Exploration of personal digital

legacy through geo-tagged

augmented reality and

slow technology

Shirwan Jassim

Interaction Design One-Year master 15 credits Spring 2017 Elisabet Nilsson FACULTY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETYACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank the following people for their support in helping to shape and drive this project forward:

Elisabet Nilsson, David Cuartielles, Maria Engberg, Kevin Ong, Gabriel Jacobi,

Ingrid Skåre, Roxana Escobedo, Raya Dimitrova, Clarissa de Oliveira,

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1. INTRODUCTION 5 1.1 Background 5 1.2 Research Question 6 1.3 Methods 7 1.4 Limitations 71.5 Expected contribution to the field 7

1.6 Paper structure 8 2. THEORY 9 2.1 Canonical examples 9 2.1.1 Facebook Memorial 10 2.1.2 Boxego 10 2.1.3 Timecard 11

2.1.4 Digital Slide Viewer 12

2.1.5 Argon 13

2.2 Legacy and culture 14

2.3 Generativity 15

2.4 Spaces vs Places & Augmented Reality 17

2.5 Slow Technology 17 2.6 Reflective Design 18 2.7 Transient applications 20 3. METHODS 21 3.1 Project plan 21 3.2 Participatory Design 22 3.3 Speculative Design 22 3.4 Cultural Probes 23 3.5 Service Design 23 3.6 Qualitative Interviewing 23 3.7 Sensitizing 23 3.8 Ethical considerations 24 4. DESIGN PROCESS 25

4.1 Mind mapping & word association 25

4.2 Participants 25

4.3 Probe kit design 26

4.3.1 Probe kit results 30

4.3.2 Probe results interpretation and design inspiration 32

4.4 Practical compromise 35

4.5 Follow-up survey 35

4.5.1 Follow-up survey results 35

4.5.2 Follow-up survey interpretation and design inspiration 36

4.6 Workshop 36

4.6.1 Workshop results 37

4.6.2 Workshop interpretations and design inspiration 39

4.8 Augmented reality application concept 42 4.9 Artifact concept 44 5. FINAL RESULTS 46 5.1 Application concept 5.1.1 AR mode 47 5.1.2 My traces 47 5.1.3 My tree 48 5.1.4 Settings 49 5.2 Trace Keeper 50

5.3 Addressing the research questions 52

6. DISCUSSION 54 6.1 Cultural probe 54 6.2 Workshop 55 6.3 Final concept 56 7. CONCLUSION 58 7.1 Future considerations 58 8. REFERENCES 60 9. APPENDIX 64 9.1 Probe test 64 9.2 Workshop questions 65 9.3 Follow-up survey 66

9.3.1 Follow-up survey results 70

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1 BackgroundIt is well-established that since the advent of the internet and the rise of smart devices and social networks, more and more of our daily communication happens in digital form. Plat-forms such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter to name a few allow us to constantly broadcast our thoughts, impressions and experience to anyone at anytime and virtually any place. The pro-gression into an increasingly digital and decentralized form of personal expression, combined with widely accessible tools and digital devices (laptops, tables, mobile phones) have the potential to generate an overwhelming amount of personal media over decades of use.

There is certainly something of value to us and those we hold dear in the potentially unwieldy “digital legacy”, namely stories. For the purpose of this paper, “digital legacy” will be defined as images, text, videos or drawings people capture with a mobile digital device. While mate-rial possessions passed down generations in forms of family heirlooms are still a very common form of legacy building, it is the stories, experiences and the person behind the possession that mattered more, as Hunter and Rowles also found in their limited study (Hunter & Rowles 2005.) Stories provide the coming generations with a narratives, experiences, ideas and thoughts that they can relate to their own lives and receive a more global perspective that stretches across time and space. Moreover, they provide clues about attitudes, moral stances, politics and their developments of a certain time and place (McAdams 2001). Adding the digi-tal realm as a form of legacy and storytelling raises new questions of how we should deal with our digital legacy. How do we preserve it? How do we curate it? Who will have access to view, contribute or possibly edit? Digital material can hypothetically live on forever, but how can our heritage survive the unstoppable evolution of technology and file formats over time?

Some attempts at capturing digital legacy are already in place. Facebook, the world’s most popular social network, allows its users to have their profile remain active after death as memorialized accounts and even relatives have limited editing capabilities (Facebook: Memori-alized accounts n.d.). Taking it one step further, the website Boxego (www.boxego.com), focus-es exclusively on digital afterlife by providing users with a place for an online journal where memories in various forms can be captured and released to select individuals at select times. The academic community has also conducted initial probes into the domain. One such attempt is documented in Technology Heirlooms? Considerations for Passing Down and Inheriting Digital

Materials (Odom et al. 2012A) where researchers created three distinct technological probes

and conducted contextual inquiries with eight families. The concept of the probes ranged from backing up tweets from family members, creating a digital family time line with text and imag-es and storing digital family photos inside a “digital slide viewer”.

A similar attempt involving some of the same researchers resulted in a prototype named

Photo-box which occasionally prints a randomly selected photo from the owners Flickr account (Odom

et al. 2012B). The Photobox invokes the concept of “slow technology” (Hallnäs & Redström 2001), which rejects the need for technology to perpetually strive for efficiency, convenience and automation.

Due time and resource restrictions, this project will focus on a specific target group, namely young adults (aged 20-35), male and female from various cultural backgrounds. This delimita-tion might in fact prove to be quite appropriate, as young adults are on the brink of entering the prime age of “generativity”, i.e. focusing energy and attention towards future generations rather than oneself (McAdams, de Saint Aubin & Logan 1993). It is also fairly safe to assume that this age group is “tech-savvy” and more open to using technology as part of their person-al legacy. I person-also chose to focus this project on digitperson-al legacy content generated more or less specifically towards posterity, rather than mining frequently used social media platforms.

1.2 Research Question

Taking a page of out Dourish and his distinction between “place” and “space” (Dourish 2006), the project will explore how geo-tagged “augmented reality” (AR) (Munnerley et al. 2012) help us can transform the outside world into places with meaning for ourselves and allow our digital legacy to be experienced in a more specific, embodied context of places. By directly or tacitly connecting our expressed thoughts, photos, videos sounds to specific places at a specific time, there might be possibility of establishing deeper connections between relatives across genera-tions, as well steer the act of creating digital materials towards a more thoughtful, deliberate activity. As Fitzgerald put it, AR has the potential to “enhance situated meaning-making.” (Fitzgerald et al. 2013, p. 47). The research questions for this project are:

1) How might a system of geo-tagged AR content for personal posterity be conceptualized, in terms of application, execution and physical form?

2) How might the “slow technology” concept serve to create more thoughtful and meaningful content for the above mentioned system?

A important aspect of this project will also be discussing technical, practical limitations and possibilities. It is not within the scope of this study to conduct a deep analysis of these issues. Rather, I will simply present some common obstacles of technological longevity.

1.3 Methods

Through interviews and workshops, I plan on investigating several possibilities for geo-tagged legacy traces through the following methods:

1) Conduct a survey using the Loyola Scale on levels of “generativity” among participants (McAdams 1993)

2) Create a “cultural probe”, which will ask participants generate personal memories of several media types, while considering the places where these are generated and finally think of who these captured memories will serve.

The manner of collection, transition and consumption of digital legacies realistically cannot be accurately assessed within the scope of this project. Deeper insights will only emerge after years upon years of real-world use. Instead, the intent of this project is to use speculative design (Auger 2013) to make initial explorations and perhaps lay groundwork for future explo-rations. In addition a version of “cultural probes” (Gaver, Dunne & Pacenti 1997), can serve as initial indicator of how/if users will engage with AR as a form of capturing memories, what type of moments will they want to pass on and gather inspiration for an initial prototype design. I also intend on employing principles of “reflective design” as interpreted by Foong & Kera (2004), allowing users flexibility and open-endedness in use, in order to gain more honest insights and allow dissection of the concept later on. Lastly, the long-term and the deliberate, infrequent nature of use of the prototype lends itself to be shaped through the lens of “slow technology” (Hallnäs & Redström 2006).

1.4 Limitations

Though I am aware of the various challenges and legal issues regarding collection and stor-age of private data through mobile application entails (Katal et al. 2013) these issues will be outside the scope of this paper. That is a decision based on the fact that the project revolves around a conceptual exploration with limited technical involvement. However, should this proj-ect be taken to the next stage in the future, those issues will be a vital part of it.

1.5 Expected contribution to the field

The contribution to the domain will be in attempting to explore how digital legacies could be experienced not from the couch in the comfort of our homes but “out in the wild” within the place of their creation. As a natural compliment, this is study will hopefully also generate relevant subquestions regarding how privacy and ethics should be treated within the scope the proposed design solution. Finally, I intend to include a chapter focusing on how this project could be taken further.

1.6 Paper structure

The structure of this paper will following the following manner:

Chapter 2 will provide the canonical examples (chapter 2.1) as well as background theory and concepts used as basis and inspiration for the exploration phase, designing the probe and the initial design concept. That will include the theory behind legacy as a concept (chapter 2.2), “generativity” (chapter 2.3), interpretation of “spaces vs. places” (chapter 2.4), “slow technol-ogy” (chapter 2.5), reflective design (chapter 2.6) and finally the concept of “transient applica-tions” (chapter 2.7).

In chapter 3 I will present the project plan (chapter 3.1) along with a brief overview of the of the methodology used throughout the process, as well as provide justification for the chosen methods and my interpretation of the methods in question for the purpose of this project. The methods include, participatory design (chapter 3.2), speculative design (chapter 3.3), “cultural probes” (chapter 3.4), “service design tools” (chapter 3.5), “qualitative interviewing” (chapter 3.6) and “sensitizing” (chapter 3.7). Furthermore, I will briefly state the ethical considerations followed throughout the project (chapter 3.8).

In Chapter 4 I will present a step-by-step progression of the design process, together with possible obstacles, special considerations and limitations. Any design process related material recorded or produced will also be found in this chapter. An introduction of participants will also be included. In addition, an analysis of the results together with thoughts on how the results inspired the final concept will be presented.

Chapter 5 will present the final concept together with appropriate illustrations and graphic mock-ups along with answers to the posed research questions.

Chapter 6 will contain a critical discussion of the design process and final concept. The evalua-tion will focus on the quality of the designed probe, participatory engagement, design concept as a whole, technical and practical feasibility.

A brief conclusion (chapter 7) stating the background, research questions, findings and evaluations will round off the paper, together with a chapter on future considerations will be provided.

2.THEORY

2.1 Canonical examples

In the past decade, digital legacy has received some attention in the academic community though mostly focusing on online memorials (Graham, Gibbs & Aceti 2013). As Odom (et al. 2012A) also notes, very little exploration has been conducted in how our digital legacy will be handled over time, across generations and multiple owners. Naturally, this is partially due to the fact that studying how digital legacies are passed on and treated over time cannot be accurately simulated. Such studies would quite literally require researchers to study the phe-nomenon in real-time, along with aging participants and data. Nevertheless, some attempts at speculating and capturing personal digital legacy are all already in progress. In this chapter I will present five examples, all with somewhat different angles on storing, creating and perpet-uating personal digital information.

2.1.1 Facebook Memorial

Facebook, as the world’s most used social network service (SNS) is closing in on 2 billion users

(Statista 2017). For the time being, Facebook is likely to be the most common form of a digital legacy any given person in the world will leave after passing on. Though Facebook is in essence a SNS platform for communication between living users, it would be hard to ignore the impact

Facebook has on digital legacy due to the sheer number of users and the size of the digital

footprint they collectively leave behind. In 2010, Facebook started to offer the relatives of a deceased user the option to memorialize the account (fig. 1) and manage the account with limited agency (Facebook 2017). The content of the profile can no longer be edited, but per-sons on the friends list of the deceased can still post text messages on the profile. In addi-tion, Facebook removes sensitive information of the deceased, such as contact information and “status updates”. The user’s profile in effect becomes a legacy time line filled with various images, videos and messages belonging to the user, living alongside posthumous communica-tion between relatives and friends.

2.1.2 Boxego

Unlike Facebook, the website Boxego (fig. 2) focuses entirely on a user’s digital assets after the user passes away. In fact, the tag-line on the home page even states “Twitter is for what you’re

doing, Facebook is for what you’ve done, Boxego is for what you want to keep.” (Boxego 2017). Boxego positions itself as a “private journal that you can use socially”. Users have the options

of keeping an online diary in form of text or video which will then be manifested in the form of a time line. Users can also choose who can view the material and how much of it. What differentiates Boxego from, for example Facebook, is the temporal aspect to the user-generated material. The so called “Future Share” options allows users to also select the time when certain materials will be available for viewing (fig. 3).

Figure 3. Screenshot of Boxego promoted functions. 2.1.3 Timecard

The Timecard (fig. 4) was a device created by a team of design researchers in 2013 (Odom et al. 2013). It functions as creativity tool that enables users to create and view chronological time-lines in the form of a interactive screen encased in a wooden rectangular box. The team deliberately chose to use wood as material for its aesthetic qualities:

We wanted the devices’ material aesthetics to, on the surface, evoke a sense of the warm qualities associated with antique or heirloom objects (e.g., veneered oak

composing an old chest compared to plastics encasing many contemporary appliances).

(Odom et al. 2012A, p. 338).

The device played the role of a technological probe, designed to investigate how participating families interacted and experienced the concept of digital artifact as a family heirloom.

In launching the probe, the design team collected interesting insights in how the family mem-bers contrasted media created specifically for the Timecard vs. media created on social media.

Timecard media was thought of as the more meaningful content by some members of the

fami-ly, as it required the author to dedicate time and effort towards creating entires specifically for future generations.

2.1.4 Digital Slide Viewer

Digital Slide Viewer (DSV) (fig. 4) is another technological probe created by the same team as Timecard. The core concept revolves around curating digital photo content that one acquires

through various devices and storing the content worth keeping in a screen-based interactive device. In essence, it is a digital photo album, and the design team acknowledges it as such. Unlike Timecard, the casing is made of plastic and the form is reminiscent of 1970s aesthetic. (Odom et al. 2012A). The digital photos are stored inside the device, but to activate a specific album one is required to insert a token, which contain the retrieval path for the album. Participants in the probe seem to find that the natural place for the DSV is to be stored away with other family heirlooms (Odom et al. 2012A). One participant also contrasted viewing photos on the DSV vs. the family computer:

“Putting our family photos and videos and all in a different folder [on our computer] doesn’t do them justice. There is so much on [our computer] that we won’t give a toss about in a year. …our photos, videos, that’s the bit that matters. ……[The devices] get away from all the clutter. …they show you care and makes you want to care for them, tend to them” (Odom et al. 2012A, p. 342).

2.1.5 Argon

The Argon project is ongoing endeavor that aims to explore various commercial and non-com-mercial uses of AR technology (Speigner et al. 2015). At the core of the Argon project is an browser that allows users to interact with elements found through the built-in-camera of the smart device. One application that the Argon technology was used for is the The Lights of Saint

Etienne project (fig. 6). Essentially, the application functions as a tour guide, allowed visitors

to explore the Saint Etienne cathedral at their own pace. Visitors are provided with an over-view map, together with possible interaction points. When activated, these interaction points reveal historical and cultural information about the cathedral, through the use of images, vid-eo, sound clips and text (Speigner et al. 2015). Most of the content is rendered in 2D, but 3D is also used when showing renderings of how the cathedral has changed over time. This project is a good example of the emerging practices within archiving communities of using technology for story-telling. Besides the variety of modalities AR offers to historical information, it is also unobtrusive and can be enjoyed by the visitor at their own pace and order. It also creates a direct link between a specific place and the information being absorbed.

2.2 Legacy and culture

Merriam-Webster defines legacy as “something transmitted by or received from an ancestor or

pre-decessor or from the past” (Merriam-Webster, 2017). This is a very broad definition that

poten-tially includes all sorts things, tangible and intangible alike. For the purpose of this project, I will use a narrower definition that focuses specifically on digital legacy a person could pass on to the next generation. That would include images, sound clips, video clips, drawings and texts messages. The content of these can range from advice, observations, story telling or simply capturing spontaneous moments.

The starting point for working with digital legacy goes back to the eternal question of “What makes life meaningful?”. Bauman contended that a meaningful life would be a life lived not thinking about death with possibilities of infusing own meaning, and that our ability as hu-mans to create communities and cultures makes such a life possible (Bauman 1992). Culture in particular, provides humans with a sense of belonging and collectiveness as it stretches be-yond any single lifespan of an individual member. Being a part of something bigger than one-self is generally considered a quite effective coping mechanism against mortality, or as Hunter suggests that it even offers a “limited form of immortality” (Hunter & Rowles 2005, p. 328). In collaboration with several other researchers, Hunter came up with three categories for legacy “biological legacy”, “material legacy” and “legacy of values” (fig. 7). It is within the latter

category of “legacy of values” that this project will mostly revolve around. As digital devices have become a very big part of our everyday lives, it only seems natural that digital technolo-gy becomes another alley for passing on personal thoughts, observations or experiences in the many modalities technology can offer.

Hunter also states that:

The process of leaving something behind, a legacy, is intimately tied up with our life story and with shaping the manner in which we are to be remembered: it is a mechanism for transmitting a resilient and enduring image of what we stood for. This drive to make life meaningful and to continue existence on some level after death can manifest itself in diverse forms and behaviors ranging from the

purposeful selection of belongings and artifacts to pass along to future generations, through the subconscious or conscious manipulation and nurturing of the memories others have of us, to donating our bodies to science. (Hunter et al. 2005, p. 328)

In particular, it is the idea of “purposeful selection” that I consider one of the central themes to this project. As previously mentioned in the introduction, very little in the world of digital legacy today deals with curating the vast amount of personal digital content, or to take it one step further, creating content specifically with intent of he of passing it onto future genera-tions.

2.3 Generativity

“Generativity” is a term coined by psychoanalyst Erik Erickson, which he defined as “primarily the concern in establishing and guiding the next generation” (Erickson 1963, p. 267). “Genera-tivity” can express itself in many forms and adults express it through transferring values, nur-turing development of children, contributing to the well-being of society through productivity and maintenance, thus insuring the continuity of generations over time (McAdams, De Saint Aubin & Logan 1993). There is a degree of altruism involved in the concept of “generativity” on both a tacit and explicit level. By the same notion, “generativity” can also be tacit or explicit. Erickson found that “generativity” grows in strength and arguably becomes more explicit all throughout a person’s life up until the middle ages (McAdams, De Saint Aubin & Logan 1993). As people descend into old age, “generativity” beings to decrease in importance. This trend could perhaps be explained by “social clock pattern”, a theory brought forth by Helson, Mitchel & Moan (1984) that states that we (at least in the western world) are expected to be the most productive in our contributions to society somewhere in the 20-30 age range. It wouldn’t be an outrageous to claim that as we grow older, we are generally expected to take our “foot off the pedal” and enjoy what’s left of our lives.

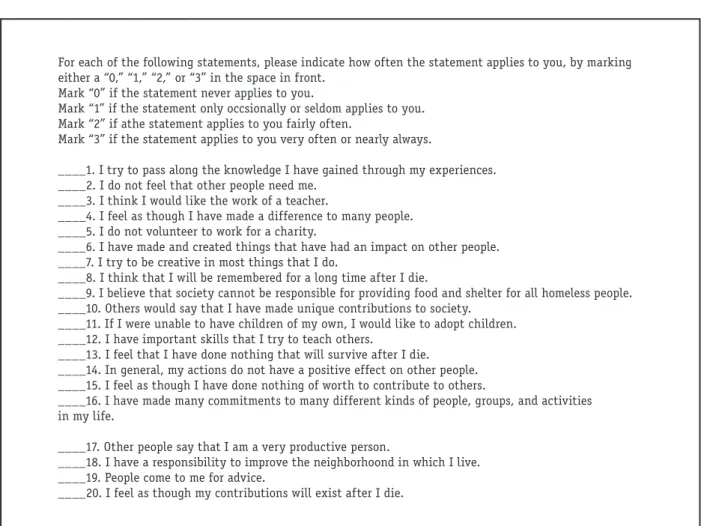

To measure the level of individual “generativity”, Erickson created a test he called the Loyola

Generativity Scale (LGS) (McAdams, de Saint Aubin & Logan 1993) (fig. 8). In essence, it is a

series of questions, with both positive and negative connotations that the participants answer by writing a “zero” for “never applies to me” to a “three” - “applies to me very often or nearly always”. The numbers are later added up to a “generativity” score. The higher score, the higher level of “generativity” found in the participant.

For this project, “generativity” serves a dual purpose. First, the participants in the prepared “conceptual probe” will have an opportunity to test their generativity through a modified version of LGS. I do not intend to use the test in a scientific manner. Rather it will be used to facilitate discussion about digital legacy and legacy of values in the evaluation phase of the workshop. At the same time, it is intended to help the participants explore their own thoughts and feelings around “generativity”, altruism and thinking ahead about familial future genera-tions. Secondly, the concept of “generativity” will serve as inspiration for the proposed design solution.

For each of the following statements, please indicate how often the statement applies to you, by marking either a “0,” “1,” “2,” or “3” in the space in front.

Mark “0” if the statement never applies to you.

Mark “1” if the statement only occsionally or seldom applies to you. Mark “2” if athe statement applies to you fairly often.

Mark “3” if the statement applies to you very often or nearly always.

____1. I try to pass along the knowledge I have gained through my experiences. ____2. I do not feel that other people need me.

____3. I think I would like the work of a teacher.

____4. I feel as though I have made a difference to many people. ____5. I do not volunteer to work for a charity.

____6. I have made and created things that have had an impact on other people. ____7. I try to be creative in most things that I do.

____8. I think that I will be remembered for a long time after I die.

____9. I believe that society cannot be responsible for providing food and shelter for all homeless people. ____10. Others would say that I have made unique contributions to society.

____11. If I were unable to have children of my own, I would like to adopt children. ____12. I have important skills that I try to teach others.

____13. I feel that I have done nothing that will survive after I die. ____14. In general, my actions do not have a positive effect on other people. ____15. I feel as though I have done nothing of worth to contribute to others.

____16. I have made many commitments to many different kinds of people, groups, and activities in my life.

____17. Other people say that I am a very productive person.

____18. I have a responsibility to improve the neighborhoond in which I live. ____19. People come to me for advice.

____20. I feel as though my contributions will exist after I die.

2.4 Spaces vs Places & Augmented Reality

In 2006, Paul Dourish stated that:

Where “space” describes geometrical arrangements that might structure, constrain, and enable certain forms of movement and interaction, “place” denotes the ways in which settings acquire recognizable and persistent social meaning in the course of interaction. The catch-phrase was: “space is the opportunity; place is the (understood) reality.” (Dourish 2006, p. 299)

Dourish is quick to note that this definition is not a unique insight, as it builds on previ-ous research and that other researchers came up with similar notions around the same time (Dourish 2006). Nevertheless, I find the idea of transforming a “space” into a “place” through digital making meaning, social interactions and personal expression offers great opportuni-ties for emerging technologies such as AR. Opportuniopportuni-ties of unobtrusive, personal and private expressions, left at a specific places for others or oneself, for the immediate future or the next generation. The same place can also mean different things for different people, depending on what an individual experiences, their state of mind, company they were in, and so on. Applying Dourish’s concept of space vs. place as we as Kling’s layer-cake model, of the digital realm add-ing a layer of interaction and experiences on top of existadd-ing ones (Kladd-ing et al. 2000), one can begin to imagine transformations of seemingly mundane every day places, such as for example a bus stop. A bus stop is already a place where one occasionally engages in impromptu con-versations over a mutual observation (“the bus is late”, “isn’t the weather nice/awful)”. It can also become a personal, meaningful place where many thoughts and feelings emerge as one awaits the arrival of the bus. The waiting time alone can transform the bus stop into a place of reflection. Over time, a person collects more and more of these places with meaning. When put together, these places can reveal patterns and deeply personal experiences, which together forms a personal life story. McAdams argues that constructing the story of our life is very much tied up in shaping our identity. Each person sees themselves as a protagonist in their own film, while the rest of the world provides the scenery, situations and characters (McAdams 1993). Our own life stories and the stories of others we feel connected to, can be a way for us to find our own place in the world and make sense of our existence.

2.5 Slow Technology

Much of the consumer-level technological progress today is centered around efficiency and con-venience. Our digital devices, for example mobile phones and tables, are constantly evaluated on the ability to handle complex operations and the speed/reliability with which the devices are able to perform them. We also except our devices to work anywhere and anytime, which in turn guides our use of social media platforms and how we connect and communicate with our

circle of “followers” and the world in general. Hallnäs suggests that while this is a perfectly reasonable way to approach design and technology in some areas, new kinds of uses for tech-nology demand that we sometimes re-evaluate our approach (Hallnäs & Redström, 2001). That becomes especially true if one is to use technology in a more deliberate, reflective way. Hall-näs brings up a clever example, when he states that:

We can compare this with the use of a chair: designing only for the situation when a person is actually sitting down is quite different from designing for the long periods of time during which people only sometimes sit down in the chair, when the chair is used as a part of the environment. The second case implies that not only the affordance of being able to sit upon is of relevance, but also the aesthetics of its design, its integration with the rest of the environment, etc. (Hallnäs & Redström 2001, p. 201)

So what is the essence of designing for interactions that are not built for maximum efficien-cy and convenience? Hallnäs suggests that part of the solution should be technology that is “slow in nature” (Hallnäs & Redström 2001, p. 202). The notion of technology slow in nature, or “slow technology” is very much supported in spirit and potential use cases of this project. At the surface, using mobile phones for slower, more reflective use may seem contradictory as mobile phones are more or less staples of ubiquitous computing and instant online access. However, the temporal aspect of only selectively using the phone, specifically for creating digital legacy for posterity, embodies the spirit of slow technology. It requires some effort to produce, which in turn requires deliberation and reflection over one’s own actions, thoughts and motivations. It is also disconnected from the immediate reward systems present in today’s social media platforms (i.e. “likes, “re-tweets”, follower numbers) and therefore invites other types motivations for producing content. There is also the opportunity of setting limitations on when and where the content could be consumed, which can potentially increase anticipa-tion and value for the recipient. As a result, slow technology could provide users with more meaningful and deliberately chosen type of content. This is in contrast to social media applica-tions that tend to decentralize personal digital content across many platforms, which in turns leads to less control over content and gradual decrease of perceived future value (Odom et al. 2013).

2.6 Reflective Design

“Reflective design” is not practice unto itself, but rather a mixture of several disciplines rang-ing from participatory to critical design (Foong & Kera 2008). It takes elements of user driven, open-ended processes and combines it with a critical and reflective outlook on technology uses, context, and our relationship with these over time. In other words, it’s not just about

what a technology does and what we use it for, but also how it makes us feel and how it fits into our entire life span. As a result, “reflective design” is also very much about challenging our views on technology and the context in which we apply it (Foong & Kera 2008). As Foong and Kera also point out, Sengers et al put it eloquently when stating that reflective design is good way of avoiding “unwittingly propagating the values and assumptions that underlie our technical practices throughout our culture” (Sengers et al. 2005. p. 49).

The different “reflective design” strategies as propose in Applying Reflective Design to Digital

Memorials by Foong & Kera (2008) are as follows: 1. Provide for interpretive flexibility

Users should be provided with necessary tools to help them understand how a technology functions and what it does, though what they want to do with said technology should be left up to the user. They should have the final say on how they create meaning for themselves through the artifact.

2. Give users license to participate

I interpret this strategy in a few different ways. First, adjusting the barrier of entry to the users in order not to dissuade them with difficult execution. Additionally, it might require “sensitizing” the users to get them into the desired state of mind (chapter 3.7). That could potentially mean, adding an element of familiarity or presenting the unfamiliar and letting the users mediate on the presented information before increasing the cognitive load.

3. Provide dynamic feedback to users

Users want to feel the effect and meaning of their actions or confusion, uncertainty and ul-timately mistrust towards technology will grow. This could be a tough criteria to follow when dealing with a concept that removes instant gratification and short-term social reward mech-anisms. However, I believe that presenting users with a paradigm that focuses on carefully curated and thoughtful digital content can produce more valuable experience in the long run.

4. Inspire rich feedback from users

Empowering the users with decision-making capabilities will hopefully motivate users to eval-uate the technology from their own point of view, separate from the designer. As result users become co-creators and steer the direction of the concept along with the designer.

5. Build technology as a probe

Rather than using known needs and wants as a starting point for building tech, technology could be built on assumptions or a specific “what if?” question. The users might then inform the design process or produce further questions. One the questions could quite possibly be “Should this be built in the first place?”.

6. Invert metaphors and cross boundaries

The last strategy revolves around designing for contexts and situations currently undesigned for, or challenge traditional uses and views of technology. This project is firmly rooted in the latter, as its feasibility could partially depend on taking a opposing stance on longevity of technology.

2.7 Transient applications

“Transient” applications are applications that are used infrequently, and therefore should be very simple and easily to use so that the user does not to spend a great deal of time on re-learning how to use it (Cooper, Reimann & Cronin 2014). The concept can be quite useful for a designing an application for sporadic use over a life time.

3.METHODS

3.1 Project planThe project spanned a total of 9 weeks, from March 27 to May 24, 2017. In this chapter, I will briefly detail the different stages of the project progression.

RESEARCH PHASE CULTURAL PROBE Theoretical background Establishing research goals

+

+

+

+

+

Technological possibilities Finding appropriate tools for usersDesign methodologies Recruiting Participants Ethical considerations

PROBE DEPLOYMENT & WORSHOP PREPARATION

WORKSHOP CONCEPTUAL EXPLORATION DISCUSSION Generating evaluation questions Group Ideation Concept

iteration MaterializingSketching &

Critical evaluation of

design concept considerationsFuture Brainstorming probe artifacts for worksop

Qualitative interviews

Synthesis & Analysis of workshop material

+

+

+

+

STAGE 1 STAGE 2 STAGE 3 STAGE 4 STAGE 5 STAGE 63.2 Participatory Design

In order to acquire insights on “generativity”, user behavior, contexts of use and attitudes towards the design proposition of this project, participatory design (PD) is pretty much a given. PD offers an opportunity to shift focus from designing for users to designing with users (B.N. Sanders 2002). Including the users in the design process is crucial to designing for experience, as experiences materialize from feelings, dreams and sometimes tacit needs that are probably impossible to pinpoint out of context by designers alone (Vaajakallio & Mattelmä-ki 2014). During the duration of this project, PD will be used during the evaluation workshop with participants (stage 4 in fig. 9). They will get to present the results of their probes, talk about their general attitude and feelings towards the experience prototype, and provide design suggestions around provided artifacts.

3.3 Speculative Design

Situated between emerging scientific discourse and material culture, speculative design operates in an ambivalent space; it typically focuses on the domestication of up-and coming ideas in the sciences and applied technology. It is concerned with the projection of socio-technical trends, developing scenarios of product roles in new use contexts. It is linked to futures, scenario building and technoscientific research. It is characterized by its inquiry into advancing science and technology. It aims to broaden the contexts and applications of work carried out in laboratories and show them in everyday contexts.

(Malpass 2013, p.338)

Malpass’s definition of “speculative design” explains very clearly why the approach is rele-vant to this project. As I am exploring a fairly recent, mainstream technology (AR) in tandem with a fairly recent, mainstream phenomenon (digital legacy) some of the uses and effects have become fairly apparent. AR is unsurprisingly being applied to tourism, education (Kysela & Štorková 2015) and marketing (Azuma 1997). Digital legacy is heavily researched topic in academia, mostly dealing with handling of postmortem data (Graham, Gibbs & Aceti 2013). With that in mind, there is a need for this project to turn towards the unknown and the imag-ination. “Speculative design”, which is a close cousin to “critical design”, “design fiction” and “design probes” (Auger 2013) is a way for designers to ideate on how emerging tech such as AR could be used to envision possible futures, beyond commercial and educational use. How will people relate to the idea of leaving geo-tagged digital traces out in the world? Do they even think about future familial generations? And if so, would people today want to present them-selves to them, possibly revealing sensitive information that they may regret later? According to Auger, the speculation could also be helped by a slight provocation and use of universal themes, such as life and death (Auger 2013). Though not the focus of this project, death and

immortality is certainly is part of this project’s scope. Apart from the altruistic opportunities of passing on stories, advice, wisdom and familial connections, there is also the notion of potentially crafting a certain form of immortality through a digital afterlife.

3.4 Cultural Probes

Inspired by the Situationists, “cultural probes” were introduced by Gaver, Dunne & Pacenti (1999). The concept has now become more or less a staple of the designers tool kit, though the originators feel it has been misunderstood and misused in other iterations (Gaver et al. 2004). I don’t entirely agree with Gaver on that point, as I think appropriation of methods and techniques is natural occurrence in the world design and innovation in general. So I will just propose that the probe (stage 2 in fig. 9) in this project will be inspired by Gaver’s approach , if not completely following the spirit of it. The choice to use cultural probes for this project is partially a pragmatic one. Because of time constraints, the participants for the probe will be fellow students, who in turn will be busy with their own work. A probe will allow them to become familiar with the project on their own time at their own pace. Beyond pragmatism, that time and space will facilitate “sensitizing” the participants to the concept of the project (chapter 3.7). Participants won’t have to come into the follow-up workshop completely “cold”, and have hopefully already started forming own thoughts and opinions during the week spent together with the probe.

3.5 Service Design

As the project deals with AR and mobile devices, I will also be using various methods out of the service design toolkit (Service Design n.d.). This will include mock-ups, mood boards, mind maps, affinity mapping and digital prototyping to name a few. Group ideation with partici-pants will be employed during the workshop at stage 4 in the project plan.

3.6 Qualitative Interviewing

During the workshop, I also intend to conduct “qualitative interviewing” as defined by

Myers & Newman (2007). The interviews will be in group format and conducted in a semi-struc-tured manner. The semi-strucsemi-struc-tured format is chosen because of the need to create an informal atmosphere, as well getting the participants to open up to potentially personal subject mat-ters and discussions. 7-10 days, will have passed between the deployment of the probe and when the workshop takes place.

3.7 Sensitizing

“Sensitizing” is a design research method where the participants are provided with material related to the workshop prior to conducting the actual workshop (Sanders & Stappers 2012). This can be for example a creative assignment or a questionnaire that helps the participants to warm up for the coming workshop activity.

3.8 Ethical considerations

While working with participants I intend to follow the ethical principles provided by

Vetenskapsrådet (Vetenskapsrådet 2002), which covers the following: transparency about the

purpose of the research, informing what the collected data will be used for, and that partici-pants are volunteers have the option to remove themselves from the collaboration at any point for any reason.

4. DESIGN PROCESS

4.1 Mind mapping & word association

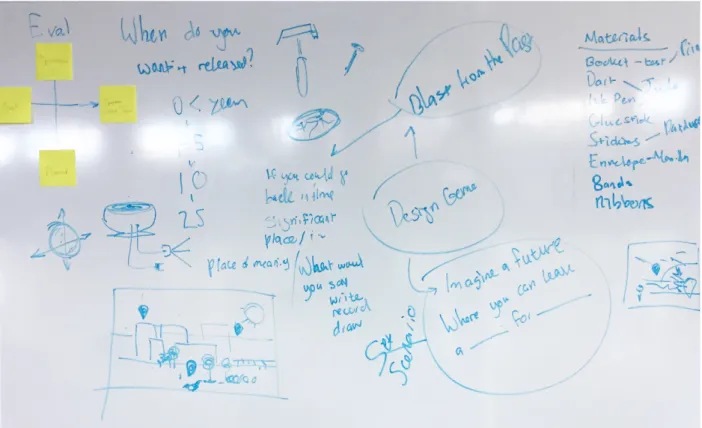

As with any subject of a unfamiliar nature, I began the process by trying to form connections between concepts (fig. 10) by creating a very simple mind map (Service Design Tools n.d.). This was done to instigate my internal processing around the concept of digital legacy and augmented reality technology, mapping out possible temporal variables, participants and state of-the-art examples. It helped me externalize the various concepts and attributes connected to the project and form a tacit vision for its direction.

4.2 Participants

Due to time restrictions, the participants recruited for the workshop came from my immediate circle of friends. All participants were studying the Masters of Interaction Design program at Malmö University. None of them were too familiar with the project in advance. At best, a few of them were vaguely familiar with my basic premise of working with AR and digital legacy. The pool of participants included two males and four females, aged between 23 and 32. Country of origins included USA, Brazil, Mexico and Bulgaria. For future reference, each participant was assigned a identifying element in form of a letter for gender (ex. “M” for male) and a number (fig. 18).

4.3 Probe kit design

The first step in the design process was the task of designing a probe kit. The probe was chosen as a method for two reasons: 1) The probe was to serve as mostly an inspiration for the ideation process much like Gaver,Dunne & Pacenti did in their exploration in 1999. 2) The probe was used as a “sensitizing” tool for the upcoming workshop (Sanders & Stappers 2012). It was to be left with participants over a period of 7-10 days, just enough to provoke and trig-ger a reflective process around “generativity”, digital legacy and the transference of it.

Another mind map (fig. 11) centering around the design of the cultural probe was created. It included thoughts on possible roles of the probe, ranging from inspiring, investigative and even slightly provocative. Potential addressees were mapped out along with overall feel of the package. Though the probe would include the aforementioned Loyola Generativity Test (LGS), I wanted to avoid making the content too clinical and formal. I anticipated a more open and forthcoming response from participants if they felt a genuine interest in their thoughts and feelings rather than being part of cold, empirical study. Therefore I opted for a more informal approach with a slightly “off-beat” and surprising presentation.

Moving forward, an exploration of the selection of appropriate objects and tools for the kit began (fig. 12, 14). Some unused ideas seen on the board included providing vials into which participants could place their notes and thoughts or nailing the location of events onto print-ed maps gluprint-ed to wooden plates (fig. 13). I wantprint-ed to include several, slightly unusual and very physical methods of answering the given tasks. The physicality was to be symbolic of

Figure 12. Exploration of objects to be included in cultural probe.

the effort one exerts in creating deliberately made digital content versus. the more common, instant and easy ways available through social media applications. For safety and budgetary reasons these ideas were discarded. Drawing from previously created mind maps, I decided to have the probe kit include a LGS test, and two cards labeled “past” and “future”. The purpose and use of these will be explained further down.

Figure 15. Screenshots of Probe aesthetics moodboard.

Once the objects and tools for the kit were selected, I began the process of choosing the ap-propriate graphical aesthetic. Using the Pinterest web site, a moodboard was created (fig. 15) (Service Design Tools) and served as initial inspiration for the general graphic aesthetics for the package. I wanted the graphical identity to have the a feel matching the “foggy” approach of the probe. The collection of images included typographical elements, communication tools, illustrations and tangentially related things such as age rings on trees or cremation urn.

Figure 16A. Cultural probe kit.

Figure 16B. Maps on the back of the “future” and “past“ cards. Figure 17. Loyala generativity test.

The final kit (fig. 16A) included the following items:

1) Manila envelope with participants name on the front. 2) The LGS test on one continuous scroll (fig. 17). 3) A sharp dart.

4) Instructions for participants. 5) Consent form (app. 9.4). 6) A4 for filling bio data.

7) Two cards, labeled “past” and “future”. 8) Stickers

9) Sticky notes 10) Pen.

The kit’s final form was decided by several factors involving budget, time alloted for creation and time alloted to participants for completion. I used some of the aforementioned principles of “reflective design” (chapter 2.6), by keeping the kit fairly open to interpretation and giving the participants agency to use the tools as they saw fit. Though the kit was to stay with the participants for over a week, the total time spent was calculated to be around 1 hour, depend-ing on the level of personal effort the participants chose to invest in the probe. The LGS test was shortened to nine questions in interest of cutting down on completion time for the par-ticipants. The chosen questions had different connotations ranging from positive to neutral to negative (app. 9.1). Rather than answering with assigning points to the questions, the answer portion was designed in form of a target which participants were urged to poke through with the dart. One reason for that was to add an element of permanence to the answer, hopefully urging participants to consider their answer more carefully. The other reason was to add infor-mality and a sense of fun to the survey. The participants were also instructed to fill out their biological data in form of age, gender and country of origin. The card labeled “future” asked participants to send any form of digital content (image, text, video) to an addressee of their choice, while pretending that the content would not be revealed until 10 years later. The card labeled “past” had the map of the entire world on the back. It would entice the participants to think back on a meaningful event or thought from the past that they wanted to communicate. Participants could use the included color dots to mark on the maps (fig. 16B) where the loca-tions where the content was created. In addition, participants were presented with the option of sending captured digital content to the researcher.

4.3.1 Probe kit results

The participants returned the kits after approximately 10 days. All of them were able to com-plete the LGS test without trouble (fig. 19, 20). However, not all the future/past cards were completed. Three of the participants only completed one card. Reasons cited were being occu-pied with work, own projects or that they simply forgot about it. The possible improvements and analysis of the probe format will be discussed in chapter 6.1.

The following results were gathered from the LGS test (fig. 21):

The maximum score for the LGS test was 36. For positively worded questions (i.e. “I try to pass along the knowledge I’ve gained through my experience”)(app. 9.1) four points were given for bullseye and zero for perforating the answer sheet outside of the target. For negatively worded questions (i.e. “I do not feel that other people need me”), the points were given in inverse. Interestingly enough, the youngest participant M1 had the lowest generativity score, while the oldest F4, had the highest. In general, females seemed to receive a higher score than the males. Though in no way indicative of any strong correlation for such a informal and small sample size, it was at the very least noteworthy. All six participants scored themselves at

Figure 19. Returned LGS tests.

Figure 20. Bio data of the participants.

least a “3” or a “4” on the questions dealing with passing on knowledge to others and being asked for advice. Similarly, almost all also felt very much needed by other people and liked the idea of working as a teacher. Only one person felt ill-suited or not enticed by the teacher occupation. Furthermore, almost all felt that society should provide food and shelter for the homeless.

PARTICIPANT GENDER AGE COUNTRY

M1 male 23 USA M2 male 28 Brazil F1 female 28 Brazil F2 female 27 Bulgaria F3 female 30 Mexico F4 female 32 Brazil

PARTICIPANT LGS score M1 17 M2 22 F1 20 F2 26 F3 28 F4 31

Figure 21. LGS scores for participants.

In contrast, only two participants scored themselves “3” or above when asked whether they have made a difference in peoples’ lives. Mixed results were reported when participants rated whether they feel that anything that they have done up to this point will survive after they die. Only one participant scored themselves a “4” on the question dealing with being remem-bered after death. The other participants hovered between a “1” and a “2”. These results could very well be attributed to the relatively young age of the participants and perhaps a sense of humility. Nevertheless, as it will be clear later, the results are interesting when combined with the insights from the workshop.

The participants had a bit more trouble working with the cards. One person did not return any of them, two people returned one card, while three completed both cards. The subject matters on the returned cards showed a good variety of topics. One person expressed concerns over the current program studies and future in the chosen profession. The same person also shared a recent incident where he/she was robbed of a possession. “Never robbed in Brazil, robbed in Sweden” wrote the participant. Another participant expressed joy over a newly acquired job and wanted to show of the work location to the family. A different participant wanted to document the gatherings with friends, movie nights and all of the different, new foods he/she got to try. Other participants wanted to share physical growth progression through images and events that shaped their personality. Finally, general life advice and motivational chants were also included in the mix. The participant urged others to “challenge yourself, challenge your beliefs, challenge what you can do” among other things. Overall it was good mixture of person-al and professionperson-al issues, manifested through both images and short texts. As with the sub-ject matters, there was also a wide spread of addressees. The list included: siblings, parents, nieces, cousins, self, future child, future family, fellow students and total strangers.

4.3.2 Probe results interpretation and design inspiration

Though small in sample size, the probe kit gave me a good deal of information and inspiration to move the project forward. This was documented in the form of one-sentence insights writ-ten on post-its (fig. 23). From the results I gathered that age does seem to affect the level of

Figure 22. Returned “future” and “past” cards with sticky notes.

“generativity” (chapter 2.3). It could potentially mean that the AR application to be designed would appeal more to the 25-45 year olds rather than teenagers. The broad range of potential addressees was a positive outcome of the probe. Participants not only addressed the cards (fig. 22) to the their immediate family, but also to themselves and people “in the same boat”, i.e. fellow students. The act of sending messages to oneself can be interpreted as a way of keep-ing a journal, tacitly buildkeep-ings one’s personal digital legacy and a way of processkeep-ing feelkeep-ings and events. I also saw signs of the value of privacy that participants put on the more personal type of messages. On the other hand, some of the messages were just put out there for the curious stranger. I won’t get into great detail about openly putting out geo-tagged content for the public, but as the possibility of abuse of the system by commercial interests or inappropri-ate comments is too great (see Youtube comment fields for example), that option will probably be excluded from the application design.

The variety of topics found in the messages attached to the cards was also quite inspiring. Topics included getting a new job, processing feelings after being robbed of items and

doc-umenting new food experiences at restaurants. This could imply a need of a categorization system within the application to spike the recipients interest and build anticipation.

The topics also showed a broad spectrum of thought processes. Some were directed inwards, like with the participant wondering what he/she was doing in Sweden and whether it was all “worth it”. Others directed it outwards, trying to capture and describe their experiences and events to their siblings and parents. Both positive and negative feelings were captured, which shows that participants did not try to “sugar coat” their messages and did not feel the need to keep up appearances. In order to avoid confusion for the recipient, the creator of content could attribute a certain mood or feeling to the content. That would be a personal choice left to the creator, as the purpose of the application is not historical accuracy but rather captur-ing a subjective experience. Ambiguity is therefore not necessarily an undesirable quality. As previously mentioned, the LGS test showed (chapter 4.3.1) participants rated themselves as being willing to share their experiences and dispense advice to others, yet generally assigned a lower score to having accomplished much in life. The relatively young age of the participants could be a possible answer. Lack of sense of accomplishment and deeming personal events not

worthy of documentation seemed to be a theme with the participants when LGS test results were combined with the workshop interview. I suspect this is in part due to the over-satura-tion of status updates and posts on social media. Part of this result serves the general goal of the proposed concept, because the intent is to explore a different, more deliberate and curated approach to creating personal digital content. Nevertheless, there might be value in designing an impromptu prompt feature for the initial design of the AR application. The application could sporadically nudge the user with a question or statement (perhaps of a slightly provocative nature).

4.4 Practical compromise

Unfortunately, not all six participants were available for the workshop following the dispatch of the probe kit. Only M1,M2 and F1 were able to attend the workshop. In order to accommo-date F2,F3 and F4, a short, online follow-up survey was sent out. The results of the survey will be presented below.

4.5 Follow-up survey

For the three participants (F2,F3 and F4) not able to attend the workshop, a follow-up

sur-vey was created (app. 9.3). Two of the three finished the sursur-vey. The purpose of the sursur-vey was partially to gather feedback on the probe itself - i.e. how easy it was to understand, how engaging it was. The other part of the survey dealt with exploring the participants relation-ship with parents/grandparents, handling of personal digital content and their documentation habits.

4.5.1 Follow-up survey results

The participants felt the probe was “interesting”, “well thought out” and seemed to enjoy remembering events of their past as well as thinking about the future. Both participants also suggested that the instructions for the card exercise could be clearer. Interestingly enough, one person also found the card exercise to be too restrictive, while another liked the fact that it was “open to interpretation”.

Some of the survey results can be found in appendix 8.3.1. As expected, participants were in the habit of saving personal digital content, though it was slightly surprising for me that both stated that they only saved material deemed worth saving, rather than saving all captured material. Both participants had at very least knowledge of key events from their parents/grand parents past and both participants expressed a seemingly strong interest of finding out more, if the opportunity presented itself.

4.5.2 Follow-up survey interpretation and design inspiration

The fact that some participants showed a pro-active attitude towards curating their own per-sonal digital content shows an appreciation and perhaps even a need for deliberate and mean-ingful ways of experiencing such content.

Another interesting bit of information was the discovery that both participants felt a seem-ingly strong urge to expand their knowledge of their parents and grandparent history. Grant-ed, this could be a spur of the moment reply, influenced by the fact as the participants have recently gone through working with the probe kit. However, I believe there is a spark of tacit desire for exploring past history of one’s heritage, evident by the “generativity scores” (chap-ter 4.3.1) and generally positive feedback for the probe. It’s safe to assume that reflecting on previous generations will not an everyday activity for most people. Then again part of this project is treating technology and digital content through the lens of “slow technology” (chap-ter 2.5).

4.6 Workshop

The workshop was conducted in the home of participant M1, which was a familiar setting for all attending. The familiarity was expected to add a degree of comfort and informality to the process. Total duration was approximately two hours. The primary goal of the workshop was to unpack participant attitudes towards posterity, past generations and relations with person-al digitperson-al content. As such, the format chosen was a semi-structured, “quperson-alitative” interview (chapter 3.6), followed by a short group ideation session (chapter 3.5). Interview questions

addressed different aspects of the project such as results of the probe kit, family heirlooms, handling/creation of personal digital content and privacy (app. 9.2). Heavy discussion of AR technology was deliberately kept out was I felt that introducing a specific technology at this stage would be counter-productive to the primary goal of the workshop. With the participants consent, the entire workshop was to be recorded on an audio recording device as well as video.

A mood board of various family heirlooms was also created for the workshop (fig. 24).

Inspired by the concept of “speculative design” (chapter 3.3) the participants were to envision a future scenario where geo-tagged digital content would be housed inside a physical arti-fact. The participants would then be asked to comment on aesthetic form of the artifact and express their general preferences, as well as talk about where such an artifact might be kept and why. The images selected for the workshop can be seen below (fig. 25). The set contained a variety of objects, representing common family heirlooms, modern art sculpture, common forms of capturing material for posterity (such as a time capsule) and a commercial product for digital content storage. The images were purposefully chosen to represent a mix of expect-ed and unexpectexpect-ed artifacts in this context.

4.6.1 Workshop results

The entire workshop lasted approximately two hours. What follows is a recounting of some but not all of issues discussed. The included material was deemed the most relevant for the pur-pose of this paper.

Figure 24. Screenshot of artifact moodboard.

The workshop began with the participants (M1, M2 and F1) unpacking the probe kit and talking about their experience working with it. M1 said that he enjoyed the provocative nature of some of the questions and that they even made him a bit self-conscious. He also mentioned that he really had stop and think about how he really felt about the questions asked. M2 said that he felt the inclusion of targets on the answer sheet made him think of “trying and aim-ing”, rather than answering with accuracy. F1 added that she liked the idea of answering a survey with the permanent action of perforating the paper, but felt the use of paper itself did not inspire a sense of permanence as paper seemed as something delicate and perishable to her. M1 and M2 added that the “future” card was a bit hard to complete, as they had a hard time envisioning the future. F1 agreed. She also added she did not feel comfortable thinking about her own legacy at the moment, although she found it very interesting to read about the history of others in the family. M1 and M2 also found family history interesting to read about.

Moving forward, the participants were asked if there were any type of family heirlooms col-lected within their family. F1 had a collection of small tokens, statuettes and jewelry which her grandma had collected. The process of passing down these items to future generations seemed quite casual. The value of jewels was apparent and they served as financial security. As for the other items, they were appreciated for the stories attached them but there was no emphasis placed on passing the items on to the next generation. M2 did not have many heir-looms outside of his grandfather’s smoking pipe and an old photo album preserved by an aunt who is a historian by trade. M2 would be the first owner of the pipe outside the grandfather. M1 commented that his parents did not bring a lot with them when immigrating to the United States. F1 added that she found it interesting that some objects can start out as insignificant but become cherished family heirlooms over time.

When asked why they liked stories of others but did not enjoy creating their own stories for others to read, participants expressed some interesting sentiments. M1 said that he actually did enjoy the process, but need someone to prompt him or have a “spark of inspiration”. M2 added that he enjoyed his grandfather’s stories because they were connected to major glob-al events such as World War 2. M2 felt that in comparison his life seemed ordinary and rarely worth capturing. F1 expressed difficulty in creating such content for other people and agreed with M2 about not leading a significant enough life to document for posterity. She stressed again that she did enjoy reading about the “ordinary” lives of others, if they were well written.

As the conversation progressed, F1 revealed that she keeps a journal, which she used to

“un-pack personal issues”. She found it helpful that the journal could also reveal patterns about her

with anyone, but would be open to the idea of sharing it with for example future child, if she could explain the context around the journal entries. M1 tried to keep a diary while attend-ing high school, but the diaries quickly turned into sketchbooks. Sketchattend-ing was a form of a temporary distraction from problems for him. M1 also tried to maintain a blog about personal thoughts but “it died” because he quickly realized that he did not want to risk the people men-tioned in the posts reading them. M2 added that he has never written down personal thoughts a way of dealing with issues, but he keeps a record of movies he has seen, random ideas and draws video game puzzles.

All three participants agreed that they would be more willing to share their more personal digi-tal content if they could control who would receive it. F1 also added that there also exists a specific sub-set of really close friends and family within the friends/family circle, and that she felt it was responsibility of hers to share experiences and thoughts with them. All three par-ticipants also had vast collections of personal digital media, mostly in form of images but also texts and composed musical pieces. The content was sorted into specific folders and sorted either by date or themes such as “vacation” or “conference”. M1 stated that he occasionally curated the content when space became scarce. Only M2 used a cloud service to store his per-sonal images. M1 and F1 were not found of storing their photos on the cloud. Partially because they started saving pictures before the invention of the cloud and moving them would be to much work. One participant stated that he did not necessarily need his content to be available anytime and anywhere. F1 added that keeping it on an external hard drive was more private and saw no reason to move them to the cloud. M1 also stated that he sometimes uploaded images of interest to others, such as vacation pictures, onto Facebook. All three participants were willing to share all of the content with a potential child of their own.

Lastly, the participants were presented with the object images (fig. 25) and asked to imagine the object as a storage for personal digital content. F1 found the “grandfather clock” design to be “kitschy” and was more drawn towards a more geometric or abstract form. She was not against the idea of the clock if design was more “contemporary”. She also liked the concept of an artifact seemingly serving as pure decoration, hiding the digital storage function. Another idea that appealed to her is involving some sort of physical interaction to the artifact. M1 and M2 were also partial to the geometric design (fig. 26). M2 also added that he preferred an ar-tifact without visible corporate branding. All three participants felt that the best place for the artifact was to be “in plain sight” such as the living room, if the function was not apparent.

4.6.2 Workshop interpretations and design inspiration

The workshop yielded several insights. The participants were hesitant to use cloud services for storing digital content of the more sensitive nature, preferring instead to keep it on a physical