Best of Both Worlds

A Platform for Hybrids of Computer Games and Board Games

Master Thesis in Interaction Design

Jonas Rören

Malmö University / Malmö Högskola

Spring 2007

Supervisor: Per-Anders Hillgren

Examinator: Jonas Löwgren

Abstract

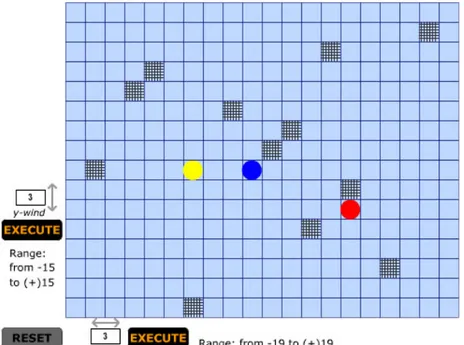

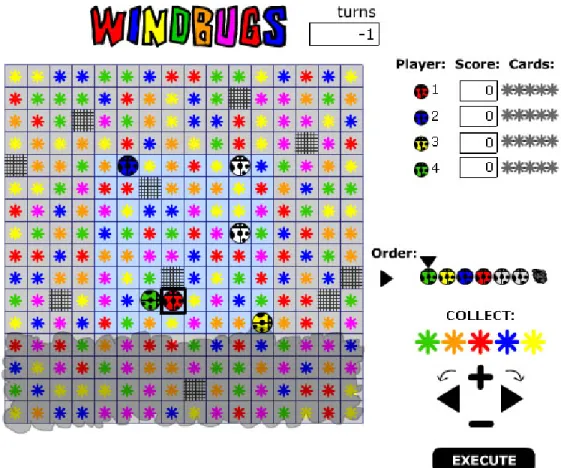

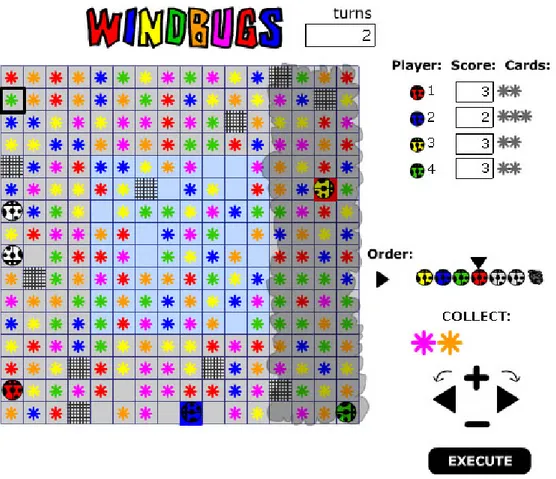

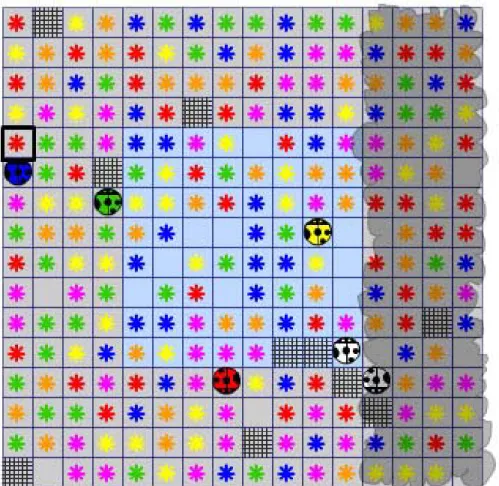

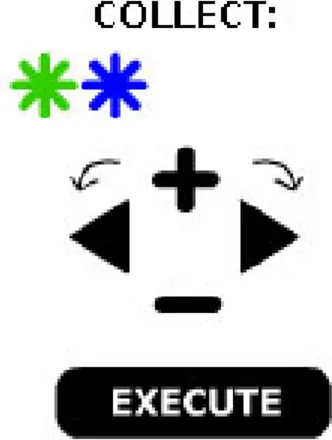

This report describes my work with developing a game for a gaming platform that enables hybrids between board games and computer games. My ambition has been to develop a game that takes advantage of the novel possibilities that this platform permits. Among those are to operate with a combination of the computer game traits of complexity in the games and ease of playing; as well as the board game / card game traits of combining social dynamics around a game session with ability to keep information hidden from other players. This is accomplished by a combination of mobile phones and a computer connected to the Internet. The screen of the computer will serve as board and the phones will display cards and other private information to the players, as well as functioning as the players’ means for interaction with the game. The game developed, Wind Bugs, takes advantage of the complexity of game states that a computer easily can handle. Effort has been put into finding mechanics with a level of complexity while still implementing them in way that makes them both playable and enjoyable.

Rather than focusing on immersion, which has become common in the design of computer games, hopes are that games for this platform, including the game developed in this project, will give room to social dynamics among the players. Though operating with the use of mobile phones, the platform will not support “mobile gaming”; the proposed setting is a group of players surrounding a big screen.

Keywords: Games, board games, computer-augmented games, game mechanics,

game rules, game dynamics, game platforms, abstract games, themed games, mobile phones, Extransit, Mobile Interaction Suite, Windmaker, Wind Bugs.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following people:

• Åsa Harvard, Jörn Messeter and Erik Königsson for making it possible for me to do this master project at Malmö University

• Per-Anders Hillgren – process supervisor • Mikael Jakobsson – game supervisor • Jonas Löwgren

• Tomas and Pelle at Extransit for technical support, guidance, play-testing and faith in the project

• Ola Rören and Esko Vuonokari for play-testing

• Björn Sjödén for views on both the report and the game • My fellow students for their ideas and opinions during seminars • Kirsti for everything

Table of Contents

Abstract _____________________________________________________________1 Acknowledgements ____________________________________________________2 Table of Contents _____________________________________________________3 Introduction: explaining concept and goal __________________________________4 Theoretic framework: games, aesthetics, cognition, interaction _________________6 What is a game? __________________________________________________6 What is a board game? _____________________________________________6 What is a computer game? __________________________________________8 Combining strengths: best of both worlds? _____________________________8 Themed board games vs. abstract board games ________________________10 Tangible vs. virtual, aesthetics of mind and simulation ___________________13 Fixed vs. modifiable rules __________________________________________15 Private vs. public information _______________________________________16 Rules, mechanics_________________________________________________18 Emergent vs. progressive __________________________________________23 The social dimension – human dynamics ______________________________23 Mechanics, representations and dynamics – a three level model ___________26 Fun and games __________________________________________________29 Methods and process _________________________________________________31 Debunking immersion _____________________________________________31 A platform or a game? ____________________________________________32 A prototype game: making Windmaker 1.0 and 2.0 _____________________33 A German approach: game mechanics ________________________________35 Mechanics for Windmaker 1.0, 2.0 and their successors __________________36 Windmaker 3.0 __________________________________________________43 The concept of mechanics – revisions needed? _________________________44 Getting down on the floor__________________________________________44 A second paper prototype__________________________________________57 Implementing Wind Bugs – going digital again _________________________59 Test sessions during development ___________________________________61 Initial test results of digital Wind Bugs - mechanics _____________________62 Initial test results of digital Wind Bugs – representations _________________64 A “proper” test session: participation, observation, analysis _______________65 Results – my achievements_____________________________________________69 Discussion of results and process ________________________________________72 Is there a future for hybrid game forms?______________________________73 Finding allies and markets _________________________________________74 References__________________________________________________________76 Bibliography_____________________________________________________76 Web sites_______________________________________________________80 Appendices _________________________________________________________81 Appendix 1: Game Mechanics listed on BoardGameGeek _________________81

Introduction: explaining concept and goal

My aim with this project is to develop a new form of gaming, a hybrid of computer games and board games that represents “the best of both worlds”.

On the technical side this will be solved by a combination of mobile phones and a computer connected the Internet. This will be made possible by technology and know-how supplied by the Swedish company Extransit.

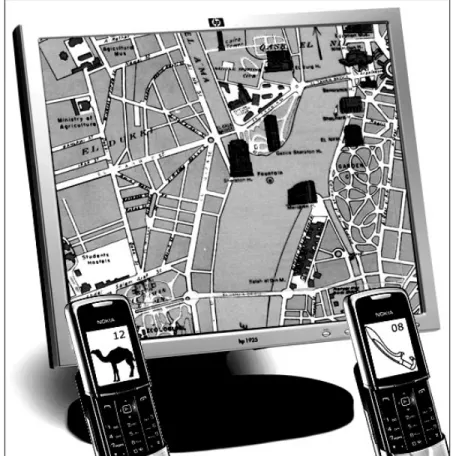

My technical solution for the gaming concept is that every player in a game has a mobile phone equipped with software for the game. The phones are connected to a single computer (via a server). The computer screen will analogous with a game board. As all players view the same screen (board), this implementation is not similar to the various online board games that are quite popular today. As the players can be presented private information (unavailable to the others) on the mobile phones, possibilities for implementation of board-type or card-type games emerge. My hope is, though, that the platform will bring forth a new generation of computer-board games that literally will represent the best of both worlds.

Figure 1: Basic platform concept. Players share a “board” in form of a computer

screen. Private information is presented on mobile phones. Players can share a physical space and still operate with information that is hidden from other players. Mobile units communicate with the computer running the board through a server.

By “augmenting” (a term that I not really like in this context) a board game with computers, possibilities for new forms of gaming emerge. The game can handle game states with a complexity that would be difficult or uninteresting for players to

manage without support. Yet difficult to handle, the complex game states might give room to interesting gameplay. Many computer games features rules and game states that are complex compared to board games – yet still they are often easy to get started with. Thus, I will strive towards developing a game that shares these computer game traits: easy access to complex game states.

An aspect of board gaming that I do not want to “design away” is the social context that occurs around a board gaming session. Similar situations might occur in the playing of multiplayer video games. But, when information is not to be shared among the players (as is common in card games and modern board games), the solution is generally to play over a network. This type of gaming (networked) can of course be described as social – but compared to the playing of board games it is limited or at least different. My aim will be to develop a platform that can support a “genuine board game setting” while playing a complex computer driven game.

Theoretic framework: games, aesthetics, cognition,

interaction

What is a game?

Jesper Juul has made an attempt at describing, comparing and evaluating the various definitions of a game that has been proposed in various principles.1 His definition (I suppose) aims at being the definitive one, putting an end to arguments over definitions. It tries to grasp all features of a game and avoid features that do not belong to games. It is a solid definition, but as many of the previous, it is a rather heavy one:

A game is a rule-based system with a variable and quantifiable outcome, where different outcomes are assigned different values, the player exerts effort in order to influence the outcome, the player feels emotionally attached to the outcome, and the consequences of the activity are negotiable.2

A simpler and more catchy (and easier to recall) version of this definition has been proposed by Craig Lindley. Lindley decidedly rules out criteria (from Juul’s definition) that relate to the player rather than to the game itself:

[A] goal-directed and competitive activity conducted within a framework of agreed rules.3

What is a board game?

A board game is, essentially, a game that is played on a board.

Folk board games include Chess, Backgammon, Mancala and Go. Commercial board games include modern-day classics as Monopoly, Scrabble and Risk; loads of new titles are released every year. Folk board games are supposedly created by players in an iterative process of playing and adapting the rules (analogous to folk music) over long periods of time. This evolutionary process sorts out game features that are irrelevant or simply destroy the gameplay. The harmonious character of the rules and mechanics of most folk games is supposedly in debt of this process. Commercial board games are created by game designers.4

With only slight knowledge of the game titles mentioned above; it is rather obvious that there are some general differences between these folk and commercial games. The most obvious difference is perhaps that many commercial board games have a fictional dimension, often referred to as a theme, while a folk game tend to represent nothing but itself. Games without themes are usually called abstract games.5 In a

1 Juul (2005): 29-36 2 Juul (2005): 36

3 Lindley (2005), Salen & Zimmerman (2004): 80 have a similar definition.

4 Juul (2005): 81. A similar way of describing this relation is to distinguish between evolved and

invented games (Parlett 1999: 5)

5 Thompson (2000), In Parlett’s view, though, folk games has initially featured themes, but these

have been sorted out by the evolution of gaming for being irrelevant to the games per se (1999: 6).

wider sense, especially when incorporating computer games, it is unsatisfying to use only two categories - abstract and themed. Instead this scale could be viewed as a continuum – ranging from strictly abstract (backgammon) to extremely representative (flight simulators).6

Juul has made an attempt at finding discrete categories in the continuum between abstract and representational. Slightly more representational than the pure abstract games are iconic games. In this category fall card games played with a standard deck. These games clearly have a representational element (court cards) but this has no relevance in the actual gameplay. The next levels hold games that represent a fictional “world”. Depending on to what extent these worlds are “believable” and logically coherent Juul labels them incoherent world games and coherent world games. The game of chess is in Juul’s view an incoherent world game as it depicts a battle between two forces, but none of the mechanics of the game can be derived as a result of this fictive reality (the battle), the player must at all times consult the rules of the game rather than the representation.7 The fictive dimension of games will be investigated further down in the report.8

A commonly recognized quality of board games is that positions are discrete. In chess, for example, there are a definitive number of squares (64), and every piece will occupy one of these squares (if it is not taken). It is of no relevance to the game if a piece is placed in the exact middle of a square – or close to border of another square. This is contrasted to games of skill (Soccer, Pick-up sticks/Mikado) – where the positions are nearly endless.9 Most computer games must be regarded as games of skill in this sense, from the player’s view the game positions are experienced as continuous (in reality, of course, everything is discrete and exact in a computer). Computer game theorist Juul’s notion of game states, the exact position of everything in a game at any given moment, is actually more suitable to board games than to computer games: though all positions in a computer game session is at any time represented exactly (discrete) by the computer – the players’ experience will by necessity be more fuzzy (“crawling close to the gate, gun in hand” rather than the exact coordinates). Accordingly, a board game player is deliberately manipulating the game state while, in a sense, the game state is only an effect of the players’ interaction with a skill-based computer game.10

Nowadays, board games like Pictionary and Cranium include activities of a fuzzy character (drawing, molding, acting etc.). Game states during these activities are fuzzy as well. Even more so, actually, than in a skill-based computer game, as these activities are not represented exactly by any system. The only discrete game states in these games are the players’ actual advancements on the game board, which in reality is a rather limited part of the gaming experience. Yet, still it is this element that makes these games recognizable as board games. These games might be treated as board games with skill-based elements. My bet is that this category of games is here to stay.

6 Adams (2003) 7 Juul (2005): 130-133

8 See the chapters "Themed board games vs. abstract board games" and "Mechanics,

representations and dynamics – a three level model".

9 Gobet, Retschitzki & de Voogt (2004): 2 10 Juul (2005): 59-65

What is a computer game?

Basically, computer games are games that are played on a computer.

Unlike earlier forms of games, computer games have been studied from an aesthetic viewpoint by a rather large group of researchers. This fact has puzzled some of them.11 In Espen Aarseth’s view, the interest in computer game aesthetics derives from the large amount of “artistic” content in these games that are recognizable to researchers in fields like the history of literature or film. Words, sounds and images in games can be analyzed with methods that are available and ready to use. This fact, though, might be a trap. Instead of analyzing the real meanings and aesthetics of games, the researchers might end up studying easy recognizable elements that happen to fit their available theories. Aarseth continues to conclude that the reason that (computer) games interest practitioners in the humanities is that they are simulations of virtual environments. Accordingly, games like Monopoly (“simulating” real estate business) and Risk (“simulating” war) would be of interest for these researchers rather than computer-supported versions of folk games like backgammon or abstract computer games like Tetris.12

As shown in the previous chapter, most commercial board games contain some form of theme or representation. There is, as follows, no clear line between board and computer games in this regard. In fact, Aarseth’s point specifies why there is interest for computer games in the humanities, rather than saying what computer games are or what they should be. The computer game genre is wide and some popular computer games can in reality hardly be categorized as games (Sim City is a popular example of a computer game with no clear goal - a toy rather than a game). Lindley has proposed a model where every computer game can be placed in a continuum between three “temporal semiotic systems”: simulation, game and narrative.13 Board games can certainly be categorized with this model as well. Board games, though, might not have alienated themselves from being “pure” games to the same extent as some computer games. It is obvious, though, that a variety of board games of the commercial era have taken some brave steps towards being simulations. Narrative elements might be found in board games as well, especially in the form of “back stories” (short stories explaining the background of the conflict that is “simulated” in the game).

Combining strengths: best of both worlds?

Some previous attempts at combining computer games with board games have been made. These attempts have to a great extent had the goal of making board games better with computer technology, making them more like computer games.14 My goal could, in a way, rather be described as making computer games more like board games. I will briefly go through what could be gained from both perspectives.

11 Juul (2001) 12 Aarseth (2003): 1-2 13 Lindley (2005)

14 Mandryk, Maranan & Inkpen (2002); Magerkurth, Memisoglu, Engelke & Streitz (2004), Eriksson,

In the beginning of this project I had the idea that a platform like this could enable games relying less on immersion and more on player to player interaction than computer games normally do. While I still regard this point as interesting I am aware that the degree of experienced immersion in for example “party-type” video games is low compared to the prototypical computer games. A game feature that is difficult to implement in video game consoles is private information – meaning that each player has some information that the others lack. This feature is inherent in most card games (none of the others know your cards, and you don’t know theirs) and in many commercial board games. Private information is of course easy to implement in computer games that are played over a network, but these games separate the players and do not give much room to social interaction among the players.

If the point of departure is board games, it might not be obvious what is to be gained by “augmenting” board games in the way that is done with this platform – why not just play a traditional board game? Games on a platform like this will be able to have some unique qualities (compared to traditional board games):

• Relieving the players from tedious calculations and mechanical actions while at the same time delivering complex games.15

• Game states may be hidden while players are yet able to manipulate them.16

• Possibility for more advanced game boards, e.g. changing, turning etc.17 • Making a game with complex mechanics easy to start playing for beginners. • Illegal moves can be truly illegal (impossible).18

• Possibility to implement concealed handicap systems without interrupting the gameplay.19

• Flexible possibilities for pausing and resuming specific game sessions.20 • Setup of game states can be random and still guarantee an enjoyable

experience.21

• Players can exchange private information with each other without the others noticing.

• Negotiation about game rules must be made before play begins (with settings). When playing, rules are fixed.

• Possibility for private “subgames” on the personal displays.

Note that these qualities are essentially mentioned because technical circumstances make them possible, they do not necessarily add value to a game. As noted earlier, what is “won” here is generally more complexity in the game and less (unwanted) complexity for the players.

Interestingly, Salen and Zimmerman note that a board game named Stay Alive has some properties of a digital game. The game relies on a mechanical system which functions “semi-autonomously” from the players. This means that some of the

15 Eriksson, Peitz & Björk (2005): 5-6, Magerkurth, Memisoglu, Engelke & Streitz (2004): 5

16 Eriksson, Peitz & Björk (2005): 5, The game state is the exact position of all components of a game

at any time during play, Juul (2005): 60

17 Magerkurth, Memisoglu, Engelke & Streitz (2004): 5

18 This means that a game is not dependent on that the players stick to the constraints of a game

(they simply have to).

19 Eriksson, Peitz & Björk (2005): 5

20 Magerkurth, Memisoglu, Engelke & Streitz (2004): 5 21 Eriksson, Peitz & Björk (2005): 5

game’s exact rules do not have to learned by the players – the game itself handles their execution (players interact indirectly with the game).22

I find this observation by Salen and Zimmerman valuable, but I think using Stay Alive

is a very special case for an example. A game using some form of physical mechanism will by its nature shift parts of the handling of game states from the players to the mechanism itself. More interesting, in my view, is the fact that “digital traits” can be found in a wide variety of modern board games which works without any technical devices. To various extents, player moves in modern board games might be supplemented by what I prefer to call game moves. A game move is a move that is not made by any player but by the game itself as a reaction to the players’ moves or positions. This is very obvious in the popular board game Robo Rally – where lots of “automated” actions (game moves) are executed by the players as a response to their positions. Similar – but more limited – mechanisms can be found in the Swedish game Drakborgen (published in English as Dungeon Quest). I am quite sure the list could be made longer. I find it rather obvious that “computer logics” has sneaked into the board game flora and fauna as a forerunner of the games being computerized. Analogous examples exist in interactive literature (“Fighting Fantasy” books) and constrained poetry (text controlled by rules and algorithms) as favored by literary movements like the Oulipo.

Not only do I view these games with digital traits as consequences of designers being affected by how computers work – I believe that some features of these games has made both players and designers speculate about ways to augment them with computers.

Themed board games vs. abstract board games

An obvious division among board games is as previously mentioned between games with a fictional “theme” and games that represent nothing but themselves. There is not consensus on the importance or meaning of themes in games. Themes are dominating in the commercial era but is nearly absent in the “folk era”, but counterexamples exist. Chess is a folk game with at least a skeleton of a theme. Othello is a commercial game without the scent of a theme. Computer games are known for having well-developed themes, and are both loved and studied for this reason. Counterexamples like Tetris exist, though.

In board gaming circles, a “split” is generally recognized between two schools of commercial board games. These schools, though named after their places of origin, are above all identified by their relation to themes. In the American school, game mechanics is generally developed as a consequence of the theme chosen. Some of these games can be viewed as attempts at simulations of the fictional situations they represent. In the German school, the point of departure is game mechanics. Focus is at interesting gameplay through game mechanics that often are tested and calculated with mathematics. Themes are often applicated at a late stage in the process of game development, at some times – it seems – even by the publisher’s market department rather than by the actual game designer.23

22 Salen & Zimmerman (2004): 90

Accordingly, German games can be viewed as abstract games with a loosely attached theme. They are sometimes criticized for this reason.24 On the other hand, most board games can in sense be treated as abstract games. To excel in a board game, it is probably necessary to ignore the fictional theme it represents. This phenomenon has been dubbed “the rules of irrelevance” – anything that won’t help winning in a game is ignored.25 This rule certainly applies to Jörg Bewersdorff’s take on games. He treats abstract and themed games alike as mathematical systems, which he, rather entertainingly, describes in detail to help his readers become better players in their favored games. Bewersdorff, though, does not deny the importance of themes for the experience of playing a game. He just leaves it outside his discussion, which is centered around mastering the mechanics and dynamics of various games.26

On the other hand, I find it surprising that Gobet et al., in their own words dealing with the psychology of board games, do not mention themes, representation, simulation or fiction even once in their 270+ pages book “Moves in Mind”. Without openly declaring it, they have looked at a limited section of board games, all of them being two-player perfect information games. The majority of these (mostly folk) games are perfectly abstract, but at least two of the games analyzed in the book have a limited fictional dimension, chess (battle) and fox and geese (fox hunting geese...).27

Many board game players and designers, though, insist that themes matter. One view is that if fictional representations in a game were replaced with arbitrary representations, the game might actually be more difficult to play. Viewed as a simulation, the representations of a game can give cues to the players about their functions in the game. Accordingly, all the rules and mechanics might not have to be learned in detail from the start.28 Game designer frank Lantz explains how themes and mechanics can interplay:

Theme can provide the entry point into a complex structure whose rewards are deeply buried: first it’s all about the sword—the calculations are only there to conjure up the sword. Eventually the game becomes about the calculations and the sword fades away. Then there is the fact that representation can be used as a shortcut to embody a complicated structure that might otherwise be too much for the player to assimilate. If the red squares are “lava,” then the player won’t forget they are out of bounds. Why do the pieces in Tetris move from the top of the screen to the bottom? They’re bricks! Theme can add arbitrary limitations to the structure, and arbitrary limitations are often a good thing.29

Some game scholars have discussed this importance as well:

The rhetorical layer has the theme rules. This layer is optional in any type of game, but often highly necessary, especially regarding non-abstract games. As the layers of rules increase, from core up, so increases the degree that the actions within the game are

24 Faidutti (2005), Aleknevicus (2001), Aleknevicus (2004), German games (sometimes called

Eurogames) are also admired for their well-composed mechanics. The view that games are essentially a form of simulation, held by Frasca (2001, 2003) among others, fits better to the American than to the German board game category.

25 Goffman (1972): 19, Juul (2005): 63 26 Bewersdorff (2005)

27 Gobet, Retschitzki & de Voogt (2004), to their defense, the authors (for some reason) mainly deal

with how experts play board games, following “the rules of irrelevance” experts treat themes as irrelevant.

28 Hardin (2001) 29 Lantz (2004): 294-295

open to informal interpretations, i.e. such interpretations that are not directly referred to or governed by the rules. Implementing a theme, and soforth [sic] the rhetorical layer, to a particular game means taking advantage of methods (narrative, simulation, representation) that produce meaning on top of the formal structure of the game.30

Actually, research has proven that tasks are often not solved as “abstract” problems; Jiajie Zhang has proven that representations do matter. Using the classic logical problem The Tower of Hanoi (TOH), Zhang found that the representations used for illustrating the problem affects the attempts at solving the problem. When changing the material for TOH to (1) donuts (similar to the standard TOH disks on pegs), (2) oranges, and (3) cups of coffee, it was found that the oranges version were more difficult than the standard setup, while the coffee setup was easier. It appears as if representations are not only used for understanding a problem, they might be used for solving the problem as well. Changing representations might actually change the task31 Zhang has also shown how the game Tic-tac-toe can be changed into a game of choosing numbers and having them add up to 15. While the games are the same in abstract terms (a computer program might use the same algorithm for playing both) they are both experienced differently and played differently by players.32 Actually, games based on a high degree of simulation might become close to unplayable if translated to an abstract representation.

Countering (or rather supplementing) the rule of irrelevance, Juul has proposed a

rule of relevance. In every game there are some features that are of relevance even for the skilled player. If these aspects are ignored it might be impossible to master the game. Part of becoming skilled can actually be learning to distinguish between relevant and irrelevant features of a game. In chess, for example, the exact look of the individual pieces is irrelevant to playing, but the players must be able to distinguish knights from bishops or pawns.33

Another question regards the affectionate qualities of themes in board games. While the literature on computer games is flooded with analysis of “the representational layer” of the games, investigations of board games tend to shun this aspect. This is odd; board games with themes are apparently experienced as both interesting and stimulating by perfectly sane people. Board game enthusiast Greg Aleknevicus settles his “attack” on German games by concluding that even if the themes are loosely “pasted” on the underlying mechanics, this will always be better than having no theme at all, because “I prefer games with themes”.34

Formally, a game stays the same if the representation layer is removed or replaced by another theme. This, on the other hand, does not mean that it is experienced as the same by players.35

30 Järvinen (2003): 78 31 Zhang (1990)

32 Zhang (1997), shorter version in Juul (2005): 51-53 33 Juul (2005): 63-64

34 Aleknevicus (2004) 35 See Juul (2005): 199-200

Tangible vs. virtual, aesthetics of mind and simulation

Games with discrete game states are tied to rules rather than to material devices. Implementing board games in new media is thus often a rather straightforward task.36 On augmenting board games with computers, though, it has been some focus on preserving the tangible aspects of board gaming. For example, though dice are easily implemented on a computer, efforts have been made at keeping the “natural” physical dice and having instruments to read them. The aspects of rolling, touching and moving around (manually) is viewed as central to the board gaming experience. The designers have strived not to have the players caught up in “technology centered interaction styles”. The computer is supposed to keep track of game states and provide information and visualizations. As much as possible of what is connected to the players’ interaction with the game, though, is viewed as preferably handled by “tangible user interfaces”.37 Besides being supposedly affective by their nature, and supportive of social interaction, tangible user interfaces have some qualities that are innate in their physical nature. In these interfaces, there is no separation between input and output devices. Dice, for example, is both used for input (rolling) and output (viewing). In other words, representation and control are integrated.38

I agree that an approach enabling tangible interfaces is tempting and has many possibilities. On the other hand, people are playing computer games and online board games and seem quite happy with that. A mostly virtual/digital path must be possible. I previously stated some improvements that could be gained with a computer driven board game platform. Among these were possibilities for far more advanced game mechanics while keeping gameplay smooth and easy for the players. Normally, computer games are easier to get started with than most board games. In my view this is not due to the computer games being less complicated (I actually believe that the opposite is true). Instead, I think the rather limited form of input that can be given through a graphical user interface, and the games’ ignorance of irrelevant actions can be credited for this fact. While this is certainly not impossible to implement through a “tangible user interface” system, my view is that the less tailor-made the input and output devices – the more flexible the system. In a virtual system, game rules as well as themes can possibly be changed or even entirely replaced. So while “virtualizing” the board game experience might be negative from a tangible point of view, it might at the same time be positive from other perspectives.

Besides the tangible aspects of board games having an aesthetic value, it has been noted that people take advantage of their physical surroundings to handle logical problems. Scrabble players, for instance, are known to shuffle their respective letters physically to get a grip of the various combinations (words) that can be created. The physical environments, thus, are adapted relieving cognitive capacity for “the real deal”.39 Similar phenomena, though, has been observed in the playing of digital and even action-based games (Tetris).40

Returning to Scrabble, this game has been implemented rather effectively on computers. These implementations allow for the epistemic actions (good for thinking

36 Juul (2005): 49-53

37 Magerkurth, Memisoglu, Engelke & Streitz (2004): 1-4, Magerkurth, Engelke & Memisoglu (2004),

Mandryk, Maranan & Inkpen (2002): 1

38 Ullmer & Ishii (2000): 915, Magerkurth, Engelke & Memisoglu (2004): 3-4 39 Maglio, Matlock, Raphaely, Chernicky, & Kirsh (1999)

rather than scoring) often exploited by players of the original board game version. The “loss of cognitive relief” for the players when implementing board games on computers might in many cases be a matter of how this adaptation is done. While physical objects can be used in many ways – relating to their physical properties rather than to how they were intended to be used, virtual “objects” generally have a more limited set of properties and are to greater extent bound to their intended ways of use. This must be kept in mind when designing virtual products.

On the other hand, examples of “emergent gameplay” where players play games in ways that were neither intended nor imagined by the game designers also exist in computer games. Basically a positive phenomenon (players are allowed to be active and creative), emergent gameplay can sometimes be destructive to a game.41

That said, when having a gaming system that handles discrete game states and rules, it will indeed be possible to add “tangible” input/output units for specific or generic games – if desired.

Having concluded that there is a tangible level of board gaming that one can possibly do without, as well as an immersive level of computer gaming that is not necessary, I might be at risk of just listing aspects of gaming that it is possible to do without. Board games of the modern era are very varied in nature and, in my view, do not seem to be dependent on any core affective qualities.

Apart from these kinds of board game experiences (social, tangible) an important aspect might be what Marcel Danesi calls the aesthetics of mind. Danesi, dealing with logical puzzles, sees general similarities with puzzle solving and humor. Similar processes are at hand, the logics of jokes as well as puzzles are often to direct the attention of the target (audience, puzzle-solver) in the wrong direction. Realizing where to look and how to solve a puzzle brings forth a release of tension often experienced as a “kick”. Every puzzle, in Danesi’s view, has an “aesthetic index” which is inversely proportional to the complexity of the solution and the “obviousness” of its pattern. In other words, a “beautiful” puzzle has a simple solution which is difficult to see.42 Moreover, Danesi views puzzles as “miniature blueprints” of how functionality and memories are organized as patterns in the brain.43

These kinds of experiences certainly relate to gaming as well as to puzzles. The playing of board games has actually been described as “play consists of each player posing such a puzzle to the other”.44 There are, though, some general differences. Puzzles are generally designed to have a single solution. Most multiplayer games, including board games, rely on emergent mechanics where the players do the best to outsmart one another. They do not, of course, intentionally leave a witty solution to their opponents. If they do, this is a mistake.45 Accordingly; if a puzzle is analogous to a joke, a board game session might be viewed as analogous to a political debate. The participants strive to keep their act coherent and not to give away any easy points to their opponents, while at the same time watching their opponents’ argumentation to capitalize on their slips and mistakes. In other words, players

41 Juul (2005): 76

42 Danesi (2002): 226-227, this view is probably “poetic” rather than strictly neurological. 43 Danesi (2002): 233

44 Thompson (2000) 45 Juul (2005): 106

(including politicians) are doing their best for having the joke to be on their opponents rather than on themselves.

Experiences of the aesthetics of mind, though, might not be universal to games. Players and scholars interested in the “mind-type” experiences of gaming seem to focus not only on abstract or semi-abstract games, but on two-player games as well. Having more than two players seem to blur the mind-against-mind challenge that these groups look for in games.46

Of course, some players might have an illusion of control while their actions in many cases do not matter. Another type of player seems to be able to accept that the complexity of the game makes it hard to operate with a long-term strategy. The fact that a prosperous player might be attacked by all the others can also be regarded as an interesting game feature rather than as a design fault. While these players can certainly be affected by the social or tangible aesthetics of the game, I have a feeling that there is another force operating here as well. It can be some form of system-chaos fascination: the players are aware that the game states are discrete and that everything is handled “perfectly” by the game rules. These players might view a game as a form of simulation – a fictional world – in which the emergent developments are followed with great interest. A game might perhaps be described as having several aesthetic indexes. As well as having for example a social index, a tangible index and a mind index, a game could have a simulation index (or a complexity index). Simulation should not be understood as fiction in this case, the degree of simulation is depending on the number and range of the variables that enables it, more so than on the fictional or narrative qualities of the presentation. Simulation and fiction are, though, certainly connected.

Fixed vs. modifiable rules

One quality of traditional board games, in contrast to computer games, is that the rules are in the end agreed upon by the players. Carsten Magerkurth et al. have suggested leaving parts of the rule execution, at least in simple computerized board games, to the players themselves.47 Though I am not completely sure to what extent the authors envision this, I see problems coming here. My idea, as specified, is to allow complex game states, not keeping the games simple. Argument and agreement on rules is a feature in all gaming, but as Juul states, the predominant way to handle rule arguments is before the game begins. There is, preferably, agreement on how a game is to be played when the playing begins.48 If the settings of a computer game can handle rule variations in a flexible way, the problem of rule negotiation is basically solved. From my point of view, fixed and un-negotiable rules during play are the goal – this is partly what enables players to cope with complexity in games.

46 Thompson (2000), Gobet, Retschitzki & de Voogt (2004): 2, Bewersdorff (2005) stands out,

though, as he pays attention to strategies and tactics in all kinds of (non-skill) games.

47 Magerkurth, Engelke & Memisoglu (2004): 4 48 Juul (2005): 64-67

Private vs. public information

Surprisingly, Gobet et al. fail to see any general differences between card games and the abstract board games that are the focus of their research:

Card games do not seem to add a characteristic not already present in board or lottery games, and so far relatively few card games (mostly bridge) have entered the literature of cognitive psychology.49

Well, an obvious characteristic of most card games is that the players can only see their own cards, while in folk board games everything relevant to the game is basically visible to everyone at every time. In the modern board game era, cards and other features that enable similar effects have been introduced. In game theory (used mainly in economics) games where information is not public to everyone is called games of imperfect information, while games where everything is public is

games of perfect information. As everything is available in a game of perfect information game the game theorists consider these games (problems) easy and uninteresting.50 On the contrary, “mind type” scholars and players of board games often reject or ignore games of imperfect information, probably for being too difficult to analyze. As the knowledge of the game state is incomplete, there is not a rational best move at every time.51 Bewersdorff, though, view games of perfect information as the truly strategic games and games of perfect information as “combinatorial”.52 In a card game, casual players might find safety in the fact that chance is involved in the dealing of the cards; failure can always be blamed on bad cards. Players can also feel that the game states are so uncertain that they have no grounds for making an informed decision (this can be experienced as either good or bad). As mentioned in the introduction, private (imperfect) information is an aspect of gaming that has been hard to implement without loosing the social dimension of game sessions. In reality, games could perhaps be understood as games of imperfect information to various degrees. Many card games, as well as modern board games like Clue/Cluedo, are really about gathering information with the goal of attaining perfect information. Towards the end of a game of cards, a skilled player may at times have perfect knowledge of her opponents’ cards. The trait of imperfect information, together with the trait of social dynamics, might actually be “borrowed” from card games into board games. Dominoes and Mahjong, though, share the trait of imperfect information. Rather than being board games, though, these games (gaming devices) can actually be viewed as pre-paper card games.

As David Parlett has noted, more than just being games of imperfect information, card games can actually be viewed as being games about imperfect information. Besides that, Parlett argues against the assumption that games of imperfect information are less demanding than games of perfect information. Actually, while the most intellectually demanding games are often considered being two player

49 Gobet, Retschitzki & de Voogt (2004): 2 50 Davis (1997): 8-9

51 Thompson (2000), Gobet, Retschitzki & de Voogt (2004)

52 Bewersdorff (2004): ix-xii, this is obviously in dept of Bewersdorff’s analytical “outside view” on

games. As everything is known in a game, making a decision is only a matter of choosing the best move (the right combination). A third element of gaming in Bewersdorff’s categorization is chance. Games can certainly combine the three “causes of uncertainty”: chance, the number combinations and moves, and imperfect information.

board games like Chess and Go, some games of perfect information involve no decisions at all (Snakes and ladders is one example).53

The perfect/imperfect division of games is in a way a bit mathematical and abstract – it does not always relate to actual games and game sessions very well. When used by Juul, I find it a bit limited a categorization. Juul finds most computer games to be games of imperfect information, as things (information) are hidden from the player’s view.54 This is basically correct, but it does show that this division might not be that useful when looking at computer games. To separate public from private information

in any game might be a more rewarding strategy (than to identify perfect and imperfect information games). As Salen and Zimmerman notes, Celia Pearce presents a better categorization of how information is treated in games. Sadly, she blurs the categorization by stating that information known to all players includes the rules of a game.55 The rules of a game are in a way a factor not really related to how information is treated in a game. Players may know or not know the rules of any game. Salen and Zimmerman modify this error in Pearce’s model. Thus information in games might be distributed between:

• Information known to all players • Information known only to one player • Information known to the game only • Randomly generated information56

It is quite easy, though, to think of more categories (variations of the above): • Information known to some but not all players

• Randomly generated information from a set known to all players • Randomly generated information from a set known by the game only

The list could certainly be made longer. Also, when games are run by computers, information known by the game really becomes a bit more complicated matter. While the cards that remain in the deck when cards are dealt to the players in a card game are in a sense “known to the game”, this information is not really acted upon or treated in any way. Besides that, in a computerized card game with a computer program as opponent, there must be a separation between what the game knows and what the virtual player knows. The virtual player, accordingly, must be treated as any player. Also, in a virtual world game, virtual AI driven characters does not necessarily share information with the game. They are, in a sense, unique entities. As an example, in Pac-Man the game will always know the position of the player (or the game would collapse). The ghosts (Blinky, Pinky, Inky and Clyde), though, have their own unique algorithms for the tracking the player. Virtual characters could of course be treated as players, but their goals and scope are often much more limited than that of actual game players.

I have included virtual characters in this discussion because this is one feature which games for my platform could include to separate themselves from traditional board games. Having independent “emergent information units” in a board game might enable new forms of gameplay.

53 Parlett (1991): 18-20 54 Juul (2005): 59-60 55 Pearce (1997): 422-423

Connected to private information is the randomness in game setup as is seen in card games as well as in many modern board games. By shuffling and dealing random cards, tiles or other game entities – every game session can in a way be seen as a completely new game. This is contradicted in most classical board games, where the setup is fixed.57

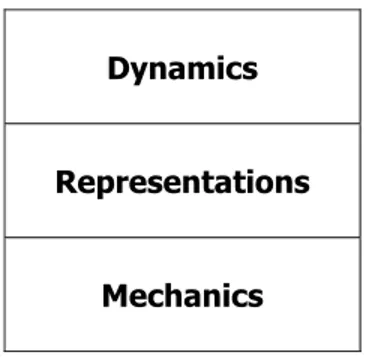

Rules, mechanics

Though the concept of game mechanics is used by designers, players and reviewers of (mostly) board games, it does not seem to be widely used by scholars. As noted earlier, a considerable number of scholars studying games deal with the representational aspects of (computer) games rather than the interactive “game-play” aspects. “The ludological scholars”, including Juul and Salen & Zimmerman, seem to focus on rules rather than mechanics. This might be due to that fact that they, though often using board games as examples of their theories, focus on

computer games. 58 As a matter of fact, game mechanics might not be a very useful concept when dealing with the plethora of “entertainment forms” that go under the name of computer games. As Juul and Lindley, among others, note, the concept of computer games goes beyond what previously has been categorized as games.59 The few board game scholars around (generally focused on the cognition or the history of games) might occasionally use the term, but has not – to my knowledge – delivered any attempts at a definite definition of the concept. Gobet et al. talks about game purpose, move characteristics and piece characteristics, which might be valuable for dealing with folk classics like Chess or Go, but clearly not suitable when applicated to Monopoly (the properties and the positions of the pieces are not really that interesting in this game).60

Interestingly, about the only “direct” definition of game mechanics I have found is in a short article on computer-augmented (board) games by Sus Lundgren and Staffan Björk:

A game mechanic is simply any part of the rule system of a game that covers one, and only one, possible kind of interaction that takes place during the game, be it general or specific. A game may consist of several mechanics, and a mechanic may be a part of many games. The mechanic trading, for example, simply states that during the game, players have the possibility to trade with each others. What they may trade, and how, and when, is stated in the specific rules for each game using this mechanic. Other examples of game mechanics include bidding, negotiation, story-telling, roll and move, and role-playing.61

57 Parlett (1991): 15-18

58 Juul (2005), Salen & Zimmerman (2004), both books has “rules” in its title and do not use the

concept of game mechanics. Designers of computer game occasionally use the concept (without giving much of a definition), see i.e. Ryan (1999), Adams (2001), Johnson (2001) and Lopez (2006).

59 Juul (2005), Lindley (2005)

60 Gobet, Retschitzki & de Voogt (2004): 238-239. Game historian David Parlett comes with no

in-depth explanation of the concept, but delivers a beautiful synonym, ludeme (1991: 61-64, 1999:9) apparently coined by game researcher Alain Borveau (Depaulis 2004)

61 Lundgren & Björk (2003): 4 (my italics, for readability). In Lundgren’s MSc Thesis (2002) the

For examples of actual game mechanics, Lundgren & Björk refer to the Board Game “fan site” BoardGameGeek. The site features a list of 41 distinctive mechanics that are found in board games (see appendix 1).

The list can, arguably, be disputed. It is hardly complete and it is doubtful if it actually could be. BoardGameGeek is a user-edited site. The “mechanics” may cover a wide variety of functionality that operates on different levels as related to rules and actual gameplay. Mechanics like rock-paper-scissors, set collection, tile placement,

trading and trick-taking probably sounds reasonable to most gamers, while mechanics like line drawing, singing and crayon rail system are perhaps a bit odd and at least highly specialized. Yet others, like memory and pattern recognition, are more like useful skills than actual mechanics as defined by rules. Finally, for my purposes, some of the featured mechanics refer to the physical devices used when playing rather than the immaterial mechanical functions they control (e.g. rather than dice rolling, randomizer would be preferable). The classification of mechanics of the games featured in the BoardGameGeek database62 is neither very rigorously implemented – many games, especially abstract classics, are labeled as “not applicable”. Anyway, my impression is that the mechanics listed on the site, and their descriptions, are valuable for both understanding and developing games.

Lundgren has made an attempt at grouping some of these mechanics into four main families: Human-human interaction mechanics, Influential mechanics, Condition mechanics and Gathering mechanics. 63

Basically, I find Lundgren’s families of game mechanics valuable and rather unique. I would, though, like to make some changes. The family of influential mechanics is especially problematic. Lundgren states these are mechanics that “influence the board, the gameplay or other players” – which, I would say, could be said about any mechanic that really matters in a game. Besides that, I would like to change the order of listing the families, going from “hard” (rule driven) to “soft” (player driven).

Conditional mechanics states the basics of a game, goals, sub-goals64, the properties of the components and how the turns are executed.

Game state manipulation mechanics (action mechanics?) are the ways players interact with a game. These are of necessity influenced (governed) by the conditional mechanics. Lundgren’s influential mechanics can be found here, including its subgroup – moves. The “gathering” family is found here as well. Some autonomous sub-families might be identified. These might be: moves, resource acquisition

(“gathering”), board-directed actions and player-directed actions. I would definitely place “Rock-paper-scissors” in this category rather than in the human-human category (which Lundgren does). Rock-paper-scissors can be viewed as a form of “combat resolution”. Other forms are “taking out by moving in” (Chess) “dice rolling” (Risk), battle cards and “stronger beats weaker” (Stratego). Combat resolution might in fact be viewed as a separate category (or sub-category) of the game state manipulation family. Arguably, the sub-division of this family is not an easy task.

62 Apparently over 27.000 games are included in April 2007. Slightly different editions of the same

games probably included in this number, yet still – it’s a lot of games.

63 Lundgren (2002): 71-72

64 The “goal mechanics” listed has actually more of a sub-goal character (you don’t win by collecting a

Social dynamics mechanics comprises events and actions that emerge between the players, outside the discrete game states handled by the game. These are at least as important as the other families, and it is important that this dimension isn’t lost when games are transferred to a digital medium (as it is with online board games). As mentioned above, I would take Rock-paper-scissors out of this category. Any “psychological warfare” connected to that form of combat, on the other hand, clearly belongs in this category. Trading and voting (in the mechanical sense) does not belong here, but attempts at persuasion or threats preceding those activities do. The dynamics of this category is likely not to be “hard-coded” into the rules of the game, but rather to emerge during play.

I do not feel that this is “the definite” game mechanics definition, but clearly it is a useful construct. A quite interesting fact is that some of these are strongly governed by rules, others emerge as players interact within the rule system; while a third category emerges with the players’ interaction outside the rule system (e.g. “negotiation” or “temporary partnerships” can occur in the playing of many gaming without these features being supported by the rules).

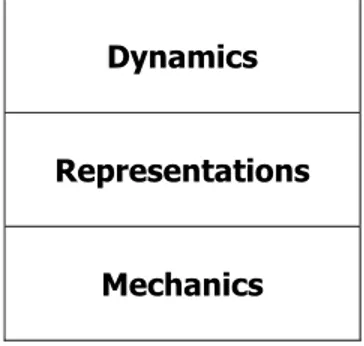

Raph Koster, as it appears, chooses a slightly different way for naming these phenomena. Mechanics, in his view, are the rule bound “ludemes”65 (type 1 and 2), while the human-human type ludemes simply are called “dynamics”. 66 This is understandable, but clearly a designer stance rather than player ditto. From a player point of view it is not really that important, or obvious, what roots the ludemes have. A powerful trait of the concept of mechanics is that it is widely used by players. Lundgren and Björk list a number of additional mechanics they have found in computer-augmented games:

1. Computerized clues

(The computer controls the distribution of clues) 2. Espionage

(Players can get information about another player’s resources, but the computer regulates the level of accuracy of the information)

3. Pervasive gaming

(The game is played continuously even if intertwined with daily activities such as working or sleeping)

4. Superimposed game world

(The game is superimposed on a physical environment which is still inhabited by non-players) 5. Secret partnerships

(Players are divided in teams without knowing with whom)

6. Body-mapped avatar

(A virtual character mimics the players’ actions) 7. Player-undecidable conditions

(The computer keeps track of conditions which are very hard, or impossible, for players to decide the state of, and the computer uses this information to steer gameplay)

8. Encouraged face-to-face information exchange

(The game makes it impossible for players geographically separated to share information through the game medium in order encourage [sic] players to physically meet)

9. Implicit player input

(Players affect the course of the game by sending input to biosensors attached to them, meaning that a critical element of the game is body control)

65 I use the term ludeme in this discussion as it is neutral regarding to the opposing stances. 66 Koster (2005): slide 12

10. Additional mechanics

(Examples of additional mechanics are Anonymous Trading, Active Board, Complex Commodities Prizes, Complex Phenomena, Active Dice, Active Surfaces, Active Tiles and Secret Bidding) 67

While the focus of my project is a form of computer-augmented gaming as well, some of these mechanics can be ruled out as irrelevant for my purpose. These are

pervasive gaming, superimposed game world, encouraged face-to-face information exchange and implicit player input. These are all associated with very specific technology and imply a gaming experience quite far from a traditional board game session. The remaining mechanics, anyway, are good examples of new possibilities that emerge when games are enhanced with computers. Computerized clues,

espionage and secret partnerships are actually the kind of mechanics I had in mind when I started this project.

The mechanic that Lundgren and Björk call “Player-undecidable conditions” is a special case. This implies, as I see it, balancing the system (the game) as a somewhat closed system. This is contradictive of board games where players, to a certain extent, have complete overview of the game states. Even if some game states are hidden (other players’ resources, remaining cards in deck etc.) the players actually know what they do not know. Board game players are used to having a complete understanding of game rules, this might actually be a general trait of board games. I have not seen anyone complaining about this fact, actually there has been some discussion in the computer game business that goes in the opposite direction. Strategic computer games are sometimes viewed as suffering from “the black box syndrome”; the players lack access to the internal workings of the game system. This might make the games more difficult to both learn and master as well as depriving the player of the “mechanistic pleasure” that lies in the appreciation of the rules and mechanics of a game.68 That said; methods for balancing gameplay and ensuring pleasurable experiences (by hidden mechanisms) are interesting – and rather obvious – possibilities to consider when augmenting board games with computers. I my view, some of the most interesting mechanics in Lundgren and Björk’s report are hidden under the label “additional”. These are (as previously stated) Anonymous Trading, Active Board, Complex Commodities Prizes, Complex Phenomena, Active Dice, Active Surfaces, Active Tiles and Secret Bidding.

Lundgren state some of these mechanics as “entirely new”, while others are “computer-augmented” (improved). I would rather say that it is a continuum – most of these mechanics are to some extent possible to realize without the use of a computer.69

Lundgren and Björk conclude that the idea of a game as “an entity put together by a number of smaller components” (mechanics, ludemes) is very valuable. They find it somewhat problematic that the unique mechanic components (ludemes) can not completely be identified and separated from the rest of the game (the ludic system), including the other game mechanics involved. Anyhow, for discussing, analyzing and making changes to a game – they find the concept of game mechanics a useful tool.70 In a later work in cooperation with Jussi Holopainen, though, they conclude that the concept is (among other faults) too loosely and self-contradicting defined in the available literature. Instead, they propose the use of another concept, game

67 Lundgren & Björk (2003): 7-8, a rather similar list were given in Lundgren (2002: 73-82) 68 Salen & Zimmerman (2004): 88-89, 179-180; Larsen (1999)

69 Lundgren (2002): 73-82 70 Lundgren & Björk (2003): 9

design patterns.71 This approach is borrowed from an article by Bernd Kreimeier, who suggests the use of the “design pattern” method in game design. Design patterns can be described as (conventions for describing) “recurring decisions within a given context”. Patterns are widely used in fields as architecture and object-oriented programming – but in the game design field the notion of patterns is not well known.72 Björk, Lundgren and Holopainen largely follow the path laid out by Kreimeier (they even borrow his examples). At one important point, though, they depart from Kreimeier. In their view, Kreimeier has not adjusted the concept of patterns to the domain of game design. In other fields, design patterns are often used as a problem solving tool. That comes, of course, with the fact that design is viewed as a solution to a problem (a bridge is a solution to the problem of getting people over the water, etc.). Games are a completely different matter as, many times, problems are actually what is desired (by the designer).73

In the model, recurring design patterns are described with a template by specifying their unique characteristics: name, description, consequences, using the pattern and

relations.74 Obviously, this is a more elaborate form of description than the loosely defined “mechanics model”. Besides that, the authors stress that a pattern is not just present or not present in a game; it can be present in a game to a certain degree.75 In a subsequent work, Björk and Holopainen present a list of over 200 game design patterns that they have identified by looking at a large number of computer games. The description of the individual patterns is rather detailed, consuming about a page each. The authors group these patterns into a number of distinct categories:

1. Patterns for game elements

2. Patterns for resource and resource management

3. Pattern for information, communication, and presentation 4. Action and events patterns

5. Patterns for narrative structures, predictability, and immersion patterns 6. Patterns for social interaction

7. Patterns for goals

8. Patterns for goal structures 9. Patterns for game sessions

10. Patterns for game mastery and balancing

11. Patterns for meta games, replayability, and learning curves

Obviously, these are a wider variety of phenomena than the board game mechanics listed earlier. This, of course, is an effect of the plethora of sensations and activities that appear in computer games. Besides that, the scope for what can be considered a game design pattern is wide: apparently every design decision except the strictly aesthetic is included. On the other hand, patterns associated with traditional board games are apparently dropped, in cases where these patterns have not “survived” the evolutionary quantum leap into computer games.76

71 Björk, Lundgren & Holopainen (2003): 3-4 72 Kreimeier (2002)

73 Björk, Lundgren & Holopainen (2003): 4, See also Björk & Holopainen (2004): 33-34

74 Björk, Lundgren & Holopainen (2003): 5-7, Kreimeier (2002) used the characteristics name,

problem, solution and consequences in his model.

75 Björk, Lundgren & Holopainen (2003): 8 76 Björk & Holopainen (2004)

Emergent vs. progressive

A general division in games described by Juul is between open-ended strategic games,

games of emergence, and linear games, games of progression. Typical for games of emergence are simple rules yet complex gameplay (this often seems to be a general correlation; complex gameplay emerges from simple rules). Chess and Go are prototypical games of this category. Games of progression are common among computer games, where games often consist of a series of obstacles that the player must overcome. According to Juul, games of progression are relative newcomers in the flora of games, in his view the text based adventure games of the seventies are the first examples of this type of games.77 I doubt the validity of this, as any puzzle

game could be considered a game of progression.78

It seems to me as if the high level of fictional content in computer games can work as a frame for a series of puzzles, enabling complex games of progression. Imagine a series of puzzles: a crossword, Rubik’s Cube and a Sudoku. These solved after one another would hardly be experienced as a game without some kind of frame tying them together. In a way, this is what a progressive computer game like Myst or Max Payne does, by means of fiction.

Board games are inherently games of emergence, and in my view this is the way to go when developing new board games. Emergent games generally have a higher degree of re-playability. Mixed forms, though, is also possible.79

The social dimension – human dynamics

Surprisingly, the academic literature on board games (which is scarce) does not really deal with human dynamics related to the playing of games. This in part must be in debt of the history of board gaming, where two player “mind games” have been the rule. Gobet et al. for example, ignores, or are perhaps even largely unaware of the fact that multiplayer board games exist – and are the rule in the modern era.80 Parlett traces “four-handed” chess variations back to 11th century India – but is exclusively negative of the concept, dismissing these variations for being “gambling games” rather than games of intellectual conflict. In his view, four players playing in teams of two would be ok – as that would make the game a fair battle of minds. When everyone is battling everyone, partnerships will occur – and the best player might be taken out by an alliance of weaker players. Parlett finds situations like this so problematic that he doubts “the essence of the game”.81

The fact that mister Singh and his friends might actually have had a good time playing Chaturaji (Indian four-handed chess) does not even seem to occur to Parlett. Most players having enjoyed Risk would probably agree on the opinion that the making and breaking of agreements is a main ingredient in the fun of the game. Enthusiasts of modern games generally appreciate these kinds of dynamics:

77 Juul (2005): 72-82 78 See Crawford (1982): 10 79 See Juul (2005): 82-83

80 Gobet, Retschitzki & de Voogt (2004): 2

81 Parlett (1999) 325-330, Thompson (2000) is another writer which goes against multiplayer games,

Perhaps the ultimate games in terms of player interaction are "alliance games". These are games that virtually require the players to form teams and factions in order to do well. [...] In fact, one could argue that the rules themselves are somewhat beside the point other than to enforce a framework in which the players struggle amongst themselves. Interaction is the game. The clever move is not that Italy managed to capture Marseilles but that Bob was able to conspire with Al so effectively without Carla being aware of it.82

Apart from alliances, of course, a lot is going on around a board with players. Unfortunately it has not been widely studied. Ervin Goffman, in 1972, concluded that when a game is played, besides a game with players – what is going on is also a

gaming encounter with participants. The participants in the gaming encounter might be onlookers as well as players. What happens among the players in the game is what affects the game states – but what happens around the actual game (in the gaming encounter) might be of equal or at times even more importance to the overall experience. Participants in a gaming encounter, actually, can interact both

within the game (as a player in the game) and outside the game (as a participant in the gaming encounter).83

It seems as if when these kinds of social dynamics related to gaming have been studied, this have been done with children in developmental psychology or with people from distant corners of the earth in social anthropology.84 One family of games seems to be studied more than any other as a social experience – the Mancala games of Africa. Interestingly, the playing of these games is an unusual setting for a two-player “mind game”. Although the game is cognitively demanding (“long” rather than “deep” according to Parlett), it is played at great speed with onlookers giving advice to an extent where it might often be hard to judge who is actually playing the game and who is not.85 Otherwise, the social dynamics of board gaming seem to accumulate with the number of players – the more the merrier (and the harder to play strategically).

If board games (evidently) have a history of two-player games, card games are a different matter. Parlett, though negative towards multiplayer variations of Chess, has a positive view on multiplayer card games:

Yet another attraction of card games is that they are playable by any reasonable number. For centuries they have proved a uniquely sociable activity against the alternatives of two-player games requiring exclusive concentration, such as Chess, Draughts, and Backgammon, or dice, which appeal almost exclusively to male gamblers and cannot, with the best will in the world, be described as ‘sociable’.86

Card games may in many ways be viewed as a precursor of the modern board games – more so, in some ways, than the traditional board games might. A card game session has some of the sociable-competitive ingredients that are seen in modern board games. Cards are actually – I dare say – an ingredient in a majority of the board games of the modern era, many of them supposedly even incorporating mechanics borrowed from card games.

82 Aleknevicus (2003) 83 Goffman (1972): 33-38

84 See for example Juul (2001) and Juul (2005): 9-12, 85 Parlett (1999): 217-218