Swedish university

brand personality and

student choice

How does the university brand personality influence international

students when selecting a higher education institution?

Case study: Jönköping University

MASTER THESIS WITHIN: Business Administration NUMBER OF CREDITS: 15 ECTS

PROGRAMME OF STUDY: International Marketing AUTHORS: Thi Thu Huyen Do & Veselin Ralev JÖNKÖPING, May 2021

Master Thesis in Business Administration

Title: How does the university brand personality influence international students when selecting a higher education institution?

Authors: Thi Thu Huyen Do & Veselin Ralev Tutor: Adele Berndt

Date: 2021-05-24

Keywords: University branding, Brand personality, Higher education, University choice, International students' choice, Decision-making process of students

Abstract

Background: There has been an increasing trend of more Swedish higher education institutions competing for international students in response to international student mobility trends, self-management and budget securement, and government-backed recruitment campaigns. An emerging stream of higher education research is brand personality, and it may represent a robust basis for differentiation between many universities competing for student recruitment. Therefore, the study was built to get a deeper understanding of the impact of university brand personality on international students' choices.

Purpose: Given the importance of brand personality for higher education institutions to deal with the international competition or differentiate themselves, the purpose of this study is to explore international student's perception of the university brand personality that affects the selection of a Swedish university.

Method: To address the purpose of the exploratory study, the qualitative research approach was applied, combining with interpretivism philosophy. Semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions were conducted with 11 international first-year students. By utilizing abductive reasoning, the data was analyzed and interpreted through thematic analysis.

Conclusion: Cosmopolitan is perceived as the most distinct brand personality dimension that Jönköping University (JU) possesses. Nevertheless, the degree of perception among foreign students regarding each brand personality dimension is different during the decision-making process. In the early stages, the potential students perceive prestige as the most distinct and significant dimension, followed by cosmopolitan. However, when the consumption process nears, cosmopolitan becomes an essentially more important dimension. Further, lively and sincerity are found to partly influence students' choice for higher education.

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, we would like to display our thankfulness to Ms. Adele Berndt for her professional support, practical guidance, and her constant desire to motivate and inspire us. Although this thesis was written in times of global pandemic without physical meetings, Ms. Berndt exercised effective supervision online and provided us with invaluable pieces of advice, for which we are truly grateful.

In addition, we would like to thank the participants that devoted time to helping us in our research. We appreciate your willingness to express your thoughts and your trust in us. The insights obtained in this research would not have been possible without your participation.

Further, to the other students in our seminar group, thank you for your constructive feedback and creative ideas which helped us see our work from a different perspective.

Moreover, we are particularly grateful to Jönköping University and for all the lecturers and employees that provided us with a high-quality education, constant support, and made that journey pleasant for us.

Last but not least, to our families and friends who believed in us and encouraged us through the difficulties we faced, thank you for being there for us!

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ... 1

1.1. Background ... 1

1.2. Problem Discussion ... 3

1.3. Purpose and Research Questions ... 4

1.4. Delimitations ... 5

1.5. Definitions of Key Terms ... 6

2. Theoretical Background ... 8 2.1. Brand ... 8 2.1.1. Brand Associations ... 8 2.1.2. Brand Identity ... 9 2.1.3. Brand Image ... 9 2.1.4. Brand Personality ... 10 2.2. University Branding ... 12

2.2.1. University Brand Identity ... 13

2.2.2. University Brand Image ... 14

2.2.3. University Brand Personality ... 15

2.3. The Decision-Making Process of Students ... 17

2.3.1. Need Recognition Stage ... 22

2.3.2. Information Search Stage ... 22

2.3.3. Evaluation of Alternatives Stage ... 23

2.3.4. Purchase and Consumption Stage ... 23

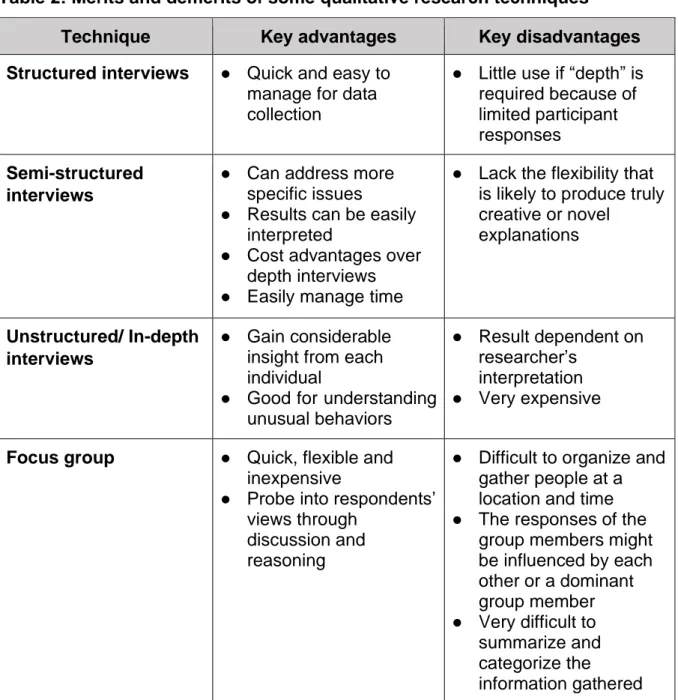

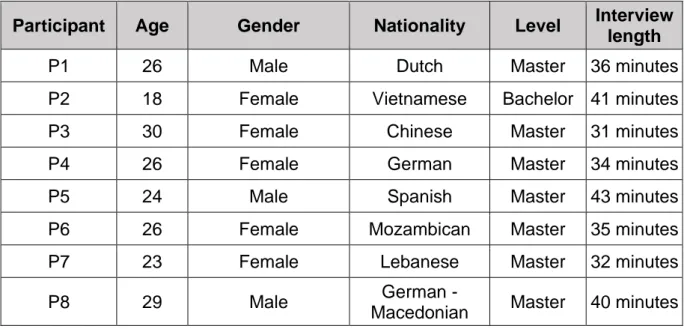

2.3.5. Post-purchase Stage ... 24 2.4. Conceptual Framework ... 24 3. Methodology ... 25 3.1. Research Philosophy ... 25 3.2. Research Design... 26 3.3. Research Approach ... 27 3.4. Data Collection ... 27 3.4.1. Semi-structured Interviews ... 29 3.4.2. Selection of Participants ... 29

3.4.3. Conduction of the Interviews ... 30

3.5. Data Analysis ... 30

3.6. Ethical Considerations ... 32

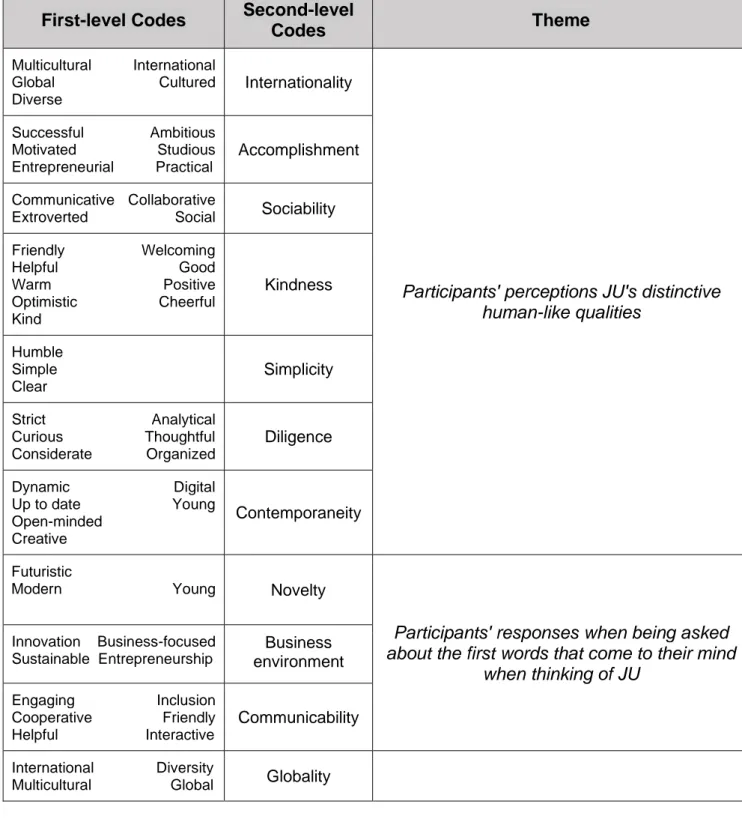

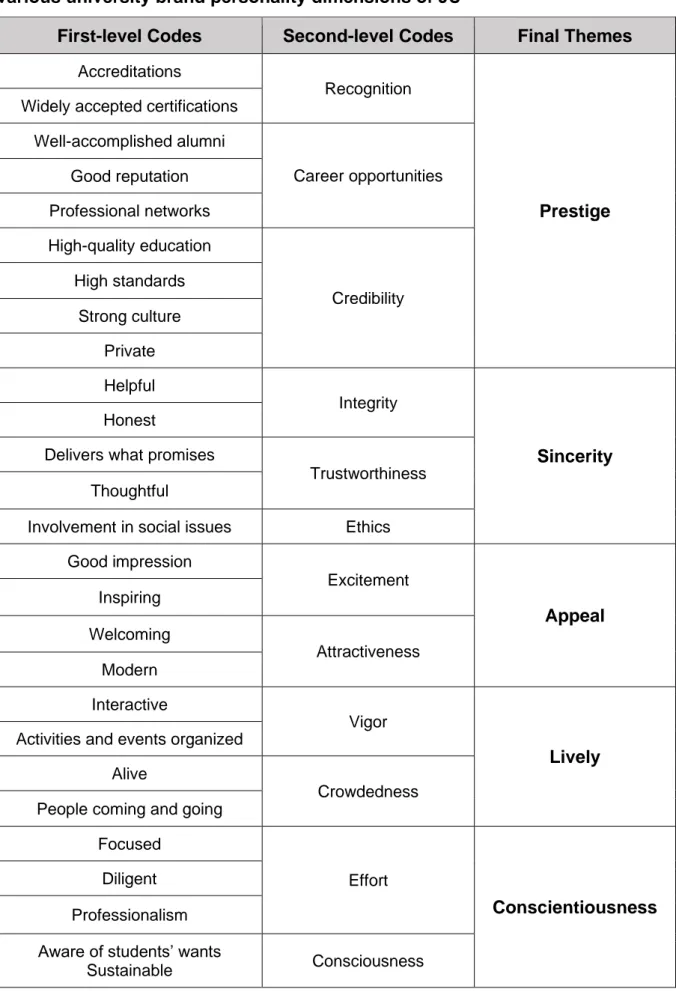

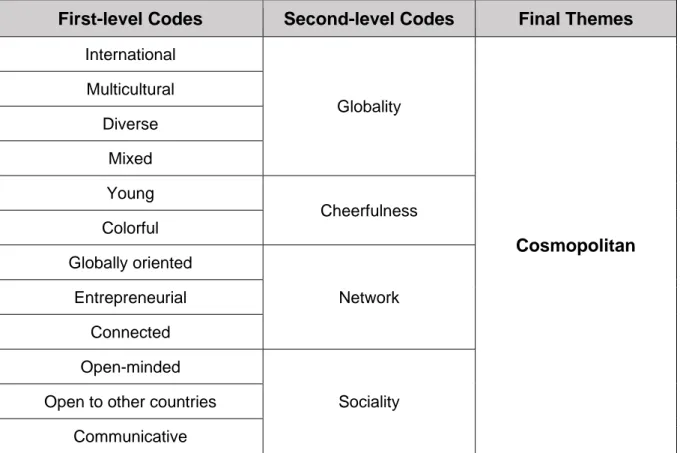

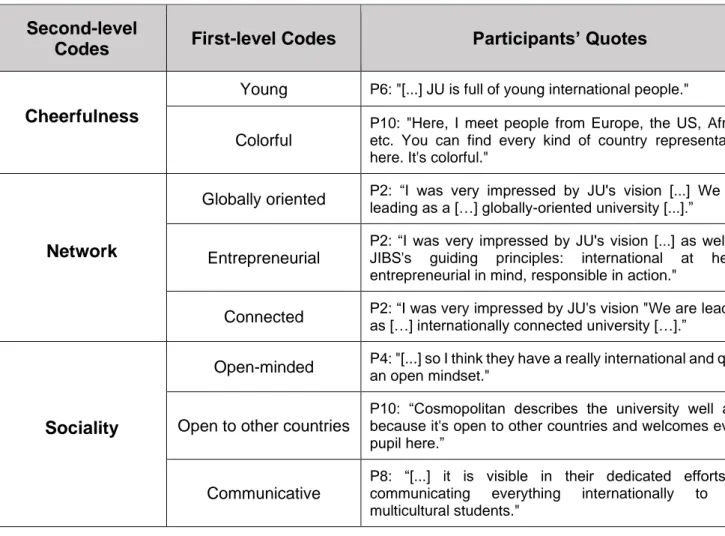

4. Empirical Findings and Analysis ... 36

4.1. Findings: Research Question 1 ... 36

4.1.1. Prestige ... 44 4.1.2. Sincerity ... 44 4.1.3. Appeal ... 45 4.1.4. Lively ... 45 4.1.5. Conscientiousness ... 46 4.1.6. Cosmopolitan... 47

4.2. Findings: Research Question 2 ... 48

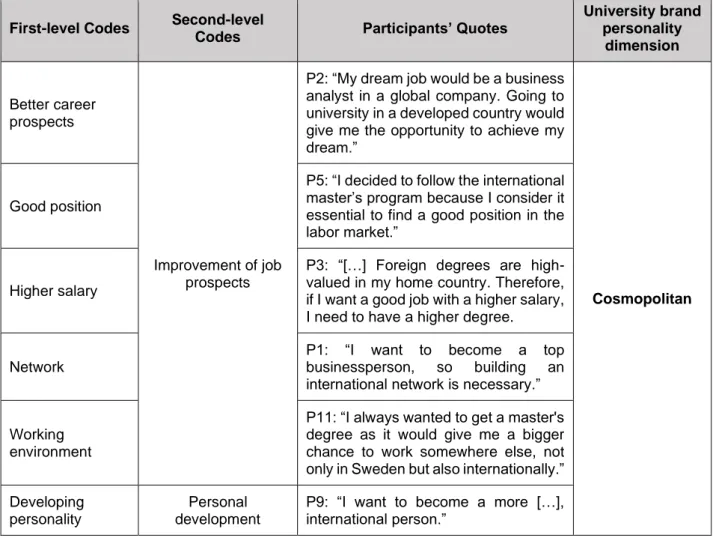

4.2.1. Need Recognition Stage ... 48

4.2.2. Information Search stage ... 51

4.2.3. Evaluation of Alternatives Stage ... 52

4.2.4. Purchase and Consumption Stage ... 56

5. Discussion ... 58 5.1. Research Question 1 ... 58 5.1.1. Prestige ... 59 5.1.2. Sincerity ... 60 5.1.3. Appeal ... 60 5.1.4. Lively ... 61 5.1.5. Conscientiousness ... 61 5.1.6. Cosmopolitan... 62 5.2. Research Question 2 ... 63

5.2.1. Need Recognition Stage ... 63

5.2.2. Information Search Stage ... 64

5.2.3. Evaluation of Alternatives Stage ... 64

5.2.4. Purchase and Consumption Stage ... 65

5.3. Connecting Research Question 1 and Research Question 2 ... 65

6. Conclusion and Implications ... 67

6.1. Research Purpose and Answering the Research Questions ... 67

6.2. Theoretical Implications ... 68

6.3. Managerial Implications ... 69

6.4. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research ... 69

REFERENCES ... 72

APPENDIX ... 85

List of Figures

Figure 1: Consumer buying decision process ... 20 Figure 2: Conceptual framework ... 24

List of Tables

Table 1: Comparing students’ decision-making process models ... 20 Table 2: Merits and demerits of some qualitative research techniques ... 28 Table 3: General information of the participants ... 29 Table 4: Data structure of participants’ perceptions of JU's human-like qualities and associations regarding the institution ... 37 Table 5: Data structure of participants’ perceptions on the applicability of the various university brand personality dimensions of JU ... 38 Table 6: Illustrative quotations of participants’ perceptions on the applicability of the various university brand personality dimensions to JU’s brand ... 39 Table 7: Illustrative quotations of participants’ perceptions on the most distinctly possessed brand personality dimension by JU ... 42 Table 8: Data structure of participants’ reasons to follow higher education ... 49 Table 9: Quotations of participants’ opinions on deciding to pursue higher education where university brand personality dimensions can influence their university choice ... 50 Table 10: Data structure of participants’ criteria when evaluating alternatives ... 53 Table 11: Quotations of participants’ evaluation criteria in terms of university brand personality dimension ... 54 Table 12: Data structure of participants’ selection criteria in terms of priority ... 55 Table 13: Quotations of participants’ perceived options regarding university brand personality when arranging the order of priority ... 55 Table 14: Perceived brand personality dimensions influence each stage of the

Abbreviations

HEIs: Higher Education Institutes JU: Jönköping University

JIBS: Jönköping International Business School et al.: and others

i.e.: that is

e.g.: for example p.: page

1. Introduction

The primary objective of this chapter is to introduce the readers to the context of university brands. The first section presents a piece of background information on why the researched topic is relevant and why the area is worth investigating. Next, the main problem of the research is discussed in detail. Further, the purpose of the study is covered together with the determined research questions. As a final, the chapter ends with a reflection on the delimitations and a presentation of the key terms used in the study.

1.1. Background

Traditionally, marketing and, in particular branding, has mainly been associated with profit-seeking business organizations. However, recently, there has been an increasing trend of more Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) focusing on improving their institution's branding (Chapleo, 2010). This change is due to various factors shaping the higher education sector, which as stated by Balaji et al. (2016) are related to increased competitiveness, reduced financial support from governments, and a reduction in the percentage of the population attending universities. According to Quacquarelli Symonds (2018), one aspect that enhances competition between universities is the extensive amount of available information for students, which creates a brand image when they seek an optimal choice for university. Therefore, when publishing information about their school, it is vital for HEIs to create a strong identity that will appeal to students and attract applicants by focusing on their branding (Quacquarelli Symonds, 2018).

It could be argued that universities are no longer considered only as learning institutions but also as businesses (Bunzel, 2007). The dynamic factors that shift in global higher education trends have changed the industry, forcing universities to invest more resources, time, and effort in building and maintaining their brand (Polyorat & Preechapanyakul, 2020). As discussed by Ningrum et al. (2020), the shift of universities from traditional to modern, business-like institutions and the realization on their behalf that branding is a vital aspect for their differentiation from other institutions is shown by the many benefits obtained. Some of the most noticeable of those advantages obtained from branding to the institutions are expressing prestige,

reducing risk, gaining donors, facilitating both rational and emotional decisions, providing alumni with a sense of belonging in the long term, and allowing students to associate themselves with the organization (Ningrum et al., 2020).

Results from a survey conducted by the Education Advisory Board (EAB) in 2019 that investigated how students search for information about HEIs provide additional support for the increased need to build a sound university brand. The study indicates that nearly one-third of the respondents discovered a particular university for the first time on social media platforms and used a school's social media site to link to the institution's website. Additionally, most participants stated that they found university websites and emails from the institutions as the most useful information sources about the schools. This data's implications confirm the importance of maintaining a dedicated branding strategy that deploys the right channels, actively reaches students on social media, and ensures that the university's website attracts and engages students is vital for the HEI (Education Advisory Board, 2019). Another study by Gallup from 2015 indicates that many students find it challenging to distinguish between different university brands as many of the schools have too similar opinions for their purposes, and very few mention their tangible returns for students (Dvorak & Busteed, 2015).

As stated by Joseph et al. (2012), students contemplate a variety of criteria when choosing an HEI. Among those criteria, together with factors such as a university's image, personal interaction on campus, word of mouth, university representatives, and high-school counselors, students' decisions are highly influenced by the institution's branding initiatives. The brand actions of universities constructively shape their image and may build positive awareness among students, which can have a determinant impact on their choice (Joseph et al., 2012). According to Bock et al. (2014), the fierce competition in the higher education market and the wide variety of choices available makes crafting an effective branding strategy a useful tool for institutions in attracting students and influencing their choices. This is confirmed by the authors’ study, which examined students based on how they evaluate universities. The results indicate that some students consider all the mentioned criteria as being important while others put a high emphasis on the financial aspects of attending a university (Bock et al., 2014). Those findings represent a verification of the necessity for universities to tailor their

branding initiatives and communications in a way that reaches the potential students to influence their university choice. One branding aspect is that of brand personality.

Extending on the idea earlier addressed that universities can be considered as businesses (Bunzel, 2007), it is fair to argue that the concept of brand personality is also important in their branding and applicable to the context of HEIs (Rutter et al., 2017). If students are perceived as customers, it can be assumed that just like the traditional consumers evaluate tangible products and various services by associating human traits to them, students also associate human characteristics with the university brands that they consider that serve a symbolic function and convey how they feel about the institution.

1.2. Problem Discussion

HEIs are increasingly competing for international students in response to international student mobility trends, self-management and budget securement, and government-backed recruitment campaigns. In terms of global student mobility trends, after the Bologna Process launching, students have more choices of universities because they easily move from one country to another in Europe (Portela et al., 2009). Consequently, Swedish HEIs recognize the necessity to develop a distinctive image and position themselves in the growing international competition (Hemsley-Brown & Goonawardana, 2007; Cubillo et al., 2006).

Increasing competition for international students due to globalization and internationalization (Czarniawska & Genell, 2002; Maringe, 2010) requires research in student choice of university brand to get a deeper understanding into the impact of university brand on students’ choice, in addition to factors associated with changes in funding and fees for higher education causing HEIs to compete fiercely for students (Hemsley-Brown & Oplatka, 2015). The final choice decision made by international students will depend on the match between the characteristics of the students (their needs, perceptions, and preferences) and the characteristics of the institutions (programs, tuition fee and financial aid, place or location, and communications), and the information exchanged between the two parties (Chen, 2008). Consequently, international students' preferences are considered an interesting subject that deserves to be studied, focusing not only on national, regional, and local governments interested

in promoting their territories as education destinations but also on HEIs involved in internationalization strategies (Abubakar et al., 2010; Basha et al., 2016). In particular, HEIs need to understand the factors influencing international students' choice of an HEI to improve their marketing activities (Maringe, 2006; Cubillo et al., 2006). An emerging stream of higher education research is brand personality, and it may represent a robust basis for differentiation between many universities competing for student recruitment (Rutter et al., 2017). Brand personality is regarded as a unique and sustainable point of differentiation as well as one of the core dimensions of the brand identity and possibly as the closest variable to the consumers’ decision-making process on buying (Aaker, 1996; Ahmad & Thyagaraj, 2015), which can help Swedish HEIs differentiate themselves and attract the best students. Therefore, the need to investigate university brand personality to create differentiation or gain a competitive advantage as HEIs attract and influence student behavioral enrollment is necessary for HEIs.

Furthermore, it can be said that studies regarding university branding and university brand personality are limited (Ningrum et al., 2020). There are fewer consensus on brand personality meaning and brand personality application to higher education (Banahene, 2017). There is also a lack of attention to the impact of university brand personality on international students' choice. Therefore, it is essential to conduct further research on the university brand personality and its effects on international students' choice.

1.3. Purpose and Research Questions

Given the importance of brand personality for HEIs to deal with the international competition or differentiate themselves, the purpose of this study is to explore international student's perception of the university brand personality that affects the selection of a Swedish university.

To identify the impact of the university brand personality in choosing an HEI of students, the researchers formulated the following research questions:

Research Question 1: How do international students perceive Jönköping University’s brand personality?

Research Question 2: How does the university brand personality influence international students when selecting a Higher Education Institution and specifically Jönköping University?

JU is known as one of the top 10 universities in Sweden in terms of attracting international students, with around 4% of the total students from abroad in Swedish HEIs (Swedish Higher Education Authority, 2020). Thus, the researchers chose JU as a case study of this research. A further reason for this decision is related to the fact that the researchers are current students at JU. This allows for finding the appropriate participants for the study with international backgrounds from researchers’ academic networks.

1.4. Delimitations

To make the thesis more manageable and focused on what is aimed to be investigated, namely JU's brand personality, the researchers have set two realistic boundaries for the research scope. Accordingly, the authors abstract from the pieces of information that have been identified as unnecessary and do not contribute to the enrichment of the study results.

Firstly, the study focuses solely on examining how JU’s brand personality influences first-year foreign existing students at both the bachelor and master levels. Therefore, local and native applicants (i.e., Swedes) do not fall within the scope of the investigation. The target audience of the study is international students, both coming from other continents and different parts of Europe. This choice is justified by the fact that the researchers aim to examine how a specific university's brand influences international students' preferences on a global level. In addition, it has also been decided that the students falling within the scope of the study are not selected based on whether they pay fees or not. This limit is set to avoid the emphasis on the financial aspect of students' preference for a university and to study only the brand characteristics that they perceive and how they influence their choices.

Consequently, this boundary allows both Europeans and those coming from outside Europe to be interviewed. As for choosing first-year students only, the reason for this decision is that it enables extracting the most recent evaluations of choice factors of

people who have recently gone through the process of searching for a university. The researchers assume that they have a more apparent memory of it and can state what influenced them to make that decision and how they perceived the institution's brand.

The research will investigate students’ perspective, meaning that this study's focus will not fall on the different practical approaches and techniques that JU undertakes to manage the branding of the institution although a vital contribution to a strong university brand has the marketing strategy and the various communication channels, platforms, and tools incorporated. Furthermore, this study excludes country choices and focuses on the choice of an institution.

The researchers have used thesaurus terms interchangeably (selecting, choice, choosing, decision making, preference) and combine them with students, higher education, college, university, school or institution for the search purpose.

1.5. Definitions of Key Terms

Brand associations: The other informational nodes linked to the brand node in memory and contained the meaning of the brand for consumers (Keller, 1993).

Brand identity: A unique set of brand associations that the brand strategist aspires to create or maintain (Aaker, 1996, p.68).

Brand image: A set of perceptions about a brand as reflected by brand associations in consumer's memory (Keller, 1993, p.3).

Brand personality: The set of human characteristics associated with a brand (Aaker, 1997).

Higher education: All types of studies, training, or training for research at the post-secondary level, provided by universities or other educational establishments approved as higher education institutions by the competent state authorities (UNESCO,1993).

International students: Individuals enrolled in institutions of higher education who come from different countries excluding Sweden.

Decision-making process: Complex behavior to be broken down into meaningful chunks as the consumer progresses logically throughout the sequence of events in order to solve their problem (Gabbott & Hogg, 1998).

2. Theoretical Background

The aim of this chapter is to present a theoretical background and understanding of the topic to create a clear understanding and then apply to the HEI context, adapting the relevant frameworks to the specific topic.

2.1. Brand

The term "brand" is defined by many authors, academic researchers, and marketers. One of the most popular definitions, presented by Kotler et al. (2005), suggests that a brand is "a name, term, sign, symbol or design, or a combination of these, intended to identify the goods or services of one seller or group of sellers and to differentiate them from those of competitors". It could be argued that the core idea behind that definition is that brands represent a means for standing out from rivals (or competitors) on the market. Brands have two core functions: to differentiate different products and services and to indicate their origin (Kapferer, 1997).

2.1.1. Brand Associations

Brand associations play a role as an information collecting tool to execute brand differentiation and brand extension (van Osselaer & Janiszewski, 2001). The scholars gave a similar definition of brand associations in the literature. According to Aaker (1991), brand associations are the category of a brand's assets and liabilities that include anything linked in the consumers’ memory of a brand. Keller (1993) defines brand associations as informational nodes linked to the brand node in memory that contains the brand's meaning for consumers. These associations represent what the brand stands for and imply a promise to customers from the organization members (Aaker, 1996). It leads to the role of brand associations to marketers and consumers.

Brand associations are significant to marketers and consumers. Marketers use brand associations to differentiate, position, and extend brands, to create positive attitudes and feelings toward brands, and to suggest attributes or benefits of purchasing or using a specific brand. In other words, a set of brand associations enable a brand to develop a rich and clear brand identity (Ghodeswar, 2008). Consumers use brand associations to process, organize, and retrieve information in memory and aid them in making purchase decisions (Aaker, 1991). In other words, the consumer's memory is full of associations towards a brand (Cheng‐Hsui Chen, 2001). It indicates that in the

consumer's memory, for all associates with the brand, if these associations can be assembled all together with some signification, then the impression on this signification would become a brand image (Cheng‐Hsui Chen, 2001). In contrast to brand identity, which is established by the owner of the brand, brand image is created within the minds of customers (Aaker, 2004; Ghodeswar, 2008).

2.1.2. Brand Identity

Brand identity can be considered the "aspired associations envisaged" from the sender or internal perspective (Bosch et al., 2006, p. 13). There are four brand identity perspectives: "brand-as-product (product scope, product attributes, quality/value, uses, users, country of origin), brand-as-organization (organizational attributes, local versus global), brand-as-person (brand personality, brand-customer relationship), and brand-as-symbol (visual imagery/ metaphors and brand heritage)" (Aaker, 1996, p. 68).

Kapferer (1992) develops a concept called "The Brand Identity Prism" that describes the identity of a brand through 6 different characteristics and shows how they are related to one another. The six brand elements include physique, personality, culture, relationship, reflection, and self-image (Kapferer, 1992). In comparison with Kapferer (1992), de Chernatony (1999) also proposes the brand identity model with six components. Three out of six components: culture, personality, and relationships are in line with Kapferer's (1992) study. Other elements are combined or extended. For example, instead of using "physique" in which Kapferer (1992) links between the brand's physical qualities and personality, de Chernatony (1999) talks about "positioning" as well as combining "reflection" and "self-image" into "presentation". In summary, de Chernatony (1999) forms the brand identity model in terms of its vision and culture, which drive its desired positioning, personality, and subsequent relationships, then all of which are presented to reflect stakeholders' actual and aspirational self-images. These components should form a consistent and congruent entity, which leads to a linked identity and message. Consequently, to be effective, a brand identity needs to know what the brand stands for and express it to customers.

2.1.3. Brand Image

Being contrast with brand identity as established from the sender, brand image is formed from the recipients, specifically as the accumulation of specific attributes held

by the consumer, the result of the intensive interface between products, brands, and consumers (including knowledge, feelings, and attitudes toward the brand), which leads to the purchase behavior (Wijaya, 2013). Therefore, brand image plays a vital role in developing a brand because it is related to its reputation and credibility. Alternatively, brand image guides the consumer on how to behave towards the brand, like using or ignoring that brand. Furthermore, a brand is likely to be consumed if the consumers recognize a similar symbolic relationship between the image carried by a brand with their personal self-image (Arnould et al., 2005). It can be said that consumers seek to maintain or enhance their self-image by selecting a product or brand that has the "image" or "personality" that they believe in harmony with their self-image and tend to avoid brands that do not fit with their self-image.

Moving on to the theory that represents the essence and the main object of analysis of this thesis, the next focus will examine the brand personality in detail.

2.1.4. Brand Personality

Brand personality, as a term, is related to associating human characteristics and traits with a specific brand to which a customer can relate that serves a symbolic or self-expressive function (Aaker, 1997). The tendency of anthropomorphizing, i.e., attributing human characteristics to objects, animals, or something else is a natural tendency of people that is highly applicable to different environments and the consumer context makes no exception. Humans assign traits to brands as this allows them to explain their products in terms of their own conceptions and past experiences (Aggarwal & McGill, 2007).

Aaker (1997) distinguishes five brand personality dimensions: sincerity, excitement, competence, sophistication, and ruggedness. The framework's dimensions are derived from 15 personality traits of brands that are divided into 42 different personality traits. The dimension of sincerity is divided into facets that present brands as being down-to-earth, honest, wholesome, and cheerful. Next, the element of excitement involves brands that are daring, spirited, imaginative, and up-to-date. The third dimension called competence represents brands that are seen as reliable, intelligent, and successful. Sophistication corresponds to the facets of the upper class and charming. The last dimension, namely ruggedness, presents brands as being outdoorsy and tough.

Brands possessing a sincere personality are often characterized as transparent, thoughtful, and more family-oriented, while brands related to the dimension of excitement convey a carefree, youthful, and spirited attitude (Staff, 2019). The third type of brands corresponding to Aaker's (1997) dimension of competence is seen as innovative, clever, and efficient in their fields, while those linked to sophistication are defined as lavish, refined, and more expensive and likely to attract a specific group of audience (Staff, 2019). As discussed by Staff (2019), the last dimension called ruggedness includes brands that are adventurous.

Consumers tend to buy certain brands since they are involved with the various relationships with those brands from the meanings that they add to their lives (Fournier, 1998). Similar to human personality, the personality of a brand is highly distinctive, and enduring is one of the most mentioned features of brands. This concept has been a motive for research for many scholars that tried to look beyond product attributes and benefits, which by themself are not sufficient for building a strong brand (Phau & Lau, 2000).

Brand personality can be observed from the standpoint of two main perspectives - the personification of brand attributes and the emotional response that people have with the brand in question (Patterson, 1999; Sung & Yang, 2008). According to Aaker (1997), the development of brand personality is highly contributed by advertising and various marketing approaches, including anthropomorphization, personification, and creation of user imagery. In a more recent research, Eisend & Stokburger-Sauer (2013) find that the personality of a certain brand has an influence on brand aspects such as brand attitudes, the strength of a brand relationship, and purchase intention.

As for the benefits of developed strong brand personality, it constitutes a vital basis for the image of a brand which is efficient in differentiating it in the marketplace (Park & John, 2010; Parker, 2009). Moreover, as discussed by Patterson (1999), brand personality strengthens the brand image for the consumers which through connecting emotionally with the personality of a brand, are inclined to associate it with special meanings and connotations. As suggested by Biel (1993), brand personality is empowering consumers to create a more personal association with the brands, which encourages them to play a more active role in the relationship. When knowledge exists

on how people perceive a given brand's personality, managers can be more strategic in the way they promote their brand (Sweeney & Brandon, 2006).

Despite the wide recognition of brand personality as a construct, the theory has faced criticism by many researchers that adopted it in their studies. Kaplan et al. (2010) share that most of the research in the field of brand personality is focused solely on commercial goods, while Geuens et al. (2009) criticize the main idea of Aaker's model on the basis that it does not specify clearly what brand personality is, it lacks generalizability, and it is non-replicable in the context of different cultures.

From the period in which Aaker popularized the brand personality construct, academics have applied the idea of the theory in various contexts that are different from the initial focus on traditional consumer products and services. Ekinci & Hosany’s (2006) research is an example of applying the concept to tourism destinations, while Opoku et al. (2008) studied the brand personality of Swedish universities. Additional evidence that brand personality is widely applicable across an expanded range of circumstances is the application of Aaker's (1997) framework in an employment context together with brand trust and brand affect by Rampl & Kenning (2014), where the findings of the research indicate a robust link between several brand personality traits and employers' brand affect and brand trust.

2.2. University Branding

In higher education, as stated by Joseph et al. (2012), the branding depicts how well institutions meet the needs of their customers, particularly their students, and is the result of an effective marketing strategy. Benefits from a well-rounded branding of HEIs are observed in the attraction of more and better students, more full-paying students, better faculty and staff, more donated dollars, improved media attention, more resources for research, and more advantages (Joseph et al., 2012).

According to Rauschnabel et al. (2016), the dynamic environment in which modern HEIs operate and compete raises the necessity for customized marketing and branding efforts as this assures strong student and faculty recruitment and higher retention rates. Moreover, prior research indicates that higher education branding contributes to

greater awareness and recognition among multiple constituencies (Rauschnabel et al., 2016).

Recently, branding has proven to be highly effective and important for new universities or for those HEIs that have a higher dependency on international student recruitment for meeting enrollment and financial goals (Bennett & Ali-Choudhury, 2009). Although there is still no general agreement established on the specific dimensions of higher education branding, previous research done suggests that university branding positioning should translate into future student minds’ teaching and learning setting, marketing communications, status and rankings, location, public relation activities, career placement, and cultural integration (Chapleo, 2005; Gray et al., 2003).

2.2.1. University Brand Identity

In the context of higher education, a strong brand identity may benefit the university by enhancing its prestige, student interest, and competitive advantage (Watkins & Gonzenbach, 2013). Cobb (2001) defines university brand identity as what a university wants to be perceived. Bosch et al. (2006) and Melewar & Akel (2005) explain brand identity of an HEI as a characteristic (such as physical specificities and qualities, personality, culture, relationship, customer reflection, and self-image) of the brand based on the visual and verbal elements that the HEI has created. Particularly, HEIs can develop brand personalities indirectly through logos, prospectus, heritage, history, architecture, and location which influence behavioral intentions of both existing and prospective students (Melewar & Akel, 2005).

Cobb (2001) conducts in-depth research into the perceptions of students regarding these six brand identity dimensions. The six brand identity dimensions related to educational institutions comprise the vision of the institution’s brand identity, brand-customer relationship, total employee commitment, quality of programs, commitment of financial resources, and pricing. These six brand identity attributes are related to students’ intention to persist with the HEI. Cobb (2001) only investigates the visual identity of a brand, neglecting the verbal dimensions of brand identity.

In contrast with the study of Cobb (2001), Bosch et al. (2006) show that brand identity in HEIs consists of visual and verbal expressions of a brand. Verbal expressions such

as reputation and personality significantly influence brand identity for HEIs. The results also advocate that vision and value statements shape brand identity, positively correlated with the brand image of HEIs (Bosch et al., 2006). However, Bosch et al.

(2006) use a product-based branding model for the research rather than viewing the educational institution as a service.

2.2.2. University Brand Image

Perceived university brand image refers to students’ beliefs and personal insights of brand associations (Yuan et al., 2016). A positive brand image university possibly leads to distinct and positive associations, emotions, images, and faces, thereby differentiating it from other universities (Panda et al., 2019).

The university brand image can result from both tangible and intangible cues, including functional (tangible) and emotional (intangible) (Tran et al., 2015) or cognitive and emotive evaluations and affective responses (Sultan & Wong, 2019). Potential students can gather information about the tangible dimensions of the university such as the university’ s infrastructure, facilities, location and cost of admission from various sources. However, the tangible aspects do not help them make concrete decisions about their consideration sets. Therefore, they resort to appraising the brand image of the university. Dawar & Parker (1994) pinpoint the importance of brand as signals in assessing the quality of products or services in highly risky and complex environments where buyers lack the expertise and involvement to overcome the confusion and make objective purchase decisions. In line with the results of Dawar & Parker (1994), for HEIs, brand image potentially plays a significant role in reducing the risk associated with such service mainly because quality assessment takes place after consumption (Binsardi & Ekwulugo, 2003; Chen, 2008). Therefore, having a strong brand image is essential as a risk reliever that facilitates the decision-making process (Chen, 2008).

Panda et al. (2019) form a university brand image with three dimensions: university heritage, trustworthiness, and service quality. Their findings suggest that a university's brand image plays an important role in creating a distinct image in its students' minds, resulting in its competitive advantage. Consequently, the brand image represents a differentiation tool that gives the students cues during their decision-making process (Temple, 2006; Azoury et al., 2014; Dejnaka et al., 2016). A positive brand image

results in increased reputation and is positively associated with students' satisfaction and student choice, which would eventually lead to tangible and intangible benefits for the university.

Brand image is especially vital for helping private universities gain entry to the brand consideration set (Alkhawaldeh et al., 2020). In Alif Fianto et al.’s (2014) research, the analysis results suggest that brand image has a positive and significant influence on purchase behavior among students registered into private universities. This research re-enforces and extends previous research findings focused on brand image, brand trust, and purchase behavior (Rindell et al., 2011; Bravo et al., 2012). This study also reveals that brand image directly or even through brand trust's mediating effect has a dominant role in influencing purchase behavior.

2.2.3. University Brand Personality

As discussed by Opoku et al. (2008), since students are not able to completely experience the educational process before attending university, it is likely that they will rely on the HEIs' brand personality, as a prerequisite or as an input in their decision regarding their future education. Therefore, HEIs brand personality deserves robust attention in modern times where universities are internationally exploiting and capitalizing on marketing opportunities (Opoku et al., 2008). As suggested by Polyorat & Preechapanyakul (2020), university brand personality represents a reflection of the degree to which students perceive HEIs as having human traits such as being friendly, stable, and warm, and therefore, it can be perceived through the interaction between the university and students. As an example, an interaction between university staff members and students may evoke a perception of university personality such as competent, professional, and helpful (Polyorat & Preechapanyakul, 2020). Although also being relevant for existing students, the interaction may as well have a positive impact on future students’ choice of university.

In addition to the interaction, those human-like characteristics can also be established by an HEI's logo, heritage, history, and through its marketing communication approaches undertaken (Polyorat & Preechapanyakul, 2020). It is therefore safe to argue that just as it is relevant to the context of consumer goods and services, the concept of brand personality is highly applicable to HEIs brands. Since universities do

not have a tangible product to offer and brand, they are branding themselves, which means that their brand and personality depend on how HEIs are perceived by external audiences (Harris, 2009).

In a pursuit to develop a new way of evaluating university brands, in one of the more recent studies in the field, Rauschnabel et al. (2016) develop a university brand personality scale (UBPS) that is adapted based on Aaker's (1997) framework by improving some of the model's criticisms addressed by many researchers. As previously discussed in the Background section of this thesis, the dimensions from the UBPS correspond to "prestige", "sincerity", "appeal", "lively", "conscientiousness", and "cosmopolitan" (Rauschnabel et al. (2016). The dimension of prestige represents a university's reputation, perceived successfulness, snob appeal, and acceptance. Sincerity shares similarities with the sincerity dimension of Aaker's (1997) scale and displays correlation with the items of humane, helpful, friendly, trustworthy, and fair. The UBPS dimension of appeal reflects the desirable traits of universities as a person and shows a correlation to the items of attractive, productive, and special. The lively dimension is somewhat similar to Aaker's (1997) dimension for excitement and in the context of universities, it is related to the items of athletic, dynamic, lively, and creative. In the UBPS, conscientiousness is linked to the items of organized competent, structured, and effective. The last dimension of the scale by Rauschnabel et al. (2016) called cosmopolitan describes whether people view a university as a closed or open institution and is correlated to the items of networked, international, and cosmopolitan. The scale represents a useful tool for university managers that allows for effective measurement of their institution's and competitors' brand personalities. Rauschnabel et al. (2016) emphasize the need for HEIs marketing managers to precisely assess their institution's current position and develop ideal UBPS profiles based on the established methods in academic and applied literature streams.

The research by Opoku et al. (2008) indicates that some Swedish universities create strong online brands with a clear positioning that is pursued by the communication of strong brand personality dimensions, such as ruggedness, competence, sophistication, or sincerity. Others, in contrast, do not position themself as effectively on any specific brand personality dimension or do not communicate any of the dimensions at all. The study found that JU’s English website communicated a brand

personality dimension of competence by emphasizing that the institution provides a young and vital academic environment. However, given that the paper by Opoku et al. (2008) can be described as relatively outdated, it may not represent the reality of the current brand personality of a Swedish HEI.

2.3. The Decision-Making Process of Students

Students are highly selective when choosing an HEI to enroll in because there are many options available in the market; thus, the bargaining power of students becomes higher (Shamsudin et al., 2019). To improve marketing activities, HEIs need to understand how students decide where to attend university (Maringe, 2006). The selection of a university is a unique decision-making process in which prospects engage in various stages of a lengthy consideration process (Moogan et al., 1999; Maringe, 2006; Vrontis et al., 2007; Stephenson et al., 2016). The university choice process was explained in terms of the following four models: economic models, sociological models, combined models or information processing models, and the marketing approach (Ivy, 2010; Aydin, 2015).

First, economic models identify the university choice process that students analyze cost-benefit carefully (Hossler et al., 1999). Students want to maximize their utility and minimize the risks when choosing a university. Students make the university's decision choice based on comparing the expected benefits with the university's costs (Paulsen, 2001). They also evaluate all the information available according to their preferences at the decision time (DesJardins & Toutkoushian, 2005). Additionally, Fernandez (2010) emphasizes that students will choose a university if they perceive that their benefits outweigh those of other universities.

Second, in contrast with economic models that focus on students' rationality as influences of choice, sociological models reject to assume students being rational deciders (Aydin, 2015). The sociological perspective focuses on the university choice process. It is considered as part of the status attainment process with emphasis on students’ background factors that influence the decision of whether and where to go to university (Bergerson, 2009). Sociological models of college choice refer to social, cultural and individual elements (Perna, 2006) or the student’s background in deciding to study further (Kotler & Fox, 1995; Chapman, 1981). The background factors that

impact student choices include race and ethnicity, family income, parent education, peer groups, school contexts, parental expectations, parental and student educational aspirations, academic achievement, academic ability, school counselors, self-fulfillment, motivation, and personal goals (Ivy, 2010; Bergerson, 2009).

Third, the combined models incorporate components of economic model rational assumptions and status-attainment models to determine how students decide to go to university and the processes they use to select the HEIs to which they apply (Ivy, 2010). Combined models assume multiple stages of the student decision-making process (three-stage models and multi-stage models typically containing five stages).

The model proposed by Jackson (1982) combines economic and sociological factors and then assumes three phases in the student decision-making process. The first of one is the preference stage, where academic achievement has the most substantial effect. The second is the exclusion stage, where students are involved in the elimination process. The last one is the evaluation stage, where the students get their final decision. In comparison with the model of Jackson (1982), the Hanson & Litten (1982) model involves three phases: the decision to follow a higher education institution, exploration, and enrollment. Three phases consist of five distinct processes. The first phase consists of two steps: desire to follow a university and then decide to start this process. The second phase involves collecting information about the institution. The final phase, enrollment, comprises two stages: registration and confirmation.

Hossler & Gallagher (1987) develop a college choice model that includes three stages: predisposition, search, and evaluation. Students determine whether they will pursue higher education or develop college aspirations and expectations regarding higher education in the predisposition stage. In the second stage, students try to determine the institutional attributes important to them and search for information (Obermeit, 2012). In the third stage, students evaluate their school options to make a final decision about which institution to attend.

While Klimavičiena & Alonderienė (2013) skip the problem recognition stage and form a three-step model based on consumer decision making process (information search,

alternative evaluation, and decision making), Ionela & George (2014) give the decision process of choosing a higher education institution requires four steps: problem recognition (desire - motivation), information search, alternative evaluation, and decision making. The first step is recognizing the need to follow a higher education institution. After problem recognition, the second step involves information search in order to satisfy the need. This step involves identifying options and evaluation. The last step consists of deciding to enroll in the chosen institution.

The study of Moogan (2020) explores the decision-making process of international postgraduate students. The student decision-making process comprises five stages: need recognition (realizing the feasibility of studying a postgraduate program), information search (researching program information and university details), evaluation of alternatives (assessing the alternative "brands" available), purchase (enrolment and then consumption of the program from introduction to the final module) and post-purchase evaluation (graduation and alumni feedback) (Moogan, 2020). The result indicates that students find uncertainty in the initial periods. It is in line with the previous research of Moogan et al. (1999), which stated that potential students find the decision-making process to be complicated and risky, despite spending much time searching and checking all the evidence. Prospective students also follow the sequential steps of the process, although some steps will overlap for some students depending upon their current situation (Moogan et al., 1999).

Finally, the marketing approaches are incorporated in the consumer choice models in terms of internal (cultural, social, personal, psychological characteristics) and external (social, cultural, product, and price stimuli) influences, added by communication efforts of HEIs (Obermeit, 2012). The university choice is assumed like a funnel in which students start with a comparably extensive awareness set of HEIs that is narrowed down to a consideration and choice set (Stephenson et al., 2016). External factors, attributes of the HEIs, and their communication activities impact the process (Hossler & Gallagher,1987). Therefore, next to sociological and economic factors, universities' impact on the students' decisions is deliberately included in this approach (Bergerson, 2009).

According to Moogan et al. (1999), most of the students’ decision-making process models are based on Kotler’s (1997) consumer buying decision process (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Consumer buying decision process

Source: Kotler (1997)

The five-stage process comprises identifying a problem or need recognition, information seeking, evaluating alternatives, selecting and making the purchase decision, and finally, assessing the purchase decision.

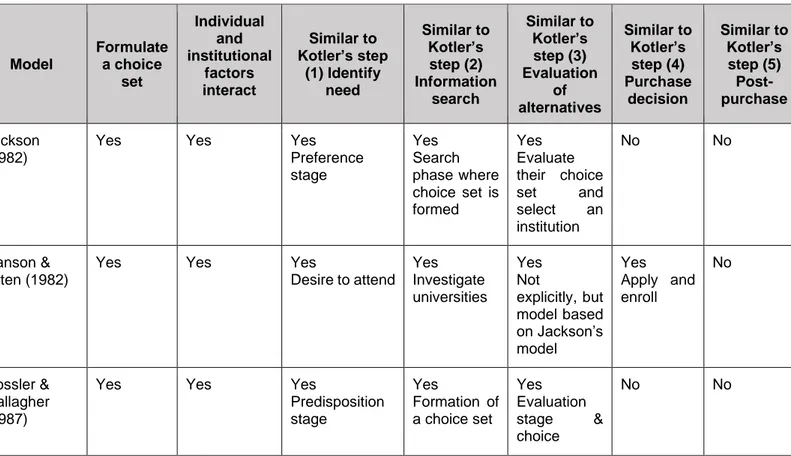

Thus, summarizing the differences and similarities of these models in Table 1 will allow the researchers to understand common themes that can be applied in this study.

Table 1: Comparing students’ decision-making process models

Model Formulate a choice set Individual and institutional factors interact Similar to Kotler’s step (1) Identify need Similar to Kotler’s step (2) Information search Similar to Kotler’s step (3) Evaluation of alternatives Similar to Kotler’s step (4) Purchase decision Similar to Kotler’s step (5) Post-purchase Jackson (1982)

Yes Yes Yes

Preference stage Yes Search phase where choice set is formed Yes Evaluate their choice set and select an institution No No Hanson & Litten (1982)

Yes Yes Yes

Desire to attend Yes Investigate universities Yes Not explicitly, but model based on Jackson’s model Yes Apply and enroll No Hossler & Gallagher (1987)

Yes Yes Yes

Predisposition stage Yes Formation of a choice set Yes Evaluation stage & choice No No

Model Formulate a choice set Individual and institutional factors interact Similar to Kotler’s step (1) Identify need Similar to Kotler’s step (2) Information search Similar to Kotler’s step (3) Evaluation of alternatives Similar to Kotler’s step (4) Purchase decision Similar to Kotler’s step (5) Post-purchase Klimavičiena & Alonderienė (2013)

Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes

Enroll

No

Ionela & George (2014)

Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Enroll

No

Moogan (2020)

Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Enroll and consume Yes Graduation and alumni feedback

Source: Jackson (1982), Hanson & Litten (1982), Hossler & Gallagher (1987), Klimavičiena & Alonderienė (2013), Ionela & George (2014), Moogan (2020)

It is evident from Table 1 that prospective students draw up a choice set from which a choice will be made. Furthermore, all the models present that individual and institutional factors interact in the decision-making process. When it comes to comparing the six models’ steps with Kotler’s decision-making processes’ five steps, all the models include at least three of the five of Kotler’s decision-making process steps. Not all the models recognized that students would first determine the need to follow further education; however, all the models mention that prospects would go through the information search and evaluation of alternatives step. Apart from Hanson & Litten’s (1982) model, the remaining models mention that potential students will evaluate their alternatives. During this stage, factors will be compared and analyzed, such as social-cultural factors, the universities’ attributes or benefits, and where discussions will occur with family, friends, or significant others such as counselors, career advisers, former professors. Although Hanson & Litten’s (1982) model does not explicitly disclose this third step of evaluation, it can be assumed that evaluation will also happen in their model because it is based on Jackson’s (1982) student-based model. Regarding the purchase decision stage, Klimavičiena & Alonderienė’s (2013) and Ionela & George’s (2014) model only refer to enrollment, while Moogan’s (2020) model includes consumption of the program.

The decision to go to a specific university is a complicated and multistage process (Moogan et al., 1999). Each model interpreted in this section suggests that choices need to be made between different universities and programs, that individuals and institutional factors interact with one another, and that all potential students will enter some sort of information search process followed by evaluation before making a decision. Particularly, all five steps will be discussed briefly as follows.

2.3.1. Need Recognition Stage

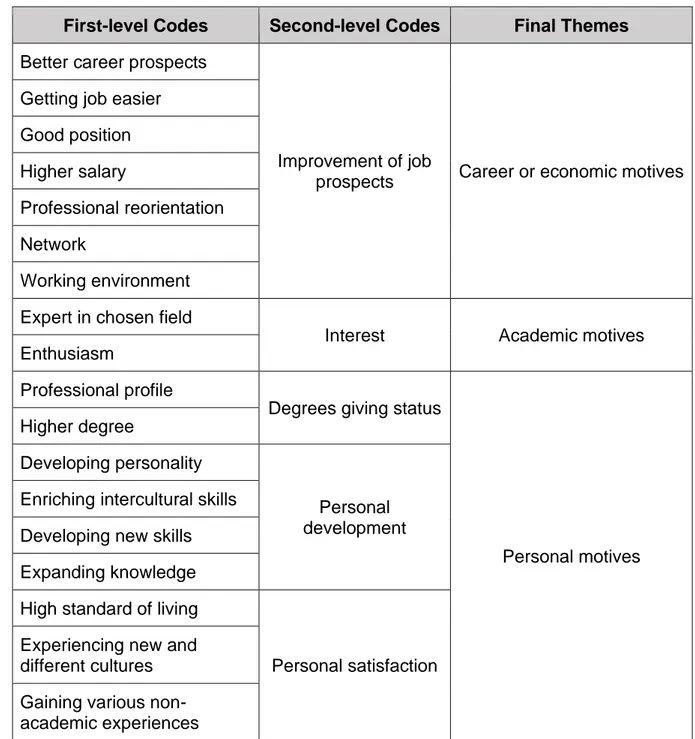

There are many reasons why potential students will identify the need to go to university. Ivy (2010) identifies five primary motivators for why potential students will consider applying to go to university: (1) career or economic motives that include earning more money and further career prospects; (2) academic motives that include interest in the subject or good exam results; (3) social motives that include factors like being with one’s friends; (4) family motives that include parents’ influence on a child to further their education or to apply for university admission, and (5) personal motives that include degrees giving status, personal satisfaction, becoming more independent, opportunities to move abroad and getting away from home. Ivy’s (2010) research finds that most participants felt very strongly that their careers were the most important motivating factor for further education. In line with Ivy’s (2010) study, Moogan (2020) points out that career rewards and progression are a solution for potential students in the problem recognition period because they saw the qualification as a stimulant in aiding their professional progression. As a result, students find and apply to the universities to satisfy their motives (Stephen et al., 2016).

2.3.2. Information Search Stage

The next step would be to seek information regarding which universities are available and which programs there are to study. Information gathering is an important step to aid prospective students’ decision-making. As students cannot try before purchase, thus the reliance on information is much more significant. Students' most commonly used information sources are the Internet, advertisements, agents in their home country, social media, friends, or family during the searching stage (Moogan, 2020). Specifically, the most credible information sources are word of mouth from family or friends, but using social media (Instagram, LinkedIn, and Facebook) helps prospective students gather their knowledge. The initial information searching activity consists of

evaluations of course content, location and reputation of universities, and specific program requirements (Moogan et al., 1999).

2.3.3. Evaluation of Alternatives Stage

The main focus of the decision-making process will be on the third step, the evaluation of alternatives stage. Here, potential students narrow down the range of choices by (1) identifying alternatives, (2) determining evaluation criteria, and (3) applying the criteria to the alternatives in order to come to a choice (Kotler & Fox, 1995). Successive sets in decision making include the total set of universities which prospective students will not necessarily be aware of, and then the awareness set followed by the consideration set, to finally arrive at the choice set that will be used as the final list of alternative universities from which to choose (Kotler & Fox, 1995; Jackson, 1982; Hossler & Gallagher 1987). To narrow alternative universities down from the awareness set to the consideration set to arrive at the choice set requires potential students to evaluate and weigh all the alternatives according to some evaluation criteria. The main factors that are used as evaluation criteria were found to be those of course content, the reputation, as well as location of the university, and social considerations (Moogan et al., 1999). To extend the research for international students, Moogan (2020) uncovers that students’ choice of university is influenced by a variety of variables such as university ranking, teaching quality (accredited), geographical location (an English-speaking institution), ethnic diversity, costs (tuition fees and the cost of living), internship opportunities, political stability, local student population and personal recommendations via social media.

2.3.4. Purchase and Consumption Stage

Following the final choice set of universities, potential students will make a choice of which university they will apply at and when accepted, they will enroll. This stage is purchase or consumption which refers to whether to purchase, when to purchase, what to purchase, where to purchase and how to pay (Vrontis et al., 2007).

At the consumption stage of the decision-making process, Moogan (2020) figures out some feedback of students at the end of the first semester (four months later) and the taught program (one year later). During the early teaching period, the feedback related to information overload, adjusting to the academic expectations, academic issues

(library access, performing group work and other facets of the curriculum). In the later teaching period, the comments were less academic and more personal such as the temperature of the room, the facilities of the canteen, and limited break-out space.

2.3.5. Post-purchase Stage

Once the service performance has been completed, satisfaction about how the service was delivered will be reviewed. Here, students who have completed their thesis or are about to have their grades would give their reflective feedback (Moogan, 2020). There is a fundamental expectation of a service, which implies that it provides what it promises. In particular, the potential students reflect back on their experiences and decide if the service was satisfactory or unsatisfactory (Vrontis et al., 2007).

In the research of Moogan (2020), the majority of students reflected that the service delivery had met their expectations and they would recommend the program to others.

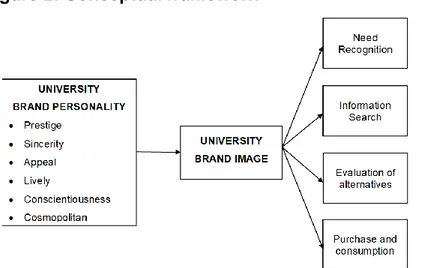

2.4. Conceptual Framework

To assemble the different aspects of university brand, the researchers studied the factors that involve the brand associations in the higher education context, such as brand image in the relationship with brand personality that influences student choice. Based on the literature of Alif Fianto et al. (2014), Rauschnabel et al. (2016) and Moogan (2020) as well as the research purpose and the participants as first-year students who have not finished the program, the researchers propose the conceptual framework as the guideline of this study.

Figure 2: Conceptual framework

Source: Adapted from Alif Fianto et al. (2014), Rauschnabel et al. (2016) and Moogan (2020)

3. Methodology

The following chapter focuses on showing the methodological logic and process incorporated into the current research. Consequently, first, the philosophical standpoint is discussed and the reasons for selecting the interpretivism paradigm are shared. Further, the reasoning for incorporating an abductive research approach is discussed. Thereafter, the researchers discuss how choosing a qualitative type of study with semi-structured interviews is the most appropriate path for collecting the data of this study. The relevant approaches that were taken and the decisions made regarding the collection and analysis of the data are also discussed. Finally, the chapter ends by presenting the ethical considerations of this study and discussing how the quality of the research is ensured.

3.1. Research Philosophy

To effectively collect the relevant data that can answer the research questions of this thesis, the system of beliefs and assumptions about the development of knowledge under which the research fits must be carefully determined. This section aims at presenting the set of beliefs that serve as a guide for the investigation, also known as research philosophy (Saunders et al., 2016). Determining the philosophy of research will allow for distinguishing the source, nature, and development of knowledge, which as a result will contribute to identifying how the data should be collected, analyzed, and used (Bajpai, 2011).

As discussed by Saunders et al. (2016), there are three types of research assumptions used to distinguish research philosophies: ontology, epistemology, and axiology. Ontology refers to assumptions made about the nature of reality (Saunders et al., 2016), while epistemology is concerned with assumptions about the knowledge and how it is communicated to others (Burell & Morgan, 1979). The third research assumption, called axiology, refers to determining what is the role of values and ethics within the research process (Saunders et al., 2016). The philosophy under this investigation is viewed both from an ontological and epistemological point of view as this approach allows for identifying how reality is perceived and how the knowledge is approached (Saunders et al., 2016).

From the five suggested by Saunders et al. (2016) research philosophies called positivism, critical realism, interpretivism, postmodernism, and pragmatism, it was determined that the most relevant paradigm for this study is interpretivism. The nature of reality under this philosophical standpoint is rich and complex, consisting of multiple meanings and realities with the theories presented being simplistic and focused on stories and perceptions (Saunders et al., 2016). As suggested by Saunders et al. (2016), interpretivism follows a value-bounded approach, with researchers being part of what is explored, which is exactly the case with the present study. It was decided that the engagement of the researchers is essential for the current research since as interpretivists, they try to obtain the most reliable insights on the perceptions of the people under investigation. By following the characteristics of interpretivism, this research incorporates an abductive research method, with small samples, in-depth investigations, and qualitative methods of analysis (Saunders et al., 2016).

3.2. Research Design

Since as earlier discussed, in-depth research about the brand personality of HEIs is missing, the context of the present study requires a research design that provides insights into this particular phenomenon. Consequently, it was concluded that following exploratory research is most appropriate. The primary reason for deciding that this is the best fit for the research is that as suggested by Nunan et al. (2020), exploratory research is applicable in cases where information needed may be loosely defined, the research process required is flexible, and unstructured with small samples. As discussed by Saunders et al. (2016), exploratory studies represent a valuable way of discovering what is happening and researching a particular topic of interest where research questions are likely starting with "what" or "how". As it is the case of the present study, where the focus lies on clarifying the understanding of the under-researched concepts of HEIs brand personalities and students' choices, an exploratory research design is particularly useful in research areas with an uncertainty of the phenomenon's precise nature (Saunders et al., 2016).

By incorporating this type of research design, the researchers can conduct more flexible interviews (Nunan et al., 2016), which are likely to rely on the quality of contributions from the interviewees to guide the subsequent stage of the research (Saunders et al., 2016). Following qualitative research, the method is more applicable