Communication for Development One-year master

15 Credits Spring 2018

Supervisor: Oscar Hemer

Participatory communication in Publicly

Funded Projects

Sida - theory and practice in Guatemala

2 Abstract

The aim of this essay is to investigate how development projects, funded by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, include communication in the project cycle and if it affects their results. The research will take place in Guatemala and will be based on a comparative study in which the program evaluations conducted by the Swedish Embassy, responsible for distributing the funding, will be used to choose two projects: one regarded as successful and the other unsuccessful. By interviewing and conducting surveys with staff members from the embassy, NGO personnel that worked with the project as well as community members affected by the projects, the aim is to get a full picture of the projects themselves as well as the different personal experiences of the projects to allow for a discussion concerning communication for development, participation and governmentally funded development work. The conclusion is that there does not seem to be a defined way in which Sida-funded projects include participatory communication in the project cycle even though it is mentioned and discussed in connection to a project. The comparison of the two local initiatives indicate that defining a method and tools which allows the Embassies to better control and structure in terms of participatory communication are likely to increase the

sustainability of the projects.

Keywords: SIDA, Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency , communication

for development, ComDev, Guatemala, development projects, project evaluation, participatory communication

3

Table of content

1. Introduction ... 5

1.1 Introducing the topic ... 5

1.2 Research problem ... 5

1.3 Research question ... 6

1.4 Research design and objectives ... 6

1.5 Local context and background ... 6

2. Theory ... 8

2.1 Earlier approaches to development cooperation ... 8

2.1.1 The modernization paradigm ... 8

2.1.2 The dependency paradigm ... 9

2.1.3 The participatory paradigm ... 9

2.2 The basic principles of participatory communication ... 10

2.3 Reasons and arguments why participatory communication should be implemented in development work ... 11

3. Literature review and existing research ... 13

4. Methodology ... 16

4.1 Issues and limitations ... 18

5. The Project: Rural Producers accessing markets and increased food security in Guatemala ... 20

5.1 Local circumstances ... 20

5.2 The project: Circumstances and goals ... 21

6. The project’s stakeholders ... 23

6.1 Sida and participatory communication ... 23

6.2 The Swedish Embassy in Guatemala ... 24

6.3 Oxfam ... 26

6.3.1 The method WEL ... 27

6.4 CICAM ... 29

6.5.1 The Cooperatives ... 30

6.5 AMUPAVET ... 31

6.6 Granja Avícola Maya Kaqchiquel ... 32

7. Discussion ... 36

7.1 The group dynamic ... 36

7.2 Ownership ... 38

4

7.4 Circumstances ... 42

8. Conclusion ... 44

9. References ... 46

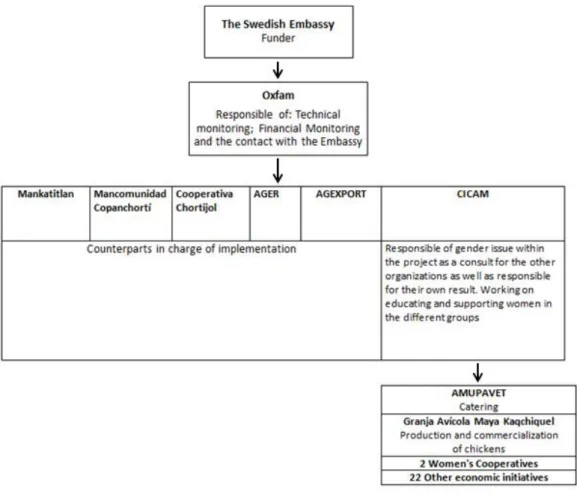

Figure 1. Project structure ... 22

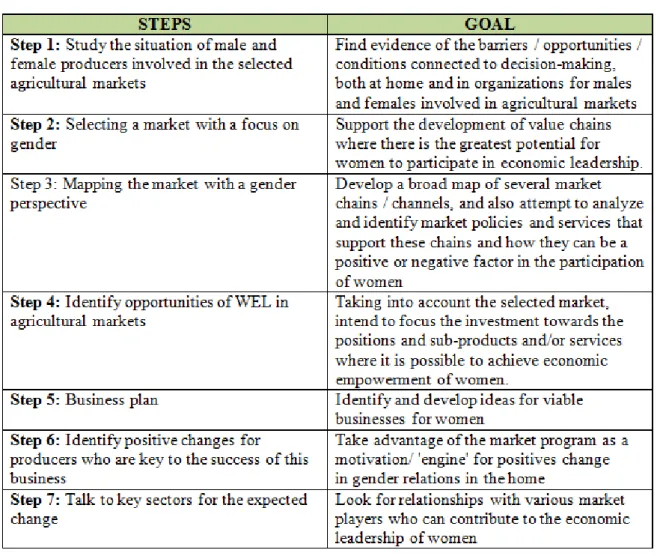

Figure 2 Steps of method WEL ... 28

5 1. Introduction

1.1 Introducing the topic

The purpose of all development work is to help people in different ways (Mefalopulos, 2008:218) according to the participatory communication approach there is an important connection between participation, communication and results in development projects (Bessette, 2004). According to researchers, failure to develop suitable communication tools, particularly methods to engage stakeholders, is one of the major reasons why development projects are unsuccessful (Mefalopulos, 2008:218) but yet there seems to be a long way to go before all development projects and Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) adapt their work to this approach (Bessette, 2004).

According to the World Bank, projects that engage and involve beneficiaries have a 68 per cent success rate while projects without this intention have a success rate of only 10 per cent (Mefalopulos, 2008:218). The costs of not including participatory communication, such as time delays, monetary loss, project cancelations and negative impacts on trust, reputation and goodwill, becomes clear when governmental and institutional efforts fail to achieve their objectives (Mefalopulos, 2008:215). But, ultimately the cost of these failures are borne by the ones who misses out on the benefits that a well-functioning development program could bring in terms of improving the quality of their lives (Ibid:216).

Sweden, through the Swedish International Development Agency (Sida) and ultimately many of the Swedish embassies around the world, spend about one per cent of its BNI on its development aid budget out of which the Swedish Embassy in Guatemala received 170 million SEK per year (between 2008-2016) (Regeringskansliet, 2018).

1.2 Research problem

There has been an increased focus on communication at the Embassy recently, but it seems that this focus is mainly connected to its own social media which only has a limited impact on development results as communication in development should go beyond using technologies (Servaes & Malikhao, 2012).

Participatory communication might be in essential in Swedish development work, both in regards to the Embassy in Guatemala and its NGO counterparts, but if their communication is limited to reporting results and promoting the image of the organization and its work in reports and in social media, it might have little impact on the actual projects. To get a better

6

understanding of the methods used, this thesis sets out to explore how the development work is conducted and the methods used to reach the objectives.

1.3 Research question

For the already mentioned reasons, this thesis will investigates how development projects in Guatemala, funded by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, include participatory communication in the project cycle and how it does affect their results.

1.4 Research design and objectives

I will base my research on interviews and data connected to two local initiatives included in an Oxfam-led project called “Rural producers accessing markets and increased food security in Guatemala” taking place between 2013 and 2015. The project was funded by Sida.

As the Embassy does not lead projects on the ground but rather approve proposals, distribute funding and monitor the organizations and the projects they support ("Interview Embassy Representative", 2017). The study will thus include interviews with Embassy staff, representatives from the organizations involved as well as the women participating in the local initiatives to allow an understanding of the whole lifespan of a project: From Oxfam‟s project proposal and the Embassy‟s approval, to the involvement of the participants and the results and evaluation of the project to see if, when and how they discuss communication and participation.

The aim is to investigate how the development cooperation functions on the ground, and the hope is that this type of deep analysis of how participatory communication is integrated could reveal the areas in need of modification, thus increasing the positive impact of the initiatives.

1.5 Local context and background

Guatemala has a history of deep inequalities and discriminatory social structures dating back to the Spanish colonization. More than 20 years after the 36 year long internal armed conflict that ended 1996, the country is still healing and the democratic institutions are not yet fully consolidated.

Fifty one per cent of the population belongs to one of the 23 different indigenous groups, and a majority of the indigenous population is very poor and often faces discrimination (ibid). During the armed conflict several massacres of civilians took place, and at least 200 000 civilians, 83% from indigenous groups, are believed to have been killed or „disappeared‟. The government is believed to be behind at least 93% of these killings ("UN Truth Commission:

7

Guatemala", 2017). The country‟s history has left deep marks and many of the reasons behind the violent conflict are still present in the Guatemalan society; the high risk of violence, lack of trust in the government, a weak legal system, low tax outtake as well as social and economic inequalities (Sida, 2015).

Half of the country‟s income belongs to ten per cent of the population while the poorest tenth of the population only receives one per cent of the income. Moreover this group lacks personal security and access to public institutions. There is also an unequal access to land (weeffect.se), leaving indigenous people to seek wage labor through internal and external seasonal migration (Minority Rights Group International, 2008). The presence of discrimination and exclusion based on gender, social status, age and ethnic group also significantly hinders the exercise of human rights, particularly those of children, women and indigenous populations (UNICEF, 2007).

There has been a vast increase of NGOs in Guatemala, particularly after the end of the armed conflict. It is believed that there are two important reasons behind this: The first is connected to the major Latin American initiative led by the Kennedy administration targeting aid to support community cooperatives and modernization projects. The second was the extensive increase of community organizing initiatives in rural, indigenous communities. The Catholic Action led by foreign-born priests successfully competed for international funds through a grassroots style of non-governmental action, with small, community-based organizations, usually receiving guidance from foreign advisors. The earthquake in 1976 also led to an increase of international NGOs. The expansion of the NGO sector continued growing towards the end of the 1980s after having been hindered by the armed conflict and increased further after the signing of the Peace Accords in 1996 (Rohloff, Díaz and Dasgupta, 2011:427). The Swedish presence in Guatemala reflects this process beginning already in the 1970‟s (Regeringskansliet, 2014).

The reality of the post-Accords period is a steady weakening of the state and an increased flow by transnational institutions into the national political economy, echoing the post-1996 era of neoliberalism which gave the NGO sector free reign, without any practical oversight. As a consequence of this change there is now a patchwork of NGOs in the country; estimates suggest that they exceed 10,000 (Rohloff, et al, 2011:427-428).

During the first ten years the Swedish development cooperation was mainly focused on supporting the victims of abuse, and human rights continues to be a prioritized aspect of the Swedish economic support. Sweden were active in the peace negotiations between the

8

government and the guerrilla groups which led to the signing of the Peace Accords in 1996 (Sida, 2015) and Sweden has since then given political and financial support to the transitional justice processes (Andrade et al., 2016). As many Embassies in Guatemala have closed and others decreased their development funding, Sweden is currently the country‟s second major donor (swedenabroad.com).

2. Theory

2.1 Earlier approaches to development cooperation

Since World War II, there have been three theoretical approaches dominating the development context and, consequently, the field of development communication: The modernization paradigm, the dependency paradigm and the participatory paradigm (Mefalopulos, 2008).

2.1.1 The modernization paradigm

The modernization theory explained development problems with cultural and information deficits founded in the existence of a traditional culture. Traditional culture hindered development, making economic assistance ineffective as it impeded the countries‟ move into modernity. Modernization theory sees ideas as “the independent variable that explains specific outcomes” and development communication focused on changing ideas as it would lead to a change of behavior. Through media, innovations and culture it would be possible to transfer Western modern values and information which would lead to (a Western model of) development (Waisbord, 2001:3).

This idea led to „communication‟ meaning transmission of information giving rise to two communication models: the Shannon-Weaver sender-receiver model and the propaganda model which focused on mass media as the solution to changing attitudes and behavior. The idea of these models was that information is transferred from a sender, mainly through media channels, to a receiver in a unidirectional way (ibid:3). The influential “diffusion of innovations” theory explained development communication as transferring an idea from a sender to a receiver, intending to change the receiver‟s behavior. Diffusion research found that communication and culture are better motivators for change than economics especially when adopting new methods within agriculture for example. And, even though media was

9

considered important for increasing awareness, interpersonal communication and relations were crucial to achieve change and channeling and shaping opinion (ibid:4).

In the 1970‟s, modernization theory was the dominant paradigm of development communication. A revised diffusion approach viewed development as a „participatory process of social change‟ and communication moved away from the idea of transmission and persuasion to a „process by which participants create and share information with one another in order to reach a mutual understanding‟ (Rogers in ibid:5).

2.1.2 The dependency paradigm

The dependency paradigm considered the problems of development to be created by an unequal distribution of resources produced by the global extension of Western capitalism. It was external factors and the countries integration in the world economy rather than internal issues which caused dependency. The dependency theorists claimed that the modernization theories‟ focus on mass media as a tool for diffusion of information ignored the important issues connected to who owned and controlled the media. As the urban elite who controlled the media would have no interest in promoting social goals or development, the dependency theorists‟ criticism focused on how modernization theories ignored the relation between media structure and content (ibid:16).

The development problems were political and not caused by a lack of information, and as such the solution had to be political: social change was required to transform unequal distribution of power and resources (ibid:17). Besides external factors, internal, unequal structures within countries created dependency: land distribution, poor public services etc. Consequently, development programs focusing on individual factors failed as they did not address these structures (ibid:16).

2.1.3 The participatory paradigm

Participatory theories turned away from the modernization paradigm as it was considered to focus on a top-down, ethnocentric and paternalistic view of development in which development was too associated a Western vision of progress. The criticism towards previous approached focused on the lack of involvement of local people in the design, preparation and execution of development interventions. Consequently the people who were affected by an intervention were viewed as passive receivers while experts and policy makers made all the

10

decisions. These previous, top-down approaches assumed that the recipients of an intervention lacked knowledge or an understanding of issues while governments and agencies were correct in theirs. As recipients had little say in projects, they did not feel ownership of the intervention leading to them never becoming sustainable. Not having a say in what would occur in their life or in their area could also cause a sense of disempowerment (Waisbord, 2001).

To create sustainable projects, participatory theorists and practitioners believed that it was necessary to take the context and culture into considerations – all communities are different and as such a one-size-fits-all approach would never work as local knowledge and local participation is vital to achieve change. Local communities had insights and knowledge that was equally important as the knowledge of „experts‟, so moving away from a top-down, unidirectional type of communication towards an equal, horizontal process of dialog and participation would, lead to an increased sense of ownership of participants through sharing and reconstructing experiences. Consequently, community members and not the experts should be in charge of the decision and production processes, and participation had to be present in all stages of development projects (ibid). Another factor is that economic growth might not be the focus of development, but rather other social dimensions needed to ensure meaningful results in the long run (Mefalopulos, 2008).

A sustainable development approach was believed to have a human-centered, face-to-face approach in which interpersonal communication was much more important than mass media. Development workers should act as facilitators of dialog instead of just transmitting information (Waisbord, 2001). As change does not happen when communities are not actively engaged in development projects and lack a sense of ownership, the role of the development worker also includes encouraging participation in decision-making, implementation, and evaluation of projects (Mefalopulos, 2008).

2.2 The basic principles of participatory communication

Even though decision- and policymakers are increasingly „charmed‟ by participatory and bottom-up approaches, there is still a common belief among NGO‟s that top-down planning, mainly based on the use of (old and new) media, remains an effective way to „deliver‟ social change (Servaes, 2012). But research has shown that this type of information available to the public in impersonal media like radio and television has relatively little effect on behavioral changes (Servaes, 2008).

11

Servaes (2008) also adds that the aim of this type of social process, and the communication it entails, is to reach consensus concerning actions that includes the interests, needs and capacities of all involved. Communication is focused on situation analysis instead of information dissemination, and participation instead of persuasion, making individuals active agents of development efforts instead of passive recipients (Mefalopulos, 2008). Community members are no longer viewed as “beneficiaries” (“objects”) but as “partners” and “colleagues” (fellow “subjects”) (Cadiz, 2005). This will facilitate dialog between stakeholders concerning a common development problem or goal with the objective of developing and implementing activities contributing to its solution and supports and accompanies this initiative (Bessette, 2004).

This type of communication is envisioned as a horizontal process aimed at building trust, then at assessing risks, exploring opportunities, and facilitating the sharing of knowledge, experiences, and perceptions among stakeholders (Mefalopulos, 2008).

Keywords in this approach are “information,” “communication,” “participation,” “consultation,” “capacity building,” “empowerment,” and “dialog” (Mefalopulos, 2008:39). Servaes (in Mefalopulos, 2008) also states that “the successes and failures of most development projects are often determined by two crucial factors: communication and people‟s involvement.” Therefore this old, vertical model is no longer applicable as a “one-size-fits-all” formula and it is argued that, since it is in the community that problems are present and solutions can be discussed, the point of departure must be the community (Servaes, 2008). Thus, communities must be involved in identifying their own development problems, in seeking solutions, and in taking decisions about how to implement them (Bessette, 2004), and the idea is that this type of genuine dialogic communication model would almost automatically produce participation and empowerment (Anyegbunam et al, 1998; Bohm, 1996; Freire, 1997 in Mefalopulos, 2005).

2.3 Reasons and arguments why participatory communication should be implemented in development work

The arguments for why participatory communication should be integrated in development projects focus on different aspects of the benefits. Mefalopulos (2008) describes five reasons:

(1) services can be provided at a lower cost;

(2) participation has intrinsic values for participants, alleviating feelings of alienation and powerlessness;

12

(3) participation is a catalyst for further development efforts; (4) participation leads to a sense of responsibility for the project;

(5) participation ensures the use of indigenous knowledge and expertise.

He also claims that communication interventions in development programs create four key outcomes: reduced political risks, improved project design and performance, increased transparency, and enhanced voice and participation. (Mefalopulos, 2008:217). As it allows a reduction or elimination of risks and misunderstandings that could negatively affect project design and its success, it increases the effects and sustainability of a development intervention (Mefalopulos, 2008).

Real change in development programs is impossible without an on-going, culturally and socially relevant dialog within the recipient group itself in which development providers and clientele participate on equal terms (Servaes, 2008). When not involving stakeholders from the beginning of a project, it is more likely that they become more suspicious of project activities and less prone to support those (Mefalopulos, 2008).

Both from a political perspective (good governance and a rights-based approach) and from a technical perspective (long-term results and sustainability of initiatives), participation can be considered a necessary ingredient for successful development (Mefalopulos, 2008). It is for example more likely that an advocacy efforts succeeds when it engages different groups and sectors of society (Baú 2016); communication is a vital partner in initiatives that involve voluntary behavior change (Servaes, 2008), and an active involvement in the process of communication itself will accelerate change‟ (Servaes and Malikhao in Baú 2016).

Besides gaining stakeholders support when increasing the level of participation, it also gives outside experts and managers valuable insights into local reality and knowledge that ultimately lead to more relevant, effective, and sustainable project design (Mefalopulos, 2008). In the case of research interventions for example, specialized knowledge might not be enough as it may not be adapted to a local context. Validation of that knowledge in the local context is then an important process (Bessette, 2004).

Mefalopulos (2008) writes about “communication to empower”, and empowerment is about individuals taking control of decisions regarding their own life and liberating themselves from structures and relationships of domination (Baú 2016). By some, community empowerment is considered as the main goal of interventions (Waisbord, 2005). Poverty is not just a lack of funds, it is also about capabilities deprivation and social exclusion. By involving people living

13

in poverty in the decision-making process, and by making the voices of the poor heard, it is believed that the dialogic mode can address and reduce one key dimension of poverty: social exclusion (Mefalopulos, 2008). Waisbord (2005) writes that “individuals and communities become empowered by gaining knowledge about specific issues, communicating about issues of common concern, making decisions for themselves, and negotiating power relations”. Participatory communication not only facilitates people‟s empowerment, it also enhances the application of the rights-based approach, and supports transparency and accountability, key elements of good governance (Mefalopulos, 2008).

3. Literature review and existing research

Many multinational organizations have incorporated participatory communication approaches in their development policies and practices, using different communication tools to achieve their development aim.

UNICEF is one of the many organizations which incorporate participatory communication in their projects (van de Fliert et al, 2014:22) , many of which have a concrete impact on behavior and social norms UNICEF, 2016:5), and has made substantial investments in developing its capacity in working with it since 2009 (ibid:1) as they are convinced of its added value (ibid:5).

In an evaluation of some of its projects, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) explains how agricultural extension activities, similar to the one described in this essay, that include awareness and promotional programs, trainings, and workshops, among other initiatives, have led to improvements in farm practices and crop productivity. In their analysis, one reason to why similar projects did not have the same success rate and sustainability was the lack of a strategy, procedures, and systems which allows for an efficient way of communicating project knowledge from experts and agencies to stakeholders (Biglang-awa & Bestari, 2011).

The analysis further explains how the lack of a communication strategy and its associated support system has negative implications on project operations. As an example the describe a water supply and sanitation project in Laos which, due to a lack of attention on issues connected to community awareness, communication, public training/education programs on water treatment methods, and wastewater drainage, did not manage to develop the wastewater drainage channels planned. Their conclusion is that even though the population was willing to

14

implement the changes, they were not sufficiently aware of their importance and as such the demand from the targeted communities was lacking (ibid).

A governmentally funded water supply project in Hanoi, Vietnam, which used UNICEF‟s approach to participatory communication as part of it key strategies, found that an essential part of creating a sense of ownership and commitment towards promoting and maintaining new technological systems within the community, was to involve the community in the earlier stages of design and planning, as well as in the implementation, operation and management of water supply infrastructures (Wright-Contreras, March, & Schramm, 2017). ADB seems to have similar experiences in their projects and claim that another benefit of an effective communication process that enable project proponents to listen to feedback and to respond appropriately to emergent issues is that it raises awareness and encourages dialog, identifies problems and mitigates risks (Biglang-awa & Bestari, 2011).

Another lesson learned according to ABD comes from an area development project in the Philippines which was based on a top-down approach in which the beneficiaries were simply informed of the investment decisions. This consequently created weak ownership and poor sustainability of the project. The lack of local involvement led to overdesigned and expensive irrigation systems, and the lack of stakeholders monitoring created construction deficiencies, incompleteness, and reduction in irrigation command areas as well as fund misuse. Being too „top-driven‟ and focused on experts, instead of local stakeholders in the preparation and design of projects, tend to create problems in operation and maintenance, as well as in the feeling of stakeholder ownership, particularly when the experts have left and thus having a negative impact on the projects sustainability (ibid).

FAOs experience has proven that incorporating this approach in their development initiatives make them more successful than those who use it as an isolated activity, or not at all. FAOs conclusion is that participatory communication should be included as a part in the entire process “from the initial issue identification and programme design through to evaluation

and impact assessment” (ibid:28) and to be effective, it requires active participation and an

all-inclusive approach which involves stakeholders at local, regional and national levels (L‟Aquila in ibid:15). Having local participants and rights-holders identify problems and develop and implement solutions, makes initiatives tailored to the specific needs of local communities, ecosystems and environments. Nevertheless, participatory communication approaches or methods continue to be separated from other development initiatives (van de Fliert et al. 2014:17). Often because “participatory approaches that promote dialog and

15

engagement are often seen as costly, time consuming, and difficult to accommodate in well-defined plans and log frames” (Balit in Mhagama, 2016:55).

This can lead to social or behavioral change initiatives focusing on educational communication based on a monologic and one-way sender to receiver type of information dissemination in which the passive “receivers” lack the opportunity to interact with the message or the message sender (FAO, 2014:14) making the power relations unequal, giving the authority to the sender (Servaes, Polk, Shi, Reilly & Yakupitijage, 2012:25). Research has revealed that projects become more sustainable the more local and interactive the participation is (Servaes et al, 2012:23) as it may ensure that an initiative is suitable and effective (van de Fliert et al. 2014:28-29).

A UNICEF project evaluation (2015) shows that the participative processes are also seen by community members as a tool to deepen the level of their commitment to the project. Being identified as a member of a project or campaign also helps form a sense of community who help each other, and including awareness-raising among the general public and participants‟ family members also help increase a project‟s affectivity.

Studies have shown that the unequal power relations between communities and influential people and NGOs and their involvement in initiatives, have an effect on the way community members can participate and they are often excluded from the planning and design stages of projects (Mhagama, 2016:54). As a consequence, this often leads to the degree and nature of a community‟s involvement in an initiatives being decided externally (FAO, 2014:33). Researchers have claimed that commitment to participatory processes tend to be rhetoric rather than real practice (Lennie and Tacchi in Servaes et al, 2012:100). Arnstein‟s (in Mhagama, 2016:50) presents a ladder of participation in which „non-participation‟ is placed at the bottom. This step focuses on “educating” or “curing” the participants and while there is a promise of empowerment, the participants‟ agency is reduced at the same time. The second step „token participation‟ includes key words such as „informing‟, „consultation‟ and „placation‟. The participants views are sought, but they are not allowed to make the final decision. In the step „citizen power‟, community members are considered equal partners and are in control of decision-making processes and resources. In the first to steps the development agents have the power over initiatives consequently making participation not effective or genuine. Scholars have claimed that „too often, genuine and balanced community

participation only takes place at the operational stages of programme development‟ (Eversole

16

As discussed by many of the sources, participation focuses on changing power relations and can take place at all level of an initiative: (a) decision-making, (b) benefits, (c) evaluation, and (d) implementation (Servaes & Lie, 2015:125). This means that in participatory communication initiatives, indicators should be developed together with key participants to reflect what participants want to know and why as well as to make them more realistic and useful (Servaes, 2015:246). This also entails that evaluations and impact assessments should include baselines formulated through participatory processes as well as self-evaluations by the community (ibid:248).

4. Methodology

To allow for profound investigation of my research question: How does development projects in Guatemala, funded by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, include participatory communication in the project cycle and does it affect their results?, I have decided to use a primarily qualitative approach based on interviews and a Case-oriented Comparative Research. The reason behind choosing Comparative Research was based on the fact that comparison is the logical way to measure whether the type and level of communication included in projects actually have any impact.

The case-selection for this investigation is based on a strategic decision to work with a quite narrow scope (Olsen, 2012) by selecting one recently completed project from the Embassy‟s portfolio which functions as a representative. The identification of the projects included in this study became clear through discussions with Embassy staff as the Sida-funded project led by Oxfam, Rural Producers accessing markets and increased food security in Guatemala, was the only project suitable for this type of study as it allowed for an analysis and a comparison connected to a participatory communication approach in the projects. The case-oriented approach aims to allow for a complete understanding of the selected cases with “thick description” hence using several comparative characteristics or variables (Given, 2008).

Oxfam‟s project itself was deemed successful although not all local projects had reached the foreseen goals. Through guidance from the Oxfam representative two local projects, AMUPAVET and Granja Avícola Maya Kaqchiquel, were chosen as one stood out as successful and the other as unsuccessful (by all stakeholders, in particular the local participants) as it had not reached the foreseen results.

17

Being comparable implies that the projects are similar in a few respects but not all (Olsen, 2012). A “domain of investigation” was created in which the two projects paralleled each other sufficiently and shared enough background characteristics to be comparable: they shared specific time, geographic and thematic limitations as well as both being within the local organization CICAM‟s scope. This permits a comparative study of diversity which allows for a “Most similar, Different outcome system design” (Rihoux, & Ragin, 2009) in which the assumption is to find differences, factors and variables that can be used to explain patterns (Vogt, 2005: Przeworski & Teune in ibid) as to how and why particular programs or policies function or not (Goodrick, 2014). The aim is to develop concepts and generalizable knowledge based on the identified similarities and differences (Lewis-Beck, Bryman, & Futing Liao, 2004) found the projects.

After having decided on which projects to study I reviewed existing documents and material related to them to investigate and collect information on how issues connected to participatory communication were included, discussed and analyzed before, during and after the selected projects started and ended. The material used to analyze and compare consisted of, but was not limited to, Oxfam‟s project proposal, the external project evaluation and the Embassy‟s program evaluation. The review allowed for the gathering of some general information as well as preparing for subsequent interviews and ensuring that these would be conducted efficiently (Chen, 2005).

The design of the interviews was aimed to capture a combination of the participants‟ subjective viewpoints and objective information connected to the individual‟s experiences and perspectives on the communication connected to the projects. It aimed to measure the different perspectives connected to their collaboration, the level of communication and to understand the perceptions connected to their relationships with each other and with other stakeholders and participants within the projects.

A reason behind the decision to use interviews to complement the written data is the fact that individuals with personal experiences can contribute with important information in an interview setting (Chen, 2005). And to get contrasting perceptions on this common topic (Mathison, 2005), the study includes not only Embassy, Oxfam and CICAM representatives but also members from the local projects. The semi-structured interviews used to collect data (Mathison, 2005) are mainly qualitative and in-depth, focused on encouraging the respondents to share their experiences. These interviews are the most important sources of information and knowledge (Gubrium & Holstein, 2001) besides the data available in the written material and

18

the projects‟ external program evaluation. The interview questions were pre-determined but additional questions to clarify and expand on particular issues (Dudovskiy, 2016) were included as well. Most of the beforehand written questions were the same or similar for all interviews to allow for an understanding of different perceptions on the same issues.

Qualitative research designs is also helpful in identifying and assessing issues not easily measurable, such as participation, empowerment, or accountability, and this approach allowed for an understanding of the participants and organization representatives experiences, values, assumptions, beliefs, and perspectives (Mathison, 2005), including their internal experiences and perceptions on the approach connected to the projects. This is important as it may have had an impact on how the project was planned and implemented as well as to see the possible outcomes it might have had.

The interviews with the two local projects, AMUPAVET and Granja Avícola Maya Kaqchiquel, were conducted face-to-face in groups of two and six, depending on the participants‟ availability. Although FtF interviews were preferred, the interviews with the Embassy, Oxfam and CICAM‟s representatives were individual and conducted through Skype. All the interviews were recorded, notes were taken and parts of them were transcribed. There were several reasons behind the decision to focus on live interviews, such as the possibility to receive extra information through visible and audible reactions from the respondent, in addition to an opportunity to receive more spontaneous answers without extended reflections (Opdenakker, 2006). Conducting the Ftf interviews also allowed visits to the project sites which increased my familiarity with projects (Chen, 2005).

Comparative Research methods were used to complete the analysis of the differences and similarities discovered through the collection of information and data connected to the projects. The topics and messages collected in the interviews were organized according to themes to allow for a comparison between the different points of view expressed by the participants. This, together with the data and evaluations written by the Embassy and Oxfam as well as Sida‟s and Oxfam‟s general view on participatory communication is the basis of the discussion and the conclusion that follows.

4.1 Issues and limitations

Time limitation, cultural barriers and bias and the limitations of my Spanish etc. were, to a certain extent, unavoidable limitations in this study. Practical issues and limitations mainly consisted of it becoming much more difficult to find projects to investigate than expected

19

which to a certain extend obliged me to this Oxfam led project. This changed the foreseen scope slightly as it focused more a macro-level with two projects that had many aspects in common rather than a comparison of two big projects.

This may increase limitations in terms of scope and method: The study is based on only one part of a program containing several other local counterparts focusing on different issues, instead of the project as a whole or a comparison of two whole projects. The sample size, especially in terms of responsible staff at the organizations and the Embassy, may have an effect on the representation of experiences and views. I believe that albeit the limitations in size, the data collected function as an indicator of what had been found in a more extensive study and that it reflects common opinions and experiences.

The Embassy staff member responsible for the project changed three times during the program course – some leaving the Embassy, making it difficult to get a complete view of the process from the Embassy‟s point of view and the situation at Oxfam was similar. My solution was to interview a former Oxfam staff member who worked on this project, and I another member of staff from the Embassy with whom the question were more general to their character.

Critique can also be made connected to both the local case- and participant selection (Peterson, 2005) as the extensive material related to this project, and the lack of detailed information on the local initiatives, meant that they were chosen through the guidance of a former Oxfam staff member as well as through circumstances such as availability and contacts. There is also a risk that discovered differences between the two cases compared may be unintended or due to any number of other factors (Peterson, 2005). Even so, I consider the groups to be quite representative of the groups in the project and they contain aspects connected to successful and unsuccessful projects which allows for a good comparison. Inaccuracies caused by relying on self-reported views instead of measuring what people (report) doing (Peterson, 2005) are likely to have affected this study as well. Attempts to circumvent this, through combining qualitative and quantitative component (Babbie in Mefalopulos & W. Bank, 2008:140) were made, but illiteracy, a lack of understanding of the survey and the fact that not all that not all participants answered forced me to exclude it from the data.

Interviews are often criticized regarding practical aspects and logistic reasons such as long time requirements, difficulties arranging meetings to conduct interviews, reaching

20

respondents as well as dealing with contextual factors such as gender, class etc. in both the interview process and in the evaluation (Dudovskiy, 2016, Mathison, 2005). And these issues became apparent during the data collection phase of this study as well and were responsible of changes such as using Skype instead of FtF-interviews in some occasions.

In terms of ethical issues or challenges I found the power relation between myself and the participants the most important. I was uncertain whether they fully understood my function and were expecting the interviews to help them move forward in their projects or that I could influence funding. As the Embassy, Oxfam and the local organization CICAM were all involved in connecting me with the necessary people, talking to me could have been perceived as an obligation as they are dependent on funding for example. I was aware of this and tried to be clear about my role and involvement with the organizations when I met them, but it was difficult to control how the organizations approached them with my request and what they said.

This may of course have had an impact on their answers i.e. the data. I did try to avoid this by asking the same questions in different ways as well as to talk about issues on both a personal and general level. I have also taken this into consideration when analyzing the answers.

5. The Project: Rural Producers accessing markets and increased food security in

Guatemala

5.1 Local circumstances

In Guatemala, 51% of the population live in poverty and 15.2% live in extreme poverty (Puigmartí, Cucurull, & Cifuentes, 2015:25). In the region of Sololá, in which both development projects studied in this essay are located, 74.6% of the population lives in poverty and 29.3% live in extreme poverty. 70% of children under five suffer from chronic malnutrition. It is also one of the regions with the highest number of indigenous people (more than 80%), and the majority of its population live in rural areas (Puigmartí et al, 2015:25). Sololá is also an area which is very vulnerable to climate changes with long periods of drought followed by heavy rain thus also highly vulnerable in terms of food security (ibid:26). Women contribute significantly in the agricultural process and food production but have the least power in the market and in the value chain. This is connected to the great difficulties getting access to the production assets while also being responsible for the unpaid domestic labor. Women‟s‟ contribution is often overlooked as it is regarded as supporting the husband

21

(ibid), and it is often he who receives and administrates the income. The women are thus excluded from the decision-making at home, in communities and in the different organizations connected to agriculture as well as lacking any proper economical resources making them the extremely vulnerable (ibid:26). These are some of the reasons behind Oxfam‟s decision on the geographical location as well as the project‟s focus, and all of the local initiatives included in CICAM‟s part of the project, except for AMUPAVET and their catering business, are placed in rural areas far from the main cities and mainly focus on food production (ibid:137).

5.2 The project: Circumstances and goals

This Oxfam-led development project wanted to “achieve better and greater access to the

market for producers who find themselves with a surplus, and to promote the access of producers to self-consumption to productive livelihoods that allow them to move from a level of self-consumption To surpluses and establish relations with fairer markets" (Puigmartí et al,

2015:17).

The Swedish Embassy in Guatemala and Oxfam began identifying operational synergies and possible collaboration in June 2012. Initially, and during the identification process, the project was planned to have duration of three years. But since the Swedish Embassy would only commit to funding the project for two years due to a new development strategy arriving, it was decided that the project would be active between May 2013 and May 2015 (ibid:35). Sida, through the Swedish Embassy, funded the project; it was administrated, supervised and controlled by Oxfam and implemented by six local counterparts who were responsible for different parts of the three results. This study focuses on CICAM (Oxfam, 2013:3), and two of the grassroots initiatives included in their scope.

The original budget was 6,3 million dollars out of which six million came from the Swedish Embassy. Oxfam decided to allocate an additional 300 thousand at the end of the project which went to CICAM and their projects (Puigmartí et al, 2015:17). The final evaluation states that 63,6% of the 6,3 million dollars was spent on activities necessary to reach to goals of the project. The remaining sum was spent on the administrative aspect of the project such as salaries and technical assistance as well as the general cost of Oxfam as the responsible organization for the project (ibid:105).

22

Figure 1. Project structure

According to the external evaluation, one of the mayor flaws with the project‟s design was the very narrow time limit making it very stressful to complete the project on time (Puigmartí et al 2015:7). Despite this, the evaluation considers the project very efficient in reaching and even in some cases even surpassing almost all of the project‟s goals (ibid:7) and it managed to reach practically 100% of the targets and expected out-puts (ibid:150). The evaluation calculates that levels of short-time income increased with 10% and levels of medium to long-time income reaching more than 30% in general (ibid:11). In total 149 women participated in CICAM‟s initiatives and, as these women lacked an income previous to the project, they experienced a 100% increase of earnings compared to the baseline (Oxfam 2015:12).

In terms of gender, the evaluation verifies that in many of the organization the participation of women have increased and the number of women on the boards of directors is higher even though the most important positions such as presidents and treasurer are still held by men. At home there has been a slight redistribution of domestic tasks from the mothers to their children (Puigmartí et al 2015:13).

23 6. The project’s stakeholders

6.1 Sida and participatory communication

As previously stated, Sida funds Swedish development cooperation with a budget based on one per cent of Sweden‟s BNI, mainly through development projects connected to the Swedish Embassies ("Sidas budget", 2018) such as with the project studied in this thesis. Sida‟s Department for Policy and Methodology (Sida: Information department, 2006:4) claims that there are factors that suggest planned communication contributes to greater fulfillment of objectives and results of a project, and it describes how dialog is central in the work. Besides a more practical stance on why participatory communication should be used such as being a tool to engage stakeholders and to make aid work more effective (ibid:8), there is the idea of including poor people‟s perspectives and a rights perspective as starting points in all Sida‟s work (Sida: Division for culture and media, 2006:8) as it is key to achieve change: “when people living in poverty are really able to influence, participate and have

access to a public arena, that injustices, hunger, conflicts and abuse of power can be averted” (ibid:4).

The policy also underlines the right of freedom of expression and the right for people to participate in decisions that concern them (ibid:8) as well as highlighting the importance of that in-depth knowledge about the local social and cultural conditions, as well as letting people living in poverty be the main protagonists both in the communication itself and in the process of changing the society in which they live are key to achieve local ownership and participation in interventions (ibid:11).

These perspectives are claimed to include participation, dialog and communication and the idea of giving poor people a voice (Sida: Information department:5). It is also stated that participatory communication approaches are supposed to be used at all phases of Sida-funded projects – not only as a tool to disseminate information at the end (ibid:53).

Claims have been made that even though there is an interest and awareness concerning participatory communication and what such an approach entails at Sida, the organization falls short in terms of implementation. The criticism claims that even though there is an official emphasis on participatory horizontal communication, it is combined with a paternalistic, top-to-bottom understanding of communication which is not coherent with such an approach. This would thus create a situation in which there is no coherent and comprehensive strategy for

24

communication in Sida‟s development work (Rico Hernández, Stenqvist, Refai, Larsson, Yager, Gilani, Dalén, Abdulla, 2012).

The role of Sida‟s staff members in Sida-financed projects is to raise awareness among key stakeholders of:

“possible communication needs (…) that might exist in a particular project/programme. (…) make sure to promote and raise awareness of communication aspects in our contributions, even though it is the project owner/manager that must make the decision to embark on a communication-planning process. Planned communication should be considered and included from the very beginning of the contribution (project) cycle. It is of utmost importance to include communication aspects already in the early preparatory phases of a project (and in the official project document).” (Sida: Information

department, 2006:53).

Sida‟s communications manager explains that there is no overall strategy or methodical support concerning participatory communication at Sida, but that communication is integrated as a part of the development cooperation in different ways depending on the project. It can be through participation at different levels of a project such as problem specification or evaluation. It can also be through supporting programs that can be considered to be within a participatory communication approach, or that participatory communication is used as a communication component in programs such as supporting female participation in media (personal communication, April 6-17, 2018). Echoing the policy (Sida: Information department, 2006:53), she explains that it is up to the strategy owner at Sida and the partner organizations to consider how communication can be integrated and used in projects and programs to achieve the planned result (personal communication, April 6-17, 2018).

6.2 The Swedish Embassy in Guatemala

The then development strategy of the Swedish Embassy in Guatemala, written by Sida and approved by the Swedish government, stated that the development cooperation were to function from a rights-based perspective and poor people‟s perspective on development. It would contribute to creating conditions that allowed poor men and, particularly, women improve their living conditions by focusing on sustainable poverty-oriented economic growth in poor areas (Regeringskansliet, 2008:2-3).

25

When approving a project proposal, the Embassy staff primarily base their decision on whether the strategic priorities presented coincide with the Embassy‟s priorities ("Interview Embassy Representative", 2017) which Oxfam‟s project priorities (Puigmartí et al, 2015:78) were considered to do. Political dialogues between the Embassy and the other party, finding the correct counterparts as well as receiving a concept note from the partner organization are other steps included before approving the project. There are also discussions concerning the relevancy of the project and if it creates possibilities of improvement ("Interview Embassy Representative", 2017).

As mentioned, planned communication should be incorporate in projects in dialog with partners (Information department, 2006:26) and the Embassy‟s representative claims that “participation and communication are always taken into account in discussions concerning the design as well as the goals at the end of the project [in discussions with counterparts concerning Sida-funding] but there is not a standard procedure” (author‟s translation), and communication strategies or plans are usually not included in the projects. And even though there is an initial consultation with local stakeholders in many project proposals, this does not necessarily become permanent throughout a project ("Interview", 2017).

Field trips are also vital for the program officials to understand and make sure that communication and participation are present in the projects. It allows Embassy staff to see the activities undertaken by the project, as well as to talk to the participants themselves and get their point of view ("Interview Embassy Representative", 2017). Unfortunately it seems that depending on the priorities of the superiors at the Embassy, who change every couple of years, as well as the work load of the individual program official, the number of field trips can be quite low and differ between projects ("Interview Embassy Representative", 2017).

Sida‟s assessment tool includes questions concerning the consultation and participation of the project‟s participants which the program official answers. But as there are no overall strategy or method, and the individual program official has the responsibility to raise awareness of communication aspects (Information department, 2006:8), there might be a risk that the amount and the quality of dialog with stakeholders depend on the individual program officer and their views on the significance of communication. As it is believed that participatory communication should be implemented as a coordinated and institutionalized strategy rather than depending on the interest and ambitions of individual members of staff, the lack of a common method has been criticized (Rico Hernández et. al, 2012).

26

As the responsible program official changed three times during the project studied in this thesis, it is difficult to see how and when participation and communication were discussed, when fieldtrips took place and whether advice or demands concerning more, or another type of participation and communication were presented to Oxfam. Even so, it seems that the Embassy agrees with the final evaluation regarding the project being successful (internal document).

6.3 Oxfam

Oxfam is a multinational organization active in Guatemala. Its global objective is to construct a future without injustice and poverty. Oxfam‟s teams work with local counterparts to reach the communities and implement activities to help improve people‟s life conditions and promote them being participants in the decisions concerning their problems and opportunities (Moreno et al. 2015:7). Oxfam do so through a methodology called WEL which will be explained below (Oxfam, 15/05/2015:Anex D).

In Oxfam‟s strategic plan 2013-2019, they express a desire to focus on local voices as it sees a rights-based approach as being the best way to tackle discrimination, exclusion and the injustice of poverty. Oxfam US describes how this approach aims to identify the critical exclusionary mechanisms and as an organization, its work is to assist participants to overcome them (Offenheiser & Holcombe 2003:271) through negotiation of a shared agenda leading to a redistribution of power (ibid:288). This entails a shift in target as Oxfam sees exclusion and inequality as more important than a lack of income (Oxfam, 2013:5).

Oxfam criticizes previous development approaches in which the donor set the agenda and could change it, and also how donors focused accountability to identify short-term outcomes in older models of development. They also criticize how many NGOs talk about partnership with stakeholders, but that these partnerships often become a patron-client relationship because of the unequal power relations (ibid:287). It describes how the Oxfam method is based on a participatory approach that entails an inclusive development which has a pro-poor approach, viewing people living in poverty as agents of their own development through the right resources, support and training, and not as passive recipients of aid (Oxfam, 2014:1). The Oxfam approach equally values and incorporates the contributions of all stakeholders in addressing development issues (Oxfam, 2011:1).

27

To create the local groups that would later partake in the different initiatives within the project, Oxfam received help from local agricultural organizations in identifying possible groups and their members. In the implementations phase, after the counterparts had formulated a project plan, the local groups were invited to present their investment proposals of what would later be the groups‟ activities, and a cost analysis were conducted by CICAM and the women. There was dialog with the women interested in joining a group to make sure they were serious in their wish and all the women were included in receiving instructions and participating in meetings, as well as in dialogs concerning the goals and objectives of the projects (ibid). Great effort was made to make sure that the decisions taken came from the participants ("Interview Oxfam Representative", 2017)

The project, as well as the methodology WEL, focused on “learning by doing” and when having been assigned an activity, the women received technical support concerning agricultural production and good practices throughout the project ("Interview CICAM Representative", 2017). Even though the women‟s decision concerning what activity they wanted was influenced of hearing of successful examples, Oxfam made sure to take the local context into consideration when distributing the activities to avoid overflowing the market or causing competition between two groups ("Interview Oxfam Representative", 2017).

Even though the women became involved in the implementations phase and were not included in formulating neither project plan nor the indicators, the external evaluation considers that the selection of the groups‟ activities was completed in a participatory manner (Puigmartí et al. 2015:122). The participants who were considered to have a complete view of the activities‟ process and achievements were included through interviews in the evaluation phase together with the organizations and stakeholders. Beside document reviews, field trips and interviews were conducted with a majority of the groups ("Interview Oxfam Representative", 2017), including 10 of the 15 CICAM projects in Sololá in which relevance, efficiency, performance, impact and sustainability of the projects design, process and results were evaluated (ibid:21).

6.3.1 The method WEL

CICAM‟s part of the project was defined by the Oxfam methodology WEL which aims to improve the design of market interventions to allow women‟s economic leadership. The goal is to give women economic and social power to allow them to escape poverty, and the

28

methodology also wishes to teach them to work together, be independent and learn to distribute the work between them ("Interview CICAM Representative", 2017).

The application of this methodology entails organizing women in groups to start a business or venture which is led by the women and allows them get an increased income and interaction with the market which is believed to facilitate a change in the relationship between men and women as the value of their work becomes clearer (Puigmartí, 2015:121). This is achieved through the seven processes of the methodology (ibid:137) which enables Oxfam to “assess

the impact of our programmes, learn from our experiences and increase our accountability to different stakeholders” (Oxfam, 15/05/2015:Anex D).

Figure 2 Steps of method WEL

The idea of these processes is to take the opinions of the participants and partners into account by collecting information while including them in the reflection and learning processes. The information presented through monitoring and evaluation is believed to allow Oxfam to give

29

The Oxfam representative explains that the project entailed a high level of participation and dialogue as Oxfam made an important effort to make sure the participants‟ decisions were heard. They included discussions concerning communication and participation in the project and to use the women‟s experiences as the point of departure was highlighted in the

collaboration with CICAM ("Interview Oxfam representative", 2017).

CICAM representative explains that the method is design so that everything is done together with the women at a communitarian level, and while all groups went through the same process, the results were different. She describes the methodology as very technical and although it gives important tools, it was necessary that CICAM contextualized and adapted it to a communitarian level, “otherwise the women would not have participated at all and the

projects would have been managed by external experts”. She explains that either there is

participation at a participatory level, or the methodology does not work ("Interview", 2017). The evaluation concludes that the WEL methodology and its seven steps was not followed in the implementation this project (Puigmartí et al. 2015:137). Both the Oxfam and the CICAM representative claims that the methodology really is designed for women who have reached a certain level of development and that the women who participated have not yet reached that level yet and that they needed to learn how do to things such as handle money first. According to the representatives this could be connected to the participants‟ level of education making technical assistance necessary ("Interviews ", 2017). CICAM still uses this adapted version of the methodology in its current projects and it is claimed to have a completely communitarian perspective, that being said, the representative still believe that the methodology should have been adapted even further ("Interview CICAM Representative", 2017).

6.4 CICAM

CICAM is a NGO focused on service, assistance and integral development that especially pursues the study, research, training and support of Guatemalan women. CICAM worked on the project's objective of empowering women's rights and empowering women in organizations and the different spheres of participation (Puigmartí et al, 2015:39). CICAM initially had an advisory position and participated in the project as gender consultants. Through their participation, the project could identify issues connected to gender within the organizations as well as possible solutions ("Interview CICAM Representative", 2017).

30

Due to economic irregularities, the organization initially responsible for Result 3 left the project, leading CICAM to take over in both geographical areas in addition to their original role. CICAM also prolonged this part of the project with an additional six months. They began their work in September 2014 and continued on until September 2015 (ibid). The external evaluation supports the decision to let CICAM take over this part of the project as performance was significant even though the organization had no previous experience regarding the implementation of projects connected to productive development (Puigmartí et al, 2015:80).

CICAM began its new responsibility by identifying groups of women and managed to surpass the goal of 16 and reached a total of 22 initiatives, two local cooperatives for women and 113 women participating in the initiatives in Sololá ("Interview CICAM Representative", 2017). CICAM estimates that 1000 people were reached by the initiatives, including family members and people around the participants and about 20% percent of the groups that continued with the initiatives after the collaboration with CICAM ended, have managed to achieve a lot of things and to diversify the initiatives by themselves. For these reasons the CICAM representative feels that “it was unfortunate that the organization was not involved from the

beginning of the project as she believes so much more could have been achieved". CICAM

and Oxfam continue to work together in other projects today (ibid).

6.5.1 The Cooperatives

Included in CICAMs initiatives were two cooperatives created to support the women in the groups and to ensure the sustainability of the initiatives during and after the project course. The purpose of the cooperatives was to help the women commercialize their products, have a central for the purchase of supplies, offer credits and technical assistance Oxfam and CICAM staff, disappeared (ibid).

To become a member of the Cooperatives, the women had to be active in one of the women‟s initiatives and pay a membership fee of around 14 dollars as well as a 40 dollar contribution which then became money available for other projects or loans to members. Three and five of the women who are active in the groups of this study are also members in the Cooperative as the others found the membership fee to expensive, but all the women have voted for one of the members to represent their group in the Cooperatives‟ meetings. (“Group Interview AMUPAVET, 2017”).