Textual computer-mediated

communication tools used

across cultures

MASTER DEGREE PROJECT THESIS WITHIN: General Management NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: Engineering Management AUTHORS: Manuel Diez de Oñate De Toro & Nino Emmerik JÖNKÖPING May 2020

A study about the issues and

consequences that arise from this type of

communication

Master Thesis in General Management

Title: Textual computer-mediated communication tools used across cultures: A study about the issues and consequences that arise from this type of communication

Authors: Manuel Diez de Oñate De Toro & Nino Emmerik

Supervisor: Jonas Dahlqvist Date: 2020-05-18

Key terms: cross-cultural communication / computer-mediated communication /

communication issues / communication consequences

Abstract

Globalisation is increasing, reason for people working more and more cross-culturally and with the use of computer-mediated tools. The field of research on both of these individual topics is existent and has thoroughly been discussed. Nevertheless, the integration of these topics in the field of research is still scarce and relatively unknown. The purpose of this study is therefore to understand the communication issues that arise between people from different cultures when interacting through textual computer-mediated communication tools, and how these issues are dealt with. These communication issues and their consequences will therefore be identified and investigated, in order to get a better understanding of what this entails.

A qualitative study has been done to fulfil this purpose. Data has been collected through nine semi-structured interviews with people from different locations around the world. With this way of data collection, the focus lied on extracting the perspectives of the individuals on these topics. Thereafter the data has been analysed according to seven steps for a grounded analysis, in order to create a theory.

The results of this study have shown that there are mainly three communication issues arising from the use of textual computer-mediated communication tools across cultures. These issues are named as linguistic barriers, cultural differences in communication, and

the absence of nonverbal communication. It has shown that these issues have a significant

impact on this type of communication, causing several consequences. The direct, negative consequences coming from these issues are the deterioration of professional relationships and a decrease in productivity. Next to these consequences, the study has shown that people also tend to develop certain counterstrategies against these issues. That is so to say, ways of minimising the negative impact that the issues have on the communication.

Foreword

On the basis of this foreword we, Manuel Diez de Oñate De Toro and Nino Emmerik, would like to give some attention to the people that helped us to finish this study. In turbulent times due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 virus, we have been able to create this thesis at Jönköping International Business School and are very grateful for that. We want to acknowledge and show gratitude to our thesis supervisor Jonas Dahlqvist, who guided us through this whole process. Other than that, we would like to thank all the participants of the interviews in our research, the other members of our seminar group, and everyone else who has directly or indirectly contributed to the outcome of this study.

i

Table of contents

1

Introduction ... 1

1.1 Background ... 1

1.1.1 Globalisation and cross-cultural teams ... 1

1.1.2 Cross-cultural communication ... 2

1.1.3 Computer-mediated communication (CMC) ... 2

1.2 Problem ... 3

1.3 Research purpose ... 3

2

Theoretical frame of reference ... 4

2.1 Cross-cultural communication ... 4

2.1.1 Defining cross-cultural communication ... 4

2.1.2 Development of cross-cultural communication ... 5

2.1.3 Issues of cross-cultural communication ... 7

2.2 Textual computer-mediated communication (CMC) ... 8

2.2.1 Defining computer-mediated communication CMC ... 8

2.2.2 Different categories of textual CMC tools ... 8

2.2.3 Issues of textual CMC ... 9

2.3 Textual CMC and cross-cultural communication ... 10

3

Method ... 12

3.1 Research philosophy ... 12 3.2 Research approach ... 12 3.3 Research strategy ... 13 3.4 Research design ... 13 3.5 Data collection ... 14 3.6 Data analysis ... 14 3.7 Sample selection... 16 3.8 Ethical considerations ... 173.9 Quality of the study ... 18

3.9.1 Credibility ... 18

3.9.1 Transferability ... 18

3.9.2 Dependability ... 18

3.9.3 Confirmability ... 19

4

Results ... 20

4.1 Communication issues using textual CMC tools across cultures ... 21

4.1.1 Linguistic barriers ... 21

4.1.2 Cultural differences in communication ... 23

4.1.3 Absence of nonverbal communication ... 25

4.2 Strategies against communication issues ... 26

4.2.1 Strategies against linguistic barriers ... 26

4.2.2 Strategies against cultural differences in communication ... 27

4.2.3 Strategies against the absence of nonverbal communication ... 29

4.3 Consequences of computer-mediated communication issues ... 30

5

Analysis ... 33

ii

5.2 Cultural differences in communication ... 35

5.3 Absence of nonverbal communication ... 37

5.4 Consequences of the communication issues ... 39

5.4.1 Negative consequences of communication issues ... 39

5.4.2 Counterstrategies against communication issues ... 40

6

Conclusions ... 41

7

Discussion ... 43

7.1 Contribution to the existing literature ... 43

7.2 Managerial implications ... 43

7.3 Limitations of the study ... 43

7.4 Future research ... 44

8

References ... 45

9

Appendixes ... 49

Appendix A: Conceptual framework of the issues that arise in cross-cultural textual CMC ... 49

iii

List of tables

Table 2.1 - Three dimensions of cross-cultural communication by Hall & Hall ... 6

Table 3.1 - Topics covered with interview questions ... 16

Table 3.2 - List of respondents ... 17

1

1 Introduction

Within the introduction of this thesis, we present the background of the cross-cultural working environment and with a specific focus on computer-mediated communication tools. Then, we guide the reader into the problem of these topics and finally stating the purpose of the study after which the research questions are formulated.

1.1 Background

“Culture is communication, and communication is culture” (Hall, 1959, p. 186). With this statement Hall did not insinuate that both concepts are the same, but that they are closely linked. Communication across cultures has become as frequent as communication within one culture, because of globalisation. Therefore, in today’s world in which distant communication plays a huge role, the importance of understanding the challenges that this kind of communication across cultures encounters is for crucial attention.

1.1.1 Globalisation and cross-cultural teams

The business environment has been affected by globalisation in a way that cross-cultural relations are very valuable today for managers, employees and customers. The composition of companies are also changing as a consequence of their international operations (Browaeys & Price, 2015). Besides, there is an increasing mobility of people and labour towards different countries. These reasons have contributed to the formation of cross-cultural working teams (Sogancilar & Ors, 2018). Hand in hand with the formation of cross-cultural teams, the concept of cross-cultural communication has arisen. In order to fulfil tasks and reach goals, members of these kinds of teams have to communicate and interact between each other, sometimes in a foreign language (Browaeys & Price, 2015).

Cross-cultural teams have proved to be more productive regarding company’s goals than homogeneous teams (Townsend, DeMarie, & Hendrickson, 1998). In general, cross-culturalteams outperform one-culture teams in identifying problems and creating ideas (Watson, Kumar, &, Michaelson, 1993). Thanks to their diversity, they can work in a more creative way (Adler & Gundersen, 2008). They contribute with more ideas of higher quality in brainstorming sessions (McLeod & Lobel, 1992) as well as exposing a variety of perspectives, skills and personal attributes (Maznevski, 1994). Those are the reasons why perhaps having cross-cultural teams in today’s globalised business world is quite widespread for companies (Sogancilar & Ors, 2018).

These kind of teams have become prevalent are rapidly changing the work environment and hence presenting novel challenges for both managers and employees (Matveev & Milter, 2004). They encounter more problems when building trust, therefore it is essential for managers of these teams to maintain cohesion within the team members (Browaeys & Price, 2015). Consequently, the concept of cross-cultural management arises, which describes, compares and more important, seeks to understand organisational behaviours within countries and cultures. The main objective of cross-cultural management is to

2

improve the work between individuals that come from other countries and cultures within the same organisation (Adler & Gundersen, 2008).

1.1.2 Cross-cultural communication

Culture and communication can be considered inseparable, because if one needs to work with a person from another culture it is evident to understand each other (Kawar, 2012). As Kawar (2012) said: “Culture is something that human beings learn and as a result,

learning requires communication and communication is a way of coding and decoding language as well as symbols used in that language” (p. 107). In addition, the cultural

factor of each individual of a cross-cultural team is considered to be the core problem of the difficulties that arise when interacting between each other (Browaeys & Price, 2015). When this happens, it means that two individuals are interacting and they bring their culture’s way of thinking, feeling and living to the interaction. Communication between cultures can therefore not be considered as a comparison of interaction between cultures, but rather as an interactive phenomenon (Browaeys & Price, 2015).

Pym (2004) defines the term of cross-cultural communication as “cross-cultural

communication involves the perceived crossing of a point of contact between cultures”

(p. 2). Differences between cultures have consequences for the communication between people in the way that communication barriers may occur. These barriers result in less effective communication. Understanding a person from another culture may be harder, and therefore understanding cross-cultural communication can result in overcoming these barriers (Kawar, 2012).

1.1.3 Computer-mediated communication (CMC)

There are many different forms of communication available to deliver a message from A to B. For instance, by talking face-to-face, by sending a letter, making a phone call, or through sending emails. The last two examples, communication through the phone or email, are famous forms of computer-mediated communication (CMC). This type of communication is characterised by the fact that the message is transferred by a computer-controlled device (Herring, 1996). There are different thoughts on how to perceive a computer-mediated conversation. A significant issue that comes with this type of communication is that the sender may have a different expectation from the one that the receiver has (Browaeys & Price, 2015). For instance, one can send a message with the single intention to inform another without expecting any reply, while that person may regard the message to be the start of a new conversation. Also, things as writing formality, spelling or text cohesion may be of different importance with different people. When people from different cultures interact, these issues regarding computer-mediated communication (CMC) become even greater, because expectation and resulting behaviours on communication are different (Browaeys & Price, 2015).

3

1.2 Problem

Many advantages and drawbacks have been presented in the background about cross-cultural communication as well as for computer-mediated communication (CMC) tools. We have found that there is a lot of knowledge about the issues of these two topics individually, however, the study of the integration of these two topics is still scarce. Even though CMC offers many advantages in terms of speed and efficiency, it also contains downsides which are even greater when used cross-culturally. The principal issue that comes up with the use of CMC tools is that people have different perceptions and expectations on how to use them. For instance, one person expects his colleague to give him an extensive message which includes all necessary information, while the other person prefers multiple shorter interactions to exchange the same information. Another example is when someone is writing to a ranked person in a company. That high-ranked person may expect a formal message, but if the sender does not use that formal way of composing the message, the receiver may in this case perceive the sender as not capable of writing a formal message or even feel offended. Such issues get even greater when messages are exchanged cross-culturally due to the different communication uses and values. Due to the fact that when using CMC tools such as email or instant messaging typical features of communication such as body language or facial expressions to mitigate or clarify messages are not present. The communication issues that can arise from cross-cultural communications are in general more unfavourable than between one-culture communication (Browaeys & Price, 2015).

In order to keep this research narrow and parsimonious, we have limited the research topics. That is, narrowed down in the use of CMC tools to only the textual form thereof, and in the topic of cross-cultural communication to only the people who work under a similar objective.

1.3 Research purpose

The purpose of this study is to understand the communication issues that arise between people from different cultures when interacting through textual computer-mediated communication tools, and how these issues are dealt with.

In order to fulfil the first aspect of the purpose, understanding the communication issues, we have formulated the following research question:

• How do communication issues arise when textual computer-mediated

communication tools are used cross-culturally?

For the second aspect of the purpose of this research, dealing with these communication issues, the second research question is formulated:

4

2 Theoretical frame of reference

This section is written after having done a thorough literature review which gave us insight on the yet existing theories on the topics of our study. The section is divided in several subsections which contribute to the overall understanding of our research, and helped us to understand and analyse the results coming from the research. Different perspectives and theories that were created on the relevant topics are given.

2.1 Cross-cultural communication

This subsection is written to exemplify the term cross-cultural communication because of the importance of grasping this concept in order to understand the outcomes of this study. As cross-cultural communication is a significant topic of our study, it is evident to understand what this term means and what is known from it. That is described in the following of this subsection.

2.1.1 Defining cross-cultural communication

Communication is a way of expressing thoughts and feelings to another person and is therefore not direct, but indirect. It is impossible for someone to communicate his or her thoughts or feelings directly, but it is possible to externalise or symbolise their thoughts or feelings to another person. It is a process of encoding and decoding messages, where encoding is the process of composing a message with symbols or expressions and decoding is the process of interpreting the meaning of a message made by symbols or expressions (Adler & Gundersen, 2008). Placing symbols together will represent a meaning and there are multiple ways of composing a message, different symbolic types. (Baldwin, Coleman, González, & Shenoy-Packer, 2014) divided communication in several parts. First, there is verbal communication, the use of words, either face-to-face or written. Then, there is the use of body language, gestures and facial expressions, better known as nonverbal communication. Third, there is the use of sounds, including laughter, growling and sighing. Lastly, there is visual communication, using images, drawings, charts or emoticons to convey a message to another.

All these mentioned ways of communicating have in common that they exchange information from the sender to the receiver. With that, there comes a personalisation of the message from the sender and the receiver, which Axley (1984) emphasises in its definition of communication. He saw the act of communicating as a transformation of information from one individual to another. Baldwin et al. (2014) defines communication as the act of interpreting behaviours of other people as well as creating and sending symbolic behaviours to people.

The definition of communication is a tough task as it is such a multi-dimensional and imprecise concept (Ochieng & Price, 2010). People give different meanings on the term of communication, reason for the importance of maintaining an unambiguous meaning for it in this study. We tend more towards the use of the definition proposed by Baldwin et al. (2014), since for us communication is what enables human beings to be

5

metaphorically ‘connected’, sharing emotions and feelings through language. We see communication as a medium to exchange information, the transmittal of understandings. Communicating can thus not go without using language. When communicating cross-culturally, this language gets even more important. As Jiang (2000) explains, the two terms of language and culture influence each other, and can therefore not be seen individually in a cross-cultural interaction. He & Liu (2010) confirms this, and states that cross-cultural communication is crucial for managing cross-cultural teams. Pym (2004) gave a fine definition of the term, saying that “cross-cultural communication involves the

perceived crossing of a point of contact between cultures” (p. 2). Since it is our goal to

investigate the ‘point of contact’ between cultures, this is the meaning for the term of cross-cultural communication that we adopted in this study.

As we are in the field of research of culture, a word with many meanings, we have adopted an unambiguous meaning for the term in order to have the same perspective of the term during the whole research. (Matsumoto, 2006) defined culture as “a shared system of

socially transmitted behaviour that describes, defines, and guides people’s ways of life, communicated from one generation to the next” (p. 220). This definition implies that

people must deal with the same set of biological needs and social problems, which can lead to similar solutions across cultures (Matsumoto, 2006). This is the way that we see culture and also the way that we see this term in relation to the conducted research.

2.1.2 Development of cross-cultural communication

Today’s globalisation increasingly results in the exposure of different cultures to each other and individual people to interact with people from different cultures. It is becoming a necessity to work across cultures and therefore, the ability to communicate cross-culturally is becoming more and more important (Browaeys & Price, 2015). Cross-cultural communication goes further than ‘just’ spoken words or written messages; the essence of effective cross-cultural communication is about giving the right responses rather than about sending the right messages (Hall & Hall, 1990). When people from different cultures have to deal with each other they have to communicate, either on distance or face-to-face. The communication between those people is considered as cross-cultural communication and can involve spoken and written language or body language (Hurn & Tomalin, 2013).

Cross-cultural communication has been broadly studied by different authors since the second half of the twentieth century. Among them, one of the most important authors is Geert Hofstede, who is a well-known researcher in the field of social science and culture. With his study published in 1984 on the effects of culture on human activity, he highlights the unique aspects of cultures and rates them on a scale for comparison. It was created by researching how people from different countries and cultures interact based on different categories of cultural dimensions.

Four key variables were identified in his study; power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism and masculinity. The first dimension, power distance represents the degree of acceptance and expectations of people for unequal distribution of power. Then, the

6

uncertainty avoidance index indicates the level of uncertainty avoidance between different cultures. As third there is individualism versus collectivism, which is the relationship between an individual and society. Lastly, the theory includes the cultural dimension of masculinity versus femininity, which uncovers the roles of gender within a culture and the differentiation of sexes (Hofstede, 1984). The work of Hofstede has been broadly used in the field of cross-cultural psychology ever since and has been further developed (Hurn & Tomalin, 2013).

While Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory is often seen as one of the founding researches in culture, there has also been some criticism. According to Nakata (2009), the theory would not have been correctly applied to the original dimensions. Besides, the fact of the complexity of organisational cultures is barely considered in his research. She also has doubts about the way Hofstede interprets culture, because his theory does not consider the changes that cultures are going through. These criticisms have been the basis for conducting new research in the field of cross-cultural communication (Baldwin et al., 2014). When studying cross-cultural interactions, the theory of Hofstede is a baseline in order to understand the differences between cultures.

Another author who had significant influence in the field of research on the topic of cross-cultural communication is Edward Hall. He is a well-known, recognised researcher in the field of cross-cultural communication, also being one of the first in researching this kind of communication. Before Hofstede’s research, he also studied the cultural differences among individuals. However, Hall’s work is more related to communication than Hofstede’s work, which focuses more on culture itself and the fact of categorising cultures through key dimensions.

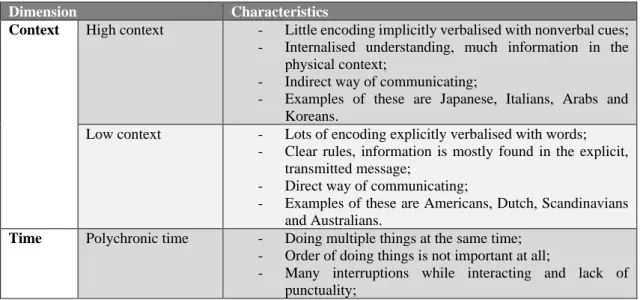

In 1990, Edward Hall and his colleague Mildred R. Hall created dimensions to better understand cultural interactions. They identified three key dimensions of cultural communication in order to help people better understand and communicate cross-culturally. These three dimensions are context, time and space, as presented in table 2.1.

Table 2.1 - Three dimensions of cross-cultural communication by Hall & Hall

Dimension Characteristics

Context High context - Little encoding implicitly verbalised with nonverbal cues; - Internalised understanding, much information in the

physical context;

- Indirect way of communicating;

- Examples of these are Japanese, Italians, Arabs and Koreans.

Low context - Lots of encoding explicitly verbalised with words; - Clear rules, information is mostly found in the explicit,

transmitted message;

- Direct way of communicating;

- Examples of these are Americans, Dutch, Scandinavians and Australians.

Time Polychronic time - Doing multiple things at the same time; - Order of doing things is not important at all;

- Many interruptions while interacting and lack of punctuality;

7

- Time used in flexible ways; it does not control the person’s activities.

Monochronic time - Doing only one thing at the same time; - Order of doing things is crucially important; - Interact actively with small talks;

- Time controls a person’s activities.

Space Territoriality (Physical boundary)

The territoriality of the human is well developed and is very dependent on the culture. In some cultures, space means power. Personal space

(Invisible boundary)

Some cultures would expect to have more/less personal space while interacting with people.

This study by Hall and Hall is seen as one of the fundamental studies within cross-cultural communication. It is crucial for interacting across cultures that these dimensions are taken into account and are being respected. If this is done insufficiently, it can result in lower quality of the cross-cultural interaction (Hall & Hall, 1990).

2.1.3 Issues of cross-cultural communication

When communicating cross-culturally, it is not uncommon that communication issues arise (Hatim, 1997). When a message is sent, the sender and recipient of that message always have characteristics that determine how that message is intended or interpreted. This can cause different perspectives on a message, although the initial transmission of information may still be received. Who the sender is and who the recipient is determines the likelihood that a message will be understood in the same way as it is intended (Adler & Gundersen, 2008). When one sends out a message to another person that he knows for a longer time, chances are bigger that the receiver interprets that message in the way that it is intended. The two persons in this case know each other and will probably better understand the context of the message based on previous communication experiences. When people do not know each other, the likelihood of understanding the message in the way that it is intended decrease. Reason for this is the context that is less present (Adler & Gundersen, 2008). Misunderstandings in communication are unavoidable and will always occur, and in a cross-cultural communication this will happen even more often. Such issues often result in a breakdown of cross-cultural communication (Hatim, 1997). Another issue that arises when interacting cross-culturally is the act of stereotyping and the perceptions and expectations that people have of communication. Stereotyping is seen as the greatest barrier of cross-cultural communications, which is related to individuals’ perceptions (Adler & Gundersen, 2008; Browaeys & Price, 2015; Hurn & Tomalin, 2013). Differences in perceptions and expectations by the receiver and the sender would then hinder the process of understanding the context of the message (Adler & Gundersen, 2008). In an interaction between people of different cultures, the differences in perceptions and expectations of an interaction are even bigger. With cross-cultural relationships it is the case that these relationships often break down due to different understandings of the communication (Hurn & Tomalin, 2013).

8

2.2 Textual computer-mediated communication (CMC)

The creation of this subsection has contributed in understanding the concept of (textual) computer-mediated communication. This research is based on communication that takes place through the use of such textual CMC tools and understanding this concept is therefore of significant relevance to conduct this study.

2.2.1 Defining computer-mediated communication CMC

Across the years, authors have been defining the term computer-mediated communication (CMC) according to their context and circumstances. Herring (1996) defined it in a way that can be easily understandable and to some extent applicable for today, as she stated that CMC is any communication between human beings that is done via the instrumentality of computers. However, Herring’s definition, as many others, emphasised the fact that it is computers that enable those interactions, but today, this argument does not fill the whole meaning of this term any longer. CMC represents any kind of communication that can be done through a computer-mediated device which does not necessarily need to be a computer. The only requisite needed for this term is the use of an electronic device that has an internet connection. For that reason, in this study we use the definition given by Bodomo (2009), in which he emphasised the idea of internet and other technologies, rather than just computers; “CMC is the processing of linguistic and other

symbolic systems through the internet and allied technologies by interaction between sender(s) and receiver(s)” (p. 6).

2.2.2 Different categories of textual CMC tools

CMC is characterised by the fact that the message is transferred by a computer-controlled device (Herring, 1996). There are many different tools available for the use of CMC (Repman, Zinskie & Carlson, 2005). Examples of these different kinds of CMC tools are emailing, instant messaging, intranet, video conferencing, and knowledge sharing communities (Ou, Davison, Zhong & Liang, 2010). As all these different tools have their own identical way of communicating, their features play an important role in the way of using them.

Sending an email might be the first thing that comes to mind when talking about textual computer-mediated communication (CMC). A way of day-to-day communication through computer-controlled devices that might be even more popular is the use of instant messaging. The difference between instant messaging and email is that instant messaging enables messages to be sent and received within a fraction of a second, so the interaction is therefore much faster (Nardi, Whittaker, & Bradner, 2000). Instant messaging can be seen as a communication tool that is mostly used for just social contact, but research has shown that it can be used for professional purposes as well because it ensures a quick way of sharing, transferring and documenting knowledge, however, there are also studies arguing about the drawbacks that they encountered (Ou et al., 2010). It is known that instant messaging is broadly used by employees worldwide and whether they are beneficial or pose distractions for them has been broadly discussed (Garrett & Danziger, 2007; Mark, Gonzalez, & Harris, 2005; Nardi et al., 2000).

9

The above mentioned different textual CMC tools show an important distinction in textual CMC, which is the difference between synchronous- and asynchronous CMC tools (Repman et al., 2005). With synchronous communication, messages can be sent and received within a fraction of a second. The interaction is therefore much faster than communication with asynchronous CMC tools, where reaction times are much longer (Nardi et al., 2000). By connecting individuals instantly, almost real-time communication can be achieved which contributes to the cost-effectiveness of the communication (Ou et al., 2010).

On the other hand, there is asynchronous communication, which is characterised by the fact that the exchange of messages is separated by longer periods of time. This enables individuals to have more time to compose a message (Bodomo, 2009). In other words, people can reflect on the received message and spend some time writing a more elaborated answer.

In this study, we chose to focus on aspecific type of CMC tools, the ones that use text for communicating, although they can also include other unique features such as emoticons or animated gifs used in an interaction. Regardless of the type of ‘timing’ that the CMC tools have; synchronous or asynchronous. The most typical forms of these are email, chat or instant messaging; which are textual CMC tools (Repman et al., 2005).

2.2.3 Issues of textual CMC

To understand the cross-cultural challenges that occur in the context of textual CMC, we must relate them to the general challenges of textual CMC that also occur without the influence of cultures. Since communication through CMC itself involves already a high probability of miscommunications (Cramton, 2001).

Issues for textual CMC are given by several authors and their studies go back until the 80s of last century. Some of these issues are due to the fact that the message is written and may have unique features in it, such as emoticons or acronyms. These features may not be understood by everyone and thereby the message itself or a part of it could be lost or misunderstood (Herring, 1996).

Textual CMC is not suitable for the use of extra-linguistic cues such as facial expressions, which means that the message can still be transmitted, but the personal touch of it will be lost (Herring, 1996). Besides, there are multiple tools available for textual CMC, some of them include more features for the communication than others, and the fewer of these features are available, the less engagement people experiment with the person they are communicating with (Walther, 2011). Some visual cues such as age, disability or ethnic, are irrelevant for some purposes. However, when interacting through non-visual means such as textual CMC, these cues are valuable, as they might help the receiver of the message understand the sender’s context and therefore, explain miscommunications or errors (Cramton, 2001). That is why the use of textual CMC such as email, is considered to be a poor mean of communication as it does not include these visual and nonverbal cues from a typical conversation (Jünemann & Lloyd, 2003). In fact, the lack of these visual and nonverbal cues hinders the process of making judgements about interpersonal

10

trust, which arises from face-to-face interaction with the support of those cues (Wilson, Straus, & McEvily, 2006). So, the only information that people have for that process is the message itself and the way and the context in which it has been written.

Vignovic and Thompson (2010) argues that misspelling or grammar errors, which are inevitably made, can influence the way that communicators perceive each other. The receiver of the message may see the sender as being incapable of writing a grammatically correct message. This may result in negative perceptions of the sender of the message by the receiver. Browaeys and Price (2015) also mentions that inaccurate language and poorly structured text may lead to misunderstandings and even to antagonist feelings from the receiver towards the sender.

2.3 Textual CMC and cross-cultural communication

While we have previously treated the two concepts of cross-cultural communication and textual CMC independently, in this section we will consider the relation between those two concepts. The challenges of cross-cultural textual CMC are uncovered with the aim of underpinning our research.

When two individuals have previous experience in communicating, there is an existing context between those individuals; one individual has more information about how the other individual communicates. The more a person knows the context of an interaction, the more effective the interaction can be. In contrast, when the two individuals that are interacting have a poor relationship, it is harder for them to know the context. Without this context, it will be more difficult to correctly understand the interaction (Adler & Gundersen, 2008). When communicating cross-culturally through textual CMC, this poses a problem when using unique features. For example, the use of acronyms cannot be understood because the recipient does not know what the sender means by this acronym. The same goes up for the use of emoticons. In one culture it might be more common to make use of such features, while in another culture it is very exceptional. Not understanding what someone means with a feature in textual CMC due to not knowing the context of a message can lead to a misunderstanding of communication (Browaeys & Price, 2015).

Lack of context can also be a problem in relation to the absence of nonverbal communication in textual CMC (Cramton, 2001; Herring, 1996; Walther, 2011). Being sarcastic in an email for example may not be understood by the other person because he or she does not see the sender’s facial expressions. The initial message might not get across, and the recipient may even consider the message offensive because he or she has different cultural values on that subject (Browaeys & Price, 2015). Missing context due to differences in cultures plays a major role, as communication between individuals of the same culture may be easier to understand without the use of nonverbal cues (Herring, 1996).

Besides the fact that missing context is the reason for some problems in cross-cultural textual CMC, there are also differences in perceptions and expectations of communication

11

in different cultures (Hurn & Tomalin, 2013). People from one culture expect to use acronyms in their professional emails, while people from another culture think that it is rude. Misspelling can be perceived as a lack of commitment in one culture, while little attention is given to this in another culture. Such differences in cultures may negatively influence a relationship and with that the effectiveness of communication.

Culture involves certain principles and norms in people’s behaviour and the language in which they feel more comfortable when communicating (Browaeys & Price, 2015). According to Vignovic and Thompson (2010), there are two problems that can be originated by those expected norms when textual CMC takes place between two individuals from different cultures. The first is technical language violations (misspelling or grammar errors), and the second is wrong phraseology (incorrect use of expressions, phrases, metaphors). Browaeys & Price (2015) agrees with this, adding that poor structuring of text is also a cause of such problems. When people have expectations of communication to be flawless, grammar errors or wrongly used expressions might result in negative feelings towards the other.

As described above, there are different challenges when using textual CMC that can cause misunderstandings in the transmission of a message. These kinds of mistakes can affect the perceptions of the receiver of a message in a negative way (Hurn & Tomalin, 2013), and possibly create bad feelings towards the sender (Browaeys & Price, 2015). The challenges of cross-cultural textual CMC are thus to be found in the misunderstandings of written messages that cannot transmit the personal message of the sender (Herring, 1996), or that messages contain errors which can cause a negative impact on the relationship between two individuals of that cross-cultural interaction (Browaeys & Price, 2015; Vignovic & Thompson, 2010). Knowing what the challenges are for this type of communication gives people the ability to be prepared on what they should expect from this and be able to use this information in order to have more complete cross-cultural communication through textual CMC.

Cross-cultural CMC has not been broadly researched which makes this specific topic still quite unknown (Vignovic & Thompson, 2010). Studies of cross-cultural communication in themselves exist and the same applies to the topic of CMC, but only few studies have been focused on the combination of these. This study is written with the aim to contribute to that lack of research by seeing the concepts as a whole; cross-cultural textual CMC and the challenges that come up with it.

12

3 Method

This section gives an insight on the way that we have conducted this research. It explains which methods we used in order to come to the final conclusions and motivates the reasons why we have chosen to conduct the study in this way. By doing so, the reader gets an idea of how the research process has been brought to reality.

3.1 Research philosophy

Ontology can be defined as the philosophical assumption that researchers make about the nature of reality. Then, epistemology represents the best ways of enquiring into that nature of reality. Finally, the methods and techniques are grouped together to provide a coherent picture of that reality. If the different perspectives of ontology were represented in a continuum, the realistic perspective would be on the one side of the extremes and on the other side, the nominalist perspective. The realistic position assumes that physical and social worlds exist, independent of any observations made about them. On the other hand, the nominalist perspective assumes that social worlds and objects are ‘formed’ by the language we use and the names we attach to them. Between these two extremes, there also exist the internal realism and the relativism, which are closer to the realism’s perspective and the nominalism’s perspective respectively (Easterby-Smith, Thorpe, Jackson & Jaspersen , 2018).

From the ontology view we assumed a relativist perspective, due to the implicit nature of the topic of our study; communication. Communication in our research is seen as a social construct, an intangible concept that people have created, and is the result of the ability to talk in a specific language. Because every individual has a unique way of using a language, communication has as many definitions as individuals use languages. So, we assume that our view from the research is relativistic, as we acknowledge that there are many ‘truths’ regarding communication and that it depends on the observer’s point of view (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018).

From an epistemology perspective, we adopt a constructionist view in our research, because we are addressing the study of this topic by dealing with the perspectives and expectations of individuals. The idea of constructionism focuses on the ways that people make sense of the world, especially through sharing their experiences with others via the medium of language (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). So, our epistemology follows logically the approach settled down by our ontological view.

3.2 Research approach

As discussed in the previous section, our research followed a more constructionist research strategy. With this type of research, a theory is generated, rather than having tested an existing theory. The creation of a theory implies that an inductive study has been done. Following this strategy has resulted in the assessment of existing theories and we supplemented the subject field with non-existent theory (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018).

13

In this inductive study, existing theories and data about the field of study were first to be gathered. The literature review and the resulting theoretical framework served as the open exploration of the field of study and contributed on shaping the direction of the study. Gathering the data has been done in the form of semi-structured interviews, with a specific level of focus. After collecting this information, we have analysed it using the appropriate methods and trying to find existing patterns. By doing so, conclusions could be made and with that, a theory was developed.

3.3 Research strategy

There are many existing theories about cross-cultural communication and textual CMC tools as individual topics. However, we have found that theory about these two topics combined is scarce, one of the reasons for us to do a study in this field. The fact that there is not a huge amount of existing theory on the combination of these topics, makes it harder to understand what these topics combined entail. In order to create such a theory, it is, first of all, important to find out what the different perspectives of people are on this matter. This is the reason why we have chosen to do a qualitative study, as we saw this as the most appropriate research strategy to apply to our study. We did not propose a hypothesis to test, but we proposed research questions in order to reach and understand people’s perspectives on the combination of the topics of cross-cultural communication and textual CMC. Choosing for a qualitative study was more appropriate to identify the different perspectives on this, while choosing for a quantitative study would mean that the focus would be on proving something, which was not our intention. Our aim has been to delve into the topic of communication, a term that has different meanings between people and companies, and the qualitative strategy has enabled us to find the differences. Gaining that knowledge in combination with the existing theories gave us the possibility to create a new theory regarding the combination of those two topics.

3.4 Research design

The focus of this study is to create a theory based on individuals’ experiences through semi-structured interviews. In order to do so, the multiple theories studied and presented in the theoretical frame of reference have been used as a basis for generating that theory. To extract this data, a grounded analysis approach has been followed. We partly used the approach proposed by Glaser and Strauss (1967). They saw the key task of the researcher as being able to develop theory through looking at the same event or process in different settings or situations. Nevertheless, they had some differences when addressing grounded theory, as Glaser proposed a more objective perspective stating that researchers should not start with presuppositions, rather allow ideas to ‘emerge’ from the data (Glaser, 1978, 1992) while Strauss recommended researchers to know previous research about the topic and have some structured process to make sense of the data (Corbin & Strauss, 2015; Strauss, 1987). However, we are embracing Charmaz’s approach in which she argues that a constructionist approach should recognise that “the viewer creates the data and ensuing

14

3.5 Data collection

We have collected multiple articles as well as books in different rounds to be able to specify our research topic. At first, we used several keywords which brought us in the area of research that we wanted. By studying these articles and books, we created a new set of keywords to narrow our topic and find more specific literature. Then once again, a new set of keywords resulted out of that which made us more familiar with this field of research and able to understand our problem. This has been fundamental to the continuation of the research. Along this search, we have used the advance search mode of the Jönköping University Library browser for academic papers, named ‘Primo Search’. As previously mentioned, our primary data has been collected by doing semi-structured interviews. Interviews are considered as the best way of obtaining maximum information from respondents (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). All of the interviews have been recorded, and the majority of them have been done through video calls, due to the situation caused by the spread of the COVID-19 virus. The interviews recorded were transcribed with the help of a software. This was important in order to analyse the collected data through the use of coding. The questions in the interviews were open-ended and were based on the following four components:

-Core phenomenon: taking a look at what the actual process is, what is the view of people on the use of textual CMC in cross-cultural work environments; -Causal conditions: determining what influences the process of using textual CMC cross culturally for the respondents;

-Strategies: what are the strategies of respondents in order to deal with the influences of cross-cultural use of textual CMC tools;

-Consequences: what are the outcomes of the used strategies by the respondents? On the basis of the above-mentioned components, the results from the conducted semi-structured interviews contributed to fulfilling the purpose of this study.

3.6 Data analysis

To analyse the collected data, we have used a grounded analysis by following the seven steps proposed by Easterby-Smith et al. (2018). With this way of analysing, we tried to keep an open approach to the collected qualitative data. With this grounded analysis we were able to draw up a theory based on the comparison of different fragments of the collected data. We were faithful to the views of the respondents and we have come to a more inductive reasoning.

Before going into the first step, we transcribed the interviews. The transcriptions of the interviews were done with the help of the website Otter Voice Meeting Notes (https://otter.ai/) and the recorded audio files from the interviews. All the participants agreed to be recorded during the interviews, so we could transcribe all of the interviews

15

using this website, which automatically transcribed the recorded audio files. However, with every transcription, we had to check them to see if they had been correctly transcribed or if adjustments where needed.

Once the interviews were transcribed, we started to get familiarised with all the data, by reading the transcripts. Then, the reflection part took place, where the data was criticised and evaluated according to previous studies and theories.

After that, in order to start the coding process, we introduced all the transcribed records into the software called ‘MAXQDA Analytics Pro 2020’ (VERBI GmbH Berlin, 2020), a program designed for analysing data for qualitative research. This program helped us in the whole process of analysing the data, enabling us to conduct the different steps of the coding process as well as not missing any important information, having all the data organised and easy to access.

Firstly, we started the so-called ‘open coding’, which means reading the transcripts and determine the different categories in the data. We gave codes to all the data. With MAXQDA Analytics Pro 2020, we were able to give these codes different colours, different importance or ‘weight’ as well as subdividing them in themes. The process of open coding was finished when there were no new codes emerging from the data. After the open coding, we conducted the conceptualisation part, also known as ‘axial coding’, where the codes from the open coding were used to see how the different categories relate to each other by similarity, difference, frequency, sequence, correspondence or causation.

The last part of coding and the fifth step in our data analysis was the ‘selective coding’, which means that we have tried to write a storyline with an overall explanation of the theory. After the coding, we proceeded with the next step, the linking part, where the patterns between different concepts started to emerge. A funded explanation could be given on how the key categories related to each other.

The last step of the analysis was the re-evaluation part where we evaluated our work based on comments of others and determined where more work was needed in order to successfully use the collected data.

Assigning codes to the different parts of the collected data with the help of a software, enabled us to analyse the data in a structured way. Result of this is that the data could be compared based on the categories, patterns and trends could be found as well as agreements and disagreements between different respondents, which became clear. This resulted in an overall perspective of the topic from these respondents.

From the beginning of the coding process until the end of the analysis, we created memos attached to some of the codes in order to register our thoughts and findings. This helped to ‘develop’ these codes along the whole process of the analysis.

16

3.7 Sample selection

In order to fulfil the purpose of the study we reached out to people that meet certain criteria. First of all, they had to work in a cross-cultural environment. This includes people that work in their home country but with several international colleagues, as well as, people that work in a foreign country with people from that country and other cultures. Independently of the company they worked for, we focused on candidates that regularly work with people from other cultures. The other criteria that participants had to meet was that those cross-cultural interactions should be made partly using textual CMC tools, such as emailing or instant messaging. Additionally, we tried to find people ranging from young to old, so that we received perspectives from people from different generations. Therefore, we follow a theory-guided sampling selection and the more the interviewee had contact with people from other cultures, the more reliable the information he or she shared was.

For the data collection we divided our interview questions into different topics, related to the research questions that we had to answer. The first research question focused on identifying the communication issues that arise with the use of textual CMC across cultures, and therefore the topics two to four from table 3.1 were set up. The second research question was formulated to reflect on the consequences that these issues bring to people working under the same objective, for which the fifth topic of table 3.1 is set up.

Table 3.1 - Topics covered with interview questions

In order to conduct the interviews, we selected people from our network who met the established criteria, as well as people outside of our network from either big or small companies. Most of the interviews were done through video-call, one interview through a phone-call, and two interviews were done face-to-face.

Topic Purpose of topic

1. Introduction Getting to know the respondent

2. Textual CMC Use of textual CMC, potential issues and how respondents deal with this 3. Cross-cultural

communication

Use of cross-cultural communication, potential issues and the used strategies against this

4. Cross-cultural textual CMC

Combination of the previous two topics and the respondent’s perspective on this. Trying to find used strategies to avoid/solve arising issues 5. Affecting professional

relationships

Determining how communication issues affect professional relationships and thus the work for the common objective

6. Closure Giving the respondent the opportunity to add ‘forgotten’ information in the interview

17

Below, in table 3.2 there is a list with the respondents of our interviews, their positions, nationalities, location of work and their reference number (one to nine) used when referring to them later in this report.

Table 3.2 - List of respondents

Respondent Function Location Nationality Type of interview

Respondent 1 Cyber security analyst Spain Spanish Video-call

Respondent 2 Technology consulting analyst Spain Spanish Video-call

Respondent 3 Product developer Belgium Spanish Video-call

Respondent 4 Sales-manager Sweden German Face-to-face

Respondent 5 Parts specialist Sweden Bolivian Video-call

Respondent 6 Business analyst Netherlands Dutch Video-call

Respondent 7 Manager Industrial Control IT Sweden Swedish Phone-call

Respondent 8 Junior project manager Belgium Turkish Face-to-face

Respondent 9 IT development engineer Netherlands Dutch Video-call

3.8 Ethical considerations

Although management and business research do not put in danger the lives of those who take part in the research, there is still ethical issues that apply to this type of research. For instance, a student breaking rules of confidentiality can put in danger the continuity of a participant in his or her organisation (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018). So, we believe that especially when the research level and experience of the authors are low, ethical issues must be considered meticulously.

For addressing these issues, we have followed the ten principles of ethical practice identified by Bell and Bryman (2007) which are the result of a content analysis of the ethical codes of nine professional associations in the social sciences. The first six principles are about guaranteeing the protection of the participants of the research, and the last four principles proposed by Bell and Bryman (2007) are about assuring clarity and veracity of the results of the research which aim to protect the integrity of the research community (Easterby-Smith et al., 2018)

We protect the participants of the research according to the six principles, which means firstly that no harm was or will be caused to the participants for their collaboration in the research, that their dignity was respected in every moment of the research and the interview, keeping their information confidential and protecting their privacy and informing about the process of recording the interviews.

On behalf of the research community, we assured that full transparency was adopted when reporting and analysing the results, avoiding misleading or false reporting as well as using the sources of the references and themselves.

On the other hand, we addressed the ethical considerations in relation to the topic of our study. This topic and the given results would not endanger any individual, company or industry sector since we researched a topic related to the communication between individuals in a professional environment which is common to every individual regardless of the type of sector in which they work. In fact, the outcome of our study could only

18

benefit any of these actors by making them aware about the fact that cross-cultural communication may present some issues not because the lack of a specific knowledge related to their field but for the process of communicating itself.

3.9 Quality of the study

To evaluate the trustworthiness of the study, the four dimensions proposed by Guba (1981) for qualitative studies have been used. This enabled us to ensure the credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability of our research, which are now elaborated accordingly.

3.9.1 Credibility

We could establish confidence in the ‘truth’ of the findings as we believe that our particular inquiry did not make our respondents feel uncomfortable, so they could answer in a calm and relaxed way, which therefore, motivated them to be honest. At the same time, our topic of research was not requiring sensitive or confidential information from their companies or colleagues, another reason to believe in their insights. We engaged participants in calm and comfortable conversation about their interactions through textual CMC tools. Besides, this topic did not require technical or specific knowledge from the participant and therefore it was easy for them to correctly interpret and answer the question in the expected way. Lastly, as the field of our research is still not very spread, the judgements that respondents could have beforehand on the topic were, in our view, scarce and that along with all the reasons stated above, may enable them to share their thoughts more openly.

3.9.1 Transferability

The degree to which the findings can be applicable to other respondents or to other context could be considered as one of our weaknesses as there are innumerable cultures worldwide working in many different contexts. However, all the participants were working in different sectors and industries. Besides, even though all the participants worked in Europe when this studied was conducted, several participants also worked in other parts of the world, and most of them continuously worked with people from other cultures. So, we believe that our findings can be applicable to other contexts.

3.9.2 Dependability

Concerning the findings of our study, we believe that they could be consistently repeated if the same inquiry was been replicated in the same or other context and with the same or different respondents. This due to the broad range of cultures addressed as well as the wide range of age from the respondents, the different industries in which they worked for, and the difference in the history of their companies. Some respondents worked in start-ups with fewer than ten employees, and others worked in bigger firms with more than 500.000 employees. However, in the long-term the findings of this study might be different as they are based on people’s norms and values which are social principles that may not remain the same over the time.

19

3.9.3 Confirmability

We assume that the degree to which the findings of our study are not due to biases or motivations, interests or perspectives, but rather only from the respondents enquired. This is mainly due to the purpose of this study which addressed a topic that given any result would not pose benefits or drawback for any specific group of people or industry sectors. In addition, along with the research, the authors have followed strict and organised processes to collect, organise and analyse data.

20

4 Results

This section represents the results that came from the data collection by means of semi-structured interviews. Several themes have been extracted from the collected information and the main findings have been reported in this section. First, by stating the most common issues of using textual CMC tools across cultures. Then, the counterstrategies that people develop have been presented, and finally the consequences of these issues.

The goal in this research was to gain an understanding of the communication issues that arise when using textual CMC tools across cultures. The interviews that have been conducted have been focused on extracting information about this specific topic. In the sequel of this section, we presented the relevant collected data in order to support the analysis part. Before addressing the content of the data collected from the interviews, we presented the themes that emerged from coding the transcriptions (see table 4.1). A total of six main themes were identified, each of these of different importance to the research. The most relevant categories to our research were the first three themes. The first theme included information related to the communication issues when using textual CMC tools across cultures. The second theme comprised all information on counterstrategies that people develop against these issues. The third theme included the given information about the consequences that these communication issues bring forth.

As mentioned, the first three themes were the most relevant to this study, because they combined the two research topics addressed; cross-cultural communication and the use CMC tools. The other three themes provided relevant information on those research topics individually, but did not include the integration of those two research topics. Therefore, the information from these themes was considered when presenting the results, but they were not treated individually.

Table 4.1 - Themes of collected interview data

Nr. Theme

1 Communication issues when using textual CMC tools cross-culturally 2 Strategies to avoid such communication issues

3 Consequences of such communication issues 4 Aspects of textual CMC tools

5 Aspects of cross-cultural communication 6 General independent information

21

4.1 Communication issues using textual CMC tools across cultures

In the conducted interviews for this research, various issues have been brought forward by the respondents. These issues were very divergent and were somehow related to the aspects of culture or communication. However, in our research we tried to focus on the issues that included both aspects at the same time. The communication issues raised by the participants that met these conditions, and thus had significant relevance for our research, have been presented.

4.1.1 Linguistic barriers

One of the most common issues that arose from the cross-cultural use of textual CMC tools according to the collected data was the existence of linguistic barriers. The use of a non-native language has often proved to be the norm in cross-cultural communication. The participants of the interviews indicated that the spoken language in their working environment was mainly English. Speaking in another language than the native language can provoke issues in the communication according to the answers of the respondents. Such linguistic barriers are the result of insufficiently mastering a language, which means that some specific terms, words or sayings may not be able to be used or understood. This is at the expense of the quality of the communication.

This issue has been explicitly raised several times by different respondents. A statement that clearly shows this is given by respondent 9:

“My English is also not very good and we both have to talk in a language that is not our mother tongue, and that makes it also difficult of course, in writing and talking” (9)

Another participant that shared his experience of this issue said:

“The language can be a really hard problem (…) If I talk with someone from the U.S., it is clear that a misunderstanding can happen, because I might not really understand some small short words that they say.” (5)

Because of speaking a non-native language, communication between people gets more difficult according to our respondents. Since this is often the case with cross-cultural communication, the probability of communication issues increases. The information in the message may not entirely be understood, or it may be more difficult to communicate the intended information in the message. Therefore, this issue seemed twofold, consisting of both the composition and the understanding of a message.

Respondent 4 shows us why the communication is made more difficult, by saying that the composition of a message becomes harder for him when not speaking the native language:

“Even though all of us speak very good English, sometimes you have to find (a word) because we are not all native speakers.” (4)

22

When asking what the disadvantages of communicating with people from other cultures are, respondent 3 answers:

“Not being able to express yourself if you do not have a good level of English. (…) One colleague that started working with us did not have a good level of English, but his mother’s language was French, and some others (colleagues) spoke French as well. So, I saw how he expressed himself in French, but when he wanted to express in English, I saw that he was like another person.” (3)

The difficulties that our respondents have indicated with setting up messages in a non-native language can thus limit a person in the way that they can express themselves. Obviously, this part of the linguistic barrier in cross-cultural communication can have a significant negative impact on the interaction between people.

Having more trouble with composing a message when talking another language is one thing, but understanding a message in a language that is not your own, is another thing. This matter has also been raised by several respondents, and a good example for this is provided by respondent 8. Although this example may include phone calling, which is not a textual CMC tool, it does indicate what the problem is here with the use of synchronous (textual) CMC tools when people do not speak their native language:

“In the Arabic countries they always want to call, but the problem is that their English is not good. (…) I did not understand maybe 70% of what he told me.”

(8)

Another example of communication issues that occur due to not being able to understand a message correctly is given by respondent 1. He states that he notices that some people that he communicates with, do not have the best understandings of the English language:

“Indian people have problems with the language. They do not understand English really good, and they do not ask for 'Can you repeat?', or 'Can you say that slowly?', they just assume (the message).” (1)

The given examples above are communication issues that arise with the understanding of an interaction. In these cases, the issue is mainly focused on the use of synchronous CMC tools, a reason to think that the issue of understanding a message in another language is most common. However, the issue of not understanding a message properly due to not understanding that language sufficiently can also appear in asynchronous CMC tools. An example is given by respondent 5:

“Sometimes Indian people also use a saying, and I do not know if that is from Hindi or that they translated it in English, or that it is in original English. (…) If you do not understand it, the only thing you can do is let them know, and yeah, then the clue is already gone of course.” (9)

In the example given above, not understanding the words is not the problem, but misusing a certain saying is, which can form an issue for understanding the message. This shows