1 FACULTY OF EDUCATION

AND SOCIETY

Degree Project with Specialization in English Studies in

Education

15 Credits, Second Cycle

Canon VS No Canon

Which English Literature is Used in Swedish Upper

Secondary Schools?

Kanon vs ingen kanon - Vilken engelsklitteratur används i den

svenska gymnasieskolan?

Emy Arnekull

Makrina Pesa

Master of Arts/Science in Secondary Education, Examiner: Shannon Sauro 300 credits

Major in English Studies in Education Supervisor: Björn Sundmark 28 May 2018

3

Foreword

This degree project has been equally conducted by us. Together we have been reading literature, conducting interviews and the survey, collecting and comparing data, and writing the distinct parts, that is: introduction, theoretical background, method, results, discussion, conclusion, and abstract.

We hereby state our equal contribution to this degree project.

4

Abstract

Throughout our teacher education, we have seen and felt the need for suitable literature in the English courses for upper secondary education in Sweden. Our purpose was to investigate which literature teachers in the field are using in their different courses, and with that constitute a list that can be used by teachers. Furthermore, we also investigated, among other things, which qualities the teachers are looking for when choosing suitable literature for their students and courses. Previous research has shown the significance of using literature for language and cultural development, and therefore a list as ours can contribute to aiding upper secondary teachers. To execute this research, we have chosen to use both a qualitative and quantitative method, in the form of a survey and interviews. Our results showed that all teachers are using some sort of literature for language development, and the vast majority are having difficulties finding suitable literature for their students. Moreover, the vast majority of our interviewees took a negative stand towards having an official canon, however they were open for using an unofficial canon as inspiration.

Key words:

5

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ... 6

1.2 Aim & Research Questions ... 7

2. Theoretical Background ... 8

2.1 Definition of Concepts ... 8

2.2 Previous Research ... 8

2.3 Significance of Using Literature for Language and Cultural learning ... 9

2.4 Official Canon VS Unofficial Canon ... 11

3. Method ... 13

3.1 Choice of Methods ... 13

3.2 Participants ... 14

3.3 Contexts and Procedures ... 15

3.4 Instruments ... 16 3.5 Ethical Considerations ... 17 4. Results ... 18 4.1 Survey ... 18 4.2 Interviews ... 21 5. Discussion ... 23 6. Conclusion ... 27

6.1 Limitations and Future Research ... 27

References ... 28

Appendix 1: The Complete List ... 30

Appendix 2: Survey Questions ... 44

6

1. Introduction

What to read about, and why, have always been significant questions in the literature education. (Langer, 1995, p. 143)

Throughout our teacher education, there has always been insecurities pertaining to which literature we can use in our future English as a foreign language (EFL) classrooms. Even though we have received insights as to which literature we can use, we, and our peers, have felt the need for a more extensive list. Our insecurities stem from the fact that the use of English literature should be included in all of the English courses for the Swedish upper secondary school system; for example, the core content for English 5 states that the students should receive “literature and other fiction”, the core content for English 6 states that the content of communication should contain: “themes, ideas, form and content in film and literature; authors and literary periods.”, and for English 7, the students should receive “contemporary and older literature and other fiction in various genres such as drama.” (Skolverket, 2011). In addition, we have also seen other teachers’ need for inspiration on different social media platforms for English teachers in Sweden. On these platforms, we have frequently seen teachers ask which literature to use in the different English courses, which again show a significant need for guidelines.

There is evident need for literature in schools. According to Lundahl (2012), the need for literature education is almost self-explanatory; it is, for example, a reliable source for intercultural learning as well as understanding other people’s perspectives (p. 403). Lundahl (2012) further argues that literature not only improves the students’ language knowledge but can also be used as a tool for solving conflicts (ibid.). Additionally, there has been a significant decline in Swedish students’ reading ability (PIRLS, 2006). This further suggests that there is a need for relevant and suitable books to be used in upper secondary education that will inspire and motivate students to read. Our list will show which books are frequently used in Swedish schools, and this will also indicate which books are appreciated by the students, and thus motivate them to improve their reading and language proficiency (Persson, 2007, p. 219).

With this as our foundation, we want to provide English teachers in Sweden with a literature list. Therefore, we have investigated which books are frequently used by English

7

upper secondary teachers in Sweden. This list can be used as a guideline and asset for newly graduate teachers who, like us, are questioning which books are suitable to use in the different courses, and also for experienced teachers who are looking for new material. However, we would like to stress that our aim is not to advocate for a mandatory canon in the curriculum for English, we only want our list to be used as inspiration and as a guideline since we have seen the need for it.

1.2 Aim & Research Questions

Our purpose with this degree project is to investigate which literature is used in Swedish upper secondary schools, as well as how it is used. This is because the syllabus for English does not state which literature the teachers should use, and therefore there can exist uncertainties to which literature is suitable for the students and their language proficiency. The aim is to create a list of the literature that is being used in the Swedish schools in order to minimize the difficulties of choosing literature for the teachers, but also to improve the English education in terms of using literature that is relevant and interesting for the students.

Research Question:

1. Which literature is used for English studies in Swedish upper secondary schools?

Sub-questions:

1. How do the teachers motivate their choice of literature?

8

2. Theoretical Background

In the following chapter, we will present previous research and theory on the significance of using literature in language classrooms, but we will also discuss the relevance of having a canon.

2.1 Definition of Concepts

When we decided to focus on literature, we had to limit the concept. With that in mind, we decided not to include all type of literature, therefore by literature we mean novels, books, and biographical novels. That is, not course books or other textbooks. This decision is based on our interest in only fictional books.

Furthermore, in this research we have used two different terms for canon. An official canon pertains to a list of literature which must be used in schools. It is then issued by, for example, the government, and is therefore compulsory for teachers to use in their education. For example, in Denmark they are using an official canon, which is compulsory for the teachers to use (Danska Lärarföreningen, 2015). What we define as an unofficial canon, on the other hand, is a compiled list of literature which is not compulsory, and therefore can be used solely for inspiration or not at all. Our list that we have conducted is similar to an unofficial canon, which contains the actual books that are being used by teachers.

2.2 Previous Research

It is not only in Sweden where difficulties finding appropriate literature in education has been seen; it has also been noticed in, for example, the US. Every year, the International Literacy Association (ILA) compiles a list of literature used by teachers. Their reason for constituting a list is because they want to provide teachers with suitable books to inspire their teaching and also their students. This research inspired us to provide a similar list to inspire and help English teachers in Sweden.

Research has shown the significance of reading complete novels in language education, which Econoumo (2015) argued for when she conducted research where she investigated how students interact with a modern Swedish novel. Her results showed that using novels for

9

language development and acquisition is vital for personal development, cognitive development, and language development. Furthermore, she concludes that students should encounter a wide range of different types of literature, for example, novels from different authors and with differing themes (p. 114-115). This shows that letting students read complete novels in their education is to prefer. Furthermore, since Economou stated that students should encounter a wide range of books, a list such as ours can help teachers to easier choose between suitable books and provide their students with multiple novels.

2.3 Significance of Using Literature for Language and

Cultural learning

There are reasons for preferring literature over textbooks. Our reason for choosing to focus on literature is because we believe that literature has positive effects on the reader, and therefore choosing suitable literature for the different courses becomes vital. As Carroli (2008) states, literature does not become outdated, and it minimizes the risk of presenting cultural stereotypes as textbooks usually do (p. 184). Moreover, another reason for choosing literature is because it advocates for extensive reading because of its positive effects on expanding vocabulary and language proficiency (Rings, 2002, p. 167).

Literature offers students possibilities to view the world, situations, cultures, and themselves with a wider perspective. According to Papadima (2009), when a reader identifies with, for example, a character, they can receive new insights through the story, and thereby gain new perspectives of the world. Papadima (2009) explains it by emphasizing the vital perspectives gained through sharing experiences with the text: “greater empathy, tolerance and ability to understand not only human nature, but also diverse cultures and values” (p. 121). She also cites Sartre (1967) who claims that reading literature helps students interpret the world in new and creative ways (in Papadima, 2009, p. 120). In accordance with Papadima, both Molloy (2003) and Langer (1995) argue that students, through literature, gain wider acceptance of other peoples’ ways of thinking and life situations (p. 318). Furthermore, Langer (1995) states that through the use of literature, students learn to envision both their own and the human race’s possibilities: “they become the literary thinkers we need to create the possibilities of tomorrow” (our translation, p.13). Lundahl (2012) explains that literature

10

creates a meeting-place for diverse cultures: “Literature makes it possible to meet people and understand historical, economical and social relations from different parts of the world. [...] That way, literature enables continuous exchange of perspectives” (our translation, p. 404). This is in accordance with Skolverket, where Osbeck (2016) argues that when reading literature, students are provided with opportunities to gain new perspectives and acceptance of the world which they otherwise never would encounter.

Reading literature in schools can help students strengthen themselves as well as their identity and doing this will also help their language proficiency. Papadima (2009) argues that reading stories of others will help us to make sense of our lives, and that it is a “vital role in the pursuit of identity” (p. 120). In other words, understanding the literature that the students are reading will help them to better understand themselves (ibid.), and this is due to what we previously discussed; that is, being able to view the world from other perspectives. Literature helps us to not only see ourselves clearly, but it also gives us the possibility to create new versions of and to understand ourselves (Langer, 1995, p. 17). Also, Cummins (2001) states that identity in literature is of importance for students’ foreign language acquisition (in Economou, p. 94). When students identify themselves during their reading about the characters and situations in the books, their language skills will develop (ibid.). Furthermore, Persson (2007) also discusses that literature has always played a significant role in recognition of identity (p. 223).

In the fundamental values in the Swedish curriculum, it is stated that the school has an obligation to educate students to become democratic members of society (Skolverket, 2011); “the education should mediate and anchor firmly established respect for human rights and the fundamental democratic values which the Swedish society rests upon.” (Skolverket, 2011, p. 5, our translation). As Persson (2007) argues, literature in schools can develop students’ democratic thinking. Also, Langer (1995) claims that literature, and the fantasy offered by it, gives the students possibilities to become more thoughtful; to create new combinations, alternatives, and possibilities in order to understand new characters and situations, and thereby become better informed democratic citizens of the world (p. 21). In other words, to strengthen the fundamental values in students, literature can be used as a useful tool to do so.

11

It has been shown that reading literature in schools has positive effects on language acquisition and language proficiency. Lundahl (2012) claims that reading literature is fundamental for developing language skills (p. 403). In addition, literature creates meaning, vocabulary building, as well as possibilities for social interaction between peers, which in turn develops language proficiency (p. 404). Furthermore, Bradford (2006) also argues for the importance of using literature as a tool for language acquisition (in Economou, 2015, p. 101). Moreover, as Lundahl also advocated, reading literature provides the students with both vocabulary and specific syntactic patterns (ibid.). All of these factors show the positive aspects for using literature to develop students’ language acquisition.

2.4 Official Canon VS Unofficial Canon

There has been a division regarding the implementation of an official canon. According to Maley (2001), a classical canon has been highly criticized because of the lack of feminist and gay writing (p. 181). A standardized canon can therefore hinder the teachers, since they cannot include all of the valuable literature to teach fundamental values. Furthermore, Brink (2006) also concludes that a canon usually contains predominantly male, white, and western authors (p. 28). He also argues that a canon will provide limited perspectives for the readers, as well as often being nationalistic, which can lead to problems in such a multi-cultured country as Sweden (p. 29). Brink (2006) states that, even though a literary canon should represent modernity and various perspectives, it still fails to do so: “the main idea of a literary canon should stand for continuity, history, cultural heritage, and tradition. But still the canon is not unchangeable” (p. 29). In other words, even though the canon can change over time, it still has problems achieving a varied depiction of the cultural representations of modern times.

Moreover, there has been a political discussion in Sweden regarding the use of a literary canon. This has mainly concerned the subject of Swedish, but we regard it as relevant to the subject of English as well, since literature is used as much in the English upper secondary courses as in the Swedish ones. However, the discussion has petered out, mostly due to the teacher union’s loud protests against a literary canon. At the same time, Brink (2006) mentions that a literary canon can provide students with cultural knowledge, and many indicate that it is for everyone, as well as being timeless and universal (p. 28). This means

12

that with the use of a literary canon, the education can be equal for all students, and provide them with knowledge of their cultural history.

13

3. Method

In the following chapter, we will describe and explain the procedure of our research.

3.1 Choice of Methods

For this research, we chose to use both a quantitative and a qualitative method. We chose the quantitative method since it enables for a larger amount of answers, which in turn facilitates the possibility of generalizing the results. At the same time, the choice of the qualitative method is based on our desire to acquire more in-depth insight to teachers’ choices. The combination of two methods is beneficial when one wants to target a specific issue and thereby comprehend it better (Dörnyei, 2007, p. 164).

To investigate which literature is used in the English classrooms in Sweden, we chose to send our survey to teachers all over Sweden in order to receive a large number of replies, and for this type of survey, approximately 100 answers is enough. This was done by linking to the survey on different social media platforms for teachers, but we also sent it by email to our supervisors from our teacher practice and our former teachers from when we attended upper secondary school. Moreover, we felt that when constructing questions for a survey, it was important to have simple and clear questions, so that the participants could easily understand our intention. Furthermore, we chose to only include six questions, to increase the number of replies. In other words, if we would have had many and long questions, less would have been inclined to participate. We also made sure that we minimized the amount of open-ended questions, because they would make it more difficult to juxtapose the data. All of the above is in accordance with Bryman (2001) who states that surveys should be short and easy to comprehend (p. 150). Bell (2005) also argues that surveys are used when the researchers want to obtain answers to the same questions from a substantial number of teachers, and surveys also allow for a more clear comparison of the results (p. 14). An issue with using surveys is, however, that we could not ask follow-up questions. This meant that, even though we had some interesting results, some of them were unclear and therefore we could not clarify them, and thus they could not be used at all.

In addition to the survey, we chose to interview a handful of teachers to complement the answers from the survey. Hatch (2002) argues that conducting interviews is a way to further

14

explore participants perspectives and to understand their point of views (p. 91). By conducting the research this way, the interviews provided us with the possibility of further insight to why the teachers chose their specific literature. Moreover, we chose to conduct standardized interviews, meaning that we had predetermined open-ended questions which we asked all of our participants in the same order (Hatch, 2002, p. 95). This allowed us to compare the gathered data more easily (p. 95). In contrast to the survey, the interviews also allowed us to ask follow-up questions for clarification whenever it was needed, which allowed for a deeper understanding of the answers and the teachers’ views. At the same time, if the teachers would have felt insecure during the interviews, their answer might not have been their initial thought on the question. However, our interview questions were uncomplicated and simple to answer, and they did not initiate criticism against the teachers. If our questions would have been different, the teachers might not have felt comfortable to be honest, and thus we would not have had such informative results (Bell, 2005, p. 159).

3.2 Participants

We had 101 participants partaking in our quantitative study, and we had five teachers for our interviews. The participants in the survey were upper secondary school teachers who teach English. They were primarily chosen because of their interest in partaking in an interview, but they also fulfilled our requirement for the interviewees; that they would be teaching at least one of the three English courses at upper secondary level. Since we only had five teachers who showed an interest in partaking in the interviews, we did not have to turn any of them down. When the teachers partook in the survey, we had already written in it that if they were interested in participating in an interview, they could send an email to one of us, and this is what three of the teachers did. The other two showed an interest in participating when we visited one of the schools.

All of our interviewees had different experiences within the field, and instead of using fictional names, we have been referring to the teachers as teacher 1 to teacher 5, and then abbreviated them to T1 et cetera. Teacher 1 has been teaching at upper secondary level for 13 years, mainly in the courses English 5 and 7. Teacher 2 has been an active teacher in the field for four years, and previously she has been teaching English 6 and 7, but currently she only teaches English 5. Teacher 3 has been teaching for 15 years and she is currently teaching

15

all of the three English courses. Teacher 4 has been a teacher in the field for 14 years, and she is teaching English 7. Lastly, teacher 5 has been teaching for nine years, and this year he is teaching English 7, otherwise he teaches all of the three courses.

3.3 Contexts and Procedures

Our interest concerned investigating which literature is being used by English teachers in Sweden, and therefore, we wanted replies to the survey from all over Sweden. We received replies from the majority of the counties in Sweden, that is, 20 out of 21. However, the interviews were conducted in various schools in the south of Sweden.

For the qualitative method, we chose standardized interviews. Because of the choice of standardized interviews, we both recorded the interviews and subsequently transcribed all five of them, which Hatch (2002) advocates. Moreover, we chose not to take notes during the interviews to decrease the risk of disturbing and distracting the interviewees while they answered our questions. Not taking notes meant that we could focus on listening carefully, and the interviewees could feel that we were thoroughly focused on what they said (Dörnyei, 2007; Kvale, 2007). Furthermore, to avoid any outer disturbance, the interviews were conducted in the participants’ school in a quiet room where only we and the participant were present.

As mentioned, the interviews were transcribed, but we also subsequently picked out the quotes that felt valuable to our research questions. Later, we made a table of what the curriculum, previous research, theory, and what our result showed about the different areas. By doing it this way, we could easily see how and why the results did or did not correlate. As supported by Kvale (2007), categorizing the interview, or the transcription, can provide an overview which can more easily facilitate a comparison (p. 105). This process took approximately two and a half hours.

The survey was open for almost seven weeks, and we compared all the answers after closing the survey. We did this by going through answer by answer and listed them in a Word document to produce a list of the most frequent literature used in Swedish schools. This process took about three hours. Subsequently, we put the titles in order according to popularity, and we then calculated the percentage of how frequently they were mentioned. This process took about two hours.

16

3.4 Instruments

For the quantitative study, we used Google Forms and included six direct questions. We chose Google Forms due to its simplicity regarding the questionnaire, and also because it is user friendly. Moreover, Google Forms is frequently used which means that many of the participants are familiar with it, and we therefore believed that more participants would be inclined to partake. Our questions were deliberately straightforward in order to receive straightforward answers, which would then be more easily converted into statistics (Bell, 2005, p. 137). We had a total of six questions, where four of them where main questions. In order to answer our research question, questions three to five in the survey concerned which literature the teachers use in the different courses. Question six concerned if the teachers use complete works, and this was to answer one of our sub-questions. This question has its base in our interest of discovering how the teachers are working with the literature, that is, if they are using the complete book or only excerpts from it. If the teachers answered no to this question, we included a sub-question in order for the teacher to elaborate their answer. Moreover, when we designed the survey we had Bryman (2001) in mind, since he advocates for a short and organized survey. We did not test our questions beforehand or based them on another survey, however, in accordance with Bell (2005), we did consult with our supervisor (p. 136).

For the qualitative study, we chose open ended questions to allow for the interviewee to further elaborate their viewpoints (Hatch, 2002). Since our purpose was to receive insight from teachers who participated in the survey, we chose to use the same questions for the survey as for the interviews. However, we did include more in-depth questions, as can be seen in appendix 2. This was to receive a deeper understanding of the participating teachers’ choices. Interviews also allowed us to ask follow-up questions if anything needed further explanation (ibid.). As mentioned before, we did not test our interview questions or based them on another survey, but we did consult with our supervisor beforehand (Bell, 2005, p. 136).

17

3.5 Ethical Considerations

There are ethical considerations one must take into account when conducting a study according to Vetenskapsrådet (2017). We informed our participants about the research area beforehand, both in the survey and before the interviews occurred. Information was also given about the anonymity, and that the participants could end the interview whenever he/she pleased. Also, the participants were informed that they were allowed to pass a question if they desired to do so. In addition, all personal details about the participants and the schools are confidential, and therefore the names and genders in this degree project are fictive. Also, the teachers who partook in the survey were anonymous, and no question was obligatory to answer (ibid.).

Furthermore, according to Vetenskapsrådet (2017) there are four specific demands to be met when conducting research, and we have taken all of them into account. The first demand pertains to that the interviewee is informed about the purpose of the research, as well as knowing that participation is optional, and that they can cancel whenever they want to. The second demand concerns consent from the interviewee, which we received from all participants. The third demand pertains to confidentiality. In order to keep the participants anonymous, we have only used fictional names and gender when we have referred to our participants. Additionally, any information about the interviewee and their schools is confidential and will be kept away from people who are unauthorized. Lastly, in order to follow the fourth demand, our data will only be used for this specific research and will be kept from commercial and other non-scientific objectives.

18

4. Results

In the following chapter, we will present our results. For a clearer overview, we have divided the results into two categories: survey and interviews. Our purpose with this research was to investigate which literature is used in upper secondary English classrooms, as well as why and how they are using their literature.

4.1 Survey

When asked how the teachers use their literature, the vast majority of the teachers answered that they let their students read the entire book in their courses, but there were some who did not use novels at all. 5% of the teachers answered that they solely use textbooks in their courses. The two main reasons for not letting their students read the whole book are because of difficulties finding suitable literature, and because the teachers feel that the students are not interested in reading books or not motivated enough to read.

One of the questions in the survey was whether the teachers always let their students read the whole book. 71.7% of the participants answered yes, and 28.3% answered no, as can be seen in the diagram below. The teachers that answered no, elaborated their answers and said that they used extracts from books along with films instead of reading the whole book.

19

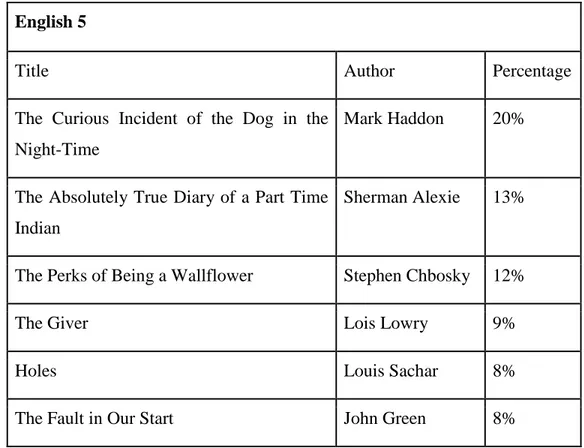

In terms of which books are being used in the Swedish schools, we put together one list for each of the English courses in upper secondary, which can be found in the appendix section. However, the six most popular titles for each course are presented in the tables below.

Table 1. The Most Commonly Assigned Books in English 5 (first year of upper secondary school English).

English 5

Title Author Percentage

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time

Mark Haddon 20%

The Absolutely True Diary of a Part Time Indian

Sherman Alexie 13%

The Perks of Being a Wallflower Stephen Chbosky 12%

The Giver Lois Lowry 9%

Holes Louis Sachar 8%

20

Table 2. The Most Commonly Assigned Books in English 6 (second year of upper secondary school English).

Table 3. The Most Commonly Assigned Books in English 7 (last year of upper secondary school English).

English 6

Title Author Percentage

Animal Farm George Orwell 14%

To Kill a Mockingbird Harper Lee 14%

1984 George Orwell 12%

Of Mice and Men John Steinbeck 9%

Frankenstein Mary Shelley 6%

The Great Gatsby F. Scott Fitzgerald 6%

English 7

Title Author Percentage

1984 George Orwell 15%

The Great Gatsby F. Scott Fitzgerald 10%

Lord of the Flies William Golding 8%

Animal Farm George Orwell 6%

To Kill a Mockingbird Harper Lee 6%

21

4.2 Interviews

All of our interviewed teachers pointed out that they have had difficulties finding appropriate literature for their students. There are multiple reasons to why, for example, one teacher mentioned that she had not read much young adult and contemporary literature and that is why she stated that she found it difficult to find books that will be interesting for the students and which will suit their age: “Yes I have had difficulties, because I have not read a lot of young adult literature.” (Teacher 2, T2). Another teacher stated that the difficulties pertained to budget related reasons, and often times she felt restrained and had to choose a book that already existed in enough copies for the whole class. Furthermore, a third teacher stated that she had difficulties finding books that deviated from the norm, whereas teacher one (T1) claimed other reasons: “Absolutely! It is at times, especially in English 5. I have not felt resistance to using short stories with them, but I have felt resistance for using novels when I know that there are some weaker students in the group”.

The teachers were also asked what their reasons for choosing their specific literature was, and the answers were either topic related reasons, or that the book had a suiting proficiency level. Three out of the five teachers look for books with suitable topics or themes: “There should be a good theme that is easy to apply, that goes well with adolescence” (Teacher three, T3). By ‘theme that is easy to apply’ she means themes that fit the subject or topic which they have been working with in previous lessons. Furthermore, four out of five mentioned that they chose literature depending on the language level of the book and if it suits their students’ proficiency level. Additionally, three out of five valued interesting and suspenseful books, along with engaging characters, as teacher five (T5) stated: “It depends. Sometimes the language is crucial, sometimes it is the storyline and the characters. Authors and background can also be crucial, but the most crucial factor is that it suits the group of students.”.

All of the teachers stated that they always let their students read entire books. Teacher four (T4), for instance, stated: “It is very important for me that the students read a complete novel, at least one per course, preferably two.” However, three of the teachers said they also use short stories, for example, as T1 said: “When reading literature, we read the whole book, but I usually include short stories in all of the courses I teach.”, and T2 said that they will use short stories in the future.

22

The teachers were also asked what their thoughts on an official canon were. Four out of five took a negative stand towards an official canon. T1 said they would feel controlled: “I think I would have felt very controlled, [...] not being able to choose based on what we are working with right now [...] I would rather have it as it is now.” In alignment to T1, T3 said they would feel restrained, and also that it would be boring with an official canon:

We haven’t tested it. It would have been comfortable if someone else had decided that ‘these work on this level, and these are the ones you are supposed to read, no discussion’. But also, quite restrictive. So, I don’t really know, I don’t think it would be good in the long run, and the risk is, of course, that it will be decided by higher authorities who do not have contact with reality and who say, ‘now you are supposed to read Pride and Prejudice and Crusoe’, so it becomes too boring or too much.

T4 also mentioned that it would be boring, and that it would, at the same time, restrain them from being creative. Lastly, T5 also said he would feel restrained and restricted: “It might seem like a good idea, but I am against it because it restricts and controls too much. I think that we as teachers have a lot of freedom, and that we should defend it so that it is not taken from us. The freedom to choose and adapt is a big part of what I like about being a teacher.” However, T2 had a positive view on an official canon, and claimed that it would contribute to the students’ common knowledge: “In a good way, because it becomes a part of the common knowledge, the common education, it could be good to collect it all a little bit”.

When asked about an unofficial canon, three out of five had a strongly positive view, and said it would be useful and give them inspiration: “Yes I would use it for inspiration of course.” (T2), “Yes I think we would have used that one, absolutely. It would have been useful for us English teachers here” (T1). T4 would personally not use such a canon, but is open for the idea, as long as it would be a list recommended by the Swedish Council for Education (Skolverket): “One receives an inkling of what the Swedish Council of Education regards as significant literature, and it would also increase the equality if all teachers would have complied to it”. Lastly, T5 would most definitely not use an unofficial canon.

23

5. Discussion

Our results confirm Langer’s observation that it is hard to find literature for English teachers in education (1995, p. 143). All of the teachers we interviewed experienced difficulties finding suitable literature for their students. Even though their difficulties are based on various reasons, the conclusion is that the difficulty for finding suitable literature is evident. One of the reasons for why T5 had difficulties finding literature is because he wants to find books that he considers to be outside the norm. This could also be the reason to why he does not want an official canon. In all likelihood, he would then feel restrained, and as Maley (2001) argues, an official canon very often contains literature within the norm. Also, as Papadima (2009) states, using literature in educational settings that contain characters from different cultures and with different backgrounds is important in order for students to gain a wider perspective on life (p. 120-121). In contrast to T5, T2 has not read much books aimed for young adults, which could be a reason why she was positive to both an official and an unofficial canon. This shows that, teachers who have read extensively, are more inclined to trust their own competence and therefore do not have the same need for a canon. However, as we noted from our results, teachers who have not read much are more likely to feel the need of having a canon. This is not to state that everyone who has not read a lot sees the need for an official canon, but they might be more inclined to see the benefits of one.

At the same time, even if one has read quite eminently, there can still be a need for inspiration as we can see with T1 and T3. They stated that their difficulties with finding suitable literature stem from a struggle with finding relevant books with relevant themes and an apt language level. Both said they would use an unofficial canon, because it is easier finding relevant books from a list of books used by teachers in the field, instead of trying to find titles without help.

As we can see, there is a connection between why the teachers choose their specific literature and finding suitable literature. The teachers want to use books that are engaging, motivates the students to read, are suitable for students’ proficiency level, and which are connected to themes and/or ongoing projects. In other words, they do not want to use books just because they must. This is a strong reason why they use their chosen literature, and it is also in accordance with, for example, Lundahl (2012) and Bradford (2006), who both states

24

the importance of using literature for, for example, improving the students’ language proficiency. Moreover, the teachers want their literature to be engaging for the students, and they want it to motivate them to read. Furthermore, they also seek literature that will suit the students’ proficiency level, as well as being connected to themes and ongoing projects. The teachers want to find exceptional literature that will develop students’ proficiency level, but since they also want to include all of the aforementioned qualities, it becomes difficult to find suitable literature. Therefore, a list like ours can give the teachers the possibility to include all of these qualities in the literature they use.

All of the teachers are using the complete book in their teaching, which also shows why literature is vital in educational settings (Papadima, 2009; Langer, 1995; Molloy, 2003; Lundahl, 2012). For example, T4 clearly states how valuable literature is for her and that she preferably would like to use at least two books per course. This is in alignment with Rings (2002) who advocates for extensive reading because of its positive effects on language proficiency. Furthermore, as Economou (2015) stated, reading novels for language development is vital due to the gaining of personal development, cognitive development, and language development (p. 114-115). This is an interesting aspect to look at, since it conforms to our results and previous research (Economou, 2015; Lundahl, 2012; Langer, 1995); the trend shows that teachers see the significance of using complete books in their teaching. At the same time, many of the teachers also stated that they do use short stories at times, but then to complement the topic or theme from the book that they are already reading. To conclude, all of our interviewees and the majority of the teachers who took part in the survey are using whole books, however some are also using short stories.

As we have seen from our interviews, there are conflicting views concerning an official canon. Previous research has shown a division between teachers in terms of having an official canon, and our results show the same. However, even though there exist conflicting opinions, the majority took a negative stand towards an official canon. Maley (2001) stated, that a canon can be hindering for teachers, and many of our interviewees stated a similar reason. Those who were positively inclined towards an official canon, stated that it would give the students a more equal education, as Brink (2006) also claimed.

An unofficial canon can improve the English education in diverse ways. Firstly, a list as inspiration can minimize the difficulties of finding literature, which we have seen is

25

frequently occurring for teachers in the field, and this is also in accordance with Langer (1995) who also argues that these difficulties exist. Having a list can make it easier when choosing literature, since one does not have to search for titles oneself. In other words, the teacher will not have to set time aside to find new titles since a list is provided that one can look through. Moreover, the International Literacy Association has a similar viewpoint and their list is similarly compiled as ours; it contains the titles of books used by teachers. Furthermore, our results point to teachers’ desire to have a similar list as the ILA’s. Secondly, the list enables for a greater variety in the literature education. This is because teachers are able to find titles in the list that they would not have come across otherwise, and thus teachers who are looking for new books can more easily diverge from titles which they frequently have used. Finally, our list rests on information by teachers in the field, and thus ensures that the titles are suitable for the different English courses. Because of this, teachers do not have to worry if the literature will work in their classes, since they are already being used, and have been tested, by diligent experts, that is, active teachers in the field. As our interviewees have claimed, they did not want to have a list conducted by higher authorities, but instead a list to use for inspiration which include titles teachers have submitted themselves.

Our intention was never to argue for or against an official canon, but also not to constitute an unofficial one. Since we have seen a need, our purpose was to help teachers in the field with inspiration so that it will be easier for them to choose from a significant variety of suitable literature. As what we have seen from our interviews, the majority of the teachers would use even an unofficial canon, and therefore we believe that they would also use our list of suggestions.

We have noticed that some books are used throughout all of the three English courses. For example, Catcher in the Rye is one of them, as can be seen in appendix 1. There could be many reasons for why a certain book is used in the same courses, but we have seen a pattern of teachers looking for specific qualities in their books. So, depending on the proficiency level of their specific students, one book could work in all of the different courses. For example, one strong English 5 group could read the same book as a weak English 6 or 7. However, rarely the same teacher used the same book in all of his/her courses. From the survey, we only had approximately three teachers who used the same book in two of their

26

courses. The reason for this could be either the proficiency level of the students or the theme that they were working with.

27

6. Conclusion

Based on our results, we can draw three different conclusions. Firstly, previous research shows the significance of using literature in schools, and our results showed that 100% of the teachers in the field use some sort of literature in their education. However, many teachers are having problems finding suitable literature for their different courses, and they see the need for having a list of suggested books as inspiration. Therefore, we are convinced that our list will be used (see appendix 1-3 for the complete list). Secondly, the teachers had differing reasons for why they chose their specific literature; some of them being relevant topics and themes; language level; suspenseful books; and/or engaging characters. Moreover, 71,7% said they always use entire books in their classes, instead of merely using extracts. Lastly, the clear majority of our interviewees took a negative stand towards having an official canon, however they were open for using an unofficial as inspiration. Due to all the above conclusions, we feel that our research will contribute to aiding upper secondary English teachers with finding suitable literature.

6.1 Limitations and Future Research

In order to constitute an unofficial canon, one would need a significant amount of samples from a survey. However, ours was not substantial enough, and therefore we call our results a list. This was, therefore, a limitation in our study. For future research, we would suggest for this survey to be done with a bigger sample in order to create a more valid unofficial canon to further ease the workload for the teachers.

28

References

Bell, J. (2005). Doing your research project - a guide for first-time researchers in education,

health and social science. [4th ed]. UK: Bell & Bail Ltd.

Brink, L. (2006). Kanon, karaktärsfostran, kulturarv? Om litteraturundervisningens textkärna. In Brink, L & Nilsson, R., Kanon och Tradition - Ämnesdidaktiska studier

om fysik-, historie-, och litteraturundervisning (13-44). Gävle: Intellecta Docusys

AB.

Bryman, A. (2001). Samhällsvetenskapliga metoder (1st ed.). Malmö: Liber AB.

Carroli, P. (2008). Literature in second language education: enhancing the role of texts in

learning. London: Continuum.

Danska Lärarföreningen. (2015). Kanonarbejde. Retrieved from: https://dansklf.dk/kanonarbejde.

Dörnyei, Z. (2007). Research methods in applied linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Economou, C. (2015). Reading Fiction in a Second Language Classroom. Education Inquiry, 6(1), 99-118.

Hatch, A, J. (2002) Doing qualitative research in education settings. Albany: State University of New York Press.

International Literacy Association (2018). Teachers’ Choices 2018 Reading List. Retrieved from: https://www.literacyworldwide.org/docs/default-source/reading-lists/teachers-choices/teachers-choices-reading-list-2018.pdf?sfvrsn=3c89a48e_4.

Kvale, S. (2011). Doing interviews. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publication.

Langer, J., A. (1995). Litterära föreställningsvärldar. Litteraturundervisning och litterär

förståelse. Göteborg: Bokförlaget Daidalos.

Lundahl, B. (2012). Engelsk språkdidaktik: texter, kommunikation, språkutveckling. Lund: Studentlitteratur AB.

Maley, A. (2001). Literature in the Language Classroom. In Carter, R. & Nunan, D., The

Cambridge Guide to Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (180-185).

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

29

Osbeck, C (2016). Skönlitteratur i klassrumsarbetet bidrar till etisk kompetens. Skolverket.

Retrieved 28th of March, 2018 from:

https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/forskning/amnen-omraden/so- amnen/religionskunskap/undervisning/skonlitteratur-i-klassrumsarbetet-bidrar-till-etisk-kompetens-1.249670.

Papadima-Sophocleous, S. (2009). Can Teenagers be Motivated to Read Literature?. Reading

Matrix: An International Online Journal. 9(2), 118–131.

Persson, M. (2007). Varför läsa litteratur? Lund: Studentlitteratur AB.

PIRLS. (2006). PIRLS 2006 International Report: IEA’s Progress in International Reading

Literacy Study in Primary Schools in 40 Countries. Boston: Lynch School of

Education.

Rings, L. (2002). Novice-Level Books for Reading Pleasure in the Second Language Classroom. Die Unterrichtspraxis / Teaching German, 35(2), 166–173.

Skolverket. (2011). Läroplan, examensmål och gymnasiegemensamma ämnen för

30

Appendix 1: The Complete List

English 5

Title

Author

Percentage

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time

Mark Haddon 20%

The Absolute True Diary of a Part Time Indian

Sherman Alexie 13%

The Perks of Being a Wallflower Stephen Chbosky 12%

The Giver Lois Lowry 9%

Holes Louis Sachar 8%

The Fault in Our Stars John Green 8%

Animal Farm George Orwell 6%

Stone Cold Robert Swindells 6%

Big Mouth and Ugly Girl Joyce Carol Oates 5%

Go Ask Alice Beatrice Sparks 5%

Hanging on to Max Margaret Bechard 4%

The Hunger Games Suzanne Collins 4%

The Outsiders S. E. Hinton 4%

The Wave Todd Strasser 4%

Unarranged Marriage Bali Rai 4%

Boy Roald Dahl 3%

Catcher in the Rye J. D. Salinger 3%

31

The Boy in the Striped Pajamas John Boyne 3%

About a Boy Nick Hornby 2%

Across the Barricades Joan Lingard 2%

Dead Ends Erin Jade Lange 2%

Simon vs. the Homo Sapiens Agenda Becky Albertalli 2%

The Perfect Match Jodi Picoult 2%

The Way of the Warrior Dan Millman 2%

Sarah Key Tatiana de Rosnay 1%

So Yesterday Scott Westerfeld 1%

Speak Laurie Halse Anderson 1%

Matilda Roald Dahl 1%

Does My Head Look Big in This Randa Abdel-Fattah 1%

All American Boys Brendan Kiely and Jason

Reynolds

1%

Paper Towns John Green 1%

Heart shaped Bruise Tanya Byrne 1%

Slam Book Ann M. Martin 1%

The Woman in Black Susan Hill 1%

I’m the King of the Castle Susan Hill 1%

Going Solo Eric Klinenberg 1%

The Phantom of the Opera Gaston Leroux 1%

32

Goodnight Mr. Tom Michelle Magorian 1%

Baby Talk Sally Ward 1%

The Breadwinner Deborah Ellis 1%

Text Game Kate Cann 1%

Revenge Lisa Jackson 1%

The Babysitter R. L. Stine 1%

The Hitchhiker Charlie Lee 1%

To Kill a Mockingbird Harper Lee 1%

Garden ? 1%

I am the Messenger Markus Zusak 1%

Bridge to Terabithia Katherine Paterson 1%

The Gun C. J. Chivers 1%

Everything Everything Nicola Yoon 1%

Thank You, Ma’am Langston Hughes 1%

The Chocolate War Robert Cormier 1%

Alice in Wonderland Lewis Carroll 1%

Maze Runner James Dashner 1%

Harry Potter J. K. Rowling 1%

Bridget Jones's Diary Helen Fielding 1%

Aug Jury of Her Peers Susan Glaspell 1%

33

Before I Die Jenny Downham 1%

I Never Promised You Rose Joanne Greenberg 1%

Me Before You Jojo Moyes 1%

A Thousand Splendid Suns Khaled Hosseini 1%

Abomination Robert Swindells 1%

Broken Soup Jenny Valentine 1%

Pictures of Hollis Woods Patricia Reilly Giff 1%

Thirteen Reasons Why Jay Asher 1%

Pale Chris Wooding 1%

Parvana’s Journey Deborah Ellis 1%

The Stormbreaker Anthony Horowitz 1%

Sh*t My Dad Says Justin Halpern 1%

We Were Liars E. Lockhart 1%

I am Legend Richard Matheson 1%

Of Mice and Men John Steinbeck 1%

Tomorrow When the War Began John Marsden 1%

Shatter Me Tahereh Mafi 1%

Delirium Lauren Oliver 1%

Divergent Veronica Roth 1%

Wonder R.J. Palacio 1%

The Fun they Had Isaac Asimov 1%

34

Legend Mary Lou 1%

I am Malala Christina Lamb and Malala

Yousafzai

1%

The Child Called It Dave Pelzer 1%

Tuesdays with Morrie Mitch Albom 1%

Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children

Ransom Riggs 1%

The No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency Alexander McCall Smith 1%

1984 George Orwell 1%

The Great Gatsby F. Scott Fitzgerald 1%

35

English 6

Title

Author

Percentage

Animal Farm George Orwell 14%

To Kill a Mockingbird Harper Lee 14%

1984 George Orwell 12%

Of Mice and Men John Steinbeck 9%

Frankenstein Mary Shelley 6%

The Great Gatsby F. Scott Fitzgerald 6%

I am the Messenger Markus Zusak 4%

The Catcher in the Rye J. D. Salinger 4%

The Help Kathryn Stockett 4%

And Then There Were None Agatha Christie 3%

Big Mouth and Ugly Girl Joyce Carol Oates 3%

Lord of the Flies William Golding 3%

Pride and Prejudice Jane Austen 3%

The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind Bryan Mealer and William Kamkwamba

3%

Things Fall Apart Chinua Achebe 3%

Unarranged Marriage Bali Rai 3%

Unwind Neal Shusterman 3%

Across the Barricades Joan Lingard 2%

36

Brave New World Aldous Huxley 2%

Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury 2%

Great Expectations Charles Dickens 2%

Harrison Bergeron Kurt Vonnegut 2%

Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children

Ransom Riggs 2%

Purple Hibiscus Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie 2%

[Title not mentioned] Shakespeare 2%

Slaughterhouse Five Kurt Vonnegut 2%

The Absolute True Diary of a Part Time Indian

Sherman Alexie 2%

The Five People You Meet in Heaven Mitch Albom 2%

The Hobbit J.R.R. Tolkien 2%

The Hunger Games Suzanne Collins 2%

The Perks of Being a Wallflower Stephen Chbosky 2%

The Pearl John Steinbeck 2%

Thirteen reasons Why Jay Asher 2%

Tuesdays With Morrie Mitch Albom 2%

Sleeping Beauty The Brothers Grim 1%

[Title not mentioned] Jane Austen 1%

Regret Kate Chopin 1%

Mudbound Hillary Jordan 1%

37

The Grass is Singing Doris Lessing 1%

Code name Verity Elizabeth E. Wein 1%

Goodnight Mister Tom Michelle Magorian 1%

Wuthering Heights Emily Brontë 1%

Interpreter by Maladies Jhumpa Lahiri 1%

Much Ado About Nothing William Shakespeare 1%

Boy Kills Man Matt Whyman 1%

Vernon God Little DBC Pierre 1%

Every Day David Levithan 1%

Oliver Twist Charles Dickens 1%

Before I Die Jenny Downham 1%

Boy 21 Matthew Quick 1%

Back Roads Tawni O'Dell 1%

The Kite Runner Khaled Hosseini 1%

I, Robot Isaac Asimov 1%

Making a Fire Jack London 1%

Knots and Crosses Ian Rankin 1%

[Title not mentioned] John Green 1%

Hamlet Shakespeare 1%

Huckleberry Finn Mark Twain 1%

Jane Eyre Charlotte Brontë 1%

The Lifeboat Charlotte Rogan 1%

38

Dracula Bram Stoker 1%

Misery Stephen King 1%

About a Boy Nick Hornby 1%

The Fault in Our Stars John Green 1%

Divergent Veronica Roth 1%

Tom Sawyer Mark Twain 1%

Slumdog Millionaire Vikas Swarup 1%

The Ocean at the End of the Lane Neil Gaiman 1%

The Lovely Bones Alice Sebold 1%

Ruby Red Kerstin Gier 1%

Cal Bernard MacLaverty 1%

The Book Thief Markus Zusak 1%

A Family Supper Kazuo Ishiguro 1%

Romeo and Juliet Shakespeare 1%

The Rosie Project Graeme Simsion 1%

The God of Small Things Arundhati Roy 1%

The Bluest Eye Toni Morrison 1%

The Outsiders S. E. Hinton 1%

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy Douglas Adams 1%

Hold Tight Harlan Coben 1%

Flowers for Algernon Daniel Keyes 1%

Rape - A Love Story Joyce Carol Oates 1%

39

The Color Purple Alice Walker 1%

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time

Mark Haddon 1%

A Street Cat Named Bob James Bowen 1%

The Other Hand Chris Cleave 1%

The Collector John Fowles 1%

Oryx and Crake Margaret Atwood 1%

The Selfish Giant Oscar Wilde 1%

I am Malala Christina Lamb and Malala

Yousafzai

40

English 7

Title

Author

Percentage

1984 George Orwell 15%

The Great Gatsby F. Scott Fitzgerald 10%

Lord of the Flies William Golding 8%

Animal Farm George Orwell 6%

To Kill a Mockingbird Harper Lee 6%

Brave New World Aldous Huxley 5%

The God of Small Things Arundhati Roy 5%

A Handmaid’s Tale Margaret Atwood 4%

Disgrace J.M. Coetzee 4%

Dracula Bram Stokers 4%

Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde Robert Lewis Stevenson 4%

Jane Eyre Charlotte Brontë 4%

Never Let Me Go Kazuo Ishiguro 4%

The Book of Joe Jonathan Tropper 4%

The Fifth Child Doris Lessing 4%

[Title not mentioned] Shakespeare 4%

Americanah Cimamanda Ngozi Adchie 3%

Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury 3%

Frankenstein Mary Shelley 3%

Heart of Darkness Joseph Conrad 3%

Homegoing Yaa Gyasi 3%

41

Slaughterhouse Five Kurt Vonnegut 3%

The Catcher in the Rye J.D. Salinger 3%

The Picture of Dorian Gray Oscar Wilde 3%

White Tiger Aravind Adiga 3%

Night Elie Wiesel 2%

The Crucible Arthur Miller 2%

Farewell to Arms Ernest Hemingway 2%

The Road Cormac McCarthy 2%

The Grass is Singing Doris Lessing 2%

The Sense of an Ending Julian Barnes 2%

In Cold Blood Truman Capote 2%

White Teeth Zadie Smith 2%

The Cider House Rules John Irving 2%

Of Mice and Men John Steinbeck 2%

The Help Kathryn Stockett 2%

Treasure Island Robert Louis Stevenson 2%

Gulliver’s Travels Jonathan Swift 2%

Brick Lane Monica Ali 2%

If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler Italo Calvino 2%

The Impressionist Hari Kunzru 2%

Winter’s Bone Daniel Wodrell 2%

Being There Jerzy Kosiñski 2%

The Importance of Being Earnest Oscar Wilde 2%

Purple Hibiscus Cimamanda Ngozi Adchie 2%

A Curious Incident of a Dog in the Nighttime

42

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland Lewis Carroll 2%

Wishing Game Patrick Redmond 2%

The Reluctant Fundamentalist Mohsin Hamid 2%

Acid Row Minette Walters 2%

Hamlet Shakespeare 2%

Rich Dad Poor Dad Robert Kiyosaki & Sharon Lechter

2%

Marching Powder Rusty Young 2%

A Haunted House Charles Dickens 2%

Harrison Bergeron Kurt Vonnegut 2%

Dr. Fischer Graham Greene 2%

Pygmalion George Bernard Shaw 2%

Beloved Toni Morrison 2%

Jellicoe Road Melina Marchetta 2%

We are Completely Beside Ourselves Karen Joy Fowler 2%

To the lighthouse Virginia Woolf 2%

Unarranged Marriage Bali Rai 2%

Guppies for Tea Marika Cobbold Hjörne 2%

The Bluest Eye Toni Morrison 2%

Have a Yellow Sun Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie 2%

Death of a Salesman Arthur Miller 2%

Being There Jerzy Kosiñski 2%

Angela’s Ashes Frank McCourt 2%

The Hotel of the Corner of Bitter and Sweet

Jamie Ford 2%

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest Ken Kesey 2%

43

The Book Thief Markus Zusak 2%

Wide Sargasso Sea Jean Rhys 2%

Interpreter of Maladias Jhumpa Lahiri 2%

The Stepford Wives Ira Levin 2%

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Philip K. Dick 2%

Fingersmith Sarah Waters 2%

44

Appendix 2: Survey Questions

1. Vilket län är du verksam i som lärare? 2. Hur länge har du varit verksam som lärare?

3. Vilken litteratur använder du i engelska 5? Nämn de tre vanligaste 4. Vilken litteratur använder du i engelska 6? Nämn de tre vanligaste 5. Vilken litteratur använder du i engelska 7? Nämn de tre vanligaste 6. Låter du eleverna alltid läsa hela romanen?

45

Appendix 3: Interview Questions

1. Hur länge har du varit verksam som lärare? 2. Vilka engelskkurser undervisar du i?

3. Vilken litteratur använder du i engelska 5, 6, och 7? Nämn de tre vanligaste för varje kurs

4. Varför väljer du just den litteraturen? 5. Låter du eleverna alltid läsa hela romanen?

6. Om inte, hur gör du då? Tex använder delar av en roman, film etc 7. Vilka kvalitéer letar du efter i romaner?

8. Hur lägger du upp litteraturläsningen i dina klasser?

9. Vilka är dina bästa knep för att få litteraturläsningen intressant? 10. Svårigheter som uppkommer av att använda hela romaner? 11. Har du haft svårigheter med att välja litteratur? På vilket sätt? 12. Vad anser du om en officiell kanon?

13. Skulle det vara en begränsning att ha en officiell kanon? Vad skulle det innebära för dig?