J

Ö N K Ö P I N GI

N T E R N A T I O N A LB

U S I N E S SS

C H O O L JÖNKÖPING UNIVERSITYC u s t o m e r T r i a l o f S e l f - S e r v i c e Te c h n o l o g y

An investigation of vending machines for non-prescription drugs

Bachelor Thesis within Business Administration

Author:

Chau Nguyen Vu Bao

Diane Mpambara

Tutor:

Dijana Rubil

Jönköping June 2011

Acknowledgements

The researchers of this study would like to acknowledge the following persons for their supervision and help through the process of this research.

We would like to thank our tutor Dijana Rubil for her support, helpful opinions and discussions and her great courage.

The researchers would as well like to thank the GreenCross manager Mr. Tony Lölholm who provided us with relevant information which increased our knowledge about the company, the professors at Jönköping International Business School for their assistance and advice throughout the research and all the students at Stockholm University who participated in the survey.

Researchers also deeply thank their family members’ and friends who have been supportive, helpful and encouraging.

Finally, we would like to thank the students who will read this thesis for their feedback.

Bachelor Thesis in Business Administration

Title: Authors: Tutor: Date: Subject term:Customer Trial of Self-Service Technology

An investigation of vending machines for non-prescription drugs Chau Nguyen Vu Bao, Diane Mpambara

Dijana Rubil 2011-05-30

Customer trial, self-service technology, vending machine, consumer pre-purchase behavior

Abstract

Background In the context of the deregulation in the pharmaceutical industry in Sweden, many new business chances have been created. The rising numbers of players in the market started up the race for gaining market shares and attracting customers with new products and services. One of the new players, GreenCross AB, introduced MiniApotek, a vending machine of non-prescription medicine, to the Swedish market. The business concept is to provide a new, secured and convenient way of buying non-prescription medicine to the Swedish society. However, there is a gap between the retailer‟s business expectation and the customers‟ perception of this new service.

Purpose The purpose of this thesis is to investigation the different factors that affect potential customers‟ trial behavior of self-service technology. Specifically, the researchers explore and examine the main factors that directly manipulate customers‟ trial at MiniApotek.

Method A quantitative approach is applied in this thesis to identify the key factors and explain their strong influence to trial. The empirical data collected from conducting a survey at Stockholm University, was combined with e-mail communication with GreenCross AB. These materials were analyzed in accordance with the three applied theories, the product concept, pre-purchase stage in consumers‟ decision making process and model of customers‟ trial of self-service technologies.

Conclusion The researchers conclude that there is a strong influence of inertia, need for personal interaction, technology anxiety and perceived risk on the trial of potential customers at MiniApotek. It is found that these factors have a negative effect on the adoption process of MiniApotek in Swedish market. Consequently, the authors think GreenCross AB needs to get a better understanding of the real market need and take these factors into great consideration, as well as find a better strategy to improve the company‟s business situation.

Table of Contents

1

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 2

1.1.1 The biggest change in forty years ... 2

1.1.2 GreenCross AB and its MiniApotek ... 2

1.1.3 Vending retail industry ... 4

1.2 Problem ... 5 1.3 Purpose ... 6 1.4 Perspectives ... 6 1.5 Delimitations ... 6 1.6 Definition ... 6

2

Theoretical Framework ... 7

2.1 Five stages of the product lifecycle ... 7

2.1.1 Classification of products ... 9

2.2 Pre-purchase phases ... 9

2.2.1 Classification of consumers ... 11

2.3 Self-Service Technology ... 13

2.4 Key factors influencing the trial of potential customers ... 14

2.4.1 Role clarity ... 17 2.4.2 Ability ... 19 2.4.3 Motivation ... 20

3

Method ... 22

3.1 Research Approach ... 22 3.2 Research Strategy ... 223.3 Quantitative versus Qualitative ... 22

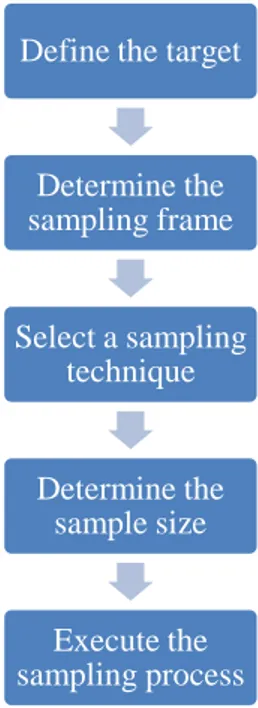

3.4 Data sampling collection ... 23

3.4.1 Sample collection ... 23 3.5 Pilot test ... 25 3.6 Survey ... 25 3.6.1 Scale of measurement ... 26 3.6.2 Translation... 27 3.6.3 Coding ... 27

3.7 Approach to survey analysis ... 27

3.7.1 Inferential Statistics ... 27 3.7.2 One-sample T-test ... 28 3.7.3 Correlation... 30 3.7.4 Multiple regression... 30 3.8 Research Quality ... 31 3.8.1 Validity ... 31

3.8.2 Reliability ... 32

3.8.3 Generalizability ... 33

4

Empirical Results and Analysis ... 34

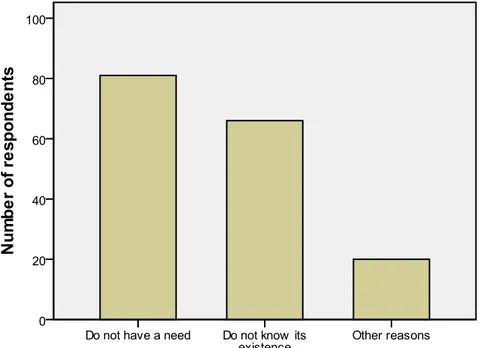

4.1 Survey results ... 34

4.1.1 Public notice to MiniApotek ... 34

4.1.2 Potential users‟ willingness to try MiniApotek ... 36

4.2 Statistical Analysis ... 37

4.2.1 Role clarity ... 37

4.2.2 Ability ... 43

4.2.3 Motivation ... 47

5

Discussion ... 54

5.1 Critique of the study ... 54

5.2 Recommendation for future researches ... 54

6

Conclusion ... 56

References ... 58

Appendix A

Communication with GreenCross AB ... 64

Appendix B

Customer Survey of Miniapotek ... 67

Usage Instruction of MiniApotek ... 70

Appendix C

Codebook for Analysis ... 71

Appendix D

Analysis and Interpretation for the factors creating Role

Clarity and their effects to Trial ... 73

Appendix E

Analysis and Interpretation for the factors influencing

Ability and their effects to Trial ... 82

Appendix F

Analysis and Interpretation for the factors influencing

Motivation and their effects to Trial ... 87

Table of Figures

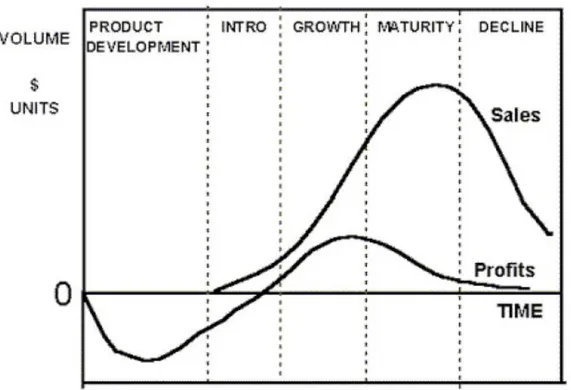

Figure 2.1 Product life cycle ... 7

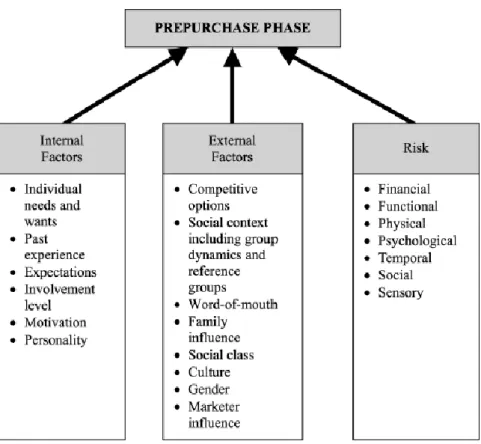

Figure 2.2 Components of the pre-purchase phase ... 11

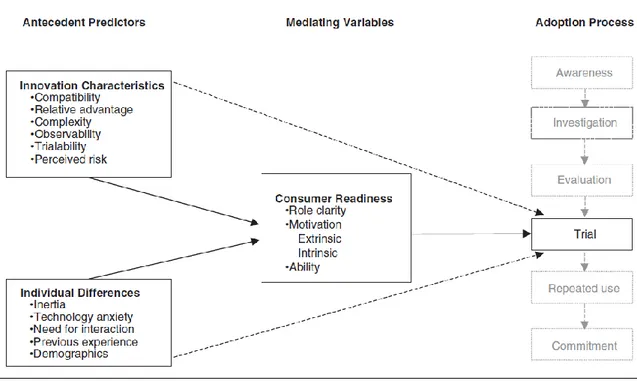

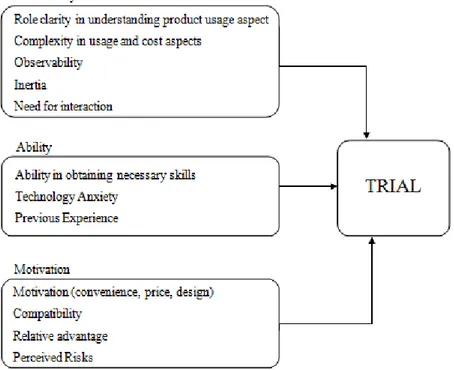

Figure 2.3 Key predictors of customer trial of self-service technologies developed by Meuter, Ostrom, Roundtree and Bitner ... 14

Figure 2.4 Key factors influencing trial of self-service technologies ... 16

Figure 3.1 Data sampling collection ... 23

Figure 4.1 Percentage of respondents which already used MiniApotek ... 34

Figure 4.2 Percentage of respondents which know about MiniApotek ... 34

Figure 4.3 Main reasons why respondents do not use MiniApotek ... 35

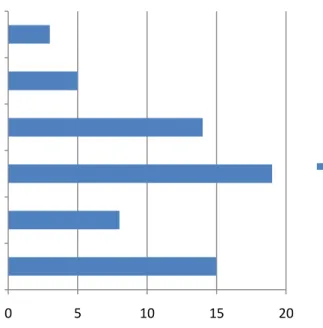

Figure 4.4 Other reasons why respondents do not use MiniApotek ... 36

Figure 4.5 The frequency of potential customers responding to the willingness to try MiniApotek ... 36

Figure 4.6 Line chart for level of customers‟ understanding product usage ... 37

Figure 4.7 Line chart for customers‟ perception of complexity in usage & cost ... 38

Figure 4.8 Line chart for customers‟ need of observation ... 39

Figure 4.9 Line chart for customers‟ purchasing habit at Apoteket stores ... 39

Figure 4.10 Line chart for customers‟ need of personal interaction ... 40

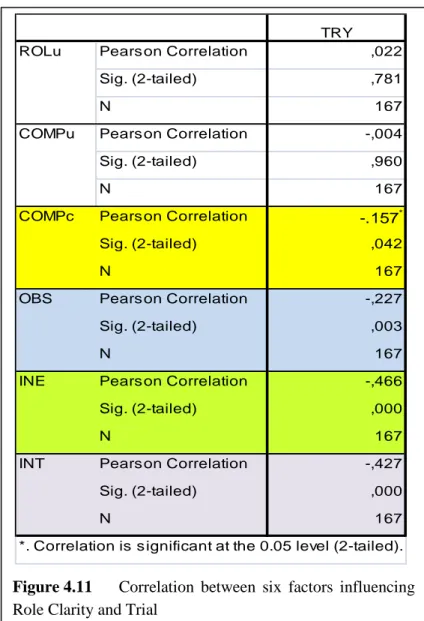

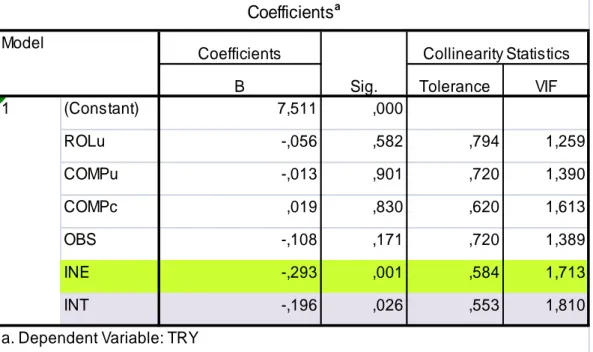

Figure 4.11 Correlation between factors influencing Role Clarity and Trial ... 41

Figure 4.12 Coefficients in multiple regression between independent variables influencing Role Clarity and dependent variable Trial ... 42

Figure 4.13 Line chart for customers‟ capability ... 43

Figure 4.14 Line chart for level of technology anxiety ... 44

Figure 4.15 Line chart for consumers‟ usage experience of other SSTs ... 44

Figure 4.16 Correlation between factors influencing Ability and Trial ... 45

Figure 4.17 Coefficients in multiple regression between independent variables influencing Ability and dependent variable Trial ... 46

Figure 4.18 Line chart for customers‟ perception in convenience aspect ... 47

Figure 4.19 Line chart for customers‟ perception in price aspect ... 48

Figure 4.20 Line chart for customers‟ perception in design aspect ... 48

Figure 4.21 Line chart for customers‟ perception of compatibility ... 48

Figure 4.22 Line chart for customers‟ perception in time-saving aspect ... 49

Figure 4.24 Line chart for customers‟ perception on selling quantity ... 49 Figure 4.25 Line chart for customers‟ perception of perceived risk when buying medicine

... 50 Figure 4.26 Line chart for customers‟ perception of perceived risk when buying

non-prescription drugs at MiniApotek ... 50 Figure 4.27 Correlation between factors influencing Motivation and Trial ... 51 Figure 4.28 Coefficients in multiple regression between independent variables influencing

1

Introduction

The content of a YouTube video uploaded by Reason TV called “Sweden: A Supermodel for America?” is not about the modelling industry in Sweden; in contrast, it highlights a more vital aspect, the Swedish socio-economic model (YouTube, 2009). The video message stresses the strong influence of “social democracy”, a model of a democratic country following a socialist path. The governing model has been associated with monopoly policy in many business fields and generated a generous welfare state and a high standard of living for every citizen in Sweden. It might be the reason why in his strategy to deal with the American financial crisis, Barack Obama proposed “… what he calls the “Swedish model”. In the early 1990s, Sweden

nationalizes its banking sector then auctioned banks having cleaned up balance sheets” (Luce &

Guha, 2009). However, it is undeniable that the overloading situation appears in some industries, especially within the healthcare system. Sweden, along with Cuba and North Korea are the only three countries left all over the world which keep pharmacy monopoly (Öhlén, July 2009). On the average, there are 10,000 Swedish inhabitants per pharmacy store and even 20,000 persons per pharmacy store in some big cities were statistically recorded by Swedish Pharmaceutical Association (Andersson, Brodin & Nilsson, 2002). The huge burden of labor and facilities in pharmaceutical service had weighed down on Sweden.

A new chapter began in the history of Sweden when the Moderate Party came to power after elections in September 2006, putting an end to the 10-year rule of the Social Democratic Party (BBC, 2011). The new government began to carry out an ambitious campaign of liberal economic reforms starting in 2008. “State pensions, schools, healthcare, public transport, and

post offices have been fully or partly privatized … making Sweden one of the most free market oriented economies in the world” (Nylander, 2009).

Having witnessed the market need in the pharmaceutical field, the new government passed a bill that would deregulate the pharmacy industry in Sweden on 20 February 2009. The background clarifies about the deregulation in Sweden pharmacy, leading to the birth of many new business chances.

1.1

Background

This section will describe the context in which the deregulation of the Swedish pharmaceutical market was taken into effect. It also provides some general information about the vending industry and GreenCross AB.

1.1.1 The biggest change in forty years

Carin Svesson, the President of the Swedish Pharmaceutical Association, once notified the abolishment of pharmacy monopoly that would end the authority of Sweden‟s stated-owned pharmaceutical industry for 38 years (Pharmacy News, 2009). On February 20, 2009, the Swedish Parliament (Riksdagen) decided that the monopoly in Swedish pharmacy market would be eliminated (Regeringskansliet, 2009a). In the press release on February 23rd, 2009, the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs confirmed that the new passing bill would “give more

actors the chance to contribute to a safe, accessible and customer-oriented supply of pharmaceutical products” (Regeringskansliet, 2009b).

The deregulation makes it possible for both retailers and consumers to exercise freedom. For the retailers, the aim of the reform is to enhance the competition for all players in the market. Retailers get the chance to start private businesses within the pharmaceutical market as well as to experience competition within the same market. For Swedish customers nationwide, the effect of the passing bill decreases pharmaceutical prices as well as increases the availability and service effect of pharmaceuticals. Specifically, Swedish consumers gain the ability to choose among different range of products as well as receive better service through extended opening hours and accessibility (Regeringskansliet, 2009b).

The deregulation has truly established evolutional business marketing and methods in the Swedish pharmaceutical market. Since November 2009, the Swedish Government had sold off 650 of the country‟s pharmacies to small companies to create wider choices for consumers and 250 pharmacy shops remain state-owned (Pharmacy News, 2009). Government Offices (Regeringskansliet, 2009a) informed that those who would like to conduct retail trade in non-prescription pharmaceutical products must obtain a licence from the Medical Product Agency. Even though it does not keep exclusive rights to conduct retail trade in certain medical products, Apoteket AB still remains competitive in the market.

It was witnessed that there has been many changes in the Swedish pharmaceutical market with new entrants joining. “The number of pharmacies increased during 2010 by around 15 percent,

equivalent to 150 new pharmacies opening” (Marlow, 2009). Kronans Droghandel AB is

planning to open 171 stores (Pharmacy News, 2009). A supermarket chain such as ICA AB has already invested its own Cura Apoteket in its 32 supermarkets (ICA webpage, 2011). In an effort to catch business opportunities, GreenCross Industri AB has introduced vending machines of non-prescription medicine, called MiniApotek, to the Swedish market. (“MiniApotek” will be used throughout this paper instead of vending machine of non-prescription medicine).

1.1.2 GreenCross AB and its MiniApotek

GreenCross AB introduced the vending machines of non-prescription drugs, called MiniApotek to the Swedish public in May 2010. The company‟s optimal plan is to generate accessibility and

convenience of MiniApotek‟s services around 200 public locations in Sweden so that the customers can access the machines easily. At the present time, the machines can be found in Stockholm, Linköping, Örnsköldsvik and Nyköping (GreenCross webpage, 2011). It is undeniable that GreenCross has been dipped hard in this business chance “with 5 million SEK

investments in the vending machine and human resources. Since September 2010, GreenCross has tried to set up 20-25 vending machines per month” (From Dagens Industri, 2010).

It is promoted that the vending machines offer a convenient, easy and secure way for customers to access and buy prescribed medicines (Appendix A). MiniApotek provides fifteen non-prescribed medicines such as fever and pain killers, nasal sprays, smoking preventing medicine, sore throat relievers, gastrointestinal medicine, condoms and tampons. The machines are placed in public places such as railways, underground stations, ferry terminals, airports, shopping centers, fairs, universities and hotels (GreenCross webpage, 2011). Purchases can only be made by credit card with pin code. The customer selects the products and reads the product information through a digital screen. Age credit (18 years) and volume are controlled by a central system linked to the external database and if all information displayed is correct the customer will receive the medicine (GreenCross webpage, 2011).

Communication with GreenCross AB

Due to the heavy workload and busy schedules at GreenCross AB, we could only contact the company by e-mail. Mr. Tony Lölholm, who is in charge of sales and marketing activities, provided us with the information of services as well as company‟s business orientation (See

Appendix A). However, three important issues from the communication by e-mail were noticed.

Firstly, for the MiniApotek service, the business idea originated from the owners of GreenCross AB and was generated by the deregulation in the Swedish pharmaceutical market (See Appendix

A). Therefore there is a risk that it might have not been based on an official market research,

which would capture the real market demand. GreenCross AB has not conducted any customer survey on the business since they launched the first MiniApotek in May 2010 in Sweden. Additionally, GreenCross AB has also faced great challenges in launching MiniApotek. Due to insufficient funds, it has been difficult to invest in large volumes of MiniApotek in Sweden. Hence the limited launching scale of MiniApotek constitutes the second issue that was observed. Only 17 machines have been launched mostly in Stockholm and only three of them are at universities that are Stockholm University, Södertörn University and Linköping University (See

Appendix A). The third matter relates to the way GreenCross AB promotes MiniApotek. The

company targets the central place at a spot and lets MiniApotek automatically introduce and promote itself. GreenCross AB claims that MiniApotek can gain public attention through the design and catchy images on machines‟ touch-screens (See Appendix A). Besides, the company made a big headline in Dagens Industri at the launch of the first machine and uses some tools such as apps and social media.

According to GreenCross AB, MiniApotek is seen as „a unique presence‟ on the market; however, it could be a different scenario captured from consumers‟ perspectives.

1.1.3 Vending retail industry

The vending industry dates back to 215 B.C when Greek historian Hero witnessed a device, which was used in Egyptian temples, to deliver an amount of holy water upon the deposit of some coins. At the present time, this industry „provides a quality product, 24 hours a day, seven

days a week, helping consumers to better manage their busy lifestyles‟ (Lee & College, 2003).

Vending machines are typically positioned outdoors and in some indoor places such as in the corners of factories and offices, large retail stores, gasoline stations, railroad stations, hotels, restaurant, airports, bookstores, and shopping malls (Lee & College, 2003).

Advantages

Vending machines offer services for marketers as well as for consumers. In the case of marketers, the vending machines contribute to the normal distribution channels and allow marketers to gain and strengthen their retail distribution network (Lee & College, 2003). Their compressed size gives them the advantage to fit into many places which is not the case for the full-sized convenience stores. Phillips (1992) argues that vending machines help consumers to recognize products‟ brands and adopt them in a long term. Vending machines assist to the reinforcement of the brand and the product image becomes visible to wider publicity in the marketing communication (Lee & College, 2003). According to NAMA (2003), margins gained from sales made in vending machines are greater than for those in usual retail stores; for example, in Almanac of Business Industrial Financial Ratios 2000-2003, the margin profit gained up to 3.8 percent before tax while margin of grocery stores modestly stood at 1.3 percent (cited in Lee & College, 2003)

In the case of consumers, vending machines are mostly appreciated by consumers for their convenience and time saving advantage (Quelch & Takeuchi, 1981). They provide consumers immediate transactions without middleman intervention; just press what you “see and want” and receive the product immediately with instantaneous fulfillment (Lee & College, 2003). The 24-hour accessibility to the fresh and ready-to-consume products is another significant value of vending machines (Kotler, 2003). These transactional features in particular make vending machines attractive for the products that are requested all the day long, that are of spontaneous demand, that do not necessitate sales assistance or need a closer investigation before purchase, and that can be sold for relatively small amounts of money (Lee & College, 2003).

Disadvantages

However, Lee and College (2003) also notify the inbuilt disadvantages of vending machine services which may unfavorably affect consumers purchasing‟ experiences and the vending industry in the long term. The first matter is related to the lack of interpersonal contact between retailer and consumers. The very nature of non personal, no human contact dealings can generate problems that potentially affect consumers (Lee & College, 2003). Most consumers would rather make their shopping in stores than purchase from vending machines. They also choose to have a personal contact before making a purchase (Trachtenberg, 1994). A number of consumers are still not content with the absence of human contact when conducting vending machines transactions (Leaner, 2002). The second issue points out consumers‟ lack of trust to the transactions of vending machines. Contrasting its retail store equivalents, the machines

themselves cannot mutually grant to consumers the services that follow a transaction and it only distribute the product in return for payment. When consumers are not satisfied with their purchase, there is no way they can get their money back or if there is a way, it is not as convenient as at a regular retail store (Lee & College, 2003). The next disadvantage is the bad location of the machines. Vending machines transactions take place in neglected and detached surroundings such as street corners in a big city or by a pitiful little motel and this make consumers feel unsafe (Lee & College, 2003).

1.2

Problem

The vision of GreenCross AB is to reach customers and provide medicine for them by the MiniApotek service. The objective of Greencross is to capture one percent of the Swedish market for non-prescription medicine, which is worth 3.5 billion Swedish kronor per year (GreenCross webpage, 2011). This move represents a viable and profitable business opportunity in this time of technological advancement and especially with the deregulation of the Swedish pharmaceutical market. However, this also represents a new way for consumers to purchase medicine and there is the possibility that they may feel a bit skeptical about using these machines.

Prior to this research, a pilot observation regarding customer reaction towards the MiniApotek was conducted in one week. The two different MiniApoteks were chosen in two different locations, one at Sergelstorg shopping mall in central Stockholm and another at Stockholm University. After reaching Stockholm, the researchers spent eight hours standing next to the machines to closely observe how customers perceive the MiniApotek. The result did not give positive signals for business transactions. Within a week, only two persons used the vending machine at Sergelstorg shopping mall and nobody approached the machine at Stockholm University. From this observation it was realized that consumers do not use the machines. It is apparent that while GreenCross is planning to penetrate Swedish market of non-prescription medicine, the customers do not seem to use or recognize MiniApotek. It was from this observation that the need for an in-depth investigation into the reasons why most consumers do not use the MiniApotek was raised. While the subject of customer perception and usage of vending machines of other consuming goods (i.e. foods, beverages) have been studied by different researchers in the past (Walley & Amin, 1994; Wiecha et al., 2006), the issue of consumer reaction with regards to the vending machine in pharmaceutical industry has not been studied before. Hence, it is imperative to explore the area in order to provide consumers‟ real perception of the vending business to GreenCross AB and other service providers, particularly in the Swedish pharmaceutical market of non-prescription medicine.

1.3

Purpose

The purpose of this study is to investigate the different factors that result in the low consumption of non-prescription drugs offered by MiniApotek.

The purpose refers to the following research question:

What are the contributing factors that cause customers not to use the MiniApotek?

1.4

Perspectives

Since the problem studied in this research is about the customers‟ attitude toward self-service technology, i.e. in this case, MiniApotek, it is appropriate to mention that the researchers directed the study toward the customers‟ perspective.

1.5

Delimitations

Since there are few MiniApoteks in Stockholm city, researchers in this paper decided to focus on the one and only MiniApotek located at the university‟s premises. The target group for the study is students at Stockholm University who are non-users of the MiniApotek.

1.6

Definition

MiniApotek: the name of vending machine of non-prescription medicine supplied by GreenCross

AB.

Deregulation: refers to the process of renewing or abolishing government rules and controls

from some types of business activity (Longman, 2011).

Vending machine: refers to an automatic device that can provide a number of different products.

The applied business idea is to serve product automatically and fast without the help of cashier. (Vending machine suppliers, 2011).

Self-service technology: are interfaces which help customers conduct a service by themselves

2

Theoretical Framework

Due to the fact that the machines are newly launched on the market and offer non-prescription medicines, it is vital to explain the product concept in part 2.1, which consists of the product life cycle and product categories, in order to give a better understanding about how the vending machines are perceived. In addition, since the study is centered on consumers‟ perspective, it is imperative to present consumers‟ behaviours towards new products. The theories presented in parts 2.2 will provide a clearer understanding on how consumers make decision toward the consumption of products or services as well as on how different categories of consumers react in different rates. Furthermore, different definitions and theories are given in part 2.3 to give clear understanding on self-service technologies. Lastly, in part 2.4, the researchers present the model developed by Meuter, Ostrom, Roundtree and Bitner (2005) which explores the factors influencing consumers‟ trial of self-service technologies. It is the key foundation for the paper to identify what factors hinder consumers‟ consumption on products from MiniApotek.

2.1

Five stages of the product lifecycle

The phase of the lifecycle on which the product is can have an impact on the level at which customers purchase or use the product. For example, the technological product (MiniApotek) in this research is new to customers and this can trigger customers‟ desires to know the product first, and then the customers get familiar with it before they can start using it. Therefore this part is important for this study as clarify the different phases of the product lifecycle, which can be viewed in Figure 2.1.

Development phases

The first phase in the product lifecycle is the development phase which starts when a company discovers and builds up a new product idea. This involves decoding a variety of pieces of information and integrating them into a new product. A product usually experiences several changes absorbing a great amount of money and time throughout development, before it is represented to target customers through test markets (Komninos, 2002).

Those products that endure the test market are then launched into a real marketplace and this is when the introduction phase of the product begins. During the development phase, the company or the organization developing the product does not make sales, i.e. sales are equal to zero and returns are negative. It is the time the company spends without revenues in return (Komninos, 2002).

Introduction phase

In the introduction phase the product is presented to the real market. The product should be successfully launched so that it will have utmost effect at the selling period. Therefore the company should be ready to spend more money on commercials and promotion and expect less in return. It is at this phase that a delivery arrangement of the product begins. Pricing is as well considered in this phase (Komninos, 2002; Baines et al., 2008).

Growing phase

It is in this phase that the company which developed the product observes the product extension in the market. This is the proper time for the company to focus on raising the market share. The new growing market awakens the competition‟s attention. The company must demonstrate all the products offerings and try to distinguish them from those of the competitors (Komninos, 2002; Baines et al., 2008).

Maturity phase

When the market gets oversupplied with a variety of the basic product, and all competitors are presented with substitutes, the maturity phase appears. This period is represented by peak returns from the product. A company that has succeeded in acquiring its market share goal rejoices in the most beneficial period; while a company that fails to gain its market share goal, has to reassess its marketing positioning on the marketplace. It is advisable to expand the product‟s life at this period (Komninos, 2002; Baines et al., 2008).

Decline phase

This is the period in which the decision for withdrawing a product from the market can be taken. The company which developed a product faces challenges in making the decision of taking out the product from the market due to the reasons such as, maintenance, service competition attitude to fill the market gap (Komninos, 2002; Baines et al., 2008)

2.1.1 Classification of products

This part is useful to this research since the product can be classified according to the customers‟ behavior during the purchasing process. The theory will assist researchers to analyze why consumers do not try the MiniApotek.

Products can be categorized into convenience products, shopping products, specialty products and unsought products. Each category will be briefly clarified in the next section.

Convenience products

They are non-durable goods or services which are purchased for the reason that the consumer does not want to lay much effort in the purchasing decision. These products are not costly. Customers are not after the product brand but the product itself and if the need for a particular brand rises and that brand is not available, customers can easily switch to a substitute brand (e.g. chewing gum, chocolate) (Baines et al., 2008).

Shopping products

They are not often bought as convenience products and as a result consumers do not have updated information to a purchasing decision. Consumers make a plan to buy these products because they present a higher risk than the one for convenience products (e.g. furniture, jewelry) (Baines et al., 2008).

Specialty products

They are luxurious, present a high risk and are only purchased occasionally, usually once. Customers make plans for the purchase of this type of product (e.g. special sport equipments, Rolex watches) (Baines et al., 2008).

Unsought products

They refer to products which customers do not usually look forward to buying or want to buy. Consumers have little information of the brand on the marketplace and are inspired to locate them only when a particular need occurs (e.g. medicine, insurance) (Baines et al., 2008).

For the purpose of this study researchers will focus on the concept of unsought product because it is applicable to the product contained in MiniApotek, which is medicine. It is useful for this research since customers can observe the machine, feel attracted to it but they cannot use it due to the fact that they do not need the product instantly; they do not need to buy medicine.

2.2

Pre-purchase phases

The aim of the paper is to focus on customers‟ attitudes towards technology; in this case, towards the trial of a vending machine of non-prescription drugs. Due to the fact that the service is in the early period of launching and it is also recognized that consumers do not seem to use the vending machine during the observation, the researchers would like to emphasize on the pre-purchase stage in consumer choice process. In this section, the researchers would like to touch briefly on the first stage of consumers‟ decision-making process to give an overall picture on how consumers react to a product or service.

Solomon, Bamossy and Askegaard (2002, p.6) defined consumer behavior as “the processes

involved when individuals or groups select, purchase, use or dispose of products, services, ideas or experiences to satisfy needs and desires”. Vinson, Scott and Lamont (1977) clarified that the

influence of personal values plays an important role to the decision-making process of when, why, how and where persons do or do not buy the product or service or on why consumers have different evaluations of different brands. Vinson et al. (1977) highlighted the mutual relationship between personal values and consumption patterns. Numerous studies have attempted to explain and analyze consumer choice in different ways. Engel, Kollat and Blackwell (1986) demonstrated five steps in the consumer decision-making process: problem recognition, search, alternative evaluation, purchase, and post-purchase behavior. Similarly Kotler and Armstrong (2004) described the buying decision process in five periods: need recognition and problem awareness, information search, evaluation of alternatives, purchase and post purchase evaluation. Evans, Jamal and Foxall (2009) studied the effect of consumer response to marketing activities by exposure, attention, perception, learning, attitudes, and post-purchase. Most studies focus on the pre-purchase, purchase and post-purchase aspects.

Understanding the pre-purchase behavior is crucial because if it is perceived in the wrong way, it will mislead the whole consumption process. From the stated theories, this stage consists of need recognition, search and evaluation of alternatives. On customer‟s perspective, Solomon et al. (2002) found that the understanding of “how does a consumer decide that they need a

product?” plays an important role in pre-purchase issues. The understanding of factors which

lead consumers to a particular product or service is examined by identifying a need or problem from a buyer, the need recognition step. The step draws attention to the distinctive feature between the actual state and the desired state, a significant difference between “need” and “want” (Evans et al. 2009). Solomon et al. (2002) described “needs are biologically determined

while wants are learned responses to satisfying those needs”.

The next step involves the consumer searching different informational sources to arouse the decision making process (Engel et al., 1986). The pre-purchase search can be supported by internal sources (e.g. existing knowledge, satisfaction with prior purchases) or external sources (e.g. advertisement, friends, and internet) (Solomon et al., 2002). The evaluation of choice alternatives clarifies the evoked set, which the consumer lists and compares the advantages of all different brands he or she would like to buy (Solomon et al., 2002). The highlighted flare the pre-purchase stage is the influence of brand loyalty. Solomon et al. (2002) noted that a consumer‟ repurchasing, which is supported by a positive perception towards the brand and a strong belief that the chosen brand is superior to its competitive items. However, Evans et al. (2009) reveal another aspect of consumer‟s repeated purchase, inertia. The authors clarified that consumers might be indifferent to other brands or there might be high barriers imposed by the brand.

In another major study, Kurtz and Clow (1998) clarified factors influencing the pre-purchase stage by their model presented by Figure 2.2:

Figure 2.2 Components of the pre-purchase phase (Kurtz & Clow, 1998, p. 36)

We recognize that the elements that contribute to the pre-purchase phase in the model of Kurtz and Clow (1998) are identified in the same manner as the elements affecting trial of self-service technology. So, the elements will be chosen and interpreted in the technology context in part 2.4.

2.2.1 Classification of consumers

As previously described the pre-purchase process in consumer behaviour towards a new product or service in general, requires knowledge of specific categories of consumers. Due to the difference in value orientation, personal influences, and objective judgments, consumers can adopt or oppose a new product or service. With the help of the theory in consumer categories, from analysis of empirical findings, we will be able to recognize the motives hindering consumers from using MiniApotek.

Individuals do not adopt an innovation at the same time or at the same level. They adopt it in different rates. Parasuraman and Colby (2001) as well as Baines et al. (2008) classify different adopters into five categories depending on the time of adoption. The five categories are: explorers, pioneers, skeptics, paranoids and laggards.

Explorers

Also known as innovators are the individuals who act fast to obtain an innovative technology. They are confident in their abilities but are not many in a given market context. Explorers think positively about technology, are considered as innovators and they feel at ease and safe about technology innovation. Other people see explorers as the masters of innovation and look up to them for advice. The explorers make it easier for new ideas to flow into the system

Pioneers

They are also known as early adopters and their technology readiness is above average and they occupy the fourth of the market. Pioneers are aware of technology innovation advantages and they want to possess the most recent and the best that innovation can offer. They enjoy technology and they desire to increase their knowledge in it. Pioneers try to some extent to defy technology because they consider technology not to be made for everyone. They perceive a danger in spending too much money for something that is not worth it. They drive the development of the early market (Parasuraman & Colby, 2001; Baines et al., 2008).

Skeptics

Skeptics are mostly recognized as the early majority that takes on new ideas just before the average member of a system. Skeptics reserve themselves from adopting technology even though they feel comfortable and safe to use technology and believe that it will work as expected. They are moderate optimistic and have no desire to become innovators which is why it takes then longer to obtain technology innovations. Skeptics wait for technology benefits to be verified and shown to them before they can act. These consumers are the most numerous adopters and their middle position between explorers and paranoids makes a good connection for the process allowing it to flow in a good way (Parasuraman & Colby, 2001; Baines et al., 2008).

Paranoids

Paranoids or late majority strongly reserve themselves from technology adoption. They lack the spirit of innovation which makes them enter the technology market at a comparatively later phase; when the market development starts to slow down. This group experiences difficulties in using technology without other people‟s assistance. They feel that technology will fail them even before they try it. It is their anxiety and lack of confidence that hold them back from adopting technology. It is significant that the feeling of fear and anxiety be removed from consumers in this group for them to adopt new technologies (Parasuraman & Colby, 2001; Baines et al., 2008).

Laggards

This group of consumers adopts new technology at the last phase. Consumers in this group have feelings of discomfort, insecurity, anxiety that are stronger than the consumers in other categories. They present a remarkable lack of positivism in new technology. Explorers, pioneers, skeptics and paranoids value the expansion of a new technology, unlike laggards. The process of laggards in adopting a new technology is too long and they completely lack trust in new technologies as well as the desire to learn new things. Therefore, in case they come in contact with new technology they will purchase the basic model just to keep things simple for them (Parasuraman & Colby, 2001; Baines et al., 2008).

2.3

Self-Service Technology

Since the technology-based self-service is analyzed in the paper, it is essential to have a general background of self-service technology and vending retail, which supported by the following different theories.

At the present time, Self-Service Technology (SST) has increasingly become a main key on the competitive marketplace where retailers all over the world strive to cut costs and maximize service to their customers. Hsieh et al (2004) emphasized that SST permit suppliers to normalize their contact with customers and this lead to a more reliable service environment self-regulating of employees‟ character and mood.

SST is a convenient and costs and time saving way of satisfying consumers „demand (Quelch & Takeuchi, 1981). Hsieh (2005) illustrated three main business goals for SST, which are, technology delivering customer service, enabling direct transactions and enabling customers to educate and train themselves when using SST facilities. Dabholkar (1996) and Meuter et al. (2000) showed that some customers prefer to use SST because of their being easy to use and for the reason that it helps them avoid direct interaction with retail employees. Hence, Beatson et al. (2006) note that service managers and researchers have the task of being aware of the possible effect these SSTs devices could have on consumers‟ evaluation of their interface with the service organization and what influence this may have on consumers‟ future intent.

However, it is not deniable that problems can arise due to this kid of service provider. Meuter et al. (2000) give many examples such as process failure, technology failure, and caused by customers‟ own mistakes to illustrate customer dissatisfaction with SST usage.

Vending retail concept

Technology advancement is leading the world into extensive utilization of technology- based transactions (Meuter et al., 2000). Through self-service technologies, a multitude of customers interconnect with technology to create a service instead of having a contact with the organization personnel (Meuter et al., 2000). Examples of self services are vending machines, automated teller machines (i.e. ATM), automated hotel checkouts and more. In this paper the interest of the researchers is on vending machines of non-prescription medicine, known as MiniApotek. Quelch and Takeuchi (1981) forecasted that the vending machine would become one of the most important non-store marketing channels. Technology has also made it possible for vending retail to come into existence, as it would not have been possible for retailers to reach customers and satisfy their needs in an easy way otherwise (Quelch & Takeuchi, 1981). Bitner, Brown, and Meuter (2000) suggest that it is essential to recognize the crucial importance of technology in service delivering. According to Bateson (1985) vending machines are defined as devices utilized in vending retailing and are classified as low technology self–service, because the technology found in this machine is not complex. One should mention that vending retail has succeeded in attracting customers who show little interest in walking miles to respond to their needs and also want to save time (Meuter et al., 2000). Vending retail can be done in many ways but in this paper we will focus on vending retail through MiniApotek.

2.4

Key factors influencing the trial of potential customers

This section aims to provide a fulfilled explanation of the main elements which directly affect consumption. The model of customer trial of self-service technology developed by Meuter et al. (2005) is ideal to apply for the paper because it includes most key factors, which are adopted and combined from other authors‟ models (e.g. Parasuraman, 2000; Mick & Fournier, 1998) to give a thorough explanation for the paper‟s main research; that is, finding the reason why consumers do not use or try the new service.

Companies and businesses cannot succeed with their marketing and other operations without technology‟s assistance. According to Meuter et al. (2005), technology has completely modified the way by which services are created, developed and distributed to consumers. Service delivery such as self-service technologies is also increasing every day. SSTs are interfaces which help customers conduct a service by themselves without any assistance from service employees (Meuter et al, 2000).

Figure 2.3 Key predictors of customer trial of self-service technologies developed by Meuter, Ostrom, Roundtree and Bitner (Meuter et al., 2005, p.63)

Figure 2.3 represents key factors of consumer trial of self-service technologies, i.e. factors which drive people to try SSTs technologies. The key factors are grouped into three blocks which are: antecedent‟s predictors, mediating variables and adoption process. Antecedent predictors are in their turn subdivided into two main categories; innovation characteristics and individual differences. The innovation characteristics category contains six variables: compatibility, relative advantage, complexity, observability, trialability, and perceived risk. The Individual indifference category in its turn comprises of inertia, technology anxiety, need for interaction, previous experience and demographics. The mediating variables block assembles three variables

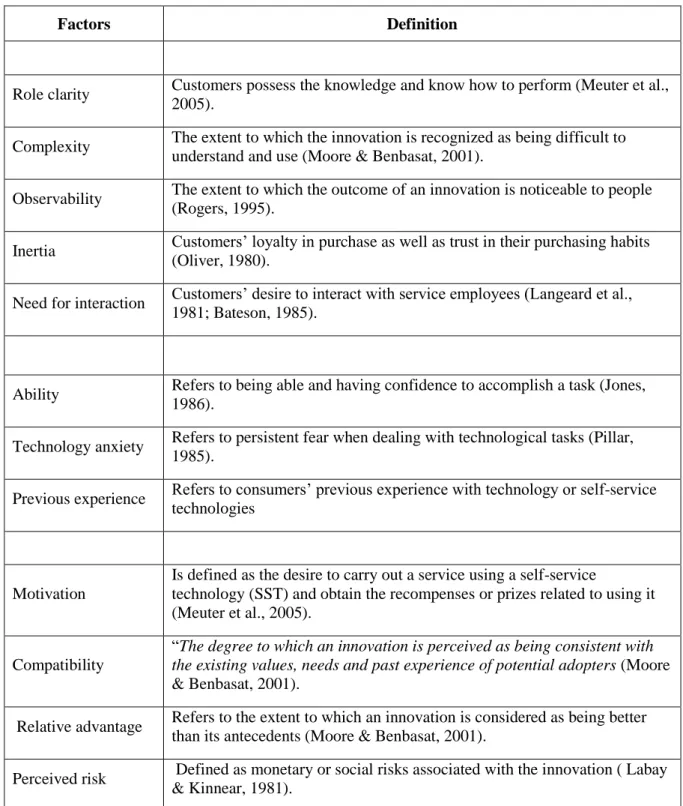

which are role clarity, motivation and ability in a category called consumer readiness. The meaning of each variable is summarized in table 1.

The last part of the adoption process assembles many variables together but trial will be the only variable essential to this study. Firstly, there is a relationship between antecedent predictors and mediating variables and the latter in their turn have a connection with trial. Secondly, there is another direct connection between antecedent predictors and trial.

Factors Definition

Role clarity Customers possess the knowledge and know how to perform (Meuter et al., 2005).

Complexity The extent to which the innovation is recognized as being difficult to understand and use (Moore & Benbasat, 2001).

Observability The extent to which the outcome of an innovation is noticeable to people (Rogers, 1995).

Inertia Customers‟ loyalty in purchase as well as trust in their purchasing habits (Oliver, 1980).

Need for interaction Customers‟ desire to interact with service employees (Langeard et al., 1981; Bateson, 1985).

Ability Refers to being able and having confidence to accomplish a task (Jones, 1986).

Technology anxiety Refers to persistent fear when dealing with technological tasks (Pillar, 1985).

Previous experience Refers to consumers‟ previous experience with technology or self-service technologies

Motivation

Is defined as the desire to carry out a service using a self-service technology (SST) and obtain the recompenses or prizes related to using it (Meuter et al., 2005).

Compatibility

“The degree to which an innovation is perceived as being consistent with

the existing values, needs and past experience of potential adopters (Moore

& Benbasat, 2001).

Relative advantage Refers to the extent to which an innovation is considered as being better than its antecedents (Moore & Benbasat, 2001).

Perceived risk Defined as monetary or social risks associated with the innovation ( Labay & Kinnear, 1981).

The model is very significant to this study because it combines different variables from other researchers‟ models making it strong and reliable. However, not all variables in this original model will be useful in fulfilling the purpose of this research. Hence, it is necessary to modify it in order to make it more applicable to our case and support the reasoning carried out in this research. Minor modifications such as the removal of the demographic variable are necessary because factors such as age, gender, education, region are not perceived as strong influences on customers „decision to use self-service technology, MiniApotek in this case. The reason is based on the assumption that the average Swede in our investigation is able to use automated vending machines whether male or female, young or old, educated or not educated. The subdivision of the motivation variable into intrinsic motivation defined as the sentiment of achievement and enjoyment of carrying out an activity (Meuter et al, 2005) and extrinsic motivation which is the motivation based on price reduction and time savings (Dabholkar, 1996), were summarized into the general variable of motivation. This is the reason why they do not appear in the modified model. Hence, in order to bridge a connection between the model of Meuter et al. (2005) and the stated purpose, the researchers have developed their own model. The model (Figure 2.4) is presented in the next section and it is the only one referred to in the whole paper.

Figure 2.4 Key factors influencing trial of self-service technologies (applied to MiniApotek case)

The steps used to clarify the new model in Figure 3 are the following:

All variables from the original model considered as essential to fulfill the purpose of this paper are divided into three groups in the new model.

There are three consumer readiness factors; role clarity, ability and motivation. Each of these factors represents a group of variables. The variables are assembled into groups

according to the strongest causal relationship they have with the consumer readiness factor representing them. This means that for example, all variables grouped in the role clarity factor are the ones that exercise a strong impact on it. And this holds for the two remaining groups as well.

The next section provides the meaning of each variable in the model and as well brings up the relationship between these variables and the consumer readiness factors (role clarity, ability and motivation) representing them accordingly. Thereafter the connection to trial is shown.

2.4.1 Role clarity

Role clarity signifies that customers possess the knowledge; they know how to perform (Meuter et al., 2005). Before technology advancement a great amount of services were habitually offered by organization‟s personnel (Meuter et al., 2005). However, nowadays technology has brought SSTs into existence and this obliges customers to adopt coproduction comportment (Meuter et al., 2005). This can be argued that customers energetically engage in value creation either by serving themselves (i.e. using an ATM) or by collaborating with service suppliers (Claycomb, Hall & Inks, 2001). Another theory by Bedeian and Armenakis (1981) shows the importance of providing necessary information to each role occupant so that he or she can complete his or her job adequately. In the other way, Larson and Bowen (1989) also argue that the customers can refrain from using the SSTs due to the lack of understanding their role in conducting a service. Furthermore, Ivancevich and Donnelly (1974) perceive lack of role clarity as role ambiguity and clarify role ambiguity as a direct function of lack of compatibility between the information accessible to the individual and the information required to sufficiently accomplish the task. Therefore, Meuter et al. (2005) concludes that consumers who do not know what to do when they encounter an SST are not willing to try it. This shows a direct connection between role clarity and trial. In our case, role clarity is denoted as understanding product usage. This means that consumers are willing to conduct the services themselves based on their degree of understanding how to use SST (i.e. MiniApotek).

Complexity

Complexity is the extent to which the innovation can be known and utilized without problems (Moore & Benbasat, 2001). Antonides and Raaij (1998) state that a product demanding more clarifications and which is difficult to utilize will require a long time to be adopted and in the worse case it will be declined by many consumers. A complicated SST can as well cause anxiety and stress to consumers who are not familiar and do not feel at ease with technology (Mick & Fournier, 1998). Industries which manufacture products of high technological complexity encounter a higher risk of failure, closing down operations and going out of businesses than industries producing less technologically complex products (Singh, 1997).

Technological complexity has a negative effect on intra-organizational diffusion, because it can hinder the potential users (particularly beginners) from trying a new technology (Kim & Srivastava, 1998). Hence, Meuter et al. (2005) conclude that a complex SST will hinder role clarity. The advantages that SST provides will be less appealing to the users causing them to avoid trying the hard and perplexing SST (Meuter et al., 2005).

Observability

Observability is the extent to which the outcome of an innovation is noticeable to people (Rogers, 1995). In his research about consumer adoption of technology-based service innovation, Lee, Lee and Eastwood (2003) argue that the adoption is done when consumers come in contact with technology-based services. This means that, by observing an SST, consumers will become aware of it and if their attitude toward the SST is positive, they will realize its advantages. This will make them recognize their role in adopting an SST. Zander and Kogut (1995) suggest that product observability is one of the five dimensions that determine quality of knowledge in an organization. Once a positive attitude has been created, observability will enhance consumers‟ determination to try an SST (Rogers, 1995). Visibility enhances the comparative disclosure of the innovation and in so doing, motivates discussion by other members in the society. This enhances the speed of information exchange, and ensuring a faster diffusion of innovation (Vishwanath & Goldhaber, 2003).

Inertia

Oliver (1980), in his cognitive framework explaining satisfaction decision, clarifies the role of inertia in loyalty purchase. He experiments “action inertia” on consumers‟ attitudinal phases; that is how consumers become loyal in a cognitive sense, then in affective sense, later in conation manner and finally in a behavior manner. Inertia entices consumers to choose the product or service they most trust and purchase even when they might have better alternatives. On one hand, inertia may form consumer choice. On the other hand, Fishman and Rob (2002) points out that “customer inertia arises because consumers must incur search costs to learn about the prices of new sellers with whom they have not previously made transactions with”. Besides the costs as mentioned above, it takes time and energy for consumers to learn about new technology-based products or services. A direct negative impact of inertia on attitudes towards self-service technologies is that it can cause customers to hesitate trying new service delivery options (Meuter et al., 2005). Hence, Aaker (1991); Gremler (1995); Heskett, Sasser and Hart, (1990) have drawn a conclusion on inertia as a constraint, holding back the change in consumer purchasing behavior which in turn makes the adoption process slow down (cited in Meuter et al., 2005).

Need for interaction

This refers to customers‟ desire to interact with service employees. In his research, Dabholkar (1996) explains the effect of the need for interaction with service employees on services such as touch screens, which could be found in shops. Langeard, Bateson, Lovelock and Eiglier (1981) and Bateson (1985) argue that some customers show an extreme need to interrelate with human beings in a service encounter. Other customers experience that the machine usage dehumanizes the interaction in a service encounter (Breakwell et al., 1986). A high need for interaction will keep customers away from purchasing online, while consumers with a low need for interaction will look for such alternatives (Dabholkar & Bagozzi, 2002); hence, reducing the need to try an SST (Langeard et al., 1981).

2.4.2 Ability

Ability refers to being able and having confidence to accomplish a task (Jones, 1986). According to Meuter et al. (2005), ability is what a person “can do” as opposed to what he “wants to do” or “knows how to do”. Studies demonstrate that when people have confidence in their abilities about SSTs, they are likely to involve themselves in working with computerized task (Hoffman & Novak, 1996). Dabholkar and Bagozzi (2002) also argues that it is anticipated that consumers who possess the technological knowledge are likely to be more willing to use new technology-based services and will not rely on their existing feelings when they make decisions to use mobile services. In the absence of confidence while approaching SSTs, customers feel insecure, challenged and attempt to avoid tasks that are linked to it. This confidence makes consumers believe in themselves and their ability as well; thus, establishing a direct positive relationship between ability and trial (Meuter et al., 2005).

Technology anxiety

This concept stands for persistent fear when dealing with technological tasks (Pillar, 1985). Having technology-based service delivery as an options can cause stress and anxiety to consumers who are not at ease with utilizing technology (Mick & Fournier, 1998).Complex technologies may trigger a feeling of anxiety or distress to people (Kjerulff et al., 1992).These feelings can emerge from difficulties in learning how to use new technologies and fear of errors that could occur in using those new technologies (Abramson et al., 1980), (Cited in Kjerulff et al., 1992). Customers can also get anxious because they have no trust in technology, they are afraid that the technology will not perform well. Johnson (2007) supports this idea arguing that customers‟ trust in SSTs is based on the expectation of competent and reliable performance. The anxiety or discomforting feeling can cause confusion to consumers and they will not understand what to do (role clarity), thereby diminishing customers‟ motivation to use SSTs and confidence in their abilities (Meuter et al., 2005). Hence, Igbaria and Parasuraman (1989); Meuter and Bitner (1997); Parasuraman (2000); Parasuraman and Colby (2001), Raub (1981); Ray and Minch (1990) confirm their opinions that the higher the level of anxiety, the greater the avoidance of technology devices (cited in Meuter et al., 2005).

Previous experience

Dabholkar (1992) and Gatignon and Robertson (1991) demonstrate in their studies that consumers‟ previous experience with technology or self-service technologies positively influences feelings and behavior toward using new technologies (cited Meuter et al., 2005). It appears that previous experience assists to create a more positive attitude just before utilizing the SSTs; however it does not necessarily lead to a more positive attitude toward the service provider. A clarification to this could be that, apart from previous experience, customers assess a service provider according to the way the latter performs while offering a service (Reinders, Dabholkar & Frambach, 2008). Hirschman (1980) explore more on Taylor‟s (1977) findings and propose that previous experience with a product (i.e. SST in our case) can lead to greater ability to handle more advanced products and so increase the chance that they will be tried and accepted (cited in Dickerson & Gentry, 1983).

2.4.3 Motivation

This factor refers to the desire to carry out a service using an SST and obtain the recompenses or prizes related to using it (Meuter et al., 2005). Research has shown that opinions regarding a particular SST and more general opinions toward service technologies will affect intentions to use SSTs (Curran, Meuter & Suprenant, 2003). For example, some research explains that negative views about technology or SSTs such as technology anxiety (Meuter et al., 2000) will reduce customers‟ desire to use technology or SSTs. Other researchers have also demonstrated that positive views towards SSTs and technology such as saving time, cost savings positively affect consumers‟ need to utilize technology or SSTs (Meuter et al., 2000; Dabholkar, 1994, 1996) (cited in Curran et al., 2003). Therefore, it is rational to conclude that a convergence of numerous attitudes can be powerful to behavioral intents. Research argues also that motivation triggers the utilization of SSTs (Pilling, Barczak & Ellen, 1997). Motivation activates consumers‟ curiosity to use the SST, so, motivation has a direct connection to trial.

Compatibility

It is demonstrated as “the degree to which an innovation is perceived as being consistent with

the existing values, needs and past experience of potential adopters” (Moore & Benbasat, 2001,

p.63). Rogers (1962), Moore and Benbasat (1991) define the important role of compatibility as a harmony in perception of innovation in self-service technology and existing values and lifestyles of potential users (cited in Kim et al., 2009). Tornatzky and Klein (1982) provide two types of compatibility which are value compatibility and practical compatibility. Tornatzky and Klein (1982) continue saying that value compatibility is when the innovation is in accordance with the values and norms of the users while practical compatibility is about innovation fitting into endeavors (cited in Kim et al., 2009). Compatibility can as well be dependent on one‟s desire for variety and variety seekers will comparatively accept innovation without difficulty (Antonides & Raaij, 1998). Eastlick (1996); Gatignon and Robertson (1991) conclude that compatibility can raise adopters‟ motivation and they will want to know more about self- service technologies therefore enhancing role clarity (cited in Meuter et al.,2005). Rogers and Shoemaker (1971) clarify the connection between compatibility and trial in that, when people relate to innovation similar to their everyday lives, they will feel compatible to it. This will increase the chance of trying self-service technologies (cited in Labay & Kinnear, 1981).

Relative Advantage

Moore and Benbasat (2001) in their research define relative advantage as the extent to which an innovation is considered as being better than its antecedents. According to Bitner et al. (2000); Brown (1997); Dabholkar (1991, 1994), technology-based service delivery offers advantages to consumers, employees as well as the management (cited in Walker et al., 2002). Customer benefits could be convenience, time saving, conducting transactions without going in the organization building (Quelch & Takeuchi, 1981). Technology is also useful to managers because it allows them to reduce labor costs, and to reply to customers‟ questions and problems in a quick and efficient way (Walker et al., 2002). Recognizing these benefits plays a role in activating customers‟ curiosity to know the functioning of SST, thereby increasing motivation and positively impacting upon role clarity and ability as well (Meuter et al., 2005). If innovation

fulfills a hidden need the chance of its success gets higher (Antonides & Raaij, 1998). When an innovation gets positively perceived, the probability of its being tried gets higher (Moore & Benbasat, 2001).

Perceived risk

According to Labay and Kinnear (1981), perceived risk is defined as monetary or social risks associated with the innovation. These risks determine the pace of the innovation‟s acceptance (Antonides & Raaij, 1998). Classy new product, risky products to one‟s wellbeing as well as products that are barely accepted by others circulate with difficulty or do not circulate at all among consumers (Antonides & Raaij, 1998). Uncertainty considered as perceived risk plays a role in adoption judgment and this is significant in connection to service adoption (Black, 2001). In his research Lovelock (1983) affirms that customers always want to know the characteristic of the product they want to buy, how the product will benefit them. So, the higher the perceived risk, the lower the need to try an SST (Aaker, 1991; Gwinner, Gremler & Bitner, 1998) cited in Meuter et al., (2005).

By analyzing data, researchers find out what variables in these three groups of variables represent the high negative impact on trial. It is those variables that are be used to answer this paper‟s research question.

3

Method

This chapter will demonstrate and describe the selected method for collecting and analyzing data. The process will be clarified and discussed step by step.

3.1

Research Approach

In this study researchers will find out factors that hinder consumers from cause using MiniApotek. Saunders et al. (2009) state that data should be gathered through a survey made of self-administered questionnaires which are usually completed by respondents. They can be administered using post, internet, or delivered by hand to every respondent). Thereafter, researchers will assess the theory and link it to the results. There two types of research approach. The two approaches are used differently and the selection of the appropriate approach to use depends on whether or not one will utilize the theory and the way the theory will be used. In this study the deductive approach will be used. This approach is applicable when one wants to test theory using data, meaning that the data collected will be used to test the frame of theories developed by the researchers (Saunders et al., 2009). A deductive research puts more emphasis on the data making it a well constructed approach which results in independent research (Saunders et al., 2009).

3.2

Research Strategy

According to Saunders et al. (2009), the survey strategy is regularly connected to the deductive approach and is utilized to answer “who”, “what”, “where”, “how much” and “how many” questions. Since the research question of this thesis is the “what” type and the deductive approach is the chosen one, conducting a survey was selected as the appropriate strategy for collecting data.

The survey strategy will in this research be combined with a pilot study and self-administered questionnaires to gather data. This method is useful for two main reasons. The first is that it helps to gather standardized data, permitting easy comparison. The second is that it is relatively simple to clarify and comprehend (Saunders et al., 2009). Through the pilot study researchers will obtain information to carry out the survey. In addition, communication via e-mail with the company that provides the MiniApotek will be conducted, enriching the researchers study with a firm background of MiniApotek. The survey, which is the appropriate strategy for this thesis will assists researchers to recognize and understand the motives for the relationships between variables and assist researchers to construct models of these relationships (Saunders et al., 2009). In this thesis there are thirteen variables. Twelve are independent and one is dependent. The dependent variable is trial, while the independent variables are role clarity, complexity, observability, inertia, need for interaction, ability, technology anxiety, previous experience, motivation, compatibility, relative advantage, perceived risks.

3.3

Quantitative versus Qualitative

For the purpose of this study to be achieved, researchers will gather data using quantitative research. Quantitative data differs from qualitative data in that it applies a natural science especially a positivist approach to social phenomenon (Bryman, 1984). The positivist