Parental guidance in occupational therapy:

Promoting the participation of children with

autism spectrum disorder in everyday life

activities – a scoping review

Petra Enroth

Thesis, 30 credits, two-year master

Occupational Therapy

Jönköping, March, 2021

Supervisor: Frida Lygnegård Examiner: Dido Green

Aim

This study aimed to determine what is known from the existing literature about parental guidance during occupational therapy to promote the participation of children with autism spectrum

disorder (ASD) in everyday activities.

Method

The scoping review methodology was used to gather existing information on the topic. The following databases were used for searches: The Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and MEDLINE.

Results

Ten studies were included in this study, as they met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The results of the selected studies were thematically organised. Three key elements emerged from the results that promoted the participation of children with ASD in everyday life activities: increased knowledge and awareness of parents; new practices and changes in everyday life; supporting and strengthening parenting.

Conclusion

The findings of this study suggest that parents have a central role to play in promoting child participation. Parental guidance is an ideal way to promote the participation of ASD children in everyday activities, as parents are involved in children’s daily lives and influence children’s natural environments. The results of this study can be utilized in occupational therapy practice for the implementation of interventions.

Keywords: ASD, children with ASD, daily activities, involvement, occupational therapy, parental guidance

Introduction

Parental guidance as a means of occupational therapy is one of the critical elements for

promoting the participation of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in daily activities and the well-being of their families [1]. Parents have an essential role to play in promoting child participation. Parents´ views, choices, and activities in everyday life significantly influence children’s opportunities for participation, as parental choices tend to determine the opportunities available for the child and the environments in which the child operates [2]. Additionally, parents can provide unique information about a child's interests, abilities and needs [3]. Parents of

children with ASD are likely to know their children the most and thus help to take a child’s perspectives into account for daily activities and rehabilitation.

ASD is a developmental condition that involves challenges in social interaction and social communication as well as limited and repetitive patterns of interests and behaviour [4]. The Finnish Pediatric Neurological Association [5] states that it is central to the rehabilitation of children with ASD that the daily routines of the home consist of rehabilitative elements and goal-oriented training. Appropriate guidance enables the practicing of skills in daily life [5]. Parental guidance enables the transition of rehabilitative elements to the daily life of the family and the child’s natural environment [6]. By working with parents, occupational therapists support parents to adapt and manage everyday life with their children and set goals in children’s daily routines [3]. Collaboration with parents is related to the child’s progress; the goal is to help children perform daily activities by promoting their skills and independence [3, 7]. Through parental guidance, the daily lives of children with ASD can be influenced at an early stage. Early

interventions for them promote the development of skills that enhance adult competence and increase participation in physical, social, skills-based activities, and work [8].

Children with ASD need parental help and guidance to participate in activities because they participate less in social, and recreational activities compared to typically developing children [8,9]. Occupational participation defines what we do and describes our engagement in activities of daily living [10]. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) [11] describes participation as a person’s “involvement in a life situation”. The ability of a young child to be involved and socially interact with others develops in a child’s close relationships [11]. Children with ASD have difficulties in social participation related to social awareness, social motivation, social communication, theory of mind, and executive functions [9, 12]. Children with ASD further face challenges performing daily tasks [13]. These lifelong difficulties make it difficult for children with ASD to participate in social, play, and leisure activities [14, 15]. The activities they engage in are stereotyped and

well-structured, and the presence and guidance of parents are needed [8,9,16]. The challenges faced by children with ASD in coping with daily life and participating in everyday situations are vital to recognize because human engagement in meaningful occupations can significantly impact health. The lack of meaningful occupation can have serious health effects [17]. Humans need to use their time purposefully; occupation is a basic need for our health and survival. It is a way to use and develop innate capacities and to adapt environmental changes [17]. Parental guidance can help to increase parental knowledge and ability for guiding children to participate more in daily life activities, thus increasing a child’s possibility of functioning in various daily environments. Depending on the research content and emphasis, different terms are used for parental guidance. In this study, parental guidance is an umbrella term that includes various ways to guide parents (appendix A). Parental guidance in occupational therapy can consist of a variety

of elements, such as sharing information and advice; coaching; reflective discussion and

feedback; joint goal setting; modelling; providing support; and learning different coping learning strategies and intervention techniques in everyday life [1, 18- 20]. Central to these interventions is a collaboration between the therapist and parents as well as efforts to promote the daily life of the child or family. Parental guidance frequently aims to increase parents’ abilities and skills to facilitate daily life and promote child participation. Interventions that include modelling, coaching and feedback, as well as a focus on relationships, can increase parental flexibility, responsiveness and sensitivity. These elements may have a positive effect on a child’s emotional and social functioning and development [6].

Parental guidance that focuses on occupational performance coaching can help parents in achieving goals, use parents’ skills in the child’s natural environments, and increase the participation of children with special needs [19]. During the coaching process, the therapist makes observations, listens, and instructs the parent to learn the skills needed to advance the child’s skills [15]. Additionally, it has been shown that guiding parents through training is an effective way to promote the generalization and maintenance of skills in children with ASD [1]. Parental guidance aims to increase parents' ability to implement new ways of promoting the daily life of their children. When parents implement interventions, the goal is to identify the necessary interventions; parents are instructed on how to implement them in practice and receive feedback and consultation during the process [20]. Teaching a parent or family member to implement interventions has been shown to have positive effects on the adaptive behaviours of young children with ASD [21]. Providing structure for problem-solving and reflective guidance, parents can achieve prioritised goals, which can lead to significant improvement in children’s

participation [22]. Additionally, teaching intervention techniques to parents of challenging children can reduce parental stress [23], which is vital for the parents of autistic children, who

experience more stress than other parents [24, 25]. Parents need to be supported during the guidance process, and parental preferences need to be respected [26]. The success of interventions requires parental commitment, consideration of parent and child abilities and characteristics, and focus on the interaction [6].

The model of human occupation (MOHO) describes how individuals engage in occupations as a result of the dynamic interaction of the four central elements of the model: volition, performance capacity, habituation, and environment [27]. MOHO explains how individuals are motivated to perform occupations (volition) and repeat them over time (habituation). Performing occupations affects an individual’s performance capacity. All

occupations take place in a certain environment that facilitates occupational engagement.When attempting to influence the daily lives of families with children with ASD through parental guidance, it is essential to be aware of how the family maintains daily routines and patterns of actions, guided by habits and roles [27]. It is necessary to take into account the individual starting points from which the change will be implemented for families and children. Parental guidance can influence the role of parents, including their attitudes, behaviours, and self-perceptions related to role expectations [27]. Assuming that the aim is to strengthen the active role of the parent, it is essential to take into account the parent's perception of capacity and effectiveness as well as the parent’s interests [27]. Guiding families of children with ASD requires both family and child motivation child during the process. The volitional approach provides information about what types of thoughts and feelings are related to parents’ and children’s abilities and effectiveness, what kind of things bring pleasure and satisfaction for them, and what is meaningful to them [27].

Through parental guidance, parents’ perceptions of their children’s performance capacities may increase along with parents' experiences of their own performance capacities. The

MOHO defines performance capacity as the ability to perform tasks based on the state of physical and mental components in relation to a person’s subjective experience. An individual’s subjective experience of one's performance capacity modifies behaviour, which is vital to recognize if changes are desired [27]. Additionally, it is crucial to consider the effects of the environment on the functioning of a child with ASD. According to the MOHO, the environment can provide opportunities and motivate a child to participate, and, in contrast, the environment can further set requirements and barriers for this child [27]. Parental guidance can increase the understanding of environmental effects on a child’s ability to function and participate in activities. As

understanding increases, parents can potentially be supported in creating and seeking more supportive environments for their ASD children. Key elements of the MOHO and various elements of parental guidance increase the understanding of parent and child motivation, family habits, existing capacities, and environmental impacts [15,18, 19, 27,61-63]. Parental guidance must additionally take into account the dynamic relationships among these key factors in MOHO; changes in one element affect other elements [27].

There is a need for further research on this topic. Occupational therapists benefit from mapped information on parental guidance to identify the key elements that make parental guidance successful and to help their practical work with children. Children with ASD are fairly common client groups in occupational therapy [15]. Family involvement is a central factor in the best practices associated with paediatric occupational therapy [2], and evidence-based practice is a requirement for all occupational therapists [28]. However, occupational therapists occasionally do not use research evidence to support their clinical work and decision-making [29-31]. It is vital to recognize that programmes implemented at home are only useful when based on effective interventions [26, 31]. Moreover, parents are most engaged in home treatment programmes when these treatments are shown to be meaningful [32]. There is a need to focus on this specific target

group, as several studies related to parental guidance include several diagnostic groups. ASD has a significant impact on the daily lives of families and poses specific challenges to children’s development and participation [33]. Therefore, a greater understanding of the role of coaching parents of children with ASD should be explored. This study aimed to explore what is known from the existing literature about parental guidance to promote the participation of children with ASD in daily activities during occupational therapy and provide an overview of its key elements.

Materials and methods

Research question

What is known from the existing literature about parental guidance during occupational therapy to promote the participation of children with ASD in everyday activities?

A scoping review is a popular approach to reviewing health research evidence and finding relevant literature on the topic [34, 35]. Scoping reviews generally refer to ´mapping´, which is a process of summarizing the evidence and describing the extent of existing evidence on a topic [35]. The scoping review methodology provides an excellent method of summarizing and

disseminating research findings and of exploring the nature, extent and range of research activity. In this scoping review, the methodology of Arksey and O’Malley [34] was used to gather existing information on the research topic. This study was conducted according to the five stages of the methodology [34]: a) identifying a research question, b) identifying relevant studies, c) study selection, d) charting the data e) collating, summarizing and reporting the results [34].

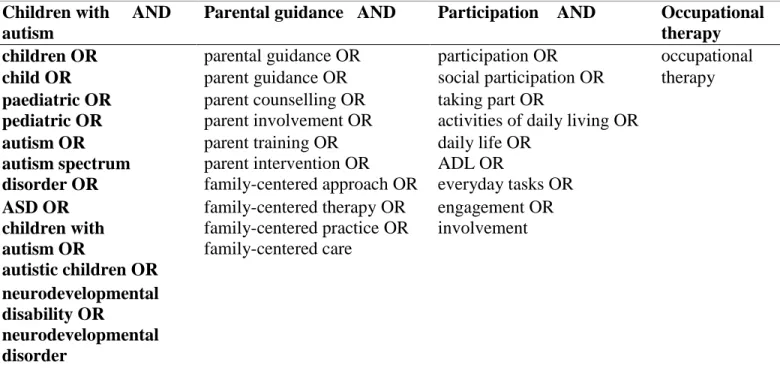

Literature search and selection of articles

In a scoping review, the search must be as comprehensive as possible. The aim is to find relevant studies (published and unpublished) that answer the research question [34]. The following

databases were used for searches: The Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED), the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and MEDLINE. These databases were used because they are prominent and relevant sources in occupational therapy research [28]. The search additionally included hand searches and reference list searches to make sure all the important articles were found [34]. A librarian of Jönköping University was

consulted. Search words were defined so that each component of the research question was represented. Search terms were selected and tested, considering which terms are likely to produce the best and most comprehensive result for the study. Search terms and synonyms are described in Table 1. Search words were combined by using the Boolean operator ‘AND’, and synonyms were combined using the Boolean operator ‘OR’. Endnote was used for data management.

Table 1. Search terms and synonyms

Children with AND autism

Parental guidance AND Participation AND Occupational therapy

children OR parental guidance OR participation OR occupational

child OR parent guidance OR social participation OR therapy

paediatric OR pediatric OR

parent counselling OR parent involvement OR

taking part OR

activities of daily living OR autism OR autism spectrum disorder OR parent training OR parent intervention OR family-centered approach OR daily life OR ADL OR everyday tasks OR ASD OR children with autism OR autistic children OR family-centered therapy OR family-centered practice OR family-centered care engagement OR involvement neurodevelopmental disability OR neurodevelopmental disorder

Relevant studies were selected using inclusion and exclusion criteria. Articles had to meet the following inclusion criteria: published between the years 2000 and 2019; English language; both abstract and full article available; had studies including children under 18 years with ASD and with parental guidance in occupational therapy aimed at influencing participation in everyday activities. The studies were excluded if a majority of participants had a diagnosis other than ASD; the participants were adults; the occupational therapist was not involved in the implementation of the intervention; the study did not fall within the scope of occupational therapy; or the study was not related to participation. The results of the search were reviewed and duplicates removed. Initial selections were made based on titles and abstracts while considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Selected full-text articles were reviewed in more detail for their content (see Appendix C). Different levels of evidence were included in the study to gather the most extensive data possible. The results of the search process are presented in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram [36]. Records identified through database searching (N=742) Ide nti fic ati on Additional records through other sources

(N=4)

Records after duplicates removed (N=560)

Records screened by title

(N= 560) Records excluded by title (N = 363)

Records screened by abstract (N=197)

Records excluded by abstract (N=169)

Full-text articles assessed for eligibility (N=28)

Studies excluded, with reasons (N=18)

Children lacked ASD diagnosis, OT´s were not involved in the interventions, and participation perspective was missing, not relevant content, studies were reviews. Studies included in scoping review (N=10) S cre ening Eligi bil it y Inc luded

The review resulted in a total number of 746 criteria-fitting articles. A total of 186 duplicates were removed, and 560 articles remained. Records were excluded by title (N = 363) and abstract (N = 169), and a full-text review was implemented for 28 articles. Finally, ten studies were selected, as they met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The articles were read several times at this stage to examine their contents in more detail. The material was sifted, charted, and sorted considering the key issues, themes, and similar processes [34]. The information was changed to a form that would be more understandable for a reader. Data was collected from research articles and entered in a data charting form, as seen in Table 2. The included studies were reported, analysed, and organized into groups according to their study designs and the nature of the results. The data charting phase dealt with the processing of the following data: first author, year,

location, intervention type, study populations, aims of the study, methodology, outcomes, and results. A scoping review provides an overview of all material reviewed [34].

The selected studies' content was examined in more detail in the next step, and

descriptions and keywords describing parental guidance were sought from the studies (Appendix B). Key factors and descriptions were coded in different colours. By extracting key factors, an attempt was made to determine parental guidance's key elements (Appendix B, Table 3). Similar themes emerged in the material. Descriptions of parental guidance were grouped according to their contents, and eventually, three themes (key elements) were formed [37]. Key elements describe parental guidance (what it consisted of, what was done) to promote child participation. The selected articles are described in Table 2. The key elements of parental guidance are

Results

Description of selected studies

Ten selected studies were published between 2011 and 2019 (Table 2). The results

included an analysis and comparison of the selected studies and their content [28]. A total of five countries were represented in the studies. A majority of the studies were conducted in the United States of America (USA) (n = 4) and England (n = 3). Certain studies had been conducted as well in Canada (n = 1), Iran (n = 1), and Korea (n = 1). A majority of the studies were quantitative. Only one of the selected studies was qualitative, and two studies used both qualitative and quantitative methods. The number of participants (children with ASD) varied from one to 51 participants in the studies. In five studies, the number of participants was 10 or less. All participants were under 13 years of age and had been diagnosed with autism except for one participant who had a diagnosis of Angelman Syndrome. However, this study was selected because of its content, and the majority (4/5) of the participants were autistic. A majority of all the participants were boys. Parents, generally the mother, were involved in the implementation of the intervention in all studies. The amount of guidance received by parents varied between four and 21 sessions. In one study, parental guidance was implemented through teletherapy [44], and another study was conducted entirely as group meetings [47]. In a majority of studies, parents received individual coaching and advice.In two studies, parents participated in a group meeting or lecture [43, 45]. One study using the DIR/Floortime intervention was also selected for the study. The DIR/Floortime intervention aims to promote children's linguistic, cognitive, emotional and social skills.The study was included because this approach relates to important occupations, such as play and daily activities, which are pursued by promoting the child’s skills [43].

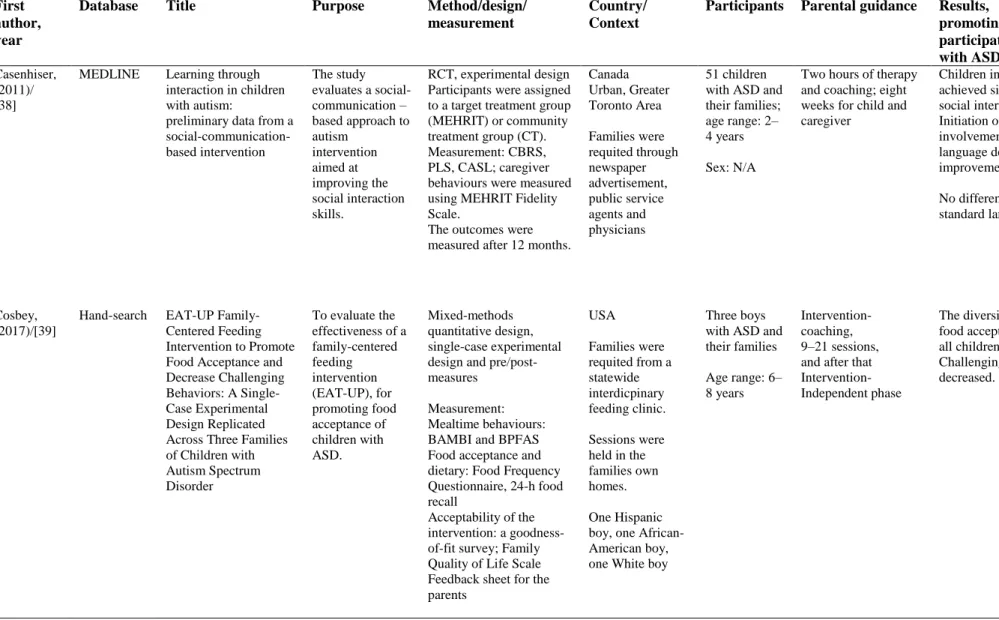

Table 2. Data charting form. Selected studies. First

author, year

Database Title Purpose Method/design/

measurement

Country/ Context

Participants Parental guidance Results, promoting the participation of children with ASD Casenhiser, (2011)/ [38]

MEDLINE Learning through interaction in children with autism:

preliminary data from a social-communication-based intervention The study evaluates a social-communication – based approach to autism intervention aimed at improving the social interaction skills. RCT, experimental design Participants were assigned to a target treatment group (MEHRIT) or community treatment group (CT). Measurement: CBRS, PLS, CASL; caregiver behaviours were measured using MEHRIT Fidelity Scale.

The outcomes were measured after 12 months.

Canada Urban, Greater Toronto Area Families were requited through newspaper advertisement, public service agents and physicians 51 children with ASD and their families; age range: 2– 4 years Sex: N/A

Two hours of therapy and coaching; eight weeks for child and caregiver

Children in the MEHRIT-group achieved significantly more social interaction skills. Initiation of joint attention, involvement and severity of language delay were related to improvement of language skills. No differences were found in standard language assessments.

Cosbey, (2017)/[39]

Hand-search EAT-UP Family-Centered Feeding Intervention to Promote Food Acceptance and Decrease Challenging Behaviors: A Single-Case Experimental Design Replicated Across Three Families of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder To evaluate the effectiveness of a family-centered feeding intervention (EAT-UP), for promoting food acceptance of children with ASD. Mixed-methods quantitative design, single-case experimental design and pre/post-measures

Measurement: Mealtime behaviours: BAMBI and BPFAS Food acceptance and dietary: Food Frequency Questionnaire, 24-h food recall

Acceptability of the intervention: a goodness-of-fit survey; Family Quality of Life Scale Feedback sheet for the parents USA Families were requited from a statewide interdicpinary feeding clinic. Sessions were held in the families own homes. One Hispanic boy, one African-American boy, one White boy

Three boys with ASD and their families Age range: 6– 8 years Intervention-coaching, 9–21 sessions, and after that Intervention-Independent phase

The diversity of dietary and food acceptance increased for all children with ASD. Challenging behaviour decreased.

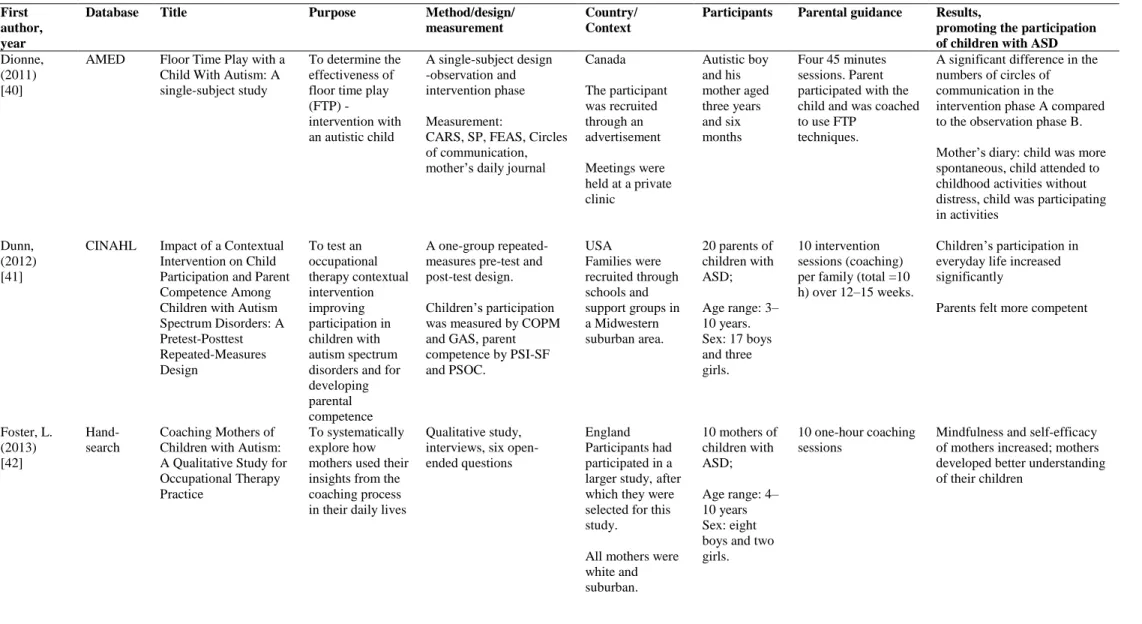

Table 2. Continued.

First author, year

Database Title Purpose Method/design/ measurement

Country/ Context

Participants Parental guidance Results,

promoting the participation of children with ASD Dionne,

(2011) [40]

AMED Floor Time Play with a Child With Autism: A single-subject study

To determine the effectiveness of floor time play (FTP) -intervention with an autistic child A single-subject design -observation and intervention phase Measurement:

CARS, SP, FEAS, Circles of communication, mother’s daily journal

Canada The participant was recruited through an advertisement Meetings were held at a private clinic Autistic boy and his mother aged three years and six months Four 45 minutes sessions. Parent participated with the child and was coached to use FTP

techniques.

A significant difference in the numbers of circles of communication in the

intervention phase A compared to the observation phase B. Mother’s diary: child was more spontaneous, child attended to childhood activities without distress, child was participating in activities

Dunn, (2012) [41]

CINAHL Impact of a Contextual Intervention on Child Participation and Parent Competence Among Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Pretest-Posttest Repeated-Measures Design To test an occupational therapy contextual intervention improving participation in children with autism spectrum disorders and for developing parental competence

A one-group repeated-measures pre-test and post-test design. Children’s participation was measured by COPM and GAS, parent competence by PSI-SF and PSOC. USA Families were recruited through schools and support groups in a Midwestern suburban area. 20 parents of children with ASD; Age range: 3– 10 years. Sex: 17 boys and three girls. 10 intervention sessions (coaching) per family (total =10 h) over 12–15 weeks.

Children’s participation in everyday life increased significantly

Parents felt more competent

Foster, L. (2013) [42] Hand-search Coaching Mothers of Children with Autism: A Qualitative Study for Occupational Therapy Practice

To systematically explore how mothers used their insights from the coaching process in their daily lives

Qualitative study, interviews, six open-ended questions

England Participants had participated in a larger study,after which they were selected for this study.

All mothers were white and suburban. 10 mothers of children with ASD; Age range: 4– 10 years Sex: eight boys and two girls.

10 one-hour coaching sessions

Mindfulness and self-efficacy of mothers increased; mothers developed better understanding of their children

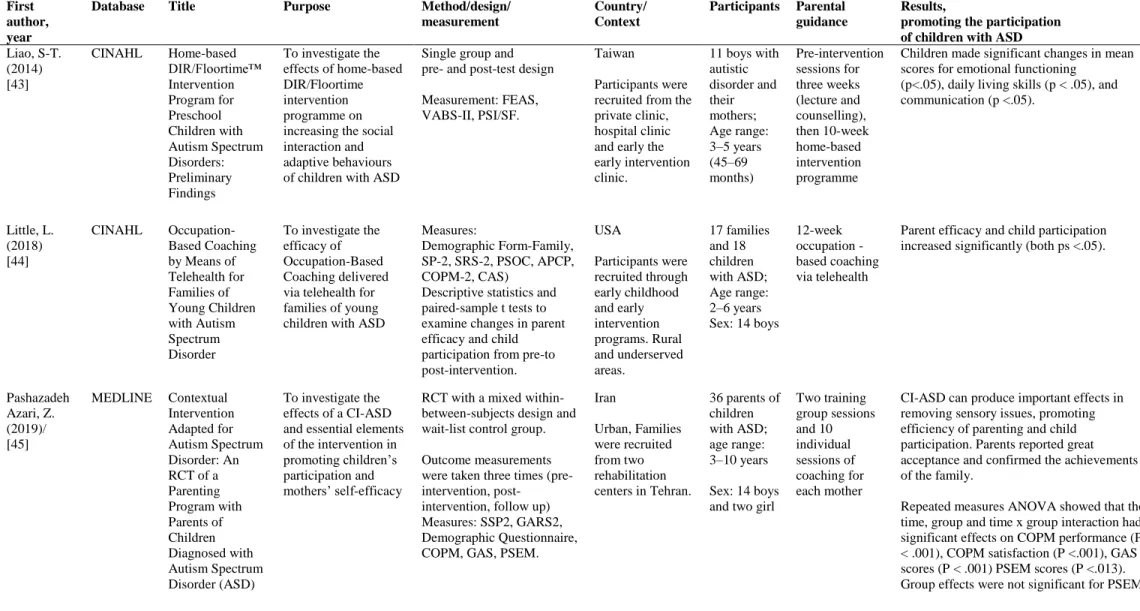

Table 2. Continued.

First author, year

Database Title Purpose Method/design/ measurement Country/ Context Participants Parental guidance Results,

promoting the participation of children with ASD Liao, S-T. (2014) [43] CINAHL Home-based DIR/Floortime™ Intervention Program for Preschool Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Preliminary Findings To investigate the effects of home-based DIR/Floortime intervention programme on increasing the social interaction and adaptive behaviours of children with ASD

Single group and pre- and post-test design Measurement: FEAS, VABS-II, PSI/SF.

Taiwan

Participants were recruited from the private clinic, hospital clinic and early the early intervention clinic. 11 boys with autistic disorder and their mothers; Age range: 3–5 years (45–69 months) Pre-intervention sessions for three weeks (lecture and counselling), then 10-week home-based intervention programme

Children made significant changes in mean scores for emotional functioning

(p<.05), daily living skills (p < .05), and communication (p <.05). Little, L. (2018) [44] CINAHL Occupation-Based Coaching by Means of Telehealth for Families of Young Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder To investigate the efficacy of Occupation-Based Coaching delivered via telehealth for families of young children with ASD

Measures:

Demographic Form-Family, SP-2, SRS-2, PSOC, APCP, COPM-2, CAS)

Descriptive statistics and paired-sample t tests to examine changes in parent efficacy and child participation from pre-to post-intervention. USA Participants were recruited through early childhood and early intervention programs. Rural and underserved areas. 17 families and 18 children with ASD; Age range: 2–6 years Sex: 14 boys 12-week occupation - based coaching via telehealth

Parent efficacy and child participation increased significantly (both ps <.05).

Pashazadeh Azari, Z. (2019)/ [45] MEDLINE Contextual Intervention Adapted for Autism Spectrum Disorder: An RCT of a Parenting Program with Parents of Children Diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) To investigate the effects of a CI-ASD and essential elements of the intervention in promoting children’s participation and mothers’ self-efficacy

RCT with a mixed within-between-subjects design and wait-list control group. Outcome measurements were taken three times (pre-intervention,

post-intervention, follow up) Measures: SSP2, GARS2, Demographic Questionnaire, COPM, GAS, PSEM.

Iran Urban, Families were recruited from two rehabilitation centers in Tehran. 36 parents of children with ASD; age range: 3–10 years Sex: 14 boys and two girl

Two training group sessions and 10 individual sessions of coaching for each mother

CI-ASD can produce important effects in removing sensory issues, promoting efficiency of parenting and child participation. Parents reported great acceptance and confirmed the achievements of the family.

Repeated measures ANOVA showed that the time, group and time x group interaction had significant effects on COPM performance (P < .001), COPM satisfaction (P <.001), GAS scores (P < .001) PSEM scores (P <.013). Group effects were not significant for PSEM

Table 2. Continued.

First author, year

Database Title Purpose Method/design/ measurement

County/ Context

Participants Parental guidance Results,

promoting the participation of children with ASD

Sun-Young, (2016) [46]

AMED Parent Training Occupational Therapy Program for Parents of Children with Autism in Korea To examine the effectiveness of the parent training and gauged parent’s perceptions and experiences of a more family-centered approach to therapy

A mix of quantitative and qualitative data collection and analysis

Measurement: COPM, semistructured interview, six open-ended questions

Republic of Korea Participants were recruited from the HOPE Center. Confucian traditions strongly influence hierarchical roles, including occupational therapy. Four parent-child dyads; children with severe autism Sex: three boys and one girl

At least 20 sessions of parent training, 1h/week for five months

Meetings included interaction learning sessions and hands-on training

The occupational

performance of parents and children was improved through training.

Improvements in self-efficacy of parents. Improvements in COPM scores were clinically significant. Willis, (2016)/ [47] CINAHL My Social Toolbox: Building a Foundation for Increased Social Participation Among Children with Disabilities My Social Toolbox aims to build a foundation for increased social participation among children with disabilities

Mixed method design, quantitative and qualitative data were gathered simultaneously (A doctoral capstone project)

Pre-and post-test measures PEM-CY, COSA, a Parent Social Participation Pre-Test/Post-Test Questionnaire, GAS USA Participants were recruited through Orange School and Orange Education Network Program was conducted at the Orange Inclusive preschool or Cuyahoga Public Library Five parents and five children with disabilities; 4/5 were diagnosed with ASD, 1/5 had Angelman Syndrome Age range: 7– 13 years, Sex: five boys

Four group parent training sessions, each session 1h

Parent’s awareness of the importance and benefits of social participation increased during the programme. Programme helped parents to socially support their respective children.

The results revealed three key elements in parental guidance that promoted the

participation of children with ASD in everyday life activities (Table 3, Appendix B): 1. increasing knowledge and awareness of the parents, 2. new practices and changes in the daily life of the families with ASD children, and 3. supporting and strengthening parenting.

Increasing parental knowledge and awareness through guidance

One essential purpose of parental guidance was to increase knowledge to ensure that parents could more ideally support their children in their daily lives and promote participation in daily activities (Table 3). The content and emphasis of the parental training varied among studies. Parental guidance increased parent awareness aboutASD, social participation, and a child’s ability to function [42, 46, 47]. Parental guidance further provided information on a child’s strengths and interests [38, 42, 46]. The goal was to increase parents’ knowledge and discuss the importance of daily life routines as well as the importance of social interaction and skills in promoting a child’s balanced everyday life and well-being [38, 40-47]. Occupational therapists shared their expertise, and parents were educated about sensory processing, behaviour

management, social life, the implementation of various interventions, available resources, and understanding the meaning of occupations [38-47].

Occupational therapists helped parents to adopt different ways to promote the child’s functioning. Increasing parental knowledge was necessary to understand and be more aware of a child’s abilities, individual needs, activities and behaviours, and the importance of participation for the ASD child’s development and well-being. Increased knowledge of the child's

development, the effects of ASD and various interventions were vital issues supporting the child's involvement in everyday life activities. Studies described that parental guidance could change parents ’attitudes and practices in their daily lives with children. Through parental guidance,

parents can become better facilitators of child participation [38–47].Although positive results were reported, selected studies' results cannot be generalized due to small sample sizes, limitations of study methods, and study designs. Six studies had less than 12 participants. One single-subject study was also included.

New practices and changes in the daily life of families

Another critical element of parental guidance was enabling new practices and the implementation of changes in everyday life, routines, and parents’ ways of working with their children (Table 3).One key issue that emerged from the selected studies was setting goals collaboratively with an occupational therapist [39, 41, 43, 44-47]. Goals were set to meet the needs of families and guided the direction of the intervention. Parents were further taught

different strategies for guiding their children in everyday life [38, 40, 43, 45-47] and encouraged to implement strategies independently [39]. Parents found different ways to cope and implement new practices in their daily lives, such as eating, dressing, attending events and transitions [41, 47]. Parents found new ways to support children with ASD while taking into account a child’s challenges and strengths. The results suggest that parental guidance could provide new

perspectives, ways to promote interaction and play, and ways to support child development and participation [38–47]. After receiving guidance, parents may be able to apply what they have learned in practice.

Parental guidance and changes in parental practices increased and improved the diversity of activities in which a specific child participated, such as play, daily activities and acting in a child-led way [40, 43- 45]. Parents were able to support a child’s development with more awareness as well as find new satisfying occupations for their children [40, 41]. The increase in participation due to new practices was reflected in children becoming more attentive and

involved in interactions and daily tasks [38-44, 46]. Children experienced more enjoyment when interacting with parents, and there were positive changes in the interactions [38, 43]. Parents’ new ways of behaving in daily life may improve children’s functioning and participation [38-47]. Unfortunately, due to the small sample sizes and the limitations of the research methods and designs, the results cannot be generalized.It should also be noted that the studies may have involved mainly change-friendly and motivated parents.The results then do not apply to other parents of children with ASD.

Supporting and strengthening parenting

The third important issue that emerged was supporting and strengthening parenting (Table 3). Parental coping and resilience played a key role in promoting the daily lives of children with ASD [41,42,47]. Parents' sense of empowerment and a sense of well-being contributed to children's participation [41, 42]. Parental guidance(including increased knowledge, practical guidance, joint goal setting, learning new strategies, support, reflective discussions) provided support to parents and increased confidence in their ability to cope with everyday life [39, 41-43, 47]. Parental support, better awareness of the child's strengths and interests, joint reflection, collaboration and strategy planning together, and feedback received promoted parental self-efficacy [41, 42, 44-46]. Parents felt more competent to implement different strategies with their children [39, 42, 43, 47], were less distressed [41], and intervention increased parent’s

mindfulness [42]. Activities with children brought joy to the parents [40]. The support, collaboration, new knowledge, and skills gained through parental guidance can help parents become empowered and use their resources ideally to promote children’s participation.However, generalizations cannot be made due to the small sample sizes of the selected studies and the limitations associated with the study designs.

Table 3. The key elements of parental guidance and the influence on child’s participation.

Study author

The key elements of parental guidance

The influence

on ASD children’s participation in everyday life activities

Casenhiser, D. M. et al. (2011). [38]

The goal was to assess the child’s individual challenges and strengths (speech, communication, sensory, cognitive, and motor abilities) and educate parents to consider them Plan strategies for the child and the

family

The overall quality of children’s social interaction improved

Children experienced more enjoyment in interacting with parents

Children were more involved in interactions, they started more joint attentional frames and they were more attentive

Caregivers’ improvements helped to improve the child’s functioning

Cosbey, J. et al. (2017). [39]

The goal was to coach parents to increase food acceptance

The coaching continued for so long that the parent was able to implement intervention strategies independently Strategies – demonstration, verbal

instructions, visual support, emphasizing the importance of interaction

Food acceptance increased, and children were eating age-appropriate portions of food One child regularly stayed at the dinner table,

and his functional communication increased The challenging behaviour of all children

decreased

Dionne, M. (2011) [40]

OT taught floor time play (FTP) intervention methods to mother:

demonstrating the interaction pattern; the parent was encouraged to interact with the child and use strategies to maintain interaction with the child

The parent received guidance during play

The numbers of circles of communication (Coc) increased significantly

(Coc refers to a reciprocal communication) Child accepted new playing partners and new

playing contexts; communication was more spontaneous; the child participated in the childhood activities without distress

Dunn, W. et.al. (2012) [41]

The intervention and coaching included three elements: sensory processing patterns, activity settings and daily life routines

Goals were formulated to meet the needs and interests of families

Therapists used reflective questions, provided information and support, and participated in the design of family strategies

Children’s performance increased significantly (Canadian Occupational Performance Measure [COPM] and Goal Attainment Scaling [GAS]); they participated more in their everyday lives Families found workable ways to cope with

their daily lives

Parents were less distressed, and parental efficacy improved

Parents felt more competent in their family lives

Foster, L. et. al. (2013) [42]

Counselling sessions discussed family life and the child’s strengths and interests

Coaching provided information on evidence-based interventions (sensory processing and community services) and ASD

Mothers had an improved understanding of their child and the issues that affected the child’s functioning

Intervention increased mothers' mindfulness and self-efficacy

Table 3. Continued.

Liao, S-T. et.al. (2014), [43]

Mothers were trained to use the DIR/Floortime intervention programme The aim was to train mothers to notice

the child's cues, to act in a child-led way, and to implement play strategies in a way that supported the child's development

Planning goals and home programmes collaboratively

Children progressed in two-way

communication and relationship forming Children’s adaptive functioning, daily skills

and communication skills improved The intervention influenced children’s

behaviour, and the children made progress in problem-solving

Positive changes in parent-child interaction Little, L.

et.al. (2018) [44]

Occupation-based coaching included support for caregivers, creating strategies for everyday life, supporting interaction, and giving feedback and reflective ideas Coaching considered the everyday

environment

Children’s participation increased significantly The intervention increased the diversity of

activities in which the child participated The intervention increased play activity and

skill development diversity

Parental efficacy increased significantly

Pashazadeh Azari. (2019), [45]

Parent training aimed to help to recognize strategies for improving a child’s participation and achieving functional goals

Training included coaching, knowledge about sensory processing, and social support

The coach guided parents in planning strategies while considering the child, the environment, and activities to promote participation in daily life

Clinically meaningful increase in child participation (outcome measures – Canadian Occupational Performance Measure [COPM], COPM satisfaction and Goal Attainment Scaling [GAS])

A significant improvement in parenting efficacy

Sun-Joung, L.A. (2016) [46]

The training included learning sessions and hands-on training

The training highlighted cooperation, dialogue, identifying strengths and challenges, and setting goals

The training promoted the occupational performance of children and parents

Parents received new information about their own child and his or her needs as well as the child’s development in general

Parental self-efficacy improved Willis, B.

(2016) [47]

The programme addressed the benefits of social participation

Parents were educated about local resources

The training included education on intervention strategies to improve social skills

Parents' perception of the importance and benefits of participation increased Parents felt more competent to implement

social interaction strategies with their child Parents appreciated peer support

Table 3. Describes the key elements of parental guidance, how the participation of children was strengthened, and what role parents played as enablers of children’s participation.

Discussion

This scoping study described key elements of parental guidance in occupational therapy in order to promote the participation of children with ASD in everyday activities. The results of the selected studies were organized thematically and eventually divided into three groups that were essential elements in promoting participation: increased knowledge and awareness from parents, new practices and changes in everyday life, and supporting and strengthening parenting [34]. The findings of this study suggest that parental guidance is an important and central factor in promoting the participation of children with ASD in everyday activities, as parents are involved in children’s daily lives and can influence a child’s natural environment. Parents additionally have the desire and opportunity to make children’s daily lives smoother, richer, and more inclusive [48]. Influencing parents is crucial because it can be difficult for children with ASD to express their desires and goals and implement these desires in their lives.

The results were consistent with the results of other studies. It has been stated that parental guidance can increase strategies for coping with everyday life [18], help mothers to reach occupational performance goals for their children and themselves [18], and promote child participation [49].In this study, increasing parental knowledge and new behaviours were essential elements influencing a child’s functioning and participation. These factors were consistent with Ogourtsova’s [50] findings, which showed that affecting parental function and improving parental outcomes additionally had a positive effect on a child’s development [50]. It has been shown that parental coaching or training is an effective way to improve the educational outcomes of children at risk for developmental delays [51] and increase a child’s

can have a broader and long-lasting impact on a child’s various life situations [52, 53]. The results of this study were in accordance with these findings.

Perhaps one of the fundamental forces for change to make events happen in daily life is the promotion of participation, and making everyday life simpler is a common goal to which the entire family is committed. Interventions targeting the child alone would probably not be

sufficient to bring about change in daily life and the home-environment. Parental involvement is necessary for a child to generalize learned skills [1]. The findings suggest that insights

experienced by parents, increased knowledge and skills, increased understanding of their child, and, simultaneously, the emotional support parents experience seem to be the medium through which changes in everyday life are possible. It has been stated in the occupational therapy literature that the involvement of parents and family is a crucial element in the effective practice of paediatric occupational therapy [3, 6].

According to the occupational therapy frame of reference of the MOHO, change processes involve complex processes of change in volition, habituation, and performance

capacity. The MOHO describes the importance of taking into account familial daily routines and patterns of actions guided by habits and roles [27], as aspect which emerged in the results of this study as well. In many selected studies, the goal was to increase parents’ ways of coping in everyday life to promote the participation of the child, which required reviewing the family’s current practices and habits.This increased the awareness of the current situation, and the need for change enabled transformations in the family’s daily life [27, 38-47]. The volitional approach was present under the guidance of parents on an ongoing basis. The parents' guidance sought to take into account the interests and feelings that the parents had during the intervention.

with them. With the support, increased knowledge, and means provided by the therapist, parents were supported toward goals they considered essential and meaningful to them [27, 38-47].

One of the key findings of this study, which was consistent with previous research findings, was the need to support parenting as well as parents’ self-efficacy and coping through guidance [54, 55]. A person who feels capable and effective searches for opportunities, uses feedback to improve performance, and strives to achieve goals with perseverance [27]. Parental well-being further promotes the participation of children. It is known that parents of children with ASD experience more intense stress in their daily lives than other parents; parental support and empowerment is vital for children’s well-being and the promotion of everyday activities [56, 57]. Therefore, supporting parental coping should generally be considered in occupational therapy for ASD children and may occasionally receive less attention in the child’s therapy process.Parental guidance can increase parental self-efficacy because it increases knowledge about a child’s

behaviour, desires, and needs [56]. In line with the MOHO’s process of change, parents were able to achieve, as a result of a dynamic process of motivation, habits, and performance capacity, a new internal organization, which can lead to new ways of thinking, feeling, and acting in families daily lives [27, 38-47]. On the other hand, due to the studies' small sample sizes and the varying study designs and measures used in them, it is challenging to interpret and generalize the results. The selected studies could have described in more detail how parents were motivated to change and why parents wanted to participate in interventions and find tools to promote everyday life participation.

The selected studies showed that parental guidance was influenced by the cultural environment and perceptions of ASD. For example, Sung-Joung [46] states in her study that, in Korea, ASD is associated with a stigma that makes it difficult for a family to, for example, attend public events or visit a restaurant. Although parents can be mentored, and their ability to function

with the ASD child improves, parental guidance cannot change the cultural and social attitudes surrounding the family.This is important to consider for parental guidance in occupational therapy. Additionally, families’ everyday habits and routines significantly influence the daily lives of children with ASD and the realization of change in everyday life [45, 46]. This is important to take into account in the practical work of occupational therapists, as the success of interventions requires the commitment of parents [6]. Parents can additionally continue to rely on the views of professionals, and making independent daily decisions can occasionally be

challenging, including when encouraged by an occupational therapist [46].In occupational therapy practice, it is further important to keep in mind that, as parents take more responsibility for their child’s rehabilitation in the daily environment, this responsibility should not be

excessively overburdensome.

One fundamental shortcoming in this study was the lack of children’s perspectives on participation. In many studies, the experiences of children were not described. The opinions of children with ASD may be challenging to ascertain, but the experience of participation is

nonetheless the child’s experience. Children’s interests, values, and personal causation play a crucial role in participation [58]. It is essential to consider the enjoyment that the activity produces because this enjoyment is related to participation [59] and supports children’s

successful engagement in activities [60]. The question arises as to how important it would be to know what motivates a child with ASD to participate. The lives and activities of children with ASD are frequently viewed through the eyes of other individuals, generally adults. In the future, it would be necessary to study children’s own experiences of participation and how their

motivations affect everyday life. It would be essential to know how children experience, for example, the changes in their daily lives that result from the guidance of their parents.

how to bring out a child’s perspective. This study aimed to increase knowledge to improve the participation of children with ASD. It is one way to improve the equal rights of ADS children, which is one crucial approach and topic that could be explored further.

Strengths and limitations

In literature reviews, the main limitations generally involve the desire to publish positive research results, the variety of studies, and the quality of these studies [28]. In this study, following the scoping review methodology, the quality of the selected studies was not thoroughly assessed using specific assessment tools, which was useful to take into account when interpreting the results. The selected studies further differed widely. Both qualitative and quantitative studies were included. Moreover, the numbers of participants in the studies varied considerably.

Compiling the results together posed challenges because the results of the studies were presented in many different ways. These challenges may have had a detrimental effect on the clear

presentation of the results of the study. Additionally, only English-language studies were selected for this study, which may have resulted in the exclusion of several important studies.

During the search process, the author’s personal and professional background may have influenced the review findings [61]. Parental guidance and participation were considered only from the perspective of occupational therapy, as the author is an occupational therapist. The review of selected studies and results could have gained new perspectives if they had been studied from a more psychological perspective than was used by, for example, utilizing psychological background theories. The results highlighted parental support and resilience in guidance, and these elements could have been explored in more depth. Additionally, the author is inexperienced as a researcher. Transparency was sought throughout the process by accurately describing the various stages of the study to ensure that the reader could follow the progress of

the research process and the factors that influenced it [61]. A detailed description of the research process further allows for the study to be repeated as needed.

Ethical considerations

There was no direct contact with participants during the scoping review. The purpose and scope of the review as well as the potential benefits for the different stakeholders were considered. In general, from a societal point of view, it is important to be aware of the benefits of occupational therapy interventions. By exploring the potential positive and negative effects of this study, the findings will benefit occupational therapists in clinical practice [61]. This study summarized available and relevant research on this topic and provides knowledge to support the clinical work of occupational therapists [28, 34]. Additionally, children with ASD and their parents will benefit from this study, as it provides information on key elements that promote children’s participation [61]. Nevertheless, since the research concerned children under the age of 18, young adults with ASD were excluded from the target group. Young adults with ASD are likely to experience similar challenges in their ability to perform and participate in their daily lives and would, therefore, benefit from the exploration of the benefits of parental guidance as well. The possible funding backgrounds of the selected studies were considered [61].

Conclusion

Due to the difficulties children with ASD experience in participating in their everyday lives, it is essential to raise awareness and spark a discussion on how parental guidance can support children in their daily lives. This study suggests that parental guidance is the key to increasing parental knowledge, coping in daily life, finding new ways of functioning with ASD children, and finding

parenting support. Parents benefit from support that allows them to more effectively identify their children’s individual needs, set everyday goals, achieve new everyday strategies, and gain the self-confidence needed to change their daily lives. Parents have a central role as enablers and facilitators of children’s participation, making the involvement of parents invaluable. Parenting should be seen as a critical resource in supporting the participation of ASD children, as they have the opportunity to carry out child support interventions at home if provided with adequate

support. The ideal way to support ASD children’s participation is to work with parents as a unit with the common goal of facilitating family and child functioning. One critical benefit of parental guidance is its potential cost-effectiveness, which enables support for as many ASD children as possible. The affordability of services further makes parental guidance societally important. It is hoped that this study will generate future interest in exploring the reasons why and how parents are motivated to guidance as well as how ASD children’s own experiences might be more effectively brought to the fore.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The author confirms that there is no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Frida Lygnegård, the supervisor of the thesis, and Margareta Hjort, the librarian, for their help and support during the completion of this thesis.

References

[1] Ingersoll B, Dvortcsak A. Including parent training in the early childhood special education curriculum for children with autism spectrum disorders. J. Posit. Behav. Interventions. 2006;8(2):79-87.

[2] Shields N, Synnot, A. Perceived barriers and facilitators to participation in physical activity for children with disability: A qualitative study. BMC Pediatr.

2016;16(9):1-10.

[3] Jaffe L, Humphry R, Case- Smith J. Working with families. In Case-Smith J, O´Brien, J, editors. Occupational Therapy for children. 6th ed. Missouri (MO): Mosby; 2010. p.108-123.

[4] American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). 5th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [5] Kiviranta T, Sätilä H, Suhonen-Polvi, H, Kilpinen-Loisa, P, Mäenpää, H. Lapsen ja

nuoren hyvä kuntoutus. [Good rehabilitation of a child and young person]. Suomen lastenneurologinen yhdistys. [Finnish Pediatric Neurology Association]. 2016. Finnish.

[6] Case-Smith J. Systematic review of interventions to promote social-emotional development on young children with or at risk for disability. Am J of Occup Ther. 2013;67(4):395-404.

[7] Dunn W. Best practice occupational therapy for children and families in community settings.2nd ed. Thorofare (USA): SLACK Incorporated; 2011. Chapter 1, Best practice philosophy for community services and families; p. 1-12.

[8] Ratcliff K, Hong, I, Hilton C. Leisure Participation Patterns for School Age Youth

with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Findings from the 2016 National Survey of

Children’s Health. J Autism and Dev Disord. 2018; 48(11):3783-3793. [9] Kaljaka S, Ducic B., Cvijetic, M. Participation of children and youth with

neurodevelopmental disorders in after-school activities. Disabil Rehabil. 2018; 41(17):2036-2048.

[10] De las Heras de Pablo C, Fan CW, Kielhofner G. In Kielhofners Model of Human Occupation.5th ed. Philadelphia (USA): Wolters Kluwer; 2017. Chapter 8,

Dimensions of doing; p. 107-119.

[11] ICF. International classification of functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). Geneva: WHO; 2001.

[12] Hilton, C. L. In Case-Smith J, O´Brien J. Occupational therapy for children and adolescents.7th ed. Missouri (MO): Elsevier Mosby; 2015. p. 321-329.

[13] Bal VH, Kim SH. Cheong D, Lord C. Daily living skills in individuals with autism spectrum disorder from 2 to 21 years of age. Autism. 2015;19(7):774-784.

[14] Moilanen I, Mattila M, Loukusa S, Kielinen M. Autisminkirjon häiriöt lapsilla ja nuorilla. [Autism spectrum disorders in children and adolescents]. Finn Med J Duodecim. 2012;128(14):1453-1462.

[15] Miller-Kuhaneck HA. Occupational Therapy for Children and Adolescents. 7th ed. Missouri (USA) Mosby Elsevier; 2015. Chapter 27, Autism Spectrum Disorder; p. 766-785.

[16] Solish A, Perry A, Minnes P. Participation of children with and without disabilities in social, recreational and leisure activities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil.

2010;23(3):226–236.

[17] Wilcock AA, Hocking C. An Occupational perspective of health. Thorofare (NJ): Slack; (2015).

[18] Simpson D. Coaching as a family-centered, occupational therapy intervention for autism: a literature review. J Occup Ther Sch Early Interv. 2015;8(2):109-25. [19] Graham F, Rogers S, Ziviani J. “Coaching parents to enable children’s

participation: an approach for working with parents and their children.” Aust Occup Ther J. 2009; 56(1):16-23.

[20] Kaiser AP, Hancock TB. Teaching parents new skills to support their young children’s development. Infants and Young Child. 2003;16(1):9-21.

[21] Boyd BA, Odom SL, Humpherys B, et al. Infants and toddlers with autism spectrum disorder: Early identification and early intervention. J Early Interv. 2010;32:75-98.

[22] Dunn W, Cox J, Foster L, et al. Impact of a contextual intervention on child participation and parent competence among children with autism spectrum disorders: a pretest-posttest repeated-measures design. Am J Occup Ther. 2012; 66(5): 520-528.

[23] Bendixen RM, Elder JH, Donaldson S, et al. Effects of a father-based in-home intervention on perceived stress and family dynamics in parents of children with autism. Am J Occup ther. 2011; 65(6): 679-687.

[24] Montes GM, Halterman JS. Psychological functioning and coping among mother of children with autism: A population based study. Pediatr. 2007;119(5):1040-1046.

[25] Schieve, LA., Blumberg SJ, Rice, C.The relationship between autism and parenting stress. Pediatr. 2007; 119(1):114-121.

[26] Novak I, Berry J. Home program intervention effectiveness evidence. Phys. Occup. Ther Pediatr. 2014; 34(4): 384 - 389.

[27] Taylor RR, Kielhofner K., Model of Human Occupation. 5th ed. Philadelphia (USA): Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

[28] Taylor C. Evidence-based practice for occupational therapists. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2007.

[29] Cameron K, Ballantyne S, Kulbitsky A, et al. Utilization of evidence-based practice by registered occupational therapists. Occup Ther Int. 2006; 12(3): 123-136.

[30] Bennett S, Tooth L, McKenna K, et al. Perceptions of evidence-based practice: A survey of Australian occupational therapists. Aust Occup Ther J. 2003; 50(1): 13– 22.

[31] Wressle E, Samuelsson, K. The self-reported use of research in clinical practice: A survey of occupational therapists in Sweden. Scand J Occup Ther. 2015; 22(3): 226-234.

[32] Segal R, Beyer C. Integration and application of a home treatment program: A study of parents and occupational therapists. Am J Occup Ther. 2006; 60(5):500-510. [33] Hodgetts S, Nicholas D, Zwaigenbaum L, et al. Parents’ and professionals’

perceptions of family centered care for children with autism spectrum disorder across service sectors. Soc Sci Med. 2013; 96:138–146.

[34] Arksey H, O´Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005; 8(1): 19-32.

[35] Levac D, Colquhoun H, O´Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2020; 5(69): 1-9.

[36] PRISMA. Prisma. Transparent reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses [Internet]; 2015. [cited 2020 Febr 24]; Available from:

http://www.prisma-statement.org/.

[37] Grandheim, U, Lundman, B. (2003). Qualitative content analysis in nursing

research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse education today. 2003; 24: 105-112.

[38] Casenhiser DM, Shanker SG, Stieben J. London, England: SAGE Publications Autism: Int J Res Pract. 2011; 17(2): 220-241.

[39] Cosbey J, Muldoon D. EAT-UPtm Family-Centered Feeding Intervention to

Promote Food Acceptance and Decrease Challenging Behaviors: A Single-Case Experimental Design Replicated Across Three Families of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017; 47(3):564-578.

[40] Dionne M, Martini R. Floor time Play with a child with autism: A single-subject

study. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications. Can J Occup Ther. 2011; 78(3):196-203.

[41] Dunn W, Cox J, Foster L et al. Impact of a contextual intervention on child

participation and parent competence among children with autism spectrum

disorders: a pretest-posttest repeated-measures design. Am J Occup Ther, 2012;66 (5): 520-528.

[42] Foster L, Dunn W, Lawson L. Coaching Mothers of Children with Autism: A Qualitative Study for Occupational Therapy Practice. Inform Healthc Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2013:33(2):253-263.

[43] Liao S, Hwang YS, Chen YJ et al. Home-based DIR/Floortime ™ Intervention Program for Preschool Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: Preliminary Findings. Inform Healthc Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2014;34(4):356-367. [44] Little LM, Pope E, Wallisch A et al. Occupation-Based Coaching by Means of

Telehealth for Families of Young Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. Am J Occup ther. 2018;72(2):7202205020, 1-7.

[45] Pashazadeh AZ, Hosseini SA, Rassafiani, M. et al. Iran J Child Neurol. 2019;13(4): 19-35.

[46] Sung-Joung L. Parent Training Occupational Therapy for Parents of Children with Autism in Korea. Occup Ther Int. 2017;2017:1-8.

[47] Willis B. My Social Toolbox: Building a Foundation for Increased Social Participation Among Children with Disabilities [dissertation]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing; 2016.

[48] Case-Smith J, Arbesman M. Evidence-Based Review of Interventions for Autism Used in or of Relevance to Occupational Therapy. Am J Occup ther. 2008;62(4): 416-429.

[49] Dunn W, Cox J, Foster L et al. Impact of a contextual intervention on child participation and parent competence among children with autism spectrum

disorders: a pretest-posttest repeated-measures design. Am J Occup Ther. 2012;66 (5): 520-528.

[50] Ogourtsova T, O´Donnell M, SW. Health coaching for parents of children with developmental disabilities: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2019;61 (11):1259-1265.

[51] McCormic MC, Brooks-Gunn J, Buka SL et al (2006). Early interventions in low birth weight premature infants: Results at 18 years of age for the Infant Health and Development Program. Pediatr. 2006; 117(3):771-780.

[52] Bagby MS, Dickie WA, Baranek GT. How sensory experiences of children with and without autism affect family occupations. Am J Occup Ther. 2012; 66(1):78-86.

[53] Palisano RJ, Chiarello LA, King, GA et al. Participation-based therapy for children with physical disabilities. Disabil Rehabilit. 2012; 34(12):1041-1052.

[54] Karst J.S, Van Hecke AV. (2012). Parent and family impact of autism spectrum disorders: A review and proposed model for intervention evaluation. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev.2012;15(3):247–277.

[55] Sanders M, Woolley ML. 2005. The relationship between maternal self-efficacy and parenting practices: implications for parent training. Child: care, health Develop. 2005;31(1):65-73.

[56] Kuhn JC, Carter AS. Maternal self-efficacy and associated parenting cognitions among mothers of children with autism. Am J Orthopsychiatr. 2006;76(4):564–575. [57] Mori K, Ujiie T, Smith A et al. (2009). Parental stress associated with caring for

children with Asperger’s syndrome or autism. Pediatr Int. 2009;51(3):364–370. [58] Lee W, Kielhofner, G. (2017) Kielhofner’s Model of human occupation. 5thed

Philadelphia (USA): Wolters Kluwer; 2017. Chapter 5, Habituation: Patterns of Daily Occupations; p. 57-73.

[59] Eversole M, Collins DM, Karmarkar A et al. Leisure activity enjoyment of children with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism develop Disord. 2016;46(1):10–20. [60] Heah T, McGuire B, Law, M. Successful participation: The lived experience among

children with disabilities. Rev Can D’Ergother. 2007; 74(1):38–47.

[61] Suri, H. (2019). Ethical considerations of conducting systematic reviews in educational research. In: Zawacki-Richter O, Kerres M, Bedenlier S, Bond M, Buntins, K, editors. Systematic reviews in educational research. Methodology, perspectives and application, Germany (DE): Springer VS; p. 41-55.

[62] Brown JA, Woods JJ. Evaluation of a multicomponent online communication professional development program for early interventionists. J Early Interv. 2012;34(4): 222–242.

[63] Salisbury C, Cambray-Engstrom E, Woods J. Providers’ reported and actual use of coaching in natural environments. Top Early Child Special Educ. 2012; 32(2): 88– 98.

[64] Rush D, Shelden M. The early childhood coaching handbook. Baltimore (MD): Brookes; 2011.

APPENDIX A

Definition of the term parental guidance

Parental guidance – an umbrella term

In this study, parental guidance is understood as an umbrella term that describes the different methods used in the guidance process. Different definitions emphasize different means. Common to all these

methods is cooperation with parents and efforts to promote children’s and families’ daily lives.

Coaching Training, teaching Support, reflective discussions conversations sharing information

cooperation with parent and child joint planning

modelling

guidance and feedback

increasing parental knowledge and improve mastery

[18, 62-64]

Occupational performance coaching:

parents are guided in solving problems to achieve self-identified goals

to identify and implement social and physical environmental change

aims to promote occupational performance coaching relationship with parents

collaborative problem-solving family-centred

occupation-centred [19]

training and teaching parents to implement interventions at home teaching parents a

variety of intervention techniques

teaching parents’ new skills to advance a child’s skills

sharing information and advice

[1, 15, 18]

reflective guidance support during the

guidance process

listening [15, 22,26]

![Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram [36]. Records identified through database searching (N=742) Identification Additional records through other sources](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/5dokorg/4640183.120232/11.918.110.811.139.896/figure-prisma-records-identified-database-searching-identification-additional.webp)