A design tool for clothing companies

to engage consumers in the circular

textiles economy

Designing for the

Circular Consumer

Authors: Ina Obernosterer & Erika Thunstedt

Master Thesis in Innovation & Design

Mälardalen University

IDT - School of Innovation, Design & Engineering

Examiner: Yvonne Eriksson

A design tool for clothing companies to engage consumers

in the circular textiles economy

Designing for the Circular Consumer

© Ina Obernosterer & Erika Thunstedt

School of Innovation, Design & Engineering, Mälardalen University

Abstract

The current prevailing take-make-waste economy has caused the global climate crisis, operating outside the Planetary Boundaries of our planet (Rockström et al., 2009), disrupting nature's balance and affecting all life on earth (WWF and Global Footprint Network, 2019). Both the European Commission and the European Environmental Agency (EEA) sees the transition to a circular economy (CE) within the product category: textiles, apparel and fabrics as a priority to address the climate impact of the textile and clothing industry (Manshoven et al., 2019). Even though there is much research done on how design and products can help companies transition to a CE, there is still an unexplored dimension of the role that consumers play in this transition. Thus, this master thesis aims to fill this research gap by exploring consumer behaviour in different consumption phases as well as the role of consumers in the circular textiles economy and investigate how sustainable clothing companies can design to engage consumers in a circular behaviour and role. By doing so, it is hoped to contribute to a better understanding of the dimension of the consumer in the circular textiles economy and to identify ways to fulfill the CE principle - keep products and materials in use. The study was conducted through a novel implementation of Research through Design in combination with Interactive Research by using the Design Thinking framework as a research process. The research was executed in close collaboration with the Swedish outdoor clothing company Houdini Sportswear.

The results show that a number of Circular Consumer Behaviours are desired to be acted out in four identified phases of a Circular Clothing Consumption Process: Lifestyle Creation, Product Acquisition, Product Use and Product Dispossession. Furthermore, it was found that the role of the Circular Consumer is very complex and consists of various sub-roles on four layers: Functional, Emotional, Life Changing and Social Impact. On the basis of this knowledge, the theoretical concept of Design for Circular Consumers was developed. On the basis of this theory, the Design for Circular Consumers Tool was created as the key contribution of this thesis. This tool facilitates the design of experiences that engage consumers in the circular textiles system and subsequently support clothing companies in their transition to circular business models as a way to address the climate impact of the textiles industry.

Keywords: Circular economy, circular design, design research, research through design,

interactive research, design thinking, circular behaviour, design for sustainable behaviour, design for circular behaviour, design for circular consumption, design for circular consumers

Acknowledgements

“Designers can play a role in moving towards a circular economy, through their ability to understand and influence business and consumer behaviour.” (Wastling et al., 2018)

This statement has motivated and inspired us to deep dive into the sphere of the circular economy. With a pre-existing interest in sustainability and sustainability related topics as well as fashion and nature, this thesis has allowed us to bring all of them together while simultaneously being able to really make a difference. We explored the dimension of consumers, like you and us, in a new more sustainable textiles economy, which enabled us to not only broaden our individual horizons, but also create valuable knowledge that is vital for the much-needed transition to the circular economy.

This thesis would not have been possible without the help and support from several people, to whom we want to express our deepest gratitude. First of all, we would like to say thank you to our supervisors Erik Lindhult and Bjarne Hindersson. Your expertise and assistance throughout this research process has guided and supported us in creating new and valuable knowledge.

A great thank you goes also to our industrial supervisor, Eva Karlsson, and the rest of the involved Houdini employees. They stood by us in every step of this very collaborative research process and were always extremely enthusiastic as well as overflowing with energy and ideas. This research would not have been possible without your dedication, support and engagement.

Last but not least, we would like to express our gratitude to everyone else who has participated in this research. Thank you for sharing your knowledge, needs and wishes with us - this thesis would not have been the same without every single one of you.

Ina Obernosterer & Erika Thunstedt Stockholm & Innsbruck, June 2021

Table of contents

Introduction 8

Background 9

Research gap & problem description 16

Research aim & purpose 19

Researchers, collaboration & co-production 21

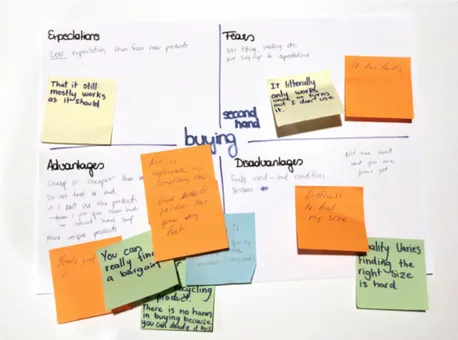

Scope & delimitations 22

Thesis outline 22 Research methodology 23 Research approach 23 Research design 27 Data analysis 38 Presentation of data 38 Research quality 39 Research ethics 40 Theoretical background 41

Consumers, sustainability & the circular economy 41 Phases of the consumption process and desired consumer 44 behaviour in the circular economy

The role of the consumer & other actors in the circular economy 52 Designing for consumers in the circular textiles economy 60

Project process 63 Discover phase 63 Define phase 74 Ideate phase 85 Evaluate phase 1 89 Experiment phase 96 Evaluate phase 2 100 Results 105 Sub-question 1 105 Sub-question 2 111

Main research question 115

Conclusion 121

Recommendations & future research 124

References 125

List of figures

Introduction (p. 8-22)Figure 1: The three principles in the CE

Figure 2: The 9R Framework - presenting nine strategies for transition to a CE Figure 3: Material flow of the clothing industry

Figure 4: ECAP’s illustration of a circular clothing system

Figure 5: Houdini’s Design checklist that they use in their product design process

Figure 6: Project focus, one of the three pillars of the CE: Keep product and materials in use Methodology (p. 23-40)

Figure 7: The Engaged Scholarship Diamond Model for interactive research

Figure 8: The research context showing project stakeholders and value creation process Figure 9: The two-circle interactive research model applied in the collaboration process

Figure 10: The eight project phases based on Design Thinking executed in the research process Figure 11: The iterative research process applying Design Thinking on two levels

Figure 12: The research design with eight research phases and their focuses Theoretical background (p. 41-62)

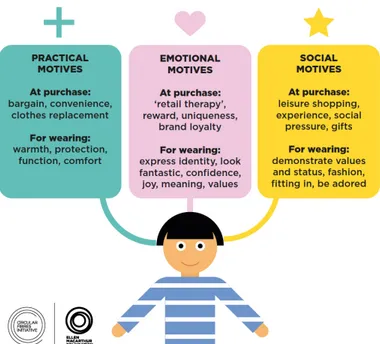

Figure 13: The complex relationship between people and clothing influenced by a number of motives Figure 14: Illustration of Circular Consumption

Figure 15: Model of Circular Behaviour

Figure 16: Illustration of circular consumption behaviours

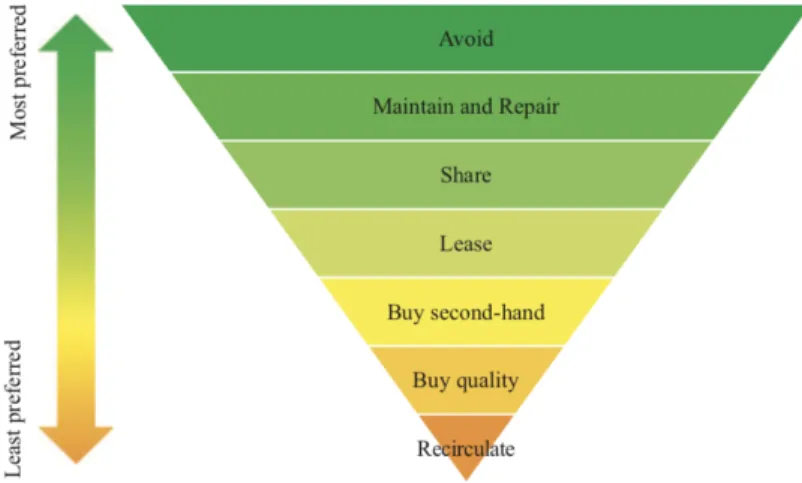

Figure 17: Illustration of the Hierarchy of consumption behaviour in the circular economy

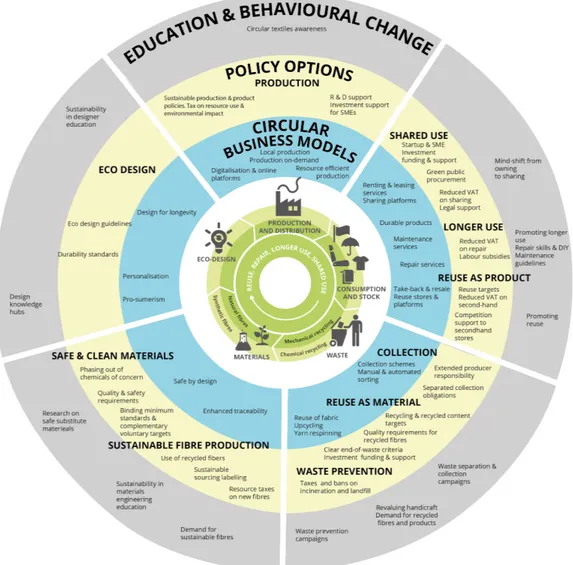

Figure 18: The role of circular business models, policy options, education and behavioural change in

circular textiles systems

Figure 19: Key components of the Design for Circular Behaviour (DfCB) process Project process (p. 63-104)

Figure 20: Key activities of the Discover phase

Figure 21: List of reviewed literature in the empathy activities

Figure 22: Result of the Planetary Boundaries analysis of Houdini, showing the nine planetary

boundaries and how Houdini's main sustainability strategies are connected to these.

Figure 23: Template for exercise 1 of Houdini workshop 1

Figure 24: Identified stakeholders and their relationships in the CE based on empirical findings Figure 25: Role description of the ideal user based on empirical findings

Figure 26: Role description of the ideal clothing company based on empirical findings Figure 27: First version of the ideal circular customer journey from Houdini workshop 1 Figure 28: Key activities of the Define phase

Figure 29: Result of the ideal customer journey exercise

Figure 30: A third version of the ideal circular customer journey from Houdini workshop 2 Figure 31: Result of the second level analysis of Houdini challenges

Figure 32: Result of the second level analysis of user challenges

Figure 33: Example of the assessment mapping for the clothing access model buying second-hand Figure 34: The role of Houdini as a result of the analysis of the Houdini collection launch

Figure 35: Result of the analysis of critical issues in business strategy Figure 36: Summary of user needs derived from User workshop Figure 37: Three gaps between circular businesses and users Figure 38: Concept of a new possible role for Houdini

Figure 39: Key activities of the Ideate phase

Figure 40: Exercises ‘Back to the future’, with the scenario of the year 2030 in the NCS Summit

-interactive workshop (Things I own in 2030, How I own in 2030 and Communication 2020-2030)

Figure 41: Example of the result for one of the workshop questions ‘When I say Circular Economy,

you say?’

Figure 42: Circular Behaviour Pyramid - Analysis of result from Nordic Circular Summit’s interactive

Figure 43: Key activities of the Evaluate phase 1 Figure 44: Connected theories found in literature

Figure 45: Literature findings of desired consumer behaviours in four phases of the circular clothing

consumption process

Figure 46: Identified stakeholders in the CE from literature Figure 47: The role of clothing

Figure 48: Identified levels of responsibility & engagement of consumers from literature Figure 49: Identified key responsibilities of the consumer role from literature

Figure 50: Identified strategies for clothing companies from literature Figure 51: The Elements of Value Pyramid

Figure 52: Illustration of the desired circular consumer behaviours in the Circular Clothing

Consumption Process

Figure 53: Key activities of the Experiment phase

Figure 54: Template for exercise 1 of Prototyping workshop Figure 55: Template for exercise 2 of Prototyping workshop

Figure 56: Outcome of the Prototyping workshop: a draft for a Circular Experience Checklist Figure 57: Iteration of the framework to achieve less focus on the product

Figure 58: Key activities of the Evaluate phase 2 Figure 59: Framework 1a & 1b tested in the workshop Figure 60: Framework 2a & 2b tested in the workshop Figure 61: Result of the testing activities of framework 2b Results (p. 105-120)

Figure 62: The Four Phases of the consumer’s Circular Clothing Consumption Process Figure 63: The Hierarchy of the Circular Consumption Behaviours desired in the four Clothing

Consumption Phases of the CE

Figure 64: Roles of a Circular Consumer dependent on garment lifecycle phase and engagement

level

Figure 65: Design for Circular Consumers Tool

List of tables

Table 1: Different consumption phases mentioned in literature Table 2: ‘Critical Behaviour in the Circular Economy’

Table 3: The roles of consumers in the CE

Table 4: Questions integrated in the Design for Circular Consumers Tool

List of appendices

Appendix 1: Theoretical Background Appendix 2: Houdini Investigation Appendix 3: Houdini Workshop 1 & 2 Appendix 4: User Workshop

Appendix 5: Nordic Circular Summit Appendix 6: Houdini Collection Launch Appendix 7: Prototyping & Testing workshops

List of abbreviations

DT Design Thinking CE Circular Economy

EMF Ellen MacArthur Foundation EU European Union

EEA European Environmental Agency DfCB Design for Circular Behaviour DfCC Design for Circular Consumption SDGs The Sustainable Development Goals

1.

Introduction

Society is today living in the era of the linear ”take-make-waste” economy, where natural resources of the earth are overexploited at an increasing pace (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2019). Since the 1970s the rate of consumption has risen to a level where natural resources are used faster than they can be renewed. At today's pace of overconsumption 1.7 planets would be needed to provide for all human needs, but we only have one (WWF and Global Footprint Network, 2019). This linear approach exploits resources in every step of the product process and releases in the process Greenhouse Gas Emissions (GHGs) to the atmosphere, which are causing our global climate to change drastically (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2019). The take-make-waste economy of society has caused the global climate crisis, disrupting nature's balance, affecting all life on earth (WWF and Global Footprint Network, 2019). Society's current consumption rate can not continue without creating permanent damage to the ecosystem on which humans and all other life depends (Everett, 2001, p. 105).

In order to address the global challenges that society is facing, the United Nations (2016) have created The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), 17 goals created as a blueprint and urgent call for action to “achieve a better and more sustainable future for all” (United Nations, 2016). Several goals are focusing on climate change and environmental degradation, especially number 13: “Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts” (United Nations, 2016). Goal 13 focuses on: energy efficiency, circular economy, sustainable growth, resource efficiency and climate action.The circular economy is one of six transformations that the European Union (EU) presents as a priority in order to meet the SDGs within the EU: ‘Clean and Circular Economy with Zero Pollution’. This strategy focuses on restraining pollution, reducing material consumption, and minimising the environmental impact of European industry and consumers. The EU believes that the CE is a possible way to create sustainable change and proposes a ‘Circular Economy Action Plan’. A plan that declares initiatives for the entire product life cycle. (SDSN & IEEP, 2020)

“It targets how products are designed, promotes circular economy processes, encourages sustainable consumption, and aims to ensure that waste is prevented and the resources used are kept in the EU economy for as long as possible.” (SDSN & IEEP, 2020)

Yet, efforts made by society to tackle the climate crisis have so far mostly focused on reducing the climate- and environmental impact of the current linear system such as more efficient production techniques, reducing impact of materials or transitioning to renewable energy. In order to create sustainable benefits both for the environment and the economy, there is a need for society to transition from a linear to a circular economy (further called CE). (Piscicelli and Ludden, 2016)

The European Commission sees it as a priority to transition to a CE within the product category: textiles, apparel and fabrics. Also the European Environmental Agency (EEA) proposes how the CE can be an approach to address environmental- and climate impacts from the textile and clothing industry (Manshoven et al., 2019). The EEA (2019) imagines the CE as: “one in which circularity is ensured in all phases of the lifecycle, including materials, eco-design, production and distribution, consumption and stock, and waste”. By ensuring

circularity in all phases of the product life cycle the EEA sees that a transition to the CE can be a way to change the industry towards a circular textiles economy.

1.1.

Background

This background will lay the foundation for this master thesis by introducing the concept of the CE and how the CE can be a possibility for sustainable change. With focus on the European context, the background will also discuss the current consumption problems in the textiles and clothing industry, by introducing the consumer's environmental impact and the challenges facing the industry. It will also discuss how the CE can be a possibility for change within the industry by presenting the concept of a circular textiles system.

1.1.1.

The Circular Economy

The concept of the circular economy is based on the Cradle to Cradle movement, first formulated by Braungart and McDonough (McDonough and Braungart, 2002). It has since then been mainstreamed by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (EMF) with the aim to create a coherent framework of the concept for business, academia, policymakers and institutions Their mission is to accelerate society’s transition to a CE and are commonly used in academic research as the foundation for the CE concept. According to EMF the CE is based on the three principles of “designing out waste and pollution, keeping products and materials in use, and regenerating natural systems” (Figure 3). (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2015)

Figure 1: The three principles in the CE (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2019, p. 21)

Along with this, the academic field also sees the CE as a possibility for sustainable change. According to Kirchherr et al. (2017), who investigated 114 definitions of the CE, the CE replaces the ‘end-of-life’ concept with the aim to accomplish sustainable development through novel business models and responsible consumers. Also Wastling et al., (2018) declares that the circular economy envisions a global economy that is “regenerative and restorative by intention and design” and is based on a system thinking approach, whose aim is to “circulate products at their highest level of value”. Kirchherr et al. (2017) have through their research created a definition of the CE, which they defines as:

“an economic system that replaces the ‘end-of-life’ concept with reducing, alternatively reusing, recycling and recovering materials in production/distribution and consumption processes. It operates at the micro level (products, companies, consumers), meso level (eco-industrial parks) and macro level (city, region, nation and beyond), with the aim to accomplish sustainable development. It is enabled by novel business models and responsible consumers.” (Kirchherr et al., 2017, p. 229)

Common frameworks that are used in the context of the CE are often referred to as the 3R framework, the 4R framework the 6Rs or 9Rs. From all of these frameworks, Kirchherr et al. have developed the possibly most nuanced one - The 9R Framework (Figure 2) (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2019; Kirchherr et al., 2017). In this framework they present nine circular strategies in a hierarchy which ranks the strategies from the linear economy to the CE.

Figure 2: The 9R Framework - presenting nine strategies for transition to a CE (Kirchherr et al., 2017)

1.1.2.

Production & consumption in the textiles & clothing industry

The negative environmental impact of the textile and clothing industry is significant due to the current linear take-make-waste economy and the fast fashion trends (WRAP, 2017; Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017, pp. 1, 20). It is debated how polluting the textile clothing industry is, but some see it as the second most polluting industry globally (ENTeR, 2020; Henninger et al., 2017), accounting for 10% of the world's carbon dioxide emissions (CO2). Textile production causes more greenhouse gases than production of many other materials. Depending on the fibre, textiles produce between 15-35 tonnes CO2 per 1 tonne of produced textile. This can be compared to 3.5 tonnes CO2 produced for 1 tonne of plastic (Manshoven et al., 2019).

In the last 15 years, the production of clothing has doubled, which is mainly due to the fast fashion phenomenon (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017, p. 18), which builds upon new and rapid changes in fashion trends, encouraging mass consumption and the notion that consumers “need” to follow trends and consume more products (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017, p. 3; Henninger et al., 2017; WRAP, 2017). This is achieved through profitable and efficient exploitation of resources in an extremely competitive market (ENTeR, 2020). The current systems in the industry are globalised, where resources in the system are extracted, produced, transported, consumed and disposed in linear value chains (Manshoven et al., 2019).

In the ‘Strategic Agenda on Textile Waste Management and Recycling’ by ENTeR (Expert Network on Textile Recycling), the view of consumers in the textile and clothing industry and its consequences are problematized:

“In this context, the consumer is portrayed as a rational subject that makes his consumption choices in an efficient way: he tries to balance prices, personal gratification and the latest trends “... “condemns eco-products to remain within a very narrow niche, reserved for the minority of consumers who perceive eco-compatibility or sustainability as positive elements within their utility function. Therefore, the process of incentivising environmentally sustainable purchases sees on the one hand the institutions, with the task of educating and informing about sustainability issues, and on the other the companies that will have to generate an offer of quality products with low environmental impact.” (ENTeR, 2020, p. 29).

In 2015 the industry produced 53 million tonnes of fibres for clothing production and, according to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, the industry uses a total of 98 million tonnes of non-renewable resources per year to produce clothes including “oil to produce synthetic fibres, fertilisers to grow cotton, and chemicals to produce, dye, and finish fibres and textiles” (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017, p. 20). This puts a lot of pressure on the natural resources and “pollutes and degrades the natural environment and its ecosystems, and creates significant negative societal impacts at local, regional, and global scales” (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017, p. 19).

According to EURATEX (2018), the EU is the largest market in the world for clothing consumption, with 520 billion € in household consumption. In 2018 the textile and clothing industry in the EU had a turnover of 178 billion €. Clothing is also “the sixth largest expenditure item for households” in the EU (WRAP, 2017).

Raw materials

In 2017 the raw materials needed to produce all textile, clothing and footwear for consumers in the EU was estimated to be 675 million tonnes, resulting in 1,321 kg of raw materials per person (Manshoven et al., 2019). The average European uses around 30,000 kg of raw materials per year, and the middle class can use up to 60,000 kg per year. With these numbers the materials used for clothing do not seem so much, but this should be compared to the calculation of materials used for a sustainable lifestyle, where a person would only use 8,000 kg of materials per year (WBCSD, 2020).

Greenhouse gas emissions

In 2017, the EMF estimated the yearly greenhouse gas emissions from the textile and clothing industry to be 1.2 billion tonnes, which is more than all international flights and maritime shipping combined (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017, p. 20). In 2015, WRAP estimated that the overall yearly carbon footprint of clothing consumption in the EU was 195 million tonnes of CO2 (WRAP, 2017). According to the EEA, the EU generated 334 million tonnes CO2 worldwide from the textile industry in 2017, making it, amongst household products, the fifth largest group regarding climate impact (Manshoven et al., 2019).

Waste

The industry also creates a lot of waste, both from the supply chain and at the end of product life, where clothes are thrown away (WRAP, 2017). According to the EEA, half of the fast fashion clothing that is produced is estimated to be disposed of in under a year (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017, p. 19). Once an item is discarded, less than half of the items are recycled (Šajn, 2019). Waste is produced in the entire value chain, textile waste from production often has good quality and can be reproduced whilst the quality of the post-consumer waste often is inconsistent and contains mixed textiles (ENTeR, 2020, p. 14). There is contradicting data in what stage and which stakeholders that have the biggest environmental impact of the clothing industry. Some say that 44% of the industry's total climate impact occurs in the use phase, 51% in the production phase and 5% due to transport (Manshoven et al., 2019). Others say that the use phase has the largest CO2 impact (in the EU), and that the production phase accounts for almost a third of the CO2 emissions (WRAP, 2017). While this might be true when evaluating the whole climate impact for a produced item, it needs to be considered that without the high demand from consumers, the total amount of clothing items produced would be much less extensive. Therefore it needs to be considered that if an item is not produced it also can’t have any climate impact. No resources are taken from nature, no energy is needed for production and no waste can be produced. This is why the demand of consumers is something that plays a huge role in the total calculation of the industry's climate impact. Therefore the consumers play an important role in the current unsustainable ways of the clothing industry, in the way they consume, use and dispose of garments.

1.1.3.

Consumer & consumption in the textiles & clothing industry

As the Ellen MacArthur Foundation (2017, p. 18) declares, “textiles and clothing are a fundamental part of everyday life”, a basic human need that keeps us warm and protected and one that we could not live without. Clothing is often also a strong emotional experience for the consumer (Henninger et al., 2017 p.86). For many individuals, clothes is a way for self-expression and identity creation (Henninger et al., 2017) The activity of shopping is for some individuals also an entertainment that creates a temporary experience of pleasure and excitement that enhances the fast fashion model (Henninger et al., 2017 p.86).

There are different estimations on how much clothes a person consumes in a year in the EU. In 2014, the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC) estimated a total of 19.1 kg textiles consumed by an average EU citizen (Manshoven et al., 2019). And in 2017 the textile consumed was estimated to be 26 kg (Manshoven et al., 2019).

Consumers’ utilization of clothes

There are a lot of underutilized clothes in the wardrobes of people. Consumers own more than they need and discard the garments quicker than 15 years ago (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017, p. 18). One research shows that more than 30% of Europeans' clothes have not been worn in the last year (Šajn, 2019). Garments are often only used by consumers for a few times before they discard it, some just after seven to ten wears (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017, p. 19). The European Commission estimates the discarded textile in the EU to be 11.3 kg textile per person and year, generating a total of 5.8 billion tonnes of textiles discarded in the EU during one year (Manshoven et al., 2019). After use, most of the material is sent to landfills or are incinerated (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017, p. 3). According to the EMF, a total of 73% of the material is lost after use, and “less than 1% of material used to produce clothing is recycled into new clothing, representing a loss of more than USD 100 billion worth of materials each year” (Figure 3) (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017a, pp. 18, 36). Combining the loss of material, clothing underutilisation and lack of recycling this creates a value loss bigger than USD 500 billion a year (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017).

Figure 3: Material flow of the clothing industry(Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017, p. 37)

1.1.4.

Climate crisis - Efforts made & challenges ahead

Society is starting to take action on climate changes and the current unsustainable way of life and consumption. The clothing industry and its consumers are becoming more aware of the negative impacts that the system has on the environment. The understanding of consumers regarding negative impacts has increased, putting pressure on the brands and retailers in the industry. Clothing companies have the possibility and a unique position to create big changes in the way that society consumes clothes. By changing their value proposition companies can influence consumers’ consumption-, purchase- and usage behaviour. Through their design of products and services, companies can drive change for a more sustainable industry. But most efforts done by the clothing industry so far are still lacking a systematic approach that addresses the core problems of the industry: clothing

utilisation and recycling. (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017, p. 22)

1.1.5.

Circular textiles economy - Towards a more sustainable textiles system

A CE can enable the textile and clothing industry to become more sustainable and reduce the environmental effect of clothing consumption and production. It can also enable the industry to operate within the Planetary Boundaries of the planet (Rockström et al., 2009) and to implement the UN’s SDGs in the current practices (United Nations, 2016).

The report Circular Economy in the Textile Sector (Adelphi, 2019) discusses challenges and potential solutions for the transformation to a circular textiles industry at the EU level. The report defines the following definition of a circular economy within the textiles industry:

“A circular textiles economy describes an industrial system which produces neither waste nor pollution by redesigning fibres to circulate at a high quality within the production and consumption system for as long as possible and/or feeding them back into the bio- or technosphere to restore natural capital or providing secondary resources at the end of use.” (Adelphi, 2019).

Also the EMF defines the circular textiles system, based on the three main principles of a circular economy they define it as one that is:

“…restorative and regenerative by design and provides benefits for business, society and environment. A system in which clothes, fabrics and fibres are kept at their highest value during use, and re-enter the economy after use, never ending up as waste” (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017, p. 44).

Based on these definitions the textile and clothing industry require fundamental changes in the current processes in order to transition towards a circular textile industry (Adelphi, 2019); Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017, p. 44). This means that the industry and especially the clothing companies, needs to redesign their current processes and collaborate with other stakeholders in the industry in order to create system change. New technical innovations by clothing companies, manufacturers or producers need to be supported by textile regulations for production and consumption and implemented by different stakeholders in the system. The product design needs to enable longer use and reuse from consumers and the production process needs to be more efficient with fewer emissions and less waste, also favouring renewable materials. In a circular textile economy, social innovation is needed in the process in order to consider how and why consumers interact and share their clothing in order to enable sustainable behaviour change by the consumers. (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017)

In a circular textiles system, six components are important for clothing companies and other stakeholders to aim for:

● “A new textiles economy produces and provides access to high-quality, affordable, individualised clothing.”

● “A new textiles economy captures the full value of clothing during and after use.”

● “A new textiles economy runs on renewable energy and uses renewable resources where resource input is needed.”

● “A new textiles economy reflects the true cost (environmental and societal) of materials and production processes in the price of products.”

● “A new textiles economy regenerates natural systems and does not pollute the environment.”

● “A new textiles economy is distributive by design.” (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2017, p. 45).

The European Clothing Action Plan (ECAP) presents an illustration of eight action areas within the textile and clothing industry that are important for the industry to address in order to achieve a circular clothing system (Figure 4) (ECAP, 2019). These action areas are a part of the clothing lifecycle and are: Raw Material Extraction, Textile Production, Clothing Manufacturing, Retail or Service, Consumption, Re-use & Repair, Collection and Recycling.

Figure 4: ECAP’s illustration of a circular clothing system (ECAP, 2019)

The six components presented by the EMF (2017) together with ECAP’s (2019) illustration of a circular clothing system (Figure 4) creates a framework for stakeholders in a circular textile economy regarding how to operate based on the CE principles.

In the ECAP illustration (2019) (Figure 4), one of the key stakeholders presented in the system is consumers, which are connected to three of the eight action areas. This displays the importance that the consumers play in a circular clothing system. Clothing companies can have control and oversee the process of the other five action areas but without considering the consumers in the system they can not transition to a circular textiles system.

1.2.

Research gap & problem description

Research addressing the CE and circular design has so far mostly focused on two of the circular principles: Design out waste and pollution and Regenerate natural systems (Figure 1) (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2019). That is focusing on how waste and pollution from the production chain can be reduced. Current research lacks focus on the principle Keep products and materials in use. According to Wastling et al., (2018), current literature on circular design focuses on the technical aspects of products, how they are designed to fit the system of a CE, neglecting the importance of how products fit people and their behaviour in the system. This lack of focus on the consumer in the transition to a circular business is due to the viewpoint that the CE is a producer-led solution (Wastling et al., 2018). Also Piscicelli and Ludden (2016) mention the broadly unexplored dimension of the consumer in the CE, which they find contradicts “the fact that most circular business models require (and rely on) a significant change in consumer behaviour and consumption patterns”. Despite the importance that consumers play in enabling the CE, this area is still under-researched (Maitre-Ekern and Dalhammar, 2019, p. 395) and underestimated (Piscicelli and Ludden, 2016; Wastling et al., 2018).

Camacho-Otero et al., (2018) identified through their literature review on consumption in the CE that most scientific work focuses on “factors that drive or hinder the consumption of circular solutions'' such as consumer acceptance of circular offers (Camacho-Otero et al., 2019), knowledge (Testa et al., 2020), attitudes and perceptions (Muranko et al., 2019) and ownership (Baxter, 2017). While this is a good start, key components are still missing in the current literature. Wastling et al., (2018) declare that a clear description of the role of the consumer is needed in the research addressing the CE. Dr. Keshav Parajuly (2020) also identifies the need for further investigating the motivations of consumers behind their actions and the importance of consumer behaviour in product lifecycles. Baxter (2017, chap. 2) further declares the importance of understanding what consumer behaviour is critical “to the circulation of material at the system level”, which is connected to the circular principle Keep products and materials in use (Figure 1).

It is crucial for companies transitioning to sustainable development through a CE to include the consumer in their strategic work in order for them to successfully follow the three pillars of the CE and thereby reduce their negative impacts on the climate (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2019, p. 21). This is because the consumer’s and their behaviour, in our current economic situation, are a part of, and also responsible for, the negative impact society has on the environment (Genus, 2016, chaps. 3 & 6). Within a CE, that is seen as a successful way to address climate change, there is no common definition of the behaviours that consumers need to engage in, in order to reduce their climate impact. There is also no common definition of the consumers’ role in the CE. (Maitre-Ekern and Dalhammar, 2019, p. 395; Piscicelli and Ludden, 2016; Wastling et al., 2018).

The consumer behaviour in the sustainable clothing industry is only partially understood; there exists “no comprehensive review of clothing and sustainable behaviours” (WRAP, 2017). In order to find a practical and scientific understanding of the consumers’ role and desired behaviour within the CE and in order for the industry to successfully transition to a circular textile economy, there is a need to further explore an interdisciplinary (Parajuly et al.,

2020) and a more human-centered design perspective in Innovation and Design research (Wastling et al., 2018).

The goal of this master thesis is to contribute to the under-researched area and fill the gap by exploring the role that consumers have in the circular textile economy and what behaviour is critical for consumers to engage in in order for a circular system to be successful in the industry. This is explored within the specific context of the textile and clothing industry in the EU, since the European Commission sees the need to prioritize the transition towards a circular textiles economy within this industry sector (Manshoven et al., 2019).

In order to achieve the goal of the thesis, the problem area of the research is investigated through a collaborative research project together with an implementation partner from the sustainable textile and clothing industry operating in Europe. This approach creates an opportunity to, through the conducted research project, implement both theoretical work and design work “in a real world setting”. With an active collaboration partner participating in the research process a greater understanding of the problem area can be reached as well as versatile results that can help bridge the gap between the academic field and practice. (Alles et al., 2013, p. 107).

The chosen collaboration partner is a Swedish clothing company Houdini Sportswear (further called Houdini), who are currently working with a circular business model within the context of the sustainable textile and clothing industry. The problem context of Houdini will be further discussed in the next section.

1.2.1.

Problem description of Houdini

Clothing companies within the textiles industry face major challenges in transitioning their business models to circular business models (Henninger et al., 2017, p. 37). When it comes to transitioning to the CE, Houdini has already implemented a circular business model in their strategic work and started to incorporate circular principles in their business with the goal to create a more sustainable outdoor industry. Through a company investigation (Appendix 2) it was identified that Houdini have come a long way in their circular journey, especially when it comes to material use, production and recycling. Circular design is central in the company's business strategy and they define circular as “Styles designed to be recycled at end-of-life and made from recycled or organic, renewable and biodegradable fibres.” The company considers the products environmental impact, the volumes produced and the lifestyle their customers choose to live as well as the lifestyle they as a company promote. (Houdini Sportswear, 2021)

Houdini's goal is to be 100% circular by 2030, with an entirely circular ecosystem, enabling circular flows of materials, products and knowledge, throughout their value chains and different customer phases. The company aims at creating a circular system with closed resource loops, no raw material taken from the earth’s crust, lowered emissions and no waste (Houdini Sportswear, 2021).

“In order to reach our vision, systemic change will be required. We need to embrace complexity, acquire holistic, robust and in-depth understanding of the

complex systems we are part of in order to understand how to engage in, contribute to or change them.” (Houdini Sportswear et al., 2018)

The company uses a Design Checklist (Figure 5) as a key strategic component in their production and design processes to ensure a circular product lifespan and circular design. The Design Checklist includes seven questions for the design process of products, which questions the existence, the durability, the material, the circularity and the next-life solution of products (Houdini Sportswear, 2021). However, the framework does not include the Houdini customers or adress the aspect of the customers’ role in the circular product lifespan. This can be contradicting when trying to ensure a circular product lifespan, since the product is bound to - and maid for the customer and the customer use of the product.

Figure 5: Houdini’s Design checklist that is used in their product design process (Houdini Sportswear, 2021) For transitioning to circular business models, clothing companies face the challenge of needing to understand the role that consumers play in a circular system. This is important since the consumers and the way they behave can influence how resources and products are consumed, used and discarded in the system. On top of this, consumers also have a big role to play when it comes to the climate impact of the company and the industry (Wastling et al., 2018). However, it seems unclear to what extent Houdini considers customers in their business process and how effective they are at making sure that the customers actions also align with circular principles and their circular business model.

Even though Houdini have come a long way when it comes to producing sustainable and circular products, they need to further implement the circular principles in their work in order to reach their goal of creating a fully circular system, which is dependent on their customers. Houdini sees the need to further investigate how to include their customers in their ecosystem to ensure that their products have the longest product life possible through product care, and that materials circulate through the system, through collection and returning.

Another identified challenge for Houdini is that they mostly refer to their customers as end-users. This is problematic in a circular system, where resources and materials should not reach an end (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2019). This creates a challenge for Houdini

in shifting their mindset from a linear, to a circular one. However, Houdini are not consistent with their naming or viewing of their customers, also calling them customers and users. Without a clear view of the role of their customers and the part they play in reaching 100% circular systems, it might be a barrier for the customers themselves to take on the role that is necessary for Houdini's circular business model to succeed. (Houdini Sportswear, 2021) Houdini declares that their plan in the future is to help their customers to turn into activists. By 2022, the goal is to “enable a 100% connected community for end-users to turn activists'' and “have 100 000 end-users, followers and fans turned activists” (Houdini Sportswear, 2020). With this goal, they aim at changing the role of their customers from users to activists and thereby also changing their behaviour. In order to achieve this, Houdini is facing the challenge to understand what behaviour and role their customers must be engaged in in order to enable and support their circular business model and the CE as a whole.

The identified challenges found in the initial company investigation (Appendix 2) show that there is a need for Houdini to further include and engage their customers in their circular business and design strategies. By understanding the role their customers play in their circulatory system and creating a clear view and naming, Houdini can become more circular in their mindset. Furthermore, by understanding the consumption behaviour and actions needed from customers, Houdini can address the challenge of designing a circular system. Lastly by reinventing their design tool (the Design Checklist) they can create new ways of engaging their customers in their circular business model and thereby also successfully achieve their goal of being 100% circular by 2030.

1.3.

Research aim & purpose

Due to its co-productive approach, this thesis naturally aims at producing value in the form of new knowledge for both the academia and the industry. The goal is to, through an exploratory design process, co-produce knowledge and value with the collaboration partner Houdini as a relevant representative of a sustainable clothing company transitioning to a CE. It is also to fill the identified research gap in the academic field of Innovation and Design. More specifically, the thesis contributes to and advances the theory of Design for Circular Behaviour (DfCB) and Design for Circular Consumption (DfCC) and thereby encourages the vitally needed research for changing current clothing consumption standards. Yet, by naming and framing the behaviour and role of consumers in a circular textiles economy not only the academic field is enriched, but also the practices of clothing companies that are transitioning to a circular textiles economy are supported. In the context of this thesis, the practices and challenges of the collaboration partner Houdini are especially targeted to identify ways to be enhanced regarding the engagement of consumers in the CE. Value is created through new knowledge and a design tool that benefits the company in reaching their goal of becoming 100% circular by 2030. The ambition is to contribute with an in-depth understanding of the complex problem area that will help Houdini understand how they can design their products and services in a way that engages consumers in the desired behaviour and role that is necessary for the success of a circular business model as well as the circular textiles economy in general. More specifically, the goal is to investigate through Houdini what role customers play in the circulatory system and how Houdini can create crucial internal and external change through including and addressing them in Innovation and Design practices within the company.

In order to achieve this aim, three research questions have been developed in the form of one main research question that is supported by two sub-questions.The purpose of the main research question is to investigate how sustainable clothing companies can design for circular consumers as well as to create a tool that supports sustainable clothing companies in their design strategies and practices when transitioning to circular business models.

MAIN RQ: How can sustainable clothing companies design experiences that engage consumers in a circular behaviour and role?

Yet, in order to sufficiently answer this main research question, the desired behaviour and role of consumers in the CE has to be defined first. Doing so directly addresses the research gap that was identified both in literature and in the example of Houdini and is pointing out the broadly unexplored dimension of the consumer in the CE (Maitre-Ekern and Dalhammar, 2019; Wastling et al., 2018a). New knowledge is generated that advances the understanding of the consumer in the circular textiles system and thereby allows further development of the system along with adjustment of offerings and services to move forward the much-needed transition.

The first sub-question aims to investigate the phases in the clothing consumption process along with the desired behaviour that consumers need to be engaged in to allow the success of a circular textiles system.

Sub-RQ 1: What circular consumer behaviour is desired in different phases of the circular clothing consumption process?

The second sub-question then builds up on the identified phases and behaviour and addresses more generally the role that consumers are desired to adapt in order to enable a new textiles economy.

Sub-RQ 2: What role does the consumer in relation to other stakeholders have in the circular economy?

To conclude this section, the overall purpose of the thesis is:

to use the Design Thinking framework and methods to collaboratively explore and produce knowledge regarding the behaviour and role of consumers in the circular clothing industry by focusing on the principle ‘Keep products and materials in use’ (Figure 6). It aims to create value for the academic field of Innovation and Design as well as for clothing companies within the EU transitioning to a circular textiles system by creating a better understanding of consumers as key enablers of the circular textiles economy.

Figure 6: Project focus, one of the three pillars of the CE: Keep product and materials in use - Adopted from:

(Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2019)

1.4.

Researchers, collaboration & co-production

With the belief that “designers can play a role in moving towards a circular economy, through their ability to understand and influence business and consumer behaviour” (Wastling et al., 2018), the hope for the researchers is to push the boundaries of how Innovation and Design research is traditionally used and conducted by contributing as designers and researchers in this thesis project. This goes along with the belief that interdisciplinary and collaborative knowledge generation is key to address the complex systems and challenges of society today. The researchers also see opportunities in joint learning and knowledge development processes between academia and the practice. This is why this thesis was conducted as a collaborative and explorative research between two master students and a leading clothing company within the sustainable textile industry.

The researchers role in this research has been to contribute with academic knowledge and methods, as well as moderate and design the creative and iterative research process and its results. Furthermore, their role has also been to unite the knowledge existing within the collaboration partner with the knowledge generated from previous academic research as well as interpreting, analyzing and presenting qualitative data generated through the research process.

Two researchers were working together in this master thesis since it was vital for the chosen research methodology. The work as a pair ensured high quality data collection during exploratory activities. Such research activities demand both a moderator and a transcriber of the research activities since they involve interactive participation in the form of discussions, questions, sketching, note-taking, etc. Besides that, the participation of two researchers allowed the enhancement of the academic contribution of this research project. Each of the researchers contributed with a specific perspective and focus on the problem to the research outcome. The two different focuses were the role of consumers and clothing companies, as well as the behaviour of consumers in the research context. The application of these two different perspectives in the whole research process from literature gathering to planned

research activities, data analysis and produced knowledge enabled a rich theoretical foundation and a broader contribution to both the academic and practical field.

1.5.

Scope & delimitations

It is within the scope of this master thesis to explore and define the consumer behaviour and the role of consumers that is needed for the CE to work. These findings are then used to design a tool that can support sustainable clothing companies in their transition to a circular business model. The thesis solely looks at the CE in regards to the clothing industry and does not address any other forms of textiles or alternative contexts where a linear economic system is currently dominating. Furthermore, a systemic approach within the clothing industry is in this thesis discussed to be crucial to achieve the transition to a CE. This is why a number of crucial stakeholders were investigated in the process in order to get a comprehensive understanding of the consumers and their responsibilities in the context of the circular textiles economy. Nonetheless, this study does not further investigate and include such a systemic approach for change and instead primarily focuses on consumers and how clothing companies can engage them through their practices. Thus, all other stakeholders with their still very crucial roles and responsibilities are excluded from this study and its results. Moreover, when examining the behaviour of consumers, drivers as well as barriers for more sustainable practices and a higher engagement in such practises were investigated. They were, however, just findings that arose from the research process and were not specifically addressed and included in the end result.

1.6.

Thesis outline

Having established the background as well as the aim and purpose of this thesis in Chapter 1, Chapter 2 introduces the applied research methodology by describing the research approach, the research design and the research process including a more detailed presentation of the collaboration partner Houdini. The chapter closes with a discussion about the research quality as well as ethical considerations. Chapter 3 then presents an overview of the key concepts and theories of relevance that build the theoretical basis of this study. Chapter 4 gives an overview of the project process through the description of the conducted research activities and the presentation of the thereby generated key data and findings. Chapter 5 summarizes all the partial process results by providing the answer to the main research question as well as both sub-questions based on empirical and theoretical results. It also explains how the results can be applied as well as addresses their generalisability. Chapter 6 compiles the thesis work with some concluding words before Chapter 7 suggests future research directions to further advance the transition to the CE.

2.

Research methodology

This chapter starts with a presentation of Research through Design, the methodology that was applied to conduct the present research, by describing the research approach as well as its definition and utilization on a strategic level. Followed by that, the exact research design including a more detailed presentation of the collaboration partner Houdini, and the collaboration process will be described before going in detail about the research phases with the thereby applied methods. The chapter closes with a discussion about the research quality as well as ethical considerations.

2.1.

Research approach

2.1.1.

Design science (Research through Design - RtD)

The methodology of this thesis work is based on the principles of Design science. Design research has always focused on issues like innovation, users, materials, production, etc. and has even undergone the development of new fields including social innovation, policy design or design for specific sectors that are also common today. Design is today advocated to be used to work on global challenges and problems like climate change, health, well-being, social justice and urban policy. Furthermore, design researchers are encouraged to address the UN 17 Sustainable Development Goals in global multidisciplinary teams in order to face current worldwide challenges. This is why Design Science was determined to be a very suitable methodology for the aim and purpose of this thesis and the type of complex problem that is addressed in the study. (Cooper, 2017, pp. 8–9)

Design science research is largely associated with a pragmatic philosophy, which considers practical consequences or real effects to be essential parts of meaning and truth. “It is essentially pragmatic in nature due to its emphasis on relevance; making a clear contribution into the application environment.“ (Hevner, 2007). This indicates that design science is different from other renowned research approaches. Nonetheless, as Schön (1992) states:

“Designing and discovering are closely coupled forms of inquiry. Because learning is essential to designing, there is a great potential for learning through designing. The design process opens up possibilities for surprise that can trigger new ways of seeing things, and it demands visible commitments to choices that can be interrogated to reveal underlying values, assumptions, and models of phenomena.” (Schön, 1992, p. 131)

Throughout history, design activities and designed artifacts have become established as important elements in the process of generating and communicating knowledge (Stappers and Giaccardi, 2017). Today, there exist multiple perspectives for describing design research in the literature, which indicates healthy growth and advancement of a field that can be valuable in dealing with the challenges of our times. Still, the field of research is complex; it is distinguished between research for design, research through design as well as research about design and there is a great number of research approaches (Frankel and Racine, 2010).

For this thesis project, research through design (RtD) was chosen as the main way of knowledge generation. The key feature of RtD is its striving to provide explanations or theories within a broader context (Frankel and Racine, 2010). RtD incorporates actions that

can be recognized as design activities from actual design professions and are dependent on the professional skills of designers. “Gaining actionable understanding of a complex situation, framing and reframing it, and iteratively developing prototypes that address it” (Stappers and Giaccardi, 2017) are, among others, named as such activities. Yet, the designerly contribution consists typically of the development of a prototype or artefact which plays a fundamental role in the knowledge generation process. (Stappers and Giaccardi, 2017)

However, not only is the broad field of design research very complex, but there is also an extensive discussion regarding hundreds of approaches for RtD itself. It is a methodology that “is derived from and valuable for practice”. There is a significant contribution of practitioners as well as researchers to both literature and online discussions that result in rapid growth of the field. The majority of the subject matter builds on social sciences, business and marketing, but it is systematic design methodologies that constitute most of the literature regarding RtD. (Frankel and Racine, 2010, p. 6)

Human-oriented design methods appear as a prominent separate area of research in the design field. There exists a “range of attitudes towards human-oriented design, from the expert mindset and the participatory mindset, in both research-led and design-led inquiries”. More traditional approaches (e.g. ergonomics) see design researchers as experts that research and design for users. In more participatory approaches, however, design researchers collaborate with the people they are designing for, making them co-creators in the process. (Frankel and Racine, 2010, pp. 6–7)

Design science addresses the creation of value, among others through artefacts that are practically relevant, but commonly limits the role of practitioners to project phases focusing on evaluation and communication. This is why there is a need “for cross-fertilization between participatory design, action research and design science” and there already exist “initial developments of hybrid methodologies merging action research and design science”. (Alles et al., 2013, p. 107).

In the present master thesis, this need for cross-fertilization was pursued and integrated in the research design. Therefore, the overall guiding methodology of RtD was merged with the principles of interactive research in order to establish a better and more fruitful exchange between the researchers and the collaboration partner.

2.1.2.

Interactive research

Interactive research builds upon Van de Ven’s (2007) research methodology Engaged Scholarship and his “Engaged Scholarship Diamond Model” (Figure 7). This methodology is aimed at the study of complex social problems which are exceeding the personal capability of an individual researcher. It offers a participative research approach that is supporting the acquisition of advice and perspectives of all key stakeholders to reach a deeper and more thorough understanding of the research problem. Such stakeholders can be the researchers themselves, but also users and practitioners. (Van de Ven, 2007)

Figure 7: The Engaged Scholarship Diamond Model for interactive research (Van de Ven, 2007, p. 10) Interactive research is, however, not only a continuation of Van de Ven’s (2007) idea, but originates from a long history of criticism of dominant research approaches as well as a matching interest in other forms of practice-oriented and collaborative research such as versions of action research and participatory research (Ellström et al., 2020, p. 3). Therefore, interactive research can be considered as part of collaborative research approaches (Ellström, 2008). The methodology is characterised by a continuous joint learning process between the researcher and the participants. Yet, not only the collaborative research process is important, but there is also attention on the actual outcome of the research in terms of new theories and concepts (Svensson et al., 2007). Moreover, interactive research holds the ambition of developing honest and mutual relationships both between the researcher and the participants and among the participants. However, as Svensson et al. (2007) point out, these relationships are mainly built up on the researcher’s contribution to practical development rather than on the participants’ contribution to the theoretical work.

Since interactive research is not characterised by particular research methods, various methods can be used for this type of knowledge contribution. Yet, these are mostly qualitative methods such as interviews, observations, focus groups, questionnaires, which are collectively analysed in the process as well as in dialogue seminars or participatory experiences (Svensson et al., 2007). Alles et al. (2013) discuss, however, eight key issues that researchers face when engaging in collaborative design research: 1) choice of implementation partner (IP), 2) choice of projects, 3) managing expectations, 4) building on the expertise of the IP, 5) introducing innovation to the IP, 6) project evaluation and reassessment, 7) cost and resource management, and 8) publishing results.

The present master thesis aims to explore what the most desirable circular clothing consumption behaviour is and what role users play in the CE, in order to determine how clothing companies can design products and services in a way that consumers choose to behave more circularly. Considering the great number of stakeholders playing a part in the creation of such a mindset shift as well as the various factors playing into its successful

completion, this research problem can definitely be seen as complex and too intricate to be solved by one researcher alone. The joint learning process that interactive research suggests is therefore very valuable in reaching a beneficial solution in the problem context of this thesis and will be described in more detail in section 2.2.2 Research context.

2.1.3.

Design Thinking

In this thesis project, Design Thinking (DT) is used as a framework giving guidance for how RtD with the integration of interactive research is applied to solving the research problem. Design Thinking can be described as a paradigm used for solving all kinds of problems within a great variety of professions. It is particularly practiced in the field of Information Technology as well as Business, but there exists a great eagerness for the adoption and application of this practice in other areas (Dorst, 2011, p. 521). This might be one of the reasons why there exist many models and guides of Design Thinking in the literature as well as in practice. The paradigm was initially invented and introduced as an explicit design methodology intending to foster creativity (Thoring and Müller, 2011, p. 137). Brown (2008) defines Design Thinking as “a methodology that imbues the full spectrum of innovation activities with a human-centered design ethos.” Leifer, on the other hand, sees innovation as a solution and Design Thinking as the method increasing the success probability of an innovative solution (Brenner and Witte, 2011). This implies that the paradigm has great potential to be applied in various problem contexts.

There is also a need to explore the impact that human centered design, which is a part of DT, can have in the CE (Wastling et al., 2018, p. 3). Wastling et al. (2018, p. 3) ground this need in the fact that the design of products should not only be aimed at how they fit into a circular economic system, but also how they correspond with the needs, desires and behaviour patterns of people. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation has together with IDEO started to create tools such as “The Circular Design Guide”, which support designers with methods and mind-sets for applying Design Thinking and circular design. The goal of these tools is the incorporation of human-centered thinking when designing circular products and services by the encouragement of designers to acknowledge how users correspond with the system (Wastling et al., 2018, p. 3).

Both researchers have previously worked with DT as a method for both research projects as well as solely design focused projects. Through this personal experience, it was learned that the framework is really strong when it comes to the exploration of so-called wicked problems and the investigation of complex challenges. Examining the consumer as a key stakeholder in the CE as well as identifying a way for clothing companies to design for their active engagement was determined by the researchers to be such a complex problem and therefore suited to be addressed through a DT process. However, there exist multiple views in the literature as well as in practice on how Design Thinking is applied to a project. This is why the purpose of all stages has been defined to show how it was used in the context of this research project. The applied framework is grounded in two sources, Plattner's (n.d.) “design thinking bootleg” as well as IDEO’s (2012) “Design Thinking for Educators” toolkit. Both of these sources suggest a five-step Design Thinking process: Plattner (n.d.): Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype and Test; IDEO (2012): Discovery, Interpretation, Ideation, Experimentation and Evolution. These two frameworks were analyzed and then

merged into one new framework which was used for this thesis. Here follows a description of how the diverse phases of the DT process were defined in this work:

Discover

The goal of the Discover phase is to understand the challenge by investigating the context and familiarizing with the research field as well as the industry and simultaneously Empathizing with stakeholders.

Define

The Define phase is used to clearly define the problem area and formulate a research and design problem with a research question.

Ideate

The focus of the Ideate phase is to generate ideas in order to find an answer or a solution for the research question, both in theory and in practice. The ideation process can be adapted based on the needs and requirements of each project phase.

Experiment

The purpose of the Experiment phase is to select generated ideas and develop them further into research approaches, concepts and/or tangible prototypes, that address the identified problem area.

Evaluate

In the Evaluate phase the focus lies on testing the developed research approaches, concepts and/or prototypes to evaluate their usefulness for all stakeholders and their connection to the defined problem as well as the design challenge.

2.2.

Research design

Now that the strategic level of the research approach has been discussed, this section will present the research context, collaboration and the actual design and its structure with which the research was conducted. As explained, the overlying methodology applied to this thesis work was RtD. It was executed through a combination of the principles of interactive research as well as the DT framework. Houdini served as the main collaboration partner in this process and was through interactive research well integrated in the research process. Moreover, based on the mindset of DT, Houdini customers were also involved in this thesis project.

The following sections will first give deeper insights into the research context of this project as well as the collaboration process and partner. Then the research process and all of its phases will be explained in detail. The section then finishes with a discussion about the research quality.

2.2.1.

Research context

This thesis was realized in a co-productive research context. The two main actors in this collaboration were Mälardalen University (MDH) and the Swedish outdoor clothing company

Houdini. On the side of MDH, two main stakeholders were involved: the two main researchers and authors of this thesis, as well as two supervisors working in the department of Innovation and Product Realization at MDH. One stakeholder from Houdini was its CEO, Eva Karlsson, who was the company supervisor of this thesis. Besides her, a number of other employees from different departments and specialities were involved in the project process. While the university supervisors were responsible for the academic part, the company supervisor was accountable for the practical part of the previously described project aim.

As a third party, Houdini customers were involved in the research context. This inclusion ensured the integration and consideration of the perspective of the central target group for which the project outcome is ultimately aimed at. However, since this research aims at exploring a type of behaviour and role that is not yet the norm, the inclusion of users mainly intended to understand the current behaviour and opinions of Houdini users as well as to identify barriers and drivers for behaviour change. Above that, the active integration of users by, for instance, letting them co-create solutions, can by itself contribute to the development of systemic change that is vitally needed for sustainable identities (Collins et al., 2020). Figure 8 visualizes the research context and is based on the model of a co-production process by Sannö et al. (2018). The thesis authors share a common problem with the company Houdini, which is addressed through collective resources and collaborative work. The outcome of this process is new knowledge in the form of the present thesis. This knowledge is beneficial for both involved parties, the academia as well as the industry and simultaneously also creates value for the society as a whole.

Figure 8: The research context showing project stakeholders and value creation process