School of Health, Care and Social Welfare

SOCIAL MEDIA USAGE AND BODY

APPRECIATION

A quantitative cross-sectional study among Swedish adults

GRETA KARLSSON

Main Area: Public Health Sciences Level: Second Cycle

Credits: 15 Higher Education Credits

Programme: Master’s Programme in Public Health within Health and Social Welfare Course Name: Thesis in Public Health

Supervisor: Susanna Lehtinen-Jacks Examiner: Katarina Bälter

Seminar date: 2020-06-04 Grade date: 2020-06-25

ABSTRACT

Among Swedish adults, 50% are active on social media daily. Regarding body image, 50% of Swedish adolescents are happy with their weight, although no statistics are available among Swedish adults. Time spent on social media is related to body dissatisfaction and viewing of body positive content increases body appreciation. Applying a salutogenic approach, a theoretical framework of sense of coherence was used in this study. The aim was to examine: if there is a relationship between social media usage and body appreciation in Swedish adults; if there are gender differences; whether this potential relationship is evident after controlling for age, gender, physical activity, sedentary lifestyle, and viewing of body positive content. A quantitative method was used. Data from 153 participants was collected using questionnaires, and analysed using correlation analyses and multiple regression analyses. The results revealed that there was no relationship between general social media usage and body appreciation – however, the less time spent on social media, the better body

appreciation participants had. This relationship was only evident among women. The relationship was still observed after controlling for confounding. These findings were in line with some previous findings. Women’s body appreciation could possibly favour from

decreased time spent on social media.

CONTENTS

1 INTRODUCTION ... 1

2 BACKGROUND ... 2

2.1 Social media ... 3

2.2 Body appreciation ... 4

2.3 Social media and body appreciation ... 5

2.4 Problem formulation ... 7

3 AIM ... 8

3.1 Research questions ... 8

3.2 Study hypothesis ... 8

4 METHODS AND MATERIAL ... 8

4.1 Methodological approach and study design ... 8

4.2 Sample ... 9

4.3 Data collection ... 9

4.4 Measures ... 10

4.4.1 Physical activity ... 10

4.4.2 Sedentary lifestyle ... 10

4.4.3 Body positive content ... 10

4.4.4 Social media usage ... 11

4.4.5 Body appreciation ... 11

4.5 Processing of data ... 11

4.6 Analysis ... 13

4.7 Ethical considerations ... 16

5 RESULTS ... 17

5.1 Relationship between social media usage and body appreciation ... 19

5.1.1 Gender specific relationships ... 19

5.2 Relationship between social media usage – time spent on social media – and body appreciation controlled for confounding ... 20

5.2.1 Relationship controlled for confounding among women ... 22

6 DISCUSSION ... 23

6.1 Methodological discussion ... 24

6.1.1 Sample and data collection ... 24

6.1.2 Measures, processing of data, and analysis ... 25

6.1.3 Quality and ethical considerations ... 26

6.2 Result discussion ... 27

6.2.1 Future research and practical implications ... 30

7 CONCLUSIONS ... 30

LIST OF REFERENCES ... 31

APPENDIX A; COVER LETTER APPENDIX B; QUESTIONNAIRE

APPENDIX C; COVER LETTER IN SWEDISH APPENDIX D; QUESTIONNAIRE IN SWEDISH

1 INTRODUCTION

In Sweden, the public health is considered good. However, the mental health is a public health issue, as approximately one in five Swedish adults experience impaired mental well-being (Folkhälsodata, 2018). Body image is a part of mental health, and research suggest that body image concerns are common (Conner, Johnson & Grogan, 2004). While body image concerns are a risk factor for aspects of mental ill-health such as anxiety and depression, body appreciation is related to various aspects of well-being: life satisfaction, self-esteem, and happiness (Halliway, 2015). To increase the well-being of Swedish adults, addressing body appreciation promoting factors could be considered important. While previous research mostly has focused on negative body image, this study will highlight positive body image by examining the relationship between social media usage and body appreciation.

Previous research has discovered relationships between body image and social media usage (Cohen, Fardouly, Newton-John & Slater, 2019; Sherlock & Wagstaff, 2019). However, research on Swedish adults is lacking on this topic. Regardless, social media usage is related to both positive and negative aspects of body image, depending on how social medias are used (Choukas-Bradley, Nesi, Widman & Higgins, 2019). For example, viewing body positive content on social media platforms can lead to increased body appreciation (Cohen et al., 2019). Additionally, it is primarily young women who are affected by the relationship between social media usage and negative body image (Conner et al., 2004). Thus,

interventions specifically targeting this group could contribute to closing the gap in health. Similarly to other study populations, the majority of Swedish adults have accounts on social media and uses social media in their everyday life (Statistics Sweden, 2019). Thus,

relationships on social media and body appreciation may be similar among Swedish adults, as compared to populations previously studied. However, since social media is constantly evolving, previous research might not be accurate today. Thus, the relationship between social media usage and body appreciation needs to be studied further. As body appreciation can influence the well-being, it could be considered an important matter for the public health. The author of this study had a limited preunderstanding of the topic. However, the interest arouse from related topics discussed during the course of the author’s education. Because the topic has not received much attention in Sweden, the author’s interest increased. In March 2020, during the on-going degree project work, Sweden was affected by extensive societal changes due to the risk of the contagion COVID-19 virus. A recommendation was given to organize all university-level teaching to be conducted online. As major parts of the society were affected, the Government gave regulations to avoid physical contact with other people to avoid spreading the infection. As a consequence, there were difficulties to collect data for the degree projects. Therefore, in this specific thesis, questionnaires were shared via Facebook, and instead of targeting a specific group (e.g. a specific gender or age group), a larger source population was targeted.

2 BACKGROUND

In an international perspective, the public health in Sweden is considered to be good (Folkhälsomyndigheten, 2020a). In February 2020, the Swedish adult population (18 years and older) consisted of about 8 250 000 people (Statistics Sweden, 2020). During the last decade, there have been improvements in the population’s overall health, and the majority rates their overall health as good or very good. However, as some aspects of health increases, some decreases – for instance, mental health (Folkhälsodata, 2018). In the Swedish adult population, 17% have an impaired mental well-being – an increase of five percentage points during the last decade (Folkhälsodata, 2018).

The goals in the United Nation’s (UN) agenda 2030 are essential for the work conducted within the public health sector in Sweden (Folkhälsomyndigheten, 2019). One of the goals included in agenda 2030 refers to ensuring good health and well-being; in order to ensure this, health risks should be targeted (UN, 2015). As the well-being of the Swedish adult population decreases (Folkhälsodata, 2018), targeting and working with indicators of well-being could possibly be a way to reverse this trend, and is in line with the UN’s advice in agenda 2030: to target health risks (UN, 2015).

Another goal included in agenda 2030 refers to gender equality (UN, 2015). Inequities in health occur in several layers in society. For example, societal norms and values generates gender inequities, putting women in an unfavourable position (CSDH, 2008). For instance, while 14% of the adult Swedish males have impaired mental well-being, 20% of the women have impaired mental well-being (Folkhälsodata, 2018).

There are several determinants of health, existing at different levels in society. The social environment is one of these determinants and involves social interaction and social connectedness. Social relationships can both have positive and negative effects on health; while social connectedness have positive effects on health, social strain, in form of for

instance criticism and excessive demands, can have negative consequences on health (Green, Tones, Cross & Woodall, 2015). Social interaction occurs for instance on social media

platforms (Bekalu, McCloud & Viswanath, 2019).

Sense of coherence (SOC) is a theory developed by Aaron Antonovsky in the 1970’s

(Antonovsky, 1979). SOC refers to the extent people have pervasive, yet dynamic, feelings of confidence. For people with high SOC, stimuli (i.e. something perceived by the senses) are structured and predictable, and the available resources are enough to counter perceived demands. Further, the demands are perceived as welcomed challenges. SOC origins from the salutogenic perspective of health – the focus lies on health and how to promote health. On the contrary, a pathologic perspective of health rather studies aspects of disease and how to prevent disease. By applying a salutogenic approach, studying health promoting factors rather than risk factors is suitable. These two perspectives of health are however

complementary, and both contribute to gained knowledge. Moreover, SOC have been shown to protect from ill-health (Antonovsky, 1987). For example, SOC is a protective factor against mental health problems, such as anxiety and depression (Hochwälder, 2013). On the same

note, there is also a relationship between mental well-being and SOC (Mato & Tsukasaki, 2017).

SOC is also related to physical activity. Among adolescents, high levels of physical activity is related to high levels of SOC (Moksnes, Løhre & Espnes, 2012). Further, physical activity is a protective factor against several health problems, including both physical and mental aspects of health (WHO, 2010). Thus, physical activity could possibly be a protective factor for body appreciation. Being physically active reduces risks of for example cardiovascular disease and depression – whereas a sedentary lifestyle constitutes a risk. The global recommendations for physical activity among adults aged 18 to 64 is at least 150 minutes of moderate physical activity, or 75 minutes of intense physical activity – or a combination (WHO, 2010). The same recommendations are adopted in Sweden (Folkhälsomyndigheten, 2016). Sedentary lifestyles are common in Sweden, as many people work, commute, and spend their spare time sitting down. Sedentary lifestyle is a risk factor for ill-health, even among people who reach the recommendation for physical activity (Statens Folkhälsoinstitut, 2012).

2.1 Social media

Social media can be defined as websites and apps where users can upload and post original content which can be viewed and commented on by other users (Choukas-Bradley et al., 2019). In this study, social media and social network will be treated synonymously. Social networking sites are websites where users can upload and post information about themselves and message other people (Longman dictionary of contemporary English, 2009). In this study, social networking sites will regard specific sites. The majority of the Swedish adult population have an account on social media. In 2018, half of the Swedish population aged between 16 and 84 were active in a social network on the internet every day. Further, in 2018, three quarters of the same age group were active on a social networking site at least monthly. The use of social media varies between age groups in Sweden, whereas younger people more frequently engage in social media. The majority of Swedish people aged between 16 and 34 were active on social networking sites every day in 2018. In Swedish people aged 16 and older, women are more active on social networking sites than men. Among women, 80% are active on social networking sites monthly; daily, half of the Swedish women are active on social networking sites. Among men, approximately 70% are active on social networking sites monthly, while just below half of the men are active every day (Statistics Sweden, 2019). Social media is used widely around the world, and is increasingly common (Shayka &

Christakis, 2017). Social media is a tool that, for example, can be used for social interactions, for identity formation, to receive news, and for entertainment (Bekalu et al., 2019). Social media has changed how people communicate with each other and has been shown to

influence mental health both positively and negatively. Further, life satisfaction is negatively associated with social media usage – whereas having real life friends is a health promoting factor (Shayka & Christakis, 2017). Similarly, research suggest that there is a slight

association between high SOC and lower usage of smartphones for social interaction (Sharabi, Sade & Margalit, 2016).

Recently, a new trend on social media platforms has developed – body positivity. Body positivity aims to challenge social norms that idealizes thin bodies of women, and instead shows a diversity of bodies with a variation of sizes, shapes, colours, functions, and features. Body positive content involves photos representing a variety of bodies, highlighting people’s differences (Cohen et al., 2019). From June 2018, to April 2020, the hashtag #bodypositivity had increased the number of posts from around 1.8 million posts to around 4.4 million posts. The hashtag #BoPo had, in the same time period increased the quantity of posts on

Instagram from around 670 000 posts to over a million posts (Cohen et al., 2019; Instagram, 2020).

2.2 Body appreciation

Body image is a complex concept with several definitions and many dimensions. Body image involves the feelings, perceptions, thoughts, and acts of individuals’ own bodies (Conner et al., 2004; Rutledge, Gilmore & Gillen, 2013). Body satisfaction is defined as “individual’s contentedness with their overall body or with specific body parts” (Wang et al., 2020). Body appreciation is defined as “accepting the features, functionality, and health of the body” (Tylka & Wood-Barcalow, 2015a, p. 122). Further, it is not merely focusing on appearance (Tylka & Wood-Barcalow, 2015a). Both body appreciation and body dissatisfaction are indicators of the wider concept body image. However, there are some differences between them. Body dissatisfaction is an indicator for negative body image; body appreciation is an indicator for positive body image (Tylka & Wood-Barcalow, 2015a). Further, while body dissatisfaction is related to depression, there is no such correlation between body appreciation and depression, after taking attachment (i.e. how people have learned to interact in relationships) and perfectionism into account (Halliway, 2015).

Around half of the 15-year-old adolescents in Sweden are happy with their weight – 47% of the girls, and 57% of the boys. However, 40% of the girls in Sweden think that they are too fat, and 19% of the boys think they are too fat. On the contrary, 13% of the girls think that they are too thin, while 24% of the boys think that they are too thin (Folkhälsomyndigheten, 2018). However, there are no statistics on how Swedish adults view their bodies. Moreover, there has not been any focus on body appreciation in Swedish adolescents; rather, focus have been on perceived weight and dieting (Folkhälsomyndigheten, 2018). Notwithstanding, body dissatisfaction is a risk factor for disordered eating and eating disorders (Myers & Crowther, 2009). On the contrary, body appreciation is related to for example happiness, self-esteem, life satisfaction, and optimism (Halliway, 2015).

Body image has been researched extensively among young women (Choukas-Bradley et al., 2019; Strubel, Pietrie & Pookulangara, 2018; Veldhuis, Alleva, Bij de Vaate, Keijer & Konijn, 2020; Wang et al., 2020). However, when examining how age affects body image, research suggests that body appreciation increases with age (Halliway, 2015). Body dissatisfaction has become an issue among increasingly younger people (Myers & Crowther, 2009). However, women aged 40 to 65 has reported feeling less body acceptance from family, friends, and society than women aged 18 to 39 (Halliway, 2015).

In a sample of Swedish young adults, the development of a positive body image included feelings of acceptance, belonging, empowerment, and control over actions and their

consequences (Gattanio & Frisén, 2019). Additionally, high levels of SOC are related to higher body appreciation among adolescents (Latzer, Weinberger-Litman, Spivak-Lavi &

Tzischinsky, 2019). Further, SOC is developed during childhood and adolescence. Fully development of SOC, however, occurs approximately at the age of 30 (Antonovsky, 1987). As previously stated, research on body image has predominantly addressed young women (Choukas-Bradley et al., 2019; Strubel et al., 2018; Veldhuis et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020), undermining the effect of body image concerns in men. However, research conducted among both men and women indicate that women and girls, to a greater extent, struggle with body dissatisfaction than men and boys do (Conner et al., 2004; Gonzaga, Claumann, Scarabelot, Silva & Pelegrini, 2019), and that women and girls are more appearance oriented than men and boys (Rutledge et al., 2013).

Body image concerns are especially occurring in western countries. Research suggests that women tend to strive for a slim body, while men tend to strive for a muscular body (Conner et al., 2004; SturtzSreetharan et al., 2020). Men’s tendency to strive for a muscular body is linked to low self-esteem, anxiety, depression and upper body dissatisfaction

(SturtzSreetharan et al., 2020). Body image disturbance among women is related to depressive symptoms, anxiety and low self-esteem (Sherlock & Wagstaff, 2019).

Body satisfaction in both male and female adolescents is related to physical activity; a low degree of body satisfaction predicts lower levels of physical activity (Neumark-Sztainer, Paxton, Hannan, Haines & Story, 2006). Additionally, high levels of SOC in adolescents are related to high levels of physical activity (Moksnes et al., 2012). Further, high SOC is

associated with weight satisfaction in both men and women (Swan, Bouwman, Hiddink, Aarts & Koelen, 2016).

2.3 Social media and body appreciation

In line with the complexity of body image, and given that social media constantly changes and evolves, the associations between social media and body appreciation has been shown to be ambiguous. Previous research has shown that the more time spent on Instagram, the more body image disturbance women experience (Sherlock & Wagstaff, 2019). However, research has also suggested that the way people use social media might be more predictive of body image than the time spent on social media (Choukas-Bradley et al., 2019; Stein, Krause & Ohler, 2019). For instance, exposure to body positive content on Instagram have been shown to improve women’s body satisfaction, body appreciation, happiness, and confidence (Cohen et al., 2019). On the contrary – viewing images of beauty and fitness increases body image disturbance (Sherlock & Wagstaff, 2019). Exposure to body neutral content does neither increase, nor decrease body satisfaction or body appreciation (Cohen et al., 2019). This finding could perhaps explain similar non-relationships – research on the matter has also suggested that there is no relationship between weight satisfaction and the browsing of strangers’ profiles and photos on Instagram (Stein et al., 2019).

Recent research has shown that there is no relationship between Facebook usage and women’s body image (Strubel et al., 2018). However, other research on Facebook and body image have shown that there, in fact, is an existing relationship. Women, people who spend more time on Facebook, and people who are more emotionally attached to Facebook are more oriented towards appearance. People who have more friends on Facebook also view their bodies in a more positive way (Rutledge et al., 2013).

Appearance-related social media consciousness, that is, thoughts and feelings regarding how attractive one is to a social media audience, is related to body image disturbance (Choukas-Bradley et al., 2019). However, deliberate selection and posting of selfies are associated with body appreciation in young women (Veldhuis et al., 2020).

The theory SOC consists of three parts; comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness (Antonovsky, 1987). Comprehensibility refers to the extent stimuli is perceived as information that is ordered, structured, consistent, and clear. People with high sense of comprehensibility are likely to be able to cope with experiences in life. These people are also likely to expect future experiences to be predictable to some extent and are able to perceive unpredicted happenings as understandable and comprehensible. On the contrary, people with low sense of comprehensibility are likely to perceive negative experiences as occurring often and believes that these things will continue to occur often in the future (Antonovsky, 1987). In a context of social media and body appreciation, this kind of stimuli could arise from social media, with messages about for example norms and ideals regarding bodies. Manageability refers to the extent resources are perceived to be enough to meet the demands that are set by the stimuli in the external, or internal, environment. People with a high sense of manageability are likely to be able to feel control over things that happens and are likely to be able to cope with such experiences. People with a low sense of manageability, on the other hand, might feel victimized and unfairly treated (Antonovsky, 1987). In this context, meeting demands could refer to living up to the norms and body ideals viewed in social media. Meaningfulness, which is the third component of the theory, refers to the extent life emotionally makes sense, and how much emotional investment and energy is worth spending on problems and demands. People with a high sense of meaningfulness are likely to welcome challenges and seek meaning in them, rather than seeing the challenges as burdens not worth investing energy in (Antonovsky, 1987). In a social media context,

research has shown that using Facebook is perceived as a less meaningful activity than browsing the internet and refraining from using social networking sites, which in turn leads to lowered positive mood (Yuen et al., 2019).

Research conducted on social media usage and body image has seldomly been conducted with a public health perspective, with several reports highlighting this knowledge gap, by emphasizing the need for development of interventions aimed for larger groups of people (Cohen et al., 2019; Essayli et al., 2017; Halliway, 2015; Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2006; Veldhuis et al., 2020). For example, health workers should instead of focusing on pathologic aspects of body image and social media, rather focus on factors that contribute to health (Veldhuis et al., 2020). As previously mentioned, there is an association between high SOC and lower usage of smartphones for social interaction (Sharabi et al., 2016). Additionally, high levels of SOC are related to body appreciation among adolescents, and with weight

satisfaction in adults (Latzer et al., 2019; Swan et al., 2016). Thus, studying social media usage and body appreciation through SOC could contribute to reducing this knowledge gap. Because the topic mostly have been studied in the field of psychology (Tylka &

Wood-Barcalow, 2015a), much of the literature focus on pathology and the negative aspects of body image (Choukas-Bradley et al., 2019; Conner et al., 2004; Gonzaga et al., 2019; Sherlock & Wagstaff, 2019; Stein et al., 2019). In order to not simply prevent disease and negative body image – promoting positive body image could be an important strategy for the public health sector. Promoting body acceptance could, for instance, result in higher participation in health-related behaviours, and thus – healthier lifestyles. Furthermore, taking advantage of social media platforms could be a time- and cost-effective way to reach a large population (Cohen et al., 2019). In sum, there is a need for a public health perspective when examining social media usage and body appreciation – and a need for health promoting interventions for the adult population as well as for adolescents.

2.4 Problem formulation

The public health agency in Sweden has examined body image of adolescents during the last three decades (Danielson & Marklund, 2000). However, there are no statistics regarding adult’s body image – even though research points out that body image can be a concern even in adulthood. Body satisfaction positively influences mental health and well-being, while body dissatisfaction constitutes a risk factor for mental ill-health (Halliway, 2015; Stice, 2002). Mental well-being is an important topic for the public health (Folkhälsomyndigheten, 2020a). Further, the UN (2015) highlights that targeting indicators of health can contribute to ensuring health and well-being.

There seems to be inequalities in body appreciation, as previous research has found

differences across gender and age (Halliway, 2015; Conner et al., 2004; Gonzaga et al., 2019). Furthermore, social media influences health in various ways – both negatively and positively (Shayka & Christakis, 2017). Studies have seldomly solely focused on positive aspects of body image. Therefore, examining social media and body appreciation through a framework using SOC could potentially highlight the positive aspects, and thus, shed new light on the subject. From a public health perspective, it could be considered important addressing how

promoting body appreciation could be achieved. The majority of the Swedish adult

population uses social media (Statistics Sweden, 2019). However, it appears that there is a knowledge gap when it comes to social media usage and body appreciation in the adult

Swedish population. Thus, identifying whether there is such an association on this population could be a starting point in order to promote health within this topic. This could further enable identification of health promoting factors for body appreciation and within social media usage, which could be beneficial for the public health. Hence, this study intends to investigate potential associations between social media usage and body appreciation.

3 AIM

The aim was to examine if there is a relationship between social media usage and body appreciation among Swedish adults, and to investigate if there are any differences across gender on this relationship. Further, the aim was to examine whether this potential

relationship is evident after controlling for age, gender, physical activity, sedentary lifestyle, and viewing of body positive content.

3.1 Research questions

• Is there a relationship between social media usage and body appreciation?

• Is there a difference across gender on the potential relationship between social media usage and body appreciation?

• Is there a relationship between social media usage and body appreciation after controlling for age, gender, physical activity, sedentary lifestyle, and viewing of body positive content?

3.2 Study hypothesis

The hypothesis proposed was that there is a negative relationship between social media usage and body appreciation, and that this relationship remains after controlling for age, gender, physical activity, sedentary lifestyle, and viewing of body positive content. Further, it was hypothesised that this relationship is stronger among women.

4 METHODS AND MATERIAL

In this chapter, methodological choices, materials used, and procedures are explained.

4.1 Methodological approach and study design

To answer the aim and research questions, a quantitative method was applied. When using a quantitative method, an objective approach is strived for. Testing of theories are conducted by collecting and analysing numerical data (Bryman, 2012). Often, questionnaires are used to collect this type of data (Bruce, Pope & Stanistreet, 2018). This study was based on a

positivistic approach, which implies that science and knowledge are based on reasoning and on rational thought. Positivism assumes an objective approach. Thus, the phenomena of interest is observed from a distance. The result are solely based on actual observations (Bruce

et al., 2018). A deductive approach was applied in this study. In deduction, knowledge is expanded by testing of hypotheses with empirical data. This means that, on a theoretical basis, a hypothesis is formulated, and observations are made. These observations can either deny or confirm the hypothesis (Bruce et al., 2o18). A cross-sectional study design was applied. Distinctive for a cross-sectional design is that all variables are measured at the same time, at a given time-point. The cross-sectional design can be used in order to detect

associations between variables in a population (Creswell & Creswell, 2018; Merrill, 2013).

4.2 Sample

The target population consisted of Swedish adults who have Facebook accounts. The

inclusion criteria were that participants were Swedish speaking and were at least 18 years old. Targeting a large source population was deemed suitable in this case, as the COVID-19 virus affected the possibilities to reach out to potential participants. Using a large source

population presumably increased the chances of receiving an appropriate sample size. The sample was a snowball sample. A snowball sample is distinguished by finding people from the population, who in turn can use their networks to find more people from the same population (Bruce et al., 2018). This was evident in this study, since the questionnaire was shared on the author’s Facebook account, and was then shared by ten additional Facebook users, on their own timelines. In this way, the questionnaire reached more people from the population. A snowball sample is not a random sample, and thus, likely not representative for the population. However, it may help identify people from the population (Bruce et al., 2018). Because there was no way to randomly select a sample from the target population, this

sample technique was deemed appropriate.

4.3 Data collection

The cover letter and the questionnaire were in Swedish and created in Google Forms (appendix A-D). After receiving approval from the supervisor, the questionnaire was tested by two peers, who gave input and shared their experiences and spontaneous reactions of answering the questionnaire. The questionnaire – including the cover letter – was shared on the author’s Facebook page on the 21st of April 2020. A post was published, where it was

stated that the author of this study was working on a degree project regarding social media and body appreciation. The post also included the link to the questionnaire. Further, the Facebook post was shared by ten people. The data collection proceeded for seven days, and ended on the 28th of April 2020. The response rate – which is how many percent of those in

the available sample, from whom data was collected (Bruce et al., 2018) – is unknown, as it cannot be established how many of those who received the questionnaire actually answered it. Further, it was not possible to determine how many started filling in the questionnaire without completing it. Due to the COVID-19 virus, questionnaires could not be handed out in person, thus, using Facebook to reach participants was deemed an appropriate strategy.

4.4 Measures

Age was measured by simply asking how old the respondents were, as an open question; that is, participants were free to write how old they were and did not get any specified response alternatives (Bruce et al., 2018). Gender was measured by asking the respondents which gender they identify with, with the options man, woman, or I do not identify as either man or woman (appendix B; appendix D). No other genders were included, in order to decrease the risk of receiving identifiable responses. Measures of physical activity, sedentary lifestyle, body positive content, social media usage, and body appreciation are described in the following chapters.

4.4.1 Physical activity

Physical activity was measured using two questions from the national public health survey in Sweden (Folkhälsomyndigheten, 2020b). The first question regarded physical exercise, and participants were asked to estimate how much time in a regular week they exercised, with response alternatives ranging from 0 minutes/no time to more than 2 hours. The second question regarded everyday activities, and participants were asked how much time, in a regular week, they performed everyday activities. Response alternatives ranged from 0 minutes/no time to more than five hours.

4.4.2 Sedentary lifestyle

Sedentary lifestyle was measured by asking participants to estimate how much they sit in average in a day, with response alternatives ranging from more than 15 hours to never (appendix B; appendix D). This question was adopted from the national public health survey in Sweden (Folkhälsomyndigheten, 2020b).

4.4.3 Body positive content

To measure viewing of body positivity content, a question from previous research was used (Cohen et al., 2019). The question read: “How often do you currently view body positive content on social media in your everyday life?”, with the response alternatives never, seldom, sometimes, often and always. Because the question was written in English, it had to be translated into Swedish. The back-translation technique was used, which includes

translating the original content to the intended language, and then translating the content back to the original language (Lemoine et al., 2018). The author of this study translated the question to Swedish, and then consulted two persons highly fluent in both English and Swedish, who were unaware of the wording of the original question. The consultants then translated the Swedish question back to English, resulting in a very similar question as in the original form. After discussing the difference, one word in the Swedish version was changed in order to completely attain to the same meaning as the English question (appendix B; appendix D).

4.4.4 Social media usage

In order to measure time spent on social media, a question was inspired by Sherlock and Wagstaff (2019). The question read: “During a regular week, how much time do you spend on social medias?” with response alternatives ranging from less than ten minutes to more than three hours (appendix B; appendix D).

General social media usage was measured with the general social media usage subscale, which is a subscale from the media and technology usage and attitudes scale (Rosen, Whaling, Carrier, Cheever & Rokkum, 2013). The scale consists of nine items, with ten response alternatives ranging from never to all the time. Unfortunately, one of the alternatives were unintentionally excluded from the questionnaire, and thus, only nine

response alternatives were represented. The alternative not included in the questionnaire was several times a day. Because the subscale originally was written in English, it had to be translated into Swedish, and was translated using the back-translation technique, as described above. In this case, the author of this study translated the subscale into Swedish, and then consulted the two persons highly fluent in both English and Swedish, who were unaware of the wording of the original version. Next, the consultants translated the Swedish version of the subscale back to English, resulting in almost identical wordings as in the original form. After discussion, two words in the Swedish version was changed in order to fully capture the context of the English version (appendix B; appendix D).

4.4.5 Body appreciation

Body appreciation was measured with the body appreciation scale-2 in Swedish (BAS-2 in Swedish). The scale was originally in English and developed to highlight positive body image – body appreciation, rather than body dissatisfaction. Additionally, BAS-2 was developed to enable measuring both women and men. The English version of BAS-2 shows good validity and reliability among American college and community women and men (Tylka & Wood-Barcalow, 2015b). The Swedish version of BAS-2 have shown good validity and reliability in adolescent girls and boys – and in young women and men (Lemoine et al., 2018; Gattario & Frisén, 2019). BAS-2 in Swedish has ten items, and response alternatives on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from never to always. The scale measures participants’ acceptance of, favourable opinions of, and respect for their bodies. However, two items of BAS-2 in Swedish was modified, to further highlight the positive approach, and to ensure that ethical aspects were considered. The original question “I feel that my body has at least some good qualities” was modified into “I feel that my body has good qualities”, and the original question “I feel like I am beautiful even if I am different from media images of attractive people (e.g., models, actresses/actors)” was modified into “I feel like I am beautiful” (appendix B; appendix D).

4.5 Processing of data

All registered answers in Google Forms was exported to Google Spreadsheets. From there, the spreadsheet was further exported to Microsoft Excel. The spreadsheet in the excel format

was then imported to IBM SPSS Statistics version 24. When all data had been imported, the questions of the questionnaire constituted the variables. The response alternatives were referred to as categories, and the categories were coded with numerical values. In addition, any missing values was reported for each variable in the result. Missing values occurs when participants chooses not to answer, or misses to answer, specific questions (Bryman, 2012). General social media usage and time spent on social media, respectively, were the

independent variables. An independent variable is a variable that is presumed to be causing something, independently of other factors (Field, 2018). Body appreciation was the

dependent variable; a dependent variable is the presumed effect, and is dependent of the independent variable (Field, 2018). Age, gender, physical activity, sedentary lifestyle and viewing of body positive content was confounding factors. A confounding factor is a variable that is related to both the independent and dependent variable but is not on the causal pathway between the independent and dependent variable (Bruce et al., 2018).

General social media usage was measured using a scale, including nine questions with nine response alternatives each (appendix B; appendix D). These nine questions were summed up by creating an index. In order to make sure that an index was appropriate, the reliability was assessed. The reliability of a measure refers to how consistent and stable a measurement is (Merrill, 2013). Internal consistency assesses to what extent items in an index measure the same concept. There are several ways to assess internal consistency, one of which being Cronbach’s Alpha – α (Bannigan & Watson, 2009). In this study, Cronbach’s α was assessed, which indicates how well each item in the scale measures the phenomenon it is supposed to measure. The a value can range from zero to one; zero implying that the items are not related at all, while one indicates a perfect relation. A common interpretation is that an α value above 0.8 is acceptable (Field, 2018). After assessing the reliability, it was concluded that the

reliability was good (α=0.862). Since the reliability of the scale was good, an index could be created. The index consisted of the nine questions from the general social media usage subscale, with scores ranging from zero to 72. A low score indicated low usage of social media, while a high score indicated high usage of social media (Rosen et al., 2013).

Body appreciation was measured using a scale consisting of ten questions with five response alternatives (appendix B; appendix D). Before creating an index, the reliability was assessed. The reliability was considered good (α=0.951). The ten questions were summed up into an index, and scores ranged from zero to 40. A low score indicated low body appreciation and a high score indicated high body appreciation (Tylka & Wood-Barcalow, 2015b).

The variable physical activity was created by making an index out of the variables physical exercise and everyday activities. In order to do so, the variables had to be recoded (table 1). The category of each variable was recoded so that the middle value of each category

represented the new code. For example, less than 30 minutes was recoded into 15, 30-59 was recoded into 45 and so on. The two questions were made into an index, using the algorithm: physical exercise x2 + everyday activities = activity minutes (Folkhälsomyndigheten, 2016). According to Folkhälsomyndigheten (2016), physical exercise should be counted twice as it is a more intense form of activity than everyday activities. The index was made in order to enable measuring physical activity and everyday activities together, and thus, estimating the

total number of activity minutes per week. The estimation of activity minutes is used to assess whether the Swedish recommendation for physical activity is achieved – that is 150 activity minutes per week (Folkhälsomyndigheten, 2016).

Table 1: Recoding of physical exercise and everyday activities.

Physical activity Original value Recoded valuea

Physical exercise 0 min <30 min 30-59 min 60-89 min 90-119 min >120 min à à à à à à 0 min 15 min 45 min 75 min 105 min 120 min

Everyday activities 0 min

<30 min 30-59 min 60-89 min 90-149 min 150-299 min >300 min à à à à à à à 0 min 15 min 45 min 75 min 120 min 225 min 300 min

a Recoding based on the original value’s middle value.

Sedentary lifestyle was, in accordance with Folkhälsomyndigheten (2016), presented in three groups; in an average day, sitting down: 75% or more of the time, 50% of the time, and 25% or less of the time. In order to do so, the original codes were recoded. The first group, 75% or more, consisted of the three categories that indicated sitting more than ten hours; the second group, 50%, consisted of the category seven to nine hours; the third group, 25% or less, consisted of the three categories that indicated sitting six hours or less. However, in the inferential analyses, the original codes were used, in order to obtain as accurate results as possible.

4.6 Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the total sample, and to separately describe

genders. This was done using frequencies, percentages, ranges, medians, means and standard deviations. Any missing data was reported. Furthermore, inferential statistics were used in order to analyse the data and to answer the research questions. When performing inferential analyses, the level of significance adapted in this study was <0.05. The level of significance is the acceptable statistical risk of arriving at the wrong conclusion, by believing that there is an effect in the population, when in fact there is not. When adapting the <0.05 level of

In order to answer the first research question, “Is there a relationship between social media usage and body appreciation?”, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used, which may be used when examining a relationship between two variables. These variables should be continuous, that is, have an equal distance between each value. The variables general social media usage, time spent on social media, and body appreciation were used. Additionally, the assumption of additivity and linearity should be met, and involves that scores on the dependent variable is linearly related to scores on the independent variable, which can be assessed by creating a scatterplot. Furthermore, the assumption of normality should be met. This refers to residuals (i.e. the difference between predicted and observed values) of a model being normally distributed (Field, 2018). Normality was assessed by examining skewness and kurtosis of each variable. Values of skewness and kurtosis between –2 and 2 indicates that residuals are normally distributed (George & Mallery, 2019). Pearson’s correlation

coefficient, r, can identify the strength and direction of a relationship. A relationship can have an effect size between –1 and 1. An r value of –1 implies a perfect negative relationship, while an r value of one implies a perfect positive relationship. Furthermore, an r value of zero implies that there is no relationship between the two variables. Moreover, a negative

relationship indicates that high values of the one variable is related to low values of the other variable; a positive relationship indicates that high values of the one variable is related to high values of the other variable. The strength of the association can vary and have small (r=0.1-0.29), medium (r=0.3-0.49), and large (r≥0.5) effect sizes; these cut-offs are the same for negative associations (Field, 2018).

The second research question, “Is there a difference across gender on the potential relationship between social media usage and body appreciation?” was answered by

conducting stratified correlation analyses. This was done by splitting the variable gender and then separately conducting Pearson’s correlation coefficient analyses and using the variables general social media usage, time spent on social media, and body appreciation.

Further, the third research question, “Is there a relationship between social media usage and body appreciation after controlling for age, gender, physical activity, sedentary lifestyle, and viewing of body positive content?” was answered by conducting hierarchical multiple linear regression analyses. This analysis is conducted in order to assess the role of potential confounding, by first assessing how much variance – that is change – in the dependent variable the independent variable accounts for, and then assessing how much more variance is accounted for when including potential confounding factors – or predictors (Field, 2018). When conducting a regression analysis there should be an appropriate sample size, and the formula N ≥ 104+k might be used. N represents the number of respondents needed, and k represents the number of predictors used in the analysis (Green, 1991). In this case, time spent on social media, age, gender, physical activity, sedentary lifestyle and viewing of body positive content was used as predictors, and thus, a sample size of at least 11o would be required. Since the sample size in this study was 153, a regression analysis could be

conducted. Based on the stratified correlations, a regression analysis was also conducted solely among women. Conducting a regression analysis solely for women was possible, as 118 women answered the questionnaire. However, a separate analysis could not be performed among men, since only 35 men answered the questionnaire. This second regression analysis was conducted in order to produce as accurate results as possible.

Before conducting the analyses, it was assessed whether assumptions were met. These assumption includes: additivity and linearity, independence of errors, homoscedasticity, normality, and multicollinearity (Field, 2018).

The assumption of additivity and linearity is crucial for linear regression, as the regression is based on the assumption that scores on the dependent variable is linearly related to scores on the independent variable. When several predictors are used to describe the dependent

variable, the effects are best explained by adding the effects together. Additivity and linearity can be assessed by creating a scatterplot of predicted values of a model and the errors in the model (Field, 2018). The assumption of independence of errors is important in order for significance tests, standard errors, and confidence intervals to be accurate. To assess whether errors are independent, the Durbin-Watson test can be used. This test compute values

ranging from zero to four; a value of two indicates that errors are independent. A value greater than two indicates a negative correlation, whereas a value below two indicate a positive correlation. The assumption can be considered met for values between one and three are acceptable (Field, 2018). Homoscedasticity is another assumption that should be

considered. Violating this assumption can lead to inaccurate results. The variance in the dependent variable should not differ across the values of the predictor variable.

Homoscedasticity is assessed using the same scatterplot as for assessing additivity and linearity (Field, 2018). Moreover, normality refers to that residuals in the model should be normally distributed. As previously mentioned, skewness and kurtosis values between –2 and 2 are acceptable values for normal distribution (George & Mallery, 2019). Lastly,

multicollinearity also needs to be assessed. Multicollinearity refers to strong correlations between predictors; multicollinearity makes it difficult to assess the importance of a

predictor that is highly correlated to another predictor. In order to assess multicollinearity, the two concepts variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance are examined. A VIF value considerably below ten and a tolerance value greater than 0.2 indicates that substantial multicollinearity does not occur. Further, if the average VIF value is very close to one, this suggest that there are no problems with multicollinearity (Field, 2018). After these

assessments had been done, it was concluded that a regression analysis could not be performed using the independent variable general social media usage. Thus, only the independent variable time spent on social media was used in the regression analyses. When conducting a multiple linear regression, using a hierarchical method, predictors of the independent variable are entered in blocks (Field, 2018). When answering the third research question, the independent variable time spent on social media was entered in the first block. In the second block, the potential confounding factors were entered, that is, age, gender, viewing of body positive content, physical activity, and sedentary lifestyle. By doing this, it could be assessed whether including the potential confounding factors improved the ability to predict body appreciation, and thus, if the relationship between time spent on social media and body appreciation still was evident.

The multiple linear regression includes some test statistics needed in order to interpret the analysis. The adjusted R2 explains how much of the variance in the dependent variable can be

accounted for by the predictors. The adjusted R2 adjusts for the number of predictors in the

coefficient, B, indicates the strength of an association between a predictor and the dependent variable, using a unit change in the predictor (e.g. a year for the variable age) to explain this association (Field, 2018). The 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for B is the range, calculated around the sample value of B, that includes the true population value for B (Bruce et al., 2018; Field, 2018). The standard error for B (SE B) indicates how much the B values vary across samples. The size of the standardized regression coefficient, b, indicates the strength of an association between a predictor and the dependent variable, using standard deviations to indicate this association. Lastly, the F value determines whether the regression model improves the ability to predict the dependent variable – the larger the F value, the better the model. An F value of zero implies that the model did not improve the prediction of the dependent variable (Field, 2018). All analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics.

4.7 Ethical considerations

When conducting research, four principles are to be considered. These principles involve requirements of: information, consent, confidentiality, and utilization (Vetenskapsrådet, 2002). These ethical principles have been developed in order to protect participants from taking harm from any research conducted (Swedish research council, 2017).

The first requirement involves giving potential respondents information regarding the aim of the study. Further, information regarding the voluntariness to participate, the possibility to discontinue, and the presumed possible positive and negative effects that participating in the study could entail (Ventenskapsrådet, 2002). This was ensured by firstly addressing in the Facebook post that the degree project regarded social media usage and body appreciation. Secondly, a cover letter to the questionnaire was provided, where information about the study’s aim was provided. Information was also provided specifying that it was voluntary to participate and that it was possible to discontinue at any time. Potential advantages and disadvantages related to participating was highlighted in the cover letter. The potential disadvantage of participating was that some questions could be considered sensitive. To ensure that participants felt calm, it was highlighted that the answers would be kept

confidential and that participants would be anonymous. The presumed potential benefits of participating that were mentioned was that participants would contribute to increased knowledge regarding the topic, and that they would have the opportunity to reflect on their social media usage and body appreciation. Further, it was stated were the participants would be able to read the completed thesis (appendix B; appendix D).

The second requirement regards that participants have the right to decide over whether or not taking part in the study. This is ensured by obtaining consent from the participants (Vetenskapsrådet, 2002). In the cover letter, it was stated that by filling in the questionnaire, the participants gave their consent. Furthermore, this requirement involves that participants can withdraw at any time without any negative consequences (Vetenskapsrådet, 2002). As previously mentioned, it was stated in the cover letter that participants could discontinue at any time (appendix B; appendix D).

The third requirement involves that all data should be kept as confidential as possible and that all personal data should be kept in a way that keeps unauthorised persons from

accessing the data. Further, it requires that results should be presented in a way that prevents others from identifying participants, in order to keep participants anonymous (Swedish research council, 2017; Vetenskapsrådet, 2002). The data was stored in a password-protected Google account and on a password-protected laptop. Further, to ensure that no participants would be identified, no questions were asked that could possibly identify the participants. Moreover, it was stated in the cover letter that the results would be presented in a way that further would keep any participant from being identified (appendix B; appendix D).

Finally, the fourth requirement involves that gathered data are only to be used for the purpose of the current study (Vetenskapsrådet, 2002). This was established by addressing that data only would be used for the purpose of this study, and then would be deleted when the thesis was completed (appendix B; appendix D).

The questions about body appreciation was from the BAS-2 in Swedish (Lemoine et al., 2018). The scale was developed from the first version of BAS, which was created to measure body appreciation. BAS-2 was developed in order to highlight the positive aspects of body image (Tylka & Wood-Barcalow, 2015b). However, as previously mentioned, two items of BAS-2 in Swedish was modified in this study, to further highlight the positive approach, and to ensure that ethical aspects were considered – that the participants did not take harm in participating in the study (appendix B; appendix D). Furthermore, no question in the questionnaire was made obligatory. This, in order to give participants the option to skip a question if they would be uncomfortable answering it.

5 RESULTS

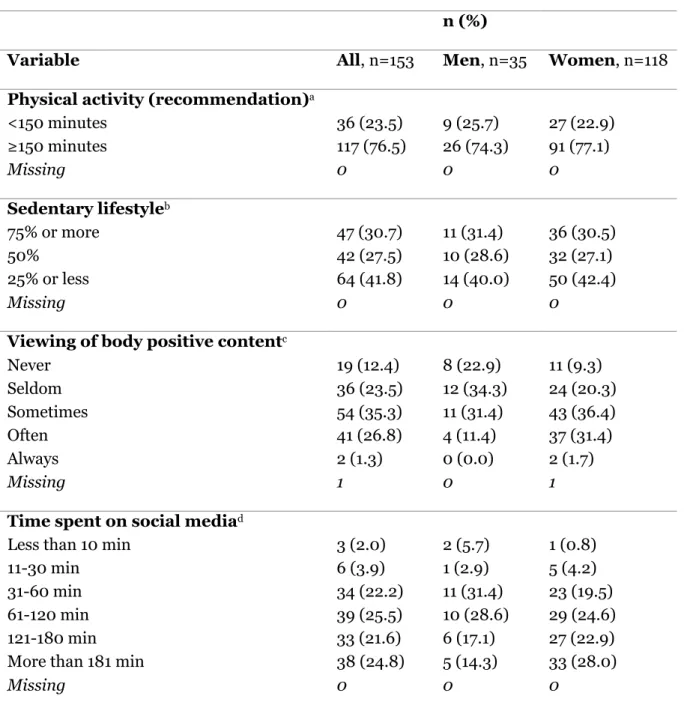

Participants were 153 persons ranging in age from 19 to 70 years (M=37.97, SD=14.22; table 3). The sample consisted of three quarters women (n=118, 77.1%) and one quarter men (n=35, 22.9%). All participants identified as either man or woman. Participants varied in physical activity, as activity minutes ranged from zero to 540 minutes per week, with three quarters of the participants reaching the recommendation of 150 minutes (table 2). Further, the majority of participants were sitting less than 25% of the day. The majority of participants spent more than one hour on social medias per week. Further, body positive content was viewed to a varying extent. However, the majority viewed body positive content to at least some extent (table 2).

Table 2: Descriptive statistics of categorical variables in the total sample, in men, and in women.

n (%)

Variable All, n=153 Men, n=35 Women, n=118

Physical activity (recommendation)a

<150 minutes ≥150 minutes Missing 36 (23.5) 117 (76.5) 0 9 (25.7) 26 (74.3) 0 27 (22.9) 91 (77.1) 0 Sedentary lifestyleb 75% or more 50% 25% or less Missing 47 (30.7) 42 (27.5) 64 (41.8) 0 11 (31.4) 10 (28.6) 14 (40.0) 0 36 (30.5) 32 (27.1) 50 (42.4) 0

Viewing of body positive contentc

Never Seldom Sometimes Often Always Missing 19 (12.4) 36 (23.5) 54 (35.3) 41 (26.8) 2 (1.3) 1 8 (22.9) 12 (34.3) 11 (31.4) 4 (11.4) 0 (0.0) 0 11 (9.3) 24 (20.3) 43 (36.4) 37 (31.4) 2 (1.7) 1

Time spent on social mediad

Less than 10 min 11-30 min

31-60 min 61-120 min 121-180 min More than 181 min Missing 3 (2.0) 6 (3.9) 34 (22.2) 39 (25.5) 33 (21.6) 38 (24.8) 0 2 (5.7) 1 (2.9) 11 (31.4) 10 (28.6) 6 (17.1) 5 (14.3) 0 1 (0.8) 5 (4.2) 23 (19.5) 29 (24.6) 27 (22.9) 33 (28.0) 0

aActivity minutes in an average week by recommendation, measured using the variables physical

exercise and everyday activities (Folkhälsomyndigheten, 2016).

bTime sitting down in an average day, expressed in percent. cCurrent frequency of viewing body positive content.

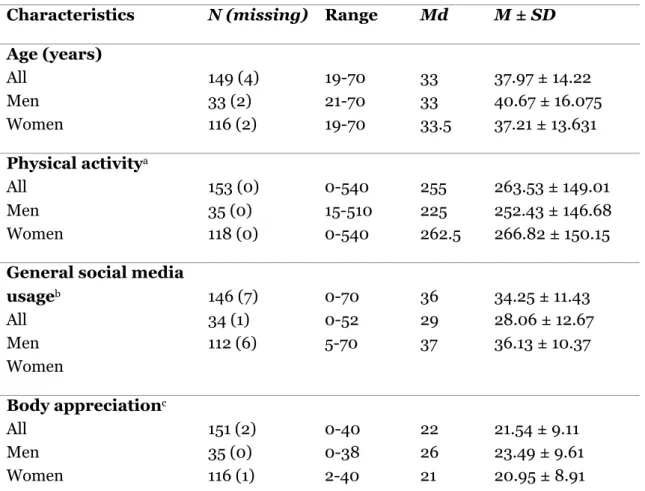

Table 3: Descriptive statistics of continuous variables in the total sample, in men, and in women.

Characteristics N (missing) Range Md M ± SD

Age (years) All Men Women 149 (4) 33 (2) 116 (2) 19-70 21-70 19-70 33 33 33.5 37.97 ± 14.22 40.67 ± 16.075 37.21 ± 13.631 Physical activitya All Men Women 153 (0) 35 (0) 118 (0) 0-540 15-510 0-540 255 225 262.5 263.53 ± 149.01 252.43 ± 146.68 266.82 ± 150.15

General social media usageb All Men Women 146 (7) 34 (1) 112 (6) 0-70 0-52 5-70 36 29 37 34.25 ± 11.43 28.06 ± 12.67 36.13 ± 10.37 Body appreciationc All Men Women 151 (2) 35 (0) 116 (1) 0-40 0-38 2-40 22 26 21 21.54 ± 9.11 23.49 ± 9.61 20.95 ± 8.91 Abbreviations: N=sample size, Md=median, M=mean, SD=standard deviation.

a Activity minutes in an average week, measured using the variables physical exercise and everyday

activities (Folkhälsomyndigheten, 2016).

b Measured with the scale general social media usage subscale (Rosen et al., 2013). c Measured with the body appreciation scale (Tylka & Wood-Barcalow, 2015b).

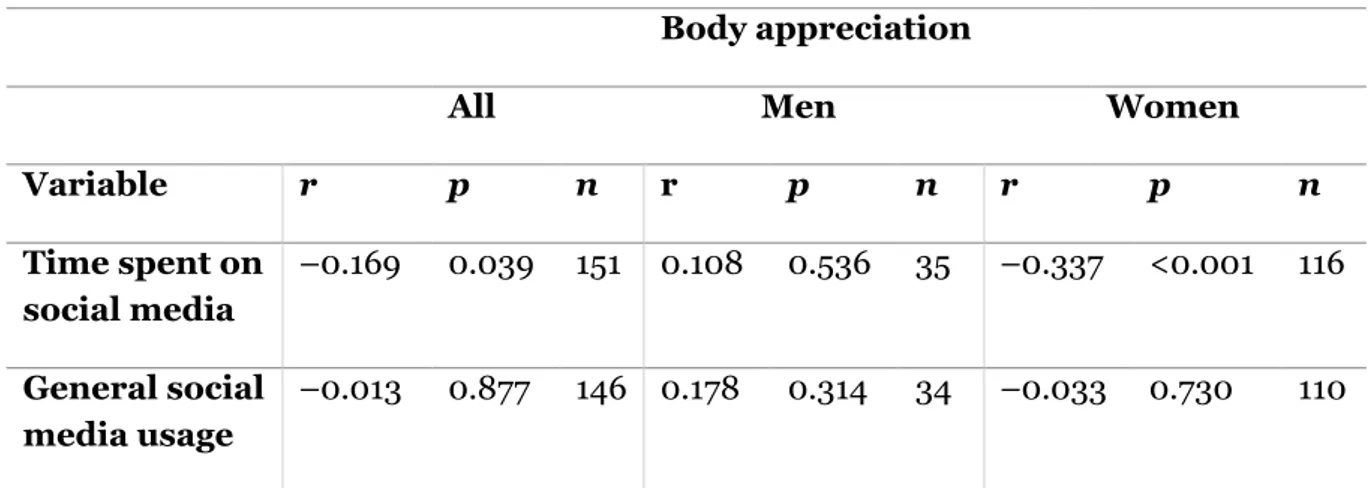

5.1

Relationship between social media usage and body appreciation

There was a small negative relationship between body appreciation and time spent on social media, indicating that the less time spent on social media, the better body appreciation the participants had (r=–0.169, p=0.039; table 4). Furthermore, there was no relationship between general social media usage and body appreciation (r=–0.013, p=0.877).

5.1.1 Gender specific relationships

Among men, there was a positive relationship between time spent on social media and body appreciation, indicating that the more time spent on social media, the better body

appreciation the men tended to have (r=0.108, p=0.536; table 4). However, this relationship was small and not statistically significant. Further, there was a medium negative relationship between time spent on social media and body appreciation among women (r=–0.337,

appreciation tended to be. There was a positive relationship between general social media usage and body appreciation among men, indicating that the more the men used social media, the better their body appreciation tended to be (r=0.178, p=0.314). However, this relationship was small and statistically nonsignificant. Moreover, there was no relationship between general social media usage and body appreciation among women

(r=–0.033, p=0.730; table 4).

Table 4: Correlations between social media usage and body appreciation in total sample, and

separately in men and women, using Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

Body appreciation

All Men Women

Variable r p n r p n r p n Time spent on social media –0.169 0.039 151 0.108 0.536 35 –0.337 <0.001 116 General social media usage –0.013 0.877 146 0.178 0.314 34 –0.033 0.730 110

Abbreviations: r=Pearson’s correlation coefficient, p=probability value, n=sample size.

The assumptions of additivity and linearity and of normality were assessed, and revealed that correlation analyses using Pearson’s correlation coefficient could be performed. Scatterplots revealed that there were no curvilinear relationships. Furthermore, all values of skewness and kurtosis were between -2 and 2. Hence, the assumption of normality was also met.

5.2 Relationship between social media usage – time spent on social

media – and body appreciation controlled for confounding

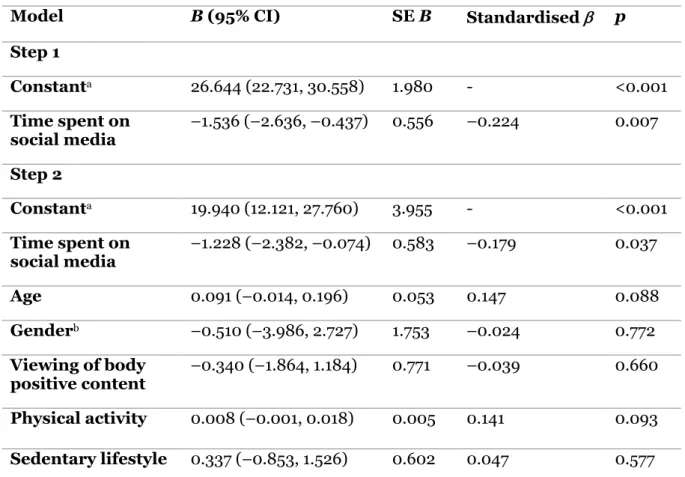

A hierarchical multiple linear regression was conducted to predict body appreciation based on time spent on social media, age, gender, viewing of body positive content, physical

activity, and sedentary lifestyle. The regression statistically significantly improved the ability to predict the body appreciation from the first step in the hierarchy to the second step (F(6,139)=2.757, p=0.015; table 5).

The time spent on social media accounted for 4,4% of the variation in body appreciation (adjusted R2=0.044; table 5). However, when analysing time spent on social media, age,

gender, viewing of body positive content, physical activity, and sedentary lifestyle, these predictors accounted for 6.8% in body appreciation (adjusted R2=0.068). Hence, age, gender,

viewing of body positive content, physical activity, and sedentary lifestyle accounted for 2.4% of the variance in body appreciation. Of the variance in body appreciation, 93.2% remains unaccounted for.

In the first step of the hierarchy, as the time spent on social media increased by one standard deviation, body appreciation decreased by 0.224 standard deviations, indicating a negative relationship; less time spent on social media was associated with better body appreciation (Standardised b=–0.224, p=0.007; table 5). In the second step of the hierarchy, after adjusting for age, gender, viewing of body positive content, physical activity, and sedentary lifestyle, the effect that time spent on social media had on the variance in body appreciation changed; as the time spent on social media increased by one standard deviation, body appreciation decreased by 0.179 standard deviations (Standardised b=–0.179, p=0.037). Thus, there still was a negative relationship between time spent on social media and body appreciation after controlling for confounding.

Table 5: Hierarchical multiple regression analysis of predictors of body appreciation, n=146.

Model B (95% CI) SE B Standardised b p

Step 1 Constanta 26.644 (22.731, 30.558) 1.980 - <0.001 Time spent on social media –1.536 (–2.636, –0.437) 0.556 –0.224 0.007 Step 2 Constanta 19.940 (12.121, 27.760) 3.955 - <0.001 Time spent on social media –1.228 (–2.382, –0.074) 0.583 –0.179 0.037 Age 0.091 (–0.014, 0.196) 0.053 0.147 0.088 Genderb –0.510 (–3.986, 2.727) 1.753 –0.024 0.772 Viewing of body positive content –0.340 (–1.864, 1.184) 0.771 –0.039 0.660 Physical activity 0.008 (–0.001, 0.018) 0.005 0.141 0.093 Sedentary lifestyle 0.337 (–0.853, 1.526) 0.602 0.047 0.577

Note:in model 1, adjusted R2=0.044; in model 2, adjusted R2=0.068 and F(6,139)=2.757, p=0.015).

Abbreviations: B=unstandardized regression coefficient; CI=confidence interval; SE B=standard error for B; b=beta, standardized regression coefficient.

aConstant=the intercept, where the regression line crosses the y axis. bCoding: men=0, women=1.

After assessing the scatterplot of predicted values and errors of the regression model, the assumptions of additivity and linearity, and homoscedasticity were concluded to be met. Further, the Durbin-Watson test revealed a value of 1.769. Hence, the assumption of independent errors was met. The values of skewness and kurtosis for all variables were between –2 and 2, therefore, the assumption of normality was met. There was no prevalent problem with multicollinearity in the regression analysis. The VIF value of each predictor was just above one, and the tolerance value of each predictor was above 0.8. Further, the average

VIF was 1.133 – close to one. A regression analysis could not be performed using general social media usage as the independent variable, as the assumption of additivity and linearity was violated.

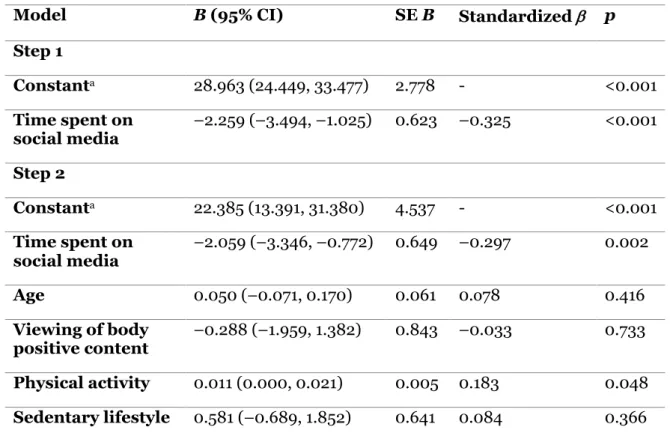

5.2.1 Relationship controlled for confounding among women

A hierarchical multiple linear regression solely conducted on women was also conducted to predict body appreciation among women, based on time spent on social media, age, viewing of body positive content, physical activity, and sedentary lifestyle. The regression statistically significantly improved the ability to predict body appreciation from the first step in the hierarchyto the second (F(5,107)=4.183, p=0.002; table 6).

Among women, the time spent on social media accounted for 9.8% of the variance in body appreciation (adjusted R2=0.098; table 6). However, when analysing time spent on social

media, age, viewing of body positive content, physical activity, and sedentary lifestyle, these predictors accounted for 12.4% in body appreciation (adjusted R2=0.124). Thus, age, viewing

of body positive content, physical activity, and sedentary lifestyle accounted for 2.6% of the variance in body appreciation. Additionally, 87.6% of the variance in body appreciation is accounted by other factors.

In the first step of the hierarchy among women, as the time spent on social media increased by one standard deviation, body appreciation decreased by 0.325 standard deviations,

indicating a negative relationship. Hence, less time spent on social media was associated with better body appreciation (Standardised b=–0.325, p<0.001; table 6). In the second step of the hierarchy, when adding age, viewing of body positive content, physical activity, and sedentary lifestyle, the effect time spent on social media had on the variance in body appreciation among women changed; as the time spent on social media increased by one standard deviation, body appreciation decreased by 0.297 standard deviations (Standardised b=–0.297, p=0.002). Thus, there still was a negative relationship between time spent on social media and body appreciation after controlling for confounding.

A scatterplot of predicted values and errors of the regression model revealed that the assumptions of both additivity and linearity, and homoscedasticity were met. The Durbin-Watson test revealed a value of 1.838. Thus, the assumption of independent errors was met. Furthermore, all values of skewness and kurtosis ranged between –1 and 1. Hence, the assumption of normality was met. Lastly, there were no problems with multicollinearity in the regression analysis conducted among women. The VIF value of each predictor was just above one. Additionally, all tolerance values were above 0.8, and the average VIF for women was 1.127, which is close to one. A regression analysis among women using general social media usage as the independent variable could not be performed, as the assumption of additivity and linearity was not met.