SA N D R A EN G ST R A N D St ate L ea rn in g a nd R ole P lay in g LUND UNIVERSITY Faculty of Social Sciences Lund Political Studies 190 ISBN 978-91-7753-618-5 ISSN 0460-0037 MALMÖ UNIVERSITY Faculty of Culture and Society Malmö Studies in Global Politics 4

State Learning and Role Playing

International environmental cooperation in the Arctic Council

SANDRA ENGSTRAND

LUND UNIVERSITY AND MALMÖ UNIVERSITY

State Learning and Role Playing

International environmental cooperation in the Arctic Council

How do states learn of environmental norms? This is the theme of this disserta-tion, which turns towards the Arctic to give an illustration. Here, the effect from global warming is big and ice-melting rapid, while economic opportunities grow as natural resources, like oil and gas, are lying increasingly bare. The theme is addressed in a case study of the Arctic Council, and more specifically through two negotiation processes dedicated to Arctic oil spill prevention and reduction of short-lived climate pollutants. It is suggested that (the potential for) international cooperation on environmental protection has its base in more things than a recognized value of environmental norms per se. The author sheds light on how interacting states, through engaging in arguing and com-munication, learn about their social roles, as well as their ‘wants’. Not only national ideas and interests are here important, but others’ expectations. In this book, it is explored how wishes to preserve its social role in a group, and to be perceived as an Arctic ‘cooperator,’ are also drivers for state learning of environmental norms.

536185

Printed by Media-T

ryck, Lund 2018 NORDIC SW

State Learning and Role Playing

International environmental cooperation in the Arctic

Council

Sandra Engstrand

Lund Political Studies 190

Malmö Studies in Global Politics 4

Copyright Sandra Engstrand

Cover photo: Jökulsárlón, Iceland (by S. Engstrand)

Lund University⏐Faculty of Social Sciences⏐Department of Political Science Malmö University⏐Faculty of Culture and Society⏐Department of Global Political Studies

ISBN, Lund University: 978-91-7753-618-5 (print), 978-91-7753-619-2 (pdf) ISBN, Malmö University: 978-91-7104-908-7 (print) 978-91-7104-909-4 (pdf) ISSN: 0460-0037

Printed in Sweden by Media-Tryck, Lund University Lund 2018

Table of Contents

Acknowledgement ... 7

1. Introduction ... 9

What the reader should expect ... 9

Situating the project ... 10

Objective, aim, and research questions ... 18

Learning in International Relations ... 20

Contributions ... 25

2. Methodology and research design ... 29

The theatrical act of cooperation ... 29

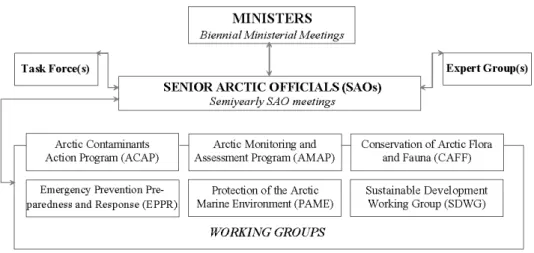

Introducing the setting: the Arctic Council ... 30

Selection of cases ... 34

Methods of text analysis and interviewing ... 37

Conclusion ... 45

3. Investigating learning by theorizing roles ... 47

States know what they want, do they? ... 47

Roles: a tracking tool for learning ... 51

Symbolic Interactionism ... 57

Learning through (common) understanding ... 60

4. Cooperation and role performance in the Arctic Council ... 65

Learning – movement with direction ... 65

Arctic Council development: three time periods ... 72

Period I – 1996-2005: Science as a regional attention maker ... 74

Period II – 2006-2013: Political cooperation ... 75

Period III – 2014-present: Cooperation under insecurity ... 78

Conclusions: on course for Arctic cooperation? ... 81

Understanding patterns of behavior as role performance ... 82

Canada – Protector ... 85

Denmark – Kid-brother realist ... 90

Iceland – Follower with ambitions ... 97

Norway – Restless know-how leader ... 101

Russia – Responsive informant ... 107

Sweden – Teacher on demand ... 113

The United States – Innate leader ... 118

The stability of roles in the Arctic Council cooperation ... 124

5. Negotiating oil spill prevention – higher expectations, lower ambitions ... 127

Preventing oil spills through an exchange of experiences ... 127

Oil pollution and AC cooperation on its prevention: a background ... 128

TFOPP: reaching a consensus through (avoiding) arguing ... 134

Common understanding on the need for cooperation ... 135

Arguing, and the many different worldviews of oil pollution prevention ... 139

Continuity and change in role performances ... 147

Confirmative role behavior by Finland and Sweden ... 147

A Canadian attempt for alter-casting? ... 148

Norwegian role incoherence, or, ‘who should do the role – is it Me or Me?’ ... 151

Conclusion: a process dedicated (to show) cooperativeness ... 153

6. Reducing black carbon and methane – high ambitions, lower expectations ... 155

The AC as oriented toward actions on emission reductions ... 155

A background on the Arctic Council’s climate change work ... 156

Introducing black carbon and methane ... 159

TFBCM: reaching a consensus through arguing ... 162

Common understanding on soot, as well as ‘staying put’ ... 162

Arguing on commitment, sector reductions, and the AC dramaturgy ... 166

Continuity and change in role performances ... 172

When Me confirms I: the leaders – Norway, Sweden and the U.S. ... 172

A problematic situation allowing for Denmark’s I to decide ... 175

Feeling misunderstood? Two territorial giants reconsidered ... 177

Conclusion: a process attentive to climate prescriptions ... 181

7. Conclusion ... 183

Roles and their uncovering potential for learning ... 184

Roles are stable, but flexible ... 185

Understanding – the mechanism activating role-flexing ... 188

The correlation between roles and learning ... 192

Learning about the Arctic environment: restrained progression ... 195

What is there to learn then? ... 200

References ... 203

List of abbreviations

AC Arctic Council

ACIA Arctic Climate Impact Assessment

AEPS Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy

AMAP Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Program

O&G Oil and Gas (industry)

PP Permanent Participant

SAO Senior Arctic Official

SLCP/-F Short-lived Climate Pollutants/-Forcers

TFBCM Task Force for Action on Black Carbon and Methane

TFOPP Task Force on Arctic Marine Oil Pollution Prevention

Acknowledgement

They say a Greenland shark could live for 400 years. Apparently, the combination of cold Arctic waters and slow motions makes wonders for longevity. While writing this dissertation, one of these fascinating and giant old-timers has hung next to me. Framed, I should say. Having her peeking at me has given a much-needed perspective on time: writing a dissertation takes time, but after all not that much time. (Oh yes, I admit, more than once I have searched high and low for an end in sight.) However, the true reason for the picture on my wall is another, much more important. Imagine, there are sharks currently swimming around that swam already in the pre-industrialized era. The speed and the consequences of human-induced climate change are in that comparison even more mind-boggling. For me, writing this dissertation, the Greenland shark has served as a personal memento on just that.

And then, all of a sudden, this book was finished. For this, I owe many people a big thank you. First of all, I am grateful to my supervisors, Mikael Spång and Rikard Bengtsson; over the years you have untiringly guided and commented, questioned and suggested, always in a constructive and friendly manner. Mikael, my main supervisor, an additional thanks to you for not only contributing with all your clever thoughts, but for genuinely caring, on different levels, for how the work has proceeded. It has meant a lot to me. A warm thanks to Karin Bäckstrand, Ole Elgström, Christian Fernandez, Maria Hedlund, Gunnhildur Lily Magnusdottir, Lisa Justesen, Johannes Stripple, and Helena Wegend Lindberg who all kindly have agreed to read drafts of this manuscript, (some of you more than once,) providing me with so many insightful comments on improvements as well as suggestions on where to take the manuscript next. A special thanks to Magnus Ericson who, in a way, started all of this; for quite some time ago, you made me start to think of perhaps someday pursue doctoral studies, and you also introduced me to teaching. Moreover, I wish to thank all my other colleagues at the Department of Global Political Studies at Malmö University, and the Department of Political Science at Lund University, for having contributed positively to this book; either by having a direct bearing on its shape and content, or by – just as importantly – being friendly and helpful people in big and small ways. Especially, I would like to mention Annika Bergman Rosamond, Josef Chaib, Emil Edenborg, Mats Fred, Peter Hallberg, Frida Hallqvist, Kristin Järvstad, Johan Modée, Tom Nilsson, Bo Petersson, Maja Povrzanovic Frykman, Jakob Skovgaard, Michael Strange, Ulrika Waaranperä, and Fariborz Zelli.

I am also grateful to Forskraftstiftelsen Theodor Adelswärds minne, which granted extra funding to conduct the interviews. Furthermore, I would like to acknowledge the people who accepted to be interviewed for the study conducted in this book; a sincere thanks to all of you for participating, and for generously sharing your thoughts and experiences.

On a personal level, thanks Eva for bringing me on vacation; Jan and Gun, for cheering me on; Jesper, for helping me to clarify some of the ‘technical stuff’; and Jonna, for caring so much. Brithel, my mother, you have always provided me with a well-needed perspective on things (and life), and this time would be no exception. Your big heart, dedicated support and, whenever needed, encouragement, have been much appreciated and of great help. Lastly, my family; August and Nils, the two of you are a constant source of joy to me, turning also bad (writing) days into good ones! (And boys, I agree; the cover picture would have looked much prettier with you on it…) Mattias, how lucky I am who have had you by my side during all of this; thanks for your company, for your comforting solution-mindedness, and for your ever-failing patience. Almost ever-failing; if not before, I knew it was time to drop the pen when even you said, “have you perhaps worked enough on that book now?” So, this specific learning experience has come to an end, and something new begins. Tack alla tre för att ni finns hos mig, och gör allting så mycket bättre.

1.Introduction

What the reader should expect

Arctic relations could have been a drama of conflicts – over resources and over territory. Due to climate change, the Arctic is rapidly getting warmer, where ice turns into water and permafrost into land erosion, and where the everyday lives of the inhabitants become increasingly difficult. Yet, due to climate change, more commercial opportunities are laying bare. Resources like oil, gas, minerals, and fish become more accessible, and possibilities for cost- and time saving maritime transportations grow as the sea ice reductions continue, turning the Arctic Ocean increasingly ice-free during summertime1 (PAME – Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment,

2009). Had the Arctic been all about material interests, it could have been a drama of states making aggressive moves in the name of sovereignty. It could have, but it is not.

The effects of climate change in the region are often epitomized as ‘the Arctic paradox:’ what is severely damaging the region from one perspective is bringing prosperity from another. The Arctic is a region where interests collide, but where cooperation – not conflicts – still guides state relations. Therefore, rather than a ‘big drama’ on conflicts, this thesis takes a point of departure in the ‘small Arctic drama’, the drama that is spelled out when interests in Arctic environmental protection are to be balanced energy interests. This is a drama symbolic of the Arctic – a region rich in oil and gas, and which furthermore takes the expression of an energy-environment intertwinement, which, often implicitly, is part of all environmental cooperation. As a drama, it is evident when the Arctic states meet to negotiate and reach a consensus on environmental protection. The good thing with interaction is that it could entail learning processes. This study is devoted precisely to these learning processes, searching for an answer to the overarching question of ‘how do states learn of environmental norms’?

The broad theme of this thesis is international cooperation, which is studied from the perspective of International Relations (IR), and in relation to the Arctic Council. The Arctic Council is an intergovernmental organization, established in 1996, which has environmental protection and sustainable development highest on its agenda

1 As early as the year 2030, or soon thereafter, it is expected that most of the Arctic will be free of sea ice

(Ottawa Declaration 1996, Art. 1(a)). The eight Arctic member states include: Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and USA. In this thesis, two different investigations are conducted: firstly, a mapping of the Arctic states’ different roles, as played out in the meetings at the Arctic Council level of Senior Arctic Officials between the years 1999 and 2016, which aim to capture the bigger pattern of development – concerning state behavior but also environmental protection. Secondly, two specific negotiation processes are investigated from a micro perspective to provide for a more in-depth understanding of how state actors learn. These negotiations have been carried out in politically appointed task forces, active between the years 2013 and 2015, and dedicated to oil pollution prevention and a reduction of emissions from short-lived climate pollutants like black carbon and methane, respectively.

Learning in this study is viewed partly as something that incorporates new scientific findings, for instance, on climate pollutants. But primarily, learning here is about how interaction shapes understanding among actors, of themselves, and others. A guiding hypothesis is that state actors are affected by the social context, and partially influenced by what is considered to be appropriate behavior in this context. Consequently, it implies that state behavior is socially changeable, rather than individualistic and static. Thus, approaching state interaction as role-playing should be suitable, where a concept like ‘role’ is understood as being reflected in a dynamic process of reflections and understanding. Roles, to paraphrase theatre, are stable over time and they follow a script, but they also have room for improvisation and are attentive to their director, co-actors, and audience. Roles, in that sense, open up for opportunities of state learning. For international relations, this would imply the potential of moving toward greater environmental protection at the expense of commercial interests. The learning approach presented in this project should be of relevance to International Relations (IR) and the research field on Global Environmental Governance (GEG).

Situating the project

At a latitude of approximately 66 degrees north (66°32'N) of the equator runs the Arctic circle.2 According to the scientific definition, once this latitude has been

crossed, one has entered into the Polar world. From this circle, the air distance to the

2 The Arctic circle is the definition used to identify eight member states of the Arctic Council. However,

this definition is somewhat narrow, not least from a climatic perspective. Other ways of defining the Arctic is through either the 10°C July isotherm, or based on the tree-line: the Arctic border is where the forests end and northern tundra begins. Compared to the Arctic Circle, both of these definitions move further south in relation to the Bering Sea, and also further south in Canada and below Greenland. (AMAP – Arctic Pollution Issues, 1997).

Norwegian North Cap – often considered the northern most point of the European mainland – measures about 670 km. From the North Cap, an additional 2,100 kilometers has to trekked before one could proclaim to have reached the North Pole.

The Arctic is a vast area, in addition to being home to four million people. It is a region that comprises cities, even big ones, like the Russian city of Murmansk, which in its heydays was home to half a million people. For most people, associations of the Arctic do not bring cities, cars, and shops to mind. Instead, it is thought to be a remote area – harsh, icy, and cold – triggering the adventurous and explorative nerve in those who look in from the outside. In 1878, the Finland-Swede Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld sailed the Northeast Passage; in 1905, the Norwegian Roald Amundsen and his expedition became the first to sail the Northwest Passage, and in 1909 (although disputed) the American Robert Peary together with four Inuit men set their feet on the North Pole.

For those approximately 500,000 indigenous people who live in the Arctic (Indigenous Peoples’ Secretariat, 2017), often in a symbiotic relationship with nature, the Arctic is not about adventure. Instead, it is about everyday life. Although the lifestyle of the Arctic indigenous people generates few sources of anthropogenic pollution, the region acts like a sink for pollutants released elsewhere but transported to the region: persistent organic pollutants (POPs), heavy metals, and radioactivity are threatening Arctic ecosystems and negatively impacting human health (AMAP –

Human Health in the Arctic, 2015). Arctic warming, in addition, impedes a traditional

way of living, for instance, for people dependent on ice for reaching hunting areas, or for those who find the thawing soil to lack sufficient bearing capacity for homes and settlements (SWIPA, 2017).

Oil spill prevention and reductions of short-lived climate pollutants, the two environmental issues studied in this thesis, are both of significant importance to the Arctic: short-lived climate pollutants since these create warming and ice-melting in a region highly adapted to the presence of ice; and oil spill prevention since energy extraction in the offshore Arctic, where a vast majority of resources are located, means a substantial risk for oil spills and methane leakages (Kakabadse, 2015; Kutepova et al., 2011). Should a spill happen, the consequences here would be more severe than accidents elsewhere in the world, due to remoteness and icy conditions that would stall rescue operations and clean-up, while sensitive ecosystems would be badly affected (PAME – Arctic Offshore Oil and Gas Guidelines, 2014; WWF, 2014). From a marine safety perspective, to reduce the probability of oil spills is therefore essential for any carried out Arctic marine operations (EPPR – Recommendations on the

Prevention of Marine Oil Pollution in the Arctic, 2013). With regard to Arctic

warming, a short-lived climate pollutant like black carbon contributes to this by absorbing sunlight, causing the ice – on top of which it lays – to melt. Methane, another short-lived climate forcer, is a potent greenhouse gas trapping heat in the atmosphere (AMAP – Arctic Climate Issues, 2015). In the Arctic, the permafrost has

started to thaw, threatening to release even more methane, amplifying climate change further (ibid; AMAP – Methane as an Arctic Climate Forcer, 2015).

Although the two issues of oil spill prevention and reduction of short-lived climate pollutants are different in nature, they are symbolically intertwined under the bigger heading of ‘climate change.’ The ‘Arctic paradox’ points to a dichotomous relationship: had oil production gone obsolete oil spills would obviously seize in existence. In addition, methane emissions and black carbon would decrease, benefitting the climate. Yet, in the Arctic Council, this is not how the issue of oil spill prevention is approached; therefore, the reader should have two different entanglements of oil spill prevention and environmental protection in mind while continuing to read: one is oil spills in relation to maritime environmental protection, and one is a more general understanding of oil spills as linked to oil extracting activities within a context of global – and not least Arctic – warming.

Arctic offshore oil and gas (O&G) extraction has been an established reality for states like Canada, Norway, Russia, and USA since the 1960s to the 80s. Russia and Norway have established themselves as global top producers regarding oil and gas, where the Arctic plays an important role. In 2008, the U.S. Geological Survey concluded an assessment of the remaining oil and gas resources in the world. The Arctic was then declared the winner, estimated as storing 20–25 percent of all yet undiscovered hydrocarbon reserves in its sediments. Thus, also well into the future, Arctic energy extraction could mean good news regarding energy security, export, and revenues for Arctic littoral states.

The Arctic drama

Not a drama on major conflicts…

The U.S. Geological Survey publication benchmarked a political shift, or rather more possible, a new Arctic rhetoric. Coalescing in time, the Arctic was described as a region becoming increasingly centered on conflicts and rivalry (Borgerson, 2008; Huebert, 2010; Posner, 2007). These predictions found nourishment in the economic possibilities that Arctic activity was believed to generate through increased transport and large reserves of resources, which is why it was assumed that territorial borders would gain in importance. Territorial claims pertaining to land in the Arctic are close to settled, but several overlapping claims exist in relation to the sea. Many of these claims do not concern ownership over water and ice, but over the seabed (Byers, 2009; 2013; Dodds and Nuttall, 2016). The most symbolic example of an ownership issue yet to be resolved is the recent claims by both Denmark and Russia, with a Canadian claim planned for 2018, to the North Pole (The Independent Barents Observer (hereafter Barents Observer), 141215; 150804; Radio Canada International, 160503). Indeed, with not all the borders fixed, the risk for geopolitical conflicts could potentially be expected (Runge Olesen, 2015).

Still, the Arctic states have adhered to international law, and their respective territorial claims have followed rules of procedure and been submitted to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (UNCLCS) for a decision. Voices predicting an Arctic scramble have also been noticeably fewer. One of the probably most vocal authors foreseeing an “Arctic meltdown,” IR-scholar Scott Borgerson (2008), later reviewed his prediction, saying: “[a] funny thing happened on the way to Arctic anarchy. […] Proving the pessimists wrong, the Arctic countries have given up on saber rattling and engaged in various impressive feats of cooperation” (2013:79). Similarly, an international project led by the Norwegian Institute for Defence Studies, GeoPolitics in the High North 2008-2012, reached the same conclusion: no race to the North in sight. ‘Interests are there,’ they said, and ‘interests differ, but carefulness and cooperation – rather than political drama – characterizes the Arctic’ (Udgaard, 2013).

A vast number of scholars devalue the risk of conflicts breaking out in the Arctic (Byers, 2013; Chater, 2016; Exner-Pirot, 2016; Heininen, 2015; Hough, 2013; Keil, 2014; Nicol and Heininen, 2014; Young, 2009; 2011). Contributing to this is a decline in the accumulated interest due to the global context and energy market (see Keil, 2014). Nonetheless, other things also have an impact, such as joint interests, Arctic kinship, and a symbolically important reference to the region as standing above turmoil. We “look forward to a long term future of peace and stability in the region,” the eight Ministers for Foreign Affairs stated, celebrating the 20th anniversary of the

Arctic Council (Joint Statement from the Arctic States, 2016). Actually, Arctic cooperation is a commitment that stretches back in time to President Gorbachev, who in 1987 held his famous Murmansk speech calling the Arctic nations to create a ‘zone of peace.’ This zone has since then been kept, anchoring states to cooperation on foremost environmental protection and sustainable development: firstly, through the Arctic Environmental Protection Strategy (AEPS) in 1991, and later through the Ottawa Declaration in 1996, which expanded institutionalization into the Arctic Council.

The voices heard a decade ago have silenced. What seems clear is that the Arctic was neither before, nor now, headed to a predestined future of conflicts. The Arctic paradox is still a paradox without a roadmap. Stories told on ice-melting as unavoidably leading toward resource rushes are precisely stories, narratives, versions of reality rather than the reality (cf. Dittmer et al., 2011; Avango, Nilsson, and Robert, 2014). However, stories can also shape reality where media optics, rhetoric, and provocative depictions could hurt stability (Bergman Rosamond, 2011:51). This is again worth keeping in mind, as the region’s geo-political situated-ness between major powers whose relations, in an international context, has deteriorated. Predictions of a conflict between foremost the U.S and Russia to spillover, or at least for the potential of a spillover, into the Arctic affairs have therefore been made (Huebert, 2016; Mearsheimer, 2015; Rahbek-Clemmensen, 2017). Yet, bearing in mind the before mentioned constructed-ness of the Arctic, the Arctic future is as

much a commodity as it is a political concept, where different actors will fight over getting to determine the outcome (Wormbs and Sörlin, 2013). If the future can be fought over, it also turns the future into something actively – not accidentally – decided upon, in parallel allowing for learning to occur. The empirical ambition and interest of this thesis fit the view of the liberal perspective on Arctic affairs as in essence prone to cooperation.

…But well a small drama of energy-environment intertwinement

Whereas cooperation acts out like a learning result on how to overcome conflicts, i.e., the ‘big’ Arctic drama, learning still has to guide this cooperation if interactive hurdles of environmental protection should be overcome. Environmental protection and reaping the benefits of various commercial activities stand in symbiotic relationships to one another, and where both are legitimized under the concept of sustainable development. On this concept, a leveling of ongoing interest occurs, where actors try to find the correct balance between its main pillars of economic, social, and environmental development.3 Yet, with ensured welfare, now and into the future,

interpreted as the goal of sustainable development, the sustainable use of environmental resource bases has an important function to fill should development occur.

When it comes to environment and economy, environment is often given a subordinated position. This seems also valid for the Arctic Council: a study conducted halfway into its cooperative performance confirmed the Arctic Council to frame oil and gas in a superior way to climate change, talking about how Arctic climate change impacted on oil and gas but not the reverse (Langhelle, Blindheim, and Øygarden, 2008:33). At the same time, if energy-environment – represented as the Arctic paradox – would be intertwined in only a one-directional manner, Arctic environmental protection could not do anything else than wait for the day that fossil fuels become dated. If, on the contrary, it is understood as a two-directional intertwinement, which this thesis suggests, then nuances could be added that have less to do with materialism and strategic thinking, and more to do with norms and appropriateness, allowing some room for potential learning to occur.

3 An important dimension here to settle, but which is outside the scope of this thesis, is whose

sustainable development is one trying to promote? The local, national, regional, and global level might not apply a shared perspective on what is to be considered a sustainable use of Arctic resources. At the same time, those who are living close to the Arctic nature are further away from the political decision-making and economic power. The inclusion of indigenous associations as Permanent Participants in the Arctic Council is an attempt to secure the local perspective to be consulted by the member states, as well as to provide for active participation by the indigenous representatives (Ottawa Declaration 1996, Art. 2).

The ‘small’ Arctic drama involves two different stories to be told. One is the story about Arctic oil and gas as resources that will be extracted,4 where, for instance, the

International Association of Oil and Gas Producers confirms the Arctic as “a top advocacy focus area” (2017). Climate change would be the other Arctic story told, where almost each year is a new record breaker concerning Arctic warming, like the year 2016: never before in our modern history had the global average temperature been as high, the Arctic as warm, its sea-ice as thin, and its spreading as limited. Further, 2017 was only slightly cooler, coming in as the second warmest year (Arctic

Report Card, 2017). The temperature rise in the Arctic has since before been

established to be more than twice that of the global average5 (Intergovernmental Panel

of Climate Change (IPCC), 2007; SWIPA, 2017). With both of these stories – or rather realities – having prominent positions within Arctic cooperation, the small Arctic drama is illustratively presented, although in disguise, in the words by former Foreign Minister Carl Bildt, who summed up Sweden’s chairmanship of the Arctic Council between 2011 and 2013 with the following call:6

Let that message from all of us here in Kiruna be loud and clear. We are committed to do whatever we can [emphasis added] to protect the fragile Arctic environment (Words of welcome, Kiruna Ministerial meeting, 2013).

This speech act is particularly interesting because within the words ‘whatever we can,’ the Arctic drama has a playing field of its own. Reaching a goal of environmental protection by doing ‘whatever we can’ may take one far, or, it may take you nowhere. For instance, the Arctic Athabaskan Community (AAC), the Inuit Circumpolar Association, and Greenpeace together with Nature and Youth have all sued their respective governments (Canada, the U.S., and Norway), for not doing enough to slow the Arctic warming. The lawsuit against the Norwegian government was explicitly directed to the decision to allow for new and expanded oil drilling in the Barents Sea7 (Earthjustice, 2013; Greenpeace, 2016a; ICC Canada, 2005; Nunatsiaq

News, 061215). ‘Whatever we can’ is a constrained promise, where more aspects than

4 This message echoed with strength at conferences for the Oil and Gas (O&G) industry (for instance,

the Arctic Oil and Gas Conference, 2014; Arctic Technology Conference, 2015; and IEA (International Energy Agency) Gas and Oil Technology, 2017).

5 Since 2011, the Arctic has been warmer than any time before (since measurements began around

1900), and its warming speed for the past 50 years has been twice as rapid as for the rest of the world. (SWIPA, 2017:3).

6 This message is sent to the whole of the world; Arctic’s sensitivity toward global warming is addressed

in the speech, where it is emphasized that it is not only important what the Arctic states are doing, but what the rest of the world equally does (Ministerial statement by Sweden, 2013).

7 The legal argument put forward was that such expanded drilling would violate Norway’s commitments

under the Paris agreement, as well as future generations’ right to safe and healthy environment (Greenpeace, 2016a).

a lived or observed environmental degradation define the frames for action. Yet, the Arctic drama has additional layers going in the opposite direction as well; oil companies like Shell, for instance, caused headlines by its decision to withdraw from the Alaskan Chuckchi Sea, after investing billions of dollars and years of work. In the Canadian Beaufort Sea, other oil companies have done the same8 (The Guardian,

150928; The Wall Street Journal, 150626). To not extend or issue new drilling leases were political decisions made by the former Obama administration in the US, as well as in Canada (The Guardian, 151016; United States-Canada Joint Arctic Leaders’ Statement, 2016). Whereas much of this could be referred to as record low oil prices making it unprofitable to drill in difficult Arctic conditions, all this is yet a result of

active decisions going contrary to what many expected: to claim that the Arctic, rich

in resources, did not automatically trigger a commercial and political activity in line with that. Environmental protection could not be ruled out as a factor changing the cost analysis – with costs here broadly understood – regarding oil extraction.

Still, the fact that states are pluralist in character – together with their contextual location – generates differing views on environmental problems. For environmental measures to be taken, it means that politics, not science, will determine an apprehended need for action: first comes politics, then science (Wormbs and Sörlin, 2013). However, views are changeable and not static, and environmental pollution and overexploitation furthermore generate consequences. To accept or not to accept these consequences is ultimately a choice resting upon values (Sörlin, 2014:213). Values, therefore, are big in the ‘small’ Arctic drama.

Approaching the Arctic as ‘a common’?

From a legal perspective, the Arctic is not much of a global common. All land is territorially linked to the Arctic states, and most of the Artic water as well. The Arctic Ocean and related waters are clearly regulated through the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Each coastal state has here the sovereign right to regulate foreign shipping within twelve nautical miles from its coast. The area between the coastline and 200 nautical miles further is the Economic Exclusive Zone (EEZ), which grants the state sole rights for fishing and resources. Outside this area, the state that can prove to the UN Commission on Delimitations of Continental Shelves, that its continental shelf continues, will be given continued right to seabed and resource extraction (UNCLOS, Art. 76). Another dimension where the Arctic is promoted as a region governed by sovereigns is in relation to the ‘Arctic exception’ as listed in Article 234. Here, coastal states are given enhanced pollution prevention powers in icy waters, despite this being beyond twelve nautical miles from the coast. However, as pointed out by Michael Byers (2013:165), with more ice turning into water, it

means more vessels from abroad will sail the Arctic waters. At the same time, Article 234 may lose its significance, should the requirement of ice no longer be fulfilled. As such, the Arctic states could potentially lose the right to claim tougher pollution regulation, while still being the closest to any accident and the consequences therefrom.

From the perspective of regional and sovereign control, there are strong incentives for Arctic states to cooperate: AC agreements on cooperation such as Aeronautical and

Maritime Search and Rescue in the Arctic (2011) and Marine Oil Pollution Preparedness and Response in the Arctic (2013) are, for instance, establishing the rules of procedure

should accidents occur at the sea, sorting out issues of responsibility as well as formally establishing a willingness to help each other out in a region where ports are at long distances. It is also important to stand united in international negotiations, for instance, on International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) the Polar Code, which was adopted in 2014 after almost two decades of negotiations. This code acknowledges that polar eco systems, and to some extent also Arctic communities, are vulnerable to ship operations, and thus strengthens the requirements for risk mitigation for those vessels that want to sail – what is described as – “inhospitable” polar waters.9

The Arctic (littoral) states’ wish for resources, control, and security turns Arctic waters into something that should be considered as little ‘common’ as possible,10

especially if one with ‘common’ stretches on to the international society. Since coastal states are entitled to claim continental shelves as extended, there is also only a small part of Arctic seabed resources to consider as ‘common heritage of mankind’ (UNCLOS, Art. 136; Byers, 2013). However, from an environmental legal perspective, a regime such as ‘common concern of humankind’ has evolved, not least in relation to climate change and biodiversity, taking things such as atmosphere, water columns, and surface/land into account. It is less circumvented than its equivalent in UNCLOS, but also more interpretative in terms of what to count as ‘common concern’ (Bartenstein, 2015:9).

Scientifically, there is a strong ecological and climatological linkage confirmed between the Arctic and the world – a warming Arctic provides for climate feedback (i.e., cause additional climate change) in three distinct ways: by reflecting less solar

9 The Polar code is also applicable to Antarctic waters. It includes greater requirements, for instance, on

ship design and ice classifications, equipment, training for the personnel, and environmental protection like pollution prevention.

10 Littoral states’ worries are foremost linked to water columns outside the EEZs, and in relation to ocean

surface beyond 12 nautical miles from the coast. Illustrative, in 2015, the coastal states agreed in a

Declaration concerning the prevention of unregulated high seas fishing in the central Arctic, not to enter

the high seas to harvest any living marine resources until science provided a sign of clearance. It has been suggested that the coastal states by such an initiative tried to protect their fishing stocks from great catches made by foreign-flagged vessels, by sending a message to the rest of the world – fishing companies and nations – to follow their example and abstain from fishing (The New York Times, 150721). As such it would be a message on ‘appropriate behavior,’ since legally, anyone has a right to fish in this part of the Arctic Ocean.

energy so more ice melts; by raising sea-levels and by altering ocean circulation patterns; and by a release of greenhouse gases as the permafrost thaws (Arctic Council – Arctic Climate Impact Assessment (ACIA), 2004). Still, the lack of real ownership renders the Arctic region to potentially suffering from a management deficit of collective resources, a problem famously known as ‘the tragedy of the commons’ (Hardin, 1968). However, with rising levels of environmental cooperation, globally as well as in the Arctic, a tragedy is an outcome that should not be considered a pre-destined necessity (cf. Feeny et al., 1990; Ostrom, 1990; Rose, 1986). The Arctic states also address responsibility – regional but also global – in relation to environmental pollution, by referring to a ‘commonality’: to ‘common Arctic issues,, to ‘common concerns, and to ‘common objectives’ (see Bartenstein, 2015; national Arctic strategies; Arctic Council declarations).

It has been suggested that as Arctic ice-melting continues, the Arctic Council should develop its role in the future: toward either a society of sovereign states, giving priority to ‘government’; toward acting like a steward for the region, prioritizing environmental ‘governance’; or toward being a regional security actor (Wilson, 2016). However, at least for now, these are dimensions all found within the AC cooperation, causing somewhat different cooperative logics: the wish to control the region and the wish to protect the region require different things from the actors. Not least in relation to learning: the more ‘commonness’ one is after, the more shared understanding one should wish interaction to bring about. Because, to achieve enhanced environmental protection and escape the tragedy of the commons, has less to do with inherited characteristics of human nature and more to do with norms and values (McCay, 1996:117). Arctic environmental pollution should therefore best be understood as a

drama of the commons (Dietz et al., 2002), where the common is both regional and

global to its scope.

Objective, aim, and research questions

The overall objective of this study is to investigate the extent to which and how learning processes in international cooperation take place. This objective is normatively anchored in a wish for Arctic environmental cooperation to be progressive. It is a wish that may prove wrong but does nonetheless represent the motif, the reason, for conducting the investigations carried out under this project. The aim, however, has nothing to do with normativity but describes learning in cooperation as processes rather than endings.

The aim has two dimensions. Firstly, (1) the thesis wants to illustrate how states that engage in negotiations and cooperation learn what their appropriate behavior would be like. With ‘appropriate,’ it is here referred to an actor’s interpretation of the social context given both perceived national interests and ideas; (perceived)

expectations from others; and what type of behavior the cooperative mandate – explicitly through terms of reference and implicitly through norms – is prescribing. In other words, it wishes to investigate how roles are developed in interactive processes. Secondly, (2) in doing so, the thesis turns toward the intertwinement of Arctic energy- and environmental interests as expressed in the Arctic Council, by analyzing two specific task force negotiation processes: the Task Force on Arctic Marine Oil Pollution Prevention (TFOPP), and the Task Force for Action on Black Carbon and Methane (TFBCM), respectively. An understanding is sought regarding how compromises on interests are made, and how these are linked to each other.

Processes of learning will be studied both at the meso-level to capture the development of the Arctic Council as well as states’ roles and role performances, and at the micro-level in task force negotiations. By conducting a reasonably detailed investigation of individuals at this latter micro-level – how they express their thoughts and experiences and how they interact within a certain negotiation setting – the project aims to reveal small-scale cognitive processes associated with learning. This implies that it is relevant to theoretically connect learning with roles. A sociologically inspired Constructivist theory like Role theory is applied in order to show how role performance is something that becomes constructed from multiple expectations: from domestic expectations on interests and norm fulfillment, on to perceptions of others’ expectations of how the role will be performed, to international norms and their demands for participation. Furthermore, a focus on role performance – rather than state behavior – directs attention toward the social setting, since the way in which actors perform, speak, and reflect stems as much from there as from ‘at home.’

Following this line of thought reveals the prospect for states to learn (part of) their role when engaged in social interaction. Any revealed changes in states’ roles and role performances are of interest, guided by the assumption that any change – behavioral or perceptive – contains a reflection which at least holds the potential for learning. By learning, two things are referred to in this thesis: (1) how states may start to redefine who they are and what they want (what their role is and how it should be played), given their social interaction and (2) the progressive shift occurring toward greater environmental protection. Learning, therefore, is the area of interest that unites both of the aims presented above.

The overarching research question of this thesis is: How do states learn of

environmental norms? This question is broken down into smaller areas of

investigation, providing different types of input. In this thesis, investigations and discussions serve to shed light on the following: how is the intertwinement between energy and environment expressed in the Arctic Council interaction, how is learning manifested within these interactive processes, how do expectations serve to either encourage or constrain learning and lastly, to what extent does a role change reveal learning?

Chapter outline

Having outlined the aim of the thesis, this chapter will continue by discussing learning: how learning fits the field of IR, in more general terms, and how learning, in this particular case, will be approached through a conceptualization of roles. The topic of chapter 2 is methodological reflections and choices of method, where roles – how to study them – will be discussed also more practically. In chapter 3, a social constructivist perspective on international relations will be applied, where the theoretical underpinnings of roles will be discussed more in depth. Arguing, understanding and norms constitute forming qualities for the way roles and learning are expressed. In chapter 4, the focus is on the performance pattern of each Arctic Council member state. Here, state behavior will be mapped according to how it has been expressed in Senior Arctic Official’s meeting. The chapter also provides role patterns with a bigger social context, where the development – and characterization – of Arctic Council cooperation will be described. In chapters 5 and 6, a micro perspective will be in focus through an investigation of the processes where state representatives attempt to reach a consensus. These chapters are interested in how consensus is reached, what social interaction does for understanding, and how social interaction may add nuances or changes to those role patterns previously mapped in chapter 4. In chapter 7, the separate analyses that have been made throughout the book will be tied together, providing the reader with some conclusions on the Arctic environmental cooperation, and how learning processes occur therein.

Learning in International Relations

To view the Arctic as a region more inclined toward cooperation rather than conflicts does not presuppose a Liberal perspective on International Relations (IR). However, when Arctic cooperation is viewed through a Realist and power-political perspective, for instance, as done by Borgerson (2013), who previously was quoted as saying that the Arctic states engaged in “impressive feats of cooperation,” the explanation to such development is yet to be found in material motifs: cooperation made it, for instance, safer and more accessible to engage in Arctic activities. It is however still national interests – fed by the rationality of economic drivers and utility maximization – that render cooperation attractive. In this thesis, the entry point to cooperation is the opposite. The interesting aspect of cooperation is where it can take actors, preferably by a shared understanding on environmental norms. Norm diffusion, perceptions of actorness (ego and alter expectations), and (prescriptive) structures are things linked to an operationalization of learning through a study of roles.

What is considered intriguing with learning, as argued by this thesis, is the movement it comprises. We end up where we end up due to something, or someone,

having activated changes in our held ideas and perceptions. So we start to think a bit differently, perhaps even in a way previously unknown to us. This is not to say that learning always takes us to better places, but it at least leaves the door open. From a theoretical perspective and for validity to hold throughout a study, the tricky thing with learning is also a major thing, i.e., to reveal its existence while moving from theory to operationalization (Checkel, 2003). To demonstrate a newly gained skill like riding a bike, building a kite, or tying your shoe laces is a type of learning that is easy to both identify and confirm. The child that can tie a shoe has obviously learned something new through what probably was laborious practicing. A distinct ‘before and after’ – bruises, untied shoes vs. unpatched jeans, neat shoe lace knot – helps to identify the break where learning has occurred. However, not all learning is that easily discovered, or as easily traced to definitive moments in time and space. Really, to learn does not even need to involve a skill but could just be a thought. For that reason, role theory is assumed to be a well-suited tool to apply, since it allows access to a state’s belief system, and how the process works to have it affected.

When studying learning in IR, the focus is on interaction acting as the generator. Of interest is not so much what actors learn but how they learn. One of the first to talk about learning within IR-theory was Karl Deutsch. To him, learning occurred through outside stimulus, and it was to be observed within organizations. Indicative of learning was how – i.e., it had to be in a new way – an organization responded to this externally delivered information and stimulus. (Deutsch, 1952:372). With outside stimulus as the inducement – together with the notion that the information delivered from the outside can be abstracted and dissociated in memory – Deutsch laid the foundation for his theory on Pluralistic Security Communities by an implicit referral to learning. Almost a half-century later, Emanuel Adler discussed these communities as cognitive security regions by referring to socializing dialogues and learning processes around normative collective knowledge (1997).

Not long after Deutsch, Ernst Haas described and predicted European integration as a process of collective learning, where an integrative spillover effect would be granted continuity through partly active and aware, and partly unaware, socialization processes (on learning, see Haas, 1990). In the 1970s, John Ruggie picked up on epistemic communities, describing them in Foucauldian wordings to represent a dominant way of looking at social reality – thereby also as a way to delimit social reality for those who are part of the group and socialized through the episteme (Ruggie, 1975:570). Peter Haas later took the concept further, focusing on how epistemic communities – networks of expert knowledge – function as coordinators between states in an increasingly complex world. Justified knowledge is produced and for policy-makers to learn from, by changing how to value “principles (normative) and causal beliefs” (Haas, 1992:35). Another source of learning in IR has been explained to be international norms, i.e., norm diffusion (Finnemore, 1996; Finnemore and Sikkink, 1998). Alexander Wendt (1999), furthermore, views

systemic change to occur only insofar as states are first capable of engaging in social learning.

However, although learning is a cornerstone in IR, it often takes on an implicit form. Socialization, integration, managing the commons, and progress are all concepts about learning although without learning necessarily touched upon per se. Also found in the literature using the word ‘learning,’ this phenomenon has been taken for granted, rather than in need of greater understanding regarding operational proceedings. Therefore, in the 21st century, there have been calls for a greater

conceptualization and methodological stringency (cf. Checkel, 2001; Hofmann, 2008; Harnisch, 2012; Knopf, 2003). Up until the mid 1990s, there seems to be a general consensus of learning as stemming from experience (Etheredge, 1981; Levy, 1994; Nye, 1987; Rose, 1991). Learning also tends to depart from an individualist methodology describing state learning and not how states learn together (see, for instance, Farkas, 1998). But if learning is going to be understood as normative rather than only adaptive, as social and shared rather than individual, a framework is needed that takes interaction into consideration while also managing to separate one actor’s beliefs from the bigger governance structure.

Jeffrey Knopf has reminded the IR community of why learning in international relations matters. It matters, he said, for potentially achieving reduced armed conflicts (2003). As a process on movement, learning is a powerful tool on normative progression benefitting humanity. Having concluded that, he handed over the relay baton to other scholars to identify mechanisms and ways in which these produce shared learning – or international learning as he labeled it. This assignment has been happily accepted by role theory, where Sebastian Harnisch, for instance, described the theory as being suitable for the task due to it being a “social theory of international politics” (Harnisch, 2012:48). Certainly, from a normative perspective on environmental protection then, international learning is a guiding light. Foremost, however, this project is a modest attempt to engage in understandings on learning processes in general, and from there shed light on how states – more specifically – learn on environmental norms.

Learning as role change – the concern of this study

To study the process of learning, how state actors learn, presupposes access to more things than the result, i.e., a behavior to observe. For that reason, role theory is considered helpful, since it opens up actors’ behavior as a deliberation between different expectations – expectations imbedded in the interactive structure, from others, and from an actor’s ego and alter. Understanding how actors learn, so the thesis argument goes, is derived from these deliberations on expectations that are made visible by a state’s different role components.

Learning is a social undertaking as well as a consequence. This implies that it is social interaction in various forms that create a need for learning. It furthermore implies that communication has an effect on how states learn. Thomas Risse’s triangle of Three Logics of Social Action (2000) is considered particularly helpful in providing a scheme for how communication – through arguing – reveals to actors which type of action-based logic to apply [figure 1]. Risse’s argument follows on Jürgen Habermas’ theory on Communicative action and views actors as truth-seekers who want to arrive at mutual understandings based upon reasoned consensus. This means that actors are open for change. Indeed, arguing is a learning mechanism, against which actors not only can evaluate interests, knowledge, and information, but where they also reflect and assess whether norms could be claimed valid enough to be considered to constitute ‘appropriate behavior’ (Risse, 2004:288). Actions guided by a logic of consequentialism try to maximize individual preferences, whereas actions based upon logic of appropriateness draw on the idea that actors try to ‘do the right thing.’ As such, this logic is primarily applied, since it is through a contestation over norms that it could be established what is meant by “good people do X,” or ‘that the right thing to do’ could be to engage in strategic bargaining (ibid, 2000:4-6).

Figure 1: Three Logics of Social Action Figure 2: Three Kinds of Learning in Social

(Thomas Risse, 2000:4) Interaction

Risse’s triangle of logic serves quite well to illustrate what learning is understood to be in this thesis, here presented as ‘Three Kinds of Learning in Social Interaction’ [figure 2]. The upper corner of the triangle acts as the driver of movement in my triangle, as in Risse’s. Ego- and alter learning is the main focus of the triangle since this is the mechanism that pushes actors in the direction of either adaptive or normative learning, just like arguing is deciding which logic to apply. As such this is not learning per se, but rather an explanation to how states learn.

Adaptive learning – 1st degree of role change

Adaptive learning correlates with the left corner of Risse’s triangle, where logic of consequentialism guides behavior. In this type of learning, an actor changes strategies to achieve something, but the actor does not change any fundamental beliefs. New information leads to a change in means but not in ends (Levy, 1994). If interaction does not manage to touch upon foreign policy goals, no reassessment of interests, behavior, and perceptions would be needed. A state’s belief-system would be kept stable. Following role theorists like Harnisch, Frank, and Maull (2011:253), adaptation, therefore, could be described as a first degree of role change, since changes in perceptions and expectations regarding ‘who they are’ would be very modest. The same goes for connecting it to environmental norms: adaptive learning of the environment does not indicate any profound changes regarding beliefs on which value to ascribe to nature.

Normative learning – 2nd degree of role change

The right corner of the triangle stands for the logic of appropriateness when it comes to action-guiding principles. Here, it is translated into normative learning, but others would call it ‘complex learning’ (cf. Levy, 1994; Nye, 1987) or ‘real learning’ (Haas, 1990). It entails a learning that is not restricted to preferences or strategies in means but rather, targets the belief-system. This learning involves aspects of changed perceptions and expectations that go deeper into values as being understood as appropriate; for instance, regarding other actors, on how to define the situation in a new way with new goals, or through a redefinition of itself as an actor.

However, if arguing leads toward normative learning, this, for sure, does not need to include learning about “good” values. It simply prescribes “good manners” – as in appropriate behavior – given those actors and structures that form the specific context. Conceptually, normative learning includes a common understanding of which social rules govern. Empirically, though, normative learning is wishing for more, concerning the common understanding, where this also should include some kind of progression ‘to the better.’ The outermost illustration of such common understanding would be found within the concept previously mentioned as ‘international learning’ (Knopf, 2003:191). Still, for any common understanding of environmental norms to develop, for instance on climate change, it needs the guidance from institutionalized expert knowledge. This brings attention to epistemic communities, and the process where organizations are “learning to learn,” or “learning to do better” (Haas, 1992; Haas and Haas, 1995). The knowledge that international organizations produce, through the episteme, is for states to respond to, learn from, and possibly even change beliefs on.

Ego and alter learning – the cog running the wheel

Ego and alter learning differs from the two learning types mentioned above in that it is the mechanism, the cog, which leads to learning in various forms. It is a type of learning that directs lights toward how actors learn, rather than what they learn. As such, it also becomes the tool to use for operationalizing learning. Following role theory, it is argued that learning happens through interaction, when actors are carrying out ego and alter reflections. It is these reflections that fill adaptation as well as normative learning with substance. As a consequence, states perform (behave) a bit differently, and possibly change perceptions regarding who they are as actors.

In order to capture how states’ learning processes are tied to the interactive structure, ‘expectations’ should be added. Expectations target different aspects of interaction: (1) the ego part of an actor (who am I as an actor and what do I therefore expect of myself), (2) the alter part of an actor (how do I as an actor interpret others’ expectations of me), (3) my held expectations of others, and finally (4) expectations of what constitutes ‘appropriate’ behavior, for instance, in a negotiation. This structure is therefore part of pushing actors’ role performances toward sometimes an appropriateness built around adaptation of means and strategies, and in other times around normative learning on beliefs and values.

Learning becomes identifiable and possible to conceptualize through the observation of some kind of role change, caused by, for instance, a conflict or an ambiguity within actors’ role conceptions (Harnisch, 2012:53). In chapter 3, roles will be conceptualized further. In addition, Habermas’ theory of communicative action (1984) will be discussed, focusing on how communication makes states aware of their roles and possible role conflicts; on how understanding affects interactive strategies; and on how consensus is reached through (sometimes) succumbing to the better argument. Included as well, is George Herbert Mead’s referral to a dialogue as spelled out within an actor – between I (where the ego-part of a role hosts) and Me (where others’ expectations are interpreted). Role theory in combination with Habermas and Mead’s theories create a sociologically inspired theoretical framework on international relations, which have been applied previously (on Habermas, see Diez and Steans, 2005; Müller, 2011; Risse, 2000; on Mead see Harnisch, 2011b, 2012; McCourt, 2012).

Contributions

For clarification purposes, the reader of this text should code this project as located within the broader framework of global environmental governance (GEG). This field aims for “planetary stewardship” by finding ways to reduce and alleviate the pressure put on the environment by the last century’s substantial population growth and

growth in economic activity (Speth and Haas, 2006). Since the global order has also become a multi-centric one – affected by many actors, such as states, non-state and private actors alike – GEG is argued to represent an opportunity for transformation of world politics (Pattberg, 2012:98). The interest is linked to regimes – how these transform, but also how they could be rendered more efficient (Humrich, 2013; Nilsson and Koivurova, 2016; Stokke, 2013; Young, 2008, 2010). Oran Young, leading scholar within the field of Arctic governance, describes what is needed in order for the global governance structure to become effective:

What is needed, for best results, are sets of rights, rules, and decision-making procedures that are not only accepted by those subject to them as proper or legitimate in principle but that also become sufficiently embedded or entrenched that key players participate in the resulting practices without thinking about the pros and cons of doing so each time they act in a manner that conforms to the relevant rights and rules (Young, 2008:21-22).

The above description calls for a socialization effect, if global environmental governance should have an imprint on international relations. Part of this socialization is that states within international relations today have to take into account what Robert Falkner (2012) describes as a “greening of international society.” To him, international society has been normatively expanded to also take global environmental responsibility into account, in parallel to prior existing norms of state sovereignty, international law, and the market. Clapp and Dauvergne describe it as “[t]he history of global environmental politics is inextricably tied to contest of ideas: battles of worldviews and discourses” (2011:45). These ideas are sent back and forth between different regimes, creating horizontal interlinkages between them that become “sites for collusion or contestation over these broader [governance] norms (Zelli, Gupta and van Asselt, 2012:176). Thus, global environmental responsibility has gained an undisputed position within the global setting on norms.

All regimes continuously change, and no regime develops in the same manner; some become stronger whereas others decline, depending on ‘endogenous factors’ such as institutional operating capabilities, on the one hand, and exogenous factors like the political and economic context (Young, 2010), on the other. A vertical interlinkage may as well impact, causing different institutions to prioritize norms (imbedded in other norms) differently: environmental norms within World Trade Organization (WTO), for instance, are faced with broader norms for promoting free trade, whereas environmental norms in the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) receive a more prioritized position (Speth and Haas, 2006:130-131). Such hierarchy is potentially found as well within the Arctic Council cooperation on sustainable development, due to interpretative space on which type of development (values) to prioritize, and which regime – climate or energy – to link up with horizontally.

A contribution through a micro-level approach

Global environmental governance is, of course, a very extensive research field and what has been said so far barely touches the surface. Yet, the small selection above serves to describe ways of reasoning, which are highly relevant to this thesis. As an intergovernmental organization, it is ultimately the states that decide within the Arctic Council, and who sign the agreements. For that reason, in this project states have been selected as the actors to be studied. Yet, much of this thesis is located in and kept close to the small, in what sociologists refer to as the micro-level. This approach has been guided by the idea that any understanding of the big picture runs through an understanding of the small. Members of an organization can, through regime interlinkage, “sometimes foster (or perhaps implicitly force) states to act outside their perceived self-interest, since there is much to gain from being understood as a reasonable actor in international settings” (Faure and Lefevere, 2011:74). This thesis wishes to present the reader with some of these bits and pieces of how this ‘fostering’ occurs, by aiming to contribute with understanding of how global environmental protection is a learning process originating in reflections, perceptions, understanding, and expectations found in the ‘small.’

A theoretical contribution on Arctic Council development

The Arctic Council has been studied quite vigorously, especially during the last few years. With an Arctic region moving more and more into centrality, attention has been given to issues such as how to move governance through the Arctic Council forward into the future (Axworthy, Koivurova, and Hasanat, 2012; Nord, 2016a, 2016b; Dodds, 2013). In a similar vein, others have investigated the possible roles that the Arctic Council can take on when the region is now being faced with increased activity and growing environmental challenges (Pederson, 2012; Wilson, 2016). Arctic Council working groups have been described as constituting the Arctic messenger for the need to acknowledge climate change (Stone, 2015); one specific role that has been suggested for the future is a ‘cognitive forerunner,’ where the Arctic Council’s use and improvement of soft power is linked to its ability to reach effectiveness (Nilsson, 2012). Moreover, Arctic environmental governance has been investigated in relation to security, and how the environmental field could represent an entry into also enhanced state security in the Arctic (Stokke, 2014).

In relation to (regime) effectiveness, the Arctic Council has been described as a complex governance system (Young, 2012; Stokke, 2013) or a fragmented governance system (i.e., Humrich, 2013), involving governing not only under sovereignty rights, but also through, for instance, EU regulation as well as UN law. Where some have pushed the need for a more all-encompassing environmental treaty or framework that to a greater extent takes into consideration the transboundary character of eco-systems (Koivurova, 2008; Koivurova and Molenaar, 2010), others link the Arctic Council success to the extent it manages to affect or be backed by other (international)

institutions (cf. Humrich, 2013; Stokke, 2011; Young, 2009). This way of reasoning highlights regime effectiveness through the dimension of interplay (i.e., interlinkages) that exists within different levels of regulation governing the Arctic. The Arctic Council has also been studied in terms of ‘good governance,’ and the extent to which it allows for indigenous peoples’ participation in norm- and decision-making (Koivurova and Heinämäki, 2006; Poto and Fornabaio, 2017).

Still, to my knowledge, no one has actually studied the Arctic Council and its development in terms of either learning or by applying role theory to better understand state behavior and preferences. In that sense, this project will apply a theory to a case not previously investigated through such a theoretical lens. This project therefore is believed to add new dimensions to the understanding of Arctic cooperation and development. The theoretical value would be to show role theory as being well suited to localize, identify, and reason about the Arctic state learning, whereas the empirical value would be enhanced knowledge of the interactive foundation for what is going on in the Arctic.

A contribution through new empirical material

The last contribution is empirical and originates from the material collected for the project. Previously, a questionnaire-survey has investigated the former Artic Council members and participants and their views on the Arctic Council being an effective governance system (Kankaanpää and Young, 2012); moreover, a recent dataset study has provided an analysis on stakeholders’ participation in AC meetings (Knecht, 2017). However, the Arctic Council development has not been studied over time through minutes from meetings between Senior Arctic Officials (SAO), at least not to the extent done in this study; in order to explain Russia’s cooperative commitment in the Arctic Council, SAOs meeting minutes have previously been analyzed during three chosen time periods (Chater, 2016). Nevertheless, meeting minutes have not been investigated altogether, nor linked to patterns of states’ role behavior.

Furthermore, the Arctic black carbon regime has been investigated in terms of mitigation effectiveness (Shapovalova, 2016), and the agreement on marine oil pollution and preparedness and response in the Arctic (2013) – an agreement resulting from a previous task force than the one studied here – has been investigated in terms of substance and governance impact (Vigeland Rottem, 2015; 2016); however, no studies have been conducted of those two task forces that are of special focus here, and certainly not from a micro perspective. Interviews have been carried out with task force participants; furthermore, these interview records play a significant role in not only providing material to analyze under role theory, but also to give an insight into the functioning of the Arctic Council.

![Figure 5 [modified by the author]: Figure 6: Three Kinds of Learning in Social Three Logics of Social Action (Risse, 2000:4) Interaction](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/5dokorg/4212368.92579/65.718.399.618.665.828/figure-modified-figure-learning-social-logics-social-interaction.webp)