Do you talk to your child about social media?

An empirical study about Danish parents’

communication with their children about

Social media: Engagement, Concerns and Fears

Signe Normann Kristensen

Media and Communication Studies

One year Masters

15 credits

Spring, 2016

Abstract

The aim of this study is to research how and if Danish parents communicate with their children about the use of social media. The motivation for this study is based on the findings from the EU Kids Online report from 2014, in which 25 European countries have participated. Their research focused on children, whereas my study is concentrated on the parents.

My empirical data is based on a questionnaire and follow-up interviews. The questionnaire has 193 respondents and from these, I chose three for follow up-interviews.

The theoretical framework is mediatization, parental mediation and moral panic. Mediatization theory is concerned about the media and other social relations. Therefore, this theory is relevant, as this study has focused on how parents communicate with their children about social media and how this affects the family life. Parental mediation encompasses three strategies for communicating about social media. In this way, the theory has provided an understanding and explanation on how parents deal with their children being on social media, and it was important for the majority of the respondents to talk about it. The last theory is moral panic. This was found to be a helpful theory for the analysis, as many of the respondents expressed concerns and fears about their children being on social media throughout the questionnaire.

It can be concluded from this research that parents are very different regarding how to communicate about social media. Despite the age-restriction many of the parents allow their children to be on social media. However, many of the parents have and do create some restrictions for their children, so they can use social media platforms. Overall, there seems to be a strong involvement for the majority of the parents in relation their children’s use of social media.

Even though many parents have talked with their children about social media, there are still

concerns and fears about the use of social media. One of the new problems is in relation to the fear of their children sharing content of a sexual nature.

This concern might departure from the fact that children see what teenagers do, and, furthermore, face a lot of sexual toned content through media. It should be discussed, how the increasing tendency among children to share sexual content, is due to a lack of focus on content sharing on social media.

Keywords: Social media, Children, technology, mediatization, moral panic, parents, parental mediation

Table of content

1. Introduction 3

2. Context 4

2.1 Danish people’s access to Internet and Social Media 4

2.2 Danish Children’s access to the Internet and Social Media 6

2.3 Social media – a definition and description of different social media platforms 7

3. Theory and existing research 9

3.1 Mediatization 9

3.2 Moral Panic Theory 10

3.3 Parental Mediation 10

3.4 Existing Research 12

4. Methodology and Data 14

4.1 Research paradigm 14

4.2 Quantitative-‐ and Qualitative Data 14

4.3 Data collection 15

4.4 Questionnaire 16

4.5 Order of the questions and tools used for the questionnaire 16

4.6 Semi-‐structured follow-‐up interviews 17

4.7 Transcription of follow-‐up interviews 18

4.8 Method of analysis 18

4.9 Ethical concerns 19

5. Results and analysis 20

5. 1 Awareness of children’s use of social media 20

5.2 Communication about social media 25

5.3 Communication strategies about social media 27

5.4 Parental Mediation: Active Mediation 28

5.5 Parental mediation: Restrictive mediation 29

5.6 Parental Mediation: Co-‐using 32

5.7 Concerns and fears 33

5.7.1 The fear of bullying 33

5.7.2 The fear of strangers and revealing of private information 35

5.7.3 The fear of nude pictures and pedophiles 35

6. Analysis and results follow-‐up interviews 36

6.1 Background about the three interviewees 37

6.2 Communication about Social Media 37

6.3 Parental mediation: All three strategies 38

6.4 Concern and fears 39

7. Discussion 41

8. Conclusion 44

9. Bibliography 45

10. Appendix 47

1. Introduction

Today, there are more and more opportunities online. Every day people spend hours behind the screen and on mobile devices, which allows them to explore, chat and interact with others. The digital life keeps expanding. People bring their mobile phone to meetings, they chat with their colleagues, they create parties through events on social media platforms, they find their soul mate through dating-sites, people play online games with their friends etc. Yes, the digital era has provided people with endless opportunities to interact with others.

Recently, my ten-year-old cousin asked me, if she could add me on Snapchat and get my Instagram name. I was very surprised. Even though she was standing in front of me with her Apple iPhone, I had no idea; she used it for Snapchat or Instagram. However, this seems not be unusual for Danish children.

A report, EU Kids Online from 2014 shows that Danish children begin having social media accounts, when they are 7-8 years old (Stald, 2014). It seems to be normal that children have their own cell-phone, tablet and computer. It can be assumed that with the normalization of children having their own technological device, there must be a change in the social dynamics in their daily lives.

Most social media platforms have an age-restriction of 13. However, this seems to be ignored. Children will make an account anyway or get help from their parents.

When I think about my 10-year old cousin, my first thought was that she was not old enough to use these platforms and she definitely does not know how to use them. I do believe she is more

technological skilled than me, beside that I have my doubts about she is on these social media platforms such as Instagram, Snapchat and so on.

This makes one wonder about the consequences and risks that children can experience online. Especially, since the news frequently shows stories about children and cyber bullying on social media, children receiving inappropriate material, or children who are contacted by people with bad intentions. In the past few months there has been published a fair share of stories in the news on how the Danish police have cases, in which children as young as eight have taken pictures of themselves in a sexual nature (Rosendahl, 2016).

This made me wonder how parents deal with their children being on social media. Do parents talk to their children about how to behave on social media? Do children get guidelines from their parents? Do parents check what their children are posting on social media platforms? Many studies focus on the children’s and teenager’s use of social media. A lot of research also focuses on the

will include how involved parents are in their children’s use of social media and how they talk about the use of social media. The aim of this study is how parents’ involvement in their children’s online lives can lead to communication about social media and despite the communication or the lack thereof, which concerns and fears it raises. Therefore, this thesis has the following questions for further research.

Problem formulation

How are Danish parents engaging in and communicating with their children on how to behave on social media and which concerns and fears does it raise among parents that their children are on social media?

Research Questions

• Are parents aware of their children’s use of social media? • Do parents communicate with their children about social media? • How are parents communicating with their children about social? • How much are parents involved in their children’s ‘online’ life? • Which concerns and fears do parents have?

2. Context

The following section will provide some information about the Danish society and how important the access to the Internet is. First, it will describe the adults in Denmark and their use of the Internet and social media in general. This will be followed by general information about Danish children’s access to the Internet and social media.

2.1 Danish people’s access to Internet and Social Media

Information Technology (IT) has a major impact on Danish people’s daily life, as it is required of them to be able to be on the Internet in order to receive written information from the public sector. The goal for 2015 with the public digitization strategy was that 80 percent of the Danish population should communicate with the public sector digitally (Wijas-Jensen 2014:6). Therefore, it is

essential for the Danes to have access to the Internet. The development of digital opportunities seem to be expanding in areas such as online-shopping, streaming and finally platforms, which allow communication with family, friends and colleagues. Furthermore, devices that have access to the Internet are developing as well. More and more Danes acquire smart-phones, tablets and

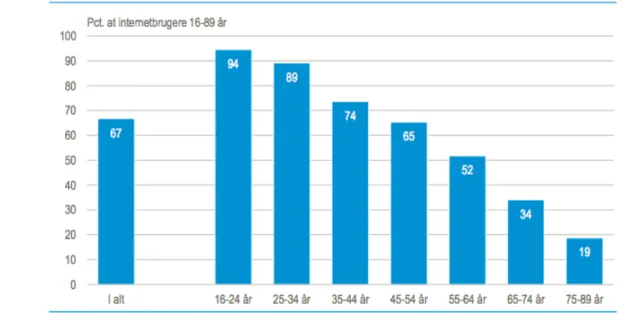

This section is based on a report by Statistics Denmark in which they have collected data from people in the age-range 16-89 years. Their data comes from telephone-interviews and surveys among 5457 people from March-May in 2014. (Wijas-Jensen 2014: 44). These people were chosen, in order to have a representative segment of the Danish population. In the report from Statistics Denmark by Wijas-Jensen (2014), it states that 94 percent of Danish families have access to Internet in their homes (Wijas-Jensen 2014: 7). In addition, the report asked people if they had a Facebook account, in which 95 percent of the participants said yes (Wijas-Jensen 2014: 19). The other platforms such as Instagram and Twitter are not as commonly used. Therefore, Facebook is the most popular social media platform among adults in Denmark. Figure 1 underneath is from the report and shows the age groups more specifically and illustrates how many people use social media platforms. It should be noted that figure 1 has taken all social media platforms into account.

Figure 1: Danish Adults on Social Media Platforms 2014 (Percentage of Internet users from 16-89 years of age)

(Source: Wijas, Jensen 2014: 19)

In the bottom, they have divided people into age groups. The pillars show the percentage of use of social media platforms in the specific age group. The pillar on the left is ‘total’.

It is clear to see that the users of social media platforms decrease as the age increases. Figure 1 gives a high indication that many Danish adults are users of social media. However, it is assumed that parents might be mostly familiar with the Facebook platform, which can cause some

complications for parents, in the sense that they are not familiar with the (other) social media platforms that children use.

2.2 Danish Children’s access to the Internet and Social Media

The report, EU Kids Online, from 2014 shows that 98 percent of Danish children in the age 9-16 have access to Internet at home (Stald, 2014). Gitte Stald, an associate professor at the IT

University in Copenhagen, has been in charge of the results from Denmark in the EU Kids Online report (Denmark, 2014).

The participating countries include 25 European countries (EU Kids Online 2014,). Overall, Danish children are above average when it comes to experiences and communication online. First of all, Danish children on average start being online daily and being present on social media, when they are 7 years old compared to an average of 9 years in the rest of the participating countries (Stald (b), 2014). This is a relatively young age to start being on social media platforms, when most them have an age-requirement of 13.

The EU Kids Online report has focused on what children are experiencing online both positively and negatively. One of the major problems about communicating online is the risk of receiving and being contacted by unpleasant people who send inappropriate material. There have been many cases in Denmark about this and the EU Kids Online report concludes that 56% of the asked Danish children have had a negative online experience. This is in comparison to 41% of the rest of participating countries (Stald (b), 2014). Negative material takes all aspects into account such as receiving sexual material, having been in contact with strangers and etc. Danish children are above average in all of the asked risk questions (figure 2 underneath).

Figure 2: Danish children compared to European countries

Source: Stald, G (b). (n.d.). Danish Kids Online. 1st ed. [PDF] Available at:

http://www.lse.ac.uk/media@lse/research/EUKidsOnline/ParticipatingCountries/PDFs/DK%20NordMediaStald.pdf [Accessed 11 May 2016].

In figure 2 it is clear to see that Danish children are above average compared to the other

participating European countries. This is interesting as it can indicate the following assumptions: Danish children are more honest about if they have experienced something negative; Danish

children are easier to target because they are very young when they start being present on social media; Danish children have not received information on how to use social media platforms and being aware of risks online. Many assumptions can be drawn from the numbers in figure 2. In the report by EU Kids Online they have also made questionnaires targeting the parents to ask children about the risk(s) that they (the children) can experience online. The findings are

interesting, as most parents do not think that their children have experienced something negative or harmful. The following numbers include all the participating countries in EU Kids Online:

• 40% of the parents, whose children have seen sexual material online, do not think they have.

• 52% of the parents, whose children have received sexual material, say that their children have not.

• 61% of the parents, whose children have met an online contact face-to-face, say that their children have not (Stald, 2014).

This gives an indication that many parents are not aware of their children’s online life. Furthermore, it could also give an indication that many children are afraid to tell their parents about what happens online.

2.3 Social media – a definition and description of different social media platforms

Social media platforms allow people to communicate online. There are many definitions of social media; however, in this thesis the definition of social media will depart from the following:

“We define social network sites as web-based services that allow individuals to (1) construct a public or semi-public profile within a bounded system, (2) articulate a list of other users with whom they share a connection, and (3) view and traverse their list of connections and those made by others within the system. The nature and nomenclature of these connections may vary from site to site.” (Boyd & Ellison, 2007: 211).

Social media provides a way to interact with people; including people you know and those you do not know (yet). There are many online social media platforms and some of the most popular sites will be explained below, including those sites children mostly use.

Facebook is a social media platform, which provides the users several types of involvement and interaction. This means that the user can share pictures, videos, statuses, links and other kinds of content. The potential to share content on Facebook is very large. By agreeing to their terms of

Friv

Friv is not a social media platform, but a place where children can play online games. The platform does not allow any communication among the users (“friv.com : Privacy Policy”, 2016). There seems to be no age restriction on this site. However, a lot of the parents have mentioned this as a platform that their children use, which is why it is included here.

Instagram is a platform, which allows the users to upload-, share- and see pictures and use hashtags. It also contains the feature to send private messages. Instagram only allows people older than 13 to have an account and they have a list of guidelines to which kinds of pictures are appropriate for using their platform (“Terms of Use • Instagram”, 2016). Furthermore, Instagram states as follows in their privacy policy, “The Service and its content are not directed at children under the age of 13” (Instagram, “Privacy Policy”, 2016).

Momio

Momio is a social media platform for children, which allows them to make friends, share pictures, share videos and write messages (“Momio | watAgame - Social Media for Kids”, 2016). This platform wants to be the children’s first and foremost go-to social media and provide them with a safe environment (“About us | watAgame - Social Media for Kids”, 2016). Momio is only for children and therefore you have to be less than 18 years old to use this platform. Momio state that it is okay for parents to create an account in order to see what their children are doing, but that they should not actively use Momio for other purposes. Furthermore, Momio has moderators, who make sure everything is secure and safe (Rules on Momio | watAgame - Social Media for Kids, 2016).

MovieStarPlanet

MovieStarPlanet is a social media platform for children between 8-15 years old. They describe themselves as a safe entertainment social media platform for children (“Om”, 2016).

MovieStarPlanet is social universe, where the user is a movie star. In this way MovieStarPlanet describes them selves as part game and part fantasy world with many social network functions (“Om”, 2016). One of the features is to share pictures with friends as MovieStarPlanet sees it as way to be creative and express hobbies and other interests on MovieStarPlanet (“Forældre”, 2016).

Snapchat

Snapchat is an application, which allows the user to send and receive instant pictures and videos. The pictures only last for a maximum of 10 seconds and can be seen only twice. If we ignore the

fact that you actually can take a ‘screenshot’ of the picture send to you. The same applies for the videos. Snapchat will not allow children below the age of 13 to use their service. Their website emphasizes that some of their services should only be used by older people and they therefore encourage you to read the terms of service carefully (“Brugsvilkår • Snapchat”, 2016).

Now, that the social media platforms have been described, the following section will describe the theoretical framework.

3. Theory and existing research

The new kinds of devices such as tablets, smart-phones and laptops have changed the landscape of family media use (Clark, 2011: 324). The theoretical framework consists of mediatization; parental mediation and moral panic, and they are the major theories for this thesis. The theories are chosen because of the relevance for analyzing parents involvement and communication with their children about social media.

3.1 Mediatization

As mentioned in the introduction, Danish citizens are required to have access to the Internet in order to communicate with the public sector. In addition, it can be also be a challenge for children not to go online as communication and social interaction with their friends and classmates has moved to online platforms as well.

In the last decade, mediatization has become an important concept and theoretical framework to understand the interplay between media, culture and society (Hepp, Hjarvard and Lundby, 2015: 314). Furthermore, mediatization looks at the long-term changes in culture and society, where the media is a part of changing the terms for communication and interaction between us (Hjarvard, 2016:8). The theory of mediatization takes point of departure from Media Studies and is therefore from this tradition of research, which grounds the definition of media in mediatization theory (Hjarvard, 2016:20). Media is understood as technologies, which enable people to communicate in time, space and modality. In mediatization there is a broad media perception, which include mass media, interpersonal media and social media platforms (Hjarvard, 2016:20). These three

perceptions of media all have a technological aspect, which is important to have in terms on how to define media in relation to mediatization. However, the technological aspect is not the only part of media. In order to understand media, we also need to think about the function it has in relation to

include technological, aesthetics-symbolic and institutional angles need to be taken into account, when one wants to understand how media plays together with other cultural and societal

phenomenon (Hjarvard, 2016:20). Therefore this theory relevant to my study as I want to

understand the communication parents has with their children about social media. Social media is a media, which can be argued to plays together with cultural and societal phenomenons.

In other words, mediatization theory is about how media, culture and society interact with each other and thereby how the media is a part of how people, in the overall society and in their daily life, communicate, act and create social relations (Hjarvard, 2016).

3.2 Moral Panic Theory

Moral panic theory is a relatively old theory. One of the most influential work on moral panics is Stanley Cohen’s work, “Folk Devils and Moral Panics” from 1972. Stanley Cohen (1972) defines moral panic:

” A condition, episode, person or group of persons emerges to become defined as a threat to societal values and interests; its nature is presented in a stylized and stereotypical fashion by the mass media” (Cohen, 1972:1).

Furthermore, Cohen describes that the object of the moral panic can be something that has existed for a long time and suddenly surfaces in the spotlight (Cohen, 1972:1). In addition to this, when a new cultural, media development or an emergent technology emerges, it revives previous anxieties about the safety of children and youths. When this fear spins out of control, the moral panic is produced (boyd, 2014). boyd argues that moral panics revolving around children are often centered on “sexuality, delinquency and reduced competency” (boyd, 2014: 105). Since this definition of moral panic emerged in 1972, Cohen has continued to work on it and argue:

“We can easily see that changes in information technology and the massive potential of social networks alone would account for the ease and speed with which the stages of moral panics can be transmitted and constructed” (Cohen, 2011: 239).

The abovementioned moral panics often trigger new anxieties (boyd, 2014: 105). This means that moral panic is a theory there is focused on when people do believe that something threatens the social order (boyd, 2014:105). Therefore this theory can be used for this study as it looks at the concerns and fears, which parents has in relation to their children use of social media.

3.3 Parental Mediation

Since early communication research, it has always been the researchers’ interest to study “parental efforts to mitigate negative media effects on children” (Clark, 2011: 323). Before describing this theory, it should be noted that it originally addressed the impact on children from television. This means that the theory was made to understand how parents were dealing with and managing an active role with their children’s experience with television and therefore, it has some limits. Parental mediation is a three-dimensional construct, which includes three different types of behavior: active mediation, restrictive mediation and co-viewing (Nathanson, 2001: 201-202). These behaviors have been discussed broadly between many scholars. According to Livingstone and Helspher (2008) these behaviors can be applied to all media. The word ‘mediation’ should be understood as how parents manage their children’s relationship to media (Livingstone & Helspher, 2008: 581).

The first behavior is active mediation. Here the parents talk to their children about the media content while engaging with the medium. Engaging entails watching, reading or listening to the media content. In this mediation it includes positive, negative, instructional and critical forms of mediation (Livingstone & Helspher, 2008: 583). The next mediation is more concerned with setting rules that restrict the use of the medium. This mediation is called restrictive mediation. It includes all types of restrictions such as time spent, location or use. One of the important restrictions it focuses on is content, which means restricted exposure to violent or sexual content. This mediation discusses the meaning or effect of the content. (Livingstone & Helsper, 2008: 583). The last mediation that Livingstone and Helpser (2008) use, is the word co-using, which will be used throughout this thesis as well, because their definition applies more to social media rather than the ‘original term’ co-viewing. Co-viewing is mediation, when is described as the parents watching TV with their children (Nathanson, 2001: 202). In co-using the parents are present, while the child is engaging with the medium, but share the experience without discussing and commenting on the content or its effects (Livingstone & Helsper, 2008: 583).

According to Clark (2008), the three behavior strategies have some differences in the way they are being communicated. Active mediation is an important dialogue between parents and their children whereas co-using is primarily a nonverbal communication as the parent is only co-presence.

Restrictive mediation involves a parent-to-child communication in the form of the rule making and what the consequences are, if the rules are not followed (Clark, 2008: 326).

There are a few things, which should be noted to these behaviors, as they were not developed for other media than television. As Livingstone and Helsper (2008) argue, the Internet might create

have more anxiety towards their children’s use of the internet due to content provided online such as violence, pornography and the fear of children getting in contact with strangers (Livingstone & Helspher 2008: 583).

There has been done a lot of studies on parental mediation and many of them conclude that parents often underestimate the influence of media on their children compared with how they estimate the influence on media on other people’s children (Clark, 2008: 327).

3.4 Existing Research

This study will specifically focus on Danish parents’ communication and engagement about social media with their children and this section will give a brief overview on existing research, which has relation to my research.

Danah boyd’s (2014) “It’s complicated”, studies why social media has become a central part of teenagers’ lives. boyd’s focus is on America’s teenagers and how they navigate the networked publics, which are created through technology. Furthermore, boyd argues that her research is a critical illustration of teenagers’ practices, habits and the tensions between teenagers and adults (boyd, 2014: 5). Her research provides an insight into the networked lives of youths. It is relevant for this study because she also focuses on American adults’ fears in relation to teenager’s

enthusiastic engagement with social media. boyd’s aim is to shed light on the complex practice of contemporary American youths’ search for their identity in a networked world (boyd 2014:xi). boyd’s motivation for this research stems from her recognition of how teenagers’ voices shape the public discourse regarding their networked lives. Furthermore, boyd argues that many people discuss teenagers’ excessive engagement in and with social media, but no one takes the time to understand why teenagers are so engaged with it, which is why boyd wanted to focus on that gap (boyd, 2014: x-xi).

Another study, which focuses on children, is Sonia Livingstone’s (2009) “Children and The Internet”. In this study Livingstone (2009) argues that the changes in the media landscape and the expansion of opportunities online, has altered the opportunities and risks for children and youths. The media landscape has also changed the communication between children and adults, Livingstone argues (Livingstone, 2009:vii). Furthermore, Livingstone has also observed the anxieties associated with children’s use of the Internet. Therefore, it could be argued that Livingstone’s research also focuses on moral panics. One of the conclusions Livingstone’s draws is that the complex media landscape and communication environment is contributing to how our identities are being shaped,

how we learn, our culture and the conditions in order to participate in society (Livingstone, 2009:232). Therefore, it can be argued that it is difficult to live with out it and the next generation of children will be a part of it as well. Livingstone does not delve into whether or not children should spend more or less time on the Internet. Rather, she focuses on the perspective in which the children can benefit from the Internet (Livingstone 2009: 232).

Another interesting study relating to this is “Årgang 2012” by Søren Schultz Hansen (2011). He has been conducting empirical research, where he has been interviewing children from the year 1994. These children were selected from two elementary schools in Copenhagen. The interviews were a mixture between individual- and focus groups interviews (Schultz Hansen, 2011: 187). All of them were semi-structured and loosely prepared with a few activities, which induced the children to use their social media platforms and mobile phones. Besides the interviews, Schultz Hansen (2011) also conducted interviews with people ranging from 30-50 years old (Schultz Hansen, 2011: 187). By doing this he was been able to look at the differences between these two sets of generations. He made conclusions on how the children looked differently at certain behaviors compared to the older generation and how this would effect the future, e.g., in work places, families and etc. Schultz Hansen’s (2011) research gives an indication as to how adults, who have not grown up with social media compared to the next generation, who have never experienced a world without it, have different practices. Furthermore, by incorporating at the older generation in the study, in which some of the interviewees give some critical reflections regarding children’s use of social media and new media, provides a more in-depth picture.

Fleur Gabriel (2014) proposes in his work “Sexting, Selfies and Self-harm: Young people, social media and the performance of self-development” a review of popular arguments in relation to young people’s use of media and how this usage comes into conflict with the broader

developmental discourse. In his paper he discusses the conception that social media engagement is negative for young people in the process of self-development (Gabriel, 2014: 104). Gabriel (2014) proposes that this conflict contributes to the perception of young people’s use of media is dangerous for a healthy development and further suggests a different approach is needed for young people (Gabriel, 2014: 104). Gabriel (2014) expressed concerns about cultural sexualization, where he argued that the trends among young people on social media, where they communication with sexual content (called sexting) compress childhood and adolescence and accelerate development especially the sexual development (Gabriel, 2014:105). In addition Gabriel (2014) argues that teenagers and

exposed on social media and can be found on the wider media sphere. Gabriels argument is, that in their developmental process they are not sufficiently mature in order to understand the

consequences (Gabriel, 2014: 106). In short, Gabriel’s article from 2014 addresses the perception that social media can be a negative influence on children and teenagers’ self-development.

These existing researches and studies have different approaches. What they all have in common is their focus on social media, young people and the usage of social media. Therefore, each of them is relevant for this study.

4. Methodology and Data

This thesis will contain both quantitative and qualitative data. The main data is quantitative as it allows a broader reach to a larger population and enables one to look for characteristics and patterns among the respondents. The qualitative data will help the analysis with an elaboration on some of the themes and patterns, which were found in the quantitative data from the respondents, which the quantitative data cannot do alone.

The methods and data collection will be described underneath.

4.1 Research paradigm

This study will be working under the research paradigm of interpretivism. Interpretivism is

associated with the philosophical position of idealism, which means it can be grouped together with hermeneutics;” approaches that reject the objectivist view meaning resides within the world

independently of consciousness” (Collins, 2010:38). Interpretivism is not an objective reality, “but rather to understand the world as it is experienced and made meaningful by human beings” (Collins, 2010: 39). Through this research paradigm it is my choice as a researcher to decide, what is relevant for the problem to be investigated (Blaikie, 2007: 124). Interpretivism requires an understanding of the social world, in which the people have constructed the reality and in which they reproduce it through their continuous activities (Blaikie, 2007: 124). Furthermore, people are constantly

interpreting and reinterpreting their world (social situations, their own actions, other people’s action etc.). People create meanings for their activities (Blaikie, 2007:125). For a researcher, this means that they have to keep in mind that the people already have interpreted their social world and thus, attempt to understand their understanding of their social world.

4.2 Quantitative-‐ and Qualitative Data

A quantitative method is used, when the data is converted into numbers for analysis (Blaikie, 2003: 47). The main source for the analysis will be the data from the already conducted questionnaire. The follow-up interviews have been conducted with three of the respondents from the

questionnaire. The follow-up interviews will be the qualitative data and an interview-guide was made (see appendix 2). However, it should be noted that the questionnaire also included open-ended questions, which allowed the respondents to freely write answers.

Even though the interviewees in the follow-up interviews already were aware of the topic due to the fact that the persons had answered the questionnaire an interview-guide was still made (see

appendix 2). The following sections will elaborate on the methods used regarding the questionnaire, follow-up interviews, transcription and the method used for the analysis.

4.3 Data collection

The questionnaire had 193 respondents. It was shared in two elementary schools in Denmark, which are located respectively in the northern part of- and in the capital region. This was done through their internal working space and the teachers’ Facebook page. Furthermore, the questionnaire was shared through the researcher’s Facebook and LinkedIn account while encouraging ‘connections’ to answer and share it. A Danish school was chosen due to the focus being on Danish parents. The data collection method was thus a mix between convenience- and random sampling. The benefit from using convenience sampling was that it provided a large amount of data in a short amount of time (Collins 2010: 179). After this it became a random sampling as it was shared through different social media platforms and therefore, disabling personal selection of those who participated in the questionnaire or who had shared it.

Another benefit of choosing a questionnaire is that the researcher can avoid interview-bias (Collins, 2010:128). In this case it is important to mention, that one of the above-mentioned teachers is the researcher’s family member and she might know some of the respondents as the questionnaire was shared on her own Facebook and LinkedIn page.

Most of the respondents live in the region of Copenhagen, the capital of Denmark (62,2%).

Followed by the region Northern Jutland, which is 23,3% of the respondents. When it comes to the age of the respondents, there is a good variance in all of the age groups, but 30,1% of the

respondents are mainly 41-45 years old. Their educational status is mostly between ‘medium long education’ (nurse etc.) and ‘long term education’ (master-degree etc.). These two groups cover 34,7% and 36,3% of the respondents (see appendix 3).

selected by draw lots by using the generator called radom.org (RANDOM.ORG- True Random Number Service, 2016). The numbers 1-38 were randomly assigned to participants and then the generator picked three numbers. This secured the avoidance of researcher bias. The three

interviewees were contacted via e-mail and asked, if they were still interested in an interview and they all consented.

4.4 Questionnaire

This section will describe the thought process of choosing the questionnaire as the main method to gather empirical data.

As written before, the questionnaire would allow a wider reach to a larger population sample. However, even though this was chosen, one cannot control, who or how many answers the

questionnaire (Collins, 2010:128). This could have been a problem as the target group was parents of children in the age 6-15 years old. The questionnaire was anonymous, but space had been made for the respondents to add contact information, in case of the need to conduct follow-up interviews. It was the wish that the respondents did not to feel obligated to fill out the contact information, as there is a basic understanding from the researcher’s point of view that parenthood can be a very personal matter and it could cross one’s boundaries when answering some of the questions. The focus will be on Danish parents and the questionnaire has been conducted in Danish and has been translated into English, when necessary for the analysis. In this way, it was assured that the parents fully understood the questions and avoided non-Danish speakers replying on the

questionnaire.

The following section describes the order of the questions in the questionnaire.

4.5 Order of the questions and tools used for the questionnaire

The questionnaire is listed as appendix 1 in the end of the thesis.

The questionnaire started with some closed questions, as these questions enabled the retrieval of factual information (Collin, 2010: 130). The closed questions provided a differentiation between the respondents in the analysis. Most of the questions in the questionnaire are closed, due to the

quantitative method.

The questionnaire then switched between closed and open questions (see appendix 1). The open questions came after a closed question. By structuring the questionnaire in this way it was avoided that all the open-ended questions were in the end, and risk the respondents finding it too

complicated and time consuming to answer them. One weakness about open questions is that there can be many different answers and these need to be summarized and coded (Collins, 2010: 131).

The questionnaire was conducted through a tool provided by Google Analytics. This tool gave the option of seeing both the overall data and see, what each respondent has answered. This enabled the data from the closed questions to be imported into Microsoft Excel in order to make graphs and tables as well as calculate the percentages. Percentages were chosen as the metric, because they are easier to read than much else (Blaikie, 2003:60). While looking for characteristics among the respondents it was important to se the data in tables, as it enabled a distinction between the characteristics. Furthermore, by being able to see each respondents answer, it enabled extra examination of the data, i.e. if the respondents had indicated corrects answers e.g., if they had answered 1 child, if they had checked off the following question about, if their child used social media. The figures will both show the percentage and the number of respondents.

In the analysis the quotation will be referred to as follows: (Appendix 3: question number, quotation number), for example: (Appendix 3: 13. 24). All the results can be seen in appendix 3, which also includes all the comments from the respondents.

Personal information such as their e-mail and phone number has been left out to protect their anonymity.

4.6 Semi-‐structured follow-‐up interviews

A semi-structured interview is close to an everyday conversation, but comes out as a personally interview. This means that it focuses on a specific theme and has suggested questions, but it allows follow-up questions (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009:27). The interviews were conducted in Danish and the respondents were two women and one man. Before every interview, questions had been

prepared and adjusted for each interviewee (see appendix 2). As the interviewees were randomly picked from the respondents, their answers were examined in order to make the adjusted questions. Therefore, there are different interviews-guides for each interview, and these are listed as

appendixes (see appendix 2).

The semi-structured research interview approach was used, as it focuses on the interviewees’ experience of a theme (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009:25). Moreover, a semi-structured interview attempts to understand the interviewees’ own themes of the lived everyday life from the interviewee’s own perspective (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009: 27). The interviews provide an elaboration of the questions posed to the parents about their communication with their children about social media from their perspective.

4.7 Transcription of follow-‐up interviews

The follow-up interviews were done through phone-calls and therefore, the recordings of the interviews are only available as audio. “Transcribing interviews from an oral to written mode structures the interview conversation in a form amenable closer to analysis” (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009: 180).

The interviews were, as mentioned earlier, conducted in Danish and therefore the transcriptions are made in Danish as well. All the transcriptions can be found as appendixes and only quotations used in the analysis will be translated into English (see appendix 5+6+7). It is important to have in mind that transcribing audio recordings includes a number of technical and interpretational issues. This is especially in relation to verbatim oral versus written style (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009: 180). As Kvale and Brinkmann (2009) state, “there are not many standard rules, but rather a series of choices that have to be made” (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009: 180).

In some cases there have been noise or other interferences, which made it impossible to hear what the interviewee said and this has been marked a “mumbling”. For the transcription all the words the interviewees said have been included. However, certain noises have been left out such as “laugh”, “cough” and so on.

The follow-up interviewees will be referred to as following Woman 1 (Appendix 4), Woman 2 (Appendix 5) and Man 1 (Appendix 6). All of them will be referenced as follows (Appendix X: L. X-X). For example: (Appendix 6: L. 4-5).

4.8 Method of analysis

The quantitative data is, as mentioned before, based on the questionnaire. The conclusions in the analysis will be from the points of view from the respondents and not generalizable for the whole population in Denmark. Therefore, the analysis will be a univariate descriptive analysis of the data. This method is concerned with summarizing the characteristics of the data (Blaikie, 2003:47). The analysis will describe the characteristics of the respondents of the questionnaire, which is relevant to answer the overall problem formulation. In this relation, themes have been uncovered, which include the relevance for the parent’s engagement, communication, concerns and fears.

As mentioned earlier the questionnaire had 193 respondents. 75,1% of the participants were women and 24,9% were men. This means that the analysis can only conclude from their reflections, but it can still provide a better understanding of parents’ communication with their children about social media and comparing to the findings from EU Kids Online, as they have not included elaboration

from the parents or made interviews with parents. Statements and reflections from the questionnaire will be used in the analysis. These will be analyzed in relation to the theoretical framework.

The first analysis will only be based on the questionnaire and then followed by an analysis of the follow-up interviews.

Furthermore, the three interviews were different according to their answers in the questionnaire. The interviewees were asked to elaborate on some of their answers from the questionnaire. The findings from the follow-up interview will be presented after the analysis of the questionnaire. The aim of this analysis was to find characteristics and differences. Moreover, it will be looked into how some of their personal experiences have affected their involvement and communication with their children about social media. In this part, themes relating to engagement, communication, concerns and fears were looked for.

4.9 Ethical concerns

This study aims to understand how parents communicate with their children about social media. This topic can be argued to be sensitive matter, which entails some ethical concerns regarding this. Despite the questionnaire was voluntary to participate in, some might find some of the questions too personal. Therefore, all the closed questions included an answer alternative for the respondents to choose “Do not wish to answer”. The questionnaire ended by asking if the respondent wanted to elaborate his/her answer in an interview and promised continued anonymity.

For the transcription, choices were made to only transcribe questions and answers. This means that there are certain passages of the interviews, which have been left out as they contained personal information and therefore the anonymous aspect would not be possible. Furthermore, before every interview started, a brief description on how the interview would be held was provided and the interviewees were given opportunity to ask questions about the interview. This has not been transcribed.

Some ethical concerns can also be raised in relation to the research paradigm, interpretivism. For instance as a researcher, one might have some subjective insights, which in interpretivism and social constructivism paradigms seem to be valuable rather than a weakness to the study (Collins, 2010: 39). In other words the researcher can contribute with experiences and insights, which seem to be useful when trying to make the research evidence more understandable for others. However, despite the value of being subjective, it should also be noted that this could affect the research, and make the researcher seem biased. The effort to avoid biasing the questionnaire and interviews, might impossible due to knowledge in this particular field form previous research. Furthermore, in

children have started to share sexual content among each other. This can have affected the questions regarding the concerns about uploading material on social media.

5. Results and analysis

In this section the most interesting findings in relation to the theories chosen will be highlighted in order to answer the research questions and problem formulation. The analysis is structured in the order of the research questions, which was presented in the introduction. Differences between men and women will not be analyzed.

The aim is to display the communication that parents have with their children, how they tackle fear, how engaged they are as well as which concerns they have about their children’s use of social media.

The questionnaire will be analyzed in relation to the patterns found among the respondents. The first section will focus on some of the factual elements in order to understand the background of the respondents. Then the analysis will be divided into themes, which are about the parental mediation and moral panic. In both of these themes mediatization will be included. After the analysis of the questionnaire, the follow-up interviews will be analyzed. Their similarities, differences and elaboration on some of the questions from the questionnaire will be the focus of this analysis.

5. 1 Awareness of children’s use of social media

The questionnaire began by establishing the background of the parents and how many children they have in each age group. After the parents have crossed off, which age group their child/children belongs too, they needed to answer if their child/children is on social media.

One reason for choosing this question was to capture a sense of how much knowledge the parents have about their children’s online life. It also answered the question, if the social media made for children was used a lot among the respondents’ children.

When it comes to the awareness, if their children are on social media, the parents seem very much aware about this.

In the first age group consisting of 0-5 year-olds, 62,5% of the parents said that their children are not on social media. It could be argued that is not surprising, as the children still are toddlers and therefore not able to read and write. Therefore, the next age groups are more interesting for this research. The age group from 6-12 years old showed the following results regarding how many children the parents have in this age group and if they are aware of if they use social media.

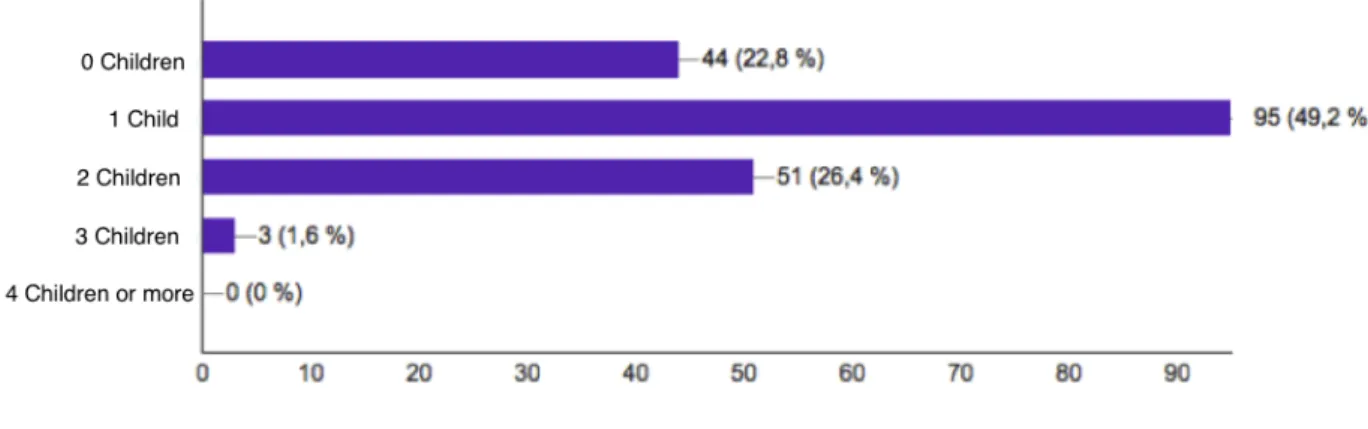

Figure 3: Parents who have children between 6-12 years old

Source: Appendix 3

In figure 3, it can be seen that the majority of the respondents have children in this age group (6-12 years old); 149 out 193 of the parents have children in this age group. Only 44 respondents do not have children in this age group.

Figure 4: Parents indicating if they are aware of their children using social media (Parents of the 6-12 years old)

Source: Appendix 3

Figure 4 shows that 112 of the parents from figure 3 know that their child uses social media. Only 1 parent stated that he/she does not know whether or not his/her child is a user of social media. From figure 3 and 4 it can be concluded that most of the parents are aware of their children using social media. The following age group consisting of 13-18 year-olds shows the following results.

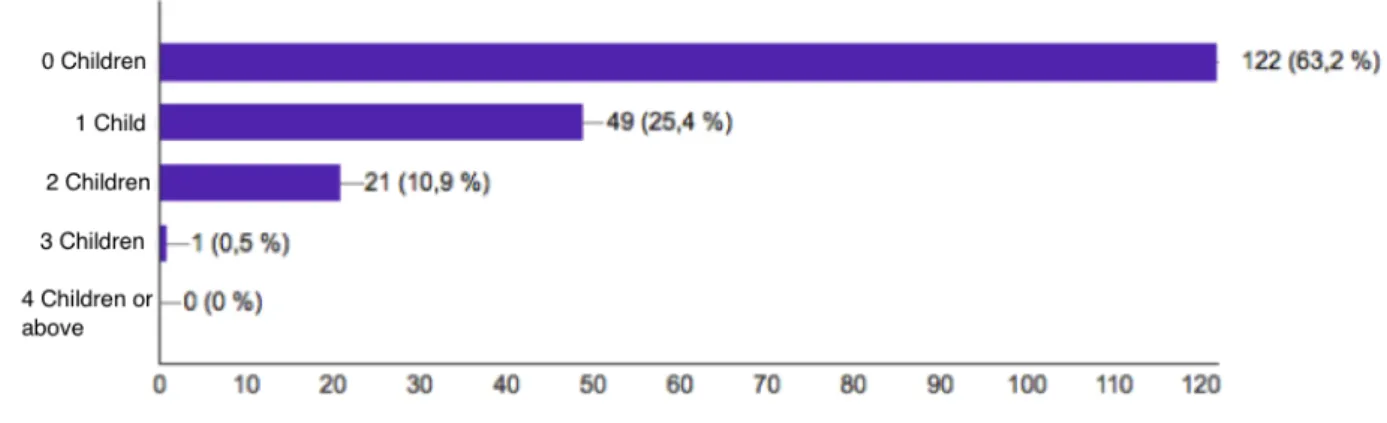

Source: Appendix 3

From figure 5 there are not many respondents, who have children in this age group (13-18 years old).

Figure 6: Parents indicating if they are aware of their children using social media (Parents of the 13-18 years old)

Source: Appendix 3

In this group of children from 13-18 years old only 71 of the respondents have children. However, in this age group 93,7% of the parent said yes to that their child/children has an account on a social media platform. As written in the background most social media platforms require the users to be at least 13 years old and therefore it could be argued that it is not unusual that children in this age group has social media accounts. Furthermore, it can be argued that for this age group it has become a norm to have social media accounts without permission or supervision from parents. In relation to this, the age group consisting of 6-12 years old is more interesting.

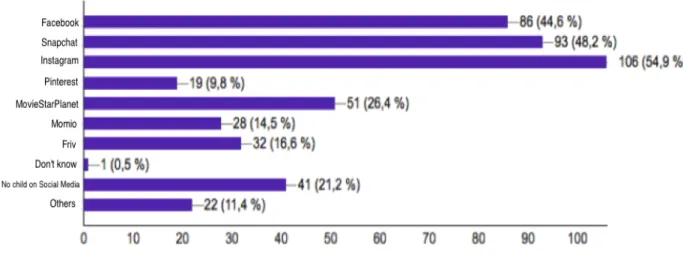

In the questionnaire the respondent was able to choose between several of the social media platforms, which they were aware of their child/children using.

Figure 7: Parents indicating which social media platforms they are aware that their children are users of (they could cross of several times, all age-groups included)

Source: Appendix 3

According to figure 7, the most used social media platforms according to the parents are Instagram (54,9%), Snapchat (48,2%) and then Facebook (44,6%). All these social media platforms require their users to be at least 13 years old, before being able to use them. Some of the social media platforms designed for children such as MovieStarPlanet and Momio are not that heavily used. This could be due to the fact that they are not interesting enough for the children, as most teenagers do not use these platforms. MovieStarPlanet is a mixture between a game and a social media platform, which could be why many teenagers do not use it, as it can be seem too childish and therefore more appeal to the children from 8 years old. Another indication as to why Instagram and Snapchat are most popular among children and teenagers is that parents do not really use these platforms yet. As mentioned in the context section Facebook is the most used social media platform among adults (check p. 5). However, the findings from the parents, who have children in the age group 6-12 years old showed different findings than in figure 7.

Figure 8: Parents indicating which social media they are aware of that their children are users of (they could cross of several times, parents with children from 6-12 years old)

Source: Appendix 7

Figure 8 indicates that most of the parents are aware of their children use of Instagram, Snapchat and Facebook. The findings in figure 8 clearly seem very similar to the results in figure 7. It could indicate that the children from 6-12 years old mostly use the social media platforms, where it is required to be 13 years old. However, there are also a high number of users of MovieStarPlanet, almost close to Facebook.

The comments in the questionnaire suggested that many parents had made their children users of these platforms, for example:

“In relation to my daughter at 10 years old, many consideration has been about her age. We thought she was too young, but her wish to become on Instagram was very big cause of her friends has it”

(Appendix 3: 13.30).

This seems to be a problem for some of the other parents as well. They feel pressured about letting their children become users on social media platforms, because of the child’s friends and some of parents feel that their children will be left out.

As a parent states:

” I think it’s too early, unfortunately.. but if you will follow the tendency among the classmates you have to be online...”(Appendix 3: 23.8)

Another parent states the problem with not being online on social media as not having a phone earlier (Appendix 3: 23.14) or as another parent states:

“We just started on this, when she turned 10 years old and got her first phone. We have been talking about when and where she can use it and keep an eye on it. We would have like to avoid that she started being on Momio and instead just wrote texts her friends, but a huge amount of her classmates have a community on Momio, so we chose to allow it…” (Appendix 3: 13.70).

Most of the parents seem to have an opinion about their children being online on social media regarding the age dilemma. It could be argued that many parents are afraid that their children will be left out of the community, if they are not present on social media. This could also be an effect of mediatization as media has entered a close relationship between the children and their play

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 Facebook Snapchat Instagram Pinterest MovieStarPlanet Momio Friv Don't know No child on social media

Others Others 8,05% No child on social media: 22,81% Don't know: 0,06% Friv: 20,80% Momio: 17,44% MovieStarPlanet: 31,54% Pinterest: 8,05% Instagram: 53,02% Snapchat: 42,95% Facebook: 35,57% %

(Livingstone, 2009(b): 8). This seems to the problem for the parent above as her child’s friends are playing together on Momio.

Another parent explain the difficulties:

” It has always been difficult to be a child and young. You have to say the right things, you have to be in the right clusters, do the right things. That is also the case now. There are rules in real life and behind the screen, and you have to learn that” (Appendix 3: 23.44).

This parent seems to accept the fact that social media has become an essential part of the way children are playing and interacting with each other.

However, many of the parents have doubts about their children joining social media, especially because of their young age. One parent has this concern:

” Children under 10 years old shouldn’t be using social media – They need to create real and close relations with their friends” (Appendix 3: 13.109).

This parent seems to be worried about that her child will no be able to have real-life interaction with people, if she gets on social media too early. However, there is also a parent, who utters an

advantage of them being on social media early. The parent states:

“Think the earlier they have been on something age appropriate example club penguin and similar, the better they become to navigate around on social media later on. If you as parent have been a part of it from the beginning” (Appendix 3: 23.51).

From the findings it could be argued that many parents have concerns about the young age and about their children using social media, but at the same time they do not want their child to be or feel left out. The media surrounds the children in modern family life and this seems to engage the parents in a constant battle, because the parents want the balance between the educational and social advantages as well as wanting to prevent the negative effect that some content or mediated contact might have on their children’s safety, behavior and attitudes (Livingstone & Helspher 2008: 581). Furthermore, the patterns among the respondents are that the parents are divided into two: those who let their children use social media and those, who want to wait as long as possible.

Even though it seems to be a dilemma for the parents, they seem to be very communicative about the use of social media. Therefore, the following section will look into this aspect.

5.2 Communication about social media

As this research is focused on how and if parents are communicating and engaged with their children about social media, one of the questions asked specifically about this. The results are shown in figure 9.

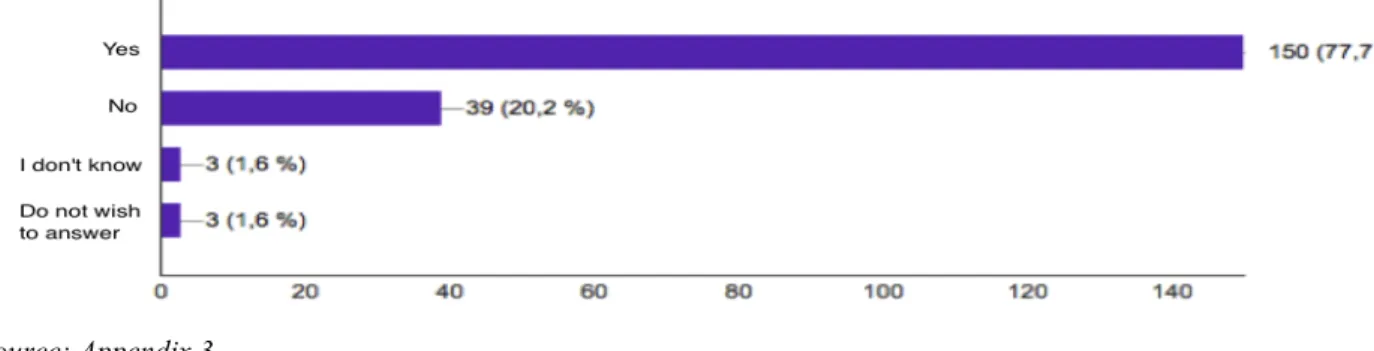

Source: Appendix 3

From figure 9 it is shown that most of the parents have talked to their child about how to behave on social media. In the questionnaire, 77,7% of the parents state that they have talked to their children about on how to behave on social media whereas 20,2% say they have not. This is very close to the findings from EU Kids Online, where 70% of the parents say they have talked to their children about social media (EU Kids Online, 2014) (this number is from all the participating countries). From this it can be argued that communication about social media seems to be something very important in many families. However, it could be argued that many of the respondents firstly communicate about risk with being online. The parents with children in the age group from 6-12 years showed the following findings.

Figure 10: Parents indicating if they have talked to their child/children about social media (Parents who have children in the age group 6-12 years old)

Source: Appendix 7

In figure 10 it shows that the majority of the parents have talked to their children in this age group. Figure 10 has very similar findings to figure 9 from the questionnaire and EU Kids Online. It could be assumed that many parents do talk to their children about social media. However, question 14 (appendix 3) asked what the parents had told their children both positive and negative things. Therefore, the following question asked the parents to elaborate on how they had talked with their children about behavior on social media. This following section will highlight the split between the

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 Yes

No

Do not wish to answer 0,67% (1)

25,5 % (31)

78,52% (117) %

different parental mediation, which is mentioned in the theory section. In this section there will also be included some of the findings from the EU Kids Online. This will provide a better understanding of how parents are engaged and communicating with their children about social media.

5.3 Communication strategies about social media

As discussed in theoretical framework, parental mediation includes three different kinds of strategy for the parent to communicate with their child/children: active mediation, restrictive mediation and co-using mediation. Figure 8 showed that the majority of the respondents have talked to their children about social media.

However, it is interesting that 20,2% say they have not talked with their children about behavior on social media. It could be assumed that those parents trust their children and believe they can handle it by themselves. Or as Sonia Livingstone states, parents would rather trust their children than check up on them (Livingstone, 2009: 221).

Parental fear seems to be a struggle in the family life. boyd and Hargittai (2013) argue, that parent fears often lead to parental concerns and the parents do everything to shield their children from risk. This leads the parents to create strategies, which employ more involvement in their children’s behavior, restrictions or trying to educate their children about risks (boyd & Hargittai, 2013: 246). Some parents express doubts about other parents, who do not communicate with their children about social media, and as one argues:

” Yes.. I am very worried about those parents who do not take their time to understand the different social media. And by then don’t teach their children what is right and what is wrong. And I am scared that exactly these children are going to hurt my children one day” (Appendix 3: 23.46).

This parent does not stand alone with this. Another parent had directly told in her/his child’s class that the parents need to communicate with their children about social media as her/his child had a bad experience on social media (Appendix 3: 18.8). Overall, it seems to be important for the parents that they know that the other parents also have talked with their children about social media and behavior. Many of the comments indicate that it is the parent’s responsibility to advise and

communicate with the children about social media. One of them is bullying and another is content sharing. These two concerns and fears are two things, which can affect the child, who becomes a victim. Therefore, it can be argued that some parents worry about this, if they do not feel other parents have talked about this.

Another problem could be that some parents do not have the necessary knowledge about the Internet or social media and therefore do not know how to talk with their children about it. One parent thinks it depends on the age of the parents:

” […] Many parents of the older generation do after my opinion do not have any idea how much is happening on the Internet – including how much their own children interact and perform” (Appendix 3: 23.30).

This parent might have good point, as mentioned in the context section it was found that the older the person was, the less likely the person was to appear on social media, (see figure 1, p. 5) This might cause some problems and unawareness from the parent and they are therefore not

capable to educate or help his/her children. This also something Schultz Hansen (2011) notes. In his research he argues that the older generation does not know the ‘rules’ online and therefore are skeptical. They have not grown up in the digital age and thus find it hard to accept that it has become a kind of ‘real’ life for the younger generation (Schultz Hansen, 2011:10). It could also be argued to have an effect on mediatization as the interplay between media and structure of the family life has changed with new media i.e. social media. Unawareness, might be a problem for some parents and therefore they do not talk to their children about use of social media as their insecurity will shine through and might be a failure for the parents, if they feel the child do have better knowledge about social media.

Even though the questionnaire did not focus on the parents’ skills in using the Internet, it is still interesting to see how many of them feel confident in guiding their children regarding social media. As Livingstone (2009) argues, children are highly skilled users of technology, because they have grown up with compared to their parents. This creates a gap between more-expert children and less-expert parents, which in turn creates some challenges for the parents as they are expected to guide their children (Livingstone, 2009:53).

Furthermore, Livingstone and Helspher argue, “for new media, the lack of technical expertise may hinder implementation of parental mediation at home” (Livingstone & Helspher 2008: 582). This could be one of the reasons that 20,2% of the respondents has not talked to their children. However, in the questionnaire it was only a few of the respondents, who indicated that they do not use social media; 180 out 193 stated that they use social media (Appendix 3: question 22). As figure 10

shows, it is 31 parents who have talked to their child about the use of social media and these parents could be interesting to get a better knowledge about in further research.

5.4 Parental Mediation: Active Mediation

Active mediation is interesting in relation to the respondents and to the findings from EU Kids Online. In the report from EU Kids Online 58% of the parents stay nearby, while their children are online (EU Kids Online, 2014). This number is based on all the participating countries.

In active mediation parents talk to the child/children about the medium while they are engaging with it. In the questionnaire it was not asked, if they were nearby, when their child/children was online. A reason for this could be that devices such tablets and smart-phones have a small screen, which can make it hard for a parent to fully interact and talk with the child, when they use the medium. Therefore, it can be hard to make the Internet a shared family activity compared to TV (Livingstone & Helspher 2008: 583).

However, one of the parents indicated that they felt better, if they were in front of the screen with their child:

”[…] But I had long conversations about being critical and quality-conscious in relation to what you see online. While we have been sitting with an iPad, a movie or a game” (Appendix 3: 16.121).

As mentioned above it seems to be that many parents do communicate with their children about social media. However, it seems difficult to actually know, if the parent engages with their

child/children, while they use the medium. It could be argued that other strategies are needed, when it comes to mediation of the Internet.

5.5 Parental mediation: Restrictive mediation

One of the strategies, which seems most widespread among the respondents from the questionnaire is restrictive mediation. This mediation focuses on restriction of any kind and consequences of content shared. This mediation does have been the subject of discussion regarding its effectiveness in previous research. Overall, it seems to be a strategy the parents use in hope for reducing

children’s online risk experiences (Livingstone & Helspher 2008: 584). Therefore, it was interesting to see how many of the respondents used this and how they described their restrictions for their child/children.

Question 12 addressed this and the parents wrote down if they had restrictions. The question was not leading towards to that the parents should describe their restrictions for their child/children, but it seemed to be something most of the parents had in mind, when asked about following.

Figure 11: Parents indicating if they have any positive or negative thoughts about their children being on social media (all respondents answers)

Source: Appendix 3

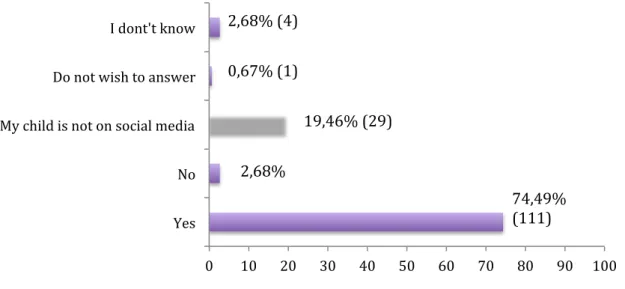

Figure 11 shows a tendency that many parents do think about that their children are present on social media. Parents that have children from 6-12 years old showed the following.

Figure 12: Parents with children from 6-12 years indicating, if they have any positive or negative thoughts about their children being on social media

Source: Appendix 7

In figure 12 it is possible to argue that parents, which have children in this age group also have thoughts about their children being on social media. 29 of the 149 respondents indicate that their child/children are not on social media. This is a very neutral answer and could imply the

considerations regarding children being on social media is not relevant for them, as their

child/children are not on social media, yet. Thus, these parents have chosen not to think or worry about it.

However, from this question it cannot be deduced if it is negative or positive thoughts. After this question the parents had the opportunity to explain their thoughts. The majority of the respondents have made restrictions about uploading content; that the children are only allowed to talk to friends, who they know from real life and not reveal private information such as name and address. In the

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 Yes

No My child is not on social media Do not wish to answer

I dont't know 2,68% (4) 0,67% (1)

19,46% (29) 2,68%

(4) 74,49%