PAOLO GUIDI

SOCIAL WORK ASSESSMENT

OF FAMILIES WITH CHILDREN

AT RISK

Similarities and Differences in Italian and Swedish Public

Social Services

MALMÖ UNIVERSIT Y HEAL TH AND SOCIET Y DOCT OR AL DISSERT A TION 20 1 6:9 P A OL O GUIDI MALMÖ UNIVERSIT SOCIAL W ORK ASSESSMENT OF F AMILIES WITH C HILDREN A T RISKMalmö University

Health and Society Doctoral Dissertation 2016:9

© Copyright Paolo Guidi 2016 Cover image: Paolo Guidi ISBN 978-91-7104-734-2 (print) ISBN 978-91-7104-735-9 (pdf) ISSN 1653-5383

PAOLO GUIDI

SOCIAL WORK ASSESSMENT

OF FAMILIES WITH CHILDREN

AT RISK

Similarities and Differences in Italian and Swedish Public

Social Services

Malmö University, 2016

Faculty of Health and Society

Publikationen finns även elektroniskt, se www.mah.se/muep

CONTENTS

LIST OF PUBLICATIONS ... 9

INTRODUCTION ... 11

RESEARCH PROBLEM ... 14

AIM ... 17

Social Work Assessment: terms and definition ... 18

STATE OF THE ART – LITERATURE REVIEW ... 21

THE WELFARE STATE AND CHILD PROTECTION SYSTEMS ... 25

The Swedish Welfare State ... 27

The Swedish child protection system ... 30

The Italian Welfare State ... 32

The Italian child protection system ... 34

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK ... 37

RESEARCH METHODS ... 41

The qualitative part ... 42

The vignette-study ... 42

Focus groups ... 44

Semi-structured interviews ... 45

The research environment ... 45

The choice of the research units ... 46

The choice of the informants ... 48

The research process ... 49

The quantitative part ... 55

The sample ... 55

Reflections about the methods ... 57

Strengths and limitations ... 57

ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS ... 59 RESULTS ... 60 Study I ... 60 Study II ... 62 Study III ... 63 Study IV ... 63

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION ... 65

Results discussion... 65

Common core knowledge in social work assessment with some particularities ... 65

Social workers’ position: the influence of law and regulations ... 67

Assessment formalisation: a cross-national trend? ... 68

Reflections on the meaning and potential of the comparative approach from the perspective of this study ... 71

POPULÄRVETENSKAPLIG SAMMANFATTNING ... 72

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... 74

BIBLIOGRAPHY ... 76

LIST OF PUBLICATIONS

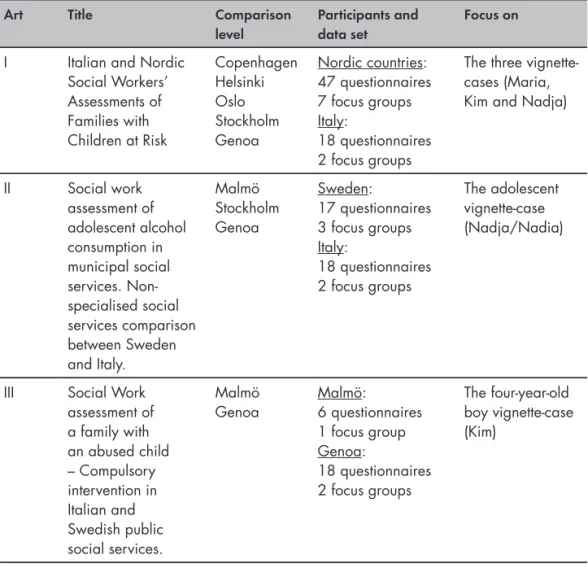

The thesis consists of a summary and four studies. These are referred to the Roman numerals below:

I ‘Italian and Nordic social workers’ assessment of families with children at risk’. (Paolo Guidi, Anna Meeuwisse and Roberto Scaramuzzino).

Nordic Social Work Research, 2016, vol. 61(1), pp. 9-21. doi:

10.1080/2156857X.2015.1099052

This article contextualises the comparison between Italy and the Nordic countries. Italian and Nordic Welfare models are presented and evidence of professional assessments are analysed and compared, with particular relevance given to the Italian data.

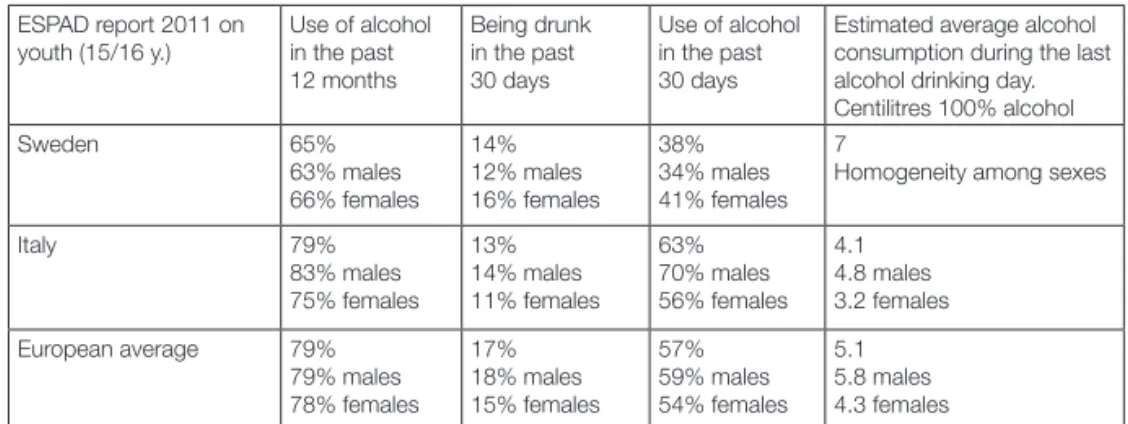

II ‘Social work assessment of underage alcohol consumption – Non-specialised Social Services comparison between Sweden and Italy’. (Paolo Guidi and Matteo Di Placido)

Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 2015, vol. 32 (2), pp. 199-218. doi:

10.1515/nsad-2015-0020.

This is an in-depth study of the case of Nadja, an adolescent who is acting-out, with particular reference to her excessive alcohol consumption. The paper focuses on and discusses the influence of recognised alcohol-consumption cultural patterns on social workers’ assessments.

III ‘Social Work assessment of a family with an abused child – Compulsory intervention in Italian and Swedish public social services’. (Paolo Guidi).

The third article deals with the vignette of Kim, a four year-old abused child and his family. Results of the vignette research are analysed considering different protective practices and networks in Sweden and Italy, enhancing their influence on social work assessment.

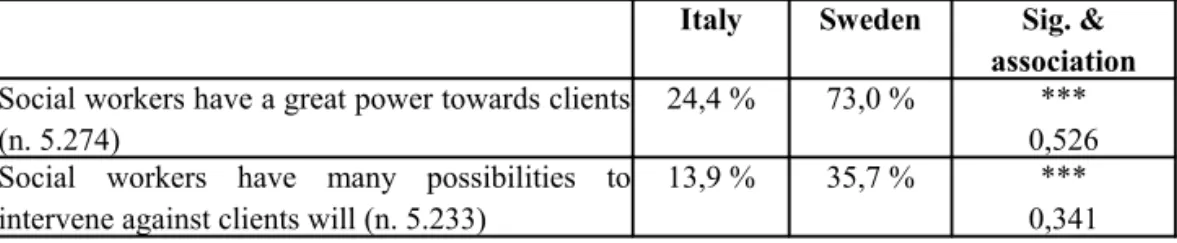

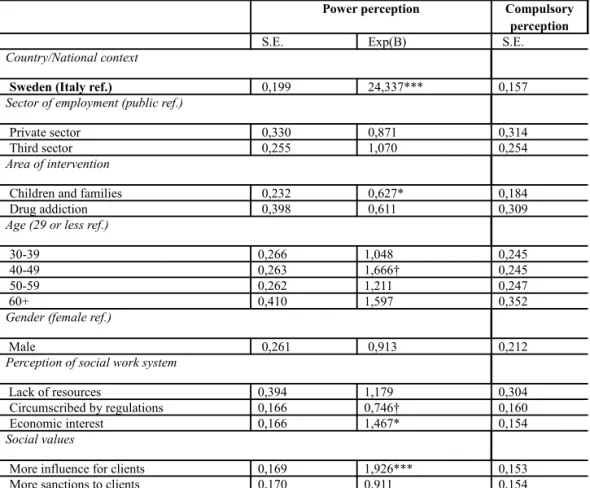

IV ‘Italian and Swedish social workers’ perceptions of power - Between welfare and child protection systems, professional mandate and clients’. (Paolo Guidi and Roberto Scaramuzzino)

Submitted to the Journal of Social Work, April 2016, manuscript JSW-16-0037; under review.

The fourth article enhances the theme of social workers’ self-perception of power in relation to clients, in particular in relation to child welfare and protective services. The data was collected through two broad national surveys that consent to contextualise this issue in the present work.

INTRODUCTION

As a front-line social worker at the Municipality of Genoa, and a lecturer in social work at the University of Genoa, the theme of the present study is strongly related to my experience. Throughout my nine years teaching social work at the University of Genoa and twelve years supporting families and children as a frontline social worker at the Municipality of Genoa, my colleagues and I have constantly struggled with doing the best for our clients in complex and uncertain situations. This has entailed the difficulty of choosing the right path, whilst maintaining an ethical stance between institutional demands and clients’ needs.

In Sweden and Italy, the intrusion into the family sphere by social services is justified and normalised by the national welfare systems and the perceived right of vulnerable people to be helped and protected. From my experience, professional competence needs to be combined with a genuine interest in people’s lives and well-being, who are frequently among the most disadvantaged in the society. Therefore, the relationship the professional builds with the client, however unbalanced by nature, has to be respectful and oriented in ethical principles. This is particularly true when the assessment of a clients’ case takes place in settings where both measures of support and monitoring are implemented, including compulsory

procedures

.

As Beckett has clearly stated (2010: 2) in her handbook for social work students engaged in their training period, social workers ‘intrude in the personal area of life, into family relationships, into people’s homes’. Social work can be an unwelcome and sometimes bossy guest, not only offering, but sometimes even imposing alternatives to the informal networks of family and neighbourhood’. The presence of potential conflicting interests around social services’ assessments and interventions capture the public debate and tensions.

The role of assessment in social work, is challenged at the present time, on the one hand, by the widespread use of rigid formal assessment tools and, on the other,

by the maintenance of blind trust and a disinterested mandate in the professional’s ability of understanding social situations. The problem of knowledge is recurrent in social work and the assessment process catalyses this major issue, as from it stems any successive course of action and intervention. The request for knowledge in assessment practices implemented in social services are, as regards the whole social work process, increasingly oriented towards the necessity of gathering and monitoring information, and accounting for decisions. Thus, they are less concerned with discursive knowledge and social dimensions (Parton, 2008: 254). Every family’s case presents limits and resources related to their living situation. These situations need to be formally assessed in order to implement interventions and to achieve, as far as possible, individual and family well-being. This situational knowledge is negotiated through the relationships that the families share with the social workers. This is then contextualised in a broader context, represented by the national and local welfare systems whose aim is to promote citizens’ well-being.

Therefore, due to my experience from the field, I recognise the importance of highlighting the contexts and cultural associations that social workers may be influenced by when conducting an assessment. By comparing two different systems, we can gain a greater awareness of how they influence practitioners and how it effects the quality of care.

The possibility of comparing social work practices in different countries, gaining distance from the field work, enables us to gain an enhanced reflection on both the practices and the systems. Hetherington (2002), in the introduction of her valuable paper on comparisons of child welfare systems, asserts that we can learn from the differences:

‘By studying the ways in which other countries deal with similar problems, we can learn about new ways of responding and may find ideas that we can adapt for use in our own context. But we can do much more than this. By looking at differences, and using the power of making comparisons, we can begin to understand more about our own system and why it has developed as it has. We can begin to identify the “taken-for-granted”. This may lead us to question some of the assumptions on which our system rests and to become more aware of the aspects of our system that we value most highly. As we become more aware of the reasons why our system has developed as it has, positive changes may become more attainable (Hetherington, 2002: 1).

The main contribution of this thesis is to shed light on social work assessment processes practiced in Sweden and Italy from a comparative perspective, highlighting possible contextual (cultural, organisational and institutional) influencing factors.

Hetherington considers the possibility of learning from differences through the comparison of child welfare systems of high value. Though recent studies (Gilbert, Parton and Skivenes, 2011) stress the converging trends of family and child welfare systems among European countries, differences are still present and ‘aspects...[of our own system]...that we had assumed to be necessary and normal might not exist at all in other countries’ (Hetherington, 2002: 8).

RESEARCH PROBLEM

The assessment is a fundamental part of social work. Competence in social work assessment distinguishes the effective professionalism of a group of workers that, through relationships and interventions, contribute to help, sustain and ameliorate citizens’ lives. The assessment also determines the next course of action.

From the outset of social work as practice, during the transition from charity and voluntarism to a real profession, the assessment was the main activity that enabled this shift. The assessment was considered central and referred to as the only paid activity of the whole help process:

‘Richmond [1900] explained the work of the Charity Organisation Societies in terms of five strategies that reflected the society’s principles and aims: cooperation, investigation, registration, friendly visiting and constructive work...[...]... Investigation [assessment] by paid agents sought to determine the circumstances of individuals who applied or who were referred to the COS, and thus to determine how best to assist them…’ (Agnew, 2004: 64).

Nowadays, this issue has also become situated in the public domain and is reflected in the fervent and controversial debate on the impact and consequences that social workers’ decisions and interventions produce in families’ lives, in particular, in cases of children and youth at risk. The central focus today is on ‘improving the assessment practice [and] has thus become an important part of the social work agenda’ (Taylor and White, 2006: 938).

Furthermore, it is necessary to consider that the role of assessment in social work has been increasingly integrated into the institutional domain of welfare states, where social workers are acting as civil servants. Social workers are considered public officials, as they represent the interface between citizens’ requests and needs, and the delivery of public support and service provision. This positioning implies responsibility, discretion and power, and has relevant consequences on the relationship between families and social workers. In both Sweden and Italy,

social workers are mostly employed in the public sector. The field of social work acts within different family welfare systems and operates under national rules, local regulations and organisational contexts that inform and affect the practice. Thus, the client-social worker relationship is also related to how citizens view their rights towards their state-community and how social workers consider their intermediary role. This highlights the mutual interplay between the individual case and the welfare system. At the same time, this stresses the research interest placed here on comparing on the one hand, social work assessment practices in two different national welfare systems, while at the same time, eliciting social workers’ opinions on their role in relation to power toward clients. Social workers, under certain conditions related to risk or abuse, can impose compulsory measures to protect children. The awareness of this potential power informs social workers’ relationships with families; therefore, a part of this study is devoted to understanding social workers’ opinions on their own power in relation to clients.

The study originates from a broad research project carried out in the Nordic countries (Blomberg et al., 2012) and develops along the lines of a cross-national comparison between Italy and Sweden, taking into particular consideration the cities of Malmö and Genoa.

The thesis is structured around the assumption that the practice of social work assessment of families and children in public social services is consistent with the family welfare systems assumed by the respective countries. In other words, the method for performing assessments within social work needs to be contextualised by its own environment, in relation to other factors that have to be detected at different levels and contribute to shape the specific task.

To highlight how welfare models and other possible welfare-related features influence the assessment at the level of practice, this work adopts a cross-national comparative approach informed by ‘most different logic’ (Blomberg, 2008). The two countries considered present significant differences in their welfare state systems, as shown in the literature: Sweden is included in the Social Democratic welfare regime with family orientation grounded on public service delivery, while Italy’s system is representative of a conservative welfare regime, typical of continental European countries characterised by subsidiarity (Hetherington, 2002: 29).

We have to consider that social workers’ assessment is located in a public arena where, with different emphasis according to country, the role of the state in relation to families is at the centre of public debate. The reaction of the public, which is also reflected in the media, oscillates between expecting high standards from social workers in safeguarding children, and on the other hand, presenting

public social services as child-thieves (Cirillo and Cipolloni, 1994). Although this conflict needs to be contextualised within each country, the social tension represented in these opposing positions constantly affects the relationship among social workers, families and society.

Social services’ compulsory interventions, as a result of assessments of family cases, are often highlighted in the public debate. This emphasis and the related general public criticism have often been used by policy makers and institutions as reasons to advocate for more control on professionals’ capabilities, such as introducing standardised assessment tools and verified procedures, aiming to avoid, in a mechanistic way, further errors.

There is an expectation on social workers to assess cases from a professional perspective, as official acts that have relevant impacts on families’ lives. However, social work assessments and decision making processes are also affected by the human relationship between the client and the social worker. If we can argue that there are certain levels of uniformity in professional judgment, we need to recognise that many factors can influence social workers’ assessments. Some of these variations that can characterise the assessment, not addressed in the present research, can be related to the client-social worker dyad, mirrored by the personal/ professional context of the social worker (e.g. personal experience, professional expertise and values), and of the client (e.g. life experience, problem types, resources, opinion on social workers, expectations). Others factors influencing the assessment can come from a local organisational level, an institutional level or cultural norms, such as cultural understanding of social phenomena (i. e. adolescent alcohol consumption, role of the family in the society).

I argue that shedding a light on the complexity of social work in child and family services, where the assessment has a central place, can improve professional awareness and correctly orient assessment practices and interventions for clients, enhancing their well-being and at the same time reducing the exposure of children to maltreatment.

AIM

The aim of the thesis is to increase the understanding of social work assessments of families and children implemented by social workers employed in public social services, with special reference to cases of children and youth at risk. Specifically, it aims to detect similarities and differences in the social work assessment of family situations that professionals carry out in public social services in Sweden and Italy, in particular in the cities of Malmö and Genoa.

The assessment is explored, taking into consideration the position of responsibility assumed by professionals in managing contexts that present potential risks for children and youths. The focus of this study originates from a social worker’s perspective on their working environment and the national context, in relation to social policy, in which they operate. Through this, the study tries to detect the main tendencies of social workers and factors that influence their work.

The research questions are:

1. How do social workers assess and think about the family situation of children at risk in Sweden and Italy?

2. Which are the major differences and similarities in the assessment practice in Sweden and Italy?

3. How do Swedish and Italian social workers perceive their power toward clients?

4. How can such similarities and differences be explained?

The first three questions are descriptive. Questions one and two are based on a circumscribed qualitative study on social work assessment; through the second research question I attempt to compare the systems of Sweden and Italy, from

individual social worker’s perspectives founded on a national survey. The third question is focused on social workers’ self-perception of power towards clients’ in their welfare ‘environment’, reflecting on how Italian and Swedish social workers represent themselves in their own welfare arena. The fourth question aims to depict possible explanations of the results.

The data collected through the qualitative research and surveys enhances the social worker’s individual point of view (at the level of practice) in relation to the organisation and the institutional level, represented by the welfare systems and their norms and cultural orientations. This multi-level conceptual framework enables a comparison of the practice of social work assessment and the positioning of professionals in their own welfare systems from a critical perspective, depicting potential influencing factors that higher governmental agencies may produce in the assessment practice.

Social Work Assessment: terms and definition

The object of the present research is social work assessment; but what do we actually mean by this term? Prior to going deeper into the analysis, it is important to consider some lexical and cultural common understandings and uses of the term, in particular, with reference to the English dictionary and the Swedish and Italian terms used in literature and in social work practice.

The term ‘assessment’ in English identifies a practice of evaluation; every situation or phenomenon that needs to be understood requires an assessment, but an assessment is something more than a ‘simple’ evaluation done in everyday life.

The term assessment is often used in reference to the investigation of something unknown and is performed by a professional expected to be qualified and to possess specific knowledge. In fact, preparing future practitioners to conduct professional assessments, is a common practice in many professions. In this research, I specifically refer to assessments executed by social workers in the context of public institutions regarding, in particular, families and children.

The social work assessment can be defined as a pre-mediatory measure, in case of the need of future action, which involves information collection and the analysis of a family’s case by a social worker, followed by a sound decision (Merlini, Bertotti and Filippini, 2007). This definition reveals the procedural nature of assessments and its orientation to action: collection, analysis, attribution of meaning, and decision, is coherent with the general social work methodological approach to problems and situations.

This PhD project will draw on the above mentioned definition. In the literature, other definitions are present that are related to the approach of the researcher or the theoretical framework used. Of particular value, though not addressed in this paper, is the contribution of scholars (Holland, 2000; Keddell, 2011) that highlight the relational nature of the assessment and the attribution of meaning that words assume in the concrete interaction between social workers and families. According to Spratt (2001) the concept of assessment is intrinsically embedded in the care/control function of social work. The duality of the assessment’s function lies both in risks and needs, as social workers need information sifted and weighted; views of others are acquired and the past is weighted for future developments, encroaching on the family’s privacy, with the possibility that a spontaneous request for help turns out to shape a negative assessment with potentially authoritative decisions against the parents’ will.

The term assessment is frequently used in social work literature and practice: however, the terms ‘judgement’, ‘investigation’, and ‘evaluation’ can also be found. They describe concepts closer to and overlapping with the term ‘assessment’. Moreover, the term ‘decision making’ can also be found as synonymous when the focus is more oriented to the procedural dimension of assessment. ‘Judgment’ is relatively seldom found as a term in the literature. It refers to the legal framework in which the assessment is placed. The term ’investigation’ emphasises the authoritative nature of actions taken by social services in relation to suspected child maltreatment or abuse, and is for instance consistent with an authoritative approach. The term ‘evaluation’ is broader and more general, and refers to many types of evaluation, i.e. of social policies, process outcomes, and clients’ satisfaction.

Within the Italian social work environment, the English term is rarely used.

Valutazione is the Italian term used to identify the assessment in social work.

Etymologically the word valutazione is generic and comes from the latino valuto, which means evaluate, i.e. to give an opinion or attribute value to something. The former term diagnosi sociale (social diagnosis), presented in some Italian manuals (cfr.: Lerma, 1992; Cesaroni, Lussu and Rovai, 2000), is derived from the medical approach, but has been gradually abandoned in professional language.

In order to stress the authoritative mandate of the practice of assessment in public social services, when referring, for instance, to the judicial part of the system, the term indagine sociale (closer to the English term investigation) is also used.

In Swedish the term used is bedömning. This has to be considered in light of what is stated in the Assessment Framework ruled by the National Board Manual - Children’s needs at the center (2006) that divides the process into three phases, described below:

The utredning is based on information collected during the investigation, which focuses on the child or young person’s needs, the parents’ ability to meet these needs in the family, and important factors in the family environment. In the analysis different explanations should be tested to assess the various possible causes of the problems identified.

The bedömning, then, involves determining whether the child or youth is in need of protection or support from social services to meet their needs.

The beslutsfattande represents the final decision on whether the child, youth, or the family need protection or support from social services (Rasmusson, 2009).

STATE OF THE ART – LITERATURE REVIEW

A review of the literature on assessment reveals that Sweden is often considered in social work/child protection comparative studies, whereas the Italian method is not often cited. In particular there are, until now, no studies that directly compare Swedish and Italian social work assessment. Most of the studies done so far have focused on comparisons between other countries (sometimes including Sweden). The selection of studies offered here mainly aims to provide a review of the state of the art research in relation to assessment in different national and international contexts. My presentation is chronological, starting with a Norwegian study from 1995.

‘Decision making process’ and ‘committal to care’ were the key words for the research that Backe-Hansen (1995) implemented in nineteen of the twenty-five social work departments existing in Oslo at the time. The study considers all children aged 0 – 7 years committed to care during one year. The author highlights the main reasons for assessing committal to care; they were in particular related to parents’ characteristics, presence of substance abuse and psychiatric illness. At the same time, it was evident that the children were almost invisible in the whole process. The study also highlights the discourse on crisis as a mediator for social work intervention. This supports the high level of intervention proposed by many practitioners in the present study in the case of to the vignette of the 4-year-old boy. The crisis in this vignette is related to evidence of violence towards the boy. Backe-Hansen argues that when there is urgency or a need for an immediate decision in a family’s case, ‘it becomes obvious to “everybody” that action is necessary or even imperative’ (1995: 412). Backe-Hansen (2004) offers an important contribution through further research, which sheds a light on factors influencing the decision- making process in child assessments at level of practice.

Sally Holland’s (2000) study on comprehensive assessment of parenting is valuable as it focuses on the relationship between social workers and families, in particular, parents. The study was conducted in two social work agencies in England. The comprehensive assessment, as defined by the Department of Health (1998), is usually carried out after initial child protection proceedings, such as investigation and registration, have been completed and is related to further care interventions. It is the basis of a significant decision, for example, whether a child should be removed from a home or, if a child is in care, whether she or he should return home or be placed permanently elsewhere. The results point out that the assessment tends to be verbally based and to be centred on parents’ performance in an interview. Factors such as co-operation, a positive relationship with social workers and a plausible explanation for the family’s situation becomes relevant in the assessment discourse. Additionally, the pressure on women to bear responsibility for child protection as a cultural frame for social work assessment stands out from the research. Finally, a correct assessment includes a systematic and reflexive analysis of both the information gathered and the process of assessment itself and a central role for the child’s needs and perspective on life.

Research comparing Swedish and Canadian child protection systems in two municipalities: Barrie, Ontario region, and Umeå (Khoo, Hyvönen and Nygren, 2002), through focus group discussions, provides some relevant results: Swedish social workers intervene earlier and with more resources and measures, interventions are assessment-driven and consider the integrity of the family, whereas Canadians intervene only in the cases of the most vulnerable children and are more narrowly focused on protection. The main topics discussed in the group were collected by scholars under labels: gate-keeping, skills and contexts, client identity, decision points, compulsion and measures. The research, lead by an institutional ethnographic approach, displays the discussions on assessment models/tools in both groups of practitioners; in particular in Canada, where practitioners are assisted at the time of referral with a specific tool (Eligibility Spectrum) in making consistent and proper decisions in relation to service intervention.

The research (Williams and Soydan, 2005) implemented between 1998 and 2002 in a number of cities in Denmark, Germany, Sweden, Texas and United Kingdom uses the vignette to elicit similarities and differences in the approach to ethnicity, testing social workers’ responses to cultural difference. The vignette is also used in the present research and presents the most severe case of the three, the story of an abused child. It is interesting to stress, again, how cultural understanding, in this

case of the child’s ethnicity, can influence the assessment. Despite differences in national legislation and professional practice, however, the Williams and Soydan study shows that a child’s ethnic identity has little significance to social workers in the five countries considered, confirming a largely multi-cultural approach in social work.

An interesting study with a comparative view on some Nordic countries was published by Turid Vogt Grinde in 2007. The research highlighted variations in child protection practice in Denmark, Iceland and Norway: social workers were presented with five vignettes that focused on the dividing line between preventive provisions and out-of-home care. After completing the vignette answers, participants took part in group discussions with colleagues. Results showed variations in arguments, decisions and the use of a compulsory working approach that reflected national views and priorities. The author was aware of the fact that an alternative approach to the topic would accentuate the similarities between Nordic Child care services, maintaining that there is merit in highlighting differences and nuances in Nordic traditions, values and attitudes: ‘The variations are thought to reflect the practical solutions and resources available to child care services as well as national attitudes and traditions’ (2007: 56). In particular, the norms and values related to parental rights versus the best interest of the child were considered. The research points to the idea that social workers are a part of their culture and that their values and thinking are influenced by their country’s culture. The study also highlights that compulsory interventions in social work require the mandate of authority that can differ among countries.

Another important reference for this study is represented by the research comparing assessment processes in Sweden and Croatia (Brunnberg and Pecnik, 2007). Again the vignette used is that of the maltreated four-year-old boy. The analysis of the assessment implemented in nineteen social welfare centres in Croatia and fifteen in Sweden, collecting a sum of 159 questionnaires (87 in Croatia and 72 in Sweden), is oriented to detect: the risk assessment, the perception of the main problem, the tolerance of corporal punishment, and the suggested interventions.

Results shows that Swedish social workers are more in favour of keeping the child at home with the support of social services, whilst the Croatian social workers are more oriented towards removing the child from the home by means of a care order. The value of this study is that it demonstrates the importance of contextualising assessments in each child protection system. The removal of the child is presented as a last resort in both countries. In Sweden, however, this last

option is preceded by a wide range of family support services that are absent in Croatia, where social workers have at their disposal only the guidance of parental care as intervention. These results support the general hypothesis that the broad availability of family support services for some family cases can influence the course of events and prevent the child’s removal.

Ostberg’s follow-up research (2014) on decision-making of child welfare cases in Sweden proposes a valuable view on factors influencing the social work assessment. This research considers the assessment practice as part of a sorting process (funnel), where social workers have a gate-keeping discretional function in order to detect eligible cases for social work provisions. This orientation is consistent with the role of the social worker as the one who interprets social policy with a relatively high level of discretion. For the purpose of the present work, it is interesting to stress that the data regarding 260 children collected in 2003 in two Swedish municipal welfare agencies, point out that only a limited quota of the initially reported cases receive interventions. Results show that social workers, in order to cope with high work pressure, tend to use discretion as an instrument to control access to public resources, favouring certain types of clients and not others, and emphasising documentation and control rather than a long-term perspective of support. These results present a possible contradiction between rules at the national level and the local interpretation of the preventive and family oriented Swedish welfare system. The author stresses the risk that ‘the institutional conditions of child welfare in combination with restricted resources lead to discretion being used to keep clients away from the social worker instead of working close together with them’ (Ostberg, 2014: 74).

The study (Blomberg, Kroll and Meeuwisse, 2012) from which the present research originates is a comparison at the level of assessment practice among Nordic countries. The study focuses on child welfare units in the four Nordic capital areas: Copenhagen, Helsinki, Oslo and Stockholm (see also: Blomberg et al., 2010). The research, based on a questionnaire with three vignettes, confirms the assumption of a preventive and family oriented Nordic child welfare system, especially when it concerns small children, but similarities decline in the adolescent case. In the last case, the vignette describes a young girl with possible alcohol consumption problems that appears to be less related to the common assessment theoretical knowledge base and also to protective arguments. This Nordic research inspired the present doctoral thesis.

THE WELFARE STATE AND CHILD

PROTECTION SYSTEMS

Studies on welfare regimes and models report significant differences among countries regarding policies and standards in providing services and support measures to citizens. States are engaged in the duty of satisfying the fundamental needs of their citizens (including health, education and safety) to prevent suffering, encourage well-being and protect disadvantaged groups in order to ensure social cohesion and progress.

This is, however, done in different ways. In fact, welfare systems in Europe present particularities related to their own origins and further developments. In recent years the welfare debate in Europe has been challenged by the international economic recession, as well as migration with diverse perspectives and possibilities. Child protection can be identified as a system of interventions with rules, practices and processes that are integrated into every family welfare system, which aims to protect children from neglect when a minimum level of care is not guaranteed or in case of abuse and maltreatment.

In this chapter, I intend to briefly introduce the main characteristics of the two systems considered in the thesis, the Swedish and the Italian welfare systems, as the basis of an in- depth discussion on child protection systems. As highlighted recently by a number of scholars (Pösö et al., 2014), child protection systems are in fact intrinsically related to their own national welfare systems; however, this relationship is far from being entirely understood (cf.: Blomberg et al., 2012).

In order to shed light on the Italian and Swedish welfare systems in relation to families and children, it could be helpful to consider, with reference to the social work literature, the two traditional concepts of family service and child protection orientations in welfare systems.

A pioneering comparative study (Gilbert, 1997) on child welfare provisions in nine countries (Italy was not included) has become a reference point for the classification of child welfare systems. The study distinguishes child welfare systems characterised either by a child protection orientation or a family service orientation, based on how the problem of child abuse is framed and the range of mandatory reporting required by states.

According to this division, child protection social work is characterised by a primary concern for protecting children from abuse, usually from parents who are considered morally and legally culpable. The social work intake process associated with this orientation is built around legislative and investigatory concerns about the relationship between the state, represented by social workers in public services, and the parents, frequently being framed in an adversarial manner (Spratt 2001). Fargion (2007) an Italian social work researcher, considers that social workers’ main goal, in accordance to this orientation is, in fact, to determine whether the child has been abused or neglected, or whether there is a risk of this occurring; consequently, practitioners are likely to be perceived as enemies by parents. In fact, when the child protection orientation is adopted, the assessment becomes an outright inquiry, which often follows a particular procedure in order to reduce the probability of human mistakes.

This orientation has often been associated with English-speaking countries, particularly the UK and the US.

The family service orientation, which is traditionally associated with the Nordic countries, tends by contrast to focus on the whole family situation and is sensitive to families’ different experiences. Therefore, the responses of social workers are oriented more toward the provision of therapeutic and practical support, framing the relationship between the client and the professional as a partnership (Spratt 2001). As Fargion (2014) argues, ‘the protection of children is part of a broader spectrum of interventions meant to improve the lives of children and their families; it usually does not rely on separate units devoted to child protection’ (p. 26).

Recently, as a result of a follow-up study in the same countries and Norway (Gilbert, Parton and Skivenes, 2011), this polarised classification between child

protection and family service orientation is integrated with a third orientation

called child development. This new position seems to emerge in the analysis of the data that displays a slightly converging tendency regarding the two previous mentioned orientations:

Child protective systems such as the U.S and England had adopted features of the family orientation. In the U.S. for example, the emphasis on preventive family services increased and ‘differential responses’ programs were initiated

offering early support to families in need...[...]...In England practice was re-focused to maximize family support...[...]...at the same time countries which had been characterised as family-service oriented began to establish policy and practice which leaned more toward child protection. The Finnish Child Welfare Act of 2007, for example, formalized the process of intake, documentation and decision-making...[...]...Germany introduced mandatory reporting, initiated more investigatory risk control...and applied measures of ‘new public manage-ment’... (Gilbert, 2012: 532-533).

In a sense it is no longer easy to differentiate and precisely identify the orientations. The child development orientation emphasises children’s needs and the regulatory/ preventive intervention of the state when parents do not protect their children. Scholars reveal the ‘defamilisation’ tendency concealed in this orientation, enhances the relationship between the individual child and a paternalistic state (cf. Berggren and Trägårdh 2010). Its origins lie in the 1989 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and in the emerging social policy that tries to balance the protection of children with family oriented provisions.

The development of the Swedish welfare system can be considered closer to the later orientation that enhances the rights of the child as an autonomous individual, who can choose and deal with social workers, and in general with public officials, in order to request and decide on their own personal needs and solutions. This orientation is rooted in Swedish society to a much greater extent than in Italy, where the family is traditionally seen as an important reference unit of welfare.

The Swedish Welfare State

The Swedish welfare state is considered a reference point for many countries in the world (Forsberg and Kröger, 2010). Historically, it has its roots in the traditional goals of the Social Democratic Party that led the country from 1932 for approximately fifty consecutive years. The aim of reducing class differences in Sweden was guided by the political concept of “The People’s Home” [Folkhemmet] as a democratic vision of the future society (Ponnert, 2012). Free education, good living conditions, child allowances regardless of the parent’s income, and universal health care services stand at the basis of the Swedish welfare system, emphasising the rights of citizens in relation to the State. This has led to a decentralised system, based on universal entitlements and citizens’ rights satisfied mainly by State and municipalities with a high rate of public service provisions.

When considering Sweden (see table 1 p. 36), it is necessary to address the image of a long Nordic tradition of welfare. Nordic countries are in fact often described as child-centred welfare paradises in international comparisons. These welfare systems present a common tradition in family and child welfare characterised by comprehensiveness, generosity, universalism, gender equality and egalitarianism (Forsberg and Kröger, 2010). This image is emphasised and maintained by diverse international findings and standards on the quality of citizens’ living conditions that show a high level of health and well-being in the Nordic region (Nososco, 2013; Olafsson, 2013). Nordic countries also have common characteristics with regard to income distribution measured by the Gini coefficient; in comparison with other European countries, the difference in the income levels are smaller (Nososco, 2013: 28).

Nordic Welfare policies are oriented towards the full employment of citizens and are based on an interconnected system of macroeconomic, social, and active market policies. The purpose of meeting the most basic needs of citizens is based on public measures and interventions financed by taxes. Nordic countries maintain in comparison with other European countries a high level of proactive family measures; the greatly developed rules and regulations governing cash benefits in the event of childbirth and maternity leave have inspired similar systems in other countries. The expenditure on families and children, as percentage of GDP in Europe, shows clearly that the Nordic countries present almost identically high ratios, more than 3%, in comparison with other countries and, in particular, Italy with only 1.3% of the total social expenditure (Nososco, 2013: 32).

Moreover, family benefits and childcare policies have led to a higher female employment rate and greater shared responsibility for child-care between parents, in comparison with other European countries and particularly Italy. In the Nordic countries fathers are, for instance, entitled to daily cash benefits for long periods of time; in Iceland a new law on parental leave stipulates that mothers and fathers should have equal rights in their caring role (Nososco, 2013).

Moreover, in Sweden, as in the other Nordic countries, children are culturally seen as individuals with rights of their own: this child-centred vision permeates society and has also influenced social workers’ activity in public service units. Since 1945 a large number of Nordic organisations have emerged to promote cooperation in social work, highlighting the geographical proximity, a shared history and the similar languages, which enables and facilitates inter-Nordic exchange (Larsson, 2000). At the same time, a number of scholars commonly recognise the preventive orientation of the welfare system and the determination to achieve a normalisation of the family life as unique to the Nordic countries (Raunio, 2000).

Nonetheless, despite positive and widespread consensus, Swedish welfare and social politics are not immune to critique. Critical points of view have been expressed with regard to some previous developments of the system, and recently new voices have emphasised limitations and challenges.

A ‘dark page’ of the Swedish Welfare State took place under the age of ‘social engineering’ when many radical ideas regarding how society should handle social problems and prevent illness and disease in populations lead to the involuntary sterilisation of over 60,000 women. The sterilisation was planned by public authorities and occurred from 1935 until it was forbidden in 1976 (Ponnert, 2012: 227). This publicly authorised activity seriously encroached on individual rights during a period of generally positive modernisation of Swedish society (Björkman and Widmalm, 2010). Furthermore, this experience points out that there is a risk of excessive use of public power exercised in the name of the well-being of society. At the same time, this shows that the promotion of individual autonomy by the state in relation to the other institutions of civil society, such as family, makes the same individual powerless against the state. As stated by Berggren and Trägårdh (2010) in their provocative and challenging socio-historical analysis of the Pippi

Longstocking identity, ‘if too many people become dependent on the state, the

traditional idea of individual sovereignty turns into socialist subservience’ (p. 56). With reference to the issue of power within the different welfare systems, Pringle (2010), considering how the cultural contexts of the various Nordic countries impact on their welfare formations and practices, indicates that despite nuances between countries, the key focus of recent analysis still concerns the different emphases placed on solidarity and individualism (p. 165).

The Swedish child welfare system has traditionally been characterised by proactive state involvement in individuals’ and families’ lives, and is oriented to intervene in difficult situations in order to prevent greater problems in the future. Despite these preventive strategies, some authors state that due to cutbacks in public expenditures in the 1990s, the risk of marginalisation among some disadvantaged social groups such as immigrants and low-income single-parents has become a serious problem (Höjer and Forkby, 2011).

Moreover, some thirty years ago a critical point was raised against excessive social control towards families in distress. The accusation that the state interfered in the family sphere too much appeared in the public debate and Sweden, considering the high number of children taken into custody, was portrayed as a Kinder Gulag by some international journalists, for example in the German weekly magazine

Der Spiegel (Cocozza and Hort, 2011). At the same time, more recent scholars

concentrate particularly on the preventive orientation of the welfare system and have re-considered the authoritative position of social services in relation to

out-of-home interventions. From a comparative perspective, Pösö, Skivenes and Hestbæk (2014) point out that, in relation to other countries, the percentage of out-of-home placements and the number of removals in the Nordic countries is increasing (see also Nososco, 2013: 59). This clearly contradicts the preventive orientation of the welfare state, which promotes prevention in advance and seeks to avoid last resort interventions. On the other hand, other scholars still refer to the fact that Swedish out-of-home placement rates are relatively low in comparison with other Nordic countries. One study (Gilbert et al., 2011) compares such rates between 2000 and 2007 and reports that the majority of children involved were between thirteen and seventeen years of age, with a concrete focus on helping parents to manage teenagers instead of taking children from their homes because of parental neglect. Scholars retain that this result is in part related to the heavy gulag-critique that plagued Sweden thirty years ago.

Despite this critique the Swedish welfare system still remains one of the more extensive protective welfare states nowadays.

The Swedish child protection system

From a historical and legislative perspective, the structure of the Swedish child

protection system started to develop at the beginning of the 20th century through

the first Children’s Act of 1902.

This law requested municipalities to administer foster homes and to provide care for children up to seven years, and at the same time regulated state intervention in family life and compulsory care for youths to prevent ‘moral evil’ (Ponnert, 2012: 226). The major discourse on child care, as in other European countries at that time, was thus related to social control aiming to protect the whole society from deviant tendencies and criminal behaviours seen as potential threats to the well-being of society.

The Children’s Act of 1924 improved the organisation of child welfare through the introduction of local Child Custody Boards, for which it became obligatory to have as members a cleric, a teacher, a doctor and a woman. The law was influenced by socio-political movements in a period that led to the foundation of the Social Democratic Party’s social policy. In this period (1921) the universal right to vote was introduced.

After the Second World War, a new Children’s Act was promulgated in 1960. It was the first law that addressed preventive measures. A successive law, in 1982, the Social Service Act, represented a shift in social policy and emerged after an intensive and deep-going political debate in Swedish society. The end result of this

debate, both in the public and parliamentary arenas, was the decision that the social services’ methodology should mainly be based on preventive and supportive measures, which aimed to achieve equality and safety for people, with respect to their integrity and freedom. After a minor review in 2001, this Social Service Act still remains as the main legal reference for social services in Sweden (Ponnert, 2012: 228).

With reference to the protection of children and youth, the legal framework is provided by the Social Service Act (referred to in Swedish as SoL) and the Care of Young Person Act (in Swedish LVU, 1990). Further elements orienting social work practice can be found in the old code of parents’ responsibilities (1949). Considering Swedish child protection, a fundamental reference needs to be made to the penal relevance of parental corporal punishment. Sweden, in 1979, became the first country in the world that legally prohibited parents to make use of corporal punishment towards their children in order to discipline them. This law aims to protect children from harm through preventative measures for children that are, in general, aware of their rights and how parents should properly interact with them.

The Social Service Act is described as an outline law. It regulates competences and procedures; in particular, it focuses on assessment and decision-making processes. Moreover, it provides a national time-framework for investigation, limiting the assessment of children in need of protection or support to four months, and permiting social services to acquire information about families from other authorities or agencies without the parents’ consent (Sol 11: 2).

The Social Service Act also regulates the mandatory reporting system: public authorities and private personnel working in agencies concerning children have to report any suspicion of maltreatment or antisocial behaviour to social services. Debates about the effectiveness of this system are ongoing, in regards to decision-making and reporting, such as the decision to investigate a family or child’s case by means of assessment, or the final decision of activating a possible intervention.

Studies have focused on the purpose of reporting in specific contexts or professional groups, highlighting the failure to report (see: Cocozza, 2007: 24-26). Moreover, other scholars have studied how reports often do not lead to further investigation or intervention. Recent research on the final outcome of reports in a Swedish municipality during a whole year showed that the majority of reports concerned youth between thirteen and eighteen (60%). However, after the entire filtering process was completed, only a few children (16%) received interventions (Hort and Cocozza, 2012: 96).

In the case of municipalities’ social services assessing the needs of a child and of the family to receive care or protection (compulsory or not), the responsibility of satisfying their needs and eventually to safeguard a child rests with the local public services. When the compulsory care is assessed to be necessary for a child, the family, in case of controversy with the social workers, may apply for a final decision at the local board of social welfare (Socialnämnden).

The first stage of intervention entails personal support for the child through counselling and conversation with social workers. When children and youths need help they can also be supported in everyday life by a contact person or a contact family. This type of support is quite ‘light’ in comparison with the more intrusive and expensive supportive interventions. In general, policies are now to a rising degree becoming more oriented towards introducing parent training programs and home-based interventions, with the aim of reducing the high cost of out-of-home placements and institutional care, which have also become more and more challenged by criticism and doubts about their capacity to provide positive care outcomes (Ponnert, 2012: 237).

The Italian Welfare State

With reference to Titmuss (1974), the Italian welfare system has been recognised as an example of the particularistic-clientelistic model. Nowadays, among researchers, it is sometimes characterised as an example of a Southern European (Esping-Andersen, 1990) or Mediterranean (Ferrera, 1996) welfare system (see table p. 36).

The following quote comes from an effort to better understand the development of the welfare state from a historical perspective. It describes the complex position of the national and regional social provisions of the Italian welfare model (Lynch, 2014, p. 381).

The central characteristics of the Italian welfare state during the “golden age” of the 1960s-1980s, which persisted into the cautious reform era of the 1990s-2000s, were its Bismarkian structure and male-breadwinner orientation. In the Bismarkian model, social policies are financed by contributions from employ-ers and workemploy-ers; and the level of benefits...(...)...can vary from sector to sector and from job to job within sectors.

The male-breadwinner orientation assumed that the modal family had a hus-band employed in the formal sector and a wife at home caring for children and elders, resulting in a welfare state heavy on cash transfer and light on

servi-ces...(...)...but strong employment protection legislation coexisted with miserly unemployment insurance. There was no coverage for first-time jobseekers and only minimal attention to active labour market policies. Family allowances were modest if compared with elsewhere on the Continent, and outside a pro-gressive pocket like Emilia-Romagna [region] there was limited access to child-care, elderly care and other social services. ...(...)...Italy had no national safety net for non-elderly: a national minimum income never developed, and cash allowances and services for the indigent varied widely from region to region. The brightest star in Italy’s welfare state, at least after 1978, was the National Health Service (NHS), which provided universal access to medical care, funded at the national level and administrated at the regional level.

Consistent with this description, the Italian welfare system is traditionally based on pensions, education, and health care. Italian pension expenses are the highest in Europe: in 2008 pensions represented 60% of national social expenditure, with an increase of 3% in comparison to 1991 (Ascoli and Migliavacca, 2011: 48). On the contrary, social services remain at the margin of the welfare project.

The first national Social Service Reform in the year 2000 (law 328/2000) introduced an integrated system of social intervention and provisions characterised by the strong presence of third sector organisations collaborating with public services.

In recent years, cost-containment policies and the transition to a regional decentralised system, due to the Title V constitutional reform (2001), endangered the coherent development of a comprehensive national welfare state, increasing differences among regions and inequalities among municipalities in terms of welfare provisions (Graziano, 2009; Kazepov and Carbone, 2012: 79).

The constitutional reform has exacerbated the differentiation of the Italian system at the regional and local levels, in particular between the South and the North part of the country. From 2001, any regional council could independently change social welfare policy; therefore, due to the lack of a national framework, municipality social service provisions present stark inequalities between local communities. The main factor contributing to this situation is the absence of a definition of a minimum standard of social provisions which every municipality must deliver.

Italian scholars have highlighted four main problematic characteristics of the welfare state: the fragmentary character of social policies, the unbalanced redistribution of public expenditure, the clientelistic orientation of measures, and finally the passive subsidiarity (Kazepov, 2011: 121).

Moreover, other researchers confirm a substantial inertia of the Italian welfare system in addressing major changes in population needs, in particular, with respect to unemployed youths, families with many children, and immigrants.

Therefore, the Italian Welfare system is considered a welfare-mix system with high emphasis on family resources and on the contribution of third sector actors in supporting public services for the satisfaction of citizens’ needs (Ascoli and Ranci, 2003).

The relationship between the state, municipalities and third sector actors has been the subject of several local and national studies (Calbi, 2007; Lundstrom and Svedberg, 2003; Fazzi and Borzaga, 2011; Maino and Ferrera, 2013) that confirm the crucial role played by foundations, cooperatives, associations and other non-profit organisations in the well-being of the Italian community. In particular, in recent times it seems that the impact of the economic crisis on the Italian welfare system has resulted in a greater involvement and reinforcement of non-profit organisations instead of the market, as has occurred in other European countries (Bertotti and Campanini, 2012b).

As regards social provisions, the traditional role of the Catholic church in helping the poor in Italy should be noted. Many associations and third sector agencies are related to the Catholic system. Caritas, in particular, is a national network present in 220 dioceses. The Caritas ‘Report on Poverty and Social Exclusion in Italy’ constitutes a reference to understand families’ economic predicament and is based on data collected by more than eight-hundred Caritas social shelters in Italy. The 2014 report depicts an increase in poverty and also in the numbers of Italian recipients of social welfare (38.2%) in comparison with immigrants (61.8%), who are the traditional users of such help (Caritas, 2014). This data shows that the present economic recession and labour crisis is affecting families’ well-being and in particular families with children, who are exposed to poverty.

The Italian child protection system

The Italian system of child protection was developed during the 1990s, promoted by professional mobilisation rather than through an organised and systematically developed child welfare policy. In fact, as condensed by Bertotti and Campanini (2012b):

compared to other European countries, Italy moved late, and in fragmented and contradictory ways, towards the adoption of a child welfare policy that conceived a child as a subject with rights, and that is coherently planned and

implemented. During the 1980s, the government established national commit-tees specifically aimed at promoting special policies for children, but the main result of their work has been listing the area of need, rather than improving child welfare services. Even now, policies targeting children are hardly separa-ble from those targeting families. Moreover, Italian child policies follow the re-sidual approach, which addresses only children in need, instead of considering the range of support required by families in their daily life.

Taking that into account, Italian child welfare policies are in a sense contradictory, as they declare a universalistic orientation, but de facto realise a fragmented system with strong variations among regions and municipalities, the lack of resources emphasises the public social services focus on malfunctioning families (Saraceno, 2002; Fargion, 2007).

The child protection system in Italy derives from the development of a public debate on the prevention of child abuse and family support. The system is based on laws and regulations at the national level, in particular in the civil code, that are not comprised in framework acts, as in Sweden.

Bertotti and Campanini (2012a) summarise the process of affirmation of a diffuse culture of child protection in three phases. Starting from the 1980s in Milan, the action of the Italian Association for the Prevention of the Abuse to Children (AIPAI) led to the foundation of the CBM, a non-profit centre for the treatment of family crises, that promoted the idea that child abuse is a family problem that is often not even acknowledged by the family itself. The CBM approach emphasised the necessity to connect the protection of children with family treatment and became a reference point for the development of the Italian child protection services within the Italian legal framework.

In the 1990s, the system of protection developed through collaboration between the court, the local public social services and health services; new multi-professional teams composed by social workers and psychologists were built, and the increasing awareness of the prevention of sexual abuse (laws 66/1996 and 269/1998) became widespread.

After some years, together with this new public consciousness, the system was criticised in relation to child protections scandals, but ‘unlike some other European countries, in Italy the scandals were not used as an opportunity to explore in depth how the child protection system functioned and how it could be improved (Bertotti and Campanini, 2012a: 7).

The final phase developed during the first decade of the 21st century, and was

characterised by the separation of the health and social care systems at a local level. The child protection functions were moved from the healthcare system to the local

authorities. On the one hand, the aim was to promote preventive interventions through a closer link between child protection units and the local agencies, and on the other, to control the rising expenditure related to child protection residential care. This period has been characterised also by the promulgation of new laws regarding custody of children: an equal position between separated parents as regards child custody was introduced by the law 54/2006. More attention has been paid to domestic violence and assisted violence in separations, in particular the law 154/2001 permits the removal of a violent person from home and law 11/2009 defines stalking and harassment as a legal offence and institutes strict punishments for it.

The child protection system was influenced by these new sectoral laws introducing the possibility of equally shared responsibility between parents and at the same time enhancing the protection of mothers and children from domestic violence. The child protection system in Italy is nowadays based on the fundamental relationship between the court and the local social services, with the necessity to activate and build connections with health agencies, schools and third sector organisations in order to prevent, detect and treat possible case of maltreatment and abuse.

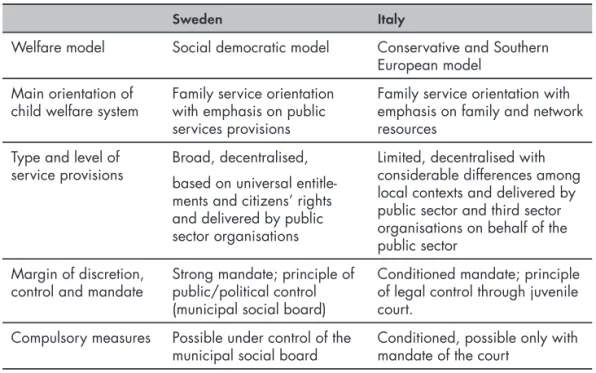

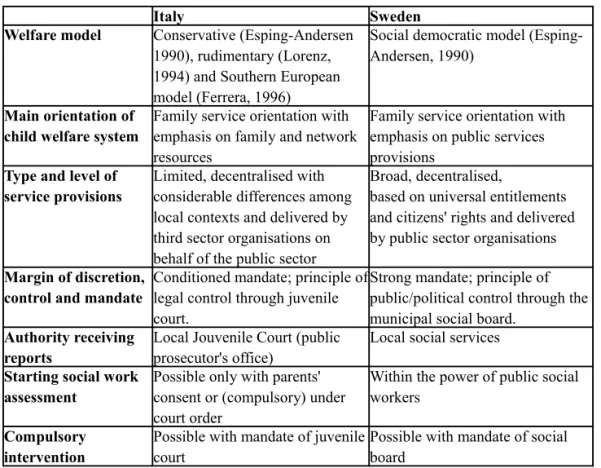

Table 1. Comparison between Swedish and Italian child welfare and protection systems

Sweden Italy

Welfare model Social democratic model Conservative and Southern European model

Main orientation of

child welfare system Family service orientation with emphasis on public services provisions

Family service orientation with emphasis on family and network resources

Type and level of

service provisions Broad, decentralised, based on universal entitle-ments and citizens’ rights and delivered by public sector organisations

Limited, decentralised with considerable differences among local contexts and delivered by public sector and third sector organisations on behalf of the public sector

Margin of discretion,

control and mandate Strong mandate; principle of public/political control (municipal social board)

Conditioned mandate; principle of legal control through juvenile court.

Compulsory measures Possible under control of the

municipal social board Conditioned, possible only with mandate of the court

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

Comparing the same phenomenon in different contexts is a common way of developing knowledge in social sciences, and this is also true for the social work discipline, relatively new in the broad family of social science.

The object of this study is the social work assessment in public social services dealing with families and children at risk in the Swedish and Italian contexts. The general basis of the present comparison relies on the fact that countries - in this particular case Sweden and Italy - have developed, with different emphasis, provisions for supporting human development and the well-being of citizens, under the acknowledgement of human rights in the last decades. In particular, for protecting vulnerable groups in society, such as children, youth, disabled people and the elderly. This has pushed countries to promote welfare systems, which employ professionals in these areas, in order to achieve these goals. The welfare system is then defined in politics, mediated by organisations at a local level, and implemented by the local practitioners to potentially reach every individual citizen and family in need.

The experience of citizens and families with public social services are, in the words of Lipsky, ‘the predictable consequence of the structure of particular kind of public sector work’ (Lipsky, [1980] 2010: 221). Professionals in public sectors must, in fact, mediate between professional values and ethics, institutional mandate and contextualised resources (i.e. client’s resources and available helping provisions), through their professional competence in order to achieve welfare system goals.

Social workers play a crucial role in the welfare system where they are often recognised as case-managers; they are often considered as the profession, which represents the interface between public social service institutions and citizens.

The position of social workers in public social services is like that described by Lipsky as ‘street level bureaucrats’; civil servants who ‘work in situations that often require responses to the human dimensions of situations. They have discretion because the accepted definitions of their tasks call for sensitive observation and judgement, which are not reducible to programmed formats’ (2010: 15). In other words, in order to implement their assessment, social workers need a certain level of discretion; in fact, it would be impossible to work if discretion were severely reduced. Moreover, Lipsky considers that ‘the maintenance of discretion contributes to the legitimacy of the welfare-service state’ (2010: 15).

The similarities and differences in social work assessments, and also the recurrence of phenomena and its exceptions, which emerged in the same group of professionals in Sweden and Italy, are not only referable to the discretion of a single human professional. They need to be contextualised in their own environment in order to be fully understood, in particular, in relation to the role that social workers play in the welfare systems in which they are embedded. The knowledge derived from the research can be better understood in its own context, that it is highlighted through the cross-national comparison.

Considering the interaction between social workers engaged in public social services and clients, Lipsky (2010) provided an original contribution that shed light on the complexity of the social workers’ mandate in relation to, on the one hand, families, and on the other, their multifaceted interaction with public institutions, where social workers are mainly employed. Lipsky stressed how professional discretion may affect for instance the selection of clientele, reducing access to provisions in particular situations, and described how more disadvantaged people often depend on street level bureaucracies, as they have no other options (p. 55). Recently scholars have rediscovered this fruitful contribution, researching in particular how social work practitioners use discretion with clients.

Lipsky’s conceptual contribution is, however, deeper and focuses on the position of the so-called street level bureaucrats in the welfare system, depicting the complex relationship between the implementation of politics and the social work profession, which is embedded in public institutions and deals with citizens on a day-to-day basis (cf.: Ostberg, 2012; Cappello, 2014). In fact, ‘street level bureaucrats have some claims to professional status, but they also have a bureaucratic status that requires compliance to superiors’ directives’ (Lipsky, 2010: 19).

For the purpose of the present work, Lipsky’s contribution (2010) is relevant, as it defines a significant connection between national welfare politics and the individual professionals that are the face of the public institutions and who