Exploration of how to improve

experience by designing a

self-service technology

Linn Nerlund

Interaction Design Bachelor 22.5HP Spring/2018Abstract

The benefit of a self-service technology (SST) is often for the companies, needing less employees when the customers can perform the service by themselves. But an SST might not always benefit the customer or employees experience. However, there are certain attributes that motivates customers to use SSTs and sometimes preferring them over service staff. This research explores how to design an SST with the aim of improving the overall service experience, for both the service customers and its employees at a mid-range hotel. By involving the stakeholders in the design process using co-creative methods, opportunities for improving their existing service was identified. Concepts were developed in co-creative workshops, and prototypes were designed and tested using interaction design principles. The final design was an SST kiosk that shows potential of improving the experience for customers and employees at the hotel.

Key words: Self-service technologies (SST), interaction design, service

Acknowledgements

A special thank you to the stakeholders at Prince Carl Hotel for participating in this design research and contributing sharing their knowledge and ideas. I would also like to thank my supervisor Anuradha Venugopal Reddy, for keeping me stay on track throughout this design research by providing me with guidance whenever I needed help.

Finally, a thank you to the customers at Prince Carl Hotel for their feedback and contribution when testing the prototype.

Table of contents

1 INTRODUCTION ... 6

2 BACKGROUND... 6

2.1 Hotels and SSTs ... 8

2.2 General problem statement ... 10

2.3 Target group ... 11 2.4 Limitations ... 11 3 THEORY ... 11 3.1 SST experience ... 11 3.2 Motivation to use SST ... 13 3.3 Co-creation... 14 4 METHODS ... 16 4.1 Litterature studies ... 16 4.2 Interviews ... 17 4.3 Survey ... 17 4.4 Observations ... 17 4.5 Workshops ... 18

4.6 Analysis and mapping ... 19

4.7 Prototyping ... 20 4.8 Ethical considerations... 21 5 DESIGN PROCESS ... 21 5.1 Semi-structured interview ... 22 5.2 Observation... 24 5.3 Analyzing customers ... 28 5.4 Workshop 1... 29 5.5 Workshop 2... 32 5.6 Low-fidelity prototype ... 38 5.7 Mid-fidelity prototype ... 42 6 DISCUSSION ... 47 6.1 Self critique ... 49 7 CONCLUSION... 50 REFERENCES ... 52 Appendix 1 ... 56 Appendix 2 ... 56 Appendix 3 ... 58 Appendix 4 ... 59 Appendix 5 ... 59 Appendix 6 ... 59

Figure list

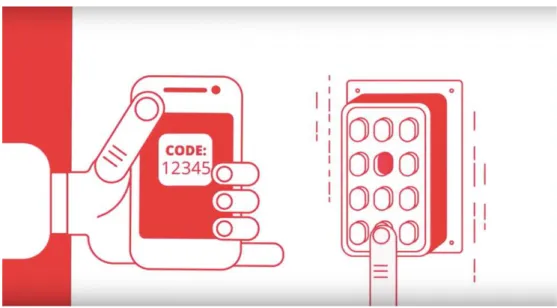

Figure 1: Guest unlocks door using phone at Nordic Choice Hotels (Schoultz, 2018) ... 8

Figure 2: How to enter the hotel and room (Omena Hotels, 2o18) ... 9

Figure 3: Robot that stores the guest’s luggage (Yotel, 2018) ... 10

Figure 4: Sanders and Stappers (2012) say, do and make techniques. ... 16

Figure 5: Illustration of the Double Diamond design process ... 22

Figure 6: Stakeholder map of Prince Carl Hotel ... 24

Figure 7: Reception and bar area at Prince Carl Hotel ... 25

Figure 8: Overview of today’s guests in Prince Carl Hotels booking system, Sirvoy. ... 26

Figure 9: Service Blueprint of Prince Carl Hotel ... 28

Figure 10: Stakeholders creating personas in Workshop 1 ... 31

Figure 11: First persona, representing the 50+ customer group. ... 31

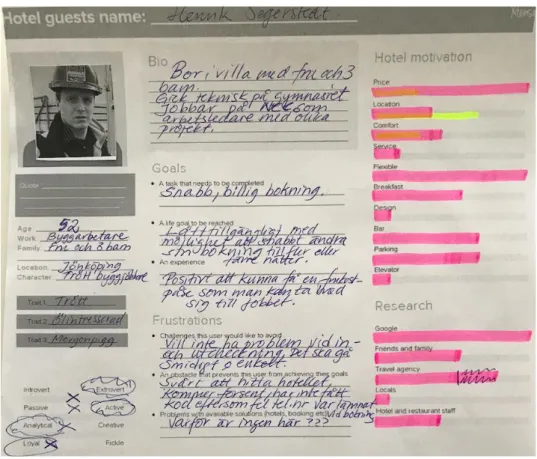

Figure 12: Second persona, representing the “worker” group. ... 32

Figure 13: Customer journey based on the two personas, 50+ and worker... 33

Figure 14 Sketches of ideas and inspiration photos ... 35

Figure 15 Stakeholders exploring and acting out the concepts ... 37

Figure 16 Questions asked during the guest’s customer journey ... 39

Figure 17: Wireframes showing different categories ... 40

Figure 18 Exploring placement and information ... 41

Figure 19: Sketch of how to build the SST kiosks ... 43

Figure 20: Final design. Painted wood board and attached iPad on the backside ... 43

Figure 21 Interface of the SST kiosks categories ... 44

Figure 22 Guests exploring the SST kiosk prototype ... 45

1 Introduction

Self-service technologies (SSTs) provides the customer to perform a service without the need of an employee or attendant, by interacting with an interface or technology instead. Existing examples is when scanning and paying for the items in a grocery store using self-service machines and self-check in systems at airports or hotels. Self-service technologies are not a new phenomenon, but they are continuously growing in a digital society alongside new developments, giving designers the possibility to create SSTs for a wider range of situations. The benefit of SSTs is often a quicker service with less need of employment, which make SSTs attractive for many companies. However, the type of companies working very close to customers like certain hotels and restaurants, it is also important to create a personal and special experience for the customer. When looking at the regular existing hotel businesses not using SST systems, there could be a risk of losing the hotel experience if they replace an employee or setting with an SST. The SST has to be designed to fit the existing personal touch of the hotel as well as providing an experience and convenient service for the customer. This kind of situation can be challenging to design for and is a necessary area to explore in the interaction design and service design field.

In this thesis I explore the design possibilities of an SST in the context of an existing mid-range hotel. First, I will present the background where I give examples of existing SSTs in the hotel industry and stating the research question. Canonical examples of SST research are presented and discussed in the theory section. Furthermore, going through the use of design methodology of co-design and service design in relation to my design process that follows. The results of the prototype will be presented and a discussion and conclusion in the end.

2 Background

In society we are discussing more and more frequently whether technology will take over our jobs. According to a report of Smith and Anderson (2014), where experts in the technology field answered questions about their views of the future, some of them believed that the development of the technology will cause jobs in the future to require more education. This might be a big issue when our educational system is not prepared for that situation (Smith & Anderson, 2014). In the future, when for example self-service technologies (SSTs) will be able to do more advanced services for customers, a lot of service jobs will disappear from the job market (ibid). However, many of the technology experts also believed that the development of the technology can

be good for the future. We have the possibility to create a new kind of jobs, and with the help of technology we can perhaps work less hours and have more time for leisure (Smith & Anderson, 2014). According to these predictions, designers and researchers of today’s technology have the possibility to be a part of the creation in how we will use services and interact with the technology in the future.

To take transportation as an example of our global use of self-service technologies, many people begin by using an internet-based SSTs when researching or buying a flight ticket. The benefit of an SST is in many situations about getting better detailed information and having time to compare prices and read reviews (Lee et.al., 2009), which internet-based SSTs are an example of. When it is time to pay the flight ticket, there is no interaction with a human employee giving you a receipt. As usual, when purchasing something online we use SST payment systems. At the airport you might use your phone on a sensor-based SST to enter the security-check area instead of showing a physical ticket to an employee. Perhaps you also used the SST kiosk to check-in your luggage buy yourself. That being said, in the service of transportation, the landscape of SSTs varies from internet-based, sensor-based and kiosk-based to offer parts of the service using SSTs instead of employees.

The internet-based SST-option is used by a wide range of service ecologies and is probably the most frequently used in society today. As mentioned in transportation, it is common to compare options and buy tickets online. Other examples of services that uses internet-based SSTs is for example all the different retail services that offers online shopping, restaurants and hotels offering online reservation or booking. To help customers with questions, providing a FAQ (frequently asked questions) page has been a common SST option for many years. Nowadays more and more companies have also upgraded this service by adding a chatbot, helping customers with even more questions so they do not have to call a customer service.

When designing an SST for a service, it is important to understand the user you aim to design for (Morris & Venkatesh, 2000). That means, understand what drives the specific customer group in the service situation and their level of acceptance of technology (ibid). Morris and Venkatesh (2000) claims that people´s age matter if or how they will use the SSTs. Younger people have a more positive attitude towards SSTs and are more likely to adopt and have the interest to use them (ibid). However, according to a more recent study of Weijters et. al. (2007) where they analyzed the difference in people’s demographic variables in how they used an SST in a retail setting, the age difference did not matter. Instead, the differences in use of SSTs can vary upon their educational level (Weijters et. al., 2007). More educated groups appreciate new technology and especially feels motivated to use SSTs that appear new and innovative (ibid). For the less educated group it can for

example be more important that the SST appears to be trustful and safe to use (ibid).

2.1 Hotels and SSTs

A customer’s perception of the quality of a service is what makes them decide to buy and experience the service (Petrick, 2002). In the situation of a hotel experience, that means having the motivation to book a room and experience the hotel stay. The experience of the service is then the result of the customers perception of its value, which in turns contributes to customers reinvesting and coming back (ibid). Providing superior customer value is considered to be a key factor for success in the hotel industry (Choi & Chu, 2001, in Nasution & Mavondo, 2008). The value is also important in “word-of-mouth”, if people talk positively or negatively of the service (Petrick, 2002). There are existing successful examples in the hotel industry when the use of self-service technologies (SST) provides an experience which can increase to perceiving good value of the hotel stay. Recently here in Scandinavia, Rådlund (2018) wrote an article about a big success when using an SST at Nordic Choice Hotels (nordicchoicehotels.se). Recently 2000 of their customers used an SST application to check-in and unlock the doors to the rooms without needing interaction with an employee in just one day. The co-founder of Nordic Choice Hotels Petter A. Stordalen, claims that their self-check-in system will help improving their service by giving the staff more time with only those customers who request their attention (Rådlund, 2018). With less queues at the reception desk, the staff can provide that extra service, he argues (ibid). This hotel has the financial capability to not reduce the existing workforce of employees when implementing an SST, which makes it possible to improve the experience when customers can choose the type of check-in they prefer. When customers choose to interact with the service staff this experience can be said to have improved because the relief of some of the employees work load after the SST implementation.

However, this kind of investment is often not an option for small and mid-range hotels that have lesser financial support. Though, this is not necessarily a problem if that hotel focuses on other values than of high customer service and flexibility like the example just mentioned. Other values of low price and good location can also make hotels successful.

Petrick (2002) claims that many researchers agree with the fact that depending on how much effort the customer has to make contrary to what they receive back, is how value is perceived. The effort can be a tradeoff between convenience and the consumed money for the service or time spent (ibid). From the customers perspective, to use an SST instead of getting served by a staff member often requires more effort as the customer has to serve themselves (Collier & Kimes, 2012). This is why hotels that only provide the option of service by using an SST may not suit everyone. Low prices and convenient location is something that has a positive impact of the customers perception of the service value (Petrick, 2002) and many of the hotels only offering interaction with an SST has this concept to attract customers. One example of that concept is Omena Hotels (omenahotels.com) in Helsingfors, Finland. To check-in and access the room, the customer (guest) enters a code after paying for the reservation. By having no staff attending at the hotel to serve the customer breakfast, the situation is resolved by collaboration with a café nearby.

Figure 2: How to enter the hotel and room (Omena Hotels, 2o18)

It does not always have to be considered an effort to interact with an SST though. In a paper of Matthew et.al., (2000) the result showed that customers were satisfied and got a positive experience in an SST situation due to excitement about the SSTs ability to perform various tasks. This aspect of experience to create value is illustrated in the hotel Yotel (yotel.com) in New York, which provides many innovative SST features. For example a robot that stores the customers’ luggage. The concept of this hotel is the innovative use

of technology itself and the focus is on highlighting a good experience when interacting with the SST.

Figure 3: Robot that stores the guest’s luggage (Yotel, 2018)

As mentioned above, there are existing innovative examples of SST in the hotel industry that creates a positive experience for the customer and perceived value. However, there is a lack of research that explores how to create an SST design that can contribute to better experiences and value for the customer prior to the SST implementation. Researchers have evaluated particular SST experiences and attributes, as will be mentioned in the theory section. But there is a gap in evaluating the SST in relation to the whole service and how it contributes to affect other interactions within the service. Designing an SST with the aim to create better experiences in a hotel service is a start to fill this gap in the design research.

2.2 General problem statement

The aim of this thesis is to explore how to design a self-service technology (SST) that can improve the experience in a mid-range hotel for customers and employees.

2.2.1 Preliminary research questions

“Which aspects of existing hotel services show potential for improvement and exploration through interaction design to support a self-service technology approach?”

“How can those aspects be designed to create better experiences for customers and employees using the self-service technology?”

2.3 Target group

The design research will include co-creation methodology with the staff and stakeholders at the mid-range hotel Prins Carl in Ystad. The biggest hesitation the owners have when deliberating an SST is the loss of the personal touch in the hotel and worrying about customers not understanding what to do. However, a SST is something they recently have started to discuss, and they are curious about how an SST can be used to benefit their customers and employees, which is why they wanted to participate in this design research.

2.4 Limitations

As the research aims to design for a specific hotel context (HG8 Prins Carl) the SST design will be limited to evaluate in relation to this particular service situation. The concept and prototype will be designed to evaluate the experience and value. It is created without the calculation of cost, without the consideration if it is possible for the prototype to be further developed into a real design and implementation for the hotel.

3 Theory

In this theory section I will present existing research and studies of self-service technologies (SSTs) and co-creation strategies. The current research includes findings about attributes that drives the customer to use an SST as well as what attributes can create a positive experience for the customer.

3.1 SST experience

Matthew et.al., (2000) presents the findings of a quantitative study of what customers experience as the most common satisfying or dissatisfying attributes in SST situations. The study involved 800 customers doing a web-based survey about experiences from using a wide range of different SSTs. It included advanced well-established SSTs to the ones that are more simple or non-established. The study included questions about complaining behaviors, word of mouth and about customers willingness to use the service again. One of the biggest reasons for customers finding an SST experience satisfying is that they think it is better than the option of getting served by the service staff (Matthew et.al., 2000). This is because it saved them time in being able to get the service when they want or get the service anywhere they want (ibid). This result also relates to some of the findings of Collier and Kimes (2012) studies

that explored how important convenience is when using an SST and the need for human interaction in the SST process. Collier and Kimes (2012) result showed that for a customer to experience a convenient service it is important for them to place trust in the technology. What makes the customer trust an SST depends on the perceived accuracy, speed and being able to explore the technology (ibid). In an interpersonal service setting, the employee can easily be distracted and this might cause miscommunication. Interacting with an SST is often more accurate and is one of the most important aspects that motivates the customer to use it (Collier & Kimes, 2012). Contrary to Matthew et.al. (2000), Collier and Kimes (2012) study showed that the importance of speed was only important to regular SST users and not to first time users. How convenient an SST situation is perceived depends on the amount of resources that is required by the customer in the SST situation (Collier & Kimes, 2012). Both before, during and after the interaction with the SST. This means that the placement and environment surrounding the SST is also very important (ibid). For example, a stressful environment with a lot of traffic can have a negative effect on the customers experience contrary if it is placed at a convenient place.

It is also important for customers to be willing and have the possibility to explore the SSTs options for the experience to be more successful and convenient. This includes interacting with the SST without having to make a transaction (Collier & Kimes, 2012). To make this possible, the placement of the SST is also important in this consideration. If placed correctly at a convenient place, it can prompt customers to explore the SSTs options as well as reduce the stress during the transaction (Collier & Kimes, 2012).

Another attribute that creates a satisfying experience in an SST situation is “doing its job” (Matthew et.al., 2000). This is when a customer feels surprised and amazed by the SSTs ability to perform the required and new tasks, and in that way the customer receives a satisfying experience. It can be hard to design and create a sustainable SST with the aim of creating this kind of experience for the customer. The design needs to always be “up to date” along with the development of the technology. It is also shown in a study of Weijters et.al. (2007) that it is only customers with higher education who appreciate this experience of “new technology”. Customers with lower education do not appreciate innovation adoption and these customers may be more satisfied with an SST appearing to be “safe and tried” (Weijters et.al., 2007).

A big reason for dissatisfied customers is service-failure (Matthew et.al., 2000). Surprisingly, however, if customers encounter a technology failure they might still recommend the service to friends and family, which is not common if the failure happens in an interpersonal service setting (ibid). Matthew et.al., (2000) argues that the reason for this is probably because the customers are more accepting to failure when it is caused by technology and not service staff.

What can cause a customer to not recommend a service to others is often when the customer is not satisfied with the design of the SST (Matthew et.al., 2000). It is important for companies to focus on SSTs with better design and especially interaction design. This to give the customer the experience of accuracy and possibility to explore the interface. This is both argued by Matthew et.al., (2000) and Collier & Kimes (2012). Matthew et.al., (2012) also argues for including the customers in the design process to achieve a design that suits the customer. In addition, Ko (2017) points out the importance of addressing both the customers and employees experience when designing an SST. In contrast, Ko (2017) also claims that a fully working SST will not need an employee which will of course benefit the company but may not benefit the emotional experience for the customer.

3.2 Motivation to use SST

For a successful SST implementation, customers must be willing to try the technology. Even if the SST is well designed for customers to have a positive experience during the SST transaction, this will never happen if the customer does not have motivation to try it.

Depending on the customers previous experiences in service situations, these experiences along with exposure of advertising and word of mouth creates a preconceived view towards different service contexts that Curran et.al (2003) calls “global attitude”. He claims that this includes customers to develop a global attitude towards both specific service situations, specific employees and specific SSTs. Furthermore, this means that the global attitude creates an effect on the customers motivation to use an SST in a service setting. It may not come as a surprise that the customers with a global positive attitude towards SSTs are often motivated to try a new SST. Contrary to customers with a global negative attitude who are not motivated to use SSTs (Curran et.al., 2003). According to a study by Matthew et.al., (2005) the reason for the customers attitude can be explained by the “customers readiness”. Matthew et.al., (2005) explains the term “customer readiness” by conceptualizing it into three mediators. First, the customer needs “role clarity”, meaning the customer needs to understand what to do in the service situation. Second, the customer needs motivation. This means having a desire and wanting to receive the outcome of the service. The third mediator is ability, meaning the customer has to have the confidence and ability to use the SST (ibid). It is shown by both Matthew et.al. (2005) and Curran et.al. (2oo3) that the more experience customers have from SST situations the higher the chance is for them to be motivated to try a new SST. Because of their previous experiences they have a more positive global attitude (Curran et.al., 2003). As explained, the global attitude is influenced by the customers level of “readiness” including role clarity, motivation and ability to use the SST (Matthew et.al., 2005).

What may seem like a paradox for the companies considering investing in an SST is the fact that the customers who has a positive attitude towards employees are less motivated to use SSTs (Curran et.al., 2003; Ko, 2017). With a negative attitude towards employees this can instead increase the motivation to use the company’s SST. This can be an important knowledge for companies to consider before investing in a SST.

To increase the motivation for users Matthew et.al. (2005) suggest that it is important to use clear instructions, especially for first time users. He also suggests making it possible for customers to learn from each other while interacting with the SST.

3.3 Co-creation

As mentioned above, researchers in the field of self-service technologies (SSTs) points out the importance of involving both the employees and potential customers in the design process to achieve a design that suits them when designing an SST for a hotel (Ko, 2017; Matthew et.al., 2012). Co-design is a common design approach which can be used to involve these groups in the design process (Sanders & Stappers, 2012). The co-design approach contains co-creative methods including workshops and techniques for observation, interviews and user testing (ibid). The employees and users in a service context are the experts of their own experiences in relation to that context (Steen, 2011). The mentioned co-creative methods will help the designer understand these people’s experiences better (ibid). To design an SST that will contribute to better experiences in a hotel, the designer must understand which parts of the service shows potential for improvement. And that includes understanding the customers and employee’s current experiences in order to know where and how they could be better.

The difference with co-design compared to traditional design strategy is that traditional strategy focuses more on how to create value for a specific targeted group in the business chain, which in the end often fails to benefit all stakeholders involved (Ramaswamy & Gouillart, 2010). Co-design aims to involve all groups and therefore has a higher chance to benefit more people in the business chain (ibid). The goal of this research is to create an SST that can benefit both employees and customers experiences, which make co-design a better approach.

One of the biggest reasons for customers choosing an SST over service staff is because they trust the SST better than the employee (Collier & Kimes, 2012). To identify which part of the service where customers might experience trust issues with an employee could be an opportunity for SST design. However, it might be hard to ask customers to just explain for the design team when and where in the service they might experience trust issues. Using co-creative methods makes it easier to find where in the service this might happen because it also includes observing people. We cannot only base knowledge about people on what they say they do by having an interview, we also have

to look at what people actually are doing (Sanders & Stappers, 2012). In that way we can understand more about the desired needs and goals of the user (ibid) in order to create an SST that will fulfill these needs, resulting in richer experiences.

Co-creative methods are also useful to find diffuse problems in the service and bringing them up to the surface for exploration and discussion (Holtzblatt, 2005). For example, in every service context there is often situations that has a higher risk of causing miscommunication among the employee and customer. To understand what causes that miscommunication to happen is not always easy. The employees develop habits and do parts of their work unconsciously, so sometimes they do not notice how the problems are happening (Holtzblatt, 2005). Co-creative methods of observation and workshops can bring the unconscious situations up to the surface which makes it possible to create design solutions to the problems, making the service experience better (Sanders & Stappers, 2012). As SSTs are preferred in situations when the customer has a negative attitude towards the employee (Curran et.al., 2003; Ko, 2017), the identified miscommunication situations might benefit of an SST option instead, since SSTs can be perceived as more accurate than an employee (Collier & Kimes, 2012).

By including the stakeholders and users in the design process it will also help the stakeholders reflect up on their own situation and understand more about their own experiences and other stakeholders involved (Sanders & Stappers, 2012). Sanders and Stappers (2012) claims that all people are creative people, and by helping the stakeholders getting better knowledge about their own situation, the stakeholders will contribute to finding design problems. Later when having the ideation workshop, the designer should provide the stakeholders with tools that trigger creativeness (Sanders & Stappers, 2012). Together with the designers the stakeholders will generate ideas and solutions to the identified design problems (ibid). With that said, it does not mean that all decisions should be made as a group (Stickdorn, 2012). It is the design teams job to know which of the findings and ideas that can be used to create the best design solution for the service (ibid).

To summarize, by using and facilitating the right techniques and tools in the co-design sessions, you can make it possible for the stakeholders and customers to express their feelings and thoughts about how they experience the service and how they would like to experience it in the future (Sanders & Stappers, 2012).

4 Methods

For a well-planned design research and to understand more about the users in the co-creative methods, Sanders and Stappers (2012) mention the importance to include the “say”, “do” and “make” techniques, which all are co-creative techniques used and will be presented in this section. The “say” technique is performed by using surveys and interviews for quantitative or qualitative data, to understand what the users and stakeholders “say they do”. To understand what the users are actually doing, referring to the “do” technique, different observation methods are recommended to use. Finally, using what Sanders and Stappers (2012) call “what people make” technique is to let people involved in the design research express their feelings and thoughts, and this can be done by creating something together in a workshop.

Figure 4: Image taken from the Convivial toolbox of Sanders and Stappers (2012) say, do and make techniques. This illustration includes what methods to use in order for the user to share different levels of knowledge

With the aim of contributing to research in the interaction design field of self-service technologies (SSTs), the choice of methods is grounded on interaction design principles with the knowledge of the positive effects using co-creation methods (section 3.3) including the explained “say” “do” and “make” techniques.

4.1 Litterature studies

Before beginning the co-creative design process, getting a deeper understanding about the field of self-service technologies (SSTs), is necessary. According to Löwgren & Stolterman (2004) it is important that a designer looks at the available materials of both existing theory, methods and tools, and use that information to be thoughtful in how to create designs. When aiming to design a better experience for customers and employees, the existing research explained in the theory section has helped arrive at a deeper understanding about which attributes SSTs could entail in order for it to have a higher chance of creating positive experiences and be motivating to use.

This knowledge from existing research about SSTs has on certain aspects influenced the design of the prototypes.

4.2 Interviews

When designing a new solution to a specific context, all design research should begin with understanding the company and the kind of service you design for (Cooper et.al., 2014). Interviewing the stakeholders is necessary and especially important in the beginning of the project before the research phase begins (ibid). There are different kinds of interviewing techniques to use for gathering the best information depending on the desired goal and outcome of the interview. In this thesis, semi-structured interviews were the technique most frequently used. Other interviewing techniques were also used that will be explained later in the observation section.

Semi-structured interviews contain both open-ended and closed-ended questions, with the aim of gathering more information about a specific topic while still make it possible to explore other topics that might come across (Galetta, 2013). Furthermore, in semi-structured interviews you can collect both quantitative and qualitative data (Wilson, 2013), which make them very useful and flexible. In relation to service design, they are recommended to be used when you want to get better understanding about work flow, daily tasks and touchpoints (Wilson, 2013). In addition, you have the benefit of gathering information about attitudes and options (ibid), which can be useful when testing a prototype with real users.

4.3 Survey

Surveys are a great way to collect quantitative information about certain customer groups and compare people’s information on demographical variables (Cooper et.al., 2014). That means for example to compare gender, age and education or to target a specific group in the survey to find more information about that customer group. To get an overview from a certain customer group about how much of something they are doing or experience a web-based survey can be very useful (Cooper et.al., 2014). In addition, a quantitative survey can help with seeing patterns of opportunities in the field you design for, based on its customer group (Cooper et.al., 2014).

4.4 Observations

One of the best ways to get a holistic perspective of a service is to spend time where it takes place and observe, gathering deeper understanding about the staffs and customers interactions (Stickdorn, 2012). When observing, it is in most situations not recommended to just be passive and present at the observation. Instead, methods of shadowing including contextual interviews are recommended methods, which were used in this research. Stickdorn (2012) recommends shadowing a staff and look at all interactions they do

continuously. This so you can notice when problems occur, and especially those problems that might never be addressed by the staff or customers themselves (ibid). Because the employees have developed habits and doing parts of their job unconsciously it is hard to describe in words and detail what they do at work (Holtzblatt, 2005). And one of the goals with observation is to notice these interactions and problems that might happen without the employee’s knowledge (ibid). This also explains why interviews outside the service context is not enough.

4.4.1 Contextual interviews

To get deeper knowledge about the service and employees while observing, the design team can ask the employee questions while they are working, called contextual-interviews (Stickdorn, 2012). You might for example notice something unexpected or something that you do not understand. It is important to ask the employee to explain what they are doing and why (Holtzblatt, 2005). The chance of getting deeper discussions about the service also arises when the designer and employee are being present in the real service setting. This is because they are surrounded of the actual service context, including all the tangible objects and touchpoint that are parts of the service (Stickdorn, 2012). In addition, people express themselves better in a surrounding they are comfortable in (ibid).

4.5 Workshops

For the stakeholders and designers to get closer to their shared goals and visions, planning and facilitating workshops is known for being a great co-creative method (Muller & Durin, 2010). To target the intended goal of the workshop, the designers and researchers should plan the workshop with the right techniques and tools (ibid). A workshop can be used for many intentions, for example developing new concepts together or creating an artifact that can be used later in another workshop (ibid). It is also a great way to engage the stakeholders in the design process (Muller & Durin, 2010). The value of participating in the workshop can also be for other reasons than to contribute in the design process. It can be personal or psychological to (Ramaswamy & Gouillart, 2010). For example, getting better satisfaction at work, self-esteem or appreciation (ibid).

In a workshop, people come together with different backgrounds and personality, which sometimes makes it harder to communicate and understand each other (Sander & Stappers, 2012). But by using the right tools and techniques in the workshop, it creates a common language, making it easier to communicate and share your thoughts (ibid). In that way the stakeholders and designers have a greater possibility to share knowledge and learn from each other (Muller & Durin, 2010).

4.5.1 Future workshop

The second workshop that was created in this design research was inspired by the well-known workshop method called “future workshop”. This is used when the design team and stakeholders need to clarify what the problems are in their current service situation and generate ideas and solutions to those problems (Biskjaer et.al., 2010). Also, how the possible solutions that where generated can be implemented in the service (ibid).

4.6 Analysis and mapping

The collected material from the interviews, observation and workshops can by being analyzed and mapped out make the information more visible in order to identify opportunities for design innovation (Stickdorn, 2012). By abstracting the service and its users using interaction design models, it can help communicating what the user group wants and needs (Cooper et.al., 2014).

4.6.1 Stakeholder map

In service design, it is recommended to create a stakeholder map to get an overview of all people and organizations involved in the service (Stickdorn, 2012). This is often done in the earlier stage of the design process, when you need to understand each stakeholder group better including their importance and relationship to each other (ibid).

4.6.2 Blueprint

To specify relevant elements and interactions among the people involved in a service, the service blueprint can be created to make this more visible (Stickdorn, 2012). The service blueprint contains what is called “line of visibility”. It visualizes what parts of the service has direct contact with the customer, frontstage, and which parts of the service is done without interaction with the customer, backstage (ibid). This can give the designers and stakeholders a better understanding of the responsibilities of each staff member. The blueprint may also reveal where in the service there is duplication or room for design improvements (Stickdorn, 2012).

4.6.3 Personas

A “persona” is a fictive person that is created based on the collected findings of the user group you aim to design for. Personas is a very powerful model that helps communicating how the user group thinks, acts and why they act or think like they do (Cooper et.al., 2014). This is a good tool to use when you want to imagine how the user group would interact with your design, why they would use it and how they would experience it. According to Cooper et.al. (2014) if you try to imagine this about the users but you base it on all of your collected information, perhaps tons of notes on paper or different graphs, it will be much harder to make the right design decisions. That kind

of tons of information can also be much harder to communicate with the stakeholders (Cooper et.al., 2014). Instead, the persona communicates the user group in an understandable and quick way, making it easier for everyone involved in the design process to understand the user group’s needs, which helps keeping the users experience in focus as the project moves on (ibid). Furthermore, it is important to create the persona purely based on the research findings and respect of the user. This so you do not end up adding personality traits based on assumptions, making the persona a “stereotype” (Cooper et.al., 2014).

4.6.4 Customer journey

A customer journey map is a map created to visualize the customers journey when using a service (Sanders & Stappers, 2012). It can be used to help the design team and stakeholders understand the customers total experience of the service better (ibid). In the customer journey it is common to use a persona (section 4.6.3) to represent the person in the journey of the service. This makes the customer journey more realistic to real customers emotions and actions and a great tool to visualize where in the service there can be improvements with a design innovation (Stickdorn, 2012).

4.7 Prototyping

The biggest reason for why designers creates prototypes is for testing certain parts of the design concept with the aim to evaluate and understand what works and what needs to be improved in order to suite its intended users (Valentine, 2013). The design team can then make adjustments on the prototype, based on the feedback when it was tested, called iterations (ibid). When describing prototypes among designers, it is common to use the phrases of low-fidelity or high-fidelity prototypes. Low-fidelity prototypes are created on cheap materials, often by just using drawing and cut out paper (Lim et.al., 2008). This makes them very flexible, as it is quick and easy to makes changes on them while you explore and try them out. The low-fidelity prototypes are in most cases not used for exploring the interaction of the design (Rudd et.al., 1996). Instead, it is used for exploration of the concept, possibilities and the screen layout (ibid).

Compared to the low-fidelity prototype, high-fidelity means that the prototype often looks and feels like the real product and are fully interactive (Rudd et.al., 1996). However, if you want to explore a certain function of the prototype you can choose to only make parts of the prototype in high-fidelity (ibid). Lim et. al. (2008) also describe this as making prototypes as “filters”. He means that you can mix low and high-fidelity to highlight certain parts of the prototype, which make it easier to receiving feedback on the intended parts of the design or concept. This method was used in this design research, and this is why the final prototype is called “mid-fidelity” prototype, as only parts of the functions are made in high-fidelity.

4.8 Ethical considerations

All methods used in this design process has followed the ethical guidelines according to Good Research Practice (2017) by the Swedish Research Council. The stakeholders were informed about the research project before participating and that all gathered information and documentation will be used for research purposes only. In every co-creative session, the participants where reminded about their rights and that they could stop participating anytime. If they do not want to answer a question or participate in parts of the planned activity they do not have to. All people involved in this project has gave oral consent to participate in the research and the people who appears in pictures has orally approved.

5 Design process

In order to know when and where in the design process the mentioned methods above should be applied, my design process has followed the Double Diamond design process. The Double Diamond design process is divided in for stages. Discover, define, develop and deliver (UK Design Council, 2018). To explain, this research starting point is the general problem statement of

“how to design a self-service technology that can improve the experience in a mid-range hotel for customers and employees”. Then the research begins

its first phase, discovery, where collected insights to the problem statement is made. In the next stage, define, I am analyzing the insights to defining the design problems, and that in turns opens up into the next phase, develop, where concepts and prototypes are made and iterated. The last stage is

delivery, which means finalization and implementation of the product (UK

Design Council, 2018). Since this is a thesis design project that aims to explore and contributing to the research field of interaction design, this part is not included. However, possible future directions are mentioned later in the discussion section.

Figure 5: Illustration of the Double Diamond design process

5.1 Semi-structured interview

As this research aims to explore how to design a self-service technology (SST) at the existing mid-range hotel Prince Carl in Ystad, I began the discovery phase with having a semi-structured interview to learn more about this particular service context. As mentioned in the method section, a semi-structured interview can be very useful when you need to learn more about overall work-flow, daily tasks and touchpoints (Wilson, 2013).

The interview was performed with the two hotel owners and conducted in the lounge area of the hotel. I prepared 30 questions that where asked regarding the hotel in general and questions that were more open for further exploration (see Appendix 1 for all prepared questions).

5.1.1 Interview findings

Prince Carl Hotel has 22 rooms and is positioned in central town of Ystad. The staff working at the hotel consists of the two owners themselves, two cleaners, two reception managers and one bar staff member. Summer is the hotels high-season where they often are fully booked. Their primary customers are 50+ on leisure or workers. In winter time, low-season, it is mostly workers but sometimes couples going to an event. Most of the customers uses booking.com when making a reservation, the next popular booking method is by calling front desk. The reception is always open at check-in time 15.00-18.00 and in the mornings until 12.00 for breakfast and check-out. As they are not a big hotel, they do not provide 24-hour reception. The reception is located in the hotels bar HG8 where they serve drinks and simpler food. At weekends the bar and reception are also open later in the evening. Moreover, this were some of the information collected from the

more general questions, a necessary starting point to know the basics of the hotel´s rules and service.

Questions were also asked about the owners, employees and customers experiences. According to the owners, many customers are very positive when arriving, entering the hotel and complimenting the reception area. However, the owners still think that something about the concept of the reception is not working but they had a hard time pin pointing to what that was. Customers who are unhappy when arriving, is often the ones making the reservation through booking.com. According to the owners many guests do not read the information on booking.com and gets disappointed when they arrive. The customers disappointment in this case is often that the room was much smaller in size or that the reception is not opened 24 hours.

The owners described a satisfying experience at work when they turn an unhappy guest to a happy guest. Another is when the employees know what to do and when working together.

One big insight from the interview was getting more knowledge about the staff members roles in the service and which other stakeholders that the service has a relation to. This is an important knowledge when working with service design because you need to understand the different relationships among the stakeholders (Stickdorn, 2o12). The insights were used to create a stakeholder map to get a visual overview of all stakeholders related to the hotel service. The underlined external stakeholders are the ones that the primary service is very dependent on.

Figure 6: Stakeholder map of Prince Carl Hotel

5.2 Observation

Moving forward in the discovery phase of the design process, 3 days of observations were made at the hotel. The observation had to take place over a few days to have time to observe both frontstage and backstage services. Frontstage referring to direct customer contact duties of check-in, check-out and breakfast. Backstage refers to what happens without contact with the customer. For example, cleaning the rooms, ordering and booking systems. This is necessary to observe in order to get a holistic perspective and gathering deeper understanding about the staffs and customers interactions (Stickdorn, 2012). The observation included shadowing two reception managers and one of the cleaners. While observing I also used the technique of contextual interviews.

To capture the environment and physical work space I took photographs (Appendix 2) and to remember important information I took notes. I did not use a computer as that can cause a barrier between the employee and designer who is observing (Holtzblatt, 2005). It is also better to use notes in order to move around freely and follow the staff member (ibid).

5.2.1 Check-in observation findings

On a normal check-in day between 15.00 and 18.00 one reception manager works alone in the reception and bar. The duties of the employee include checking in guests, taking payment for the room and giving necessary information to the guest about breakfast times, opening hours, room number and possible questions. Their job is also to take orders in the bar, answering calls and sometimes preparation for the breakfast next day.

Figure 7: Reception and bar area at Prince Carl Hotel

The most common questions from the guests at the time of observing the check-in was mostly about parking. As the hotel does not provide a parking space and is located in the middle of central Ystad, many guests wanted this information including the prices of the parking lots. Two guests did ask about this twice, as they had forgotten the information they received from the employee while taking their luggage up to the room. While checking in, many of the guests parked just outside the door, and after checking in and leaving their bag, they went back to their car to find a parking space. The staff member working while I was observing said as a joke: “I sometimes feel like

a flight attendant, showing the guest all the different directions where they can park”. Another common question from the guests was about

recommendations where to eat.

One customer came back after he had checked in to his room and was unsatisfied about the room temperature. The employee solved the guest problem by placing an extra element in his room.

As I was observing in low-season, I noticed that there was a lot of professional-workers staying at the hotel. This was also mentioned earlier in the interview with the owners that professional-workers are their main customers in low-season. Many of these customers asked about breakfast

time as they needed to leave early in the morning before the hotel’s stipulated breakfast times. These guests where then offered a breakfast bag instead, and most of the guests seemed happily surprised that their issue was resolved. The employee who was working at check-in also prepared the breakfast bags and put them out in a refrigerator in the general area of the hotel. In this area, the hotel also provided an automated coffee machine so that guests could make themselves a free coffee at any time.

While observing, I took the chance to look closer at the hotels booking and cashier system. They use Sirvoy as their booking system and iZettle as cashier system. Their booking system Sirvoy is connected to external booking providers as well (booking.com and expedia.com). At check-in they mostly used the booking system for getting a visual overview of how many guests were checking in and for registration when the guest has checked in and paid.

Figure 8: Overview of today’s guests in Prince Carl Hotels booking system, Sirvoy.

5.2.2 Check-out observation findings

At check-out and breakfast time there was one employee working in the reception, who alone was responsible for the breakfast and customers checking out. She started her shift 06.45 and ended her shift 12.00. At 10.00 the second employee started her shift which was the cleaner, responsible for cleaning the rooms. The use of the hotels booking system Sirvoy was also frequently used at check-out and breakfast. The employee starting 06.45 looks in Sirvoy to see how many guests are having breakfast and how many guests are checking out. The employee preparing the breakfast buffet told me that she always looks how many guests are having breakfast because sometimes when there are only a few guests, she does not prepare the hot food, scrambled eggs and bacon. Instead she walks up to the guests and asks them what they would like. This so she can serve the food fresh and give them a better experience while at the same time not throw away unnecessary food.

From my observations, the breakfast seemed to be working well and the guests appeared to be relaxed and happy. However, there were other problems with some of the customers checking out. For example, the guest from the day before who had complained about the cold room wanted a refund as he where still not happy. This made the employee nervous and then called the owner for help. The situation could not be resolved right away, and the employee told the guest that the owner where going to contact him later. The cleaner who started at 10.00 began her shift with asking the employee in the reception about a printed list of the rooms to clean. As I had seen the hotels booking system the day before, I knew that the information the cleaner wanted to be printed out could as well be found in the system. The cleaner told me that she does not like using the Sirvoy system, as she is not a big fan of technology. So, she prefers to get the information printed out instead. However, this contributed to more work for the other employee working in the reception. As the printed paper cannot be updated while new rooms get available to clean during the day, the reception employee had to send a text message to the cleaner every time a guest checks out. The employee however did not mind that little extra time of work she said; “as long as everything works for both of us it is no problem for me”.

5.2.3 Service blueprint

After 3 days of observations and the previous interviews, I was able to use the collected information and create a Service Blueprint. The intention of creating the Service Blueprint was to visualize all the interactions that must take place in order for the overall hotel service to function (Stickdorn, 2012). It can also be useful to understand where in the service a possible self-service technology (SST) can take place.

Figure 9: Service Blueprint of Prince Carl Hotel

5.3 Analyzing customers

As the interviews and observations had given me the knowledge about the hotel´s customer groups (50+ and workers), I was able to target the group of 50+ guest, when using a web-based survey. The aim of the survey was to understand the customer groups experiences of hotels, and their use of technology in general. The information from the survey could help in understanding more about the possible opportunities of design innovation and limitations related to the customer group (Cooper et.al., 2o14). As the survey was only based on 20 people, it could not be fair to use the survey as a ground to base the findings on “average customers over 50 years old”, but it helped in understanding more about some of these people’s experiences about hotels and technology. Therefore, the survey where mostly used for gathering qualitative findings and inspiration.

Most of the customers at Prince Carl hotel uses booking.com when making a reservation which made it possible to analyze received reviews from guests. Some of the answers from the online survey (Appendix 3) that considered hotel experiences was compared to the reviews on booking.com, to see if there were similarities.

Furthermore, in the first workshop these findings were presented to the staff and stakeholders which were discussed. As they are the experts on their customers, their knowledge has the most value.

5.3.1 Survey and review findings

Some of the findings from the online survey where quite obvious. For example, the most common reason for people remembering an exceptional experience from a hotel stay is that they´ve got more than expected. In many cases it could be getting a nicer room or super friendly staff. On the opposite, the reasons to be disappointed in a hotel stay where much more unique and widespread. However, comparing some of the answers from the survey to bad reviews on booking.com I noticed some similarities. A reason for people getting disappointed in a milder sense, was when they experience the hotel to lack personality or when the room looks boring. On another note, reading the reviews on booking.com, I saw a pattern of many people giving quite low rating even though they seemed happy and founded value of the stay. It seemed from the reviews that some guests got what they expected but nothing extra, and that might be the reason for a lower rate.

According to the online survey, 85% of the people who answered said that if there is something they are not happy with while staying at a hotel, they will go down to the reception and tell the staff immediately. This was later discussed in the first workshop and not agreed by the staff members. According to the staff at Prince Carl Hotel, in many cases the customer just leaves a note or tell them at check-out. This result could be one of those things people say they do, but in reality, they do not. This insight shows the importance of why you cannot count on all the information collected from a survey, as it is only based on what people “say they do” (Sanders & Stappers, 2012).

Questions were also asked about the use of tourist information while staying at a hotel. The result from the survey showed that the use of tourist information was through multichannel options. Most people choose the alternative of both asking the staff and looking for themselves at the internet. This was confirmed to be correct according to the staff’s perception at Prince Carl Hotel. Also, my own perception from the observation as many guests were asking questions about parking and restaurant options.

The results regarding the customers use of technologies such as self-scanning in grocery stores and preferring a mobile ticket instead of a physical ticket, where commonly used. However, using a QR code was not common and many people did not know what it was.

5.4 Workshop 1

The goal of the first workshop was to create two personas, fictive users (Cooper et.al., 2014), that should represent the hotels main customers 50+ and workers. The workshop was also conducted to make the stakeholders feel included in the design process (Muller & Durin, 2010).

The workshop was held in the lounge area at the hotel after 12.00 when reception was closed. This made it possible for all stakeholders to participate, both owners, reception staff and cleaners. The workshop was structured in two phases. First, a discussion about their main customers. And second, everyone got to create their own persona.

The workshop began with me presenting my own insights concerning their customers, which was based on my observations, survey and the reviews on booking.com. The insights where presented one by one, so that we were able to discuss each point together. By doing this the stakeholders could add necessary information to the insights as they are the experts of their customers.

As mentioned earlier from the survey insights, there was particular one insight that was not agreed by the staff members, which was the customers actions when they are unsatisfied with something during their stay (section 5.3.1). However, all the other insights that were presented seemed correct and were also confirmed during the discussion. The stakeholders often recalled situations on each insight and gave examples of when some of them had occurred and how often, which helped me as a designer know how relevant each insight was.

On the second part of the workshop I had planned for each stakeholder to create their own persona based on the previous discussed insights of their customers. I told the stakeholders about the meaning of making a persona and explained that the goal is to write about the persona in a way that it feels like a real guest staying at the hotel. By using physical paper, pens, pictures and a form that was free for interpretation, this part was supposed to be fun and creative for them. The form was designed with unfilled boxes and columns, including explanation to what to write in each column. The pictures where cut out of randomly people and placed out on the table for the stakeholders to choose and attach on the form. There were no problems in understanding the task but there were questions on what to write about in each column. I explained to the participants that they should feel free to use the form how they like and if they do not fill in all parts they do not have to. It was more important to highlight the personas goals and frustrations. Goals are especially important as you want the design to benefit the users goals (Coopet et.al., 2014). The stakeholders seemed to have fun when participating and the pictures used showed to be a very good tool in evoking creativity and imagine what type of hotel guest it could be. Finally, we decided to keep 2 of the created personas to represent their main customers. One representing a high-season guest, 50+ and one representing a low-season guest, a “professional-worker”. The personas were created to be used in the next workshop and to keep the focus on the hotel guests throughout the design process.

Figure 10: Stakeholders creating personas in Workshop 1

Figure 12: Second persona, representing the “worker” group.

5.5 Workshop 2

The second workshop was inspired by the method called “future workshop”. A workshop like this often takes a few hours and is divided in three phases, first, identify problems or find opportunities in the service, second, come up with ideas, and last, how could the ideas be implemented in the service (Biskjaer et.al., 2010). The goal of this workshop where therefore to explore the preliminary research questions to this thesis general problem statement. First, “Which aspects of the existing hotel services show potential for

improvement and exploration through interaction design to support a self-service technology approach?”, and second, “How can those aspects be designed to create better experiences for customers and employees using the self-service technology?”.

The workshop was conducted at the same place as the first workshop, at the lounge area of the hotel. The participants were the same staff members as the first workshop, except another cleaner and one reception manager that could not participate.

5.5.1 Identifying problems

To explore the first phase of identifying problems or opportunities in the service I had prepared a big paper sheet that was going to be used for creating

two customer journeys. A customer journeys main use is to visualize where in the service there could be improvements (Stickdorn, 2012). As this design research aims to explore how to design a self-service technology (SST) that can improve the experience, a customer journey is very useful to understand how the customers feel and experience different parts of the service (Sanders & Stappers, 2012). The customer journey was based on the two personas made in the first workshop, that represents the hotels main customers. To highlight the emotions in the customer journey I used smileys which where representing the “emotional line”. The stakeholders where handed two different colored post-it’s that was going to be used for each persona. Each post-it where then used to represent a touchpoint and placed out horizontally on the timeline and vertically on the emotion line. The reason for having both personas on the same paper sheet was for it to be easier to visualize where in the customer journey their where similarities or differences on the personas emotions, and this could perhaps contribute to finding design opportunities that can benefit both customer groups.

Figure 13: Customer journey based on the two personas, 50+ and worker.

After creating the customer journey, we discussed the result together with the aim of finding opportunities for design innovation with an SST. This however also resulted in the stakeholders slipping away from the subject and discussing other parts of the service. As I wanted the stakeholders to be comfortable and feeling free to express themselves during the workshop I did not interrupt the other discussions right away. Luckily, this contributed to even more knowledge that was not clearly explained in the customer journey. For example, one issue discussed was about customers questions and problems. As the hotel closes their reception at 18.00, the guests staying at the hotel often calls after this hour when they have questions or problems, which often is inconvenient for both the customer and employee. Another problem that was brought up to the table and discussed was about customers

misunderstandings, addressed earlier in the interview findings (section 5.1.1.). Many customers making their reservation on booking.com do not receive all information, which make them misunderstand what they have booked and get disappointed when arriving. The visualization of the customer journey helped the stakeholders to come up with a solution to this problem, to send out a text message to the guest before they arrive. Both right after they have made the reservation through booking.com and also the day before people arrive at the hotel to prevent misunderstandings.

Another issue that we started to discuss was about the guests who wants to check-in after 18.00 when reception is closed. For the guest to be able to enter the hotel and get the key, the guests have to call the owner. But before receiving the code the guest must leave his or her card number by phone including the CVV code for security reasons. Many customers do not feel comfortable telling their whole card number by phone, so this was something the stakeholders wanted to change.

Finally, we identified that check-out and breakfast is the phase of the journey that both customer groups are most satisfied with. The most critical phase for both groups is when checking in and while staying. For the 50+ customers we saw potentials when arriving considering the touchpoints of parking the car and having questions or problems after reception is closed. As the “worker” customer group often arrives late and leaves early in the morning, we saw potentials in both answering questions when reception is closed and improvement of the check-in process after 18.00. Perhaps also how to make their visit less lonely since they often do not get the chance to meet anybody during their stay.

5.5.2 Ideation

The next phase of the workshop was to come up with ideas to improve the identified parts of the service with the help of an SST. As the stakeholders might not have the same knowledge about SSTs and what they are capable of as a designer, I had printed out pictures of a wide variation of SSTs and technology to help them see the possibilities with SSTs and get inspiration. The stakeholders where free to choose if they wanted to draw or just express their ideas. The ideation ended up in an open discussion together where one staff member and me as a designer did quick sketches on the ideas that where discussed.

Figure 14 Sketches of ideas and inspiration photos

Together we decided on 2 ideas about SSTs that we wanted to explore in the last phase of the workshop. Both the stakeholders and me as a designer saw potential in how these SST concepts might improve the experience for both the customers and employees.

5.5.3 Concept 1

The guest can use an SST for late check-in.

Instead of having to tell their card number by phone, this service could be provided through an application instead. It would probably feel much more trustworthy for the guest to type in the card number in an application. It would also be possible for the guest to get an immediately confirmation and receiving the code to the door and key box through the application. This may increase the customers experience of trust for the service and relieve some of the work load for the staff who normally have to do this service by phone after closing hours.

5.5.4 Concept 2

A “fun” SST kiosk with information placed inside the hotel.

Creating an SST kiosk with the intention to help customers improve their hotel experience by giving them information they might be looking for. Also, the possibility to explore the SST, finding other “tips” that can improve their visit.