health issues. Also, a study by Berglund et al. (2015), high-lighted anxiety as a most commonly reported factor along with fatigue. Anxiety was also as-sociated with hypermobile joints (Bulbena et al. 2017). Those interviewees, whose activities and occupational choices changed according to their resources were concerned about how they can adapt to the demands of society, and those who were able to participate in normal life were worried about how far in the future they could continue doing so. Continuous and un-controlled activities were debilitating factors in achieving an optimal state of consciousness, increasing internal and bodily awareness, and enabling experiential outcomes that are central to experiencing physical and mental health and well-being (Wilcock & Hocking, 2015).

The indicators of social and physical environmental factors related to the results were the need for rest, getting around outside one’s home, the unwillingness to visit people living fur-ther away, and attitudes and expectations of the social environment. Reduced social participa-tion related to hEDS has also been recognised in several studies leading even to isolaparticipa-tion (Vo-ermans et al. 2010; Clark & Knight, 2017; De Baets, 2017). Adaptation to social environment was better, if it occurred in the home environment and was supported by acceptance.

The occupational adaptation was continuous and dynamic, which was congruent with other studies on people with chronic illness (Lexell, Ivarsson & Lund, 2011). Those interviewees who had previous experiences on occupational adaptation had strategies to promote roles, routines, and abilities. The link between occupational adaptation and occupational identity was highlighted. Occupational identity reconstruction is evolved through previous experi-ences on goal setting, routines, roles, and motivation (Kielhofner, 2008).

Half of the interviewees had a short physiotherapeutic intervention after receiving their diag-nosis, one received cognitive therapy and two had occupational therapy targeted at body pos-ture and support for performing daily activities. The other half did not receive any rehabilita-tion, but a part of them paid chiropractic, manual treatment, or the support of the personal trainer themselves. Pain was treated with medication, but fatigue was not addressed by healthcare. The conclusions of several studies, however, include a recommendation for a mul-tidisciplinary rehabilitation in relation to pain and fatigue (Hakim et al. 2017; De Baets et al. 2017; Chopra et al. 2017; Krahe et al. 2017; Voermans et al. 2010).

HEDS needs to be diagnosed early in order to help the individual to manage with chronic pain and fatigue and response to occupational challenges before developing disability, as is also stated in the 272727studies of Chopra et al. (2017) and Terry et al. (2015). Pain and fatigue should both be evaluated, and fatigue should be considered in treatments, which is pointed out by Voermans & Knoop (2011), Krahe et al. (2017) and Voermans et al. (2010). The connec-tion between intense pain and fatigue was identified also in this study and made the need for more effective pain management important, as Rombaut et al. (2011) suggests. Interviewees in this study did not experience that general healthcare interventions promoted their health and well-being as is also described by Clark & Knight (2017). In addition, many experienced a sense of stigma and embarrassment, also reported by Terry et al. (2015). It was considered very important that the healthcare professionals should understand the nature of the syndrome better and recognize how to empower and motivate individuals with hEDS, supporting their participation, as studies of Clark & Knight (2017), Rombaut et al. (2011) and Berglund et al. (2015) describe. The importance of education and having adequate information was empha-sized; it would be important for individuals with hEDS to make informed healthcare choices (Terry et al. 2015).

According to the experimental knowledge and the literature used in this study, there are many central elements of occupational therapy related to occupational adaptation of hEDS. Occupa-tional therapists have an important and versatile role to support occupaOccupa-tional adaptation as follows: pain and fatigue education, learning to organise living according to available energy, supporting occupational choices and helping in finding a balance between activity and rest (De Baets et al. 2017; Wilcock & Hocking, 2015, Hakim et al. 2017). The occupational thera-pist is a part of multidisciplinary team focusing on adaptation to lifestyle changes including pacing, changing sleep patterns, supporting to change job or hours to work and adaptation (as-sistive devices), gaining more independence (Hakim et al. 2017), and teaching adapting strategies to improve participation (Krahe, et al. 2017). The role of an occupational therapist may be to teach relaxation technics, supervised and structured graded exercise therapy, client-centred goal setting, education for managing setbacks, planning and prioritising daily activi-ties and splitting activiactivi-ties in smaller, achievable tasks (Hakim et al. 2017). From a physical point of view, occupational adaptation to pain and fatigue can be targeted at promoting psy-chosocial and physical well-being (Rombaut et al. 2010), stabilising loose joints with bracing

and taping and improving ergonomics at home, study and workplace (Castori et al. 2013), and educating holistically to find ways for self-management and exercises (Terry et al. 2015).

One limitation to this study was a low number of interviewees, so the results have to be inter-preted with some prudence. Selection bias may have occurred in that the more active individ-uals were also more willing to be interviewed. Participants were recruited through the EDS society, so the members may have been more conscious about the syndrome than others. Be-cause the performance of the individuals varied a lot, it was difficult to get a consistent picture of hEDS. The punderstanding and previous experiences of the author can influence the re-search process (Giorgi, 2012), but the information obtained from the interviews is very valu-able and adds to the understanding of the individuals with hEDS. The author had challenges to adapt the method of free imaginative variation and completely exclude her own mindset towards occupational adaptation with pain and fatigue (Giorgi, 2012.). Meaning units’ content in the second step of the method guided much of the author’s creating process of the general meaning units.

Conclusion

A phenomenological approach has highlighted the impact of pain and fatigue on the occupa-tional performance and participation of individuals with hEDS. The varied experiences and strategies used reflect the unique life experiences of people with hEDS. Occupational thera-pists need to consider individual perspectives and available resources when considering the pain and fatigue to support occupational adaptation. Future research should focus on the ef-fects of fatigue in everyday life by using an evidence-based assessment method.

References

American Psychological Association (2020). APA Style. https://apastyle.apa.org/. Referenced source 19.4.2019.

De Baets, S., Vanhalst, M., Coussens, M., Rombaut, L., Malfait, F., Van Hove, G., Calders, P., Vanderstraeten, G.& van de Velde, D. (2017). The influence of Ehlers-Danlos

syndrome -hypermobility type, on motherhood: A Phenomenological, hermeneutical study. Research in Developmental Disabilities 60 (2017) 135-144.

Berglund, B., Pettersson, C., Pigg, M. & Kristiansson, P. (2015). Self-reported quolity of life, anxiety and depression in individuals with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS): A

questionnaire study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 16:89. DOI 10.1186s12891-015-0549-7.

Bulbena, A., Baeza-Velasco, C., Bulbena-Cabre, A., Pailhez, G., Critchley, H., Chopra, P., Mallorqui-Bague, N., Frank, C. & Porges, S. (2017). Psychiatric and Psychological Aspects in the Ehlers–Danlos Syndromes. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C (Seminars in Medical Genetics) 175C:237–245.

Castori, M., Morlino, S., Celletti, C., Ghibellini, G., Bruschini, M., Grammatico, P., Blundo, C. & Camerota, F. (2013). Re-Writing the Natural History of Pain and Related Symptoms in the Joint Hypermobility Syndrome/Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome,

Hypermobility Type. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A 161A:2989-3004.

Chopra, P., Tinkle, B., Hamonet, C., Brock, I., Gompel, A., Bulbena, A. & Francomano, C. (2017). Pain Management in the Ehlers–Danlos Syndromes. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C (Seminars in Medical Genetics) 175C:212–219 (2017).

Giorgi, Amadeo (2009). The Descriptive Phenomenological Method in Psychology. A Modi-fied Husserlian Approach. Duquesne University Press, Pittsburgh,

Pennsylvania.

Giorgi, Amedeo (2012). The Descriptive Phenomenological Psychological Method. Journal of Phenomonological Psychology 43 (2012) 3-12.

Clark, J. & Knight, I. (2017). A humanisation approach for the management of Joint

Hypermobility Syndrome/Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome-Hypermobility Type (JHS/EDS-HT). International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 12:1, 1371993, DOI: 10.1080/17482631.2017.1371993.

Hakim, A., De Wandele, I., O´Callaghan, C., Pocinki, A. & Rowe, P. (2017). Chronic Fatigue in Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome - Hypermobility Type. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C 175C:175-180.

Krahe, A., Adams, R. & Nicholson, L. (2107). Features that exacerbate fatigue severity in joint hyper mobility syndrome/Ehlers-Danlos -hypermobility type. Disability and Rehabilitation August 2018, Vol.40(17), pp.1989-1996.

10.1080/09638288.2017.1323022.

Kvale, Steinar (2007). Doing Interviews. Sage Publications Ltd.

Kielhofner, G. (2008). Model of human occupation: Theory and application (4th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins.

Lexell, E., Iwarsson, S. & Lund M. (2011). Occupational Adaptation in People With Multiple Sclerosis. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health. Vol. 31, No. 3, 2011 127 .

Lyell, M., Simmonds, J., & Deane, J. (2016). A study of UK physiotherapists knowledge and training needs in hypermobility and hypermobility syndrome. Physiotherapy Practice Research, 37(2), 101–109. Doi:10.3233/PPR-160073.

Murray, B., Yashar, B., Uhlmann, W., Clauw, D. & Petty, E. (2013). Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, Hypermobility Type: A Characterization of the Patients` Lived Experience. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A 161A:2981-2988.

Palmer, S., Terry, R., Rimes, K. A., Clark, C., Simmonds, J., & Horwood, J. (2016). Physio-therapy management of joint hypermobility syndrome – a focus group study of patient

and professional perspectives. Physiotherapy, 102(1), 93– 102. Doi:10.1016/j.physio. 2015.05.001.

Rombaut, L., Malfait, F., Cools, A., De Paepe, A. & Calders, P. (2010). Musculeskeletal complaints, physical activity and health-related quality of life among patients with the Ehlers- Danlos syndrome hyper mobility type. Disability and Rehabilitatetation ion, 2010; 32(16): 1339-1345.

Rombaut, L., Malfait, F., De Paepe, A., Rimbaut, S., Verbruggen, G., De Wandele, I. & Calders, P. (2011). Impairnment and Impact of Pain in Female Patients With Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. A Comparative Study With Fibromyalgia and Rheumatoid Arthri-tis. Arthritis & Rheumatism, Vol. 63, No. 7, July 2011, pp 1979-1987.

Schkade, Janette, K. & Schultz, Sally (1992). Occupational Adaptation: Toward a Holistic Approach for Contemporary Practice, Part 1. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, September 1992, Volume 46, Number 9.

Syx, D., De Wandele, I, Rombaut, L. & Malfait, F. (2017). Hypermobility, the Ehlers-Danlos syndromes and chronic pain. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2017; 35 (Suppl. 107): S116-S122.

Terry, R., Palmer, S., Rimes, K., Clark, C., Simmonds, J. & Horwood, J. (2015). Living with joint hyper mobility syndrome: patient experiences of diagnosis, referral and self-care. Family Practice, 2015, Vol.32, No.3, 354-358.

The Ehlers-Danlos Society, 2019. ESD types. Retrieved from https://www.ehlers-danlos.com/.

Tinkle, B., Castori, M., Berglund, B., Cohen, H., Grahame, R., Kafkas, H. & Levy, H. (2017). Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (a.k.a. Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Type III and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome Hypermobile Type): Clinical Description and Natural History. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C (Seminars in Medical Genetics) 175C:48-69.

Voermans, N., Knoop, H., van de Kamp, N., Hamel, B., Bleijenberg, G. & van Engelen, B. (2010). Fatigue is a Frequent and Clinically Relevant Problem in Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. Seminars of Arthritis and Rheumatism. December 2010Volume 40, Issue 3, Pages 267–274.

Voermans, N. & Koop, H. (2011). Both pain and fatigue are important possible determinants of disability in patients with the Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome hypermobility type.

Disability and Rehabilitation, 2011; 33(8): 706-707.

Wilcock, A. & Hocking, C. (2015). An Occupational Perspective of Health. Third Edition. Slack Incorporated.

World Health Organisation (2018). https://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/. Page updated on 2 March 2018.

Appendix 1

Form for Self-Examination of Ethical Issues of Master’s Theses/

Degree Projects at the School of Health and Welfare

2

Degree Projects/Master’s theses at the School of Health and Welfare, Jönköping University, must comply with the ethical principles as expressed in the Swedish Ethical Review Act (EIkprövningsla-gen, “EtRAct”). This form is a tool for reviewing ethical issues related to the degree project./thesis.

Students and academic supervisors carefully go through the form together, iden7fy poten7al et-hical problems, and agree on how these should be dealt with.

Date: 18.6.2018 Title of the

Degree Project/Master’s thesis: OccupaIonal AdaptaIon in in-dividuals with Ehlers-Danlos Hypermobility type: a qualitaI-ve study of personal perspecI-ves

Student(s): Pia Nahi Student(s) e-mail Address:

na-hipia@gmail.com

EducaIonal programme: Mas-ter Degree of OccupaIonal The-rapy

Level of the educaIonal

pro-gramme:60 credits Academic supervisor: Elisabeth

Elgmark

Academic supervisor’s e-mail address:

elisabeth.elgmark@ju.se

The form also applies to improvement measures relaIng to operaIng pracIces in healthcare and social welfa

2

Research that falls within the EtRAct must be reviewed by a regional Ethical Review Board (“ERB”) . There are two types of studies that usually are not considered as research, and which must be dealt with specially. One is theses and the other is improvement measures relaIng to operaIng pracIces in healthcare and social welfare.

The disIncIon and boundary between research and these two types of studies is iniIally touched on in Part A.

Part B deals with what falls under the EtRAct and the ethical principles that are relevant with the conducIng of the study.

Part C contains procedures for obtaining an advisory opinion from the University’s Research Ethics Commi_ee.

If the degree project is already included in a project that has been reviewed and approved, it is not necessary to conduct a Self-ExaminaIon of Ethical Issues.

Part A:

Is this a research study?

The purpose of the quesIons in Part A is to determine if the intended study is to be regarded as re-search. A Master’s thesis is not ordinarily considered research and thus can not be dealt with in an ERB. Under certain circumstances however, a Master’s thesis project may be research, namely it:

1. the intenIon is to seek to publish it in a scienIfic journal

2. has a scienIfic issue/hypotheIcal and a design that can answer that scienIfic issue/hy-potheIcal

3. is led by researchers within the discipline, either as part of a larger project or with a re-searcher as the academic supervisor.

All of these three must be fulfilled for the study to be considered research and be able to be dealt with in an ERB.

Is the study research in these three respects?

YES (The study needs to be reviewed by an ERB.) NO (Proceed to Parts B and C.) x

Part B:

Does the degree project contain what is regarded as being

et-hically sensitive according to the Swedish Ethical Review Act?

The purpose of the quesIons in Part B to explore whether the degree project contains anything that may be idenIfied as being an ethical issue which if it were research, a review in an ERB would be required, as well as to assess how ethical principles are dealt with.

Yes sureNot No

www.epn.se/en/start/

1 Does the study intend collect and process personal data that according to the privacy protecIon provisions in the Swedish Personal Data Act is con-sidered to be sensiIve personal data, i.e., data that at some stage can be linked to a person and where the data reveals racial or ethnic origin, poli-Ical opinions, religious or philosophical beliefs, union membership, health or sex life?

x

2 Does the study intend to collect and process personal data relaIng to vio-laIons of the law that involve a criminal offence, convicIon in a criminal proceeding, criminal prosecuIon relaIng to coercive measures or an ad-ministraIve custodial sentence/deprivaIon of liberty?

x 3 Does the study entail a physical intervenIon with on in research subjects

(even that which is included in standard procedures, but also part of the research)?

x 4 Is the purpose of the study to physically or psychologically affect the

re-search subjects (for example, treatment for obesity)? x

5 Does the study have a component with a clear risk of adverse effects (4, §2 2003:460) (for example, the risk of physical harm or the risk of awake-ning traumaIc memories)?

x 6 Is biological material that can be traced to an idenIfiable individual or

deceased person going to be used (e.g., blood samples or Issue speci-mens)?

x 7 Can voluntariness be quesIoned (e.g. a member of a vulnerable group

such as children, people with cogniIve impairment or mental disabiliIes, or individuals in a dependent relaIonship to the principle invesIgator such as a paIent or student)?

x

Yes Not sure No

8 Will individuals with limited autonomy (for instance individuals with cogni-Ive difficulIes, minors), where the understanding of the meaning of the consent is limited, be involved?

x 9 It is intended that informed consent will not be obtained as a part of the

study (in other words, the research subjects will not receive full informa-Ion about the survey or research and/or the opportunity to opt out from parIcipaIon?

x

Risks

10 Other idenIfied risks. x

Selec7on of par7cipants and social vulnerability

11 The parIcipants belong to a parIcularly vulnerable or disadvantaged

group in the society (a minority group). x

12 Will a personal register where data can be linked to a physical person be

If any of the quesIons 1-12 are answered Yes or Not sure, the study must be reviewed by the Univer-sity’s Research Ethics Commi_ee, see Part C.

If any of the quesIons 13-21 are answered No or Not sure, the study must be reviewed by the Uni-versity’s Research Ethics Commi_ee, see Part C.

Informed consent

13 The study described in such a manner so that the parIcipants understand its purposes and structure, and what parIcipaIon in the project entails (e.g. number of visits, duraIon of the project, and wri_en in easy to un-derstand Swedish without technical terms or professional jargon).

x 14 All factors that may influence the decision to parIcipate or not are clearly

stated. x

15 The informaIon le_er does not contain persuasive formulaIons, including “mildly persuasive” which assumes that the person must or should par-Icipate without showing full respect for the choice (for example, “thanks in advance”).

x 16 It made clear that that care or other services/efforts are not affected by a

decision to parIcipate or to refrain from parIcipaIon. x

Voluntariness

17

The parIcipaIon in the study is enIrely voluntary and this is clearly stated in the wri_en informaIon provided to the paIent or research subject. x 18 It is clearly stated that parIcipants may disconInue the parIcipaIon at

any Ime and without the need to state any reason, without prejudice to the research subject’s being offered care or treatment or, if relaIng to a student, it affecIng their grades or related ma_ers.

x

Confiden7ality and the security of the par7cipants

19 Are there reasons to promise confidenIality with parIcipaIon in the

stu-dy? x

20 There are procedures in place to ensure the confidenIality and the

integri-ty of the collecIon of data collecIon. x

21 If confidenIality is promised, the results/findings are described in such a manner so that the parIcipant’s idenIty remains confidenIal, meaning that they can not be idenIfied alerwards (including a minimal potenIal for reverse idenIficaIon).

x

Research results and/or findings

22 Are there reasons to offer parIcipants the opportunity to obtain a copy of or otherwise gain access to the research results/findings? x

Part C:

Application for an Advisory Opinion

Follow the instructions in the point list. The application must be written under supervision and signed by the student(s) and academic supervisor(s). The text may not exceed 1,000 words (Times New Ro-man, 12 pt., 1.5 line spacing).

• Describe the project, including background, purpose, research issue and methodology.

• Describe the ethical problems that may arise in connection with the study.

• Describe and explain the risks that participation may have for the research subjects (ERB 5:1).

• Describe and explain the potential benefits for the research subjects participating in the degree project (ERB 5:2).

• Identify and specify in detail any ethical problems that may arise in a wider perspective via the degree project (ERB 5:4).

• Describe and explain how ethical risks and problems will be addressed.

Sign the “Self-Examination of Ethical Issues” form and send it in hard-copy format along with the answers to the questions in Part C to the University’s Research Ethics Committee’s secretary. Additio-nally, send all documents to the secretary also in electronic form. Forskningsetiska The dates for mee-tings of the Research Ethics Committee can be found on the University’s website .

The above questions have been carefully reviewed, truthfully answered, and discussed with the aca-demic supervisor(s).

Place and date: 18.6.2018

Printed name Signature

Student/implemen-ter: Pia Nahi

Student/implemen-ter:

Student/implemen-ter:

Appendix 2

Hi,

I looked at Pia Nahi's Pro Gradu plan and accept it as it is.

Best Regards,

Jenna Kärpänen puheenjohtaja

Suomen Ehlers-Danlos -yhdistys ry (Sedy)

Appendix 3 INFORMATION FOR PATIENT ORGANIZATION

Dear member of Suomen Ehlers-Danlos Yhdistys (SEDY) or a participant of the association or peer group,

I am inviting people to participate to a qualitative research related the performance of Ehlers-Danlos hyper mobility type (hEDS) in their everyday life. The purpose of the study is to get subjective information how pain and fatigue are affecting performance, daily routine, occupa-tional choices and environment of individual with hEDS. I hope to find people who have been diagnosed (Q79.6) in accordance only with the new 2017 criteria.

Participation is voluntary and can be withdraw at any time without providing any explanation. I deal with all the interview material confidentially and the respondents can not be identified from the results of the study. Everything will be printed on group level. I will send a separate information letter and a written approval form to the participants.

I am working with thesis related to my Master's Degree of Occupational Therapy in Jönköping University. I am glad to offer you an opportunity to obtain a copy of the results, and be invited to present the results of the study in some convenient event after completing it. Kindly, Pia Nahi Occupational therapist nahipia@gmail.com Elisabeth Elgmark, PhD Associate professor

University Lecturer on Occupational Therapy

elisabeth.elgmark@ju.se

Appendix 4

PARTICIPANTS INFORMATION

Dear participant,

Ehlers-Danlos hyper mobile syndrome (hEDS) is a connective tissue disease associated with hyper mobile joints, and skin and connective tissue elasticity. The symptoms may be pain, fa-tigue and generally impaired quality of life and performance in everyday activities.

Ehlers-Danlos hyper mobility syndrome has not always been recognized and has not necessar-ily been taken into account comprehensively in rehabilitation processes. Understanding his or her own situation and managing daily life may be difficult for also a person him or herself. Generally, little is known about the effect of connective tissue disease on the performance ca-pacity.

Occupational therapy is a form of rehabilitation that supports individual's performance in his or her own daily life. Occupational balance is one of the key concepts in occupational therapy. It can be understood as a personal experience of how work, leisure, self-care and rest are dis-tributed in an appropriate proportion to the individual.

The purpose of this interview is to obtain vital information about individual's everyday life, and how hEDS affects his or her functional ability. With the information provided, rehabilita-tion can be better targeted.

The interview takes proximately for an hour and there is no cost. Participation is voluntary and can be withdraw at any time without providing any explanation and without any further consequences. The interview can be arranged in a suitable environment for you. It could be possible also via Skype. Interview will be recorded for the transcription and analysis. The in-terview will be published on group level and individuals will not be identified from the re-sults. I will deal with the collected information, recorded interviews and research results with confidentiality, as required in the Personal Data Act

(22.4.1999/523).

If you have questions about the study, please contact me,

Kindly, Pia Nahi

Occupational therapist

nahipia@gmail.com

Associate professor

University Lecturer on Occupational Therapy

elisabeth.elgmark@ju.se

Appendix 5

CONSENT TO TAKE PART TO THE STUDY

The name of the study:

Occupational Adaptation with Ehlers-Danlos Hypermobility Type

I have been asked to take part in an interview, which is related to perform of daily life of Ehlers-Danlos Hypermobility Type. I have also an opportunity to be obtained a copy and take part of the results of the study.

I have received information of the study and I am familiar with it. I have had an opportunity to ask for information and I have got answers to my questions. I will get more information about the study if needed from a contact details as are in the information letter.

I will participate in this study voluntarily. I am conscious of possibility to interrupt my partic-ipation any time without any reason and without any further consequences. I can also cancel my approval and all the information considering me shall not be used in this study.

I understand that all the collected information, such as recordings, are confidential and are not given to a third party. I agree to my interview being audio-recorded. The research reports do not reveal my identity. This will be done by changing my name and disguising any details of my interview which may reveal my identity. I understand the disguised extracts from my in-terview may be quoted in dissertation.

When this thesis is completed, all the collected information will be saved in the locked safe place. Pia Nahi takes all the responsibility for the information considering me and keep it safe with confidentiality.

I confirm participating on this study by my signature

_________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________