Degree projects improving co-operation

between the teacher education program

and schools

- Swedish experiences

Paper presented at the ATEE conference, 31st Annual ATEE Conference

Ljubljana – Portoroz, Slovenia, 21st – 25th October 2006

Inger von Schantz Lundgren & Mats Lundgren (ivo@du.se, mlu@du.se)

HögskolanDalarna (Dalarna University College) Sweden

Co-operation through degree projects

The demands made on teachers and on teacher education grow continually. There are great expectations. One of many possible ways to meet these expectations is by developing co-operation between the teacher education program and schools. In the program in which we are involved1, close co-operation with partner schools2 has been established during the last few years. The student’s degree project is an example of how to make this co-operation work on a concrete level. A degree project reflects different kinds of problems and may contribute to better teaching in the individual school, but also to offering relevant educational subject matter to the students, which may be adapted as an element in the university’s research envi-ronments. (Figure 1) The concept is meant to create a “winner, winner situation”.

School development The degree project The teacher education program

Figure 1. The degree project co-operation created between the teacher education program and partner schools

We use a small case study3 from teacher education programs in five Swedish universities and our own experiences as teacher educators in order to elaborate on the following questions:

- What purpose does a degree project have and what role does it play in teacher

edu-cation?

- What criteria are relevant to assessing a degree project, what qualities do such

crite-ria have and is it possible to assess a degree project fairly?

- How is it possible to use degree projects to improve co-operation between the teacher

education program and schools and thereby contribute to school development?

We do not think it is possible from this limited material to draw general conclusions, but we hope to raise some questions of future interest in this field.

Student teachers’ degree projects

On the official level

The degree project’s main purpose is to prepare students for a future career as a teacher and, as an alternative, for going on to be a candidate for a doctor’s degree The degree project is an im-portant part of the teacher education program. It is also an integral part in the development of critical and scholarly thinking, deepening pedagogical and didactic knowledge and giving the students an opportunity to apply research methods and also as an element that gives the

1 The teacher students in our teacher education program will work on different levels in the Swedish school

sys-tem: with children in pre-school, with pupils in compulsory school (in a 3.5-year program) and in the upper sec-ondary school (in 4.5-year program).

2

A partner school is a school that takes responsibility for the student teachers’ education in “practical work”. The school-based teacher is responsible for this part of the education, in co-operation with educators from the teacher education program.

3

The case study is made by a working-team within a co-operation project named Pentaplus that encompasses five Swedish universities and university collages in central Sweden.

dents an opportunity to show that they have reached central goals in their teacher education. This is also what is stated in official documents:

The degree project constitutes an important step towards developing a scholarly way of thinking and it is intended to enable the students to deepen their knowledge. The teacher education program should give the student knowledge of and insights into different re-search methods and rere-search ethics. The degree project contributes to making the student apply research methods and, with that, becomes a preparation for eventual research-level studies.

Also to those students who do not intend to go on to research-level education, it is of great importance that they be given an opportunity to work independently using different kinds of research methods. Not least, it is important as a preparation for being able to take part in an active way in development work in pre-school, school and adult education. (Government Bill: 1999/2000:135, pages 20-21)4

The outlines for the teacher education program emphasize that the teacher education program is an academic professional education. Lendahls Rosendahl (1998) says that the research in-volved in the degree project is a different element in the teacher education. “Another method is used, where knowledge is produced, but another way of thinking is also expected.” (1998:205) The conclusion derived from her study is that “the degree project holds a potential to develop and change students’ understanding of knowledge and learning, and is in this way a powerful instrument in the education of future teachers.” (1998:208) The question is; could it also con-tribute to developing and improving schools?

On the practical level

The degree project is carried out at the end of the teacher education program. The course spans over a period of ten weeks. The students are intended to do their degree project independently, but with the support of a supervisor. Despite this, they normally write the thesis in pairs, but sometimes alone. The subject of the degree project is planned in close co-operation with the student’s partner school, as a way of finding questions of interest both to the partner school, the student and teachers and researchers involved in the teacher education program. Normally, this is a quite difficult equation to solve. The result is usually a minor “copy” of the doctoral thesis as a model and encompasses the whole research process, from defining a problem to producing a report and defending it in public. The degree projects are, in our case, also to be presented in the partner schools in order to stimulate a pedagogical dialogue, for example, as a pedagogical café or a “pedagogical seminar”. The student may, if they like, publish their work in our uni-versity college database.

What subjects does then a degree project deal with? To get an opinion, we take an example from our university college in the autumn term of 2005. We categorized the content of the titles of 84 degree projects5. (Table 1.)

4

Note: Our translation.

Table 1. Subject areas for degree projects in the autumn term of 2005

Subject areas Numbers

Teaching and learning processes 18

Special education 9

Subject didactics6 16

Reading and learning 10

Genus, discrimination etc. 8

Fundamental values 8

Marks and assessment 5

Other 10

Total 84

A majority (64 percent) of the students have chosen to write their degree project on the teach-ing and learnteach-ing process, for example: approaches and methods, subject didactics and pupils with reading and writing problems. Socialisation aspects (genus, fundamental values and so on) constitute about 20 percent; marks and assessment issues, 6 percent and almost 10 per-cent elaborated on different kinds of subjects, but always within the field of pedagogical work. Accordingly, the chosen subjects headlight practical problems for everyday use in teachers’ work.

Assessing the quality of a degree project

How is it possible to ascertain what qualities the degree projects have? Is it, for example, pos-sible to look upon these as good scholarly work, something we can trust as reliable knowledge and which can also be used to support school development work? In order to underpin the quality there is a set of demands that have to be fulfilled. In our example, the degree project has to fulfil some scholarly and professional demands. These are specified as:

a) Relevance, i.e. the degree project is carried out within an area that teachers are faced with in their occupation

b) Credibility, i.e. it mirrors problems of importance for the teaching profession, which makes it possible to trace a underlying train of thought

c) Complexity, i.e. it shows an awareness of different perspectives in order to interpret teachers’ work

d) An improving purpose, i.e. it shows possible alternatives in order to develop the prac-tice teachers meet in their everyday work, for example, developing new knowledge of school practice, or constructing “new” models and materials that can be used in teach-ing. In the latter case, there has to be written documentation describing possible proce-dures and giving a theoretical perspective

There are also demands regarding the content. The thesis must be problem-oriented and have a clear aim, usually with questions to be answered. It is also necessary to present the methods of data collection and the result has to be clear and understandable. Additionally there are formal and general demands. The thesis must be written in clear and unambiguous language. The content must have a logical and legible plan and a consistent system of references. When the degree project is finished there are criteria for the assessment:

To get the mark Pass, the demand is that the degree project pays attention to the general, the subject and the formal demands prescribed

To get the mark Pass with Distinction, the demands are to fulfil those made for the Pass mark and in addition to show excellent knowledge and ability to manage and discuss the content at a high level of insight and in a creative way, for example, through making in-dependent standpoints, assessments and critical analysis7

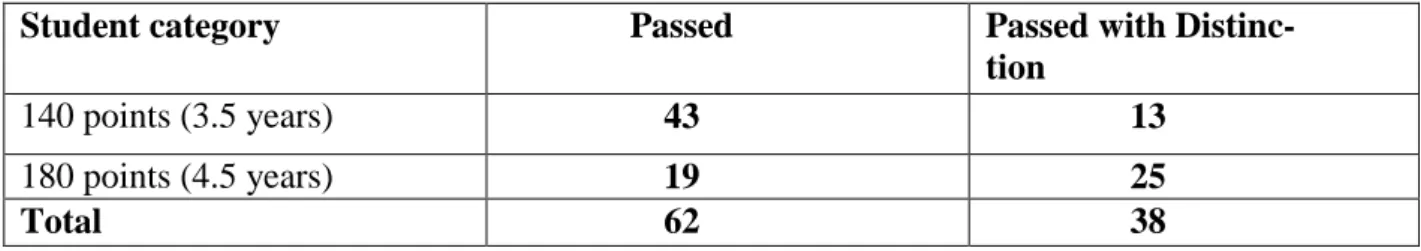

However, the problem seems to be to find out to what degree those criteria have to be ful-filled since these are quite vague when it comes to applying them. Hagström (2005) has stud-ied 20 different books on how to write a degree project and according to her it is hard to give a coherent picture of the advice different authors give on how to assess a degree project. Most of them describe what is to be assessed and what assessment is about. Our conclusion, when it comes to assessing, is that it is up to the assessor and her or his opinion. This leads us to the question of whether it is possible to make the assessment in a relevant and fair way? Before we elaborate on this question, we give an example of how the marks were distributed between different groups of students. We take the results from our own university college for the spring and autumn terms of 20058. (See Table 2).

Table 2. Students’ marks for the spring and autumn terms of 2005 as a percentage of the total

number (N= 212).

Student category Passed Passed with

Distinc-tion

140 points (3.5 years) 43 13

180 points (4.5 years) 19 25

Total 62 38

Almost 40 percent of all the students were awarded a Pass with Distinction grade. Are they good students or are the demands too low? The mark Passed with Distinction was twice as common among students from the four and a half-year program in relation to those on the three and a half-year program.

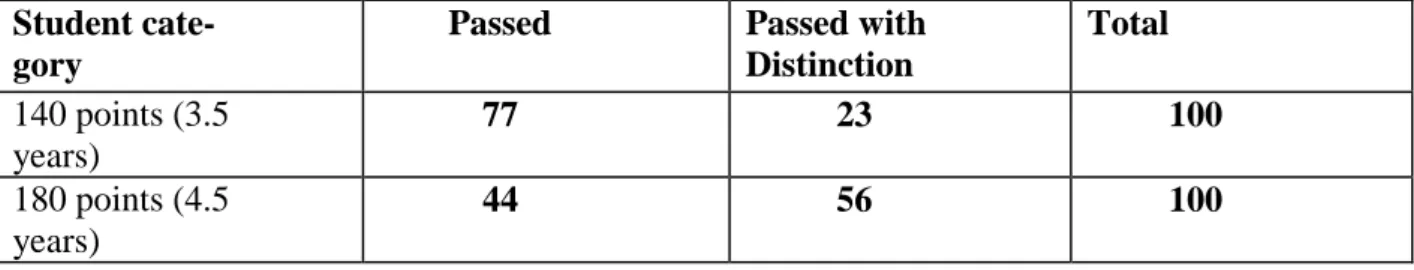

If we calculate the distribution of Passed and Passed with Distinction grades within the two dif-ferent categories of teacher students we find that 56 percent of those on the 4.5-year program have been given the mark: Passed with Distinction and only 23 percent of those on the 3.5-year program. (Table. 3)

7 Note: Our translation from an internal document: The degree project - Information and instructions. (June

2006)

Table 3. Students’ marks for the spring and autumn terms of 2005 as a percentage of each category (N=118 (the 3.5-year program) and N=94 (the 4.5-year program) Total N=212).

Student cate-gory

Passed Passed with

Distinction Total 140 points (3.5 years) 77 23 100 180 points (4.5 years) 44 56 100

The assessing process

In 2005, a working-team within the Pentaplus co-operation project,9 as one of many tasks, was given the job of evaluating how the assessment of degree projects was handled in prac-tice, for example: whether different assessors arrived at the same result. In each university, three degree projects were chosen representing three “levels”: “weak Pass” (P-), “strong Pass” (P+) and “Pass with Distinction” (PD).10

Each member of the group examined 15 degree pro-jects each (in some cases together with one or more colleagues). No degree project had been given the mark Fail (F) when they were examined. The result of the assessment was as fol-lows (Table 4):

Table 4. University assessors’ evaluation of degree projects. (F=Fail, P= Pass (P-, P, P+) and PD= Pass with Distinction)

Degree project11 University12 D G K M Ö D 1 P - P - P- P- F D 2 P P P- P P - D 3 PD P - D PD PD (P+) P + G 1 P P F - P PD P G 2 P PD P P + P G 3 P - P- F– PD P - P K 1 P - P- P P - P K 2 PD - PD PD PD (P +) PD K 3 F F F F F M 1 P + P P+ /PD P PD M 2 P + P- P P - P M 3 PD - F– P P+/PD PD PD Ö 1 P P P PD PD Ö 2 P - P– PD P- P P Ö 3 P P P- P P -

9 The Pentaplus co-operation project encompasses five Swedish universities and university colleges in central

Sweden.

10 The assessment criteria were almost the same at the different universities and the results of the assessments

practically the same in most cases and no formal mark P- and P+ exists: they were used as a working tool in this case.

11 The degree projects have been given a number from 1 – 3 and given a letter indicating from which university

they came.

The result shows that in most cases the results of the assessments agreed. However, in some cases there were larger or smaller differences in the assessments made. In, for example, de-gree project G1 the result varied from F to PD as well as in G3 and M3. When there was disa-greement it was often one assessor who held a different opinion. In case K3, everyone agreed to give the mark F, despite the fact that the degree project had passed and been given a P (- an informal P-, however).

Most of the degree projects had a traditional design and they were research oriented. On the other hand, according to the written opinions of the assessors, there were deficiencies when it came to relating to a scholarly approach. In some cases, the theses could be described more as an investigation than a scholarly text. The students reported what they knew about a subject and made an empirical study that confirmed what they already knew. A problem, when it comes to scientific relevance, could be due to what scientific tradition they belong to. In some respects, the social sciences and humanities have different demands than do the natural sci-ences.

The assessment also included an evaluation of the degree projects and their relation to the teaching profession. They all proved to have a more or less clear connection to the teaching profession. However, in some of the theses it was obvious that the subject reflected a personal interest without being anchored in relevant research or a general knowledge of the teaching profession or the school system.

The conclusion is that, in most cases, the degree projects fulfilled the scholarship demands for qualification for applying as a candidate for a doctorate. Assessment of degree projects from other teacher education programs seemed to be tougher than of those from the assessors’ own program. The differences in the assessment that showed up may probably be explained by dif-ferences between subjects chosen rather than between different teacher education programs. In most cases, the students’ legal security seems to be fulfilled, despite the fact that some of them in this example did not reach the quality level that was expected. Although the degree projects varied much in quality, they seem to be good enough to be used to start pedagogical discussions in schools on the praxis level.

Student teachers’ degree projects as a method of improving co-operation

between the teacher education program and schools

In the following, we discuss how student teachers’ degree projects have a part to play in de-veloping co-operation between schools, students and teacher education.

The degree project is supposed to initiate a process leading to an interesting and important research question. However, making the process work well is problematic. The persons in-volved usually each have a different focus on a problem of interest. Our experiences are that these students, when they are about to become professional teachers, would often like to for-mulate questions they believe to be important in their future work as teachers. They would like to find answers to how to act as a teacher and to a lesser extent they try to elaborate on what teaching is about as a way of obtaining answers to their questions. However, the degree project nevertheless contains elements that make it possible to distance oneself from one’s own “teacher’s desk perspective” and instead understand the teacher’s role in its context and it presents an opportunity to reflect on how the role could be played and see the teacher role with new eyes and from other perspectives and approaches.

Thus, as an element of education, the degree project holds a potential to develop and change the students’ understanding of knowledge and learning, and in this way a power-ful instrument in educating teachers. But it requires that the students’ initial idea of knowledge and learning and of research and science is challenged and that there is a change of meta-cognition. (Lendahls Rosendah, 1998:208)

It gives the student teacher a possibility to realise how to collect, work up and systemise data to create new and action-relevant knowledge. The student teachers have got a tool to use as future professional teachers and to work with school development.

Co-operation with partner schools also demands that their interest in what they consider to be important questions to be investigated should be satisfied. In some cases, the partner schools are clear on this point and they know what help they would like, in other cases, not. In both cases problems may occur. The co-operation may lead to a conflict between the interest of the partner school and the student’s interest. In many cases this problem is solved as student teachers are interested in being helpful about solving concrete and authentic everyday prob-lems and accept what the partner school suggests they should do. If the partner school does not know what help they would like to have, the student usually investigates what he or she is interested in. This, of course, does not have to be wrong, but it risks being an individual pro-ject, something that is helpful for the student, but does not benefit anyone else. Our experi-ences are that many principals generally have a vague opinion about what they would like to develop in their school, or that they have so many areas to choose among that they not are able to choose any of these.

Another aspect is how these research questions might be implemented at the university. A decisive problem is that in small university colleges, groups of researchers do not often exist; there are only one or two researchers in a field. On the other hand, the degree project gives a opportunity to deepen the teacher education program contacts with the field and for individu-al teacher educators to keep up-to-date with what is happening in school, thus giving im-portant input for change and development of the content of teacher education, as well as ini-tiating new research projects that may develop knowledge on teaching practice.

From our experiences, we have seen many living examples of how teacher students’ degree projects bring up important issues about possible areas in need of improvement. In some cas-es, the degree project is followed up by pedagogical dialogues in the partner school, but in most cases they pass almost without a trace. A college report on more than 80 meetings with partner schools during 2004 -2006 gave the following result:

1. Every (!) partner school is interested in getting help from the degree project work in the local school development work

2. There are few who have got actual help from the degree projects

3. The partner schools do not have a clear strategy or organisation for how to use the de-gree projects

4. Several partner school have clearly stressed that they are willing to live up to what is stated in the “partner agreement”13

There are, of course, a lot of possible reasons why the co-operation does not always work well. One is that the degree project work is done rather isolated from the activities that take place in the partner school. Teachers have more than enough trouble trying to solve all of the

everyday problems they face. They actually do not have time to give priority to student teachers and their degree projects. Another reason is that the principals do not have time to give priority to this question, either, although they often are interested in the subject. A third one is that the degree projects show a considerable variation in quality and in usefulness in practice, which may be explained by the amount of time the students have when they write their theses. It is too short to expect the degree project to fulfil the demands necessary in this specific situation, so to say; it does not give enough material to result in concrete actions. As there is usually nobody in the partner school that takes charge of the result, the good inten-tion to co-operate also often fails.

Some conclusions

If it is organised in an appropriate way, the degree project could be seen as a meeting point to bring schools, students and the teacher education program together in order to support co-operation, to develop the activities that take place and to support each partner’s interest. The student teacher has an opportunity to elaborate on a problem that the student finds interesting and important, not only to her or himself. If the partner school is able to define what areas they have to develop, the degree projects may be helpful in this work. The teacher educators and pedagogical researchers may use the degree projects to develop the content of the teacher education program and to initiate relevant research projects. But, there are still obstacles to overcome; there is sometimes a lack of interest and there is a lack of resources, both of mon-ey and of time. The degree project risks being an opportunity to co-operate that is lost if not taken seriously.

References

Hagström, E. (2005) Meningar om uppsatsskrivande i högskolan. Örebro: Studies in Education 12. Örebro universitet.

Proposition 1999/2000:135; En förnyad lärarutbildning.

Lendahls Rosendah, B. (1998) Examensarbetets innebörder. – En studie av blivande lärares