P . BEVEL ANDER, M. H A gs t R ö M & s . R ö NN q V is t (ED s .) MALM ö UN iVER sit Y • M iM 2009 R E s E tt LED AND i N c LUDED ?

Resettled and included

?

the employment integration of resettled refugees in sweden

Editors: Pieter Bevelander,

Mirjam Hagström & sofia Rönnqvist

MALMö UNiVERsitY SE-205 06 Malmö Sweden tel: +46 46 665 70 00 www.mah.se EUROPEAN UNION Sweden has resettled refugees in partnership with the UNHCR since

1950 and it is one of the countries that receives the largest number of resettled refugees every year. Despite this fact, our knowledge of the labour market integration of this particular category of refugees has been limited. This volume is an outcome of the project Labour Market Integration of Resettled Refugees in Sweden. It includes a mapping of the labour market integration of resettled refugees in Sweden and it covers different facets of the reception and integration of this group such as the institutional framework, the integration of resettled refugees from Bosnia and Vietnam, resettlement policy and its consequences, the health of refugees in the reception process, and the effects of admission status on immigrants’ access to the labour market. In addition, this book contains a more general chapter on resettlement in Canada to provide some contrast to the Swedish case.

© Malmö University (MIM) and the authors Illustration: Mirella Hautala

Printed in Sweden by Holmbergs, Malmö 2009 ISBN 9978-91-7104-087-9 / Online publication www.bit.mah.se/MUEP

Malmö University

Malmö Institute for Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare (MIM) SE-205 06 Malmö

Sweden www.mah.se/mim

Resettled and included?

PieteR BevelandeR

MiRjaM HagstRöM

& sofia Rönnqvist

(eds.)

Malmö University, 2009

MIM

This publication is also available on www.mah.se/muep

contents

PREFACE ... 7 AboUT ThE AUThoRs ... 9 1. REsETTLED AND INCLUDED? ThE EMPLoyMENT

INTEgRATIoN oF REsETTLED REFUgEEs IN swEDEN ... 13 Pieter bevelander, Mirjam hagström and sofia Rönnqvist 2. AN INsTITUTIoNAL FRAMEwoRK oN REsETTLEMENT .. 29

Denise Thomsson

3. IN ThE PICTURE – REsETTLED REFUgEEs IN swEDEN ... 49 Pieter bevelander

4. VIEws FRoM wIThIN: bosNIAN REFUgEEs’ EXPERIENCE RELATED To ThEIR EMPLoyMENT IN swEDEN ... 81

Maja Povrzanović Frykman

5. sTRATEgIEs FRoM bELow: VIETNAMEsE REFUgEEs, EDUCATIoN, sECoNDARy MoVEs AND EThNIC

NETwoRKs ...129 sofia Rönnqvist

6. wINNERs AND LosERs? ThE oUTCoME oF

ThE DIsPERsAL PoLICy IN swEDEN ...159 Mirjam hagström

7. hEALTh AND INTEgRATIoN whEN RECEIVINg REsETTLED REFUgEEs FRoM sIERRA LEoNE AND LIbERIA ... 191 Eva wikström

8. ThE EMPLoyMENT ATTAChMENT oF REsETTLED REFUgEEs, REFUgEEs AND FAMILy REUNIoN

MIgRANTs IN swEDEN ... 227 Pieter bevelander and Ravi Pendakur

9. sECoND-CLAss IMMIgRANTs oR FIRsT CLAss

PRoTECTIoN? REsETTLINg REFUgEEs To CANADA ...247 Jennifer hyndman

CoNCEPTs ...267 REFERENCEs ...277

PReface

Like many other research projects, the one on resettled refugees in Sweden presented in this volume is a result of the effort of many people. We are grateful to all of you who have contributed in both large and small ways to complete this endeavour. In particular we are grateful for the financial support from the European Refugee Fund (ERF), the Axel och Margaret Ax:son Johnson Foundation, and the Malmö Institute for Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare (MIM).

If not for Henrik Emilsson who initiated the project in 2008, this volume would not exist; many thanks to him. In addition, a large measure of thanks to the authors who have contributed chapters to this volume: Jennifer Hyndman, Ravi Pendakur, Maja Povrzanović Frykman, Eva Wikström, and Denise Thomson.

Some results of the project were initially presented at the Metropolis conference in Copenhagen, September 2009. We would like to thank the participants of the workshop “Resettlement and integration: emerging issues and solutions for resettlement in Europe, Australia and Canada” for their valuable comments. Moreover, we offer sincere thanks for most valuable comments on earlier drafts and suggestions for revision of the chapters, to Benny Carlson, Jonas Frykman, Ivan Gušić, Mia Hadžić, Daniel Hiebert, Anna Lundberg, Dragan Nikolić, Tobias Schölin, Zoran Slavnić and Susanne Sundell Lecerof.

Moreover we would like to thank all of the informants in individual research projects, for sharing their insights and experiences with the contributors to this volume. Both the accounts of former resettled refugees as well as the views of public officers on municipal, county council, and the state level have contributed to a more complex understanding of the employment integration of resettled refugees in Sweden. Last but not least, we are very grateful to Natalie Crook for her careful copyediting and help in finalising this volume.

aBout tHe autHoRs

Pieter Bevelander is Associate Professor at Malmö Institute of Migration, Diversity and Welfare (MIM) and Senior Lecturer at the Department of IMER, Malmö University, Sweden. His main research field is international migration and different aspects of immigrant integration. His latest publications include the Economics of Citizenship (2008) (edited together with Don DeVoretz) and Social capital and voting participation of immigrants and minorities in Canada in Ethnic and Racial Studies (2009) (together with Ravi Pendakur). He has reviewed manuscripts for, and published articles in, several international journals. (pieter.bevelander@mah.se)

Mirjam Hagström has functioned as the Project Manager of the ERF-funded project Labour Market Integration of Resettled Refugees, which is the framework of this anthology. She has a master’s degree in IMER from Malmö University and has worked as a researcher in several projects between 2007 and 2009 at Malmö Institute of Migration, Diversity and Welfare (MIM), Malmö högskola. (mirjam.hagstrom@mah.se)

Jennifer Hyndman is Professor at the Centre for Refugee Studies,

York University, Toronto, Canada. Her research focuses on human displacement, humanitarian emergencies, and conflict. She is the author of Managing Displacement: The Politics of Humanitarianism (University of Minnesota Press, 2000), co-editor of Sites of Violence: Gender and Conflict Zones with Wenona Giles (University of Cali- fornia Press, 2004), and is currently writing a book on the inter- action of the 2004 tsunami and conflict in both Sri Lanka and Aceh, Indonesia. Her research probes the links among displace-ment, security, and globalization, and traces these processes from conflict zones and refugee camps to Canada where she analyzes refugee settlement policy and practice among recent newcomers. (jhyndman@yorku.ca)

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Ravi Pendakur is an Associate Professor in the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs, at the University of Ottawa. Prior to joining the University, he spent 18 years as a researcher in the Canadian federal government. His primary research domain continues to be that of diversity, with a goal toward assessing the socioeconomic characteristics of language, immigrant and ethnic groups in Canada and other settler societies. (pendakur@uottawa.ca)

Maja Povrzanović Frykman is Associate Professor in the field of

International Migration and Ethnic Relations (IMER), teaches at the Department of Global Political Studies (GPS), and is acting research coordinator at Malmö Institute for Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare (MIM) at Malmö University. Her research interests include experiences, places and belonging in war circumstances, as well as migrants’ identifications and transnational practices. She is editor of War, Exile Everyday Life (with R. Jambrešić Kirin; IEF, Zagreb 1996), Beyond Integration: Challenges of Belonging in Diaspora and Exile (Nordic Academic Press, Lund 2001), Transnational Spaces: Disciplinary Perspectives (Malmö University, Malmö 2004). (maja.frykman@mah.se)

Sofia Rönnqvist is a researcher at Malmö Institute for Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare (MIM), Malmö University. She has a PHD in Economic History (2008) and her main research interest is diversity in work-life organizations and the integration of immigrants in the labour market. (sofia.ronnqvist@mah.se)

Denise Thomsson is working at the Swedish Migration Board as an expert on resettlement. She is the project coordinator for the ERF-funded Swedish Resettlement Network, and participates in the ERF-project Swedish Quota Communication Strategy. Denise has a master’s degree in Social and Cultural Analysis from Linköping University and has previously worked at the Integration Board and as an independent consultant in qualitative studies and evaluations of migration and integration. (denise.thomsson@migrationsverket.se)

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Eva Wikström is Senior Lecturer and researcher at the department

of Social Work at Umeå University. Her research interests cover a wide range of topics in the field of international migration and ethnic relations (IMER), but are mostly directed towards studying the interplay of welfare state interventions and interethnic relations, exposure and integration processes. She has been involved in several evaluation studies of different welfare-state programmes aimed at receiving asylum seekers, or integrating resettled refugees. She has also taken part in a nation-wide evaluation of the governmental programme to prevent honour-related violence (HRV).

cHaPteR 1

Resettled and included?

tHe eMPloyMent integRation of

Resettled Refugees in sweden

Pieter Bevelander, Mirjam Hagström & Sofia Rönnqvist

introduction

Resettlement involves the selection and transfer of refugees from a State in which they have sought protection to a third State which has agreed to admit them – as refugees - with permanent residence status. The status provided should ensure protection against refoulement and provide a resettled refugee and his/her family or dependants with access to civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights similar to those enjoyed by nationals. It should also carry with it the opportunity to eventually become a naturalized citizen of the resettlement country. (UNHCR 2004)

The definition of resettlement described above sees resettlement as a process that starts with the identification of the applicants by the United Nations High Commissioner of Refugees (UNHCR), continues with their reception in the new country and goes on to include the long term integration of the refugee. It highlights the importance of integration and equality of rights of the resettled refugees in the new countries. The integration of resettled refugees is furthermore emphasised in the Agenda for Protection (2003). Both the UNHCR (2004) and the International Catholic Migration Commission (ICMC 2007) argue that seeing refugees solely as a

PIETER BEVELANDER, MIRJAM HAGSTRöM & SOFIA RöNNqVIST

burden for the international community, without also recognizing the contribution they make in their new societies, risks fuelling anti-immigrant sentiments. The UNHCR and the EU Commission argue, not only for an increased number of resettlement places worldwide, but also for an increased awareness in possible new host countries (UNHCR 2009b; The Commission of the European Communities COM (2007) 301).

There have only been a few European countries with resettlement programs over the past decades and there is a significant lack of knowledge in Europe in this field. This is partly due to the fact that it is difficult to discern the resettled group in national statistics in many of the EU countries (ICMC 2007). In most countries the resettled refugees and former asylum seekers go through the same introduction/integration programmes and there has been little attention paid to the effects of these programmes for specific groups. Moreover, comparative research between countries is complicated by the fact that labour markets differ within Europe.

In Sweden, as in the rest of Europe, few studies have been conducted on resettled refugees. However, the conditions for research are better in Sweden than in many other countries. In Swedish register-based statistics, it is possible to distinguish between refugees who were accepted as part of the yearly resettlement quota and those who sought asylum at the border. Moreover, Sweden has a long tradition of resettlement and has been accepting a comparably large number of resettled refugees per year, making it possible to conduct both quantitative and qualitative studies on integration of this group. In other words, the statistical data collection in Sweden facilitates in depth studies on the integration of resettled refugees in many fields.

This volume is an outcome of the project Labour Market Integration of Resettled Refugees in Sweden carried out by the Malmö Institute for Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare (MIM) at Malmö University and co-funded by the European Refugee

RESETTLED AND INCLUDED?

Fund (ERF) and the Axel and Margaret Ax:son Johnson Foundation. The main aim of the project is to increase the knowledge of labour market integration for resettled refugees in Sweden. This anthology, which will disseminate knowledge gained in the project, includes a thorough mapping of the labour market situation of resettled refugees and covers different aspects of the reception and integration of this group in Sweden. The book also provides a more general chapter on resettlement in Canada, an important complement to the Swedish context.

This increased knowledge on the integration of resettled refugees can be used to improve the reception of resettled refugees in Sweden. The long-term integration of refugees into the labour market is important both for the resettled refugee and for the host country. The knowledge from this project can thus be of importance for countries in the process of developing the new resettlement programmes called for by the UNHCR. The information provided here is timely, as the EU appears ready for more investment in resettlement as shown by the recent proposal of a joint EU Resettlement Programme by the European Commission.

the refugee situation in the world

– a call for more countries and more places

According to the UNHCR (2009a), forced population displacement has increased and is becoming more complex every year.1 In 2008, UNHCR estimated a total of approximately 42 million forcibly displaced persons in the world and about 25 million persons received some assistance from the UNHCR. Of the group that received assistance or protection, 10.5 million were refugees under the mandate of the UNHCR. Around 2.8 million of the UNHCR refugees originate from Afghanistan and 1.9 million from Iraq. These groups make up almost half of the refugees under the mandate of UNHCR. The 4.7 million other classified refugees were Palestinian refugees under the responsibility of the United Nations Relief and

1 If there is no other reference in this section on the global refugee situation, the data comes from the website of the UNHCR. See UNHCR (2009a) 2008 Global Trends: Refugees, Asylum-seekers,

Returnees, Internally Displaced and Stateless Persons or the UNCHR (2008) UNHCR Statistical Yearbook 2007. It is important to note here that the UNHCR (2009a) states that: “As some minor

adjustments may need to be made for the publication of the 2008 Statistical Year Book [..] they [the numbers] should be considered as provisional and may be subject to change” (UNHCR 2009a: 4).

PIETER BEVELANDER, MIRJAM HAGSTRöM & SOFIA RöNNqVIST

Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). Approximately 50 percent of all refugees are found in urban areas and one third in camps and 80 percent live in developing countries. The Asia and Pacific region host around one third of all refugees, North Africa and the Middle East host 22 percent, Africa 20 percent, Europe 15 percent and the Americas 8 percent. Often, refugees are temporarily protected in camps, are granted a temporary visa, or live as undocumented migrants in another country, while waiting for conditions in their home country to improve.

There are three principle means of achieving what the UNHCR calls a “durable solution” for refugees: repatriation, integration in the local population of the country of first asylum, and resettlement to a third country. Unfortunately, in some cases it takes a long time for a durable solution to be found. These cases, which are called “protracted refugee situations”, are defined by the UNHCR as situations “in which 25,000 or more refugees of the same nationality have been in exile for five years or more in a given asylum country” (UNHCR 2009a:7). About 5.7 million refugees find themselves in such protracted situations.

In 2008, about 604,000 refugees were voluntarily repatriated and it is the solution that has historically been employed most often. The number of persons who become integrated into the country of first asylum (the second solution) is difficult to quantify and will not be discussed here.

Resettlement, which is the durable solution addressed in this volume, has been a tool increasingly used over the years. Although it is a solution for only 1 percent of the refugees in the world, it is nevertheless important as a manifestation of global responsibility for world problems. Resettlement may also be of “strategic use”, i.e. when it serves to improve the situation for refugees who are not being resettled.

The traditional resettlement host countries are: Australia, Canada, Denmark, Finland, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and the United States. Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Iceland, Ireland and

RESETTLED AND INCLUDED?

the United Kingdom have established programs in recent years. Since 2007, France, Paraguay, Portugal, Romania, The Czech Republic and Uruguay have also established or re-established resettlement schemes. Japan plans a pilot project for 2010.

It is estimated that by 2010 the number of refugees in need of resettlement will be 747,000. However, the number of places offered by resettlement countries amounts to only about 79,000. The admirable work of the UNHCR in identifying and submitting refugees for resettlement has unfortunately now outstripped the number of places available.

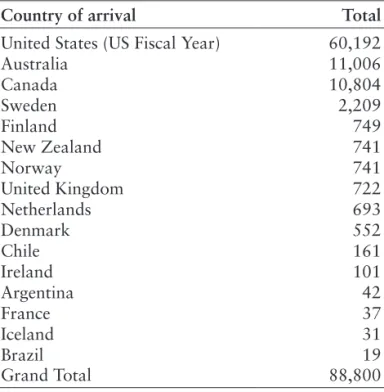

Table 1.1, Resettlement arrivals of refugees, 20082.

Country of arrival Total

United States (US Fiscal Year) 60,192

Australia 11,006 Canada 10,804 Sweden 2,209 Finland 749 New Zealand 741 Norway 741 United Kingdom 722 Netherlands 693 Denmark 552 Chile 161 Ireland 101 Argentina 42 France 37 Iceland 31 Brazil 19 Grand Total 88,800 Source: UNHCR

Chapter 2 in this volume provides a thorough introduction of the procedures and legal framework of resettlement. However, it is important to point out here the urgent need for resettlement places and resettlement programs, which is emphasized not only by the UNHCR, but also by other organisations such as the European

PIETER BEVELANDER, MIRJAM HAGSTRöM & SOFIA RöNNqVIST

Council on Refugees and Exiles (ECRE).3 Both the European Commission and the Swedish government, which holds the EU presidency in 2009, recognize that resettlement must be a priority for migration politics in the EU (The Commission of the European Communities COM(2007)301 and the Committee on Social Insur-ance 2006/07: SfU13).4

the joint eu Resettlement Programme

In the Policy Plan Asylum an Integrated Approach to Protection Across the EU, the Commission of the European Communities (COM(2008)360) states that, during 2009, a proposal will be developed regarding a Common EU Resettlement Scheme. Thus, on the 2nd of September 2009 the Commission of the European Communities (COM(2009)447) duly proposed the establishment of a Joint EU Resettlement Programme. The programme is established in solidarity with third countries that host a large number of refugees in need of resettlement. This proposal suggests that member states should start resettlement schemes on a voluntary basis. Identification and reception will be jointly carried out by member states. Financial assistance will be granted by the European Refugee Fund on a per capita basis for each resettled person received from priority groups. The programme is based on coordination and consultation among the countries that already have resettlement schemes with the objective of increasing the number of member states involved in resettlement. It is believed that a joint programme will make it easier and more cost-effective for member states to develop resettlement initiatives.

Resettlement in sweden

Earlier swedish studies

As already mentioned, there is a lack of research on the outcome of integration efforts on behalf of resettled refugees. This applies to Europe in general as well as Sweden but we will focus on the

3 See www.unhcr.org, www.ecre.org, the UNHCR and ECRE (2008) Joint European Advocacy

Statement on Resettlement and the UNHCR (2009b) recommendations for the Swedish EU

Presidency: Moving Ahead: Ten Years after Tampere UNHCR’s Recommendations to Sweden for its

European Union Presidency.

RESETTLED AND INCLUDED?

Swedish situation in this section.5 The literature dealing with

refugee integration includes the resettled group but most often it is not distinguishable in the general population statistics. Surveys usually do not include a category for resettled refugees. One reason for this lack might be that the integration programme is organised around individuals rather than groups of refugees. It does not take into account specific admission criteria. Another reason for the lack of resettled refugee specific data might be that their numbers are low compared to the larger group of individuals that apply at the border of a country (asylum seekers). Therefore research on this group might be considered less important. Furthermore, resettled refugees receive less attention because immigrant integration in Sweden is seen primarily as an issue of large urban centres where there are almost no resettled refugees.

The studies conducted in Sweden that have had resettlement in focus are mainly authorised by the Swedish Immigration Board (today the Migration Board) or the Swedish Integration Board (closed in 2007).The resettled refugees from Vietnam, a large group that arrived in the 80s, have been studied to some extent. One example is the report Vietnamflyktingarna – deras första år i Sverige published by the Swedish Immigration Board (The Immigration Board 1982).6 This study covers many dimensions of the integration process of the Vietnamese group including the labour market situation. It is a qualitative report based on interviews with refugees, municipal representatives and employers. The authors look at the situation shortly after arrival and make predictions about the future.

In 1997 the Immigration Board published another report Status Kvot: En utvärdering av kvotflyktingars mottagande och integration åren 1991-1996 which is an evaluation of the reception and integration of resettled refugees who had arrived in the early 1990s. This is the first comprehensive report on the reception of resettled refugees in Sweden. Earlier studies, such as

5 There is a lack of research on resettled refugees in Europe but many European countries do have some studies in the field. There are for example some studies in Norway, where resettled refugees are a category in the population statistics: Aalandslid (2008), Djuve (2002). There is one comprehensive study in the Netherlands: Guiaux et al. (2008). Moreover, in the UK, Evans and Murray (2009) look at the integration progress 18 months after arrival in the UK for resettled refugees who were accepted through the Gateway Protection Programme. These are just a few examples and more studies will be discussed in the different chapters of this book.

PIETER BEVELANDER, MIRJAM HAGSTRöM & SOFIA RöNNqVIST

the Vietnamese report, focused on ethnic groups and their success in Swedish society. One reason for the late attention to resettled refugees per se was that there was no distinction between classes of refugee before the reform of the refugee reception system in 1985 (Government Bill 1983/84:124). Before 1985, the reception and integration system was formed according to the resettled group, even though the numbers of asylum seekers had increased. All other immigrants were considered labour migrants.

The 1997 report covers many aspects of the resettlement process through quantitative and qualitative data. The section on integra-tion deals with settlement policy, Swedish educaintegra-tion, the labour market, and ethnic networks, and compares resettled refugees with other refugees. With regard to labour market integration, the report finds that the Public Employment Office intervenes later in the process for the resettled group compared to other refugees, and that the percentage of resettled refugees with a job is lower (at least during the first five years) compared to other refugees. The authors argue that this inequality can be explained by the different lengths of time spent in the country before a residence permit is granted. The asylum seekers had access to an orientation programme during their often lengthy waits while the resettled refugees were brought directly to a municipality without as much preparation. This is why the report suggests prolonging the intro-duction period for resettled refugees by one extra year.

In 2001 the Integration Board published the report Bounds of Security: The Reception of Resettled Refugees in Sweden, which is seen as a supplement to the above described “Status Kvot” report. The public officers dealing with reception in the municipalities had argued for the need of a new report. They claimed that the group of resettled refugees arriving between 1996 and 1998 had different needs compared to earlier resettled groups. Many of the refugees who arrived in the end of the 1990s had been living in camps for between 7 and 17 years, and it was pointed out that this could have consequences for their new life in Sweden. The report is based on the insights of the people working with reception and introductory programmes in the municipalities as well as on the reflections of the resettled refugees themselves. The authors argue that a long

RESETTLED AND INCLUDED?

introduction period, which was suggested in the “Status Kvot” report, contains the risk of becoming counterproductive. Instead they propose a new kind of introductory programme, calling for the inclusion of former refugees in the integration process, the enhancement of network-building among refugees, and a lowered skill expectation on the part of employers.

Finally, a publication by the MOST project (2008), funded by the European Refugee Fund, a co-operative endeavour among Sweden, Ireland, Finland and Spain, discusses various models designed to improve and hasten the integration process of resettled refugees. All contributions in this publication discuss the connection between pre-departure activities, the introduction in the host country and long-term integration. The Swedish contribution examines how resettled refugees experience the resettlement process in Sweden, using interviews with resettled refugees and municipal stakeholders (Thomsson 2008). The study shows that the dependent situation of resettled refugees in relation to the UNHCR before arriving might predispose the refugees to dependency in Sweden. It is further argued that introduction activities might serve to exclude the participants from mainstream society instead of including them. A stronger focus on empowering the refugees in the resettlement process in order for integration efforts to succeed is therefore advocated.

Immigration and employment integration

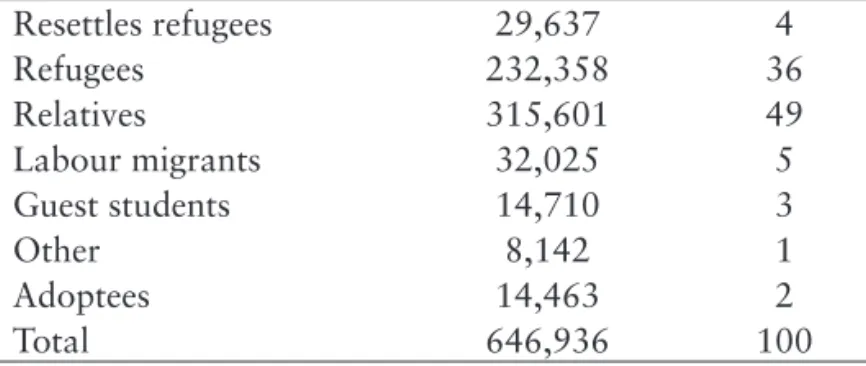

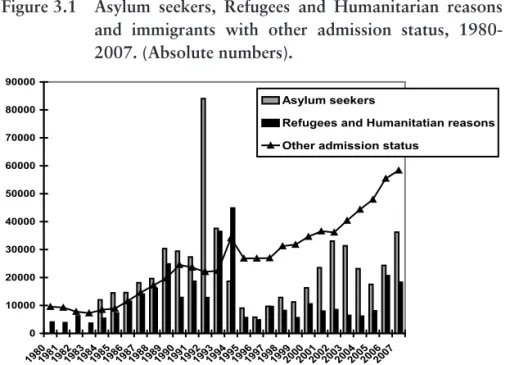

As mentioned earlier, resettled refugees only account for a small share of the overall immigration to Sweden in the last 5 to 6 decades. However, the resettlement programme in Sweden has a long history – it started in the 1950s and has from the beginning been a significant part of the Swedish immigration policy. Post-war immigration to Sweden took place in two waves. In the 1940s, 50s and 60s, labour immigration from Nordic and other European countries was a response to excess demand for labour due to the rapid industrial and economic growth of that time. The lower rate of economic growth and increased unemployment in the early 1970s diminished the demand for foreign labour. As a consequence, migration policy became harsher (Lundh and Ohlsson 1999). Labour immigration

PIETER BEVELANDER, MIRJAM HAGSTRöM & SOFIA RöNNqVIST

from non-Nordic countries ceased in the 1970s while the number of labour immigrants from other Nordic countries also decreased gradually. Since the early 1970s, asylum-seekers and tied-movers have dominated the migration inflow, coming primarily from Eastern Europe and non-European parts of the world. However, no matter what changes occurred over the years in larger migration patterns and in immigration policy, Sweden has maintained a yearly quota of resettled refugees since 1950.

This volume focuses on labour market integration, and more specifically on the employment integration of immigrants. Other types of labour market integration are touched upon, but are not the main focus of the book. Employment integration is a priority in Swedish strategy as mentioned above. It is important because through the workplace an individual encounters and understands society in a less fabricated way than through introduction or orientation programmes, and because self-sufficiency is a way to empowerment (ICMC 2007). We recognize that employment and self-sufficiency are not the only important aspects of integration but because of the complexity of the total concept of integration and the difficulty of measuring degrees of integration we must refine our approach. In this anthology we will map, analyse and discuss employment integration for one particular group of refugees, namely resettled refugees, from different perspectives and using different methods.

In Sweden, the institutional responsibility for the reception and integration of refugees in general, and those who are resettled in particular, lies with several levels of government. The Migration Board deals with the selection of individuals whereas they share the responsibility for the dispersal of refugees over the country with the County Administrative Boards. Finally local municipalities have the responsibility for delivering actual integration measures, such as adequate social services and training (including language training), directed to newcomers. According to the Integration Ministry, integration is not a matter of a single policy but rather it is trans-sectorial and must permeate the whole society (Communication 2008/09:24). Integration programmes should aim to counter exclusion in all fields of society, increase self-sufficiency, and

RESETTLED AND INCLUDED?

maximize access to the labour market. These institutional structures are important and establish the broad parameters of the integration of refugees in Sweden. We urge readers of this book to reflect on the nature of these structures as they read the following chapters.

summary of studies

There is a widespread need for more research on the situation of resettled refugees in the host countries. ICMC (2007), for example, calls for more academic research on the integration of resettled refugees, specifically in the area of employment and self-sufficiency. Many countries make no distinction between resettled refugees and other newcomers in the introductory period. ICMC means that it is necessary to disseminate information on the resettlement process so that differences between resettled refugees and other immigrants can be better understood (ICMC 2007). The information should include not only statistics but also good practices and lessons learned. When such information is readily available, it will help to expand the much-needed use of the resettlement tool across the EU and improve its effectiveness. The dynamics of placement policies and how they influence the integration process should also be studied.

The chapters in this anthology each provide one piece of the picture of labour market integration of resettled refugees in Sweden. They should all be read and understood separately but when included in the same framework they can truly provide the reader with a more comprehensive picture.

The second chapter of this anthology, by Denise Thomsson, is written within the framework of two ERF-funded projects at the Migration Board; the Swedish Resettlement Network and Swedish Quota Communication Strategy. The main purpose of this chapter is to spread knowledge about resettlement to a wider audience and to provide the reader with a background of resettlement in Sweden and in the world at large. The institutional framework of resettlement is discussed with detailed information on the different actors involved. The author also discusses the importance of long-term integration in the process of resettlement.

In chapter three Pieter Bevelander, with the use of register statistics from the database STATIV, maps the demographic,

edu-PIETER BEVELANDER, MIRJAM HAGSTRöM & SOFIA RöNNqVIST

cational and geographic variation among resettled refugees in Sweden in relation to other categories of admission. Moreover, he provides a descriptive analysis of the employment attachment of resettled refugees relative to other classifications for the year 2007. The focus is on migrants from the four largest resettled refugee groups, namely from Bosnia-Herzegovina, Iraq, Iran and Vietnam. The results provided in this chapter indicate that, in general, refugees who sought asylum at the border and subsequently obtained a residence permit have a somewhat higher employment rate compared to those in the family reunion category, who in turn have a higher employment rate than resettled refugees. However, deviation from this pattern is observed according to both country of birth and gender. Also employment rate patterns are affected by length of time in the country; resettled refugees can be depicted as “slow starters” who subsequently “catch up” to the employment levels of asylum claimants and family reunion migrants.

Chapter four, written by Maja Povrzanović Frykman, focuses on the personal experiences of employment, as perceived and narrated by some 40 people who came from Bosnia-Herzegovina in the early 1990s as resettled refugees and as asylum seekers. Resettled refugees cannot be seen here as a clearly discernable group as their employment histories overlap with those of asylum seekers. Their experiences concerning employment are compared in relation to their formal education, professional or vocational field, age, and the place of settlement in Sweden. While the narratives related here depict individual paths and bear witness to a vast diversity of experiences, they also illustrate trends. The issues highlighted in these interviews are very much in line with the knowledge of employment trends among Bosnian refugees discussed by other authors using other types of data.

Chapter five focuses on the resettled Vietnamese refugees who arrived in Sweden between 1979 and 1992. Their experience of labour market integration is described by Sofia Rönnqvist. Both this group and the Bosnian group discussed in chapter four have been in Sweden for a long time and their experiences of labour market integration are very important in order to understand the mechanisms of exclusion and inclusion as lived by the refugees

RESETTLED AND INCLUDED?

themselves. This chapter finds that, despite a comparably low education level, the group has a high employment rate compared to other refugee groups in Sweden. The author discusses the different strategies that this group has used to compensate for the disadvantages of a low level of education in the Swedish labour market. One strategy that was common for this group was secondary migration to places where there were a demand for low-skilled labour or where there were established ethnic networks through which individuals could get work.

Chapter six, contributed by Mirjam Hagström, concerns settle- ment policy and the settlement pattern of resettled refugees in relation to the labour market. The chapter shows that the settlement pattern of resettled refugees is different from that of former asylum seekers. The resettled refugees are more often placed in municipalities in the north and in depopulated munici-palities. It is also more common that resettled refugees are placed in municipalities with a higher than average unemployment rate. The arguments put forward on the advantages of this settlement policy are generally based on the assumptions that the dispersal of immigrants is desirable and that concentration is negative despite the fact that there is little theoretical support for these assump- tions. In fact it would appear that one reason why resettled refugees initially have a more difficult time finding work is because of the dispersal of these individuals to less attractive municipalities compared to other groups.

Eva Wikström discusses the health perspectives of the Swedish refugee reception process in chapter seven. The chapter is based on interviews with resettled refugees from Sierra Leone and Liberia who participated in a local introduction program with extra focus on health issues. According to the author, attention to health issues is still missing in much of the introduction work in Sweden. According to the participants interviewed, the program was not successful in promoting health and it did not contribute to faster employment integration for the group. She shows that circumstances creating stress for the refugees, such as unemployment and economic and social troubles, were downplayed by officials and re-cast in medical terms. Pre-migration experiences of war and trauma were seen as

PIETER BEVELANDER, MIRJAM HAGSTRöM & SOFIA RöNNqVIST

more significant impediments to integration. Such attitudes tend to reinforce the image of the refugee as sick and difficult to integrate instead of as a resourceful survivor. The chapter also shows that programmes designed to promote employment integration should focus not only on the refugees and their individual preconditions but also on the access to work and education available in the municipalities.

Pieter Bevelander and Ravi Pendakur explore in chapter eight, with the use of logistic regressions, the effect of admission status on the immigrants’ job opportunities and whether the influence varies across immigrant groups. They look at the cases of resettled refugees, former asylum seekers and family reunion migrants. As well they examine the effect of length of time spent in the country on employment results. Individual data on male and female immigrants and natives for the year 2007 are utilized. The results indicate that, with respect to country of birth, in general individuals from Bosnia-Herzegovina are the most likely to be employed. However, more detailed analysis, including admission status and time spent in the asylum seeking process, shows that resettled refugees and family reunion male migrants from Vietnam have the same chance to be employed as resettled refugees and family reunion migrants from Bosnia-Herzegovina. The variable “time in asylum seeking process” indicates a clear linear process in which the chances of obtaining employment improve with increasing years. The authors understanding of the results of the analysis is that both the selection process (self-selection as well as selection through policy mechanisms), and “time” for adjustment in a new country are important factors explaining the employment integration of immigrants.

In the last chapter, Jennifer Hyndman describes the history of resettlement in Canada to determine whether refugees are seen as “second-class” immigrants. Canada’s recent Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA), passed in 2002, made a distinction between immigration driven by largely economic objectives and refugee resettlement based on protection needs. Rather than diminishing protection for refugees, however, Canada expanded its humanitarian commitment to those most in need of resettlement. The chapter analyzes refugee resettlement to Canada, including the historical

RESETTLED AND INCLUDED?

and geopolitical context of its emergence throughout the twentieth century. She provides an overview of current refugee programming and outcomes, and discusses how immigration and refugee resett-lement streams are situated within the institutional context of government, where economic immigrants are part of an entitlement migration stream and refugees are part of a more discretionary “safety net” pathway to Canada. How this safety net has been extended to assist refugees from protracted situations is examined as evidence that refugees are not “second class” immigrants.

cHaPteR 2

an institutional fRaMewoRk on

ResettleMent

Denise Thomsson

introduction

It is a human right to be able to seek protection in another country, although in practice not everyone can access this right. Both practical obstacles (such as arrest, surveillance, threats of violence and assault) as well as a lack of means (money, contacts, or documents) prevent some people from leaving their country of origin when affected by a conflict. For others, protection still cannot be granted in the country to which they have fled. Some states have not signed the UN Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (“the Geneva Convention”), and do not have functional asylum systems. In other countries, asylum systems are failing under the pressure of major influxes of refugees from neighbouring countries. Many neighbours of war-torn countries are adversely affected and have limited potential to develop long-term sustainable solutions for the refugees who have made their way there.

Today, there are a large number of countries that are willing to share responsibility for the protection and security of refugees. Every year, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) helps to relocate thousands of the most vulnerable people to safer countries by means of “resettlement” from their first country of asylum. This process not only involves considering and granting residence permits but also travel to and reception in a new country. The country is subsequently responsible for the initiatives

DENISE THOMSSON

and support required to promote integration and also participation on equal terms as other inhabitants.

A Swedish resettlement programme (often referred to as the refugee quota) has been in place since 1950, which makes Sweden one of the more experienced countries in this field. Together with UNHCR and other countries, resettlement is presented as an option for the refugees in most need of protection. However, there are not enough places to meet global needs. In practice, protection can only be offered to a fraction of the refugees who require it. It is estimated that just over 200,000 people will need to be resettled during 2010, compared with 79,000 available places. Resettlement to States in Europe represents only about ten percent of the total demand (UNHCR 2009c).

Positive developments are taking place in an increasing number of countries, and discussions regarding improvements to the capacity for resettlement are being held at various levels: within and between States, among organisations and on a European and global level. At the same time, there is a risk that financial concerns together with growing xenophobia will limit the potential for functional reception and integration – two key aspects when forming long-term sustainable solutions for refugees. A lack of knowledge may also contribute to the problem. These issues highlight the importance of discussing, assessing and developing initiatives to support the integration of resettled refugees in both their new countries and their host communities. It should be possible to create better conditions, both for those who are being resettled and those who are not, by using the resettlement tool more strategically. Through increased support for the host countries and (new and existing) resettlement States, closer cooperation among stakeholders, and an improved level of knowledge on the part of both host communities and the refugees themselves, the potential of resettlement can be increased.

This chapter provides an overview of the institutional framework surrounding resettlement, its mission, central actors and key issues, as well as areas currently being developed in Sweden. The chapter may be said to provide the context and background for the analyses made in the following parts.

AN INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK ON RESETTLEMENT

what is “resettlement” and when is it used?

Resettlement (vidarebosättning in Swedish) involves the transfer of refugees from a country in which they have sought asylum to another country where they can be offered a safe and viable future. The process is coordinated by the UNHCR. This measure is one of three “durable solutions” employed by UNHCR when seeking protection for refugees, the others being return to the original country and settlement in the country of first asylum. Resettlement then represents a direct protection intervention to ensure the safety of persons who have little or no potential for local integration and are unable to return to the home country. At the same time, the option should guarantee long-term security and a viable future. On its website, UNHCR emphasises the importance of host countries working actively to promote the rights of refugees in the form of both legal and physical protection and opportunities to acquire citizenship in the longer term. Supporting integration between refugees and other inhabitants represents an important step in this work.

Besides the direct protection that resettlement can offer an individual or family, this measure can also be used strategically to benefit a larger target group. These benefits may accrue to other refugees as well as host communities or the international community in general (UNHCR 2004). Selecting a group of refugees may, for example, generate protection space for those who have not been resettled. Knowing that the international community is demonstrating solidarity and sharing the responsibility can create incentives for the better treatment of refugees who remain in a country of asylum. The strategic use of resettlement, together with other solutions such as aid and conflict management, may also contribute to a resolution of the problems that caused the original displacement.

Resettlement in the past and present

The concept of resettlement emerged during the interwar period and evolved when the UN and the International Refugee Organisation (IRO) were created during the late 1940s. The main aim was to help those refugees who, in the aftermath of the Second World War, were unable to return to their countries of origin during the

DENISE THOMSSON

Cold War period. During the 1940s, IRO resettled more than one million people to safety in new countries (UNHCR 2004). In 1950, IRO was replaced by UNHCR, whose principal mandate is to seek protection and durable solutions for refugees. For example, 200,000 Hungarian refugees who had fled to Yugoslavia during the Soviet invasion and almost 700,000 Vietnamese boat refugees on the Southeast Asian seas were resettled in the decades that followed. During the 1990s, thousands of refugees from, among other places, the Middle East, Yugoslavia, Kenya and Sudan were given the opportunity of protection in resettlement countries. Resettlement became a way in which states could demonstrate solidarity with those worst affected by wars and conflicts. Meanwhile, several countries developed annual programmes to assist UNHCR with places for refugees in need of protection.

Today, twenty States around the world have annual and established resettlement programmes.7 This is in addition to countries that assist the UNHCR on a more ad hoc basis.8 The largest groups that have been resettled in recent years have been Iraqis, Burmese and Bhutanese located in Thailand, Nepal, Syria, Jordan and Malaysia (UNHCR 2009e). The value and development of resettlement is being discussed in several arenas. The largest forum is the Annual Tripartite Consultations on Resettlement (ATCR) among States, the UNHCR and other organisations, held in Geneva each year. Refugee responses are also developed through various cooperative endeavours including bilateral exchanges of experience between countries, regional fora such as those held by the Nordic countries, and information sharing among non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The issue of collective responsibility for refugees and common initiatives and cooperation is highly topical. It has been highlighted both within the EU and at the UNHCR’s annual consultations. It is generally acknowledged that it is unreasonable for a few countries to be forced to bear a disproportionate amount of the responsibility for refugees, owing to their unfortunate proximity to war and conflict. A proposal for a common approach and a

7 Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Denmark, Finland, France, Great Britain, Iceland, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Paraguay, Portugal, Sweden, United States, Uruguay.

8 Here, Germany and Belgium may be mentioned as conducting their respective pilot programmes, and resettling 2,500 and 50 refugees respectively in 2009.

AN INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK ON RESETTLEMENT

programme concerning resettlement has recently been presented within the EU, as part of the Stockholm Programme’s common asylum system. Common approaches, guidelines, and initiatives, could result in a more equitable situation of shared responsibility as well as helping to resolve protracted refugee situations in various parts of the world. 9

Lately, reference has increasingly been made to the importance of using resettlement strategically and as part of a wider solution for protracted refugee situations.10 In its Resettlement Handbook, UNHCR states:

There is a growing recognition of the need for a more compre-hensive approach to refugee problems that involves helping different groups of refugees to find appropriate solutions to their plight, according to their individual circumstances, aspirations and the opportunities available. Resettlement is an essential element in a comprehensive strategy of refugee protection, and the strategic use of resettlement forms one part of such a comprehensive approach (UNHCR 2004:chapter 1, page 14).

In Sweden, the resettlement mandate has, over the past five years, been re-interpreted in a more flexible way so that, besides the basic selection and transportation of refugees to Sweden, it has also been possible to support special initiatives such as bringing seriously ill refugees to Sweden, temporarily, for treatment, or supporting a resettlement project in a neighbouring region.11

Yet despite these positive developments, the demand for resettle-ment is greater than the supply of places. At the present time, barely one percent of the world’s refugees are given the opportunity to resettle (UNHCR 2009e). As we have said, just over 200,000 people will need to be resettled in 2010 and barely 80,000 places are available (UNHCR 2009c). This means that more than half of those needing a place will have to be denied. It is therefore necessary to focus on those in greatest need. Making this judgment

9 Read more about the Stockholm programme and a joint EU resettlement programme on the Swedish EU Presidency website: www.se2009.eu.

10 See, for example, the Convention Plus initiative, taken up by the UNHCR in 2002.

11 For more information about the Colombia Project, see Government Decision, Ministry for Foreign Affairs – UD 2001/877/MAP.

DENISE THOMSSON

requires full knowledge of the conflict situations prevailing around the world. UNHCR is by many considered best equipped for this task; it has thousands of employees in over one hundred countries, including a large proportion of staff in the field, and monitors many of the world’s conflicts. It is, then, this organization that initiates a resettlement case. It is not possible for individuals, relatives, or other organisations to apply for resettlement. The final decisions about refugee selection are made at a national level according to each country’s laws and systems.

who becomes a resettled refugee?

It is difficult to say anything about the general background of resettled refugees. One common but misleading perception is that resettled refugees must have resided in refugee camps. According to UNHCR, however, this only applies to around one third of the world’s 10.5 million refugees (UNHCR 2009d). It is not location but the circumstances and lack of rights under which they are living (ibid) that determine the refugee designation. Resettlement is offered to persons who are considered to be in need of resettlement, regardless of whether they are located in a camp or not, are young or old, ill or healthy, highly educated or illiterate. In other words, resettled refugees are not found in refugee camps any more than is the case for other refugees, nor are they particularly ill or poor.

One feature that resettled refugees do have in common is that they have fled from their countries of origin and have not found any viable solution in the country in which they arrived. The reasons for flight differ. There may be a conflict on a national level (a war between countries or groups within a country) or there may be more personal issues (threat of violence or persecution of individuals) but in all cases the authorities in the country cannot offer the person protection. The following three examples illustrate the different backgrounds and experiences of resettled refugees. The examples are based on real cases, but names and details have been changed.

AN INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK ON RESETTLEMENT

Grace from the Congo

Grace Amenda grew up in a village in the Congo with her mother, father and five younger siblings. Several conflicts between different rebel groups in the country escalated in a short period of time and quarrels broke out increasingly close to where her family lived. After Grace’s father, together with several neighbours, reported malicious damage to several fields in the village, the family was subjected to threats. The siblings were assaulted and, ultimately, the parents were murdered. The siblings fled the village and made their way to a nearby community, from where they were helped to cross the border to Uganda. Once in the neighbouring country, the siblings tried to manage on their own, but were subjected to harassment from the local population. They had no entitlement to work and for this reason found it extremely difficult to make a living. After a few weeks, they made their way to the UNHCR, which concluded that they did not have any prospects of staying in Uganda, nor could they return home because of risks concerning their personal safety. UNHCR finally presented the resettlement case to Sweden.

The Yousif family from Iraq

Ahmad and Zarah Yousif and their two young sons are from Iraq. Ahmad’s parents moved there in the 1940s after they had been subjected to pressure in Israel because they were stateless Palestinians. Yousif and Zarah were both born and raised in Iraq, where they went to school and worked. Like many other Palestinians, they prospered under Saddam Hussein’s regime. However, the climate changed after Saddam was deposed and many Iraqi citizens started to persecute Palestinians, who they considered had received unfair advantages at the expense of the Iraqis. Zarah’s brother, who worked at the parliament, was kidnapped and the Yousif family received threatening letters. In the end, the family left

DENISE THOMSSON

the country and fled to Syria, where they could neither get work permits nor residence permits as they did not have any identification documents. Eventually they were bussed from Syria to a tent camp close to the Iraqi border together with hundreds of other families. They did not have any prospect of entering either Syria or Iraq. The UNHCR registered all of the families as refugees and issued them with tents as well as food and water rations. Although the camp was regarded as temporary, the family stayed there for three years before being selected for resettlement to Sweden.

Ibrahim from Eritrea

Ibrahim Al Mula was living with his parents in Eritrea when he received his call-up papers for compulsory military service. All men and women between the ages of 18 and 50 may be conscripted for compulsory military service at any time. This service often means that people are forced to stay in the military for a long time afterwards. In light of the unrest in Eritrea and an impending conflict, Ibrahim refused to report for military service. He left Eritrea by boat with several other young men and they made their way to Saudi Arabia. When they got to Saudi Arabia, all of them were arrested and put in prison as they had entered the country illegally. Ibrahim and the other men were imprisoned for five years without any prospect of a trial or their release. They had very limited contact with the outside world, despite pressure from human rights organisations and the UNHCR. One day, they were notified that they would be deported to Eritrea. Having shown that it was probable that their return would involve a threat to their personal safety, UNHCR ultimately succeeded in arranging for these men to be resettled to other countries, including Sweden.

AN INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK ON RESETTLEMENT

UNhCR assessments

To provide for resettlement, UNHCR conducts two kinds of assessments. First, overall assessments are made each year of the refugee situations around the world, which result in a number of proposals identifying resettlement initiatives for the coming year. The global review targets particular groups and locations for resettlement consideration. The judgements made by UNHCR are based on the refugees’ need of protection and may also take into account how protracted the refugee situations are as well as the extent to which the needs of the target groups fit the criteria applied by the respective resettlement countries. UNHCR has the major task of coordinating the initiatives conducted by the various States to ensure that logistics and resources allocations function properly and that not all countries make selections from the same place or at the same time. Both security details and coordination issues influence the roles the various receiving countries play.

The second assessment conducted by UNHCR is one based on the needs of the individual refugee. In order to determine whether a person is in need of resettlement, UNHCR must make a decision about the person’s refugee status. During an interview, the individual explains his or her history, reason for fleeing, prevailing personal circumstances, family situation, health status, etc. This material is compiled in a Refugee Registration Form (RRF). If UNHCR considers that resettlement would be the best solution, this document is used when presenting the case to a resettlement country. Together with supporting documentation about the refugee’s situation, UNHCR presents its assessment of the nature of the case and the person’s need of protection.

The categories used by UNHCR to assess whether resettlement is appropriate include: Legal and Physical Protection Needs, Survivors of Violence and Torture, Medical Needs, Women-At-Risk, Children and Adolescents and Older Refugees with Special Needs, and Refugees without Local Integration Prospects. UNHCR can also use resettlement to reunite families that have been split up (Family Reunification). In this last case Sweden would consider the individual under the ordinary rules for family reunification, and not within the resettlement programme (UNHCR 2004).

DENISE THOMSSON

swedish examination

When a person is considered to be in need of resettlement, UNHCR presents the case to a country for further examination. In Sweden, this examination is conducted under the Swedish Aliens Act (Law 2005:716). According to Swedish law, a person must be considered to be either a refugee or a person otherwise in need of protection in order to be selected as a resettled refugee. The definition of who is to be classed as a “refugee” largely corresponds to the UN Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (“the Geneva Convention” from 1951), which Sweden signed in 1954. The Act states that a person is to be regarded as a refugee if he or she is outside his or her country of origin because he or she has a well-founded fear of persecution on the grounds of race, nationality, religious or political belief or on grounds of gender, sexual orientation or other membership of a particular social group. This person is also unable, or unwilling because of his or her fear, to avail himself or herself of the protection of that country (Law 2005:716 4:1). People outside their country of origin for reasons other than circumstances that constitute grounds for refugee status are classed as ‘persons otherwise in need of protection’. They may, for instance, have a well-founded fear of the death penalty or torture, need protection because of external or internal armed conflict, or be unable to return to their country of origin because of an environmental disaster (Law 2005:716 4:2).12

As the examination must be conducted under Swedish law and practice, assessment as a ‘refugee’ by the UNHCR is not enough for a person to be automatically classed as a ‘refugee’ in Sweden. International conventions, such as the Geneva Convention, are subordinate to Swedish law, and the asylum procedure must comply with the legal practice of superior instances in Sweden. This means that there may be differences in how a case is assessed by Sweden and by the UNHCR; they may have different views on the situation in a refugee’s country of origin. Sometimes, UNHCR may consider that a person should be given refugee status because he or she belongs to a certain social group that is vulnerable in the country of origin. At the same time, the person must be able

AN INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK ON RESETTLEMENT

to demonstrate that a direct threat exists on an individual level in order to be deemed to be in need of protection and thereby be issued a residence permit in Sweden.

swedish resettlement work

Resettlement has been part of Swedish refugee policy since 1950. It is a supplement to the asylum system and is unaffected by the number of people who apply for asylum in Sweden each year. The Swedish Migration Board has been assigned by the Government to select and transfer refugees to Sweden within the framework of an annual refugee quota. The Government determines the size of the refugee quota; that is, how many refugees are to be resettled in Sweden each year. In 2009, 1,900 resettlement places were available. The Swedish Migration Board is then allocated funds by the Riksdag (Swedish Parliament), corresponding to the selection, transfer and reception of 1,900 individuals.

The Swedish Migration Board chooses the target groups and destinations for selection missions in consultation with the Government Offices and on the basis of the proposals made by the UNHCR. In-country selections are usually made in four or five countries, but further target groups are also considered from different places around the world. The refugee quota also includes a number of places for emergency transfers, which enable people to be selected and to travel to Sweden within the course of a few days. In 2009, 350 of the 1,900 resettled refugees could transfer to Sweden with emergency priority. These cases involve people who have been subjected to direct threats of deportation or execution, or who have serious and acute medical problems in addition to their protection need.

selection methods

Selections within the Swedish resettlement programme take place either through selection missions or selection on dossier basis. Selection missions with Swedish officers are sent out to the place where a group of refugees are located in order to conduct investigations and personal interviews with the persons chosen and presented by UNHCR. A decision on a residence permit is

DENISE THOMSSON

made directly by the mission. In recent years, examinations by selection missions have been made in areas such as the Middle East (Palestinian and Iraqi refugees), Iran (Afghan refugees), Thailand (Burmese refugees), and also in African countries such as Sudan (Eritrean refugees) and the Congo (refugees from the Congo (DRC) and Rwanda). In-country selections usually correspond to around 40-50 percent of the total refugee quota.

The alternative to selection missions is to conduct a direct exami-nation of the documentation (dossiers/files) that UNHCR presents to Sweden. In this case, the Swedish Migration Board makes the decision at an Asylum Examination Unit. Many countries only use selections by “in-country selection missions” and limit dossier selections to emergency and medical cases. There are several reasons why a State might choose to conduct an in-country selection; for example, it means that supplementary questions can be presented at a personal meeting and in that way there is a guarantee that the documentation base for the decision and settlement is sufficiently clear. This is particularly important when it comes to new destinations and target groups, or where previous experience justifies a personal examination procedure. Sweden is characterised by the large number of dossier selections it conducts, which sometimes constitute more than 50 percent of the total refugee quota. One important advantage of dossier selections is that the process can be made more efficient, both for UNHCR and the resettlement country.

On average, a resettlement case takes between two and four months from presentation to transfer to Sweden, although there is of course a significant variation between individual cases. In particular, the procedure for obtaining a permit for a refugee to leave his or her host country can take quite a long time. A residence permit certificate is issued by a Swedish mission or embassy and is endorsed in the travel documents that the refugees either already hold or have obtained at the time of their journey; it is most common to have a provisional alien’s passport that applies for entry to Sweden.

Use of integration criteria when selecting resettled refugees

The issue of the integration of resettled refugees and their potential for success in their new country is currently being discussed on both