A

FLORISTIC STUDY OF POLYLEPIS

FOREST FRAGMENTS IN THE CENTRAL

A

NDES OF

E

CUADOR

Ulrika Ridbäck

Examensarbete i biologi, 15 hp, 2008

Handledare: Bertil Ståhl

___________________________________________________________________________ Institutionen för kultur, energi och miljö

Högskolan på Gotland/Gotland University, SE-621 67 Visby

CONTENTS

RESUMEN/ABSTRACT ………...2

INTRODUCTION………...…....…...3

Background………...………...3

The genus Polylepis………...………....3

Earlier studies………...………..4

Why are Polylepis forests important? ………...…....5

Objectives………...………...……5

STUDY AREA………...………...6

Oyacachi………...……….6

Climate………...………7

MATERIAL AND METHODS………...…..8

RESULTS………...9

Observations of the remnants of Polylepis pauta forests………...9

Species richness of vascular plants………....9

Phytogeography………....10

Endemism……….10

Remnant of Polylepis microphylla forest at Achupallas………..10

DISCUSSION………...………...11

Species richness………...11

Conservation………11

Different Polylepis forests………...13

Reforestation………....13 Further studies……….14 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS………14 REFERENCES.………...14 SAMMANFATTNING…..……….16 APPENDIXES………...………...19

Appendix 1: Plant species of Polylepis forest and their distribution………...19

Appendix 2: Páramo plant species and their distribution………....24

Cover picture: Calceolaria ericoides (Scrophulariaceae) Photo: Ulrika Ridbäck

Denna uppsats är författarens egendom och får inte användas för publicering utan författarens eller dennes rättsinnehavares tillstånd. Ulrika Ridbäck

RESUMEN

La presencia de los seres humanos ha afectado a los bosques de Polylepis desde hace mucho tiempo en los Andes de Ecuador. El objetivo de este estudio es la examinación de la flora de plantas vasculares en los bosques dominados por Polylepis pauta. Especies conocidas de plantas vasculares fueron registradas y especies menos conocidas fueron recolectadas. Todos los datos incluyendo coordenadas y altitud fueron analizados en el Herbario QCA. Se han registrado un total de 104 especies de plantas vasculares, el número de especies recogidas varía entre 16 y 36 en cada estudio local. Principalmente especies andinas dominan los bosques de P. pauta, 75 de las cuales están restringidas a los Andes. Se encontraron un total de 20 especies endemicas del Ecuador. Los bosques de Polylepis son un tipo único de hábitat por lo que vale conservar como un único tipo de hábitat. Polylepis puede contribuir con habitat y protección para los animales y las plantas, especialmente epífitas. Programas de reforestación con Polylepis podrían ser una buena alternativa para la zona de Oyacachi.

ABSTRACT

Human activity during several thousands of years has considerably changed the forests of

Polylepis in the central Andes in Ecuador. The objective of this study was to examine the

flora of vascular plants in forest fragments dominated by Polylepis pauta in the Oyacachi area in central Ecuador. Known species of vascular plants were recorded, and species not identified in the field were collected. All data, including coordinates and altitudes, were stored in the QCA Herbarium database. A total of 104 species of vascular plants were recorded. The number of species found varied from 16 to 36 between different localities. The P. pauta forests are dominated by Andean species, 75 of the recorded species being restricted to the Andes. Of these, 20 are endemic to Ecuador. The Polylepis forest as such is worth conserving as a unique kind of habitat, and can contribute with shelter and protection for many animals and plants, especially epiphytes. Reforestation programs based on Polylepis could be a good alternative in the Oyacachi area.

INTRODUCTION Background

One of the richest floras in the world is found in South America. The Andes is a relatively young mountain chain that runs through the continent. The setting with a geologically recent uplift and a tropical and fluctuating climate has generated a plethora of species on and below the Andean slopes.

Deforestation in the Andes has a long history, and different ethnic groups inhabited the Andean highlands many generations before the Spanish conquistadors arrived (Lippi 2004). Since humans entered this region the forests have been used as a source for building material and fuel (Fjeldså & Kessler 1996). Much of the forests were also cleared to produce farm land and pastures. The best known ethnic group before the Spanish colonisation, the Incas, used a terrace system which successfully kept the horizontal fields from erosion (Jørgensen & Ulloa 1994). To obtain more land for cultivation additional forests were cleared, which led to a reduction of natural vegetation. New agricultural techniques where introduced by the Spanish colonists and they abandoned the terraces used by the Incas. The deforestation continued and the Mediterranean type of agriculture practiced by the Europeans contributed to land

degradation through soil erosion. The high Andean landscape seen today is dominated by grass páramos. Remnants of high Andean forests, which have been conserved to present time, consist largely of Polylepis spp., which often inhabit inaccessible steep slopes outside the inter-Andean plateau.

The genus Polylepis

Polylepis is a genus in the family Rosaceae and is restricted to the high Andes. Seven species

of Polylepis are known from Ecuador (Romoleroux 1996), of which Polylepis incana, P.

pauta and P. sericea are found in the Oyacachi valley (Ståhl et al. 1997). Polylepis is well

adapted to the harsh climate in the mountains, having reduced flowers and leaves covered with woolly hairs (Fjeldså & Kessler 1996). The trunks wear thick and rough bark, a protection against nocturnal frost. At altitudes between 3500 and 4000 m, Polylepis is the only resource of wood in a zone where other tree species are unable to grow (Fjeldså & Kessler 1996). Some species of Polylepis even occur at an altitude of 4850 m (Braun 1997). The Polylepis forests are most common in mountain slopes, deep canyons and ravines, often among rocks and boulders. The growth of Polylepis has been hypothesised to be limited to favourable microclimatic conditions, which occur on rocky isolated slopes (Velez et al. 1998). However, today most scientists believe that the high Andean vegetation largely is

anthropogenic. The practice to burn large areas to create and improve pastures has reduced

Polylepis forests to a few percentage of their original extent (Kessler 2002). Remaining

patches of Polylepis forests are spread out in an open landscape, separated by huge areas of grass páramo. The borders between the forests and the páramos are usually sharp.

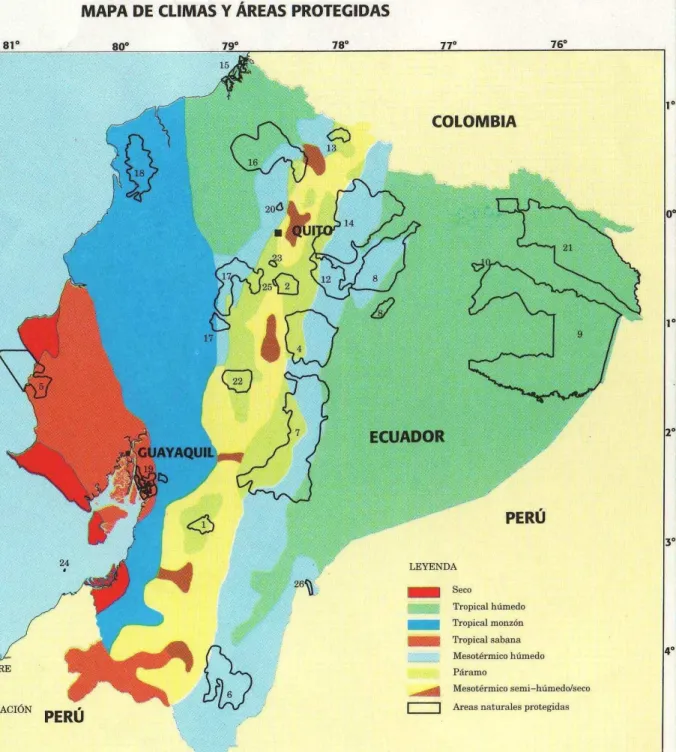

Fig. 1. Map of Ecuador, showing the location of the Cayambe-Coca Ecological Reserve, nr 14 (Mapa físico, República del Ecuador 1999).

Earlier studies

Little is known about the floristic diversity within Polylepis forests (Fernández & Ståhl 2002). In Ecuador, earlier studies of Polylepis forests have been done in the vicinity of Oyacachi in the Cayambe-Coca Ecological Reserve (Fig. 1), an area protected since 1970 (Morales & Schjellerup 1997). The DIVA-project (1996-1997) studied the interactions between the people in the village Oyacachi and the environment, to estimate the biological consequences caused by present and potential future land use (Skov 1997). Focusing on a few target taxa (ferns, Rubiaceae, Piperaceae) the Polylepis forests were also studied within the DIVA-project, but only at a few sites near the village. Studies of Polylepis near Oyacachi have also been carried out by Cierjacks et al. (2007) in Polylepis stands at Páramo de Papallacta. They studied the

capacity of lateral expansion and focused on the possibility of recovering to dense Polylepis forest stands. Cierjacks et al. (2007) made transects to examine the cover of herbaceous vegetation in Polylepis incana and P. pauta forests. In a follow-up study, Cierjacks et al. (2008) investigated reproductive traits, site conditions and stand structure of P. incana and P.

pauta in Páramo de Papallacta, with the effects of altitude and cattle as limiting factors. Fehse

et al. (2002) examined the possibility of carbon offsets at a P. incana forest, by quantifying aboveground biomass. The study took place near Pifo, 20 km southwest of Oyacachi.

Several floristic and biogeographic works on Polylepis forests have been done in Bolivia. One study, which gave inspiration to this present work, was carried out in the Andes of south-central Bolivia by Fernández & Ståhl (2002). They investigated the conditions for vascular plants in Polylepis forests at different localities in the Cordillera de Cochabamba.

Why are Polylepis forests important?

The forests of Polylepis have a unique biological diversity and provide many important ecological functions (Fjeldså & Kessler 1996). The trees harbour many species of epiphytic vascular plants, mosses and lichens, as well as animals, including mammals and birds. In a landscape dominated by open páramos, the forests give shelter, nesting sites, and food to many mammals and birds.

Being native to the Andes, Polylepis is of great value for reforestation programs. No other tree genus is better adapted to the high Andes (Jørgensen & Ulloa 1994). Polylepis provides local people with building material and firewood, and protects the soil from erosion (Fjeldså & Kessler 1996). The wood is heavy and resistant to decay under humid conditions. The forests also create a stable water source, since large amounts of water can be stored in the vegetation and in the soil.

Within the Oyacachi community, small patches of Polylepis forest still exist. Road

constructions have damaged parts of the Polylepis forests in the area (Ståhl et al. 1997). To create better conditions for conserving these forests, knowledge about the biodiversity and the value of saving it would bring benefits to both the nature in the area and the people living in it.

Objectives

The objective of this study was to explore the flora of vascular plants in forests dominated by

Polylepis pauta. The work was carried out within a project organised by Universidad

Católica, Quito, aiming at mapping the biodiversity and extension of the remaining forests of

Polylepis in the Oyacachi area (Romoleroux et al. 2007), northeast of Quito, and to make a

guide to vascular plants associated with Polylepis forests. I also visited another part of Ecuador to study and compare the vascular flora in an area dominated by a different species of Polylepis, i. e. P. microphylla. Although inventories have been general, special interest has been given the family Rosaceae, including genera native to the high Andes, i.e. Polylepis and

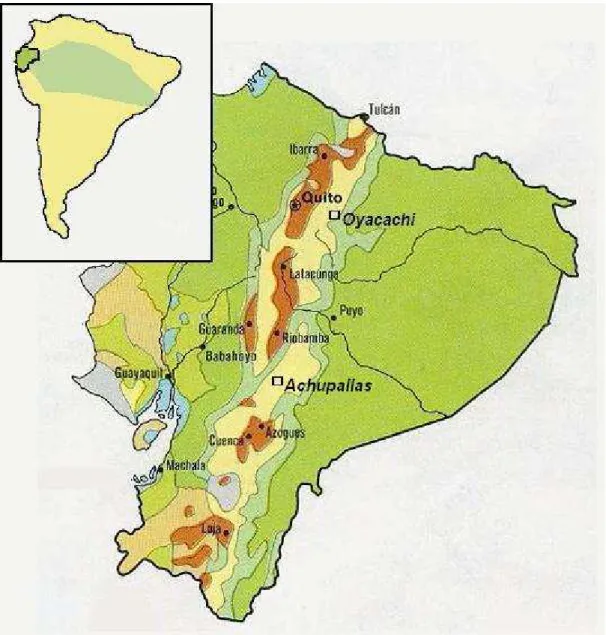

Fig. 2. Map of Ecuador, showing the studied Polylepis localities: Oyacachi and Achupallas. (Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection 2007).

STUDY AREA

The Oyacachi area, where this study was carried out, is situated about 45 km (by air) east of Quito in the Coca-Cayambe reserve in the eastern Cordillera of the Andes, just south of the equator (Fig. 2). The investigated forests are located at altitudes between 3800 and 4000 m. The surrounding areas consist mainly of grass páramo and scattered stands of Polylepis.

Oyacachi

The only settlement in this region is the village of Oyacachi, located in the upper part of the Oyacachi valley, at an altitude of 3200 m. The local community consists of Quichua speaking Indians, most of which are fluent in Spanish. People have been settled here since the middle of the 16th century (Morales & Schjellerup 1997). In late pre-Columbian times and during the earlier part of the Spanish colonization, the community was presumably organized as a small chiefdom. The people from the village of Oyacachi became christened in the 1580’s. Until the middle of the 1600s, Oyacachi was under the religious doctrine “Doctrina Del Quinche”, which is based on a legendary miracle, better known as Virgen de la peña (Gente de la

Biorreserva 2008). After that epoch, the valley was of little interest to the scholarly world until the end of the 1800s. (There are two churches in the village, an Evangelic built in 1979 and a Catholic built in 1983).

Río Oyacachi has its sources in the highlands west of the village of Oyacachi, which it passes on its way to the Amazonian lowland. Two unpaved roads lead to Oyacachi, one via

Cangagua, northeast of Quito, and one via Papallacta, southeast of Quito. These roads were constructed as late as in 1995-96. Earlier all transportation and contacts with the outside world was made by foot and with mules (Morales & Schjellerup 1997). The nearest market was reached in two days. Thus, the construction of the roads has drastically changed the social and economic base for the villagers. The village of Oyacachi is much visited by national tourists in the weekends because of the termal springs and the recently constructed pools. Some lakes are found in the higher part of the reserve, which is a popular area for fishing and hiking. The community has the right to use a large part of the valley of Río Oyacachi.

Today Oyacachi is a society with approximately 500 inhabitants (Morales & Schjellerup 1997). The village has its own power plant for electricity, which is using a tributary of the Río Oyacachi. There is a system for drinking water, installed 1985, and the community does not pay any fee for using the water. There is also a sewage system since 1996, and that includes the treatment of the outflow waste before it reaches the Río Oyacachi.

The people of Oyacachi cultivate root vegetables, local varities of corn, broad beans, peas, vegetables, and fruits such as banana (Musa sp.), blackberry (Rubus ssp.), lemon (Citrus sp.), naranjilla (Solanum quitoense), pepino (S. muricatum), passionfruit (Passiflora mixta), physalis

(Physalis peruviana) and tree tomato (Cyphomandra betacea). They have cattle and also produce their own cheese. Wood of alder (Alnus acuminata), which is abundant in the valley, is used for carving and the making of household tools (Morales & Schjellerup 1997). Polylepis is useful for fuel wood and fence poles, but is less used to other household purposes. However,

Polylepis should be useful as building material, considering the resistance against rot, but it is

not likely that boards large enough can be obtained from the usually bent and twisted stems. Modern necessities, like petrol and medicine, are bought in the nearest towns, i. e. Cayambe and Otavalo.

Climate

The Oyacachi valley has three Holdridge life zones (Holdridge 1967): Lower Mountain wet forests from 1600 to 2900 m alt., Mountain wet forest at 3000- 4000 m alt., and Subalpine páramo above 4000 m alt. (Skov 1997). These life zones receive a rainfall at least twice as large as the potential evapotranspiration. Mean annual rainfall at 4000 m alt. is 1700 mm per year. Mean annual temperature range is related to altitude and about 10°C at 3200 m,

decreasing to 5°C at 4000 m alt. On average the temperature decreases with 0.66°C per 100 m ascent (Fjeldså & Kessler 1996). The diurnal variation in temperature is also large and varies with altitude. There is no clear seasonality, the conditions being humid all year round.

However, some months are wetter than others and the local people refer to these as “winter”. According to the diurnal variation, one day can be divided into different climates, from cold at night to warm at midday. The topography affects the rainfall and produces locally restricted climatic conditions. For example, cloud condesation is important for Polylepis forests as such as well as for the surrounding areas (Fjeldså & Kessler 1996). Rocky slopes tend to be moister than other slopes, because the rainwater is stored between the rocks. Temporary snowfalls are common in the upper part of the valley, but without producing a permanent blanket of snow.

Fig. 3. The study localities in the vicinity of Oyacachi (Google Earth 2007).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This study took place from late January through March 2007. The main project, Diversity and extension of the Polylepis forests in Oyacachi (Romoleroux et al. 2007), which includes this floristic study, will continue at least until the beginning of 2008. When possible, two or more days per week were used for fieldwork. The rest of the time was used to process the collected plant material and complete written records.

A permission issued by the Ministry of Agriculture in Quito was required for each visit to the Coca-Cayambe reserve when entering from Papallacta. This road is about one hour shorter than the other entry, via Cangagua, north of Oyacachi, and has also valuable vegetation for these studies nearby.

Most of the fieldwork was carried out at three different Polylepis localities (Romoleroux et al. 2008), here named 1, 2a, and 2b (Fig. 3). Some plants of interest were collected outside the

species of vascular plants and ferns were recorded, and less familiar species were collected. Sterile plants were not collected or recorded, because of identification difficulties. Altitude and coordinates were recorded at the borders as well as in the centre of the Polylepis forests. The collected plants were dried at the herbarium of the Universidad Católica in Quito (QCA), where all plants were identified to species or genus. The plants were sorted into families and collection data were organized in the Excel programme. Besides information on locality, data on the plants including life form (tree, shrub, herb, fern, liana, climber or epiphyte) as well as floral and fruit characteristics were stored. Dried vouchers are deposited in the QCA

Herbarium.

During my last week of fieldwork I made a trip to Achupallas (Fig. 2) about 250 km (by air) south of Quito, in the province of Chimborazo. Here, plants were collected in a small forest stand dominated by Polylepis microphylla. This material was also processed and deposited in the QCA Herbarium.

RESULTS

Observations of the remnants of Polylepis pauta forests

The Polylepis pauta forests of the Oyacachi area are left in steep terrain surrounded by grass páramo at altitudes between 3800 and 4000 m. Small streams flow through the forests and the ground outside the forests is wet. The vegetation within the forests is dense, but the outer parts are more open. Tree branches are covered by mosses, lichens, ferns and various species of climbing or epiphytic vascular plants.

Humming birds were seen in the forests and owls were observed in the area nearby. Observed mammals were deer and páramo rabbits. The largest mammals known to occur in the area are the mountain tapir (Tapirus pinchaque) and the Andean spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus), but none of these species were observed during my visits. There is also one species of fox common in the páramos. Cattle graze near and at the edges of the forests.

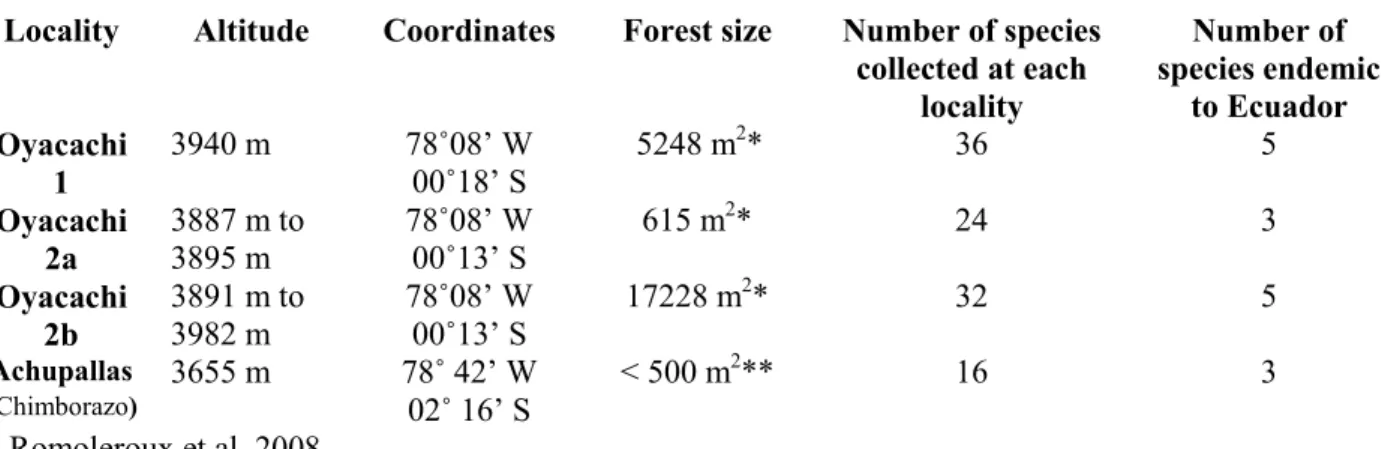

The locality 1 (Table 1) is situated on a small south facing slope at 3940 m altitude. The vegetation between Polylepis trees is sparsely distributed in the outer part of the forest and denser in the inner part. Locality 1 had the biggest number of collected species. The localities 2a and 2b, also on a south facing slope, were once part of one bigger Polylepis forest, but these two stands were separated by the road construction between Papallacta and Oyacachi. The distributions of the vegetation in the locality 2a, at 3887 m, followed the same pattern as for locality 1. But locality 2b, at 3891 m, had a more dense vegetation at the border to the páramo, with a very impenetrable inner forest. The number of collected species at locality 2b was lower than at the smaller forest locality 1. The localities 1 and 2b had the highest number of endemic species.

Species richness of vascular plants

A total of 82 species of vascular plants were collected in this study (Appendix 1) and an additional 22 species were collected in páramo habitats outside the Polylepis forests (Appendix 2). The number of collected species per locality varied from 16 to 36 at each studied locality (Table 1). The Polylepis locality 2a, beneath locality 2b, had more species of ferns than the other forest remnants. Only one tree species was present in each forest,

Polylepis pauta in locality 1, 2a and 2b, and P. microphylla at Achupallas. However, the tree

species Gaiadendron punctatum was seen growing near the edge of a P. pauta forest along the road between Papallacta and Oyacachi. The mixed upper montane forests above the

village of Oyacachi include trees of Alnus acuminata, Buddleja bullata and Escallonia

myrtilloides (Ståhl et al. 1997), but none of these species were found in the Polylepis forests

examined here. Most of the species collected, 67%, were herbs; shrubs and epiphytes constituted 14 % and 7,5 % of the species, respectively; 7,5 % of the species were ferns.

Table 1. Investigated Polylepis forest remnants.

Locality Altitude Coordinates Forest size Number of species

collected at each locality Number of species endemic to Ecuador Oyacachi 1 3940 m 78˚08’ W 00˚18’ S 5248 m2* 36 5 Oyacachi 2a 3887 m to 3895 m 78˚08’ W 00˚13’ S 615 m2* 24 3 Oyacachi 2b 3891 m to 3982 m 78˚08’ W 00˚13’ S 17228 m2* 32 5 Achupallas (Chimborazo) 3655 m 78˚ 42’ W 02˚ 16’ S < 500 m2** 16 3 * Romoleroux et al. 2008.

** Estimated forest size according to coordinates.

Phytogeography

Polylepis pauta exists in the Andean region from northeastern Ecuador to southern Peru

(Romoleroux 1996). The species of vascular plants found in the P. pauta forests are mainly Andean. According to distributional data in the Tropicos database (Tropicos 2007), 75 species (72 %) are restricted to the Andes. A majority of these 41 species, are north Andean

(Venezuela – Peru), and 11 of these have the same distribution as Polylepis pauta. Fifteen species occur partly in the southern parts of the Andes (Bolivia – Argentina). Among species that also occur outside the Andean region, 20 % are found in Mesoamerica and South

America at altitudes of 1000 m or higher. One herb, Gnaphalium purpureum, is introduced to Ecuador from California, USA, one species of fern, Pleopeltis macrocarpa, reach as far as Africa and Madagascar, and one angiosperm, Urtica dioica, is cosmopolitan.

Endemism

A total of 12 species endemic to Ecuador were found in the studied P. pauta forests and 6 additional endemics were collected in the surrounding páramo. This corresponds to 17.5 % of all species in the study. The P. pauta localities 1 and 2b were richest in endemics, with five taxa each. Six of the endemics are red-listed in Ecuador. Herbs dominate among the endemic species and the only endemic tree in the area was the hybrid Polylepis pauta x P. sericea (Polylepis loc. 1), which also occur in the provinces Imbabura, Napo and Pichincha.

Remnant of Polylepis microphylla forest at Achupallas

The Achupallas forest remnant is located at 3650 m altitude in an area dominated by pastures, near the village of Achupallas in the province of Chimborazo. It was a severly degraded patch of Polylepis forest, visibly appearing more like a piece of the páramo and mainly dominated by wide spread páramo species. The cattle grazed among the remaining vegetation. Some older P. microphylla trees created a small grove, but the main part consisted of young trees, small as shrubs, in an area strongly affected by human activities. In this forest, 16 vascular plant species, mostly herbs, were collected, 14 of which did not occur in the samples from the

P. pauta forests in Oyacachi. Three taxa were endemic to Ecuador, i. e. Lachemilla rupestris, Polylepis microphylla and Calceolaria hyssopifolia.

DISCUSSION Species richness

This study aimed at investigating the plant species in the remaining forests of Polylepis pauta. Only 82 species of vascular plants were collected and an additional 22 species were collected in páramo habitats outside the Polylepis forests. All the collected plants were flowering and some were also fruiting, which facilitated the identification work and contributed with more information about the plants. Since sterile species were left uncollected and unrecorded the true number of vascular species is unknown. However, earlier studies imply that there are comparatively few species of vascular plants in Polylepis forests (Fernández & Ståhl 2002). In this study no plots were made for the collecting of species, but the species numbers compare fairly well with those from transect studies of the Polylepis forests of the Cordillera de Cochabamba in Bolivia (Fernández & Ståhl 2002), although those transects were made at lower altitudes. The high altitude at the investigated localities in this study should be taken into account, though there is no significance that it affects the number of species.

The localities 1 and 2a had twelve species in common, of which four species were ferns. One fern species, Hypolepis crassa, is endemic to Ecuador, and the fern Polypodium mindense is redlisted in Colombia and Ecuador. The Polylepis locality 2a was denser in the number of ferns than the other forest remnants. This might be a consequence of wetter conditions of this locality, situated at the bottom of a slope. However, it was a low in number of fern species compared with other studied Polylepis forests. The other species at the localities 1 and 2a are more or less common throughout the Andes, but the shrub Miconia croceaoccur only in Colombia and Ecuador.The localities 1 and 2b had only nine species in common, of which only two species were ferns. Almost all species are distributed in the Andes from Colombia to Chile, but one herb, Lachemilla nivalis, is endemic to the Andes of Ecuador. One herb, Luzula

gigantea,is widely distributed in Mesoamerica and South America. The majority of the collected species consisted of herbs, at all localities. Totally all localities had six species in common, which were expected to be common in the Andes. But these species are distributed in different Andean countries, the majority from Colombia to Peru. Polylepis pauta was the only tree species occurring at all localities. Though, Polylepis pauta is limited to the Andes in Ecuador and Peru. The highest number of species was collected at locality 1, though this locality is about three times smaller than locality 2b, which had a lower number of species than locality 1. However, the localities 1 and 2b had the highest number of endemic species. However, it is not significant that these species are confined to the Polylepis forest.

Of the species recorded, 72% are mainly Andean, a figure that compares well with the species with an Andean distribution (64,5%) in the Polylepis forests of the Cordillera de

Cochabamba. The majority of the Andean species are shared with the neighbouring countries Colombia (31%) and Peru (28%). A majority of the species in the Cordillera de Cochabamba was shared with adjacent countries.

Conservation

The Polylepis pauta forests at the localities 1 and 2b were seemingly large enough to fulfil their functions as forests. The condition for the area dominated by P. microphylla was poor, and it can hardly be considered a real forest. The small number of grown up P. microphylla trees created a big Polylepis grove rather than a forest. There was a small number of flowering

herbs and shrubs close to the trees. But due to the well grazed landscape, there were not many herbs left to collect. Considering the small size of the P. microphylla grove, the expected number of species to find was low.

Certain species in the Polylepis forests, definitely epiphytes, might not survive in the surrounding páramos. Some of the endemic species in this study were only found in the P.

pauta forests, but do not seem to be restricted to these forests. Many species also grow in the

páramos and along roads in the areas, but with Polylepis stands nearby. However, considering the extensive areas once covered by Polylepis forests, many species of vascular plants might already have been exterminated. Thus, initiatives to decrease negative human influence on

Polylepis forests should be taken seriously. The majority of lichens and mosses will probably

disappear if the forests do so.

Considering its limited distribution in the Andes, the Polylepis forest as such is worth conserving as a unique habitat. Saving Polylepis forests will also contribute to the

conservation of much of the diversity in the high Andes. Not only are the trees of Polylepis important to local people, Polylepis forests also contribute with shelter and protection, and some plants, especially epiphytes, and many animals depend on them. The destruction of habitats is the major cause for the decline of large mammals, such as the mountain tapir and the Andean spectacled bear.

The mountain tapir is listed as endangered and today less than 2000 individuals exist in Ecuador (Animal diversity web 2007). Living in forests and páramos at 2000 m and higher it prefers humid ecosystems and is very sensitive to habitat disturbance. It eats a wide variety of plants and rummages the ground with the nose when searching for food, making food also available for smaller herbivores and small carnivores, which feed on earthbound insects and worms. The mountain tapir and the Andean spectacled bear are both important for seed dispersals.

The Andean spectacled bear is not currently listed as endangered (Lincoln Park Zoo 2007), but the international law against commercial trade does not master illegal hunting and loss of habitat. According to a legend in 1580, the village of Oyacachi was attacked by bears and the inhabitants moved into a cave, which was considered more safe (Gente de la Biorreserva 2008). The story does not tell which kind of bears that were attacking. The Andean spectacled bear might have had a wider distribution at that time, though it seems unlikely that Andean spectacled bears would attack people. Farmers see these bears as a threat to especially corn fields, as the animals destroy parts of the plantations to eat the cobs. The spectacled bear inhabits a large range of habitats (Animal diversity web 2007), from lowland rain forest to páramos at 4200 m altitude. The spectacled bear prefers dense forest habitats and is also a good climber. It is nocturnal and during daytime it sleeps under large tree roots, between trunks or in caves. Polylepis forests with its abundant supply of large trunks and deep forest floor offer good conditions for animal nests.

There are different species of humming birds in the remnants of P. pauta forest. Rubus

coriaceus (locality 2b) was seen being visited by humming birds (pers. observ.). However, Rubus coriaceus is not a threatened species. It is common in the Andes from southern

Colombia to northern Peru (Tropicos 2007), and is not restricted to Polylepis forest. But the interaction within the ecosystem plays an important role. The loss of Polylepis forests certainly decrease nesting sites for certain species of humming birds, as well as pivotal sources of nectar. In Oyacachi, many fields are used for grazing, though the cattle are spread

out in these huge surroundings, which might decrease the degradation of the páramos and the remaining native vegetation.

Different Polylepis forests

The natural ecological limits in the high Andes are hardly visible today because of human influences (Fjeldså & Kessler 1996). The Polylepis forests in this study are located at a distance of about 250 km and at different altitudes. Polylepis pauta grow within the Oyacachi valley on slopes protected behind mountain crests, somewhat less exposed to wind than

Polylepis microphylla, which are located on a slope from the highest crest in that province,

affected by strong wind and lower temperatures. Polylepis pauta can reach a height of 12 m and the leaves are up to 7 cm long (Romoleroux 1996). Polylepis microphylla is described as a shrub or tree, and reaches a height of 7 m. In addition, its leaves are less then 2 cm long, being the smallest among the Polylepis species in Ecuador. Although the leaves are relatively small in all Polylepis species (Renison et al. 2002), the variation in leaf size is evidently linked to carrying climatic conditions. Polylepis microphylla might need more time to reach a high height compared to P. pauta. When a Polylepis tree for some reason fall or is cut down, it might leave a gap exposed for sunlight. This can favour the flora within the forest

differently, depending on the time that a new Polylepis sprout needs to become a full grown tree in the new gap. Due to the unequal collection of species of vascular plants, this study could not properly describe the difference in species competition between the forests of P.

pauta and P. microphylla.

Reforestation

In Ecuador less than 25% of the Andean forests remain. Consequently, there are plenty of areas that could be used for reforestation (Fehse et al. 2002), mostly at high altitudes near the timberline. The main threats against Polylepis forests in Ecuador are the cutting for firewood and burning for charcoal (Fjeldså & Kessler 1996), as well as the repeated burning of

surrounding páramos. Overgrazing and constant burning damages remaining forests and leads to unproductive landscapes. Competition with grasses (Renison et al. 2002) and the lack of good soil make it difficult for Polylepis seedlings to establish. Gentle grazing does not affect the tree communities, though (Cierjacks et al. 2007). The stands below the upper treeline would probably expand if human impact would decrease or stop. The present condition of the

Polylepis populations in Papallacta is not caused by natural forces. Fire can still be expected

as the most damaging factor, disturbing remaining forests and creating edges, but the

prevalent land-use in present time is cattle ranching. Grazing by a low to moderate number of cattle reduces the depth in the litter layer (Cierjacks et al. 2008), and this has a positive impact on the establishment of new seedlings. It might affect other vascular plants to become

established, including Polylepis. As a wind-pollinated genus (Schmidt-Lebuhn et al. 2007),

Polylepis probably has less opportunities to survive as single trees or groves left in páramo

dominated areas, although gene flow may occur over large distances.

Polylepis forests form a unique vegetation type, because it occurs at high altitude, normally

above the timberline in other mountain chains (Fjeldså & Kessler 1996). As a native genus, reforestation programs based on Polylepis are a good alternative in the Oyacachi area, especially compared to Eucalyptus plantations. Eucalyptus trees consume huge amounts of water and make the soils dry out (Jørgensen & Ulloa 1994), while stands of Polylepis can store the water supply (Fjeldså & Kessler 1996). The limitation of water has rarely been considered as an important limiting factor to tree growth at high altitudes in temperate and cold regions (Morales et al. 2004), though increased water supply favours tree growth.

incana, which also is present in the vicinity of Oyacachi, is well known for its use in

agroforestry and reforestation programs. Polylepis pauta seedlings are less affected by altitude, than those of P. incana (Cierjacks et al. 2007). Polylepis pauta might therefore be more suitable for reforestation programmes at higher elevations. In addition, Polylepis forests have ecological benefits. In good condition Polylepis forests increase the regeneration of new plants because the number of seedlings is higher at the inner parts of a Polylepis forest than at the outer parts (Cierjacks et al. 2007). The forests have rich soils and high production of biomass, when conditions are favourable (Fehse et al. 2002). Therefore, reforestation with

Polylepis is also a good alternative also as carbon sinks.

Further studies

To carry out a good comparative study, transects of similar sizes should be made, and some kind of abundance data collected. It would be of great value to collect also mosses and lichens which cover large parts of the Polylepis forests, inhabiting trunks. It could also be a good idea to focus on certain plant families or genera, to examine distributions, and make a more

extensive investigation of the floras within Polylepis populations in Ecuador. There are groups of plants that still are poorly collected and described, and therefore hard to identify, e.g. Arenaria and Stellaria (Caryophyllaceae). Earlier studies of birds were made within the DIVA- project and could be followed up in the vicinity of Oyacachi. It would be interesting to study hummingbirds, to make an inventory of their nests and to study which plant species that constitute their sources of nectar. The Oyacachi valley offers a diverse setting, and as a further follow-up of the DIVA project, a walking track for tourists would contribute to the villages’ ecological venture of tourism.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was carried out as a Minor Field Study (MFS), financed by the Swedish

International Development Cooperation Agency. I thank my supervisor Bertil Ståhl for good supervision and help. I thank Katya Romoleroux for giving me the opportunity to join this project, Daisy Cárate for good company and cooperation during the fieldwork, Ralf Erler, Hugo Navarrete and Philipe Keating for their help and cooperation.

REFERENCES

Animal diversity web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology 1995-2006. http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu. Accessed 13th October, 2007.

Braun, G. 1997. The use of digital methods in assessing forest patterns in an Andean

environment: the Polylepis example. Mountain Research and Development 17: 253 – 262.

Cierjacks, A., Wesche, K., Hensen, I. 2007. Potential lateral expansion of Polylepis forest

fragments in central Ecuador. Forest Ecology and Management 242: 477 – 486.

Cierjacks, A., Rühr, N. K., Wesche, K., Hensen, I. 2008. Effects of altitude and livestock on

the regeneration of two tree line forming Polylepis species in Ecuador. Plant Ecol 194: 207

– 221.

Fehse, J., Hofstede, R., Aguirre, N., Paladines, C., Kooijman, A., Sevink, J. 2002. High

altitude tropical secondary forests: a competitive carbon sink? Forest Ecology and

Management 163: 9 – 25.

Fernández Terrazas, E., Ståhl, B. 2002. Diversity and phytogeography of the vascular flora of

the Polylepis forests of the Cordillera de Cochabamba, Bolivia. Ecotropica 8: 163 – 182.

Fjeldså, J., Kessler, M. 1996. Conserving the biological diversity of Polylepis woodlands of

Gente de la Biorreserva del Cóndor, Ecuador 2008. Oyacachi y la Virgen del Quinche.

http://www.antisana.org/la_gente_oyacachi_virgen_quinche.htm. Accessed 8th June, 2008. Google Earth 2007. Google Earth Pro. http://earth.google.com/earth_pro.html Accessed 7th

June, 2007.

Jørgensen, P. M., Ulloa, U. C. 1994. Seed plants of the high Andes of Ecuador. Department of Systematic Botany, University of Aarhus, Århus.

Kessler, M. 2002. The “Polylepis problem”: where do we stand? Ecotropica 8: 97-110. Lincoln Park Zoo, Chicago 2007. Lincoln Park Zoo: Animals.

http://www.lpzoo.org/animals/factsheet.php?contentID=137. Accessed 13th October, 2007. Lippi, R. D. 2004. Tropical forest archaeology in western Pichincha, Ecuador. Case studies

in archaeology. Wadsworth/Thomson Learning, Belmont.

Mapa físico, República del Ecuador. Instituto Geográfico Militar, Ecuador 1999. Missouri Botanical Garden's VAST nomenclatural database 2007. MBG: W3Tropicos.

http://www.tropicos.org/. Accessed July 2007.

Morales, M. P., Schjellerup, I. 1997. The people and their culture. Oyacachi - people and biodiversity. DIVA, Technical Report no 2. Pages 25-57. Centre for Research on the Cultural and Biological Diversity of Andean Rainforests (DIVA). Rønde.

Morales, M. S., Villalba, R., Grau, H. R., Paolini, L. 2004. Rainfall-controlled tree growth in

high-elevation subtropical treelines. Ecology 85: 3080 – 3089.

Renison, D., Cingolani, A. M., Schinner, D. 2002. Optimizing restoration of Polylepis

australis woodlands: when, where and how to transplant seedlings to the mountains?

Ecotropica 8: 219-224.

Romoleroux, K. 1996. Rosaceae, Polylepis. Pages 71-89 in G. Harling & L. Andersson (eds.), Flora of Ecuador 56. Department of Systematic Botany, Göteborg University, Göteborg. Romoleroux, K., Cárate, D., Erler R., Navarrete, H., Keating., P. 2007. Informe anual sobre el

Proyecto ”Diversidad y extensión del bosque de Polylepis en Oyacahi, Ecuador.”

Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Quito.

Romoleroux, K., Cárate, D., Erler R., Navarrete, H. 2008. Los Bosques olvidados de los

Andes. Nuestra Ciencia No.10, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Quito.

Schmidt-Lebuhn, A. N., Seltmann, P., Kessler, M. 2007. Consequences of the pollination

system on genetic structure and patterns of species distribution in the Andean genus Polylepis (Rosaceae): a comparative study. Pl. Syst. Evol. 266: 91 – 103.

Sklenàr, P., Luteyn, L. J., Ulloa Ulloa, C., Jørgensen, P. M., Dillon, M. O. 2005.

Flora genérica de los páramos. Guía ilustrada de las plantas vasculares. The New York Botanical Garden, New York.

Skov, F. 1997. Physical setting. Oyacachi - people and biodiversity. DIVA, Technical Report no 2. Pages 8-14. Centre for Research on the Cultural and Biological Diversity of Andean Rainforests (DIVA). Rønde.

Ståhl, B., Øllgaard, B., Resl, R. 1997. Vegetation. Oyacachi - people and biodiversity. DIVA, Technical Report no 2. Pages 16-17. Centre for Research on the Cultural and Biological Diversity of Andean Rainforests (DIVA). Rønde.

The University of Texas at Austin 2007. Perry-Castañeda Library Map Collection, Ecuador

Maps. http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/americas/ecuador_veg_1973.jpg. Accessed 27th

April, 2007.

Velez, V., Cavelier, J., Devia, B. 1998. Ecological traits of the tropical treeline species

Polylepis quadrijuga (Rosaceae) in the Andes of Colombia. Journal of Tropical Ecology

Floristiska studier av fragmenterade polylepisskogar i centrala Ecuador

SAMMANFATTNING

En av världens rikaste floror finns i Sydamerika. Anderna är en relativt ung bergskedja som löper genom kontinenten. Sättningen med en ung resning av bergskedjan och ett fluktuerande tropiskt klimat har genererat en enorm mångfald av arter på och nedanför Andernas

sluttningar.

Skövling av skog i Anderna har pågått så länge människor bebott Andernas högland. Den mest kända etniska folkgruppen före den spanska koloniseringen är Inkafolket, som hade ett framgångsrikt jordbruk med sitt terrassystem, som hindrade horisontella fält från att erodera. Men spanjorerna införde sin egen teknik för att bruka jorden och Inkafolkets terrasser

övergavs. Det andinska landskap som kan beskådas idag domineras av páramos bestående av mestadels gräs. Kvarlevor av högandinsk skog som bevarats till nutid består mest av Polylepis spp., som ofta växer på otillgängliga branta sluttningar utanför den interandina platån.

Polylepis är ett släkte inom familjen Rosaceae (rosväxter) och har en begränsad utbredning till

det andinska höglandet. De växer bara där och ingen annanstans i världen. Sju Polylepis-arter finns i de ecuadorianska Anderna. Tree av dessa, Polylepis incana, P. pauta och P. sericea, finns i Oyacachidalen. På höjder mellan 3500 och 4000 meter är Polylepis den enda tillgången på virke, eftersom inga andra träslag växer där. Polylepisskogarna är vanligast på sluttningar, djupa kanjons och i raviner, ofta mellan klippblock. De flesta forskare idag tror att den högandinska vegetationen i stort sett är antropogen. Rutinen att bränna stora områden för att skapa och förbättra betesmark har reducerat polylepisskogarna till en liten del av deras ursprungliga omfattning. Polylepis är välanpassad till det hårda klimatet i Anderna.

Blommorna är reducerade till bara några millimeter i storlek (4-8 mm stora beroende på art). Dess små blad är täckta av ulliga hår. Stammens bark är tjock och grov, ett bra skydd mot nattlig frost. Återstående fragment av polylepisskogar är utspridda i ett öppet

páramolandskap, som domineras av gräs. Gränsen mellan skog och páramo är vanligtvis skarp. Dygnsvariationen hos klimatet i dessa trakter är påtaglig och varierar med höjden. En dag kan variera rejält från kall natt, till varmt mitt på dagen.

Studien utfördes från slutet av januari till mitten av mars 2007. Huvudprojektet, Diversitet och utbredning av Polylepisskogar i Oyacachi, inkluderar denna studie och kommer att fortsätta till åtminstone början av 2008. En eller fler dagar per vecka tillbringades i fält. Flest dagar behövdes till att bearbeta det insamlade materialet och skriva etiketter. Ett tillstånd utfärdat av agrikulturella institutet i Quito krävdes för varje besök i Coca-Cayambe reservatet, vid

ankomst genom vägen via Papallacta. Den resvägen är ungefär en timme kortare än vägen via Cangagua. De undersökta områdena nåddes med bil från Quito. Fältarbetet genomfördes på tre olika polylepislokaler, 1, 2a och 2b. Endast växter i blomningsstadie eller fruktbärande samlades. Växter utanför Polylepisskogen, men i anknytning till skogen samlades också. Sterila växter utelämnades helt och hållet eftersom de är svårare att identifiera och

artbestämma. Alla data lagrades i QCA herbariet, på Universidad Católica, Quito. Höjd och koordinater dokumenterades på punkter utanför och i polylepisskogen. Växterna som samlades pressades och torkades i herbariet QCA, där de även identifierades till släkte och i bästa fall art. Jag besökte även byn Achupallas i provinsen Chimborazo i södra delen av de ecuadorianska Anderna. Där samlade jag växter i vegetation dominerad av Polylepis

Vegetationen i de återstående skogarna av Polylepis pauta är tätast i skogarnas inre delar, men glesare mot gränsen till omgivande páramos. Träden är täckta av mossor, lavar och

ormbunkar, samt olika arter av klättrande kärlväxter. Kolibris observerades i skogarna och ugglor i närliggande områden. De däggdjur som kunde observeras var hjortar och kaniner. Dock syntes inga spår efter de största däggdjuren som finns i dessa trakter, bergstapir (Tapirus pinchaque) och glasögonbjörnen (Tremarctos ornatus).

Totalt 82 arter av kärlväxter insamlades i polylepisskogarna, samt ytterligare 22 arter i habitat utanför skogen. Antalet insamlade arter varierade från 16 till 36 vid varje lokal. Polylepis lokalen 2a, är belägen nedanför lokalen 2b och hade fler arter av ormbunkar än de andra lokalerna. Det enda trädslaget på samtliga lokaler i Oyacachi var Polylepis pauta och

Polylepis microphylla i Achupallas, Chimborazo. Dock förekom trädet Gaiadendron punctata

utanför en polylepisskog längs vägen mellan Papallacta och Oyacachi. De flesta arter som samlades var örter. Polylepis pauta har en utbredning i Anderna från nordöstra Ecuador till södra Peru. Huvudsakligen andinska arter dominerar samtliga Polylepis pauta skogar. 75 arter, (72 %) är begränsade till Anderna. Majoriteten av dessa, 41 arter, har en utbredning i norra Anderna (Venezuela – Peru), och 11 av dessa har samma utbredning som Polylepis

pauta. Femton arter förekommer delvis i södra delen av Anderna (Bolivia – Argentina). Bland

arter som förekommer utanför Anderna finns 20 % i Central- och Sydamerika ovanför 1000 m och högre. En ört, Gnaphalium purpureum, är introducerad till Ecuador från Kalifornien, USA. Ormbunken Pleopeltis macrocarpa förekommer även i Afrika och på Madagaskar, och Urtica

dioica, även känd som brännässla i Sverige, är kosmopolit.

Polylepislokalerna 1 och 2b hade flest endemiska arter. Totalt 19 (17,5 %) av alla insamlade

arter i denna studie är endemiska till sina habitat. Sex av dessa arter är rödlistade i Ecuador. Den undersökta Polylepis microphylla skogen är belägen nära byn Achupallas på 3655 m, i ett område dominerat av betesmark. Några äldre träd av P. microphylla skapade tillsammans en dunge, men den större delen av det som en gång var en skog bestod mest av unga träd i buskstorlek. 14 kärlväxter av de totalt 16 arter som samlades här förekom inte på lokalerna som dominerades av Polylepis pauta.

De största hoten mot polylepisskog idag är fortfarande nedhuggning för ved och kolbränning. Konstant nedbränning skadar både återstående skog och skapar oproduktiva landskap. Bete verkar dock inte vara ett större hot mot återstående polylepisskog, eftersom det är få betesdjur fördelade över stora områden. Konkurrens med gräs och saknad av god jord gör det svårt för nya polylepisplantor att etablera sig. Många kärlväxter verkar inte vara begränsade till

polylepisskogen eftersom de även förekommer ute i páramon. Det låga antalet samlade arter i denna studie berodde till stor del på den höga andelen sterila växter under insamlingstillfället. Alla samlade växter blommade eller bar frukt. Polylepislokalerna 1 och 2a hade tolv arter gemensamt, varav fyra arter var ormbunkar. Flest ormbunkar förekom på polylepislokalen 2a, möjligt beroende på lokalens läge, längst ned på en sluttning med våtare mark. Det är dock ett lågt antal ormbunkar jämfört med polylepisskogar i andra studier i Ecuador. Lokalerna 1 och 2b hade endast nio arter gemensamt, av vilka två arter är ormbunkar. Totalt hade alla

lokalerna i Oyacachi sex gemensamma arter, varav Polylepis pauta var det enda trädet. Med tanke på Polylepis begränsade utbredning i Anderna, är Polylepisskog värt att bevara som en unik livsmiljö. Förstörelse av livsmiljö är en av de största orsakerna till minskningen av stora däggdjur, till exempel bergstapiren och glasögonbjörnen. Bergstapir är rödlistad som hotad och idag finns mindre än 2000 individer kvar i Ecuador. De förekommer i skogar och páramos på 2000 m och högre, främst i fuktiga ekosystem. Bergstapiren är mycket känslig för

störning av dess livsmiljö. Glasögonbjörnen är inte hotad, men det förekommer ofta olaglig jakt. Många bönder i Anderna ogillar glasögonbjörnar eftersom de förstör deras odlingar av majs, eftersom unga kolvar är populär föda hos dessa björnar. Glasögonbjörnen föredrar täta skogar från låglänt bergsregnskog upp till páramos på 4200 m. De är nattaktiva och goda trädklättrare. De sover gärna under stora trädrötter, och polylepisskog med dess djupa ojämna markbotten erbjuder fina bohål för just glasögonbjörnar.

Det finns olika arter av kolibris i polylepisskogarna. En kolibri observerades när den besökte rosväxten Rubus coriaceus (lokal 2b). Rubus coriaceus är dock inte en begränsad art till polylepisskog i Oyacachi, men förlust av polylepisskog kan säkert minska tillgången på boplatser för vissa kolibriarter.

I Ecuador finns mindre än 25 % av de andinska skogarna kvar. Polylepis formar en unik vegetationszon, eftersom träden växer ovanför en höjd där den normala trädgränsen slutar i andra bergskedjor. Att använda Polylepis för att återplantera skog borde vara ett bra

alternativ, jämfört med Eukalyptus. Eukalyptus kräver mycket vatten och på lång sikt torkar marken ut i dessa områden, medan bestånd av Polylepis kan lagra vattentillgången i marken och bidra med mer ekologiska fördelar. Tillgången på vatten har sällan betraktats som en viktig begränsande faktor för trädens tillväxt på hög höjd i tempererade och kalla regioner, men ökad vattenförsörjning gynnar trädens tillväxt. Polylepis incana, som också förekommer i närheten av Oyacachi, är välkänd för dess användning i återskogningsprogram. Polylepis

pauta påverkas mindre av höjd än P. incana, och kan därför vara mer lämpad för återskogning

på högre höjd i Anderna. Polylepisskogarna har rika jordar och hög produktion av biomassa när förhållandena är gynnsamma. Därför är skog med Polylepis också ett bra alternativ för att sänka koldioxidhalterna.

För vidare studier skulle det vara av stort värde att samla in även mossor och lavar som täcker stora delar av polylepisskogarna. Det kan även vara en bra idé att fokusera på vissa

växtfamiljer eller släkten, att undersöka utbredning och göra en mer omfattande studie av floran inom Polylepisskogar i Ecuador. Det finns växter som fortfarande är mindre kända och obeskrivna, och därför svårare att identifiera, t ex släktena Arenaria och Stellaria

(Caryophyllaceae). Tidigare studier av fåglar gjordes inom det dansk-ecuadorianska DIVA-projektet (1995-2000) och skulle kunna följas upp i närheten av Oyacachi. Det skulle vara intressant att studera kolibrier, att inventera dess bon och undersöka vilka växter som utgör deras källor för nektar. Oyacachidalen erbjuder en mycket varierande natur och som en ytterligare uppföljning av DIVA-projektet skulle det vara ett bra initiativ att skapa en naturstig, för att bidra till Oyacachisamhällets satsning på ekologisk turism.

APPENDIX 1. List of species and their distribution.

Taxon Life

form

Voucher & Reference

Local Geographical distribution*y

Ferns

DENNSTAEDTIACEAE

Hypolepis bogotensis H. Karst. terrestrial 4375** 2B Over 2000 m alt., Costa Rica to

Peru.

Hypolepis crassa Maxon terrestrial 4309z*,

4346x**

1z, 2Ax Endemic to the Andes of Ecuador: Azuay, Napo and Tungurahua.

GRAMMITIDACEAE

Melpomene pseudonutans (H. Christ &

Rosenst.) A.R. Sm. & R.C. Moran

epiphyte 4306z*, 4343x**, 4372v**

1z, 2Ax, 2Bv Andes, Ecuador to Peru.

Terpsichore heteromorpha (Hook. &

Grev.) A.R. Sm.

epiphyte 4373** 2B Andes, Colombia to Peru.

LOMARIOPSIDACEAE

Elaphoglossum ovatum (Hook. & Grev.)

T. Moore

epiphyte 4305z*, 4345x**, 4371v**

1z, 2Ax, 2Bv Andes, Venezuela and Ecuador.

Elaphoglossum rimbachii (Sodiro) H.

Christ

epiphyte 4344** 2A Andes, Colombia to Peru.

LYCOPODIACEAE

Huperzia lindenii (Spring.) Trevis. terrestrial 4376** 2B Endemic to the Andes of Ecuador:

Carchi to Azuay.

Lycopodium crassum Humb. & Bonpl.

ex Willd.

epiphyte 4374** 2B Andes, Venezuela to Bolivia.

POLYPODIACEAE

Pleopeltis macrocarpa (Bory ex Willd.)

Kaulf.

terrestrial 4318* 2A Distributed over 1000 m alt., Mesoamerica, Caribbean and South America. Africa and Madagascar.

Polypodium mindense Sodiro terrestrial 4308v*,

4342x**

1z, 2Ax Andes, Colombia to Ecuador. Redlisted, least concern.

Polypodium monosorum Desv. terrestrial 4317* 2A Andes, Colombia to Ecuador.

PTERIDACEAE

Jamesonia scammaniae A.F. Tryon terrestrial 4307* 1 Over 2400 m alt., Costa Rica to

Peru. Angiosperms

ALSTROEMERIACEAE

Bomarea lutea Herb. herb 4362** 2B Endemic to the Andes of Ecuador:

Carchi, Napo and Pichincha. Redlisted, vulnerable.

APIACEAE

Azorella pedunculata (Spreng.) Mathias

& Constance

Taxon Life form

Voucher & Reference

Local Geographical distribution*y

Niphogeton dissecta (Benth.) J.F.

Macbr.

herb 4293* 1 Andes, Venezuela to Bolivia.

ASTERACEAE

Achyrocline alata (Kunth) DC. herb 4303* 1 Andes, throughout South

America.

Baccharis arbutifolia (Lam.) Vahl herb 4298* 1 Endemic to the Andes of Ecuador:

Carchi to Azuay. Redlisted, near threatened.

Chuquiraga jussieui J.F. Gmel. shrub 4424*** Chimborazo Andes, Venezuela to Peru.

Cotula coronopifolia L. herb,

creeper

4311* 1 California, USA and Andes, throughout South America.

Diplostephium hartwegii Hieron. herb 4303* 1 Andes, Colombia to Ecuador.

Diplostephium rupestre (Kunth) Wedd. herb 4304* 1 Andes, Colombia to Ecuador.

Gnaphalium purpureum L. herb no voucher 1 Introduced to Ecuador: Napo and

Galápagos. Native to California, USA.

Gynoxys buxifolia (Kunth) Cass. shrub 4292z*,

4393v**, no voucher x

1z, 2Bv, 2Ax Common, Andes, Ecuador to Peru.

Laestadia muscicola Wedd. herb 4301* 1 Andes, Colombia to Bolivia.

Lasiocephalus involucratus (Kunth)

Cuatrec.

shrub 4289* 1 Andes, Colombia to Ecuador.

Monticalia peruviana (Pers.) C. Jeffrey herb no voucher 1 Endemic to the Andes of Ecuador:

Carchi to Azuay.

Oritrophium peruvianum (Lam.)

Cuatrec.

herb 4302z*, 4312x**

1z, 2Ax Andes, Venezuela to Bolivia.

Senecio formosus Kunth herb,

epiphyte

4385**, 4359**

2B Andes, Venezuela to Bolivia.

BRASSICACEAE

Rorippa sp. herb 4313* 2A

BROMELIACEAE

Puya hamata L.B. Sm. herb 4381** 2B Andes, Colombia to Peru.

CARYOPHYLLACEAE

Arenaria sp. herb 4295* 1

Stellaria recurvata Willd. ex Schltdl. herb 4316x*,

4337x**, 4380v **

2Ax, 2Ax, 2Bv

Endemic to the Andes of Ecuador: Carchi to Loja. Redlisted, least concern.

CYPERACEAE

Carex pichinchensis Kunth herb 4294* 1 Andes, South America.

ERICACEAE

Cavendishia sp. shrub 4328x**,

4369v**

2Ax, 2Bv

Pernettya prostrata (Cav.) DC. shrub 4326** Oyacachi Common, over 1000 m alt.,

Taxon Life form

Voucher & Reference

Local Geographical distribution*y

Pernettya sp. shrub 4384** 2B

Vaccinium floribundum Kunth herb 4383** 2B Common, over 2000 m alt., Mesoamerica

and South America.

GENTIANACEAE

Gentianella rapunculoides

(Willd. ex Schult.) J.S. Pringle

herb 4379** 2B Andes, Colombia to Ecuador.

GERANIACEAE

Geranium stramineum Triana &

Planch.

herb 4286z*, 4296x*, 4311x*, 4378v**

1z, 2Ax, 2Bv Andes, Colombia to Chile.

GROSSULARIACEAE

Ribes andicola Jancz. shrub 4283* 1 Andes, Venezuela to Peru.

GUNNERACEAE

Gunnera magellanica Lam. herb 4364v**,

4330x**, no voucher z

2Bv, 2Ax, 1z Andes, Colombia to Argentina.

IRIDACEAE

Orthrosanthus chimboracensis

(Kunth) Baker

herb 4391** 2B Over 1500 m alt., Mesoamerica and South America.

JUNCACEAE

Luzula gigantea Desv. herb,

epiphyte

4291z*, 4363v**

1z, 2Bv Over 2500 m alt., Mesoamerica and South America.

LAMIACEAE

Salvia corrugata Vahl herb 4428*** Chimborazo Andes, Colombia to Peru.

LOASACEAE

Caiophora contorta (Desr.)

C. Presl

herb 4431*** Chimborazo Andes, throughout South America.

LORANTHACEAE

Gaiadendron punctatum (Ruiz &

Pav.) G. Don

tree KR4320** Oyacachi Common, over 1500 m alt., Costa Rica - Peru

MELASTOMATACEAE

Miconia crocea (Desr.) Naudin shrub,

small tree

4288z*, 4329x**

1z, 2Ax Andes, Colombia to Ecuador.

ONAGRACEAE

Epilobium denticulatum Ruiz &

Pav.

herb no voucher 2A Common, over 1400 m alt., Costa Rica to Argentina.

OXALIDACEAE

Oxalis lotoides Kunth herb 4310x*,

4361v**

2Ax, 2Bv Andes, Colombia to Bolivia.

POACEAE

Calamagrostis intermedia (J.

Presl) Steud.

herb 4299* 1 Common, 500 to 4700 m alt., Costa Rica to Peru.

Taxon Life form

Voucher & Reference

Local Geographical distribution*y

Calamagrostis sp. herb 4390** 2B

Neurolepis sp. herb no voucher 1

POLYGALACEAE

Monnina phillyreoides (Bonpl.) B.

Eriksen

shrub 4433*** Chimborazo Andes, Colombia to Ecuador.

POLYGONACEAE

Rumex tolimensis Wedd. herb 4274* 1 Andes of Colombia to Peru.

ROSACEAE

Acaena argentea Ruiz & Pav. herb 4415*** Chimborazo Common, Andes, throughout South

America.

Hesperomeles heterophylla (Ruiz

& Pav.) Hook.

shrub no voucher 1 Over 2000 m alt., Costa Rica to Peru.

Hesperomeles obtusifolia (Pers.)

Lindl. var. microphylla (Wedd.) Romoleroux

shrub 4382v**, 4338x**, 4341x**

2Bv, 2Ax Andes, Colombia to Peru.

Lachemilla andina (L.M. Perry)

Rothm.

herb 4416***, 4389v**

Chimborazo, 2Bv

Andes, Ecuador and Bolivia.

L. aphanoides (Mutis ex L. f.) Rothm. herb 4423***, 4331x** Chimborazo, 2Ax

Over 3000 m alt in Costa Rica. Andes, Ecuador.

L. aphanoides s.l. (Mutis ex L. f.)

Rothm.

herb 4370** 2B

L. galioides (Benth.) Rothm. herb 4332** 2A Endemic to the Andes of Ecuador.

L. hirta (L.M. Perry) Rothm. herb 4434*** Chimborazo Andes, Colombia to Ecuador.

L. holosericea (L.M. Perry) Rothm. herb 4284z*,

4314x, 4367v**

1z, 2Ax, 2Bv Andes, Colombia to Ecuador.

L. mandoniana (Wedd.) Rothm. herb no voucher Chimborazo Andes, Ecuador and Bolivia.

L. nivalis (Kunth) Rothm. herb 4368v** 1, 2Bv Endemic to the Andes of Ecuador:

Carchi to Zamora-Chinchipe.

L. rupestris (Kunth) Rothm. herb no voucher Chimborazo Endemic to the Andes of Ecuador:

Imbabura to Azuay.

Magyricarpus pinnatus (Lam.) Kuntze

herb 4422*** Chimborazo Andes, Colombia to Argentina.

Polylepis microphylla (Wedd.)

Bitter

tree 4435*** Chimborazo Endemic to the Andes of Ecuador.

Polylepis pauta Hieron. tree 4282z*,

4340x**

1z, 2Ax ** Andes, Ecuador to Peru.

Polylepis pauta Hieron. x P. sericea Wedd.

tree, hybrid

4297* 1 Endemic to the Andes of Ecuador: in Imbabura, Napo and Pichincha

Taxon Life form

Voucher & Reference

Local Geographical distribution*y

RUBIACEAE

Arcytophyllum thymifolium

(Ruiz & Pav.) Standl.

shrub 4417***, 4436***

Chimborazo Andes, Colombia to Peru.

Galium hypocarpium (L.) Endl.

ex Griseb.

herb 4366** 2B Common, over 1000 m alt., Mesoamerica and South America.

Nertera granadensis (Mutis ex

L. f.) Druce

herb 4334** 2A Over 1600 m alt., Mesoamerica, Caribbean and South America.

SCROPHULARIACEAE

Bartsia laticrenata Benth. herb 4392** 2B Endemic to the Andes of Ecuador:

Carchi to Loja.

Bartsia melampyroides (Kunth)

Benth.

herb 4437*** Chimborazo Andes, Ecuador to Bolivia.

Calceolaria ericoides Vahl herb 4420*** Chimborazo Andes, Ecuador to Peru.

Calceolaria hyssopifolia Kunth herb 4427***,

4418***

Chimborazo Endemic to the Andes of Ecuador: Carchi to Azuay.

Sibthorpia repens (L.) Kuntze herb,

epiphyte

4377** 2B Over 1300m alt., Mesoamerica and South America.

SOLANACEAE

Solanum patulum Pers. shrub 4285z*,

4388v**

1z, 2Bv Andes: Ecuador to Peru.

URTICACEAE

Urtica dioica L. herb no voucher 1 At 100 to 3500 m alt., throughout USA,

Mesoamerica. South America, Europe and Asia.

VALERIANACEAE

Valeriana microphylla Kunth herb 4287z*,

4333x**, 4360v **

1z, 2Ax, 2Bv Andes, Colombia to Peru.

*y Tropicos, Missouri Botanical Garden's VAST nomenclatural database 2007.

Romoleroux, K. 1996. Rosaceae, Lachemilla. Flora of Ecuador. No. 56. Pages 89-133.

* K. Romoleroux, D. Cárate, R. Erler, P. Keating & U. Ridbäck 2007. ** K. Romoleroux, D. Cárate & U. Ridbäck 2007.

APPENDIX 2. Species collected in páramo and their distribution.

Taxon Life

form

Voucher & Reference

Local Geographical distribution*y

Angiosperms

APIACEAE

Azorella corymbosa (Ruiz & Pav.) Pers. herb 4405**w Cayambe Andes, Colombia to Peru.

ASTERACEAE

Baccharis padifolia Hieron. herb 4319* Oyacachi Endemic to the Andes of Ecuador:

Carchi to Cotopaxi.

Diplostephium antisanense Hieron. herb no voucher Oyacachi Endemic to the Andes of Ecuador:

Pichincha, Napo, Cotopaxi and Cañar. Redlisted: Least concern.

Diplostephium glutinosum S.F. Blake herb 4410**w Cayambe Andes, Colombia to Ecuador.

Gnaphalium antennarioides DC. herb no voucher Oyacachi Endemic to the Andes of Ecuador:

Carchi to Tungurahua.

Perezia multiflora (Bonpl.) Less shrub 4412**w Cayambe Andes, Ecuador to Argentina.

Senecio comosus Sch. Bip. herb 4402**w Cayambe Andes, Ecuador to Bolivia.

BIGNONIACEAE

Eccremocarpus longiflorus Bonpl. herb,

climber

4320* Oyacachi Andes, Colombia to Peru.

BRASSICACEAE

Draba aretioides Kunth herb 4398**w Cayambe Endemic to the Andes of Ecuador:

Carchi to Azuay. Redlisted: Endangered.

CUNONIACEAE

Weinmannia glabra L. f. shrub 4322* Oyacachi Over 1000 m alt., throughout

Mesoamerica, Caribbean and South America.

FABACEAE

Vicia andicola Kunth herb 4413**w Cayambe Andes, Venezuela to Bolivia.

GENTIANACEAE

Gentiana sedifolia Kunth herb 4399**w Cayambe Over 2600 m alt., throughout

Mesoamerica and South America.

LAMIACEAE

Clinopodium nubigenum (Kunth)

Kuntze

herb no voucher Oyacachi Andes, Colombia to Peru.

ROSACEAE

Lachemilla hispidula (L.M. Perry)

Rothm.

herb 4400**w Cayambe Andes, Colombia to Bolivia.

Lachemilla jamesonii (L.M. Perry)

Rothm.

herb 4387** Oyacachi Andes, Colombia to Ecuador.

Lachemilla pectinata (Kunth) Rothm. herb 4323* Oyacachi 2300-3800 m alt., Mexico to

Bolivia.

Lachemilla rivulorum (Rothm.)

Rothm.

herb 4397**w Cayambe Andes, Ecuador to Peru.

Lachemilla tanacetifolia Rothm. herb 4396**w,

4408**w

Taxon Life form

Voucher & Reference

Local Geographical distribution*y

Lachemilla uniflora Maguire herb no voucher Oyacachi Andes, Colombia to Ecuador.

Lachemilla vulcanica (Schltdl. &

Cham.) Rydb.

herb 4409**w Cayambe 3200-4200 m alt, Mexico, Guatemala, Colombia to Bolivia.

SCROPHULARIACEAE

Calceolaria penlandii Pennell herb no voucher Oyacachi Endemic to the Andes of Ecuador:

Carchi to Cotopaxi.

Valeriana aretioides Kunth herb 4395**w Cayambe Endemic to the Andes of Ecuador:

Imbabura to Loja.

*y Tropicos, Missouri Botanical Garden's VAST nomenclatural database 2007.

Romoleroux, K. 1996. Rosaceae, Lachemilla. Flora of Ecuador. No. 56. Pages 89-133.

* K. Romoleroux, D. Cárate, R. Erler, P. Keating & U. Ridbäck 2007. ** K. Romoleroux, D. Cárate & U. Ridbäck 2007.