Deeming Damascus ‘safe’:

The Aspiration of Danish State Actors to ‘Return’ Syrian Nationals to

the Damascus Region

Emma Gade Nielsen

International Migration and Ethnic Relations Two-year Master’s program

Master thesis 30 credits Spring 2020: IM639L-GP766 Supervisor: Jason Tucker Word count: 21.989

Abstract

This paper examines the intensified focus on ‘return’ in Danish asylum policy and the changed approach to the assessment of revocation of residence permits and asylum claims made by Syrian nationals. The aim of the study is to understand the interplay between Danish state actors and the Refugee Appeals Board and their tactics of legitimization in adopting this new approach and rejecting asylum protection to three Syrian nationals. The study concludes that discourses linking asylum protection to ‘international obligations’, refugee status to ‘return’ and ‘the refugee’ to an essentialist understanding of the term are fundamental in facilitating the decisions made in the cases. Furthermore, a governmental goal of ensuring ‘the security of society’, that is, the Danish population defined in national terms, underpins and works to sustain these discourses. The findings contribute to creating detailed knowledge about the Danish asylum system and the logic supporting the increased focus on ‘return’.

Word count: 150

Keywords:

Table of contents

1. Introduction………...…6-7

1.1. Motivation and Aim of the Thesis………..…..6-7 1.2. Research Questions………..7

2. Background Information………....8-11

2.1. Danish Policies on Asylum Protection………8 2.2. The Danish Ministry of Immigration and Integration and the DIS………..8-9 2.3. The Danish Refugee Appeals Board……….…….9-11

3. Previous Research………..…11-17

3.1. The Increased Focus on Deportation………11-13 3.2. Deportation Regime(s)?...13-14 3.3. Legal Aspects of the Right of States to ‘Return Refugees’………..15-16 3.4. Deportation and Detention………...…….16-17

4. Research Design………...17-20

4.1. Case Based Research………17-18 4.2. Trade-offs, Validity and Reliability………..…18-19 4.3. Contribution………..19-20 4.4. Data and delimitations………..….20

5. Methodology………...21-27

5.1.Content Analysis and Coding……….21 5.2. Discourse Analysis as Theory and Method………..…21-25 5.2.1. Choice of Theoretical Framework………...……..21-22 5.2.2. Laclau & Mouffe’s Discourse Theory………..…….23-25 5.3. The Toolbox of Governmentality……….25-27 5.3.1. What is Governmentality?...25-26 5.3.2. The Governmentalization of Deportation………..26-27 5.3.3. Enabling “Raison d’état”………....27

6. Analysis of the empirical material………...…28-40

6.1. The Main Similarities and Differences between the cases………...28-32 6.1.1. The Six Test Cases of June 2019………...…28-29 6.1.2. The Three Cases of December 2019………...30 6.1.3. Comparison of the Decisions by the Board in the Cases………31-32 6.2. The Framing of Asylum Protection and Return………..….32-40

6.2.1. The Significance of ‘Trustworthiness’………..……32-33 6.2.2. The Construction of ‘Truth’………..…33-35 6.2.3. The Role of Human Rights and ‘International Obligations’……….…35-36 6.2.4. Temporariness and ‘Return’………..36-37 6.2.5. Effectiveness and Control.……….37-38 6.2.6. ‘Return’, Responsibility and Blame………..39-40

7. Discourses and Antagonisms………..…..40-45

7.1. ‘International Obligations’ or Human Rights?... 40-43 7.2. Integration vs. ‘Return’……… 43-44 7.3. ‘The Truth’ and ‘Assumptions’………... 44-45

8. Governmentality………...….45-51

8.1. Power, Knowledge and Truth………...……46-47 8.2. The Governmentalization of Government………48-50 8.3. Success and Failure of Government………...…..50-51

9. The Implications of the Discourses and Governmental Strategies………...52-56 10. Conclusion………..56-57 11. References………...…58-69 12. Appendices………...70-71

Table of Figures

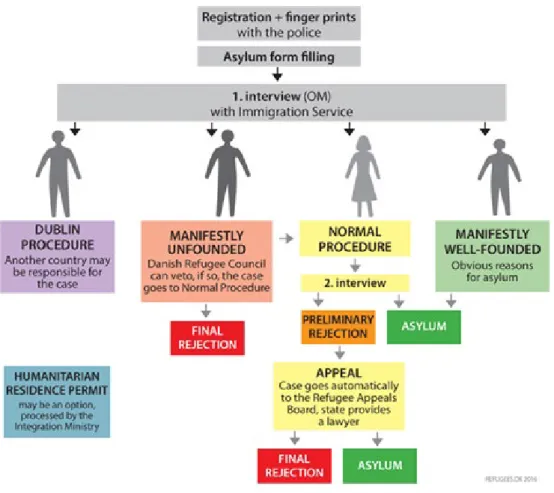

Figure 1: Flowchart of the Asylum Procedure in Denmark……….10

List of Tables

Table 1: Schedule of the Overturned Cases……….28 Table 2: Schedule of the Rejected Cases……….30

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation and Aim of the Thesis

In the Spring of 2019 the Danish Immigration Service, henceforth the DIS, decided to revoke the residence permits of six Syrian nationals from the Damascus region, arguing that Damascus was safe enough for some Syrians to return. This meant that Denmark could be the first EU member state to deport or ‘forcibly repatriate’ Syrians. However, when the cases reached the Danish Refugee Appeals Board, the decisions were annulled and the Syrians were granted residence permits based on individual circumstances – earlier the residence permits in these cases were granted due to the general circumstances in Syria and the Damascus region (Graversen & Kamil 2019). The foundation of these decisions hinted at the possible deportation of Syrian nationals in other cases if the need for individual protection could not be established. This indication was to be taken seriously because in December 2019, the Refugee Appeals Board ratified the decision of the DIS to reject asylum protection to three Syrian nationals (Mortensen 2019). The DIS has earlier been criticized for making discretionary decisions based on Country of Origin Information Reports, henceforth COI-reports, wherein the security conditions of different countries are assessed. Some researchers deem that the quality and credibility of these reports differ a lot from one report to another (FMRC 2018, 15). The DIS’ push for deportations to Syria might be connected to the intensified focus on ‘return’ introduced with the L140 bill (Folketinget 2019) to secure the ‘return’ of refugees to their home country when protection is ‘no longer needed’. This has been referred to as ‘the paradigm shift’ in Danish immigration and asylum policy (Ingvorsen 2019).

The focus of nation states on deporting ‘unwanted nationals’ is not something entirely new; various scholars have attempted to explain the large amount of attention directed towards deportation since the beginning of the 2000s (Kanstroom 2000; Walters 2002; Schuster 2005; Bloch & Schuster 2005). Since 2015 however, the European Commission and member states have put significant efforts into making returns more ‘effective’ and this push for higher return rates can partly be understood as a reaction to the higher than usual number of asylum seekers arriving in 2015 (ECRE 2019a). In the recent years, this number has dramatically decreased in Denmark (UIM 2019a), but this has not turned the focus away from optimizing the practice of ‘return’ or deportation of, for example, rejected asylum seekers (ECRE 2019a). Denmark represents a special case amongst the European countries in rejecting asylum protection to

Syrian asylum seekers, aspiring to revoke residence permits from Syrian refugees and ‘return’ them to the Damascus region in Syria – a place that only a few other EU member states (such as Sweden) have recently deemed safe enough for ‘return’ (ECRE 2019b).

This thesis takes form as a case study and seeks to explore the justifications of and the underlying assumptions behind the outcome of the before-mentioned cases. To accomplish this, the paper provides an investigation of the differences and similarities between the cases of the six Syrian nationals that were granted asylum protection and those three that were not. This involves a comparison of the cases in terms of the factors considered in the decisions of the Refugees Appeals Board which is achieved through content analysis and coding. The thesis also aims to understand the interplay and tension between the DIS, the Ministry of Immigration and Integration and the Refugee Appeals Board and their tactics of legitimization in granting and rejecting asylum protection to the nine Syrian nationals. To investigate this, a discourse analysis is employed to analyze the cases and relevant material produced by the DIS, the Ministry and the Board. Furthermore, a governmentality aspect is applied to the case by operationalizing the theoretical toolbox provided by Walters (2012) to help solve the puzzle presented above.

1.2. Research Questions

The main research question examined in this study is: How can we understand the recent events of Danish state actors aspiring to ‘return’ Syrian nationals to the Damascus region as well as the assumptions, tactics and logic facilitating the decisions made in the cases?

The sub-questions guiding the thesis in answering the main research question are:

1) What are the main similarities and differences between the cases of the six Syrian nationals granted residence permit by the Board in June 2019 and the three Syrian nationals rejected in their appeal for asylum protection in December 2019?

2) How is asylum protection and ‘return’ framed in recent material (policies, reports and website content) produced by the Ministry of Immigration and Integration, the Refugee Appeals Board and the DIS?

3) How is the decision not to provide asylum protection to the three Syrian nationals and possibly ‘return’ them to the Damascus region justified by the Ministry and the agencies involved in the assessment of asylum claims and how is this justification made possible?

2. Background Information

2.1. Danish Policies on Asylum Protection

The first Danish Aliens’ Act was introduced in 1983 and was claimed to be “the world’s most

liberal asylum legislation” by several international observers (Gammeltoft-Hansen 2017, 99).

However, over the two previous decades, several restrictive policies on both asylum and immigration have been imposed. Gammeltoft-Hansen argued that in 2017 we saw a re-emergence of indirect deterrence in Danish policies, that is, policies designed to make the asylum system and protection conditions appear as unattractive as possible as a measure to ‘push’ asylum-seekers towards other countries. This is also referred to as ‘negative nation branding’ (ibid., 100). It should be noted that the pace of amendments made to the Act has changed significantly from 2002; the Act was amended 25 times from 1986 to 2002 but from 2002 to 2016 it was amended 93 times. This means a rate of over one amendment every two months and shows the growing politicization of the issue (ibid., 102).

An example of the employed strategy by Danish authorities regarding indirect deterrence is the ‘temporary protection status’ (7,3-status) for those fleeing general violence and armed conflict introduced in 2015. With this status, residence permits are granted for a period of only one year. This ensures that cases are reviewed regularly in order to assess whether there is a continued ‘need for protection’ in the cases (Gammeltoft-Hansen & Tan 2017, 38). For other categories of refugees, the duration of residence permits has also been reduced from five years to two years for Convention refugees (7,1-status) and one year for those who obtain ‘protection status’ (7,2-status). Furthermore, for refugees wanting to obtain a permanent residence permit, new requirements have been introduced regarding language and employment, and the waiting period for applying was extended to six years in 2016 (Gammeltoft-Hansen 2017, 105). This has been extended even further to eight years as part of the restrictive measures implemented by the Liberal Party (Venstre) during their time of ruling before the social-democratic government led by Mette Frederiksen replaced them in June 2019 (UIM, 2019h).

2.2.The Danish Ministry of Immigration and Integration and the DIS

The Danish Ministry of Immigration and Integration is responsible for the following areas: residency, citizenship, Danish language training and tests for immigrants, integration, prevention of extremism and radicalization as well as honor-related conflicts and negative

social control. The current Minister of Immigration and Integration is Mattias Tesfaye from the party ‘The Social Democrats’ (Socialdemokraterne). Before Tesfaye held the position, the Ministry posted a list of all the restrictions on the area of aliens (with regard to naturalization, asylum, return, family reunification, permanent residency, expulsion and more) implemented under the previous Minister Støjberg from ‘The Liberal Party’ over a period of 4 years. The list shows a total of 114 restrictions (UIM 2019h). However, the present Minister Tesfaye and the Social Democrats announced explicitly both during and after the election that the Social Democrats would continue in the same direction as the former government with regard to keeping a restrictive immigration and asylum policy (Tesfaye 2019).

The Ministry has two agencies working under them: the DIS and the Agency for International Recruitment and Integration. The last-mentioned agency deals with application for residency related to work, studying, au-pair stays and internships. The DIS however, is responsible for applications regarding family reunification, asylum, permanent residency and visitor’s visas (UIM 2020a). One of their main areas of work is assessing asylum cases and deciding whether asylum seekers should obtain permission to stay or if they should be denied residence in Denmark(UIM 2020a). Unfortunately, it is not possible to gain access to the first instance decisions made by DIS in the cases examined in this study.

2.3. The Danish Refugee Appeals Board

The Refugee Appeals Board is described as an “independent administrative body akin to a court

of justice” (Flygtningenævnet 2014). It is emphasized on the Board’s own website that it is

independent of political processes and that it cannot receive directives from the government nor the parliament. It is also emphasized that its members are likewise independent and that they are not allowed to receive or seek instructions outside the Board. As Figure 1 shows, the Board handles appeals regarding asylum decisions made by the DIS and rejected cases are automatically appealed to the Board. On their website, it is stated that decisions taken by the Board are final and that there are no other options for appeal (Flygtningenævnet 2017). However, it is possible to re-open the case (this normally takes around 15 months) under certain conditions (Refugees 2019).

Figure 1: Flowchart of the Asylum Procedure in Denmark (Source: Refugees 2018)

The Refugee Appeals Board consists of a president and a number of vice-presidents who are all judges, 23 in total. Apart from that, 19 members are appointed by the Council of Law / the Danish Bar and Law Society and 38 members are appointed by the Minister of Immigration and Integration. When assessing cases, only three people are involved and present: the president or one of the vice-presidents, one judge and one member appointed by the Ministry of Immigration and Integration. The decisions are made based on what the majority votes and every member has one vote (Retsinformation 2017). The cases treated by the Board can be of different character. In this study, the cases of interest are ‘cases of discontinuation’ and ‘spontaneous cases’. They are defined as “cases where the Immigration Service has impounded

or refused to extend a residence permit with reference to paragraph 7 and 19-20 of the Aliens Consolidations Act” (cases of discontinuation) and cases which involve the rejection of an

Paragraph 7 of the Alien’s Act defines who can be regarded as a refugee in a legal aspect and there are three different statuses regarding asylum protection referred to as 7,1-status (convention status), 7,2-status (individual temporary protection status) and 7,3-status (general temporary protection status). In all the subsections, it is clearly emphasized that the stay in Denmark obtained through asylum protection with reference to one of these paragraphs should be regarded as temporary (The Alien’s Consolidation’s Act, 7). Paragraph 19 and 20 of the Aliens’ Act define cases where a residence permit may be revoked, for example: “(…) if the

alien holds a residence permit under section 7 or 8 and the conditions on which the residence permit is based have changed in such a manner that the alien no longer risks persecution as set out in sections 7 and 8 (…)” (The Aliens Consolidation Act, 19,1). Five of the Syrian

nationals in the six ‘test cases’1 examined in this study are examples ‘cases of discontinuation’

in which their residence permits were revoked by the DIS. They all held the 7,3-status which renders the refugee one year of protection in Denmark. It is not clearly stated whether the last appellant (of case 5) held a 7,3-status or if this case is the first assessment of her claim to asylum. Regarding the three cases in which the decisions of the DIS to reject asylum protection were ratified by the Board in December 2019, these Syrian women did not hold a protection status and thus, their cases can be termed ‘spontaneous cases’2.

3. Previous Research

3.1.The Increased Focus on Deportation

The research field on deportation and return of refugees and rejected asylum seekers is wide and has been a focus of many scholars. However, the literature on governmentality in relation to deportation and return is more limited. Deportation has been studied in connection to detention, asylum regimes and citizenship to explain the focus of states on deportation as a method to deal with ‘unwanted’ refugees and asylum seekers. Gibney (2008) has described this as ‘the deportation turn’ of European politics. This term has become widely applied in the research field of deportation and signifies the increased utilization of deportation as a migration

1 The six cases of June 2019 were termed ‘test cases’ by the DIS and the Refugee Appeals Board because they

served as a ‘test’ to examine whether it was possible to ‘return’ Syrians to the Damascus region.

2 It is not clearly stated that these cases are ‘spontaneous cases’ but in these three cases no previous status is

referred to. Also, in a news article (posted by the Board in December 2019) they write that they have “ratified the

decision of the DIS to reject asylum” to these three Syrian nationals, not that they have ratified decisions to deny

control tool in Western countries (Gibney 2008, 148). An important argument in relation to this tendency is the one of Kanstroom (2007, 201) who claims that deportation serves as a powerful tool of ‘discretionary social control’.

Others such as Walters, view deportation not only as a technique by which governments exert their sovereign power over bodies, space, and ‘the nation’ but more than that a mechanism by which governments measure and signal their own effectiveness (Walters 2002, 280) (Peutz & De Genova 2010, 11). Furthermore, Walters compares the modern deportation practice with other historical forms of expulsion and emphasizes the forms of governmentality which advance the practice of modern deportation. In the understanding of Walters, deportation is “a

legalized form of expulsion” (Walters 2002, 276) and he asserts that modern forms of

deportation need to be situated within the field of governmentality, not just sovereignty. The argument is that during the 19th century we can speak of a governmentalization of deportation

(ibid., 278). Furthermore, he emphasizes that practices of deportation should be studied in relation to a wider ‘archipelago’ of detention centers, refugee camps and zone d’attente (ibid., 284). I will return to these aspects aspect in section 3.4.

Some scholars have found a need to situate deportation and governmentality in an international perspective, arguing that because states collaborate on issues such as return, it is

relevant to broaden the scope (Lippert 1999) (Scheel & Ratfisch 2014). Although Walters (2002) also takes note of this and situates his analysis of the practice of deportation in an EU perspective where states collaborate on allocating subjects to their ‘proper sovereigns’, he does not focus his analysis on international bodies such as the UNHCR as these other scholars suggest (Walters 2002). In their inquiry of the handbooks on refugee status produced by the UNCHR, Scheel & Ratfisch (2014) argue that the rationale of UNHCR’s refugee protection regime reflects “the governmentality of police, which is concerned with the establishment and

maintenance of the conditions of a specific order”. In this case, the order to be achieved is ‘the

national order of things’ (Scheel & Ratfisch 2014, 938). ‘The governmentality of police’ is a concept developed by Foucault (1991) and is also operationalized by Walters (2002) in his studies on deportation.

Lippert (1999) also connects deportation to governmentality. He stipulates that an international refugee regime was only properly developed in 1951 when the UNHCR was created and he comments on why the ‘refugee discourse’ prevailed instead of one on ‘displaced

persons’ (Lippert 1999, 307). It is in this context that Lippert connects ‘refugeeness’ to governmentality studies. The argument is that “failure of one policy or set of policies is always

linked to attempts to devise or propose programmes that would work better… the identification of failure is thus a central element in governmentality” (Lippert 1999, 303). Walters also

underlines the need to turn our focus to the ‘failures’ involved in governing refugees and asylum seekers to avoid a simplified view on governance as coherent and contingent (Walters 2012, 75-76). This perspective is highly relevant to this thesis and is a central part of applying ‘the toolbox of governmentality’ (Walters 2012).

In connection to the aspect of governmentality, Lippert emphasizes the special ‘technologies’ enabling governmental practices targeting refugees and asylum seekers such as the refugee camp and passports (Lippert 1999, 308, 310). Various scholars also argue that the practice of deportation is constitutive for the legitimacy of citizenship (Hindess 2000; Cruikshank 1999; Anderson et al. 2011). In this context, Walters (2002) makes an important observation in describing the granting of citizenship to ‘the people’ as, in reality, the “acquisition by states of a technical capacity (border controls and so on) to refuse entry to

non-citizens and undesirables“ (Walters 2002, 276). Thus, deportation can be seen as more than a

powerful aspect of immigration policy; it is a necessary consequence of the international order and essential to ‘the modern regime of citizenship’ (ibid., 288).

3.2.Deportation regime(s)?

Considering the inferences made by Scheel & Ratfisch (2014) as well as Lippert (1999) regarding the role of UNHCR as ‘the international police of populations’ and on the collaboration on the practice of deportation between European states (Walters 2002), it is relevant to consider the discussion on whether a ‘unified deportation regime’ exists in the global North. An important contribution to highlighting the existence of such a regime is the work by Peutz and De Genova (2012). According to these scholars, the unified character of such a regime is expressed through the collaboration of EU neighboring member states in a routinely manner especially with sending countries as to “increase their detention and deportation

authority” (Peutz & De Genova 2012, 5). Kanstroom (2017, 614) expresses a similar view,

arguing that deportation has become a vast international system which ”transcends the power

of any single nation state”. However, he conceives that the methods of different deportation

Kanstroom (2017, 614) recognizes that the size and scope of an international regime has become substantial and is expanding.

Peutz & De Genova’s (2012) notion of ‘the deportation regime’ is questioned by Leerkes and Van Houte (2020) as they stipulate that the ‘deportation turn’ (Gibney 2008) was glocalized. This implies that the deportation regimes of different states take different forms and have different consequences depending on how it interacts with national and local contexts (Leerkes & Van Houte 2020, 2). In their research, a project aiming at understanding international variation in ‘post-arrival migration enforcement regimes’ with regard to asylum seekers of six nationalities (amongst them Syrian), they find that it is useful to distinguish between four ideal-typical regimes based on different positions regarding enforcement capacities and enforcement interests (ibid., 11). They argue that Denmark falls within ‘the hampered enforcement regime’ which implies a strong enforcement interest coinciding with weaker enforcement capacities. This is because Denmark has a strict approach to rejected asylum seekers requiring them to stay in so-called ‘departure centers’ and using long maximum (indefinite) detention periods (Leerkes & Van Houte 2020, 15). However, the Danish system lacks a well-developed Assisted Voluntary Return, henceforth AVR, infrastructure as there are stricter conditions for AVR than in other EU member states as well as less financial compensation (ibid., 15).

The observations regarding the Danish ‘post-arrival migration enforcement regime’ are relevant to this research as to situate the case in its context. It is also useful to reflect on the tension between the perspective and arguments of Peutz & De Genova (2012) and Leerkers & Van Houte (2020), and position this research closer to one of these interpretations. As it is evident from the research questions, this study focuses specifically on the Danish case of Syrian refugees and rejected asylum seekers finding themselves struggling to preserve or obtain protection in the Danish system which is currently testing their deportability (De Genova 2002, 438); the possibility of deporting them to Syria. Thereby I position myself closer to the interpretation and focus of Leerkers and Van Houte (2020). This perspective emphasizes that there are many important variations in the approach and results of different states regarding deportation (Leerkes & Van Houte 2020, 2).

3.3. Legal Aspects of the Right of States to ‘Return’ Refugees

Apart from considering the theoretical inquiries on ‘deportation regimes’ it is relevant to examine the legal aspects of return which have also been a concern of numerous scholars. Cwik (2012), for example, highlights that the 1951 Refugee Convention allows states to cease refugee status when a change in circumstances takes place in ‘the country of origin’ which ends the fear of persecution. However, the option is not well-developed in international practice and states are not obliged to follow the UNHCR’s recommended criteria for evaluating whether a fundamental change has occurred. Because the legal requirements are not very clear, confusion exists in the intersection of voluntary and ‘mandated return’ (Cwik 2012, 714). Confusion and ambiguities leave room for interpretation which enables what Gammeltoft-Hansen terms ‘creative legal thinking’ among governments seeking to avoid refugee responsibilities. Thus, time and money is devoted to identifying exceptions, loopholes and possibilities within the legal framework as to minimize their obligations instead of rejecting the legal obligation itself (Gammeltoft-Hansen 2014, 586).

There is some dispute amongst scholars of international law about what the obligations and entitlements of states in relation to return are in practice. For example, Chimni criticizes Hathaway (1997) for stipulating that once a receiving state determines that protection in the country of origin is viable, it is entitled to withdraw refugee status. According to Chimni, this argumentation relies on ‘objectivism’ in the determination of refugee status (Chimni 2004, 60- 61). This is important because objectivism “excludes the refugee through eliminating his or her

voice in the process leading to the decision to deny or terminate protection” (ibid., 61). Lastly,

Chimni observes that whereas the element of subjectivity is celebrated when it means the spontaneous return of the refugee, it is ignored when it results in a decision to stay (ibid., 62). Others, such as Barutciski (1998), argues that the promotion of involuntary repatriation if refugee protection ceases to be necessary is a pragmatic approach that represents “an acceptable

compromise between legitimate State concerns and the protection needs of refugees”. However,

the legitimacy of this compromise relies on ‘sound decisions’ relating to safety in the country of origin. As to ensure ‘a sound decision’ and legitimacy in these cases, Barutciski highlights the importance of non-governmental refugee advocates in establishing whether conditions in the country of origin are ‘safe’ (Barutciski 1998, 254-255). In relation to returning rejected asylum seekers and refugees to their ‘countries of origin’ some scholars have also questioned the legitimacy of AVR-programs regarding their ‘voluntary’ quality. This is because if forced removal is the only alternative in the case of refugees whose protections status has ‘expired’

and asylum seekers who have been rejected, AVR solutions cannot rightfully be labeled ‘voluntary’ (Blitz et. Al 2005; Webber 2011; Black et al. 2011).

3.4. Deportation, Detention and Control

This study is not concerned with detention and ‘departure centers’ per se. However, since residence in one of these centers is often the consequence for rejected asylum seekers who cannot or refuse to return it is an essential component of the ‘governing’ of these individuals in Denmark. Many researchers have devoted their time to examining the links between deportation and detention (Schuster 2005; Bloch & Schuster 2005, 508-509; Wong 2015; Cornelisse 2010; Hasselberg 2016). However, there are not a lot of studies which focus on Denmark. A recent and relevant study from 2018 by the Freedom of Movement Research Collective focuses more specifically on how a special form of control is present in the interconnectedness of detention and deportation in a Danish context. The study examines the measures used in deportation centres and claims that they are responsible for the slow death of rejected asylum seekers who are deprived of their basic rights (FMRC 2018, 48). It is noted that detention and forced deportations are expensive to enforce which might be why Denmark has invested in developing ‘voluntary’ return initiatives even though these have not been very effective (ibid., 18). This is also what Leerkes and Van Houte found when they analysed the efforts and results of detaining and attempting to ‘return’ rejected asylum seekers from Denmark thereby identifying it as a ‘hampered regime’ (Leerkes & Can Houte 2020, 15).

It is relevant to ask what the consequences of this ‘hampered regime’ are and how the state of ‘deportability’ (De Genova 2002, 14-15) affects rejected asylum seekers and refugees. This has been an aspiration of many researchers who have documented migrants’ fear of deportation in different national contexts (Mountz et. al 2002; Willen 2007; Burman 2006; Hasselberg 2016, 30-31). In Denmark, a high rate of rejected asylum seekers living in ‘departure centers’ (udrejsecentre) have been found to show symptoms of anxiety, depression and PTSD especially for those living in the closed camp Ellebæk where multiple suicide attempts have taken place (Schwarz-Nielsen et Al 2009, 56) (Herschend 2020). Recent research has also found evidence that the prolonged periods of waiting for asylum decisions and forced residence in asylum and detention centers in Denmark increases the risk of mental illness (Hvidtfeldt et. Al 2019, 9). Constitutive for the harsh circumstances in the Danish centers are the ‘motivation enhancement measures’ advanced by the previous government as to ‘encourage’ rejected asylum seekers to

comply with AVR-programs but these do not seem to have achieved their purpose (FMRC 2018, 18).

As I have shown in the review of the research field, there is not a lot of literature providing detailed information on deportation and decisions to return refugees and rejected asylum seekers in a Danish context apart from the report produced by the Freedom of Movement Research Collective (2018) and the article on ‘post-arrival enforcement regimes’ by Leerkes and Van Houte (2020). This thesis seeks to add to this field of research by engaging in a case study on the decisions to reject protection to asylum seekers from Syria and ‘return’ them to the Damascus region and the possible consequences of such decisions. In the next chapter, I will comment on the implications, advantages, and shortcomings of choosing such an approach.

4. Research Design

4.1. Case-based Research

The research design of this thesis is based. Case-based research refers to the classic case-study design which is a case-study in considerable depth of a single case or a few cases (Perri 6 & Bellamy 2012, 103-104). In this study, the case is the process and practice of the Danish state actors and the Refugee Appeals Boards in assessing whether to provide asylum protection for the nine Syrian nationals and the possibility of returning them to Syria. Due to the specific and deep focus of this research design, it cannot only be used in establishing the presence of causal processes but also in teasing out how causal processes work (ibid., 103-104). This aligns well with the aim of the thesis which is to identify the explanations and justifications for deciding whether to provide asylum protection to the nine Syrian nationals and to pinpoint the strategies and underlying logic of the Ministry and the agencies facilitating the decisions made in the cases. Achieving this aim primarily entails a qualitative approach but answering the first research question and part of the second one requires presenting and organizing the data. This is carried out through content analysis and coding which is usually associated with quantitative research (Bryman 2012, 304). However, coding is also operationalized in qualitative research such as grounded theory and qualitative content analysis and in these research strategies, there are no preconceived standardized codes; the researcher’s interpretations shape his or her emergent codes (ibid., 568). My approach to coding is closer to this approach.

The research conducted in this thesis is predominantly deductive in nature but as emphasized by Bryman, these distinctions are not as clear-cut as often presented in academia (Bryman 2012, 26). The motivation and idea behind this paper started with a question as I was confronted with the fact that the government succeeded in pushing for a new practice on the evaluation of asylum claims made by Syrian nationals. Reading through the cases started an accumulation of questions: What are the factors used in establishing Damascus as a ‘safe’ place for some Syrians and not for others and how is this legitimized? In these terms, one can argue that the initial approach was more inductive as my motivation was driven by empirical material. However, I decided to approach this material through discourse analysis and to situate my analysis in Walters’ (2002; 2012) inquiry on deportation in connection to governmentality. Thus, the research tends toward being more theoretically driven than data-driven (Braun & Clarke 2006, 12). I am not testing a hypothesis per se but I am guided by a theoretical framework thus making the approach more deductive. I will account for the choice of the methods and theoretical framework in the methodology chapter.

4.2. Trade-offs, Validity & Reliability

In relation to the choice of research-design, some trade-offs must be addressed. Choosing a case-based design should always involve considering the question of external validity in terms of generalizability as well as accounting for the choice of the case in question. The external validity of this thesis is of course limited due to the choice of research design which constrains the opportunities of comparison over time and space; instead it allows the researcher to do an in-depth investigation of the chosen case which strengthens the internal validity as it provides for high context-sensitivity (Bryman 2012, 47, 390). This can be regarded as a trade-off between internal and external validity. The qualities of this research design align well with the aim of the thesis regarding creating detailed knowledge about the assessment of asylum claims made by Syrian nationals and the justifications for the decisions made in their cases. Regarding the material of this case there are only nine cases available in total which means that this study takes all outcomes of the relevant cases into consideration and thus, the study is not as limited in terms of external validity as qualitative studies usually are when considering the amount of available material.

In terms of external reliability, the empirical material of this study, the cases, reports and news articles, are all available online and in that sense the study could easily be repeated. However, it cannot be assured that the same results would emerge as the method chosen to

analyze the material is discourse analysis which involves a certain amount of interpretation (Torfing 2004, 1; 27). Internal reliability in qualitative research on the other hand, can be strengthened by testing if there is consistency in what several researchers observe (Bryman 2012, 390) but as I am the only researcher working on this project this has not been possible. As a measure to optimize the internal validity and reliability of the study however, I read through all the articles, reports and cases multiple times and when making theoretical inferences I returned to the actual material to read the statements in their context once again as to ensure that I did not rely on or get caught up in my notes and my first interpretations.

4.3. Contribution

A case can provide new insight into a field in different ways and one of them is by representing an extreme or unique case (ibid., 70). I argue that in an EU perspective, the decision not to provide asylum protection for the three Syrian nationals in Denmark can be interpreted as an extreme (or unique) case in relation to the treatment of Syrian nationals seeking protection in other EU member-states and in relation to the previous years of asylum protection practice regarding Syrians (ECRE 2019c). However, in a Danish perspective, the case can be interpreted as quite the opposite; as an exemplifying case considering the strict circumstances for asylum seekers and refugees in Denmark established step by step by restrictive immigration and asylum policies over the last two decades (Wong 2015, 76) (UIM 2019h). The two-fold representation of the case allows us to make inferences that inform research on extreme cases of restrictive asylum policies in an EU context and at the same time makes it possible to dig deep into this specific case which serves as an example of Denmark’s development towards more and more restrictive immigration and asylum policies formed through the numerous amendments of the Alien’s Act (Fancony 2017). The exemplifying quality of the case provides us with the opportunity of teasing out the assumptions of the Ministry and the agencies about asylum protection for Syrian nationals. Thereby, this thesis has the potential to deepen the understanding of how decisions to ‘return’ this specific group of nationals (Syrians) are made and how it is justified in a Danish context.

In a lot of literature, Denmark is referred to as having developed some of the strictest immigration and deportation policies in Europe but despite this, very little research has focused on Denmark specifically or considerably in depth (Wong 2015, 76) (Gammeltoft-Hansen & Tan 2017, 38). Leerkes and Van Houte also note that knowledge about policies concerning ‘post-arrival migration enforcement’ in Denmark and Norway is not very well-documented and

it is significantly harder to find information on Denmark than on Norway (Leerkes & Van Houte 2020, 8). Based on these statements, I argue that this study contributes to filling this gap, even though it might only have the capacity to fill a small corner due to the limitations of a master thesis.

4.4. Data and Delimitations

The empirical data engaged with in the discourse analysis consists of the six cases of Syrians granted residence permits through their appeal at the Refugee Appeals Board in June 2019 and the three cases of the Syrian nationals whose applications for asylum were rejected in December 2019. To broaden the scope and to capture the attitude towards asylum protection and ‘return’ of Syrian nationals, relevant material produced by the Ministry of Immigration and Integration as well as the DIS and the Refugee Appeals Board is also examined. Because there is very little material focusing specifically on the decision to ‘return’ the three Syrian nationals (apart from the cases), I include some material commenting on asylum protection and return of refugees in general produced by the Ministry, the DIS and the Board. This material includes news announcements, reports and the like and serves to provide a context to the cases. As to delimit the amount of this material, the time frame is set from the end of 2018 till the beginning of 2020 and only material focusing directly on asylum protection and return is included. The reason for choosing this specific time frame is that at the end of 2018 the Finance bill of 2019 was negotiated and this bill has had a vital role in the changed approach to the assessment of asylum claims and regarding the increased focus on ‘return’ (UIM 2018a). Thus, material discussing this bill is highly relevant for the analysis of the context in which the cases examined in this study were assessed.

It should be noted that it is beyond the scope of this study to analyze deportation from a historical perspective as proposed by Walters (2002; 2012). Additionally, the role of the media and opinions of Danish citizens and denizens are not included in the analysis as it does not align with the aim of this thesis; the object of analysis is Danish state actors and the Refugee Appeals Board involved in asylum processes which might lead to deportation. This also means that the experiences of the refugees and asylum seekers themselves are not considered. Furthermore, this study delimits itself by focusing on deportation on a national level (albeit, in an EU perspective) which means that the role of international bodies such as the UNHCR is not considered.

5. Methodology

5.1. Content Analysis and Coding

The purpose of applying content analysis and coding in this study is to establish the similarities and differences between the cases and to provide an overview of factors significant in the assessment of the cases. This makes the discussion of the cases easier to follow and more transparent. Something one should be aware of when conducting content analysis is that even though coding might seem ‘objective’ it is almost impossible to produce a coding schedule that does not entail interpretation (Bryman 2012, 306). The process of coding in this study is carried out according to the factors facilitating the decisions highlighted by the Board in the cases as a measure to make the process as objective as possible; as such, the categories were established after reading through the data. These factors are: 1) Sex and legal status 2) Date of assessment 3) Whether the appellant is considered personally targeted by the Syrian regime 3) Whether the appellant has family members considered targeted by the Syrian regime 4) Whether the appellant has resided in an area controlled by rebellious forces (such as the Free Syrian Army) before leaving 6) Whether the appellant has returned to Syria after the initial flight. A schedule providing information on the cases regarding all these factors is available in Appendix 1. Answering research question 2 concerning how asylum protection and return is framed in the material, also involves an examination of the actual content, structure and meaning of the material. This resembles a content analysis which can be regarded as the first step of discourse analysis (Bryman 2011, 538). The next step is to identify the discourses and inspect the way in which they are organized. I elaborate on how this will be done in the next section.

5.2.Discourse Analysis as Theory and Method

5.2.1. Choice of Theoretical Framework

With discourse analysis, it is possible to examine the way sentences combine to create meaning, coherence and accomplish purposes (Gee & Handford 2012, 1) which makes it an appropriate method to reach the aims of this study. Another reason that it is relevant is the emphasis on context in the study of discourse; be it context of society, culture, history, politics, identity formations, power or anything else which language is constitutive of and in turn makes language meaningful in certain ways, thus enabling it to accomplish specific purposes (ibid.,

5). However, discourse analysis is a vast methodological field to which there are many approaches and which scholars have interpreted and employed in different ways. Because of this, it is essential to specify what meaning is ascribed to the various concepts used when analyzing discourses. I have chosen to apply Laclau and Mouffe’s (1985) discourse theory as my main framework of analysis since it is suitable for analyzing discourses with a political focus. Furthermore, Laclau and Mouffe’s (1985) perception of social practices as fully discursive aligns well with the governmentality aspect applied to the case (Jørgensen & Phillips 2011, 35). This conception allows us to interpret governmental practices as part of the discursive structure.

Another important reason for choosing the framework of Laclau and Mouffe (1985) is that they insist on the internal relation between power and discourse (Torfing 2004 7, 9) and their understanding of ‘power’ as that which produces the social thus emphasizing the productive aspects of power (Jørgensen & Phillips 2011, 37). This understanding of power aligns with Foucault’s (1991) and Walters’ (2012) conception of ‘the microphysics of power’ which is a relevant concept in the ‘toolbox’ of governmentality that I operationalize in the analysis. This conception however, contrasts with the conception of power as a tool of dominance and repression as highlighted by Fairclough and other advocates for critical discourse analysis, henceforth CDA (Torfing 2004, 7). In my analysis, I conceive power as a productive rather than repressive force and social practices as fully discursive. I also look to a modification of Laclau and Mouffe’s theory (1985) made by Jørgensen and Phillips (2002) because it offers adjustments which makes the theory more applicable.

It should be noted that the ontological and epistemological assumptions behind the research method of this study places it within the position of constructionism (also referred to as social constructivism) which asserts that social phenomena and their meanings are continually being accomplished by social actors. This implies that social phenomena and categories are not only produced through social interaction but that they are in a constant state of revision (Bryman 2012, 33). However, it is important to clarify, as emphasized by Laclau and Mouffe (1985), that perceiving all objects as constituted as an object of discourse does not imply that there is no world external to thought. Thus, engaging in this type of discourse analysis highlights the statement that objects cannot constitute themselves as objects outside a discursive condition of emergence (Laclau and Mouffe 1985, 108). Or in other words: “(…) nothing follows from the bare existence of matter. Matter does not carry the means of its own representation” (Torfing 2004, 18).

5.2.2. The Discourse Theory of Laclau & Mouffe

Laclau and Mouffe’s (1985) discourse theory is a poststructuralist theory constructed through combining and revising two major theoretical traditions: Marxism and structuralism. In this theory, the whole social field is understood as a web of processes in which meaning is created (Jørgensen & Phillips 2002, 25). The discourse theory involves a number of key concepts that need to be defined before their approach can be efficiently discussed (Laclau & Mouffe 1985, 105):

1. Discourse signifies the structured totality resulting from articulatory practice.

2. Articulation refers to any practice establishing a relation among elements such that their identity is modified as a result of the articulatory practice.

3. Elements indicate ‘signs’ that do not acquire detailed meaning until they are inserted in a particular discourse. Thus, elements also refer to any difference that is not discursively articulated.

4. Moments: Refer to the differential positions of ‘signs’ when they appear articulated within a discourse. In an established discourse, elements are reduced to moments. Using these concepts, we can describe discourse as an established totality in which various ‘signs’ are fixed as ‘moments’ through their relations to other ‘signs’ (elements). It can be useful to think of the signs fixed in the moment as the way that a fishing net is constructed (Jørgensen & Phillips 2011, 25). The fixation is possible by excluding all other possible meanings that the ‘signs’ could have had and through the sedimentation of the ‘signs’ in a particular relation to each other, a unified system of meaning can be created. This is also defined as a ‘closure’ or a temporary stop in the possible variations of meaning established by the discourse. According to Laclau and Mouffe, this closure is never definitive (ibid., 28-29).

An important component in the establishment of a discourse and temporary ‘closure’ in Laclau and Mouffe’s (1985) theory is ‘the nodal point’ (Laclau & Mouffe 1985, 112). Nodal points can be described as privileged but essentially empty signs that a discourse is organized around. Thus, they are, like elements, ‘floating signifiers’; they only acquire meaning by being positioned in relation to other elements fixed as ‘moments’ in the discourse. When a ‘floating signifier’ becomes established as a nodal point in a specific discourse it refers to a point of crystallization of meaning around which the discourse is organized. By itself, a ‘floating signifier’ is part of the ongoing struggle between different discourses to fix the meaning of

important signs (Jørgensen & Phillips 2011, 28). In the analysis, I identify the nodal points that the discourses, present in the material, are organized around and struggle to define. I also pinpoint the elements fixed as ‘moments’ which together form an established totality, also referred to as ‘discourse’. This is accomplished through a process that involves reading the material thoroughly and several times while constantly placing it in and broadening the context. I have already provided an overview of the Danish asylum system, the Ministry, the agencies and the central policies in chapter two which presents a simplified version of the context that the analysis draws on.

A relevant critique of Laclau and Mouffe’s work (1985), formulated by Fairclough and Chouliaraki (1999) amongst others, rests on the claim that Laclau and Mouffe (1985) overlook the perspective that not all individuals and groups have “equal possibilities for rearticulating

elements in new ways and thus for creating change” (Jørgensen & Phillips 2011, 54). However,

Laclau and Mouffe (1985) do take this into account, as they distinguish between the ‘objective’ and the ‘political’ to emphasize that although everything is contingent, there is always ‘an objective field of sedimented discourse’. This means that there exists a long sequence of social arrangements that most people take for granted and therefore, they can be extremely challenging to change. Furthermore, Laclau and Mouffe (1985) recognize that not all actors have equal possibilities for doing and saying things in new ways and for having their re-articulations accepted (ibid., 55).

A way to sharpen the perspective of Laclau and Mouffe suggested by Jørgensen & Phillips (2011) concerns their notion of ‘the field of discursivity’ which is the term for additional meaning, that is, everything that is excluded from the specific discourse. They note that it is unclear whether the concept refers to “any meaning outside the specific discourse, or if it more narrowly refers only to potentially competing systems of meaning“ (Jørgensen and Phillips 2011, 55-56) so they suggest a reformulation. In this formulation, ‘the field of discursivity’ refers to ”any actual or potential meaning outside the specific discourse” and the concept ‘the order of discourse’ denotes “a social space in which different discourses partly cover the same

terrain which they compete to fill with meaning each in their own particular way.“ (ibid., 56). The term ‘order of discourse’ is a concept employed in CDA with a slightly different meaning from the suggestion of Jørgensen & Phillips (2011). The definition used here signifies a potential or actual area of discursive conflict and removes any confusion regarding what ‘the order of discourse’ includes or excludes. Having defined ‘the order of discourse’, we can say

that two other central concepts of Laclau and Mouffe (1985), ‘antagonism’ and ‘hegemony’, belongs to this level of analysis. ‘Antagonism’ is open conflict between the different discourses in a particular order of discourse, and ‘hegemony’ is the dissolution of the conflict through a shift of the boundaries between the discourses (ibid., 56). These concepts guide the analysis in terms of understanding the relation between the different discourses that I identify and help conceptualize any type of discursive struggles central to the justification of the decisions in the cases.

5.3.The Toolbox of Governmentality 5.3.1. What is governmentality?

To conceptualize how the discourses identified in the material are made possible on a larger scale, the ‘toolbox of governmentality’ is operationalized. A scholar who has emphasized the use of this ‘analytical toolbox’ in analyzing the theoretical aspects of deportation is Walters (Walters 2012, 2). Walters describes it as “a cluster of concepts that can be used to enhance

the think-ability and criticize-ability of past and present forms of governance“ (ibid., 2). As the

approach of Walters draws on governmentality in Foucault’s understanding and as Foucault employs the term in 3 distinct ways, it is important to define how governmentality is understood and applied in this study. I apply governmentality as defined by Foucault:

‘(…) the ensemble formed by institutions, procedures, analyses and reflections, calculations, and tactics that allow the exercise of this very specific, albeit very complex, power that has the population as its target, political economy as its major form of knowledge, and apparatuses of security as its essential technical instrument’. (Walters 2012, 30) (Foucault 2007, 108).

Foucault mainly used governmentality as a framework to explore the way in which the modern state could be defined and deployed as a matrix of government but the analysis of governmentality can be conducted on many scales and levels (Walters 2012, 39). The level of analysis in this study is the Ministry and the agencies managing asylum protection and deportation in Denmark. This means that I am primarily operating on a on a (national) state level. However, as emphasized earlier, the method of this thesis requires an emphasis on context in order to make valid claims. This is also important in terms of Foucault’s notion of the

pervasive which means that there is no power in general. Conversely, there exists specific ‘dispositions’, ‘maneuvers’, ‘tactics’, ‘techniques’, ‘functionings’ which together constitute ‘the microphysics of power’. According to Walters (2012, 14), it is the researcher’s task to “carefully map and distinguish these“. In the analysis, I operate on a micro-level while engaging in discourse analysis. The governmentality aspect brings the insights reached at this level to macro-level to shed light on the governmental aspects of the discourses. This allows us to understand their implications on a larger scale and is done by mapping the relevant apparatuses, techniques, technologies, and knowledges of government thus illustrating how governmental power works.

5.3.2. The Governmentalization of Deportation

I employ the term ‘deportation’ in the same understanding as Walters: to refer to the removal of aliens (and refugees) by state power from the territory of that state either ‘voluntarily’, under threat of force or forcibly (Walters 2002, 268). According to Walters (2002, 267, 276), deportation must be studied within a wider field of historical practices of expulsion in the light of which deportation represents a ‘legalized form of expulsion’ its legitimacy resting upon ”its

administrative nature, and the observance of national and international laws and norms“.

Walters (2002) contends that modern deportation lies at the intersection of the logics of sovereignty and government and to understand this, we must make a clear distinction between governmental power and sovereign power. In the understanding of Walters based on his interpretation of Foucault’s writings, governmentality marks the point at which political power comes to be concerned with the wealth, health, welfare, and prosperity of the population. In relation to this, we might observe that sovereign power involves the exercise of authority over the subjects of a state whereas government is marked by its concern to improve the potencies of the population (ibid., 278).

An important point made by Walters in his analysis of the genealogy of deportation is that during the 19th century, we can speak of a governmentalization of deportation. What is meant

by this is that deportation is being used by governments as a tool to defend and promote the welfare of a population defined in national terms (Walters 2002, 278-279). Thus, governmentality is closely connected to the art of biopolitics which denotes measures aiming at ensuring, sustaining and multiplying the grouped object Foucault labels ‘population’. In accordance with Foucault, Walters stresses that population should not be regarded as a ‘natural entity’ but rather as “the effect of particular forms of knowledge and the invention of new

statistical techniques, sciences like demography, state policies on reproduction, health care, etc.“ which are all essential techniques of liberal governmentality (Walters 2012, 15-16).

5.3.3. Enabling “raison d’état”

Foucault’s history of the art of government emphasizes that making the logics of the modern state (raison d’état) possible involved “setting up two major assemblages of political

technology”. These two were 1) A military-diplomatic technology that consists in securing and

developing the state’s forces through a system of alliances and the organizing of an armed apparatus and 2) The technology of police (Walters 2012, 27). The idea of ‘the technology of police’ is one of the concepts that has been developed in studies on governmentality and deportation and concerns the establishment and maintenance of a specific (national) order (Scheel & Ratfisch 2014, 938). For example, Walters observes that deportation can be interpreted as one key element in the ‘international police of aliens’. As Walters suggests, it is appropriate to apply concepts such as ‘apparatus’, ‘sovereign power’ as opposed to ‘governmental power’, ‘the microphysics of power’, ‘techniques of governance’, ‘the technology of police’ and ‘biopolitics’ as tools in analyzing governmental practices such as deportation. Thus, we can draw attention to ”the conduct of conduct and especially the

techniques and knowledges that underpin attempts to govern the conduct of selves and others in diverse settings“ (Walters 2012, 39).

An important question however, is the question of definitions. Especially the concept ‘apparatus’ has been widely interpreted and employed in many ways. As a measure of clarification, Walters notes that an apparatus is better understood as “a relatively durable

network of heterogeneous elements: discourses, laws, architectures, institutions, administrative practices and so on” (Walters 2012, 36). In my analysis, I stick to this definition. I have already

defined sovereign power as opposed to governmental power, biopolitics and the microphysics of power with the assistance of Walters and I employ the concepts or ‘tools’ in his understanding. Regarding different ‘techniques’ of governance, these are for example statistical techniques, sciences like demography, state policies on reproduction and health care and the like (ibid., 15-16). In chapter 8, I focus on mapping these apparatuses, discourses, institutions, techniques, and technologies of governing relevant to the case and relate them to concepts such as biopolitics and the microphysics of power.

6. Overview and Analysis of the empirical material

6.1. The Main Similarities and Differences between the Cases

Most of the empirical material is only available in Danish. Therefore, some quotes are translated to English thus making the analysis easier to follow for non-Danish speakers. I provide the Danish wording in footnotes if a quote or a specific word is central to the analysis or if the words are difficult to translate due to the specific Danish context.

6.1.1. The Six ‘Test Cases’

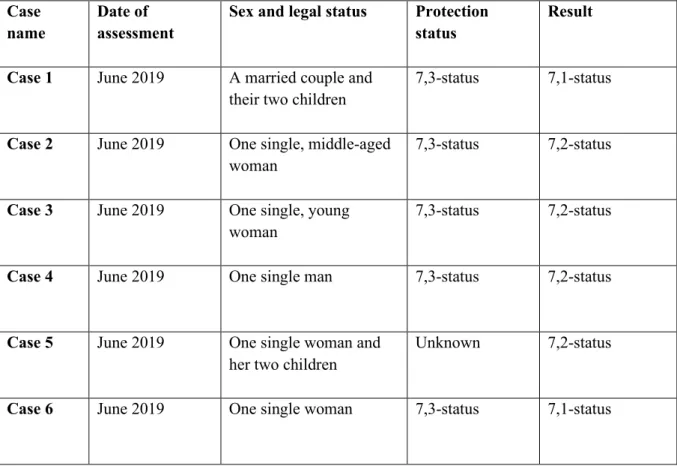

Table 1: Schedule of the Overturned Cases (see detailed schedule in Appendix 1) Case

name Date of assessment Sex and legal status Protection status Result

Case 1 June 2019 A married couple and

their two children 7,3-status 7,1-status

Case 2 June 2019 One single, middle-aged

woman 7,3-status 7,2-status

Case 3 June 2019 One single, young

woman 7,3-status 7,2-status

Case 4 June 2019 One single man 7,3-status 7,2-status

Case 5 June 2019 One single woman and

her two children Unknown 7,2-status

Case 6 June 2019 One single woman 7,3-status 7,1-status

As evident from the schedule in table 1, in all the cases which involved individuals with 7,3-status, the appellants were granted a higher status than they held before the assessment by the Refugee Appeals Board; 7,1-status (cases 1 and 6) or 7,2-status (cases 2, 3, 4). This is notable because it points to the circumstance that some of the appellants might initially have been granted a lower status by the DIS than their situation would in fact allow them to attain.

Regarding case 1, the decision to grant 7,1-status is founded on events which took place in Denmark. The family has been exposed in the Danish newspaper Berlingske and in some Arabic news media and the Board assessed that they might be considered opponents to the Syrian regime because of this (case 1). In case 2, the middle-aged woman was granted 7,2 status because she left her job in the public sector without permission from the authorities and the Board assessed that the appellant could risk imprisonment because of this (case 2). In case 3 and 5 it is established that “the circumstances in Damascus are no longer of such character

that there is reason to assume that anyone will be in risk of assault at odds with article 3 of ECHR due to their presence in the area” by referring to the COI-report on Syria of 2019.

Whether this should be regarded as a temporary or a more stable situation, the Board did not give their opinion on. However, both cases concluded by granting the appellants 7,2-status due to very similar factors: the appellants are both single women, they have close family members who have attained asylum protection in Denmark (case 3) or other countries (case 5) and they both resided in areas controlled by rebellion groups before their flight (case 3 and 5).

In the other cases, the general situation in the Damascus region was not mentioned as the Board directly pointed to reasons for why the appellants should obtain either 7,2 or 7,1-status except for case 4, in which the Board’s assessment seems a bit ambivalent because the appellant provided new information regarding a personal conflict with the authorities. The Board was informed that the appellant is hard of hearing and has cognitive challenges and they contended that this should be taken into consideration; the result was 7,2-status. In case 6, the appellant was granted 7,1 status because she has married a man from Aleppo who has attained asylum protection in Sweden due to detainment and torture by the Syrian regime. The Board contended that this might put the appellant at risk of being detained and assaulted upon return according to the COI-report on Syria of 2019 which states that family members to persons regarded as ‘opponents’ to the Syrian regime might be at special risk (case 6) (DIS 2019).

6.1.2. The Three Cases of December 2019

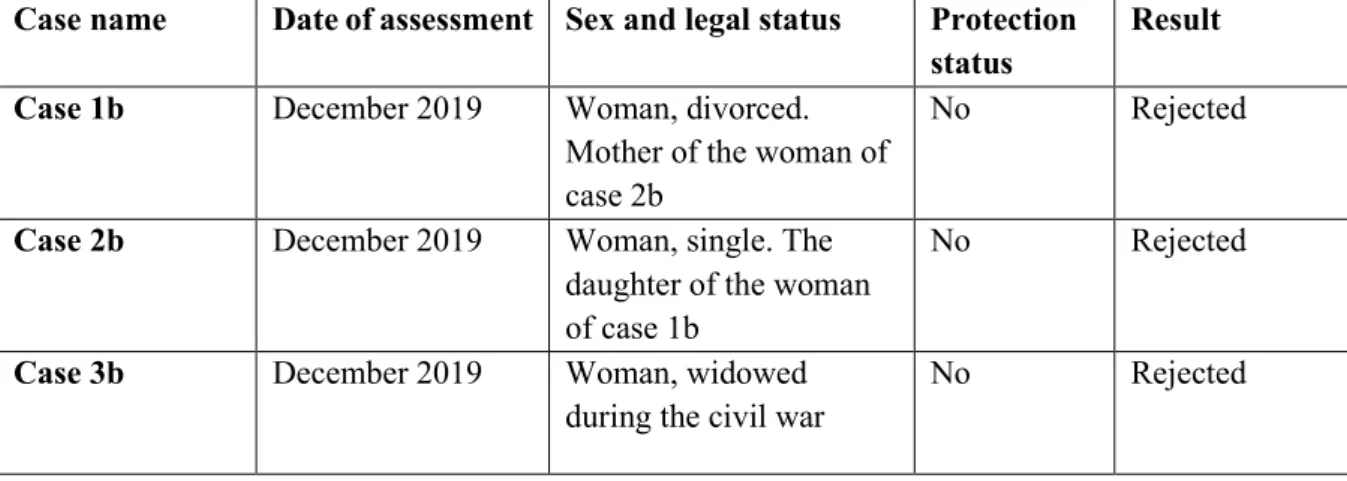

Table 2: Schedule of the Rejected Cases (see detailed schedule in Appendix 1) Case name Date of assessment Sex and legal status Protection

status Result

Case 1b December 2019 Woman, divorced.

Mother of the woman of case 2b

No Rejected

Case 2b December 2019 Woman, single. The

daughter of the woman of case 1b

No Rejected

Case 3b December 2019 Woman, widowed

during the civil war No Rejected

The rejected cases presented in the schedule of table 1 all concern Syrian, Sunni-Muslim women from the Damascus region who were seeking asylum protection in Denmark. This means that these cases did not involve the question of revoking a residence permit but rather of whether asylum should be granted to the applicants (‘spontaneous cases’). It is stressed that none of these women were members of any political or religious organizations and have not been politically active. All of them referred to the general situation in Syria as their main asylum motive. In all the cases, the Board referred to the COI-report on Syria from February 2019 to support the claim that the security situation of Damascus has improved significantly since the Syrian authorities obtained full control over the area in May 2018 (cases 1b, 2b, and 3b). However, the Board also referred to reports produced by authorities in the Netherlands (Ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken) and Sweden (Migrationsverket) to establish that the general situation in Syria is still very unstable. Nonetheless, the Board weighed the situation in the Damascus province against the details of the applicants and the criteria of obtaining protection status as well as the practice from the European Court of Human Rights on the area of use of the ECHR article 3 in such situations. The conclusion was, as in case 3 and 5, that

“there is no reason to assume that anyone will be in risk of assault at odds with article 3 of the ECHR just by being present in the area” (cases 1b, 2b and 3b). In these three cases however, it

was stressed that the situation has been improving for a longer period of time (ibid.). Since the Board did not establish any individual factors but only ‘socio-economic circumstances’ which do not “substantiate a claim to asylum protection” (case 3b), the decision of the DIS was ratified in all three cases.

6.1.3. Comparison of the Decisions of the Refugee Appeals Board in the Cases

In the schedule available in Appendix 1, I have provided an overview of the cases with detailed information. Looking at the schedule, it can be established that in the cases in which asylum protection was denied, the appellants had all entered Syria after their initial flight. The fact that the appellants had returned voluntarily after their flight and that they were not questioned by the authorities during this stay in Syria was used as an argument for why it will be safe for them to return now. Their stays took place in 2014 (cases 1b and 2b) and in 2013 and 2014 (case 3b). Regarding case 1b and 2b, their family member who was wanted by the authorities (case 1b: husband, case 2b: father) chose to return to Syria in 2017. This was also used as an argument for why the appellants would not be at risk of assault upon their return. In some of the cases (cases 3, 4, 5 & 6) in which the decisions to revoke the residence permits were overturned, the Board emphasized that being a family member of a person who the Syrian authorities regards as an ‘opponent’ to the regime also puts a person in risk of assault upon return. This was disregarded in case 3b as well as in cases 1b and 2b because of their voluntary visit to Syria in 2013 and 2014. In case 1b and 2b, the return of the father/ husband to Syria in 2017 was also considered as indicating that these two women can be ‘returned’.

Another important factor which was highlighted in some cases, is that the Syrian authorities’ assessment of who poses a threat to the regime is characterized by arbitrariness and is unpredictable (cases 3, 4, 5, 6). In two of the cases, the Board contended that this gives reason to be cautious in the assessment and to grant the applicant ‘the benefit of the doubt’ (cases 3 & 4). However, in case 3b this was not considered a decisive factor. The appellant’s brother attained 7,1-status in Denmark because he rejected to serve in the Syrian military (case 3b). Thus, the appellant has a family member who would be regarded as an opponent of the regime since he is a military defector (DIS 2019, 26). In this case, the Board did not mention that family members of supposed ‘opponents’ to the regime might be at special risk, nor did they mention anything about the arbitrariness of the assessment of who poses a threat to the regime (case 3b). Furthermore, the fact that the appellant is a single woman with no family or any place to stay in Damascus was disregarded by the Board as ‘socio-economic circumstances’ in case 3b whereas in case 3 and 5, these factors were part of the overall assessment of the case leading to the conclusion that the appellants will be ‘at actual risk’3 of being detained and questioned if

3In Danish: “(…) der er en reel risiko for, at hun ved en tilbagevenden til Syrien vil blive tilbageholdt og afhørt”