Evaluation of IP Portfolios

Author: Peder Veng Søberg, Ph.D. student at Baltic Business School, 39282 Kalmar, University of Kalmar (merging with Växjö University to become Linnaeus University), Sweden, Phone: +4551341155, E-mail: Peder.Soberg@hik.se

Abstract

As a result of an inquiry concerning how to evaluate IP (intellectual property) portfolios in order to enable the best possible use of IP resources within organizations, an IP evaluation approach primarily applicable for patents and utility models is developed. The developed approach is useful in order to discuss, visualize and align IPR issues with different management functions within the organization. Unlike existing approaches the present approach takes into account such value indicators as remaining lifetime, geographical range, broadness of scope and product strategic considerations of the organization owning the IP.

Introduction

In spite of the importance of the subject for many knowledge intensive companies, we still have not built IP (intellectual property) evaluation theory and approaches which are able to embrace core challenges such as, providing alerts if important IP is reaching the end of its lifetime, taking into account the geographical range of IP and facilitating active participation in the IP evaluation process across management functions. Previous attempts such as the one made by the Danish Patent and Trademark Organization when they developed the IP evaluation software named IP Score, have so far proved insufficient (according to knowledge intensive organizations who have been trying out the software).

The role of IP evaluation is not only to estimate the value of the IP portfolio, but also to facilitate discussion of IP issues in order to increase the awareness of IP in the organization and in order to align IP related activities across the organization. Finding the general value of the IP portfolio is not enough in order to make a good IP evaluation process. It is as important, if not more important, that the process facilitates fruitful discussions across the organization, enabling alignment of the IP related activities and strategies of the organization. This paper builds theory to this end and it speaks to the following themes within the 5th workshop on visualizing, measuring and managing intangibles and intellectual capital:

Managing and controlling inventions and innovations in companies and NPOs

Interactions between different functions of management like accounting, finance, organization, management, and policy making in practice

Shortcomings and challenges of research concepts and methods

Critical case studies and field research on the theory-practice relationships in implementations of IC management

New theories and research methods for measuring and managing IC.

Whereas IP valuation is preoccupied with predicting the financial value of IP, IP evaluation is preoccupied with finding the relative strength within a IP portfolio owned by an organization, and also it is preoccupied with approaches to visualize, discuss and align IP activities and

strategies with different functional areas within the company. Teece (1998) underlines the importance of efforts to quantify the value of intangible assets in order to advance knowledge management theory further. Smith and Hansen (2002) emphasize the need for IP valuation theory to go beyond generic approaches such as citation analysis and to link the valuation approach with the strategy of the company.

It is important to be alerted early on if the strength of the IP portfolio is decreasing. Including remaining lifetime as an evaluation criterion makes this possible. The existing IP valuation theory disregards the importance of geographical range and in particular the importance of remaining lifetime of IP. The lifetime of protected brands can be extended forever, but concerning other types of IPR such as patents, utility models and designs, this constitutes a serious shortcoming of the existing theory. The existing theory is certainly relevant, but it is also insufficient if the purpose is to make sense at an organizational level.

An underlying assumption in this paper is that the best IP should be provided with most resources in order to secure the extent to which this IP can be leveraged by the organization in terms of own product offerings on the market and in terms of licensing out technology to other companies. With licensing out is meant that a company sells the license for its IP to another company and receives licensing fees as payment. Licensing in is the opposite scenario. Resources in this context concerns financial resources and managerial resources in order to secure maximum geographical range, and in order to secure the best possible formulation of the patent, securing the best possible broadness of scope of the patent in relation to the business purpose it serves. A related assumption is that IP management is rather complex and therefore it is of paramount importance to have an understanding of what is most important, and to allocate the management attention to these issues, since perfect performance in IP management is rather uncommon. Perfect performance in IP management would require the ability to anticipate the future beyond what is possible for human beings. Since this is not possible, it is assumed that it is better to focus on doing the right things instead of attempting to do everything right.

In the following IP value indicators which are present within the existing theory (Teece, 1986; Rivette and Kline, 2000; Harhoff et al., 2003; Davis, 2008), are complemented with value indicators pertaining to geographical range and remaining lifetime of IP (the remaining time before the maximum lifetime is reached) in order to in the same time to advance the existing theory and to increase the availability for the individual organization of this theory.

Theoretical framework

In the inquiry into how IP can be evaluated within organizations, intellectual capital (IC) - and knowledge management theory (Teece, 1986; Smith and Hansen, 2002; Harhoff et al., 2003; Davis, 2008) and theories on networking (Ahuja, 2000; Granovetter, 1973; Granovetter, 1985; Uzzi, 1996) are combined in order to build a theoretical framework which is applicable for IP valuation in general and for IP evaluation in particular. The resulting theoretical framework created in this paper, is relevant for both IP valuation and IP evaluation having the focus on the latter.

IP valuation theory

Bender (2007, 3) states in relation to valuation of intellectual property: "the trained licensing

professional will use any one of a number of techniques to justify their valuation of an asset: (1) comparables (i.e. comparison to similar assets that have been priced); (2) net present value and financial modelling techniques that require a number of assumptions regarding

potential revenue and cost; and (3) good old-fashioned "horse trading" (which is generally how things are really valued)".

It is difficult to estimate the value of IP based on comparisons with similar transactions if such transactions have not taken place. Even if such transactions have taken place the relevant information is often confidential and will therefore not be published or accessible. "Horse trading" may be difficult to analyze from a theoretical point of view. This may indicate that the "net present value and financial modeling" approach is the most feasible approach to apply. This approach requires a number of assumptions regarding potential revenue and cost. The importance of creating a good basis for making these assumptions is further underlined by the following quote: "The valuation models themselves are worthless

without the proper understanding of how value can be created through the use of intellectual assets and property... A fancy formula is often used as a substitute for real understanding. The old adage about mathematical models is truer than ever - Garbage in, garbage out".

(Heiden, Forthcoming, 3.8).

The value of IP is likely to be influenced by a number of factors. According to Martin and Drews (2005, 94) "identifying and understanding the value of intellectual property is

complex. The context of the valuation is critical in all cases and serves as the key value determinant". They further point out that:

IP valuation is becoming increasingly complex Value can change over time

IP valuation is a nonstatic process Context determines value

It can be relevant to consider the above-mentioned statements.

If value changes over time it may be more important to have a flexible framework for how to handle IP valuation than a static assessment which will be outdated very quickly.

If IP valuation is becoming increasingly complex and the most important value determinating factor is the context, it may indicate that various contextual factors are relevant to consider when conducting IP valuation. Ortiz (2009) also emphasizes the importance of the context when evaluating IP.

When evaluating the IP it is relevant to consider the extent to which the relevant IP has been cited in other IP (Harhoff et al., 2003). Also it is relevant to consider the technology and whether it is a "cumulative systems technology" (Davis, 2008) and the strength or weakness of the appropriation regime (Teece, 1986; Joly and de Looze, 1996).

Davis (2008) describe how a "cumulative systems technology" is likely to be worth less because it depends upon existing technology and IP. Teece (1986) claims that innovators, such as organizations which are filing patents as a part of their innovation strategy, are not always able to profit from innovation. Often new innovations primarily benefit other parties such as suppliers, customers and competitors more than it benefits the innovating company. He also claims that patents within many technological fields only have a limited value. As an exception to this general rule he mentions simple mechanic constructions. He also mentions the importance of having control of, or access to the necessary complementary assets, which are needed in order to reap the value from innovations.

Being upheld in opposition or annulment procedures or being part of a large international patent familiy indicates that a patent is valuable (Harhoff et al., 2003). It increases the value of a patent to survive the test of litigation, since the uncertainty connected to whether the claims of the patent can be upheld in court is removed.

Network theory

Ahuja (2000) introduces the notion of direct - and indirect ties in combination with the importance of structural holes which act as connectors between unconnected ties (Granovetter, 1973), which may be relevant to consider in this context. Another construct from network theory which may provide some explanatory power in the context is the concept of embeddedness (Granovetter, 1985; Uzzi, 1996), since the network of the IP department in a given company may determine the extent to which the organization is able to identify valuable IP within the organization. When considering the network configuration of IP departments and which other management functions to include in IP evaluations these theories seem relevant as a complement to the other theories mentioned above.

Methodology

The research method is based on abduction (Alvesson and Sköldberg, 1994; Dubois and Gadde, 2002) combining elements from both the inductive approach and the deductive approach. Continuous matching of theories with reality and vice versa has been the approach to secure empirical support for the theoretical framework. The basis for this process is a single case study (Yin, 2003) combined with the combination of theories outlined above. The case study was initiated in August 2007. The issue of construct validity and reliability is addressed since key informants review the case reports. The case company has headquarters in Denmark and it is a multinational company which provides a broad range of high-end products. The presented findings emerge from a single case, which to some extent may limit external validity. On the other hand, the fact that the created theory has proved applicable within a company, which is active in different industries, enhances the external validity resulting from "analytical generalizations" (Kvale, 1996). It is also enhanced by developing a relatively industry-independent theoretical framework using the abductive approach outlined in this section. The goal is theoretical development, rather than testing of theories or common ‘grounded theory’ approaches with the objective to continuously assessing the empirical support of a theory, or, inversely, a reality’s theoretical support, through the matching of theories with realities (Strauss and Corbin, 1990). This research project is a combination of in-depth empirical research and reflection in action (Schön, 1983) based on significant practical experience from the case company. The researcher was hired by the company in order to conduct the study. The empirical data was collected through interviews and work meetings. The research object (the case company) has been allowed to influence the result, by providing feedback and suggestions for improvements.

Interviews have also been conducted with a number of external experts on the topic in Sweden, Denmark and Germany. As a part of this experts from two other companies were interviewed concerning their experiences with conducting IP evaluations, and more specifically with their experiences with using the tool IP score.

Case presentation

Starting the case presentation slightly with a side note, it can be mentioned that the two other companies which were interviewed concerning their experience with conducting IP evaluations using the tool IP score, stated that the program, in spite of having some nice features, proved not sufficient for the needs of these companies.

The IP organization of the case company

The IP related activities within the company are divided between different departments of the company. IP activities related to trademarks, brands and designs are taken care of by the legal department which is led by the legal head. These issues are primarily taken care of by the legal head himself and an additional law educated employee, sometimes complemented with external attorneys. Patent activities are taken care of by the patent department, which again is a part of the business innovation department - led by the business innovation manager. The business innovation department is primarily working with new business areas and concepts for further growth of the company, as well as taking care of many important supply relationships. The business innovation manager has a background as former chief technology officer of the company, and he remains an influential person within the company. Located in the patent department the patent manager and the patent assistant can be found. The patent manager is educated as electrical engineer and he has taken extra courses in intellectual property management and international competition law. The patent assistant is educated as librarian. The case company is sourcing at lot of patent work to approximately 10 to 12 external patent agents, which are working for different patent bureaus. The external patent agents are ideally European patent attorneys having a master degree within the relevant technical field(s).

There are no formal requirements in the new product development process plan utilized by the company, that the project managers should consult the patent manager in case intangible assets are developed as a result of new product development projects. The patent manager and the patent assistant have regular meetings with certain parts of the company.

Some inventors have expressed their discontent with the fact that they are not receiving any kinds of benefits even though they invent new things. Some inventors mention that their project managers do not give them better feedback for their work if they invent something which is patented by the company. Inventors within the company are normally asked to provide a one page word document describing the invention, so it is easier for the patent manager to evaluate the invention. The work related to the writing of the one pager is not very popular from all inventors within the company, but most inventors do not mind.

IP budget

Although the patent related budget within the company is limited, this budget is to some extent flexible, since the patent manager is able to provide further financial resources from the company, if he perceives a need to do so. As an example of this, he provided additional 500,000 Danish kroner to the patent budget, by the help of the legal head, when he perceived the need to respond to patenting activities undertaken by primarily Apple.

The process

When the research resulting in this paper was initiated, the case company organization experienced problems concerning aligning IPR strategy related issues within the company. More specifically, for the patent manager it was difficult to know where to put the strategic focus. The patent manager was very eager to put his budget to use in the best possible way for the organization. Therefore he hired the author of the paper to evaluate the patent portfolio. The work conducted by the author was evaluated on an ongoing basis with the patent board of the company, which is constituted by the patent manager, the legal head and the business innovation manager. The need to evaluate the patent portfolio in relation to the product strategy of the company quickly and for this reason the senior product manager was also integrated into the process of developing an approach for evaluating the patent portfolio.

As a result of the feedback and discussions from this task force, combined with existing theory on the topic, the evaluation approach presented in this paper emerged. The approach was successful within the organization.

Analysis

The identification of new potential patents relies to a high extend on the informal contacts and the wide network of the patent manager within the company. This has certain benefits such as a relaxed atmosphere around the IP work. A drawback with this is that to some extent it seems to be the same people within the organization, with new ideas and inventions. Possibly, other people invent as well, but they never tell the patent manager about this. Having a more formal process concerning the identification of IP would possibly help to reveal such tacit inventions within the organization. Also if the importance of IP is more formally clarified for every project manager they would possibly be more prone to include whether employees have come out with new inventions, when they evaluate employees and how well they are doing their jobs. That might again relief the discontent felt by some inventors within the organization.

The fact that inventors are not receiving any rewards or increase in payment as a result of their inventions within the company is seemingly the norm within Danish companies. As a result of the IP evaluation process the overall IP awareness of the company across the management functions improved. This is likely to improve the problems concerning inventors being discontent in terms of what they get out of inventing things for the company. Manages who understand the importance of IP, is more likely to include IP issues in his evaluation of employees. Therefore it is likely that inventors to some extent will benefit from their inventions if his manager understands the importance of IP, since the inventor is more likely to get for instance an increase in pay as a result of being an active inventor, even though this is not in terms of an invention reward.

The legal head is located closer to the CEO of the company in terms of organizational structure and physical environment. For these reasons and possibly for personal reasons it is easier for him to provide additional funding for various activities within the company than for the patent manager.

Results

In this part the resulting IP evaluation approach will be further clarified and explained.

Therefore in the following example of an evaluation of an IP portfolio of patents is presented. Briefly the necessary steps to do so are outlined.

Firstly the management functions to include in the process are determined. These are in this case patent manager, business innovation manager, legal head and the senior product manager of the company, but differences may exist from company to company, which makes it relevant to include other management functions as well. These people now constitute a task force who are given the task of designing a few (3-4) organization specific product strategic focus areas (such as sound, picture, usability etc. according to what is important for the product offerings of the organization).

Each individual piece of IP, such as a patent, is then given a score in relation to each of the product strategic focus areas and for each of the three IP value indicators (1) geographical range, (2) broadness of scope and (3) remaining lifetime, where broadness of scope concerns the value of the IP according to a synthesis of existing IP valuation theory. Factors which should lead to a lower score in terms of broadness of scope include if the IP is depending

upon previous IP, not owned by the company, and if the IP is not cited in other IP. Other such factors include if the relevant appropriation regime is weak.

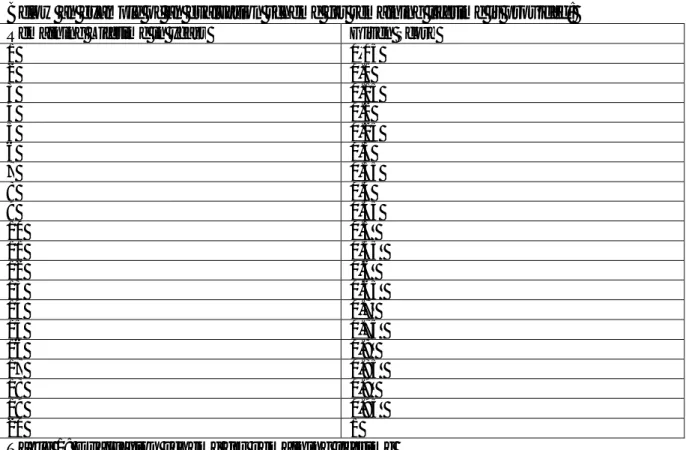

Scores and evaluation schemes

The scores are given on a scale from 0-10 for each of the product strategic focus areas. The score 10 signifies maximum importance of the IP within the product strategic focus area the score is describing, and the score 0 signifies minimum importance. Before any score is given, the evaluation scheme is clearly specified for each of the individual evaluation scores. The three scores given for geographical range, remaining lifetime and broadness of scope should each be between 0-1.

Evaluation scheme for remaining lifetime

Below an example of an evaluation scheme for remaining lifetime is provided: Remaining Lifetime in years Given Score

1 0.05 2 0.1 3 0.15 4 0.2 5 0.25 6 0.3 7 0.35 8 0.4 9 0.45 10 0.5 11 0.55 12 0.6 13 0.65 14 0.7 15 0.75 16 0.8 17 0.85 18 0.9 19 0.95 20 1

Table 1: Evaluation scheme for remaining lifetime

The evaluation scheme for geographical range should for instance stipulate how many countries in which the IP should be valid/active in order to be given a certain score. The evaluation scheme of the product strategic focus areas should take into account whether the IP is in use in existing - or if it is intended to be used in future products. If it is not intended to be used in any products it should result in a lower score, since the IP is likely to be strategically unimportant for the organization, unless it seems possible to license out the IP. Each type of IP, such as patents as opposed to designs, should be evaluated on its own, although patents and utility models sometimes can be compared. However, it is difficult to compare patents and designs.

Final calculation

The sum of the product strategic focus area scores for a patent should be multiplied with the score concerning geographical range.

The resulting number should again be multiplied with the score concerning broadness of scope and again with the score concerning remaining lifetime in order to get the overall score of a certain piece of IP. By the use of Microsoft Office Excel it is possible to visualize and evaluate the IP portfolio of the organization according to the preferences of the organization. Different weights can be distributed among the different constructs (product strategic focus areas, geographical range, broadness of scope, remaining lifetime) in order to secure a relevant evaluation of the IP portfolio, which fits the requirements of the individual organization. The IP can be split in different product - or technology areas in order to enable comparison of the relative IP strength between these and in order to facilitate strategic discussion based on this. This IP evaluation approach makes it easy to make decision oriented gap analysis between existing and the desired state of the IP portfolio. If a certain patent is found to be important in relation to the product strategic focus areas, but the patent does only have a minor geographical range, this signifies a relevant gap to close. If for instance the specific patent is filed within the PCT (Patent Cooperation Treaty) system, the geographical range of the patent can for a long time after initial filing be extended. If it is still possible and relevant for business purposes to extend the geographical range of an important patent, this should be done.

Discussion

The goal for IP valuation and IP evaluation theory should be to create models - and approaches, which fluctuate in accordance with the value of the IP. Evaluating an IP portfolio in a vacuum, meaning hiring someone to do this on his own disregarding organizational and strategic issues, does not make much sense.

This paper argues in favor of considering the remaining lifetime of IP when evaluating IP. The 25% rule is one IP valuation approach, which to some extent takes into account the remaining lifetime of IP. According to this rule (of thumb), IPR is worth 25% of the net present value of business opportunities which relate to the scope of the IP within its remaining lifetime (concerning patents, utility models and designs). It may be a relevant rule of thumb to keep in mind when negotiating a license contract, but it is inadequate and fully insufficient as an approach to use for IP evaluations within organizations having numerous IP. Given the uncertainty of the results - and the workload required in order to estimate the profit potential relating to the scope of IP, the 25% rule is infeasible to use for most organizations when making IP evaluation.

The claim put forth by Teece (1986) that patents within many technological fields are less valuable, should probably be evaluated slightly different from when he first presented it. Changes such as the Bayh Dole act have in many cases made patents more valuable than they would otherwise be. This makes it relevant to regard the findings made by Teece (1986) in a new light, although that could arguments in his seminal work of course still are valid.

Although it certainly increases the value of a patent to be upheld in opposition or annulment procedures the relevance of this value indicator is limited somewhat by the fact that most organizations have none or very few patents, which have been upheld in litigation. This underlines the importance of alternative value indicators.

When discussing different approaches to IP valuation and IP evaluation is relevant to consider whether the used approach should take into account that a diversity of purposes of IPR may exist. Different purposes could be (1) to block competitors, (2) to create licensing

revenues and other purposes. To block competitors in the realm of IPR can be defined as making it legally impossible - or not worthwhile for these competitors to initiate activities within certain technical areas.

Regardless of the purpose of a patent - or a utility model, it is formulated in a similar way, always attempting to maximize the broadness of the scope of the patent within its relevant area. It is easier to evaluate whether a patent is fulfilling its purpose in terms of creating licensing revenues. However, it is unlikely that a patent is able to create licensing revenues if it is not in the same time blocking competitors, thereby making it a better alternative to pay licensing fees instead of attempting to work around the patent/utility model. Therefore it is irrelevant to distinguish between different purposes of IP, be it blocking competitors or creating licensing revenues following one strategy or the other (Davis, 2008), when evaluating IP portfolios. One reason why it does not make sense to make the distinction mentioned above is that it is only partially possible to measure the extent to which IPR is blocking competitors. It is possible to measure some of the effects certain IPR has on a business. For instance, it is possible to evaluate whether a patent generates licensing profits. In case of litigation, or identification of workaround solutions made by competitors, it is also possible to evaluate whether a patent, or a group of patents, is able - or unable to block product developments from competitors. On the other hand, it is impossible to measure which actions a patent is causing competitors not to take. This is a difficult challenge for IPR management research.

The IP valuation should consider not only the existing patent portfolio of the company, but also considerations concerning how the organization works with and creates new IP. To this end it is irrelevant to consider how the organization identifies new IP. The intra-company network of the patent department is likely to play a pivotal role in this context. Rather than relying on this network it may be relevant to consider other means of increasing the IP awareness in the organization. Informally this can be done through processes like the one presented above and through social networking and interaction. More formally it can be done through stipulating directly the importance of IP by, for instance, including an IP check point in new product development processes.

Conclusion

The developed IP evaluation approach primarily applicable for patents and utility models, is useful in order to discuss, visualize and align IPR issues with different management functions within the organization. It further enables the individual organization to consider across management functions the IP strategy of the company. By including the remaining lifetime and the geographical range of IP as measurements, it is easier for the company to identify gaps in the IP strategy - and in the way in which the IP resources of the company are utilized. It decreases the complexity of IP management, since it provides the patent manager with relevant feedback and input from other management functions, which enables him to perform better and more informed decisions in the everyday work on both strategic and tactical level. Moreover, it improves the overall IP awareness across the management functions, which in turn is likely to improve the ability of the organization to create new IP.

Limitations and further research

It is readily admitted that the remaining lifetime is not always an important factor when determining the value of IP. Within an industry such as manufacturing of mobile telephones, which is characterized by rapid technological development and short new product

development lead times, this value indicator may be less relevant, since the patent is most often irrelevant before it reaches the maximum lifetime of 20 years. However, within the pharmaceutical industry, which is characterized by long new product development lead times - sometimes 12 to 14 years, the remaining lifetime of IP is of outmost importance.

The value of a patent predicted by IP valuation theory should ideally be equal to the value it is possible to extract from it (Edvinsson and Sullivan, 1996) within the remaining lifetime of the patent or within the remaining time product offerings are created which are within the scope of the patent. Assuming, a perfect correlation between the value of a patent and its remaining lifetime may disregard the fact that the uncertainty of the value of a patent or idea, most often is biggest at the beginning of its lifetime. At the beginning of a patents lifetime it may still remain unclear whether or not, or to which extend, the market will respond favorably to product offerings within the scope of the patent. Possibly, the general relation between the value of a patent and its remaining lifetime could be best described by an inverted U-shaped curve. More research is needed to make more precise predictions within this field of research.

As presented in the methodology part, the case company in this paper is active within a number of industries, which may improve the extent to which the findings in this paper are possible to generalize beyond the present case as a result of "analytical generalizations" (Kvale, 1996). This being said, it would be beneficial to extend the present single case study with additional cases in future research efforts related to the findings presented in this paper, in order to secure improved external validity.

If it should be attempted to inquire into wider implications of licensing businesses on the overall business performance of a company, it might be relevant to draw a link to the strategic management literature. Before considering the thoughts of a couple of the classics within the strategic management literature of research it can be interesting to turn to Boisot (1995) who claims that the extent to which a brand can be exploited within different areas, is limited. This may go against the thoughts of people who believe that even IP, which is more or less unrelated to the business area of the company, should to the widest possible extend be exploited by the owner company in terms of products which are developed and marketed by the company itself. The argument of Rumelt (1982) who claims that synergy is of paramount importance for sustaining profitability might be relevant to consider in this context. Licensing out IP which it is not possible to exploit in a synergistic way may enable a company to remain synergistic. Chandler (1962) emphasizes that return on investment is not only determined by the ratio between sales and profit, but also by the ratio between sales and capital investments. The latter ratio indicates to some extent the risk related to the business. Since licensing out IP normally is less capital intensive than developing and marketing products, it may often be a beneficial choice for a company to license out IP in order to sustain higher returns on investments in the long run, since it may be a less risky business approach. It would be interesting to investigate a research question such as: among comparable companies, do companies who license out have higher return on investment over time?

Further research is also needed concerning the extent to which the network of an IP department and more particularly the embeddedness of such a network determines the ability of the organization to identify inventions.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to the case company, especially to the patent manager and the patent assistant of the company. The author is also grateful to Handelsbanken’s stiftelse for supporting the PhD position of the author.

References

Ahuja, G. (2000) Collaboration Networks, Structural Holes, and Innovation: A Longitudinal Study

Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol.45 No. 3, 425-455.

Alvesson, M. & Sköldberg, K. (1994) Tolkning och Reflektion, Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Bender, L. H. (2007) The Art and Science of Licensing in the Pharmaceutical and Biotech Industries Licensing

Journal, Vol.27 No. 1, 1-6.

Boisot, M. H. (1995) Information space: A Framework for Learning in Organizations, Institutions and Culture, London: Routledge.

Chandler, A. D. (1962) Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of the American Industrial Enterprise, Cambridge: MIT Press.

Davis, L. (2008) Licensing Strategies of the New "Intellectual Property Vendors" California Management

Review, Vol.50 No. 2, 6-30.

Dubois, A. & Gadde, L.-E. (2002) Systematic combining: an abductive approach to case research Journal of

Business Research, Vol.55 No. 7, 553-560.

Edvinsson, L. & Sullivan, P. (1996) Developing a model for managing intellectual capital European

Management Journal, Vol.14 No. 4, 356-364.

Granovetter, M. (1985) Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness The American

Journal of Sociology, Vol.91 No. 3, 481-510.

Granovetter, M. S. (1973) The Strength of Weak Ties The American Journal of Sociology, Vol.78 No. 6, 1360-1380.

Harhoff, D., Scherer, F. M. & Vopel, K. (2003) Citations, family size, opposition and the value of patent rights

Research Policy, Vol.32 No. 8, 1343-1363.

Heiden, B. (Forthcoming) Patent Valuation: In theory and practice, To be defined: To be defined.

Joly, P.-B. & de Looze, M.-A. (1996) An analysis of innovation strategies and industrial differentiation through patent applications: the case of plant biotechnology Research Policy, Vol.25 No. 7, 1027-1046.

Kvale, S. (1996) InterViews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Martin, D. & Drews, D. C. (2005) Intellectual Property Valuation Secured Lender, Vol.61 No. 5, 22-96.

Ortiz, M. A. A. (2009) Analysis and evaluation of intellectual capital according to its context Journal of

intellectual capital, Vol.10 No. 3, 451-482.

Rivette, K. & Kline, D. (2000) Rembrandts in the Attic: Unlocking the Hidden Value of Patents, Boston, MA: Business School Press.

Rumelt, R. P. (1982) Diversification Strategy and Profitability Strategic Management Journal, Vol.3 No. 4, 359-369.

Schön, D. (1983) The Reflective Practitioner, New York: Basic Books.

Smith, M. & Hansen, F. (2002) Managing intellectual property: a strategic point of view Journal of intellectual

Capital, Vol.3 No., 366-374.

Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (1990) Basics of Qualitative Research, California, US: Sage Publications.

Teece, D. (1998) Research directions for knowledge management California Management Review, Vol.40 No. 3, 289.

Teece, D. J. (1986) Profiting from technological innovation: Implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy Research Policy, Vol.15 No. 6, 285-305.

Uzzi, B. (1996) The Sources and Consequences of Embeddedness for the Economic Performance of Organizations: The Network Effect American Sociological Review, Vol.61 No. 4, 674-698.