J

Ö N K Ö P I N GI

N T E R N A T I O N A LB

U S I N E S SS

C H O O L JÖNKÖPING UNIVERSITY.

Relationship Marketing

in the online social network context: a study on student attitudes

Bachelor Thesis within Marketing Management Author: Jakob Grunditz

Emil Liljedahl Andreas Nyström Tutor: Olga Sasinovskaya Jönköping December 2009

i

Bachelor Thesis within Business Administration

Title: Relationship Marketing in the online social network context: a

study on student attitudes

Authors: Grunditz, Jakob; Liljedahl, Emil; Nyström, Andreas

Supervisor: Sasinovskaya, Olga

Date: Jönköping, December 2009

Keywords: Relationship Marketing, Internet Marketing, Facebook, Online

Social Networks, Mutual Value Offerings

Abstract

Background: Relationship marketing represents a trend in marketing to focus on

mutual value creation and consumer retention by strengthening the connection between an organization and its customers. With the growing popularity of online social networks such as Facebook and Twitter as communication platforms, the networks have gained attention as tools that organizations can use to address cur-rent and potential consumers. To utilitize these networks, it is cru-cial for organizations to understand how consumers use the net-works, what attracts them towards communicating with organiza-tions on online social networks and what drives them to maintain these relationships in the long run.

Purpose: This study examines the willingness of students, the dominant user

base of online social networks, towards the initiation of relation-ships with organizations on the networks Facebook and Twitter, and the drivers behind the relationship.

Method: The study was performed through a mixed method approach

consisting of a quantitative survey study and a qualitative focus group discussion conducted at Jönköping University. The survey addressed the topics of usage patterns and adopter motivations, while the focus group attempted to explain and motivate the data gathered during the survey study. Both studies targeted Swedish and international students.

Conclusion: The students tended to be long-term users of the networks, and

were positive towards communicating with organizations through the networks. However, the majority of respondents had not adopted relationship marketing through online social networks at this point in time. The respondents favored access to information and communication channels with peers as value offerings that would attract them to form relationships with organizations. Ulti-mately, relationship marketing on online social networks is com-pletely dependent on the consumer’s consent and wishes, and marketers must focus entirely on satisfying the concerns and re-quirements of its targeted users.

ii

Kandidatuppsats i Företagsekonomi

Titel: Relationsmarknadsföring på sociala nätverk online: en studie om

studentattityder

Författare: Grunditz, Jakob; Liljedalh, Emil; Nyström, Andreas

Handledare: Sasinovskaya, Olga

Datum: Jönköping, December 2009

Nyckelord: Relationsmarknadsföring, internetbaserad marknadsföring,

Facebook, social nätverk online, ömsesidigt värdeskapande

Sammanfattning

Bakgrund: Relationsmarknadsföring representerar en trend inom

marknadsfö-ring mot att fokusera på ömsesidigt värdeskapande mellan organi-sationer och deras kunder. De internetbaserade nätverken för soci-al kommunikation med Facebook och Twitter i spetsen har sett en enorm tillväxt under senare år och uppmärksammas alltmer som platformar för marknadsföringskommunikation. För att kunna ut-nyttja dessa nätverk effektivt måste organisationer utveckla en för-ståelse för hur dess kunder använder nätverken, vad som attraherar dem till att utföra en större del av sin kommunikation mot företag över dem och vad som driver kunderna till att skapa långlivade re-lationer med företagen över nätverken.

Syfte: Denna studie undersöker till vilken grad studenter, den

domine-rande användargruppen på de social nätverkerken på Internet, är villiage att kommunicera med företag over dem. Den undersöker även vad som attraherar studenter till att skapa och uppehålla rela-tioner med företag genom nätverken.

Metod: Studien genomföres som en multimetodisk undersökning där en

kvantitativ enkätundersökning och en kvalitativ fokusgruppstudie ingick. Enkätundersökningen behandlade primärt användarmöns-ter och motivationen bakom skapandet av relationer med företag online, medan fokusgruppen behandlade drivkrafter bakom uppe-hållandet av långlivade relationer. Båda studierna genomfördes på Svenska och Internationalla studenter.

Slutsats: Studenterna var huvudsakligen erfarna användare av de digital

nät-verken, och var positive till att kommunicera med företag over dem. Majoriteten av studenterna hade dock inte format relationer med företag over dem vid undersökningens tidpunkt, men de an-såg att tillgång till information och kommunikation med liksinnade var en stor del av värdet bakom sådana relationer. Relationsmark-nadsföring over internet står och faller med konsumentens sam-tycke, och marknadsförare som vill använda de digitala nätverken som verktyg måste respektera kundens rätt till integritet och foku-sera på att erbjuda dessa största möjliga värde.

iii

Table of Contents

1

Introduction...1

1.1 Background ... 2 1.2 Problem ... 3 1.3 Purpose ... 4 1.4 Research Questions... 5 1.5 Definitions... 5 1.6 Delimitations... 62

Theoretical Framework ...7

2.1 Usage Patterns... 7 2.1.1 Social Networks... 7 2.1.2 Relationship Marketing... 8 2.1.3 Relationships Online ... 9 2.1.4 Network Diffusion ... 10 2.2 Adopter Motivation ... 11 2.2.1 Adoption Drivers... 112.2.2 Viral Relationship Marketing... 13

2.3 Relationship Continuance Drivers ... 15

2.3.1 Social Media Integration... 15

2.3.2 Message Control ... 16

3

Methodology ...17

3.1 Survey ... 17 3.1.1 Survey Design ... 18 3.1.2 Sample Selection ... 19 3.1.3 Data Quality... 20 3.1.4 Pilot Study ... 20 3.1.5 Data Analysis ... 21 3.2 Focus Group... 22 3.2.1 Administration... 22 3.2.2 Sample Selection ... 23 3.2.3 Data Quality... 23 3.2.4 Data Analysis ... 234

Empirical Findings ...24

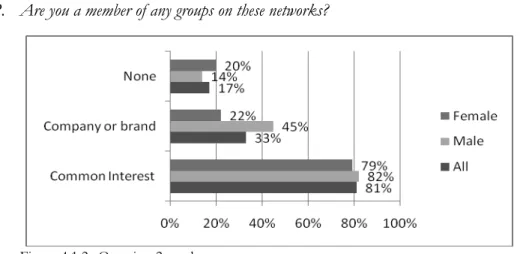

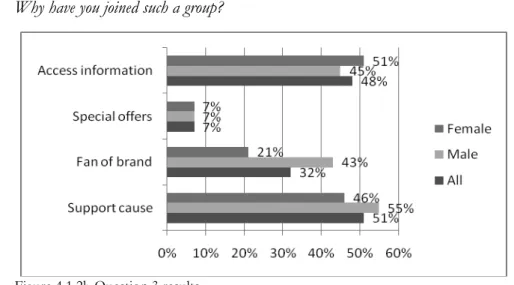

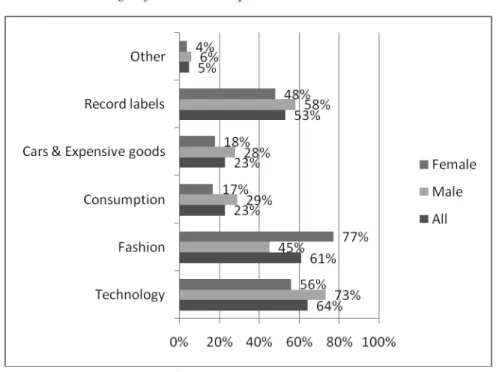

4.1 Survey Results ... 24 4.1.1 Sample Characteristics ... 24 4.1.2 Network Behavior ... 25 4.1.3 Network Usage... 284.1.4 Attitudes towards commercial participation ... 29

4.1.5 Survey Subsets ... 32

4.2 Focus Group Results... 33

5

Analysis...36

5.1 Usage Patterns... 36

5.2 Adopter Motivation ... 37

iv

6

Conclusion ...41

7

Discussion and Further Research ...43

References ...44

Appendix 1 – Survey Template ...48

1

1 Introduction

This section aims to provide an introduction to the concept of relationship marketing and the context of On-line Social Networks. It will also introduce the research purpose of this study and provide historical back-ground to online social networking.

Relationship marketing has been an emerging trend in marketing over the last two decades (Morgan & Hunt, 1994). Christian Grönroos (1992) defined relationship marketing as a process “to establish, maintain, and enhance relationships with customers and other part-ners, at a profit, so that the objectives of the parties involved are met. This is achieved by a mutual exchange and fulfillment of promises”.

As opposed to the traditional view of marketing, as best illustrated by the Marketing Mix model, relationship marketing does not subscribe to the notion that marketing communica-tion occurs in one direccommunica-tion, with one active and one passive participant (Morgan & Hunt, 1994). Instead, relationship marketing attempts to form a two-way connection between the buyer and seller that is based on trust and mutual interest. Rather than just attract custom-ers, it allows an organization to retain customers and enhance consumer loyalty (Grönroos, 1994).

Social networking is a relatively new phenomenon in the online world, but it is quickly gaining mainstream approval as more and more people sign up for these services and per-form a major part of their social interactions online through these networks. A service niche that was once limited to small audiences of early adopters now serves hundreds of millions of users on a regular basis (Boid & Ellison, 2007).

As with other digital services, many companies have a presence in the form of traditional advertising. In the digital context, this traditionally consists of simple graphical adverts such as banners, that attempts to generate user interest towards visiting the sponsoring organiza-tions’ website. While cost-efficient, this form of marketing works in much the same way as any other form of direct advertising and is widely regarded by users as objects of irritation or simply as irrelevant information (Pagendarm & Schaumburg, 2001).

The services that dominate the online social networking sphere offer users the opportunity to form and join various types of groups or sub-networks. These groups allow users that share a common interest to discuss and share information pertaining to their subject of in-terest. While the networks can be formed around a myriad of topics or interests, networks can also be formed around companies and brands. These sub-networks, created with the sole intent of maintaining customer relationships and broadening brand awareness, have become a common phenomenon on the major social networking services in recent years (Boyd & Ellison, 2007).

Rather than encountering this type of marketing involuntarily and regarding it as an obsta-cle, every user that subscribes to these groups has actively chosen to associate with that particular organization for some purpose. Clearly, marketing managers have a very strong incentive to attempt to seize this genuine consumer interest.

This study looks at relationship marketing in the context of the online social networks Facebook and Twitter. It is conducted in the format of a bachelor thesis and explores con-sumer attitudes of university students at the current point in time.

2

1.1 Background

The online social networks that are the context of this study have several common charac-teristics. Boyd & Ellison (2007) defined online social networks as internet-based services that allow the user to:

• Publish information in the form of a profile.

• Form and define connections with other users and groups.

• Use this list of connection to access information from other users, as well as their lists of connections.

Online social networks are a relatively modern concept, but they have existed in various forms since 1997 when the SixDegrees website was launched (Gross & Acquisti, 2005). This service shared some similarities with modern networks in that it allowed the creation of profiles and listing of friends, but it failed to generate the attention the networks of to-day have received. These features had existed before SixDegrees, but it was the first online services to integrate them in the format most online networks have today (Boyd & Ellison, 2007).

SixDegrees ceased to operate in the year 2000, and several sites opened and closed in the period that followed. The first of these to truly grab worldwide interest was MySpace, which opened in 2003 and primarily attracted a young audience (Boyd & Ellison, 2007). In 2004 it received competition from Facebook, a service based in the United States and di-rected at college students, a slightly older target group than that addressed by MySpace (Joinson, 2008).

The user profiles that can be created on networks such as Facebook allow the user to pub-lish information about their person, including any range of attributes from gender to politi-cal affiliation (Gross & Acquisti, 2005). They also allow the sharing of images and other forms of media, as well as the ability to join any number of discussion groups and works. Users also specify which other users they have connections to, which many net-works simply refer to as “Friends”, regardless of the nature of that particular connection. Users then maintain a list of these friends, and often automatically subscribe to information about their status updates (Joinson, 2008).

Facebook was initially kept closed to users outside of American universities, and required an e-mail address from one of these institutions to join (Joinson, 2008). These closed net-works on Facebook still exist and operate in much the same fashion, but the overall service was later made available to the public. Today, the online social networks market is domi-nated by a few large actors (Boyd & Ellison, 2007).

The norm in social networks today is that the service is publicly available, but access to cer-tain networks and adding new connections require various forms of permission (Boyd & Ellison, 2007). Thus, access to status information from friends is based on consensus of formation sharing. Similarly, any organization wishing to use these networks to contact in-dividuals that are connected to them must seek permission, often by convincing the user to actively sign up to some simple form of subscription list (Joinson, 2008).

Once subscribed, users can either choose to passively take part of information that is pro-vided by the group host, which within commercial groups often comes in the form of cur-rent offers, or to take part in discussions and attempt to recruit additional users for the usergroup. As in any other context, users can also find themselves disappointed by what

3

the group had to offer and decide to end communication by opting out, setting the stage for negative word of mouth messages about the organization in question (Richins, 1983). Word of mouth can also be used by marketers to attract customers to form relationships with organizations online.

One of the most successful ways of generating word of mouth is the concept of viral mar-keting and it has seen increased attention with the rise of the Internet as a dominant tech-nology in marketing (Phelps, Lewis, Mobilio, Perry & Raman, 2004). Based on the idea that recipients of a message can be influenced to pass the message along, it allows successful marketing campaigns to turn into self-sustaining reactions that reaches new audiences (Leskovec, Adamic & Huberman, 2007).

This approach can be utilized to find and persuade new consumers to form a relationship with the company (Helm, 2000), and it is one of the most crucial aspects of successfully gaining and maintaining an audience in the online social network context. Successful mar-keters must attempt to understand what motivates users to respond positively to these of-fers of forming relationships with organizations, and to identify what drives users towards continuing to maintain the relationships over an extended period of time.

1.2 Problem

Marketing on online social networks presents an opportunity for companies to reach out to individuals who are genuinely interested in their products and services, but it is contingent on to which degree consumers will respond positively to their presence (Ravald & Grön-roos, 1996).

Sheth & Parvatiyar (1995) defined relationship marketing as a value creation process where the consumer form an attachment to the product or brand by maintaining an interactive re-lationship with it. Naturally, the consumers’ perception of value, whether it stems from a perceived reduction in purchase risk or greater utility from products from the vendor in question, is critical for the process to be successful for both parties (Sirdeshmukh, Singh & Sabol, 2002).

Morgan & Hunt (1994) proposed that commitment from both sides towards the relation-ship is central to its success, further implying that attention should be focused on the party that does not have the dominant commercial interest in maintaining the relationship – in this case the consumer. A consumer that does not perceive any form of value in commit-ting to the relationship is unlikely to maintain it, and the relationship will fail to reach its full potential (Tax, Brown & Chandrashekaran, 1998).

Marketing, like all other disciplines affected by innovation, is in a constant state of change (Lovelock & Gummesson, 2004). The diffusion of relationship marketing in a new context will lag behind the diffusion of the underlying technology, and consumer acceptance of a commercial presence in a given setting is not necessarily diffused at the same rate as the technology itself. Therefore, the successful marketer must identify at which point in time a certain subset of the overall user category can be targeted for relationship marketing ef-forts.

Social networks are still in the early stages of becoming a mainstream communication tool but have recently gathered enough attention from a marketing perspective to warrant addi-tional research. Rashtchy, Kessler, Bieber, Shindler, & Tzeng (2007) found that the Internet is the number one source of media at work and the number two source of media at home,

4

they along with Vollmer & Precourt (2008) conclude that consumers are now more willing than ever to turn away from the traditional sources of advertising to gain more control over their media consumption. Consumers are also more willing to make information searches and purchasing decisions on social networks than ever before (Vollmer & Precourt, 2008). Full time students currently dominate social networks in terms of users (Joinson, 2008). Students have low buying power, but research conducted on online networks is likely to be applicable to the same individuals as they age and gain employment. Relationship market-ing aims to build long term interaction and it is therefore important for companies to form relationships as early as possible. Foux (2006) concludes his studies on consumer generated media with stating that social media is considered more trustworthy than communication transmitted through the traditional channels of the promotion mix. It is therefore impor-tant to consider the consumers opinions on marketing on social networks.

While relationship marketing and online social networks as individual topics have seen a great deal of research in recent years, there has been limited discussion on how relationship marketing can be utilized within the online social network context. Morgan & Hunt (1994) argue that while many of the dimensions involved in a successful relationship marketing strategy will be similar across the spectrum, there are also many factors that are highly con-textual in nature. Fournier, Dobscha & Mick (1998) note that even when it is generally un-derstood that a company must generate trust and commitment to succeed in relationship marketing, many companies fail to understand just how this is accomplished in their par-ticular context.

The contextual problem is two-fold in nature – As the context in which a consumer-to-business relationship is offered changes, so will the expectations and objectives of partici-pants. In addition to these differences, an organization attempting to capitalize on relation-ship marketing online must identify the potential audience. Simply identifying the users of these networks is unlikely to be sufficient, the successful marketer must know which sub-sets of these users are at all interested in any form of commercial relationships in their on-line sphere.

One of the major obstacles in relationship marketing is thus how to establish and maintain a relationship between a consumer and a company. Online social networks have the possi-bility of providing the means to successful relationships at a relatively low cost but compa-nies need to understand the expectations of their potential audience and this is where re-search in the context of online social networks is currently lacking. This study has exam-ined university students, a dominant group of users of online social networks, to attempt to identify the consumers’ view on relationship marketing on social networks.

1.3 Purpose

To determine the willingness of university students to engage in relationships with organi-zations on the online social networks Facebook and Twitter and the consumers’ driving motivations behind these relationships.

5

1.4 Research Questions

This study aims to answer the following research questions:

Usage patterns: Which types of organizations do users tend to be interested in form-ing these relationships with and what do they have in common?

Adopter motivation: What tends to motivate users to seek out relationships with commercial organizations on online social networks?

Relationship continuance drivers: Which factors drive users to maintain relationships with organizations on online social networks?

1.5 Definitions

• Diffusion

Refers to the process of diffusion of innovations, a process in which new products, serv-ices and practserv-ices gain popularity within its targeted segment or the overall population. Theory by Everett Rogers, see section 2.1.4.

• High- and Low-involvement

A framework that classifies purchases by the amount of consumer involvement that goes into the decision process, often dependant on the nature and price level of the purchase.

• Marketing Mix

A traditional marketing model that is a key concept in much of the literature in the general field, in particular Kotler, Wong, Saunders & Armstrongs’ Principles of Marketing (2005). It is based on the idea that successful marketing is a result of a proper price, place, product and promotion.

• Opt-in Marketing

As opposed to traditional marketing, opt-in refers to the ability of users to choose whether to be exposed to information from a particular organization. In an opt-in setup, users are assumed to be uninterested until they subscribe to the service.

• Usergroup

A form of sub-network that exists as part of a greater general online network, linking users with some shared given interest together. For example, Universities tend to have user-groups on the Facebook network.

• IRC

IRC is an abbreviation for Internet Relay Chat, an older form of Internet-based chat cre-ated in 1988. It uses special software to allow users to communicate in real-time through a server.

• Social Networks

Social Networks is a broad term that attempts to summarize repeat interactions and con-nections between individuals as parts of a larger network. Online social networks operate in much the same way, but in the context of the Internet.

6 • RSS

RSS is a technology for quickly displaying news items in a standardized format, allowing users to access updated information on computers and mobile phones. Commonly used for web services that update often, such as online newspapers and blogs.

• Feed

General term for an automatically distributed and updated information flow, for example the news feed on Facebook.

1.6 Delimitations

This study does not attempt to explain consumer attitudes towards direct advertising on online media (banners, buttons, skyscrapers etc); it is focused entirely on the type of mar-keting that occurs when marmar-keting information is spread throughout a network by partici-pating organizations and members as a means toward forming and maintaining business-to-consumer relationships.

Given the limited scope of the study it will be limited to the largest open online social net-works, which tend to be aimed towards younger audiences. These networks include the services such as Facebook and Twitter. This is in contrast to closed social networks such as MSN Messenger or ICQ, where communication is almost exclusively one-to-one and where the service acts more as a tool for contacting members of other informal networks than as a network in itself.

The study is cross-sectional, and was conducted in a field where the context tends to change at a fast pace. The research was conducted in a 3-month period of time and this time span is not sufficient to observe attitude changes over time.

7

2 Theoretical Framework

This section introduces current and previous research in relationship marketing, social networking, its appli-cation online, diffusion patterns of innovations as well as viral marketing.

This study makes use of current theoretical knowledge in the fields of relationship market-ing and online social networks, includmarket-ing an overview of social network dynamics. It at-tempts to link these theories to current consumer attitudes towards this form of marketing held by the students who participated in the research to find explanations that are applica-ble to the online social network population. The research has been divided into sections based on their relation to the research questions stated in section 1.4.

2.1 Usage Patterns

2.1.1 Social NetworksOnline social networks are simply an extension of traditional social networks built using modern communications technology, and many of the same dynamics apply. This study at-tempts to link social network theory to behavioral patterns on online networks.

In an article by Dholakia, Bagozzi & Pearo (2004), the researchers built on previous re-search (Bagozzi & Dholakia, 2002) to build a social influence model for consumers partici-pating in virtual communities. They used statistics to compare two settings of virtual com-munities; networks and small groups. By applying theory on social identity and group norms, they aimed to understand the motivations of people joining the two types of social forums.

Dholakia et al. (2004) attempted to group concepts from the different schools based on similarities. The first type are groups where people have close relationships and frequent in-teraction. The second type is social networks and common identity groups. Users in the second type tend to have loose connections and narrowly defined relationships. The re-searchers made use of the term “small group” for the first type of group, and “network community” for the second type (Dholakia et al., 2004).

Since the two different types of communities attract two groups of people with different motivations, the people who manage the community must satisfy those needs. People seek-ing to join network communities tended to have a clear purpose or benefit in mind, for in-stance easy access to gain or share information, while those who choose to join small groups tend to have less tangible and more socially oriented motivations. This is in line with research conducted by McKenna & Bargh (1999) who argued that motivation to join networks tends to stem either from self-oriented or social purposes.

According to this research, people who would be receptive to relationship marketing will naturally tend to be the network community character type (Dholakia et al., 2004). They would want information and palpable benefits for joining the community, and not neces-sarily chat with others in the community. This is as opposed to the small group type, who seeks other features, such as real time chat and social interactions.

8

Dholakia et al. (2004) suggested that the virtual community should not include live chat features, but should have a system in which it is easier to store information and previous conversations to appeal to the network community type of users. Facebook appeals to both groups since many different communication tools are provided.

Joinson (2008); Huberman, Romero & Wu (2008), and a host of other researchers have found that an important driver in behavior and activity on online social networks is the number of ‘friends’ or contacts that they have formalized within these network applica-tions, and the network community users are likely to maintain significant contact lists. The online marketing efforts for the virtual community must fit with the network nity type in order to meet the needs of the people joining the community. Such a commu-nity may for example allow a customer to receive information from the company, and pro-vides the company with a chance to send information in an affordable way to people they know are interested. In some cases the community could eventually turn into more of a small group type, where customers grow closer to each other and to the company in terms of online interaction. Since the needs and expectations of users differ, so will the motiva-tions behind adopting the networks and using it as a tool for new tasks.

2.1.2 Relationship Marketing

This study examines attitudes towards relationship marketing on online social networks, which is part of the larger concept of creating additional value for consumers of a product or service.

Traditionally, research in marketing has been centered on one-way marketing communica-tion to create and fulfill demand (Morgan & Hunt, 1994). In their work Principles of Mar-keting, Kotler et al. (2005) present the marketing process primarily as a sequence controlled by the marketing organization. The process identifies some form of need or want, which describes the underlying cause for demand, and then attempts to create, communicate and deliver a product or service to fulfill the need or want. It is only in recent editions that tools such as the Internet and paradigms such as relationship marketing have gained significant attention.

Kotler et al. (2005) describes marketing as a mix of four factors: Product, Price, Promotion and Place, of which this study primarily concerns the latter two. In this traditional model, very little attention is paid to communication from the consumer to the marketer, and even less attention to communication between consumers. Yet evidence suggests that reliance on the internet as a tool for making purchase decisions is growing at very high rate. Green-span (2002) found that as many as one in third used the internet prior to making high-involvement purchase decisions. This form of pre-purchase research circumvents the tradi-tional model where the marketer is in complete control of the message. Instead, other consumers and unbiased third parties alter the message to reflect their perception of the of-fering, using tools such as online social networks to communicate their views.

This perception is not always based on the actual product. Some organizations compete by offering extra services or additional features for a product; some compete by maintaining a superior brand image (Davis, 2000). Even though the product could have identical per-formance to a lower rated brand, consumers may still prefer the more expensive high-end brand.

9

One way of creating additional value for consumers is relationship marketing. It was an important force in the marketing efforts before the industrial revolution, but as the market developed a more transaction-oriented focus during the industrial era relationship market-ing decreased in importance (Sheth & Parvatiyar, 1995). Competition over customers has increased in recent years and companies are thus finding new ways to satisfy and retain their existing customers, relationship marketing has received much attention during the last two decades as a way of combating the increased competition (Morgan & Hunt, 1994). Godson (2009) defines relationship marketing as a relationship between stakeholders that is mutually beneficial to all the parties involved.

Grönroos (1992) and Godson (2009) argue that the core of relationship marketing is to build value. An organization will not undertake a project aimed at establishing relationships with consumers unless it believes it has something to gain, and consumers will not accept the relationships unless they also feel they derive some form of benefit from it (Godson, 2009). These relationships can be of many different kinds, but they tend to be aimed at in-creasing the perceived benefit a consumer gains from purchasing or using a product (Sheth & Parvatiyar, 1995).

Researchers agree in that relationship marketing offers a way to meet increased global competitiveness but disagree on if relationship marketing is a separate field of study or simply just a result of trying to achieve customer satisfaction – a core concept in marketing. While some of the more traditional researchers such as Petrof (1997) argue that relation-ship marketing is a mere buzzword originating from core marketing concepts such as prof-itability through customer retention and satisfaction. Other researchers such as Christo-pher, Payne, Ballantyne & Pelton (1995) approach relationship marketing differently in that they add on to the traditional 4p model with two additional P’s – processes and people. Re-lationship marketing is treated as a separate field of study from this point on, as it is con-ducted through a separate process of communication from other marketing efforts. Christopher et al. (1995) argue that everything a company does is part of a process (the 5th P) leading to a product or service being delivered to the consumer, process management is hence an integral part in how the company deals with its external and internal environ-ments. People are the 6th P and are viewed as the contributors to the process management and act as the link between customer development and satisfaction (Christopher et al., 1995). Companies communicating with the external environment through the use of social networks may at first not appear dependent on people as facilitators of relationship market-ing efforts, but the negative effects of marketmarket-ing efforts carried out poorly have the poten-tial of being far greater.

2.1.3 Relationships Online

The emergence of the Internet as a dominant technology in international society has fur-ther increased the attention relationship marketing is gaining (Phelps et al., 2004), and it en-ables organizations to connect with thousands or millions of its current and potential con-sumers using minimal resources. In recent years the presence and growth of online social networks has been gaining widespread attention from audiences worldwide (Boyd & Elli-son, 2007) and these networks allow organizations an opportunity to form relationships with consumers at a very low cost.

Godson (2009) identifies two major advantages with relationships online; reaching the con-sumer and being better able to serve the concon-sumer. The market online is vast and the pos-sibility of attracting new customers is enhanced when access to for example other regions is

10

easily facilitated online. Technology allows companies to customize their offerings because each consumer can now be individually served with for example customer profiles (Gor-don, 1998). Companies are therefore able to serve their customers more efficiently than previously (Godson, 2009).

Godson (2009) mentions a major negative aspect of relationships online –impersonality, when all the business is carried out through computers the customer never meets a real person. Egan (2008) points out that it is dangerous to force technology (such as automated call centers) on a consumer as a replacement of human relationships, this is ultimately not a way of building value for the consumer, the most important aspect in relationship market-ing.

Company and customers will interact to gain value, it is therefore critical to find efficient channels of communication between them to maximize the resulting value. Today many customers voluntarily give and receive information from companies through opt-in serv-ices, creating channels through which organizations are able to communicate and gather in-formation about them (Gordon, 1998).

Relationship marketing is not focused on direct marketing, since the cost of gaining cus-tomers by converting them from competitors is greater than attempting to secure the loy-alty of previous customers. Buchanan & Gilles (1990) have claimed that an increase as small as five percent in customers retained can increase profitability by as much as 20%-80%. They also found several reasons explaining this increase in profit. Customers in a suc-cessful relationship are less inclined to switch to a competitor, are more likely to use posi-tive word of mouth, and are more likely to buy complementary goods (Buchanan & Gilles (1990).

Buchanan & Gilles (1990) also found that these effects were the direct results of a success-ful consumer-to-business relationship that would in the end lead to increased profits. This seems to indicate that customers, once they have become a part of a community, would be more attached to the company, instead of its competitors.

It is critical to identify how the advantages of online relationship marketing are being util-ized at the present time. Relationship marketing on social networks is not simply an issue of following a trend, but of integrating popular technology with traditional marketing ef-forts.

2.1.4 Network Diffusion

Whenever a new product, innovation or service is introduced, there is a period of time dur-ing which awareness and knowledge of the product spreads throughout the marketplace. Rogers (1995) introduced the theory of Diffusion of Innovations, and today it is one of the most cited theories in marketing. Diffusion can be thought of as a pattern in which infor-mation is carried forward and disseminated, and the theory attempts to explain how and why different audiences adopt new innovations at different points in time (Robertson, 1967).

The diffusion process starts with awareness of a new innovation, where any one potential customer learns of the existence and basic nature of the new product. The consumer then learns more about the product as time passes, and eventually evaluates it based on personal preferences, knowledge of the product and the existence of any needs that the product or

11

service fulfills. Following this evaluation the potential customer decides whether or not to try the innovation (Rogers, 1995).

This is not necessarily a conscious process, and the period of the time over which it stretches can differ dramatically (Rogers, 1995). Because of the large differences in rate of adoption, it is possible to divide consumers of most successful innovations into several categories depending on the rate at which they adopt new products and services, and Rogers found that the percentage of consumers that belong to these group roughly form the distribution of a normal bell curve if placed along a timeline axes of the adoption proc-ess.

E. Rogers, Diffusion of Innovations, 4th Edition, 1995

The Early and Late Majority make up the main segment of the population and are naturally the most profitable segments, but they may have higher barriers towards trying new inno-vations that they know little about. The Laggards make up the rightmost tail of the distri-bution and will either adopt the new innovation when it is relatively old, or never at all (Robertson, 1967). In the context of online social networks, users can be segmented into the different categories depending on at what time they began using these networks. Users who started using the networks several years ago will likely belong to the early adopters or early majority segments.

2.2 Adopter Motivation

2.2.1 Adoption DriversDifferent forms of networks and groups have different levels of barriers towards entry. The popular social networks encountered on the internet tend to be open and welcoming to new adopters, but are equally easy to unsubscribe from. To further understand what drives consumers towards forming relationships with organizations online, it is important to gain an understanding of why adopters want to be part of online communities.

As mentioned in section 2.1.2 Dholakia et al. (2004) argued that there are two different types of network users; one type who seeks information, and one that is driven by a need for social interaction. Therefore, the two types seek different types of communities. If a person wants information on a product, they would be likely to seek out a network-based community, rather than the small group type community.

12

For a community to function properly, there must be somebody creating and assembling the information in question, and somebody else that processes and absorbs it. Hennig-Thurau & Walsh (2003) performed research on why people tend to read posts provided by others in online communities. They found five different reasons for this, and the dominant reason was that the readers could be better informed when making purchase decisions and be so much faster than by using other forms of media. Customers tend to be affected by these posts in both the informational sense (a product is good or bad) and the social sense (values and behavior).

Hennig-Thurau, Gwinner, Walsh & Gremler (2004) continued this research by investigat-ing the reasons for postinvestigat-ing messages on the online communities. They found eight major reasons for this form of word of mouth that are very similar to the motivations behind tra-ditional non-electronic word of mouth.

These eight reasons for posting were: (1) Platform assistance (2) Venting negative feelings (3) Concern for other consumers

(4) Extraversion/positive self-enhancement (5) Social benefits

(6) Economic benefits (7) Helping the company (8) Advice seeking

The researchers found that the most important incentive was the fifth one, social benefits. All of these influence a person to both visit the community and to post messages. Finally they segmented the consumers they had studied according to the eight reasons that they had established. Through hierarchical cluster analysis they established four segments which all had in common that the strongest reason for publishing online content was concern for other consumers. They instead focused on the second strongest reason to differentiate the segments and found that:

• Segment (1), self-interested helpers, are driven by economic reasons.

• Segment (2), multiple-motive consumers, are driven by many different reasons with none of them particularly standing out.

• Segment (3), consumer advocates, named so because they are concerned about the other consumers’ interests.

• Segment (4), true altruists, care about both other consumers and companies. Füller, Jawecki & Mühlbacher (2007) found that highly dedicated consumers in Nike’s on-line basketball community actively tried to get in touch with their preferred brand, and Füller along with other researchers later on studied the willingness of consumers to co-create products with a brand or company (Füller, Matzler & Hoppe, 2008). They concluded that although consumers feel innovative, they do not necessarily want to contribute to their brand of choice. Having a strong brand commitment does not necessarily mean that con-sumers want to participate in innovate projects.

Füller et al. (2008) also found that people do not often join the communities because they want to contribute an innovative idea to their brand. Instead, having already become mem-bers of a community the consumers later on become willing to participate in various

inno-13

vative projects with the brand. These tend to be the people who in the Hennig-Tharau et al. (2004) study would be classified as true altruists.

Paterson (2009) summarized the main motives for consumers to enter online communities to be either the sociability of communities, value of content, and how well the community supplies customer support and service. This is consistent with the previously mentioned motives to joining. She also found that these reasons are a factor when it comes to staying in the community and to actively participate in it. While the motivations behind joining the online social networks that are not centered around a product are likely to be focused around sociability, organizations have an interest in attempting to capitalize on the interest potential adopters have in finding information and other content of value to them within the networks.

2.2.2 Viral Relationship Marketing

The Blackwell Dictionary of Marketing defines viral marketing as:

“Viral marketing is the term applied to an Internet-based promotional strategy that encour-ages users to transfer to others a fixed marketing communications message, usually without the volition of either sender or recipient.” (Littler & Lewis, 2008)

It is essentially the process of diffusion of information over a formal or informal social network (Leskovec et al., 2007). Whereas direct marketing tends to be based on the idea that a message is communicated to one receiver who then decides to adopt or not to adopt the product, viral marketing focuses on the cascade effect that occurs when message re-ceivers voluntarily choose to carry the message forward to others. In essence, viral market-ing attempts to use existmarket-ing social networks to get potential adopters to spread the informa-tion to their friends and associates (Wilson, 2000).

This form of marketing is powerful because the product is being endorsed by a friend ra-ther than some one being paid to do it (Jurvetson, 2000). People tend to be less skeptical towards messages that are assumed to be given without any commercial interests involved, and if these messages are found interesting people may even choose to pass it onwards. However, this does not mean that every person is equally susceptible to viral marketing. A person will not take as much notice if they receive a lot of these types of messages every day. In fact it is important to examine the typology and general interests of the social community members for there to be an epidemic effect with the marketing effort (Lesko-vec et al. 2007).

A major problem in viral marketing is the difficulty in making a message that will actually achieve a viral effect, and determining who will reliably spread it (Watts & Peretti, 2007). It is widely held that there are a multitude of factors determining whether viral marketing is or is not suitable for the diffusion of a particular marketing message (Leskovec et al., 2007), and this may even be changing as the nature and extent of social networks changes. Some products may simply not generate the consumer involvement that is required for a sus-tained cascade effect, and on occasion the message is negatively received to the extent that a viral effect that ends up harming the product image is created (Moore, 2003).

In order for a successful viral diffusion to occur, there must be some underlying motivation for the user to pass on the information to his or her peers. Whether the message is simply to join an online community or to make some kind of moral stand, the user must first have

14

been interested enough to seek out the message and then convinced enough to act as a vo-lunteer messenger towards other users.

Social Rewards

Wilson (2000) found that one core motivation behind passing on viral messages is unre-lated to the message itself. Many users will simply choose to forward messages for the pur-pose of maintaining a relationship with another user, in much the same way as any form of small talk. Rather than discussing a topic a user will start a conversation by passing on an interesting viral message, such as a hyperlink to a web-based video clip. Therefore, viral messages may have a natural tendency to spread through informal networks simply because they fulfill a social function (Wilson, 2000).

In terms of content, Dobele, Lindgreen, Beverland, Vanhamme & van Wijk (2007) found that successful viral marketing campaigns tend to target one or more of the primary emo-tions: Surprise, Joy, Sadness, Anger, Fear and Disgust.

The vast majority included an element of surprise, which the researchers found to be the most critical emotion for inciting an urge to forward viral messages, which is consistent with the findings of Lindgreen & Vanhamme (2005). They also found that surprise in itself does not generate enough interest to create a viral reaction, the message also needs to con-tain at least one other primary emotion to be effective. Hence, a message could for example surprise and amuse, or surprise and scare the user. Which emotions to target will depend on the image the marketer is trying to create, thus campaigns based around products in-tended for amusement will tend to make use of Joy as the primary emotion.

There will be external effects on which emotions can be successfully utilized depending on which market segment is being targeted. For example, Dobele et al. (2007) found that there is a difference in behavior between genders – With male users being more likely to pass on messages based around the primary emotions fear and disgust than female users.

Personal Benefits

Subramani & Rajagopalan (2003) base their framework of research on viral marketing around the idea that different users have different potential rewards and benefits from passing on messages through informal networks. Some messages may not be rewarding to pass on except for the social rewards explained in the section above, but there are situa-tions where the size of the group of users convinced by the viral message directly affects the benefits each user receives (Phelps et al., 2004).

Viral Frequency and Response

Viral marketing is a relatively cheap and a powerful way for information to be passed on to new potential consumers (Portsmouth, 2003), but it is important to understand whether people respond negatively or positively to viral activities in the communities. A major dif-ference between online communities and using e-mail is that it is possible to post a mes-sage in general manner so many people can see it, while at the same time being able to send a private message should the need arise.

This study examines two forms of viral marketing. The first form of viral marketing is ac-tive in the sense that consumers acac-tively choose to forward information concerning a rela-tionship to friends and contacts. The second form is passive and relies on automatic notifi-cations forwarded to these friends and contacts by the social network system. The

motiva-15

tions behind viral activities become an issue within active viral marketing, while passive ef-fects bypass this issue entirely.

2.3 Relationship Continuance Drivers

2.3.1 Social Media IntegrationMangold & Faulds (2009) have developed concrete suggestions for how companies can in-tegrate social networks into their existing promotional mix. They argue that social media not only allows companies access to their consumers and an ability for open dialogue be-tween them but also allows consumers the ability to talk to each other. The very nature of social media does however leave the company with limited ability to actually influence these conversations.

With the tools of social media a dissatisfied consumer has the ability to share his or her opinion to millions instead of simply a handful of friends and relatives (Gillin, 2007), which turns social media into an accelerated form of word of mouth. This means that the compa-nies get less control over the flow of information between customers, as noted by Vollmer & Precourt (2008). Because of this Mangold & Faulds (2009) argue that the traditional communications paradigm has to give way for a new paradigm that integrates tools to deal with social media, and they provide the following suggestions for how companies can inte-grate relationship marketing with social media:

• Provide networking platforms

They suggest that organizations should attempt to form platforms and networks that consumers can use to communicate and share information. This has several advantages, such as maintaining a degree of control over the flow of information.

• Use blogs and other social media tools to engage consumers.

These blogs and tools can be used to enable customers to give feedback on products and encourage honest open communication, ideally benefiting both sender and re-ceiver. This technique has for example been used by software-related firms to communicate with its consumer base.

• Use both traditional and Internet-based promotional tools to engage consumers

It is important to tie in other tools of the promotional mix into social media, such as lotteries, giveaways, and voting. The Internet should primarily be seen as one tool of many, and should complement rather than replace.

• Provide information

Many products can be of more use to an informed consumer, and many companies are in a position to provide information that customers can use to increase the benefit they derive from using their products. Liquor companies such as Grey Goose provide ela-borate cocktail recipes on their websites, and many consumer products can see broader use with similar information.

• Provide exclusivity

Exclusivity can be a powerful motivator in that it provides the consumer with an added incentive towards forming and maintaining a relationship with the organization. If the same benefit can be gained in other ways, these relationships will not seem as lucrative. Exclusive deals just available to a certain subset of consumers will tend to generate ad-ditional interest.

16

• Design products with talking points and consumers’ self images in mind

It may seem intuitive to think of relationship marketing as a tool that is involved after the product is designed and finished, but its benefits can be increased by considering it as an essential element of the design process right from the start. Talking points allow for a higher likelihood of word of mouth: simple features are easier to communicate than complex, and fun, intriguing, highly visible, easy to use products are more likely to stimulate conversation.

• Support causes that are important to consumers

Another popular approach is to integrate social responsibility into relationship market-ing, because it tends to translate well to the online network context. In this setting it is relatively easy to communicate the message of acting in a responsible manner to a large number of consumers and potential consumers.

• Utilize the power of stories

Stories can create vivid memories that are easily spread through word of mouth, whether it is a consumers’ story or a story from the company. These stories form an experience for the consumer, who ideally will tend to relate the company and its brand to this story in the future.

2.3.2 Message Control

Mangold & Faulds (2009) conclude their study by stating that even though an organization and its management does not have an ability to control the flow of information regarding itself or its products throughout social media, this does not mean it should not attempt to gain as much of this control as possible and most importantly at least try to influence these communication channels in order to get their marketing communication across.

An organization should strive towards not only maintaining a presence in the evolving so-cial media context, but to integrate this form of communication with its other marketing practices (Mangold & Faulds, 2009). This way of integrating the marketing efforts in the online social environment in a proper way is important. Boone & Kurtz (2007) found it ne-cessary to coordinate all of the firms marketing efforts to get a consistent message across to the consumers.

The types of values identified by Mangold & Faulds (2009) are important when marketing is applied to social networks. These attributes provide distinct advice and suggestions for marketers in how to appeal to the consumer, and it is important to investigate how the consumer views these suggestions. Ultimately the success of maintaining relationships with consumers online will be dependent on the consumers’ perception of the value added by continuing the relationship.

17

3 Methodology

This section will introduce the research methods that this study made use of, what part they play in the greater whole, as well as the fundamental limitations of the study and each form of data collection.

This study employed inductive research (Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill, 2007) to gain an overview of students’ attitudes towards relationship marketing on online social networks. For the purpose of this study the consumer is to be considered the unit of analysis (Saun-ders et al, 2007), and the types of organizations and industries used during the research is intended purely as examples to simplify data collection. This study was conducted over a short period of time (3 months) and is cross-sectional in nature.

The study is mixed method in nature, and employs both quantitative and qualitative re-search methods. The survey described in 3.1 allows respondents to answer multiple-choice questions and was analyzed quantitatively. The focus group study described in 3.2 was en-tirely qualitative in nature. Mixed method research aims to utilize the objectivity and reli-ability of quantitative research with the explanatory strength of qualitative methods (Ta-shakkori & Teddlie, 2003).

Mixed methods are particularly suited for inductive research, where quantitative and quali-tative data can be used interdependently to generate explanations for patterns that occur, care must however be taken to avoid subjectivity (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, 2004). The mixed method approach that is utilized is essentially a form of cross-methods triangulation (Jick, 1979), where multiple methods are used to verify whether similar conclusions are reached. While the sample groups for the two research methods employed were not identi-cal, the majority of focus group respondents participated in the survey study.

Online social networks have a high degree of market penetration in the university setting worldwide (Gross & Acquisti, 2005), which allows access to a sample group that reflect a very large part of the overall population that are users of these networks. Previous research was used to formulate a survey that attempts to explore the different dimensions of the problem. The survey was distributed to students across multiple university faculties.

Prior to reaching the final conclusions a focus group was conducted in order to discuss the findings with an audience that were not biased from having conducted research in the area. The focus group was carried out in order to prevent fundamental errors that can arise from misunderstandings and questions that were unintentionally flawed, or from contamination due to factors such as bias towards socially desirable answers (Dillman, 2000). Focus groups are multi-participant studies that make use of group interaction to gather data and reach conclusions (Kitzinger, 1994).

3.1 Survey

The aim of the survey was to gather descriptive primary data towards answering the re-search questions. It targeted university students’ belonging to faculties represented at Jönköping University and made inquires about past experiences of online social networks and attitudes towards relationship marketing efforts on these networks. Due to the high degree of market penetration in the targeted setting and the purpose of this report, respon-dents that did not use online social networks were considered non-responrespon-dents. These re-spondents made up less than 5% of the survey rere-spondents. It was important to filter out

18

these respondents since having them answer the survey without the proper knowledge about the networks results in unwanted results since the remainder of the survey assumed that the subject did use one or more of these networks.

The survey design was based on similar research conducted by a host of other researchers and covers a relatively broad set of variables for analyzing consumer perception of relation-ship marketing on online social networks.

3.1.1 Survey Design

The survey was designed as a self-administered questionnaire (Saunders et al., 2007) deliv-ered in a classroom setting. This method had the benefit of distribution to a high number of respondents, primarily because classroom norms tend to prohibit students from leaving the room before the survey had been completed by their peers. This had the benefit of re-ducing respondent bias, where the students who happen to be interested in the subject were the one’s responding to the survey.

The available time frame for administering each survey was limited, because of each survey session being conducted during classroom time with people that have other obligations. The time required to answer the survey was therefore limited to 10 minutes or less, and with questions designed with simplicity that was in line with this time frame. The survey made extensive use of multiple choice questions to allow for this.

The survey was designed to cover three general areas: general sample attributes as well as usage patterns and adopter motivation of relationship marketing on online social networks. The third area of interest in this study, relationship continuance drivers, was primarily stud-ied qualitatively through the focus group study.

General Attributes

Research within this area of study tends to make use of attributes that divide the sample in-to smaller but significant groups. Gross & Acquisti (2005) used gender as an attribute in their research, and it is likely to be one of the most commonly used variables overall since it is of relevance in such an enormous range of fields. Joinson (2008) used age as an attrib-ute variable in his research on use of Facebook, and it is another commonly used variable for data analysis. Etter & Perneger (1997) found that both these variables tend to be linked to non-response biases, and care must be taken to avoid this form of bias.

Usage Patterns

McKenna & Bargh (1999) used amount of online activity as a behavioral variable in her re-search on online social networks and found that it explained differences in attitudes and behavior. This variable was included because users who spend large amounts of time online are also likely to be open to performing more actions online, such as communicating with companies. This category of variables also includes questions about which form of services users would be willing to perform online in the near future.

Eccleston & Griseri (2008) based a large part of their research on simple binary behavioral variables involving past and current actions, such as whether a user had previously at-tempted to convince others to purchase a product. Similar variables can be used to deter-mine whether users are currently maintaining relationships with any commercial organiza-tions on online social networks, and whether they had attempted to convince a friend to join.

19

Online social networks have a rich culture of passing messages forward, and this dimension is included in the study because it is one of the key ways organizations can generate aware-ness of their presence within the networks. Dobele et al. (2007) argued that the motivation to pass information forward tends to be triggered by different sets of emotions. For exam-ple, a user may choose to invite a friend to an open user group based around an amusing video, or an event that makes him or her angry.

Adopter Motivation

Kotler et al. (2005) discussed the issues of the consumer value in relationship marketing, in particular that the consumer must be interested in obtaining some benefit from engaging in relationships with companies. The survey incorporates this by asking about the benefits the adopters were interested in, and from which types of organizations. Wiseman (1972) ar-gued that opinion variables tend to be easily contaminated by improper use of methods, and great care must be taken to avoid questions leading the respondent to one of the alter-natives in a question.

The survey made use of this concept in addition to the Viral Marketing Framework sug-gested by Subramani & Rajagopalan (2003), which is based on the idea that users have dif-ferent motives for passing on messages and recommending others to join networks – both selfish and altruistic. These factors were implemented into the survey by inquiring about vi-ral behavior and underlying motivations.

3.1.2 Sample Selection

The sample group the survey was administered to was selected among students at Jönköping University in November 2009. The study was conducted at the beginning of in-class sessions at the engineering, business and teaching faculties with the cooperation of the professors hosting the lectures. This context has the benefit of reducing nonresponse bias based on interest, because the students have no incentive such as time constraints to de-cline to answer the survey. Armstrong & Overton (1997) argue that the most efficient way of avoiding nonresponse bias is to avoid or reduce nonresponse, this has been avoided by administering the survey in an in-class setting.

To allow for high diversity in gender and faculty representation stratified random sampling was used (Patton, 1990) to select classes to attend and conduct the survey at. The strata cri-teria used was hosting faculty, and the survey contains responses from four randomly se-lected lectures at the different faculties. This form of purposeful sampling allows research-ers to reduce the risk of creating a sample that is not representative for the population (Saunders et al., 2007). The engineering faculty at Jönköping University is highly dominated by male students, while the teaching and business faculties have some overrepresentation by female students. Using hosting faculty as sampling criteria therefore allows for a sample that has an even gender balance, without polluting the sample by limiting it to one particu-lar faculty or program.

There were a total of 195 respondents, 95 males, 100 females, with an additional 7 non-respondents (not included in the total). 38 of the non-respondents were from the engineering faculty, 73 were from the education and communication faculty and 84 were from the business and economics faculty. The student groups primarily consisted of Swedish stu-dents, with a small amount of international students.

20

3.1.3 Data Quality

The non-response rate of the survey study was less than 5% of the total surveys adminis-tered, which should be considered to be very low. This primarily stems from the setting the survey was administered in, and reduces the risk of non-response bias (Saunders et al., 2007).

In quantitative research care must be taken to ensure validity. Given the descriptive nature of this survey the primary issue is external validity, to which degree it is possible to apply the results and conclusions drawn from one group or sample on the full population or on other specific groups (Calder, Phillips & Tybout, 1982). The sample drawn from Jönköping University is likely to be transferable to students in Sweden in general, and is likely to be applicable to other student bodies in similar cultural contexts.

Another issue in research with pre-defined answers is ‘meaning units’, which in the context of the survey would be an alternative on a multiple choice question. When a meaning unit is too broad and fragmented, the conclusions drawn from are likely to be weak (Graneheim & Lundman, 2003). The problem of fragmentation in the survey has been reduced by hav-ing a relatively large amount of alternatives as well as the option of providhav-ing open-ended input.

It is unlikely to be applicable on the full general population, but may have limited applica-bility on early adopter groups that share student adoption patterns. This study is aimed at determining attitudes of users of these networks, and at present these networks are popu-lated primarily by people in similar age groups as students. The conclusions are therefore expected to apply to young adult users of online social networks in general.

With the great amount of students (i.e. people of age 18-25) in the online social network population (Gross & Acquisti, 2005), the sample was proposed to be sufficiently accurate in terms of sample size to have a high degree of validity.

3.1.4 Pilot Study

An inherent weakness in any form of questionnaire is that the researchers who designed it tend to possess a much higher degree of knowledge in the subject than the respondents, as well as an awareness of what it is that the study in question aims to determine. Therefore it is important to attempt to minimize the risk of formulating questions that are either am-biguous, unclear or self-answering (Saunders et al., 2007).

Bell (2005) recommends all researchers to perform a pilot study before finalizing the survey design and layout, to attempt to weed out these errors. A pilot study is conducted by letting a limited amount of respondents answer the survey and use their performance as feedback towards the survey design. In some instances the respondents will simply ask the researcher administering the survey to clarify a question or statement, but Fink (2003) argues that re-searchers should also look through the answers given and see whether all instructions were carried out properly.

A pilot study was performed by allowing a handful of individuals in a university setting to complete the survey while being allowed to ask the person administering the survey any questions they may have. These individuals were selected from people with various knowl-edge in social networks and had vastly different levels of familiarity with the concepts the survey concerns. Following this pilot study certain questions were reformulated especially