BEVEL ANDER & DON J. D E V ORETZ (EDS.) m AL mö UNIVERSIT Y • m Im 2008 Th E E c ON O m Ic S O f c ITIZENS h IP

The

Economics

of

Citizenship

Editors: Pieter Bevelander & Don J. DeVoretz

mALmö UNIVERSITY

SE-205 06 Malmö Sweden

Cover: Diane Coulombe

Printed in Sweden by Holmbergs, Malmö 2008 ISBN 978-91-7104-079-4 / Online publication www.bit.mah.se/MUEP

Malmö University

Malmö Institute for Studies of Migration, Diversity and Welfare (MIM) SE-205 06 Malmö

Sweden www.mah.se/mim

The economics of ciTizenship

pieTer Bevelander

& don J. devoreTz

(eds.)

Malmö University, 2008

MIM

conTenTs

PREFACE ... 7 AboUT ThE AUThoRs ... 9 INTRoDUCTIoN ... 13

Irene Bloemraad

A Canadian Narrative

1. ThE ECoNoMIC DETERMINANTs AND CoNsEQUENCEs oF CANADIAN CITIZENshIP AsCENsIoN ... 21

Don J. DeVoretz & Sergiy Pivnenko

A Dutch Narrative

2. NATURALIZATIoN AND soCIoECoNoMIC

INTEGRATIoN: ThE CAsE oF ThE NEThERLANDs ... 63

Pieter Bevelander & Justus Veenman

A Norwegian Narrative

3. ThE ECoNoMICs oF NoRWEGIAN CITIZENshIP ... 89

John E. Hayfron

A swedish Narrative

4. ThE ECoNoMICs oF CITIZENshIP: Is ThERE

A NATURALIZATIoN EFFECT? ...105

Kirk Scott

An American Narrative

5. IMMIGRANT NATURALIZATIoN AND ITs IMPACTs oN IMMIGRANT LAboUR MARKET PERFoRMANCE AND TREAsURY ...127

Ather H. Akbari

6. ThE ECoNoMICs oF CITIZENshIP: A sYNThEsIs ...155

PREFACE

The genesis of this volume occurred at a workshop on immigrant citi-zenship acquisition held in 2004 in Malmo, Sweden under the framework of the Willy Brandt Professorship. This inter-disciplinary workshop ultima-tely reflected a deep rift between economists and other social scientists, which in turn led to this economically focused analysis. We are both grate-ful to the workshop participants and Malmo University for supporting this initial effort and shedding light on future research. As scholarly and public interest grew over citizenship issues in North America and Europe, both the Metropolis Project (Vancouver) and the Volkswagen Foundation (IZA) provided funds to support the research for this book. The overarching aim of the editors was to see if economic modeling could provide a general framework to explore the conditioners to immigrant citizenship ascension in both worlds. To the extent that we have succeeded in this task, a large measure of thanks goes to the individual country authors who sought out unique data sets, wrestled with understanding varying concepts of citizen-ship, and had the patience to employ and test the economic model offered in this book. Moreover we would like to thank all anonymous reviewers who read and commented on the initial manuscripts. We also offer many thanks to all authors for the country-specific narratives on citizenship issues preceding each chapter. Last but not least we thank Dr. Diane Coulombe for her careful copyediting and her help in keeping this project moving forward.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Dr. Ather H. Akbari has been with the Economics Department at Saint Mary’s University since 1989. His research has been published in several economics and interdisciplinary journals and has also been quoted in top international and national newspapers and magazines such as The Wall Street Journal and The Economist magazine. Dr. Akbari also leads the eco-nomics domain of the Atlantic Metropolis, a Canadian centre for excel-lence in research on immigration. Dr. Akbari’s extensive past work on immigration includes studies on the public-finance impact of Canadian immigrants and work on their earnings functions and human capital stock.

Pieter Bevelander is an Associate Professor and the current Willy Brandt Research fellow at the Malmö Research Institute for Migration, Diversity and Welfare. He is also a senior lecturer at the School of International Mig-ration and Ethnic Relations, Malmö University, Sweden and a research fellow at IZA, the Institute for the Study of Labour, Bonn, Germany. His main field of research is international migration focussing on various aspects of immigrant integration. His latest research topics include a com-parison of the ethnic social capital in Canada and the Netherlands, social capital and electoral participation of immigrants and minorities in Canada, and the attitudes of the Swedish-born towards Muslims in Sweden. He has published in the International Migration Review, the Journal of Popula-tions Economics, the Journal of Ethnic and MigraPopula-tions Studies and the Journal of International Migration and Integration.

Irene Bloemraad, Assistant Professor in Sociology at the University of Cali-fornia, Berkeley, studies immigration, political mobilization and citizen-ship, placing the U.S. experience in international context. Her recent book, Becoming a Citizen: Incorporating Immigrants and Refugees in the United States and Canada (University of California Press, 2006), argues that the United States’ lack of general integration policies has led to lower levels of citizenship among immigrants in the United States compared to Canada,

10

and poorer outcomes in political participation. Bloemraad has published articles on naturalization, dual citizenship, immigrant community organi-zations and ethnic leadership in academic journals such as Social Forces, the International Migration Review, Social Science Quarterly, and the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. Her current projects, funded by the Russell Sage Foundation, examine the political and civic socialization of mixed status Mexican American families and the role of organizations in facilitating immigrants’ civic and political participation. She regularly talks about immigration to community groups and the media and belongs to IZA, a German institute devoted to studying immigration issues. Dr. Don J. DeVoretz is a Professor of Economics at Simon Fraser Univer-sity where he was the Co-Director of RIIM, Vancouver’s Centre of Excel-lence on Immigration Studies from 1996 to 2007. Dr. DeVoretz has held visiting appointments at Duke University, University of Ibadan (Nigeria), University of the Philippines, University of Wisconsin, and the Norwegian School of Economics. He was the Willy Brandt Guest Professor at IMER, Malmo University in 2004. He is a Research Fellow with IZA (Germany), the Migration Research Group (Germany), and the Asia Pacific Founda-tion of Canada. Dr. DeVoretz was named a British Columbia Scholar to China in 2000. His current research interests include the economics of immigration with special emphasis on “brain circulation” and citizenship issues. His research findings have been reported in professional journals and major print and electronic media.

John E. Hayfron received his PhD in economics from the University of Bergen in Norway in 1999. He is currently a Visiting Assistant Professor at Western Washington University. He has taught economics courses at various colleges and universities in Canada and the United States. His research is in the area of labour economics with special interest in the eco-nomics of immigration and the ecoeco-nomics of gender and race. His publica-tions have appeared in the Journal of Population Economics, Applied Eco-nomics, and in edited books.

Sergiy Pivnenko was born in Ukraine where he received degrees in physics and economics. In Canada he obtained a graduate degree in economics and worked as a research consultant. In 2005 Pivnenko completed work for the Government of British Columbia on the economic profiles of immigrants. His research contributions cover the labour market and the public-finance performance of immigrants and have appeared in refereed journals and working papers.

Kirk Scott in an Associate Professor at the Centre for Economic Demo-graphy and the Department of Economic History at Lund University. His research has dealt primarily with broadly defined issues of immigrant inte-gration. Topics such as immigrant income and employment outcomes were of initial interest, while more recently the focus of his research has shifted towards other measures of integration such as health, mortality, and ferti-lity. His recent publications have appeared in Population Studies, the Inter-national Migration Review, Demographic Research, the Journal of Socio-Economics, and several anthologies.

Justus Veenman is a Professor of Economic Sociology at the Economics Department, Erasmus University Rotterdam. He studied Economics in Rot-terdam and obtained his PhD from Utrecht University. His research focuses on social inequality, in particular on ethnic minorities in education and on the labour market. He has published several books and numerous articles (see www.uu.nl/uupublish/onderzoek/onderzoekcentra/ercomer/). From 1986 until 2005 he was the Director of the Institute for Sociological and Economic Research of Erasmus University Rotterdam.

INTRODUCTION

Irene Bloemraad

Debating Immigrant Citizenship

Why would someone born and raised in one country decide to become a citizen of another? Does acquiring a new citizenship change one’s life? Does it matter?

More and more, countries of immigration imply that citizenship matters as an issue of national identity. Through much of the 1980s and early 1990s, Western countries extended rights and public services to non-citizen immigrants. The steady erosion of distinctions between non-citizens and non-citizens, coupled with seemingly greater tolerance for diversity and multiculturalism, led some to bemoan the devaluation of citizenship (Schuck 1998) while others heralded a new postnational age of member-ship that would make state-centered citizenmember-ship obsolete (Bauböck 1994; Soysal 1994).

Today, the celebration of citizenship and integration has replaced talk of multiculturalism from Australia to the Netherlands. Countries across continental Europe are introducing integration and language classes to spur immigrants’ incorporation. The United States changed the test required of would-be Americans to make it more “meaningful,” while Great Britain instituted its first-ever citizenship ceremony in 2004, presided over by Prince Charles, to underscore the significance of British citizenship. Impli-citly or expliImpli-citly, citizenship is portrayed as a marker of, or perhaps a way-station to, full social and political integration.

This book takes a different tact. It puts the focus on the economic aspects of citizenship, asking three questions: What are the economic deter-minants animating an immigrant’s choice to acquire citizenship? What are the economic consequences of choosing citizenship for the foreign-born worker? What are the economic consequences of immigrants’ citizenship for the country of reception?

In asking these questions, the volume joins an on-going conversation of philosophers, sociologists and political scientists (not to mention

politi-14

cians, policy-makers and pundits). It takes the citizenship discussion in a new direction by bringing together, for the first time, an international group of economists who try to outline an economics of citizenship applicable to both traditional immigrant-receiving countries and the new countries of immigration in Europe.

Do we need more voices in this already cacophonous debate over citi-zenship? The contributions in this book suggest we do. The volume asks questions in new ways and is undergirded by assumptions not frequently articulated in existing discussions. It has the singular advantage of asking similar questions across different host societies and national origin groups. Certain chapters rely on unique data sources that offer greater possibilities for modeling citizenship than before. The sum of these parts takes a big stride in bringing economists and economic approaches into the study of immigrant citizenship. While not everyone will agree with the economic approach adopted here, there is much to learn.

To Think Like an Economist: The Promise and Pitfalls of an

Economic Approach

Many in the social sciences worry about the “imperialism” of economists, who have progressively used economic assumptions and thinking to tackle problems outside the traditional purview of economics.1 To be frank, I’m not immune to these worries. As a political sociologist with a long-standing interest in immigrant citizenship, I felt some trepidation when asked to write the introduction to a book entitled The Economics of Citizenship. Can citizenship be reduced to economic calculations?

Economic assumptions and models are seductive for their simplicity and clarity. They might consequently help us cut through the tangled terrain of existing citizenship studies. For example, despite countries’ growing focus on citizenship as a tool or badge of national identity, a number of the vignettes that begin each chapter distinguish between self-identity and legal status. In the words of one migrant from the Middle East, currently a Swedish citizen, “I have never felt ‘Swedish,’ and I do not believe that one can become a Swede through naturalization. The most one can expect is to become a citizen of Swedish society.” Such sentiments hint that a more instrumental approach to citizenship may not be amiss. What do we learn from taking an economic approach to immigrant citizenship? And what do we miss?

1 See, for example, non-economists’ reaction to the work of Gary Becker or to the success of Freakonomics (2005) by Steven Levitt and Stephen Dubner.

Economic Assumptions

The contributions in this volume offer, in line with mainstream economics, an elegant rational actor model of citizenship. Immigrants make a rational choice over whether or not they will acquire citizenship by weighing the benefits of citizenship acquisition against the costs of naturalization. When benefits outweigh costs, immigrants take up citizenship. When the ledger weighs more heavily on the negative, immigrants opt to remain non-citi-zens.

This approach has many benefits. It is simple. It can be readily applied in different contexts and across immigrant groups, one of the key contribu-tions of this volume. Thus, we learn that while Canada and Sweden allow dual citizenship (since 1977 and 2001, respectively), the Netherlands and Norway do not. Surely one of the biggest costs of naturalization is losing one’s prior citizenship. We would imagine, ceteris paribus, that immigrants would be more likely to take up citizenship in places where they are not required to renounce a prior nationality.

Yet the evidence presented across the country cases does not support such a simple conclusion. Citizenship levels and rates are very high in Canada, a country with a longstanding acceptance of dual citizenship, but they are also remarkably high in the Netherlands, which only allows dual citizenship in very particular cases. Further, the Swedish data, analyzed by Kirk Scott, finds that the 2001 law allowing multiple citizenships had no appreciable effect on citizenship trends in that country.

The benefits of citizenship also vary across countries. As Ather Akbari outlines in the chapter on the United States, since 1996 the advantages of U.S. citizenship have become more pronounced. Non-citizens now face more restricted access to public benefits and enjoy less recourse against deportation in the event they are convicted of minor crimes. The benefits of citizenship and costs of non-citizenship appear less stark in Canada and the Netherlands. In the Netherlands, a country with a strong social security net, access to benefits is not restricted by citizenship, a situation similar to that in Canada where only pension benefits for those living outside the country involve a citizenship component. Yet American levels of naturali-zation are below those of the other two countries, and appear to remain lower even when we try to adjust for the large undocumented population in the United States, as Akbari does.

Maximizing What? In Comparison to What?

This quick, somewhat unsuccessful, application of a cost/benefit approach suggests that the simple model needs to be unpacked. One key question arises: What, exactly, are immigrants trying maximize when they weigh the

16

costs and benefits of citizenship? Most contributors to this volume would agree that immigrants seek something we might call “quality of life”, an assumption that this sociologist would find unproblematic. Of course, the devil is in the details. What constitutes “quality of life” and how might this vary for different immigrants in different countries of immigration?

One of the most consistent, and consequently important, findings across the five substantive cases in this book is the identification of diverse patterns of citizenship acquisition among refugees, migrants who come through family reunification, economic migrants from less developed countries (whether low, semi or high-skilled) and high skilled migrants from other OECD countries. Almost every chapter reports that refugees (or, more specifically, people from countries that have produced substantial refugee flows) rush to acquire citizenship quickly and at high levels. In contrast, highly skilled immigrants from North America or Europe who move to another highly developed country drag their feet, only naturalizing after long periods of residence. In between, we find those from the develo-ping world or Eastern Europe who arrive through family reunification pro-visions or as economic migrants.

What can we make of these patterns, quite stable across all five countries? First, they demand that we add a reference point to any discus-sion of ‘quality of life’ and consider the distance separating immigrants’ current situation and their reference point, likely the country they left. If a German leaves Europe for the United States, the difference in living condi-tions, and the attractiveness of return, will be quite different compared to a Burmese refugee fleeing political persecution and economic misery in her homeland. All the chapters in this volume suggest that the citizenship cal-culations of migrants from highly developed countries differ from others. This finding has important policy implications since immigrant-receiving countries appear to be increasingly in competition with each other in trying to attract high-skilled migration. If host countries want these high skilled immigrants to become citizens, then they should target elite migrants from the developing world, something that might contribute to the brain drain from South to North. If they instead entice skilled workers from other highly developed countries, they run the risk of more limited civic or politi-cal incorporation, given this group’s reluctance to change passports.

A second challenge comes in defining and measuring “quality of life,” assuming that immigrants do indeed base citizenship decisions on how long-term improvements in life conditions off-set the short term bureaucra-tic hassle and financial cost of citizenship (not to mention feelings of dis-loyalty to the home community). Many of the naturalization vignettes embrace a capacious view of quality of life. The Canadian citizen of

Chinese birth speaks warmly of the Canadian lifestyle and norms, inclu-ding respect, equality, freedom, the rule of law, a cleaner environment and better childhood education. The Swedish citizen who differentiates Swedish ethnicity from citizenship appreciates the values of democracy and fairness that inform the Swedish social institutions. The Vietnamese refugee who has become a U.S. citizen provides a poignant story giving substance to the statistical finding that refugees, in particular, take up citizenship quickly. Few are likely surprised to learn that, given persecution in Vietnam, the security and stability of legal membership in the United States become attractive.

Unfortunately, the analyses in this volume are limited by available data in their conceptualization and modeling of costs and benefits as well as quality of life. As a few authors point out, many statistical datasets do not include enough immigrants for complete models of citizenship decision-making. In the North American case, researchers use the U.S. and Cana-dian censuses, which offer excellent coverage of immigrant populations, but a relatively limited selection of demographic and socio-economic vari-ables. As a result, quality of life, or economic considerations more specifi-cally, get reduced to labour market participation and income. Immigrant citizens are compared to non-citizens to see whether the former are more likely to be employed or have higher income than the latter. The vignettes suggest that, from the perspective of the immigrant, employment and income are minor considerations. This might help to explain why naturali-zed citizens in Sweden or Norway do not appear to enjoy an employment benefit.

Moving Beyond the Atomized Rational Actor

Perhaps part of the problem lies in seeing the citizenship decision as one of individual choice rather than as one nested in social networks involving family, friends and others in the community (Bloemraad 2006). As Don DeVoretz and Sergiy Pivnenko note in passing, some Chinese migrants in Canada might view citizenship as a family strategy, where one spouse keeps Chinese citizenship while the other takes on Canadian citizenship, ensuring that the family has two options. Conversely, the vignettes of immigrant citizens in Sweden and Norway both mention relationships to nationals of those countries as part of the citizenship process. These stories suggest a pattern of citizenship homophily rather than citizenship splitting. In either case, it raises the question of how families and households, rather than just individuals, make decisions about citizenship.2

2 This argument can, of course, be extended to children. If children born in the country of residence acquire that county’s citizenship at birth, parents might use the children’s

18

The Mechanism of the Citizenship Benefit

While the findings on the economic consequences of citizenship reported here are mixed likely beneficial to the society as a whole, possibly but not invariably helpful to the individual migrant the analyses do find a positive association between citizenship and economic outcomes in some cases. Why might this be so? Correlation analyses cannot tell us exactly what mechanisms link citizenship and economic outcomes, but the authors provide some helpful suggestions for thinking through this problem.

The most straightforward answer, laid out in all chapters, centers on restricted access to certain jobs. In every country, specific jobs (be they police work, as in the Netherlands, top banking positions, as in Norway, or high-level civil service or military positions in all countries) are only open to citizens. It is not clear, however, whether access to such jobs drives a significant proportion of citizenship decisions. Ideally, we would need panel data over a relatively long time period, non-existent in many cases, to see whether we can identify occupational change before and after natu-ralization.

Other explanations for why citizenship might improve economic out-comes are more subtle. Various authors point out that citizenship may fun-ction as a signaling mechanism, perhaps convincing a native-born employer to take on an immigrant worker. DeVoretz and Pivnenko suggest that citi-zenship might communicate greater attachment to Canada, and perhaps a longer commitment to a particular company or job, and Akbari hypothesi-zes that citizenship could signal to employers “greater knowledge of local customs and traditions that is essential for a firm’s success.” If this is true, it is especially noteworthy that those from highly developed countries, likely to be light-skinned, are less likely to naturalize compared to those from the developing world, individuals probably more likely to have darker colored skin. If signaling is part of the benefit of citizenship, does this mean that light-skinned immigrants face less discrimination and do not need signals as much as darker-skinned migrants who face a greater employment or promotion hurdle? The signaling hypothesis also begs the question of whether employers even know or ask about citizenship status in making hiring and salary decisions.

citizenship as “insurance” and not naturalize themselves, or they may decide to become a citizen in order to share the same nationality as their children. In this light, Akbari’s finding that having children under 15 in the household decreases the odds of citizenship would appear to support the first hypothesis rather than the latter. It is possible, however, that the finding is a statistical artifact, since the comparison groups become both families without any children and families with children over 15 who might or might not live in the household.

Citizenship might have an economic influence in a different way. Pos-sessing citizenship might increase the immigrant’s sense of self-efficacy or change time horizons in such a way that he or she demands higher wages or goes after better jobs. We can imagine, for example, a situation where an immigrant assumes that he will return home after a number of years making money in a particular country. However, with time, the immigrant becomes integrated, builds social networks and considers staying longer. Eventually the person decides to become a citizen and, once the decision is made, starts searching for a new job with greater chances for mobility, since the desire to return to the country of origin has been put aside or delayed until retirement.

Self-Selection Biases and Omitted Variables

This last scenario (of the immigrant who finally decides to stay, and becomes a citizen in consequence) gets at the heart of a problem confronting almost all statistical analyses of citizenship. Does citizenship, on its own, drive eco-nomic or other outcomes, or is the independent effect of citizenship insignifi-cant once we appropriately model the differences in characteristics, motiva-tions and situamotiva-tions of those who do and do not naturalize? Put another way, are there unobserved variables that both increase the probability of naturali-zation and affect economic outcomes measures? Almost all the authors note the difficulty of untangling causality. The longitudinal panel data analyzed in the Norwegian chapter by John Hayfron and in the Swedish chapter by Kirk Scott consequently deserve special note as an important advance in our ability to track immigrants before and after naturalization.

Policy Implications and Future Research

Readers will want to delve into the individual chapters, and read across them, for the useful overviews of citizenship laws and benefits as well as the specific findings for each country. A few policy implications deserve mention in closing.

First, as Don DeVoretz and Pieter Bevelander outline in the conclusion, there does not seem to be any simple relationship between the openness or difficulty of national citizenship regulations and aggregate naturalization patterns. This suggests that immigrants’ citizenship decisions go well beyond a simple cost/benefit analysis based solely on laws. This finding includes the case of dual citizenship, a topic of public debate in countries such as Canada, the Netherlands and Sweden. Perhaps the citizenship laws of the country of reception matter much less than the laws in the country of origin. More generally, economic, social, cultural or political contexts must affect citizenship decisions more than any one law.

20

Second, current interest in high-skilled, elite immigrants in countries such as Germany, as well as the long-standing immigration policy favoring skilled economic migrants in Canada and Australia, might have to be re-thought if countries truly wish to maximize national identity over human capital gains. A number of chapters suggest that foreign-born citizens provide greater fiscal gains to the national treasury than non-citizens, but high-skilled immigrants from developed countries are reluctant to take on a new passport. DeVoretz and Pivnenko suggest that high-skilled immi-grants, predominantly from non-European countries, might acquire Cana-dian citizenship only as a human capital enhancement that allows them to move on to a third country to pursue further economic success. Thus, mig-rants to Canada might quickly acquire Canadian citizenship in order to more easily move to the United States, while immigrants may see Sweden as a way-station to mobility within the European Union. Either scenario does little to enhance national identity or civic cohesion in the short or medium term.

In line with this, the analysis of Dutch citizenship by Pieter Bevelander and Justus Veenman is particular noteworthy as they are the only scholars who are able to do a direct evaluation of Dutch integration classes. Such classes are part of the turn toward national identity across Europe, yet the authors find no effect on citizenship among the refugees that they study. These results raise the question of whether integration programs really help immigrant incorporation, or whether they are largely publicity stunts to mollify a native-born public worried about immigration.

Whatever one’s thoughts about the goals of citizenship, be it for immi-grants or the host society, this initial foray into an economics of citizenship will provide much food for thought.

I first came to Canada in 1999 as a visiting scholar under the Canada-China Scholars’ Exchange Program. This visit marked the beginning of a new chapter in my life. During my visit, I decided to apply for immigration to Canada. In the following year, my application was approved, and my family, including my spouse and my then 7 year old son, landed in Canada. After three years of continuous residence in Canada, we all became eligible for Canadian citizenship. On January 13th, 2005, just two days before my family moved into a newly purchased home in Vancouver, we all took our oaths and became Canadian citizens.

Many immigration stories can be explained by the push-pull theory. My story lies more on the pull side. After 16 years of schooling in China and 2 years in Europe, I was endowed with rich human capital and sought an outlet for it. I considered Europe when I was completing my post- graduate education. I also thought about Australia after returning to Shanghai from Europe. Finally, Canada came into my sight.

The choice of Canada as a destination was optimal for my family and I when we were thinking of where to move to. My education and profes-sional background gave me enough points to pass the so-called point system. The visiting scholarship provided me with experience in the Cana-dian workplace. Most importantly, the contacts and networks I was able to establish during my initial visit helped me to acquire a job immediately after I landed in Canada. Needless to say, Canada’s cleaner environment, better childhood education, and more relaxed and convenient lifestyle all entered into the equation in a positive way.

Canadian citizenship is regarded as something of convenience by some. To me, it is the outcome of a three-year term experiencing real life in Canada. It is about the lifestyle that my family and I enjoy. It is about values, namely: respect, equality, freedom and rule of law, which my family and I appreciate. Some people suggest that citizenship is a sense of belong-ing. Yes, I believe that I belong in both Canada and China, although China does not recognize dual citizenship. Even though I fully committed to a new homeland, it is morally unacceptable to disregard a place where my Mom gave birth to me.

Now, like many other Canadians, I pay taxes, buy retirement funds, pay my mortgage, and sometimes comment on Canadian policies and social problems. This is the life I have chosen.

Chapter 1

the eCONOMIC DeterMINaNtS

aND CONSeQUeNCeS OF CaNaDIaN

CItIZeNShIp aSCeNSION

Don J. DeVoretz & Sergiy Pivnenko

Introduction: Issues and Stylized Facts

Canada’s original 1947 citizenship act was born out of the sacrifices endured in World War two and was an explicit statement of independence from its heretofore citizenship ties to great Britain. However, by the 1970s Canada was witnessing a transformation in its population with annual immigration flows of over 250,000 or one per cent of its population base. Moreover, this immigrant population was no longer european-based and immigrant integration in a multi-cultural framework became a paramount policy objective. to this end, one of the long-term goals of Canadian immi-gration policy was to insure that the majority of its foreign-born arrivals became citizens. the Canadian ministry of immigration was often charged to perform both immigrant selection and citizenship functions.1

Under the 1977 Citizenship Act, the ease of ascension under the mixed principles of jus sanguinis and jus soli can be seen by the relatively modest requirements for naturalization (see Appendix A). in sum, the basic requi-rements to attain citizenship in Canada include: 3 years in residency, being 18 years of age or older, having a knowledge of one official language and an adequate knowledge of citizenship responsibilities.2 in addition, dual citizenship has been permitted since 1977; this resulted in a substantial number of naturalized Canadians living outside of Canada conferring citi-zenship on subsequent foreign-born generations.3

1 the title of the ministry is Citizenship and immigration Canada. in the past, the immigration ministry was merged with the Ministry of Justice, and, prior to that, with the Ministry of Manpower and immigration. each re-organization of the immigration ministry reflected the perspective of successive governments on issues surrounding immigration.

2 See Appendix A for details.

24

Citizenship Issues

this cursory description of the ascension process belies the degree of con-troversy that has arisen in Canada with respect to citizenship acquisition. For example, some immigrant groups have recently argued that the three-year waiting period is too long and presents a legal employment barrier. the plaintiffs in this legal case argued that both job and earnings discrimi-nation arose under this requirement, since immigrants without citizenship were unable to practice their profession and enjoy the relatively high ear-nings derived from a federal position. in 2003 the Canadian Supreme Court upheld the citizenship requirement for an array of federal government jobs, and ruled against an immigrant class action suit to recover damages from this alleged discrimination.4

Another issue has arisen as a byproduct of linking dual citizenship pro-visions with the growth in return migration of erstwhile Canadian grants. it has been observed that over 25% of the post-1986 Chinese immi-grants to Canada had returned to Hong kong or China by 2004, many with Canadian citizenship (DeVoretz & Ma 2002). Canadian policymakers have made ambivalent pronouncements over the economic impact of this phenomenon. Some policymakers consider the returning erstwhile Cana-dian immigrants a CanaCana-dian asset which will increase trade and invest-ment. other observers are less sanguine and feel that these Chinese-Cana-dian emigrants represent a potential future liability, especially if they return to retire, thus putting economic pressure on the social system.5 in addition, the dramatic rescue of 12,000 naturalized Canadian citizens in Lebanon in 2006 highlighted the issue of the potential political and economic costs inherent in a dual citizenship policy predicated on the notion of a capstone integration tool. these two diaspora related policy issues have put into question the efficacy of dual citizenship, the relative ease of citizenship ascension and the portability of the rights and obligations of Canadian citi-zens living outside of Canada.

Stylized Facts

one long-term goal of Canadian immigration policy is to insure that the majority of its foreign-born arrivals become citizens. to this end, the current Canadian Ministry of Citizenship and immigration performs both

4 the Court argued in the majority that, since there was no barrier to becoming a Cana-dian citizen, then inherently immigrants did not face discrimination, but just a waiting period which applied to all immigrants.

5 of course, there are many non-economic objections to returning immigrants, including an alleged lack of patriotism or failure to integrate into the Canadian economy.

oF CAnADiAn CitizenSHiP ASCenSion

immigrant and citizenship selection functions.6 the process of citizenship acquisition is straightforward. in fact, the majority of foreign-born perma-nent immigrants to Canada are entitled to apply for citizenship after a three-year period of residency; thus, the 2001 Census of Canada reports that 74.6% of Canada’s foreign-born residents are citizens. in 2001, 57% of immigrants who had been residents for four to five years had become Canadian citizens. Moreover, among those who had lived in Canada for 6 to 10 years, 79% were citizens and among those who had been in the country for 30 years or more, 90% were citizens.

Census data also show that recent groups of immigrants are taking less time to become Canadian citizens than their previous counterparts. the 1991 Census showed that just over half (51%) of immigrants who had been residents for four to five years had become citizens. the proportion in 1981 was only 42%.

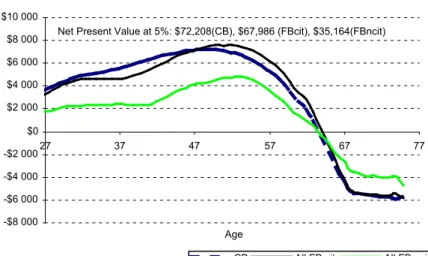

nonetheless, variations in acquisition of citizenship appear. Figure 1 portrays the important observation that there are differential rates of citi-zenship ascension by immigrants for each year in residence in Canada and by their country of origin.

Figure 1. Cumulative percentage of naturalizations among permanent immigrants from high income countries (UK, USa, Germany, Italy, Netherlands) and low income countries (China and India)

in fact, Figure 1 reports that over one-third of the newer immigrant flows from China and india ascend to citizenship after 15 years in residence.7 However, by their 35th year in residence 60% of the Chinese and indian stock of residents have acquired citizenship. A dramatically different 6 Until 2002 the Ministry also was in charge of border security and had the power of deportation at its disposal for non-citizens.

7 the Census of Canada does not provide any information on the year of citizenship acquisition.

Source: Authors’ tabulations from 2001 Census of Canada, Statstics Canada PUMF.

26

picture emerges for Canada’s traditional immigrant source countries of Western europe and the United States. Here only 10% of the immigrant stock naturalize in their first 10 years in Canada and one third after 35 years in residence.

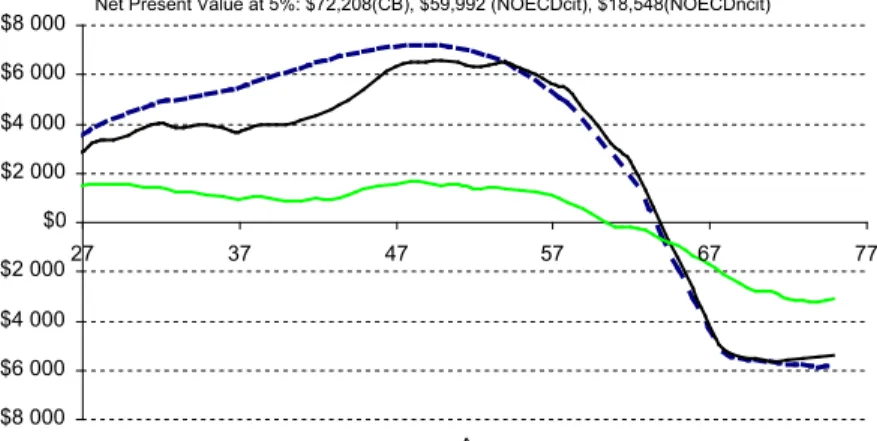

As shown in Figure 2, the level of development of the immigrant’s source country affects citizenship ascension rates. in fact after 10 years in residence, about 81% of immigrants from non-oeCD countries become Canadian citizens. After the 25th year in residence, the process ends as the remaining stock of residents from developing countries (non-oeCD) have largely acquired citizenship.8 Similar but less dramatic picture emerges for immigrants from the oeCD – Canada’s traditional source countries in Western europe and the United States. Here only about 61% of those who have been in Canada for 6-10 years ascend to citizenship. this is about 10% higher than a similar observation made in 1996 Census. Figure 2 shows a nearly 20% gap in ascension rates between oeCD and non-oeCD immigrants which persists until 25-30 years in residence.

in sum, even given Canada’s relatively high rate of citizenship ascen-sion substantial variations in acquisition rates occur across time and place which we will attempt to explain below.

Figure 2. ascension to Canadian citizenship by immigrants from OeCD and non-OeCD countries

Literature review

the economic literature on citizenship primarily consists of two separate views. one view attempts to rationalize an immigrant’s decision to acquire citizenship, and the other investigates the economic consequences of such a decision. the evidence on the determinants of acquiring citizenship remains 8 An unknown number of the original entry cohort could have disappeared after 25 years and this would produce an upward bias in the rate of citizenship acquisition.

Arrival cohorts

Percentage of citizens in arrival cohorts

oF CAnADiAn CitizenSHiP ASCenSion

highly controversial, largely due to the specifics of the populations studied and the varying nature of the data used. While some authors (kelley and McAllister 1982; Portes & Mozo 1985) insist on the importance of socio-economic variables such as education, occupation and income, others (Bernard 1936; Barkan & khokhlov 1980; Portes & Curtis 1987) put forward cultural assimilation and demographic arguments as the major determinants of an immigrant’s naturalization decision. With the aid of 1980 U.S. Census micro data, yang (1994) was the first to apply a cost-benefit framework to investigate the effects of individual characteristics and the socio-economic conditions of the immigrant’s home and host country on the immigrant’s citizenship decision. yang’s findings indicate that cultural integration plays a more important role than economic inte-gration in the U.S. immigrant’s naturalization decision. Age at immigra-tion, marital status and the presence of children were among the demo-graphic factors that increased the odds of an immigrant becoming a citizen. While the home country level of development proved to be a significant predictor of immigrant’s naturalization decision, the availability of dual citizenship did not obtain the expected effect.

Another stream of studies ignored the economic rationale for beco-ming a citizen and addressed only the possible economic impacts derived from the immigrant ascending to citizenship. While Bratsberg et al. (2002) ignore the economic rationale for becoming a citizen, they do address the possible economic impact of immigrant citizenship in the United States labour market. Using a youth panel study, they find that immigrant ascen-sion to citizenship alters the immigrants’ occupational distribution and raises their earnings. Moreover, they argue that these effects are greater for immigrants from less developed countries.

other economic studies of citizenship are even more limited in scope since they mostly incorporate the citizenship effect in an ad hoc manner or as addendum to a larger study. Pivnenko and DeVoretz (2003) found a strong citizenship effect on Ukrainian immigrant earnings in Canada. Mata (1999) reports no evidence on the economic impact of Canadian citizen-ship on immigrant earnings after conducting a principal components ana-lysis with 1996 Canadian data. in reviewing the economic outcomes of Chinese-Canadian citizens who returned to Hong kong, DeVoretz and zhang (2004) found that citizens earned higher incomes than any other resident group in Hong kong. For his part, Bevelander (2000) reports that the log-odds of obtaining employment improved for those immigrants to Sweden who obtained citizenship in 1990.

We conclude from this brief literature survey that studies of citizenship ascension and its economic impact are fragmented and limited in scope. in

28

addition, this literature review suggests that economic modeling appears particularly difficult because of demanding data requirements and a need to model strong institutional components affecting the labour market out-comes.

Data

Both the legal process to obtain Canadian citizenship and our model design dictate data selection and variable definitions. in this study, we select a population of immigrants from the 2001 Census of Canada Public Use Microdata Files (PUMF). in order to ensure that potentially-naturalized citizens have met the time requirements to apply for Canadian citizenship, we restrict our sample to immigrants who landed prior to 1998.9 Since our model focuses on the wage effect that may arise from citizenship acquisi-tion by employed foreign-born workers, we would ideally like to have wage rate data. However, since our data source does not provide informa-tion on hourly wage rates, our regression analysis must be performed using the individual’s annual wage or salary earned in 2000, controlled by weeks worked in that year.10 Also, any individual records reporting inconsistent observations on wage, salary income, or weeks worked are excluded from our data set.11 Moreover, since we focus our analysis on employed, wor-king-age immigrants, individuals over 64 and under 25 years are excluded from our data set.

our model also dictates that the majority of the data used as explana-tory variables are recoded as zero-one dummy variables. Marital status (MArrieD) is coded as a 1- for legally married, or 0- otherwise. next, we recoded the educational variable ‘highest degree earned’ into a string of dummies indicating the acquisition of either a trades certificate or diploma (DiPL), bachelor degree (BACH), above bachelor (BACHPL, i.e. masters or medical degrees) or an earned doctorate (PHD). Similarly, we transfor-med the occupational variable of the immigrant into a series of dummy variables representing professional (ProF), managerial (MAng) or a skilled (SkL) classification.

9 Landed immigrants must live in Canada for at least three of the four years preceding their citizenship application.

10 given the annual nature of our data, we must ignore the possibility that our wage data may contain earnings derived from overtime premiums, or that foreign-born resi-dents may work at more than one job.

11 that is, positive earnings for zero weeks or zero earnings for positive weeks. in addi-tion, by restricting wage earnings to a minimum of $1,000 we further cleaned our sample of those who reported hourly or weekly wages instead of annual earnings.

oF CAnADiAn CitizenSHiP ASCenSion

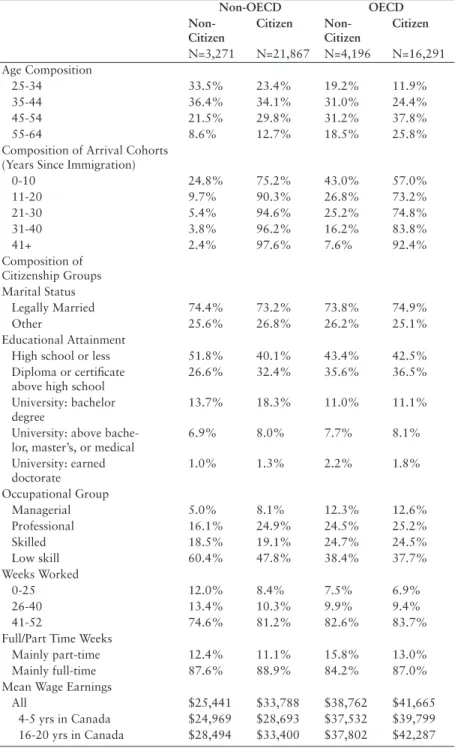

table 1. Descriptive statistics for selected immigrant groups by country of origin and citizenship status

Non-OECD OECD Non- Citizen Citizen Non- Citizen Citizen n=3,271 n=21,867 n=4,196 n=16,291 Age Composition 25-34 33.5% 23.4% 19.2% 11.9% 35-44 36.4% 34.1% 31.0% 24.4% 45-54 21.5% 29.8% 31.2% 37.8% 55-64 8.6% 12.7% 18.5% 25.8%

Composition of Arrival Cohorts (years Since immigration)

0-10 24.8% 75.2% 43.0% 57.0% 11-20 9.7% 90.3% 26.8% 73.2% 21-30 5.4% 94.6% 25.2% 74.8% 31-40 3.8% 96.2% 16.2% 83.8% 41+ 2.4% 97.6% 7.6% 92.4% Composition of Citizenship groups Marital Status Legally Married 74.4% 73.2% 73.8% 74.9% other 25.6% 26.8% 26.2% 25.1% educational Attainment

High school or less 51.8% 40.1% 43.4% 42.5% Diploma or certificate

above high school 26.6% 32.4% 35.6% 36.5%

University: bachelor degree

13.7% 18.3% 11.0% 11.1%

University: above bache-

lor, master’s, or medical 6.9% 8.0% 7.7% 8.1% University: earned doctorate 1.0% 1.3% 2.2% 1.8% occupational group Managerial 5.0% 8.1% 12.3% 12.6% Professional 16.1% 24.9% 24.5% 25.2% Skilled 18.5% 19.1% 24.7% 24.5% Low skill 60.4% 47.8% 38.4% 37.7% Weeks Worked 0-25 12.0% 8.4% 7.5% 6.9% 26-40 13.4% 10.3% 9.9% 9.4% 41-52 74.6% 81.2% 82.6% 83.7%

Full/Part time Weeks

Mainly part-time 12.4% 11.1% 15.8% 13.0%

Mainly full-time 87.6% 88.9% 84.2% 87.0%

Mean Wage earnings

All $25,441 $33,788 $38,762 $41,665

4-5 yrs in Canada $24,969 $28,693 $37,532 $39,799 16-20 yrs in Canada $28,494 $33,400 $37,802 $42,287

30

Based on the above definitions, table 1 provides some stylized facts by immigrant source country and citizenship status.12 Since our earlier work indicated that citizenship acquisition might be a by-product of the level of development of the foreign-born Canadians’ country of origin, we further divided our data into immigrants from oeCD and non-oeCD countries.

given that we will employ a human capital model of earnings, we focus our analysis on key socio-economic variables and observe, except for marital status, substantial differences across immigrant groups, as defined by citizenship and source country. For example, in the 25-44 age group about 57.5% of non-oeCD immigrants and 36.3% of oeCD immigrants reported Canadian citizenship. Also, naturalized citizens from non-oeCD countries are better educated than non-citizens (27.6% vs. 21.6% with a post-secondary degree) and fewer of them are in unskilled occupations (47.8% vs. 60.4% for non-citizens). in contrast, oeCD immigrants do not show variations in educational attainment or skill level across citizenship status. Finally, citizens from of non-oeCD origins work more weeks than non-citizens, while slightly more citizens of oeCD origins are employed full-time than non-citizens.

this combination of full-time employment and higher skill levels of foreign-born citizens contributes to greater annual wage earnings for citi-zens than non-citiciti-zens. Among non-oeCD origins, the average citizen-non-citizen annual earnings differential in 2000 was about $8,300, while a similarly defined differential for oeCD immigrants was about $3,000.

this brief overview indicates that citizenship status is correlated with larger human capital endowments and a more robust earnings performance for naturalized Canadian immigrants.

Model

Citizenship ascension

in the first stage or the decision of the immigrant to ascend into citizenship, we use a well-known economic citizenship model owing to DeVoretz and Pivnenko (2006). the basic argument is as follows: the economic problem that immigrants face is to choose a state -- citizenship or non-citizenship -- which maximizes their income net of citizenship ascension cost given their human capital stock. DeVoretz and Ma (2002) imbedded the citizenship 12 Since the available micro data file represented a 2.7% censored sample of the 2001 Census of Canada, we were able to identify a limited number of source countries. the identified oeCD countries include France, germany, greece, italy, the netherlands, Por-tugal, Spain, the United kingdom, other Western europe, northern europe and the United States. our sampled non-oeCD origins include Arab-African origins, Latin America, China (PrC), india, Latin America, Lebanon, the Philippines, Poland, the USSr (european part), Vietnam, and yugoslavia.

oF CAnADiAn CitizenSHiP ASCenSion

decision inside a more general model of moving and staying. each stage of this journey involves a decision to move or stay, and this decision is, in turn, conditioned by possible ascension to citizenship.

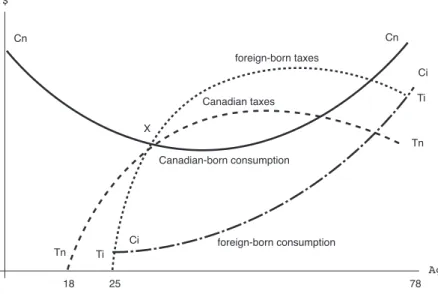

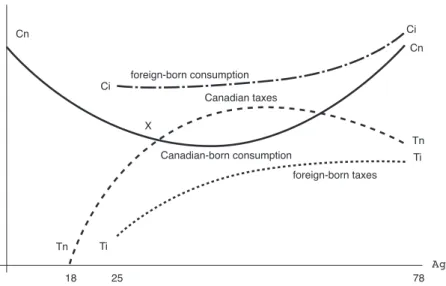

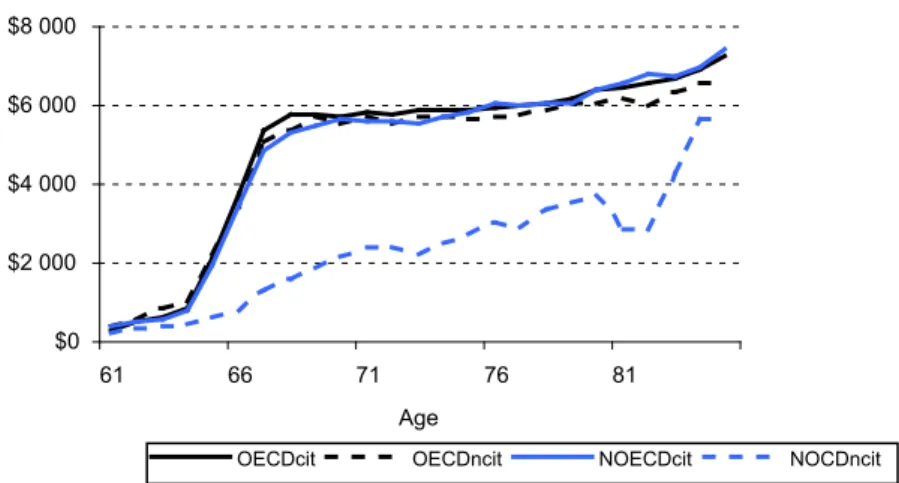

Figure 3. Immigration triangle

to highlight the citizenship decision, we focus on the movement path between the Sender country A and the entrepot country (B or Canada). initially, the immigrant resides in country A and decides to move to country B. this movement is asserted to be motivated by the prospect of higher earnings and the opportunity to acquire subsidized human capital and two public goods including a passport and citizenship.

Both the acquisition of subsidized human capital and the prospect of receiving public goods (citizenship and a passport) now increase the proba-bility that this immigrant will ascend to citizenship, if the expected ear-nings stream in country B net of costs of citizenship acquisition exceeds the option of returning home. However, if country A does not recognize dual citizenship, this will raise the cost of possible return migration and reduce the probability of ascending to citizenship in country B.13 But will the newly ascended citizen of country B stay in country B? only if the net income 13 given the lack of dual citizenship, one apparent strategy for Chinese immigrants is for one of the two spouses to ascend to Canadian citizenship, while the other spouse remains Chinese. this ensures access to China for the spouse who is not a Canadian citizen.

eNtrepOt

Country BSeNDer

Country A Country C

rOW

Human Capital triangle

32

gains from staying as a citizen in country B exceed the income gains from a citizen of country B moving to country C in the rest of the world (roW) will the immigrant remain in country B. if the cost of movement to country C is lowered via the attainment of citizenship and a passport in country B and the income in country C exceeds that earned in country B, the natura-lized citizen of country B will move and become a citizen of country C. in sum, the optimization problem for the immigrant is to choose a mobility path and citizenship status in one or more of the destinations which maxi-mizes net income given his/her human capital endowment, and the transac-tion costs of movement and obtaining citizenship.

the array of costs implied by citizenship acquisition differs by country of origin and the individual immigrant. First, in the absence of mutual recognition of dual citizenship by both Canada and the sending country, the major cost of ascending to Canadian citizenship is the loss of home country citizenship. this loss in turn implies limited access to the home country’s labour market and loss of public services including social insu-rance and subsidized education. in addition, application fees and any fore-gone income arising from continued residence in Canada to fulfill citizen-ship residency requirements add to the costs of ascending to Canadian citizenship.

on the other hand, the benefits derived from Canadian citizenship include possible greater job access and any wage premium paid by private and public Canadian employers to citizens, potential access to the United States labour market with a nAFtA visa, and possible visa wavers by third countries given a Canadian passport.

given these observations and our economic model, we argue that rates of ascension to citizenship will be a positive function of the immigrant’s various demographic and socio-economic characteristics that affect mone-tary or non-monemone-tary benefits associated with Canadian citizenship. For example, the immigrant’s age determines his/her remaining years in the Canadian labour force and thus the size of any lifetime premium associated with citizenship. Consequently the older the immigrant is at immigration, the less likely he/she will become a citizen given the shorter payoff period. Similarly, with a greater level of educational attainment, an immigrant will potentially reap more income from citizenship and hence may have a greater propensity to acquire citizenship.

Successful economic integration as indicated by the immigrant’s income, occupation and home ownership status increases the benefits of remaining in Canada and adds to the cost of moving back to the immigrant’s country of origin. the degree of cultural assimilation, which could be proxied by years since immigration, is expected to demonstrate a strong

oF CAnADiAn CitizenSHiP ASCenSion

positive effect on citizenship acquisition rates. Correspondingly, immi-grants who have lived in Canada for a long period will have a lower opp-ortunity cost when acquiring citizenship since they are less likely to suc-cessfully re-integrate into their home country labour market. Moreover, living in an urban environment with a greater concentration of immigrants and having better access to labour market information can make a diffe-rence to an immigrant’s perception of the benefits derived from citizenship and raise the odds of citizenship acquisition. gender may play a role in the naturalization decision as well. yang (1994) suggested that men have a greater inclination to seek citizenship than women since they are more likely to seek jobs where citizenship may be an advantage.

Costs and benefits of acquiring Canadian citizenship are also affected by the institutional environments in both the sending and receiving countries. on the one hand, the recognition of dual citizenship by the home country plays an important role in an immigrant’s decision to naturalize. in cases where dual citizenship is not recognized by the sending country the costs of Canadian citizenship acquisition rise and the odds of citizenship acquisition are reduced. on the other hand, changes in Canada’s immigra-tion legislaimmigra-tion may introduce a period effect that will influence rates of naturalization. in particular, the 1976 Citizenship and immigration Act relaxed entry requirements for immigrants from developing countries and this will possibly affect citizenship acquisition rates during the post-1980 period. these developing countries are all characterized by low opportu-nity costs derived from acquiring Canadian citizenship. to capture this implied differential costs for citizenship acquisition by level of develop-ment, we will divide our sample into oeCD and non-oeCD immigrant source regions.

thus, the immigrant’s demographic and human capital characteristics, plus both Canada’s and source country’s socio-economic contexts all will be incorporated in an economic model of citizenship acquisition. 14

the above arguments lead us to a specification of an ascension model in a logistic function form or where is a probability of observing a citizen in our immigrant sample conditioned on vector of explanatory variables . these variables include individual attri-butes and the socio-economic context variables discussed earlier which may influence the naturalization decision. the vector of parameters is esti-mated by the Maximum Likelihood Method.

14 one outstanding modeling problem must be noted. it is quite possible that the deci-sion to become a citizen and the resulting rise in earnings may be jointly determined. in other words, does citizenship lead to greater earnings, or do higher earnings give a greater incentive to become a citizen? We will address this issue and its possible resolution in the next section of the paper.

) exp( 1 ) exp( ) | 1 ( � � i i i i X XX Y P + = = P(Yi=1|Xi) i X

34

Since we also feel that citizenship may vary by gender, we further dis-aggregate our results by gender. in table 2 we report the results for our model of citizenship ascension for a sample drawn from all the immigrant-sending countries as listed above. the maximum likelihood estimates of the logistic model yield a curvilinear relationship between age and naturali-zation rate. the fact is that the rate of ascension is increasing in age but, at decreasing rate, is consistent with our human capital view on the naturali-zation decision. in other words, the younger in age at naturalinaturali-zation, the greater lifetime benefits an immigrant can expect to accrue from the new citizenship status.

table 2. Model of probability of acquiring Canadian citizenship: immigrants from all countries

Coeff. b/St.Er. P[|Z|>z] Mean of X Elasticity Constant 0.019187 0.164 0.8699 AgeP 0.007346 1.399 0.1617 45.88071 0.055009 AgeSQ -0.00011 -1.843 0.0654 2222.033 -0.03937 ySiM 0.080457 74.192 0 24.54317 0.322278 yiPoSt75 0.01155 0.295 0.7682 0.347505 0.000654 P75_ySiM 0.021916 9.573 0 4.296566 0.015368 tyS -0.00023 -7.85 0 -57.6105 0.002147 FeMALe -0.10292 -7.272 0 0.510275 -0.00857 Pro 0.279808 14.964 0 0.220901 0.00957 SkL 0.1378 7.978 0 0.244092 0.005361 LntinC 0.00012 4.106 0 -42.07 -0.00082 HoWn 0.192035 12.01 0 0.777668 0.02526 DUAL -0.19443 -9.606 0 0.601698 -0.01885 CMA 0.211616 11.696 0 0.834479 0.030215 oeCD -1.25681 -52.936 0 0.647082 -0.11868 number of

observations 154458 Log likelihood function -68474.07 Chi squared 15186.62 restricted log likelihood -76067.38 note: Logistic regression: dependent variable Ctzn

oF CAnADiAn CitizenSHiP ASCenSion

in table 2 for male immigrants most of the life-cycle variables obtain the predicted sign and are significant. the effect of the income variable (LnWDiF) that measures the predicted logarithmic differences of citizen versus non-citizens wages is relatively small and negative.15 years since immigration (ySM) positively and significantly influenced the log odds of ascending to citizenship. As we expected, the period dummy (yiPoSt75) which reflects a change in Canada’s immigrant source regions had a posi-tive but statistically insignificant effect on naturalization rates. in addition, we tested for the possible effect of the 1977 citizenship law on the speed of naturalization by using an interaction variable. A positive and statistically significant coefficient on P75_ySM suggests that years since immigration became a more important factor in determining naturalization after the amended changes to Canadian Citizenship act.

Contrary to our expectations the immigrant’s total years of schooling (tyS) had a small and negatively signed effect on the immigrant’s propen-sity to naturalize. the significantly negative coefficient for the gender dummy (FeMALe) suggests that males are more likely to ascend to Cana-dian citizenship which supports yang’s (1994) findings.

our estimates also illustrate the role of economic assimilation in the naturalization decision. Home ownership (HoWn) and the logarithm of total income (LntinC) are significant conditioners and yield the predicted positive signs. Also, a higher occupational status (Pro, SkL) yields a strong positive relationship with the rate of naturalization.

the characteristic of Canada’s socio-economic context, the Census metropolitan area indicator (CMA), is strong and positively signed which supports the idea that living in urban environment fosters immigrant natu-ralization. the significant negative coefficient for the oeCD dummy indi-cates that the immigrant’s source country level of development is an important determinant of citizenship ascension. Contrary to our expecta-tions the coefficient on the dual citizenship dummy (DUAL) which indica-tes the effect of source country citizenship regime on immigrant’s naturali-zation decision is strongly negative. this result could be explained by our data limitations. our available list of the source countries in the oeCD group (except germany and greece) includes only countries with dual citi-zenship regime, whereas in non-oeCD group only Poland recognizes dual 15 For non-citizens this variable is calculated as

€

LNWDIFi= ˆ β CXi− LNWAGEi , for citizens

€

LNWDIFi= LNWAGEi− ˆ β NCXi ; where LnWAgei – logarithm of individual’s annual wage

earnings, Xi – vector of individual’s characteristics,

€ ˆ β NC and

€ ˆ

β C are vectors of oLS

coef-ficients estimated from log-linear earnings equations for non-citizens and citizens respec-tively. this variable equals the mean income difference between a 25-year old immigrant with and without Canadian citizenship, from the particular country of origin, for the sampled observation. Figures 7 and 8 illustrate how this was computed.

36

citizenship. thus, the DUAL dummy variable essentially becomes an indi-cator of the level of development.16

Wage equation

DeVoretz and Pivnenko (2004) have already demonstrated that a signifi-cantly positive earnings effect derives from ascension to Canadian citizen-ship. in addition, they acknowledged the possibility that reverse causality can occur if the higher earnings observed among naturalized citizens influ-ence the immigrant’s decision to acquire Canadian citizenship.17 in other words, citizenship status (C), and the natural logarithm of citizen and non- citizen gross annual wages may be determined simultaneously. thus, citi-zenship status may also be a function of the expected citizen/non-citizen wage differential, since immigrants may incorporate the potential wage premium associated with citizenship status in their decision to become citi-zens. Following Heckman (1976) and Lee (1978) we estimate the outlined empirical model in order to account for this potential selection bias and the implied simultaneity: € Ci= α0+ α1Xi+ α2Yi+ α3LW ˆ D IFi+ εi (1) € lnWi= β0+ β1Xi+ β2Zi+ β3λi+ νi, if C i =1 (2) € lnWi= γ0+ γ1Xi+ γ2Zi+ γ3λi+ τi , if C i =0 (3) where

Ci – binary variable indicating the immigrant’s choice of citizenship status (1- citizen, 0- non-citizen);

Xi – vector to represent the immigrant’s human capital characteristics; yi – other determinants of citizenship status;

zi – control variables in wage equation (such as occupational choice and weeks worked). € λi= φ( ˆ C i*) Φ( ˆ C i*) if Ci =1, or € λi= −φ( ˆ C i*)

(1− Φ( ˆ C i*)) if Ci =0 – selectivity variable (inverse Mill’s ratios for citizens and non-citizens respectively).

16 We believe that by using the 20% uncensored census samples the results will improve as they did for Bloemraad (2002).

17 robinson and tomes (1982) were the first to apply the Heckman correction in the migration context.

oF CAnADiAn CitizenSHiP ASCenSion

€

LW ˆ D IFi - simulated citizen-non-citizen wage differential which equals the

difference between the logarithms of: i) observed and opportunity wages

€

lnWi−(ˆ γ 0+ˆ γ 1Xi+ˆ γ 2Zi+ˆ γ 3λi)

for citizens, or

ii) opportunity and observed wages

€

( ˆ β 0+ ˆ β 1Xi+ ˆ β 2Zi+ ˆ β 3λi) − lnWi

for non-citizens 18.

in the first stage the selection equation is estimated by a maximum likelihood technique as an independent ProBit model to determine the decision to acquire Canadian citizenship. A vector of inverse Mills ratios (iMrs), estimated expected error, is then generated from the parameter estimates of the selection equation. the citizen’s wage is observed only when the selection equation equals 1 (i.e., an immigrant acquires citizen-ship) and its logarithm is then regressed on the explanatory variables and the vector of iMrs from the selection equation by ordinary least squares (oLS) method. Similarly we obtain oLS coefficients in the non-citizen wage equation. Hence, in the second stage we rerun the regression with the estimated expected error included as an extra explanatory variable, remo-ving the part of the error term correlated with the explanatory variable, and thus avoiding the suspected selection bias.

in order to generate the iMrs we use the reduced form of equation (1) that excludes wage differentials for the citizen/non-citizen workers. then we incorporate the estimated lambdas (or iMrs) into wage equations (2) and (3) and run an oLS procedure to estimate the selection bias corrected regressions coefficients. next, we use the estimated coefficients for citizens (non-citizens) to forecast the opportunity wages for non-citizens (citizens). Finally, we estimate a ProBit equation (1) using the simulated citizen/ non-citizen wage differentials.

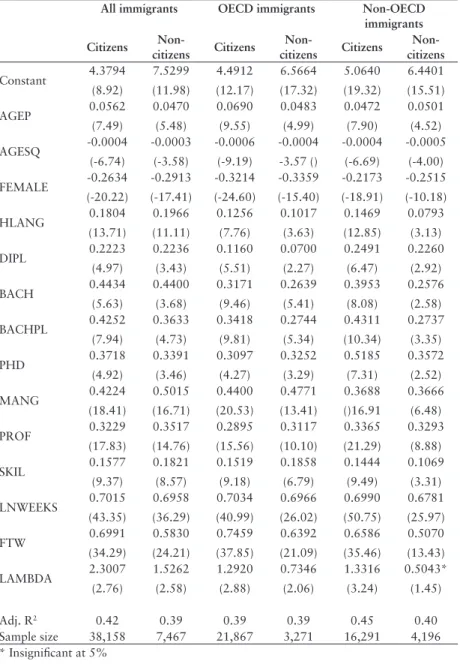

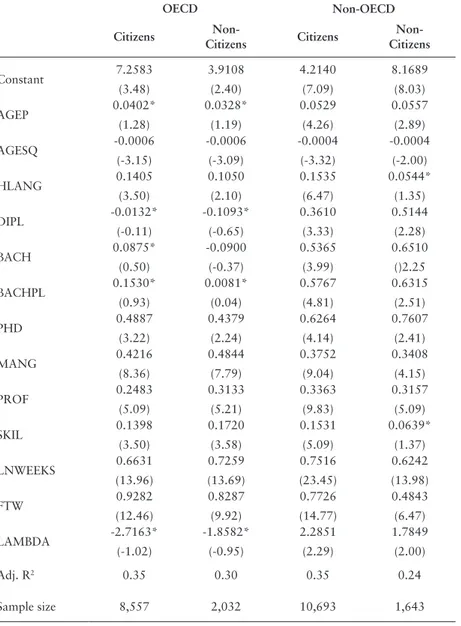

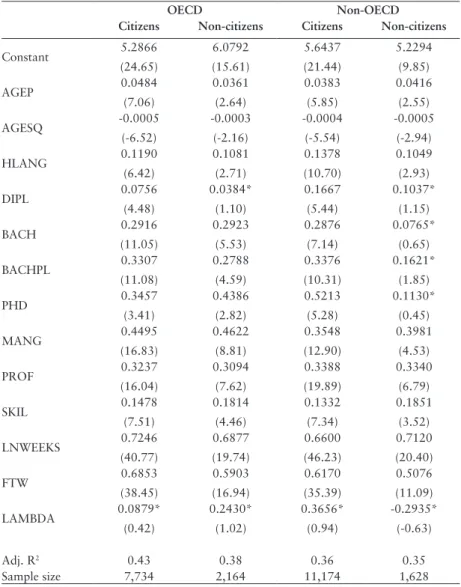

the results for the earnings equations are presented in table 2. At this point we must keep in mind that some of the model’s estimated coefficients do not lend themselves to a straightforward interpretation. if a variable appears only in the wage equation, its coefficient can be simply interpreted as the marginal effect of a one-unit change in the variable that appears in this one equation. if, on the other hand, the variable appears in both the selection and wage equations, the coefficient in the outcome equation is affected by its presence in the selection equation as well. table 3 shows the estimated coefficients derived from the earnings equations, implying that the indirect effects of age and education on the logarithm of wages are not shown in this table.

18 Here we rationalize our assumption that immigrants form their citizenship premium expectations based on the observed performances of their counterparts with similar back-ground but opposite citizenship status.