Basic Level Independent Project in the Major Subject:

(15 credits)

The Effectiveness of Incidental

Vocabulary Acquisition on L2 Learners

Incidental inlärning av vokabulär vid läsning på engelska som andraspråk

Philip Brooks

Anton Sundin

Master of Arts/Science in Examiner: Maria Graziano Education, 300 Credits Supervisor: Chrysogonus Siddha Malilang

Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to review existing research in the field of incidental vocabulary acquisition (the concept of learning new words when the focus of learning is on something different) in relation to literature and literary texts, with the aim to examine its efficiency as a method when it comes to vocabulary acquisition for EFL/ESL learners. The approach to this study was to search relevant databases to gather the sources, summarize their most important findings before comparing and contrasting them to one another. Results indicated that reading for content may provide learners with opportunities to acquire vocabulary incidentally, although it can only be considered efficient if complemented with intentional, explicit instruction.

Furthermore, the results suggest that decay of knowledge is a key factor when examining the effectiveness of incidental vocabulary acquisition as well as the apparent theme that learners are more likely to acquire previously unknown vocabulary when they are allowed to choose what to read. Lastly, the core content of the Swedish National Curriculum includes a lot of literature, which means that the potential to work with incidental vocabulary acquisition in the classroom increases. However, there may not be enough time in the classroom for this, making

encouragement for students to read outside the classroom important in order for incidental vocabulary to be effective.

Individual contributions

We hereby certify that all parts of this essay reflect the equal participation of both signatories below:

The parts we refer to are as follows: • Planning

• Research question selection

• Article searches and decisions pertaining to the outline of the essay • Presentation of findings, discussion, and conclusion

Authenticated by:

Philip Brooks Anton Sundin

Table of contents

Content Page number

1. Introduction 5

2. Aim and Research Question 9

3. Method 10

3.1. Search Delineations 10

3.2. Inclusion Criteria 10

3.3. Exclusion Criteria 11

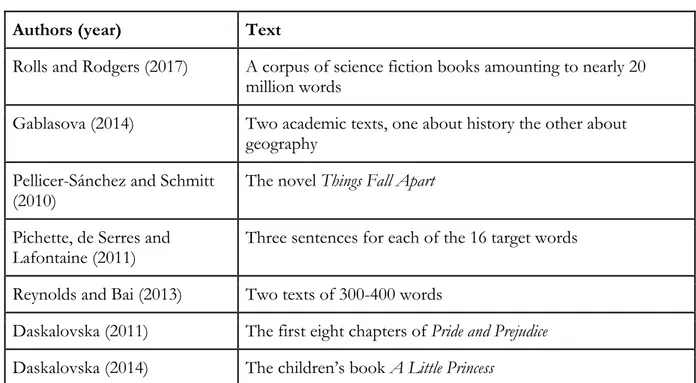

Table 1. Utilised text types 11

4. Results 12

4.1. The efficiency of incidental vocabulary acquisition 12 4.2. Similarities and differences in the selected studies 15

5. Discussion 18

6. Conclusion 22

1. Introduction

The notion that vocabulary has an important role to play in the acquisition of the English language is a claim that was established a long time ago. O’Keeffe (2012) made a reference to Wilkens, who in as early as 1972 commented that communication is made difficult through lack of grammatical knowledge, while a lack of vocabulary makes it impossible (p. 242). Ahmad (2012) argues that vocabulary is an essential part for ESL learners’ progression toward becoming more proficient in their second language, and that vocabulary is a tool in order to strengthen both written and spoken language skills. Furthermore, Gablasova (2014) claims that a large vocabulary is often a contributing factor to a learner’s overall success in school. Moreover, the Swedish National Curriculum (Skolverket, 2011) states that the English subject should provide students with the opportunity to develop their communicative skills through the usage of the English language in different contexts and through these contexts get the opportunity to exercise reception, and production and interaction in different forms. In order for learners to

accommodate tasks of this nature, there is an argument to be made that providing students with tools to acquire and expand their vocabulary will be a subject matter of great importance. These tools could include reading materials such as graded readers and Young Adult fiction (YA).

Since this paper will apply the research found to Swedish educational contexts, it is of relevance to make a distinction of the terms English as a foreign language (EFL) and English as a second language (ESL), and how this paper will apply itself to these terms. EFL will in this instance be in reference to places where English is not commonly regarded as a second language, and ESL will be in regard to the acquisition of the language as a second language beside one’s native language. While the definitions of the terms differ slightly, it is generally admitted that researchers often use the terms interchangeably. Throughout this paper the usage of L2 will be used as an umbrella term for both EFL and ESL. Additionally, how a learner “acquires” vocabulary is another term that will be frequently visited throughout these pages. Krashen and Terrell (1983) defined the term acquiring as something that occurs when the availability to develop a language arises in natural or communicative situations, or as the authors put it, “picking it up” (p. 18). This definition is the one this paper will refer to when acquisition of vocabulary is mentioned or discussed.

The debate regarding which way an L2 learner most efficiently acquires vocabulary has offered different alternatives, one such alternative being acquiring lexical knowledge through incidental learning. Loewen (2015) describes incidental learning as learning that takes place when the focus of the task is elsewhere and uses meaning-focused interaction and reading for content as

examples as to how incidental vocabulary learning can take place. Loewen further claims that incidental learning is one of two separations that can be made when discussing vocabulary learning, the other being intentional learning, in which the goal of the task is for students to acquire or expand their vocabulary (p. 100).

Similarly, Sok (2014) explains that the research on incidental learning in terms of vocabulary acquisition is in regard to words that appear in an everyday context, claiming incidental learning is often related to phrases such as learning as a “by-product” or “side-effect”. However, the author claims that there is dissidence regarding its definition, more specifically what is to be considered incidental learning, suggesting that this confusion has caused previous research in this field to be the subject of criticism. Furthermore, Rolls and Rogers (2017) argue that there are limitations to how much explicit instruction that can be taught in the classroom. As such, incidental learning through extensive reading can be an exceptional addition to the classroom activities. This claim is in turn echoed by Loewen (2015) who states that time spent on vocabulary in the classroom is limited and that providing the possibility for students to incidentally learn vocabulary through large amounts of input outside the classroom could be beneficial (p. 109).

Incidental vocabulary learning has been the subject of research for some time, with several important studies paving the way for the field to progress. In fact, there are several older studies suggesting that incidental vocabulary acquisition could be an effective path to expanding L2 learner lexical knowledge (Cho & Krashen 1994; Day, Omura & Hiramatsu 1991; Horst, Cobb & Meara 1998; Pitts, White & Krashen 1989;). These studies, and many more in both L1 and L2 contexts show that there is a link between vocabulary acquisition and reading. One of the

landmark studies in this field of research was conducted by Saragi, Nation and Meister (1978) and has been commonly referred to as the “Clockwork Orange” study. The essence in this study was to instruct students to read a book for its content and then test the students on how many words they had learned. The reasoning behind using the book A Clockwork Orange was that it contained words that students could not possibly have known previously. This study has inspired the methodology in more recent research on the subject and can be said to have laid the foundation

for the field to expand, with a number of replication studies being made in the decade following its publication.

Moreover, the core content of the Swedish National Curriculum describes different forms of literature that students will encounter throughout their education in the subject of English, ranging from different forms of fiction of different genres to scientific articles and texts depending on the course. Bordag and Rogahn (2018) suggests that incidental acquisition of vocabulary through extensive reading is a vital tool for students in order to improve in this area of their language development. Further, Lightbown and Spada (2017) cite Marcella Hu and Paul Nation who found that the requirement to read a text without having to look up words in order to create context is to know 95% of the words in the text. In addition to this, the authors note that the understanding of things one reads is hampered if the reader does not comprehend words directly related to the topic of the text (p. 61). Given the varying topics of the texts students read in the Swedish L2 classroom, one could argue that having the appropriate vocabulary and having the means to further acquire lexical knowledge is significant. This may especially be the case with regard to topic specific vocabulary. Further, the core content containing a variety of different topics would create opportunities for teachers to apply incidental teaching methods.

However, there has not been a complete agreement among researchers regarding the actual impact of incidental vocabulary acquisition, and the question regarding its efficiency is still very much up for debate. Bordag and Rogahn (2018) claim that whether or not one adds words to one’s vocabulary seems to be dependent on a number of key aspects, thus making the process difficult with regards to measuring efficiency. Such key factors are listed as topic familiarity, exposure frequency, salience of the word form, and various context properties. Finally, and perhaps most importantly as it relates to this topic, the authors cite that text genre could also be related to the impact of incidental vocabulary acquisition. Furthermore, the authors also cite Waring and Nation who reported on the empirical evidence of studies of incidental vocabulary acquisition. The authors in this instance found results varying from learners acquiring between 4% and 25% of the words they were tested on in the different studies.

In addition, Pellicer-Sánchez and Schmitt (2010) claims that the research regarding incidental vocabulary acquisition in relation to authentic novels has been scarce in numbers, suggesting that most studies on the subject uses materials customized to the L2 reader’s level. To this, they identify that this approach has rendered small results, particularly when researchers use graded

readers as an approach. However, the authors admit that later and more exhaustive studies have resulted in higher degrees of learning.

As it has been established, there is little doubt that vocabulary is important for students to learn, and incidental learning may be a way of bypassing some of the time constraints of the classroom. Due to these factors, students need to understand the majority of the words in a text in order to create context and learn new words from it. Thus, there is a need for students to learn a not insignificant amount of topic specific vocabulary in multiple fields. Furthermore, the steering documents make it clear that they should be taught different genres. All these factors contributed to the topic this study will cover.

2. Aim and Research Question

The purpose of this paper is to review existing research in the field of incidental vocabulary acquisition in relation to literature and literary texts, with the aim to examine its efficiency as a method when it comes to vocabulary acquisition for EFL/ESL learners. The Swedish curriculum assures that literature will be a common theme in the English classroom. This study stems from the current research regarding how different forms of literature and literary texts can help L2 students expand their vocabulary through incidental methods of learning. This has resulted in the research question being as follows:

• To what extent can literature/literary texts be used to help ESL/EFL students acquiring vocabulary in relation to the concept of incidental learning?

3. Method

The approach to this study has come from a few different angles. The primary tool that was utilised during the research process was combing through the educational databases available for students at Malmö University, meaning that the vast majority of our sources were retrieved and accessed electronically. However, some search results led us to secondary sources that were available in the university library. In addition, there were also a scarce number of sources that were found through the reference sections of certain books. These books all contained chapters that covered our topic, but on a more surface-level scale than what was sufficient for this project. Thus, the reference sections of these books allowed for a more in-depth research process.

3.1 Search delineations

Our search process began in searching for the key terms “incidental vocabulary”, “ESL or English as a second language”, and “literature”, and limited the results to only show scholarly and peer reviewed materials. The search returned 44 search results through Malmö University’s standard educational database Libsearch. We then replicated this process in the databases ERC (Education Research Complete) and ERIC (through EBSCO). Moreover, we also searched Google Scholar using the same keywords mentioned which returned some useful results.

However, it became apparent rather quickly that said search produced a lot of false positives and far too many results to sort through without the tools of the other search engines. Using

Libsearch, ERC, and ERIC gave us the option to include and exclude certain specifics to optimise our research. Lastly, we also utilised our search terms in different combinations in a systematic approach to find as many relevant sources as possible.

3.2 Inclusion criteria

Since the focus of this paper is to review how effective it would be for L2 learners to acquire their vocabulary through incidental strategies, we feel obligated to motivate the inclusion of both English as a foreign language (EFL) and English as a second language (ESL) in our search criteria. In order to widen the scope of our research, we opted to include both terms as they are both considered to include with L2 aspects of language acquisition. Furthermore, in order to limit the searches to sources we consider to be more trustworthy, we only included peer reviewed materials between 1999 and 2019 as part of the process. Finally, since the context of the paper will deal with upper secondary education in Sweden, we decided to focus on research where

participants were of intermediate to advanced levels of proficiency, without making a criterion regarding the subjects’ age.

3.3 Exclusion criteria

While we motivated our choices to include both EFL and ESL as keywords in our research process, we still wanted to make the findings as applicable to the Swedish curriculum as possible. Because of this, we decided to exclude countries and regions where the educational systems and teaching methods bear little or no resemblance to Swedish educational contexts. As such, studies conducted on students in countries such as China, Thailand, Iran, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia and Indonesia were excluded. Nonetheless, it is necessary to point out that there is a significant amount of research regarding this area that is coming out of these countries and regions that may be applicable to other contexts.

Table 1. Utilised text types

Authors (year) Text

Rolls and Rodgers (2017) A corpus of science fiction books amounting to nearly 20 million words

Gablasova (2014) Two academic texts, one about history the other about geography

Pellicer-Sánchez and Schmitt

(2010) The novel Things Fall Apart

Pichette, de Serres and Lafontaine (2011)

Three sentences for each of the 16 target words

Reynolds and Bai (2013) Two texts of 300-400 words

Daskalovska (2011) The first eight chapters of Pride and Prejudice Daskalovska (2014) The children’s book A Little Princess

4. Results

This section will present the results of the studies that were found during the research-process. Firstly, the studies will be summarized where relevant findings related to our research question will be presented. Secondly, the different studies will be compared and contrasted to examine their similarities and how they may differ from each other. Finally, there will be a discussion about the studies and how they relate to the Swedish educational context. All the components of the results section will be under their respective heading.

In addition, since this study will include results from quantitative and qualitative studies alike, the approach toward presenting the findings have been done through the method of triangulation. Mackey and Gass (2005) have described triangulation as a method that can be applied to ensure that the gathered research can offer a variety of different perspectives (p. 181). We believe that this approach gave us a wider range of options in presenting a more comprehensive overview of the field with the added benefit of including different perspectives in the research area.

4.1 The efficiency of Incidental vocabulary acquisition

Within the research field, there are studies that suggest that literature or literary texts can be used in order for L2 learners to expand their vocabulary incidentally. For instance, Pellicer-Sánchez and Schmitt (2010) studied to what extent learners can incidentally acquire unknown vocabulary that exist in novels. The study was carried out on 20 Spanish EFL learners aged 23-26 with relatively advanced proficiency. The authors asked the participants to read the selected novel

Things Fall Apart over the course of a month, which included 34 unknown (for the learners)

African words. Before reading, the participants were informed that they were going to be interviewed once they had finished the book, without putting emphasis on what the contents of the interview would be. After reading, the learners were tested through an interview and a multiple-choice test in order to measure the acquisition of the target words. The results of the study showed that incidental learning could take place when reading a novel, as learners acquired 9.39 of the new words out of the 34 that were measured, which counted for 28% retention.

Furthermore, Daskalovska (2011) explored the degree to which intermediate L2 learners could acquire the meaning, spelling and collocation of 100 target words. The participants of the study were 122 secondary school students in Macedonia, 59 of which were in a control group and 63 in

book, while the control group did not. The students were tasked with reading the children’s book

A Little Princess by Frances Hodgson Burnett , which contains 66,938 words, in their free time

over the course of a month. The procedure was conducted through two tests, whom were both later used as post-tests. The first test focused on spelling while the other test focused on word-meaning and collocation, the latter also being a multiple-choice test to demonstrate partial knowledge. The data collected from the study gathered that 25.54% of the target words were acquired on average when the L2 students read an authentic novel. This average was based on student acquisition of the correct spelling of the word, collocation, and meaning. Moreover, the results also showed that there was a gain of partial knowledge regarding the meaning and collocation of words that was roughly 12% besides the roughly 25% of full acquisition.

In addition to her previous research on the subject, Daskalovska (2014) presented a more recent study which examined whether an authentic novel could stimulate incidental vocabulary

acquisition. The subjects of the study were 18 first-year university students in Macedonia,

studying English as their major who had studied English for eight years in primary and secondary school in addition to close to a year of university studies. The students were tasked with reading the first eight chapters of Pride and Prejudice, consisting of 11672 words, whilst listening to a recording of a reading of the text and were tested on their vocabulary gains the day after without prior knowledge that there would be a test. Results that were presented revealed that the students learned 24% of previously unknown words. Furthermore, the lexical gains of students of varying pre-test vocabulary sizes were compared which made it evident that the size of the existing vocabulary did not appear to have an effect on the incidental vocabulary acquisition. In addition, the analysis also suggests that nouns were the easiest for students to acquire, and that the

frequency of the words in the text did not have a significant effect on whether the students learned them.

Moreover, Reynolds and Bai (2013) studied whether freedom of reader choice has an effect on second language incidental acquisition of vocabulary. The participants in this particular study were 78 freshmen university L2 English reading course students in Taiwan, out of which 39 were allowed to choose from a prepared selection of texts whilst the other 39 were assigned texts. The study was based on a multiple-choice test that assessed comprehension and the knowledge of the target words, which in this case were nonsense words, i.e. words that are not real. This to ensure that the participants did not know the words prior to the study. Results of the study showed that

that self-choice in what to read increased student interest in texts. In essence, students choosing a text appears to make them more interested in it. Furthermore, there appeared to be a positive correlation between student interest in a text and incidental vocabulary acquisition.

Gablasova (2014) conducted a study to examine the differences in incidental vocabulary

acquisition between L1 learners and L2 learners. Involved in the procedure were 64 Slovak high school students aged 17-20 who were all intermediate or advanced users of English. The

participants were split into two groups where one read a text in their native language and the other read one in English. Both texts were considered academic texts, one about history and the other about geography. The data collected in the study suggested that students are more inclined to acquire vocabulary incidentally when reading in their native language than in their L2.

Furthermore, results found the L1 learners to have a deeper understanding of the words that they learned, as opposed to the L2 learners. Finally, the post-test conducted a week after the study showed the L2 learners to have retained a lesser amount of vocabulary than the L1.

Furthermore, there have been studies which have taken slightly differing parts in the attempts to determine the efficiency of Incidental vocabulary acquisition. Pichette, de Serres and Lafontaine (2011) investigated which of two different language skills, reading and writing, would foster incidental vocabulary acquisition better than the other. This particular study tested 203 French speaking L2 university students of English on a set of sixteen words, eight concrete and eight abstract, on a writing task and another set of sixteen on a reading task. Furthermore, a delayed recall test was performed to measure to what degree the acquisition of these words decayed over time. The results from the immediate recall tests suggested a superior recall for writing tasks over reading tasks, where the numbers also favoured concrete words over abstract words. However, the delayed recall scores demonstrated that the superiority of the concrete word recall

disappeared over time.

Finally, Rolls and Rodgers (2017) examined the prevalence of incidental technical vocabulary relating to science in science fiction books to see if they could be used to teach said vocabulary to students. In their attempts to determine this, the researchers ran a corpus of science fiction books amounting to nearly 20 million words, spanning over twenty years of publication, through a computer program. The study then compared these nearly 20 million words to a list of

technical vocabulary thought necessary for scientific literacy. Out of the 318 target word families, there was only one that did not appear in the books that they analyzed. Their analysis suggests

that reading fifty thousand words of science fiction could expose the reader to 21% of the word list, but that such a relatively small amount of text risks that the target words are not met many times. The authors suggest that a reading commitment of half a million words could expose students to 21% of the target words ten or more times and 83% once or more and that this might, according to their analysis, be the most economical target number of words.

4.2 Similarities and differences in the selected studies

When comparing the results of the studies, there is evidence to suggest that incidental vocabulary learning can be stimulated from reading different literary texts. For example, there were three studies which all returned similar results when testing the efficacy of incidental vocabulary acquisition by reading novels. The percentage of target words acquired landed at about 24-28% percent across the three contributions that conducted their studies on this type of text (Pellicer-Sánchez and Schmitt 2010; Daskalovska 2011; Daskalovska 2014).

As is noticeable, the results of the studies which examined incidental vocabulary acquisition in relation to novels had fairly similar results, despite the target words measured varying in both numbers and frequency. Naturally, this could be due to the length and degree of difficulty of the books that were used. To further demonstrate, Daskalovska (2011) tested 100 target words that appeared between 1-20 times on the children’s book Little Princess, whereas Daskalovska (2014) conducted her study based on eight chapters from Pride and Prejudice using 51 target words, most of them appearing 2-5 times. To this, it is also worth noting that Little Princess is categorised as a children’s book while Pride and Prejudice is considered a classic, meaning that the language in the respective books would differ in difficulty, meaning that the books chosen for the studies were applied with regard to the learners level.

A natural discrepancy between the studies were the target words measured. Not only in the total number of words as previously mentioned, but whether they were fictitious or real. Pellicer-Sánchez and Schmitt (2010) used African target words from a book otherwise written in English to ensure that the participants did not know them prior to testing. Likewise, Reynolds and Bai (2013) used made up or nonsense words for the same purpose while the rest of the studies used English words. Despite these differences, the results of the studies were similar, regardless of the authenticity of the target words. Webb and Nation (2017) cite that in order for a learner to

would allow them to understand the majority of the known words to form a meaning of the unknown words. Lastly, this claim is echoed in Pichette et al. (2011) who wanted to ensure that the L2 learners in their study were advanced enough to make it through their examination without too much difficulty, meaning only learners of intermediate and advanced proficiency were included.

Additionally, Pichette et al (2011) noted substantial decay in the vocabulary learners acquired in their study. This was found through a delayed post-test one week after the initial test where results showed that the acquisition had dropped from 25.4% knowledge of words to 12.65%. Similarly, the tendency for a decay in knowledge could also be recognised in the Gablasova (2014) study which also detected this phenomenon by issuing a delayed post-test.

In relation to this, Daskalovska (2014), who gave the participants one hour to read a text, argued that measuring the acquired knowledge would be more accurate if a test was performed one day after reading rather than after one hour. In turn, Pellicer-Sánchez and Schmitt (2010) noted that their study was limited due to their examination not including a delayed post-test, adding that intentional repetition and multiple exposure to the words would only ensure that the results would stand. In this instance, there could be reason to argue that Pellicer-Sánchez and Schmitt are correct in their admission regarding the limitations to their study, particularly in relation to the findings of the previously mentioned studies that included a delayed post-test in any capacity.

A further problematic passage when measuring incidental vocabulary acquisition are argued by Pellicer-Sánchez and Schmitt (2010) who problematise a lack of measuring partial knowledge in many studies on the subject. They point out that many studies measure in ways that they consider to be lacking in sensitivity regarding partial and smaller gains in vocabulary knowledge, one aspect of this being the reading time assigned to participants. In relation to this critique, Daskalovska (2011) used a type of testing that allowed for partial knowledge gains to be measured, with results suggesting that there were even greater partial gains than fully realised gains. Gablasova (2014) also measured partial gains where the L2 students had a mean of 8 form-meaning connections, having some or full knowledge of the 12 target words, with this number dropping to 6.81 on the delayed post-test one week later. However, Daskalovska (2014) admitted that the reading time assigned to participants (one hour) would not have been enough to

determine outcomes of extensive reading, and that measuring this called for a larger text and subsequently a longer period of time to read.

Moreover, Pellicer-Sánchez and Schmitt (2010) claim that the results of the study might have been weakened slightly due to the fact that the book was assigned to the participants rather than them having the possibility to choose what to read themselves. In addition, they also noted that the numbers presented in the results may not have been affected to a large extent, due to most of the participants enjoying the chosen novel. Furthermore, the execution of the study was based on the learners being encouraged to read the book for pleasure with no demands attached.

Conversely, the findings in the Reynolds and Bai (2013) study suggested a positive connection between greater incidental vocabulary acquisition and the availability to choose what to read. This was based on the conclusion that the freedom of reader choice is directly related to the interest a reader will have in a text. Reynolds and Bai (2013) found that on a multiple-choice test with three options for each of the six questions the participants who chose their own texts had learned a median of 4.44 words whilst the students that had texts selected for them had a median acquisition of 3.82.

There were some ample differences in the approaches to the studies. Firstly, the participants in the studies varied from 18-203 where Daskalovska (2014) had the smallest sample size,

motivating the selection through testing students considered advanced learners of English to determine the differences in their vocabulary knowledge. Pichette et al. (2011) had the largest test group where all participants were considered to have intermediate or advanced proficiency. Reynolds and Bai (2013) had 78 students participate in the study. It is worth noting that while some of the studies had a more selective process in choosing participants for their examinations, other studies seemed to essentially include all learners that were available to them.

Furthermore, the time participants had to read text differed in the studies. Gablasova (2014) gave learners ten minutes to read a short text while Daskalovska (2011), and Pellicer-Sánchez and Schmitt (2010) respectively allowed for a month to finish the assigned novels.

Despite all these differences in methodology, several recurring themes emerge. Firstly, the participants appear to gain some amount of vocabulary incidentally as they read for content, regardless of whether the words are in the target language, another language, or even real. Secondly, there appears to be a decay over time of the words gained incidentally. Thirdly, participants having a choice regarding the reading materials appears to impact the amount of vocabulary gained incidentally. And finally, there appears to be some amount of partial knowledge of the target words gained, perhaps as much as the amount of fully learned words.

Unlike the other studies reviewed, the Rolls and Rodgers (2017) study was one study that did not have human participants. Yet, this study could prove to be crucial in answering to what extent literature/literary texts can be used to help ESL/EFL students acquire vocabulary incidentally. Rolls and Rodgers examined whether SFF books could aid science students acquire technical vocabulary in a second language. Their finding of a not insignificant amount of science

vocabulary in this genre opens up the possibility of using different genres for teaching technical vocabulary to students.

5. Discussion

Upon examining the studies in this paper, there is empirical evidence to suggest that literature and literary texts can be a tool in helping learners acquire vocabulary incidentally. However, this section will discuss to what extent it could be applied to a Swedish EFL/ESL upper secondary classroom context.

As previously mentioned, text genre could be related to the impact of incidental vocabulary acquisition (Bordag & Rogahn, 2018, p. 403). When looking at the National Swedish Curriculum, the progression in literature across the courses is quite clear. In English 5 the core content states that literature should be taught, but does not specify which genres, whilst in English 7 older or contemporary literature is introduced (Skolverket, 2011). In addition to the curriculum’s

structure, this progression is also something that can be noted in the studies, as most researchers used literature that catered to the proficiency levels of their participants. The clearest examples of this are the Daskalovska (2011) and Daskalovska (2014) studies, where the latter applied chapters from the classic Pride and Prejudice to a more advanced group of students, while the former used

The Little Princess, a children’s book on learners with less advanced knowledge.

As previously mentioned, the estimated words needed to comprehend a text is 95-98% in order to be able to incidentally acquire vocabulary. Graded readers and Young Adult fiction (YA) could be useful to bridge the gap in vocabulary knowledge from English 5 to English 7. According to Webb and Nation (2017), graded readers are available, and useful up to the fairly substantial 8000-word frequency level, that is, they contain the 8000 most common words in English. After this level, Nation suggests moving on to less simplified texts. Pellicer-Sánchez and Schmitt (2010) have also proposed that learners at some point need to move on to more authentic texts in order to become familiarised with more complicated vocabulary, in this case mid-frequency words.

This could suggest that a learner would have to have a rather large vocabulary in order to reap benefits of incidental vocabulary acquisition.

Furthermore, Matz and Steiger (2015) discuss the advantages of using YA fiction in the classroom. More specifically, the authors suggest that personal development, changes in perspective and that the authenticity of the texts may motivate students. However, they also claim that most YA fiction books are not always adapted to a students’ vocabulary level.

Considering this factor, a suggestion could be made that this category of literature could be used as a bridge between graded readers and more complicated forms of literature. Furthermore, Matz and Steiger suggest that YA fiction can be used to awaken interest in reading after which they can be enticed into reading classics. This is in alignment with Skolverket (2011) where progression in difficulty in literature culminates in older literature classics, which is introduced in English 6 and 7 where the students are likely to be more advanced. Moreover, Matz and Steiger (2015) suggest that learners’ reading experience should be scaffolded. Lastly, the authors argue another

advantage of using YA fiction includes a vast variety of genres available for reading as well as availability of characters and situations to identify with for young adult readers. (Matz & Steiger, 2015, p. 122-133)

Lightbown and Spada (2017) point out that it may be difficult to understand some texts, despite them not being particularly complicated, if one lacks certain vocabulary. They exemplify this by giving the example that reading about a court case in a newspaper could prove difficult if the reader does not understand the vocabulary used in a courtroom (p. 63). Rolls and Rodgers (2017) suggest that genre specific literature can be used to teach students varying vocabulary depending on the genre of the texts. For instance, they found that SFF literary texts had 46% more science words than general literature and suggest that reading SFF could help students gain science specific vocabulary. This, in conjunction with the findings of the other studies suggest that varying genres could be used to teach students more discipline specific vocabulary. These types of discipline specific vocabulary are called technical words by Webb and Nation (2017). And he defines them as words that may be relatively infrequent overall but are significantly more frequent in specific contexts. The previously mentioned example regarding the courtroom ties back to this. This in conjunction with the graded reader to YA to advanced texts approach in addition to the flexibility of the Swedish National Curriculum sets the stage for an approach to incidental vocabulary acquisition.

Furthermore, students’ interests in texts is an important aspect when working with literature in the classroom. As results showed in the Reynolds and Bai (2013) study, incidental vocabulary acquisition may be more fruitful if learners are allowed to choose their literature by themselves based on their interests and what they enjoy reading. Parallels between this finding can be located in Krashen and Terrell’s (1983) “natural approach”-theory, which suggests that allowing learners to work with topics that interest them can lower the so-called affective filter. The affective filter according to the authors is essentially a filter of uncertainty and enjoyment, if the students understand the situation, find it enjoyable and that they can handle it they will be more receptive to learning (pp. 19-20).

There is a case to be made that the Swedish National Curriculum (Skolverket, 2011) could support this type of work as there are no required reading lists but merely instructions on genres and types of texts that are to be taught. The flexibility in choosing reading materials could in this case be of advantage to teachers. Reynolds and Bai (2013) concluded that there is a connection between interest and to what extent incidental vocabulary can be gathered from a text. However, this does not mean that teachers should simply allow students to choose freely. The Reynolds and Bai study gave learners a choice of ten preselected text which still resulted in increased acquisition. This could suggest that teachers still have the possibility to select texts with regard to their students’ interests, while still remaining aligned with what the curriculum instructs.

As it has been established, there have previously been disagreements and confusion regarding incidental vocabulary learning and its definition. Sok (2014) suggests that this factor is present in both research and L2 pedagogy, which in turn has resulted in pedagogical attitudes that favour either incidental learning or its counterpart intentional, resulting in a dismissal of the other. However, there is reason to suggest that research has progressed in this area. Several of the researchers that are cited in this text have concluded that a balance between incidental and intentional methods to teach vocabulary likely would be the most beneficial for learners (Pellicer-Sánchez & Schmitt, 2010; Daskalovska, 2014; Daskalovska, 2011).

There is also the question of whether the researchers were able to isolate learners from exposure to other sources of gaining the vocabulary incidentally outside of the reading of the specific text. The studies varied, and some used nonsense words, or words in African that would make it unlikely that students would encounter them outside of the text in question. These studies

showed similar results to those that had words in English suggesting that this may be a non-issue or at least a minor concern.

In addition, Loewen (2015) has also argued that the pedagogy for vocabulary instruction, similar to the teaching of other language skills, needs to be varied in order to be beneficial for L2 learners of English. He further suggests that intentional methods to acquire vocabulary might be the more successful option for learners at a low level of proficiency (p. 108-109). These notes are important to keep in mind when applying the research in this paper to an English classroom in Sweden, as all L2 learners participating in the various studies were either of intermediate or advanced level of proficiency. In relation to this, Restrepo Ramos (2015) claims that by just reading, the likelihood of a reader gaining vocabulary unintentionally increases. However, he also argues that whether the claim holds up or not is dependent on the learner’s level of proficiency, meaning that research has shown reading to be the most beneficial to low and intermediate learners while students who are at a higher level are more likely to acquire incidental vocabulary through listening. Interestingly, this could suggest that if studies are conducted on learners at a lower level than the ones examined in this paper, results of words acquired could be more substantial.

Moreover, researchers claim that there could be a natural connection between incidental and more intentional teaching of vocabulary. Webb and Nation (2017) suggests that when teachers offer explanations of the meaning of a word to a student in the L2 classroom, the prospect of a student learning the word increases, which further supports that a need for a combination between incidental learning and explicit instruction.

6. Conclusion

There is reason to argue that vocabulary is a cornerstone of communication. However, there are different paths a learner can take in order to improve their lexical knowledge. This paper aimed to examine to what extent literature or literary texts can be of help for ESL/EFL students to acquire vocabulary through incidental learning. Based on the findings in the research presented, there are a number of conclusions that can be drawn. Firstly, a key finding when reviewing the studies is the factor of the decay of knowledge in incidental vocabulary acquisition. Secondly, reading is likely to promote words being learned incidentally unless there are too many words in the text that are unknown to the reader. Thirdly, there is a need for explicit, intentional

instruction to complement the incidental aspects of learning in order to optimise the potential of students further acquiring vocabulary.

Naturally, this study had its own limitations to consider. This study only examined reading as a means of incidental vocabulary acquisition. Since incidental learning may also occur from consuming music, games, movies or other media, the narrow scope of this study could very much be considered a limitation due to reading being only one aspect of the L2 classroom, and the efficiency of incidental vocabulary acquisition may be higher when different language skills are combined. A further limitation may be of a more practical nature, the actual application of this knowledge for teaching students may be difficult to apply in the classroom and may require having students read as homework instead, which is very much already a reality for Swedish students. Furthermore, a problematic passage related to the research question of this paper was that there were not a lot of studies that looked at genre specific literature. However, the Swedish curriculum is scarce in specifying genres that should be taught, which means that the studies used in this paper are very much applicable in this context.

Moreover, with regard to the Swedish school context, another limitation is the lack of Swedish studies about incidental vocabulary acquisition, which meant that this paper was limited to studies in contexts similar to the Swedish. A study conducted on Swedish L2 learners with similar methodology as the ones reviewed could help highlight eventual differences the context may possess. This could also be an excellent point of entry for anyone considering doing a degree project related to this area of research.

Finally, based on the findings and conclusions this paper draws upon, we conclude that there is a need for more comprehensive studies examining the efficiency of incidental vocabulary

acquisition in relation to different forms of literature, both with regard to the number of

participants, the number of target words measured, genre, and length of the studies alike. There is also a need to explore the Swedish L2 classroom in relation to incidental vocabulary acquisition. Additionally, there is reason to argue that there is a need for studies that further investigate the decay of knowledge over time to get a more feasible base from where the efficiency of incidental vocabulary acquisition can be viewed.

7. References

Ahmad, S. (2012). Intentional Learning Vs Incidental Learning. International Association of

Research in Foreign Language Education and Applied Linguistics ELT Research Journal, 1, 71–79.

Bordag, D., & Rogahn, M. (2018). The role of literariness in second language incidental vocabulary acquisition. Applied Psycholinguistics, 40(2), 399–425. doi: 10.1017/s0142716418000620

Cho, K. S., & Krashen, S. D. (1994). Acquisition of vocabulary from the Sweet Valley Kids series: Adult ESL acquisition. Journal of Reading, 37(8), 662-667.

Daskalovska, N. (2011). The impact of reading on three aspects of word knowledge: spelling, meaning and collocation. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 2334–2341. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.04.103

Daskalovska, N. (2014). Incidental Vocabulary Acquisition from Reading an Authentic Text. The Reading Matrix Volume 14, Number 2, 201-216.

Day, R. R., Omura, C., & Hiramatsu, M. (1991). Incidental EFL vocabulary learning and reading. Reading in a Foreign Language, 7(2), 541-551.

Gablasova, D. (2014). Learning and Retaining Specialized Vocabulary From Textbook Reading: Comparison of Learning Outcomes Through L1 and L2. The Modern Language

Journal, 98(4), 976–991. doi: 10.1111/modl.12150

Horst, M., Cobb, T., & Meara, P. (1998). Beyond a clockwork orange: Acquiring second language vocabulary through reading. Reading in a Foreign Language, 11, 207–223.

Krashen, S. D., & Terrell, T. D. (1983). The natural approach Language acquisition in the

classroom. New York Pergamon Press.

Lightbown, P., & Spada, N. M. (2017). How languages are learned. Vancouver, B.C.: Langara College.

Loewen, S. (2015). Introduction to instructed second language acquisition. New York: Routledge. Mackey, A., & Gass, S. M. (2005). Second language research: methodology and design. London: Routledge.

Matz, F., & Steiger, A. (2015). Teaching Young Adult Fiction. In Delanoy. W.,

Eisenmann, M., Matz, F., (Eds.) In Learning With Literature in The Classroom (121-140). Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

O’Keeffe. A. (2012). Vocabulary Instruction. In Burns, A., & Richards. J. C. (Eds.), The

Cambridge Guide to Pedagogy and Practice in Second Language Teaching (236-244). Cambridge:

Pellicer-Sánchez, A., & Schmitt, N. (2010). Incidental vocabulary acquisition from an authentic novel: Do things fall apart? Reading in a Foreign Language, 22( 1), 31– 55.

Pichette, F., Serres, L. D., & Lafontaine, M. (2011). Sentence Reading and Writing for Second Language Vocabulary Acquisition. Applied Linguistics, 33(1), 66–82. doi:

10.1093/applin/amr037

Pitts, M., White, H., & Krashen, S. (1989). Acquiring second language vocabulary through reading: A replication of the Clockwork Orange study using second language

Restrepo Ramos, F. D. (2015). Incidental vocabulary learning in second language acquisition: A literature review. PROFILE Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 17(1), 157-166. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v17n1.43957.

Reynolds, B. L., & Bai, Y. L. (2013). Does the freedom of reader choice affect second language incidental vocabulary acquisition? British Journal of Educational Technology, 44(2). doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2012.01322.x

Rolls, H., & Rodgers, M. P. (2017). Science-specific technical vocabulary in science fiction-fantasy texts: A case for ‘language through literature.’ English for Specific Purposes, 48, 44–56. doi: 10.1016/j.esp.2017.07.002

acquirers. Reading in a Foreign Language, 5(2), 271-275.

Saragi, T., Nation, I. S. P., & Meister, F. (1978). Vocabulary learning and reading. System, 6, 72–78.

Skolverket. (2011). English. Stockholm: Skolverket. Retrieved 2019-12-01 from:

https://www.skolverket.se/download/18.4fc05a3f164131a74181056/1535372297288/English-swedish-school.pdf

Sok, S. (2014). Deconstructing the Concept of ‘Incidental’ L2 Vocabulary Learning. Teachers College, Columbia: Columbia University Working papers in TESOL & Applied Linguistics. Retrieved 2019-11-29 from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1176843.pdf

Webb, S. A., & Nation, I. S. P. (2017). How vocabulary is learned. Oxford: Oxford University Press.